#which is taking his autobiographical fiction at face value

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

It's also a cute nod to irl Akutagawa's admiration for Kunikida Doppo. When irl Akutagawa began writing more autobiographical fiction, he, to some degree, emulated Kunikida Doppo, and made reference to him:

"He kept a “Diary without Self-Deceit” in imitation of the writer Kunikida Doppo; on its lined pages he recorded passages like this: 'I am unable to love my father and mother. No, this is not true. I do love them, but I am unable to love their outward appearance. A gentleman should be ashamed to judge people by their appearance. How much more so should he be ashamed to find fault with that of his own parents. Still, I am unable to love the outward appearance of my father and mother… . Doppo said he was in love with love. I am trying to hate hatred. I am trying to hate my hatred for poverty, for falsehood, for everything.'"

Akutagawa Ryūnosuke, Daidouji Shinsuke: The Early Years

(Note: Although Akutagawa wrote Daidouju Shinsuke to be an effigy of himself, it's unclear if Akutagawa actually kept a "Diary without Self Deceipt" when he was younger. Regardless, he clearly held Kunikida in high regard.)

I completely forgot that Akutagawa told Kunikida point blank that he believed he was “worthy” of Dazai. In the original Japanese, he says Kunikida was “worthy of being Dazai’s cover,” with how well he’d held his own in a fight against Rashoumon. In the English dub, he says Kunikida was “worthy of being Dazai’s partner.”

Knowing what we know about Dazai’s former partner, Chuuya—who is not only someone universally revered and respected as one of the deadliest weapons of the Port Mafia—as well as Akutagawa’s famous obsession with being enough for Dazai himself, that’s a huge fucking compliment.

#akutagawa ryuunosuke#kunikida doppo#bsd#bungo stray dogs#the note is because theres a post claiming he kept a diary#which is taking his autobiographical fiction at face value#although autobiographical/confessional it's still fiction and should be approached with measured expectations re: the truth of the details#and theres no physical copy or evidence of a diary if he did keep one#but that's an aside#the point is that across universes#akutagawa respects kunikida

256 notes

·

View notes

Text

C. S. Lewis Masterpost

This year (2021) was my C. S. Lewis year! I read everything I own that he wrote. Some were re-reads, most were new to me but have been on my TBR for a while. I didn't make individual posts for each of them, so I decided to just give some brief thoughts here for anyone who's wondering what each book is about and whether they're worth reading.

Pictured above: the only part of my bookshelf organized by colour — I hope you enjoy it as much as I do!

Fiction

The Chronicles of Narnia: I don't think I need to say anything about these ones. Everyone has heard of it. Everyone should read it.

Fun Fact! There are two different ways you can read the series: in chronological order, or in the publication order. (So if you, like me, have ever looked at a mismatched set and wondered why the numbers on the spines don't make sense, that's why.) I personally prefer the publication order because I think it makes the most sense.

Publication order:

The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe

Prince Caspian

The Voyage of the Dawn Treader

The Silver Chair

The Horse and His Boy

The Magician's Nephew

The Last Battle

Chronological order:

The Magician's Nephew

The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe

The Horse and His Boy

Prince Caspian

The Voyage of the Dawn Treader

The Silver Chair

The Last Battle

Quotes: (1)(2)

The Space Trilogy: A guy named Ransom gets kidnapped by two scientists and taken to Mars. In the second book he voluntarily goes to Venus, and the third one takes place on Earth with some Arthurian mythos woven in. I really enjoyed the first book and would recommend it, but the second one turns into a really long philosophical debate in the middle and the third one is pretty much long and boring all the way through. My recommendation would be to read the first, skim the second, and skip the third.

Out of the Silent Planet | Perelandra | That Hideous Strength

The Dark Tower and Other Stories: This is a collection of Lewis's short fiction, some of it unfinished. The Dark Tower is set in the same universe as the Space Trilogy but not related to the main plot of that series, and it's unfinished. My favourite story was Forms of Things Unknown about a mission to the moon, and I also enjoyed After Ten Years which reinterprets some Greek mythology. Unfortunately that one is also unfinished, but a couple of Lewis's friends discuss where he was planning to go with the story based on their conversations with him.

The Dark Tower | The Man Born Blind | The Shoddy Lands | Ministering Angels | Forms of Things Unknown | After Ten Years

The Pilgrim's Regress: An autobiographical allegory inspired by John Bunyan's The Pilgrim's Progress that describes Lewis's journey from atheist to Christian. It centers around the idea of a desire that nothing in this world can satisfy, which you might recognize from a well-known quote from Mere Christianity. There were a lot of characters and situations that represented different schools of philosophy which I didn't really understand, but the parts that talked about the Landlord (God) all made sense to me and I just read the rest as a journey story at surface level.

Quotes: (1)(2)(3)(4)(5)

Till We Have Faces: A retelling of the myth of Cupid and Psyche from the perspective of Psyche's sister, Orual. I loved it! As someone who reads a lot of retellings, this one is up there with the best. It's very slow-paced and reflective as per Lewis's style, and it adds a lot of depth to the characters. Easily my favourite after Narnia!

Nonfiction

The Abolition of Man: What starts as a critique of an English textbook turns into philosophizing about human values. I didn't really understand this one. It's a short book with only 3 chapters.

The Great Divorce: This is the story about an afterlife bus ride from hell to heaven that explores Lewis's concept that "the doors of hell are locked in the inside" which is actually a quote from The Problem of Pain but expanded upon in this book. I found it interesting, but my mom said it was confusing, so idk. It's a pretty short book so take a chance on it.

Quotes: (1)(2)

The Screwtape Letters: You've probably heard of this one: a senior devil gives advice to his nephew on how to tempt a human and make sure he goes to Hell when he dies. It's fascinating, and kind of twisted. Would definitely recommend.

Quotes: (1)(2)(3)

Miracles: On whether miracles are really possible. My dad read this before I did and he told me there was a lot of unnecessary rambling in the middle chapters, but it started getting back on track toward the end. To my amusement, I discovered that the chapter in the exact middle of the book is, in fact, titled "A Chapter Not Strictly Necessary." And I agree with my dad's assessment; Lewis spends a lot of time discussing nature, materialism vs. spiritualism, rational thought, and the laws of physics (from a philosophical angle, not a scientific one), all of which he uses as building blocks for his argument about miracles but which I found difficult to follow a lot of the time. Eventually he does get around to talking about miracles, and biblical miracles specifically.

Quotes: (1)(2)(3)(4)

The World's Last Night: A collection of essays on topics including prayer, immorality, 'good work,' science and religion, and the Second Coming. I found most of them pretty interesting.

The Efficacy of Prayer | On Obstinacy in Belief | Lilies That Fester | Screwtape Proposes a Toast | Good Work and Good Works | Religion and Rocketry | The World's Last Night

Quotes: (1)

The Problem of Pain: Lewis tackles the question: if God is all-good and all-powerful, why do we suffer? I've read other things on this topic from other writers, so I was familiar with the basic arguments already, but I think Lewis explains it all really well.

Quotes: (1)(2)(3)(4)(5)(6)

The Four Loves: Lewis categorizes love into four types: Affection, Friendship, Eros, and Charity. The book is short but the chapters are loooooooong and there weren't any natural stopping places, so either you have to read 30-40 pages in one sitting or you have to stop in the middle of a thought.

Quotes: (1)(2)(3)(4)

Of Other Worlds: A collection of essays on the theme of writing, storytelling, fantasy, science fiction, and children's fiction. Most of them are pretty short and I really liked them! It also includes some fictional stories which were the same as in The Dark Tower.

On Stories | On Three Ways of Writing for Children | Sometimes Fairy Stories May Say Best What's to Be Said | On Juvenile Tastes | It All Began With a Picture... | On Criticism | On Science Fiction | A Reply to Professor Haldane | Unreal Estates

Quotes: (1)(2)(3)(4)

Mere Christianity: This was originally a series of radio talks broadcast during World War II, then later compiled and edited into a book. It covers the basic and foundational beliefs of Christianity. I read it first as a preteen when I was starting to question the faith I was brought up in, and this book provided a lot of answers! It's a classic for a reason.

Quotes: (1)(2)(3)(4)(5)(6)(7)(8)(9)(10)(11)(12)(13)

Surprised by Joy: An autobiography of Lewis's early life and the influences and experiences that led him to become an atheist and then later return to Christianity. Gotta be honest — this one bored me most of the way through, right up until the last couple of chapters.

Quotes: (1)(2)

God in the Dock: Another collection of essays on theology. There are 13 essays in about 100 pages, so they're all pretty short and to the point which makes for easy reading.

Miracles | Dogma and the Universe | Myth Became Fact | Religion and Science | The Laws of Nature | The Grand Miracle | Man or Rabbit? | 'The Trouble with "X" ...' | What Are We to Make of Jesus Christ? | Must Our Image of God Go? | Priestesses in the Church? | God in the Dock | We Have No 'Right to Happiness'

Quotes: (1)(2)(3)

Poetry

Poems: Did you know C. S. Lewis also wrote poetry? I'm not a big poetry reader, but there were a few I liked. I mostly bought it because it has a unicorn on the cover. ;)

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

ok there’s some discussion on that post about mitsuki so i thought i’d just expand on my general thoughts wrt her and all the other characters. because, like, i don’t actually think characters like twice, midnight, aizawa, all might, gran torino, best jeanist (god why are there so many) and SO ON really need to be “called out” or anything. i was more annoyed with the hypocrisy and comparative leniency that male characters like aizawa get when they do slapstick-y things, but if a woman makes a ~problematic~ joke that the author thinks is funny, they get blacklisted to hell and back. anyways

to be clear, i do think these actions like smacking katsuki or pulling on shinsou’s scarf fall within the realm of slapstick comedy. for all that hori can be criticized for, i think he makes it very clear when violence is supposed to matter and when it doesn’t. whether or not violence should be played for laughs, and whether slapstick humor should exist is another discussion, and i think it’s one best reserved for discussing at the real world level, rather than isolating specific characters and deciding whether punching someone for laughs makes them an acceptable character to stan or not.

at any rate, i think hori has made it clear that he doesn’t think aizawa or best jeanist are bullying the students. i think he’s also been fairly clear that he doesn’t intend for that scene in the bakugou household to be read as abuse. and i, personally, am completely fine with accepting this, because once you start going down the rabbit hole of ‘who has done something they need to be called out for?’ you end up with... jirou punching sero out. katsuki shocking kaminari into his whey~ state. all the boys and teachers letting mineta do whatever.

and to be very straight with it, i just... don’t care. i don’t care about scrutinizing every character when they do something for ~comedy.~ aside from mineta, whose entire actual character revolves around harassing the girls, it has no bearing on their normal portrayal. no one continues to express real worry that aizawa is going to hit them or even that midnight is going to be inappropriate. it’s neatly confined into one segment, and then the scene moves on. it’s not meant to seriously color our perception of those characters.

on the other hand, i think it’s the serious stuff which is meant to be taken at face-value that’s much more harmful. like the weird sexualization of the teenaged girls without any joking commentary, the possibly semi-autobiographical projection onto enjizz and the desperate attempts to make readers sympathize with him, the complete lack of acknowledgment towards female abuse victims, the way hori might be navigating marginalization and villainy as correlation. i would much rather talk about those things than how best jeanist was mean to katsuki.

it’s not that people aren’t allowed to be uncomfortable with these characters, to not want to see them or see support of them, etc. it’s not that these conversations aren’t important, because there is comedy that can be dangerous! transphobic and transmisogynistic gags are bad. sexual harassment gags are bad. but is all slapstick bad? or just certain kinds? i can definitely see how it can translate into irl harm, but i’m not inclined to say people have to agree with me or have to treat it as a major pressing issue.

especially since the way we deal with this convo in fandom is really unproductive. we’re picking out individual characters and individual actions to critique, when the problem with slapstick lies with the work as a whole. so why isolate each character from the context (the humor of the series overall) just to pick at specific incidents? why is listing the sins of individual fictional characters more important than just... letting the characters be and actually expanding your critique to the work as a whole?

and i accept that some people will take personal issue with things that those characters have done! esp characters like mitsuki who are particularly fraught! but at some point we’re just going to have to concede that one person’s interpretation and opinion of severity isn’t going to be everyone else’s, and we should probably try to be okay with that. in more ambiguous topics like these, there’s really not going to be an easy right or wrong answer, and the larger picture is lost when you’re trying to convince people that a specific character is Bad for doing something canon did not mean to make serious at all.

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

10 Books to Peel the Scales from Your Eyes

IN THIS MONTH’S SPDCLICKHOLE by Trisha Low

From visionary writers to collaborations that shift our perspective, from work that sheds a light on injustice and dares us to face it, we’re happy to honor this month’s #SPDHANDPICKED theme - VISION - with a list of books that peel the scales from our eyes.

1. Vision of the Children of Evil by Miguel Angel Bustos, trans. Lucina Schell (co-im-press)

"Like the tormented Peruvian César Vallejo or the Spanish madman-savant Leopoldo Panero, Argentina's Miguel Ángel Bustos ransacks the unconscious for its darkest revelations of the inexpressible. Like García Lorca forty years before in Spain, Bustos was murdered for his politics in 1976 by his country's military dictatorship. To render his hallucinated language and his dream-nightmare visions in credible English, Lucina Schell reaches for the edges of expression and introduces us to a strangely gifted, wildly imaginative, prematurely silenced twentieth-century voice."—Stephen Kessler 2. Tela de sevoya / Onioncloth by Myriam Moscona, trans. Antena: Jen Hofer with John Pluecker (Les Figues Press)

The narrator of TELA DE SEVOYA / ONIONCLOTH travels to Bulgaria, searching for traces of her Sephardic heritage. Her journey becomes an autobiographical and imagined exploration of childhood, diaspora, and the possibilities of her family language: Ladino or Judeo-Spanish, the living tongue spoken by descendants of the Jews expelled from Spain in 1492. Memoir, poetry, storytelling, songs, and dreams are interwoven in this visionary text—this tela or cloth that brings the past to life, if only for a moment, and that looks at the present though the lens of history.

3. Television by Claire Millikin (Unicorn Press)

"In this remarkable collection, Claire Millikin has made her own persistent music of a fully felt, fully experienced life in which 'what's broken never heals completely.' Often edging into what seems unspeakable, she finds a language that remains plain, steady, scrupulous, unsentimental and unshowy. Poem after poem registers the poet's 'battle for the moral world'—illuminating not only a single life but its human and environmental surroundings. As a motif draws us to the heart of a piece of music, Millikin's recurrent emblem is the centering fact and force of television: its role—fractured, phantasmagoric and familiar—in home and family, and in the wider world, where it may exercise its 'balm of blue light.'” —Eamon Grennan

4. Actualities by Norma Cole and Marina Adams (Litmus Press)

In this lambent collaboration, visual artist Marina Adams echoes the spareness of Norma Cole's language with delicate lines that contour muscular negative spaces, sometimes stark and densely foreboding, sometimes luxuriant with color. Norma Cole dialogues with Marina Adams with syncopated poems concerned with fragmentation, transformation, love, precarity, and the tenuousness of kinship between places, things, and being. In ACTUALITIES, poet and artist meditate in tandem, moving between anxiety and reconciliation, in a call and response with one another, and with a cosmos that continuously thwarts knowing, refusing to sit still.

5. Tucson Salvage: Tales and Recollections from La Frontera by Brian Jabes Smith (Eyewear Publishing)

This book is a chronicle of the overlooked and unsung, a collection of award-winning essays based on Brian Jabas Smith's popular column, "Tucson Salvage." "A true champion of the dispossessed and forgotten. ... I can't recommend this book highly enough."—Willy Vlautin

6. Bred from the Eyes of a Wolf by Kim Kyung Ju, trans. Jake Levine (Plays Inverse Press)

Equal parts poetry, drama, and sci-fi, award-winning poet Kim Kyung Ju's verse play BRED FROM THE EYES OF A WOLF follows a post-apocalyptic family of wolves (indistinguishable from humans) forced to taxidermy their own cubs in order to survive. An allegory for the degraded social relations of the present, Kim Kyung Ju's all-too-familiar dystopia partitions the male body into monetized parts while the female body is valued only for its reproductive ability. Various mythologies and science fictions layer one over the other—from Oedipus to zombies to a cybernetic police state—in this stunning depiction of family, alienation, and contemporary capitalism, translated from Korean into English for the first time by frequent collaborator Jake Levine.

7. Thirteen Ways of Looking at The Bus by Gizelle Gajelonia (Tinfish Press)

In THIRTEEN WAYS OF LOOKING AT THE BUS, Gizelle Gajelonia discovers her muse in Honolulu's TheBus mass transit system. She takes seriously (in this seriously funny chapbook) the notion of routes—routes through Hawai'i's history and geography, routes through American poetry, routes through languages spoken in Hawai'i. Many of the pieces parody canonical poems by T. S. Eliot, Wallace Stevens, Hart Crane, Elizabeth Bishop, John Ashbery, and Eric Chock. Out of her parodies come marvelous revisions. Among the figures included in Gajelonia's revised canon are Hawai'i's last queen, Lili'uokalani, Filipina nurses, and an honors thesis writer very like the author who dreams of Columbia University.

8. USO: I'll Be Seeing You by Kim Rosenfield (Ugly Duckling Presse)

USO: I'LL BE SEEING YOU is at its core a parable of performance and service. How does one perform/serve issues of identity, race, politics, and the essential vulnerability of what it means to be human? What is language in service of and when does it go too far? What degrades? What supports? What is heroic? What does it mean to put oneself at risk or in harm's way? This book speaks via the poetry of stand-up comedy to the U.S. involvement in the Middle East and the difficulties of naming the unnameable.

9. War and Peace 4: Vision and Text, by Judith Goldman and Leslie Scalapino, Editors (O Books)

WAR AND PEACE 4: VISION AND TEXT is devoted to collaborations between visual works and poetry, includes collaborative works of Charles Bernstein with Susan Bee, Amy Evans McClure with Michael McClure, Kiki Smith with Leslie Scalapino, Denise Newman with Gigi Janchang, a film on paper by Lyn Hejinian, Alan Halsey's visual texts, Simone Fattal, and Petah Coyne. Judith Goldman interviews Marjorie Welish, Lauren Shufran interviews Jean Boully, Leslie Scalapino interviews Mei-mei Berssenbrugge. Also included are E. Tracy Grinnell's homophonic translations of Claude Cahun's "Helene la rebelle" and poems by Fanny Howe, Thom Donovan, and others.

10. How Do I Look? by Sennah Yee (Metatron) Through a series of flash poetry/non-fiction pieces, Sennah Yee's debut full-length book HOW DO I LOOK? paints a colourful portrait of a woman both raised and repelled by the media. With pithy, razor-sharp prose, Sennah dissects and reassembles pop culture through personal anecdotes, crafting a love-hate letter to the media and the microaggressions that have shaped how she sees herself and the world. HOW DO I LOOK? is a raw and vulnerable reflection on identities real and imagined.

All #SPDhandpicked books on VISION are 20% off all month w/ code HANDPICKED

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

"New Fiction is Psychic Occupation” is generally warm piece on this trend in contemporary autofiction (Knausgaard, Ferrante, Lin, Kraus, Ben Lerner, Maggie Nelson) of really letting the reader occupy a certain psychic filter. Mark de Silva "Past Resistance" notices a similar pattern but calls it "Facebook Fiction" belittlingly. Here's de Silva making the case against types like Knausgaard:

Here are a few platitudes about memory. It’s subjective. It’s plastic. It’s often self-servingly selective, when it’s not simply fiction. Naturally, memoir, by which I mean that recounting of a human life in which protagonist and author are one, can’t help but inherit these liabilities. They once would have counted as such, anyway. In many quarters—in humanities departments, for some time now, and more recently and troublingly, in American politics and popular culture—acknowledging the frailty of memory and narrative history, whether personal or collective, seems to have brought with it a kind of relief from the age-old demands for objectivity (or even intersubjectivity). In many spheres of life, and especially online, we are now asked to admit to the looseness of memory’s grip, and the tallness of every tale. It’s what authenticity and honesty require, we are told: a frank reckoning with human finitude. But the news isn’t all bad (or is it?). For we are also invited to celebrate a newfound power over our pasts, and our presents too, through a curious form of autonomy that would have come as a surprise to a philosopher like Immanuel Kant: freedom from the tyranny of fact. Subjectivity, partiality, the fragment and the shard have all become refuges from the fraught, anxiety-making project of assembling wholes.

As a novelist, I have watched closely and with some dismay as this phenomenon has manifested in literary circles. Lately, mainstream critics and readers appear besotted by a shrunken, self-pitying strain of autobiographical fiction, one you could call with some fairness Facebook fiction, to distinguish it from the far thornier versions of the past, like Jacques Roubaud’s The Great Fire Of London, the first book in a notoriously vexing six-volume cycle of memoirs. Novels by Geoff Dyer, Sheila Heti, Ben Lerner and Karl Ove Knausgaard, whose own memoir cycle, My Struggle, might be usefully compared to Roubaud’s, if only to measure the diminution in ambition, seem premised on the notion that if it is our fate to embroider and even fabricate our pasts, insulating our preferred identities from the sharp edges of actuality, we ought to openly acknowledge our fraudulence and fantasize with purpose, even panache. (The current White House has taken note.)

For my part, I’ve never found this particular conscription of the imagination, whether in literature, electoral politics, or daily life, especially appealing. Some liberties aren’t worth taking. Reading these authors, one feels that if they had more conviction, they would exercise their imaginations properly in the invention of characters, plots, and settings, without simply lifting them from their own lives; or else they would get down to the painstaking work of research and corroboration that’s involved in any plausible (authentic, if you like) history, including autobiography. Instead, they’ve settled on a middling path, both creatively (why struggle to invent from whole cloth, when you can just use your life, your memories to fill in your novel?) and intellectually (why sift and weigh the facts when you can just make up what suits the tale you you’d like to tell, the person you’d like to be, whenever reality doesn’t oblige?).

This fall, I’ve been examining problems for the autobiographical self in our research seminar here at the University of Tulsa. I’ve also been teaching a course in the philosophy of art at Oklahoma State University. The combination has been revelatory. My aesthetics course has me thinking that the deepest difficulty attending the autobiographical self is one that afflicts art too: sentimentality. Nostalgia, its most obvious form, is hardly the end of it. For the tint of the glasses needn’t be rose. The red of self-lacerating shame, say, or of righteous indignation, will do just as well. As will the gray of ironic ennui.

Do just as well for what, though? Evasion—frequently of the self- variety. This, I think, is what binds the various forms of sentimentality together: the desire to feel a certain way about oneself or the world perverts the desire to know. Fantasy comes first. Yes, memory is malleable and subject to all sorts of failings, no one can seriously deny this, and no one should want to. But why treat these banal faults as insuperable, a limiting horizon of our humanness? When it comes to memory and personal testimony, we nearly always have some form of corroborating evidence to aid us—written records, videotape, artifacts of various sorts, and of course other people’s memories—which we can check our memories against, if we genuinely interested in the truth.

Now, the significance of events may be impossible to settle definitively, no matter how much checking and rechecking we do. But this fault cannot be accounted a failure of memory or narrative; it’s simply a consequence of events almost always being able to bear multiple interpretations. That lends no credence to the more extreme claims we now hear, for instance, that all narrative or memoir is really fiction. This claim is of just the same order as that all news is really fake, even if the people making these two assertions tend to belong to different political parties.

So here’s my provisional conclusion: rather than any intrinsic limitation on the faculty of memory or the practice of storytelling, it is sentimentality—ginned-up outrage at political goings-on that barely touch our lives, say, or tender melancholia about what America used to be like—that stands in the way good autobiography, good politics, and good fiction. That sounds like something we can work on, though, if not exactly master. Nothing like fate.

By way of mediation:

੪: Adding Dyer and Heti to the pack is sharp. "Facebook Fiction" seems more like Megan Boyle's Live Blog than someone like Ben Lerner, who is maintaining a serious ironic distance from his actual lived experience. My reading of 10:04 is that it's as many parts science fiction, poetry, and criticism as it is memoir. But the line that really loses me is:

Reading these authors one feels that if they had more conviction, they would exercise their imaginations properly in the invention of characters, plots, and settings, without simply lifting from their own lives.

It's a deontological appeal to work ethic that falsely equates proper procedure (or traditional conception thereof) with successful results. It seems like a mistake to think of art this way, where technique and materials are given values in themselves outside of their efficacy in imposing themselves on (& providing value to) the reader. Anyway, it seems like he allows that fiction-as-subjective-lived-experience can be valuable as an art form if it's done without sentimentality, so maybe the real point of contention is over how much sentimentality is in the air and how/why/the extent to which sentimentality hinders.

The phenomenology of consciousness isn't captured in this approach to writing, I think I agree, and also that it's troubling so many have taken a literary enterprise at face value. I think it probably speaks to the neutering of critical discourse.

I guess what I'm saying is perhaps there's a way the takes aren't mutually exclusive? Something like, “memory and writing are highly lossy, flawed forms of preserving and disseminating subjectivity, and should be treated skeptically/critically as such — but they're also probably the best we've got, and constitute a central reason why literature is still healthy despite major technological change” (compare the visual arts world, which is in a total mess).

I was messaging with a friend today about how I felt like one of the main benefits of experimenting with drugs was getting a glimpse into an alternate brain state, the experienced possibility of another way of being. This might even be part of the mechanism that makes LSD and ketamine such successful antidepressants: a glimpse, via serotonin or mu-opioid distortions, of a world packed with meaning and significance, helping disrupt the depression's feedback loops.

I wanna quote Brian Evenson here again because he made the same case I would before I did: for me [such fiction] is successful to the degree to which it allows readers to undergo an experience outside their immediate realm of possibility, and to the degree to which that second-level experience in turn functions in relation to the first-level experience that we think of as living. That’s not the same thing as a meaning. Nor does it have much in common with information or figuring out a puzzle. Rather, it is a form of affect intensively conveyed by utterance. […] Fiction is exceptionally good at providing models for consciousness, and at putting readers in a position to take upon themselves the structure of another consciousness for a short while. It is better at this than any other genre or media, and can do it in any number of modes (realistic or metafictional, reliably or unreliably, representationally or metafictionally, etc.).

1 note

·

View note

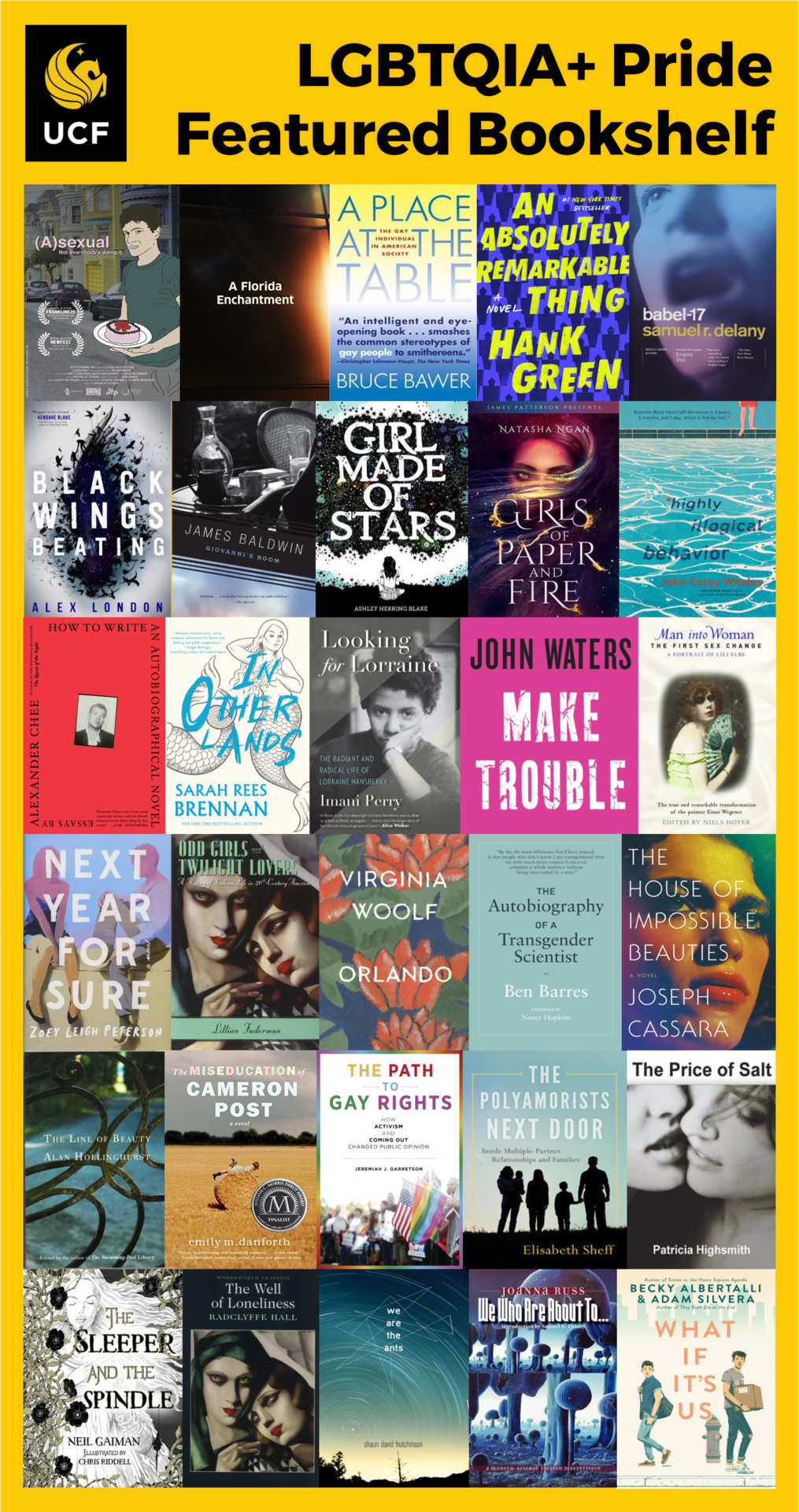

Photo

Ready to fly your flag?

Pride Month has arrived! While every day is a time to be proud of your identity and orientation, June is that extra special time for boldly celebrating with and for the LGBTQIA community (yes, there are more than lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender in the queer community). June was chosen to honor the Stonewall Riots which happened in 1969. Like other celebratory months, LGBT Pride Month started as a weeklong series of events and expanded into a full month of festivities.

In honor of Pride Month, UCF Library faculty and staff suggested books, movies and music from the UCF collection that represent a wide array of queer authors and characters. Additional events at UCF in June include “UCF Remembers” which is a week-long series of events to commemorate the shooting at the Pulse nightclub in 2016.

Click on the Keep Reading link below to see the full list, descriptions, and catalog links for the 30 titles by or about people in the LGBTQIA community suggested by UCF Library employees. These, and additional titles, are also on the Featured Bookshelf display on the second (main) floor next to the bank of two elevators.

(A)sexual directed by Angela Tucker Facing a sex obsessed culture, a mountain of stereotypes and misconceptions, and a lack of social or scientific research, asexuals - people who experience no sexual attraction - struggle to claim their identity. Suggested by Megan Haught, Teaching & Engagement/Research & Information Services

A Florida Enchantment directed by Sidney Drew A young woman discovers a seed that can make women act like men and men act like women. She decides to take one, then slips one to her maid and another to her fiancé. The fun begins. Suggested by Richard Harrison, Research & Information Services

A Place at the Table: The gay individual in American society by Bruce Bawers At the Lincoln Memorial, on the eve of his inauguration as president, Bill Clinton expressed his hope for a nation in which every American would have "a place at the table." For Bruce Bawer, that vision will become reality only when every gay man and woman becomes a full member of the American family. His book is a passionate plea that we recognize, and celebrate, our common backgrounds and common values - our common humanity. Suggested by Missy Murphey, Research & Information Services

An Absolutely Remarkable Thing by Hank Green The Carls just appeared. Coming home from work at three a.m., twenty-three-year-old April May stumbles across a giant sculpture. Delighted by its appearance and craftsmanship -- like a ten-foot-tall Transformer wearing a suit of samurai armor -- April and her friend Andy make a video with it, which Andy uploads to YouTube. The next day April wakes up to a viral video and a new life. News quickly spreads that there are Carls in dozens of cities around the world -- everywhere from Beijing to Buenos Aires -- and April, as their first documentarian, finds herself at the center of an intense international media spotlight. Now April has to deal with the pressure on her relationships, her identity, and her safety that this new position brings, all while being on the front lines of the quest to find out not just what the Carls are, but what they want from us. Suggested by Andrew Hackler, Circulation

Babel-17 by Samuel R Delany Babel-17, winner of the Nebula Award for best novel of the year, is a fascinating tale of a famous poet bent on deciphering a secret language that is the key to the enemy’s deadly force, a task that requires she travel with a splendidly improbable crew to the site of the next attack. For the first time, Babel-17 is published as the author intended with the short novel Empire Star, the tale of Comet Jo, a simple-minded teen thrust into a complex galaxy when he’s entrusted to carry a vital message to a distant world. Spellbinding and smart, both novels are testimony to Delany’s vast and singular talent. Suggested by Mary Lee Gladding, Circulation

Black Wings Beating by Alex London The people of Uztar have long looked to the sky with hope and wonder. Nothing in their world is more revered than the birds of prey and no one more honored than the falconers who call them to their fists. Brysen strives to be a great falconer--while his twin sister, Kylee, rejects her ancient gifts for the sport and wishes to be free of falconry. She's nearly made it out, too, but a war is rolling toward their home in the Six Villages, and no bird or falconer will be safe. Together the twins must journey into the treacherous mountains to trap the Ghost Eagle, the greatest of the Uztari birds and a solitary killer. Brysen goes for the boy he loves and the glory he's long craved, and Kylee to atone for her past and to protect her brother's future. But both are hunted by those who seek one thing: power. Suggested by Mary Lee Gladding, Circulation

Giovanni’s Room by James Baldwin Giovanni's Room traces one man's struggle with his sexual identity. In a 1950s Paris swarming with expatriates and characterized by dangerous liaisons and hidden violence, an American finds himself confronting secret desires that jeopardize the conventional life he envisions for himself. After meeting and proposing to a young woman, he falls into a lengthy affair with an Italian bartender and is confounded and tortured as he oscillates between the two. Now a classic of gay literature, Baldwin's haunting and controversial second novel is his most sustained treatment of sexuality. Examining the agonizing mystery of love and passion in an intensely imagined yet beautifully restrained narrative, Baldwin creates a moving and complex story of death and desire that is revelatory in its insight. Suggested by Rachel Edford, Teaching & Engagement

Girl Made of Stars by Ashley Herring Blake Mara and Owen are as close as twins can get, so when Mara’s friend Hannah accuses Owen of rape, Mara doesn't know what to think. Can her brother really be guilty of such a violent act? Torn between her family and her sense of right and wrong, Mara feels lost, and it doesn’t help that things are strained with her ex-girlfriend, Charlie. As Mara, Hannah, and Charlie come together in the aftermath of this terrible crime, Mara must face a trauma from her own past and decide where Charlie fits into her future. With sensitivity and openness, this timely novel confronts the difficult questions surrounding consent, victim blaming, and sexual assault. Suggested by Megan Haught, Teaching & Engagement/Research & Information Services

Girls of Paper and Fire by Natasha Ngan In this richly developed fantasy, Lei is a member of the Paper caste, the lowest and most persecuted class of people in Ikhara. She lives in a remote village with her father, where the decade-old trauma of watching her mother snatched by royal guards for an unknown fate still haunts her. Now, the guards are back and this time it's Lei they're after -- the girl with the golden eyes whose rumored beauty has piqued the king's interest. Over weeks of training in the opulent but oppressive palace, Lei and eight other girls learns the skills and charm that befit a king's consort. There, she does the unthinkable -- she falls in love. Her forbidden romance becomes enmeshed with an explosive plot that threatens her world's entire way of life. Lei, still the wide-eyed country girl at heart, must decide how far she's willing to go for justice and revenge. Suggested by Megan Haught, Teaching & Engagement/Research & Information Services

Highly Illogical Behavior by John Corey Whaley Sixteen-year-old Solomon has agoraphobia. He hasn't left his house in 3 years. Ambitious Lisa is desperate to get into a top-tier psychology program. And so when Lisa learns about Solomon, she decides to befriend him, cure him, and then write about it for her college application. To earn Solomon's trust, she introduces him to her boyfriend Clark, and starts to reveal her own secrets. But what started as an experiment leads to a real friendship, with all three growing close. But when the truth comes out, what erupts could destroy them all. Funny and heartwarming, Highly Illogical Behavior is a fascinating exploration of what makes us tick, and how the connections between us may be the most important things of all. Suggested by Rich Gause, Research & Information Services

How to Write an Autobiographical Novel by Alexander Chee How to Write an Autobiographical Novel is the author’s manifesto on the entangling of life, literature, and politics, and how the lessons learned from a life spent reading and writing fiction have changed him. In these essays, he grows from student to teacher, reader to writer, and reckons with his identities as a son, a gay man, a Korean American, an artist, an activist, a lover, and a friend. He examines some of the most formative experiences of his life and the nation’s history, including his father’s death, the AIDS crisis, 9/11, the jobs that supported his writing—Tarot-reading, bookselling, cater-waiting for William F. Buckley—the writing of his first novel, Edinburgh, and the election of Donald Trump. Suggested by Sara Duff, Acquisitions & Collections

In Other Lands by Sarah Rees Brennan In Other Lands is the exhilarating new book from beloved and bestselling author Sarah Rees Brennan. It’s a novel about surviving four years in the most unusual of schools, about friendship, falling in love, diplomacy, and finding your own place in the world ― even if it means giving up your phone. Suggested by Katie Burroughs, Administration

Looking for Lorraine: the radiant and radical life of Lorraine Hansberry by Imani Perry Lorraine Hansberry, who died in 1965 at age thirty-four, was, by all accounts, a force of nature. She was also one of the most radical, courageous, and prescient artist-intellectuals of the twentieth century--and one of the least understood. Defined largely by her groundbreaking play A Raisin in the Sun, Hansberry has been hidden in plain sight for decades. Little of her manifold contributions, her associations, her other writing, or her transgressive nature is known. A prolific and probing artist, she also committed herself passionately to political activism. Hansberry's unflinching dedication to social justice brought her under FBI surveillance in the midst of McCarthyism, when she was barely in her twenties. Suggested by Sara Duff, Acquisitions & Collections

Make Trouble by John Waters When John Waters delivered his gleefully subversive advice to the graduates of the Rhode Island School of Design in 2015, the speech went viral, in part because it was so brilliantly on point about making a living as a creative person. From an icon of popular culture, here is inspiring advice for artists, graduates, and anyone seeking happiness and success on their own terms. Now we all can enjoy his sly wisdom in a manifesto that reminds us, no matter what field we choose, to embrace chaos, be nosy, and defy outdated critics. Suggested by Seth Dwyer, Circulation

Man Into Woman: an authentic record of a change of sex edited by Niels Hoyer This riveting account of the transformation of the Danish painter Einar Wegener into Lili Elbe is a remarkable journey from man to woman. Einar Wegener was a leading artist in late 1920's Paris. One day his wife Grete asked him to dress as a woman to model for a portrait. It was a shattering event which began a struggle between his public male persona and emergent female self, Lili. Einar was forced into living a double life; enjoying a secret hedonist life as Lili, with Grete and a few trusted friends, whilst suffering in public as Einar, driven to despair and almost to suicide. Doctors, unable to understand his condition, dismissed him as hysterical. Lili eventually forced Einar to face the truth of his being - he was, in fact, a woman. This bizarre situation took an extraordinary turn when it was discovered that his body contained primitive female sex organs. There followed a series of dangerous experimental operations and a confrontation with the conventions of the age until Lili was eventually liberated from Einar - a freedom that carried the ultimate price. Compiled fron Lili's own letters and manuscripts, and those of the people who adored her, Man into Woman is the Genesis of the Gender Revolution. Suggested by Richard Harrison, Research & Information Services

Next Year, For Sure: a novel by Zoey Leigh Peterson In this moving and enormously entertaining debut novel, longtime romantic partners Kathryn and Chris experiment with an open relationship and reconsider everything they thought they knew about love. After nine years together, Kathryn and Chris have the sort of relationship most would envy. They speak in the shorthand they have invented, complete one another's sentences, and help each other through every daily and existential dilemma. When Chris tells Kathryn about his feelings for Emily, a vivacious young woman he sees often at the Laundromat, Kathryn encourages her boyfriend to pursue this other woman--certain that her bond with Chris is strong enough to weather a little side dalliance. As Kathryn and Chris stumble into polyamory, Next Year, For Sure tracks the tumultuous, revelatory, and often very funny year that follows. When Chris's romance with Emily grows beyond what anyone anticipated, both Chris and Kathryn are invited into Emily's communal home, where Kathryn will discover new romantic possibilities of her own. In the confusions, passions, and upheavals of their new lives, both Kathryn and Chris will be forced to reconsider their past and what they thought they knew about love. Suggested by Rebecca Hawk, Circulation

Odd Girls and Twilight Lovers by Lillian Faderman As Lillian Faderman writes, there are "no constants with regard to lesbianism," except that lesbians prefer women. In this groundbreaking book, she reclaims the history of lesbian life in twentieth-century America, tracing the evolution of lesbian identity and subcultures from early networks to more recent diverse lifestyles. She draws from journals, unpublished manuscripts, songs, media accounts, novels, medical literature, pop culture artifacts, and oral histories by lesbians of all ages and backgrounds, uncovering a narrative of uncommon depth and originality. Suggested by Missy Murphey, Research & Information Services

Orlando by Virginia Woolf Orlando, a novel loosely based on the life of Vita Sackville-West, Virginia Woolf's lover and friend, is one of Woolf's most playful and tantalizing works. This edition provides readers with a fully collated and annotated text. A substantial introduction charts the birth of the novel in the romance between Woolf and Sackville-West, and the role it played in the evolution and eventual fading of that romance. Extensive explanatory notes reveal the extent to which the novel is embedded in Woolf's knowledge of Sackville-West, her family history and her writings. Suggested by Rachel Edford, Teaching & Engagement

The Autobiography of a Transgender Scientist by Ben Barres As an undergraduate at MIT, Barres experienced discrimination, but it was after transitioning that he realized how differently male and female scientists are treated. He became an advocate for gender equality in science, and later in life responded pointedly to Larry Summers's speculation that women were innately unsuited to be scientists. Privileged white men, Barres writes, “miss the basic point that in the face of negative stereotyping, talented women will not be recognized.” At Stanford, Barres made important discoveries about glia, the most numerous cells in the brain, and he describes some of his work. “The most rewarding part of his job,” however, was mentoring young scientists. That, and his advocacy for women and transgender scientists, ensures his legacy. Suggested by Richard Harrison, Research & Information Services

The House of Impossible Beauties by Joseph Cassara A gritty and gorgeous debut that follows a cast of gay and transgender club kids navigating the Harlem ball scene of the 1980s and ’90s, inspired by the real House of Xtravaganza made famous by the seminal documentary “Paris Is Burning”. Suggested by Sara Duff, Acquisitions & Collections

The Line of Beauty by Alan Hollinghurst In the summer of 1983, twenty-year-old Nick Guest moves into an attic room in the Notting Hill home of the Feddens: conservative Member of Parliament Gerald, his wealthy wife Rachel, and their two children, Toby―whom Nick had idolized at Oxford―and Catherine, who is highly critical of her family's assumptions and ambitions. As the boom years of the eighties unfold, Nick, an innocent in the world of politics and money, finds his life altered by the rising fortunes of this glamorous family. His two vividly contrasting love affairs, one with a young black clerk and one with a Lebanese millionaire, dramatize the dangers and rewards of his own private pursuit of beauty, a pursuit as compelling to Nick as the desire for power and riches among his friends. Richly textured, emotionally charged, disarmingly comic, this is a major work by one of our finest writers. Suggested by Sandy Avila, Research & Information Services

The Miseducation of Cameron Post by Emily M. Danforth The Miseducation of Cameron Post is a stunning and provocative literary debut that was named to numerous best of the year lists. When Cameron Post’s parents die suddenly in a car crash, her shocking first thought is relief. Relief they’ll never know that, hours earlier, she had been kissing a girl. But that relief doesn’t last, and Cam is forced to move in with her conservative aunt Ruth and her well-intentioned but hopelessly old-fashioned grandmother. She knows that from this point on, her life will forever be different. Survival in Miles City, Montana, means blending in and leaving well enough alone, and Cam becomes an expert at both. Suggested by Rebecca Hawk, Circulation

The Path to Gay Rights: how activism and coming out changed public opinion by Jeremiah J. Garretson The Path to Gay Rights is the first social science analysis of how and why the LGBTQ movement achieved its most unexpected victory---transforming gay people from a despised group of social deviants into a minority worthy of rights and protections in the eyes of most Americans. The book weaves together a narrative of LGBTQ history with new findings from the field of political psychology to provide an understanding of how social movements affect mass attitudes in the United States and globally. Suggested by Missy Murphey, Research & Information Services

The Polyamorists Next Door: inside multiple-partner relationships and families by Elisabeth Sheff The Polyamorists Next Door introduces polyamorous families, in which people are free to pursue emotional, romantic, and sexual relationships with multiple people at the same time, openly and with support from their partners, sometimes forming multi-partner relationships, or other arrangements that allow for emotional and sexual freedom within the family system. In colorful and moving details, this book explores how polyamorous relationships come to be, grow and change, manage the ins and outs of daily family life, and cope with the challenges they face both within their families and from society at large. Using polyamoristsown words, Dr. Elisabeth Sheff examines polyamorous households and reveals their advantages, disadvantages, and the daily lives of those living in them. Suggested by Rebecca Hawk, Circulation

The Price of Salt by Claire Morgan The Price of Salt is the famous lesbian love story by Patricia Highsmith, written under the pseudonym Claire Morgan. The author became notorious due to the story's latent lesbian content and happy ending, the latter having been unprecedented in homosexual fiction. Highsmith recalled that the novel was inspired by a mysterious woman she happened across in a shop and briefly stalked. Because of the happy ending (or at least an ending with the possibility of happiness) which defied the lesbian pulp formula and because of the unconventional characters that defied stereotypes about homosexuality. The book fell out of print but was re-issued and lives on today as a pioneering work of lesbian romance. Suggested by Sandy Avila, Research & Information Services

The Sleeper and the Spindle by Neil Gaiman On the eve of her wedding, a young queen sets out to rescue a princess from an enchantment. She casts aside her fine wedding clothes, takes her chain mail and her sword, and follows her brave dwarf retainers into the tunnels under the mountain towards the sleeping kingdom. This queen will decide her own future -- and the princess who needs rescuing is not quite what she seems. Suggested by Rebecca Hawk, Circulation

The Well of Loneliness by Radclyffe Hall 'As a man loved a woman, that was how I loved...It was good, good, good...' Stephen is an ideal child of aristocratic parents - a fencer, a horse rider and a keen scholar. Stephen grows to be a war hero, a bestselling writer and a loyal, protective lover. But Stephen is a woman, and her lovers are women. As her ambitions drive her, and society confines her, Stephen is forced into desperate actions. The Well of Loneliness was banned for obscenity when published in 1928. It became an international bestseller, and for decades was the single most famous lesbian novel. It has influenced how love between women is understood, for the twentieth century and beyond. Suggested by Rachel Edford, Teaching & Engagement

We Are the Ants by Shaun David Hutchinson From the author of The Five Stages of Andrew Brawley comes an “equal parts sarcastic and profound” novel about a teenage boy who must decide whether or not the world is worth saving. Suggested by Rich Gause, Research & Information Services

We Who Are About To... by Joanna Russ Elegant and electric, We Who Are About To... brings us face to face with our basic assumptions about our will to live. While most of the stranded tourists decide to defy the odds and insist on colonizing the planet and creating life, the narrator decides to practice the art of dying. When she is threatened with compulsory reproduction, she defends herself with lethal force. Originally published in 1977, this is one of the most subtle, complex, and exciting science fiction novels ever written about the attempt to survive a hostile alien environment. It is characteristic of Russ’s genius that such a readable novel is also one of her most intellectually intricate. Suggested by Mary Lee Gladding, Circulation

What If It’s Us by Becky Albertalli & Adam Silvera Critically acclaimed and bestselling authors Becky Albertalli and Adam Silvera combine their talents in this smart, funny, heartfelt collaboration about two very different boys who can’t decide if the universe is pushing them together—or pulling them apart. ARTHUR is only in New York for the summer, but if Broadway has taught him anything, it’s that the universe can deliver a showstopping romance when you least expect it. BEN thinks the universe needs to mind its business. If the universe had his back, he wouldn’t be on his way to the post office carrying a box of his ex-boyfriend’s things. Suggested by Rich Gause, Research & Information Services

0 notes

Link

The Vision of the Holy Guardian Angel The Knowledge and Conversation of the Holy Guardian Angel and the Crossing of the Abyss are usually considered as the most important achievements on every magickal career. As a consequence, there’s a lot of speculative writing around these events. Confusion emerges since too many magicians wish they had already climbed whatever separates them from the loftiest grades, and too many self-proclaimed gurus need chelas to feel their own worth. Grades of attainment function like a map, but they become worthless if the map doesn’t actually map the territory. What use is a map if we can’t locate where we are? If distances are wrong, if we’re conferred grades that tell us “you’re here” but we aren’t, the map becomes useless. It will only pander to our ego, maybe getting even more lost. In “The Mystical Qabalah”, Dion Fortune assigns a spiritual experience named “Vision of the Holy Guardian Angel” to the Malkuth sephira. This is a good way to summarize this entrance into High Magick and our first meeting with the Angel, an event so intense and deep (in a magical way) that it is often mistaken either as the Abyss (since the jungian Shadow or Lesser Guardian of the Threshold looks close to what we’re told about Choronzon), either as the Knowledge and Conversation (since we actually meet the HGA). Since this is a common mistake and initiates who make such mistakes sometimes write magical texts, it is something we should really take into account when reading books and articles on the initiatory path. Aleister Crowley himself barely wrote about this first initiation. But he did. In the Book of the Law it is said, “Let him come through the first ordeal, & it [The Book of the Law] will be to him as silver.” [AL III, 64]. Three verses complete the description of the four great initiations: (“65. Through the second, gold. 66. Through the third, stones of precious water. 67. Through the fourth, ultimate sparks of the intimate fire.”). The very Book of the Law is a text that reflects the initiation of the reader, and therefore mostly useless for the uninitiated. These four initiations, are also the four gates to one palace we are told about in AL I, 51. As we focus on the first door, that which will turn the Book of the Law into silver and in which “The gross must pass through fire” (AL I,50), we find a clarification in Crowley’s New Commentary on these enigmatic verses: “This Book is now to him “as silver.” He sees it pure, white and shining, the mirror of his own being that this ordeal has purged of its complexes. To reach this sphere he has had to pass through a path of darkness where the Four Elements seem to him to be the Universe entire. For how should he know that they are no more that the last of the 22 segments of the Snake that is twined on the Tree?” Those who aren’t High Magick initiates, even if they’ve successfully used magickal techniques, be it spells, divination or any other device, internally conceive the universe as if it was solely composed by the old Four Elements. That is to say, matter is taken at face value, even by those who hold religious beliefs or maybe some sort of spirituality. What we’re dealing with here is a practical personal experience on magick and the collapse of standard reality. Non-initiates basically live in the world of Assiah, and there’s no order neither human being who can “provide” Initiation. The path of darkness Crowley wrote about teaches the magician that his perceptions about the universe are wrong. That the world isn’t as solid as he believes, so that a strong enough air current could make it crumble. That matter is kind of “alive”, that there’s a world inside the world he was unconscious of until he finally crossed this Threshold. This is the world of Yetzirah, the “astral”. The astral plane is not just some part of our imagination, but a layer of reality that overlaps those we usually perceive. It seems to magically bring life to matter, creating coincidences, ordering events. The magician tunes in with a series of threads of meaning that look like a huge intelligence who knows his innermost secrets. In Yetzirah, we learn to perceive the silver reflections that will ultimately guide us to the distant Sun of Tiphareth. In this initiation to Yetzirah, the Lesser Guardian of the Threshold turns into the Greater Guardian. Thus, we enjoy the Vision of the Holy Guardian Angel. This encounter might make us fall in love for the rest of our lives, treading towards Tiphareth and the Knowledge and Conversation, as we open ourselves to the plane of Briah. An ordeal of terror and darkness The opening of the world of Yetzirah isn’t a bed of roses. Quite on the opposite, it is a terrifying experience in which insanity becomes a real threat. It could make you so afraid you never ever practice magick again. You might end up in a nuthouse. The mind becomes terrified, because it realizes reality is way different than it expected. And this is coupled with the fact that the astral is actually reflecting the unconscious contents of the magician’s mind. Everything that’s buried deep within will try to devour the magician from the outside, as the world looks like it has become alive and reality directly speaks to us, in such a surreal experience that we could speculate as to whether we’ve become insane, or whether we’re dead and reality is melting around us, and an endless spring of ideas on reality that could carry us to a dead end if they were to solidify inside our minds. The most spectacular case in our times, might be the famous science-fiction author Philip K.Dick, who probably could never reach the other side safe and sound. However, he left us a fantastic account of his experiences in his Exegesis, and in his pseudo-autobiographic novel VALIS as well. May it then become a warning to the dilettante: Those who aren’t ready to lose everything for a kiss of Nuit shouldn’t take a single step on this path. Crowley wrote on the same verses [AL III,64] in the New Comment to the Book of the Law: ”Assailed by gross phantoms of matter, unreal and unintelligible, his ordeal is of terror and darkness. He may pass only by favour of his own silent God, extended and exalted within him by virtue of his conscious act in affronting the ordeal. This is the path we need to walk if the Book of the Law is to be as silver to us. This is a very specific path, numbered 32. It connects Malkuth and Yesod and thus corresponds in its deepest sense to the evolution from Neophyte (1°=10□) to Zelator (2°=9□). The true Zelator has overcome the terrifying ordeal of volatilizing that which was fixed, and he’s also brought down to earth the energies that were released through Initiation, and thus “a certain Zeal will be inflamed within him, why he knoweth not.”, as it is written regarding the Zelator grade. The 32nd path is related to Saturn, which makes illusions appear solid. This planet is also related to the Binah sephira. If we consider the legendary tenth verse from Crowley’s Oath of the Abyss (“that I will interpret every phenomenon as a particular dealing of God with my soul”) and the similarities between the Lesser Guardian of the Threshold and Choronzon, it all becomes confusing enough so that many who’ve gone through the 32nd path (and thus rendered the Veil of Qeseth) think they’ve won the ordeal of the Abyss, mistakenly proclaiming themselves Masters of the Temple and picturing themselves at the Atziluth heights, whereas they’ve just opened the moonlit door to Yetzirah. The magician will conclude this cycle when he manages to control the energies that were released in his experience of the Duat, in which he defeated his own demons. Then he will be definitely and irrevocably walking the initiatory path. And this shall not be taken lightly. Since, as Crowley writes on the Zelator Task (Liber Collegii Sancti, CLXXXV), “He may at any moment withdraw from his association with the A.'.A.'. simply notifying the Practicus who introduced him. Yet let him remember that being entered thus far upon the Path, he cannot escape it, and return to the world, but must ultimate either in the City of the Pyramids or the lonely towers of the Abyss.” Do not underestimate this warning. Because even if the Initiate wouldn’t continue, the path will continue without him and throw him unprepared into what’s ahead. One day such distant future will inevitably become the present, so facing it well-prepared must become a top priority for the magician.

#magick#thelema#Aleister Crowley#Zelator#Neophyte#Initiation#The Book of the Law#HGA#Holy Guardian Angel#Vision of the Holy Guardian Angel#Abyss#Knowledge and Conversation

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hyperallergic: An Artist Reinvents Herself to Mine the Fictions of America

Genevieve Gaignard, “Compton Contrapposto” (2016), chromogenic print, 32 x 48 in (all images © Genevieve Gaignard and courtesy of Shulamit Nazarian, Los Angeles, unless noted)

In the lead-up to a Trump presidency, the worst possible outcome for an America that has come so far in the past 100 years in terms of social progress and civil rights, it’s not insane to think that conservatives could take us back to a pre–Roe v. Wade era, to a time when all race-based hate crimes were labeled as basically normal. Not to mention that the environment and the economy will go to hell. This is not our country, and this is not the new normal — this is a time for refusal, a time to resist rather than to hallucinate into some sort of feeble complacency.

The election was certainly on my mind when I saw LA artist Genevieve Gaignard’s exhibition Smell the Roses at the California African American Museum. The characterizations that she creates in her work mine the intersections of race, class, and gender, portraying some of the vulnerable Americans who will be most affected by the next four years (or less, if Trump gets impeached like Michael Moore is predicting!).

This is Gaignard’s first solo museum show, which follows her solo exhibition Us Only last year at Shulamit Nazarin Gallery in Venice, California. Here, Gaignard continues her exploration of the space between performance and the reality of race, class, and gender through different personas or avatars, domestic spaces, and collections of Americana kitsch and knickknacks, toeing the line between high and low culture, between fiction and personal history. As the fair-skinned daughter of a black father and a white mother, her work speaks to being mixed-race, discussing issues of visibility and invisibility. She mixes highbrow and lowbrow aesthetics — a major influence is John Waters, who similarly indulges in camp and kitsch. Gaignard’s arrangements of objects ranging from books and records to family photographs mix the familial and the political in a way that’s reminiscent of Rashid Johnson’s post-minimalist, cold domestic “shelves.” The difference is that in Gaignard’s work, every object emanates warmth. It’s fitting that her exhibition deals heavily with the emotional experience of loss on both a personal and political level.

Genevieve Gaignard, “Extra Value (After Venus)” (2016), chromogenic print, 20 x 30 in

In her photography, Gaignard embodies various “persona-play performances,” a term coined by feminist art historian and critic Moira Roth, which refers to performances that blend autobiography and mythology. “Gaignard’s performances can be positioned in a genealogy of feminist persona-play, including Adrian Piper’s The Mythic Being, Lorraine O’Grady’s Mlle Bourgeoise Noire, and Howardena Pindell’s Free, White, and 21, as well as Nikki S. Lee’s Projects, Eleanor Antin’s black ballerina, Eleanora Antinova, and Anna Deavere Smith’s Twilight,” writes UCLA Associate English Professor Uri McMillan in his essay “Masquerade, Surface, and Mourning: The Performance of Memory-Work in Genevieve Gaignard: Smell the Roses.” It’s important to distinguish Gaignard’s work from the Cindy Sherman’s — a comparison it usually receives because of their shared interest in character. Sherman, however, reveals no autobiographical information, instead working with female archetypes in the media, whereas Gaignard makes the personal political while also creating new American mythologies.

In “Extra Value (After Venus)” (2016), the artist stands in front of an American flag mural painted on a brick wall wearing a shirt with the words “THUG LIFE” on the front, holding a large cup of soda and fries from McDonald’s. She gazes intensely at the camera as if to confront viewers with the fast food choices of poor and working-class American woman. In another photograph from this series, “Drive By Side Eye,” she stands adjacent to a red car that’s parked in front of an American flag, sipping her McD’s soda. In “Compton Contrapposto” (2016), she poses with her left leg bent in front of a vintage green ride, her hair poofed out into a ’70s-style ginger afro. These photographs all employ female stereotypes, creating characters that offer both intrigue — who is this person and why is she here? — and critique of such gendered American performances of femininity.

Genevieve Gaignard, “Red State, Blue Plate” (2016), chromogenic print, 24 x 36 in

“Red State, Blue Plate” (2016) sees Gaignard posed on top of a little red car with a Massachusetts license plate, holding a 40-oz Budweiser in one hand and a cigarette in the other. Her hair is straightened but wavy, and woods can be seen the background. In some of the other photographs, such as “Basic Cable & Chill” and “Smell the Roses” (both 2016), Gaignard poses in front of homes, blending herself into the landscape. In the photograph “The Color Purple,” she embodies a scared young girl standing in front of a purple house, simultaneously referencing Alice Walker’s novel The Color Purple. In placing her body here, she creates a new dialogue between herself, the house, and the literary reference to this story about women of color living through violence and oppression in 1930s Georgia.

Gaignard’s work may be compared to singer Nicki Minaj for her use of avatars, or to Japanese artist Tomoko Sawada, who creates different personalities and types based on stereotypes and categories of people in Japanese culture. Sawada uses the vernacular of public photo booths in much the same way that Gaignard uses the vernacular of American Dream fulfillment in her photography.

Genevieve Gaignard, “Smell the Roses” (2016), California African American Museum, Los Angeles, CA, installation view (image Courtesy of Shulamit Nazarian, Los Angeles)

Gaignard further explores class dynamics in this exhibit’s two domestic installations. One of these is a young girl’s bedroom, replete with Black Cabbage Patch dolls, a hanging felt cross, a vintage blue workout bike, and an MC Hammer Barbie with his hands up in the “Don’t shoot!” gesture, alluding to police slayings of Black men. On the wall outside this installation, a giant X marks it as unsafe, alluding to a poignant real-world tragedy for Gaignard, whose niece died in a fire. Her niece is also the subject of the photograph and memorial tribute “Baby Girl” (2016), which hangs in this installation. The sentiment of extreme pain signaled by loss is also found in the video “Missing You” (2016), located at the very back of the exhibition, where Gaignard embodies a Diana Ross–type diva persona, belting out lyrics that are a tribute to both her niece and the Black lives lost due to senseless acts of violence by the police, which sparked the formation of the Black Lives Matter movement.

Genevieve Gaignard, “Baby Girl” (2016), chromogenic print, 18 x 27 in

America is on the brink of an extreme-right backlash, facing white supremacy and, most likely, a plummeting economy and ravaged environment in the years to come — especially if Trump pulls out of the Paris Agreement. Now, more than ever, we need powerful work like Gaignard’s that fearlessly examines America’s heart.

Genevieve Gaignard: Smell the Roses continues at the California African American Museum (600 State Dr, Los Angeles) through February 26.

The post An Artist Reinvents Herself to Mine the Fictions of America appeared first on Hyperallergic.

from Hyperallergic http://ift.tt/2j0JQI7 via IFTTT

0 notes