#woody braxton

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

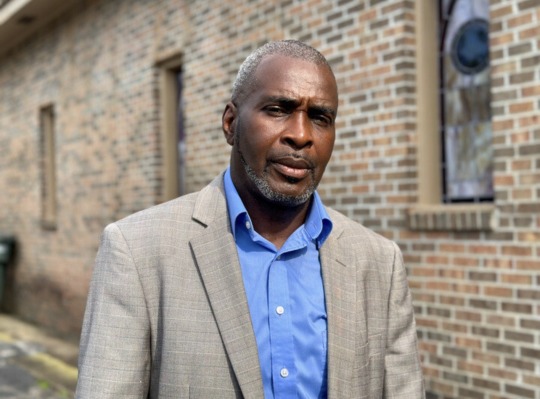

Patrick Braxton became the first Black mayor of Newbern, Alabama, when he was elected in 2020, but since then he has fought with the previous administration to actually serve in office. (Aallyah Wright/Capital B)

NEWBERN, Ala. — There’s a power struggle in Newbern, Alabama, and the rural town’s first Black mayor is at war with the previous administration who he says locked him out of Town Hall.

After years of racist harassment and intimidation, Patrick Braxton is fed up, and in a federal civil rights lawsuit he is accusing town officials of conspiring to deny his civil rights and his position because of his race.

“When I first became mayor, [a white woman told me] the town was not ready for a Black mayor,” Braxton recalls.

The town is 85% Black, and 29% of Black people here live below the poverty line.

“What did she mean by the town wasn’t ready for a Black mayor? They, meaning white people?” Capital B asked.

“Yes. No change,” Braxton says.

Decades removed from a seemingly Jim Crow South, white people continue to thwart Black political progress by refusing to allow them to govern themselves or participate in the country’s democracy, several residents told Capital B. While litigation may take months or years to resolve, Braxton and community members are working to organize voter education, registration, and transportation ahead of the 2024 general election.

But the tension has been brewing for years.

Two years ago, Braxton says he was the only volunteer firefighter in his department to respond to a tree fire near a Black person’s home in the town of 275 people. As Braxton, 57, actively worked to put out the fire, he says, one of his white colleagues tried to take the keys to his fire truck to keep him from using it.

In another incident, Braxton, who was off duty at the time, overheard an emergency dispatch call for a Black woman experiencing a heart attack. He drove to the fire station to retrieve the automated external defibrillator, or AED machine, but the locks were changed, so he couldn’t get into the facility. He raced back to his house, grabbed his personal machine, and drove over to the house, but he didn’t make it in time to save her. Braxton wasn’t able to gain access to the building or equipment until the Hale County Emergency Management Agency director intervened, the lawsuit said.

“I have been on several house fires by myself,” Braxton says. “They hear the radio and wouldn’t come. I know they hear it because I called dispatch, and dispatch set the tone call three or four times for Newbern because we got a certain tone.”

This has become the new norm for Braxton ever since he became the first Black mayor of his hometown in 2020. For the past three years, he’s been fighting to serve and hold on to the title of mayor, first reported by Lee Hedgepeth, a freelance journalist based in Alabama.

Incorporated in 1854, Newbern, Alabama, today has a population of 275 people — 85% of whom are Black. (Aallyah Wright/Capital B)

Not only has he been locked out of the town hall and fought fires alone, but he’s been followed by a drone and unable to retrieve the town’s mail and financial accounts, he says. Rather than concede, Haywood “Woody” Stokes III, the former white mayor, along with his council members, reappointed themselves to their positions after ordering a special election that no one knew about.

Braxton is suing them, the People’s Bank of Greensboro, and the postmaster at the U.S. Post Office.

For at least 60 years, there’s never been an election in the town. Instead, the mantle has been treated as a “hand me down” by the small percentage of white residents, according to several residents Capital B interviewed. After being the only one to submit qualifying paperwork and statement of economic interests, Braxton became the mayor.

(continue reading)

#politics#white supremacy#patrick braxton#woody stokes#republicans#alabama#sundown towns#racism#voter suppression

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

Newbern, Alabama is a small town. At it's heyday in the 1880s the population was 562. Today just about 150 people live there, with the population falling by 20% per decade for the past two decades.

It's a tiny town but there are residents who care about its future. One is Patrick Braxton, who started to question how the town was being run when working as a volunteer firefighter and during the early days of COVID.

The official leadership seemed unresponsive and even hostile. Newbern is majority black, but like many small towns in the Black Belt the town leadership is all white. Newbern has historically not had elections for Mayor--

Some residents from First Baptist Church of Newbern are fed up. Braxton among them. The small funds the Mayor controls are not spent with transparency. COVID supplies were squandered. When Patrick Braxton put up signs encouraging people to get vaccinated the signs were thrown in the burn heap.

So Braxton decided to run for mayor.

There is a process to have mayoral elections, Patrick Braxton found the paperwork despite obstruction from the city council. The existing mayor Haywood “Woody” Stokes III ignored him and didn't bother to run so Braxton won by default managing to get recognized by the county. Then, shortly after, the white town council met secretly and reappointed (??) Haywood “Woody” Stokes III as Mayor. It's an old typical situation. Here's the best article I found:

One other thing:

This kind of annoying headache inducing super local nit picky local politics is *the most important kind of political battle right now*

Power is built from these tiny councils up-- and the structures that keep all manner of "outsiders" from participating, or even knowing what they are doing need to be destroyed -- one little town at a time. Get the school board too.

If you live in a small town and don't know who the mayor is or what he does.

Maybe YOU should be the mayor.

One more note: The man's name is Haywood “Woody” Stokes III Haywood “Woody” Stokes III! I mean...

#racism#black belt#AL#us politics#small town america#small towns#small town#black tumblr#the south#down south#Haywood “Woody” Stokes III#Patrick Braxton

91 notes

·

View notes

Text

In 1965, Congress passed the Voting Rights Act, a landmark statute designed to dramatically increase Black people’s participation in electoral politics after centuries of slavery, segregation, and second-class citizenship. Newbern, Alabama, a small town in which two-thirds of 133 residents are Black, has not held a municipal election for some 60 years. What a coincidence!

In place of a democratically elected government, the town, which is located about an hour south of Tuscaloosa, has been ruled by a small group of white people who handpick their mayoral and town council in a form of hand-me-down governance. In recent years, some of Newbern’s residents have sought to change that. In a recent filing in federal court, the residents argue that the town’s failure to hold elections violates residents’ rights under the Voting Rights Act and the Constitution, and ask the court to order the town to hold an election by November 2024.

The case is striking for multiple reasons, including, most obviously, the absurdity of the purported government’s departure from fundamental democratic principles. It is also a stark reminder of the real-world impact of federal courts in a political and legal system dominated by reactionary conservatives. Liberals are asking judges for small victories, launching last-ditch efforts to access basic rights under the Constitution. Conservatives, in contrast, are aiming much higher: For them, courts are a testing ground for novel ways to curtail rights nationwide. In federal trial courts, conservatives are having their cake and eating it too, while liberals are begging for crumbs.

youtube

The plaintiff in this case is Patrick Braxton, a Black Newbern resident who, in 2020, filed the actual, long-ignored paperwork to run for mayor. As the only legally qualified candidate, he won by default, and tried to appoint a town council accordingly. The existing town council responded by convening a secret meeting during which it decided to conduct the town’s first-ever special election. Telling no one about the new “election,” the previous mayor, Haywood “Woody” Stokes III, and his council effectively reappointed themselves to their jobs. Stokes and his cronies have since repeatedly changed the locks at town hall as part of a refusal to transfer power to the legitimate officials. They have also denied Braxton access to the town’s bank account, forcing him to run food distribution drives and otherwise carry out his mayoral duties using his own funds.

In the lawsuit, the plaintiffs are asking the court to install Braxton as the town’s rightful mayor. “Allowing the Defendants to continue their hand-me-down governance violates the basic tenets of democracy and state law,” they write. In the meantime, they say, Stokes is ignoring basic requests from his Black constituents: Although their homes occasionally flood with raw sewage, he’s refused to support the installation of a proper sewage system.

The simple request in this case—can we have a local election, please?—is a far cry from the triumphant asks being made by conservative legal movement lawyers in federal courtrooms across the country. Over the past several years, a single Trump-appointed federal judge in Texas has signed off on requests to reverse the Food and Drug Administration’s decades-old approval of drugs used in medication abortion; to force President Joe Biden to reinstate Trump-era immigration policies; and to gut a federal program that provides free contraceptive access to anyone who wants it.

Many of these exercises in judicial policymaking have come in the form of nationwide injunctions, which spiked during the Biden administration as Trump judges began wielding their power to implement the former president’s agenda by judicial fiat. During a Supreme Court oral argument last month, Justice Neil Gorsuch observed that judges issued “exactly zero universal injunctions” during President Franklin Roosevelt’s 12 years in office. “Over the last four years or so, the number is something like 60,” he said. Given that conservative judges in Texas recently declined to adopt rules that would have limited conservative activists’ ability to hand-pick judges, it seems unlikely that this trend reverses anytime soon.

The Newbern case lays bare the impact of the Republican Party’s generations-long effort to capture the judiciary. When the federal bench is this stacked with friendly faces, the conservative legal movement is free to run up the score. Everyone else is just hoping to get on the playing field.

#us politics#news#balls and strikes#2024#republicans#conservatives#newbern#alabama#Voting Rights Act#racists#racism#municipal elections#abc news#videos#Patrick Braxton#Haywood “Woody” Stokes III#conservative legal movement#Youtube#1965

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

NEWBERN, Ala. — There’s a power struggle in Newbern, Alabama, and the rural town’s first Black mayor is at war with the previous administration who he says locked him out of Town Hall.

After years of racist harassment and intimidation, Patrick Braxton is fed up, and in a federal civil rights lawsuit he is accusing town officials of conspiring to deny his civil rights and his position because of his race.

“When I first became mayor, [a white woman told me] the town was not ready for a Black mayor,” Braxton recalls.

The town is 85% Black, and 29% of Black people here live below the poverty line.

“What did she mean by the town wasn’t ready for a Black mayor? They, meaning white people?” Capital B asked.

“Yes. No change,” Braxton says.

Decades removed from a seemingly Jim Crow South, white people continue to thwart Black political progress by refusing to allow them to govern themselves or participate in the country’s democracy, several residents told Capital B. While litigation may take months or years to resolve, Braxton and community members are working to organize voter education, registration, and transportation ahead of the 2024 general election.

But the tension has been brewing for years.

Two years ago, Braxton says he was the only volunteer firefighter in his department to respond to a tree fire near a Black person’s home in the town of 275 people. As Braxton, 57, actively worked to put out the fire, he says, one of his white colleagues tried to take the keys to his fire truck to keep him from using it.

In another incident, Braxton, who was off duty at the time, overheard an emergency dispatch call for a Black woman experiencing a heart attack. He drove to the fire station to retrieve the automated external defibrillator, or AED machine, but the locks were changed, so he couldn’t get into the facility. He raced back to his house, grabbed his personal machine, and drove over to the house, but he didn’t make it in time to save her. Braxton wasn’t able to gain access to the building or equipment until the Hale County Emergency Management Agency director intervened, the lawsuit said.

“I have been on several house fires by myself,” Braxton says. “They hear the radio and wouldn’t come. I know they hear it because I called dispatch, and dispatch set the tone call three or four times for Newbern because we got a certain tone.”

Not only has he been locked out of the town hall and fought fires alone, but he’s been followed by a drone and unable to retrieve the town’s mail and financial accounts, he says. Rather than concede, Haywood “Woody” Stokes III, the former white mayor, along with his council members, reappointed themselves to their positions after ordering a special election that no one knew about.

Braxton is suing them, the People’s Bank of Greensboro, and the postmaster at the U.S. Post Office.

For at least 60 years, there’s never been an election in the town. Instead, the mantle has been treated as a “hand me down” by the small percentage of white residents, according to several residents Capital B interviewed. After being the only one to submit qualifying paperwork and statement of economic interests, Braxton became the mayor.

Stokes and his council — which consists of three white people (Gary Broussard, Jesse Leverett, Willie Tucker) and one Black person (Voncille Brown Thomas) — deny any wrongdoing in their response to the amended complaint filed on April 17. They also claim qualified immunity, which protects state and local officials from individual liability from civil lawsuits.

The attorneys for all parties, including the previous town council, the bank, and Lynn Thiebe, the postmaster at the post office, did not respond to requests for comment.

The town where voting never was

Over the past 50 years, Newbern has held a majority Black population. The town was incorporated in 1854 and became known as a farm town. The Great Depression and the mechanization of the cotton industry contributed to Newbern’s economic and population decline, according to the Encyclopedia of Alabama.

Today, across Newbern’s 1.2 square miles sits the town hall and volunteer fire department constructed by Auburn’s students, an aging library, U.S. Post Office, and Mercantile, the only store there, which Black people seldom frequent because of high prices and a lack of variety of products, Braxton says.

“They want to know why Black [people] don’t shop with them. You don’t have nothin’ the Black [people] want or need,” he says. “No gasoline. … They used to sell country-time bacon and cheese and souse meat. They stopped selling that because they say they didn’t like how it feel on their hands when they cuttin’ the meat.”

To help unify the town, Braxton began hosting annual Halloween parties for the children, and game day for the senior citizens. But his efforts haven’t been enough to stop some people from moving for better jobs, industry, and quality of life.

Residents say the white town leaders have done little to help the predominantly Black area thrive over the years. They question how the town has spent its finances, as Black residents continue to struggle. Under the American Rescue Plan Act, Newbern received $30,000, according to an estimated funding sheet by Alabama Democratic U.S. Rep. Terri Sewell, but residents say they can’t see where it has gone.

At the First Baptist Church of Newbern, Braxton, three of his selected council members — Janice Quarles, 72, Barbara Patrick, 78, and James Ballard, 76 — and the Rev. James Williams, 77, could only remember two former mayors: Robert Walthall, who served as mayor for 44 years, and Paul Owens, who served on the council for 33 years and mayor for 11.

“At one point, we didn’t even know who the mayor was,” Ballard recalls. “If you knew somebody and you was white, and your grandfather was in office when he died or got sick, he passed it on down to the grandson or son, and it’s been that way throughout the history of Newbern.”

Quarles agreed, adding: “It took me a while to know that Mr. Owens was the mayor. I just thought he was just a little man cleaning up on the side of the road, sometimes picking up paper. I didn’t know until I was told that ‘Well, he’s the mayor now.’”

Braxton mentioned he heard of a Black man named Mr. Hicks who previously sought office years ago.

“This was before my time, but I heard Mr. Hicks had won the mayor seat and they took it from him the next day [or] the next night,” Braxton said. “It was another Black guy, had won years ago, and they took it from.”

“I hadn’t heard that one,” Ballard chimes in, sitting a few seats away from Braxton.

“How does someone take the seat from him, if he won?” Capital B asked.

“The same way they’re trying to do now with Mayor Braxton,” Quarles chuckled. “Maybe at that time — I know if it was Mr. Hicks — he really had nobody else to stand up with him.”

Despite the rumor, what they did know for sure: There was never an election, and Stokes had been in office since 2008.

The costs to challenging the white power structure

After years of disinvestment, Braxton’s frustrations mounted at the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, when he says Stokes refused to commemorate state holidays or hang up American flags. When the COVID-19 pandemic hit, the majority-white council failed to provide supplies such as disinfectant, masks, and humidifiers to residents to mitigate the risks of contracting the virus.

Instead of waiting, Braxton made several trips to neighboring Greensboro, about 10 miles away, to get food and other items to distribute to Black and white residents. He also placed signs around town about vaccination. He later found his signs had been destroyed and put in “a burn pile,” he said.

After years of unmet needs of the community, Braxton decided to qualify for mayor. Only one Black person — Brown Thomas, who served with Stokes —has ever been named to the council. After Braxton told Stokes, the acting mayor, his intention to run, the conspiracy began, the lawsuit states.

According to the lawsuit, Stokes gave Braxton the wrong information on how to qualify for mayor. Braxton then consulted with the Alabama Conference of Black Mayors, and the organization told him to file his statement of candidacy and statement of the economic interests with the circuit clerk of Hale County and online with the state, the lawsuit states. Vickie Moore, the organization’s executive director, said it also guided Braxton on how to prepare for his first meeting and other mayoral duties.

Moore, an Alabama native and former mayor of Slocomb, said she has never heard of other cases across the state where elected officials who have never been elected are able to serve. This case with Braxton is “racism,” she said.

“The true value of a person can’t be judged by the color of their skin, and that’s what’s happening in this case here, and it’s the worst racism I’ve ever seen,” Moore said. “We have fought so hard for simple rights. It’s one of the most discouraging but encouraging things because it encourages us to continue to move forward … and continue to fight.”

Political and legal experts say what’s happening in Newbern is rare, but the tactics to suppress Black power aren’t, especially across the South. From tampering with ballot boxes to restricting reading material, “the South has been resistant to all types of changes” said Emmitt Riley III, associate professor of political science and Africana Studies at The University of the South.

“This is a clear case of white [people] attempting to seize and maintain political power in the face of someone who went through the appropriate steps to qualify and to run for office and by default wins because no one else qualified,” Riley added. “This raises a number of questions about democracy and a free and fair system of governance.”

Riley mentioned a different, but similar case in rural Greenwood, Mississippi. Sheriel Perkins, a longtime City Council member, became the first Black female mayor in 2006, serving for only two years. She ran again in 2013 and lost by 206 votes to incumbent Carolyn McAdams, who is white. Perkins contested the results, alleging voter fraud. White people allegedly paid other white people to live in the city in order to participate in the election and cast a legal vote, Riley said. In that case, the state Supreme Court dismissed the case and “found Perkins presented no evidence” that anyone voted illegally in a precinct, but rather it was the election materials that ended up in the wrong precincts.

“It was also on record that one white woman got on the witness stand and said, ‘I came back to vote because I was contacted to vote by X person.’ I think you see these tactics happening all across the South in local elections, in particular,” Riley said. “It becomes really difficult for people to really litigate these cases because in many cases it goes before the state courts, and state courts have not been really welcoming to overturning elections and ordering new elections.”

Another example: Camilla, Georgia.

In 2015, Rufus Davis was elected as the first Black male mayor of rural, predominantly Black Camilla. In 2017, the six-person City Council — half Black and half white — voted to deny him a set of keys to City Hall, which includes his office. Davis claimed the white city manager, Bennett Adams, had been keeping him from carrying out his mayoral duties.

The next year, Davis, along with Black City Council member Venterra Pollard, boycotted the city’s meetings because of “discrimination within the city government,” he told a local news outlet. Some of the claims included the absence of Black officers in the police department, and the city’s segregated cemetery, where Black people cannot be buried next to white people. (The wire fence that divided the cemetery was taken down in 2018). In 2018, some citizens of the small town of about 5,000 people wanted to remove Davis from office and circulated a petition that garnered about 200 signatures. In 2019, he did not seek re-election for office.

“You’re not the mayor”

After being the only person to qualify and submit proper paperwork for any municipal office, Braxton became mayor-elect and the first Black mayor in Newbern’s history on July 22, 2020.

Following the announcement, Braxton appointed members to join his council, consistent with the practice of previous leadership. He asked both white and Black people to serve, he said, but the white people told him they didn’t want to get involved.

The next month, Stokes and the former council members, Broussard, Leverett, Brown Thomas, and Tucker, called a secret meeting to adopt an ordinance to conduct a special election on Oct. 6 because they “allegedly forgot to qualify as candidates,” according to the lawsuit, which also alleges the meeting was not publicized. The defendants deny this claim, but admit to filing statements of candidacy to be elected at the special election, according to their response to an amended complaint filed on their behalf.

Because Stokes and his council were the only ones to qualify for the Oct. 6 election, they reappointed themselves as the town council. On Nov. 2, 2020, Braxton and his council members were sworn into office and filed an oath of office with the county probate judge’s office. Ten days later, the city attorney’s office executed an oath of office for Stokes and his council.

After Braxton held his first town meeting in November, Stokes changed the locks to Town Hall to keep him and his council from accessing the building. For months, the two went back and forth on changing the locks until Braxton could no longer gain access. At some point, Braxton says he discovered all official town records had been removed or destroyed, except for a few boxes containing meeting minutes and other documents.

Braxton also was prevented from accessing the town’s financial records with the People’s Bank of Greensboro and the city clerk, and obtaining mail from the town’s post office. At every turn, he was met with a familiar answer: “You’re not the mayor.” Separately, he’s had drones following him to his home and mother’s home and had a white guy almost run him off the road, he says.

Braxton asserts he’s experienced these levels of harassment and intimidation to keep him from being the mayor, he said.

“Not having the Lord on your side, you woulda’ gave up,” he told Capital B.

‘Ready to fire away’

In the midst of the obstacles, Braxton kept pushing. He partnered with LaQuenna Lewis, founder of Love Is What Love Does, a Selma-based nonprofit focused on enriching the lives of disadvantaged people in Dallas, Perry, and Hale counties through such means as food distribution, youth programming, and help with utility bills. While meeting with Braxton, Lewis learned more about his case and became an investigator with her friend Leslie Sebastian, a former advocacy attorney based in California.

The three began reviewing thousands of documents from the few boxes Braxton found in Town Hall, reaching out to several lawyers and state lawmakers such as Sen. Bobby Singleton and organizations such as the Southern Poverty Law Center. No one wanted to help.

When the white residents learned Lewis was helping Braxton, she, too, began receiving threats early last year. She received handwritten notes in the mail with swastikas and derogatory names such as the n-word and b-word. One of theletters had a drawing of her and Braxton being lynched.

Another letter said they had been watching her at the food distribution site and hoped she and Braxton died. They also made reference to her children, she said. Lewis provided photos of the letters, but Capital B will not publish them. In October, Lewis and her children found their house burned to the ground. The cause was undetermined, but she thinks it may have been connected.

Lewis, Sebastian, and Braxton continued to look for attorneys that would take the case. Braxton filed a complaint in Alabama’s circuit court last November, but his attorney at the time stopped answering his calls. In January, they found a new attorney, Richard Rouco, who filed an amended complaint in federal court.

“He went through a total of five attorneys prior to me meeting them last year, and they pretty much took his money. We ran into some big law firms who were supposed to help and they kind of misled him,” Lewis says.

Right now, the lawsuit is in the early stages, Rouco says, and the two central issues of the case center on whether the previous council with Stokes were elected as they claim and if they gave proper notice.

Braxton and his team say they are committed to still doing the work in light of the lawsuit. Despite the obstacles, Braxton is running for mayor again in 2025. Through AlabamaLove.org, the group is raising money to provide voter education and registration, and address food security and youth programming. Additionally, they all hope they can finally bring their vision of a new Newbern to life.

For Braxton, it’s bringing grocery and convenience stores to the town. Quarles wants an educational and recreational center for children. Williams, the First Baptist Church minister, wants to build partnerships to secure grants in hopes of getting internet and more stores.

“I believe we done put a spark to the rocket, and it’s going [to get ready] to fire away,” Williams says at his church. “This rocket ready to fire away, and it’s been hovering too long.”

Correction: In Newbern, Alabama, 29% of the Black population lives below the poverty line. An earlier version of this story misstated the percentage

#alabama#Newbern Alabama#A Black Man Was Elected Mayor in Rural Alabama#but the White Town Leaders Won’t Let Him Serve#Patrick Braxton#AlabamaLove.org#black lives matter

372 notes

·

View notes

Text

Philip Lewis at HuffPost:

Residents in a small Alabama town will be able to vote in their own municipal elections for the first time in decades after a four-year legal battle. A proposed settlement has been reached in the town’s voting rights case, allowing Newbern, a predominantly Black town with 133 residents, to hold its first legitimate elections in more than 60 years. The town’s next elections will be held in 2025. The settlement was filed June 21 and must be approved by U.S. District Judge Kristi K. DuBose. For decades, white officials appointed Newbern’s mayor and council members in lieu of holding elections. Most residents weren’t even aware that there were supposed to be elections for these positions.

[...] The settlement will reinstate Patrick Braxton as the mayor of Newbern, the first Black person to hold the position in the town’s 170-year history. Capital B News had first reported about Braxton’s fight. Braxton was the only candidate who filed qualifying paperwork with the county clerk in 2020, so he won the mayoral race by default. The incumbent, Haywood “Woody” Stokes III, hadn’t even bothered to fill out the paperwork to run again. Haywood Stokes Jr., his father, had previously been mayor of the rural Black Belt town. After Braxton assumed office, he faced several obstacles. He discovered the locks to the town hall had been changed, and that the town council had held a secret special election in which they simply reelected themselves. They then reappointed Stokes III as mayor of Newbern in 2021. He has been acting as mayor ever since.

Newbern, Alabama will be set to hold elections for its municipal officers next year for the first time in over 60 years as a result of a proposed settlement over the majority-Black town's residents being deprived of their voting rights. This settlement also reinstates Patrick Braxton to the Mayor post.

#Newbern Alabama#Alabama#Patrick Braxton#Voting Rights#2025 Elections#2025 Mayoral Elections#Haywood Stokes III#NAACP Legal Defense Fund#NAACP

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

All Hallows - Pumpkin Acres

Moving clockwise around the entry plaza, the next gate from Trick-or-Treat Village leads to Pumpkin Acres, a tiny agricultural town somewhere in the American Midwest (or is it the South, or Appalachia, or...?) during the fall harvest season. The gateway is asymmetrical, with a white fence bordering a cornfield on one side and a small green bearing a painted wooden sign welcoming visitors to the town on the other. The base of the sign is heaped with fall produce—not only pumpkins, but baskets of apples and flint corn, squashes and gourds, and sheaves of wheat.

The walkway leads directly to the town square, which is designed in a typical “historic downtown” style, with buildings reflecting a countrified version of the architecture of the early 1900s. The colors tend toward earth tones with white trim, and some of the buildings are very obviously converted barns. Every storefront window display is decorated with simple jack-o-lanterns, autumn leaf garlands, and other seasonal accents.

Near the center of the square is an old-fashioned message board. Attentive guests can peruse the board to pick up on some of the area lore (see Characters, below).

On the far side of the square from the entry point is an open field in which a “Harvest Fair” has been set up, with a few simple carnival rides and game booths.

The “period setting” of Pumpkin Acres is wholly contemporary, but the town is a bit behind the times in many ways. Everything looks at least somewhat old, but carefully maintained to last. The ambient music loop consists of country-western, bluegrass, and blues music, some of it explicitly Halloween-themed while other tunes are merely dark and somber in tone.

Characters

The characters of Pumpkin Acres are just plain folks...or are they? The key players are as follows:

Granny McGillicuddy: By any measure the matriarch of the town, Granny is pushing 80 but still spry and working her pumpkin farm, which produces some real monsters every year—one just won the top prize at the County Fair and can be viewed on her property as part of the Pumpkin Acres Haunted Hayride. She also owns the town's biggest restaurant, although she leaves the running of it to younger relatives these days.

Harry Palmer: The local kook, who recently spent the night in the drunk tank for an unspecified offense (again). He runs the petting farm and loves his animals so much you might well suspect him of being one of them!

Woody Braxton: The young man who runs the bookshop (and the public library), Woody is a self-certified expert in cryptids and other paranormal mysteries. Not that he believes any of that stuff, mind you—he just finds it a fascinating topic!

Jeannie Braxton: Woody's younger sister (late teens/early 20s), who does believe that stuff and is constantly getting into mild scrapes trying to prove it's real.

Attractions

Harry Palmer's Petting Farm: Come on in and meet Harry's beloved animals! There's Elvira the black sheep, Beelzebub the Manx Loaghtan goat, Midnight the Ayam Cemani chicken, and quite a few regular critters as well. For a small fee, you can even feed them, and despite some of the nastier rumors in town, they do not eat the souls of the living.

Swamp Boats: One of the more peaceful rides in All Hallows, a simple outdoor boat ride through a swampy landscape. There's eerie mist, mysterious sounds from distant sources, and some of the trees look a little like threatening monsters, but there are no overt jump-scares or other frights—the horror here is whatever guests bring with them and project into their surroundings.

Pumpkin Acres Haunted Hayride: The signature attraction of Pumpkin Acres, a track-bound dark ride with “haycart” vehicles that seat about 30. The haycart travels past scenes of fields and wooded spots containing tableaux implied to be built by the town residents for the occasion. They start out benign (cute scarecrows posed with farm equipment, obviously fake graveyards with ghost and skeleton props), but as the ride progresses, the tableaux become eerier and evidence mounts that something genuinely supernatural is going on. The climax of the ride occurs in Granny McGillicuddy's field, when her prize pumpkin suddenly lifts up off the ground as the head of a massive spirit-possessed scarecrow!

Corn Maze: A traditional corn maze—just a winding path through the stalks, with a motion-activated bogeys in strategic locations. Of course, if real corn were used then the maze would only be available in the appropriate season, so the actual structure is artificial cornstalks backed up by painted fencing to give a similar visual impression.

The Pumpkin Acres Town Fair: This is the name given to a collection of small attractions at one end of the town. There are simple carnival rides, the sorts of things that can be folded up and transported via tractor-trailer: a Tilt-a-Whirl with seats that look like caramel apples (the stick is the backrest), a “Witch's Cauldron Bounce,” a miniature spook house, and a pony ride. There are also some equally simple carnival game booths and a small stage where guests can sit on bales of hay and enjoy a bluegrass band.

Shops and Eateries

6. Pumpkin Patch: During the fall, guests can get their pumpkins for carving right at the theme park! As with other unwieldy purchases, they can be reserved and paid for up front, and then picked up on the way out. Decorative gourds, flint corn, and other attractive fall produce items are also available.

7. Country Costumes: The Pumpkin Acres costume shop offers costumes based on a variety of rural and farm archetypes. Some of these include: Cowboy/cowgirl, farm animals of various types, farmer, fruits and vegetables, granny/grandpa, pumpkin, ragdoll, redneck, scarecrow (friendly and scary varieties), and werewolf.

8. Sewing & Craft Shop: On the other hand, guests might prefer to get the supplies to make their own costumes. Due to space limitations, the stock of fabrics is not as large as it would be in a standard fabric store, and the actual bolts are not kept on the sales floor but in a cutting room in the back, with guests making their selections based on sample swatches. Patterns, notions and Halloween-themed craft kits can be taken right off the shelves.

9. Braxton Books: A small bookshop focusing on paranormal subjects and horror novels. Includes a reading nook for those who want to peruse before buying.

10. Granny McGillicuddy's Pie Barn: A counter-service restaurant with country-style cooking—fried chicken and chicken-fried steak, mashed potatoes, biscuits and gravy, and several flavors of pie, including pumpkin, apple, and boysenberry. Steamed vegetables and other less-heavy dishes round out the menu. Beverages include the standard array of soft drinks, bottled beer (limit one per customer), and hot apple cider.

Other

The back corner (on the right side, from the perspective of someone heading in from the entry plaza) of Pumpkin Acres is thickly planted with trees and shrubs, with a path that ultimately leads into Goblin Woods. (Marked on the map with a *.)

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Black Man Was Elected Mayor in Rural Alabama, but the White Town Leaders Won’t Let Him Serve

"When I first became mayor, [a white woman told me] the town was not ready for a Black mayor," Braxton recalls. The town is 85% Black, and 69% of Black people here live below the poverty line. "What did she mean by the town wasn't ready for a Black mayor? They, meaning white people?" Capital B asked. "Yes. No change," Braxton says.

Two years ago, Braxton says he was the only volunteer firefighter in his department to respond to a tree fire near a Black person's home in the town of 275 people. As Braxton, 57, actively worked to put out the fire, he says, one of his white colleagues tried to take the keys to his fire truck to keep him from using it. In another incident, Braxton, who was off duty at the time, overheard an emergency dispatch call for a Black woman experiencing a heart attack. He drove to the fire station to retrieve the automated external defibrillator, or AED machine, but the locks were changed, so he couldn't get into the facility. He raced back to his house, grabbed his personal machine, and drove over to the house, but he didn't make it in time to save her. Braxton wasn't able to gain access to the building or equipment until the Hale County Emergency Management Agency director intervened, the lawsuit said. "I have been on several house fires by myself," Braxton says. "They hear the radio and wouldn't come. I know they hear it because I called dispatch, and dispatch set the tone call three or four times for Newbern because we got a certain tone."

Not only has he been locked out of the town hall and fought fires alone, but he's been followed by a drone and unable to retrieve the town's mail and financial accounts, he says. Rather than concede, Haywood "Woody" Stokes III, the former white mayor, along with his council members, reappointed themselves to their positions after ordering a special election that no one knew about. Braxton is suing them, the People's Bank of Greensboro, and the postmaster at the U.S. Post Office. For at least 60 years, there's never been an election in the town. Instead, the mantle has been treated as a "hand me down" by the small percentage of white residents, according to several residents Capital B interviewed. After being the only one to submit qualifying paperwork and statement of economic interests, Braxton became the mayor.

#Racism#Alabama#Patrick Braxton#Can't believe this is happening in 2023#Disgusting shit#Sounds like a Sundown town#How is this legal?

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Not only has he been locked out of the town hall and fought fires alone, but he’s been followed by a drone and unable to retrieve the town’s mail and financial accounts, he says. Rather than concede, Haywood “Woody” Stokes III, the former white mayor, along with his council members, reappointed themselves to their positions after ordering a special election that no one knew about."

This is wildly anti-constitutional.

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Merlin Santana (March 14, 1976 – November 9, 2002) was an American actor and rapper. Beginning his career in the early 1990s, Santana was best known for his roles as Rudy Huxtable's boyfriend Stanley on The Cosby Show, Marcus Dixon on Getting By, Marcus Henry in Under One Roof and Romeo Santana on The WB sitcom The Steve Harvey Show (1996 – 2002).

Born in Upper Manhattan, New York City to parents from the Dominican Republic, Santana's career in show business began with a push from his parents, who wanted to keep him off the tough streets of New York. He began his career at the age of three as an advertising model for a fast food chain. His first screen appearance was as an extra in the Woody Allen film, The Purple Rose of Cairo.

Acting Career

In 1991, Santana landed a recurring role on The Cosby Show as Stanley, the boyfriend of Rudy Huxtable and the rival of Rudy's friend Kenny (Deon Richmond). He was then cast as Marcus Dixon in the short-lived sitcom, Getting By, starring Cindy Williams and Telma Hopkins. Deon Richmond was cast as his brother Darren, due to their interaction on The Cosby Show.

In November 1994, Santana appeared on Sister, Sister as Joey, who falls in love with Tia and Tamera (Tia and Tamera Mowry) at Rocket Burger.

In 1995, Santana was cast as Marcus Henry in the short-lived CBS family drama Under One Roof, co-starring with James Earl Jones, Joe Morton and Vanessa Bell Calloway. Between 1996 and 1999, he played the role of Ohagi on Moesha.

In 1996, he landed the role of Romeo Santana on The Steve Harvey Show. In 2001, he played the role of Jermaine in the movie Flossin. In 2002, he appeared in the VH1 TV movie, Play'd: A Hip Hop Story with Toni Braxton. That same year, Santana had a role in the Eddie Murphy comedy Showtime. His last television acting role was on the UPN series, Half & Half, while his last film role was in the 2003 comedy film, The Blues with Deon Richmond.

Death

Shooting

On November 9, 2002, Santana was murdered while sitting in a car in Los Angeles. Santana and his friend, actor Brandon Adams, just left an acquaintance's home in the Crenshaw District when the suspect Damien Andre Gates fired the shot that entered through the trunk of the vehicle in which Santana was a passenger. The bullet penetrated the right-front passenger headrest and entered Santana's head, killing him.

On November 18, 2002, Santana, age 26, was buried at Saint Raymond's Cemetery in The Bronx borough of New York City.

Trial and Allegations against Gates

In 2003, Gates was convicted of the first-degree murder of Santana and the attempted murder of Adams and was sentenced to three consecutive life sentences plus 70 years in prison.

Brandon Douglas Bynes, the other suspect who was with Gates during the shooting, received a 23-year sentence after pleading guilty to voluntary manslaughter and assault with a deadly weapon.

An LAPD officer involved in the case testified that Monique King, reportedly shooter Gates's girlfriend, only aged 15 at the time, falsely claimed that Santana made sexual advances towards her which prompted the Gates' and Bynes' attack.

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Newbern is a Black-majority town in rural Alabama that, according to residents, has never had an election. Patrick Braxton ran to become its first Black mayor in 2020. With no opponent, he ascended into the office by default, but you’d never know it. The previous mayor, Haywood "Woody" Stokes III, is still serving as mayor, despite the fact that he failed to submit the necessary paperwork to even run for the role. Before Braxton, the position of mayor in this town had always been passed down from white friend to white friend.

-----

This gets even crazier the more you read.AL has refused to do anything about this. The DOJ needs to step in. How to contact them.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Residents in a small Alabama town will be able to vote in their own municipal elections for the first time in decades after a four-year legal battle.

A proposed settlement has been reached in the town’s voting rights case, allowing Newbern, a predominantly Black town with 133 residents, to hold its first legitimate elections in more than 60 years. The town’s next elections will be held in 2025.

. . .For decades, white officials appointed Newbern’s mayor and council members in lieu of holding elections. Most residents weren’t even aware that there were supposed to be elections for these positions.

. . .[Patrick] Braxton was the only candidate who filed qualifying paperwork with the county clerk in 2020, so he won the mayoral race by default. The incumbent, Haywood “Woody” Stokes III, hadn’t even bothered to fill out the paperwork to run again. Haywood Stokes Jr., his father, had previously been mayor of the rural Black Belt town.

After Braxton assumed office, he faced several obstacles. He discovered the locks to the town hall had been changed, and that the town council had held a secret special election in which they simply reelected themselves. They then reappointed Stokes III as mayor of Newbern in 2021. He has been acting as mayor ever since.

. . .Braxton, who was born in Newbern and described himself as a “handyman for the community,” hasn’t been able to access town funds since Stokes was appointed as mayor four years ago. He has used his own money to provide residents with COVID-19 supplies, as well as to host food drives and other events, according to The Guardian.

#civil rights#alabama#what the ever living fuck#feudalism alive and well in alabama#which is somewhat unsurprising#but jfc#braxton is a fucking champ#but how enraging that he's had to be

0 notes

Text

LÉGENDES DU JAZZ

CECIL McBEE, MAITRE DE LA CONTREBASSE

Né le 19 mai 1935 à Tulsa, en Oklahoma, Cecil McBee a d’abord étudié la clarinette à l’école et s’était produit avec plusieurs groupes scolaires. Avec sa soeur Shirley, McBee était devenu une grande vedette locale en se produisant dans des duos de clarinette à travers l’État. McBee était passé à la contrebasse à l’âge de dix-sept ans et s’était rapidement produit dans des clubs locaux de jazz et de rhythm & blues.

En raison de sa virtuosité comme clarinettiste, McBee s’était mérité une bourse pour étudier à la Central State University de Wilberforce, en Ohio, mais ses études avaient été interrompues lorsqu’il avait été mobilisé dans l’armée. Comme militaire, McBee avait dirigé durant deux ans le “158th Band” de la base de Fort Knox, au Kentucky. Lors de son séjour dans l’armée, McBee en avait profité pour étudier la composition et l’improvisation.

Une fois démobilisé, McBee avait repris ses études à l’Ohio State University, où il avait obtenu un baccalauréat en musique. McBee, qui avait d’abord eu l’intention de devenir professeur, avait réalisé après avoir obtenu son diplôme qu’il était davantage intéressé par une carrière de musicien de jazz.

Après avoir accompagné la chanteuse Dinah Washington en 1959, McBee s’était installé à Detroit trois ans plus tard, où il avait travaillé avec le sextet de Paul Winter de 1963 à 1964. Dès son arrivée à New York en 1964, McBee était devenu un des contrebassistes les plus en demande du monde du jazz, enregistrant et voyageant autour du monde avec des sommités comme Charles Lloyd, Pharoah Sanders, Elvin Jones, McCoy Tyner, Miles Davis, Bobby Hutcherson, Keith Jarrett, Wayne Shorter (1965-1966), Freddie Hubbard, Sonny Rollins, Joe Henderson, Andrew Hill, Sam Rivers, Michael White, Jackie McLean (1964), Yusef Lateef (1967–1969), Alice Coltrane, Ravi Coltrane, Abdullah Ibrahim, Lonnie Liston Smith, Buddy Tate, Joanne Brackeen, Dinah Washington, Benny Goodman, George Benson, Nancy Wilson, Betty Carter, Art Pepper, Pharoah Sanders, Dave Liebman, Joe Lovano, Billy Hart, Eddie Henderson, Yosuke Yamashita, Billy Harper et Geri Allen.

En 1966, McBee s’était joint au groupe du saxophoniste Charles Lloyd aux côtés de Keith Jarrett et Jack DeJohnette. Il avait ensuite enregistré et fait des tournées avec des grands noms du jazz comme Miles Davis, Yusef Lateef, Pharoah Sanders, Archie Shepp, Freddie Hubbard, Woody Shaw, Alice Coltrane (1969-72), McCoy Tyner, Mal Waldron, Kenny Barron, Joanne Brackeen, Abdullah Ibrahim, Art Pepper, Anthony Braxton, Elvin Jones, Clifford Jordan, Chet Baker et Johnny Griffin. Au cours de cette période, McBee avait aussi enregistré sept albums comme leader de ses propres groupes. En 1986, McBee avait également joué avec Freddie Hubbard et Woody Shaw.

En 1988, McBee avait participé à un album-hommage à John Coltrane intitulé ‘’Blues for Coltrane’’, dans le cadre d’un sextet qui comprenait Pharoah Sanders, McCoy Tyner, David Murray, McCoy Tyner et Roy Haynes. L’album s’était d’ailleurs mérité un prix Grammy dans la catégorie de la meilleure performance instrumentale par un individu ou un groupe. Dans le cadre de ses enregistrements et de ses tournées, McBee, qui avait obtenu deux bourses de la National Endowment for the Arts (NEA), avait également interprété ses propres compositions. L’album de Charles Lloyd ‘’Forest Flower’’ (1966) comprenait d’ailleurs une ballade de McBee intitulée “Song of Her” qui était devenue un standard du jazz. Plusieurs des compositions de McBee avaient aussi été enregistrées par d’autres musiciens, dont Elvin Jones, McCoy Tyner, Pharoah Sanders et plusieurs autres. Parmi les plus célèbres compositions de McBee, on remarquait “Wilpan’s”, “Peacemaker”, “Slippin’n Slidin’”, “Blues on the Bottom”, “Consequence” et “Close to You Alone.”

Avec le batteur Billy Hart, McBee avait également formé le noyau de la section rythmique de deux groupes majeurs, Saxophone Summit et The Cookers, dans lesquels il avait interprété plusieurs autres de ses compositions. Dans les années 2000, McBee a poursuivi avec succès une compagnie japonaise qui avait ouvert une chaîne de magasins sous son nom sans son autorisation.

Également professeur, McBee avait donné des cours privés et enseigné durant près de quatre décennies dans différents collèges et universités renommés, dont le New England Conservatory de Boston où il avait enseigné durant plus de vingt-cinq ans. McBee avait aussi occupé un poste d’artiste en résidence à l’Université Harvard de 2010 à 2011. Durant cette période, McBee en avait profité pour améliorer ses techniques d’enseignement et travaillé sur un manuel d’instruction novateur pour la contrebasse. Caractérisée par son approche révolutionnaire, la méthode de McBee pouvait également être appliquée aux méthodes d’improvisation de plusieurs autres catégories d’instruments. Reconnu pour sa virtuosité et son style très personnel, McBee a été intronisé en 1991 au sein du Oklahoma Jazz Hall of Fame.

Compositeur émérite, McBee a participé à des centaines d’enregistrements au cours de sa carrière.

©-2024, tous droits réservés, Les Productions de l’Imaginaire historique

SOURCES:

‘’Cecil McBee.’’ Wikipedia, 2023.

‘’Cecil McBee.’’ All About Jazz, 2023.

0 notes

Text

The white mayor of a tiny Alabama town less than an hour from Selma has argued he should be immune from a civil rights lawsuit, claiming that holding a secret meeting to keep the city’s first-ever Black mayor and five Black city council members out of office is not a sufficiently clear violation of constitutional rights.

Patrick Braxton, along with James Ballard, Barbara Patrick, Janice Quarles, and Wanda Scott, sued the city of Newbern, Alabama and alleged that despite being legally entitled to take office, they were prevented from doing so when white residents “refused to accept” the results of a 2020 election. They argue that Haywood “Woody” Stokes III, Newbern’s white former mayor, conspired with his council, other government officials, and a local bank, to illegally install himself as mayor even after Braxton fairly and legally won the election.

0 notes

Text

( ❋ && closed starter @thatbraxtondude

“ i fuckin’ saw it , brax !! it was right there . don’t move , “ woody hissed , baseball bat in hand , staring at absolutely nothing in the guttering of the street they found themselves roaming in the darkness . don’t ask how he acquired such a weapon – the male wasn’t quite sure either . atlanta wasn’t the cleanest of places ( especially in his usual hangouts ) and he swore he’d seen a rat scuttle across the ground , or maybe it was just the heavy drug use causing him to hallucinate vermin crawling across the ground like some sick fantasy . “ i hate those fuckin’ things with their little feet and those cock-shaped tails . disgusting . get it the hell outta here , it’s gonna steal all my stash . “

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Newbern, Ala., is not the proverbial one-redlight town. The flashing yellow light in front of the old post office merely warns folks to slow down. With a population of about 200, it’s an easy place to miss even when you drive right through it.

If you kept to the speed limit, you could pass from one end to the other in a couple of minutes. If you were a little less cautious, you might make it in one. Earlier this year, though, I stopped.

By the side of the road, I pulled out my phone to call the man I’d arranged to meet, but before I could retrieve his number, a black GMC pickup truck pulled up next to me and the driver waved.

“When I saw that Jefferson County license plate, I knew that had to be you,” Patrick Braxton shouted through his open window.

That’s how small Newbern is.

Braxton, who is Black, is one of two men who claim to be mayor here. The other, Woody Stokes, is white. Eights folks lay claim to the city’s four council seats.

Now control of Newbern town government is at the center of a lawsuit in federal court alleging blatant disfranchisement — a case that focuses, not on control of Congress or the delegates to the Electoral College, but over who gets their roads paved when there’s money for it and their ditches cleared after storms.

What also makes this an odd place for an election law case is that, as far back as anyone can remember, Newbern has never had an election.

Instead, the mayor and council have acted as a sort of self-appointing board. Stokes’ full name is Haywood Stokes III, who inherited the job from Haywood Stokes Jr. Likewise, other officials have passed control to new people after incumbents moved away, retired or died. The town is about 80 percent Black but most of these officials have been white.

And that has been how this town has worked, at least until Braxton qualified to run for office.

Small-town politics isn't like the pitched partisan battles on the national stages. In a town of about 200 people, everyone knows everyone else. A tour around town in Patrick Braxton's pickup truck takes less than 30 minutes.

Braxton, a contractor and volunteer firefighter, has spent most of his life living either near or in Newbern. A few years back, he had the idea to put up some American flags around town for the 4th of July. Town officials seemed indifferent, he says. Braxton scratched together the money to do it anyway, and folks seemed to like them, he says. It was then he had the idea to run for mayor.

Ahead of qualifying to run, Braxton learned what sort of paperwork he’d have to fill out and the deadlines for filing with the town clerk. But when he approached the incumbent, Stokes, for the forms, he started to run into problems. According to Braxton, Stokes told him Newbern didn’t have elections.

“His words to me were, ‘We don’t have no ballots and we don’t have no voting machines,’” Braxton recalls.

I called Stokes to get his side of this story and left messages, but those calls have not been returned. A lawyer for Stokes and the council members allied with him, Rick Howard, told me they would not comment on pending litigation and deferred to what was already in the court record.

Court records show that much of what Braxton says about the election is uncontested.

Stokes told Braxton he would have to fill out qualifying papers from the town clerk. Neither Stokes nor the clerk made it easy, but after trips back and forth between Newbern, the Hale County Probate Court in Greensboro and the bank where the clerk worked, Braxton managed to get the paperwork taken care of and a cashier’s check cut for his qualifying fee.

Meanwhile, Stokes doesn’t seem to have done any of those things. When election day came, Braxton was the only candidate to qualify and was named the new mayor.

It’s what happened next where the accounts begin to diverge somewhat.

Not only had Stokes not qualified, but neither had any of the incumbent city council members. Under Alabama law, the mayor gets to fill vacancies by appointment. Braxton recruited some folks he knew who were interested, and when the day came for him to take the oath of office, the county circuit judge swore in Braxton and what we’ll call Braxton’s council together.

Little did they know, the lame duck mayor, Stokes, and the incumbent council members had done something peculiar — they had held a special-called election without Braxton and the Braxton council knowing about it.

Here’s what the Stokes side would have you believe, according to their court filings: In a town of about 200 people and all 1.5 square miles of it, a place so small that Braxton found me within seconds after I got there — the Stokes council voted, posted notice, and opened qualifying for a special council election. Not only a special election but the first election this town seems to have ever had.

The Auburn University Rural Studio calls Newbern, Ala., home, too, and built the town a modern fire station and town hall. But the town hall has gone unused since a fight for power began over who's the town's rightful mayor, and Braxton says the fire department has responded to emergencies at white homes more readily than at Black ones.

All without Braxton or his future council appointees hearing about it.

Only the incumbent council members qualified and so they declared themselves the winners.

The Stokes council and the Braxton council both claim to be the rightful council members. At first, both councils recognized Braxton as the real mayor, although that would change, too.

Braxton wouldn’t meet with the Stokes council, as doing so would lend it legitimacy. The Stokes council declared Braxton AWOL and his office vacant. The Stokes council then re-named Stokes the interim mayor.

Which brings us to two mayors and eight council members in a town of less than 200 people — all without anyone having voted for any of them.

After the non-election election, Braxton says, strange things began to happen. One day he was run off the road. He says his wife began to notice drones following them around town, which he thought was crazy, until he saw them, too.

Braxton has tried to get access to the city’s bank accounts, but the bank denied him access. The same thing happened at the post office, he says. He has named both as defendants in the lawsuit.

Braxton says he won’t be deterred. He’ll run for office in the next election cycle if he has to, but he’d rather resolve this fight before then, in federal court.

Small-town power struggles aren’t as great as big-city politics, or pitched battles for national power — in some ways, they are much more intense. These aren’t political parties warring with faceless others, but neighbors at odds with neighbors, people they have known all their lives. It’s personal.

It takes less than half an hour for Braxton to give me a full tour of the town in his truck. He showed me where he lives and the homes of the other folks involved, before making our way back to town hall. Until recently, the most notable thing here has been Auburn University’s Rural Studio, an off-campus architecture school focused on sustainable design for out-of-the-way places. It’s the reason the post office looks like something from a movie set and the town hall and fire station something from a mountain tourist town, not the poverty-stricken Black Belt.

Since the last “election,” each side of the Newbern power struggle has changed the locks only to find the locks somehow changed on them — a bizarre war of wills that both sides now seem to have given up. The bespoke space for civic life sits mostly empty but for the dirt dobbers and spider webs taking over.

Between the town hall and the fire station is a barbecue pit and a small yard meant for community gatherings, only there aren’t any picnic tables or park benches. I point out the omission to which Braxton who chuckles grimly and then sighs.

“There’s no place here for people to come together,” he says.

#newbern alabama#A fight for rights and control in a Black Belt town without elections#Black Politics Matters#Patrick Braxton#white supremacy#white racism#systemic racism#homegrown terrorism

0 notes

Photo

BET Awards 2017 performers

#bet awards#bet awards 2017#betawards#chris brown#bruno mars#tamar braxton#xcape#migos#new edition#algee smith#keith powers#yazz the greatest#luke james#woody mcclain#mary j blige#maxwell#future#kendrick lamar#french montana#big sean#dj khaled#asahd khaled#chance the rapper#sza#lil wayne#khalid

260 notes

·

View notes