#unethical jobs exist. it is everyones job to bring them down

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

i hate how normalized military is in the us im gonna rip my hair out

#i just. was talking w friends today#one of them was talking abt how he was almost convinced by the recruitment lady to join the navy and i was like. dude#and i was talking about how messed up it is that they send in people like that and catch kids like him#and my friends were like. you cant really blame her for doing her job. its her JOB like yes. it is her job. its fucking Bad#my best friend got all angry cuz his dad was in the navy. babe idc if he didnt actually fight he shouldnt have done it ♡#''people get drafted'' you have to dodge the draft.#''thats illegal'' yes. this is a requirement for if you are drafted. you Have to just not.#no one said action would be comfortable nor convenient. in fact it is going to be almost none of either#you are gonna have to face that the military murders human beings and your dad is not any better#and people who its ''just their job'' to do it chose that job. and they know#''you cant get mad at the worker woman; you have to get mad at the institution'' no im mad at the individual woman too#just because its your job to manipulate kids and kill Arab people doesnt mean its okay#''not everyone in the military is actively fighting'' no! they arent. but they are helping those that are.#they are not complicit but actively helping. you have to do anything and everything you can to just Not Fucking do that#ANYONE in the military has failed being a decent human 101. being in any part of the military means you are okay with centuries of genocide#and encourage even more. its not 'just your job' you are OK and more for relentless murder and i wish you harm#anyways. sometimes repeating & internalizing the things ur parents say means watch our for road traps and the beatles are good.#sometimes it is US propaganda and just because it is in your own house and coming from a loved one doesnt mean you cant not fall for it#edit not to mention him saying this the day after aaron bushnell died. dude#unethical jobs exist. it is everyones job to bring them down#''its just her job'' was Bushnells sacrifice not fucking enough for you??? and the millions of dead Palestinians????? christ

10 notes

·

View notes

Note

HC on a modern fallout. Like same characters just in now times.

Like Obvs Nick would still be a PI but what of the others? Would factions be a thing still or would they all have normal jobs?

What of the synths?

Modern Fo4 Headcanons

➼ Word Count » 3.3k ➼ Warnings » Spoilers for many character arcs ➼ Genre » Modern AU ➼ A/N » This took me WAY too long, but I had so many things I wanted to write down and expand on.

COMPANIONS [ these are how I imagine them before meeting Nate and Nora, a random couple who just happens to enter into everyone's lives ]

MacCready grew up as an orphan in Virginia where the older kids raised him. He never got adopted and, while he was thankful for the teens who raised him, there was always a sense of abandonment and negativity that he'd always attach with the state. So, when he turned 18, he hitchhiked to Boston, hoping to find a happier and more fulfilling life. It didn't happen as soon as he'd wanted, however, and he bounced from place to place looking for a stable job. His rugged exterior and immature attitude forced him out of a lot of areas, but there was a group that didn't mind any of that. MacCready was ecstatic when the Gunners first picked him up. They gave him jobs, sure, but they had also given him a group he could identify with in the same way he did with the kids back at the Orphanage. After a year of working with them, MacCready met Lucy. He'd originally planned on robbing her, but her name reminded her too much of the Lucy he'd grown up with, and offered to walk he home instead. When they had gotten to her door she asked him about why he was wearing army pants. He jokingly told her that he was in the military who was currently on leave, which she ended up believing. It surprised MacCready since his Gunners tattoo was visible on his arm, but he found her gullibility to be endearing. After that, the two spent a lot of time together, but right after Duncan was born, she pieced together his association with the gang, left him, and quickly moved into an apartment located in a safer area. Heartbroken and consumed with guilt, he quit the gang for good and worked to better himself and clean up his act so that he could be a part of his son's life, and maybe try his relationship with Lucy once more. He does a few odd jobs here and there but, so far, none of them have stuck.

Once Nick's testing was over, the students at CIT didn't know what to do with him other than to let him roam the campus, so he stuck with what he knew - police work. He'd wander the college as an officer, looking for any job or event that could require his help. At first, he was treated more as a Protectron than an actual member of the force, but that never really bothered him, as long as he was actively making people safer, then he was content. What did bother him, however, was the amount of jury trials he had to be present at for being the product of unethical testing. It always made him feel guilty that he was an unconsented clone of the real Nick Valentine's mind, and if he could, he would've chosen not to be created at all. Knowing the amount of pain his existence had caused an actual person made him feel awful, but he'd rather put that energy into his community over hating himself for something that was out of his control. He never really got over the confusion and sadness he had when he thought about who he was but, over time, many of the students began to treat him as if he were a real person. They'd greet him in the mornings, buy him ties on special occasions, and every once in a while someone would bring him coffee, forgetting that he couldn't drink it. His life slowly changed from him not understanding what his purpose was, to becoming a well-respected member in his field. Even the real Nick grew to appreciate him after he helped to hunt down Eddie when no one else wanted to. His memories of DiMA were still there (as it had only been a 2 or 3 decades compared to 2 centuries), but his brother didn't stay with the school, instead opting to discover himself elsewhere. As soon as he was allowed, he left for Maine and made a name for himself as the first robotic philosopher and occasionally sending letters to Nick.

Cait ran away from home at 15 in an attempt to escape the abuse she received from her parents. Scared, alone, and incredibly fragile, she was an easy target for many others on the streets and was taken advantage of both emotionally and sexually by almost anyone who saw her. As the years went by, the more hardened and angry she had become. Finally able to adapt to her surroundings, she stole, fought, and threatened anyone she could. This led her to be put in many juvenile detention centers and child reformat camps, both of which never helped change her view on the world. Still living on the streets at 18, she went and bought her first gun. She thought of going to visit her parents for a while, wondering if it would make some of the pain she felt go away. On the day she decided she was finally ready to go kill them, she ran into Tommy, a sleazy businessman who was desperate to strike it big in the corporate world. Seeing the potential and opportunity that a young, angry, mistreated girl could present to him, he offered her a deal. If she focused her rage into wrestling and let him be her manager, he'd help her get off the streets and really make a name for herself. She agreed and very quickly became one of the best and most well-known wrestlers in Boston, although, most of the press that covers her is about her attitude and allegation regarding her addictions. She still holds onto that shotgun she bought. It reminds her of what could've been and helps her feel a sense of security. She knows no one will take advantage of her again because she now has the means to ensure of it. She's still waiting for the day her parents beg her to take them back so she can tell them off, but they never did. It hurts her more to know that, even now that she's found success for herself, her parents still don't want her. So, until it kills her, she'll drink and inject herself with whatever she can get her hands on, desperate to numb as many of her thoughts as she can until she passes.

Danse was also made at CIT, although he's much more advanced than Nick is. Almost immediately after being created, he left to go to DC where he met Cutler. Cutler was on the verge of homelessness and pitched his idea of starting a small business to Danse who agreed quickly (he had no other plans). They sold odd things they either built or found for a few years before they were approached by a general in the US Army. He was only browsing, but Danse felt compelled by his stories from when he was in combat. There was something about serving his country and defending the common man that he found to be incredible, and so he and Cutler quit their gig and signed up for the army. There've been robots who've joined the military before, but none who made the decision on their own volition. All the others are Assaultrons and Mr. Gutsy, so having one who willingly wanted to be a part of the cause was astounding to many. Cutler eventually got mortally wounded and Danse, who was clearly devasted, was then assigned to work with Haylen and Rhys out of fear that he'd go haywire or malfunction due to the impact of his friends death, and that's where he's been ever since. The memories he'd been given were vague and slightly foggy, but the army gave him something to identify with and a cause to work for. He was prideful in the work he did and, although there were others, he served to be one of the first instances of a robot showing a willingness to fight for his country.

Ever since he was young, Preston had looked up to those who did right by people. At first, he joined a police academy to be an officer, but after a bystander got caught up in one of the scenes he'd been sent to, he quit, deciding that this wasn't something he was cut out to do. The guilt of not being able to successfully protect an innocent civilian eats away at him, so, in an attempt to make it up to himself, he went into hospice care. At least here he knows the deaths aren't his fault and that all the people he cares for have lived long, fulfilling lives. Currently, he's caring for the long-time addict, Mama Murphy (who still manages to sneak a few pills into the room every now and again). Preston adores her, but every once in a while she'll tell him about a dream she's had where the world had ended and he played a part in rebuilding it. He can't let her describe it for long, though, otherwise she'll start to panic and he'll have to grab her medication to help calm her down, and he hates having to give her drugs. Luckily he knows that she's just and elderly woman suffering from schizophrenia and none of what she says about a war torn world holds any truth. As much trouble as she causes him, Preston isn't sure what he's going to do when she's gone. He only hopes that it doesn't shatter him as much as the bystander incident did.

Codsworth still operates under Sole's roof in taking care of Shaun and the home. Nothing changes with him, however, when he went to drop Shaun off at college for the first time, he met Nick, and the two got along quite well! Whenever he goes to visit Shaun with the family he always makes sure to stop by to chat with the detective.

Piper runs a very controversial newsstand right in the heart of Boston. There are so many authorities and higher-ups whose reputations have been ruined due to her articles, and even with a mob of protestors against her, she still does whatever she wants. She grew up in a smaller town on the outskirts of Massachusetts before she managed to work up enough cash to get herself and Nat to the city, where she could finally begin to look for work to support them both. However, she quickly found that the 'big city' had many issues on its own and, since then, she was dead set on bringing people's attention to them. She doesn't care about the death threats or riots that sometimes occur outside her home. The police know her well enough by now to keep an eye out in her neighborhood. Especially Nick, who met her once while she set up a debate booth on campus and interviewed students for an article she planned on publishing. She's not rich by any means, but she loves her job. And, to her, there's no better feeling than that. She's just praying Nat isn't as prone to controversy as she is.

Curie was placed in a research facility where she helped to test and study different diseases with a group of other doctors before being places in a hospital. She mainly cares for sick children but is reveled to be one of the best doctors as she doesn't need to sleep or take any breaks. She adores her job and never stops working on cures and medicine for her patients. When she heard about the synths being created at CIT, she asked her supervisors if she could swap bodies so she could better fit in with the rest of her coworkers, as well as be able to hold vials and syringes better. They agreed and got her a custom made body for her to subvert her subconscious into. Eventually, when he's older, Shaun will come into her clinic in hopes of having his cancer fully treated, but that'll be years from now when he's in his 70s.

Even though Strong isn't affected by the FEV in this timeline, he still holds that same barbaric and thuggish aura. He's not affiliated with any gangs, but he's no stranger to violence and lives in the part of town where shootings happen the most often. Despite his intimidating stature and hostile disposition, he still frequents the local libraries. More often than he'd care to admit. He loves old literature and has a bit of a soft spot for anyone who likes it too. He claims she's overexaggerating, but Daisy will usually sit and listen to him ramble for hours about the beauty and symbolism littered throughout Shakespeare's plays or Lovecraft's short stories.

Hancock is a well-known politician who is loved as much as he is hated. Ever since Piper outed him for his drug addiction and put into question his validity and dedication to his cause, he's been somewhat of a controversial figure in the political world. Despite it all, he has no ill feelings toward Piper or Publick Occurrences and is constantly hyping it up as a reliable news source. Although he owns quite a bit of cash, he's constantly pouring it into the slums of Boston. Some think this is just a publicity stunt to make up for his occasional violent outbursts (the drugs do a number on him since he's not a ghoul), he does it because he genuinely believes it's right for him to do. Besides, the people are friendlier there. Now his biggest concern is building up his reputation again so he can beat his brother when they run for mayor against one another. Him and his secretary, Fahrenheit, have a lot planned for the city and they'd like to see those ideas become reality as quickly as they can manage.

No one's really sure who Deacon is, and some are cautious of him for it. One thing that is certain about him is that he's a massive history buff, and is almost always in a museum of some kind. His favorite past time is striking up conversation with strangers who probably just want to be left alone while they browse the artifacts displayed, but he doesn't really care. Eventually, he happens to start a conversation with Nate and Nora in the Museum of Freedom and he quickly integrates himself into the couple lives. Him and Barbara like to show up spontaneously on their doorstep with a pack of beers in their hands and grins on their faces, but surely they don't mind.. even if they still have no idea what he does for a living.

X6-88 is another one who doesn't change much. He works as security for CIT along with Nick, and few other courser's, although none of them are as approachable as the detective seems to be. He's very strict about his job and carries it out very well, however, when Shaun eventually begins to attend the college, they sorta hit it off? Not really because either of them are particularly kind to one another, but more so because they like it when people are straight forward, intelligent, and blunt and they both just so happen to be that.

Dogmeat’s a stray that everyone seems to know. Officially, he’s Mama Murphy’s, but most everyone claims him. He appears whenever someone's in distress or wherever his owner's vision take him. He's a mysterious dog with strange motives.

Old Longfellow lives as a fisherman up in Maine. Nothing particularly changes with him, he's still got the same closed off personality that he'd always had. His wife got sick and died and few years back, but his daughter went and became and engineer in a similar area to DiMA. Longfellow thinks DiMA's a kook but his daughter thinks he's a scientific masterpiece and will often ask him questions about his creation or how his mind was built.

Gage grew up around gang violence and quickly learned to steal, lie, and hurt to get the things he wanted. He never really lived in a stable home and mostly just squatted or camped wherever he could. Despite living in poverty, whenever he and his friends managed to scrap together enough money together, they'd hitch a ride to Nuka World and spend the day there. He grew to have a soft spot for the amusement park as he got older, and took up a maintenance job for them (they don't do background checks.. or any skill checks for that matter, but Gage is a quick learner.)

MAJOR FACTIONS + SYNTHS

The synths operate in society along with the other robots of the fallout universe. But, unlike the Protectrons, they can actually hold conversations. Because of that, they normally take on your regular lower-class to lower-middle-class jobs. They don't tend to be rich at all in their lifetimes due to the stigma around treating them exactly like humans. A lot of those opportunities have been stripped away from them for those exact reason. Some of them still manage to find ways around it, but it's a lot harder than how it'd be if they were a regular human. For instance, synths can't start businesses on their own. Many argue that it's because they're just not meant to do anything on their own and that they were created to help humans, but no one can give an argument on how them doing their own thing would harm them either.

The Railroad is the main group that's actively against the stereotypes and discrimination faced by the synths. Although, they've received a lot of backlash for naming themselves after a former anti-slavery group (many don't think it's fair to compare 1800s racism to whether or not bots can work higher-paying jobs), they've still become a huge relief to many synths who are desperate to be treated the same as any other person would.

The Institute is just a college in the modern age. Despite them receiving some backlash from the public about whether or not the practice of creating human-like bots, arguing that it's too 'Frankenstein-like', the students and professors still continue to build and work to make more and more realistic, artificial creatures and beings. Mr. House helps to fund their research as he finds it useful and because he also went their for school.

The Minutemen don't exist. There's no need when you have the police force, the fire department, and properly operating Protectrons active in the community. Most of hose who were a part of this faction have taken up community-centered jobs like farming or social work.

The Brotherhood of Steel continue to exist as the US Military. They're more focused on defending the country than they are preserving technology and the only places you’ll see one is in military bases or along the coast.

MINOR FACTIONS

The Atom Cats (along with Sturges) are a group of young adults who work at the local Harley Davidson. Tuesdays and Thursdays they host poetry night and generally just open the place up as a garage for anyone interested in mechanics or just hanging out with a bunch of strangers.

Raiders and Gunners are just the Bloods and Crips of the modern world. They stick with their own groups and despise anyone from the opposite side of the tracks. Shoot outs and common between them and it's best to not be associated at all if you can help it.

The Children of Atom are a strange and niche group of zealots that migrated from somewhere in Virginia to spread their gospel. No one’s sure who they are or what they want, but they’re attracted to the pollution cities bring and generally advocate for the betterment of the earth.

Ever since DiMA's arrival, Acadia's national park has turned into a debate ground for different thoughts and philosophies. People from all over the world come to visit to talk and discover other points of views. There's even a Atomite Pastor that frequents the area and promotes the newly found religion with those who are willing to listen. A strange place for stranger people.

#fallout#fallout 4#fo4#rj maccready#maccready fo4#nick valentine#nick fo4#cait fo4#paladin danse#danse fo4#preston garvey#preston fo4#codsworth fo4#piper wright#piper fo4#curie fo4#strong fo4#john hancock#hancock fo4#deacon fo4#x6-88 fo4#dogmeat fo4#old longfellow#old longfellow fo4#porter gage#gage fo4#fo4 companions#modern au#fallout modern au#fallout 4 modern au

102 notes

·

View notes

Text

my husband was a carpenter [severance fanfic: Miss Cobel/Mark Scout]

(read on ao3)

The funny thing was that he didn’t even like Mrs. Selvig. Not really. She was nosy, grating, and always moved his bins no matter how many times he called her trying to explain, patiently, the difference between recycling and trash day. She was an old lady who half the time seemed like she was losing her mind, and he tried to give her some grace for it, really—but it didn’t change the fact that whenever he was near her Mark always felt awake.

Was that weird? Maybe that was weird. Maybe it was just something to do with the fact that they were the only two people living on that empty street in that blue line of delft houses, or the fact that she had never known Gemma—that was it, right? You meet the person you want to live the rest of your life with, she’s kind, and funny, and shares the same hobbies as you do, and before you know it you have the same friends. Mark had transitioned into Mark-and-Gemma without any second thoughts, without anything but a kind of encompassing wonder, like every day they were both alive was another day he could observe something incredible in the sheer fact of his wife’s existence. After she died, what was he supposed to do? Everyone who had known them both dragged their ghosts along with them. The breath that already laced itself through his throat with the subtle delicacy of mustard gas seemed impossible to draw. He didn’t want to forget Gemma, but he couldn’t bear it—the looks, the empty lulls where her voice should have been, the way he knew everyone was comparing him to before, to that better version of Mark who only drank in moderation, who had a promising job as a professor instead of being a suit in an unethical company, who knew how to smile. But he’d lost his light the day he lost Gemma and he didn’t want it back. This was his life to ruin. A miserable half-life cloaked in radioactive decay, sure. But the alternative wasn’t the better version of Mark. The alternative was Mark driving off a bridge, and how are you supposed to say that? When, exactly, is the best time to bring that up?

“Still waiting for that third bulb to revive itself?” Mrs. Selvig called from the hallway as Mark hurried to clear off his counter space.

“Oh, yeah,” he answered. “Keep forgetting to change that.”

She walked in, sat down on the other side of the countertop, smiled at him teasingly. “My, you smell nice. Were you on a date?”

“Sort of,” Mark explained, getting the carton of milk from the fridge that he only really kept around for visits like these, and pouring her a cup. Mrs. Selvig ran one of those health-food stores where people paid as much for the meditative experience and the idea of them being conscientious consumers as the actual food. So she used Mark as her guinea pig for new recipes. It was a small thing, but it felt a little bit like being needed, like he wasn’t just someone’s charity case. “My sister set me up with, like, her doula—” he went back over to the fridge to put away the milk, corrected himself, “or, midwife. Didn’t really feel like anything.”

He’d tried mostly for Devon’s sake. She was the only person he didn’t want to hurt, had never wanted to, but seeing her worry about him felt like he was falling down on the job of being the big brother. It had always been Devon who had the caring gene, but caring just hurt unless your patient actually listened to advice. Mark—although invariably incapable of listening to advice—had somewhere along the way learned how to go through the motions. Gingerly, he picked up one of the dark cookies that Mrs. Selvig had brought over. Still warm; crisp enough but with a perfect buttery texture. “Well, let’s see here. I’ll…” he bit down. Surprised—he’d never been a fan of chamomile. But, nodding his head in her direction, he admitted, “wow. This i… these are magic.”

She seemed charmed. “My late husband was a carpenter,” Mrs. Selvig proclaimed, in that rolling way she had when she was going to make some kind of completely off-the-wall point he’d have to pretend to understand. “And before he passed, he said he would start building us a house in the hereafter.” The look in her eyes had gone gentle and faraway, but there was an obsession underneath that gave him a momentary discomfort. He’d never been able to get into religion. Never really understood any system that required you stop asking questions in favor of belief. Mrs. Selvig had never tried to proselytize to him, so he was left in the uneasy place of feeling like he was doing her a disservice, like either he should agree with her or tell her straight out he thought she was comforting herself with a load of bullshit.

“And there would be a small guest apartment in the back,” Mrs. Selvig added with a mischievous smile, “in case I found a new man before I got there.”

“That’s… so sweet,” Mark said. He wasn’t sure there was a right way to respond to a story like that.

“Yes,” Mrs. Selvig agreed. “He even drew blueprints, which I keep in my purse.” She reached into the purse beside her, drew out from a zipped pocket a piece of paper, much-folded, the edges worn smooth, and with a kind of delicate ceremony, she unfolded the blueprint on his kitchen counter and looked at him expectantly.

Maybe it shouldn’t be a surprise that her husband had been as batty as she was.

“Uh, that’s very… detailed,” Mark said. “I suppose I should be thanking him every time I go to work.”

“What?” Mrs. Selvig asked, wide-eyed, and Mark felt like he’d made some misstep he didn’t know about.

He reminded her, “I mean, he must’ve made the blueprints? For the Lumon building?” She’d told him ages ago her husband had worked there; it was why she’d been able to get into Lumon housing after he died.

“Oh!” Mrs. Selvig laughed fakely. “Oh, of course! No, he was only a carpenter, not an architect—he’d never have made the blueprints for something like that! A corporate building—imagine!”

“Oh, yeah, I guess you’re right…” Mark said.

“No, he just made sure all the joists were at right angles,” Mrs. Selvig said. “But to think, his boot-print might still be there in the concrete floor, where you do all your important archival work. You might step into it and never even know… in fact, I think your feet might even be the same size…”

“Uh…” Mark said. He gave her a deadpan look. “Are you flirting with me, Mrs. Selvig?”

“Why, Mark! Whyever would you get that idea?”

“I don’t know. Maybe it’s just that comparing me with your dead husband’s foot size makes a man start to wonder.”

That startled a real laugh out of her. Less controlled, sharper and uglier than her social laugh. The corner of his mouth tilted up, vaguely proud.

“You have a dirty mind, Mark. Have a cookie.” She picked up another one, holding it between the tips of her fingers, and leaned a little closer over the counter, until the edge of the cookie brushed against his lips.

Her eyes were sharp and blue, like ice against a wound. “I’m sorry,” he murmured. “I don’t know what came over me…”

“Mark,” her voice had grown quiet and controlled, “take the cookie.”

He bit down. Crumbs falling onto the counter between them. This cookie was as good as the last; still magic. She held the baked good until the very last piece slipped between his lips, her fingers grazing his open mouth.

Then she leaned back, and Mark glanced back down at the blueprint, where a few buttery crumbs had dropped and left dotted stains on the old paper. “Oh, I’m so sorry, your blueprint…” He brushed them away.

“Nonsense,” Mrs. Selvig said. “It’s fine. A few cookie crumbs won’t hurt. And I have the whole thing memorized, anyway.”

Mark looked at that precisely-drawn house on the paper, all right angles from above, and the guest apartment behind the master bedroom. “Jack and Jill bathroom, cute.”

“It’s effective.”

“But it looks like he forgot the other door?” There was no exit in that room; not into the rest of the house or even onto the outside. It looked like whoever was unlucky enough to live there would have to traipse through the master bedroom anytime he wanted to leave.

“Nonsense,” Mrs. Selvig said. She pointed to a square box drawn in the corner of the guest apartment. “It’s built over the garage, so you can go in and out just like that, through the elevator.”

(on ao3)

1 note

·

View note

Text

<witty title here>

I’m in my feels this morning, pain is particularly bad this morning and I just... /sigh. Waiting for my pain meds to kick in and I realized one of the most terrifying things I learned as an adult is that almost everything around us is just made up bullshit. When I was a kid, we were all told, “Go to school, go to college, choose a career, graduate, get the job you want, work 40 years in a fulfilled life spending my last years playing a fucking guitar or something” But that story has no real truth to it anymore. I say anymore, I’m not sure it had truth to it in the 70′s for most people honestly. It’s just like this great lie we were sold when we were too young to even know to question it. One of the constant comments I read all the time are folks saying how much better off now than we’ve ever been as a species. Technology is flourishing and if you ignore the giant steaming pile of wailing malodorous corpses, Capitalism is the viagra of unabashed human progress. But I would honestly argue that this may be one of the worst times to be sentient because we have self awareness because I have emotions and feelings and I am acutely aware of the fact that I’m trapped in time and that one day I will die. I know all that but I have no idea why the fuck I’m here. What purpose, if any, does our existence bring. This conundrum is so deeply ingrained in us that people dress up in funny clothes every week and listen to an even funnier dressed man tell them a bat-shit fucking insane story so well crafted it’s able to push the wailing cries of existential dread down into the gut for a while. This will never be resolved in my lifetime or years. This might never be resolved. Our innate sense of self awareness coupled with the reality of our own demise might be the greatest unintentionally hilarious cosmic absurdity that we are all doomed to play out. And with that boiling cauldron of ontological excrement hanging around our necks and filling our nostrils day in and day out it amazes me how willing some people are to numb themselves to it. Like.. I get it, I understand constantly staring at this unknown abyss could fuck you up pretty good but I don’t know what it says about us that in the face of this existential nightmare that we not only continue to function but we actively castrate anyone who says this shit. I’m sure I’ll get comments or messages telling me how “edgy” or “immature” or “childish” I’m being by saying this out loud and maybe some folks can walk hand in hand with death on the precipice of nothingness but I’m reaching for the pill bottle just thinking about it. No wonder people aren’t willing to work minimum wage jobs getting harassed by some doe eyed dipshit. We do not have time for that. The clock is ticking and the last thing we should have to concern ourselves with is filling out a goddam spreadsheet, getting paid barely enough to afford food, having zero chance of upward mobility, being tacit perpetrators of a broken social order, having every one of our actions be unethical by fucking design and the list goes on. LIke... fuck me but can we just burn all this to the ground because I’d really like to meet that chasm of nothingness knowing that I at least made the pointlessness of our absurd existence a little bit better for the poor bastards coming behind me. .... holy shit that was unhinged.... well, have a happy new year, everyone.

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Substitute Lover (6)

word count: 2.5k

genre: fluff, angst hehe

pairing: myg x reader

summary: Finally meeting the college boy you’ve been eyeing on for months, everything goes wrong when you realise what you’re really getting yourself into.

a/n: this is part 6 !!! Thank you for the feedback from last chapter! The vote for updates was split so I updated on the weekends and weekdays! :> If you can, please please please leave me a feedback after reading this chapter. :> Thank you!!!

NEXT | PREVIOUS

"Joonie, you promised." You groan into your phone. You are pacing back and forth in your apartment as you talk to Namjoon who decided to do a raincheck on your plans today. You were supposed to buy a gift for your Mom as her birthday was near. If you can't be there physically, you at least wanted to send something.

"I know, Y/N." he sighed on the other line. "I was pulled in by Mijin saying Mrs. Lee needs me for rehearsals. No one else in our batch can play flute but me." you can hear in his voice that he wasn't fond of the circumstances too, so you decided to let it go. You can just go alone.

"I contacted Hoba, he can take you."

You found yourself roaming the mall alone for a good hour when you receive a message, asking where you are. Assuming that it was Hoseok's new number, you respond with your location and saved it under the name "Hobi" as you pocketed it to continue your stroll.

You turn to a corner and your mouth opened to gape like a fish. Yoongi is walking towards you with his hands in his pockets. He finally reaches you as you close your mouth.

"I'm assuming Joon didn't tell you that I was coming?" He mused. I shook my head mutely.

"Does Eujin know about this?" you asked. You didn't mean to impose. Yoongi nodded his head. Why was he lying about something as simple as this?

He doesn't know. He doesn't even know why he said yes to this at all. All he knows is that he intends to enjoy today. He's having too much on his plate. You shrugged and cleared your throat.

"I want to buy a shark charm." you said, not looking at him.

"Shark?" he repeated. You put your hands together and placed it above your head as if to act like fins. "Sharks. Jaws. Fish are friends, not food?" you mused.

This made him smile to himself. You really are a peculiar one. "That's my favourite animal to exist, I'm giving that to my mom as something to remember me by."

He nods in understanding. He then leads you to what you assumed were a jewelry store. You trail behind him quietly. This was the start of your friendship and you didn't want to jinx it by doing or saying anything stupid.

You two walk around the store quietly. Charms of different sizes and figures displayed in a glass case, sparkling in the lights that illuminated the whole store. You try to focus on looking for the charm you intend to buy, momentarily forgetting about Yoongi.

You hear a throat cleared beside you and you turn thinking it was Yoongi, rushing you to hurry and pick already. To your surprise, you were faced with a handsome, handsome young man. Confused, you moved to the side, thinking that you may have blocked his way.

"Anything I can help you with, ma'am?" the man asked politely. You then realised that he was a clerk at the store. You feel heat creep up your cheeks just as you failed to answer immediately. You were too busy being flustered to even open your mouth.

Yoongi was quickly beside you, making you recollect yourself.

"I-I'm looking for a shark charm." You said, and awkwardly doing the fin thing you did for Yoongi earlier. The man in front of you chuckled heartily, revealing a dimple on his cheek. You found yourself blushing again.

Yoongi clicked his tongue in annoyance and lifted his hands to bring your "fins" down. Once your hands are back to your sides, he spoke up.

"He knows what a shark is, Y/N. You don't have to do the hands." You nod, and subtly glance at the nametag of the man in front of you that read "Jeongguk".

"Follow me, sir." Jeongguk paused for a while. "Ma’am." he warmly smiled again.

Jeongguk showed you all types of charms and pendants available in the store and in the end, you bought a bracelet charm. It was beautiful.

"Thank you, Jeongguk. My mother would love this, I'm sure." You thanked him one last time. He bowed slightly.

Yoongi was itching to leave and you are honestly sorry to take up so much of his time. So you both head to the exit but before you reach the door, you hear a soft "wait" behind you.

Yoongi was the one to turn first, and then you did. It was Jeongguk. You assumed you have forgotten something but he handed you a piece of paper.

"I wasn't going to since it was unethical," he explained. "But I don't want to have met you and not shoot my shot."

Yoongi snatched the piece of paper from Jeongguk before you could get it. Was he fucking invisible? What was this guy's deal?

"What's your deal, man? Don't you see that we came in together?" Yoongi asked, trying to stay calm.

"I didn't think you would mind, sir." Jeongguk explains. Yoongi shot a brow at this.

"The ring on your finger." Jeongguk answers. "She doesn't have one."

You try and keep a straight face and act unaffected with the statement. Before you can even reply, Yoongi was dragging you out of the mall and into the parking space, not even bothering to stop. He was pissed beyond words. Why was everyone endeared by you? This was a mystery to him.

And you? Blushing furiously at everything that boy said. He scoffed beside you, while you are still oblivious to why he got angry. You assumed it was because you inconvenienced him. You are already thinking of ways to apologise but you were busy not tripping. He wasn't as tall as Namjoon but he was relatively taller than you and you had to jog in order to catch up to his pace as he continue to drag you by your cardigan sleeve.

He was mumbling angrily as he dragged you to his car. You stayed quiet beside him, he must've felt humiliated to be with you. Had you not been with him, he wouldn't be mad right now.

"Yoongi." you call out. His head snapped to your direction. You cleared your throat awkwardly, and fixed your glasses.

"I'm sorry," you start. This made Yoongi's eyebrows furrow in confusion. "I should've just waited for Namjoon to be free and not have you come with me." you spoke up.

"Stop." He replied. "I told you before and I'm telling you now. I wouldn't be here if I didn't want to."

You look up at him, you felt your entire emotions surge and you are fed up with everything Yoongi does and says. You sigh as you ran your hand through your hair.

"Yoongi, why are you here?” you asked. “Have you figured it out?” “Figured what out, Y/N?” He returned. Your mind flashed back to last week’s events.

You were on your way to Mr. Do, your professor’s office, when you heard a female voice that made you stop in your tracks. You start hiding at a corner while at the Business Administration building..

There you found Eujin and Mr. Do hugging tightly. You didn’t really know how to react. After all, it was just a hug. You would like to put a little faith into the love of Yoongi’s life. She would never do this to him, you thought. But when he attempted to kiss Eujin you were quick to react. With your small frame, you pushed the two away from each other. Your chest heaving with every breath that you took.

"Eujin. Mr. Do." You cleared your throat. This made them jump away from each other. Like a fire was lit and burned the two of them. "I-I will pretend to have not seen whatever this is" You start.

Mr. Do, as you addressed him to be, seemed to relax at your statement.. After all, he will not only lose his job but also his dignity once this gets out of the three of them.

"But" you continued. "This has to stop, please."

The way you begged confused the fuck out of Eujin. Why were you begging? Weren’t you supposed to be happy that you caught her and can finally be with Yoongi?

"Y-Yoongi. He loves you so much, Eujin." You faced Eujin who has no emotion in her face but shock. "Please don't hurt him, please." You continued to beg.

Unbeknownst to you, Hoseok followed you to the building for you have left your apartment keys on the chair you sat on. He watched the whole ordeal as you started to beg. He wanted to zoom into the picture and take you away. You were lowering yourself to beg for Yoongi? He was infuriated with whom? He no longer knows.

"Mr. Do, please know that if this continues, I will report to the Dean immediately." You threaten and with that, you grab Eujin's arm and drag her to the restroom nearby.

"Don't fucking touch me, Y/N." Eujin takes her arm back as soon as you both arrive at the restroom. She made sure no one was around when she turned to face you. You can see clear as day that she is terrified with what you saw. She didn't want to lose Yoongi.

"I-I won't tell." you promised as you fixed your glasses.

"Why not? Wouldn't that benefit you? You can finally have Yoongi." Her voice was shaky as she said this.

"I'm not selfish, Eujin. I want him to be happy." You smile. "So please, while you haven't done anything you'd regret yet, stop now. I can guarantee that I won't tell him." you urge.

She closed her eyes, ran her fingers through her hair and looked in the mirror. She was still shaken but better. Without saying a word, she turned and left.

You had no choice but to watch her figure leave.

“Nevermind. I can go home from here.” You fake a smile. You bowed your head and turned to leave. Yoongi has had enough of you leaving and grabbed your arm. The contact sending shivers down your spine. You were quick to remove his hand and something flashed in his eyes. It was gone before you could even decipher what it was. “I’ll take you home. You accept these offers from Hobi and Joon, why am I any different?” He was going to start dragging you but you spoke up again. “Yoongi. we're friends, right?" you asked, as you removed the paper bag of the charm from his hand.

"Of course, we are." He answered as if it was the most obvious thing in the world.

"Then don't act more than that. I asked you to give me a chance and you didn't." you face him tiredly. "I had to endure seeing you with Eujin for months and you didn't hear anything from me. The least you can do to is to not confuse me with all these halfass comments. I like you but I will never be a substitute lover."

With that, you turned to leave. Everything is crashing down on you. With the stress of having to hide what you saw, to your studies, and now with Yoongi confusing the fuck out of you. You just cannot catch a break.

Yoongi was too shocked to react, he wanted to follow you but what would he say to actually appease you? You were right, after all. Spending time with you honestly confused his feelings for Eujin. Hoseok and Namjoon knew this but didn't say anything. They took matters into their own hands and set you two up.

You sat at a bus stop as you rummage through your bag for your phone. Dialing Namjoon's number, he picked up after a few rings.

"Y/N?" He had a teasing tilt to his voice. "How was it?" As you expected, he wasn't in practice as it was quiet around him. You sigh into the receiver.

"W-What do you t-take me for, Namjoon?" You try to make your voice as stable as you can but it cracked in the end. The humiliation and exhaustion with the whole narrative is making your head spin.

"Did something happen, Y/N? What did Yoongi do?!" He grew alarmed as you cried. You heard shuffling as another voice spoke into the phone.

"Y/N? Are you alright? Where are you, I'll pick you up." Hoseok spoke.

"You were in this too?" You gritted your teeth. Anger and disappontment bubbled in your stomach, no matter how you tried to push it back down, trying to be rational.

"I am not a toy for your trio to play with." You finally spoke coldly. "I have feelings too. I'm not a charity case, Hoseok."

Hoseok winced at the lack of nickname and familiarity to your tone. He and Namjoon only wanted to make you happy, hence the setup of the date.

"Please, I'll pick you up." Hoseok sounds panicked already. "Y/N, love, tell me where you are." On his side, Namjoon watched shocked with how he addressed you. Hoseok was shocked too.

"Don't bother showing your face to me," You breathed. "I don't want anything to do with the three of you.” You were about to drop the call as a bus approached the station but you stopped as soon as Hoseok spoke again. “I saw you last week, Y/N.” You didn’t reply. You both knew what he was talking about. “It was none of your business. That was up to Eujin and Yoongi to fix—“ “Come on, Y/N! Do you hear yourself? She was cheating on him and you know it.” His voice was cold, you barely recognized it. “Even if Eujin did cheat on Yoongi, even if they break up,” You pause. “It still wouldn’t be me. Yoongi will never choose me.” “And how sure are you of that?” A voice spoke but it was not Hoseok. You glanced to your right and saw Yoongi who must’ve followed you. He was panting as his chest heaved up and down. He ran. The bus finally stopped in front of you. You gave him a final look. Yoongi’s eyes were begging you to not get in. But you did. ------------------------------------

NEXT | PREVIOUS

#myg x reader#myg x you#min yoongi x reader#min yoongi x you#yoongi x reader#yoongi x you#yoongi angst#yoongi fluff

58 notes

·

View notes

Text

Lie to Me

Guess who's back on their shit?

Another cancer fic for you because there's something very weird about me that stays drawn to the idea of secretly being sick

Anyways

Warnings: well... cancer

Pairings: none? yet.

Supervisory Special Agent Hotchner has a certain reputation around the office. The BAU’s ghost, walking around in his leather dress shoes and fancy suits without so much as a groan from the old, torn tile beneath his feet or the muffled swish of the material of his slacks. You never know he’s there until he wants you to and by then it’s always too late. By luck of his poor hearing or his natural affinity for silence, nothing admitted in his silent presence ever graces his lips for a repeat. The secrets all die with him. He’s as loyal as a dog -- in ways that lead to natural gravitation. The reason why Penelope Garcia beams at him every time their paths cross, why she so eagerly rushes to match his pace. To just walk beside him and talk his ear off even though she knows her answers will come in the form of soft hums and furrowed brows. In other ways, it’s killed him. Left him to live the life of a lame dog, dragging his dying body away from them. Hoping to spare them the agony of his death.

Some things that people say about SSA Hotchner are true. He really does move like a ghost and it’s a thing of great mystery and annoyance. It’s cost Emily Prentiss numerous mugs but perhaps the flash of his smug crooked grin makes that worth the shattered cup at their feet (she wouldn’t agree with that statement). He’s made Derek Morgan nearly jump out of his skin, whirling around to attack whatever snuck up on him only to find Hotch frowning back at him. If asked, David Rossi will blame Hotch for 79% of the grey hairs on his head because he hadn’t even begun to go grey until he met Hotch.

He’s really not as scary as people make him out to be.

Penelope Garcia wishes everyone knew that. She wishes cadets looked at Hotch the way that they look at Derek and Spencer. As awe-inspiring giants, they crane their necks to look up to. Instead, they lower their eyes away from him. Whispering to one another about the rumors and the things that they have been told. They regard him as a lesson -- someone to measure their existence against. To know when to get out of the job. To know when they can no longer turn back.

He’d saved her when it seemed no one else in the world really looked at her. She’d watched him take her homemade pink stationary in his hands, held it delicately as he looked over what menial ideas she could think of. He’d looked at her kindly, not at all like the snobby FBI brat she assumed him to be, and shaken her hand, “Thank you, Miss Garcia.” For the months following her career change, he’d been too kind. Brought her lunch to her desk because she was too anxious to leave her office. Gave her advice about where to park and how to miss Strauss in the hallways.

As important as his approval is to her, his well-being is more important. So, no, she doesn’t turn away when she sees him on Saturday in the emergency room. He’s sleeping off a cocktail they’d given him, turns out it’s rather hard to place a catheter near the heart when it’s beating erratically. His anxiety had nearly caused him to be sick and so he’d agreed, finally, to let them give him something to calm him down. Which is where Garcia finds him, left arm cradled to his chest, too long limbs hanging off the stretcher, and breathing slow and steady through the oxygen canal under his nose. A precaution, that’s all, given the sedatives they’d doped him up with.

“Sir?”

The fingers in his left-hand twitch, flexing towards his palm and he grunts softly at the pain that the movement causes. Slowly, breathing hitching and his eyes fluttering open, he wakes up. He’d heard, vacantly, the hesitant “sir” from the end of the bed but he assumed it was a nurse. As his eyes rise up to search the room he’s surprised, entirely so that he thinks he’s hallucinating, to find Penelope.

“Are you okay?”

He’s still piecing together the last few hours but nods. Cracking open his dry lips he swallows thickly, trying to work his voice around the tightness in his throat. Dehydrated and still disoriented he reaches for the cup of water left for him but at the current angle that he’s laying at, he can’t get it. He clears his throat, sniffling, “can you, ugh--” He’s still looking at the cup, dazed to the point he can’t think of the words he means to say. Tired eyes look back at her, pleading silently that she understands.

Penelope nods, moving forward instinctively. She doesn’t look at him, at his dark blood dried to his arm. His hospital gown stopping just at the clear protective barrier between her and the port placed on the inside of his arm. “Here,” she whispers. She needs to be closer so he doesn’t have to stretch but can’t bring herself to be close. Not within his reach. Not so close that she can see the dark rings of sleepless nights carved under his eyes. Far enough away that the tremble in his hand is easily overlooked. So that he doesn’t seem as weak and frail as his voice sounds.

He sips the water, knows from too many mistakes not to drink too much just yet. “Why are you here?” He nearly sounds like himself, dark brows furrowed and voice taken its steady, deep rhythm back.

She looks over her shoulder, past the curtain pulled around them for the sake of privacy. “I, uhm, volunteer for a support group that meets every Saturday here at the hospital.” She points to the front desk, to a woman with curly hair pulled back in two ponytails. “I came downstairs to say hi to Mac and I saw you and I just…” Suddenly, realizes how she shouldn’t be here. That if he wanted comfort he’d have told them, or someone.

Wait. Stop.

That doesn’t matter. Hotch doesn’t know what’s good for him. Everyone knows that. So she made the right decision to come over here.

“You’re not driving yourself home, right?”

In her silent contemplation, he’d began to fall asleep again. The cup in his hand dangerously tipped and eyes held open by slow, deepening blinks.

“Hotch?” She touches his hand, flinching away at just how cold his skin is.

He cracks his eyes back open, cracks of soft brown iris finding her slowly. He hums, mouth cracked open.

“Will you let me take you home?”

Home. He hums again, vaguely aware of her warm hand coming to rest over his. Moving his stiff fingers away from the cup, taking it from him so he doesn’t spill it over himself.

It’s meticulous work, keeping him awake. Even harder making sure he gets dressed but once he’s sitting up he’s much more alert, grumpy now for being duped into asking her for help. She’d offered it but that means nothing to him. He’s no less thrilled to find his brain too foggy and arm too weak to work his arm through his sweater. She still smiles when his head pops through, hair a crazy mess on his head.

She packs him carefully into her car, a boxy little thing he’d frowned at when she bought it. He’d been the reason behind Morgan and Reid both coming to her office with statistics and fear about the safety of it but she’d loved it. He’s a worrier, prone to stewing and her car had taken up a lot of his energy for the first year she owned it. Now he’s being packed into the green monstrosity, senses assaulted by incense. Everything’s sparkly and he ends up sitting with a teddy bear in his lap, a troll in his hand. He’d taken their rightful place as her passenger.

His legs do not fit no matter how far back he moves his seat back and Penelope feels awful that he looks so uncomfortable but also finds it to be humorous. His knees to his ears, dark scary Agent Hotchner holding a stuffed bear to his chest, head resting against the window. It’s sweet.

It’s fairly easy to figure what his thought process today when she pulls up to his house and no one’s home. Jack’s camping, she learns. He’s dozed off again, prone and more willing to whisper half-truths. Will be away for the whole weekend until Tuesday morning. Jessica is getting her nails and hair done, he’d made the appointment just to make sure she really did it. The haircut should have ended just in time that he could call her and ask if she’d pick him up from the hospital. Where he thought he would have already artfully hidden the PICC line under his sweater and played the affair off as a routine sort of deal. A check-up.

“Sir…” she’s standing now, awkwardly, in his living room. The curtains are drawn back the way he likes, closing off the sun. He’s tucked under his heating blanket, trying to remain awake for the sake of the fact that it’s rude to fall asleep while entertaining guests. Yet, failing miserably. “Sir, I was just wondering… Is everything okay?”

“I’m--” the truth nearly slips right out. He clears his throat, managing to sit up just enough to catch her eyes. “Don’t worry about me, Garcia. Jessica will be around in an hour.” He holds his left hand closed, trying to stop his cramped fingers from twitching. “Dave and Emily are coming by for dinner. I’ll be okay.”

It’s completely unethical.

It’s so unprofessional.

But she can’t help herself.

Her eyes prick with tears when Emily shakes her head in the kitchenette, the sound of Hotch’s wet coughs breaking through his closed office door. “He needs to get that checked out,” she sighs, hiding her bleeding worry with annoyance. “Sounds awful.” And Penelope stands there with Hotch’s secret tongue-tied.

He’s getting worse and fast.

She gets a call from Derek, seething anger laced into his words. “He fucking-- He fucking just-- .” She knows it’s really just fear. Can hear him walking, his rapid pacing as he tries to outwalk his expanse of emotions. “He -- He shouldn’t be in the field. I mean, it’s like he didn’t even see it coming. He was just…” She remains steady. Wipes the tears that slip past her eyelashes with the back of her hand. Derek cries, on the ground with his knees to his chest, and he tells her what happened. How Hotch was paying attention to him and if he hadn’t been then maybe…

She greets them at the elevator, feels her smile attempt to waver when Hotch’s tired eyes raise from the ground. The bruise along his cheek a deep agonizing yellow, the wound on his temple still weeping angrily through the bandage. He can’t fly until his concussion is healed, longer if his tinnitus doesn’t get better. “It’ll be fun having you home,” she assures him, giving his fingers an extra squeeze.

Luck, it seems, has never seemed to favor Aaron Hotchner’s particular brand of bold.

Working at the District Attorney’s had been a morally fulfilling job. In theory, he could rest assured, each night, that he was doing what he could to help people. He was putting the real bad guys behind the bars. Even as his dreams filled with the images of the victims who had to wait for months, and even years, to get their proper justice. In reality, he slept poorly and rarely. Unable to properly maintain his workload without impossibly long hours. With time he found his work to be unfulfilling. He was doing nothing to stop crime from happening and sinking further into the realization that was failing more people than he could ever begin to help.

In court, he was ruthless. Haley didn’t like the man he became in the courtroom. Ruthless and harsh, he appeared evil and terrifying with his hawk-like eyes and infallible ability to pinpoint weaknesses in his opposers. Around the office, they nicknamed his alter-ego “Hot-head Hotchner” because the Aaron that gets flushed ordering lunch couldn’t possibly be the same man who made a man wet himself on the stand. Haley couldn’t agree more.

Hot-head Hotchner got him offered a job in corporate law, several firms were throwing big numbers at him to encourage that lasered focus to be on their side. Lest they find themselves opposing it. Morally, he could never go into corporate law but the offer to spend hours bending law into something pliable and poking holes in judicial wordings was compelling. It would be complex, rewarding work with a big pay-out. Better than the shitty salary he made at the D.A.’s office. Before he could make the compromise he met David Rossi and he never got his chance to bend the law to his will, he held his moral ground and instead changed career paths.

It was bold leaving what he knew he was good at for something new entirely.

A costly decision.

He never got to fulfill his secret desire to mold the law but bending the truth wasn’t a far cry from the same thing. Lying has never been something he felt comfortable with and that had no exceptions. He hadn’t wanted to tell the team Emily had died but that had far less to do with his morals and so much more to do with a picture much bigger than himself. The hell he knew that would rain down upon them in the weeks to come. The inability of the team to cope. Intuitively something holding them back and what they could only assume was a stage of grief.

To Emily Prentiss, he has never lied. Stretched versions of the truth he maintains to not be the same thing as a lie. If they count then his answer would be different but the eye of the beholder adds context. And as the holder of this context, he resolutes the power to declare them very different.

“New girlfriend?”

He’s breathing through a bought of nausea attempting to take him off his feet. The cold countertop biting into the skin of his wrist, his palm pressed flat to the surface so that he doesn’t grip the edge. So that his pale bloodless knuckles holding onto dear life do not betray the severity of which he fears he might get sick or pass out.

His phone is on the counter, turned upside down so that he doesn’t have to see the screen light up with every new text that comes through. The high-pitched “ding” of each new message is lost to the tinnitus he’s been succumbing to now for the better part of the week. No amount of coffee or Tylenol has helped.

Raising his gaze makes the pounding in his head worse but he has to meet Emily’s questioning gaze. They’ve started to notice his “off” behavior. His inability to stand for long amounts of time without physical drain. His decision to stay home on the last several cases, working here with Garcia rather than joining them in the field. The way he relies on Morgan’s lead more than he used to, falling silent and allowing the other man to make decisions. He suspects they just assume he’s looking into retiring or that he’s struggling to kick his “chest cold”, he doesn’t bother correcting them.

“No,” he manages, swallowing around the heaviness of his tongue. The way his mouth seems full of salival added pangs to his stomach as he knows he’s going to be sick. “It’s Jessica.” She’s angry with him and for good reason, though he doesn’t offer an explanation as to why.

Emily hums, raising her eyebrows and shaking her head. “What’d you did you do to piss her off?” In other circumstances, he might assume she’s attempting to pry. She’s just here for another cup of coffee, offering him a way to release some of his stress. No hard feelings if he suggests she fuck off and willing to lend an ear if he wants to talk. She’s not holding her breath but she hopes he comes undone. That he admits to some awful conspiracy and that this whole time they’ve been in some twisted social experiment to see how unified they actually are. That he isn��t as sick as he looks. That he’s just in a low spot and in a month he’ll be putting the weight back on and Derek will be telling them all about training for another marathon. How Reid could do more pushups than Hotch.

“I’m sorry,” Hotch whispers. He tries to step away from the counter. Feels the temperature in the room drops several degrees, his skin broken out in goosebumps. “I think to sit down,” he says frantically, knows now he needs to sit before he passes out.

Emily grabs his arm, tries to help him up. To get him to the chair that’s right there, so close.

“Hotch?” Derek jogs into the kitchen, he’d seen from afar and come running. “Emily, what’s wrong?”

Emily helps him to the ground, hand holding the back of his neck as his body starts sinking faster, beyond his control. She sits down on the ground beside him, eyes scanning across his body to find a feasible answer. Below her, Hotch’s breathing has gone rapid and shallow. His eyes rolled back into his head, neck-craning as he unconsciously fights to get air into his lungs. “I don’t know,” she says. “I don’t know. He just-- He was just--” Hotch wheezes, an awful sound. He chokes, blood coming to paint his lips. To coat his teeth.

“Hotch?” Derek moves to his side, picking up Hotch’s shoulder to move him onto his side. “Hotch, answer me!”

His only reply is a wet gurgle, a blood-coated wheeze.

#tw cancer#criminal minds#aaron hotchner#penelope garcia#emily prentiss#derek morgan#criminal minds fanfiction

39 notes

·

View notes

Text

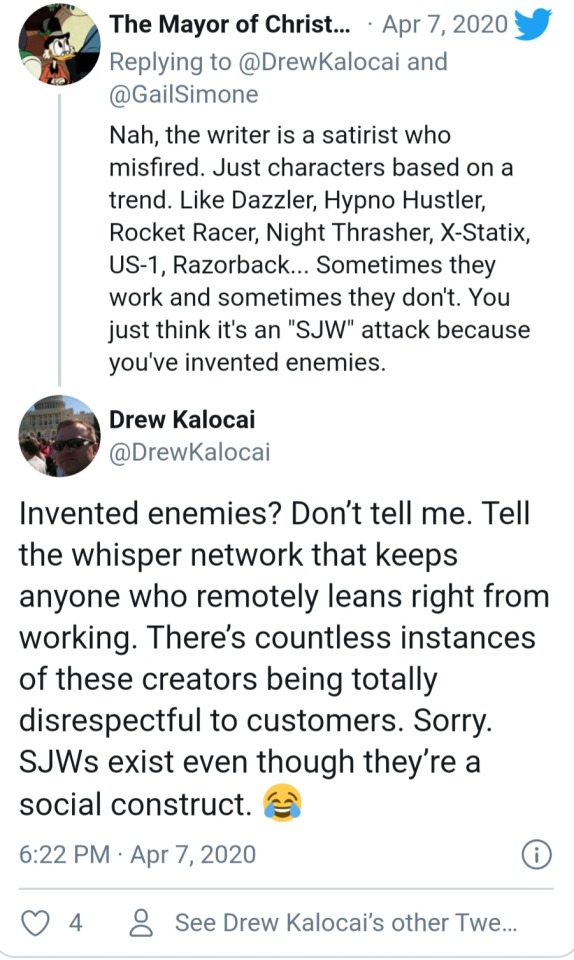

Many of the women promoting the “cancellation” of men in comics, and demanding they post the recent empty promise known as #ComicsPledge, are in fact hypocrites. In this article, I’m going to present evidence of lies, collusion, rumor spreading, and, in my opinion, defamation and contract interference.

I personally know that they’ve colluded for YEARS to take down men. Specifically those with conservative politics and philosophies. This is an ongoing, coordinated effort. How do I know this?

Because I obtained access to their PRIVATE FACEBOOK GROUP.

This is Part 1 of the #Hypocralypse leaks

There is simply too much to put in one leak, so I will make the following three points for now.

1. The so-called Comic Book Whisper Network, which has been dismissed as conspiracy since 2016, is real, and I have hundreds of screenshots to prove it.

2. The Whisper Network has been targeting men and trying to destroy their careers, and use their connections in the comic book media to do so.

3. Whisper Network members have acted unprofessionally and unethically at best. At worst, they have engaged in what I believe could be illegal behavior.

MY STORY

I first heard about the Whisper Network back in mid-2016 from folks I knew at Image, DC, Marvel, and later, Valiant. Depending on who I chatted with, sometimes the group was called ‘The Women’s Network’, other times ‘The Whisper Network’, occasionally ‘The Whisper Campaign’, and eventually there were more conspiratorial names used mockingly (a friend called them a gender-swapped 4Chan, which became ‘FemChan’ to some insiders).

Regardless of the name, it was all the same group.

The same five or six names kept popping up in conversation over and again. As time ticked on, I noticed a trend on Social Media: half a decade of rumors, false allegations, cancellation attempts , and they almost always traced back to these same five or six people. The goal of this Whisper Network, according to industry folks, was simple: choose a target, smear them until they lose their reputation, their income, and are ultimately blacklisted – opening up job opportunities for the same people who started these smear campaigns in the first place.

Behind the scenes these “cancellations” are painted as morally or politically motivated, but in the end it’s all financial. As time passed, the group in question seemed more and more like a reality. I saw their influence. I saw things I knew to be verifiably untrue go viral online, appearing in what I thought were legit news sources. I felt angry and helpless seeing innocent people getting attacked, but did not know what to do.

A few years passed and by 2018 almost everyone I interacted with in the industry seemed to know about the Network, from top level editors right down to the letterers. It was an open secret, but no one was willing to speak up for fear of being targeted themselves. They knew the consequences.

And after all, this was a secret network. Without proof, there was no point in going public because members would just deny its existence, and use their media connections to smear anyone who challenged them.

THEN THINGS GOT INTERESTING

December 16, 2018, Whisper Network member Gail Simone, who joined the Network 6 years ago (4 years before the following tweet was posted), mocks “doofuses” who speculate that a “whisper campaign” exists.

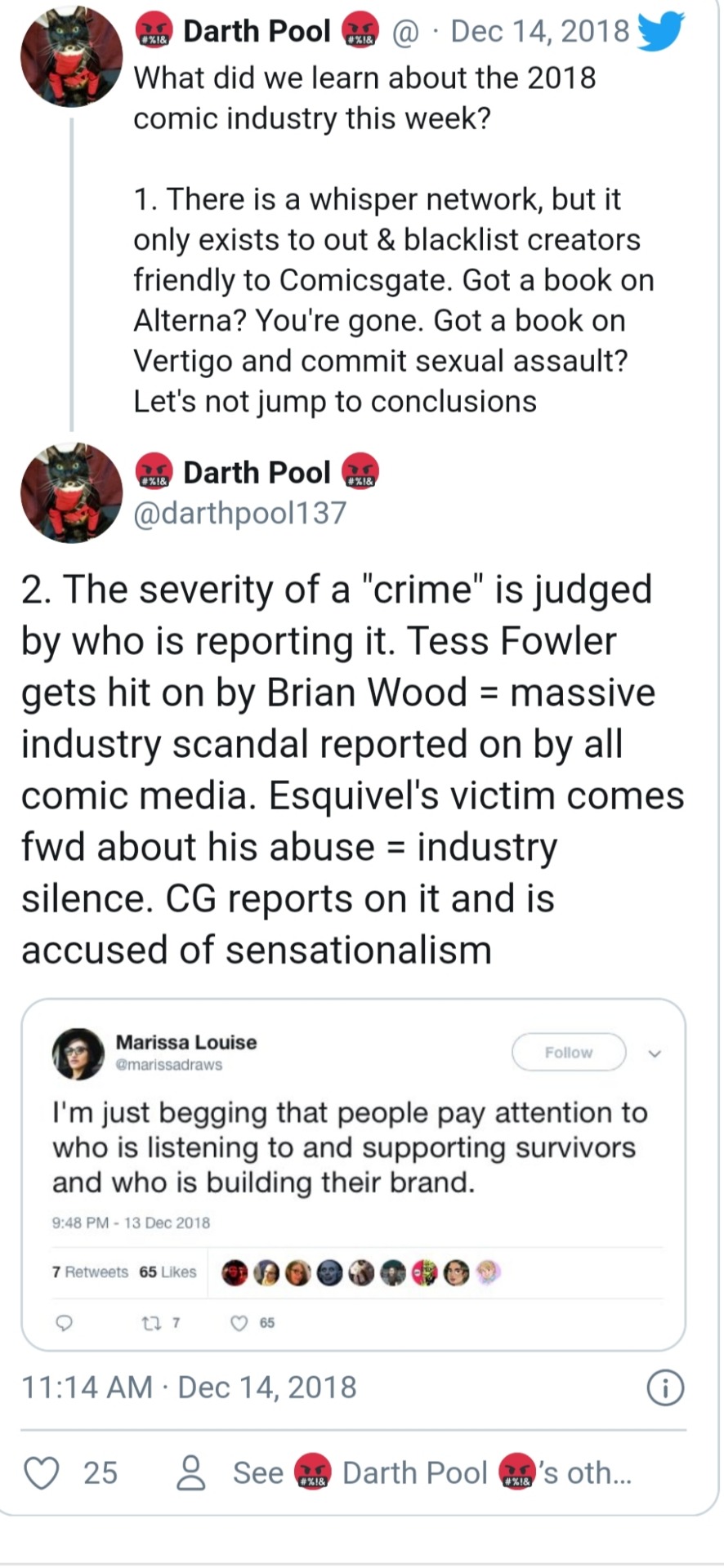

At this point in late 2018, I was still skeptical of the Whisper Network’s existence. I’d heard many stories of individuals spreading rumors and lies, and plenty of malicious behavior was going on behind closed doors. Though I wasn’t ready to believe it was a coordinated effort, or collusion was involved. Then, certain people began openly mentioning the Whisper Network and my attitude changed.

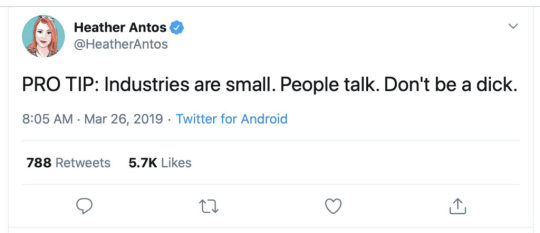

March 26, 2019, Heather Antos, a member herself, did not outright mention the Whisper Network or her involvement, but she made what some took as a veiled threat to those who got on her bad side.

Heather “milkshake girl” Antos’ colorful backstory at Marvel, and later at Valiant, is notorious in the comic industry. A conversation about office rumor-spreading and bullying is never complete without someone bringing up a juicy Antos anecdote. Everyone has one.

Up until then, I still hadn’t seen ACTUAL PROOF of a larger scheme. But then, something changed in 2020.

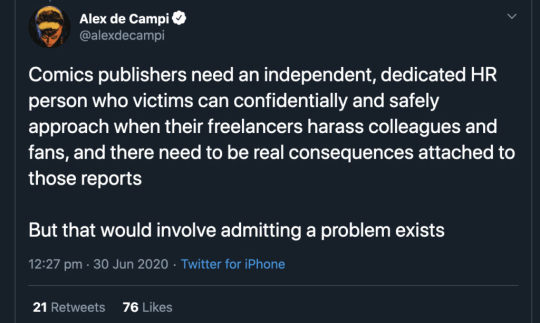

January 8, 2020, Alex de Campi, who I would discover is one of the most active Whisper Network members, openly admits there is a Network. I have no idea if this was a slip or a brazen attempt to show off her power and influence, but this appeared.

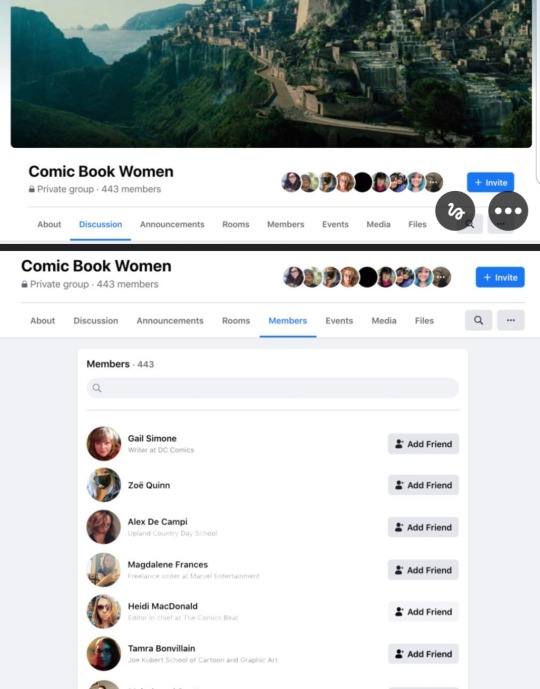

Eventually, everything I had heard and read was confirmed beyond any shadow of a doubt after I gained access to their private Facebook group.

I WAS INSIDE THE WHISPER NETWORK!

This is the place where the Whispher Network has been colluding for years. And although their activity is not confined to just this site, from what I can tell, this was where they first met, and started their coordinated campaigns.

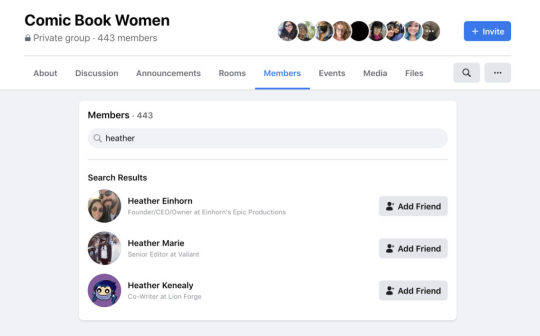

Members of the Secret Group called “Comic Book Women”

At present time, there are 440+ members of the secret Facebook group, called COMIC BOOK WOMEN. From what I can tell, a few are regular users, though many of them have never posted.

https://www.facebook.com/groups/comicbookwomen/

*unless you are a member, this will not show up in a search

Secret Facebook groups offer the same level of privacy as closed groups, but operate under a cloak of invisibility. No one can search for secret groups or even request to join them. The only way to get in one is to know someone who can invite you. Everything shared in a secret group is visible only to its members.

This secret group includes a list of members whose actions and connections speak for themselves. Members such as:

Zoe Quinn

Gail Simone

Alex de Campi

Heather Antos (aka Heather Marie)

Mags Visaggio (aka Magdalene Francis)

Mairghread Scott

And several key members of the group are women who work in the comics media and can be used to run damage control, including women like Heidi MacDonald of Comics Beat. They have contacts outside of the secret network as well, with some male allies in both comics and the media.

Just the fact that all of these folks were secretly linked in a private network came as a shock to me, considering their reputations and the accusations that they’ve made. Immediately I began to connect the dots…

They’ve denied for YEARS that they coordinate their actions in private. And yet they always coincidentally appear on Twitter, retweeting and amplifying each other’s accusations, signal boosting one another, and helping them gain traction. And their allies in media – Bleeding Cool and CBR specifically – will turn those same tweets into stories almost instantly & with no fact-checking or verification, sometimes within the hour.

I’m going to start explaining who the key actors are, and, from my perspective, how they coordinate these attacks.

KEY ACTORS

There are too many people to focus on at once, so I will have to break this into several posts, but I will start with one of the clear group leaders IMO.

Alex de Campi is well connected, despite never being part of the Big Two (since, from what I’ve been told management is well aware of her bullying, harassment, rumor-spreading and unethical behavior that goes back years, and depending on who you talk to she’s almost as notorious as Antos or Tess Fowler). She just wrapped up a graphic novel campaign on Kickstarter with David Bowie’s son, the Hollywood film director Duncan Jones. It grossed over $366K

All the while she makes baseless accusations while demanding transparency from everyone else.

Now, I’ll take you into their private network.

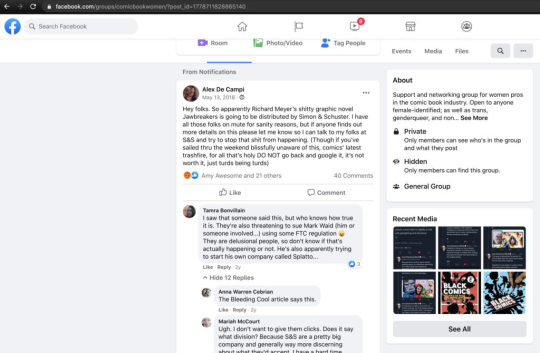

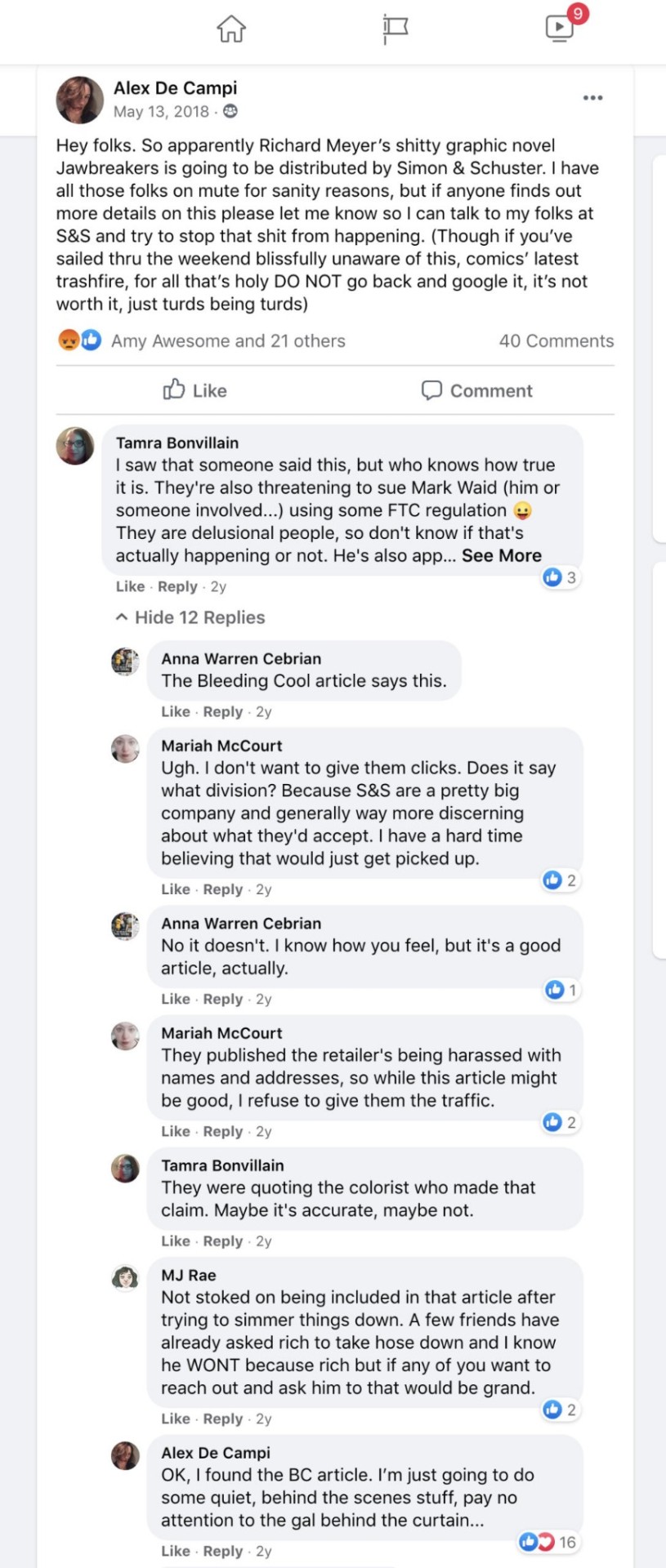

Two years ago, on May 13, 2018, De Campi launched a private campaign to target an independent creator, claiming she was using her connections to have Simon & Schuster cancel their book.

In addition to contacting the publisher, others in the Whisper Network coordinated their efforts to contact media outlets to have the narrative changed, according to the posts in this thread. Again, in my opinion, this could end up as a defamation or tortious interference case, and has many implications regarding media bias as well.

The following month, on June 23, 2018, de Campi posted private text messages between herself and writer Max Bemis in what appeared to be an attempt to damage his career. Despite Bemis being mentally ill (diagnosed with bipolar disorder in 2014), de Campi still posted the private messages with malicious intent IMO. According to US and UK law this is an actionable offense: posting private texts without both parties consenting.

430 notes

·

View notes

Text

So Lily ONCE AGAIN Responded

So basically she thinks i’m a Bible-Thumper. And she also acts like I only care about the rich people.

“Ironically, Aliana slaughters a bunch of security guards just doing their job in that same chapter but nobody mentions it. They only care about the rich people.”

Uh...evidently she didn’t bother to read my “So Lily Responded Yet AGAIN” post where I said...and I’m quoting directly here...

“Also, I know someone will bring up “But what about Aliana killing Rey’s parents”? Yeah that was murder too, she killed them in a fit of rage and they were unarmed. They may have been assholes but it was still murder. I didn’t want to, at first, bring it up because part of me felt “well she was kinda in a really bad mood and she got triggered by what they said” and I almost felt bad for Aliana...but reconsidering it...yeah. That was wrong too. It’s wrong to kill unarmed people. Wrong to kill people who can’t fight back. THAT’S murder and THAT’S wrong. Then there was the whole “when she went to get the CodeMaster” thing. She killed a lot of security guards. I was SORTA willing to overlook that because those guys WERE kinda armed...” Yeah, I kinda addressed the larger “she’s a murderer” thing not just in relation to those rich jerks. But you know what? She doesn’t think the criticism of Aliana is fair because as a Sith, her character’s SUPPOSED to have a darker morality. Okay...fine. Except Rey also casually murders a guard for accosting a refugee. Forgot that. She literally force-snaps his neck.

Okay, you know what...I’ve changed my mind. Aliana making those stormtroopers before doing the mass suicide, and Rey doing that neck snap of the guard outta nowhere for accosting a refugee, that kinda does seem like murder. It’s gross. You can’t just kill people for being kinda dickish.

And yeah, this is the full scene: “Rey glanced over and saw a Coruscant security guard accosting a Twi’lek refugee and scoffed. “Really? Because it seems like they have time to stick guns in everyone’s faces.”“When you’re wealthy enough, you can put almost anyone in your pocket,” Leia said with a downcast expression. “Official security teams make the best crime muscle.” “Oh yeah?” Rey said, almostly tauntingly. She reached her hand out and twisted her wrist. The guard’s head snapped violently to the side and he fell twitching to the ground. The Twi’lek glanced around in surprise, before getting up and sprinting away as fast as she could. “Hmm… seems like they need work.”“Rey!” Amilyn exclaimed incredulously. “He was accosting a refugee. What, was I supposed to just do nothing?!” Rey yelled.”

Uh, yeah, you can’t just kill a cop on the street if they’re asking someone to get out of their car so they can search their pockets. You can’t just kill a security guard in a store or mall because they wanted someone to come with them to check to see if they stole something. Yeah he’s an armed guard but the way she did it, this does basically make it murder.

And that “REY” from Amilyn is literally the ONLY criticism Rey gets. Guess what the next lines are? From LEIA of all people? ““I was more expecting you to go torture him a bit until his fellow guards laid down supressing fire allowing him to get away,” Leia said with a shrug. “You seem so fond of that tactic lately.”

So no objections whatsoever. I guess the SUGGESTION is supposed to be “All these guards on Coruscant are corrupt because the system is so unwieldy and unreliable”. Yeah, except there’s no proof that guard was corrupt or anything, he was just being kinda dickish and she casually kills him.

Our HEROINES, ladies and gentlemen. Our HEROINES. I think I’ve made my point. The main protagonists that we’re supposed to root for in her story are just WAY too comfortable with casually killing people and the story doesn’t really treat it as a bad thing save with maybe a few lines like “Rey!” or “I’m glad you’re on our side” or “Okay, this is a new side of you that I’m not sure I like,” Yeah, cuz that’s REALLY calling her out there. Fight the good fight, Poe.

I’ve said my piece. I just think it’s unpleasant and unethical behavior and frankly uncreative. Killing is the lowest common denominator. It’s the easy way out. And someone with Force powers should be smarter and more creative in how they handle problems. And so should Lily.

Can’t wait for another long post where she personally insults me, calls me a “fucking idiot” again and yells at me for being a Bible thumper or calls my morality “childish”. I find it pretty astounding that she says I’M the one having a break down when she’s the one who immediately went to multiple personal attacks, straw-manning my argument several times, and made more posts complaining about me than I did complaining about her STORY. Cuz that’s the thing. My critique was of her story and the character, not really Lily herself. But pretty much Lily’s ENTIRE bunch of criticism is mostly about ME being stupid and wrony and yadda yadda, that comes FIRST, defending Aliana’s behavior is second, and she only focused on the “Why do you care she killed rich assholes” thing, not the whole “Wow, she is WAAAAAY too comfortable with casual murder and killing people” thing that was my main point.

Also, you know what else bothers me? I left another review on her story about a week or so ago, I tried to overlook that casual murder thing to bring up a critique about the story that I thought was fair...that there was no real drama left, no threat left. Because think about it.