#vaash vroga

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

"you have mental illness" actually i don't, those are just unfortunate side effects from using the powers from my amulet to often. such power deranges a man.

144K notes

·

View notes

Note

Where are Baltrice, Tessebik, Masrath, Ramaz, Tyreus, Boragor, Grinth, Kento, Khazi, Sifa Grent, Sylvene, Vronos, Azor, Crucius, Garth, Greensleeves, Meshuvel, Grandmother Sengir, Ravidel, Sandruu, Daria, Commodore Guff, Bo Levar, Taysir of Rabiah, Kristina of the Woods, Dyfed, Feroz, Leshrac, Maive, Manatarqua, Vaash Vroga, Comet, and B.O.B.? I'm especially concerned about my favorite, Parcher.

I only put down Canonical ones with Planeswalker cards.

Half of these people I'm sure nobody cares about and would be taken out R1.

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

So it seems like the Orphan of Urborg, Vaash Vroga, will be added the list of planeswalkers from video games that may never get a physical card alongside such characters as Kenan Sahrmal and Ramaz.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Rise and Fall

(Below is the unabridged version of a fanfic I did for the very cool MtG Lore *Adrift* fanzine. You can also read the unabridged version on my AO3 if ya like ;) )

Vaash Vroga walked the beach on a nameless world, following in the wake of its creator.

It was not the first artificial plane she'd ever tread. Her journeys through the multiverse had taken her through the meditation realm of Nicol Bolas more than once (an oddly high number of times, truth be told, for a place closed off to so many). She had even spent several painful minutes staggering through the ruins of old Phyrexia, failing to locate some ancient artifact or another at the behest of her now-discarded mantle, before the vile fumes of the place had overcome her and forced her to flee. She still bore scars along her legs from the whip-like blades that passed for grass on the sixth sphere.

This current plane had a more convincing veneer of naturality to it, but the hallmarks of a planeswalker's vanity were still there, if one looked close enough: The sand was just a bit too clean and golden, and the air not quite as fishy as it ought to be, this close to the sea.

An unsettling creation to tread, pleasant though it was on the senses.

The creator, for his part, moved at an infuriatingly leisurely pace, slowing often to stare out over the water at storm clouds which had been gathering for the past half-hour. His eyes were bright, and uniformly amber, set deep into chiseled features lined with age.

“How much further?”

“Hm?” The creator turned his head, slackening his pace further by half a step. He was dressed in a simple sleeveless tunic of gold-trimmed white, with a cloak of the same pristine fabric that left his legs bare from mid-thigh down. Both garments glowed with an almost imperceptible light.

“How far is our destination?” Vaash gestured ahead, jabbing all five fingers at the stretch of beach and grassy hills before them.

“Ah.” The creator nodded and resumed his previous pace. “No destination. I thought a walk would be a nice change for you." He veered a degree to the right, and started up a low rise overlooking the shore. Tall, dark-green grasses grew in patches that quickly thickened as the beach rolled inland into a meadowed field. "'Tis nicer by far to walk in the open air, under the sun, than remain cooped up in some Izzet lab or tolarian dormitory."

Vaash squinted up at the sky. It was decidedly overcast by now. There were rays of light still peeking through the seams in the clouds, but those seams were closing rapidly.

"Did you make that?” She asked. “It feels just like natural sunlight."

"It's a rescue," the creator replied, his grin full of teeth. "A treefolk 'walker pulled that sun into the eternities about five hundred years ago to deny it as a power source to a rival. I plucked it from there."

"The Battlemage Ravidel is as resourceful as he is formidable," Vaash remarked.

The creator paused, mid-stride, and Vaash halted two paces away. When he turned to look at her, his smile was tight.

““Ravidel,�� if you please. We will have a frank, straightforward conversation, unmuddied by titles or deference. We are peers of the multiverse, you and I.”

“No deference here.” Vaash held out her hands and gave a mock bow. “If the mighty Ravidel wishes to call me 'peer', I won’t deny him.”

Ravidel snorted. “Very good. You can lose ‘the mighty,’ but good.”

“Surprisingly humble for a centuries-old tyrant.”

“Hm.” Ravidel nodded, not turning back. “I find myself discovering and re-learning humility every century or so.”

The two planeswalkers hiked a ways longer in silence. They passed two fishermen, and a group of children combing for shells in the surf, but weather had driven the other inhabitants of this pocket plane further inland. The fields Vaash could see were mostly empty, save for fireflies and a far-off shepherd herding a flock of woolly, blue-furred creatures. The grassy portion of the beach started to slope upward, and soon they were walking along the ledge of a low ridge, with the meadow to their right, and a straight drop of several yards down to the sands on their left.

"Well." Ravidel paused at a small boulder set at a high rise, and perched upon it. "What do you think? Not bad for my first plane."

Vaash regarded the sea and sky.

"Not bad for an old man's retirement home, I suppose."

Ravidel chuckled. "Hard to impress a planeswalker. Even one of you young bloods."

Vaash shrugged. “I’ve seen plenty impressive bits of this vast multiverse; Jodah could have told you as much. My adventures on all the planes that Ral and that little mind-mage friend of theirs chased me through could fill a book.”

“Mind mage?” Ravidel shot her quizzical look. “Jodah told me it was a necromancer that helped them subdue you and strip you of the mantle.”

“So he thinks,” Vaash grimaced. “Ral insists their ally is a geomancer. And the first time we fought, I was certain their traveler friend was a beast mage. The only explanation I have for the discrepancy is that they’re actually an illusionist, hiding whatever other powers they have with mind-tricks. Of the three, they are the one I trust the least.”

"Hm." Ravidel shrugged. “Sounds like an unusual fellow."

“What planeswalker isn’t?” Vaash shook her head. "Ral and Jodah think I'm a bit mad. They don't even realize that they can't agree what their nameless friend is."

Ravidel didn't offer a response to that. His attention had turned to the figures on the beach below: a clutch of older children, human and goblin. A few were tending to a small fire, while the others stood in the shallows, ankle-deep in the slightly-too-sapphire-colored water, fishing with sharpened sticks. The ones by the fire caught sight of Ravidel and called out excited greetings. Ravidel acknowledged them with a wave and a nod.

"You're wondering why you're here," he said.

"You didn't give Jodah much time to explain...or make introductions."

"I thought he'd have filled you in on who I am ahead of this meeting."

Vaash grimaced. "The archmage can be a bit absent-minded in that regard."

"Old, old habits," Ravidel sighed. "My name, at least, speaks for itself?"

"I have had a rudimentary schooling in history, but even that poor education found time for you.” Vaash lifted her hands and made a line in the air. “Apprentice to the long-vanished planeswalker Faralyn, Destroyer of Arathoxia, ‘The Plague Upon Corondor,’ scourge of your fellow planeswalkers, and bitter enemy to the line of Carthalion."

"All apt monikers." Ravidel patted his knee thoughtfully. "History has judged me fairly, if harshly."

"The old Cabal head claimed some of those names for his own, a while back." Vaash lowered a hand to the ground, dropping spores of green and black to the grass. "Your monikers, and others, too. Though he's dead now. Pasty-skinned demon bastard." She spat in the grass, and a saproling shimmered into being where the spores hovered: thigh-high, and made of thick tendrils supporting a cushion of tan toadstool caps.

She sat down upon the saproling, and sighed as the pressure eased off her tired soles. Ravidel regarded her, elbows on his knees.

"You slew him?"

Vaash shook her head. "Other ‘walkers took care of him. The same ones who thrashed old Bolas on Ravnica."

"You'd rather have done the deed yourself." It wasn't a question.

"Sure." Vaash shrugged. It was an easier gesture to do nowadays, without that heavy garment draped around her shoulders. "But it's a positive outcome no matter who killed Belzenlok. The Cabal is weakened and Urborg is safer for it."

"And that is important to you."

Again, not a question. So Vaash did not answer.

They sat in silence a long while, faces cooled by the pre-storm winds whistling in from the sea, and backs warmed by the inland breeze, smelling now of bittersweet milkweed and ozone. Ravidel's breaths were short and loud enough to be heard over both winds. Awkwardly so. The few oldwalkers Vaash had encountered in her time were all like that in some regard. Still uneasy in the trappings of newly mortal bodies, even decades after the mending had lessened the nature of the spark.

Maybe they just breathe loud because they miss being the center of attention.

"What is it you want out of life, ultimately?"

Vaash looked up at Ravidel. He'd lifted up a hand, where five rings gleamed, one on each finger. Each was inset with a gem.

Vaash could have sworn they were not there a minute ago.

“What?”

"What does Vaash want for Vaash?” Ravidel continued. “Surely you do not begin and end at Urborg." As he spoke, points of colored light peeled off from the rings and swirled in his open palm.

“‘Vaash’ has not had much time alone for Vaash. But I am content in the freedom I enjoy as a mage and ‘walker to do as I please.”

Ravidel raised an eyebrow. “Or as others please that you do?”

Vaash regarded Ravidel. He held her gaze, lights spinning faster and faster in his palm.

"This talk is going to be about Leshrac, isn't it?"

"..Yes." The lights in Ravidel’s palm did not falter, but as soon as Vaash said ‘Leshrac,’ their rapid orbits expanded to circle around the back of Ravidel's hand.

"Why?" Vaash rested a hand on her hip, close to the hilt of her sword. Ravidel had requested she not bring her blades with her. This was her compromise. "Why bring me here to lecture me on my tormentor?"

“I am uniquely qualified to do so: I know what it is to be twisted to the ends of another planeswalker. I know what it is to twist others to my ends. And, of course, I knew the planeswalker who has most recently twisted you to his ends."

The colored lights slowed and hovered, one over each of Ravidel's fingers. The pearly light elongated into the figure of an old man with golden robes and a shining crown. The sapphire unspooled into a burly, many-tendriled beast with scales the color of dull steel. The black twisted into what appeared to be an old crone, with flame around their brow, and a large tunic the color of night.

"Leshrac,” Ravidel said as this last figure spun into being. “A peer of my first master, Faralyn. Along with Tevesh Szat, they conspired to slay one of their fellow 'walkers during a Summit on the Null Moon, and then to use the life force to escape their joint imprisonment on Dominaria. Instead, their plotting led to my own death and sparking, and the death of my dearest friend.”

“He’s supposed to be dead,” Vaash whispered, eyeing the dark-cloaked image. “Supposed to have died decades ago in the mending, shoved face-first into a rift by the god-emperor-dragon of Madara.”

“We died with surprising regularity, we walkers of old,’” Ravidel sighed. “an astounding regularity, for beings so close to gods.”

“Well he didn’t die...or at least, old Bolas didn’t do his job thoroughly enough.” Vaash crossed her arms. “Left enough of that wretch alive in the mantle to use and torment me.” She shrugged her shoulders again, to reassure herself they were still bare.

“Yes,” Ravidel said, not soft, but softer than he had spoken previously. “But that can all be behind you, if you would re-think your schemes for the future.”

Vaash scowled "I have not spoken of schemes for the future. Or for Leshrac. To you or Jodah or Ral."

"But you have spoken about him to Jodah, and for all his peculiarities, a planebound mage as old as Jodah doesn't survive as long as he has without a sense for reading intentions between the lines."

"Go on then." Vaash rose from the saproling seat and placed her hands on her hips. "What are my intentions?"

Ravidel’s eyes tracked hers as she rose. He pursed his lips, watching her and breathing sharply through his nostrils.

"Your intentions are ones I know well," he said at last. "Vengeance. Plain and simple."

"Yes, plain and simple." Vaash walked past Ravidel, moving slightly past him along the slope. Her saproling scurried to follow. "Intentions so plain and simple, in fact, that we don’t need to discuss them further."

"Jodah wishes you to reconsider. I wish you to reconsider."

Vaash turned and frowned. Ravidel had risen from the stone, and the colored lights were circling his entire arm now, tracing a rainbow of lines through the air.

"By threat?" She snarled.

Ravidel shook his head. "By reason. By example and demonstration."

“The great Ravidel has become a teacher?’

“Ravidel is more than a magical tyrant,” he replied, with a dry smile. “Ravidel has had centuries to hone subtler arts than spell-craft. You’d be amazed what you have time for when you step away and let all the world think you’re dead.”

“I have too many responsibilities for something like that. Urborg’s enemies are many and industrious; I cannot tear my attention away from their activities for long.”

“Urborg is important to you.”

"Urborg is my responsibility. A land in need of Freedom. All the world dismisses us as a sulfurous swamp, yet all the world cannot help but interfere with our people. The black primeval, Nevinyrral, the Cabal...tyrants all, and I would see an Urborg free of tyrants. I would see a multiverse free of tyrants, if possible, but Urborg is where I have started."

"Noble and high-minded." Ravidel nodded. "Were you brought up among freedom fighters, or do you come by these ideals yourself?"

"Hah!" Vaash spat upon the grass. "My ideals are my own. 'Freedom' couldn't have been further from the aims of those who raised me."

"No love lost between you and your parents, then?" Ravidel turned a wry look out toward the beach. He was watching the children in the surf tramp back to the fire, with nets and sticks full of fish and shellfish. The fishing group had taken notice of the planeswalkers as well, and a few were waving to Ravidel. He returned a broad wave, and motioned for them to return to their play. "I sympathize."

"I lost my parents to the breathstealers when I was six." Vaash hissed. "Urborg’s infamous death cult. They are the ones who brought me up, raising me and children like me to feed into the meat grinder of their mercenary service.” Vaash paused. her chest was filling and falling rapidly. She closed her eyes. And slowed her lungs, letting the rise and fall become deeper, slower, and then regular again.

"And yet the breathstealers taught you many lessons," Ravidel observed, as she opened her eyes again. "Your prowess with death magic demonstrates as much."

Vaash shrugged. “A good lesson can come from anywhere. It does not make the teacher good. Always there was an ulterior motive with the breathstealers. They taught power for no purpose but to farm us out as child soldiers to any unscrupulous mage willing to pay the right price. Breathing exercises to make us silent killers. Lessons in eating mana and casting spells to make us deadly in magicks. Artifacts of power gifted to us not out of pride or for our protection, but always in service of the Nightstalker Spirit in its many manifestations. Can you guess how many times I was taught growing up that the greatest thing I could aspire to was to die and merge with the great nightstalker? To die and spread death in the names of Avarre and Necros and Bethanelle? To serve-" Vaash cut off, and folded her arms, looking out toward the water. "No, Ravidel. My inclinations to freedom are separate from and antithetical to the breathstealers. They are another ill upon Urborg and upon Dominaria, and I will see their cult erased from the world."

This time she did not need to correct her breathing, though Ravidel still waited a long moment before responding.

"That's where the mantle came from." This time there was the hint of a question in his voice. But just a hint.

"Jodah told you of the mantle?"

"A power-storing and consuming garment that bears the mark of Leshrac? Of course he did. I am, as I said, one of the few living authorities on the Walker of the Night."

"I thought you didn't care for titles."

"This particular title might be salient, given the mantle's origins." Ravidel looked her up and down. "‘Spirit of the Night’… ‘The Nightstalker’… ‘Walker of the Night’ … I am curious why they would bestow such a tool upon you. Are you a descendant of Leshrac? Was he a breathstealer himself?"

"I do not know or care if Leshrac was a breathstealer. A handful of my elders among the breathstealers thought he might be some legend from their past...perhaps even the Nightstalker itself, taken the form of a man. As for me...I was an orphan," Vaash turned away from Ravidel. Her voice became a harsh whisper on the breeze. "My parents were nothing and nobody, but they were mine, and the breathstealers killed them to make me into a tool. This is their practice all across Urborg. I was nothing special to them, and the mantle was just a means. A pretty basting on another sacrifice intended to raise another iteration of their night-stalking god." She let her arms fall to her side. "Well, I guess they succeeded in the end, didn't they?"

Ravidel nodded. “I must ask...do you have any inkling of how Leshrac survived? How he came to be in the mantle? Anything you didn’t tell Jodah?”

“I have answered every question Jodah has asked of me fully and honestly. Do you have any inklings? You claim to be the authority.”

Ravidel shook his head. "I have theories, but that is all. Perhaps the mantle was made from the same artifact Nicol Bolas stuffed Leshrac's spark into. Perhaps it was an unrelated contingency Leshrac cooked up after seeing so many of his fellow walkers of old perish so suddenly and unexpectedly over the centuries.”

"In any case," he sighed, "you are better off quit of the mantle. And of Leshrac.”

"We are all better off quit of Leshrac," Vaash replied through her teeth. "So it will be quite the favor I do the multiverse when I track him down and erase whatever sliver of him still lingers among the living."

Ravidel pursed his lips, eyes on the clouds in the distance. The colors circling his arm shuddered, leapt up into the air, and spiraled in a wide ring overhead, twisting around one another into a broad, tangled, rainbow-hued circle.

"Your life magic is self-taught, I gather, given your upbringing, so likely you never had a mentor to teach you of the cycles of life."

"I taught myself quite adequately," Vaash said, eyes narrowing. “And even self-taught lessons can be educational.”

"Humor me." Ravidel's eyes flashed, and the space within the ring overhead filled with a blaze of imagery. Dragons, forests, fire-red skies, armored giants, and dozens of scenes lasting but a fraction of a second that Vaash could not identify.

The images began to slow and blur. Color melted into color, and for a moment the disk was pure, unbroken white. A second later, two figures resolved from the blankness. A tall woman with a warrior’s build and cascading blonde hair. Beside her, a hunched but burly old man with a walking stick and a thin cap upon his head.

“Tev Loneglade was a planeswalker,” Ravidel began. His voice had a slight echo to it. More vanity. “Old and powerful. Not the friendliest of ‘walkers, but content to keep to himself.”

"Tev Loneglade had a sister, Tymolin. One precious to him, for whom he expended his magical prowess to protect and keep alive. She was taken from him-"

A flurry of figures swirled around the two Lonelades – saprolings and elves, merfolk and lobster-people. Goblins, orcs, and dwarves, a man speaking to a cluster of hunched homunculi, and figures in white. These last surrounded the tall woman, and she fell out of the disk, limp.

“-and slain. So Tev fell to rage and despair, and became Tevesh. Tevesh Szat.”

The hunched and burly man turned reptilian and blue-scaled. Tentacles blossomed around the ring. The reptile-man reached down.

“Szat swore a vengeance against his sister's killers, and then against Dominaria, and eventually, once free of the shard, against everything and everyone, so fully did he lose himself to his hatred of the few that stole away his sister. He sowed discord and ruin across all Dominaria and every plane he could in the Shard of Twelve Worlds.”

Steaming tears streamed from the burly thing’s red-hot eyes as it tore through figures – black and white at first, then green, blue, and red.

"Many years later, Tevesh Szat slew my dearest friend at the Summit of the Null Moon, to escape the Shard. Tore away the most precious one in my life in the same way the Farrelites took his sister from him. He did not do this to spite me. Nor did he act with any intent to inflict a wound on my soul the same as he had suffered, but he did so nonetheless, and in doing so spurred me to become a beast not entirely unlike he was."

The scene twisted again and fractured – the golden-robed man in the crown spoke to a blue dragon, and was vaporized by mist. A long-antlered man screamed from a pyramid as the dead rushed around him through knee-deep snows.

“I became a scourge to many, mortal and walker alike, all in the name of revenge-”

Ravidel himself stood on a rise before a collection of figures, brandishing a chained bowl. A red-haired man was struck dead by Ravidel’s magics. A freckled woman trudged through a dark forest. A man in a turban assaulted a minotaur with magics, and was in turn cut down by a golden-haired figure wearing dark glasses. Szat screamed in a dome of glass as electricity cooked his flesh.

“-and all for naught. Did my campaign of vengeance bring my friend back from the dead? It did not. I accomplished nothing against the ‘walkers I saw as having manipulated me, other than to hurt the ones who once wished to help me. Faralyn got himself killed like a buffoon the moment he made it out of the Shard. Tevesh Szat evaded me for centuries, only to die at the hands of some greasy-fingered tinkerer. Taysir and I sealed Leshrac away for a time, but by then my hatred...my bitterness had a mind all its own. It had become so core to my being that I could not put it aside, and I embraced means that made me indistinguishable from the walkers I had sworn vengeance upon at my sparking.”

Ravidel closed his eyes. “So it was that the cycles of vengeance claimed me, and used me to perpetuate further misery.”

Vaash snorted. "And let me guess - it all starts with one bad decision. A decision to chase vengeance."

Ravidel nodded. “It starts with a compromise. A bending of your principals, justified with the belief in the good of your ends. Then another compromise, allowed because two compromises cannot possibly be that worse than one. Then, eventually, comes a complete break from your principals, once you are well and invested in your ends. Before you know it, a snowdrift of compromises have buried the ruins of whoever you once were.”

“So what’s the solution?” Vaash spread her hands. “Never risk compromise? Never retaliate against the wicked?”

“Not at all. A better way is to be honest, and to not fool yourself when a compromise comes. When you break with your ideals, acknowledge the break, and reassess yourself. Otherwise you’ll have no idea what you’ve become. You won’t understand that you are fundamentally a different person, and in trying to reconcile the self with the lost ideal, you will lose yourself further.”

“Easy enough. I promise to assess whether I am at peace with killing Leshrac.” Vaash stared at Ravidel for two and a fraction of a second. “Done. I have decided to proceed.”

Ravidel shook his head. “Whether or not you make that honest assessment of yourself, you’ll still have changed. You’ll still have become the you who makes the compromises vengeance demands, and even if you make peace with that person, the rest of the world must now contend with them. The person you are now, or the person who compromises. You can’t be two people at once.”

“What if I want it both ways?” Vaash drew her hand in a line through the space between Ravidel and herself. Five spears of mossy light bloomed around her. A moment later, a second Vaash stood on the rise beside her, skin glowing with green veins. “Who says I must choose between the Vaash I am and the Vaash who takes vengeance? Why must it be an inherently corrupting process?” She cut another line, and a third Vaash appeared, this one trailing wisps of black smoke.

The green Vaash nodded. “Who says it is even vengeance? That is your word, and Jodah’s. Can I not simply be a responsible mage who cleans up after her own messes?”

“Everything we do changes us, Vaash Vroga.” Ravidel clenched his fist, and the ring above pulsed with fresh power. Overhead, the red-haired man knelt before a black horse with a flaming mane. The turban-clad man spied on the freckled woman from before, as Ravidel whispered into his ear. A young man with long black hair raised a sword above a fallen archer, screaming in rage. A bronze-skinned woman poured fiery magic into a burly elf, who spasmed in pain. “One does not pursue a creature like Leshrac, or even the shadow of Leshrac, without risk to oneself and others. Inherently self-altering risk. Did you not compromise yourself significantly in your pursuits for artifacts to feed to Leshrac’s mantle?”

The black Vaash crossed her arms. “It seemed a better path than nourishing the mantle with the breath of orphans.”

“And yet look at what you did do. Destabilizing Zendikar. Attacking your fellow ‘walkers.”

“Walkers who did not care to understand-”

“And Shiv? Were your actions there the work of the ambitious, high-minded mage who wishes to free the planes of tyranny?”

The black Vaash’s eyes fell to the ground. “That...was a compromise. A bad one.”

“A man like Deniz-”

“I know!” Vaash herself interrupted. “I know and I regret it! I told myself he was Benalish. That his people also fight against the Cabal. I saw them as allies, and I thought his intervention on Shiv would be beneficial for their...”

She tapered off as Ravidel raised an eyebrow.

“...it was a compromise.” She turned to face the beach and the sea. A trail of smoke was blowing off the children’s fire, swept inland and up the slope below them, where the warm breeze from inland carried it back over the sands and the waves. “One of many. There was power to be gained in having an ally who controls the mana rig. Enough perhaps to power the mantle without hunting artifacts on other planes.”

“It must have been quite the burden, keeping the mantle fed.” Ravidel lowered his ringed hand. “What was that like? The hunger of the mantle? Of Leshrac?”

“At first? Not much at all. I fed his mantle because sustenance for it meant power for me. A pool of energy. Easier spellcasting. A sort of intuition that helped me develop my own casting. But after a while...” Vaash grimaced. “...it became worse than hunger. Worse than any thirst, or the need to breathe, even. I would have cut the throat out of my own mother if it meant staving off the pain the mantle’s cravings caused me.”

She looked over at Ravidel. “Still, I told myself it was better than feeding on others. Better than sucking the breath out of children to keep the mantle...to keep Leshrac sated.”

“When did he take control?”

“He didn’t...” Vaash paused. “That is, there was no one moment. It’s not like I became a puppet or anything like that, it’s just that feeding the mantle became its own end. That’s how bad the ‘hunger’ was. One day on Zendikar I woke up, and instead of feeling an intuitive guidance from the mantle, it was whispering directions into my ear.” She clenched both her fists. “I could have not listened, maybe. But I’d lived so long feeding the mantle at that point that, well...” She trailed off. “Let’s just say it’s good Ral and his mystery friend stopped me when they did.”

“It’s the cycle.” Ravidel said. He said it like that was all there was to say. “The Breathstealers wronged you. The Cabal wrongs your homeland. And in your efforts to right those wrongs, you have spread the cursed cycle of wrongs wider still. The only solution can be this: Remove yourself from the cycle, and feed it no longer.”

Vaash and both her copies were silent. Green looked down at her feet, scowling. Black gazed off into the sky, arms folded and face blank. Vaash herself regarded Ravidel. He had his clenched fist raised, and one foot resting on a rock. His breath was slow and steady, his belly swelling and contracting with each breath. He might have looked grand, posed as he was, if she weren’t completely certain it was all just a display. The emerald ring on his finger was glowing a conspicuous degree brighter than the others.

“Do you like the person you are, Ravidel?”

Ravidel blinked. “I...what?”

“Would you say that you like yourself? As you are now?”

“I am proud of what I am,” Ravidel said. “Of what I have made of myself, considering my past. He gestured toward the children, who were cooking their catch over the fire, surprisingly uninterested in the magics happening above their heads. “Where once I ruined lives, broke homes, now I provide preservation of both. A whole plane, safe and peaceful, for the orphans I left in my wake, and for their descendants.

“And for myself, I have found that, removed from the cycle of vengeance, I have had time to find out who ‘Ravidel’ is. I am a powerful mage, yes but also a cultivator. A builder. A provider for many. I have found peace, humility, and an appreciation for my place as a walker of the planes.”

“You found humility?” Green Vaash raised an eyebrow, eyes on the battlemage’s impossibly gleaming garments.

He shrugged, spreading his arms. "I found out Ravidel is someone who enjoys a bit of theatricality, and grandeur. I like that about myself as well."

“And would you be who you are now, if you hadn’t done all those things? If you had not fallen into the cycle of vengeance? If you had not learned all you know now from the mistakes you made?”

Ravidel’s arms faltered, falling a few inches. He pursed his lips. “No, I suppose I wouldn’t be. Still, I would excise those years of my life from existence, if I could. All those lives lost, people killed...were they worth it for one mage to become a better man?”

Vaash stared at him, and shrugged.

“Yes,” Ravidel said, smiling sadly. “Fair enough.” He looked at Vaash and each of her simalcra in turn. “I suppose we live with all versions of ourselves at all times, don’t we?”

Vaash shrugged again.

Ravidel took his foot from the stone, and sighed. “Taysir told me once, back when he deigned to be my mentor, that the people of old Yotia believed we have many souls. Many selves throughout the many stages our lives. They believed the good would be judged separately from the bad. Redemption and ascension for part of the self, punishment for the rest.”

Green Vaash laughed. A rough, harsh sound. “Sounds like a fiction to comfort the repentant wicked.”

“Perhaps,” Ravidel sighed, “but Taysir took comfort in it, I think, when he abandoned his interplanar questing and settled down to live apart and in peace. His own nature was such that a belief system built around a multiplicity of souls must have felt natural. I find myself taking comfort in it in my twilight years...and who's to say? Gods, immortals, afterlives; I’ve seen a dozen different belief systems play out before my eyes on a dozen different planes. It’s hard to fully be a skeptic.”

“Being a planeswalker is a great cure for skepticism,” black Vaash muttered.

Ravidel laughed. “Agreed.”

Vaash’s response faltered on her lips as a fork of lightning speared the sea, far out at the horizon line. The sky had grown quite a bit darker since they’d left the sand for the grasses, but the bolt illuminated the landscape like a flicker of sunlight.

Another spear of lightning flashed across the sky seconds later. Then another and another.

Another.

Another, far too rapid in succession to be natural. Vaash looked over at Ravidel. He nodded, and put up a hand, but his eyes were fixed on the crackling horizon. She bit her lip, but turned to face the sea, and inhaled. The green and black Vaashes flowed back into her.

The children were likewise transfixed, but weren’t retreating. A few of them had actually walked closer to the shore, skewers of roasted seafood in hand, though they stayed well clear of the waterline.

All the while the lightning riddled the distance with lines of power.

Just when Vaash thought the noise and the light could not grow any more overwhelming, the horizon fell dark and silent.

But just for a moment.

A dragon flashed into being over the sea. Then again. And again. It took three strobes for Vaash to realize the dragon was not real, but a sculpture of electricity, soaring toward the shore, roaring with the blast of thunder. By a trick of light, its scales appeared to be solid chrome, reflecting the sea and the clouds.

It rushed the shore, blinking in and out of being with millisecond rapidity, wings wide.

Closer it came. Closer still, until Vaash thought it would tear through the sky overhead. Just as it reached three hundred yards from the waterline, the dragon reared up, wings and limbs spread in a triumphant display. There was another, booming roar-

-and then silence.

The sky was empty once again, save for the undulating blanket of stormclouds.

The children lost no time in cheering and jumping about the sand. It was odd, Vaash thought as she watched them. The bolts never actually touched the water.

“A tribute to a friend,” Ravidel whispered, hoarse. “A little vanity built into the structure of the plane back when I had the power for such things.”

“Was he fond of dragons, this friend of yours?”

Ravidel tilted his head as if considering the question, then let out a soft laugh.

“You know, one could make a convincing argument that he was not. His name was ‘Rhuell.’ As in, ‘to rule.’ An ironic name for one who spent so much of his life in servitude.” Ravidel closed his hand. The ring of mana above them collapsed into his fist and was extinguished. Raindrops, minute pinpricks of coolness in the still-warm air, dotted Vaash’s face and arms.

The wind slowed from bellow to whistle, a warm whip across the skin.

“I’d welcome you to stay here a while,” Ravidel said. “To think over vengeance before you take it. The planes will carry along fine in your absence. All our schemes and plots spilling out from world to world? It isn’t natural, and it isn’t beneficial.”

“Natural?” Vaash laughed, swinging her hand out over the ocean and the children. “None of this is natural. A world with engineered weather? A world peopled by transplanted citizens? Only a planeswalker could do such a thing, and you cannot tell me it is not an especially slick patch on the slippery slope of abusing godhood.”

Ravidel grimaced. Not quite a flinch, but the closest thing to it Vaash had seen from him. “It would be impossible for me to do more than this now, with the nature of the multiverse so changed by the Mending-”

“You’ve made a dollhouse that will fall apart as soon as you are gone from the multiverse. An irresponsible decision even when you were a true immortal, and downright ruinous now that the Mending has come and done its ravaging work upon the nature of the spark.”

“I’m trying!” Ravidel snapped back. His brow furrowed. Just a fraction, but it was the most agitation he’d shown so far. “Do you think I haven’t considered the fragility of this place? It weighs on my every moment. Not a day goes by that I do not plumb my prowess and knowledge for a way to preserve it past my passing. I do not mean to be Ravidel the careless, any more than I wish to again be Ravidel the cruel. Ravidel the callous and hateful.”

“That’s my point. A walker does not have to be cruel or hateful or vengeful to be a danger to the multiverse.”

“I am more at peace with the multiverse than-”

“Peace!” Vaash laughed. “Don’t kid yourself, Ravidel. We ‘walkers can never be at peace with the multiverse. We are an aberration. Intruders by nature. Every trip we take through the eternities is an affront to the nature of existence. A man might tread cautiously through the swamp, but still he will trouble the fish with his movement and crush the snails underfoot.”

She cut off, breathing measured, but deep. Ravidel grimaced, and said nothing.

“But,” Vaash said, after a moment, “it is not a terrible thing. What you have done here. I think it admirable in its aims, overall. I would commend you for it on another day, when my temper does not run so hot. But what I will not do is nod along with you and pretend that your sort of meddling is less a danger to the planes than mine.”

“I keep myself to this plane now. I have left the rest of it to be as it will.”

“As it will?” Vaash’s nostrils flared. “And how exactly do you think it will be, left all alone? Sunshine and freedom for all, now that big, bad Ravidel has graciously decided to rampage no longer?”

Ravidel, clenched his jaw. “I acknowledge I am not the only danger out in the multiverse, but by leaving my own vengeance behind-”

“It is not better to leave the cycle behind than to remain.” Vaash snapped. Her saproling, which had gone to huddle in the taller grasses when the lightning began, scurried over for her to sit upon. “Power not used for good out in the multiverse is power that might as well have been snuffed out. Was it not a great tragedy when your actions removed more benevolent planeswalkers from the world? Or when Lord Windgrace gave his life to preserve the nature of reality itself? Tell me, how did it help the multiverse at large when Taysir went into seclusion and hermitage? Doesn’t the inability of such powerful beings to do good throughout the multiverse tear at your heart? And would the outcome not be the same if they had just disappeared to a pocket plane, never to be seen again except to lecture at-”

“Lord Windgrace was just as much an isolationist as I when he lived-”

“-And now he can never be anything else!” Vaash snapped. “Your question before, if your growth was worth the cost of your sins – it’s the wrong way of looking at things altogether. Nature does not care about moral equity. What is done has been done. Maybe you’ve become a better person, but it’s of no benefit to the multiverse if you stay here, closed off from it.”

“Be careful how much you presume the multiverse needs people like us.” Ravidel extended a hand toward the storm. “Despite the many ills that ravage it…” He gestured toward the fields, where fireflies drifted through the grass “...the denizens of the planes will endure.”

“Yes,” Vaash replied, “But I would rather they endure without tyrants than with. With fewer storms and calamities.”

“An answer for everything.” Ravidel let his hand fall.

“Yes. This is a conversation, isn’t it?”

Ravidel opened his mouth as if to respond, but seemed to think better of it. He exhaled instead, still loud and abrupt, and sat back down upon the stone.

“It is that. I forget myself.” He inclined his head, and gestured at Vaash. “Please.”

“All belief and magic comes from nature, and all nature is about the cycle. The cycle of wrongs and responses is as natural to human intercourse as the predator-prey system. There’s no escaping the cycles, at least not for the planebound. Even the gods must live within them the best they can.” Vaash clenched her fist. “You’ve made me realize something. As walkers, don’t we have a privileged position? A rare perspective on the cycles? Of life and death, vengeance and kindness? How can you tell me it is good to remove ourselves from the cycles when our privilege makes us among the few who can ease the suffering of those within?”

Ravidel stared at her, though by the way he worked his jaw, he did appear to be considering her words.

At last he smiled.

“The green mage wishes for harmony, and black mage will do anything to achieve their ends...together...peace at any cost.”

Vaash frowned. “What are you talking about?”

Ravidel chuckled “Just thinking about some blowhard old friends. Antiquated theories on the colors of magic. I’m not sure how much stock I put in them anymore. We used to be very old-fashioned about spellcasting.”

“Old indeed,” Vaash shrugged. “The magic of the forest and fen are closer than most mages imagine. On most planes it’s just the ratio of mulch and moisture.”

Ravidel nodded, slow. “The same tree that drinks sunlight above casts darkness below its leaves.”

Vaash grimaced. “Yes.” She flexed her fingers, and a five-pointed fork of moss and mud-colored light jabbed up into the space in front of her face. The spikes of light twisted into a spiral, and collapsed again into a single point over her palm. “Many cycles at work. And these… ‘colors,’ as you put it, are not always what they seem.”

He nodded, first at Vaash, and then toward the fields, glowing the fireflies. “Do you know, they call them ‘lightning bugs’ in some places? Fire...lighting...the very soul of the red mage, yet I’ve yet to find the pyromancer or lightning mage who have ever called such creatures to their aid. I suppose lightning bugs make for poor combatants.” He raised an eyebrow at Vaash.

“We summon for reasons other than combat,” Vaash returned.

“We do that,” Ravidel acknowledged with a smile. “I have considered your rebuttal, and I think us perhaps both wrong.”

Vaash raised an eyebrow. “Oh? So an old dog can still ponder new tricks?”

“To stay in the cycle and let it buffet us about is beneath a walker. Even if we see the cycles for what they are.” Ravidel opened his hand. His rings glowed, faintly, but there was no display of light this time. “But to abandon it is, as you suggest, a waste of our potential. We can be proactive in our good as much as in our wickedness. More so, if we are willing to be selfless.”

“I say we must still be careful about assuming a direct outcome between good intentions and good outcomes,” Vaash offered. “My vengeance against Leshrac has much to offer the multiverse. My vengeance might do more good and save more lives than the high intentions of most other powerful ‘walkers.”

“So what do we do then, young blood?”

“You seem to have all the answers, old man.”

Ravidel stood, and clapped his hands together. “We cannot leave the cycle, and it make no difference to simply remain.” He began to pace the grasses.

Vaash pivoted in her seat to follow his pacing. “So we guide the cycle.”

“We influence it the best we can.” Ravidel pounded a fist into his hand. “Use our knowledge having been tossed about by the cycle to determine how to best spin to the ends of peace. Perhaps find an equilibrium where those within the cycles do not just survive, but thrive.”

Vaash nodded. “Remove the worst elements to keep the cycle from spinning out of control. Elements like Leshrac.”

“Yes, like Leshrac.”

“Agreed on all points.” Vaash tapped the hilt of her sword. “Not a conclusion I would think it’d take centuries to arrive at, but agreed.”

“I don’t talk much with other travelers these days. The mind stagnates when left alone.” Ravidel stopped in place. The winds were picking up again. The fireflies were going to ground once more. “It will be dangerous, chasing Leshrac. There will be risk and a great danger of collateral damage if not handled carefully. It would be completely understandable if you preferred to leave this task to me.”

“Fuck off, old man. I am the one allowing you to accompany me in this endeavor.”

“...very well. I’d hoped I could be an instructor to you, but perhaps you’ve got a thing or two to teach me as well.” Ravidel waved his hands, and his garments transformed. His tunic turned to leather armour, and his cloak to a cape of crimson.

Vash grinned. “There we go. I won’t call you ‘Battlemage’ if you truly loath the title, but I’m happy to see you looking the part again.”

“You have quite formidable allies already, Vaash Vroga.” Ravidel clasped his hands behind his back and walked to the edge of the rise. The children had returned to the fire to eat their catch. A few had finished and were playing some sort of dancing game on the sand “I ask again, are you quite certain you want one like me in your life. Not just to offer my advice, but to strive alongside?”

“Ral has been an agreeable companion, and Jodah a useful contact. Now, I need an ally with fangs, and a willingness to draw blood with those fangs.”

“This has been a serendipitous meeting then.”

“Serendipitous, sure. If we will be working together, you should know I make my own luck.”

Ravidel blinked. He hadn’t done much of that, even with the storm winds battering them.

“How do you mean?”

“You said it yourself: you are one of a very few people alive who know Leshrac. Who can speak to his person and power from personal experience. Who would have a reason to go after him, as I would like to. Jodah in turn is one of the few people alive with the longevity to have known a person like you. It stands that, if I indicated an interest in pursuing Leshrac, he might draw you in as a resource.”

Ravidel stared at Vaash. His mouth was agape by a sliver of an inch; somewhere between amused and aghast. The two warred a moment, before he smiled.

“I appreciate the honesty, though I grow warier of you with every surprise you throw my way.”

“Good. If I am to learn from you, I would rather you be on your guard.” Vaash returned Ravidel’s smile. “If you are still willing.”

“Don’t underestimate me.” Ravidel smirked at Vaash. “I’ve years of practice at manipulating mentors to my own ends. I’m on the lookout for your tricks.”

“Don’t you worry about me; I’m not an aspiring megalomaniac.”

“Oh, I don’t know about that. I hope you will not take too much offense when I say you have the perfect cadence and bearing to become one.” He raised his brow. “I have some expertise in this area, you understand, having studied a few up close over the centuries.”

Vaash raised an eyebrow. “Thank Windgrace you didn’t pick up any of their bad habits.”

Ravidel laughed at that. Really laughed, a cackle that cut through the growing bluster of the storm. A madman’s laugh, no mistaking it, but Vaash found it oddly comforting.

“I try to limit myself to their good habits these days. For example: I would be following Taysir’s path to the letter if I took on a protege.”

“Taysir is dead, if I recall my history correctly. He and his protege.”

Ravidel shook his head. “He is my model, not my destiny. I have my own path to walk.”

“Nothing is foreconcluded,” Vaash ventured.

“Very green of you,” Ravidel said with a smirk. He stepped back from the ledge. "I would ask one thing of you, at the outset of our partnership here."

"What would that be?"

"If we do this...once its over...while it's underway...I want you to think long and hard about who Vaash Vroga is, and what she wants for herself, should she ever allow herself to rest." He held out a hand. "Agreeable?"

"Tolerable," Vaash clapped hands with him, and they shook. "I look forward to getting to know both of us."

"Indeed."

“And when we find what remains of Leshrac, will you be kind to him, as you have been to me? Is rehabilitation on the menu for the walker of the night?”

Ravidel laughed. “There is more difference between his wickedness and yours than there is difference from a drop of water and the core of the sun.”

Vaash paused. “...and what is the difference between your past evils and his?”

"Hm..." Ravidel tilted his head one way, then another. “My rehabilitation was a rare bolt of lightning shot through the eternities.”

“You’ll have to tell me about it sometime.”

“I just might. Regardless, I would not count on such a turnaround happening lightly.”

Vaash snorted. “Sounds solipsistic.”

Ravidel grinned. “It is.” He spread his arms at the sea and hills around them. “But much of my life has been similarly self-centered.” He laughed again, and Vaash found herself chuckling as well. The air was still warm, but now thicker droplets of cool water were beginning to pepper them, wetting her face and bare forearms.

“Arcades’ Scales, that’s a nice feeling,” Ravidel remarked as the laughter faded to a chuckle. He had his face upturned to the sky.

“You’re breathing wrong.”

“Hm?” Ravidel turned to look at Vaash sidelong.

Vaash drew in a long breath, letting her chest swell slowly. She gestured at her breast. “Expand as you inhale-”

She let it out, whistling into the wind. “Draw in as you let your breath go. Let your chest rise and your lungs fill. Your lungs, not your belly.”

Ravidel copied her for several repetitions. “Hm. The benefit being?”

“Oxygen gets into the blood; you’ll live longer, old man.” She smirked at him. “And waste less time on spells of vigor.” She nodded her chin at his emerald ring, which still glinted brighter than the others.

Ravidel snorted. “Impudent. You’ll make a fine protege.” He breathed in and out again, with a thoughtful grimace. “And is this a technique of…?”

“Just good practice in many cultures, on many planes.” Vaash turned back to the sea, and nodded. "But yes, learned in Urborg.” She let the weight put on ‘Urborg’ say what her words did not.

“A lesson learned can be put to good use no matter the source,” Ravidel said. “I heard that once, but in my old age, I can’t quite remember where from.”

Vaash snorted. The rain water had soaked her hair by now, and warm trickles of water were pouring down her neck and face.

It did feel tremendous. She allowed herself a smile.

A laugh.

Ravidel howled in turn. Their laughter melded with the rumble of thunder. The whistle of the storm wind. The laughter of the children on the beach.

They both sounded quite manic.

But it takes a bit of mania to change the world.

20 notes

·

View notes

Note

VAASH VROGA FOR SMASH BROS 2k24

It occurred to me that since she originated in a video game, Nissa is technically eligible to appear in Smash Bros. Probably never going to happen, but is it something you'd enjoy in the billion-to-one chance that it did?

[The only *official* stated requirement that a character has to pass in order to be in Smash Bros. is that they were created for/made their first appearance in a video game.]

It’s also true for Ral and Kiora.

147 notes

·

View notes

Text

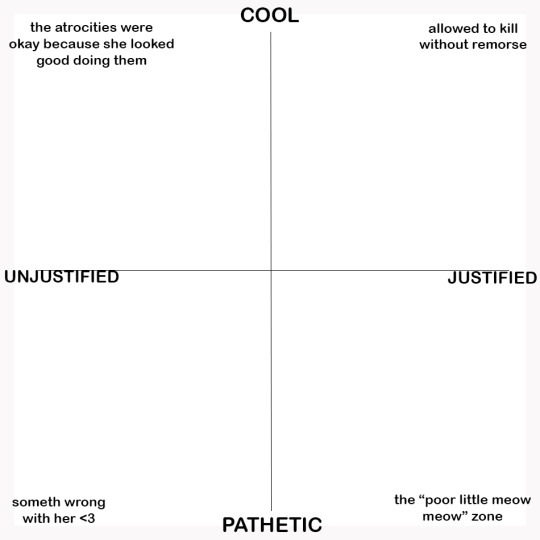

So I was thinking about Evil Women, as one does, and I think I’ve cracked the code. There’s a taxonomy here, and they all fit into it somewhere.

I present to you: The Axis of Female Murderers:

#mtg#liliana vess#vona#latulla#rakka mar#nailah#vaash vroga#selenia#savra#xira arien#oona#geyedrone dihada#sheoldred#elesh norn#ravi#ashling#karona#ashnod#radiant#braids#glissa sunseeker#tsabo tavoc#emrakul#shauku#sifa grent#phage#lady orca#nahiri

43K notes

·

View notes