#whereas sects are on power and merit

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Note

Hey! Since i saw Mount Hua, is this a full murim story, with the great sects and families? Are we going to have the Phoenix and Dragons system?

it's full murim, yes! "murim" is more of a guideline than a set system, so the "pheonix and dragon system" is just a popular trope in the genre. the strict ranking isn't included in this story, sorry!

the most powerful rising disciples of each sect are known as "dragons", a title bestowed by merit while sword saints are considered to be the top of the top – those who have mastered all there is to have mastered. there's been a veryyy small number of people who have been officially given that title throughout history. (should give you an idea of how insanely talented iseul is to already have people calling her that at such a young age lol)

there's nine great sects (shaolin, wudang, huashan, hwangbo, kunlun, qingcheng, kongtong, emei, zhongnan), and a tenth, gaibang, which focuses more on information brokerage than it does martial arts. and then there's five great families (tang, zhuge, namgung, murong, and hebei-peng). if you're wondering if you have to memorize all of these names, the answer is yes, and i'll be showing up on your doorstep to quiz each and every one of you /j

#anon#btw huashan/huasan is mount hua#the five great families are based on bloodlines#whereas sects are on power and merit

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

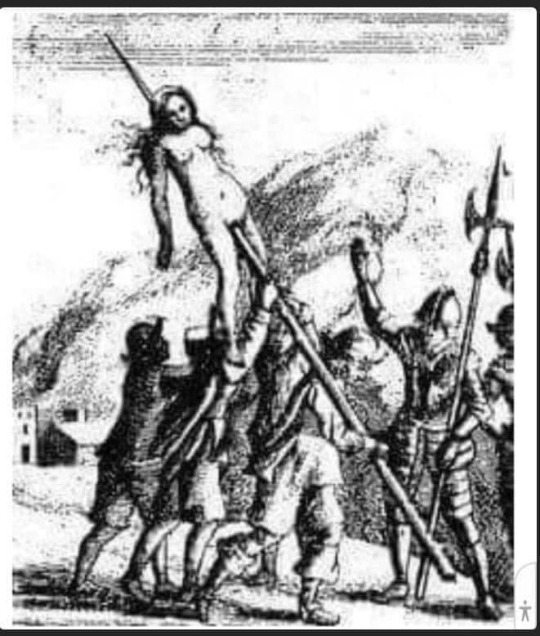

Because no one else has taken the time to correct OP's absolute brain dead drivel lemme throw a couple things out there: 1. This sketch comes from The History of the Evangelical churches of the valleys of Piemont by Sir Samuel Morland published in 1658 (https://archive.org/details/historyofevangel00morl/page/344/mode/2up). According to the original source it's a depiction of the execution of a woman named Anna, daughter of Giovanni Charboneire. A couple things to note; firstly, this has absolutely nothing to do with the spread of Christianity and is almost a thousand years removed from the time of Charlemagne. The events depicted in the book are about the Savoyard–Waldensian wars which took place from 1655-1690 which was both a period of persecution by the nationalist churches against the Waldensian sect and territorial conflict between Savoy and France. At most we can say this was an intra-religious conflict in Christianity, nothing to do at all with OP's claim of witchcraft 2. Let's talk about witchcraft. Firstly, the Christian Church has since the time of St. Augustine institutionally opposed persecuting witchcraft because witches don't exist and have no power.

The Church affirmed that people may be self deluded into believing themselves to have powers but that this delusion was either the result of mental illness (to use a more modern idea) or was a diabolic influence on the mind, not in reality. See the Canon Episcopi for primary source data or Jeffery Davies, A History of Witchcraft in the Middle Ages for secondary reading. The main witchcraft craze and much over publicized witch hunts of the late middle ages were largely the result of Protestant/Catholic conflict in border regions following the Reformation, Puritan Salem being a notable exception. 3. Finally, the first major demographics to convert to Christianity in the Roman Empire were women and slaves because, uniquely opposed to traditional pagan religions, Christianity affirmed the inherent dignity and worth of all humans, not just the male elite. To quote Geoffery Blainey's Short History of Christianity: "Whereas neither the Jewish, nor the Roman family would warm the hearts of a modern feminist, the early Christians were sympathetic to women. Paul himself insisted in his early writings that men and women were equal. His letter to the Galatians was emphatic in defying the prevailing culture, and his words must have been astonishing to women encountering Christian ideas for the first time: 'there is neither male nor female; for you are all one in Jesus Christ'. Women shared equally in what is called the Lord's Supper or Eucharist, a high affirmation of equality." TLDR: OP's claim is without any historic, theological, or intellectual merit. If one of my students gave me this I would give them remedial work on how to properly source information and do research.

This is just a reminder of how Christianity became so popular today.*

During the reign of Charlemagne, women were impaled on sharpened poles put in the vagina.

Slowly, over days, the pole would travel the length of the body through the organs, causing tremendous pain, simply because a woman was found collecting herbs in the forest. She was labelled a witch.

Their screams could be heard for days as an example to those who would not accept the foreign faith. Christianity became so popular because of sheer terror of what would happen if it wasn't accepted

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

Love and hatred entirely falsify our judgement; in our enemies we see nothing but shortcomings, in our favorites nothing but merits and good points, and even their defects see lovable to us. Our advantage, of whatever kind it may be, exercises a similar secret power over our judgement; what is in agreement with it at once seems to us fair, just and reasonable; what runs counter to it is presented to us in all seriousness as unjust and outrageous, or inexpedient and absurd. Hence so many prejudices of social position, rank, profession, nationality, sect, and religion. A hypothesis, conceived and formed, makes us lynx-eyed for everything that confirms it, and blind to everything that contradicts it. What is opposed to our party, our plan, our wish or our hope often cannot possibly be grasped and comprehended by us, whereas it is clear to the eyes of everyone else; on the other hand, what is favorable to these leaps to our eyes from afar. What opposes the heart is not admitted by the head. All through life we cling to many errors, and take care never to examine their ground, merely from a fear, of which we ourselves are unconscious, of possibly making the discovery that we have so long so often believed and maintained what is false. Thus is our intellect daily befooled and corrupted by the deceptions of inclinations and liking.

From: The World as Will and Representation

1 note

·

View note

Note

Prompt: someone of the (good-ish) mdzs cast is a serial killer. Why? Who else knows? Could be modern au, could be canon verse

Serial Killer - ao3

“So what are you going to do about it, Xichen?” Jin Guangyao heard Nie Mingjue demanding, and paused, tilting his head to the side to listen rather than proceeding to enter the room.

Nie Mingjue had gotten increasingly irascible as of late, no doubt in large part to the growing influence of the Song of Turmoil that he’d been playing for him, and much of his ire was (correctly, although unknowingly) aimed at Jin Guangyao. Most of the time, given Nie Mingjue’s straightforward nature, it was directly aimed at him, rather than through an indirect method, such as trying to convince Lan Xichen to turn away from him – and yet that was a method that Jin Guangyao was far more concerned about, given that Nie Mingjue had the benefit of a very old friendship with Lan Xichen that could be used to his benefit, if only he were a little less blockheaded about manipulating people.

Jin Guangyao absolutely refused to lose Lan Xichen, delighting as he did in the man’s faith and trust and benefiting from his influence and repeated interventions on his behalf; as a result, he would treat any such attempts by Nie Mingjue to drive a wedge between them very seriously. It therefore would be better to stay outside and listen, to figure out what argument Nie Mingjue was using and design appropriate countermeasures – to convince Lan Xichen that Nie Mingjue was, as usual, making a fuss when there was no reason, and that it was safe to simply ignore him or downplay his concerns.

Lan Xichen would believe him, as he always did, and never realize that he was helping push Nie Mingjue along the road to ruin – or indeed realize that he was pivotal to Jin Guangyao’s plan. Without Lan Xichen to support Jin Guangyao and make Nie Mingjue mistrust his own instincts, it would be much harder to isolate him from the few people he was willing to turn to for help, subtly influencing him not to believe his own symptoms, to doubt himself…to not realize what Jin Guangyao was doing to him.

“Da-ge…”

“Don’t da-ge me! He’s killing people!”

Jin Guangyao tensed.

How had Nie Mingjue discovered that?

Jin Guangyao had taken every precaution, going to great lengths to misdirect attention and cover up those deaths, whether it be the clans he’d fed into Xue Yang’s noxious experiments or else the ones he’d just had quietly executed somewhere no one would notice because they represented a threat to the rising power of the Jin sect. He’d known, of course, that he’d be held responsible for those deaths if anyone ever found out, there was no doubt that he would scapegoated by his father in that case, but he knew that it was especially dangerous to him if the person who discovered the truth was Nie Mingjue. Sure, he had his excuses ready in the event that Lan Xichen ever heard about it and found some evidence – he had a plan: to first deny convincingly, and then if that didn’t work, deny increasingly unconvincingly, and finally ‘give in’ and confess that he’d been driven to it by his father, that he’d been under duress, the sort of thing that Lan Xichen would happily swallow rather than believe that he’d been so fundamentally mistaken about Jin Guangyao.

Nie Mingjue, though – he’d been concerned that if Nie Mingjue ever found out about it, even the rumor of it without any evidence, he wouldn’t bother waiting for Jin Guangyao to explain or to blame his father. No, that brute would rather just take his saber and come and execute him on the steps of Jinlin Tower, if that was what it took to satisfy justice in his own mind, and never mind the consequences or costs. That Nie Mingjue would likely commit an honorable suicide thereafter for having misjudged and then executed his sworn brother was not, in fact, anywhere near as comforting as Nie Mingjue might think it was.

If anything, Nie Mingjue going to Lan Xichen with his concerns first was highly unexpected.

Jin Guangyao hated the unexpected.

“Da-ge, please, calm down,” Lan Xichen said, and his voice was – oddly calm, really. Jin Guangyao would have expected him to be a little more agitated, a little more demanding for details…was Lan Xichen’s faith in him really so strong? “Think this through before you do anything rash.”

“Rash!” Nie Mingjue fumed. “Rash..! Xichen, really.”

“You know he’s a good person,” Lan Xichen insisted, and Jin Guangyao smiled. “He has always meant well, strived to do good, regardless of whether it was commonly accepted – even you have to admit it.”

“I don’t have to admit anything,” Nie Mingjue grumbled, but Jin Guangyao could hear the rage dying down to something more of a simmer, rather than a roaring boil. Truly only Lan Xichen had such remarkable abilities, soothing the fierce beast with nothing but his presence and voice, no magic songs required – even Jin Guangyao found himself soothed by his presence.

There was a reason he wouldn’t give him up.

“You’ve known him for years, da-ge,” Lan Xichen said, voice soft, convincing, persuasive. Jin Guangyao didn’t have to be inside the room to imagine the scene he would see: Lan Xichen would be leaning forward, the slightest curve adding softness to the rigid posture required of Lan sect disciples, his eyes curved in a smile, his head a little dropped so that he could look up at Nie Mingjue with an expression of cheerfulness livened by a touch of mischief – full of charm, the way the women in the brothel practiced all day to do, but superior to any of their petty tricks. Lan Xichen was pure as a breath of fresh air in the lonely mountaintop, a benevolent god above the concerns of the world and yet determined to reach out his hands down to the needy – truly it was no wonder that Jin Guangyao was determined to take all that benevolence and joy and keep it all to himself. “For years, da-ge. And more than that, you know how hard he’s had it – how hard things have been, how much he’s suffered, all those things that other people don’t understand. You know that even when he’s strayed and been confused, he’s always returned back to the right way of doing things in the end.”

Nie Mingjue sighed, a great exhalation of breath.

“I suppose you’re right,” he conceded, and Jin Guangyao felt the sharp taste of joy on his tongue – there were few feelings in the world so great as this, to have started with nothing and risen so far, to have so thoroughly deceived these men, even Nie Mingjue who ought to know better after having seen him. “And yet, I can’t help but worry – this doesn’t seem like the rest of it. Isn’t he going too far this time?”

“Da-ge, if you have concerns, why not raise them with him directly?” Lan Xichen suggested, and Jin Guangyao nodded in approval. If Nie Mingjue came to him first with any concerns, he would be able to devise the appropriate response to those concerns – whether it was through coming up with some method of assuaging the concerns or in preemptively eliminated whoever had raised them, that was his business. Either way, it would be much easier to take action when he had prior warning, whereas some sort of unexpected public confrontation would be much more difficult to deal with.

“I don’t know, Xichen. You know he doesn’t listen to me.”

“That’s not true! Your opinion means so much to him – he’s always admired you, looked up to you. He wants you to approve of him.”

That was nonsense, of course. Jin Guangyao hadn’t cared one whit for Nie Mingjue’s opinion of him since the day the man had lost his usefulness – the Nie sect had been a necessary hurdle for him, the only Great Sect that allowed for promotion purely on the basis of merit without a thousand and one other rules, and Nie Mingjue himself was known to promote men quickly if they had skills he could use. Jin Guangyao had needed that back then, when he’d had nothing, and he’d been able to parlay it into additional use in the future: first, by getting Nie Mingjue’s recommendation letter to enter the Jin sect troops, although that hadn’t ended up working out, and then later, by using it to leverage himself a position with the Wen sect, courtesy of Wen Ruohan’s strange fixation on the Nie sect leader.

Would he like Nie Mingjue’s good opinion? Certainly, especially after he’d traded his somewhat dubious claim to a life-debt for Nie Mingjue swearing brotherhood with him; it would be extremely helpful if Nie Mingjue would support him the way Lan Xichen did. But since it didn’t seem likely that he’d be able to get on Nie Mingjue’s good side again, there was no point in expecting anything further from the man.

Well, no, that was wrong. He also expected great things from Nie Mingjue’s upcoming death, which would tally in quite nicely with many of his plans for domination in the cultivation world.

“I’d like to approve of him,” Nie Mingjue said. “I really would, Xichen, you know that. He’s smart and he’s capable and he has so much potential for goodness – I greatly admire him, really, I do. I would even go so far as to say that there are things for which I would trust his word over the evidence of my own eyes.”

Jin Guangyao couldn’t help but preen a little.

What an idiot, he thought, smiling. Truly there was nothing in that man’s brain but saber, and everything else had long ago rotted away – the Song of Turmoil boiling him alive until he was pickled with rage, leaving nothing else behind. Certainly not any critical thinking skills.

That final qi deviation must not be far away, now.

“But at the same time,” Nie Mingjue continued, presumably that last bit of self-preservation instinct trying to ring the alarms. “At the same time, I really do think that this is different in kind. It’s literally murder, Xichen. He’s murdering people. Not just killing, the way you do in wartime – actual murder. Premeditated, pre-planned murder. How can you just look away from that?”

Lan Xichen was quiet for a long moment, and Jin Guangyao tensed a little, his head tilting towards the door, awaiting the answer with both anticipation and fear.

“I think it’s a little more complicated than that,” he finally said, and Jin Guangyao’s eyebrows arched a little in surprise and wholly unanticipated pleasure. “It’s not just his actions that I look at, but those that died, too – we killed many people during the war, da-ge, didn’t we? Not all of whom had done evil against us, but who had to go because of the evil they represented…”

“Xichen!” Nie Mingjue cried, and for once Jin Guangyao couldn’t help but side with his reaction, his shock. “Are you suggesting that the victims deserved it?”

“Is that really so hard to believe?” Lan Xichen asked. Jin Guangyao had to admit that he was deeply impressed – he wouldn’t have thought Lan Xichen, the perfect gentleman, would have had it in him to side with him quite so deeply as that. “I’m with you, Mingjue-xiong. I’d believe him over even myself in just about every case – every time I’ve questioned what he was doing, he explained, and when he explained, I understood. It isn’t as black and white as all that.”

“I mean…I guess,” Nie Mingjue said, still sounding shocked and a little appalled. “But murder – so many murders…Xichen, are you sure it’s not some sort of qi deviation, something that gives him pleasure in taking lives? Are you sure each one is justified?”

“Those are two separate questions,” Lan Xichen said delicately. “I do think he takes pleasure in the act, and although I don’t understand it myself, I can understand that it helps him deal with…everything, really. Everything that’s happened to him. The tragedy, the senselessness of it…maybe it helps him feel better about it, helps comfort him. Maybe it’s some sort of sense that he’s evening the scales, perhaps? Some overall karmic balance?”

Jin Guangyao nodded along. He could certainly see Lan Xichen talking himself into believing something like that, and who knew? Maybe it was even a little true. He certainly enjoyed taking out the trash that had seen itself as above him, enjoyed stamping their lives into the mud – he wouldn’t have done it if it wasn’t a necessity, a part of his power play, and he wouldn’t have described himself as taking pleasure in it, but at the same time, he certainly didn’t regret any of it. If it made Lan Xichen feel better to think that he had some sort of complex psychology driving his actions, well, so be it.

As long as he continued to support him.

“But as for whether it’s justified…” Lan Xichen sighed. “I’m not perfect at telling good from evil, Mingjue-xiong, and neither are you. No one is. Wouldn’t you agree?”

Nie Mingjue grunted. It almost sounded as if he really were agreeing.

Was Lan Xichen really convincing Nie Mingjue that Jin Guangyao ought to be allowed to murder people with impunity as long as he came up with a good enough reason for it in advance? How delightful.

Jin Guangyao couldn’t help but wonder – although he’d never actually take the risk of it – whether he could convince Lan Xichen that Nie Mingjue’s death, too, had been justified. It was an amusing enough thought to make him genuinely smile, a smile full of all the bloodthirstiness he normally kept hidden deep down: truly, if he had his choice in the matter, he’d love to see Nie Mingjue’s expression if he ever found out what Jin Guangyao was doing to him, ideally once it was too late for him to do anything about it or alert anyone to what was happening.

Maybe, if Jin Guangyao could arrange to be there to push him over the edge, he might even get to see it.

Maybe he’d even remind him of this little conversation, and ask if he found his own murder justified.

“All right, then,” Nie Mingjue finally said, exhaling slowly, and Jin Guangyao bit his lips to keep from laughing out loud. “I see what you mean, and…yes, I suppose you’re right, Xichen. I may not understand all the motives behind the murders, and I may not like the idea of just – trusting that he knows what he’s doing in killing them, but at the same time…”

He sighed.

“At the same time, I can’t disagree that if there’s one person I trust to have a good reason to kill someone in some deserted place for their undiscovered wrongdoings, it would be Wangji.”

Jin Guangyao’s smile faded away.

Lan Wangji?

What in the world were they talking about? How had Lan Wangji entered into it?

It wasn’t as if Lan Wangji were going around randomly killing people for, what, sport – killing them, and then justifying their deaths as having been deserved because they had supposedly done bad things –

A hand fell on Jin Guangyao’s shoulder, and he jumped a little, surprised: he hadn’t realized that anyone else was there with him in the deserted hallway or seen them come up behind him, much less close enough to touch.

He turned around: it was Lan Wangji himself, pale-faced and miserable the way he’d looked since the Massacre at the Nightless City, since he’d missed the Siege of the Burial Mounds on account of being confined – miserable, but upright, hale and hearty and righteous as always, his eyes bright with passion that verged on obsession.

He had his sword in his hand.

It was unsheathed.

“Wait,” Jin Guangyao said, taking a step back, his eyes going wide as he realized something. Surely he didn’t mean to – surely they hadn’t really meant – surely not – “Wait, Wangji, don’t..!”

230 notes

·

View notes

Note

hello, i hope you are having a nice day! i come with a question about how Shen Qiao interprets Daoism in QQ, to peruse at your leisure... So in ch 57 of the Dao de Jing, Lao Tze writes: " The more laws and restrictions there are, the poorer people become. The sharper men’s weapons, the more trouble in the land. The more implements to add to their profit that the people have, the more strange things happen. The more rules and regulations, the more thieves and robbers in the land. " (1/3)

(daoism anon con't) "Therefore the sage says: I take no action and people are reformed. I enjoy peace and people become honest. I do nothing and the people become rich. I have no desires and people return to the good and simple life." Shen Qiao rightly observes that under multiple oppressive hierarchies (such as under multiple competing ruling kingdoms/families/powerful sects), the common folk/poor suffer greatly (2/3)

(daoism anon con't) But instead of advocating for the elimination of such oppressive hierarchies, as a Daoist, Shen Qiao seems to think that centralizing said multiple oppressive hierarchies under one singular, unified, oppressor is a good means to lessen suffering (3/4, actually, there's one more part)

(daoism anon con't) Whereas in that excerpt of the Dao de Jing, if my interpretation of the text is not egregiously wrong, Lao Tze seems to be implying that it is actually the abolishment of such restrictive hierarchies in the first place that will be necessary to lessen human suffering at all... This strikes me as a contradiction. Thoughts? (4/4)

uhhhh okay so first of all anon, I applaud you for your intellectual curiosity in seeking out the Daodejing, because I've read it multiple times and it still hurts my brain

second of all, I've thought about this for a bit and must admit that, w/r/t to the thesis of "Meng Xishi failed to portray Shen Qiao's actions and beliefs in 《千秋》 in an authentically Daoist manner," I disagree on four levels, which I suppose I will detail below like the clown I am:

(I would also like to acknowledge that this may not be your thesis, as you asked for thoughts in general! but it is easier to set up a premise and then evaluate said premise when it comes to organizing this post so I shall proceed thusly)

1) genre and expectation

look, I love this book as much as the rest of you, but at the end of the day, I think it's worth keeping in mind that this is a wuxia danmei webnovel, not an academic treatise on Daoism / Daoist thought / Daoist practice. I'm personally of the belief that any philosophical/historical accuracy present in 《千秋》 is an advantage of the text, whereas any lack thereof is not a detriment to its merit. you could grade books based on the faithfulness/thoughtfulness of their renditions of Daoism/Daoist characters if you wanted to I suppose, but I'm personally uninterested in evaluating texts that way

basically, I'm constantly on my ahistoricity of guzhuang/gufeng media agenda, which I’m aware is a bit different because 《千秋》 is situated in a specific historical period, but the text remains fundamentally wuxia in genre rather than historical fiction so like. we COULD evaluate texts based on their historical authenticity but I'd rather not ascribe inherent value based on a webnovel’s adherence to historical accuracy since these texts are all, at the end of the day, fundamentally and inescapably modern

might not have been the intent behind that thesis! just wanted to get this out there

2) problematizing/destabilizing our understandings of philosophical Daoism

(obligatory disclaimer that I'm only discussing philosophical Daoism, not spiritual/religious Daoism, as I am dramatically unqualified to mention anything about the latter)

all right, bear with me, I'm going to ramble about Han Dynasty scholar Liu Xiang for a bit, because some academics have made the case that he is the single most important figure in the Chinese literary tradition and I honestly don’t think they’re wrong to do so. and yes, we're including Sima Qian and Confucius in this ranking

so! partway through the Western Han era, circa the 1st century BCE, 汉成帝 Emperor Cheng of Han looks at his imperial archives and thinks to himself, "damn, this place is a mess," and orders Liu Xiang to organize the libraries. this is for the record, a project of an absolutely mind-boggling scale since the imperial archives haven't been organized since... well, the beginning of time/written history. everyone, admittedly, has been a bit busy 1) inventing a writing system and 2) trying not to die throughout the Zhou and Qin era, which had quite the body count. anyway, it takes Liu Xiang the remaining 20 years of his life and then some to finish this (the project had to be completed by his son, Liu Xin).

the point I'm trying to make is, Liu Xiang was confronted with the mess of the imperial archives, stacks upon stacks upon stacks of bamboo scrolls collected from across the empire in varying states of completion/intactness (this was, in fact, before paper had been invented) and tasked to 1) sort through everything, 2) organize and collate the texts, 3) eliminate duplicates, and 4) create a bibliography complete with text names, authorial attribution, and abstracts

if you're interested in this, I recommend looking into the 艺文志, which is one of the bibliographic catalogs that records these texts, their backgrounds, and how many scrolls they contained. this is particularly significant because it helps us track how texts like the 《庄子》 or the 《荀子》 expanded during Han Dynasty bibliographic collation (read: had other texts forcibly incorporated), and how many scrolls have been lost to the ravages of history since then

if you go on ctext.org and do a quick search for 道家 dao jia — literally, "the Daoist school of thought" — you'll find that this term doesn't really start appearing in texts until the Han Dynasty. this is significant because it implies that there wasn't really a “school of Daoist thought,” per se, prior to the Han Dynasty

basically, what I'm trying to get at is the fact that what we call 道家 'Daoism' isn't so much a discrete school of thought as it's like... a general bucket that Liu Xiang started yeeting similarly-minded texts into. it just so happened that it was convenient, and it caught on, and people really liked pitting it against 儒家 Ruist (aka Confucian) thought, and now it's like, a Thing. but like, even a question like “what is the Central Daoist Text?” can be difficult to answer, because Laozian thought and Zhuangzian thought can be radically different, despite the fact that they're both considered Daoist thinkers, and also this is Liezi erasure but that’s neither here nor there

(once again — I am attempting to destabilize our notions of philosophical Daoism as a definable entity; spiritual/religious Daoism has its own structure and organization that I have not studied!)

what even is Daoism? really hard to say! we can make vague, sweeping generalizations about principles of 出世 chu shi / "exiting society" and 无为 wu wei / "non-action," we can draw parallels with Buddhist thought and the elusive, evocative descriptors of 玄 xuan / "dark mystery" and 德 de / "virtue” (yes, but also “charisma,” and “power,” and—), we can analyze the writings and actions of self-professed historical Daoist statesmen and emperors, we can bang our heads against the cryptic wisdom poetry of the Daodejing and the general chaotic mindfuckery of the Zhuangzi, but like. this isn't a school of thought that one can draw up a syllabus for and then evaluate a person's actions against to see if they get a good grade in Daoism. in fact, doing so kind of misses the whole emphasis on naturalism and spontaneity that Zhuangzi in particular is rather fond of

3) the pitfalls of reading Daoist principles as legalistic precepts

which leads me to my third point — I'm... not sure there's much value in holding up individual quotes from the Daodejing and comparing Shen Qiao's actions against them. Because like, if we're evaluating Shen Qiao against the letter of the (Daodejing) law, I can pick out a whole host of problems before we even get to his political conduct:

5: 天地不仁,以萬物為芻狗;聖人不仁,以百姓為芻狗...

"Heaven and earth are not benevolent, taking the myriad things as straw dogs. The sage is not benevolent, taking the common people as straw dogs..."

all the glosses I've ever come across note that "straw dogs" are specifically grave-goods, and minimal in worth. the point is, neither heaven, earth, nor the sagely man are benevolent. yeah, um, Shen Qiao... fails that one

personally, I find the political readings of the Daodejing moderately alarming. take these chapters, for instance:

65: 古之善為道者,非以明民,將以愚之。民之難治,以其智多...

"In ancient times, those good at practicing the Way did not use it to enlighten the people, but rather keep them in the dark. The people are hard to govern because they know too much..." (trans. Phillip J. Ivanhoe)

80: 小國寡民。使有什伯之器而不用;使民重死而不遠徙。雖有舟輿,無所乘之,雖有甲兵,無所陳之。使民復結繩而用之,甘其食,美其服,安其居,樂其俗。鄰國相望,雞犬之聲相聞,民至老死,不相往來。

"Reduce the size of the state; lessen the population. Make sure that even though there are labor-saving tools, they are never used. Make sure that the people look upon death as a weighty matter and never move to distant places. Even though they have ships and carts, they will have no use for them. Even though they have armor and weapons, they will have no reason to deploy them. Make sure that the people return to the use of the knotted cord.* Make their food savory, their clothes fine, their houses comfortable, their lives happy. That even though neighboring states are within sight of each other, even though they can hear the sounds of each other's dogs and chickens, their people will grow old and die without ever having visited one another." (trans. Phillip J. Ivanhoe)

* the knotted cord being the pre-written script method of keeping accounts and tracking quantities

what I'm trying to get at here by quoting more Laozi at your Laozi is that... well, the Daodejing is not a kind text. it can actually be rather extreme, elitist, and anti-intellectual depending on which passages you read and how you interpret them (and there are many different interpretations! behold, a collection of many translations of the first chapter alone, and don’t even talk to me about textual variation and variations in punctuation because guess what, the meanings change when you punctuate it differently and like man I know writing was still a work-in-progress/always will be a work-in-progress but must you test me like this, Laozi-who-is-almost-certainly-a-made-up-author???).

if we wanted to evaluate Shen Qiao against the principles of the Daodejing, I mean, sure, we could. he’d fail pretty badly. I also think that's almost missing the point, because Daoism isn't really a school of thought that cares to nitpick or pedantically adhere to pre-scripted rules. in fact, there's this delightfully sassy passage from the Zhuangzi:

荃者所以在魚,得魚而忘荃;蹄者所以在兔,得兔而忘蹄;言者所以在意,得意而忘言。吾安得忘言之人而與之言哉?

《庄子·外篇·外物》

"A trap is for fish: when you've got the fish, you can forget the trap. A snare is for rabbits: when you've got the rabbit, you can forget the snare. Words are for meaning: when you've got the meaning, you can forget the words. Where can I find someone who's forgotten words so I can have a word with him?" (trans. Paul Kjellberg)

in a sense (and according to Zhuangzi), the best Daoist is the person who has forgotten Daoism; someone who has become so naturally in tune with the 道 / the Dao / the capital-w Way that they are effortlessly Daoist (we love a good effortless efficaciousness). what does that entail in terms of concrete, measurable terms? I truly could not tell you. it’s like. you gotta vibe with it, y’feel. at least, Zhuangzi would like you to vibe with it, and truly there is no other way to read the Zhuangzi

4) the narrative themes of 《千秋》 itself

but like, when it really comes down to it, I think two of the the primary themes of 《千秋》, especially examined through Shen Qiao’s character arc, are 1) the multiplicity of Dao / Ways one can live one’s life, and 2) the insufficiency of a single school of thought to supply all solutions

as for the first point, a line Shen Qiao often repeats is 大道三千,只有前后,无有高下 / “the Great Way has three thousand forms — some may come before or after others, but none are superior or inferior to others.” Again and again, we see Shen Qiao’s Dao/Way challenged — by Yan Wushi, naturally, but also by Yu Ai, by Sang Jingxing, by Chen Gong. And we continually see that Shen Qiao doggedly chooses to adhere to his own Dao/Way, no matter the sacrifice, but that does not mean that he denies the validity of other people’s Ways (Bai Rong in particular comes to mind), nor that other people are invalid. there is a multiplicity of ways to conduct oneself in the world. some may seen more praiseworthy than others. some are more effective when it comes to enacting sweeping change. and some are purely destructive. Shen Qiao rarely judges other people for their choices, and Shen Qiao remains our moral compass for the novel, the guiding light for the entire jianghu

this whole discussion brings to mind two parts of the novel:

宇文邕说罢,望住沈峤道:“先生身为道门中人,想必也觉得朕做错了?”

沈峤:“道如水,水善利万物而不争,道法自然,和光同尘,顺应天理人情者,方为道。”

After Yuwen Yong finished, he gazed at Shen Qiao and said, “As a member of the Daoist schools, you probably think I was wrong [to outlaw Buddhism and Daoism].”

Shen Qiao said, “The Dao is like water—water brings benevolent benefit to the myriad things and does not compete. The Daoist method is natural, harmonious and accommodating. That which conforms with the principles of heaven and human nature is the Dao.”

(chapter 36)

if memory serves, Shen Qiao says this a bit more clearly in the audiodrama version of this scene, but tl;dr the point he’s making is that Yuwen Yong didn’t ban true Daoism, just the deceptive superstition that was masquerading as Daoism. The Dao, in Shen Qiao’s words, remains much more vast, elusive, and powerful than human action, unconstrained, unlimited, even unknowable by mere human law

meanwhile, Qi Fengge says in chapter 46:

“在这世间,有许许多多的人,有好人,也有坏人,还有更多,不能单纯用好和坏来区分的人,他们的想法未必和你一样,走的路未必也和你一样,就像郁蔼和袁瑛,同样一套剑法,他们使出来还有区别,你不要因为别人跟你不一样,就去否定他们,做人当如海纳百川,有容乃大,练武也是如此,心性偏狭者,成就境界终究有限,即便他登上巅峰,也不可能长久屹立不倒。”

In this world, there are many people—there are good people, and there are bad people, and there are even more people that cannot be easily divided into good or bad. Their way of thinking will be different from yours. The road they walk will be different from yours, just like Yu Ai and Yuan Ying. Though they performed the same sword technique, their execution was different. You shouldn’t deny someone just because of this. One’s conduct should be like the hundred rivers flowing into the sea—greatly tolerant. Practicing martial arts is like this as well: those of narrow-minded natures will have limited realms of success. Even if they ascend to the peak, they cannot remain there for long without falling.”

again, we see this recurring theme in 《千秋》 of a multiplicity of ways. according to Qi Fengge, aka one of the wisest and most powerful people in the narrative, there is more than one way to be correct, or in-tune with the Dao. as a result, Shen Qiao ends up validating Yan Wushi more than once, despite their pronounced differences in beliefs and morality:

晏无师哂道:“你也不必往本座头上堆高帽,我与宇文邕二人,不过是各取所需,我所做之事,只因自己想做,从来非为他人着想。”

沈峤:“即使心怀恶意,但若能达到善果,也算得道,不是么?”

Yan Wushi smiled, saying, “There’s no need to make me out better than I am. Yuwen Yong and I are simply taking what we need from each other. I only do things because I want to, not out of consideration to others.”

Shen Qiao said, “Even if one’s heart holds evil intent but one’s actions produce good results, that also counts as attaining the Dao, does it not?”

(chapter 44)

(Shen Qiao, I love you, but even I think that’s a bit extreme)

the POINT I’m trying to make here is that there are a multiplicity of Dao/Ways, and they’re all valid (unless you’re Sang Jingxing, in which case you’re dead), and the narrative affirms this regardless how individual readers might feel about it

the SECOND POINT I’m trying to make in this section (someone take this keyboard away from me oh my god) is that the main philosophical argument the narrative makes is that actually, none of the various schools/factions in 《千秋》—demonic, Daoist, Ruist, Buddhist—are sufficient on their own. the principles of Daoist non-action lead Shen Qiao towards Xuandu Mountain’s isolationism, which is definitively deconstructed and proven to be untenable throughout the events of the narrative; meanwhile, Ruism may seem attractively moral on the surface, but suffers from its adherence to rigidity and Han chauvinism (in the hands of Ruyan Kehui, that is). I’m... not sure there’s a central guiding principle to the demonic schools beyond following your own desires/doing whatever you want, but tbh we can also see the shortcomings of hedonism and personal gratification (short-sightedness, Shen Qiao murdering you with prejudice, etc). and, well—Buddhism’s barely in this book, we’ll let them off the hook for now

the entire driving force of the narrative, and the arc of its protagonist, is the inability to remain aloof and disconnected from the world one lives in. Shen Qiao is dragged into the dust of this mortal world—he has no choice but to interact, and in doing so, must learn the ways of his time. he has to reconcile his belief in the inherent goodness of human nature with the boundless cruelty and suffering he witnesses. and throughout his travels, he comes to the conclusion that a well-meaning, benevolent, and proactive figure in power would do the greatest good for the common people. for better or for worse, leaders (of states, of jianghu sects, of underground societies) possess great power to effect change; all Shen Qiao can do, then, is to find and support the best person for the job

to get into a debate about the feasibility of anarchy, especially anarchy in faux-historical medieval China, is beyond the scope of this post, but the point I’m trying to make is that the narrative supports a multiplicity of Dao/Ways to act, just as it supports Shen Qiao entering the chaos and clangor of the mortal world and gradually becoming involved in political change and social action despite potential conflicts with the principle of 无为 wu wei / non-action. so, no, I don’t find Shen Qiao’s actions and characters inconsistent with Daoism, especially Daoism as it is rendered in Meng Xishi’s jianghu

#hunxi thinks about QQ#(cups hands) Shen Qiao I love yoooou#do I think that a very interesting conversation could be had about the portrayal of unification as an unproblematic moral good#in both QQ and the Chinese tradition? yes! of course I do!#whole different conversation and dissertation topic though tbh!#look the Daodejing lends itself equally to authoritarianism and anarchy just sayin'#I think there's something to be said about the difference between Daoism as a personal philosophy vs. Daoism as a political philosophy#vastly beyond my ability and knowledge though#ah. this is 2.7k words. I am a clown and a 憨憨

33 notes

·

View notes

Note

jin ling / oyzz 32 pls!! :3c ❤️ u!!

so blocked on other things that I’m finally getting back to my prompts yay

If there was one thing Jin Ling had learned early on, it’s that fate hates him. His familial situation is good proof of this, though it is his love life that makes it the most obvious.

At twelve, he developed a crush on a girl from another sect who was staying in Jinlin Tai as a guest disciple. She was about two years older than him, pretty as the sunrise on Yunmeng’s lake, and strong enough to break a fierce corpse’s neck with her bare hands. It took Jin Ling weeks to decide how to talk to her, and when he finally did, an enormous pimple appeared right in the middle of his nose, disfiguring him. Jin Ling tried every remedy he could buy to bring his face back to normal, but only managed to make things worse. He never had a chance to talk to that girl, and she soon returned to her own sect, leaving Jin Ling completely heartbroken and ready to swear he would never love again.

A few months later, at thirteen, Jin Ling fell in love with a Yunmeng Jiang disciple. He tried to impress the older boy by showing off his diving skills. It was a common game for his uncle’s disciples, and Jin Ling had played it often enough as well. He liked to think he was good at it. His uncle had said he was good at it! And yet when he tried to dive in a very cool way to impress that one Jiang disciple, Jin Ling hit his head against something and nearly drowned. After that, he refused to come again to the Lotus Piers for ages, not until his uncle dragged him away from Jinlin Tai and forced him to go to a rather ill fated Night Hunt that changed his life.

If Jiang Cheng hadn’t taken Jin Ling to Dafan Mountain, he wouldn’t have met Mo Xuanyu. If he hadn’t met Mo Xuanyu and been rescued by him, he wouldn’t have had a debt toward him and helped him run away from Jiang Cheng in Qinghe. If he hadn’t angered his uncle like that, Jin Ling wouldn’t have needed to lay low for a while, and he wouldn’t have stumbled upon a group of juniors from various sects. And then…

Then he wouldn’t have met Ouyang Zizhen.

Meeting Ouyang Zizhen had been both a blessing and a curse. Well. Mostly a curse, actually.

Jin Ling, fourteen, with a bad ego, an even worse temper, and about to be hit in the face by more family secrets than any fourteen years old boy ought to have dealt with, just didn’t need the added horror of being in love again. It really was unfair and needlessly cruel of Ouyang Zizhen to be just that perfect, and handsome, and eloquent, and kind, and…

For a good while, Jin Ling managed to keep himself under control. He had bigger things to worry about, such as not getting killed by Xue Yang, or not getting killed by fierce corpses, or not getting killed by his uncle, and also discovering that his family was an even bigger mess than he’d ever realised, which was really saying something. And yet even with all those much more important things to keep him busy, Jin Ling couldn’t stop thinking about Ouyang Zizhen’s smile, his heartfelt tears for that ghost girl in Yi-City, the fierce way he’d fought in the Burial Mounds, how he hadn’t hesitated to stand up for Wei Wuxian… and also how he had firmly sided with the Ghost General against Jin Ling.

It really was Jin Ling’s fate to be eternally unlucky in love, he’d thought after that. And then, when he’d learned what kind of men his uncle and grandfather were, he’d figured that maybe his bad luck was just so his family would end with him, and stop making a mess of things.

And yet, in spite of being clearly cursed with the worst luck in the world, a few weeks after suddenly becoming sect leader, Jin Ling had received a letter. Not just any letter, either, but an invitation to join some other boys on a Night Hunt, among which Ouyang Zizhen who had been the one writing that invitation. Jin Ling’s broken heart had mended on the spot, delighted to find that Ouyang Zizhen had thought of him for this. Considering their last interaction hadn’t been too great, it had to mean something if he was invited, right?

It took some effort to convince the Jin elders, but in the end Jin Ling was sect leader now, and so nobody could really stop him from going wherever he pleased. He flew as fast as he could after leaving Jinlin Tai, and arrived less than a day later at the residence of the Baling Ouyang sect where Ouyang Zizhen welcomed him with that beautiful smile of his.

“You arrived a little early,” Zizhen said as he guided Jin Ling inside. The Baling Ouyang sect wasn’t very big, nor was it very rich, so the place they lived in was not much when compared to Jinlin Tai. Yet because Zizhen was there, Jin Ling found that simplicity charming, and that smallness cozy. “My father has a guest with him,” Zizhen explained, “but they’ll be leaving to their own Night Hunt soon enough. Well, they say Night Hunt… mostly Yao zongzhu and him like to head out and find a nice place to drink without my mother and auntie Yao bothering them.”

Jin Ling grimaced. Sect Leader Yao wasn’t very high on the list of people he liked to deal with. Zizhen noticed his expression of course, and laughed.

“I know, I know,” he said, leading Jin Ling inside a reception room decorated with rustic charm. Or at least, so Jin Ling chose to call it. “Jin zongzhu, just wait here and…”

“You can call me Jin Ling.”

“Wouldn’t that be disrespectful?” Zizhen asked. “I imagine people already give you a hard time for being so young, I don’t want to be too familiar and undermine your authority.”

Jin Ling’s poor heart started beating faster in his chest. Ouyang Zizhen really was too perfect, kind, courteous, clever… Even other kids in Lanling Jin were sometimes making a fuss about using Jin Ling’s title, especially those older than him, but here was Ouyang Zizhen, worrying about his image!

“I don’t care what others think,” Jin Ling said with all the haughtiness of a teenager with too much power. “You are my friend, so you can call me as you like.”

“Then maybe Jin Rulan?” Zizhen suggested. “It would be less…”

“You can call me anything you like, except that,” Jin Ling promptly corrected.

“Ah. Well, Jin Ling it is then,” Zizhen said, giving in. “Listen, I do have to tell my father that you’re here, or he’ll be cross later. He’ll probably want to drop by, but I’ll do my best to make sure it’s short. And then… it’s still early, and I don’t expect anyone else to arrive until tomorrow, so we could try to have some fun in town together?”

Jin Ling eagerly nodded at that proposition. Time alone with Zizhen sounded like the best thing ever. If he played this right…

While Zizhen left to go see his father, Jin Ling started pacing the room, trying to plan a course of action for the evening. He didn’t know what they might end up doing, since he’d never spent any time in Baling before, but surely he could hazard a few guesses. They’d have to eat, for example, and Jin Ling would of course offer to pay. Zizhen might protest, being the host, but Jin Ling would use the rank card and treat the other boy to any and all delicacies could be found in these parts. And surely there were interesting sights to see, or a scenic place perhaps? If they could go walk somewhere pretty, then Jin Ling would just have to take Zizhen’s hand and…

Or would it be better to talk about his feelings before? Jiang Cheng always said it was better to be direct in those things, so there could be no misunderstandings. Of course Jiang Cheng was terminally single, so perhaps not the best example to follow. But directness had seemed to work pretty well for Wei Wuxian and Lan Wangji in that temple in Yunping, so clearly there was a merit to that idea. But how to confess? Zizhen was an eloquent person with a poetic turn of mind, whereas Jin Ling… well, Jin Ling knew where his strength laid, and it definitely wasn’t in eloquence. It ran in the family, apparently.

On both sides.

It was fine though. There was no shame in having a practical turn of mind. When they were married, Zizhen would be eloquent in his stead, and Jin Ling would do the accounting, and they’d be a perfect team. For that reason, it made sense that his declaration should be a reflection of his personality: direct and to the point. He just needed to stay calm, find the right words, politely express his intentions, and everything would be fine.

Jin Ling just needed to keep his cool.

All things considered, he should have remembered that this was not something he’d ever been good at.

So when he saw the door start to open again, when he caught a first glimpse of Zizhen’s beautiful smile, of his elegant eyes, Jin Ling panicked.

“Zizhen, I like you a lot!” he shouted. “Please allow me to court you!”

Ouyang Zizhen froze on the spot, while the door finished opening, revealing sect leader Ouyang and sect leader Yao behind the teenager, both of them staring at Jin Ling in shock.

Realising what he’d done, Jin Ling nearly fainted.

This time his reputation was ruined for ever, and he was never going to live it down.

33 notes

·

View notes

Video

tumblr

The Untamed/陈情令 Rewatch, Episode 4 (spoilers for everything)

(covers mainly MDZS chaps 13 and 14)

WangXian meter: 🐰🐰🐰🐰🐰🐰🐰🐰🐰🐰🐰🐰🐰🐰🐰

(a 🐰 is earned every time there is a WangXian scene or even when they’re just thinking of each other…more than one 🐰 can be given based on the level of WangXian-ness in a scene)

I loved and enjoyed all of Wei Ying’s “Notice me Wangji-senpai" moments in this episode, but my favorite has to be the one above: the way he tried to play off Lan Zhan totally ignoring him by blaming the other man’s hearing makes me laugh out loud every time I watch this episode. It’s just too adorable. Even though Lan Zhan is clearly still annoyed with him, I like how it’s also obvious that Wei Ying is slowly but surely burrowing his way into his psyche and taking hold there by either not leaving him alone or just being himself which is ample to constantly draw Lan Zhan’s attention to him. It‘s as if Lan Zhan’s life was a calm pond and Wei Ying was a beautiful, lively carp that suddenly decided to just jump into his waters without permission, taking liberties by swimming and splashing around, basically causing ruckus in every corner of his pool. Naturally, Wei Ying’s actions perturbs Lan Zhan to no end at first, but at the same time, he is also leaving an undeniable impression, so that eventually, when this carp leaves Lan Zhan’s pond, he can’t help but constantly think of Wei Ying and even miss his disruptive presence, thus naturally paving the way for the escalation of his affections that follow later on.

Whereas with Wei Ying, I think he simply enjoyed irritating this fuddy-duddy at first, but eventually, his light-hearted teasing probably became just a little more meaningful and he started looking forward to getting a reaction out of Lan Zhan because it provided him with genuine joy and satisfaction, until those feelings grew into just joy from being around the other man and interacting with him.

Ultimately that’s a big reason why I love their relationship: the development and progression of their feelings for each other makes a lot of sense to me. The phrase “opposites attract” has never been more applicable in terms of Wei Ying and Lan Zhan, but at the same time, they still share enough things in common—such as their moral code and belief system—that makes them absolutely just perfect for each other. I can imagine a future for them right from the start, whereas with other couples in stories, regardless of their sex, I’ve had difficulty believing they should be together other than because the plot requires them to be. I think the drama really succeeded in showing us why it’s completely logical that these two people would be drawn to each other, that they almost can’t help but be drawn together, by actually showing us all these little precious moments between them as they occurred, which the novel for the most part only described in an after-the-fact manner. While subtlety has its merits too, I do appreciate the more clearly illustrated path The Untamed decided to take for WangXian.

Along those lines, I also appreciated how CQL chose to show us the first time Lan Xichen and Jin Guangyao met and their instant connection. Honestly, when I first saw this moment…

I immediately thought they were going to be a couple too, like Wei Ying and Lan Zhan, and I was totally on board, until I found out from reading comments here and there that I shouldn’t be because this ship was bad news. I was disappointed of course and even tried to withstand its alluring call for a while, especially after reading the book and finding out exactly why this wasn’t a ship I wanted to board since it was on a one-way ticket to hell and heartbreak basically. But the drama just made it so damn hard to resist, and before I knew it, I was lowkey hooked. Much like with WangXian, I was surprised at how much the show was getting away with in terms of XiYao:

I mean, big bro Xichen totally stroked Meng Yao’s finger there, right? First time I saw that, I remember rewinding a few times just to check and and make sure and if it’s just an optical illusion, that’s a damn convincing trick. Amusingly enough I thought at first Wei Ying was seeing the same thing and was reacting in disbelief to that moment, until I realized from his angle, there’s no way he could have seen that small gesture and he was just responding to that (ugly) incense pot.

After finishing the series, I have to admit I’m pretty much a full-on XiYao-shipper now, which is really out of character for me because I usually prefer ships with happy endings. I have to blame, or rather, give credit to the two actors portraying LXC and JGY (Liu Haikuan and Zhu Zanjin, respectively) for conjuring up these feelings in me because they had so much chemistry together, which honestly at times rivaled that of Xiao Zhan and Wang Yibo’s chemistry. I just love how LXC’s expression softens every time he interacts with JGY and even from their first meeting, it’s obvious there were genuine feelings of respect and gratitude behind Meng Yao’s reaction to LXC.

Take the moment above as an example: the extreme admiration emanating from JGY after seeing LXC exhibit his fluting powers had to be for real since there was no reason to react just for Nie Huaisang’s sake. I can totally imagine hearts fluttering all around him as he looked upon XiChen with those wide, innocent-seeming puppy eyes of his. And when he bade his farewell to big bro later on in the episode, I loved how the camera lingered on LXC’s hands as Meng Yao moved away after saluting him, just to reiterate the intimacy of their brief physical contact.

I also appreciated the small, seemingly trivial moments before and after he meets up with LXC in that scene, where Meng Yao is first ignored by the two male sect disciples walking by him and then later on by two female disciples. Contrast that with how LXC immediately praises Meng Yao and recognizes him as his peer from the get go, going so far as to refer to himself by his own name (“Xichen”) just to reinforce their equality, it’s no wonder JGY was instantly drawn to him. I would go so far as to say he probably fell for LXC right from the start; doesn’t even matter if it might be only in the platonic sense, man was smitten no matter how anyone chooses to categorize his feelings.

XianQing? No thank you

When I first watched this episode, I still had the stormy cloud of fear that Wen Qing would eventually be the love interest that comes in between Wei Wuxian and Lan Wangji hanging over me due to some rumors I came across prior to even watching the show. As a result, every time Wen Qing and WWX would have a scene together, I would view it with trepidation as I was certain it was yet another building block to something undesirable, with the ultimate goal of mutating the relationship at the core of MDZS. If I’m going to be honest, I don’t think I was even able to rest easy until after Wen Qing’s passing and knowing for certain that the “danger period” was finally over, even though I had already grown to like her character. I still have complaints about how they altered her personality for the live action, but at least now, when I watch the scenes she shares with Wei Ying, instead of being filled with anxiety, I am actually more fascinated. I can still see the ghost of what Team CQL had initially intended with Wen Qing and WWX in a lot of their scenes together, before the fans’ uproar thankfully forced the producers to change their minds and stick with the source material. This scene wasn’t one of those moments, but with revisiting each episode, I actually look forward to picking out which scenes were feeding into their ship because of the way they were shot and how the two actors were directed to perform during the scene, especially Meng Ziyi. I’m glad I can actually sit back and have fun with all of this now.

XianNing? I can’t

I can see why some folks support this ship, and upon first viewing I thought this was a cute moment as well, but of course, I simply can’t go there since my heart already belongs to WangXian. And now, after having read the novel, all I could think about is how much I wish we got the archery contest at the Cultivation Conference. I’m glad we got to see it depicted in the donghua; it was as amazing as I hope it would be, but it’s a shame we didn’t get to see it in the drama. Since the producers had mentioned releasing specials of extra scenes that they couldn’t fit into the flow of the show, I hope the archery contest will be one of them. I don’t know where it would fit in in the timeline though…I guess it could happen while they were all held hostage at Nightless City, so the reason for the archery contest will have to be changed, but then maybe that’s the impetus for Wen Chao’s decision to force everyone on that dangerous quest to the Xuanwu cave: he’s so pissed off at losing at archery on his own turf that he decides to try to get all the sect kids killed. Either way, I hope we get to see the contest in live action form one day.

Wei Wuxian is so smart

I loved this scene. I love how WWX schooled everyone with his inventive fourth reason. He’s so awesome. That’s really all I wanted to say about it.

Random Bits of Randomness

I don’t think there’s anything wrong the color function on my tv, so please explain to me how that can be considered “purple” in any universe??

All I could think about in this scene is how disgusting that fish must have tasted cuz it looked awful, and I think Xiao Zhan even mentioned in an interview that it was gross. What probably made it taste worse was the fact that he kept on eating it from the stomach side, which can be really bitter. I think Wang Zhuocheng (Jiang Cheng) was eating it from the same side as well and I just can’t help grimacing every time I see this moment.

Odds and Ends:

I don’t really have any questions from this episode, but I did wonder if Wen Qing ever actually attended classes while she was at Cloud Recesses or did she just spend all of the time wandering the back hills, throwing her needles at barriers, cuz that’s not suspicious AT ALL. Unless I just happened to have missed her every single time in class, even though you would think it’s easy to spot her red in a sea of white…if that’s the case then I probably need to get my eyes checked.

Also, I wish we got to see Shijie draw her sword. She carried it around in the beginning, but I’m kinda bummed that we never saw her actually use it. I’m sure she is completely capable and would’ve looked just as badass as the boys.

And bless Uncle Lan for his brilliant idea of making Lan Zhan enforce the disciplinary action on Wei Ying, thereby allowing the boys to have valuable alone time in the library pavilion to further nurture their bond. In retrospect he probably regrets that decision, but as far as I’m concerned, that’s one of his best one he’s ever made.

#The Untamed#陈情令#Spoilers#WangXian#XiYao#Untamed Rewatch#Mo Dao Zu Shi#CQL#MDZS#魔道祖师#Grandmaster of Demonic Cultivation#Wei Ying Wei Wuxian#Lan Zhan Lan Wangji#Lan Xichen#Jin Guangyao#Wen Qing#XianQing#Wen Ning#XianNing#Jiang Cheng#Jiang Yanli#Lan Qiren

109 notes

·

View notes

Text

People might object that algorithms could never make important decisions for us, because important decisions usually involve an ethical dimension, and algorithms don’t understand ethics. Yet there is no reason to assume that algorithms won’t be able to outperform the average human even in ethics. Already today, as devices like smartphones and autonomous vehicles undertake decisions that used to be a human monopoly, they start to grapple with the same kind of ethical problems that have bedevilled humans for millennia.

For example, suppose two kids chasing a ball jump right in front of a self-driving car. Based on its lightning calculations, the algorithm driving the car concludes that the only way to avoid hitting the two kids is to swerve into the opposite lane, and risk colliding with an oncoming truck. The algorithm calculates that in such a case there is a 70 percent chance that the owner of the car - who is fast asleep in the back seat - would be killed. What should the algorithm do?

Philosophers have been arguing about such ‘trolley problems' for millennia (they are called 'trolley problems’ because the textbook examples in modern philosophical debates refer to a runaway trolley car racing down a railway track, rather than to a self-driving car).“ Up until now, these arguments have had embarrassingly little impact on actual behaviour, because in times of crisis humans all too often forget about their philosophical views and follow their emotions and gut instincts instead. One of the nastiest experiments in the history of the social sciences was conducted in December 1970 on a group of Students at the Princeton Theological Seminary, who were training to become ministers in the Presbyterian Church. Each student was asked to hurry to a distant lecture hall, and there give a talk on the Good Samaritan parable, which tells how a Jew travelling from Jerusalem to Jericho was robbed and beaten by criminals, who then left him to die by the side of the road. After some time a priest and a Levite passed nearby, but both ignored the man. In contrast, a Samaritan - a member of a sect much despised by the Jews - stopped when he saw the victim, took care of him, and saved his life. The moral of the parable is that people’s merit should be judged by their actual behaviour, rather than by their religious affiliation.

The eager young seminarians rushed to the lecture hall, contemplating on the way how best to explain the moral of the Good Samaritan parable. But the experimenters planted in their path a shabbily dressed person, who was sitting slumped in a doorway with his head down and his eyes closed. As each unsuspecting seminarian was hurrying past, the 'victim’ coughed and groaned pitifully. Most seminarians did not even stop to inquire what was wrong with the man, let alone offer any help. The emotional stress created by the need to hurry to the lecture hall trumped their moral obligation to help strangers in distress.

Human emotions trump philosophical theories in countless other situations. This makes the ethical and philosophical history of the world a rather depressing rale of wonderful ideals and less than ideal behaviour. How many Christians actually turn the other cheek, how many Buddhists actually rise above egoistic obsessions, and how many Jews actually love their neighbours as themselves? That’s just the way natural selection has shaped Homo sapiens. Like all mammals, Homo sapiens uses emotions to quickly make life and death decisions. We have inherited our anger, our fear and our lust from millions of ancestors, all of whom passed the most rigorous quality control tests of natural selection.

Unfortunately, what was good for survival and reproduction in the African savannah a million years ago does not necessarily make for responsible behaviour on twenty-first-century motorways. Distracted, angry and anxious human drivers kill more than a million people in traffic accidents every year. We can send all our philosophers, prophets and priests to preach ethics to these drivers - but on the road, mammalian emotions and savannah instincts will still take over. Consequently, seminarians in a rush will ignore people in distress, and drivers in a crisis will run over hapless pedestrians.

This disjunction between the seminary and the road is one of the biggest practical problems in ethics. Immanuel Kant, John Swart Mill and John Rawls can sit in some cosy university hall and discuss theoretical problems in ethics for days - but would their conclusions actually be implemented by stressed-out drivers caught in a split-second emergency? Perhaps Michael Schumacher - the Formula One champion who is sometimes hailed as the best driver in history - had the ability to think about philosophy while racing a car; but most of us aren’t Schumacher.

Computer algorithms, however, have not been shaped by natural selection, and they have neither emotions nor gut instincts. Hence in moments of crisis they could follow ethical guidelines much better than humans - provided we find a way to code ethics in precise numbers and statistics. If we teach Kant, Mill and Rawls to write code, they can carefully program the self-driving car in their cosy laboratory, and be certain that the car will follow their commandments on the highway. In effect, every car will be driven by Michael Schumacher and Immanuel Kant rolled into one.

Thus if you program a self-driving car to stop and help strangers in distress, it will do so come hell or high water (unless, of course, you insert an exception clause for infernal or high-water scenarios). Similarly, if your self-driving car is programmed to swerve to the opposite lane in order to save the two kids in its path, you can bet your life this is exactly what it will do. Which means that when designing their self-driving car, Toyota or Tesla will be transforming a theoretical problem in the philosophy of ethics into a practical problem of engineering.

Granted, the philosophical algorithms will never be perfect. Mistakes will still happen, resulting in injuries, deaths and extremely complicated lawsuits. (For the first time in history, you might be able to sue a philosopher for the unfortunate results of his or her theories, because for the first time in history you could prove a direct causal link between philosophical ideas and real-life events.) However, in order to take over from human drivers, the algorithms won’t have to be perfect. They will just have to be better than the humans. Given that human drivers kill more than a million people each year, that isn’t such a tall order. When all is said and done, would you rather the car next to you was driven by a drunk teenager, or by the Schumacher-Kant team?

The same logic is true not just of driving, but of many other situations. Take for example job applications. In the twenty-first century, the decision whether to hire somebody for a job will increasingly be made by algorithms. We cannot rely on the machine to set the relevant ethical standards - humans will still need to do that. But once we decide on an ethical standard in the job market - that it is wrong to discriminate against black people or against women, for example - we can rely on machines to implement and maintain this standard better than humans. A human manager may know and even agree that it is unethical to discriminate against black people and women, but then, when a black woman applies for a job, the manager subconsciously discriminates against her, and decides not to hire her. If we allow a computer to evaluate job applications, and program the computer to completely ignore race and gender, we can be certain that the computer will indeed ignore these factors, because computers don’t have a subconscious. Of course, it won’t be easy to write code for evaluating job applications, and there is always a danger that the engineers will somehow program their own subconscious biases into the software. Yet once we discover such mistakes, it would probably be far easier to debug the software than to rid humans of their racist and misogynist biases.

We saw that the rise of artificial intelligence might push most humans out of the job market - including drivers and traffic police (when rowdy humans are replaced by obedient algorithms, traffic police will be redundant). However, there might be some new openings for philosophers, because their skills - hitherto devoid of much market value - will suddenly be in very high demand. So if you want to study something that will guarantee a good job in the future, maybe philosophy is not such a bad gamble. Of course, philosophers seldom agree on the right course of action. Few 'trolley problems’ have been solved to the satisfaction of all philosophers, and consequentialist thinkers such as John Stuart Mill (who judge actions by consequences) hold quite different opinions to deontologists such as Immanuel Kant (who judge actions by absolute rules). Would Tesla have to actually take a stance on such knotty matters in order to produce a car?

Well, maybeTesla will just leave it to the market. Tesla will produce two models of the self-driving car: the Tesla Altruist and the Tesla Egoist. In an emergency, the Altruist sacrifices its owner to the greater good, whereas the Egoist does everything in its power to save its owner, even if it means killing the two kids. Customers will then be able to buy the car that best fits their favourite philosophical view. If more people buy the Tesla Egoist, you won’t be able to blame Tesla for that. After all. the customer is always right.

This is not a joke. In a pioneering 2015 study people were presented with a hypothetical scenario of a self-driving car about to run over several pedestrians. Most said that in such a case the car should save the pedestrians even at rhe price of killing its owner. When they were then asked whether they personally would buy a car programmed to sacrifice irs owner for the grearet good, most said no. For themselves, they would prefer the Tesla Egoist.

Imagine the situation: you have bought a new car, bur before you can start using it, you must open the settings menu and tick one of several boxes. In case of an accident, do you want the car to sacrifice your life - or to kill the family in the other vehicle? Is this a choice you even want to make? Just think of the arguments you are going to have with your husband about which box to tick.

So maybe the state should intervene to regulate the market, and lay down an ethical code binding all self-driving cars? Some lawmakers will doubtless be thrilled by the opportunity to finally make laws that are always followed to the letter. Other lawmakers may be alarmed by such unprecedented and totalitarian responsibility. After all, throughout history the limitations of law enforcement provided a welcome check on the biases, mistakes and excesses of lawmakers. It was an extremely lucky thing that laws against homosexuality and against blasphemy were only partially enforced. Do we really want a system in which the decisions of fallible politicians become as inexorable as gravity?

- Yuval Noah Harari, The philosophical car in 21 Lessons for the 21st century

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Comments on “Where’s the Winter Palace”

I have two main critiques of this interesting but, I argue, ultimately unpersuasive essay on the Marxist-Leninist movement in the US. This note grew out of a Facebook comment, and it presumes familiarity with the general subject as well as the essay linked above. I left aside several other critiques which were made by other people on the thread, so this is an incomplete critique.

First, I found the critique of line-centrism (laid out in "Dogmatism and 'Line'") less than persuasive; I thought it misidentified the cause of the NCM’s failing in the first place (here I disagree with Max Elbaum who is the original source for this claim); applies with far less force to the Marxist-Leninist movement at present than it did to the NCM; and, finally, is unrealistic in the sense that it takes an unfortunate truth about large group organization, Marxist-Leninist or otherwise (that the determination of some kind of a minimal line and the holding of it is crucially necessary to effective politics and will also never satisfy every individual party member entirely) and makes it an avoidable, volitional failure borne of dogmatism (whereas I think it is just a feature of doing politics as such); I also think that the argument that certain issues are simply not ones on which lines should be tightly drawn (e.g., imperialist wars of aggression) is unpersuasive.

Second, I thought that the attempted historicization of Marxism-Leninism (i.e., the reading of it as an analysis which was true “then” but is now “outdated Cold War politics”) was also unpersuasive. I don’t think that the authors really argued for this point with as much evidence as such a strong claim merits; I do take up, in detail, what evidence they do provide at the end of “The Sect System”, and I argue that this evidence does not provide a foundation for their claims. I also address some of their specific study suggestions for Marxist-Leninists, which I argue are inconsistent and, in some cases, difficult or impossible to reconcile with Lenin’s work or the Third International tradition generally.

To the first point. I’ll set aside the first sub-point (about the NCM) since that’s something of a different topic. On the second point, I think, viewed historically, the three organizations which the authors are talking about are far less strict about adherence to lines on every conceivable issue than during the NCM, less strict than the Trotskyist movement (from its inception to present), and, to some degree, less strict than the official CP movement; the movement in all of those subsections of the left and on the left, generally, during the 1930s-1980s was substantially larger in the US than it is now. So, I think this provides some prima facie evidence that adherence to a strict line is, at the very least, not a huge brake on the size and influence of the left, all else equal. The NCM failed, for sure, and its genuinely ouroboros-character with regard to line-struggle clearly contributed to that (although again, I think the emphasis on that is overstated); but, the fact that line-struggle is now far less heated and that the movement is smaller means that this can’t be the only, or primary, cause (WWP goes far out of its way to avoid polemics against other groups, e.g.—one would never see from WWP the kind of personalization of politics that was common during the NCM, such as the adoption of hyper-specific name-based epithets or condemning the line of fellow leaders of tiny groups, by name, in print, as, quite literally, “evil”). I can't speak for all the groups in question, but certainly the ones I'm most familiar with have no restrictions on members disagreeing with assessments of other members on a great variety of questions—it's just disagreements which would threaten unity of action which are prohibited (I think it's perfectly reasonable to prohibit people from publicly saying things like "I fundamentally think this strike that we're supporting as a group is wrong"—there just isn’t a point in having a political organization that can’t agree on some baseline goals and strategies, in my view). For some groups, that could well reasonably include discussions about China; if one believes that the particular method of organizing socialist revolution in China ineluctably led to a counterrevolution or ineluctably led to a socialist-developmental state, then it would be good to avoid or pursue those methods (or at least learn the lessons that can be learned from them and apply them to a different context)—that actually would be a question of great importance (and, in a way, the author sare implicitly entering into that debate without intending to by arguing that the experience of those countries is probably irrelevant—that is “a position” in that debate, in my view). [I should acknowledge that this last point is also laid out in a comment on the original post concerning Cuba, made by one Daniel Sullivan].