#wolof

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Youssou N'Dour and Neneh Cherry - 7 Seconds 1994

Youssou N'Dour is a Senegalese singer, songwriter, musician, composer, occasional actor, businessman, and politician. From April 2012 to September 2013, he was Senegal's Minister of Tourism. N'Dour helped develop a style of popular Senegalese music known by all Senegambians (including the Wolof) as mbalax, a genre that has sacred origins in the Serer music njuup tradition and ndut initiation ceremonies. He is the subject of the award-winning films Return to Gorée (2007) directed by Pierre-Yves Borgeaud and Youssou N'Dour: I Bring What I Love (2008) directed by Elizabeth Chai Vasarhelyi. In 2006, N'Dour was cast as Olaudah Equiano in the film Amazing Grace.

"7 Seconds" is a song N'Dour wrote and performed together with Swedish-Sierra Leonean singer-songwriter Neneh Cherry. The song is trilingual as N'Dour sings in three languages: French, English and the West African language Wolof. The title and refrain of the song refers to the first moments of a child's life; as Cherry put it, "not knowing about the problems and violence in our world". N'Dour featured the song on his seventh studio album, The Guide (Wommat) (1994), while Cherry included it on her 1996 album Man.

It was a worldwide hit, peaking within the top 10 of the charts in several countries, including Australia, Austria, Belgium, Brazil, Germany, Ireland, the Netherlands, Sweden, Paraguay and the UK. It climbed to the top position in Finland, France, Iceland, Italy and Switzerland. It stayed at number one for 16 consecutive weeks on the French Singles Chart, which was the record for the most weeks at the top position at the time. On the Eurochart Hot 100, the song reached number two. It won the MTV Europe Music Award in the category for Best Song of 1994.

"7 Seconds" received a total of 45,3% yes votes. :'(

youtube

#finished#sweblr#high no#low yes#low reblog#90s#youssou n'dour#neneh cherry#wolof#english#french#o4#lo3

527 notes

·

View notes

Text

.....

yall what the fuck was sausage saying, cuz I cannot imagine this is correct?

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

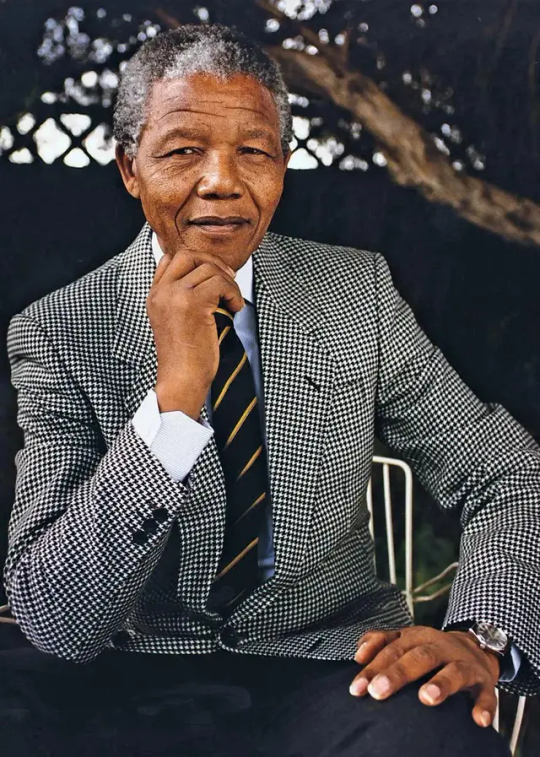

Wolof leader from Senegal

French vintage postcard

#senegal#sepia#photography#vintage#postkaart#ansichtskarte#ephemera#carte postale#postcard#postal#briefkaart#leader#photo#tarjeta#historic#french#postkarte#wolof

71 notes

·

View notes

Text

Blues has evolved from the unaccompanied vocal music and oral traditions of slaves imported from West Africa and rural Africans into a wide variety of styles and subgenres, with regional variations across the United States. Although blues (as it is now known) can be seen as a musical style based on both European harmonic structure and the African call-and-response tradition that transformed into an interplay of voice and guitar, the blues form itself bears no resemblance to the melodic styles of the West African griots. Additionally, there are theories that the four-beats-per-measure structure of the blues might have its origins in the Native American tradition of pow wow drumming. Some scholars identify strong influences on the blues from the melodic structures of certain West African musical styles of the savanna and sahel. Lucy Durran finds similarities with the melodies of the Bambara people, and to a lesser degree, the Soninke people and Wolof people, but not as much of the Mandinka people. Gerard Kubik finds similarities to the melodic styles of both the west African savanna and central Africa, both of which were sources of enslaved people.

No specific African musical form can be identified as the single direct ancestor of the blues. However the call-and-response format can be traced back to the music of Africa. That blue notes predate their use in blues and have an African origin is attested to by "A Negro Love Song", by the English composer Samuel Coleridge-Taylor, from his African Suite for Piano, written in 1898, which contains blue third and seventh notes.

The Diddley bow (a homemade one-stringed instrument found in parts of the American South sometimes referred to as a jitterbug or a one-string in the early twentieth century) and the banjo are African-derived instruments that may have helped in the transfer of African performance techniques into the early blues instrumental vocabulary. The banjo seems to be directly imported from West African music. It is similar to the musical instrument that griots and other Africans such as the Igbo played (called halam or akonting by African peoples such as the Wolof, Fula and Mandinka). However, in the 1920s, when country blues began to be recorded, the use of the banjo in blues music was quite marginal and limited to individuals such as Papa Charlie Jackson and later Gus Cannon.

Blues music also adopted elements from the "Ethiopian airs", minstrel shows and Negro spirituals, including instrumental and harmonic accompaniment. The style also was closely related to ragtime, which developed at about the same time, though the blues better preserved "the original melodic patterns of African music"

#african#igbo#afrakan#kemetic dreams#brownskin#africans#afrakans#african culture#brown skin#igbo culture#igbos#nigeria#igboland#Ethiopian airs#African music#Negro spirituals#wolof#fula#mandinka#banjo#african instruments#halam#akonting#jitterbug#Papa Charlie Jackson#ragtime#harmonic structure#harmony#afrakan spirituality#Bambara people

34 notes

·

View notes

Text

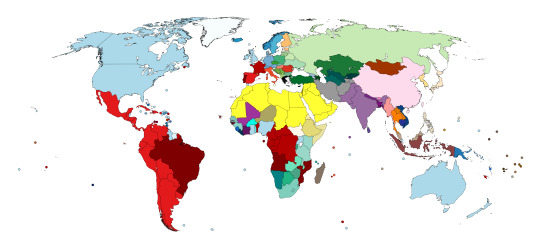

Most commonly spoken language in each country

I had to separate the legend from the map because it would not have been legible otherwise. I am aware that the color distinctions are not always very clear, but there are only so many colors in the palette.

The legend is arranged in alphabetical order and languages are grouped by family (bullet points), with branches represented by numbers and followed by the color palette languages within them are colored in, as follows:

Afroasiatic

Chadic (Hausa) — ocher

Cushitic (Oromo and Somali) — light yellow-green

Semitic (from Arabic to Tigrinya) — yellow

Albanian — olive green

Armenian — mauve

Atlantic-Congo

Benue-Congo (from Chewa to Zulu) — blue-green

Senegambian (Fula and Wolof) — faded blue-green

Volta-Congo (Ewe and Mooré) — bright blue-green

Austroasiatic (Khmer and Vietnamese) — dark blue-purple

Austronesian

Eastern Malayo-Polynesian (from Fijian to Wallisian) — dark brown

Malayo-Polynesian (Palauan) — bright brown

Western Malayo-Polynesian (from Malagasy to Tagalog) — light brown

Eastern Sudanic (Dinka) — foral white

Hellenic (Greek) — black

Indo-European

Germanic (from Danish to Swedish) — light blue (creoles in medium/dark blue)

English-based creoles (from Antiguan and Barbudan to Vincentian Creole)

Indo-Aryan (from Bengali to Sinhala) — purple

Iranian (Persian) — gray

Romance (from Catalan to Spanish) — red (creoles in dark red)

French-based creoles (from Haitian Creole to Seychellois Creole)

Portuguese-based creoles (from Cape Verdean Creole to Papiamento)

Slavic — light green (from Bulgarian to Ukrainian)

Inuit (Greenlandic) — white

Japonic (Japanese) — blanched almond

Kartvelian (Georgian) — faded blue

Koreanic (Korean) — yellow-orange

Kra-Dai (Lao and Thai) — dark orange

Mande (from Bambara to Mandinka) — magenta/violet

Mongolic (Mongolian) — red-brown

Sino-Tibetan (Burmese, Chinese*, and Dzongkha) — pink

Turkic (from Azerbaijani to Uzbek) — dark green

Uralic

Balto-Finnic (Estonian and Finnish) — light orange

Ugric (Hungarian) — salmon

* Chinese refers to Cantonese and Mandarin. Hindi and Urdu are grouped under Hindustani, and Bosnian, Croatian, Montenegrin, and Serbian are grouped under Serbo-Croatian.

#langblr#lingblr#spanish#english#french#german#catalan#russian#mandarin#hausa#somali#arabic#albanian#armenian#swahili#ewe#moore#wolof#vietnamese#samoan#palauan#malay#dinka#greek#tok pisin#hindustani#persian#haitian creole#papiamento#greenlandic

59 notes

·

View notes

Text

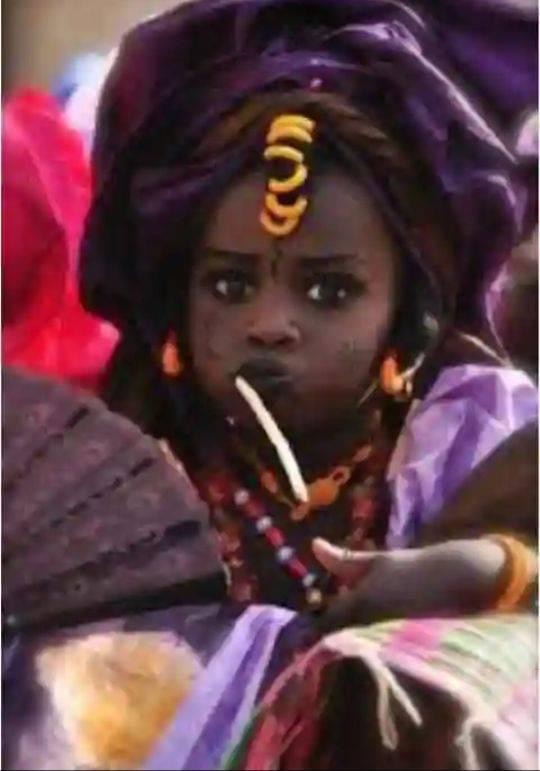

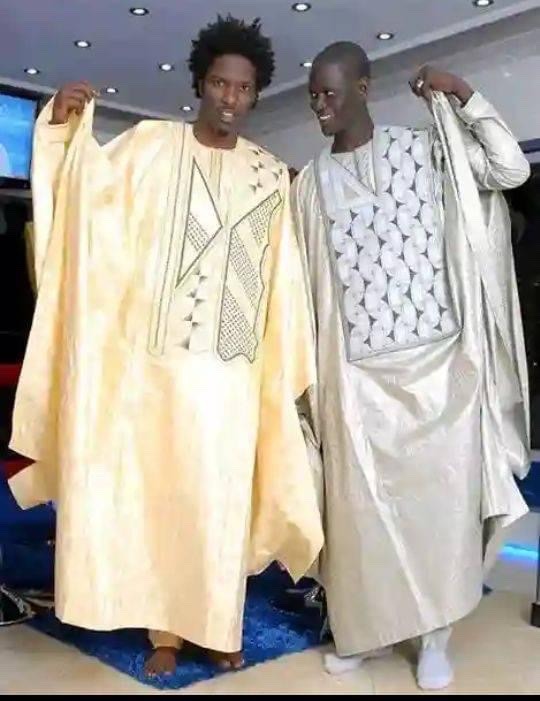

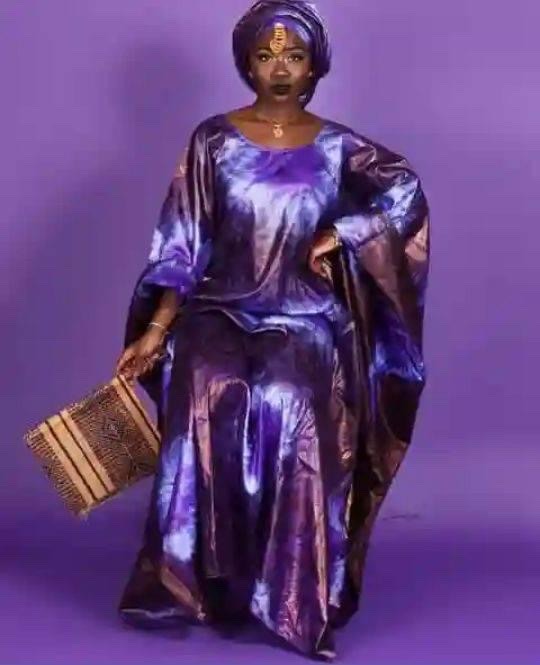

#sahel#sahelcore#mali#burkina faso#bambara#soninke#wolof#dogon#dogon door#Lobi#sahel aesthetic#senegal#fulbe#boubou#coiffure#west africa#the western sudan#l'afrique occidentale

64 notes

·

View notes

Text

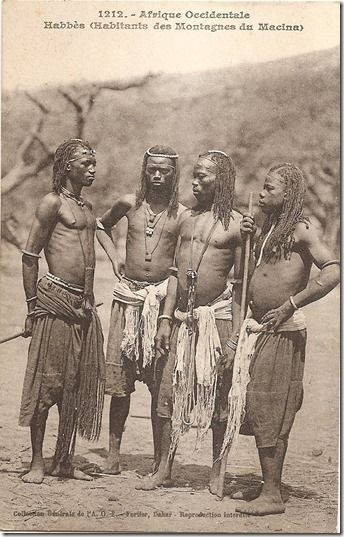

Wolof largest ethnic in Senegal 🇸🇳.

Wolof are very tall and mostly dark skin people of sahel (west Africa) found majority in Senegal, Gambia and southwestern Mauritiania, somewhere found small minorities in mali, guinea and guinea bissau. Wolof are ethnically senegambian family an ethnic family that include serer, fulani, jola or Diola, tuculur and lebu which culturally, and linguistically appear to be mutually intelligible as senegambian family that their origin date back to ancient bafour of Mauritania and far southermost sanhaja berber tribe called zenegha from where the word senegal come from. The ancient bafour paleolitic expansion appear to be mande ethnic family that their Neolithic expansion emerge as the pure ancestry to senegambian family.

The mande ethnic family ( serehule, mandinka, soninke, malinke, sosso, mandingo etc) and senegambian family (fulani, wolof, jalo, serer etc) share same origin and ancestry from basal west Africans ( the pure west African lineage) Bafour of Mauritiania

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

#music#el hadj n’diaye#Senegalese jazz#senegal#Senegalese music#Senegalese folk music#African folk music#African jazz#wolof#français#SoundCloud#jazz#folk music#black tumblr#blacktumblr

15 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

This Gambian Tradition Gave Me Chills | Griot Praise Singing Experience 🇬🇲

This Gambian Tradition Gave Me Chills | Griot Praise Singing Experience 🇬🇲 In this unforgettable vlog, I visit a friend in The Gambia and get immersed in a beautiful Wolof tradition — the ancient art of Griot praise singing. Griots are the West African historians, poets, and praise singers who keep oral traditions alive through music and storytelling. These Griot singers from the Wolof tribe performed a moving rendition of my name, transforming it into a series of powerful affirmations. Traditionally, griots sing praise names based on your family history — but even without knowing mine, they managed to make this moment incredibly special. I was showering them with money, which, as I learned, is a customary way of honouring and thanking the griots for their blessings and music. Watch as I experience this raw, soulful ceremony that connects music, ancestry, and good energy in the most magical way. ✨ Don't forget to LIKE, COMMENT & SUBSCRIBE for more African travel vlogs, spiritual encounters, and cultural experiences! 📍 Filmed in: The Gambia 🎤 Tribe: Wolof 🎶 Tradition: Griot Praise Singing 🔔 Subscribe for more: / @missdivalicious

#youtube#gambia#gambia travel vlog#WolofMusic#AfricanTravelVlog#MissDivalicious#PraiseSinging#CulturalExperience#AfricanTraditions#griot#GriotSingers#WolofCulture#wolof#kora#Griot praise singers

1 note

·

View note

Text

I don't suppose anyone here speaks Wolof, right? I'm trying to tell one of our workers that he has to go to a medical examination next week

0 notes

Text

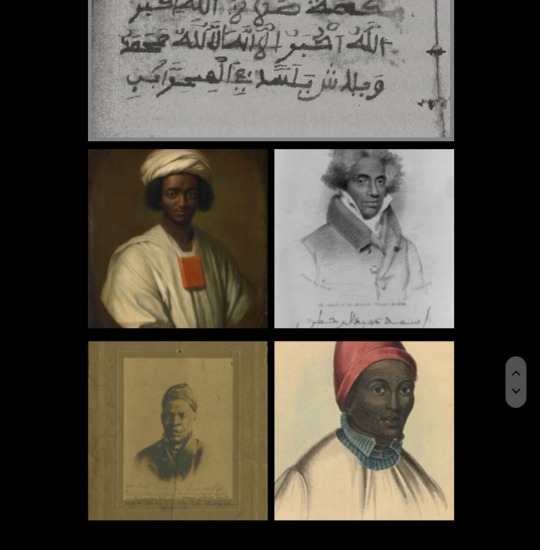

Distinctions in treatment between honorable and dishonorable members of the Wolof community. The construction of their dishonor vis a vis Islam seems to be a more recent phenomenon. So what was their status in society before Islam?

0 notes

Text

Currently working on a playlist of Wolof music for the fun of it, so if you have any recommendations, don't hesitate!

#wolof#wolof langblr#wolof music#i'm gonna be making playlists for all of my wishlist languages at some point so this is just the first of many

0 notes

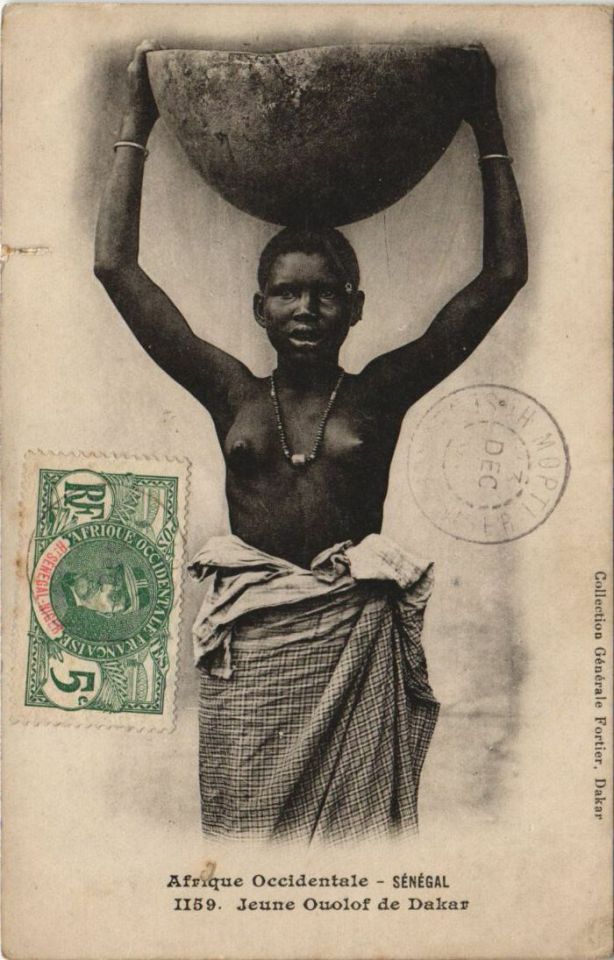

Text

Wolof woman from Dakar, Senegal

French vintage postcard, photographed by Fortier

#postkarte#postkaart#woman#ephemera#French#sepia#postcard#briefkaart#Wolof#Fortier#Dakar#carte postale#postal#photography#historic#photographed#vintage#from#tarjeta#ansichtskarte#photo#Senegal

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Why are East Africans darker than West Africans?

Most to all African people vary in color.

This question is like saying why do all Irish people only have red hair. Of course that is a grand generation. There's Irish people without red hair, and there's people with red hair that aren’t Irish.

Somali man

Xhosa man

Wolof Woman

Igbo Woman

Congolese Woman

Zulu Man

Fulani Women

Africans we are the most diverse people on the planet

#african#afrakan#kemetic dreams#brownskin#africans#afrakans#brown skin#african culture#skin tones#african diversity#shewa#ethiopian#wolof#congolese#somali

39 notes

·

View notes

Text

the switch 🫠

68 notes

·

View notes

Text

30 notes

·

View notes