#writing style but with less effort put in to connect the scenes through a narrator guiding the reader.

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Horrified to say I may just try an experimental writing style for me and see how it fucking goes

But I really hate rewriting in a different way later ;-;

But I also just. Really want these scenes written down, physically existing instead of just in my brain. However they come written out, at least they'd BE WRITTEN

#rant#writing#;-; my brain is torn between 3 writing style choices right now#1 my usual one. which is mostly like scenes from a movie but the narrator character close perspective pov#will sort of guide the story in what is getting focus. so it holds your hand a bit#by communicating for example 'this story is about X that happened/my connection to my loved one/how i met them/how i changed into X'#each chapter. which helps each segment of story feel like a complete mini-self contained story. its satisfying#because u get an intro journey and conclusion which are connectsd each chapter.#the downside? i have to focus on a particular arc singularly in one chapter#and i cant jump around to multiple. i also cant pick as broad a scene choice. i have to omit more#in attempt to remain more focused on only what relates to that chapters 'main thread' its telling#and i dont want that cohesion this time tbh. i want novel length cohesion but#i want individual scenes to be more disjointed separate moments you the Reader determine how are connected#i dont want to spoonfeed the reader WHY theyre connected. i think disjointed will first help#me write SHORTER scenes of show instead of tell. and second it will allow#yhe story to read as one bigger whole in a wider cast way which i want.#2 i like the idea of a Telling a Fairytale style. because i remember the whole story in my head this way lol. byt downside? it reads like a#history book or myth. and i know ppl generally dont enjoy modern fiction written this way.#3 the previously mentioned disjointed way. individual scenes and the emotions in them. then skip to the next scene. like my usual#writing style but with less effort put in to connect the scenes through a narrator guiding the reader.#with much less content of the narrator explaining the point of the scenes. again i think this stylw#would let me first write MORE scenes since scenes will be shorter word counts#and second i think the curtness and separation of individual scenes will help me focus on a larger cast#qhereas with my usual writing style i have to mainly stay in the pov of only 1-3 characters#as the story is more heavily guided/leaned into one characters pov

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

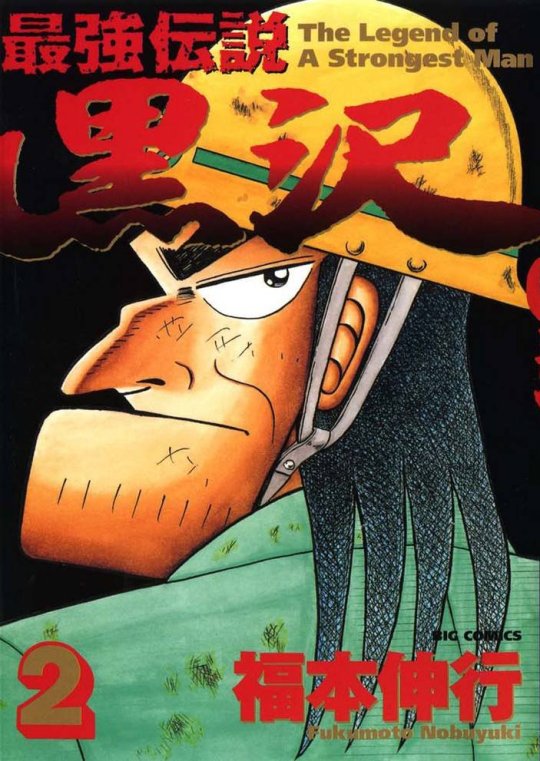

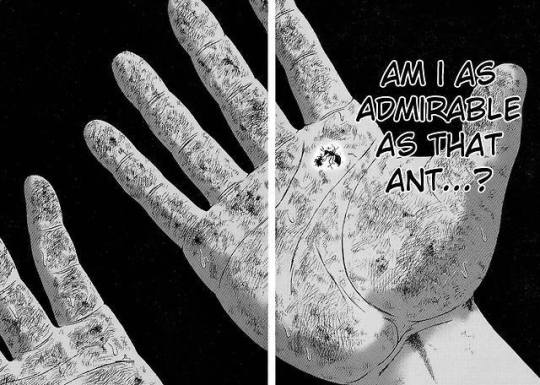

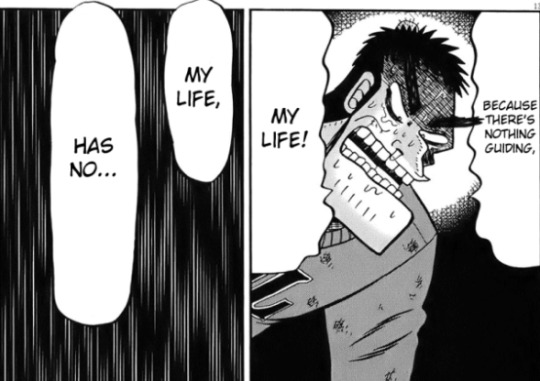

Thoughts on Saikyou Densetsu Kurosawa

FUKUMOTO Nobuyuki, 11 volumes, published from 2003 to 2006 in Big Comic Original (Seinen)

Saikyou Densetsu Kurosawa (Legend of the strongest man Kurosawa) follows the story of 44 years old construction worker Kurosawa as he realizes he spent most of his life without any meaningful connections with anyone nor any special achievements. He decides to change his life so that he can become proud of his own accomplishments and efforts, and earn respect and appreciation from the people around him.

(spoiler warning)

So I’m currently binging Fukumoto manga, after having them on my “plan to read” list for several years…I started with Kaiji, but initially the first manga of his that caught my interest was Kurosawa. The themes of it are right up my alley, and I like main characters that are not teenagers or young adults.

Kurosawa has a sequel, Shin Kurosawa: Saikyou Densetsu, which is a direct continuation. I’ll mostly be focusing on the first part here.

The art is typical Fukumoto style. Odd at first, definitely not the prettiest nor the most impressive out there, but it does the job and I really grew to like it. He doesn’t hesitate to give exaggerated features to his characters, and I actually find the deliberate ugliness of the character designs refreshing. It certainly fits the story of Kurosawa, makes the characters very expressive and works well with the often comedic tone.

Although the art looks simple, Fukumoto can deliver very intense pages when he needs to.

His forte is in his use of narration combined with the picture, rather than in the drawings alone. He is a master at using a narrator’s comments or the character’s thoughts to raise tension and make the manga flow better.

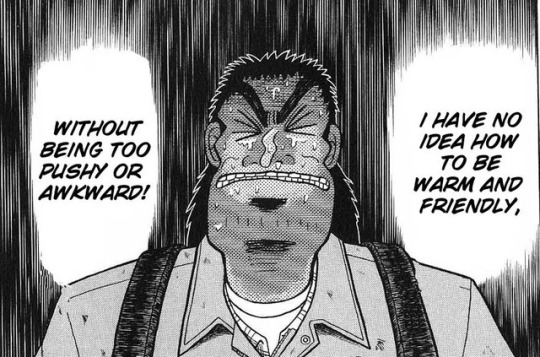

Kurosawa is definitely written with a lot of heart. Both the manga itself and the titular character, feel very genuine. Kurosawa is very flawed and very human. He is rough but powerful, his desires are simple, and he is straightforward in his reactions, to the point that his impulsive nature and lack of social restraints put him in trouble, especially when it comes to women...

There are a few instances however where he comes close to harassing women, which is played for laugh, which I disliked. Those scenes made me less sympathetic towards him as he actually deserved the repercussions of his actions here.

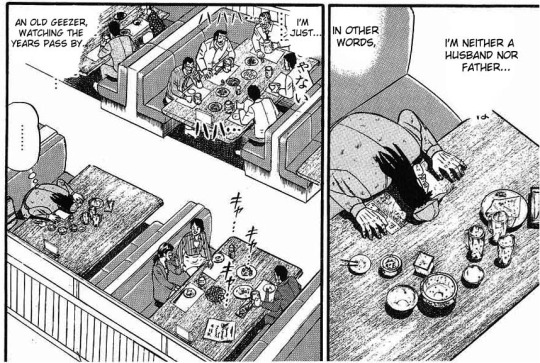

But besides those chapters, Kurosawa is overall a likeable character, easy to sympathize with and to root for as we see him at a low point of his life.

He is clumsy in his interactions with his coworkers, which, coupled with his hot-temper, often leads to misunderstandings and prevents him from getting closer to them despite his best efforts. I actually found Kurosawa’s failed attempts at achieving popularity reminiscent of Watamote. The beginning of both series, in which a pathetic main character fails repetitively at gaining the appreciation of their peers through outlandish strategies, elicits the same mixture of pity, second-hand embarrassment, and amusement.

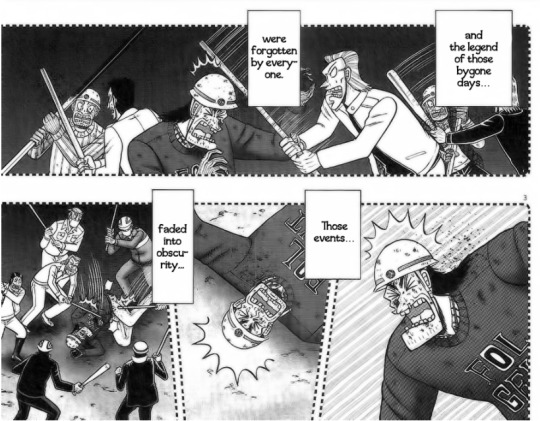

Kurosawa also gets into a fair number of fights. While those fight-focused chapters were not bad, I was personally less into them.

Drawing literal fist-fights in not what Fukumoto’s best at. His character’s postures are somewhat stiff, which he compensates for with heavy use of speed-lines. It is okay-ish, but I want read a fight scene, there’s plenty of fighting manga out there that can do a better job.

I like Fukumoto more when he writes more psychological battles, like in his gambling mangas. Of course, psychological elements and strategies where not totally absent from the fights, but it was nowhere as much as in his gambling manga. Sometimes I think Kurosawa was a bit too lucky in the fights, as he is not a very athletic person nor someone with a lot of experience in fighting. It did not feel very convincing to me.

Besides, it is through these battles that Kurosawa gathers allies, a reputation and respect. But most of his opponents are teenagers, even middle-schoolers ! Granted they are very scary teenagers, but I still fail to see how a 44 years old man throwing hands with teenagers is such a praise worthy thing...

I think I prefer to see Kurosawa fight and struggle to improve his life in a less literal way that actual physical fighting.

I haven’t read that many of Fukumoto’s works yet, but I feel like an important theme in them is perseverance/resilience. He puts his characters through a lot, but they tend to have some form of resistance that shines through as admirable. Kurosawa’s will to fight and to push back against adversity is sometimes the only thing he has left, and it is extremely important.

However, that is not an innate ability that comes to him easily -at times Kurosawa hides, flees, cowers. He hesitates, and he needs to think things through before he actually decides to fight.

Fukumoto: You know how protagonists in shonen manga do things like jump in to stop their classmate from being bullied without thinking about how they might get beaten up themselves? I always felt that wasn’t real. So with Kurosawa, I wanted to make a manga that shows hesitation, and how it actually isn’t so easy to defend people like that.

(Excerpt from this interview)

I like this kind of manga where characters reflect about what is the right decision to take and on how they should be living their life. And how the reader has access to their inner turmoil and thoughts.

His strength is often born from sheer desperation and desire to survive. It is when he is cornered that he can manage to act and fight even when the odds are against him. He has to make do with the very few tools and options he has, which leads him to elaborate unconventional tactics to win over his opponents.

Having cornered underdogs characters winning over more powerful, but less desperate, opponents seems like a running theme in Fukumoto’s manga (cf. the made-up E-card Game from Kaiji, in which The Slave is the only card that can win against The Emperor, precisely because it is so low that it has nothing to lose anymore).

In a way, one could argue Kurosawa follows a formula reminiscent of classic shounen manga: a character who is below average at first rises to a heroic status through willpower, effort and after fighting a string of opponents. However, there are major differences that set Kurosawa apart, besides the older characters and more adult setting (Kurosawa’s worries are grounded in reality: growing old alone, financial problems...) Kurosawa does not provide escapism and dreams. The story begins with Kurosawa as a single old man, and ends with him an even older still single man. He does not become an amazing fighter through power boost and magic training like a shounen character might.

He does want to dream big, but all things considered, his achievements are fairly modest. He is not saving the world or becoming hokage. At most he is just helping some other marginalized people from his neighborhood.

Even if he puts his life on the line to fight, what he accomplished will fade into oblivion at some point.

But, even so, his efforts and struggle are still admirable.

Besides, Kurosawa is not about friendship, at least not the kind of friendship you find in shounen manga.

In Fukumoto’s manga, people may stick together for survival, they can share intense emotions when put through the same ordeals, but it’ll rarely turn into true companionship. Kurosawa is alone from the start, and while he does connect with other people throughout the story, in the sequel those relationships are left behind as he leaves on his own to start a new life.

Fukumoto: My protagonists, on the other hand, are always alone – not only do they not have followers, they don’t even have friends. (laugh) [...] I can’t do manga where the characters readily make friends that they risk their lives for. I started out by drawing short human drama pieces, but even then – partially because I wasn’t doing long-term series, but – they weren’t generally stories about friends.

I was kind of expecting Asai, one of Kurosawa’s coworker, to have a bigger role, but that didn’t happen. (I liked the part where he tried to comfort Kurosawa after he got humiliated so I was hoping for more!)

The story isn’t very cohesive or straighforward, it just follows Kurosawa’s life, who wants to change but lacks a clearly defined goal or road to follow. There isn’t one big coherent plot, instead the story goes in different directions, shifting from one genre to another from chapter to chapter. Kurosawa even admits it himself !

The quality of the chapters and different arcs is in my opinion rather uneven.

There are some really powerful scenes, notably the very end of the manga which is very touching. Kurosawa successfully leads a group of homeless men to defend themselves against some delinquents who were threatening them, but as a result of his injuries, he is implied to die. (The sequel manga reveals he actually just goes into coma for 8 years). It is bittersweet ending as he finally achieved something and is surrounded by human warmth.

Shin Kurosawa, the sequel, is similar to the first part, though slightly more light-hearted and focused on humor (even though Kurosawa’s situation technically worsens!). It seems to be less liked than the first part for those same reasons, but I personally enjoy Fukumoto’s humor and his more slice of life-y mangas. It has many genuinely funny moments. Once in a while there are still some chapters that feel deeper/more thought provoking, as Fukumoto likes to reflect about society, life, and humanity in his stories.

For anyone looking for other manga with similar themes, I can recommend Furuya Minoru’s excellent Wanitokagegisu . Both feature very lonely adult men who wish to turn their life around, and oscillate between humor and psychological drama.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

the things I’ve read in 2020 and some thoughts...

hey blacklist this now because it’s gonna get long from here. I spent NYE home alone and reading and it has really set the tone for this year. Fortunately, I’ve been reading way more for the first time in...I literally don’t even know? Maybe forever? Which is really dope! Books are fucking fantastic and I hope this trend continues for the rest of the year. So I’m gonna use this post (and continue to add to it as I finish books) to talk about the things I’ve read. It could be annoying. I could give up on it really soon. People might not read this at all. It’s okay! It’s my blog I’ll use it how I want and I want to talk about books I otherwise don’t really have a place to talk about them.

The Shape of Water - Guillermo Del Toro & Daniel Kraus

If you know me irl you’ll know that I love this movie. Like, it’s probably my favorite movie as an adult. I love watching a movie and then going back and reading the book to compare and vice versa, but knowing that the book came out after the movie did discourage me at first, making me think it was nothing more than a cash grab. Though I was talking to (my boss) who also loves this movie and is a huge bibliophile and she highly recommended the book, so I figured I’d give it a stab.

The writing style is beautiful and enticing and overall I was impressed with the quality of it. It’s fast paced and switches perspective between characters frequently, though remains easy to follow. The book focuses a little less on Elisa and more on the other characters and stories around her, including, surprisingly, Elaine Strickland, who despite never wondering much about during the movie, I enjoyed being included in the book. There’s a deeper exploration into pretty much everyone’s backstories, and more prominent character development. It’s excellent as a standalone piece, and supplementary to readers who have seen the movie. There’s also some alternative takes on certain scenes, which I don’t necessarily like better or worse than the choices made in the movie, but it makes for an interesting read.

The book explores themes of alienation and being othered, with a main cast that breaks the stereotype of straight white fully-abled male. Elisa is a mute woman, Zelda, a black woman, and Giles a gay man. With the political climate of the 1950′s, all of them are outsiders and all of them find solidarity in each other, despite their unique struggles, and also with the creature.

The only thing I didn’t quite like was the portrayal of the creature. I think greater efforts were put into making him more godlike and otherworldly, but also, simultaneously, he comes off as much more like a wild animal in the book, and the latter came off as strange to me, and not in the way I like it. Overall, even if the movie didn’t exist and I only read this, I’d still think it was a really good story.

To Be Taught, If Fortunate - Becky Chambers

If I depended on the synopsis on the back of the book to decide whether or not I wanted to read this, I don’t know if I would have bothered. To be honest, I only wanted to read this because Becky Chambers is my current favorite author and all other of her works I’ve read I’ve absolutely adored, so naturally, I wanted to give this one a chance, even if the concept wasn’t as riveting as I would have hoped.

She didn’t disappoint.

Whereas her other books take place in a vast space civilization where humanity is integrated with aliens and there’s technology beyond our dreams, this book took place in a different creative universe, a little more closer to our timeline. The book is about space exploration for the sake of learning and taking care to be as least intrusive on the explored worlds as possible. It’s a nice break from what I usually see in sci fi, with colonization and owning space and wanting to use knowledge in order to hurt others. It follows a research crew of four, sent to research four planets in a far solar system. There’s a lag in travel time, since FTL travel had not been discovered yet, so a common device is communication with Earth is off by years. Eventually, the crew realizes they have lost contact with Earth and Earth had likely suffered some sort of devastation. It wonders if Earth has forgotten them or if it’s even worth it to return since they might be the last astronauts of their time.

The worlds they visit and research are unique and vivid and fill me with wonder. They’re realistic to the point where I found myself questioning if the book was prophetic. Chambers makes effort to incorporate science into her novels, but in a way that does not estrange a reader like me who only has a basic knowledge in science. It’s one of the things I find most attractive about her work, because it has this added realism and this feeling of “wow, this really could happen” and yet remains easy to follow.

I found the crew to be likeable and diverse. Three of them are in a relationship with each other, and while polyamory isn’t usually an interest of mine, it’s in the background as well as it’s never used as a point to cause drama. It’s a healthy functional relationship. Also, one of the crew is a trans man and another is asexual, both details that exist within a single line, but yet important to be included to flesh out the characters.

What I didn’t like was the almost rush to the end of the book. It’s a short book, roughly 100 pages, but it seems to me as if it reaches it’s climax and then the book just ends and it kind of feels like it’s still in the middle of things. I’ve had time to think about it, though, and I’ve considered that maybe anything else written would have been redundant or just filler and therefore not needed. So in that case, that’s fair. It still felt a little abrupt to me, but that’s what fic is for.

Overall, if you haven’t read anything by Becky Chambers you need to change that immediately. Please don’t leave me alone and fanning over this incredible author!!

All Systems Red - Martha Wells

This was another short one, and in fact, I read it entirely in one sitting. The concept of the book was really intriguing, and actually I selected it because I liked the opening line so much. I have a lot of feelings about AI and robots, so this was a naturally alluring story to me. Mixed with the fact that the beefed out security robot, who calls themselves “Murderbot”, was absolutely obsessed with soap opera tv just absolutely gets me!

The story is told through Murderbot’s perspective, who is assigned to guard a research team. They had recently hacked their government module, which now allows them full autonomy and no longer having to obey orders from their assigned humans. It’s interesting to see Murderbot actively choose to help the humans. Also, needing to maintain an illusion that they aren’t unshackled, since what they did was forbidden.

The research team is full of interesting characters, who I find tragically under explored. The only couple in the story is wlw, which I vastly appreciated, along with they obviously cared and loved each other and their relationship was not used for drama purposes. In favor of the lack of development with the cast of characters, since the narrator is Murderbot and part of Murderbot’s personality is they are actively trying not to care about these humans, it does make sense. Still, I would have loved to see more of the crew and more development between Murderbot and them.

I like the dark lore that is hinted behind Murderbot’s existence. There’s organic counterparts to their machine made from cloned humans. It’s creepy and morbid, but a lot is with the lore of the universe that the story takes place in. There’s hints towards a heavy capitalist society in space where the humans and Murderbot came from, where the right price will get you anything, regardless of morals. The overall tone of the story is very quirky, but it needs to be to offset just how dark everything that happens actually is. The book explores the concept of corporate greed, from the existence of Murderbot to the deaths that come to humans on the planet the crew is studying.

This book was deeply fascinating, but I didn’t love the way it was written. I love every concept and choice made, but I didn’t love the execution. It left me wanting without satisfaction. It’s not a bad book and I still over all enjoyed it. It is part of a series, which I did not realize at the time of reading it, but the ending leaves room for more to be written, so maybe in the following books there will be the development I desired. However, the ending of the book leaves it apparent that Murderbot will not be interacting with the same characters of the first, but that is just an assumption and I could be wrong. I’m not sure yet if I will read more in the series but I’m not entirely opposed to it.

All the Birds in the Sky - Charlie Jane Anders

This is another one that I definitely would not have read if I had to choose based on the synopsis alone. The synopsis made it sound so run-of-the-mill star-crossed-lovers, which, hey, maybe that actually helps sell the book because its a pretty well loved trope, but for me it was off-putting, as well as isn’t fair to what the book actually turned out to be. But that’s what reviews are for, and I found this book from some sort of list, I think it was best sci-fi books written by women.

The general idea of the book is a witch and a techie fall in love while the world is falling apart due to a conflict between magic and technology. The book is lauded for bending genre and honestly, it fucking has. It’s as equally a sci-fi novel as it is a fantasy novel. There’s advanced technology, such as robots, two second time machines, rocket ships, and ultimately, a portal leading to a different universe in hopes of escaping the destruction of earth. On the magic side, there’s a connection to nature, rules that have to be abided, quirky witches and magicians and mystique. Both Laurence and Patricia are outsiders that have seemingly found these secret niches in the world that becomes their own.

Both plots are interesting in their own, and could possibly exist as two separate books, but what ties the entire story together is the connection Laurence and Patricia have, and their ultimate romance.

The romance is a wonderful slow burn, from childhood friends, to adult friends to lovers. By the time Patricia and Laurence finally get together, you really fucking want them to. They weave in and out of each other’s lives throughout their own personal plots. There’s tensions and there’s release. And most importantly, they have lives outside of each other. Their romance compliments the story, rather than the story being entirely about romance.

Similar to the former review, there’s a lot of quirkiness in the story, that ultimately offsets how dark the story can be. The story doesn’t shy away from complicated relationships with parents and siblings and friends and other people, people of mixed ages and backgrounds. It explores abuse, bullying, natural disaster and loss. The story would have been miserable and a drag to read without the whimsical qualities of it. Plus it’s a fantasy/sci-fi, so it should have some quirkiness to it! And it made for a very enjoyable read!

My criticism for this one is, yet again, the ending. The conflict resolves and the story comes to an end. In favor of how it was written, the way things resolve, I believe the world is about to go through a grand change. While the story is quirky, I think it would have been too corny to have had a glittery magical wave drag across the land, altering the world as it went. So, it’s fair, I guess, that the author chose to end it where she did. Still, it left me craving more. Maybe because the story was so good and I wasn’t yet ready to let it go.

Also, as a side note, the author is a trans woman. So if you’re looking for books written by trans authors to support, put this at the top of your list.

#book review 2020#the shape of water#to be taught if fortunate#All systems red#all the birds in the sky#idk how to write about books and these are only partial reviews/reccomendations so sorry if it sucks#also I plan on adding to this post so better blacklist it now#feel free to recommend things

51 notes

·

View notes

Text

TB#8 || Why a film director has to be a Good reader?

Reading books is a must. There is no denying the fact.

Every story you have heard about people showing up or being in the right place at the right time have one thing in common.

They are wrong and made up.

They eliminate the part where they were desperate, weak and were ready to do anything to get the job and start their stories right from where they got the job.

All those stories are hearsay which you hear from fellow struggling actors and wannabe directors.

Knowing inside stories constitutes one of the most interesting parts of the experience in the film industry and at times makes you passionate and motivate you towards cinema.

Don’t believe in hearsay. That is just random talk done to soothe your mind and it does not affect anything.

To get some verified data, try reading books.

Every great man in history has more or less been a good reader.

If you want to be a film director, a good one, then you have to be a reader.

How else you think you are going to read all those scripts and find the best one from it?

If you are not a good reader then you might end up becoming a director but not a very great one.

I have met directors who don’t even read the scripts.

They rely on their assistants to narrate them the scenes so that they can shoot it. I wonder how they started their career.

It’s either they have good connections or long assistant career.

Do you think they will make good directors?

Never.

Most of these directors are in TV field in which good content does not matter.

Since filmmaking is a specialized field so they never end up becoming a film director because filmmaking requires more meticulous preparation.

Hundreds of hours of writing, reading and re-reading go in before a good film turns out to be good.

I once interviewed the DOP of Rajkumar Hirani, C.K. Muralitharan.

He told me that Rajkumar Hirani and his writing partner Abhijat Joshi goes through more than 300 re-reading and drafting of the same script to make sure there is no fault or loophole in the script.

I believe that if someone goes through that much amount of hard work in making their movies then their films are ought to be a super hit.

None of the films of Hirani is a flop, leave flop, they are all blockbusters.

But why do you need to read books on filmmaking?

1. To know how others made their films and approached filmmaking?

2. To know what mistakes other filmmakers did and how you can avoid them.

3. To know more about films, shot taking, direction and writing.

Being part of any profession there is one thing that everyone must never forget —

The learning should never stop.

Just because you are out of film school or you have managed to make your first film does not mean that you have learned everything about cinema.

Cinema is an art form that has age beyond 100 years now.

There are things that you don’t know and there are things knowing which will make your films not only better but great.

I remember reading books on scriptwriting during my college days because I was interested in filmmaking.

There was a website called Passion for Cinema which would publish film scripts for its readers to read.

I would download them, take their printouts and read then, again and again, to understand how that script was written. Most of those scripts were from Anurag Kashyap.

There is a book by Syd field called “Screenplay: The foundation of Screenwriting” which is considered one of the best books on screenwriting which with the help of a screenplay of Chinatown makes you understand how the story should be written. According to him, the screenplay of Chinatown is one of the greatest screenplays written and he is right about it.

For a filmmaker, you must develop a habit of reading screenplays. They are ubiquitously available on the internet.

Download them and put them into your Kindle, iPad or laptop or whatever gadget you have and start reading them as soon as possible.

Before making The Shining, Stanley Kubrick couldn’t find any book or concept worth devoting his time and talent into.

In his biography written by his assistant, the author narrates how Kubrick would sit in his room entire day and keep reading new books till he found this book by Stephen King called The Shining and decided that it is going to be his next film.

I was once doing an ad film with Anurag Kashyap and one thing I noted about him was that he was continuously reading books throughout the shoot. He would always manage to find time between film direction and read books.

Ever wondered why the great and successful people are not much active on the internet.

It is because they are busy reading books to gather more knowledge and hone their skills.

Reading books gives you more visualization than watching a documentary on the same thing. Visualization is something which is a cornerstone of success for any director.

My biggest asset while reading books was that I got to know that nothing is easy in this world and everything takes its own due course of time.

Some filmmakers start early while some filmmakers start late to make their films.

Ang Lee struggled for six years from age 30 to 36. He was unemployed and kept working on his screenplays and kept polishing them. He submitted his screenplays to few Festivals and won some awards, which further led him to make his films.

The biographies had taught me a lot about film directors, their life, their struggle, their methods and their persistence to make a film.

Some of the best biographies to read are from Satyajit Ray, Andrei Tarkovsky, Kieslowski, Ritwik Ghatak, Martin Scorsese, James Cameron, Steven Spielberg, Robert Rodriguez among others.

You cannot experience everything on film sets and not everyone in the film line will sit with you, help you, guide you in becoming what you want to become.

You need mentors in life. Mentors help you guide in a certain direction and help you show you the way. Books will do the same for you.

Now coming to the practical aspects of how books can help you apart from developing your personality.

When you will be in the film industry people will talk to you about films and if you don’t know anything about the film industry it shows that you are there merely for superficial glamour purposes.

When I first went to Mumbai, I had read hundreds of blogs on filmmaking, read myriads of books and had seen thousands of films so when my first interview happened, I passed it with flying colours. Not only that, I impressed them all.

There were times when I was fortunate to sit with known filmmakers and get to talk to them. Since most of the people at the top of the film industry are avid film buffs and book readers, they were interested in talking to me about cinema theories, philosophies and how it evolved only because I had read so many books, had several anecdotes and trivia to tell.

So many times, it happened with me that due to my borrowed understanding of film writing from books I was given a chance to read scripts and give feedback based on that.

I knew about script structures and everything about them in details and a hundred percent of those times my analysis of the scripts solved their problems and they would keep calling me again and again. Later I started charging money for that. So, can you imagine, reading books helped me developed another source of living? I am not boasting about my skills here as none of this is a natural talent. I had to read numerous books and devote several hours to reach tot his point.

Book also taught me a lot about set blocking. I read a few books on the direction which I researched a lot on blocking of Alfred Hitchcock, who was a master of camera blocking and how the characters move on the screen. So imagine if you go on sets and you see a director setting the actor movements and blocking actors with respect to the camera. A normal person would be clueless about everything but if you had basic, even theoretic knowledge about set blocking, trust me, within two days you will become a pro at it.

The core foundation of developing any art is researching as much about it as possible and then explain it to someone else. If he understands it then you have done a good job. This is not me but Nobel Prize-winning Scientist and Theoretical physicist Feynman who said this.

You need to know how the art has evolved over time. It is not wise to start from beginning and makes the same mistakes that people before you had already made.

One of the best books that you can lay your hand on right now is How to read films. I borrowed the book from someone and I had finished it two times as I loved it so much. This book touches upon pretty much every topic within cinema, be it history, technique, film theory or whatnot.

You should start from reading biographies because they are light to read and then move on to the books which are technical, about art, have philosophy inside it and then read every book that comes near to your Goal.

Reading books gives you the inspiration that you can also do it. It motivates you to go ahead and do it rather than sitting on your ass and brooding how you are going to do it.

While, on one hand, The autobiography of Robert Rodriguez, A Rebel without a Crew, inspired me that I can make my own film in very less money, on the other hand, the biography of James Cameron told me that hard work always pays and if you work really hard to achieve your dream, you can get anything in life.

Reading screenplays taught me how the script must have been first read and then watching the movie on it made me imagine how and what must be going on sets to make those scenes alive. Scenes on paper are nothing but dead words which are made alive by the efforts of the film director, actors and another crew.

I realized my own screenplay style while reading those screenplays. For example, some writers write screenplays in a detailed amount of descriptions (James Cameron) while some writers (Aaron Sorkin) doesn’t write much in the description but are masters of dialogue.

Reading books about filmmaking also separates you from other people who don’t know what goes behind the screen. More than that whenever you will be on sets, you won’t be alien to the majority of things.

The biographies of film directors make you go inside their mind and then you will better understand what was going inside their minds while shooting a particular scene.

While reading the acclaimed director Ritwik Ghatak biography, I realized how great he was. He narrates a scene from his magnum opus Megha Dhake Tara. In that scene, a woman who is tormented from all sides is sitting with her lover. He is about to ditch her and there is the sound of whiplash you hear in the background.

At first, when I saw the film I didn’t notice anything but it affected me. After reading the book I again saw the film and witnessed the scene from another dimension, from the eyes of the director and understood it better.

First time I watched the film from my perspective and the next time I saw it from the perspective of the film director and it educated me with many things which I missed the first time.

Any scene in any film is an amalgamation of visuals, sound, art, acting, editing, camera and hundreds of other things which we feel but are not obvious to us so sometimes you have to get inside the minds of director to understand his film.

I am not just talking about art films but I am also talking about Commercial films where directors often shoot scenes expecting a different effect on the minds of the audience but the audience understands them in a different manner.

Here is a list of books you must begin reading with -

1. In the Blink of an Eye by Walter Murch

2. Shooting to Kill by Christine Vachon

3. On Directing Film by David Mamet

4. Story: Substance, Structure, Style and The Principles of Screenwriting by Robert McKee

5. The Filmmaker’s Handbook, 3rd Edition by Steven Ascher & Edward Pincus

6. Down and Dirty Pictures: Miramax, Sundance, and the Rise of Independent Film by Peter Biskind

7. The 5 Cs of Cinematography: Motion Picture Filming Techniques by Joseph V. Mascelli

8. The Techniques of Film Editing by Karel Reisz

9. Directing: Film Techniques & Aesthetics

10. How to Shoot a Feature Film for Under $10,000

Here is a list of biographies you must read

1. Rebel Without a Crew by Robert Rodriguez

2. Something like an autobiography by Akira Kurosawa

3. Adventures in the Screen Trade by William Goldman

4. Kazan on Directing by Elia Kazan

5. Spike Lee’s Gotta Have It, by Spike Lee

6. The Magic Lantern, by Ingmar Bergman

7. Sculpting in Time, by Andrey Tarkovsky

8. Speaking of Films, by Satyajit Ray

9. Jean-Luc Godard — Godard on Godard

10. Luis Buñuel — My Last Sigh

Here is a list of screenplays should begin reading with.

1. Casablanca

2. Psycho

3. Chinatown

4. The Godfather

5. American Beauty

6. Memento

7. Eternal Sunshine of a Spotless Mind

8. The Sting

9. Pulp Fiction

10. 12 Angry Men

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Podcasts & Structure

Every time I get around to sitting down and actually writing these articles, I have to seriously consider what I’m going to talk about. It seems the conversation of audio drama is becoming more widespread lately, oozing its way into mainstream media faster than I can keep track of.

And so many are being made at such a rapid pace, catching up with it all can be its own challenge. A lot of people are starting to see the power and potential of audio plays and it’s a slow burn revolution I am a hundred percent behind.

When I achieve my dreams of becoming a licensed journalist under that sweet, sweet trademark PodCake©, know that I’ll be somewhere in the front lines, keeping everyone up to the date and in the zone until I’m old and gray and still very, very pink.

So with this exciting idea in mind, I find it appropriate to do a somewhat different type of “Podcasts&”. This is still very much an article dabbling into my specific interests and experiences though also a guide of sorts to those who may be wrapped up in the creative hype. Allow me to pull you starry-eyed artists aside for some well-meaning advice. May you follow in the footsteps of your idols, though know you are above any of their common mistakes.

I had a few options in store to pick from when it came to another topic covering audio drama critique, though I felt that I wanted to address this first. This is another dabbling into the more specific structures of my podcast journalism and the consumption and creation of audio drama in general.

In a similar vain to my latest article, “Podcasts & Critique”, I’ll be talking about something that perhaps not many are willing to discuss out in the open but is certainly touched upon enough that I feel the merits to bring it up in more depth. What we will be discussing today is the element of effective story structure.

Get comfortable, this is gonna be a long one.

Let me start by saying that I adore and always will adore a nice, rich setting presented only through words. I adore lavishly designed dystopias and lively apocalyptic wastelands more than the next guy and the idea of a soothing, sweet voice cooing to us over a delicately designed world is a surefire way to ensure a fanbase. This is the popular set up known as The Newscaster or The Fake Radio Show or Handsome Male Character Headcannon Sitting in a Big Chair or whatever you want to call it.

I enjoy this format namely for its simplicity and ability to relay information to the listener all while still characterizing the narrator as an active part of the world. Though these shows might be more episodic, to a degree, the ideas are still being connected by one single thread. It’s such a regular aspect of the podcast scene that it’s nothing short of being a style.

This style places a lot of emphasis on lore and quirks and memorable little moments that arrange themselves into a little audio scrapbook. We’re given this collection of information, all gorgeously described in luscious detail.

That’s why it’s such a shame how boring it can be at times.

Don’t get me wrong here, my problem is not with interesting landscapes and rich lore, my problem is when a lot is being said but not enough is being done.

I fell out of love with Welcome to Night Vale for this particular reason, this inconsistency with stakes and conflict that made any enjoyment to be found quickly tedious. Night Vale is and always will be a staple in the audio drama community, though it doesn’t mean we can’t learn from its mistakes that may go over our heads due to its excellent writing and characters only sometimes overshadowing it.

I’ve said it before and I’ll say it again: an excellent audio drama is the sum of many parts and only succeeding in one area won’t always make the cut. But today’s topic is less about writing and more about narrative pacing…which is still kind of about writing but in a different way.

The central issue with these types of single narrator driven shows, being that we are being presented with a setting, problems, and characters who can solve that problem, but an effort is rarely ever made to get to a satisfying conclusion that is worth the wait. Of course, there actually being conflict to resolve can be its own and even more disappointing dilemma.

A crowning example of this type of flaw occurred in what used to be one of my favorite audio drama comedies, Kakos Industries.

I promptly stopped listening to Kakos after a lackluster attempt at it’s first real arc after roughly fifty episodes of filler and build up that didn’t contribute much to whatever the arc was trying to get across. None of the past episodes helped create a central theme that the arc was meant to represent, making its conclusion lack any emotional stakes or a reason to get invested.

The primary mood of the arc was all over the place with rapid character changes, unclear motivations, and a rushed explanation behind multiple episodes with little to no foreshadow to back it up. Furthermore this supposedly crucial ending didn’t tie into the continuation of season three beyond the absence of the past antagonist who was the center of the whole thing and the victim of a bloated backstory that needed way more than twenty minutes to be summarized.

No one changes from the whole ordeal, not even the protagonist who goes about his daily life as if none of it ever happened, and nobody and nothing is lost from the whole thing besides the character we already knew was bound to kick the bucket because it needed to end somehow. Generally, it does everything arc is not supposed to do as it doesn’t act as a changing phase for the story and doesn’t give us any vital information that will effect any of the characters long term.

The problem also lies in that there are a number of interesting subplots that emerged within the show’s canon as of season two: some more details about head rival Melantha Murther that imply she may be older than she seems, the relationship she has with Corin Deeth I as well as his involvement with the company, and a theory about cloning being brought up to name a few, but we have yet to even gently nudge at these ideas yet for a good batch of episodes because we wouldn’t want all those penis jokes to go to waste.

This is content with potential to be interesting arcs on their own and functional ones as they key into new information about characters we’ve come to know and gives Kakos Industries the tension and mystery it desperately needs.

These little bits and pieces of information can keep a listener engaged long enough to keep tuning in, but it can quickly become a chore to go back to something that seems to have been forgotten in exchange for repeated jokes and some new standalone characters that don’t really matter.

These might be in the footnotes of the creators for episode whenever, though to us they feel like throwaway lines pitched as bait more than anything of actual importance. They’re just there to be there.

And when the show peddles back to its roots of everyday shenanigans and jokes, the luster is lost, no matter how funny or well executed they might be. In the end, a lot of gimmicks and a lot of chatter with no real weight becomes nothing short of a series of filler episodes with no purpose.

I understand that indifference and dissonant serenity is part of the Kakos Industries’ humor though it often comes at the cost of events not carrying any real weight because it’s already predetermined that it’s being treated like a joke or that things will be resolved and go back to status quo with minimal effort. It insists you don’t take it seriously even if the problem at hand would suggest otherwise. To anyone else listening, this makes the stakes nonexistent and the protagonist seem overqualified to handle any problem thrown at him, never giving him a chance to be vulnerable to the slightest misfortune.

The same could be said for Welcome to Night Vale, a show with many compelling ideas and character drama though one that loves to meander and reestablish how strange and bizarre their world is on repeat instead of doing anything of actual substance, at least as far as season three is concerned.

Night Vale has a much better grip on characters and conflict that Kakos Industries does, though it also suffers from some of the same problems. Night Vale also had arcs, one incredibly well done to the point it’s been considered a crowning moment of the series while another that wavered a bit too long and simply wasn’t intriguing enough to make a huge difference in the end besides being another case of the Put On the Bus trope. And when they concluded, we’re back to square one again.

Once again, we are given a lot of ripe material here: There’s instances of Cecil’s childhood that we must piece together, pretty much anything about Kevin is bound to be creepy and interesting, Carlos and his apparent involvement with a college university, and something about sleeper agents and traffic signs and blood space but I lost count.

The case here is almost as dire as this is something of a multiple choice scenario where there’s just piles and piles of plots being given to us but all of it feels for naught when something else is being added to the collection a second later.

The same way Kakos is so obsessed with its dark and sexy aesthetic to the point it under develops its characters and has an absence of stakes, Night Vale is the same with its surrealism and seems to pull the “it’s a weird show” card whenever something gets unresolved.

There comes a point where a show’s quirky nature can only be used for so long to avoid the big question about what it’s all in service of. If all the oddness has no meaning and the plots are just being pitched with no real agency, then they fail to provide the show with any real purpose.

The point of an arc ending is for another one to start later, namely by picking up leftover plot points from before or starting something else that still entwines with the story’s central lore.

For a good example of how to manage an arc, I’d recommend Wolf 359 that has at least four in the duration of about forty episodes. I’d go into more detail about exactly what made the individual arcs in Wolf 359 work so well though that would lean heavily into spoiler territory and I wouldn’t want to ruin anything for those who haven’t listened to it yet.

This too started as a sort of news caster from space format until it flourished into the characters offering their points of view on a scenario and developing as people as they are placed in tight spots.

We learn more about who we’re dealing with, what is at stake, and grow invested because we never know which direction the events can take us. Wolf 359 has become so successful in its run because of the writer’s ability to admit something is amiss which gives the listeners something to anticipate rather than just tolerate.

Listen here, I know that podcasts are all for entertainment’s sake and I will always respect that, but even something that is entertaining must have a hook-line-sinker mentality, as I like to call it:

The hook is the first impression: What made you want to listen in the first place? Did the general synopsis intrigue you? Maybe there was just an actor in the show that you really like. Simple.

The line is the plot: This is the thing that makes you keep coming back for more. You’ve gotten comfortable with the story and its characters, you want to know as much as you can about the lore and the stakes. This is very much literally “a line” the audio drama is following and encourages you to keep up with.

The sinker is the payoff: This is where all the accumulated information you’ve gathered really matters-the climax. This is where we get the hidden motivations of characters, know about the dark secrets and figure out who the heroes and villains might be. We have a winner and a loser or at least some kind of ending, be it good or bad for the protagonists.

Many podcasts are capable of the first two steps though tend to forget the third. And when we do forget to touch that oh-so crucial sense of conflict and resolution, it becomes the equivalent of a Breather Episode series.

To those who don’t know, a Breather Episode is a common trope that is put into place to remind the audience that all of the past problems have concluded and we can once again revel in comedy and lighthearted fun.

I am a big fan of the this trope, it’s an implication that the past troubles of our protagonists have been dealt with and they can now relax, getting back to basics, but it’s getting back to the old grind that really matters.

We as listeners are a bit bloodthirsty, to say the least, constantly seeking out what new thing might be out to threaten the characters and disrupt their tranquility. Though in the character’s universe, and, to some extent, the writers, this is a pleasant period to soak in for a bit for just a little while.

It is prone to overstay its welcome if the average episode is nothing to look forward to. In short, if there’s nothing to hold on to, people will drop your story knowing it was of no loss to them.

A constant barrage of drama can be very overwhelming to the story’s ability to stay surprising and believable, so it’s good to have that even blend of “the bleeder and the breather”, as I’d like to call it, to keep things balanced.

But Podcake, you might be saying. This is audio drama! Emphasis on audio. They’re just sounds! Why expect so much when we can’t get visual input?

And you have a point there metaphorical reader. I’m not saying every show needs this epic score, high budget, and groundbreaking editing, I actually encourage shows who rely on this minimalism to try even harder in the writing department.

It is actually possible to have a consistent sense of tension even with limited sound effects and budget.

A good example would be The Bright Sessions. The presentation is mostly contained in one room and only occasionally stepping outside of it to overhear conversations. Despite the format being mostly casual and calm, there is still a pressing sense of drama and conflict we keep coming back to. And when we do get “the breather” in between, it’s a welcome change until going right back to where we started.

This is because the show stands on its own two feet in the dialogue department to get their point across and let things flow naturally. No big pizzazz or flashiness, just saying what it needs to say.

And if you insist on the superb audio editing part of this, I’d say Hadron Gospel Hour is always an recommendation, as well as defining the even blend of episodic with tension combination.

Gospel Hour is a sci-fi comedy with multiple unrelated cutaway gags and strange characters that have events in episodes that may not always be highly relevant to the next. But this has yet to cripple the storytelling since there are always connecting threads our protagonists go back to that develop their backstory or truly emphasize the dire circumstances they’ve been put in, something I’ve begun to notice in later episodes.

And if you’re still concerned about arcs, The Once and Future Nerd has the decency to have well established and satisfying beginnings, middles, and ends to each chapter. They have a wide and vast world to explore and take any opportunities they can to remind you of the fantastical yet still dangerous and grisly setting.

And maybe you’re really stuck on the newscaster format. Fine, I like those shows too. From here I’d highly encourage The Bridge: a show with a rather complex world, decently sized cast, and a steady increase in drama that isn’t afraid to step back from the main character’s perspective to tell a complete story.

Sorry to name drop so much in this particular document, though this is a narrative problem I’ve seen so often and so poorly I want to save anyone attempting this style from the same shortcomings. If you enjoy these shows for that exact reason, that is completely fine, though don’t be afraid to ask for something more genuine than just empty world building.

A good story is what you make of it but a memorable story can be much more.

#podcast#audio drama#audio play#radio drama#radio play#podcasts and#welcome to night vale#kakos industries#the once and future nerd#the bridge#the bridge podcast#hadron gospel hour#the bright sessions#wolf 359#wolf 359 podcast

213 notes

·

View notes

Text

Will artificial intelligence be able to replace novelists?

Before I begin

Yes, I have watched Humans Need Not Apply.

Yes. I have watched multiple videos and have read multiple articles on A.I. innovation in regards to writing fiction and I’ve used a few short story generators. They’re terrifying to say the least.

If all you do is theorize about A.I., I don’t want your input. I want someone who has actually studied A.I. and machine learning to answer this for me. I don’t mean to sound harsh, but I just want something that’s closest to the truth on how A.I. works and how it’ll master the craft of prose.

Please refrain from being condescending when you answer my question. This post is already depressing and anxiety-inducing enough and I kindly ask you to be considerate of how you answer me. Of course, I want the truth but there’s a difference between “Yes, AI will be able to surpass human ability to write novels” vs “Yes, AI will create better stories than you. Don’t deny it by thinking you’re some special creative snowflake.” As someone who has poured their heart into the craft of novel writing for over five years, this is a very hard pill for me to swallow.

Lastly, I humbly ask for you to watch all the linked videos and read my embedded links thoroughly for you to understand my question completely.

The Immense Progress of AI Music Has Me Worried

Quite a few years ago, I heard the first ever AI generated piece of music. It was laughably bad and everyone in the comments agreed. However, the other day after stumbling upon this Oh, I did see on a video that this piece was arranged by a human.

But still, given that the time between the first AI piece of music and this piece of music is just a few short years shows that technology is accelerating at a speed that it never has before.

Stories are structure and a Mix of Ideas

This is a no-brainer. AI can surely learn this. Story structure is well… structure. And AI is excellent at that.

Each chapter is meant to push the story forward in a meaningful way. Every scene is meant to do this, too.

Oh, and the reason why I’m using her videos is because she’s an editor and knows her stuff.

But…

Will Artificial Intelligence Ever Understand “Why”?

Why = The deeper understanding of what this event / character arc / scene / and even sentence means for the greater context of the story. Oftentimes, the greater context of the story is the central philosophical / moral question.

This example of applying plot structure to themes and character arcs is a good example of the “why” I’m referring to. She is able to seamlessly take a (funnily enough) AI generated plot yet give it meaning by understanding how all the components interact with one another. Please share your thoughts on this.

I might even go as far as to say that editors like her - Ellen Brock - will be difficult to replace because she is able to comprehend the words being written / said and help her client understand how to achieve their writing goals through their specific vision / goals for the story they want to write. What do you think of this? Will novel-writing AI be able to connect abstract concepts together?

The concept of comprehension is what leads me to my next point.

The Structure of Music vs Word Salad

Music and novels have one glaring similarity that terrifies me - they are both highly structured. But one difference I can see between them is that music is a series of pleasing notes while books are a series of pleasing words… and every novel ever written is different.

The main reasons being:

1) The specific voice of the author, how they perceive the world around them, and how they filter that perspective through into their stories.

2) Even among different books authors will shift their “voice” in order to fit the inner voice of the different character. For instance, a child narrator won’t think the same as an adult narrator.

3) Every character is different and it might prove to be a challenge to keep them internally consistent if all their dialogue is scanned from other books and mashed together. Additionally, characters can sometimes exhibit different qualities - showing new “sides” of themselves - which will further add to their distinction.

4) Every author describes settings, sensory detail, and the inner thoughts of their characters differently.

From what I know about AI, it uses deep-learning algorithms as well as scans every book in existence

But when it scans every book ever won’t it be bogged down by all the variation of the authors?

This variation and highly subjective interpretation of prose leads me to my next point.

Theory One: The Word Salad Rough Draft

This is just a theory based on my miniscule knowledge of AI. I know nothing about AI which is why I’m here in the first place.

One thing I noticed while listening to this was how the AI managed to understand Rowling’s specific phrasing and how words correlated with each other. Of course, what was missing was the lack of understanding of the words and the scene’s significance in the overall story - hence why it was hilarious and jumbled.

Example: Chapters.

How I think the AI will work

In the future, if a novelist has, say, a chapter outline for their book and plugs it into an AI, it might do something like this to comprehend it.

Idea for a Middle-Grade novel: Norra is walking in the park when she steps on a snake. The snake bites her, causing terrible pain, and the chapter ends with her being rushed to the hospital.

The AI, since it has been instructed to write the first chapter of a middle grade novel, will scan every middle-grade novel in existence and take average chapter length and vocabulary into account.

Then, the AI will scan the words: “Norra”, “Walking”, “Park”, “Snake”, “Pain”, and “Hospital.” Then, it will take all these words and find them in other Middle-Grade books and find how the words correlate with each other.

This is what I came up with as a possible chapter example.

“Nora was happily skipping around in the mud in the park when she saw an eagle soaring through the sky. Then, she goes off and climbs a tree with her bare feet. She digs and tries as hard as she can to find the beautiful treasure hidden under the sand yet the slippery substance keeps washing through her fingers. She finds a snake in the sand and screams. The snake lunges at her, fangs bared and hissing like a wild cat. The trees around Nora were heavy with fruit and the bushes were bursting with vibrant wildflowers. The snake bites her face and she screams like a banshee. She is rushed off to the hospital where a mean doctor puts an oxygen mask over her face and tells her that she’ll arrive safely and that her asthma attack will soon be over.”

As you can see, I did use all the words but I intentionally changed the style from simplistic writing to more higher-level Middle-Grade at random. Sure, the sentences themselves made sense but together they were just… weird.

How will AI be able to write better prose than humans since a combination of all the books in the desired genre have so much stylistic difference between them?

Now, we could request the AI to narrow it down like this:

Write a book about: A young boy going into a magical world, climbing a high mountain, and riding an elephant before returning home as a braver and kinder version of himself.

Write in the style of: Jane Yolen and J.K. Rowling.

Due to these two styles of writing being pretty different, I don’t see anything all that great coming from the product. Furthermore, if the author has only written a limited number of books, the AI can’t scan something that has never been written.

Example Two: Characters

How I think the AI will work

I could see this being even more difficult to tackle the nuance of body language, dialogue, interaction between a different web of characters, and, having the character’s progression and speech feel natural and make sense within the context of the story. What do you think of this?

The AI will request a basic overview of my character. For example: “The side character’s name is Ned. Ned is overconfident and will learn to control his impulsive nature by the end of the story.”

It will probably request the genre I want (YA fiction) and go through every single overly confident character in existence. Then, it will generate dialogue.

“Hey! I got this!”

“You’re not the boss of me!”

“What a loser. Don’t listen to him. I’ve gotcha covered.”

“I can’t believe you’re such a chicken!”

These sound like typical phrases from an overly confident kid. But since these randomly generated phrases are not what my character would say this would make the AI rough draft even less helpful. It’s not worth the mental effort of sifting through out-of-context dialogue in order to find out how Ned would interact with my separate set of characters. Not only this, it might run the risk of making Ned a cliche since the AI is probably programmed to scan the most commonly said phrases.

What this would mean for human novelists.

My thinking is that AI could help real authors write rough drafts for their novels. But since AI-produced rough drafts would be full of inconsistent word salad, it would actually be more productive for humans to simply write their own rough drafts and write… well, normally. The author understands what they’re trying to achieve while the AI does not.

What do you think about my first theory?

Theory Two: Self Awareness Beyond our Comprehension

Now that I’ve addressed several potential pitfalls that are preventing AI to write novels, I think the biggest thing that’s stopping AI from doing this is comprehension of the written word, a deeper understanding of it, and self-awareness. What do you think about this?

One thing to consider is the fact that AI intelligence will go beyond our human understanding. This might have us conclude that AI will simply become genius authors pumping out year New York Times best sellers every two seconds, but if you really think about, AI is not limited to the human form as all past geniuses have been.

They will not grow old, sick, tired, or spiral into insanity. They are not limited to the human form. Why do we connect with the works of literature now? Because they were people like us - and limited like us. Their brains were far beyond ours and their human limitation grounded their potential and grounded their experiences.

Imagine handing a novel to a young child. It is beyond their comprehension. Even the brightest of children (3-5 years old) could never read YA fiction. Why? There is a massive gulf of mental development between teenagers and children. Now, apply this concept of “gulf of intelligence” to AI and humans.

AI is, theoretically, not limited by anything. It can write in all the languages that humanity has created. It can write entire novels in code and create new words that we’ve never seen before. You know how English is derived from other languages? Well, since AI is not limited to human form / mental capacity / time then surely would it be able to create whole new languages?

Not only this, but since it’s self-aware and AI is writing stories for itself, it could possibly get “bored” of stories that humans like and vary up the structure. Say, having ten character arcs, twelve acts in each story, and having one chapter last hundreds of pages.

Basically, if AI became self-aware (which might be the requirement for it to understand the nuance of prose) it would create stories beyond human comprehension and enjoyment.

What this would mean for human novelists

For a few years, human writers would be terrified of being replaced. However, when the AI’s intelligence surpasses human reader’s enjoyment it will create a way for human writers once again.

Theory Three: The AI Becomes A Perfect Mimic

How I think this AI would work

It will scan every single novel perfectly - understand everything there is to know about stories - and just… write amazing novels that are stylistic and have complex characters.

This is the scariest theory of them all. Basically, since the AI won’t need to be self-aware, it will only do what it was programmed to do - write excellent novels.

But even then, there is still hope. Let’s say AI produces millions of novels within a few years. (Gotta remember, AI is not limited by alcoholism that way human authors are.) This will flood the scannable novel market that will only have slight variations of human works. Considering that even the most prolific human authors can produce 1-2 books a year max, this will lead to readers catching on to how similar every AI novel is. It could be possible that AI could produce more novels in a few years than the history of human authors combined.

So, that being said, there’s the possibility AI books could write themselves in a corner. What do you think about this?

What this would mean for human novelists

This would mean that novelists will simply have to do with only writing stories for themselves - and not be able to share their art with the world because the market is flooded with AI books. This would also result in novelists having to constantly prove to others that they are the real author which could be rather difficult to do. OR if AI does write itself into a corner - it would open the market again for human novels.

Closing Questions

What do you think of my theories?

Did one theory in particular stand out to you? If so, why?

Do you think AI can write novels that will compete against real authors?

If so, when? I’m hoping something like this happens no sooner than 4-5 decades from now.

After reading my theories, do you think AI novelists would require self-awareness in order to understand the deeper meaning of their prose?

If so, why or why not?

Do you consider novel-writing a “harder egg to crack” than music composition? Why or why not?

Food For Thought

I know my theories have been focused on how the AI will impact the novel-writing sphere but there is another thing I want you to consider. As novelists, we derive meaning from writing our books. Everyday we confront the blank page and, through many hours of hard work and dedication, we can bring our vision of our stories to life. We have something to say - something to express to the world. An AI has nothing to express.

If AI just makes novel writing super easy, it takes away the value it has to the human author. The struggle, the joys, the journey, the stories’ gradual evolution from an inkling of ideas to a fully fleshed-out manuscript for others to love and enjoy - is what gives our lives a sense of purpose and place in the world. If you’re a programmer considering producing novel-writing software, I beg for you to reconsider your choice.

submitted by /u/TempestheDragon [link] [comments] source https://www.reddit.com/r/Futurology/comments/gwsafj/will_artificial_intelligence_be_able_to_replace/

0 notes

Link

“Of course my discourse is disjointed, how could it be otherwise? Bring me a complete subject and I will give you coherence.”

— from “Arista Manuscript,” Experts Are Puzzled

¤

A FEW MONTHS AGO, I did something I don’t often do: I bought a book I knew nothing about by an author whose name I did not recognize. Intrigued by the faint circles orbiting the dark purple cover, I picked it up and encountered an exceptionally perplexing string of words:

At least, that is to say, I am a stranger of a fixed old age and I am not puzzled. Ask me anything you like and I will give you a not-puzzled answer. I will not give you an answer. I am a stranger. I do not live, I am only alive. I hear the birds with lice under their wings singing, but I do not understand because I am not a bird with lice under my wings singing. I am not an expert, I am not puzzled.

Originally published in 1930, Laura Riding’s Experts Are Puzzled was reissued in 2018 by Ugly Duckling Presse. The thin but dense collection comprises essayistic fiction, fictional essays, philosophical conundrums, mythical allegories, and elliptical polemics that blur the line between author and narrator.

A first encounter with Experts Are Puzzled is like trying to decipher a map of a foreign city, or being thrust headfirst into a raging river. The 144 pages take the shape of an extended koan, an evocatively, frustratingly impenetrable work. Initially I could only make out the scaffolding: a narrator considers discussing another woman with her handyman, an essay on money begins by asserting “this is not an essay on money,” a creation story hinges on a narcissistic fantasy. There is a candid interview with God. Characters act begrudgingly, if at all. Stories fold into stories. Tangents are followed and abruptly abandoned. Riding relishes running conceptual circles around her readers with rhetoric that takes on the confident stance of logic, but bends, readily and reliably, to the will of nonsense.

By my second and third read through I began to find my bearings; I could swim against the tide long enough to look around, to slow the rushing words. The characters work as stage props more than people, sometimes tactlessly so. They are allegorical vessels for Riding’s real preoccupations: the potential of language to render reality, a spiritual inclination toward oneness, and the way that stories both muddle and reveal truth. Like many writers, Riding is obsessed with the contours of her craft. She writes in spite of (to spite?) the failure of words to exactly emulate the world.

We see her turning over similar themes in her poetry, as in “The World And I��:

This is not exactly what I mean Any more than the sun is the sun. But how to mean more closely If the sun shines but approximately? What a world of awkwardness! What hostile implements of sense! Perhaps this is as close a meaning As perhaps becomes such knowing. Else I think the world and I Must live together as strangers and die —

Riding wants to know “how to mean more closely” with only these “hostile implements of sense,” our imperfect language. How can we know the world fully if we cannot do more than approximate it? This is ultimately her lifelong project, her greatest thorn, and the connective tissue that runs throughout Experts Are Puzzled. What would it mean to access pure truth in language, unmediated by complex interpretation? Her approach to the problem is cubist in nature; meaning is derived from the amalgamation of disparate parts, and the result is gripping.

Repetitive phrases, paradoxes (“I do not live, I am only alive”), and double negatives (“not hopelessly not amused”) reinforce the arbitrary nature of language and add an almost compulsive energy to the text. But these moments of collision also conjure something beyond words — dissonance creates space for a more complete conception of truth. Thinking about it this way locates the strength of her sentences in their roiling tides, how they build and crash. The contradictions create a tension, and this tension enables a sense of balance. In a piece titled “Dora,” which spans just two pages, Riding dedicates almost half her words to this matter:

First Dora asked about the metal strips. They are about eighteen inches long. One is nailed in a horizontal position over the door of my bedroom, the other in a vertical position between two vertical panels within the room. I put them there originally to be a statement, as metal upon wood may be a statement; a statement of one thing, anything, and a statement of another thing, anything, that was equal parts contradiction and affirmation of it, so that together the two strips made a statement of the nature of suspense, which is freedom; that is, freedom is suspense and suspense is freedom; and, further, freedom is everything, suspense is nothing; and so, further, question?

I found myself sketching diagrams in the margins in an attempt to determine whether the string that seems to hold the fragments together actually exists (to mixed results). But this penchant for nonsense is critical to Riding’s genius. She makes her readers do the heavy lifting, or sit in befuddlement, or read a sentence 15 times over. She is obstinate. Certain. Intense. At times, however, it feels as if Riding is drowning in her own style; her sentences overtake themselves.

Still, there is something seductive in this perversion of language, and Riding’s description of sex in her story “Sex, Too” makes an equally good description of her prose: “It is a roundabout way of arriving at a point that could not be found if it were aimed at directly.” The point is not the plot, but the structure: the terrifying largeness of the world contrasted with the contained smallness of a story. Riding’s storytelling makes these contrasts unmistakable as she rations out abstraction and specificity in precise doses:

She was a Prostitute of lost prime, her skirt trailed the dust, and at sunset she began her long, lonely but resolute walk upon the opposite bank of the river, from the Bridge to the Ferry, and then back and then back until the night forgot her. And on this bank small boys followed her Progress, calling a Name, to which she replied with Language. And the men of the Power Station called after her also, and bitterly across the water did she reply; and her replies rang bitterer and bitterer, until the men of the Power Station stopped their ears and thought shamefully of their wives.

Here we’re placed into a scene, laced with inexactitudes, but nonetheless resonant. Then we’re yanked out of it as fish on a line: “And I have nearly told you a story” she tells us. “But no matter, if it makes a smaller world.”

Born Laura Reichenthal on January 16, 1901, Laura Riding — later Laura Riding Jackson — was a prolific writer regarded primarily for her poetry. Her father was a first-generation Jewish immigrant and a socialist. Riding grew up impoverished in New York City, earned a scholarship to Cornell University, and went on to win a poetry prize judged by the Fugitives, a group of Southern writers including Allen Tate. She carried on a notorious relationship with the British poet Robert Graves, with whom she collaborated on “A Survey of Modernist Poetry,” and together established Seizin Press. Known by all to be polarizing, bright, and outspoken, she was a woman who believed she had something to say — and willed herself to be heard. Having spent much of her adult life striving toward a poetic utopian ideal, she ultimately determined poetry to be an insufficient conduit for truth and, in 1940, renounced the form completely. She married Schuyler Jackson in 1941 and settled in Florida, where she focused on other linguistic efforts in pursuit of a new, more accurate paradigm of language until her death in 1991.

Today, her legacy teeters between revival and oblivion (her prose especially, being less considered and less acclaimed than her poetry). A controversial figure who strove to set herself apart, Riding has been called manipulative, obsessive, and wicked, her work deemed both masterpiece and migraine. A 1993 New York Times article lists among her detractors Virginia Woolf, William Carlos Williams, Louise Bogan, Dudley Fitts, and Dorothy L. Sayers. The article continues, “Judging by the caliber of her enemies, we might assume that Laura Riding did something right.” Alongside her critics, Riding also earned her fair share of devoted admirers.