#unnamed terror fandom beauty project

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

GALLIPOT PROJECT SHOP UPDATE 5/22

I've been doing sneaky shop updates for a week or two now but it's finally time to post about them! I've got a bunch of new historically-inspired stuff live on my BigCartel shop -- you can use the code SOLSTICE for 20% off your whole order from now through 6/21.

1840s-Inspired Shaving Soap

A nice puck of tallow shaving soap for use with a shaving brush or your regular-degular hands. Enriched with a shitload of other oils and lightly scented with Atlas cedar, frankincense, and patchouli. I've got an upcoming post about shaving and 1840s shaving soaps so stay tuned!

Carnivale Lip Tints

Three buildable shade options for the girlies (gn) formulated with mango butter, beeswax, and sweet almond oil. All three of these use historically-attested ~*~*lip rouge~*~*~ pigments, incorporating carmine; if there's any interest in vegan versions of these using period vegetable waxes/pigments, let me know!

Shades, top to bottom: Graham Gore Red; Royal Marine Red; Platypus Pond Pink

Historically-Inspired Perfume Oils

Sold in 5ml amber glass apothecary vials -- these are 1840s-inspired but otherwise completely modern because they won't let me distill any floral waters in my one-bedroom apartment. All citrus-based oils used in these blends are FC-free.

Francis Crozier - Ambergris, musk, rosemary, spike lavender, lemon, orange, and petitgrain

James Fitzjames - Oakmoss, patchouli, Bulgarian rose, jasmine, neroli, and bergamot.

Hydesville Ghost - Atlas cedar, Bulgarian rose, rosemary, benzoin, myrrh.

Huile de Florida - Neroli, bergamot, lemon, rosemary, clove, rose geranium, bitter orange, and cardamom.

I had a ton of fun making these and I look forward to sharing them! These have been in the works since earlier this year and I'm hyped to get them out to people.

Some general updates: I've retired the Gallipot Project Etsy store because, whew, no kidding, Etsy's policies are bad bad. My first run of white Windsor soaps didn't turn out exactly how I'd like it to, but the second batch should be live and available before long. I'm also investigating other mid-19th-century soap formulations and their accompanying scents. Follow my projects and historical cosmetics and hygiene meta at my #unnamed terror fandom beauty project tag!

64 notes

·

View notes

Text

Experiments In Early Victorian Skincare: Unguentum Resinosum

(Note: since Tumblr seems to be making text posts deliberately inaccessible to anyone not logged into a Tumblr account, I'm still crossposting these posts to the Gallipot Project stand-alone blog over on Wordpress.)

This element of the project I stumbled upon while reading about Royal Navy medicine chests — even in all the excitement and anxiety of the recovery of Erebus and Terror, with plenty of discussion of the potential to glean information from what the crew left behind, it slipped my mind that among the relics recovered from the final Franklin expedition there might be actual medicaments (or at least their residues) left behind. My brain is a thick sludge right now due to a spicy range of events, but I wanted to give a little more detail about this chapter in my experiments.

Unguents Of Historical Significance

The original item that served as the springboard for this was a component of the Victory Point medicine chest recovered by Lt. William Hobson with the McClintock expedition of 1857. The medicine chest and its contents are now in the Royal Museums Greenwich collection. For more on the chest, I recommend this series of posts by S.L. over at 70 North Beset, which includes a wonderful guide to the chest’s cryptically-labeled contents and their uses.

The item we're discussing is by all appearances mislabeled, or rather stored in a repurposed container with a label indicating its previous contents. (If you've ever kept Band-Aids in an Altoids tin or safety pins in a medicine bottle, you're carrying on a proud tradition.) There's no image of the container by itself on the RMG's website, but I believe it's the round black container with the octagonal paper label on the bottom left here, just above the sticking-plaster box.

Image © National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London

(so what the fuck is that supposed to be?)

Franklin expedition research frequent-flier Richard J. Cyriax’s “A Historic Medicine Chest”, published in the Canadian Medical Association Journal in 1947, describes the box and its contents as follows:

a circular metal box said on a label to contain ground ginger but actually containing what seems to be an ointment, now dried up almost into a ball. McClintock’s inventory mentions a box containing shrunk ointment, and no other article in the chest agrees with his description. The ointment is of a light yellow colour and possesses no definite odour; it may be “unguentum resinae”, which was very often used in surgical practice.

Okay, great, but wtf is unguentum resinae? I took this recipe from the 1830 Edinburgh New Dispensatory, compiled by Andrew Duncan, professor of materia medica at the University of Edinburgh.

Presto, salve plus resin.

So yeah, there are a lot of different salves in play in this era, some of them damn close in formulation. As much as I like making funky little unguents, making a full slate of these recipes might be overkill. This same text contains a whole mess of recipes for other liniments, ointments, cerates, and plasters, including a half-dozen variations on the theme of “some proportion of some kind of fat + some proportion of wax, white or yellow”. Duncan’s description continues on the next page:

THESE [presumably meaning the preceding recipes], which are varieties of the basilicon ointment, are commonly employed in dressings for digesting, cleansing, and incarnating wounds and ulcers.

(Basilicon ointments supposedly achieved this effect by, uh, causing pus production. Thanks, I hate it.)

Side note: If a salve is oil-based, how can it dry up, like the sample in the ginger container? This is how my dumb ass learned that oils can indeed evaporate over time. Presumably the inclement weather conditions at Victory Point didn’t help, but it’d be an interesting experiment for a long-haul-minded Franklin enthusiast to keep a tin of this stuff around over the course of years to see how it responds.

What is this salve for? Why carry it all the way to Victory Point? Why abandon it there? Honestly, I find these questions pretty confounding, starting with the first — the use of unguentum resinae appears to have been so wide and unremarkable that I’m not getting a lot of detailed information about how they were meant to be applied, and the information I am getting is very much framed like you (the presumed-medically-trained reader) should know this shit already. The recovered medicine chest also contains a stockpile of materials used for bandaging and dressing wounds: bandages, lint, sticking plasters, and cotton wool. So wound care definitely seems like a focus of this set, and I’d wager this salve’s use fits right into that mix. One interesting thing that both Cyriax and the writer over at 70 North Beset remark upon is that the Victory Point medicine chest is unlikely to have been a government article issued to the ships’ officially recognized medical personnel; even to my eye, it lacks any obvious broad-arrow branding. Was this some random officer’s personal supply? Was it carried to supplement official medicine chests or perhaps salvaged from a late officer’s belongings? I’m looking forward to more news from the wrecks to see if they shed any more light on the material culture of medicine aboard Erebus and Terror.

I encountered a source remarking that “unguentum resinae” was simply a drawing salve by another name — this assertion gave me pause since I’m used to “drawing salve” itself being another name for black salve, a whole category of corrosive salve used in bogus cancer cures that you should absolutely, absolutely not use on any part of your body. But drawing salves are a whole category of their own in folk medicine (including folk veterinary medicine) and were very much in use during the 19th century, without necessarily entailing the corrosive effect of sanguinarine and its eschariotic sisters.

In turn, what kind of salve did I make? I made two batches, one plant-based salve with more similarities to ceratum resinae, and one pork lard salve more closely replicating the Edinburgh formulation for unguentum resinae/resinosum. The recipe for either salve is pretty damn straightforward, so I didn’t feel driven to document all the double-boilering and pouring here; the only tricky element was sourcing my pine resin. Lots of people go out and wildcraft their own tree resins, which is fully possible but not something I have access to; I bought my resin from a Canadian retailer selling food-grade pine resin for wax wrap-making.

For my first non-lard rendition of this salve (sort of an “inspired by” version) I took cues regarding the proportions of liquid oil:butter:beeswax:resin from modern salving. Folk medicine practitioners still use similar pine resin salves as a topical treatment for minor wounds, an anti-inflammatory joint rub, or a reliever of chest congestion — it’s also a pretty basic emollient for dry skin and these are the uses I focus on when I make salves for myself/my loved ones, rather than dressing more serious wounds. If you tweak your ratios, you can also use the same basic elements to make reusable beeswax wraps for food storage; this is actually the stated purpose behind the pine rein I sourced, since I’d feel some qualms about using resin earmarked for specifically holistic purposes in my silly living history project.

For my second batch, I used the same resin and beeswax but paired them with a pork-derived lard. I put this round off at first due to hesitation around how to best source a non-hydrogenated rendered lard. Since concerns about shelf-stability were the motivation behind my first oil-based batch, I didn’t want to go about rendering my own pork fat au naturel or buy the $25/lb impossibly-bougie Epic lard aimed at keto/paleo people who have Whole Foods $$, but I also didn’t want to go with your Armour lard in a shelf-stable brick — I ended up tracking down a local butcher shop that renders their own.

Honestly this version came together even more smoothly than the previous version — I crushed my resin into smaller pieces rather than waiting for big old rocks to melt down, and the lard gave a more slick, less “tugging” consistency to the resulting balm. It doesn’t smell meaty or pork-like at all; there’s a faint odor of wood resin, but that’s it, and if I didn’t care for that it would be pretty easy to doctor up with essential oils. I will say that at room temperature the consistency seems a little firm for use in a plaster, but I might need to glob it on more generously and allow body heat to soften things up. A little bit of a raw deal for those dealing with polar weather extremes, but maybe unavoidable.

How would you make a natural preparation using approximately 1840s ingredients that remained soft and spreadable at colder temperatures? Honestly, I don’t know if this is something people planned for, since abandoning ship wasn’t anyone’s first choice, but it would have been relatively easy. Increasing the proportion of fats/oils to beeswax is one way to adapt any fat/wax recipe for colder weather use, but another option I can think of could be using fats/oils that solidify at lower temperature points. Some useful data there you probably know off the cuff — if you put olive oil in a cold fridge, it’ll solidify into a chunk; if you keep your coconut oil out at room temperature, you can tell the weather’s warming up when it goes fully liquid in the jar — but for better suggestions than that I had to resort to Modern Science.

I’m based in the US and use Fahrenheit most often but this is a pretty clear case where Celsius is superior. The Franklin expedition crews were dealing with outside temps of -40° and lower, and while interior temperatures (as long as the ships’ heating systems held out) weren’t nearly as nippy, they might well have been in the “your Costco coconut oil remains firm and opaque” range. If they wanted emulsified oil-based salves with maximum spreadability at ambient temperature, something runnier from the low end of the freeze/melt temp scale might have been handy.

[For a table listing different values here, head over to the blog!]

Not all of these are suitable for salvemaking (linseed oil, my old enemy) but castor oil is feasible, for instance. I might make up some compare-and-contrast salves to explore this but uhhhh not any time soon, because I already have so many fucking salves. The plant oil-based salves are up for sale on my Bigcartel site now -- would you be interested in buying a beef tallow-based salve? Speak up in the comments and let me know!

Overall I’m very pleased with the result of my salve-making, and the smaller or nonexistent amount of butter ingredients like cocoa butter should hopefully prevent the slight granularity that some of my other creations have developed in cooling. I like the tallow-based salve a little better and its emollient consistency is lovely.

How skin-safe is this product? The biggest issue is that pine resin is a well-known trigger for dermatological issues like contact dermatitis. If you know you’re allergic to it, please don’t make this recipe or buy salves containing it! You have way better options for wound care than a stranded Victorian sailor.

How vegan is this product? Well, not at all vegan, in either variation, due to the beeswax. I have gotten my hands on some vegan waxes, so sound off if you’d be interested in a purely plant-based version of this recipe too, or another exploration of Early Victorian receipts adapted to modern methods.

Meanwhile… I get to figure out what I’m going to do with the rest of this lard.

#unnamed terror fandom beauty project#franklin expedition#lard-based medicaments#long post#PLEASE let the read-more cut work on this i'm serious#gallipot project

37 notes

·

View notes

Text

Experiments In Early Victorian Skincare: Shaving Soap, Part One

- And how does it feel, not being fetched for drops nor drawers? - Miserable, sir. That is my job you are shaving away. (AMC's The Terror, s01e07, "Horrible From Supper")

(Crossposted to Wordpress as usual)

We have some great period resources describing contemporary techniques for shaving and grooming, and they shed a little light on how landsmen, at least, were taking care of their facial hair. (If you're only interested in maritime personal care, this post gets a bit into the weeds on terrestrial soap manufacture, so be warned.) From The gentleman's companion to the toilet, or a treatise on shaving, credited to "a London hair-dresser" in 1844:

There are many soaps which are puffed off as "the best article manufactured for shaving" -- a "beautiful preparation for softening the beard," &c. &c.; but some of them are utterly worthless. All soaps are to be avoided which contain any considerable portion of alkalie; they make a light frothy lather that will not stand on the face, and they will much annoy you by those irritating pains, which are frequently felt after shaving with a bad razor. The soap which I have invariably found to be the best is Naples soap; it produces a beautifully mild creamy lather that will soften the beard, and will render shaving an agreeable operation, and is best calculated to allay those smarting sensations which an indifferent razor produces on a tender skin. There is a great deal of white honey used in the manufacture of Naples soap, and I need not say that there is nothing of a more mild and soothing nature.

Writing in the tail end of the previous century, Benjamin Kingsbury says exactly the opposite in his Treatise On Razors:

[...] Naples soap, so much admired by some persons, on account of the strength of it’s lather, is extremely defective. Of all the shaving soaps in present use, there is not one whose component parts are so irritating and injurious as the soap which is called by this name. It is the most caustic, and, of course, the most destructive to the skin, of all soaps and, in truth, to the production of a needless quantity of lather from a small portion of it, the soundness of the skin of the person using it is completely, and necessarily, sacrificed. [...] the best soap for the purpose of shaving which I have yet made, and which I always use, is the Olive-Soap, composed, in great part, of olive oil, and uniting the advantage of a durable lather with the power of softening and healing, rather than irritating, the skin of the person using it.

(What a drama queen.) Great, cool, but wtf is Naples soap? Thomas Webster's 1844 Encyclopaedia of Domestic Economy describes it as a "strong soft soap, scented; it comes to us in pots. In this era it's still an imported good, so recipes for imitation Naples soaps appear in contemporary books aimed at individual household consumers rather than commercial soapmakers. (Accordingly, these recipes generally seem to involve re-milling or otherwise rebatching existing soaps to add fragrance or combine the qualities of component commercially-available soaps.) Particularly among these imitation recipes, authentic Naples soap seems to be associated with the fragrances of rhodium, ambergris, and musk.

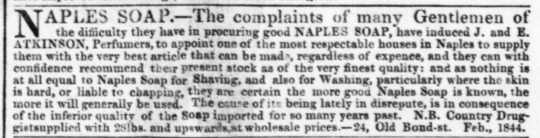

(from the 1844 Illustrated London News, Vol 4, Issue 95. Curious about the disreputable inferior-quality soaps touched on here!)

An 1835 chemical analysis suggests at least one variety used mutton fat as a base fat and potash as its saponifying agent, which is in line with what our London hair-dresser says about lye soaps' insufficient lather. (The existence of this analysis really amuses me -- it seems like people in the US and UK were curious about what really went into this particular import.)

From William Brande's 1848 Manual of Chemistry:

The soaps of potassa are distinguished from those of soda by remaining soft; common soft soap is frequently made with fish oil. Naples soap is a perfumed potassa soap made with lard.

Interestingly, I'm not seeing anyone else mention the "white honey" that our London hair-dresser attributes to the ingredients list here, but honey is a pretty common additive in natural soapmaking, so I'm not about to write it off entirely.

Soft Naples soap isn't the only soap used for shaving in this era -- any number of toilet soaps seem to have been in use, and at least some of these used regular soda lye. Rather than jump right in with potash lye, I wanted to make one of these first.

Shaving Soaps: Take One

Modern home soapmakers have a huge range of tools available to them that even commercial soap manufacturers of the 1840s did not -- digital scales, laser thermometers, Crockpots, electric stoves -- so in this case rather than reconstructing period methods I'm going to try and translate those techniques to a modern toolset.

First, I made a batch of tallow shaving soaps with soda lye/sodium hydroxide -- apart from the use of tallow, this was a thoroughly modern recipe, incorporating a range of vegetable oils to fine-tune the consistency and conditioning powers of the resulting bar. I used equal parts coconut oil and beef tallow, supplemented with sunflower oil, castor oil, olive oil pomace, and unrefined cocoa butter; the only other notable ingredient was powdered clay, both for cleansing powers and increased slip. (You could use white kaolin clay or off-white bentonite clay for a lighter-colored bar; I worked with French green clay because that's what I have on hand most of the time, so my bars ended up a pretty attractive sage-green color. Some people claim that the inclusion of clay dulls their razor blades, but I don’t know that I’m using any given razor blade for long enough for that to matter, and I didn't find it to be a problem when using.)

[Here's where I'd put a photo of these bars in the mold... IF I HAD ONE... so you'll have to settle for this store link.]

What's this bar like to shave with? I'm going to be honest: it's really nice, to the point where I'm considering using it as basically a leave-on mask. I shave with a safety razor and occasionally a wet-dry electric razor, but I don't use a brush to lather up, so I just used my hands with this bar on damp skin; there wasn't a really fluffy voluminous lather, but it made for a really sleek and easy-to-navigate shaving surface and a pretty damn close shave without much friction. The clay component adds a little satisfying tooth to the shaving experience while leaving my face feeling really clean and non-greasy after.

So clearly I like it ,and I've gotten nice feedback from others. But it's not a Naples soap. It's not made with potash lye. What might a more authentic Naples shaving soap look like? If there are other modern takes on a soap like this, I'm having a hell of a time finding them under the search engine optimized-shadow of the Florida-based Naples Soap Company.

What makes a Naples soap?

So to review we're looking for: soft soap, scented soap, animal fat base, and critically, that potash lye mentioned earlier. Potassium hydroxide is an entirely new beast to me -- in soapmaking, it can be used alone or in tandem with sodium hydroxide to create a softer soap, up to and including straight-up liquid soaps. I felt like a horse's ass putting together that, yeah, "potash" really does just come from "pot ash", and "potassium" is just halfassed Latin for the same. If your mental image of old-timey soap making is Almanzo Wilder in the Little House books you're on the right track -- making soft soap was an annual thing for many homesteaders, and the potash was sourced from the previous year's collection of wood ashes.The resulting jelly-like soap got stored in a barrel and doled out as needed. Common salt or table salt could be added to the soaping process for hardness, but in a Colonial American or homesteading context I can't imagine that was always economically feasible.

The barrel approach is in line with what I'm seeing modern soapmakers describe with soft olive oil-based Castile soaps -- you can dilute your soap goo right out of the gate to the consistency of a Dr. Bronner's-type liquid soap (though Dr. Bronner's 18-in-1 soaps are made with coconut and palm kernel oil to supplement their olive oil content these days) but more water means more potential for spoilage, so keeping around a jar of goo and diluting it as needed is a more shelf-stable option.

Period soap recipes are made at scale -- measuring ingredients in pounds, not ounces, and in particular testing the strength of lye solutions by measuring their density against that of a fresh hen's egg. (This method apparently goes back to the sixteenth century and can be used as a rough-and-ready test for a number of different solutions -- for more, check out this post by Homestead Laboratory or this historical overview of the egg test's use in brewing and mead-making from A Booke Of Secretes.

I'm not making my own lye, whether soda or potash, and in fact I prefer to fuck around with lye as little as possible. (Over the course of this project I had the revelation that this is 100% because of the chemical burn scene in the movie Fight Club.) But it behooves me to get familiar with potash lye soaping.

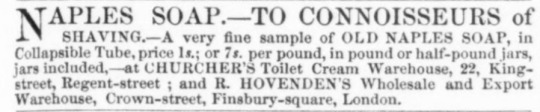

(from The Critic, Vol. XIII, No. 322, 1854)

Shaving Soaps: Preparing For Take Two

So what am I making for my second round here? Instead of a soap cut from a bar or popped out of a mold, I want to make the equivalent of a soap in a pot -- something soft-textured that can be lathered in its container but that's also portable. The descriptions of shaving soap as "soft" don't do me a lot of good -- *how* soft are we talking? Are we talking soft like jelly, like the OG Colonial-style soft soap made with exclusively potash, or just not rock-hard? It's possible to strike a balance between rock-hard and goo-soft by combining both types of lye (what the SoapMaker tool calls a "cream" soap) but I'll need to dig into industrial soap writing from our era to get a sense of whether that was a contemporary historical practice on the initial processing level rather than by rebatching together lye soap and potash soap later.

I’m going to hit up tools like SoapCalc and Soapee's lye calculator for guidance even as I experiment, since soap I'll be sharing with friends isn't a place I want to fuck around with caustic material. Potash lye by itself apparently makes a great soft soap with a consistency I've seen compared to Vaseline (or more bluntly, lumpy goo) but in modern soapmaking terms it's a hot process (HP) soap. Instead of undergoing the saponification process over time as it rests in the mold, hot process soap saponifies while being steadily heated in a vessel like a slow cooker; it still needs to cure afterward, but there's no need for zap-testing and in theory it's usable right out of the gate. HP soaping is new to me as well, and it means I had to get my hands on an estate sale Crock-Pot.

Which fats do I want to use? 100% beef tallow will make a stable and extremely hard soap (even when made with potash) but not with a lot of conditioning or cleansing power; so would 100% palm oil, for that matter. (I did get my hands on some sustainably-sourced palm oil for soaping, but I'm planning on holding off on using it for now.) Olive oil-based soft soaps are gentle and conditioning but don't generate a lot of lather. All these distinct properties of various fats are pretty much how soaps made with oil blends came to be, and those multi-oil soaps are attested elsewhere in the Early Victorian era; one recipe for imitation/homemade Naples soap

I want to put together a scent blend that approximates or is inspired by the notes listed above: rhodium, ambergris, musk. Only problem: What the fuck is rhodium? Later in the Victorian era, George William Septimus Piesse describes it as follows in his Art Of Perfumery:

When rose-wood, the lignum of the Convolvulus scoparius is distilled, a sweet-smelling oil is procured, resembling in some slight degree the fragrance of the rose, and hence its name. At one time -- that is, prior to the cultivation of the rose-leaf geranium -- the distillates from rose-wood and from the root of the Genista canariensis (Canary rose-wood) were principally drawn for the adulteration of real otto of roses; but as the geranium oil answers so much better, the oil of rhodium has fallen into disuse, hence its comparative scarcity in the market at the present day, though our grandfathers knew it well. One cwt. of wood yields about three ounces of oil.

So yeah, for an adult man in 1879, rhodium as a rose-adjacent fragrancing element must have seemed pretty retro. Perfect for this guy's hypothetical grandfather, though. The equivalent listing for rose-leaf geranium describes it similarly as an adulterant or potential alternative for rose otto. The bad news is, rose otto is still wildly expensive, and rosewood itself is now under substantial environmental protection restrictions... as is ambergris. I've got two options in my back pocket here -- fragrancing soap with rose geranium, maybe paired with botanical musk or a synthetic ambergris, or finding myself a nice modern fragrance oil. I... would rather do the former than the latter, but eh, we'll cross that bridge when we get to it.

What qualities am I looking for in the soap itself? What makes a good shaving soap? People have different preferences when it comes to soap lather consistency, especially if you're used to an aerosolized shaving cream. We're looking to strike a balance; lather that’s mild and creamy but not slimy, conditioning and lubricating but not leaving a residue behind. Given my druthers I'd like to make a couple test batches, looking to fine-tune these various qualities, but just how that's going to work out for me will remain to be seen.

So, yeah, soap. Shaving soap. What about the actual process of shaving with it? What's the razor situation? What about the daily ablutions of officers and average seamen? What about muttonchop maintenance? What about the wild world of Early Victorian shaving literature? More on that soon as I document my cold boy hot process soaping. Tune in next time for: goo.

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

Gallipot Project is a go!

My BigCartel store for Early Victorian unguents and potions and whatnot is live! I've taken on the proud name of the goofy little gallipot -- gallipots are mentioned by name in many of the 19th century formularies I drew from for these recipes, and their speculative nautical connection seemed fitting for this project. For the time being I've got mostly creams and salves in stock but I'm hoping to share some perfumes and waters, more weird salves, soaps, and maybe even a non-meaty hair oil.

(Note: The current state of international shipping costs is pretty dire especially for smaller articles like these -- if you're outside North America you may want to hang tight until I've got more products in stock that might offset the shipping rate. I'm working to figure out less onerous shipping options and will keep everybody posted on what I find.)

#amc the terror#unnamed terror fandom beauty project#which is now a NAMED terror fandom beauty project

64 notes

·

View notes

Text

Experiments In Early Victorian Skincare: Bone Marrow Hair Oil

(You can find previous posts on this topic here -- next up we've got some white salves.)

Okay, ngl, this is the part of my self-imposed mission that I have been considering with the most trepidation. Not because marrow oil is objectively, in some way, less clean or more gross than the other rendered animal fats used in hair and skincare products of the era -- I found the process of buying and preparing to handle these marrow bones to be surprisingly unsettling. Not anything about the purchasing process or sourcing beef bones, either, which was as normal and cordial as any other specialty meat purchase I might make -- all I can chalk it up to is looking at the bones themselves and being acutely aware that… hey… crack open my own femur and you'd find marrow there too. [CW for a lot of animal meat, bone, and fat to follow if you're squeamish or prefer to avoid it.]

Marrow holds a horror for me that I find hard to understand in any other terms than the knowledge that I, too, am made of meat -- fittingly given The Terror's themes of subsistence cannibalism, arbitrary European squeamishness, and the smudgy line between human and animal. (In the butcher's shop, one of my friends saw my squeamishness and leaned over to whisper "just pretend you're in The Terror!", so that's where my brand is at right now. She didn't even know about this whole project, just that I'm a ghoul.)

To get the marrow out of these bones, I effectively made the most gross, boring bone broth imaginable -- I pressure cooked the frozen marrow bones (maybe eight-inch lengths of some long cattle bone, around two and a half pounds) in six cups of water for four hours and let the pressure release naturally. When I opened up my Instant Pot, all the remaining shreds of flesh had cooked off of the bones and it was already looking rich and oily The smell of boiled bones isn't gross or repulsive in any way, but it doesn't smell exactly good either, and I made it worse by immediately splashing myself with still piping-hot boiled bone water. The first thing I realized after cussing and tending to the burn was that the remaining liquid was seriously fatty -- the few places it had splashed besides my bare hand were already congealing with milky-colored oil -- and that the cooked marrow slid out of the cylinder of bone all in one piece, no prodding necessary. The bones looked… about like I'd expect boiled beef bones to look, after growing up in a household full of big carnivorous dogs who liked to chew on bones and antlers and stuff, but the inside structures were surprisingly delicate and lacy.

I let the vile bone water cool and thanked my lucky fucking stars I wasn't having to eat plain bone water. My plan was to let the """""broth""""" cool in the refrigerator and then skim the fat from the top, discard any lingering meaty solids and liquid runoff, then melt and filter the rendered fat.

I poured it into a casserole dish to maximize the surface area and promised myself I would wait. I did not wait. I waited like, 4 hours, then broke the cooled layer of fat on top like a pane of ice, picked it off with a spatula, melted it down, and poured the resulting slurry of rendered fat and lingering meat debris into a jar. Including the slurry of meat debris, which rapidly sank to the bottom.

The oil… honestly was much less gross than the bone water had been. It's a nice rich yellow color when liquid and relatively odorless; what smell there was felt weirdly comforting, and then I realized I associate the smell of simmered bones and breaking-down collagen with Amish-style pot pie. (Not incidentally, also a dish that through long-term simmering transforms left-over bones and any lingering shreds of meat on them into a rich fatty broth.) It's hard to imagine a Victorian housewife or thrifty cook balking at any part of this. If I'd been born in 1815, this whole process would have been second nature to me, not a harrowing meat ordeal but a part of the practice of domestic economy. Kind of cool stuff.

I re-heated the oil in a water bath, filtered it through a coffee filter because I can't find my fucking cheesecloth and wasn't super relishing the thought of reusing fatty cheesecloth-- this may have been my undoing because it required several layers' worth of coffee filtering to keep the weight of the hot oil from just blasting through the seams. I was able to extract around four ounces of liquid fat, nearly halved, but a more efficient filter setup could have saved a good chunk of that. My hands got good and lubed up during the process and I really felt a kinship with Ishmael in his A Squeeze Of The Hand rhapsodies, as well as a genuine horror of how much cleanup this was going to take. Straight, I'd say this stuff is uncomfortably rich, and I don't know how easily it'd be absorbed into the skin.

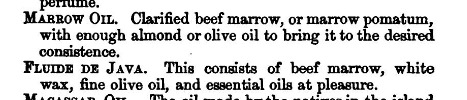

(from Beasley's General Receipt-Book)

What to do with around four ounces of clarified beef marrow? I ended up going wit Beasley's recipe for marrow oil instead of the promised fluide de Java, not wanting to tinker with melting down wax, but not having a frame of reference for "the desired consistence" threw up a hurdle -- seeing it alongside hair oils it seemed reasonable to wager we're going for a consistency slightly more substantial than almond or olive oil alone. but still liquid at room temperature. (Liquid at polar temperatures, harder to say.) I went with a 1:1 ratio of clarified marrow to sweet almond oil, scented with clove bud, cedar, and sweet orange -- I had to go back to up the amount of fragrance after realizing quite how aromatic the marrow still was. (If I had my druthers, I love the smell of clove, but among essential oils it's particularly touchy due to its eugenol content so I kept things below the IFRA threshold for dermal use. If you make any kind of fragranced product, from apparel to solid perfume to baby wipes, you should check out IFRA's standards.

Some of the recipes I see in other texts suggest that the yellowness of marrow-based hair oils is a distinguishing quality, which might explain the use of olive oil in Beasley's fluide de Java recipe; at room temperature the mix has a pale yellow, cloudy consistency while remaining freely liquid. Frankly it still smells uncomfortably beefy. Later writer Arnold J. Cooley could have given me a better sense of the ratio of marrow to almond oil for a marrow-oil hair treatment -- he recommends 3 parts marrow oil to 8 parts almond.

If you're interested in somebody absolutely spilling the tea on the state of the Victorian hair oil retail market, his chapter on it is a treat. In particular he has a low opinion of fluide de Java:

If I were making this over again I'd probably hew to the Cooley measurements, the better to stretch the amount of marrow, and up the fragrance even further -- but I'm already dreading using this stuff on my hair.

32 notes

·

View notes

Text

Experiments In Early Victorian Skincare: A White Lip-Salve

(Find previous posts in this series here.) Finally, a perfectly ordinary skincare item just like every other lip balm and lip oil and lip tint I own, right down to the mutton suet content.

Who's ready to get just so kissable?

TO MAKE ROSE LIP-SALVE

Put eight ounces of the best olive oil into a wide-mouthed bottle, add two ounces of the small parts of alkanet-root. Stop up the bottle, and set it in the sun; shake it often, until it be of a beautiful crimson. Now strain the oil off very clear from the roots, and add to it, in a glazed pipkin, three ounces of very fine white wax, and the same quantity of fresh clean mutton suet. […] Melt this on a slow fire, and perfume it when taken off, with forty drops of oil of rhodium, or of lavender. When cold, put it into small gallipots, or rather whilst in a liquid state. […] This salve never fails to cure chopped [i.e. chapped] or sore lips, if applied pretty freely at bed-time, in the course of a day or two at farthest.

WHITE LIP-SALVE

This may be made as above, except in the use of alkanet root, which is to be left out. Though called lip-salve, this composition is seldom applied to the lips; its principal use consisting in curing sore nipples, for which it is an excellent remedy.

Citing this receipt is an absolute headache -- with minor variations this basic formulation for both red and white salve shows up in texts from the 1810s to the 1850s. You can find it in The Complete Servant, A New Collection Of Genuine Receipts, Mackenzie's Five Thousand Receipts... I swear this shit is like recipe blogging, minus the long copyrightable prelude. Tl;;dr, this recipe would have been in contemporary use at the time of the final Franklin expedition, but it would scarcely have been brand new.

Batch One

almond oil

beeswax

raw cocoa butter

sweet orange oil

Geogard ECT (a lip-safe, broad-spectrum natural preservative -- I bought it with watery pomatum use in mind but figured, fuck it)

Okay, so I lied about the suet, I'm sorry and I'll try to do better in the future. This is absolutely the most normie of these recipes as far as I'm concerned, after reluctantly subbing out the aforementioned mutton suet for an equally fragrant but much more anodyne fat, cocoa butter. It's a pretty standard recipe for a firm salve like I'd make with any other infused oil, though I'm skipping the alkanet here for firm and masculine Royal Navy reasons. Everything melted together readily enough in my DIY bain-marie, but I first smelled trouble when the fully melted liquid in the boiler had its own separated particles of fat. While the liquid still poured like a dream the resulting salve had tiny, faintly gritty blooms from the cocoa butter component on top as soon as it had cooled. The odor of raw cocoa butter — not unpleasant but definitely bitter — warred with the smell of orange oil, and while the consistency is certainly pleasant enough on the lip it wasn't everything I'd hoped for. I'm pretty spoiled for only the most modern and standardized commercial projects, so this minor variation troubled me.

Batch Two (pictured here alongside some cold cream tins)

olive oil

beeswax

shea butter

sweet orange oil

Geogard ECT

For batch two, I did indeed use olive oil, paired with shea butter as has become my usual suet/tallow substitute in these experiments, but I found myself with a problem I hadn't considered: what, to an early Victorian, makes olive oil "the best"? We can probably assume this excludes obviously-oxidized, rancid, or adulterated oil, but would a Victorian cook prefer a pungent, peppery oil or a mild one? Would they be accustomed to working with a Mediterranean mainstay like olive oil at all?

Mrs. Beeton's Book of Household Management gives an outline on the uses of olives and their oil that sure makes it sound like a common enough ingredient in the middle-class English home, albeit one of limited usage:

There are three kinds of olives imported to London,-- the French, Spanish, and Italian: the first are from Provence, and are generally accounted excellent; the second are larger, but more bitter; and the last are from Lucca, and are esteemed the best. The oil extracted from olives, called olive oil, or salad oil, is, with the continentals, in continual request, more dishes being prepared with than without it, we should imagine. With us, it is principally used in mixing a salad, and when thus employed, it tends to prevent fermentation, and is an antidote against flatulency.

But Mrs. Beeton gives us no clues about what flavor profile is to be preferred or how to distinguish a good olive oil from a bad one. Modern preferences regarding olive oil in the US and UK alike are shaped by 20th-21st century fashions in cuisine and diet, from Tuscan cooking and the Mediterranean diet to concerns about free radicals and triglycerides -- I prepared this batch of salve with the tail end of a bottle of imported EVOO, certainly a product of all those influences -- but after all, we're not eating this stuff outright, we're just rubbing it on our lips, or nipples. The perfumer Charles Lillie makes an assertion about the forms of olive oil most suitable for mixing with fragrance:

(He also marks out the best olive oil in terms of its price -- fourteen shillings per gallon in 1825, around £52 GBP adjusted very broadly for inflation. Which doesn't help me now, but ok, cool.)

What if we look earlier? Friedrich Christian Accum's 1822 treatise on the adulteration of commercial goods warns of the risk of contamination with lead, and of the deliberate dilution of olive oil with other oils like poppyseed, not unlike the modern traffic in counterfeit EVOO. "Good olive oil," by Accum's definition, "should have a pale yellow colour, somewhat inclining to green; a bland taste, without smell; and should congeal at 38 degrees Fahrenheit." So it certainly sounds like the pungent, peppery oil I might use for the dinner table (or indeed on a salad) is right out, but gorgeous Georgians and vile Victorians were out here performing DIY tests for detecting adulterated oil just like I am when I get paranoid about my California Olive Ranch EVOO being secretly 90% canola or something.

Olive oil was even more popular with 19th century pharmacists than with salad-makers due to its abundance of applications, both external and internal. (In the spirit of my original meta, I have to say here: lube.) Even so, would a salve like this one really find its place aboard a polar expeditionary ship? A rosy alkanet lip stain is right out for most occasions, but chapped lips and chapped nipples are facts of life in all climates, and I don't have any reason to think personal sundries along the lines of Crozier's ill-fated tea and sugar would be excluded from officers' belongings, perhaps those of ordinary ratings as well.

Gentlemen in the civilian world and Royal Navy alike might stock their own medicine chests for travel and day-to-day use; these chests contained independently-sourced materials making for a range of self-treatment options for complaints both minor and major. The National Maritime Museum currently holds one of Sir John Franklin's own medicine chests, looking very handsome with brass fittings and its own set of scales for dosing; fellow Arctic explorer and Franklin searcher Sir William Edward Parry owned another glorious example of the same, handsomely made and stocked with painkillers, laxatives, and much more. Judging by its survival it's evident Franklin's own chest wasn't recovered from any wreck, but we know that the final Franklin expedition carried at least one communal medicine chest aboard, as it was found abandoned at Victory Point.

This chest isn't one of the luxe private articles marketed to gentlemen like Franklin and Parry but a prosaic piece of luggage intended for organization-wide use. Alongside opium, camphor, ginger, and Tolu balsam the Victory Point chest contained peppermint oil and a two-ounce bottle of olive oil. No one would waste such things on a remedy for chapped lips, certainly not at the "abandoning our ships and sledging to our doom" stage of the expedition, but it seems plausible enough to me that the private version of one of these chests might contain a personal care product like this one, whether homemade by a loved one or purchased as a commercial item from the same pharmacist who sourced the more potent medical preparations alongside it. Maybe more realistically, such an item would find its place alongside hairbrushes and tooth powders -- as more and more materials are able to be recovered from the wrecks of Erebus and Terror, I'll be really interested to see what further personal items are able to be recovered.

If you're interested in the contents of these personal medicine chests and that of the Franklin expedition chest, please run, don't walk, to Dr. Marieke M.A. Hendriksen's wonderful paper "Consumer Culture, Self-Prescription, and Status: Nineteenth-Century Medicine Chests in the Royal Navy". (Hendriksen does wonderful work around the material culture of medicine in general and I'm so jealous in the best way of her work around Early Modern consumption and taste.) Richard J. Cyriax's 1947 article "A Historic Medicine Chest" treats the individual contents of the Franklin chest in some detail, and is absolutely worth a read. There's another topical remedy for skin ailments lurking in Cyriax's account of the medicine chest contents that I'll be getting to very soon in this experimental series…

Would there be any interest in a tinted version of this salve that does incorporate an alkanet infusion? I've made so many individual salves and balms and whatnot as a part of this project that I'm planning on putting them up for sale on BigCartel; Etsy would be way more convenient apart from every other thing wrong with Etsy as a selling host. Let me know too if there's any other kind of receipt recipe from this era you'd be interested in seeing and trying, even if it's more likely to be found in the civilian world than at sea.

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

The days are getting longer and we're on our way out of Ice Hell at last... hopefully... so use the code COLDBOYS for 30% off on my BigCartel store through April 1! I've got some new 1840s skincare and beauty items coming up soon once they've had a chance to rest and I'd like to make some room in the area of my fridge dedicated to weird balms.

What's new: finally a specific attested historical item! I made up a batch of pine resin salve from the formulation given in the Edinburgh New Dispensatory. (As usual, minus the lard, but if you're hankering for a meat-based variation let me know.) Cyriax posits that this is the mystery dried-up ointment in the tin labeled "Ground Ginger" found among the medical supplies in the chest left at Point Victory; unguentum resinae (unguentum resinosum if you're Scottish and/or fancy, aka basilicon ointment) was in common 19th century use for dressing blisters and burns, both for the antimicrobial/counter-irritating qualities ascribed to pine resin itself and its adhesive properties in conjunction with dressings. Feel free to use on sore joints, dry or windburned skin, or as part of a funky little chest rub for congestion, but please don't dress any suppurating scurvy wounds with this stuff or anything else.

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Gallipot Project now has an Etsy store! The same stuff will be listed here as on the BigCartel site but it's hopefully a bit more findable and trackable for people outside the very small venn diagram intersection of "following me on Tumblr" and "wants to buy Early Victorian-inspired personal care sundries".

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Gallipot Project is going on summer vacation from 6/21-6/30! You can still make purchases during this time, but orders will not ship out to anybody until I'm back on land. Some other updates:

Sucked it up and made a freestanding Wordpress blog just for the formulary/making-of posts so nobody has to go wading through my Tumblr unless they want to. All of my posts on researching and making skincare/beauty products of this era will be crossposted there if you'd like to keep up without seeing 900 NBC Hannibal gifsets.

Coming soon to the blog: unguentum resinosum and a primer on 1840s shaving and shaving soaps

Coming soon to the shop: Windsor and Naples soaps, egg yolk facial soaps, Disco Hickey highlighters, and other sundries...

Are there any products you'd like to see or any questions you have about Early Victorian men's personal care and beauty products? Please let me know either here in the replies or at [email protected].

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Rose lip salves are a go! (Also on Etsy if you're a big fan of suffering and/or free shipping on orders $35+.) The tint on these is quite sheer but I've got the turbo-charged version in the works as we speak.

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

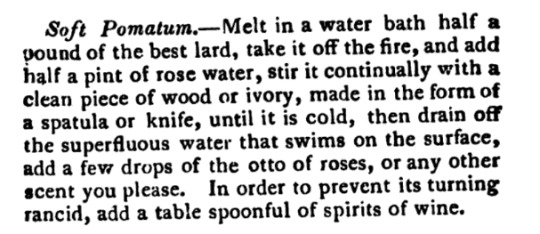

Experiments In Early Victorian Skincare: A Soft Pomatum, Mk. 1 🍊

Recipe from H. Gifford's General Receipt-Book, or Oracle Of Knowledge, 1824. (This one seems to have done gangbusters in reprints, and other receipts collections ripped off its contents fairly freely… oh well.)

This was easily the most straightforward of the recipes I chose, but with one wrinkle. My first test batch was fairly small, about two ounces of shea butter (my meatless lard substitute, for now) and a corresponding amount of rosewater. It all melted together like a dream in my DIY bain-marie, but perhaps due to the fat substitution, I didn't have the advantage of the rosewater imparting its fragranced elements and then rising to the surface as the fat cooled. I was effectively skimming off the semi-liquid shea from a pool of rosewater (and spirits of wine) as the shea butter cooled and then rose to the surface.

I'm looking forward to trying this one with animal lard, but I have real apprehensions about how shelf-stable this recipe would be given the unavoidable residue of water left behind. I have murky plans to sell the proceeds of this project depending on how the results turn out, just to offset the cost of my tinkering and share a weird craft with fellow fans/historical cosmetics people, but I'd be a lot more uncomfortable slinging weirdly moist pomata via the postal service, spirits of wine or no. While this dismayed me, at least I'm not the first person to encounter this problem with early Victorian skincare recipes.

(From Henry Beasley's The druggist's general receipt book, 1850. you're telling me a nonbinary person wrote this footnote???)

The extremely unscientific poll I did on Twitter wrt the use of animal fats in this project came back fairly inconclusive -- more people in favor of non-animal fats than animal fats, but more people saying they didn't care or just wanted to see what other people voted for than either. I'll give both options a try, but both tallow and lard -- presuming "top-quality lard", which many receipts books specify outright, and not a big block of hydrogenated Armour lard -- are pricey enough that I'm holding off for now. In my quests to source lard and tallow for future experiments, I found out a lot of people are getting back into using animal fats for skincare, which weirds me out a little but encourages me that I won't be the weirdest person buying animal fat at the butcher's this month.

I will say, this one is ludicrously moisturizing -- I would definitely cherish this stuff like gold in a polar climate. It's heavy enough that I'd be more comfortable using it as a moisturizing salve for dry bits like hands and elbows, but I don't think it'd be likely to harm hair at all, and for fanfiction purposes only, it seems like it would be fine to use to lube up a butthole. It's firm at room temperature, but warms up easily if you rub it between your hands.

The fragrance of rosewater was absolutely negligible, not sure whether to chalk it up to an inferior rose water (might try this with a bottle I got years ago from Nielsen-Massey that smells like an absolute ass kicking) or the qualities of the fat involved. In lieu of wasting my precious otto of roses, which I'll need for Fitzjames reasons later on, I opted to fragrance this with a few drops of benzoin gum after warming the bottle in a hot-water bath. (I'd describe benzoin gum as… technically liquid in this form, but extremely viscous, unlikely to comply with a Euro-style essential oil dropper. I've got hard crystals for use in incense, but I didn't need to bust them out in this case. Overall the smell is a very smooth, almost gourmand incense note, not at all dank.) Benzoin resin is used as a fixative for other fragrance elements, and it's innocuous enough to be widely-used in cosmetics and confectionery; a few drops added a subtle fragrance here that I enjoyed.

If the rosewater route doesn't work out, there's always another option from Gifford. I really think I need to play around with the relative melting temperatures and consistencies of different fats here, but the comedy value of making a hard pomatum bar is not lost on me. IIRC there's a recipe for hard pomatum in this style in one of the American Duchess books (not surprising given its earlier publication year) and they use a Star Wars-themed silicone mold, which gives me great joy.

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Early Victorian Skincare: Experimental Archaeology For Dorks

I am coping with work stress in a very normal and healthy way, which is to say, I have begun my Unnamed Terror Fandom Beauty Project. My aim in this project is to make some of the historical grooming and beauty products I researched for my 1840s Hygiene & Personal Care For Cold Boys meta, document the process, and share the results. My biggest concessions will be sacrificing the whale byproducts that were dead common in 19th century cosmetics, but this was the kick in the butt I needed to finally buy one of the lab-created ambergris alternatives. I hope to recreate the fully meat-based versions of these products, but my gameplan is also to sub all that lard and suet for stuff I can send by mail without feeling like a ghoul. (The marrow-based stuff like the fluide de Java... we'll cross that bridge when we get to it.)

Currently I'm planning to recreate a hair pomatum, a skincare pomatum that's more like a cold cream, a lip salve, and two perfumes. (Are they Fitzjames and Crozier-themed? Maybe.) Time will tell how this thing progresses.

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

An Early Victorian Hair Care Special: Trying Out Marrow Oil

I had fun Jirving-larping for a bit today and trying out the beef marrow oil I made a few days ago. It was already my hair-washing day and I hated having the bottles sitting around accusingly in my workspace so I gussied up a bottle I'd set aside (containing basically the dregs of what I'd mixed up, with a few remaining flecks of marrow down at the bottom) with lavender oil to counteract the lingering beefiness. (Suddenly understanding why so many pomatum recipes involve multi-step washing of your tallow and lard in floral waters.) Then, with comb and brush in hand, I went to try this shit out.

My hair is pretty short, very straight, very fine, and distinctly thinning, so I figured all of that made me a good test case. (Hodgson sun, Irving moon, if you will.)

Before pics -- I briefly entertained wearing my 1840s waistcoat for these pics but the thought of getting it oily did not appeal to me. My hair does not like lying flat.

And after! This shit is so excited to lie completely flat! The marrow oil mix went on with a heavier, richer consistency than plain almond oil -- zero surprises there -- but it kept my hair where I'd laid it through both combing and animal-bristle brushing. Even when I tried to muss it, it resisted. The smell was perfectly pleasant, if a little more warm and animalic than I was used to, but more significantly this shit was super fucking shiny. The camera doesn't really capture it here thanks to piss-poor lighting but as soon as I started brushing, Bluntly, I think the look would be more dramatic on someone with thicker hair than me -- it doesn't take much for my hair to look pretty stringy, but I can imagine this but the glossiness made it worth it. The richness and heaviness of this oil must have been a comparative boon in an era where gentle sulfate-free shampoos were not really a thing.

(Lads, let's make Eli Sunday-core happen.)

So... verdict, idk if this is going to replace all my cupcake-scented sprays and pastes and shit day to day, but it didn't make my hair fall out and it gave me that authentic "plastered down in the wardroom" look. I'd love to try a bear's grease recipe, but since actual bear's grease is in fairly limited supply and has legitimate health uses in North American Native traditions sourcing it in a way that's both ethical and local (especially out of hunting season) would be a challenge. Most bear's grease retailed in Georgian and Early Victorian Britain hadn't been any nearer to a bear than the label on its jar; extensive adulteration with other cheaper animal fats was the norm, including rancid fats in a bluffing attempt to mimic actual bear fat's pungency. ("It stinks, so it must be legitimate" was the precursor to "it tingles, that means it's working".) So I could certainly do a bogus "bear's grease" recipe, if I didn't mind subbing out a whole lot of lard. What are your thoughts? Has your polar expedition-LARPing or historical costume work extended to historical haircare?

(image: bear's grease labels, Wellcome Collection)

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

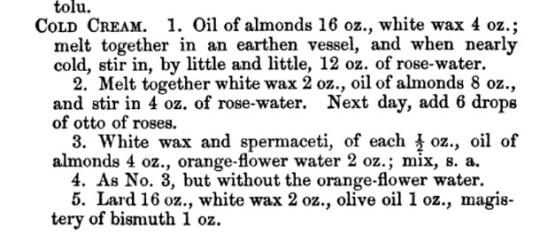

Experiments In Early Victorian Skincare: Rosewater Cold Cream Pomatum

Let's make some cold boys some cold creams! This one is a pretty big stretch for use at sea, for reasons I'll outline later, but bear with me.

(Sarah and Samuel Adams' The Complete Servant, 1825, and every other collection of receipts since between then and 1850. This shit got passed around like copypasta. In this context a gallipot is a small ceramic vessel used by pharmacists for storing ointments and compounds -- my containers in this case are a lot less cute but a lot more functional.)

My modern version of this recipe, (scaled up considerably) 8 fl oz sweet almond oil 0.5 oz beeswax 0.5 oz jojoba oil (by weight) 8 fl oz rosewater

(Later reprints omit the balm, and it’s not clear to me if they want herbs or balm water, so I omitted it too. I’ve got Carmelite water infusing as we speak so I’ll never in the future be truly balmless.)

The last floral water pomatum I mixed up came with instructions to pour off the floral water once it got good and melded with the fat and wax components, but in this recipe the floral water itself becomes incorporated in the final product rather than just its fragrance.( Due to the amount of water in the recipe, I did introduce into the mixing final stage a small amount of a broad-spectrum natural preservative, Geogard ECT. I had concerns that this would impact the consistency but it doesn't seem to have done it any harm -- I'll talk later about why water made me eeky.)

Cooled and beaten to a consistency like whipped cream, the recipe seemed to be coming together nicely, forming an opaque emulsion that reminded me irresistibly of Hollandaise sauce. (Not, like, in color or smell or taste, I just really like Hollandaise and I don't make a ton of other emulsions on a regular basis.) Everything looked and smelled great. I chilled the batch I made in the refrigerator both to hasten potential separation and to see how stable that emulsion ended up being.

…and the answer was, not very! Leaving a jar of this cream out in my warm kitchen gave me a taste of this product's stability -- when chilled it maintains its fluffy, whipped texture but as soon as it settles at room temperature the rosewater begins to separate, forming essentially little droplets of rosewater scattered throughout a more solidified cream. There's nothing unpleasant about using it in this form, and the combination of moisturizing elements and actual moisture still do the trick, but it's a bit less glamorous.

Did I simply not beat it enough? Did it separate due to warmth? Did I fuck up my ratios? The 18th century perfumer and snuffmaker Charles Lillie gave me some not very helpful advice regarding temperature:

Also I'm pretty sure that's not how evaporation works.

But even if honey-water isn't on the table his recommendations regarding wax are still spot-on -- the only emulsifying element of these earliest cold cream formulations is beeswax, and at this proportion it's not powerful enough to keep the oil/water combination stabilized for very long. These pomatums will be just fine to use, and they feel great on the skin -- I've been using this cold cream on my hands for a while now, which have been pretty fucked up from the amount of cleaning and scrubbing I've been up to as part of this project, and it rules -- but the potential for separation is a bummer. I'll be keeping these tins in the fridge. Due to the delicate nature of this particular skincare aid, I find it hard to imagine anyone bringing it from home in a polar context, or having it prepared while aboard unless they were seriously committed to maintaining their skin's moisture barrier. Lady Jane Franklin, ashore in England, would have no trouble keeping her hypothetical stockpile of cold cream in optimal conditions, but her husband less so. Still skincare of the era and old enough for both the Franklins to have grown up with in their Georgian-Regency youths, but not exactly a handy portable preparation like its waterless sistren.

In general, water content is the death knell for a lot of DIY skincare products, making space for bacteria and mold -- every time I mention using an anachronistic preservative, even a natural one, I wince, but especially for a product like a cream or balm where you're going to be scooping it out with your fingers or touching it for the duration of its use, I found the prospect of sending a bunch of people the perfect little breeding-ground for meecrobes just too horrifying a prospect.

Can you make a cold cream without water? Beasley gives one such recipe, if in an annoyingly coy way, and the ingredients are no shocker -- just add more oil.

I scaled this recipe up a bit after double-checking in a panic to make sure I wasn’t going to be making another salve with identical composition to my lip salves. I also tried a slightly different substitution for spermaceti than before, thinking I might have been mistaken about the typical consistency of the product pharmacists were working with -- it was a bit of received wisdom to me that jojoba is a pretty good swap for historic cosmetics, but later formulatories from the early 20th century specify grating the spermaceti in a way that suggests a stiffer consistency. Mango butter is pretty stiff and brittle at room temperature, but it melted down just fine (would have melted even easier if I microplaned it first, I bet) and it's supposed to be good for both skin and hair without being quite as heavy as, say, beef marrow. With no obvious fragrancing element on par with the previous recipe's floral water, I wanted to figure out something that was a) pleasant b) comprised of materials attested in pre-1850 formulatories c) in line with modern recommendations regarding topical hair and skin use. I settled on rosemary, cedarwood, rose otto, benzoin resin, and myrrh.

(…unfortunately, this combination smells really good to me, so I will also be incorporating it into my rapidly-growing stable of perfume oil trials. I'm not tempted to rub this one on my face, but I'll be using it for hand skin and wearing it as a solid perfume.)

So what's the result like? It's very nice, but it's not creamy, and it's not cold. (And it definitely didn't whip up like cream, at least not the way I tried it. Maybe I should have beaten it for longer.) While it's nice for skincare purposes, and certainly more stable for travel purposes, I can't imagine it really scratching the same beauty itch as a more moist, pillowy formulation.

What are other ways to emulsify your cold cream? Well.

(Robert Eglesfield Griffin, A Universal Formulary: Containing the Methods of Preparing and Administering Officinal and Other Medicines, 1850)

Borax is certainly an emulsifier, albeit one I find wildly intimidating. It occurs in nature, it was certainly known by the 1840s, it appears in published cold cream recipes since at least 1825 and it still shows up in skincare today -- but its usage in modern skincare has a lot of controversy surrounding it. Moreover, half a drachm (by weight) of borax to six fluid ounces of carrier liquid is a stronger concentration of borax than a lot of modern products possess, and I just don't want to fuck around with skin pH if I can avoid it.

That's not to say that I'm without other options! Later cold creams commonly incorporate glycerin as an emulsifier as well as a bonus humectant; variously-derived forms of glycerin had been known for several decades by the point we're dealing with, but its primary purpose in the formularies of the 1840s is in the treatment of hearing loss. (Which I was ready to dismiss as one of the odd quirks of the era, like rubbing turpentine on everything, but "the glycerol test" has persisted into the 21st century as a diagnostic tool for Menière's disease.) Beasley includes one such glycerin-based recipe in 1850 but I'm not seeing it any earlier, so I'll have to do some more digging and see what I want to doctor up.

So how do you disseminate a product that separates easily, wilts in warm weather, needs a ton of stirring and whipping to get that nice creamy consistency, and requires a shitload of floral water? Very carefully. You basically had to make this stuff in small batches, rather than one big batch to be doled out over the course of months or years. Historian of cosmetics James Bennett summarizes:

Their short shelf life meant that cold creams were usually made up at home or purchased in small quantities, freshly made up by a local pharmacist, chemist or druggist. The ceramic pots they were sold in turn up frequently in Victorian-era rubbish tips.

Bennett's piece on the historical timeline of cold creams is definitely worth a read if you're trying to figure out how we get from super-perishable 1840s vegetable oil-based cold creams to the the super-rich, damn near indestructible mineral oil cold creams of the 20th century.

If you want a treat, take a trip through auction sites and see the many gorgeous and weird designs used on cold cream pots in this century -- most of the truly fabulous ones are from the second half of the 19th century when mass production of these designs became possible, but damn if they aren't cute.

(Source: Cache Antiques)

(source: Cache Antiques)

(source: 1stdibs)

(source: Whytes)

Thanks so much for all the positive feedback and enthusiasm this project has been getting! I've got an online store now (Gallipot Project) to accompany this project where I can share my findings and offset the costs of all my weird animal fat and floral water purchases by selling what I've made. The store had the softest of soft launches earlier on my private Twitter and with the proceeds I was able to source some tallow for making not only salves and pomatums (pomata…) but hopefully some white Windsor soap. Don't feel obligated to buy a damn thing, but I've got salves and cold creams up for sale now and very soon I'm hoping to share some tinted salves and historical perfumes, as well as one weird unguent with a fascinating historical pedigree and a very strong Franklin connection.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

The first orders have all been delivered! Get yourself some balms and salves and unguents -- in the morning I hope to list some rose lip salves and I'll do a writeup on my adventures in historical cosmetics pigments.

Gallipot Project is a go!

My BigCartel store for Early Victorian unguents and potions and whatnot is live! I've taken on the proud name of the goofy little gallipot -- gallipots are mentioned by name in many of the 19th century formularies I drew from for these recipes, and their speculative nautical connection seemed fitting for this project. For the time being I've got mostly creams and salves in stock but I'm hoping to share some perfumes and waters, more weird salves, soaps, and maybe even a non-meaty hair oil.

(Note: The current state of international shipping costs is pretty dire especially for smaller articles like these -- if you're outside North America you may want to hang tight until I've got more products in stock that might offset the shipping rate. I'm working to figure out less onerous shipping options and will keep everybody posted on what I find.)

64 notes

·

View notes

Text

It’s not enough to do a full update post on, but… if you’re dying to get your hands on your own beef marrow hair oil, I’ve got five 30ml bottles for sale!

Impress your employers, gross out your friends!

Gallipot Project is a go!

My BigCartel store for Early Victorian unguents and potions and whatnot is live! I've taken on the proud name of the goofy little gallipot -- gallipots are mentioned by name in many of the 19th century formularies I drew from for these recipes, and their speculative nautical connection seemed fitting for this project. For the time being I've got mostly creams and salves in stock but I'm hoping to share some perfumes and waters, more weird salves, soaps, and maybe even a non-meaty hair oil.

(Note: The current state of international shipping costs is pretty dire especially for smaller articles like these -- if you're outside North America you may want to hang tight until I've got more products in stock that might offset the shipping rate. I'm working to figure out less onerous shipping options and will keep everybody posted on what I find.)

64 notes

·

View notes