#zoology majors rejoice

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

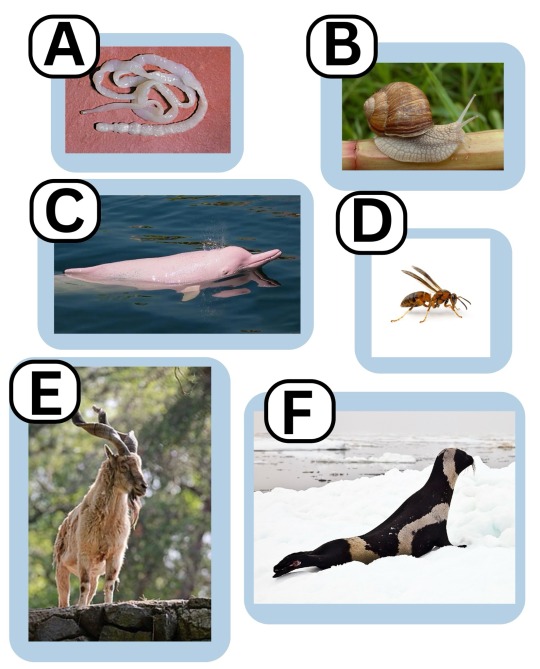

It’s been a while since we’ve done a biology puzzle so I kind of want to play a game I like to call “shopping list” that I play in my head whenever I��m in a waiting room. I’ve tweaked it a little to play as a multiple choice quiz.

The idea of the game is recruiting different animal species (based on name alone) for a certain activity. So for example, if the activity is “playing Dungeons and Dragons” and you see the following animals…

A. Thompsons gazelle

B. Dice snake

C. Goblin shark

D. Crab eater seal

E. African land snail

F. Dragonfly

Then your answer would be B, C, F (for dice, goblins, and dragons).

So let’s try our first one! The activity is…

Gift- wrapping a present

Answer: _ _ _

305 notes

·

View notes

Text

'Medical educators recognized that the decision to study medicine had something to do with personal characteristics, cultural values, and the perceived attractiveness of medicine as a career, though no one could precisely explain medicine's growing popularity as a career or how premedical students might have differed from undergraduates who pursued other fields. Nevertheless, this was of little worry to medical schools, which now rejoiced at being able to conduct medical education on a far higher plane. Students entered medical school already knowing the alphabet of science, which allowed the four years of medical school to be preserved for purely medical subjects. Academic failure became much less common. By the 1930s the national attrition rate had fallen to 15%, most of which occurred during the first year of study. At elite schools that were highly competitive for admission, attrition rates were much lower still.

What course of study should students preparing for medicine undertake? This troublesome issue perplexed medical school and university officials alike. Everyone agreed that in an era of scientific medicine, a college education alone did not suffice. Rather, specific courses were required so that students could begin medical study without having to take remedial work. These consisted of biology or zoology, inorganic chemistry, organic chemistry, and physics. Most medical schools required or recommended courses in English, mathematics, and a foreign language as well.

Beyond these requirements, there was great confusion concerning the best preparation for medical school. Officially, medical school officials espoused the importance of a broad general education, not a narrow scientific training. However, faculties frequently sent the opposite message. This dilemma was illustrated at the University of Michigan. The medical school dean met repeatedly with premedical students to tell them “that the purpose of their preparation was to give them a broad general education.” Yet, the majority of individual faculty at the school believed that “science courses are still paramount for medical students.” James B. Conant, A. Lawrence Lowell's successor as president of Harvard University, summarized the dilemma in 1939: “I realize that many deans, professors, and members of the medical profession protest that what they all desire is a man with a liberal education, not a man with four years preloaded with premedical sciences. The trouble is very few people believe this group of distinguished witnesses. Least of all the students.” Accordingly, the overwhelming majority of applicants applied to medical school having majored in a scientific subject.

Though medical schools sought qualified students, most were not eager to increase the number admitted. Medical deans knew precisely how many students the school's dissection facilities, student laboratories and hospital ward could accommodate. The situation at the College of Physicians and Surgeons of Columbia University was typical. In 1918, to ensure that all students “can be adequately taught and trained” the school reduced the size of the first-year class by one-half. The faculty found this experience “infinitely more satisfactory” than trying to teach larger numbers of students as before. In emphasizing education quality, medical schools were thought to be acting in a socially responsible fashion. Virtually no one in the 1920s or 1930s, inside or outside the profession, thought the country was suffering from too few physicians.

Medical educators and admissions officers debated endlessly how to select the finest candidates from the growing applicant pool: whether to rely on grades, courses taken, letter of recommendation, or the personal interview. Virtually all admissions committees valued that elusive quality of “character,” though no one knew exactly how to define or measure it. To help makes their deliberations more “scientific,” some admissions committees began using the results of the Medical Aptitude Test, a standardized objective test introduced by medical educators and educational psychologists at George Washington University in the late 1920s and recommended for general use by the Association of American Medical Colleges in 1931. However, no instrument of measurement, alone or in conjunction with others, could allow them to determine with confidence which applicants would make the best practitioners or medical scientists. The Medical Aptitude Test could accurately predict which students would achieve academic success during the formal course work of medical school, but not future success at practicing medicine.'

– Time to Heal: American Medical Education from the Turn of the Century to the Era of Managed Care by Kenneth M. Ludmerer

2 notes

·

View notes