#zitkála-šá

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

"I’ve lost my long hair; my eagle plumes too. / From you my own people, I’ve gone astray. / A wanderer now, with no where to stay."

Read it here | Reblog for a larger sample size!

#open polls#polls#poetry#poems#poetry polls#poets and writing#tumblr poetry#have you read this#the indian's awakening#zitkála-šá#gertrude simmons bonnin#native american#sioux#residential schools

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

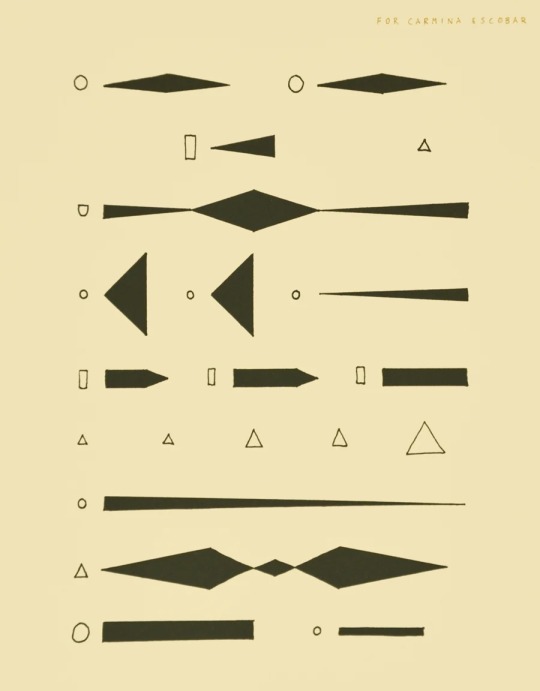

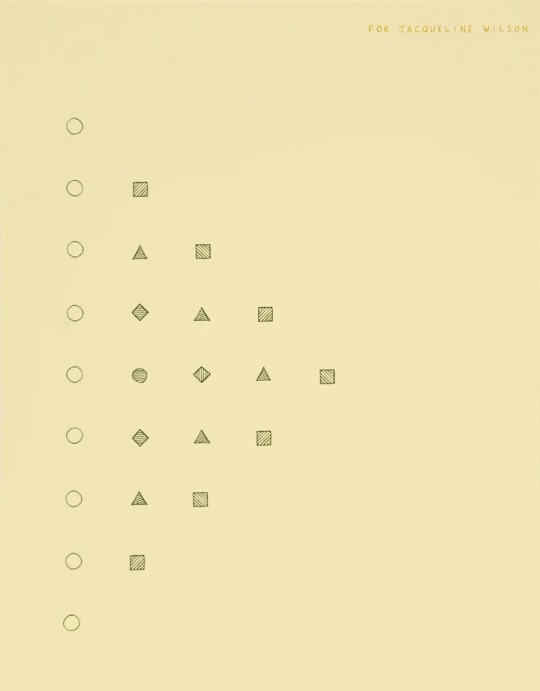

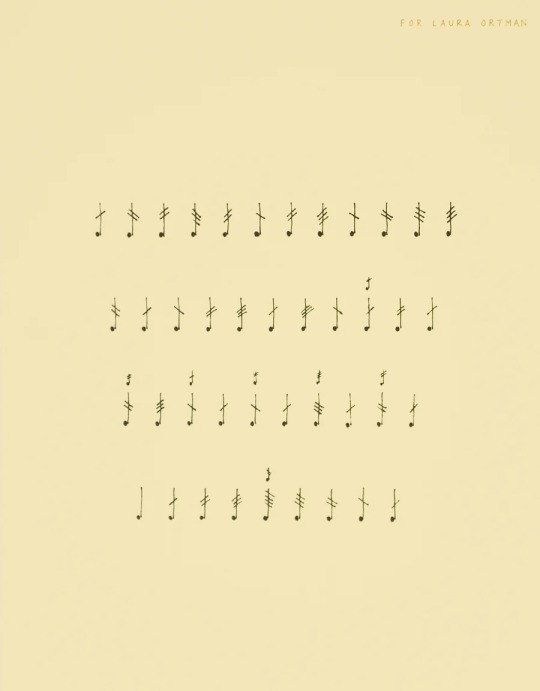

For Zitkála-Šá series

Raven Chacon (Diné)

lithograph prints

59 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Sioux Life Lessons: Iktomi and the Muskrat & Iktomi's Blanket

The Sioux stories known as Iktomi tales concern the trickster figure Iktomi (also known as Unktomi) who appears, variously, as a hero, sage, villain, clown, inept buffoon – or in other roles – but always serves to illustrate some important lesson or provide instruction in cultural values.

In White Plume, he is the villain who tries to steal the hero's identity, and in The Bound Children he is the sage mediating a dispute, but in Iktomi and the Muskrat and Iktomi's Blanket, given below, he is the buffoon who highlights the Sioux values of gratitude, keeping one's promises, and the importance of hospitality.

Other Iktomi tales, such as Iktomi and the Coyote and Unktomi and the Arrowheads present the character in other roles – as a fool who cannot tell the difference between life and death and as a helper and punisher of transgressors, respectively – but these tales, like the many others featuring Iktomi, all serve the same purpose of entertaining an audience while imparting some important life lesson.

Text

The two tales below come from American Indian Stories and Old Indian Legends by the Yankton Dakota Sioux activist and writer Zitkála-Šá (l. 1876-1938).

In Iktomi and the Muskrat, the value of hospitality is highlighted and, for the original audience, would have had special significance as the muskrat is sometimes featured in place of the otter in the Lakota Sioux Creation Story as the first of the animals to dive into the primordial waters to try to bring mud up to the surface to form dry land. The muskrat was therefore associated with creation and the Great Spirit and, because of this, symbolizes wealth, both spiritual greatness and material gain.

When Iktomi refuses hospitality to the muskrat, therefore, he is not just denying a fellow creature a place at his table, but is cheating himself out of whatever gifts he might have received in behaving properly. Further, since the muskrat is so closely associated with the Creator God, Iktomi is essentially insulting his maker to his face.

Iktomi's Blanket focuses on the value of gratitude and keeping one's promises. Inyan, the great-grandfather and gift giver, is one of the four primordial gods along with Han, Maka, and Skan, all aspects of Wakan Tanka – The Great Mystery – and so revered as sacred entities. Inyan is associated with stability, certainty, and dependability, and is symbolized by rock. When Iktomi asks for the gift of food, it is given; but Inyan is just as able to take as to give when the situation warrants, and, in this case, when Iktomi withdraws his gift of gratitude, Inyan responds in kind by taking back the food. Iktomi's effrontery in stealing back what was freely given would also have had a deeper meaning for an original audience in that Iktomi is not just taking unjustly from another but from a god.

Iktomi and the Muskrat

Beside a white lake, beneath a large grown willow tree, sat Iktomi on the bare ground. The heap of smoldering ashes told of a recent open fire. With ankles crossed together around a pot of soup, Iktomi bent over some delicious, boiled fish. Quickly he dipped his black horn spoon into the soup, for he was ravenous. Iktomi had no regular mealtimes. Often, when he was hungry, he went without food. Well-hidden between the lake and the wild rice that grew on its banks, he looked nowhere save into the pot of fish. Not knowing when the next meal would be, he meant to eat enough now to last some time.

"How now, my friend!" said a voice out of the wild rice. Iktomi jumped. He almost choked on his soup. He peered through the long reeds from where he sat with his long horn spoon in mid-air.

"Hello, my friend!" said the voice again, this time close at his side. Iktomi turned and there stood a dripping muskrat who had just come out of the lake.

"Oh, it is my friend who startled me. I wondered if among the wild rice some spirit voice was talking. Hello, my friend!" said Iktomi. The muskrat stood smiling. On his lips hung a ready "Yes, my friend," when Iktomi would ask, "My friend, will you sit down beside me and share my food?"

That was the custom of the plains people. Yet Iktomi sat silent. He hummed an old dance-song and beat gently on the edge of the pot with his buffalo-horn spoon. The muskrat began to feel awkward before such lack of hospitality and wished he had stayed underwater.

After many heart throbs Iktomi stopped drumming with his horn ladle, and looking upward into the muskrat's face he said, "My friend, let us run a race to see who shall win this pot of fish. If I win, I shall not need to share it with you. If you win, you shall have half of it." Springing to his feet, Iktomi began at once to tighten the belt about his waist.

"My friend Ikto, I cannot run a race with you! I am not a swift runner, and you are nimble as a deer. We shall not run any race together," answered the hungry muskrat.

For a moment Iktomi stood with a hand on his long protruding chin. His eyes were fixed on something in the air. The muskrat looked out of the corners of his eyes without moving his head. He watched the wily Iktomi concocting a plot.

"Yes, yes," said Iktomi, suddenly turning his gaze on the unwelcome visitor, "I shall carry a large stone on my back. That will slacken my usual speed, and the race will be a fair one." Saying this he laid a firm hand upon the muskrat's shoulder and started off along the edge of the lake.

When they reached the opposite side, Iktomi poked about in search of a heavy stone. He found one half-buried in the shallow water. Pulling it out on dry land, he wrapped it in his blanket.

"Now, my friend, you shall run on the left side of the lake, I on the other. The race is for the boiled fish in yonder kettle!" said Iktomi.

The muskrat helped to lift the heavy stone upon Iktomi's back. Then they parted. Each took a narrow path through the tall reeds fringing the shore. Iktomi found his load a heavy one. Perspiration hung like beads on his brow. His chest heaved hard and fast. He looked across the lake to see how far the muskrat had gone, but nowhere did he see any sign of him.

"Well, he is running low under the wild rice!" said he to himself. Yet as he scanned the tall grasses on the lake shore, he saw not one stir as if to make way for the runner. "Ah, has he gone so fast ahead that the disturbed grasses in his trail have quieted again?" exclaimed Iktomi. With that thought he quickly dropped the heavy stone. "No more of this!" he said, patting his chest with both hands.

Off with a springing bound, he ran swiftly toward the goal. Tufts of reeds and grass fell flat under his feet. Hardly had they raised their heads when Iktomi was many paces gone. Soon he reached the heap of cold ashes. Iktomi halted stiff as if he had struck an invisible cliff. His black eyes showed a ring of white about them as he stared at the empty ground. There was no pot of boiled fish! There was no muskrat in sight!

"Oh, if only I had shared my food like a real Dakota, I would not have lost it all! Why did I not know the muskrat would run through the water? He swims faster than I could ever run! That is what he has done. He has laughed at me for carrying a weight on my back while he shot hither like an arrow!" Crying thus to himself, Iktomi stepped to the water's brink. He stooped forward with a hand on each bent knee and peeped far into the deep water.

"There!" he exclaimed, "I see you, my friend, sitting with your ankles wrapped around my little pot of fish! My friend, I am hungry. Give me a bone!"

"Ha! Ha! Ha!" laughed the water-man, the muskrat. The sound did not rise up out of the lake, for it came down from overhead. With his hands still on his knees, Iktomi turned his face upward into the great willow tree. Opening wide his mouth he begged, "My friend, my friend, give me a bone to gnaw!"

"Ha! Ha!" laughed the muskrat, and leaning over the limb he sat upon, he let fall a small sharp bone that dropped right into Iktomi's throat. Iktomi almost choked before he could get it out. In the tree the muskrat sat laughing loud. "Next time, say to a visiting friend, ‘Be seated beside me, my friend. Please share my food.' Then perhaps you won't lose it all."

Iktomi's Blanket

Alone within his tepee sat Iktomi. The sun was but a hand's breadth from the western edge of land.

"Those, bad, bad gray wolves! They ate up all my nice fat ducks!" muttered he, rocking his body to and fro. He was cuddling the evil memory he bore those hungry wolves. At last, he ceased to sway his body backward and forward, but sat still and stiff as a stone image. "I'll go to Inyan, the great-grandfather, and pray for food!" he exclaimed.

At once he hurried forth from his tepee and, with his blanket over one shoulder, drew nigh to a huge rock on a hillside. With half-crouching, half-running strides, he fell upon Inyan with outspread hands.

"Grandfather! Pity me. I am hungry. I am starving. Give me food. Great-grand-father, give me meat to eat!" he cried. All the while he stroked and caressed the face of the great stone god.

The all-powerful Great Spirit, who makes the trees and grass, can hear the voice of those who pray in many varied ways. The hearing of Inyan, the large hard stone, was the one most sought after. He was the great-grandfather, for he had sat upon the hillside many, many seasons. He had seen the prairie put on a snow-white blanket and then change it for a bright green robe more than a thousand times. Still unaffected by the myriad moons he rested on the everlasting hill, listening to the prayers of Indian warriors. Before the finding of the magic arrow he had sat there.

Now, as Iktomi prayed and wept before the great-grandfather, the sky in the west was red like a glowing face. The sunset poured a soft mellow light on the huge gray stone and the solitary figure beside it. It was the smile of the Great Spirit upon the grandfather and the wayward child.

The prayer was heard. Iktomi knew it. "Now, Grandfather, accept my offering—it is all I have," said Iktomi as he spread his half-worn blanket upon Inyan's cold shoulders. Then Iktomi, happy with the smile of the sunset sky, followed a foot-path leading toward a thicketed ravine. He had not gone many paces into the shrubbery when before him lay a freshly killed deer!

"This is the answer from the red western sky!" cried Iktomi, with hands uplifted. Slipping a long thin blade from his belt, he cut large chunks of choice meat. Sharpening some willow sticks, he planted them around a woodpile he had ready to kindle. On these stakes he meant to roast the venison.

While he was briskly rubbing two long sticks to start a fire, the sun in the west fell out of the sky below the edge of land. Twilight was over all. Iktomi felt the cold night air on his bare neck and shoulders. "Ough!" he shivered as he wiped his knife on the grass. Tucking it in a beaded case hanging from his belt, Iktomi stood erect, looking about.

He shivered again. "Ough! Ah! I am cold. I wish I had my blanket!" whispered he, hovering over the pile of dry sticks and the sharp stakes round about it. Suddenly he paused and dropped his hands at his sides.

"The old great-grandfather does not feel the cold as I do. He does not need my old blanket as I do. I wish I had not given it to him. Oh! I think I'll run up there and take it back!" said he, pointing his long chin toward the large gray stone.

Iktomi had no need of his blanket in the warm sunshine, and it had been very easy to part with a thing that he could not miss. But the chilly night wind quite froze his ardent thank offering. Thus, running up the hillside, his teeth chattering all the way, he drew near to Inyan, the sacred symbol. Seizing one corner of the half-worn blanket, Iktomi pulled it off with a jerk.

"Give my blanket back, old Grandfather! You do not need it. I do!" This was very wrong, yet Iktomi did it, for his wit was not wisdom.

Drawing the blanket tight over his shoulders, he descended the hill with hurrying feet. He was soon upon the edge of the ravine. A young moon, like a bright bent bow, climbed up from the southwest horizon a little way into the sky. In this pale light Iktomi stood motionless as a ghost amid the thicket. His woodpile was not yet kindled. His pointed stakes were still bare as he had left them. But where was the deer—the venison he had felt warm in his hands a moment ago? It was gone. Only the dry rib bones lay on the ground like giant fingers. Iktomi was troubled.

At length, stooping over the white dried bones, he took hold of one and shook it. The bones rattled together at his touch. Iktomi let go his hold. He sprang back amazed. And though he wore a blanket his teeth chattered more than ever. Then, instead of being grieved that he had taken back his blanket, he cried aloud, "Hin-hin-hin! If only I had eaten the venison before going for my blanket!"

Those tears no longer moved the hand of the Generous Giver. They were selfish tears. The Great Spirit does not heed them ever.

Continue reading...

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

Zitkála-Šá, The Red Bird (1876 - 1938), was a Yankton Sioux Composer, Writer, Educator and Indigenous Rights Activist.

https://palianshow.wordpress.com/2021/11/26/zitkala-sa-red-bird/

Zitkála-Šá was born on Feb 22, 1876, on the Yankton Indian Reservation in South Dakota.

Mother: Ellen Simmons, whose Dakota name was Thaté Iyóhiwiŋ (Every Wind or Reaches for the Wind).

In 1884, when Zitkala-Ša was eight, missionaries came to the reservation. Zitkála-Šá attended the school for three years until 1887. She later wrote about this period in her work, The School Days of an Indian Girl.

She described the deep misery of having her heritage stripped away when she was forced to pray as a Quaker and to cut her traditionally long hair. By contrast, she took joy in learning to read and write, and to play the violin.

In 1891, wanting more education, Zitkála-Šá decided at age fifteen to return to school.

In June 1895, when Zitkála-Šá was awarded her diploma, she gave a speech on the inequality of women’s rights, which was praised highly by the local newspaper.

(3) In Utah, Zitkála-Šá met William F. Hanson, a composer and music professor at Brigham Young University. Together they composed The Sun Dance Opera. Zitkála-Šá wrote the songs and libretto based on Sioux ritual.

She was co-founder of the National Council of American Indians in 1926.

From Washington, Zitkála-Šá began lecturing nationwide on behalf of SAI to promote greater awareness of the cultural and tribal identity of Native Americans. In 1924 the Indian Citizenship Act was passed, granting US citizenship rights to most indigenous peoples who did not already have it.

Zitkála-Šá died on January 26, 1938, in Washington, D.C., at the age of sixty-one.

She is buried as Gertrude Simmons Bonnin.

#zitkalasa #ZitkálaŠá #YanktonSioux #Lakota #nativeamericanheritage #nativefeminist #GertrudeSimmonsBonnin #nativeheritageday #nativeherstory #redbird #zitkalasa #ZitkálaŠá #SimmonsBonnin #YanktonDakota #femalewriter #femaleauthor #femalecomposer #politicalactivist #culturalidentity #Dakotaculture #NativeAmericanstories #NativeAmericanActivist

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

“On February 22, 1876, Thaté Iyóhiwiŋ, a Yankton Dakota woman living on the Yankton Indiana Reservation in South Dakota, and her European American mate, Felker Simmons, brought their daughter, Zitkála-Šá, into the world. Simmons would abandon mother and child, yet Zitkála-Šá describes the first 8 years of her life on the reservation as happy and safe. All that changed in 1884 when missionaries came to “save” the children.

Even though White's Indiana Manual Labor Institute was a Quaker project, it still forced the children who attended to adapt to the Quaker way of doing things, including taking new names. Zitkála-Šá was renamed Gertrude Simmons. In her biographies, Zitkála-Šá describes deep conflict between her native identity and the dominant white culture, the sorrow of being separated from her mother, and her joy in learning to read, write, and play the violin.

Zitkála-Šá returned to the reservation in 1887, but after 3 years she decided she wanted to further her education and returned to the Institute again. She taught music while attending school from 1891 to 1895, when she earned her first diploma. Her speech at graduation tackled the issue of women’s inequality and was praised in local newspapers. She had a gift of public speaking and music, and put both to good use during her life.

In 1895 Zitkála-Šá earned a scholarship to attend Earlham College in Richmond, Indiana. While in college she gave public speeches and even translated Native American legends into Latin and English for children. In 1887, mere weeks from graduation, her health took a turn for the worse; her scholarship did not cover all expenses, so she had to drop out.

After college Zitkála-Šá used her musical talents to make a living. From 1897-1899, she played violin with the New England Conservatory of Music in Boston. She then took a job teaching music at the Carlisle Indian Industrial School in Pennsylvania, where she also hosted debates on the issue of Native American treatment. The school used her to recruit students and impress the world, but her speaking out against their rigid indoctrination of native children into white culture resulted in her dismissal in 1901.

Concerned about her mother’s health, Zitkála-Šá returned to the reservation. While there she began to collect the stories of her people and translate them into English. She found a publisher in Ginn and Company, and they put out her collection of these stories as Old Indian Legends in 1901. Like most authors, she took another job at the Bureau of Indian Affairs as her principal support. It was at this job in 1902 that she met and married Captain Raymond Bonnin, a mixed-race Nakota man.

The couple moved to work on the Uintah-Ouray Reservation in Utah for the next 14 years. They had one son, named Ohiya. Zitkála-Šá met and began to collaborate with William F. Hanson, a composer at Brigham Young University. Together they created The Sun Dance, the first opera co-written by a Native American. The opera used the backdrop of the Ute Sun Dance to explore Ute and Yankton Dakota cultures. It premiered in 1913 and was originally performed by Ute actors and singers. Choosing such a topic for the opera would have been a way to strike back at forced enculturation, because the ritual itself had been outlawed by the Federal Government in 1883 and remained so until 1933. Much later, in 1938, The Sun Dance came to The Broadway Theatre in New York City.

From 1902-1916, Zitkála-Šá published several articles about her life and native legends for English readers. Her works appeared in Atlantic Monthly and Harper’s Monthly, magazines with primarily a white readership. Her essays also appeared in American Indian Magazine. While these pieces were often autobiographical, they were still political and social commentary that showed her increased frustration with the Bureau of Indian Affairs, which fired the couple in 1916.

In 1916, the couple moved to Washington D.C., where Zitkála-Šá served as the secretary of the Society of the American Indian. In 1926, she founded the National Council of American Indians, an organization that worked to improve the treatment and lives of Native Americans. By 1928, she was an advisor to the Meriam Commission, which would lead to several improvements in how the Federal Government treated native peoples.

Zitkála-Šá continued writing, and her books and essays became more political in such works as American Indian Stories (1921) and “Oklahoma’s Poor Rich Indians,” published in 1923 by the Indian Rights Association. She spoke out for Indian’s rights and women’s rights up until her death in 1938 at the age of 61"

📷: Gertrude Kasebier's photos of Zitkala-Ša, AKA Red Bird, from BUFFALO BILL'S WILD WEST WARRIORS. You can read about her in the book INDIGENOUS INTELLECTUALS by Kiara M. Vigil.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Gertrude Käsebier - Zitkála-Šá (Red Bird), 1897.

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

📚 Leseempfehlung für indianische Weltliteratur! 🌍✨

Tauche ein in die reichhaltige und tiefgründige Welt der indianischen (Native American) Literatur, die durch ihre spirituelle Tiefe, kulturellen Einblicke und die Verbindung zur Natur weltweit Anerkennung gefunden hat. Diese Werke bieten einzigartige Perspektiven auf Identität, Geschichte und die Erfahrungen der indigenen Völker.

1. Sherman Alexie – „Der absolute Wahrheitsgehalt“ (The Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian)

📖 „Der absolute Wahrheitsgehalt“ erzählt die Geschichte von Arnold Spirit, einem jungen indianischen Jungen aus dem Rezervat, der in die Stadt geht, um eine bessere Zukunft zu suchen. Es geht um Identität, Hoffnung und die Herausforderungen im Leben eines jungen Indianers.

📖 „Indian Killer“ – Ein weiteres Werk, das sich mit den Gesellschaftsfragen, Gewalt und den inneren Konflikten eines modernen Indianers auseinandersetzt.

Warum du ihn lesen solltest:

Sherman Alexie ist bekannt für seinen Witz, seine authentischen Geschichten und die warmen sowie kritischen Einblicke in die Herausforderungen von Native Americans in der heutigen Gesellschaft.

2. N. Scott Momaday – „Haus aus Morgen“ (House Made of Dawn)

📖 „Haus aus Morgen“ ist ein Pulitzer-Preis-gekrönter Roman, der sich mit dem Leben eines jungen Mannes aus der Navajo Nation befasst. Er kämpft mit den Traumata des Krieges und der Kulturkonflikte, die das Leben der Navajo-Gemeinschaft prägen.

📖 „The Way to Rainy Mountain“ – Ein weiteres Werk, das sich mit der Mythologie, Geschichte und spirituellen Bedeutung der Navajo auseinandersetzt.

Warum du ihn lesen solltest:

Momaday ist ein Meister des poetischen Erzählens und bekannt für seine dichten, kulturell und spirituell aufgeladenen Werke, die tief in die indianische Erfahrung und Mythologie eintauchen.

3. Leslie Marmon Silko – „Ceremony“

📖 „Ceremony“ erzählt die Geschichte von Tayo, einem jungen Zuni-Mann, der nach dem Zweiten Weltkrieg zurückkehrt und sich mit den Traumata des Krieges und den Herausforderungen einer veränderten Welt auseinandersetzt. Es geht um Selbstfindung, Heilung und die Verbindung zu traditionellen Ritualen.

📖 „Almanac of the Dead“ – Ein weiteres Werk, das sich mit der Kolonialisierung und den sozialen Kämpfen der indigenen Völker beschäftigt.

Warum du sie lesen solltest:

Silko ist eine der bedeutendsten indigenen Schriftstellerinnen, deren Werke in der postkolonialen Literatur einen besonderen Platz einnehmen. Sie behandelt Themen wie Heilung, Wiedergeburt und die Kraft der Erzählung.

4. James Welch – „Fools Crow“

📖 „Fools Crow“ ist ein historischer Roman, der die Geschichte eines Blackfeet-Indianers erzählt, der in den letzten Jahren des 19. Jahrhunderts lebt und sich mit den Veränderungen im Leben der indigenen Völker durch die westliche Expansion auseinandersetzt.

📖 „Winter in the Blood“ – Ein weiteres Werk, das die inneren Konflikte und die Identitätssuche eines jungen Indianers in der modernen Welt behandelt.

Warum du ihn lesen solltest:

Welch ist bekannt für seine epischen und historisch aufgeladenen Erzählungen, die den Kampf der Ureinwohner gegen die Zerstörung ihrer Kulturen und Traditionen darstellen.

5. Louise Erdrich – „Die letzte Reportage“ (Love Medicine)

📖 „Love Medicine“ ist ein episches Werk, das die Geschichte mehrerer Generationen einer Chippewa-Familie im Nordwesten der USA erzählt. Es geht um Liebe, Verlust und die Veränderungen, die die indigene Gemeinschaft im Laufe der Jahre durchlebt.

📖 „The Round House“ – Ein weiteres Werk, das sich mit den Themen Recht und Gewalt in einer indigenen Gemeinschaft auseinandersetzt.

Warum du sie lesen solltest:

Erdrich ist bekannt für ihre fesselnde Darstellung von indigenen Familien und ihrer spirituellen und emotionalen Reise durch die moderne Welt. Ihre Werke sind eine Mischung aus Tradition und modernen Herausforderungen.

6. Zitkála-Šá – „Im Land der Roten Sonne“ (Old Indian Days)

📖 „Im Land der Roten Sonne“ ist eine Sammlung von Erinnerungen und Erfahrungen einer Sioux-Frau, die mit den Herausforderungen der indianischen Kultur und der Kolonialisierung im späten 19. Jahrhundert konfrontiert wird.

📖 „Die fliegende Taube“ (The Flying Bird) – Ein weiteres Werk, das sich mit den Konflikten innerhalb der Sioux-Gemeinschaft und der Zerstörung ihrer Traditionen beschäftigt.

Warum du sie lesen solltest:

Zitkála-Šá ist eine der frühesten Stimmen in der indigenen Literatur Amerikas. Ihre Werke bieten wertvolle Einblicke in die Kämpfe und den Widerstand der Sioux gegen die Kolonialisierung.

Warum du diese Werke lesen solltest:

Die indianische Literatur ist nicht nur eine Sammlung von Geschichten, sondern eine tiefgehende Reflexion über Identität, Kultur, Überleben und den Widerstand gegen die Kolonialisierung. Diese Werke bieten einzigartige Perspektiven und tiefgehende emotionale Einsichten in das Leben der indigenen Völker.

📖 Lass dich von der faszinierenden Welt der indianischen Literatur verzaubern und entdecke die Werke dieser außergewöhnlichen Schriftsteller!

©️®️CWG, 26.02.2025

#IndianischeLiteratur #Weltliteratur #LesenIstLeben #Bücherliebe #ShermanAlexie #NScottMomaday #LeslieMarmonSilko #JamesWelch #LouiseErdrich #ZitkálaŠá #Literaturempfehlung #Bücherwelt #cwg64d #cwghighsensitive #oculiauris

0 notes

Text

November is National Native American Heritage Month. So, it’s the perfect time for the following piece by guest essayist Maggie Speck-Kern. Her essay examines the “American experience,” specifically the drastically different lives that native American activist Zitkála-Ša (pronounced Zit-KAH-la-shah) and author Laura Ingalls Wilder experienced during the pioneer era.

Speck-Kern also points out the many important ways their lives were more similar than different despite the vast disparity between their respective cultures, a realization we would do well to remember in our own lives – especially these days. Check out this insightful, and more-relevant-than-ever piece here:

0 notes

Text

0 notes

Text

For Zitkála-Šá

Raven Chacon (Diné)

lithograph prints

19 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Iris of Life

Like tiny drops of crystal rain, In every life the moments fall, To wear away with silent beat, The shell of selfishness o’er all.

And every act, not one too small, That leaps from out the heart’s pure glow, Like ray of gold sends forth a light, While moments into seasons flow.

Athwart the dome, Eternity, To Iris grown resplendent, fly Bright gleams from every noble deed, Till colors with each other vie.

’Tis glimpses of this grand rainbow, Where moments with good deeds unite, That gladden many weary hearts, Inspiring them to seek more Light.

Zitkála-Šá (22 Février 1876-26 Janvier 1938)

Zitkála-Šá, Sioux writer, musician and political activist by Gertrude Käsebier (1898)

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

ZITKÁLA-ŠÁ // WRITER

“She was a Yankton Dakota writer, editor, translator, musician, educator, and political activist. She wrote several works chronicling her struggles with cultural identity, and the pull between the majority culture in which she was educated, and the Dakota culture into which she was born and raised. Her later books were among the first works to bring traditional Native American stories to a widespread white English-speaking readership. She has been noted as one of the most influential Native American activists of the 20th century.”

1 note

·

View note

Text

Raven Chacon, For Cheryl L'Hirondelle, from the series For Zitkála Šá, 2019. Lithograph on paper, sheet and image: 11 in. × 8 1⁄2 in. Courtesy of the artist.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

#Zitkála-Šá#Gertrude Simmons Bonnin#Zitkala-Sa#Yankton Dakota#indigenous#activist#political activist#women's right activist#writer#educator#musician#gertrude#native#zitkala sa#suffragette#squaw

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

Treasures came in due time to those ready to receive them.

#american indian stories#a dream of her grandfather#zitkala-sa#Zitkála-Šá#indigenous redathon#indigineous people#book quotes#quotes#treasures

4 notes

·

View notes