The Lilin is a web-blog that gives an intersectional-feminist spin to anime/manga, pop culture, and internet media, all the while trying to navigate through the world of Generation-Y young-adulthood.

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Video

youtube

i did a video essay on the love witch and cindy sherman for my foundations of feminist theory graduate course midterm because i’m a masochistic clown who thought it would be fun and not nearly kill me

59 notes

·

View notes

Link

MY ARTICLE IS UP! I worked so hard on this, and I can’t wait to see the response from Eva fans and fellow feminist media scholars.

254 notes

·

View notes

Photo

2) Stranger Things (season 1)

youtube

This summer’s blockbuster season was generally underwhelming. Partly, I blame Captain America: Civil War for coming out so early in the season and setting the bar so high in comparison to every other major Hollywood release. And I think it’s fair to say that hearing about Jared Leto’s edgy method acting antics in the painfully-okay Suicide Squad for months generally turned folks off from the time-honored tradition of going to the movies and seeing a big-budget genre flick.

Also, everyone was too busy binge-watching Stranger Things.

I walked in on my mom and my sister in the middle of the third episode the day after the series came out, to which my mom called me over and said, “You gotta come watch this with us, Winona Ryder’s in it.” I revere Winona Ryder like a modern day Mary and will literally watch anything she graces her presence in (CCTV footage included, sorry). And like me, the promise of Winona Ryder is probably what brought a lot of folks to Stranger Things — but while I definitely came for the Wino, I stayed for the 80s sci-fi homages, more totally adoptable characters (DUSTIN!!!!!!!!!!!), vintage synth soundtrack, and 2017 Golden Globe nominee Winona Ryder(!!!).

There’s honestly too damn much I love about Stranger Things, so I won’t waste your time with a five-page love letter to the Duffer Brothers for making 2016 marginally better. What I can say is that I’ve rewatched the first season three times already and still keep finding new things to pick over and appreciate. Stranger Things is a goldmine of meta-references and shout-outs that fellow cinephiles, Stephen King fans, and genre-nerds can derive meaning from; the plots and subplots themselves are homages to E.T., The Goonies, A Nightmare on Elm Street — hell, there’s even some Akira thrown in there. Considering that I grew up on a steady diet of my mom’s mini-King library and my dad’s collection of cult movies, I’m inevitably a bit biased here. If you found The Force Awakens to be too reliant on the plot-structure of A New Hope then yeah, you might take issue with Stranger Things. In my opinion, however, this only strengthens its storytelling, which is often difficult to do in a series juggling multiple concurrent plots. Unless your series is named JoJo’s Bizarre Adventure and your name’s Hirohiko Araki, if your story fails to resolve (let alone follow up on) key plot points, you’re gonna deliver a big-old pile of Jurassic World-level disappointment. A clean narrative structure is a clean narrative structure regardless.

But what I appreciate the most about the series is how it confronts and subverts the gendered tropes embedded in the horror and sci-fi genres. The ladies of Stranger Things represent some of the most well-known female archetypes found in genre works: final girls, intuitive (but mentally unsound) chain-smoking single mothers, and creepy psychic kids. But where we start with these characters is not where we end up: Nancy Wheeler (Natalia Dyer) goes from the stereotypical self-absorbed teenage girl/older sibling role to a baseball bat-wielding final girl whose survival isn’t contingent upon sexual celibacy; Eleven explores the often marginalized (if not grossly fetishized, see Elfen Lied) trauma of the little girl weapon-of-mass-destruction with touching warmth, courtesy of the brilliant Millie Bobby Brown; and Winona’s Joyce Byers is just a goddamn great mom and I am here for more working-class single mothers going beyond the limits of our dimensional universe to save their goddamn bowl-cut kid.

As a cultural measuring stick for the horror and sci-fi genres, Stranger Things offers a comforting nostalgia for pop culture’s past in addition to its effective storytelling, incredible young talent, and the divinity of Winona Ryder. My only criticism is its pretty glaring lack of racial diversity, something I hope season 2 greatly improves upon. The token character of color role (in this case Caleb McLaughlin’s Lucas, whose characterization as the skeptic of the boys’ group marginalizes him as overly aggressive and even unlikable to the audience) (also a real waste of Caleb’s obvious comedy-chops) is a less welcome export of eighties narratives, especially considering how steeped in stereotypes characters like Data (The Goonies) were. Still, Stranger Things’ premiere season is a solid start to what I hope will be a long-running series, and with season 2 confirmed and currently in production, 2017 will have at least one thing worth living for.

[This post is dedicated, in loving memory, to the dearly departed Barb. May your granny glasses and sacrifice as the third-wheel be avenged in season 2.]

19 notes

·

View notes

Photo

2016 was bad.

It was so bad that I’m actually low-key jealous of people in comas. I know how horrifyingly bad that sounds but considering the sheer mental duress this godforsaken year has put me under, I really would’ve preferred to have been unconscious for like, 75% of it.

For the most part, 2016 was overshadowed by the political nightmare that was the US presidential election, and with the results being what they were, I plan on spending the next four years of my life silently shrieking. As if that weren’t god awful enough, we also had to deal with a clown epidemic; Prince, Bowie, and Cohen dying on us; and Twitter pulling the plug on Vine. So yeah, I’m cynical, to say the least.

As it currently stands — because god knows anything can happen between now and inauguration day — we’ve been condemned to living under the presidency of a real-life Back to the Future Part 2 Biff Tannen who’s been terrorizing women, people of color, and immigrants since mid-2015, but who knows? If 2016 is the steaming pile of existential woe that keeps on giving, I don’t think it’s too much to hope that a Christmas miracle will come in the form of a rogue planet slamming into us a’la Melancholia.

That all aside, 2016 wasn’t completely worthless. Occasionally, my will to live would be reignited by something pretty cool, giving me enough hope to deal with the stress of living in this garbage world for at least another week. For me, 2016 may go down as both the year I graduated college (also not something I’m very happy about) and the beginning of the political Dark Ages, but I’d still like to take the time to give a shout out to the shit that helped me cope with twelve straight months of shitting my pants.

1) JoJo’s Bizarre Adventure: Diamond is Unbreakable

youtube

Since it’s premiere in April 2016, the anime adaption of Diamond is Unbreakable has been my sole reason for living to see Fridays, giving me a much needed dose of joy week after week in this increasingly hellish year.

Following the lovable Japanese delinquent Josuke (JoJo) Higashikata and his fix-it stand, Crazy Diamond (who’s got, like, a really nice ass), Diamond brings the Joestar family’s bizarre legacy to the small town of Morioh-cho, combining Hirohiko Araki’s pop culture-infused shounen with a suburban murder mystery worthy of David Lynch. David Productions’ animated adaption is as faithful to the aesthetics of its source material as it is to its plot, at times even improving upon the manga’s we’ll-figure-it-out-as-we-go-along sense of pacing by planting early cameos and easter egg references to future plot points in the series. That considered, I don’t recommend this anime as a starting point for those looking to get into JoJo (I’m a stickler who doesn’t recommend people skip shit in general), so parts 1-3 of the manga or anime are required reading/viewing considering how outlandish most plot points are without narrative context. I mean, do what you want, but Diamond is the second time in the series wherein someone fights with a bowl of spaghetti.

Visually, Diamond is probably the most Gucci thing you’ll see in anime. With the exception of the expected (but nonetheless hilarious) off-model frames, it’s generally pretty well animated, but David Production’s main strength with JoJo has always been in their ability to adapt Araki’s distinctive art-style into an animated kaleidoscope of colors. Diamond is drenched in jewel-tones, reflecting the rich, glossy look of late-90s pop videos and Baz Luhrmann films.

The real joy, however, is the sheer fun of this particular arc. I made a point of live-blogging every episode I could as soon as it went up on Crunchyroll just for some goofs and gaffs, most about shots resembling this cursed image. But as this year got progressively shittier, JoJo became a refuge from the horrors of reality with its characteristically fantastical storylines (i.e. Rohan’s house) and endearing, totally adoptable characters. Part 4 is arguably the least angst-ridden JoJo arc, which is probably what makes its escapism all the more enjoyable in these dark-sided times. The stability of human society may be regressing at an alarmingly progressive rate, but at least I had stuff like this to look forward to each week.

youtube

#Anime & Manga#anime review#JoJo's Bizarre Adventure#Jojo no Kimyou na Bouken#diamond is unbreakable#david production#misc#review

26 notes

·

View notes

Photo

As some of you guys have probably noticed by now, I haven’t been very active with this web blog these last few months. Since graduating college in May, I’ve more or less been in a constant state of “what the hell am I going to do now?” I’ll be honest; things have been tough. I got hit with some HARD post-grad depression thanks to the stress of searching for employment and still turning up empty. So yeah, things have kinda really sucked these past few months, but thankfully this update isn’t a formal announcement that I’ve finally given up and will be cryogenically freezing myself for the foreseeable future.

Anyways, 1) I’m not dead or as sad anymore, 2) I do plan on following up with Part 2 of Women in JoJo (it’s currently half-way finished in my drafts), and 3) I’m gonna be doing some really cool stuff for some really great sites!

I’m happy to announce that I will be featured on Ungilded, an up-and-coming feminist web-project, and Anime Feminist, a new site focused on covering anime and manga through a feminist lens! You can expect my debut articles to be published by the end of the month and some time in January respectively.

Ungilded’s got an Instagram you can connect with and they’re also open for reader submissions geared towards politics, internationalism, health, news, etc.

You can support Anime Feminist on Patreon so more academics like myself can have a space to keep doing what they love (i.e. have feminist discussions about Godzilla). You can also follow them on Twitter and Facebook.

Lastly, I’m also in the process of editing my manuscript for Actions Girls Are Doing It for Themselves for submission to scholarly journals. I’m hoping to have the academic crowning achievement of my undergraduate career ready for publishing very soon. I know people have been dying to read it.

So yeah, that’s essentially what I’ve got going right now, so be on the lookout for new content after the holidays.

Peace -

Nicole

11 notes

·

View notes

Photo

I feel sick.

In the two weeks since the presidential election, I’ve existed as an emotional composite of anger, fear, heartache, disgust, and — if I’m being completely honest — the slightest impulse to burn shit down. As a whole, it’s formed an inescapable feeling of nausea in the pit of my stomach, which no amount of dry heaving or Dramamine seems to help. I’ve only picked at half-eaten take-out and granola bars because I seriously doubt my ability to keep the contents of my stomach from spewing back up.

Nothing feels stable anymore, and I’ve been left swaying back and forth from the whiplash of our political system. I guess I should plan the next four years around being perpetually motion sick.

After four glasses of white zinfandel and five fingernails chewed off, I went to bed at 11:30 pm on November 8th and reassured myself that everything was going to be okay. I’d wake up the next morning to a madam president and seventeen months-worth of anxiety lifted off my shoulders. I had to have faith in the safety-net of human rationality, because there was just no way that a (con)man/sentient pile of spray-tanned dog shit could be elected to the highest office in the United States on a platform of sheer narcissism and unapologetically violent racism, misogyny, xenophobia, Islamophobia, homophobia, transphobia, human indecency, etc.

I woke up dizzy and drenched in a cold sweat at around 3:55 in the morning. Instead of reaching for the couple of Ibuprofen capsules on my night table, I gave into my anxiety and checked my Facebook feed.

And as I scrolled past status after status without any mention of shattered glass ceilings, it dawned on me that the safety-net had given-way a long time ago.

We were, essentially, a splattered mess of blood, guts, and broken bones all over the pavement.

I felt the impact as a surge of stomach bile so strong that I hit my head retching into the toilet.

If this overwhelming sickness seems like an overreaction to you, there is something you should probably know about me.

I, like so many other women, am a survivor of sexual assault, something which I’ve become increasingly more vocal about as a young feminist facing Mr. Trump’s gold-plated misogyny. Sexism permeated throughout this election like a fart in a crowded elevator, which is repulsive enough. Misogyny has always played an ugly, implicit part in American politics, and nowhere (aside from the still-intact glass ceiling) has it been more prominent than in the political sex-scandal.

Allegations of sexual misconduct have had a whole range of effects on political careers, from the termination of presidential campaigns (Herman Cain, who famously ended his campaign for the 2012 Republican primary with a quote from The Pokémon Movie) to the impeachment of a sitting president (Bill Clinton, whose actions, need I remind you, are not the responsibility of his wife). Obviously, there’ve been plenty of politicians whose careers have survived sex scandals, but generally speaking, a public history of sexual misconduct is at the very least outwardly frowned upon in our candidates. These days, if you’re going to be a misogynist in American politics, you’ve got to be subtle about it, like publicly saying you care about women’s rights while also working to pass draconian anti-choice legislation, say, like Mike Pence.

Donald Trump was already a well known pig years before I was even born, and his chauvinism has played a constant, explicit role in his public image. He’s the perfect personification of patriarchy, with a toxic masculinity fueled by capitalist greed and narcissistic entitlement, and his unapologetic misogyny only grew stronger as a politician, likely because it clicked with conservative reactionaries in the face of this new feminist movement.

Donald Trump repulses every fiber of my identity as a woman. If given the chance and the right time of the month, I’d like to be the feminist folk-hero who threw her used, menstrual blood soaked tampon right in his wrinkly orange face. I didn’t think I could detest him anymore than that.

And then the Access Hollywood audio was released.

You remember that “locker room talk”, right? Where, upon seeing soap actress and segment guest Arianne Zucker outside the bus, he told Billy Bush about how being famous and wealthy meant “you can do anything” to women? Like “grab ‘em by the pussy”?

You know, talking about forcing himself on Arianne Zucker, which is sexual assault?

You know, admitting to sexual assault, which happens to be what grabbing a woman’s genitals is?

This is where my repulsion for Mr. Trump became a deep seated, physical nausea, because what he talked about doing on that audio tape is exactly what happened to me.

When I was thirteen, I was grabbed by the pussy by a group of boys at summer camp. I was grabbed by the pussy and grabbed by the breasts and prodded and molested in the community swimming pool where I’d spent every summer of my childhood.

When I was fifteen, a boy I went to high school with told people he planned to rape me in the girl’s bathroom. I was pulled out of first period and told to go to the vice principal’s office, where a police officer and my mother were waiting for me because washing my hands between class was suddenly the most dangerous thing I could do that day.

I’m twenty-three now and although eight to ten years have passed, my voice still cracks when I talk about what happened to me.

Trump’s presidential campaign was a marathon of offensive, morally reprehensible antics from day one, and up until election day, I think most of us assumed that Trump would fail because publicly mocking the disabled, rubbing shoulders with the KKK, calling for a registry of all American Muslims, and so on and so forth, could only end in political self-destruction.

And yet rather than imploding under the weight of so many scandals, the shitshow kept on going.

That ten-year-old audio tape of our president elect boasting about sexual assault should have been the end of it all, and the twelve women who came forward afterwards with allegations of sexual misconduct should have been enough to bury Trump in his own filth come election day.

Instead, I now live in a world wherein I have to relive the most violating things that have ever happened to me whenever a flag is raised or the national anthem is sung. We’ve rewarded an unapologetic chauvinist and serial abuser with the most powerful position in the United States (if not the entire modern world). How, pray tell, am I supposed to have any faith in our democratic system when it can enable a culture of violent misogyny to roam free for the next four years?

And if you think I’m getting ahead of myself, consider the surge of hate crimes in the days following the election. Between November 9th and November 16th, Southern Poverty Law Center gathered approximately 701 reports of hate-fueled intimidation and harassment, a good chunk of which (surprise!) reference the president elect. These reports include racist vandalism, direct intimidation and threats, and hate-group recruitment, all directed towards immigrants, Muslims, people of color, LGBTQ individuals, and, of course, women.

(By the way, if your response to this is to cite instances of harassment connected to the anti-Trump movement, SPLC counted those too: 27. That’s roughly 3.7% of all collected incidents, compared to the 96% previously mentioned. Kinda stupid to compare the two, if you ask me.)

This man hasn’t even taken office yet and he’s already caused so much pain among our vulnerable communities — the communities of my friends, fellow activists, and former college peers, whom I stand in solidarity with and reaffirm my commitment to as an ally. The administration forming in front of us does nothing to ease these fears, as Trump’s cabinet already includes noted white nationalist/alt-right darling Steve Bannon and Jeff “deemed too racist to be a federal judge under Ronald Reagan” Sessions.

And as a survivor, I feel that my experiences justify my rage, and that through politicizing my trauma, I not only reclaim agency over my assault, but attack the institutions of oppression that allow rape culture to permeate throughout our society.

I do not intend to speak on behalf of all survivors. Every story is different because everyone is different, subjected to differing matrices of identity that impact the ways in which we experience the world. For a number of valid reasons, many people are private about their assault, choosing to heal quietly and without reference to any political underpinnings.

I, however, do not view my assault, my gender, my mental illness, or my class-background as separate from the misogyny, racism, and capitalist greed Donald Trump successfully ran his presidential campaign upon. To me, this man’s election gives millions of Americans a free-pass to hate, and I can assure you that the consequences will be deeply misogynistic.

My word of advice to anyone who will try to grab as much non-consensual pussy as they’d like; be careful, because mine comes with teeth.

#election 2016#presidential election#donald trump#alt-right#republican#politics#united states#rape#sexual assault#sexism#misogyny#rape culture

18 notes

·

View notes

Photo

For a manga series that’s been running since 1986, there’s a lot to dissect from JoJo’s Bizarre Adventure. I started getting into the series this past January after my friend sat me down to watch the first episode of the anime, and it’s been an absolute trip ever since. JoJo is certainly one of the strangest franchises to ever emerge from Japan (yes, stranger that Evangelion, I’ll admit it), considering that some of its plot points include a guy who can turn into a velociraptor (Part 7: Steel Ball Run), a baby being fed its own shit (Part 3: Stardust Crusaders), and an amnesiac with four testicles who’s actually a fusion of two different characters (Part 8: Jojolion).

The “bizarre” aspects of JoJo are arguably part of the reason why Hirohiko Araki’s work has been so successful, encompassing everything from the general absurdity of a narrative that requires its readers to suspend their disbelief to a rich and colorful cast of characters whose aesthetics frequently blur the lines of masculinity and femininity. The gender dynamics in JoJo’s Bizarre Adventure are some of the most recognizable — yet frequently overlooked — characteristics of the series as a whole. On one hand, you’ve got a bunch of Arnold Schwarzenegger-sized men running around using their supernatural abilities to beat up vampires, zombies, sharks, and the occasional plate of spaghetti. On the other hand, they tend to do it while sporting crop tops and neon shades of lipstick.

But this parody of action hero-style masculinity isn’t the topic I’ll be delving into today. Instead, I wanna talk about the women of JoJo — the roles that they play and how they’ve been portrayed throughout the series. To put it bluntly, if there’s one fundamental flaw with JoJo (aside from Araki’s mass grave of forgotten plot points, let’s be honest) it can be found in its history of undermining, underwriting, and marginalizing female characters. I’ve spent a lot of time thinking about this, and it’s grown into a lengthy conversation I’ve been having with myself. In the spirit of JoJo’s Bizarre Adventure (and to save all of you from eye-fatigue), I’m going to break my analysis into two to three parts.

First, I just want to give you a basic idea of what the gender representation of JoJo has looked like throughout its run, comparing the number of narratively significant female characters to narratively significant male characters in each part, plus some notes on the roles of these female characters. And by “narratively significant,” I mean that the character meets three or more of the following criteria:

Have a name

Have a speaking part

Are recurring (featured more than in one chapter arc)

Serve a key purpose to the plot

Basically, if you can’t replace a female character with a sexy lamp and have the plot be totally unaffected (beyond someone asking, “What’s that lamp doing here?”), you’ve got a narratively significant female character.

(Click here for full-sized image.)

For the most part, JoJo has been a pretty tightly packed sausage-fest. Even the female-led Stone Ocean is only about 54% female (and that was being generous by including minor, recurring characters such as Gwess).

It’s understandable why some of the earlier parts (namely Phantom Blood) were so heavily male. JoJo started out running in Weekly Shōnen Jump — whose target audience consists of young male readers — until 2004, after which it was moved to the seinen (older-male) focused Ultra Jump in 2005 (x).

Additionally, Araki’s admitted to struggling with depicting female characters. While one of his earlier works, Gorgeous Irene (1984-1985), focused on a female protagonist, Araki’s stated he’s embarrassed of the way he wrote Irene, believing it reflected “his ignorance of women” as a younger mangaka (x). It’s understandable why a creator would be hesitant to centralize their stories around a character whose gender identity differs from their own. It’s an intimidating feat, and doing justice to representation often seems much harder than just sticking to what you know. Of course, that isn’t an excuse for skipping out on diversity, but Araki’s lack of confidence in writing female characters does provide some explanation as to why women are so underrepresented in the earlier parts of the series.

It’s also important to note that Araki has made attempts (and relative progress) towards giving female characters more important roles throughout JoJo. The most blatant example of this is, of course, Jolyne Kujo, the sixth JoJo. I admittedly couldn’t find the precise source material for this, but tumblr user @everydayduelist posted that Araki created Jolyne in hopes of rectifying his past failures at female protagonists in the series (x). Even if this isn’t necessarily correct, centralizing on a female lead in one of the most popular shōnen/seinen manga series of all time was nonetheless a bold move, and one Araki wasn’t able to get away with doing until part 6.

Araki’s also claimed that the manga industry itself held him back from expanding upon female characters in JoJo. The series’ first main female character to possess any sort on in-universe combat powers was Battle Tendency’s Lisa Lisa, the Hamon master who trains Joseph Joestar and Caesar Anthonio Zeppeli for their fight with the Pillar Men. (Yours truly also cosplays her.) Lisa Lisa was meant to convey Araki’s fondness “for female characters who are capable of fighting for themselves” (x), and she stood in stark contrast to the idealized female characters in similar male-focused series at the time by simply being an intimidating, warrior-type of character (x). As progressive (and arguably unheard of in Japan) of a female manga character as Lisa Lisa was in the late eighties, Araki still felt he was “held back” from delving further into her character with an “uncommon realism” for female characters in a shōnen title (x).

And this takes me to what I see as a pattern of faults surrounding female characters in JoJo, which I began to notice with Lisa Lisa herself. One of the earliest things I picked up on in the series was the realization that practically every major female character was either a wife or a mother to a JoJo: Erina Pendleton becomes the wife of Jonathan Joestar and the grandmother of Joseph Joestar, Lisa Lisa is actually Elizabeth Joestar and the mother of Joseph, Suzie Q ends up marrying Joseph, Holly Kujo is Joseph’s daughter and Jotaro’s mother, so on and so forth.

This isn’t necessarily a bad thing, and JoJo is (in its simplest form) a story about a family line. But when you compare this to the roles of other significant male characters in the early parts of the series, it’s hard not to believe that wife/mother relationships were a sort of crutch-trope for including women in JoJo. Furthermore, being a wife or a mother tended be a central aspect for many of these characters. With the exception of Lisa Lisa, they don’t do much of anything in terms of engaging with the story’s action. They’re more or less off to the side, domesticated women.

On the topic of Lisa Lisa, there’s also the matter of her fight with Kars — or rather, her lack of a fight. Up to this point in Battle Tendency, we hadn’t seen Lisa Lisa use the extent of her powers. She didn’t engage in any fights, and the only way we know she’s as powerful as other characters claim is simply because she ruthlessly trains Joseph and Caesar.

Her one-on-one fight with Kars was supposed to be the first time we saw her in combat. It was supposed to depict Lisa Lisa as being the strong female character Araki intended to depict. Instead, Kars tricks her (which is super low, not to mention comes out of NOWHERE) and stabs her in the back before their fight can even properly start.

Was this really necessary, character-wise or plot-wise? No. If it does anything at all, it just undermines Lisa Lisa’s character by depriving her of the chance to engage in combat rather than coolly observe.

This may seem like a standalone example of Araki pulling the rug out under a female character, and since Battle Tendency, we’ve been able to see subsequent female characters get their fair shot at a fight.

But then we get the end of Stone Ocean.

As mentioned, Stone Ocean and its respective JoJo, Jolyne Kujo, were supposed to compensate for Araki’s previous fumblings with female characters. This is great and all, and I genuinely love Stone Ocean for what it does with its leading ladies (especially in starting out with a frank dialogue about female masturbation, but take that as you want). And yet not only does Jolyne end up dying in the end, but she fails to stop the arc’s villain, Father Pucci. The character who gets that honor is Emporio, the little boy side-kick who really wants to play baseball for some reason.

While Jolyne may not be the first or only JoJo to die at the hands of an antagonist (I love you Jonathan and you deserved better!), there’s really no discernible reason why she had to be defeated. If Jotaro can inexplicably jack The World’s time-stopping powers to defeat Dio, Jolyne easily could’ve pulled some ridiculous new Stand-ability out of her ass to overcome Made in Heaven.

Regardless of Araki’s intentions for Jolyne’s (and Lisa Lisa’s) defeat, the result is ultimately frustrating. Despite how much I hate using the term “glass ceiling,” it certainly feels as if there’s some invisible barrier preventing the women of JoJo from achieving their full potential as characters.

As a female fan, I want to see myself fairly represented in a series that I love. When I make gender-based criticisms of the anime and manga I enjoy, it’s because I see their potential to be even better.

Again, I want to make it clear that as far as I’ve observed, JoJo has made steady progress towards including more female characters whose roles are better expanded upon than in the series’ past parts. The eighth and current story arc, Jojolion, has done a fair job of this with its roughly 50:50 male-to-female-characters ratio. I have to give Araki credit for improving this aspect of his series.

Anyways here’s an actual illustration by Araki where Giorno has three legs.

#anime feminist#Anime & Manga#jojo's bizarre adventure#jjba#jojo no kimyou na bouken#hirohiko araki#lisa lisa#jolyne kujo#female characters#feminist critique#gorgeous irene

119 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Welcome to People Reviews, the newest series of content from The Lilin where I put my social anxiety to use by reviewing the kind of people that come within fifty feet of me. Hopefully, this will serve as a guide for social interaction, because there are some freaky-ass people out there that I will literally cross the street to avoid walking past.

For my first series of reviews, we’re going to a place where you can find some of the best and some of the most uncomfortable people involved in fandom — the convention. In my six-years of con-going, I’ve seen a lot, and by a lot, I include the time this really drunk dude started pissing in the corner by the elevator and then proceeded to chase me and my friends around our hotel. (Anime Boston 2012, if you were wondering.) But there seems to be a common cast of characters that go to cons, and I’d like to take this opportunity to give a shout-out to the best and the worst types of these people.

The Glomper

Verdict: Call con security

First up is a con-goer whose notoriety is well known amongst cosplayers, mythologized through convention horror stories and cautionary tales that advise one avoid this menace by all means necessary. The Glomper is a bull in a China shop characterized by their over-excitement, penchant for high-pitched squealing, and an astounding inability to keep their hands to themselves. “Personal space” is a non-existent concept to the Glomper, as evident by the fact that the worst of them will literally linebacker-tackle cosplayers into something violently resembling a hug. The destructive power of the Glomper has seen injuries sustained and cosplays critically damaged, and their general lack of self-awareness makes the destruction they cause a special kind of infuriating. Being bumrushed by some girl in a tangled Miku wig is frightening, but being bumrushed and having a piece of your cosplay broken (be it commissioned or made with your own two hands) by some girl in a tangled Miku wig is a literal nightmare.

Glomping is just a generally inexcusable action in my book, and I’m sure I speak for everyone when I say I don’t want strangers coming within at least a foot of me, let alone climbing all over me. I don’t care how excited you are to see a really amazing Edward Elric cosplayer, don’t jump all over them and don’t tackle them. This goes double for cosplayers with props that can be broken or outfits that can easily turn into wardrobe malfunctions. A good rule of thumb is to treat cosplayers the same way you’d treat fine art in a museum: don’t touch them.

Although campaigns such as Cosplay is Not Consent have raised awareness on the amount of harassment and unwanted attention that goes on at cons, this conversation still seems to be falling on deaf ears for serial-Glompers and attendees with wandering hands. If you ever find yourself accosted by a Glomper, my best advice is to do your best impression of the prison guards on Arrested Development.

youtube

The “Don’t I get a hug too?” Guy

Verdict: Get the hell away from me

While the Glomper’s method of attack is a weeaboo blitzkrieg, not all creeps launch immediate assaults of misbehavior on unsuspecting cosplayers. Creeps are, first and foremost, creatures of persistence, and the next subject of review is no different in his subtle approach to entitlement.

Cosplayers are frequently stopped at cons for pictures, compliments, or a brief conversation on how enjoyable a certain series or character is. And this is all fine and dandy — especially if you’re something of an attention whore like myself — and most cosplayers WANT you to (politely!) ask them for photos and whatnot. However, there’s one phrase in particular we dread hearing, often uttered just as we’re about to be on our way because we’ve got merch to buy, panels to go to, and weirdos we’d like to avoid: “Don’t I get a hug too?”

The “Don’t I get a hug too?” guy is an embodiment of male entitlement at cons — a humanoid plague of discomfort and a general, mouth-breathing creepazoid who nobody wants to hug, thank you very much. This dude can be a skeevy photographer, a third-wheel in a friend group that obviously wants nothing to do with him, or just some rando out of nowhere who’s suddenly grilling you on how well you actually know the series you’re cosplaying from. A photo-op and a friendly smile don’t cut it for him because he’s under the impression that all the girls dressed up in revealing (a.k.a. accurate) outfits are there for him to enjoy. Being an adult man, glomping is too risky for him to get away with, and so he uses the discomfort and guilt laced in the aforementioned phrase in hopes of receiving real human contact from someone dressed as his waifu.

The good news is that if you ever find yourself in this situation, a hard “no” is usually enough to get this guy to back the hell up. Stand your ground, be firm, and know that the only one entitled to your attention is yourself. Don’t be afraid to cut the politeness if this guy can’t take “no” for an answer, and if he still persists on getting a hug out of you, it’s time to involve con security.

Remember kids, if you can’t learn to keep your hands to yourselves, you may have to get used to spending your con in anime jail.

The Shirtless, Ripped Cosplayer (Saxophone Playing Optional)

Verdict: I’m single, hit me up

I’m a firm believer in “if you like what you got, flaunt it,” both because body positivity is a valuable resource and because every time Chris Evans puts on a really tight shirt an angel gets its wings. Cons are no exception, which is why really buff dudes cosplaying without shirts on really speaks to me as both a feminist and a thirsty bitch. There’s a trend a cons wherein really ripped dudes will cosplay buff/shirtless versions of characters who’re neither regarded as “sexy” or “shirtless” in canon. As far as I know, most cons have some version of this guy. If you’re a frequent attendee of East-cost cons, you’re probably familiar with sexy Professor Layton a.k.a. this guy:

Via.

Sometimes these guys go around playing “Careless Whisper” on the saxophone, which is always a talent to be appreciated at cons (even if it’s just to drown out the screams of “MARCO POLO”).

youtube

Aside from the value these cosplayers provide to the underserved female gaze, it’s also nice to see guys sexualizing certain characters with the same absurdity usually saved for the average comic book/video game/anime heroine. Like, dudes will sexualize just about anything on any kind of female character, so if we’re gonna talk about cosplay in terms of gender equity, I think it’s more than fair to celebrate all the scantily-clad Professor Oaks running around your local con showing off how much they can bench.

The only reason I’m giving these shirtless, buff cosplayers 4 ½ Shinji heads rather than the full 5 is because none of them have exchanged numbers with me yet, and I’d really like to date a guy who looks like a real life JoJo character before I die. I have no choice but to deduct half a star for this serious transgression, but hey, if you guys want the full credit, please call me.

The Over-Enthusiastic Audience Member

(4 if they’re funny, 2 if they’re not, resulting in an overall 3 average )

Verdict: Unless it’s something funny, shut up

It’s only common sense that putting a bunch of nerds and weeaboos in the same room together will result in a pent-up orgasm of enthusiastic geekery. Be it a panel, a screening, or a cosplay game, an audience at a con usually means tons of people yelling fandom-related memes to nobody in particular. Much like your local screening of The Rocky Horror Picture Show or The Room, the audience participation of fans can be fun to be a part of, although I don’t recommend throwing toilet paper or spoons at people running a History of Memes panel. (However, yelling, “You’re tearing me apart Lisa!” is always encouraged.)

However, there’s always gonna be someone in the audience that genuinely doesn’t know when to shut up. This can be super annoying at informative panels or screenings (especially premiers) — you know, stuff you’re trying to hear. And sometimes these Mystery Science Theater 3000 wannabes are Daniel Tosh-levels of not funny, like when I went to a JoJo panel at Anime Boston 2016 and some white guy behind me kept dropping the n-word with every damn reference he made.

But then there are the audience members whose “enthusiasm” is really just good old fashioned heckling. Rather than saving their complaints for the con feedback panel, these folks make it abundantly clear to anyone with ears that they’re not entertained. Heckling is certainly obnoxious to anyone within this person’s general vicinity, but it’s even worse for the people on stage to listen to, especially participants in cosplay games. Heckling was a serious issue at Anime Boston 2015’s Cosplay Chess, wherein I was a queen piece as Asuka Langley Soryu. Long story short, some mistakes were made by the chess masters early in the game over where certain pieces could go, which is whatever. It’s a preplanned entertainment show people, not a legitimate chess match. But getting shouted at by the audience made it really hard for cosplayers to hear the commands of the chess masters and staff on stage, which inevitably led to more mistakes and more angry audience members screaming, “UH, YOU CAN’T GO THERE!”.

youtube

Anyways, the bottom line is to be aware of your surroundings if you’re gonna be the funny guy in the audience. Yes, we get it, you’re having a good time and you still think “tits or gtfo” is hilarious content in the year of our lord 2016. But please, don’t let your excitement (or terrible sense of humor) impede on other people’s experience, and for crying out loud, don’t heckle performers on the stage. Control yourself.

15 notes

·

View notes

Photo

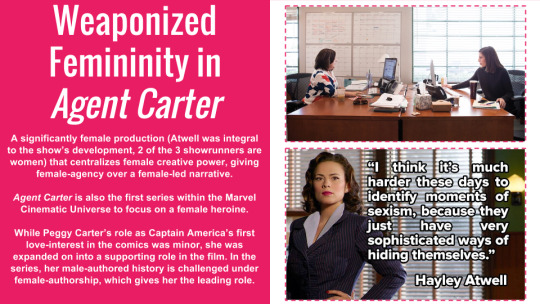

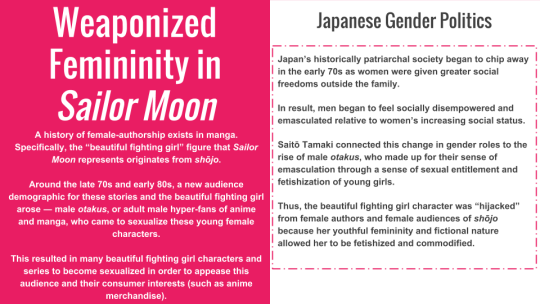

When you all last heard from me, I wish finishing up a semester-long research project on the trope of weaponized femininity in female-authored works for young women, which I focused on the now-cancelled Agent Carter and everyone’s favorite magical girl series, Sailor Moon. I’m happy to say that I finished the project (with a twenty-one page essay), and have since graduated from Simmons College with my bachelor’s degree (yay).

Because my research was big enough to consume the final semester of my college career, I still have a lot of ideas and after-thoughts lingering in my head. One such area I spent a lot of time looking into was the gendered dynamics found in comic and anime/manga culture — mostly the gender inequity in creators and audiences. I think we all know by now that these forms of visual media tend to cater to dudes. The fact that so much from comics and anime/manga centralizes on male experience just proves how much of a significance we’ve placed on guys as both consumers and producers of these works. Meanwhile, anything that’s female-focused usually goes undervalued, cancelled (Agent Carter), or taken over by a minority of male-fans who just want to jack-off to stuff made for young girls (the magical girl genre and My Little goddamn Pony).

But dudes — and by “dudes” I mean cis men — are hardly the ones producing fan-created content like fan fiction, fan art, and cosplays. From my own observations, the majority of this sort of stuff seems to be generated by girls and — more recently, especially on Tumblr — trans and non-binary folks. But the fact that others have picked up on these gendered trends in fan-created content convinces me that I’m not seeing things from inside a bubble.

So much of fan-culture is reliant upon fan-involvement, and these communities would be little without the fan-works they generate. I’m sure I speak for everyone here when I say I wouldn’t be involved in half of the fandoms I’m in if it weren’t for the kind of content its fans were producing. And people literally come up with the craziest, most brilliant shit ever. Then again, my standards of “good shit op” include stuff like It’s Always Sunny in Philadelphia parodies, 10,000+ word smut fics, and badly rendered MMDs set to Sandstorm.

Yet fan-made content has a strongly gendered history that can be traced back to the emergence of modern-day fan fiction from female Star Trek fans. Women were creating fanzines of Spock in 1967, and the slash-genre (which is, again, dominated by women) grew out of female fans really wanting Spock and Kirk to make-out. Hell, Star Trek fan fiction is where the Mary Sue archetype originated, named after the satirical(?) reader insert character in “A Trekkie’s Tale” by Paula Smith.

Because Star Trek defined the participatory culture of fan communities, many academics have looked to it to analyze the phenomenon of fan fiction, particularly its gendered production and consumption. As far back as 1986, scholars such as Camille Bacon-Smith and Henry Jenkins III were noting that up to 90% of fanfic writers were women (90). These numbers remain consistent some thirty-years later, with a 2013 census of Archive of Our Own (AO3, a.k.a. where all the quality works from FanFiction.net went) finding that 80% of its respondents were female while 16% identified as trans or non-binary. (And guys? Only 4%, if you were wondering.)

Many theories have been put forth as to why fan fiction is so dominated by women. Jenkins attributed it to the gendered differences in socialization that dictate how fans participate, as well as noting that women’s interests in playing with a story’s content stems from (surprise!) their generally erasure from narrative texts to begin with. Because women are often forced into “identifying with male characters in opposition to their own cultural experiences” of gender, Jenkins believed that there was a “need to reclaim feminine interests from the margins of masculine texts,” which could be done through the speculative nature of fan fiction (91). If you can write whatever you want, then why not write the story you ultimately want to be told? Additionally, Jenkins noted that fan writing resembles the “forms and functions traditional to women’s literary culture,” wherein women shared and exchanged personal writings (diaries, letters) as a means of self-expression and community (91-92).

Guys aren’t the ones running kinkmemes or penning novel long, omega-dynamic Stucky fanfics. Take it from me, as someone who’s written her fair share of fan fiction in her free time — this is female-fronted terrain.

And what about fan art? Sure, guys may make up the majority of artists and creators in the industry, but a lot of the stuff about fan fiction being heavily non-male applies to fan art as well. Like fan fiction, it’s easier for fan art to reach a wider audience these days thanks to social media, allowing artists to share their work without the industry’s involvement. It only follows that female, trans, and non-binary artists would find fan communities more welcoming as consumers of their work.

The gendered dynamics of NSFW fan art is also something I want to briefly mention. Is it just me, or is it painfully obvious when NSFW stuff is made by dudes? Fan art does provide a better representation of the male gaze than fan fiction, so it isn’t hard to tell when something is being sexualizd from the perspective of a male author versus a female author. Content wise, male fan artists tend to enjoy inaccurate boob physics, plots straight out of porn, and, for some god forsaken reason, drawing their Rule 34’s in the same style as the work they’re corrupting.

(Side question: Why does NSFW art of The Simpsons show up in practically every Google image search? How is this a thing? I’m accepting answers right now in the comments.)

Meanwhile, fan art by non-male artists (both SFW and NSFW) tends to avoid the sexualizing techniques of the male gaze by turning the sexualization onto male characters themselves. And if any of you remember the Hawkeye Initiative, this strategy can come with a political message on representations of gender. Similar to Jenkins’ observation, blogger Britta Lundin for Worship the Brand notes, “by sexualizing men and empowering women, fan artists are reversing the power dynamic we usually see. In this way, we see how transformative works like fan art and fanfiction can be a corrective force, ‘fixing’ problems, and equalizing the playing field.”

Although most fan art is free, commission work and selling pieces in artist alleys at cons does offer an opportunity for these artists to make some money outside the industries themselves. While it’s true that copyright laws generally dictate that fan artists cannot make a profit off of their work, the fact that many of these artists are non-male also raises the question of a wage gap for artists. Whereas the men working as animators and comic artists earn salaries for doing shit like turning Captain America into a goddamn Nazi, fan artists are producing their own quality works for nothing.

And cosplay? As someone who’s gone to her fair share of cons, I can confidently say that male cosplayers are a distinctive minority. Research has shown that more female-identified folks cosplay more than men, and that includes cosplaying both female and male characters. If I had to make a guess based on my six-years of con-going experience, I’d say that for every cis male cosplayer, there’s probably between five and ten non-male cosplayers. Why guys don’t participate in cosplay as much, I don’t know, but I honestly wouldn’t be surprised if it had something to do with transphobia and sexism dictating that dressing-up in costumes is somehow un-masculine.

So the question stands, why do we give guys so much credit and entitlement within fan culture? Why are guys viewed as the quintessential fan while women, trans, and non-binary folks are either mocked or disregarded all together?

Based on the research I did for my weaponized femininity project (particularly in regards to the gendered history of otaku culture), I believe it has a lot to do with male fans being considered the main market group of nerd stuff, both the works themselves and the merchandise they spawn. Guys have historically possessed more spending power than their counterparts thanks to stuff like their longer participation in the workforce and the wage gap working in their favor.

(And no, I’m not about to stop this piece to start arguing about the logistics of the wage gap. All I’ll say is that it isn’t a myth and if you still want to engage me in an argument about it, you can send me $50 to my PayPal and I’ll gladly entertain you with a twenty-minute debate.)

Even the ways in which merchandising is marketed favors male consumers. We’re more than familiar with the absence of female characters from toys based on franchise films, and the sexism problem this trend indicates points to how strong the assumption is that girls aren’t a valuable consumer group.

It seems that the media industry prioritizes its consumers and fans based on monetary value. We’ve come to associate the success of works based on how much money audiences are spending rather than the critical response it generates. Like, why else do you think that live-action Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles movie got a sequel? Critics hated it, but apparently 400 million dollars worth of audiences wanted to watch bad CGI turtles that look like what would happen if you transmuted Shrek and Andre the Giant into a chimera.

If we’re going to give proper credit to fan culture’s participants, we clearly need to adjust our perception of what indicates a work’s success. Making a profit is certainly important, but money doesn’t necessarily represent the interests of audiences. Afterall, people are willing to spend absurd amounts of money on garbage. The participatory culture in fan communities may not generate a market value, but it’s crucial to generating consumer interest and keeping audiences engaged.

With female, trans, and non-binary fans so heavily prevalent in fandom, we cannot afford to overlook the importance of their contributions any longer.

It’s simply not fair.

#Anime Feminist#feminist critique#feminist media criticism#fandom#fan culture#Fanart#fanfiction#cosplay#Anime & Manga#comics#merchandise#participatory culture

35 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Hi everyone! At this point, I’m approximately half-way done with my paper (it’s over 12 pages at this point, woah), and since I plan to get it published in a scholarly journal, I won’t be posting it on here. But I did give a presentation based on my research at Simmons College’s undergraduate symposium this past Wednesday.

Subjects of my research

Agent Carter

The ABC series Marvel’s Agent Carter, which is a spin-off of the Captain America film series focusing on Agent Peggy Carter, a skilled agent for the Strategic Scientific Reserve and the right-hand-woman/love interest of Captain America, as she struggles to prove herself in the sexist society of post-World War II America.

Sailor Moon

A Japanese magical girl anime and manga series that follows 14 year-old Usagi Tsukino, a.k.a. Sailor Moon, and her friends who upon awakening with the power to transform into a team of superheroines, known as the Sailor Guardians, fight for love and justice in order to protect the Solar System.

What is weaponized femininity?

A trope commonly found in female action heroines wherein their femininity is retained alongside masculine demonstrations of physical or mental strength, or functions as something to be manipulated as a tool of empowerment.

Its juxtaposition of masculine power with traditional femininity presents the feminine and the feminine-subject as active agents capable of undermining patriarchal power as well as cultural assumptions of girls and young women.

Offers resistance to what feminist film theorist Laura Mulvey called the “active-male/passive-female dichotomy” of gendered power on film, wherein men are depicted in active roles that bestow them with agency within a narrative, whereas women in film serve as objectified, sexually titillating spectacles for “the male gaze” of the male audience.

Although hyperfeminine action heroines and female characters who manipulate the terms of their femininity have been the subject of feminist media scholars for years, there is currently no academic scholarship on the trope of weaponized femininity itself. This is because the term “weaponized femininity” is a neologism that began circulating around the feminist blogosphere around 2013. Thus, I was tasked with giving this concept validity as a trope in and of itself.

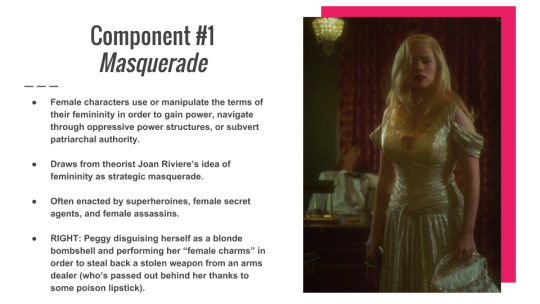

Component #1 - Masquerade

Female characters use or manipulate the terms of their femininity in order to gain power, navigate through oppressive power structures, or subvert patriarchal authority.

Draws from theorist Joan Riviere’s idea of femininity as strategic masquerade, wherein “womanliness…[can] be assumed and worn as a mask” to hide a woman’s possession of masculine strength.

Often enacted by superheroines, female secret agents, and female assassins, who perform a carefully constructed feminine identity in order to infiltrate the unsuspecting male sphere.

Component #2 - Destability of Gender Assumptions

Wherein hyperfeminine female characters demonstrate physical and/or mental strength on par with men.

The physical power and mental strength of these feminine subjects stands in opposition to cultural assumptions of female passivity, refuting assumptions of appropriate gender roles by unifying feminine appearance and masculine toughness.

This iteration of weaponized femininity is frequently found in the young girl action heroine, who offers transgressive potential through her unique combination of physical power with stereotypical youth and femininity.

While the young girl action heroine has been featured throughout Western media ― The Powerpuff Girls (1998 - 2005), Hanna (2011), and The Professional (1994) ― she has proven to be a cultural phenomenon throughout Japanese anime and manga in the form of “the beautiful fighting girl” (sentō bishōjo), young heroines whose “pure and lovable girlishness remain intact” while they do battle and fight to save the world.

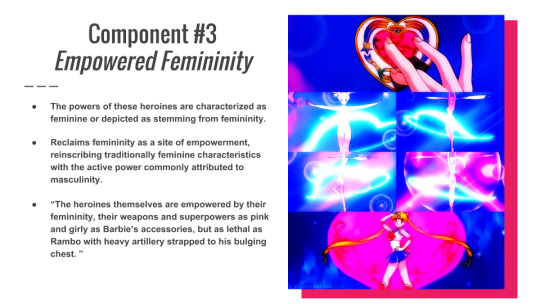

Component #3 - Empowered Femininity

The powers of these heroines are characterized as feminine or depicted as stemming from femininity.

Constitutes a reclamation of femininity as a site of empowerment, reinscribing traditionally feminine characteristics with the active power commonly attributed to masculinity.

“The heroines themselves are empowered by their femininity, their weapons and superpowers as pink and girly as Barbie’s accessories, but as lethal as Rambo with heavy artillery strapped to his bulging chest. ”

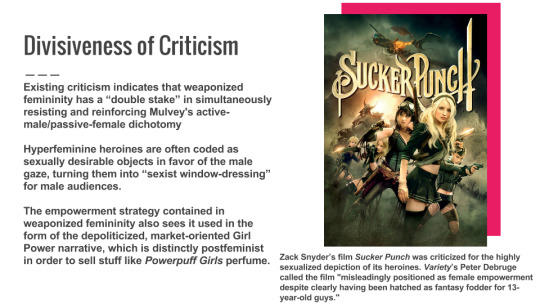

Divisiveness of Criticism

However, feminist criticism towards these feminine action heroine attests to the weaponized femininity trope having a “double stake” in simultaneously resisting and reinforcing Mulvey's active-male/passive-female dichotomy

The degree in which these hyperfeminine heroines are coded as sexually desirable objects sees the trope working in favor of the male gaze, presenting their resistance to female passivity as “erotic spectacle” and turning them into “sexist window-dressing” for male audiences.

The empowerment strategy contained in weaponized femininity also bears likeness to the neoliberal “tropes of freedom and choice” contained in postfeminist ideology. Thus, the trope often takes the form of the depoliticized, market-oriented Girl Power narrative that presents surface-level feminist rhetoric in commercial, apolitical ways.

Zack Snyder’s (Dir. Batman vs. Superman) 2011 film Sucker Punch was subject to criticism for the highly sexualized ways in which its heroines were depicted. Variety’s Peter Debruge called the film "misleadingly positioned as female empowerment despite clearly having been hatched as fantasy fodder for 13-year-old guys."

My Argument

As valid as these criticisms are, most of them fail to take into account the influence that female-authorship and female-readership/audience have on the trope’s images. Male agency over these narratives is assumed, and thus depictions of female sexuality constructed by female creators can be conflated with sexual objectification.

Mulvey’s theory of the male gaze specifically notes that these sexist images of women are the products of male production and the privileging of male audiences.

Furthermore, for feminist scholarship on Japanese anime (particularly Sailor Moon), theorists tend to apply strictly Western concepts of gender and feminist theory (such as Girl Power) onto these culturally Eastern narratives. This also ignores the fact that there is a rich history of female authorship to be found in Japanese manga.

I my paper I examine how female authorship and an explicit focus towards female audiences influence depictions of weaponized femininity, which I propose give female characters greater agency, subverts sexual objectification, and reinserts feminist gender politics back into the trope itself.

Weaponized Femininity in Agent Carter

A significantly female production that centralizes female creative power, giving female-agency over a female-led narrative. Not only was Hayley Atwell integral to to show’s development but she’s an outspoken feminist herself who’s emphasized the political nature of her character.

Additionally, two of the three showrunners are women - Tara Butters and Michele Fazekas.

Agent Carter is also the first series within the Marvel Cinematic Universe to focus on a female heroine, and was also developed out of response to feminist criticism that the Marvel series was sidelining female characters. To this date, this series and Netflix’s Jessica Jones are the only two female-led series to exist.

While Peggy Carter’s role as Captain America first love-interest in the comics was minor, she was expanded on into a supporting role in the film. In the series, her male-authored history is challenged under female-authorship, which gives her the leading role. In this way, you can say that women really reclaimed Peggy as their own!

The show’s 1946 setting sees the trope politicized against post-war sexism and misogyny, at a time when women were being forced back into the home and gender roles were being re-established.

Despite her credentials, Peggy is dismissed by her male peers at the S.S.R., who demote her to secretarial duties and exclude her from field work.

In order to clear the name of her War-friend Howard Stark, Peggy is forced to use her femininity as masquerade in order to navigate institutional sexism and conduct her own investigations.

The show’s emphasis on post-war sexism simultaneously serves to provide a metacommentary on the erasure of women from the comic book industry, which began after men returned from the War and pushed women out of the workforce. This resulted in the cancellation of many superheroine comics and superheroine characters being demoted to either love-interests or minor, unsuper roles.

Similarly, Peggy is dismissed by her male colleagues as nothing but Captain America’s “gal”, and the erasure of women from comics is paralleled via the character Betty Carver, Peggy’s fictionalized counterpart on the radio show “The Captain America Adventure Program,” which demotes her role in Captain America’s story the core and powerful ally he revered to a gushing, damsel-in-distress.

Weaponized Femininity in Sailor Moon

Created by Naoko Takeuchi, a female manga artist, who created the series specifically for young girls, because she saw a lack of female characters in the male-dominated super sentai (Japanese superhero team) genre.

Is a genre-hybrid of shōjo (manga aimed towards young women), mahō shōjo (magical girl), and super sentai. But falls in the realm of what Japanese psychologist and media scholar Saitō Tamaki calls the “beautiful fighting girl” character.

Takeuchi consistently places the experiences of Japanese girls and young women at the story’s forefront, reflecting shōjo’s history of politicizing girl’s experiences (sexuality, gender, etc.).

A history of female-authorship exists in manga. Specifically, the “beautiful fighting girl” figure that Sailor Moon represents originates from shōjo.

Around the late 70s and early 80s, a new audience demographic for these stories and the beautiful fighting girl arose ― male otakus, or adult male hyper-fans of anime and manga, who came to sexualize these young female characters.

This resulted in many beautiful fighting girl characters and series to become sexualized in order to appease this audience and their consumer interests (such as anime merchandise).

Japanese Gender Politics

Once a patriarchal structured society, Japan in the early 70s saw a change of gender roles as women were given greater social freedoms, such as the ability to make their own marriage decisions.

However, this resulted in a sense of male anxiety and emasculation, and men began to feel socially disempowered relative to women’s increasing social status.

As Saitō Tamaki notes, this change in gender roles informed a sense of sexual entitlement and fetishization of young girls, who are still relatively bound within Japan’s age-based social system (one which expects conformity from children and prioritizes seniority.

Thus, the beautiful fighting girl character was “hijacked” from female authors and female audiences because her youthful femininity and fictional nature allowed her to be easily fetishized.

The agency over the narrative allotted by female authorship sees the trope used to subvert the Madonna/whore dichotomy, as Sailor Moon’s power is sourced in her “pureness of heart” and yet, while being a clutzy, crybaby of a teenage girl, she’s allowed to be a sexual being and have ownership over her own desires.

The very concept of weaponized femininity is also queered through the number of characters who express/engage in non-heterosexual love (the lesbian relationship between Sailor Uranus and Sailor Neptune) or are depicted as having a fluid gender-identity (Sailor Uranus and the gender-bending Sailor Starlights).

When asked why she included such a non-fetishized depiction of lesbians in the series, Naoko Takeuchi stated, “There's not only heterosexual love, but there also can be a homosexual love, in this case between two girls."

So, not only does this queerness work to destabilize the notion of female essentialism in weaponized femininity, but this form of queer representation remains radical even in 2016 Japan, which is still very behind in terms of extending anti-discrimination and marital rights to LGBTQ citizens.

#weaponized femininity#feminism#feminist media#feminist media criticism#sailor moon#agent carter#laura mulvey#naoko takeuchi#beautiful fighting girl#action heroines#simmons college

2K notes

·

View notes

Photo

To be completely honest, I’ve been going through some perpetual burnout what with all the things I’ve been doing for the last month. Between class work, job searching, student leadership activities, and figuring out what I’m supposed to do with the rest of my life following graduation, I’ve been functioning on fumes.

But hey, the good news is that things are starting to really come together in terms of this project now that I’ve sent my abstract off for the undergraduate symposium, and I hope to have started working on my draft sometime by the end of this week. I’m almost finished organizing all my notes, which I should have done with a clear outline of what my paper will look like by the middle of this week.

Leading up to now, I’ve come to find that the conversation on female authorship and female readership over weaponized femininity as it pertains to Agent Carter and Sailor Moon will require me to pull together a ton of threads, but I’m confident that all these threads will allow me to make a very intricate and solid case.

For one, the use of weaponized femininity in Agent Carter is politicized in accordance to its setting in 1946, and the postwar push of women out of the workforce and the reinforcement of rigid gender roles is central to the series’ commentary on sexism and misogyny. Despite her credentials as a war veteran and Captain America’s right-hand “man,” Agent Peggy Carter is dismissed by her male colleagues on the basis of her gender and relegated to secretarial duties while they go out and ensure the safety and security of the postwar United States. The structures of sexism and misogyny at play during this time period require Peggy to use her femininity as a form of masquerade ― if she’s going to work in ways that undermine and challenge these oppressive structures, she’ll need to appear as if she’s playing by the rules of gender roles: disguising herself as a seductive blonde bombshell in order to steal back a dangerous weapon from a chauvinistic arms dealer, performing the role of the ditzy secretary to her (completely unqualified) male colleagues in order to throw them off her trail while she conducts her own investigations.

While it was clearly the production’s choice to use weaponized femininity as a means to explore sexism through postwar sexual politics, what I found truly remarkable in my research is that this postwar setting also serves as the location of a metacommentary on the erasure of female heroines from the Golden Age of comics. While critics have lauded Agent Carter for paving the way forward for more television and film adaptations of female comic heroines, many have noted that the series also serves to shed light on the lost history of superheroines and the push of women out of the comic book industry, which, not coincidentally, took place after the end of World War II. Throughout the show’s first season, there’s a running gag of a radio-play about Captain America wherein Peggy and her crucial role on Captain America’s team during the war are reduced to the fictional character of “Betty Carver,” Captain America’s love-interest and a helpless damsel in distress. Funnily enough, many superheroines that grew to prominence during the war were quickly downgraded to the roles of powerless love-interests or side-characters. Additionally, the re-entry of men into the comic industry shut down a significant portion of production companies that had been established during the war because they had mainly employed women, and those women were the main producers of superheroine comics.

Additionally, the plot surrounding the first season’s villains sees weaponized femininity yet again used as a means for political commentary, this time through presenting little girls and young women as the perfect assassins because they are often “overlooked, taken for granted” and their femininity allows them to “slip easily through a man’s defenses” (Episode 6).

While my analysis of how female authorship and female readership allow weaponized femininity to be used in politically feminist ways in Agent Carter will largely depend upon its meta-commentary of postwar sexual politics and the lost history of women in comics, the analysis I’ll give on Sailor Moon will require me to connect its Japanese cultural context to the radical representation it gives to LGBTQ characters.

My biggest difficulty in conducting research on Sailor Moon is that so much of the academic scholarship on the series by Western feminist media critics is just downright culturally imperialist. They’re always applying Western conceptions of gender and feminist politics to where they don’t belong, and thus there’s a complete misreading of Sailor Moon as gender essentialist, sexualized, and apolitical because they never take into account the fact that, as a Japanese work, it’s a product of a different cultural context and set of gender politics. While my prevailing argument for this entire project is that prior scholarship on weaponized femininity has failed to take gender authorship and gendered readership into account, this is incredibly apparent in the existing academic scholarship on Sailor Moon. They either give little to no acknowledgement of Naoko Takeuchi’s role as series creator or base their analysis entirely on the first English dub of the 90s anime by DiC, which is notorious for its extreme censorship of LGBTQ themes and sexuality, Americanization for an elementary-age audience (as opposed to the original’s intention for girls, teens, and young women), and adaption to fit the Girl Power discourse that was taking shape in American pop culture and consumerism.

There’s a tradition of female authorship in the shoujo genre that Sailor Moon emerged from, and that genre is characterized by the desire for stories that spoke to the experiences of girls and young women in Japan. The beautiful fighting girl character that’s come to proliferate Japanese animes and manga also has her roots in the female-authored and female-consumed works of the shoujo genre. However, around the late 70s and early 80s, a new market of consumers arose ― the male otaku, adult male hyper-fans of anime and manga who came to fetishize and sexualize beautiful fighting girls, and their growth into the main consumer market for anime and manga resulted in many beautiful fighting girl characters and stories becoming sexualized in order to appease this audience. This section will also require me to give a brief explanation of how the sense of male anxiety and emasculation that resulted from changes in Japanese gender roles thus informed the sense of sexual entitlement and fetishization to young girls throughout Japanese society and male otaku culture.

Sailor Moon was conceived of as Naoko Takeuchi’s reaction to the dismissal of female representation that spoke to female experience throughout anime and manga, as she specifically created the series in reaction to the male-dominated action team genre, particularly the Super Sentai series, a.k.a. Power Rangers. Sailor Moon was created by women for women, as evident in how the weaponized femininity of the sailor senshi operates upon the female experience of Japanese girls and young women, which Takeuchi used as a vehicle for some revolutionary sexual and gender politics. For one, the simultaneity of Sailor Moon’s sexuality and the power that arises from her pureness of heart directly subverts the Madonna/whore dichotomy. But more than that, the heart of this series’ feminist political potential lies in Takeuchi’s desire to portray and normalize same-sex desire (particularly the lesbian relationship between Sailor Uranus and Sailor Neptune) and the extent to which a definite transgender narrative is evident in how Takeuchi plays with gender (the masculine Sailor Uranus and the gender-fluid Sailor Starlights).

Okay, so this blog entry ended up being a lot longer than what was probably wanted, but what I’ve basically done is summarize how I will go about my analysis of Agent Carter and Sailor Moon, which I’ll contain to approximately 10 to 12 pages, while I’ll use the first three to five pages to give a definition of weaponized femininity and a summary of the two divisive readings of the trope in contemporary feminist criticism (which is where I’ll draw from my bibliographic essay).

6 notes

·

View notes

Photo

So first off, I’ve made the (questionable?) decision to present this project at Simmons College’s undergraduate symposium. I’m purely operating off of the idea that if I keep myself busy then I’ll remain productive towards stuff like other course work, finding a post-college job, apartment hunting, so on and so forth. Gotta prevent those existential meltdowns anyway you can.

This blog entry/project update is to give the rundown on the finalized focus of my project. Having used Katharine Kittredge’s article as the starting point of my research on weaponized femininity, I found myself constantly thinking about how seldom the role of authorship and audience is taken into account in analyzing how this trope functions. Along with comparing how the girl assassin archetype functions on the basis of cultural context (comics/films vs. manga/anime), she looked at the role of male authorship over these works as well as their aims towards a young male audience.

While going through some of the research and criticisms already done on works that use weaponized femininity, the fact that certain works are authored by (or majorly by) women for a female audience is completely glossed over, and thus the importance of female agency in reading weaponized femininity as purely exploitative or objectifying.

And that’s where we get accusations that Sailor Moon is nothing but a slut reinforcing the objectification of young girls in Japanese society, completely ignoring the fact that its creator is a woman who explicitly created the series for a young female audience, that the shoujo genre itself was practically hijacked by creepy male otakus, or that female creators can hardly create something for girls without it being fetishized by older men.

From my own personal observations, when works have a high degree of female authorship and are specifically aimed towards a female audience, weaponized femininity is used in such a way that it is explicitly subversive of gender roles. It carries the feminist political potential that is usually erased when the trope is used to be sexually titillating.

To make this argument, I’ll be looking at Sailor Moon and Agent Carter, two series heavily authored by women with a specific aim towards a female audience, reflecting the comparisons Kittredge made between Kick-Ass and Gunslinger Girl based on their Western and Eastern origins.

(Though to be honest, I’ll take every opportunity I can to do scholarly work on anime.)

I’ll be analyzing each respective work based on how their cultural contexts inform gender politics (particularly the post-war push of women out of the work force in the case of Agent Carter), author intent, and audience response to show just how weaponized femininity can realize its political potential.

In order to save myself some time (and much needed brainspace) on this project, I’ll specifically be looking at the first season of Agent Carter and Sailor Moon Crystal (overly blown out of proportion animation errors aside, it’s a faithful adaption of the manga, and the original television anime had less production input from women).

While a good deal of my research will consult academic scholarship, I find it crucial to include non-academic, feminist criticisms of weaponized femininity and both shows, as the term “weaponized femininity” itself did originate from the blogosphere. Furthermore, this generation of feminists have been vocal about reclaiming female characters through criticism of the ways in which fandoms marginalize female characters and by rewriting female characters in terms of feminist gender politics. At the level of fandom, there’s some serious feminist discourse going on to make space for women and LGBTQIA creators and fans.

Along with my presentation at the undergraduate symposium, this project will result in an 8 to 10 page paper and a bibliographic essay on works I’ve consulted for my research.

Because I’m on spring break right now and trying to do as much of nothing as I can before the rest of the semester kicks my butt, I’m going to leave this update off here, and will come back ready with some thoughts on Beautiful Fighting Girl and Agent Carter.

6 notes

·

View notes

Photo

For this update on my research endeavor, I thought I’d break down one of the most important (and pressing) obstacles I have encountered over the past few weeks, mainly because that’s the assignment this week for my English seminar.

One of the key challenges to this process has been in putting together a definition of weaponized femininity to work off of. As I mentioned in a previous update post, the term “weaponized femininity” is fairly recent. While it’s a familiar term to those involved in the feminist blog-o-sphere, the word hasn’t made its way into academia yet, although the components of what would be considered as weaponized femininity have been studied and criticized for as long as feminist media studies have been a thing.

But seeing as the word itself originated (or at least gained validity as a term) in the blogging realm, I turned to the internet to provide me with a basic definition of weaponized femininity that I could use to narrow down my search in academic resources. This is when I came across this text post by @hotelsongs posted in March of 2013:

Putting aside the parts of this post concerned with the lack of coherent understanding within the feminist community of the effectiveness of weaponized femininity, I was primarily interested in point 3 of “what it is” and points 1 and 2 of “what it isn’t”. According to hotelsongs’ observations, weaponized femininity is something that is enacted by female (and female identifying) characters. It relies on a reciprocal relationship between the female gender and expressions of femininity, the latter of which is the thing that becomes capable of inflicting “damage”.