#vassilissa

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

139 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hello Hellooooo everyone !

Not return for talking about my Marvel verse (sorry)

But i want to yap about my actual real writing project... My rewrite of the Russian fairy tale Vassilissa The Beautiful

I make a lot of art about but writing... eh eh, it's not that simple unfortunately

But.

Look at the protagonist : Vassilissa and Tsar Alexei

#writers on tumblr#writing#writerscommunity#russian fairy tailes#baba yaga#vassilissa the beautiful#art#writers art#lostnighterarts

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

As someone who was deeply over the whole Kagapol hype train the schadenfreude is delightful. Definitely a highlight of the season so far.

0 notes

Text

"The one who defied time" Happy (late-) birthday Vassilissa! (02/20)! I love my daughter so very much 🥹

#my art#my artwork#illustration#digital art#illustrator#original art#digital painting#digital artwork#digital illustration#original character#illustrators on tumblr#digital drawing#artwork#art

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

Soft-tagged by both @thetreasurechest and @lover-of-the-starkindler - thank you!

The rules are to list 10 of your favorite female characters from 10 different fandoms, and then tag 10 different people.

Generally just going with ten great female characters.

Artemis Asa-Smith from The Paradoxes of Mr. Pond by G. K. Chesterton.

Kate Nickleby from Nicholas Nickleby by Charles Dickens.

Jane Bennet from Pride and Prejudice by Jane Austen.

Kateri Kovach from The Fairy Tale Novels by Regina Doman.

Arabella Strange from Jonathon Strange & Mr. Norrell by Susanna Clarke.

The Baker from The Woman who Flummoxed the Fairies (I'm familiar with the version by Sorche Nic Leodhas, nicely summarised in the link).

Vassilissa from Staver and his Wife Vassilissa.

Becky from Striped Ice Cream by Joan M. Lexau.

Jaylah from Star Trek Beyond.

Leonore from Fidelio by Ludwig van Beethoven (libretto by Joseph Sonnleithner).

Leaving an open tag for anyone who would like to do this!

#Don't want to make this too long but will happily talk about any or all of these characters if anyone wants#asks#Thank you!#thetreasurechest#lover-of-the-starkindler

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

I will not be doing that list thing. Look at my letterboxd lists though.

Favourites of 2025 so far: Nosferatu the Vampyre, Once Were Warriors, Whale Rider, The Brother from Another Planet, Police Story, Ganja & Hess, Baby Boy, Hustle & Flow, Vassilissa Mikulishna, Blue Puppy, Eve’s Bayou. Also give me suggestions for lgbt movies, i am trying to compile a watchlist,

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

VASSA IN THE NIGHT by Sarah Porter

RELEASE DATE: Sept. 20, 2016

An enthralling, magic-tinged read about home, family, love, and belonging.

Brooklyn is an enchanted kingdom where most aspire to arrive—most of it, that is, the exception being Vassa’s working-class neighborhood, where the white teen lives with her stepmother and stepsisters, struggling with the feeling that she does not belong.

In Vassa’s neighborhood, magic is to be avoided, and the nights have mysteriously started lengthening. Baba Yaga owns a local convenience store known for its practice of beheading shoplifting customers, but it seems that even the innocent are susceptible to this fate. One night, after an argument with a stepsister, Vassa goes out on an errand to Baba Yaga’s store—one she knows may be her last. With her magic wooden doll, Erg, a gift from her dead mother, Vassa is equipped with some luck that she will very much need. Erg is clever and brazen, possessing both an insatiable appetite and a proclivity to swipe the property of others. But will Erg’s magic be enough to help free Vassa from Baba Yaga’s clutches and possibly her entire Brooklyn neighborhood from the ever increasing darkness? Vassa’s narration is smart and sassy but capable of wonder, however familiar she’s become with Brooklyn’s magic. In this urban-fantasy take on the Russian folk tale “Vassilissa the Beautiful,” Porter weaves folk motifs into a beautiful and gripping narrative filled with magic, hope, loss, and triumph. An enthralling, magic-tinged read about home, family, love, and belonging.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

J'arrive à dessiner !

Loreley et Vassilissa

#artists on tumblr#french#drawing#my art#oc art#oc artist#oc artwork#original character#original art#traditional art#artwork#art#art style#character art#oc rp

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

222 notes

·

View notes

Text

Vassilissa and Alexei as « The Kiss » By Klimt❤️

I love them so much, I can't wait to share their stories with you🫶🏻

And if you want to see the NSFW version, go on patreon !

1 note

·

View note

Text

STAVER AND VASSILISA

@professorlehnsherr-almashy @themousefromfantasyland @softlytowardthesun @tamisdava2 @natache @princesssarisa @shelleythesapphic @the-gentile-folklorist @thealmightyemprex @greektragedydaddy @lord-antihero @lioness--hart

(A russian folktale)

Grand Duke Vladimir sat banqueting in the hall of his castle, surrounded by princes and warlords and all the heroes of his realm. The feasting continued for many hours, with plenty to eat and drink, and music to lighten the saddest heart.

After the heroes had eaten and drunk their fill, they began to boast, and no one boasted louder than the grand duke himself. Nowhere, he insisted, was there more gold, nowhere more silver, nowhere greater heaps of pearls than here in his fine palace. And where could one find a woman more beautiful than his own wife, the lovely Apraksiya? This was too much for young Prince Staver.

“Listen to him boasting,” he murmured to his neighbor. “He thinks this stone box of his should be called a castle. My own castle is so large, it’s better to ride through it on horseback than to walk. The floors are paved with silver, and the walls are built from bricks of gold. I have so many chests of pearls and diamonds and rubies, they could fill a room as big as this hall. But my greatest treasure of all is my wife, Vassilissa. Her hair is like that of a fox, her eyes as sharp as a falcon's eyes. Not only is she a superb housekeeper, she’s also stronger than any man in this hall.” While Staver was speaking, the hall grew quiet, and he looked up to see the grand dulce’s eyes upon him. His face was red with anger, and he bellowed like a wild boar, “So, Staver Godinovitch, you thinly you can insult me and humiliate me here in my own hall? Enough of your empty talk, you blithering idiot. Throw him in the dungeon! Then ride to his castle, seal it up with all his treasure chests within, and bring me the beautiful Vassilissa. Bring her to me, Grand Duke Vladimir!” Staver was seized and thrown into the dungeon. Then ten of Vladimir's warlords rode off to seal up his castle and bring back Vassilissa, but Staver’s friend Mikhail rode ahead of the others to warn Vassilissa of the grand duke’s order.

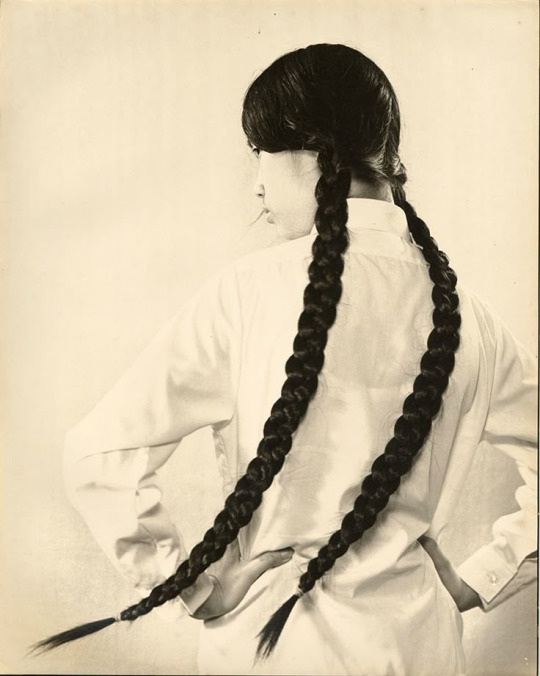

Vassilissa tucked her long red hair under her helmet and dressed herself as a man. She tools a stout sword from Staver’s armory and sharpened her quiverful of arrows. Then she mounted her black stallion and, with twelve other men, set out for the grand duke’s castle. Halfway there, she met the warlords who had been ordered to take her prisoner. They didn’t recognize her and asked her where she was going.

“I’ve come in the name of the Khan of the Golden hordes,” Vassilissa answered. “My men and I are here to remind brand Duke Vladimir that he owes the khan tribute for the last twelve years. We have orders to tame many chests of gold back to the khan. And where are you riding?”

“We’re going to Staver’s castle, to seal it up and carry his wife, Vassilissa, to the grand duke,” said one of the warlords.

“We have just passed Staver’s castle. Vassilissa is not there. She has hidden away,” she told them.

So the band of warlords galloped back to the grand dulce’s castle and reported that Vassilissa was missing and that the ambassador from the wan of the Golden Hordes was on his way to exact tribute. When Vassilissa arrived at the castle, everyone assumed she was the ambassador and treated her with great courtesy. But Vladimir’s wife, Apraksiya, was watching the new arrival carefully.

“That’s not the ambassador from the Khan,” she whispered to her husband.

“Can’t you tell that it’s a woman? I think that's Staver’s wife, Vassilissa. Loom at how he walks!”

The duke observed the young ambassador carefully. Perhaps his wife was right. He decided to hold a wrestling contest to test the ambassador’s strength. II this was a woman, she would surely lose.

“In this country, it is our custom that all visitors be given the opportunity to test their strength against my warlords,” Vladimir told the ambassador.

“If it pleases your excellency, we shall now hold a wrestling contest.”

Seven of his warlords immediately rose from the banqueting tables to challenge the disguised Vassilissa. The first man stepped forth. Vassilissa threw him so hard that he had to be carried from the hall. The second had seven of his ribs broken by a single blow of her fist. The third had three of his vertebrae dislocated and had to crawl from the hall on his hands and knees. The rest of the challengers fled, not wishing to be humiliated before all their comrades. Vladimir trembled with frustration and spat on the floor.

“Your hair may be long,” he muttered to his wife, “but you haven’t a brain in your head. Why did you tell me he was a woman? My court has never seen a hero with such strength!”

Apraksiya raised her eyebrows.

“Look at that skin,” she urged her husband.

“Is that the skin of a man? And why does she always wear a helmet? Could she be hiding her long hair beneath it?”

Vladimir glared at his wife angrily. He blamed her for making him look like a fool. But he couldn’t help wondering if she might be right, and he decided to put the khan’s envoy to another test.

“I see you are very strong,” he congratulated Vassilissa, slapping her heartily on the back.

“Now perhaps you would like to prove your skill at archery.”

With these words, he led his court to an open meadow behind the castle. All of Vladimir’s men shot their arrows into an old oak that stood at the far end of the field. Each time it was hit, the oak tree swayed as if it were caught in a gust of wind. But when Vassilisa shot her arrow, the bowstring sang and the mighty oak shattered into a thousand pieces.

The men were dumbfounded. Vladimir spat for the second time.

“Look at that oak tree,” he hissed at Apraksiya.

“We’ve never seen such an archer before, and you believe he’s a woman. I shall challenge him myself and see if he’s also supreme at chess.”

Vladimir and Vassilissa now sat at the grand duke's chess table and played chess with chessmen carved from the finest marble. Vassilissa won the first game, and also the second, and the third. She laughed, for the duke had played for high stakes.

Then she pushed the chessboard aside.

“Enough of this foolishness,” she declared.

“I didn’t come here to waste my time playing games. What about the tribute you owe the great khan? You haven’t paid for twelve whole years. I demand two chests of gold every year. Produce them here and now! The Khan of the Golden Hordes refuses to wait any longer.”

Then Vladimir began to whine.

“Times are hard, you know. The harvest was poor this year and last. Merchants are doing little business, trade is slow, and we haven’t collected much in taxes. How can I pay? Couldn’t the great khan wait another year?”

Vassilissa tapped her fingers impatiently on the chess table.

“He’s already waited twelve years. I can’t go back empty-handed. If you don’t have gold, you must send something else.”

“Perhaps he’d like my wife, Apraksiya,” the grand duke suggested jokingly.

“What use would she be to the Khan of the Golden Hordes? He has many beautiful women. Is there someone who plays the lute?”

Suddenly Vladimir remembered that Staver was an excellent lute player.

“Indeed there is,” he replied promptly, “the finest lute player in the land. His name is Staver, one of my favorite princes. You are welcome to take him as a present to the great khan.”

So Vladimir had Staver brought out of the dungeon, and Staver rode back to his castle with Vassilissa, where they lived happily ever after. As for the grand duke, he was pleased as could be that he’d managed to avoid paying tribute to the Ithan of the Golden Hordes for yet another year.

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

"L'ultimo fiore" di Alessandra Pavani

Il sole che s'apre in un graffio di luna

Si spande versandoci in gola

Un vino rosato

Miracolo tal che non teme confronto

Si chiama Tramonto

Ma noi dove siamo se non nel passato?

Eterna l'infanzia non è di nessuna

O forse una sola

Indugia tuttor sul medesimo prato

E chiede alle bimbe fuggite

E' vita la vostra?

Gioite?

Io no, quale vecchia ed inutile giostra

Mi sono fermata

Non voglio lasciar questo sterile prato

E qui avvizzirò come vergine in lutto

Ma ditemi: voi, voi siete felici?

Avete scordato i fantasmi che ci erano amici?

Oppur rammentate che in fondo al passato

Possedevàm tutto

In un graffio di luna e in un sole rosato?

Alessandra Pavani

(la falena Vassilissa)

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

「She’s out when the sun sleeps」🌙 Happy (late lol) Halloween! 🎃 Here’s a Vassilissa piece to celebrate :) Made this in less than a day phewww

#my artwork#my art#illustration#digital art#traditional art#original art#illustrator#chronothief#halloween art#halloween 2023#ghost bride#corpse bride#illustrators on tumblr#digital artwork#digital painting#traditional drawing#traditional artist#original character#oc#artists on tumblr#halloween

34 notes

·

View notes

Text

Names and design ideas for an Ice magical Princess

Because why not.

So, if I go the French Route for names...I think the perfect surname for such a character would be Soubise. Etymologically it means "under the northern wind" and it is known as an aristocratic surname. "Biseau" can also work for the same reason, although it could be etymologically tied to "bis" meaning "greyish brown...Not exactly what we want. Montagne can also work.

For her given name, we could go with Antoinette (priceless), Delphine ("dolphin". "Dauphin" in French can mean "heir to the throne" and the belugas who swim in the great white North are closely related to dolphins, or might even be dolphins, I can't remember it on top of my head), Blanche (snow is white), Guenièvre (from celtic "gwen" meaning "white spirit" and is the French equivalent of Gwenavere). i believe the perfect full name could be :

Blanche Delphine de Soubise

"White female dolphin from under the cold Northern wind"

Russian route for names :

Now...Imidiately, the surname "Morozov/Morozova" springs to mind. "Of the freezing cold". The name "Lebedev/Lebedeva" can also work, as it means "swans" and some swans can inhabit the tundra during the fair season.

For first names, we have the old name Rogneda, a Russian name of Scandinavian origins meaning "wise rule", Vassilissa which can mean "Empress", L'udmila meaning "dear to the people", Antonina "pricessless", Ekatarina "pure".

Russian names also feature a patronym...Svetoslav is the given names that comes to mind "known to the world" or "known to the light".

With that, the ideal name shall be L'udmila Svetoslavna Morozova.

"Beloved of the people of Svetoslav from the freezing cold"

Now, for the English route :

Now...There aren't a lot of well-known English surnames related to the cold or the frost. We have Harley (hares can inhabit very cold climates), Meadow (tundra rich in flowering plants can often be called such), Winter and Frost. We will go with the last one.

For given names, we have "Ada" (from germanic "Adal" meaning "noble"), Alice (also from Adal), Blair (field or meadow), Catherine (from Cataros, meaning "pure"), Guenevere ("white spirit").

All in all, I think Alice Winter works best here.

Now, let's look at German exeamples, and we will then look at pictures.

For surnames...We have Berg (mountain), Frost, Weiss ("white"), Wolf

Adele (from "adal/adel" meaning "noble), Ingrid ("beloved/beautiful"), Edeltraud ("noble strength"), Katrin ("pure")...

I think the perfect name here might be Adele von Weissberg ("noble of the white mountain").

Now, we are going for a drawn character that is meant to be pretty, cute and magical-looking.

I think she should have black, blond or white straight hair and quite rosy cheeks. In terms of cloths, I definitly want some blue. Blue has a symbolic of nobility because blue dye was historically very expensive and it has a "cold" symbolism, particularly lighter shades.

Winter Wonderland is a very good color palette for "frosty" themes.

Pink cheeks and chapped lips are the effects we are going for.

In terms of hairstyle...Braids, but in a way that looks both youthful yet somewhat rafined.

But with ribbons ! RIBBONS !

In terms of clothing style...We need fluffy knitting work.

The cute knitted caplet is non-negociable.

In terms of bottom half...It's very cold, and typically pants under skirt is prefered, or at the very least leg warmers. Long sleeves will be a must.

This is a good silhouette.

So is this for more indoor wear. A middle split could be added to show a pretty winter petticoat.

This is also very nice Inspo :

We could also have a more narrow, medieval silhouette...Although...Hum...The more gathered skirt is lovely for this.

I think the early XVIIth century chemises with the high gathered collars could work if paired with narrower sleeves.

We could also do something inspired by this :

But the sleeves would be a lot more fitted.

0 notes

Text

I accidentally deleted my December 2020 story, The Frog Princess, so here is the repost!

In an old, old land, there lived a Khagan and his Khatun. They had three children, all of them young, and such brave fellows that no pen could describe them. The youngest had the name of Khutulun. One day their father said to his children:

“My dears, take each of you an arrow, draw your strong bow and let your arrow fly; in whatever court it falls, in that court there will be a spouse for you.” The night before, he had received a vision telling him it was a good idea. His wife had also had the same dream, so they both agreed it was a sign.

The arrow of the Jinong fell on the window of a khan’s castle; the arrow of the Khan Khuu flew to the red porch of a rich merchant, and on the porch there stood a sweet girl, the merchant’s daughter. The youngest, the brave Gonji Khutulun, had the ill luck to send her arrow into the midst of a swamp, where it landed by a croaking frog.

Khutulun came to her parents: “How can I marry the frog?” complained the daughter. “Is she my equal? Certainly she is not.”

“Never mind,” replied the Khatun, her mother, “you have to marry the frog, for such is evidently your destiny.”

Thus the siblings were married: the oldest to a young khan; the second to the merchant’s beautiful daughter, and the youngest, Khutulun, to a croaking frog dressed up in a white crown.

After a while the Khagan called his three children and said to them:

“Have each of your consorts bake a loaf of bread by tomorrow morning.”

Khutulun returned home. There was no smile on her face, and her brow was clouded.

“C-R-O-A-K! C-R-O-A-K! Dear wife of mine, Khutulun, why so sad?” gently asked the frog. “Was there anything disagreeable in the palace?”

“Disagreeable indeed,” answered Khutulun; “the Khagan, my father, wants you to bake a loaf of white bread by tomorrow.”

“Do not worry, Gonji. Go to on bed; the morning hour is a much better advisor than the dark evening.”

The Princess, taking her wife’s advice, went to sleep. Then the frog threw off her frogskin and turned into a beautiful, sweet girl, Vassilissa by name. She now stepped out on the porch and called aloud:

“Nurses and waitresses, inspire me at once to prepare a loaf of white bread for tomorrow morning, a loaf exactly like those I used to eat in my father’s palace.”

In the morning, Gonji Khutulun awoke with the crowing roosters.

Yet the loaf was already made, and so fine it was that nobody could even describe it, for only in fairyland one finds such marvelous loaves. It was adorned all about with pretty figures, with towns and fortresses on each side, and within it was white as snow and light as a feather. The Khagan was pleased and the Princess received her special thanks.

“Now there is another task,” said the Khagan, smiling. “Have each of your consorts weave a rug by to-morrow.”

Princess Khutulun came back to her home. There was no smile on her face and her brow was clouded.

In the morning Gonji Khutulun awoke with the crowing roosters.

Yet the loaf was already made, and so fine it was that nobody could even describe it, for only in fairyland one finds such marvelous loaves. It was adorned all about with pretty figures, with towns and fortresses on each side, and within it was white as snow and light as a feather. The Khagan was pleased and the Princess received her special thanks.

“Now there is another task,” said the Khagan, smiling. “Have each of your consorts weave a rug by to-morrow.”

Princess Khutulun came back to her home. There was no smile on her face and her brow was clouded.

“C-R-O-A-K! C-R-O-A-K! Dear Princess, my wife, why so troubled again? Was not your father pleased?”

“How can I be otherwise? The Khagan, my father, has ordered a rug by tomorrow.”

“Do not worry, Princess. Go to bed; go to sleep. The morning hour will bring help.”

Again the frog, once Khutulun fell asleep turned into Vassilissa, the wise woman, and again she called aloud:

“Dear nurses and faithful waitresses, inspire me for new work, to weave a silk rug like the one I used to sit upon in the palace of my father.”

Once said, quickly done. When the roosters began their early “cock-a-doodle-doo,” Princess Khutulun awoke, and lo! there lay the most beautiful silk rug before her, a rug that no one could begin to describe. Threads of silver and gold were interwoven among bright-colored silken ones, and the rug was too beautiful for anything but to admire.

The Khagan was pleased, thanked his daughter, and issued a new order. He now wished to see the three consorts of his children once again, and they were to present them in their best outfits on the next day, during a party.

The Princess Khutulun returned home. Cloudy was her brow, more cloudy than before.

“C-R-O-A-K! C-R-O-A-K! Gonji, my dear wife, why so sad? Have you heard anything unpleasant at the palace?”

“Unpleasant enough, indeed! My father, the Khagan, ordered all of us to present our consorts to him. Now tell me, how could I dare go with you?”

“It is not so bad after all, and might be much worse,” answered the frog, gently croaking after a moment of hurt silence. “You shall go alone and I will follow. When you hear a noise, a great thunder, do not be afraid; simpy say: ‘There is my miserable froggy Beiji coming on her wormy goat.’”

The two elder brothers arrived first with their consorts, beautiful, bright, and cheerful, and dressed in rich garments. Both the happy bridegrooms made fun of the Princess.

“Why alone, sister?” they laughingly said to her. “Why did you not bring your Beiji along with you? Was there no rag to cover her? Where could you have gotten such a beauty? We are ready to wager that in all the swamps in the dominion of our father it would be hard to find another one like her.” And they laughed and laughed, until Lo! what a noise! The grand tent trembled, the guests were all frightened and screamed.

Princess Khutulun alone remained quiet and said: “No danger; it is my miserable froggy beiji coming on her wormy goat.”

To the south facing door came a thundering camel, and Vassilissa, beautiful beyond all description, gently reached her hand to her wife. Khutulun, surprised, led her to the heavy oak tables, which were covered with snow-white linen and loaded with many wonderful dishes such as are known and eaten only in the land of fairies and never anywhere else. The guests were eating and chatting gayly.

Vassilissa drank some vodka, and what was left in the cup she poured into her left sleeve. She ate some of the camel khuushuur dumplings, and the crumbs she threw into her right sleeve. The consorts of the two elder siblings watched her and did exactly the same.

When the long, hearty dinner was over, the guests began dancing and singing. The beautiful Vassilissa came forward, as bright as a star, bowed to her sovereign, bowed to the honorable guests and danced with her wife, the happy Princess Khutulun.

While dancing, Vassilissa waved her left sleeve and a hot spring appeared in the midst of the hall and warmed the air. She waved her right sleeve and a herd of strong camels appeared outside. The Khagan, the guests, the servants, even the bankhar dog sitting in the corner, all were amazed and wondered at the beautiful Vassilissa. Her two siblings-in-law alone envied her.

When their turn came to dance, they also waved their left sleeves as Vassilissa had done, and, oh, wonder! they sprinkled vodka all around. They waved their right sleeves, and instead of camels the crumbs flew in the face of the Khagan. The Khagan grew very angry and bade them leave the party. In the meantime Khutulun watched a moment, then slipped away unseen. She rode home, found the frogskin, and burned it in the fire, slipping back quickly.

Vassilissa, when they came back, searched for the skin, and when she could not find it her beautiful face grew sad and her bright eyes filled with tears.

She said to Khutulun, her wife: “Oh, dear Gonji, what have you done? There was but a short time left for me to wear the ugly frogskin. The moment was near when we could have been happy together forever. Now I must bid you good-bye. Look for me in a far-away country to which no one knows the roads, at the palace of my father, Kostshei the Deathless!” and Vassilissa turned into a white swan and flew away through the window.

Khutulun wept bitterly, for she just realized that she had done a terrible wrong to Vassilissa. Then she prayed, and whirling northward, southward, eastward, and westward, she went on a mysterious journey towards the spot where she stopped, west.

No one, not even she, knows how long her journey was, but one day she met an ancient man. She got off her horse and bowed to the old man, who said:

“Good-day, brave one. What are you searching for, and whither are you going?”

Princess Khutulun answered sincerely, telling all about her fault in her misfortune.

The old man nodded for a moment or two, and then said, “Why did you burn the frogskin? It was wrong to do so. Listen now to me. Vassilissa was born wiser than her own father, and as he envied his daughter’s wisdom he condemned her to be a frog for three long years, and stripped the girl of most of her own powers. But I pity you and want to help you. Here is a magic ball. In whatever direction this ball rolls, follow without fear.”

Princess Khutulun thanked him, gave him some food, water and money in thanks, and followed the ball.

Long, very long, was her road. One day in a wide, flowery meadow she met a bear, a big brown bear. Khutulun took her bow and was ready to shoot the bear.

“Do not kill me, kind Princess,” said the bear. “Who knows when that I may be useful to you?” And Khutulun did not shoot the bear.

Above in the sunny air there flew a duck, a lovely white duck. Again the Princess drew her bow to shoot it. But the duck said to her:

“Do not kill me, good Princess. I certainly shall be useful to you someday.”

And this time she obeyed the command of the duck and passed by. Continuing her way she saw a blinking hare, pausing in a sunny glade. The Princess prepared an arrow to shoot it, but the grey, blinking hare said:

“Do not kill me, brave Princess. I shall prove myself grateful to you in time.”

The Princess did not shoot the hare, but passed by. She walked farther and farther after the rolling ball, and came to the deep blue sea. On the sand there lay a fish. It was a big fish, almost dying on the dry sand.

“O Princess Khutulun!” prayed the fish, “have mercy upon me and push me back into the cool sea.”

The Princess did so, and walked along the shore. The ball, rolling all the time, brought Khutulun to a hut, a queer, tiny hut standing on tiny hen’s feet.

“Izboushka! Izboushka!"—for so in Russia do they name small huts—"Izboushka, I want you to turn your front to me,” cried Khutulun, and lo! the tiny hut turned its front at once. Khutulun stepped over and saw a witch, one of the odd witches she could imagine.

“Ho! Princess Khutulun! What brings you here?” was her greeting from the witch.

“O, you old mischief!” shouted Khutulun with amused and false anger. “Is it the way in Russia to ask questions before the tired guest gets something to eat, something to drink, and some hot water to wash the dust off?”

Baba Yaga chuckled at her audacity, and then the witch gave the Princess plenty to eat and drink, as well as hot water to wash the dust off. Princess Khutulun felt refreshed. Soon she became talkative, and related the bizarre story of her marriage. She told the witch how she had lost her dear wife, and that her only desire was to find her.

“I know all about it,” answered the witch. “She is now at the palace of Kostshei the Deathless, and you must understand that Kostshei is terrible. He watches her day and night and no one can ever conquer him. His death depends on a magic needle. That needle is within a hare; that hare is within a large trunk; that trunk is hidden in the branches of an old oak tree; and that oak tree is watched by Kostshei as closely as Vassilissa, which means closer than any treasure he has.”

Then the witch told Gonji Khutulun how and where to find the oak tree. Khutulun hastily went to the place. But when she perceived the oak tree she was much discouraged, not knowing what to do or how to begin the work. Lo and behold! that old acquaintance of hers, the bear, came running along, approached the tree, uprooted it, and the trunk fell and broke. A hare jumped out of the trunk and began to run fast; but another hare, Khutulun’s friend, came running after, caught it and tore it to pieces. Out of the hare there flew a duck, a gray one which flew very high and was almost invisible, but the beautiful white duck followed the bird and struck its gray enemy, which lost an egg. That egg fell into the deep sea.

But when the egg disappeared in the blue waters she could not help weeping. All of a sudden a big fish came swimming up, the same fish she had saved, and brought the egg in her mouth. How happy Khutulun was when she took it! She cracked it in half and found the needle inside, the magic needle upon which everything depended.

At the same moment Kostshei lost his strength and power forever. Princess Khutulun entered his vast dominions, killed him with the magic needle, and in one of the palace rooms found her own dear wife, her beautiful Vassilissa. She apologized, they fell in love on the way back to the Khaganate, and lived happily ever after.

The Frog Princess Explanation

So, I first came across this story in an old storybook containing tales from across the world. This one is originally set in Russia, thus the name Vassilissa for the Frog Princess. But I liked the idea of Vassilissa managing to hop far away from her dad (Kostshei is basically the Deadpool-Ice King that causes problems in many Russian stories) and her rescuer Khutulan kind of being thrust into this foreign magical drama. So most of the story is set on the wild steppes of Mongolia.

This is a gay love story because while looking up references for clothes, I remembered that the Mongolian people sometimes had woman warriors. This drew me into a rabbit hole checking out the LGBTQ+ community in both Russia and modern day Mongolia. Russia has a lot of issues, and Mongolia has limited rights. So, I decided to make this a wlw* story, in honor of the communities in both countries.

*Woman-loving woman. It means a lady who also, or only, wants to kiss ladies in the place of guys.

Let’s go over the terms I stuck in here. The Khagan was basically the emperor of the Khans - the position is often called ‘Great Khan’ in older English texts. A Khaganate is an empire ruled by a Khagan. Khans are lesser kings or land-owning nobles. The Khatun is a Khagan’s wife consort. Consort is basically an older term for ‘First Lady’, a title only received by marrying a royal or noble, and they get no governing powers. Jinong is crown prince, Khan Khuu is another word for prince (the eras for using this terminology might be a little mushed together), and Gonji means Princess.

Beiji means princess consort; while I’m pretty sure the word is supposed to be joined with a prince’s wife, I figured it also worked for a Princess’s wife.

Khutulun’s name came from a highly competent cousin of Kublai Khan, the grandson of Genghis Khan. She was a wrestler who could basically beat up anyone and was actually seriously considered to be a successor to her father.

Okay, now for the explanation on drawing choices!

The first picture was my attempt at word art, the frog’s head being the English name of the story. The jaw is the name in Russian (because despite my changes, the story is originally Russian), and the tongue is how to say it using English sounds and letters. It isn’t my best title, I know, but I had fun and frankly it reminds me of the old bootleg Russian cartoons I used to watch as a little kid. My favorite from back then was called ‘Scamper’, although it was called ‘The Adventures of Lolo the Penguin’ in the original apparently.

The first picture is a drawing of a long-legged wood frog, native to Russia and some parts of Mongolia. I also looked up how arrows were made in that area of the world, but you can’t really see it so my research was kind of moot, lol.

The second was based on a picture I found on some weird Russian blog site. But the picture was nice and clear and close up, so I was pleased. It took me a decent amount of time to copy the carpet design.

Picture number three is my favorite. I had wayyyyy too much fun trying to copy the different fancy designs of the two different princess’s dresses (did you know that Padmé Amidala’s headresses and some robes from Star Wars were based on Mongolian dress outfits?!) and went crazy over that Bactrian* Camel (two-humped) and its harness and saddle.

That is the cutest animal I’ve drawn in months, and as I am writing this I’ve just finished drawing a fawn. I decided to do a camel instead of horses because while both are important to the culture, I am really tired of drawing horses. Camels are easier.

*Bactrian camels are named after a long-gone West Asian country, Bactria. I believe Bactria is actually the Latin name for it, as many countries that end with -ia are actually the Latin names, or the names from a language that are at least partly based on Latin. For example Australia, named by the English (whose language is partly based on Latin) means Land of the South Wind (Austral = funny way of spelling Auster, the name of the lord of the south wind, ia = land). So I doubt that Bactria was the original name. Either way, two humped camels are always called Bactrian. Dromedaries, which just means fast walkers for some reason, are the one humped camels. They’re more numerous and have more of a domestic population, but they’re a bit less comfortable with the cold than Bactrians.

The fourth picture has a horse off-screen. I had fun drawing Khutulun in more casual wear (look at her big boots! I love them for some reason), and drawing someone as nuts as Baba Yaga and her house was kind of fun.

Anyways, I hope you enjoyed it!

1 note

·

View note

Text

Sparkling

Xinomavro, Assyrtiko ‘22 / Karanika / “Cuvée Spéciale” / 11% / Amyndeon, Greece €45

Müller-Thurgau, Neuburger, Muscat ‘22 / Milan Nestarec, “Danger 380V” Pet-Nat / 10.5% / Moravia, Czechia €56

Pinot Noir, Meunier, Chardonnay / Pol Roger, Champagne “Brut Réserve” / 12.5% / Épernay, France €125

White / Cyprus

Xynisteri ‘22 / Vouni Panayia, “Alina” Unfiltered / 12.5% / Pano Panagia, Paphos €32

Viognier ‘20 / Argyrides / 13% / Vasa Koilaniou, Limassol €33

Spourtiko ‘23 / Makarounas / 10.5% / Letymbou, Paphos €35

Promara ‘23 / Makarounas, “Amphora” / 12% / Letymbou, Paphos €46

Promara, Xynisteri, et al. ‘22 / Tsiakkas, “Exelixis” / 12% / Pelendri, Limassol €46

Promara ‘21 / Mystes, “Oreites” / 14% / Archimandrita, Paphos €52

Vassilissa ‘21 / Vouni Panayia, “Symbiosis” / 13.5% / Pano Panagia, Paphos €61

White / Greece

Kydonitsa ‘23 / Tsimbidi / 13% / Monemvasia, Peloponnesos €31

Roditis ‘23 / Tetramythos, Retsina “Amphore Nature” / 12% / Ano Diakopto, Achaea €33

Sideritis ‘22 / Acheon, “In Amphorea” / 12% / Aigio, Aigialeia €35

Moschoudi, Assyrtiko ‘23 / Papargyriou / 13% / Corinthia, Peloponnesos €36

Moschofilero ‘22 / Moropoulos, Mantineia / 13% / Arcadia, Peloponnesos €37

Vidiano, Thrapsathiri ‘23 / Iliana Malihin, “Lefkos” / 13.5% / Melabes, Crete €38

Robola ‘22 / Sarris / 12.5% / Panochori, Cephalonia €38

Dafni ‘23 / Lyrarakis, “Psarades” / 12.5% / Alagni, Crete €39

Chardonnay ‘20 / Papaioannou, “Fumé” / 14% / Corinthia, Peloponnesos €40

Assyrtiko ‘22 / Lyrarakis, “Voila” / 13.5% / Alagni, Crete €40

Malagousia ‘23 / Tetramythos, “Nature” / 11.5% / Ano Diakopto, Achaea €42

Roditis ‘21 / Bairaktaris / 12.7% / Nemea, Peloponnesos €46

Muscat Blanc à Petit Grains ‘23 / Kostaki, “Early Harvest” Off-Dry / 9% / Neo Karlovasi, Samos €48

Malagousia, Assyrtiko ‘23 / Georgas, “Black Label” / 12% / Spata, Attica €50

Zakynthino ‘22 / Sclavos / 13% / Lixouri, Cephalonia €53

Assyrtiko, Athiri ‘22 / Sigalas / 13.5 % / Baxedes Oia, Santorini €58

Begleri ‘22 / Afianes, “Litani” / 11.5% / Profitis Elias, Ikaria €68

Roditis ‘21 / Ligas, “Barrique” / 12% / Pella, Central Macedonia €79

Assyrtiko ‘22 / Mikra Thira / 13% / Therassia, Santorini €96

White / Rest Of The World

Furmint, Irsai Olivér ‘23 / Kristinus, “Olivér” / 10% / Balaton, Hungary €31

Alvarinho, Loureiro ‘23 / Soalheiro, “ALLO” / 11.5% / Melgaço, Portugal €35

Garganega ‘23 / Le Battistelle, “Montesei” Soave Classico / 12% / Veneto, Italy €41

Riesling ‘22 / Knebel / 11.5% / Mosel, Germany €42

Grüner Veltliner ‘21 / Michael Gindl, “Buteo” / 12.5% / Weinviertel, Austria €46

Caiño Blanco ‘21 / Pedralonga, “Carolina” / 13% / Rías Baixas, Spain €62

Sauvignon Blanc ‘23 / Du Nozay, Sancerre / 13% / Sancerrois, Loire Valley €64

Roero Arneis ‘21 / Vietti / 14% / Agliano Terme, Piemonte €65

Grüner Veltliner, Pinot Blanc ‘22 / Gut Oggau, “Timotheus” / 13.5% / Burgenland, Austria €119

Chardonnay ‘22 / Jean-Paul & Benoit Droin, Chablis Premier Cru “Montmains” / 13% / Burgundy €125

Orange

Sideritis ‘22 / Tetramythos, “Nature” / 12% / Ano Diakopto, Achaea €38

Xynisteri ‘17 / Aphrodite Constanti, “Microcosmos” / 12.5% / Paphos, Cyprus €39

Roditis ‘23 / Sant’Or / 11.5% / Achaea, Greece €42

Gewürztraminer, Pinot Gris, Welschriesling ‘23 / Meinklang, “Mulatschak” / 11.5% / Burgenland, Austria €41

Santameriana ‘22 / Sant’Or / 13% / Santomeri, Achaea €49

Morokanella ‘23 / Vouni Panayia, “Nature’s Vengeance” / 13% / Paphos, Cyprus €61

Muscat of Alexandria ‘22 / Garalis, “Terra Ambera” / 12% / Lemnos, Greece €73

Vostilidi ‘21 / Sclavos, “Metageitnion” / 13% / Cephalonia, Greece €79

Pink & Light Red

Mavrodaphne ‘22 / Sclavos, “Alchemiste” / 13% / Cephalonia, Greece €35

Xinomavro ‘22 / Thymiopoulos / 12.5% / Naousa, Greece €35

Pamidi ‘23 / Vourvoukeli / 13% / Abdera, Xanthi €38

Mavro ‘23 / Zambartas, Single Vineyard / 13% / Limassol, Cyprus €40

Liatiko ‘23 / Iliana Malihin / 13.5% / Rethymno, Crete €41

Yiannoudi ‘22 / Mystes, “Oreites” / 14% / Paphos, Cyprus €55

Field Blend ‘22 / Gut Oggau, “Cecilia” / 12% / Burgenland, Austria €119

Red / Cyprus

Opthalmo ‘21 / Nelion / 14% / Pretori, Limassol €35

Maratheftiko, Mavro ‘21 / Tethys / 13.5% / Trimiklini, Limassol €38

Maratheftiko ‘19 / Vouni Panayia, “Barba Yiannis” / 13.5% / Pano Panagia, Paphos €40

Yiannoudi ‘21 / Vlassides, “Óroman” / 14% / Koilani, Limassol €40

Yiannoudi ‘22 / Makarounas / 13.5% / Letymbou, Paphos €45

Maratheftiko, Yiannoudi ‘22 / Mystes, “Oreites” / 13% / Archimandrita, Paphos €52

Maratheftiko ‘22 / Vouni Panayia, “Wine Freak” / 11% / Pano Panagia, Paphos €61

Yiannoudi ‘20 / Vouni Panayia, “Red Balloon” / 13.5% / Pano Panagia, Paphos €61

Lefkada ‘21 / Anama, “Oak Matured” / 13.5% / Lythrodontas, Nicosia €95

Red / Greece

Agiorgitiko, Mavroudi ‘14 / Tsimbidi, “Monemvasios” / 13% / Monemvasia, Peloponnesos €33

Aglianico ‘18 / Hatzimichalis / 13.5% / Nemea, Peloponnesos €38

Mavro Kalavrytino ‘22 / Tetramythos, “Nature” / 12.5% / Ano Diakopto, Aegialia €39

Xinomavro ‘20 / Markovitis, Naoussa / 14.5% / Polla Nera, Naousa €40

Agiorgitiko ‘19 / Papaioannou, Nemea / 14% / Corinthia, Peloponnesos €41

Xinomavro ‘19 / Karanika, “Old Vines” / 12.5% / Amyndeon, Florina €43

Xinomavro ‘19 / Chatzivaritis, Goumenissa / 13% / Goumenissa, Kilkis €46

Negoska ‘23 / Chloe Chatzivaryti, “Carbonic” / 11.5% / Goumenissa, Kilkis €47

Mavrodaphne ‘20 / Sarris, “Megali Petra” / 13% / Panochori, Cephalonia €48

Limnio ‘19 / Anatolikos / 14.5% / Avdera, Xanthi €49

Syrah ‘21 / Skouras, “Fleva” / 14.5% / Argolida, Peloponnesos €59

Kotsifali ‘21 / Aori / 12.5% / Chania, Crete €61

Mavrotragano ‘18 / X-Bourgo / 14.3% / Tripotamos, Tinos €68

Mavroudi ‘20 / Anatolikos / 14% / Avdera, Xanthi €70

Xinomavro, Syrah ‘19 / Kir-Yianni, “Diaporos” / 14% / Yiannakochori, Naousa €97

Liatiko ‘21 / Karavitakis, “Indigenous Yeast” / 12.5% / Pontikiana, Crete €119

Red / Rest Of The World

Grenache, Syrah ‘21 / Paul Jaboulet Aîné, “Parallèle 45” Côtes du Rhône / 14% / Rhône, France €36

Primitivo, Negroamaro, Nero di Troia ‘21 / Pajaru, “Vientu” / 15% / Salento, Puglia €38

Moravia Agria, Garnacha ‘22 / Envínate, “Albahra” / 13% / Almansa, Castilla-La Mancha €41

Sangiovese ‘22 / Selvapiana, Chianti Rufina ‘29 / 13.5% / Florence, Tuscany €42

Malbec ‘22 / Krontiras, “Natural” / 14% / Mendoza, Argentina €52

Tempranillo, Garnacha, et al. ‘16 / R.L. de Heredia, “Viña Cubillo” Crianza / 13.5% / Haro, Rioja Alta €55

Frappato, Nero d’Avola ‘23 / Arianna Occhipinti, “SP68” / 12.5% / Vittoria, Sicily €58

Blaufränkisch, Rösler ‘21 / Gut Oggau, “Josephine” / 12.5% / Burgenland, Austria €119

Blaufränkisch ‘21 / Gut Oggau, “Joschuari” / 13% / Burgenland, Austria €136

Corvina, Corvinone, Rondinella, et al. ‘15 / Quintarelli, “Ca’ del Merlo” / 15% / Verona, Veneto €232

Corvina, Rondinella ‘15 / Bertani, Amarone della Valpolicella Classico / 15% / Verona, Veneto €273

Dessert

Malaga, Xynisteri, Black Muscat ‘15 / Vouni Panayia, “Anthologia” / 14% / Pano Panagia, Paphos €63

Xynisteri ‘20 / Tsiakkas, Commandaria / 14% / Pelendri, Limassol, Cyprus €75

0 notes