#two idiots falling in love during the Covid crisis

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Wanna Be My Pandemic Buddy?

By: TalktomeinClexa

Rating: Explicit

Warnings: Mentions of Covid

Status: Complete (19/19)

Summary: When Clarke, a graphic designer stuck at home during the lockdown hears about the Dutch Institute for Public Health’s official guidance to find someone to “share physical contact with” to limit the risks, she realizes that this might be her chance to get Lexa, her beautiful neighbor, into her bed. They start sleeping together and the chemistry is amazing, but will they manage to get over their emotional constipation before the pandemic ends?

***

Day 1: Agreement

Adjusting her mask for the nth time, Clarke took a deep breath to steel her nerves and resolutely knocked on the door of apartment 4B, across the hall from hers.

Luckily for her, the stupid cotton rectangle covering half of her face hid her instinctive smile when the door opened. Even though she hadn’t been out in days and wore sweatpants and a comfortable T-shirt, her neighbor was as gorgeous as always. And the best part was, in her hurry to answer the knock, Lexa hadn’t bothered to put on a mask, leaving Clarke free to admire the pouty lips she had been dreaming of kissing more and more recently.

“Clarke, hi. Is everything all right? Do you need something?”

“Hi, Lexa. How are you?”

A perfectly plucked eyebrow rose at the tentative small talk. Ever since the number of Covid-19 cases exploded, the government had put in place a series of strict measures to contain the pandemic. Closed borders, masks at all times, social distancing, restaurants and gathering places closed for the time being… Telecommuting was the new norm, and companies developed new tools every day to facilitate digital communication.

As a result, the news outlets reported fewer and fewer new cases every day. But with social quasi-nonexistent interactions, people felt lonelier than ever. Knocking on your neighbor’s door to chitchat was highly discouraged, and Lexa hadn’t expected any visitor.

Still, she was nice enough not to close her door in Clarke’s face, and, encouraged by her curiosity, Clarke carried on. “Have you watched or read the news recently?”

“Not really, no. All they talk about is the pandemic; it’s depressing. Why? Did I miss something?”

“Well, the Dutch Institute for Public Health released an official guidance a few days ago that might pique your interest. With the current danger we face every time we meet someone, they recommend single people find a person to have regular contact with. That way, we can enjoy physical contact while limiting the risks of spreading the virus.”

To her credit, Lexa didn’t outright laugh or slam the door in Clarke’s face, and that counted as a small victory. Instead, she looked at her with curiosity and a glint of something mischievous in her viridian eyes. “Just to be clear, we’re talking about sex, right?”

“Yes. Sex.” Clarke nodded, proud of herself for not blushing too hard or stuttering. “Or you know, cuddles are allowed too. Physical contact in general.”

“Hmm. And you want me to be your ‘cuddle’ buddy? Why me?”

Keep reading

#clexa#clexa fic#wanna be my pandemic buddy#PWP#I finally reedited this one#two idiots falling in love during the Covid crisis

43 notes

·

View notes

Text

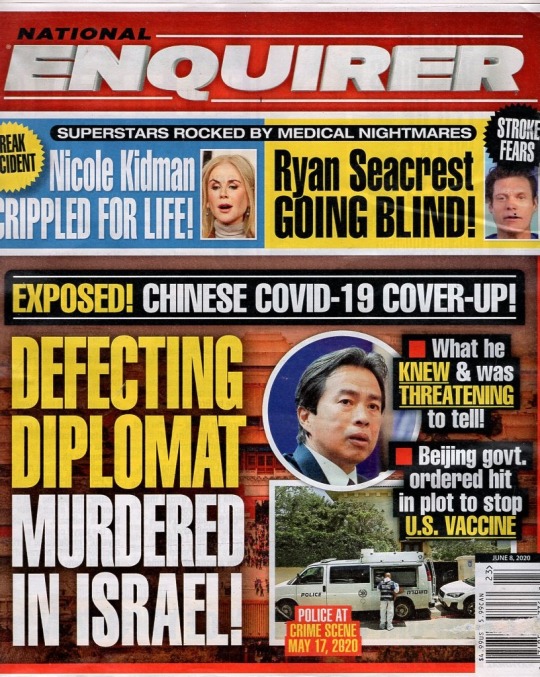

National Enquirer, June 8

Cover: Chinese COVID-19 Cover-up -- defecting diplomat murdered in Israel

Page 2: Former Jenny Craig weight-loss spokesperson Valerie Bertinelli is packing on the pounds again and said she doesn’t care anymore

Page 3: Disgraced former Today host Matt Lauer has come out guns blazing in his own defense claiming the rape charges against him were not only false but widely embraced by the #MeToo movement without proper verification

Page 4: Ryan Seacrest shocked audiences with his slurred speech and shriveled eye on the finale of American Idol prompting fears he could go blind, busybody Jennifer Aniston and cagey ex-husband Justin Theroux are playing cat-and-mouse with each other about their love lives -- while Justin’s been living the single life since their 2017 split Jen is doing everything she can to get the details about his dates

Page 5: Celebrity Cov-Idiot of the Week -- Maurice Fayne has been arrested for taking millions in emergency money from the government and spending it on over-the-top blind like a Rolex watch, a diamond bracelet and a 5.73 carat diamond ring plus leasing a Rolls-Royce Wraith and paying $40,000 in back child support from money loaned his company under the Paycheck Protection Program which is supposed to be used to prop up small companies during the COVID-19 crisis

Page 6: The tragic overdose death of Melissa Etheridge’s son Beckett Cypher has insiders fearing for the well-being of his sperm-donating dad rock legend David Crosby -- David had an active role in the boy’s life and with his long list of health woes his friends are afraid he won’t be able to stand the strain of a loss like this

Page 7: Wannabe actor Prince Harry is so desperate to make it big in Tinseltown that he’s subjecting himself to a grueling Hollywood boot camp and has signed up for a string of special classes and training sessions to follow in the footsteps of his actress wife Meghan Markle, Chip Gaines is going to trial in a million-dollar lawsuit against former partners who accused him of swindling them out of a fortune

Page 8: Last year doctors concluded that Dolly Parton’s face had been partially paralyzed by Bell’s palsy and she may never sing again -- two videos last month showed her barely able to move her lips and struggling to get her words out and medical experts have warned she also may have suffered a ministroke, Brian Austin Green finally admitted his marriage to Megan Fox is finished

Page 9: Phyllis George was hailed as a TV pioneer when she broke up the boys’ club as the first female anchor of The NFL Today but faced humiliation after being shredded by horrific reviews as an anchor on CBS Morning News -- Phyllis died brokenhearted at 70 following a long illness 30 years after being run out of network television

Page 10: Hot Shots -- Kristin Chenoweth and her dog Thunder, Chris Sullivan on a bike ride in Brentwood, Pierce Brosnan goes snorkeling in Hawaii, Dean McDermott and son Beau

Page 11: Tom Cruise is keeping his romance with Sofia Boutella secret and is even donning disguises to avoid detection when he sneaks out to see his co-star from The Mummy, Zooey Deschanel’s pals think her hot romance with Property Brothers star Jonathan Scott will be a flash in the pan because she’s only interested in him for booty calls and raising her profile

Page 12: Straight Shuter -- comedian Michael Showalter with shopping bags and coffee (picture), in a 2008 interview with Beyonce on the Tyra Banks Show all the questions were cleared in advance with Beyonce, friends and fans are worried about Adele’s recently unveiled massive weight loss because this is a cry for help from someone who’s always claimed she was very comfortable being her size and would never go all Hollywood skinny, now that Bruce Willis and Demi Moore have spent time together in lockdown the former couple are looking to make it permanent with Demi moving in with Bruce and his wife Emma and Emma is the driving force behind the idea -- she loves Demi and wants to get a place where they can all live together, super-healthy Gwyneth Paltrow didn’t always live on a strict diet but as a struggling actress she seemed to survive on cigarettes alone

Page 13: Kristin Cavallari’s diva behavior was behind the demise of her reality show as ratings for E!’s Very Cavallari plummeted in the third season and many of the crew say it was because she’s a royal pain, blowhard Alec Baldwin has been browbeating his pregnant wife in lockdown after Hilaria offered to cut his hair and he replied I don’t think she knows what she’s doing -- Hilaria and Alec hoped her latest pregnancy would boost their sagging union but his behavior may be a sign that the glow of the pregnancy has worn off, Jonah Hill doesn’t go anywhere without his dog Carmela but his pals said the dog stinks

Page 14: True Crime

Page 15: Internet hackers who stole a trove of celebrities’ information from law firm Grubman Shire Meiselas & Sacks are getting desperate as the FBI closes in on their $42 million extortion scheme, devastated Mary-Kate Olsen is begging sister Ashley Olsen for help navigating her ugly divorce from Olivier Sarkozy and the twins are working up a game plan to protect the $500 million fortune they built together from the French banker

Page 18: Real Life

Page 19: George Clooney has resurrected his decades-long feud with romance-novel cover icon Fabio Lanzoni which was so bad the two had to be separated during a vicious confrontation in a Beverly Hill restaurant -- now that George moved back to L.A. after spending years at his homes in England and Italy their rivalry has reared its ugly head again because they run in a few of the same circles and word has gotten back to Fabio that George thinks he’s some type of big shot who deserves special treatment, Ruby Rose landed the role of a lifetime as the title superheroine in Batwoman but after the dark drama turned into a disaster she flew the coop -- Ruby was the face of the show and she got the blame when the writers didn’t do as good as job as they could have plus there was also a lot of fighting behind the scenes among writers and producers

Page 21: How to teach your kids

Page 22: Health Watch, Ask the Vet

Page 24: Sarah Palin and her husband Todd are no officially divorced

Page 26: Cover Story -- Doomed Du Wei was China’s ambassador to Israel and he knew too much about his country’s involvement in the COVID-19 pandemic and its evil expansion plans and he paid with his life

Page 30: Scott Disick has been hit with a second wave of heartbreak after girlfriend Sofia Richie ditched him after he checked into rehab to treat past traumas caused by the death of his parents and Sofia has already been hanging out with a new mystery man, Hollywood Hookups -- Rooney Mara and Joaquin Phoenix are expecting, Dan Soder and Katie Nolan dating, Katie Maloney-Schwartz and Tom Schwartz are ready to start a family

Page 32: Kanye West’s ridiculous rules and drastic demands have earned him the title of the worst boss in Hollywood and the bad rap has wife Kim Kardashian at her wit’s end, they’re liberal laugh legends but Bill Maher and Stephen Colbert can’t stand each other and they don’t need a camera running to batter each other with punch lines -- Stephen thinks Bill is pompous and Bill thinks Stephen is a smart-ass

Page 34: Jennifer Lawrence admitted on Amy Schumer’s new cooking show that she can’t even wait for darkness to fall before drinking alcohol and getting her private house party going -- she said she tries to wait until 6 so she has a preemptive beer at 5, Charlize Theron hates ex Sean Penn so much she pretends he doesn’t even exist -- she dated Sean for a year and a half before calling it quits in 2015 but in 2019 she insisted she’d been single for a decade

Page 36: Nicole Kidman shattered her ankle in a freak accident while running through their Nashville neighborhood and now her husband Keith Urban and concerned pals fear the effects may cripple her career

Page 42: Red Carpet Stars & Stumbles -- designer Atelier Versace -- Lupita Nyong’o, Anne Hathaway, Jessica Alba

Page 45: Spot the Differences -- Nancy Lenehan and Liza Snyder in Man with a Plan

Page 47: Odd List

#tabloid#tabloid toc#grain of salt#du wei#du wei death#valerie bertinelli#matt lauer#ryan seacrest#jennifer aniston#justin theroux#maurice fayne#david crosby#prince harry#chip gaines#dolly parton#megan fox#brian austin green#phyllis george#tom cruise#sofia boutella#zooey deschanel#jonathan scott#Kristin Cavallari#alec baldwin#jonah hill#mary-kate olsen#george clooney#fabio lanzoni#sofia richie#scott disick

0 notes

Text

The New Model Media Star Is Famous Only to You

The Media EquationWith short videos and paid newsletters, everyone from superstars to half-forgotten former athletes and even journalists can, as one tech figure put it, “monetize individuality.”

Recent videos by, from left, Gwen Jorgensen, Leonard Marshall and Terry Francona available on Cameo, a service that allows fans to buy personalized messages.Credit...CameoPublished May 24, 2020Updated May 25, 2020, 3:43 a.m. ETBack in March, I was trying to persuade my dad to stop taking the subway to work in Manhattan and join me upstate. So I paid $75 to Leonard Marshall, a retired New York Giants defensive lineman we both loved in the 1980s, to send the message.“I put a few guys in the hospital, Bob,” he told my father solemnly. “I need you to play defense in these crazy times.”It worked, and my father hasn’t been to Times Square since.I had reached Mr. Marshall through Cameo, a service that allows you to buy short videos from minor celebrities. I also used Cameo to purchase a pep talk from an Olympic triathlete for my daughter ($15), an ingratiating monologue for my new boss from a former Boston Red Sox manager ($100) and a failed Twitter joke delivered by the action star Chuck Norris ($229.99).Cameo is blowing up in this strange season because “every celebrity is really a gig economy worker,” says Steven Galanis, the company’s chief executive. They’re stuck at home, bored and sometimes hard up for cash as performances, productions and sporting events dry up. The company’s weekly bookings have grown to 70,000 from about 9,000 in early January, it says, and Mr. Galanis said he anticipated bringing in more than $100 million in bookings this year, of which the company keeps 25 percent. The company expects to sell its millionth video this week.Cameo is, on its face, a service that allows housebound idiots to blow money on silly shout-outs. Seen another way, however, it’s a new model media company, sitting at the intersection of a set of powerful trends that are accelerating in the present crisis. There’s the rise of simple, digital direct payments, which are replacing advertising as the major source of media revenue. There’s the growing power of talent, trickling down from superstars to half-forgotten former athletes and even working journalists. And there’s the old promise of the earlier internet that you could make a living if you just had “1,000 true fans" — a promise that advertising-based businesses from blogs to YouTube channels failed to deliver.In fact, in this new economy, some people may be able to make a living off just 100 true fans, as Li Jin, a former partner at the venture capital firm Andreessen Horowitz, argued recently. Ms. Jin calls this new landscape the “passion economy.” She argues that apps like Uber and DoorDash are built to erase the differences between individual drivers or food delivery people. But similar tools, she says, can be used to “monetize individuality.”Many of these trends are well developed in China, but here in the United States the passion economy covers everyone from the small merchants using Shopify to the drawing instructors of the education platform Udemy.In the mainstream heart of the media business, both artists and writers are moving quickly to find new business models as huge swaths of the media business have been wounded or shut down by the coronavirus pandemic. At Patreon, the first and broadest of the big services connecting writers and performers to audiences, the co-founder Jack Conte said he was delighted recently to see one of his favorite bands, Of Montreal, release music on the platform.“Traditional music coming to Patreon is a watershed moment,” he said.In the news business, journalists are carving out new paths on Substack, a newsletter service. Its most successful individual voices — like the China expert Bill Bishop and the liberal political writer Judd Legum — are earning well into six figures annually for sending regular newsletters to subscribers, though no individual has crossed the million-dollar mark, the company said.For some writers, Substack is a way to get their work out of the shadow of an institution. Emily Atkin felt that need intensely when a climate forum she organized last year for presidential candidates, while she was a writer for The New Republic, collapsed amid a scandal over an unrelated column about Mayor Pete Buttigieg that appeared in that publication.Image

For writers like Emily Atkin, formerly of The New Republic, Substack is a way to get their work out of the shadow of an institution.Credit...Rozette RagoNow, said Ms. Atkin, who writes a confrontational climate newsletter called Heated, she’s “shockingly hopeful.”“I don’t have any layoffs happening at my newsletter, so I’m doing better than most of the news industry,” she said.Ms. Atkin, who is 11th on Substack’s ranking of paid newsletters and was more willing than Mr. Bishop or Mr. Legum to talk in detail about the business, said she was on track to gross $175,000 this year from more than 2,500 subscribers. Out of that, she’ll pay for health care, a research assistant and a 10 percent fee to Substack, among other costs.For others, Substack is a way to carry on with work they’re passionate about when a job goes away, as Lindsay Gibbs found when the liberal news site ThinkProgress shut down last year and took her beat on sexism in sports with it.Now, she has more than 1,000 subscribers to Power Plays, paying as much as $72 a year.Both of them started with $20,000 advances from the platform.“The audience connecting directly with you and paying directly is a revolutionary change to the business model,” Substack’s chief executive, Chris Best, told me.It’s hard to imagine even the most successful writers, like Mr. Bishop and Ms. Atkin, posing a major threat to the titans of media anytime soon, especially as a few big institutions — whether in news or streaming video — dominate each market. But the two writers’ path to success points to the reality that the biggest threat to those institutions may come from their talented employees. Updated May 20, 2020 How can I protect myself while flying? If air travel is unavoidable, there are some steps you can take to protect yourself. Most important: Wash your hands often, and stop touching your face. If possible, choose a window seat. A study from Emory University found that during flu season, the safest place to sit on a plane is by a window, as people sitting in window seats had less contact with potentially sick people. Disinfect hard surfaces. When you get to your seat and your hands are clean, use disinfecting wipes to clean the hard surfaces at your seat like the head and arm rest, the seatbelt buckle, the remote, screen, seat back pocket and the tray table. If the seat is hard and nonporous or leather or pleather, you can wipe that down, too. (Using wipes on upholstered seats could lead to a wet seat and spreading of germs rather than killing them.) What are the symptoms of coronavirus? Common symptoms include fever, a dry cough, fatigue and difficulty breathing or shortness of breath. Some of these symptoms overlap with those of the flu, making detection difficult, but runny noses and stuffy sinuses are less common. The C.D.C. has also added chills, muscle pain, sore throat, headache and a new loss of the sense of taste or smell as symptoms to look out for. Most people fall ill five to seven days after exposure, but symptoms may appear in as few as two days or as many as 14 days. How many people have lost their jobs due to coronavirus in the U.S.? Over 38 million people have filed for unemployment since March. One in five who were working in February reported losing a job or being furloughed in March or the beginning of April, data from a Federal Reserve survey released on May 14 showed, and that pain was highly concentrated among low earners. Fully 39 percent of former workers living in a household earning $40,000 or less lost work, compared with 13 percent in those making more than $100,000, a Fed official said. Is ‘Covid toe’ a symptom of the disease? There is an uptick in people reporting symptoms of chilblains, which are painful red or purple lesions that typically appear in the winter on fingers or toes. The lesions are emerging as yet another symptom of infection with the new coronavirus. Chilblains are caused by inflammation in small blood vessels in reaction to cold or damp conditions, but they are usually common in the coldest winter months. Federal health officials do not include toe lesions in the list of coronavirus symptoms, but some dermatologists are pushing for a change, saying so-called Covid toe should be sufficient grounds for testing. Can I go to the park? Yes, but make sure you keep six feet of distance between you and people who don’t live in your home. Even if you just hang out in a park, rather than go for a jog or a walk, getting some fresh air, and hopefully sunshine, is a good idea. How do I take my temperature? Taking one’s temperature to look for signs of fever is not as easy as it sounds, as “normal” temperature numbers can vary, but generally, keep an eye out for a temperature of 100.5 degrees Fahrenheit or higher. If you don’t have a thermometer (they can be pricey these days), there are other ways to figure out if you have a fever, or are at risk of Covid-19 complications. Should I wear a mask? The C.D.C. has recommended that all Americans wear cloth masks if they go out in public. This is a shift in federal guidance reflecting new concerns that the coronavirus is being spread by infected people who have no symptoms. Until now, the C.D.C., like the W.H.O., has advised that ordinary people don’t need to wear masks unless they are sick and coughing. Part of the reason was to preserve medical-grade masks for health care workers who desperately need them at a time when they are in continuously short supply. Masks don’t replace hand washing and social distancing. What should I do if I feel sick? If you’ve been exposed to the coronavirus or think you have, and have a fever or symptoms like a cough or difficulty breathing, call a doctor. They should give you advice on whether you should be tested, how to get tested, and how to seek medical treatment without potentially infecting or exposing others. How do I get tested? If you’re sick and you think you’ve been exposed to the new coronavirus, the C.D.C. recommends that you call your healthcare provider and explain your symptoms and fears. They will decide if you need to be tested. Keep in mind that there’s a chance — because of a lack of testing kits or because you’re asymptomatic, for instance — you won’t be able to get tested. How can I help? Charity Navigator, which evaluates charities using a numbers-based system, has a running list of nonprofits working in communities affected by the outbreak. You can give blood through the American Red Cross, and World Central Kitchen has stepped in to distribute meals in major cities. That dynamic was on display in a confrontation between Barstool Sports and the hosts of its hit podcast, “Call Her Daddy,” as my colleague Taylor Lorenz reported last week. Media company stars, with big social media followings and more and more ways to make money, are less and less willing to act like employees. (“The ‘Call Her Daddy’ girls would be making over half a million dollars a year with me,” Mr. Galanis of Cameo said. “High Pitch Erik from ‘The Howard Stern Show’ is making low six figures.”)Substack represents a radically different alternative, in which the “media company” is a service and the journalists are in charge. It’s what one of the pioneers of the modern newsletter business, the tech analyst Ben Thompson, describes as a “faceless” publisher. And you can imagine it or its competitors offering more services, from insurance to marketing to editing, reversing the dynamic of the old top-down media company and producing something more like a talent agency, where the individual journalist is the star and the boss, and the editor is merely on call.ImageThe popularity of “Tiger King,” starring Lauren and Jeff Lowe, left, led Cameo to sign up Kelci Saffery, right, who had a lesser role in the documentary.Credit...CameoThe new passion-economy media companies are converging in some ways. The ones like Patreon and Substack, which operate primarily in the background, are now looking at careful ways to bundle their offerings, their executives said. Medium, which allows you to subscribe to its full bundle of writers, is looking for ways to foster more intimate connections between individuals and their followers, its founder, Ev Williams, said. Cameo, which has a front page in its app and website but is mostly selling one-off shout-outs, is shifting toward a model that is more like subscribing to a celebrity: For a price, you’ll be able to send direct messages that appear in a priority inbox.“We think messages back and forth is where the puck is going with Cameo,” Mr. Galanis said.Is this good news? The rise of these new companies could further shake our faltering institutions, splinter our fragmented media and cement celebrity culture. Or they could pay for a new wave of powerful independent voices and offer steady work for people doing valuable work — like journalists covering narrow, important bits of the world — who don’t have another source of income. Like the whole collision of the internet and media, it will doubtless be some of both.In Silicon Valley, where the East Coast institutions of journalism are often seen as another set of hostile gatekeepers to be disrupted, leading figures are cheering a possible challenger. Mr. Best, the Substack chief, told me that the venture capitalist Marc Andreessen, whose firm has invested in the company, said he hoped it would “do to big media companies what venture capital did to big tech companies” — that is, peel off their biggest stars with the promise of money and freedom and create new kinds of news companies.One of the things I find most heartening in these unequal times, though, is the creation of some new space for a middle class of journalists and entertainers — the idea that you can make a living, if not a killing, by working hard for a limited audience. Even people who play a modest role in a cultural phenomenon can get some of the take, which was what happened with the Netflix documentary “Tiger King.”When the documentary hit big in March, Cameo signed up 10 of its ragtag cast of, mostly, amateur zookeepers. That came just in time for Kelci Saffery, best known on the show for returning to work soon after losing a hand to a tiger. Mr. Saffery now lives in California, and lost his job at a furniture warehouse when the pandemic hit. To his shock, he has earned about $17,000, as well as a measure of recognition, even as the requests are slowing down.“Every day I’m at least getting one, and for me that still means that one person every day is thinking, ‘Hey, this would be cool,’ and to me that’s significant,” he said. As for the money, “that could send one of my children to college.” Read More Read the full article

0 notes

Text

Trump Is Inciting a Coronavirus Culture War to Save Himself

The president’s attempt to racialize the pandemic is a cover-up of the fact that he trusted false reassurances from Beijing.

By Adam Serwer | Published March 24, 2020 9:12 AM ET | The Atlantic | Posted March 24, 2020 |

Donald Trump had a message for the Chinese government at the beginning of the year: Great job!

“China has been working very hard to contain the Coronavirus. The United States greatly appreciates their efforts and transparency,” Trump tweeted on January 24. “It will all work out well. In particular, on behalf of the American People, I want to thank President Xi!”

Over the next month, the president repeatedly praised the Chinese government for its handling of the coronavirus, which appears to have first emerged from a wildlife market in the transportation hub of Wuhan, China, late last year. Trump lauded Chinese President Xi Jinping as “strong, sharp and powerfully focused on leading the counterattack on the Coronavirus,” and emphasized that the U.S. government was “working closely” with China to contain the disease.

For months, Trump himself referred to the illness as “the coronavirus.” In early March, though, several conservative media figures began using Wuhan virus or Chinese virus instead. On March 16, Trump himself began to refer to it as the “Chinese Virus,” prompting commentators to charge that he was racializing the epidemic. In contrast, some early media reports had referred to the illness as “the Wuhan virus,” but most outlets switched to referring to “the coronavirus” not long after it emerged, following the advice of public-health experts concerned about the very possibility of stigma from associating deadly diseases with a particular ethnic group or location. Some conservative outlets subsequently began attacking critics of the president’s change in language as propagandists for the Chinese Communist Party.

Even before Trump’s adoption of Chinese virus, Asian Americans had been facing a wave of discrimination, harassment, and violence in response to the epidemic. The president’s rhetoric did not start this backlash, but the decision to embrace the term Chinese virus reinforced the association between a worldwide pandemic and people of a particular national origin. Legitimizing that link with all the authority of the office of the president of the United States is not just morally abhorrent, but dangerous.

The president’s now-constant use of Chinese virus is the latest example of a conservative phenomenon you might call the racism rope-a-dope (with apologies to the late boxer Muhammad Ali, who coined the latter half of the term to describe his strategy of luring an opponent into wearing himself out). Trump and his acolytes are never more comfortable than when they are defending expressions of bigotry as plain common sense, and accusing their liberal critics of being oversensitive snowflakes who care more about protecting “those people” than they do about you. They seek to reduce any political dispute to this simple equation whenever possible. “I want them to talk about racism every day,” the former Trump adviser Steve Bannon told The American Prospect in 2017. “If the left is focused on race and identity, and we go with economic nationalism, we can crush the Democrats.”

In this instance, though, the gambit served two additional purposes: distracting the public from Trump’s catastrophic mishandling of the coronavirus pandemic, and disguising the fact that Trump’s failures stemmed from his selfishness and fondness for authoritarian leaders, which in turn made him an easy mark for the Chinese government’s disinformation.

Conservatives are fond of telling liberals who accuse the Republican Party of prejudice, “This is how you got Trump,” a retort that is less a rebuttal than an affirmation. Trump understands that overt expressions of prejudice draw condemnation from liberals, which in turn rallies his own base around him. Calling the coronavirus the “Chinese virus” not only informs Trump’s base that foreigners are the culprits, it also offers his supporters the emotional satisfaction of venting fury at liberals for unfairly accusing conservatives of racism. The point is to turn a pandemic that threatens both mass death and the collapse of the American economy into a culture-war argument in which the electorate can be polarized along partisan lines.

Conservatives insist that the Chinese government bears a great deal of responsibility for the outbreak, and that the president is merely holding the CCP accountable. Liberals, they argue, by criticizing the president’s rhetoric as racist, are falling into a trap set by Chinese propagandists, who are hoping to characterize any criticism of Beijing’s role in the outbreak as racism.

This criticism contains an element of truth. As The Wall Street Journal reported in early March, the Chinese government lied about the threat posed by COVID-19 and the coronavirus’s transmissibility to humans, and dragged its feet in informing the public, even silencing a whistleblower, Li Wenliang, who tried to warn the country about the threat of the disease before succumbing to it himself. “By not moving aggressively to warn the public and medical professionals, public-health experts say, the Chinese government lost one of its best chances to keep the disease from becoming an epidemic,” The New York Times reported in early February.

Since that report, Chinese officials have engaged in a propaganda offensive, expelling American journalists, minimizing their early missteps, and putting forth a conspiracy theory that the virus was engineered by the U.S. military. Compared with all this, the president’s defenders argue, Trump referring to the coronavirus as the “Chinese virus” seems trivial.

Lost in that comparison, however, is the fact that the most effective target of CCP disinformation has been Trump himself. The president’s public praise of the Chinese government’s response was not simply a public stance. According to The Washington Post, at the same time that Trump was stating that Beijing had the disease under control, U.S. intelligence agencies were already warning him that “Chinese officials appeared to be minimizing the severity of the outbreak.”

Administration officials directly warned Trump of the danger posed by the virus, but “Trump’s insistence on the contrary seemed to rest in his relationship with China’s President Xi Jingping, whom Trump believed was providing him with reliable information about how the virus was spreading in China,” The Washington Post reported, “despite reports from intelligence agencies that Chinese officials were not being candid about the true scale of the crisis.”

The right’s rhetorical shift then, is not just another racism rope-a-dope, an attempt to bait the left into a culture-war argument and divert attention from the president’s disastrous handling of the coronavirus pandemic. It is also an attempt to cover up the fact that the Chinese government’s propaganda campaign was effective in that it helped persuade the president of the United States not to take adequate precautionary measures to stem a tide of pestilence that U.S. government officials saw coming.

Now faced with the profound consequences of that decision, the right has settled on a strategy that does little to hold Beijing accountable for its mishandling of the coronavirus, but instead plays into Beijing’s attempt to cast any criticism of the Chinese government’s response as racism. Not only is the Chinese virus gambit morally objectionable but it is also inimical to the strategic interests the Trump administration was supposedly pursuing. The term makes no distinction between China’s authoritarian government and people who happen to be of Chinese origin, and undermines the unified front the Trump administration would want if it were actually concerned with countering Chinese-government propaganda.

Instead, the Trump administration has chosen a political tactic that strengthens the president’s political prospects by polarizing the electorate, and covers up his own role as Xi’s patsy, while making its own pushback against CCP propaganda less effective. The Trump administration might have chosen any number of methods to hold the Chinese government accountable for its mishandling of the outbreak that would not legitimize anti-Asian racism; it settled on a verbal taunt ineffective at countering disinformation but well suited to pursuing the president’s political interests.

This approach reflects the most glaring flaws of Trumpist governance, which have become only more acute during the coronavirus crisis: It exacerbates rather than solves the underlying problem, placing the president’s political objectives above all other concerns, even the ones both the president and his supporters claim to value.

A week after first deploying the term Chinese virus, even the president seemed to have regrets about the tactic. “It seems like there could be a little bit of nasty language toward Asian Americans in our country, and I don’t like that at all,” Trump told reporters at a press conference yesterday afternoon. "These are incredible people, they love our country, and I’m not gonna let it happen.”

The president did not say who might be using the “nasty language” or what that “nasty language” was, nor did he offer any theories as to why anyone might be using it.

Donald Trump had a message for the Chinese government at the beginning of the year: Great job!

“China has been working very hard to contain the Coronavirus. The United States greatly appreciates their efforts and transparency,” Trump tweeted on January 24. “It will all work out well. In particular, on behalf of the American People, I want to thank President Xi!”

Over the next month, the president repeatedly praised the Chinese government for its handling of the coronavirus, which appears to have first emerged from a wildlife market in the transportation hub of Wuhan, China, late last year. Trump lauded Chinese President Xi Jinping as “strong, sharp and powerfully focused on leading the counterattack on the Coronavirus,” and emphasized that the U.S. government was “working closely” with China to contain the disease.

For months, Trump himself referred to the illness as “the coronavirus.” In early March, though, several conservative media figures began using Wuhan virus or Chinese virus instead. On March 16, Trump himself began to refer to it as the “Chinese Virus,” prompting commentators to charge that he was racializing the epidemic. In contrast, some early media reports had referred to the illness as “the Wuhan virus,” but most outlets switched to referring to “the coronavirus” not long after it emerged, following the advice of public-health experts concerned about the very possibility of stigma from associating deadly diseases with a particular ethnic group or location. Some conservative outlets subsequently began attacking critics of the president’s change in language as propagandists for the Chinese Communist Party.

Even before Trump’s adoption of Chinese virus, Asian Americans had been facing a wave of discrimination, harassment, and violence in response to the epidemic. The president’s rhetoric did not start this backlash, but the decision to embrace the term Chinese virus reinforced the association between a worldwide pandemic and people of a particular national origin. Legitimizing that link with all the authority of the office of the president of the United States is not just morally abhorrent, but dangerous.

The president’s now-constant use of Chinese virus is the latest example of a conservative phenomenon you might call the racism rope-a-dope (with apologies to the late boxer Muhammad Ali, who coined the latter half of the term to describe his strategy of luring an opponent into wearing himself out). Trump and his acolytes are never more comfortable than when they are defending expressions of bigotry as plain common sense, and accusing their liberal critics of being oversensitive snowflakes who care more about protecting “those people” than they do about you. They seek to reduce any political dispute to this simple equation whenever possible. “I want them to talk about racism every day,” the former Trump adviser Steve Bannon told The American Prospect in 2017. “If the left is focused on race and identity, and we go with economic nationalism, we can crush the Democrats.”

In this instance, though, the gambit served two additional purposes: distracting the public from Trump’s catastrophic mishandling of the coronavirus pandemic, and disguising the fact that Trump’s failures stemmed from his selfishness and fondness for authoritarian leaders, which in turn made him an easy mark for the Chinese government’s disinformation.

Conservatives are fond of telling liberals who accuse the Republican Party of prejudice, “This is how you got Trump,” a retort that is less a rebuttal than an affirmation. Trump understands that overt expressions of prejudice draw condemnation from liberals, which in turn rallies his own base around him. Calling the coronavirus the “Chinese virus” not only informs Trump’s base that foreigners are the culprits, it also offers his supporters the emotional satisfaction of venting fury at liberals for unfairly accusing conservatives of racism. The point is to turn a pandemic that threatens both mass death and the collapse of the American economy into a culture-war argument in which the electorate can be polarized along partisan lines.

Conservatives insist that the Chinese government bears a great deal of responsibility for the outbreak, and that the president is merely holding the CCP accountable. Liberals, they argue, by criticizing the president’s rhetoric as racist, are falling into a trap set by Chinese propagandists, who are hoping to characterize any criticism of Beijing’s role in the outbreak as racism.

This criticism contains an element of truth. As The Wall Street Journal reported in early March, the Chinese government lied about the threat posed by COVID-19 and the coronavirus’s transmissibility to humans, and dragged its feet in informing the public, even silencing a whistleblower, Li Wenliang, who tried to warn the country about the threat of the disease before succumbing to it himself. “By not moving aggressively to warn the public and medical professionals, public-health experts say, the Chinese government lost one of its best chances to keep the disease from becoming an epidemic,” The New York Times reported in early February.

Since that report, Chinese officials have engaged in a propaganda offensive, expelling American journalists, minimizing their early missteps, and putting forth a conspiracy theory that the virus was engineered by the U.S. military. Compared with all this, the president’s defenders argue, Trump referring to the coronavirus as the “Chinese virus” seems trivial.

Lost in that comparison, however, is the fact that the most effective target of CCP disinformation has been Trump himself. The president’s public praise of the Chinese government’s response was not simply a public stance. According to The Washington Post, at the same time that Trump was stating that Beijing had the disease under control, U.S. intelligence agencies were already warning him that “Chinese officials appeared to be minimizing the severity of the outbreak.”

Administration officials directly warned Trump of the danger posed by the virus, but “Trump’s insistence on the contrary seemed to rest in his relationship with China’s President Xi Jingping, whom Trump believed was providing him with reliable information about how the virus was spreading in China,” The Washington Post reported, “despite reports from intelligence agencies that Chinese officials were not being candid about the true scale of the crisis.”

The right’s rhetorical shift then, is not just another racism rope-a-dope, an attempt to bait the left into a culture-war argument and divert attention from the president’s disastrous handling of the coronavirus pandemic. It is also an attempt to cover up the fact that the Chinese government’s propaganda campaign was effective in that it helped persuade the president of the United States not to take adequate precautionary measures to stem a tide of pestilence that U.S. government officials saw coming.

Now faced with the profound consequences of that decision, the right has settled on a strategy that does little to hold Beijing accountable for its mishandling of the coronavirus, but instead plays into Beijing’s attempt to cast any criticism of the Chinese government’s response as racism. Not only is the Chinese virus gambit morally objectionable but it is also inimical to the strategic interests the Trump administration was supposedly pursuing. The term makes no distinction between China’s authoritarian government and people who happen to be of Chinese origin, and undermines the unified front the Trump administration would want if it were actually concerned with countering Chinese-government propaganda.

Instead, the Trump administration has chosen a political tactic that strengthens the president’s political prospects by polarizing the electorate, and covers up his own role as Xi’s patsy, while making its own pushback against CCP propaganda less effective. The Trump administration might have chosen any number of methods to hold the Chinese government accountable for its mishandling of the outbreak that would not legitimize anti-Asian racism; it settled on a verbal taunt ineffective at countering disinformation but well suited to pursuing the president’s political interests.

This approach reflects the most glaring flaws of Trumpist governance, which have become only more acute during the coronavirus crisis: It exacerbates rather than solves the underlying problem, placing the president’s political objectives above all other concerns, even the ones both the president and his supporters claim to value.

A week after first deploying the term Chinese virus, even the president seemed to have regrets about the tactic. “It seems like there could be a little bit of nasty language toward Asian Americans in our country, and I don’t like that at all,” Trump told reporters at a press conference yesterday afternoon. "These are incredible people, they love our country, and I’m not gonna let it happen.”

The president did not say who might be using the “nasty language” or what that “nasty language” was, nor did he offer any theories as to why anyone might be using it.

*********

Here Is a Catalog of Lies Trump Has Told About the Coronavirus

A president known for bending the truth is now facing a reality he can’t easily spin.

By CHRISTIAN Paz |

In the 11 days since he declared the coronavirus pandemic a national emergency, President Donald Trump has repeatedly lied about this once-in-a-generation crisis.

Here, a collection of the biggest lies he’s told as the nation barrels toward a public-health and economic calamity. This post will be updated as needed.

On the Nature of the Virus

When: Friday, February 7 and Wednesday, February 19

The claim: The coronavirus would weaken “when we get into April, in the warmer weather, that has a very negative effect on that and that type of a virus.”

The truth: It’s too early to tell if the virus’s spread will be dampened by warmer conditions. Respiratory viruses can be seasonal, but the World Health Organization says that the new coronavirus “can be transmitted in ALL AREAS, including areas with hot and humid weather.”

When: Thursday, February 27

The claim: The outbreak would be temporary: "It's going to disappear. One day it's like a miracle, it will disappear."

The truth: Anthony Fauci, the director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, warned days later that he was concerned that “as the next week or two or three go by, we're going to see a lot more community-related cases.”

When: Monday, March 23

The claim: If the economic shutdown continues, deaths by suicide “definitely would be in far greater numbers than the numbers that we’re talking about” for COVID-19 deaths.

The truth: The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimate that, in a worst-case scenario, 200,000 to 1.7 million Americans could die from COVID-19, The New York Times reports. Other estimates place the number of possible deaths at 1.1 million to 1.2 million. According to the CDC, suicide is one of the leading causes of death in the United States. But the number of people who died by suicide in 2017, for example, was roughly 47,000, nowhere near the COVID-19 estimates.

*********

Americans’ Revulsion for Trump Is Underappreciated

As Democrats fret about their own prospects, many fail to recognize the president’s fundamental weakness.

By Stanley Greenberg, Political strategist and polling adviser | Published March 24, 2020 6:00 AM ET| The Atlantic | Posted March 24, 2020 |

The release on Friday of an ABC News/Ipsos poll indicating that 55 percent of Americans approved of Donald Trump’s handling of the coronavirus—12 points higher than the previous week—prompted another round of fatalistic chatter in certain quarters of the political establishment. Shocked by Trump’s victory in 2016, some left-leaning commentators and rank-and-file Democrats alike have been steeling themselves for his reelection in 2020, noting that most presidents win second terms; that, at least before the pandemic, the economy was humming along; and more recently that, during moments of national disaster, Americans tend to rally around the leader they have.

But these nuggets of conventional political wisdom obscure something fundamental—something that even Democrats have trouble seeing: The United States is in revolt against Donald Trump, and the likely Democratic nominee, former Vice President Joe Biden, already holds a daunting lead over Trump in the battleground states that will decide the 2020 election. By way of disclosure, I am a Democratic pollster; for professional and personal reasons alike, I want Democratic candidates to succeed. But no matter what, I also want candidates and party operatives to base decisions—such as where and how to campaign—on an accurate view of the political landscape. At the moment, Democrats are underestimating their own strength and misperceiving the sources of it.

[ Peter Wehner: The Trump presidency is Over SEE TIMELINE]

Every time Americans have gone to the polls since Trump took office, they have pushed back hard against him. The blue wave that began in state elections in 2017 grew bigger in the 2018 midterms and bigger yet in 2019. Trump focused the Republican Party’s whole 2018 congressional campaign on immigrant caravans and the border wall, and he lost. Trump held rallies in support of the Republican gubernatorial candidates on the last nights before elections in the deep-red states of Kentucky and Louisiana, and they lost. The GOP losses right through the end of 2019 were produced by dramatic, growing gains for Democrats in the nation’s suburbs. Democrats took total control of the Virginia legislature, where the party held on to all the suburban seats it had flipped two years earlier and gained six more.

Even so, a CBS News poll taken late last month found that 65 percent of Americans and more than a third of Democrats believed that Trump would win reelection. Trump has been confidently stalking Democrats, holding exuberant rallies in each of the early caucus and primary states.

For a time, each week’s voting made Trump’s position look stronger. Bernie Sanders took a commanding delegate lead after the Nevada caucus, and Democratic leaders and many others in the anti-Trump world panicked. Sanders was widely viewed as Trump’s preferred opponent, and he looked unstoppable in the nomination battle. Republicans were rubbing their hands together, eager to spend millions “educating” the country about Sanders’s long-ago honeymoon in Moscow and his socialist plans to destroy American health care. Even after Joe Biden stunned himself and all the political analysts by winning the South Carolina primary by nearly 30 points, much of the subsequent commentary dwelled on the nearly 30 percent of Sanders voters who were not certain they would vote for the eventual nominee. The New York Times soon published a front-page story on the socialist podcast Chapo Trap House and a broader movement calling itself the “Dirtbag Left,” which embraced Sanders and attacked his Democratic opponents. The alienation of people like these would reelect Trump, supporters of other Democratic candidates feared.

But Democratic voters took over the nominating process and changed everything. No group of voters felt more threatened by Donald Trump than African Americans, and no group was more determined to see him defeated. When a stunning 61 percent of black voters in South Carolina chose Joe Biden, other Democrats got the message. Turnout surged on Super Tuesday, led by Texas with a 45 percent increase over 2016 and Virginia with a 70 percent increase, for the highest turnout in state history. The increase was led by African Americans and voters in the suburbs. Two weeks later in Michigan, Tim Alberta declared in Politico, “Democratic turnout exploded,” led by a 45 percent increase in the state’s richest county.

Trump has nationalized our politics around himself and his job performance, and that has created a nine-point headwind for the Republican Party. While the pessimists obsess over any of Trump’s most favorable polls, particularly in the Electoral College battleground states, Trump has never raised his approval rating above the low 40s in FiveThirtyEight’s average of public polls; 52 to 53 percent disapprove of his performance in office. And that remains true during the current crisis.

[ Read: Why Trump intentionally misnames the Coronavirus SEE TIMELINE]

Trump has improved his numbers with the evangelical Christians, Tea Party supporters, and observant Catholics who make up the core of his Republican Party, but it is a diminished party. The percentage of people identifying as Republican since Trump took office has dropped from 39 to 36 percent, according to an NBC News/Wall Street Journal poll. Trump has pushed moderates out of the party, and those moderates are changing their voting patterns accordingly. Fully 5 percent of the voters in the South Carolina Democratic primary had previously voted in the state’s Republican primary. In Michigan, Republican strategists tried to make sense of the 56 percent increase in Democratic turnout in Livingston County, a white, college-educated, upper-class community that Trump won by 30 points. Republicans are shedding voters.

Why don’t supposedly savvy people see the revolt that’s happening before their very eyes?

Well, everyone should pay less attention to the interviews with Trump voters at his rallies—of course people who attend his events still support him—and more to the fundamental changes in public attitudes that undercut Republican prospects. The signature policies that are cheered at every Trump rally are unpopular with most Americans.

Trump’s reelection campaign is premised on voters embracing an “America first” vision on trade and immigration, a defense of the traditional family with a male breadwinner, and a battle for the forgotten working class. But the percentage of Americans who believe that free trade between the United States and other countries is mostly a good thing has jumped from 43 to 56 percent in three years—reaching 67 percent among Democrats. The percentage who believe that foreign trade is an opportunity for economic growth rather than a “threat to the economy” has jumped from about 60 to 80 percent since Trump took office. His tariffs and trade war have united much of the country against him.

As he demanded that Congress fund a border wall with Mexico, pushed migrants into new camps inside and outside the U.S., and dramatically reduced legal immigration, Americans suddenly embraced immigrants and America’s immigrant history. The percentage offering a warm response to the phrase immigrants to the U.S. grew from 52 percent in January 2019 to 59 percent in July and spiked in September to 67 percent.

Women started the revolt against Trump’s America the day after his inauguration, and their opposition continues to deepen. In 2018, Democrats increased their margins relative to 2016 by more than double digits with white college-educated women—Hillary Clinton’s base—but also with white unmarried women and white working-class women. In 2018, black women turned out to vote in record numbers and gave Republicans only 7 percent of their votes.

The women’s wave grew to a potential tsunami when I began testing the leading Democratic candidates against Trump in the 2020 presidential contest earlier this month. With Joe Biden as the candidate, Trump won only 4 percent of African American women. He lost Hispanic women by 25 points, white unmarried women by 18, white college women by 14, and white Millennial women by 12—all at historic highs for Democrats.

Yet while the revulsion that women and suburbanites show toward Trump registers with elite commentators and Democratic operatives, the role that working-class voters have played in Republicans’ recent electoral troubles mostly does not.

The white working class forms 46 percent of registered voters; most are women. Although these voters’ excitement and hopes made Trump’s 2016 victory possible, they were demonstrably disillusioned just a year into Trump’s presidency. They pulled back when the Republicans proposed big cuts in domestic spending, Medicare, and Medicaid and made health insurance more uncertain and expensive, while slashing taxes for corporations and their lobbyists. In the midterms, Democrats ran on cutting prescription-drug costs, building infrastructure, and limiting the role of big money, and a portion of the white working class joined the revolt. The 13-point shift against Trump was three times stronger than the shift in the suburbs that got everyone’s attention.

Trump won white working-class women by 27 points in 2016. But at the end of 2019, Biden was running dead even with Trump nationally. Eight months before the election, Democracy Corps—of which I am a co-founder—and the Center for Voter Information conducted a survey in the battleground states that gave Trump his Electoral College victory. (Trump won them by 1.3 points in 2016.) Our recent findings showed Biden trailing Trump with white working-class women by just eight points in a head-to-head contest. These numbers herald an earthquake, but they have not penetrated elite commentators’ calculations about whether Trump will win in 2020.

When President Barack Obama urged voters to “build on the progress” by supporting Hillary Clinton in 2016, he underestimated how much working-class voters felt Democrats had pushed their concerns out of sight. Democratic presidents championed NAFTA and presided over the outsourcing of jobs; bank bailouts, lost homes and wages, and mandatory health insurance further alienated working people; and Clinton did not hide her closeness with Wall Street or her discomfort campaigning to win working-class and rural communities. So working people had lots of reasons to consider voting for Donald Trump, who said he was battling for the “forgotten Americans,” but shocked Clinton supporters could see only the race cards he played to great effect the second he got off the escalator at Trump Tower. Now the failure of political elites to see the role working people played in the Democratic victories of 2018 makes them believe that Trump is headed for reelection.

Earlier this year, I assembled an online sample of 250 Democratic base and swing voters to watch the president’s State of the Union address. They reacted second by second to his words and claims and, afterward, drew conclusions about the president. They turned their thumbs down when Trump hailed the “great American comeback.” He lost white working-class men and women on the comeback of jobs and income and “the state of the union is stronger than ever.” After listening to the president for more than an hour, 63 percent said he’s “governing for billionaires and big money elites.” The elites may not see working people, but working people see Donald Trump.

Perhaps sensing the danger to the incumbent, Republican leaders in Congress appear willing to approve a massive stimulus plan in response to the coronavirus—a stimulus significantly larger than the one they ravaged Obama for pushing through. That could raise Trump’s prospects—but the potentially catastrophic human consequences of COVID-19 could also work against him. Trump, one can safely assume, will do almost anything to get reelected, and my fellow Democrats will do all they can to defeat him. But they also need to take into account this basic fact: Large portions of the electorate, knowing what the stakes are, have been rebelling against Trump for three years and are eager to finish off his vision of America.

_____

Stanley B. Greenberg is a pollster who worked for Bill Clinton, Al Gore, Tony Blair, and Nelson Mandela. He is the author of R.I.P. G.O.P.: How the New America is Dooming the Republicans.

*********

Trump Can’t Even Imitate a Normal President

He couldn’t keep the impression going for an entire press briefing.

BY Quinta Jurecic and Benjamin Wittes

| Published March 24, 2020 5:45 AM ET| The Atlantic | Posted March 24, 2020 |

For a brief moment during Saturday’s White House coronavirus briefing, Donald Trump almost—not quite, but almost—sounded like a normal president. He opened the briefing by noting that “governors, mayors, the businesses, charities, and citizens are all working with urgency and speed toward one common goal, which is saving American lives.” He praised “national solidarity.” He thanked federal and state officials who were “working hard.” He even talked about international cooperation with Canada and Mexico. He described what the administration is doing and praised legislative efforts to pass relief bills and gubernatorial efforts, including those of Democratic governors, to manage the crisis in the states.

It didn’t last. By the end of the briefing, Trump’s imperfect imitation of a typical president had slipped: Asked about a potential new drug cocktail that he had tweeted about earlier in the day, Trump declared, “I feel very good about it”—leaving Anthony Fauci, the director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, who has become the public face of the administration’s pandemic response, to diplomatically acknowledge that the president was engaging in magical thinking. Trump had a moment during which—if you ignored the distinctive sound of his voice, you could almost imagine that you were listening to someone other than Trump.

[Read: How the coronavirus became an American catastrophe SEE TIMELINE]

By Monday, Trump had lurched away from his own administration’s messaging on the coronavirus, writing on Twitter, “WE CANNOT LET THE CURE BE WORSE THAN THE PROBLEM ITSELF” and insisting during a disjointed evening press conference that most people should soon go back to work in order to prevent economic damage—even though public- health experts warn that this would dramatically worsen the pandemic and cause a wave of preventable deaths.

The whiplash of the past few days is a vivid example of the Trump administration’s struggle to manage its first true crisis that was not generated by the president himself. The coronavirus has, in some ways, led to Trump erratically playing the part of a more normal president—at least sometimes. This isn’t because the mythical “pivot” toward presidential behavior—much heralded by political pundits—is finally upon us. (Indeed, Trump’s behavior on Monday shows that it very much isn’t.) It’s not because Trump is growing into the office. It’s because the nature of the crisis so restricts options that he is being forced, when he allows himself to be, onto a more traditional path.

Yet Trump’s extreme eccentricity has not gone away. It’s still there, constantly vying for supremacy—which is how bizarre ideas such as trading off continued economic activity in exchange for hundreds of thousands of lives make their way into the Oval Office. What’s more, when Trump isn’t spouting proposals for monstrous calculations such as this one, he is singularly lousy at playing the traditional, managerial president. The result is a weird kind of vacillation between the Trumpian presidency and the more traditional one.

This erratic and half-hearted reaction isn’t the response one might have expected from the Trump administration, with its belligerent assertions of executive power, when faced with a global pandemic. Civil libertarians have voiced concerns about the immense authority available to the president in combatting a public-health emergency. Writing in The Atlantic, Elizabeth Goitein recently noted that Trump’s declaration of an emergency regarding the coronavirus, though reasonable so far, could theoretically empower him to seize control of sources of communication such as radio stations and, possibly, the internet. After the president limited some travel from China in early February, the American Civil Liberties Union warned that it would be “watching closely to make sure that the government’s response is scientifically justified and no more intrusive on civil liberties than absolutely necessary”—hinting at the dangers of further interventions. And The Washington Post reported on privacy advocates worried by a potential program to provide the government with smartphone location data to combat the virus.

In light of the Trump administration’s track record of aggressive assertions of presidential power, such concerns aren’t misplaced. It’s not hard to imagine how an energetic president with authoritarian instincts might be able to turn this crisis to his advantage in carrying out a Trumpian policy agenda—sharply limiting travel across the country’s borders or even between states; placing blame for the virus on immigrants and nonwhite Americans to inflame popular sentiment in favor of further immigration restrictions; implementing an invasive surveillance regime in the name of public health, but one that could be kept in place indefinitely.

Yet the administration has been comparatively restrained in its response to the virus—in fact, if you ask most public-health experts, far too much so. Instead of springing into action with worrying zeal, Trump has waffled since the beginning. In January, he denied that the virus posed a problem at all, insisting that “we have it very well under control” and that “we pretty much shut it down coming from China.” By early March, he was still declaring that the pandemic would miraculously dissipate—not the language of a would-be dictator in search of a Reichstag fire to use as an excuse to consolidate power. Authoritarians tend to want to prolong emergencies, not deny their existence or wish them away.

Indeed, Trump’s actual assertions of power in response to the crisis have been so anemic that the law professor Steve Vladeck—speaking on The Lawfare Podcast recently—warned that the president’s underdeployment of national-emergency authorities might allow the virus to spread. Likewise, the president’s scheme to end social distancing and reopen the economy would hinge on rolling back what few measures the federal government has put in place, not exerting new authorities. The irony is that Trump actually has very little power to kick-start “opening up our country,” as he put it: Governor after governor has issued orders for state residents to shelter in place and for nonessential businesses to close, and the president has no ability to force the states to “open up.” In other words, his most aggressive proposal yet would probably involve him doing nothing.

The trouble for Trump is that once he acknowledges the premise that the virus is a real threat, there are only two paths for him to take—the two approaches between which he has bounced. The first is traditional presidential management. The federal government has genuine capacities. Wielding them requires a lot of work: untangling the actions of various agencies, ensuring that the government is working as quickly as possible, coordinating with states, and rallying the country. These are the things normal presidents do. And the nature of the crisis necessarily changes and narrows the choices before him, pushing Trump toward more managerial questions. He can get only so far with jingoistic baiting about the “Chinese virus” and actions at the border that map onto his preexisting worldview. Eventually, the options before him will turn out to be more technocratic: Is a hospital ship available to send to New York? What can the administration do to best help an economy shut down by people engaged in social distancing? Should the Army Corps of Engineers be deployed to construct hospitals? The big problem with this approach for Trump is that he’s bad at it. He plainly doesn’t enjoy it. Management is not his jam.

The second path is Trumpian magical thinking—the belief that the problem will go away as a function of Trump’s own personality and will. He has lapsed into this kind of thinking repeatedly throughout this crisis—in his denial of the problem, in his assertions that the problem will take care of itself, in his tossing off of theories about new therapeutic possibilities for treating the virus, and now in his promotion of the idea that sacrificing Americans to feed the economy will somehow make things better, instead of dramatically worse.

So the old Trump has not gone away. He still praises himself, attacks his critics, announces outcomes, harangues the press, eschews responsibility for anything that has gone wrong, and lies about his prior posture with respect to the crisis. He does these things daily, apparently still believing—as he once said on Fox News—that “the one that matters is me. I’m the only one that matters.”

But there’s a problem with this style of presidency too: It doesn’t work, because magic isn’t real. It can appear to work when the stock market is rising and the economy is humming along and it doesn’t matter that much what the government does. But when people are getting sick and losing their jobs in droves and the economy is in free fall—or when people return to work only to become gravely ill and spread the virus further—magical thinking is not going to cut it.

The result of this battle within the Trump White House has been an occasional glimpse of a more normal presidency—but one in which the normalcy is incompetent and grudging and occasional and consequently ineffective. The Trump administration has taken some of the steps that a more normal presidential administration might have taken to deal with the virus, but it has done so haltingly and weeks late. It’s trying to mobilize the federal government to deal with a national crisis, but without any apparent interest or insight into how the government actually works. This is how the country ends up with a president who trumpets the fact that he has invoked the Defense Production Act to assist in the manufacturing of ventilators and surgical masks, but who fails to take any action under the relevant executive order to actually trigger that surge in production. Trump is like a bad actor trying to play the role of a normal president—a role he hates and so misunderstands that he just can’t do it, and instead resorts to hamming it up onstage.

The result is a remarkable feat: Trump has stoked concerns about executive overreach and executive underreach simultaneously; he has at once promised everything and acknowledged accountability for nothing; and he has found that magic—so endlessly enticing as an alternative to failure when the cameras are rolling—doesn’t slow the spread of a pandemic. Backed into a real crisis, one that requires the steady hand of a more traditional president, Trump is suddenly finding that genuine governance is hard.

_____

QUINTA JURECIC is a contributing writer at The Atlantic and managing editor of Lawfare.

_____

BENJAMIN WITTES is a contributing writer at The Atlantic, the editor in chief of Lawfare and a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution.

*********

#u.s. news#trump administration#politics#president donald trump#politics and government#trumpism#republican politics#donald trump#us politics#Trump lies kill Americans#trump lies#trump is a liar#trump is evil#trump is unfit#Trump is a racist#covid 19#covid19#covid2020#covidー19#corona virüsü#corona virus#chinese coronavirus#world news

0 notes