#transphobia has an end goal of white supremacy

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

while i agree with the viewpoint that we shouldnt really be super focused on that fact that terfs misgendered a cis woman, i also agree with the viewpoint that the fact that white cis women were misgendering a black cis woman needs to be discussed because this is the endgoal of terf ideology.

they want to gatekeep womanhood so they can harass and exclude black women from their circles. that post also said that it's not a mistake that jrk misgendered a black woman but i do think that her cisgender identity needs to be discussed within the context of misogynoir and how transphobia is used to harass black women for no reason.

and we also have to talk about how the origins of queerphobia come from white supremacists because of the fact that they needed to demonize the cultures of the black people they were gunna enslave and their acceptance of queerness precolonialism is important in the discussion of the origins of tranphobia and how to prevent women from joining the terf ideology and acting like this.

#personal#transphobia has an end goal of white supremacy#we need to discuss the gender politics at play along with the race politics

1 note

·

View note

Note

hey, hope you are well!

i'm a beginner witch and one of my goals in witchcraft is to eventually do deity work.

i was wondering if you could give me any insight into the practice you may have and any things to look into on this path?

thanks so much!

So deity work is actually not an inherent part of witchcraft! Not all witches are religious, Pagan, or work with deities. I don’t. I just practice the craft, so unfortunately I don’t have a lot of insight on that front.

If you’re new I do have some general insight and things I think a new witch should keep in mind, things to watch out for, you get the idea. You were probably asking about deities but I'm gonna tell you these things anyways!

What I Think a New Witch Should Know

Bad ideologies - I'm not gonna sugarcoat this one. There's a lot of nazis and TERFs lurking around. New age stuff can be (almost always is) a pipeline to ideas that are based in white supremacy and anti semitism and I see a lot of people just ending up caught in the web of anti semitic conspiracy theories when they're into new age stuff. A lot of TERFs will say things like "we're the daughters of the witches you couldn't burn" or that only women are magical or can be witches. Now the concept of the divine feminine has been appropriated and is turning people into tradwives and TERFs and spreading bioessentialsm and basically just spreading transphobia and taking people down the alt right pipeline. I know I mention this is a lot but it's really important to me! Practice research skills. Consider where ideas come from and their history before internalizing them.

Each witch will have their own rules - I generally do not tolerate cultural appropriation and strongly encourage people to ward, so those are the closest things to rules that I preach, but at the end of the day there are no universal rules. If someone says "you have to/can't do this to be a witch" like 99% of the time they're full of shit. People who are BRAND new contact me with the same 10 misconceptions all the time. Be weary of people who say there are strict rules, they may just be preaching their beliefs as facts.

Safety & discernment - The other two kinda go over this already but this is just a general suggestion. Practice regular safety precautions and discernment! Discernment is asking things like is this suggestion safe for me? Where did this idea come from and what's its history? Or for your own practice, could this experience have a logical, not spiritual, explanation? This will keep you from falling for bad ideas and misinformation but also from burning yourself on candles, ingesting herbs you don't know anything about and rendering your medications ineffective, following essential oil advice that will give you a chemical burn, assuming that an experience is spiritual when it is not, and so much more!

Learn what you want - You wanna know what I think you should look into? Dogwhistles. Okay that was me being a little bit funny, we already talked about TERFs and watching out for them. While dogwhistles are a generally good to know I think as far as your witchcraft practice and research goes, you should learn whatever the hell you want. As I've mentioned in my pinned post, I have built my practice and beliefs from scratch and approach teaching with the same goals in mind for you. You wanna know what you should learn? I don't know. You tell me. If you want some general suggestions? Do actually learn dogwhistles. Learn about practices that are closed so you do not appropriate from them. Learn about warding and go outside and learn about the animals and plants around you! But as far as practices go, like tarot or spells or spirit work? Learn about the ones you think are neat.

Also if you wanna know about deity work, specifically working with the Greek pantheon or Aphrodite, I think @teawiththegods is pretty cool. She's nice. Ask him stuff!

I hope this helps ���

#witch#witches#witchraft#witch tip#witch tips#witchy tip#witchy tips#baby witch tip#new witch tip#baby witch tips#new witch tips#beginner witch#new witch#baby witch#what I think a new witch should know#misconceptions about witchcraft

158 notes

·

View notes

Note

If you are anti sex work, it is because you are anti sex.

This is such a succinct way to put it. Note the first SWERF to respond in this chain keeps talking about "rape" this and "rape" that, but their definition of rape is not universal! It is possible to have sex for reasons other than sexual attraction!

"My partner hasn't cum yet, so I'll keep going for their sake" ≠ rape.

"My partner has a cold, they feel and look like shit, but I know just what to tickle to cheer them up" ≠ rape.

"I want to bang my friend to find out what it feels like" ≠ rape.

"I think I'll pity-fuck my virgin friend, so I can make sure their first experience is a good one" ≠ rape.

"I'm working through complex emotions and I want to have casual sex with a stranger!" ≠ rape.

"I'll do a sex act I'm not particularly fond of because it brings my partner pleasure, and it's their birthday" ≠ rape.

"I'm negotiating the terms and engaging in kinky BDSM scenario" ≠ rape.

"I negotiate and perform specific sex acts, with specific people at a specific location, with the ability to stop at any time, in exchange for money“ ≠ rape!

See, sexual consent is more complex than just "coerced by dint of living under capitalism (or not)." It involves trust, transparency, and agency over your circumstances. In addition, sure there are people for whom sex is an extremely intimate, vulnerable, emotional act. And for some people sex is like Tuesday. Just because you personally might not feel comfortable performing sex for money doesn't mean other people can't.

But all this, this is to you, Anon, who is coming from a place of genuine curiosity and good faith. Radfems do not act from good faith, and I'm not trying to convince (or "debate") them. Radical feminism is a teleological agenda of biological essentialism; it holds no beliefs and makes no arguments except when it's convenient to claim to do so. That's why when you follow the thread of radfems' talking points, they are so often self-contradictory. And they don't care. At its core is nothing but transphobia and white supremacy, grounded in the idea that, in the words of user @kaumnyakte:

there are only two genders. the one that does bad things and the one that bad things are done to. the only thing in the world is immorality and it flows from unexperiencing agents to unacting experiencers. ... which naturally appeals to people who would like to be perceived as inherently lacking the capacity for immorality. for whatever reason (x)

That's why radfems lean so hard into the victim card. That's why they CLAIM to protect sex workers, who are all innocent helpless rape-experiencers... Until a sex worker actually speaks up and says, "Uh no, I enjoy my job, I like many of my clients, and criminalizing any aspect of my work would absolutely put me in more danger." Then SUDDENLY, that worker is a gender traitor, an evil brainwashed pawn of the patriarchy. Y'know, like how they view trans men.

Sorry this ended up being a #long post, but if you've ever wondered why radical feminism gets a bad rap, I hope this helped. The transphobia is inextricable from the rest of it, and any radfem that claims otherwise is lying to you. Their goal is to indoctrinate you, slowly and subtly, using the exact same techniques as neonazis and cults.

That is why we do not debate terfs, swerfs, or nazis. Punch them on sight, and block them on site.

Besides the anti-trans stuff, is it bad that I agree with a lot of what radfems say? Like for example, I think the porn industry is very evil and some people aren’t critical of it enough, as sites like PornHub facilitate trafficking and the existence of violent acted-out porn itself has awful affects on men and women alike for different reasons (though I wouldn’t blame any individual sex worker for this).

Radfems will sometimes say things that, on their face, make sense, but fall apart as soon as you start looking further into them. Their anti porn points are a good example. The porn industry is abusive. Performers are underpaid and taken advantage of both financially and sexually. Tube sites do make it way too easy for people to upload videos of csa or sexual assault, and there's evidence of this happening on many occasions. A lot of people (esp young men) do learn all the wrong lessons about sex from porn and develop an unhealthy relationship with sex because of it.

The issue is that radfems believe that these problems are inherent to porn, rather than the product of other societal forces. Performers are abused so frequently both because the institutions meant to protect victims of sexual assault and workplace abuse are woefully bad at serving their intended fuctions, and because these performers are not respected as workers to begin with. Despite how many people watch porn on a regular basis, performers are not viewed as "real" workers doing "real" work, because what they are doing is stigmatized by a misogynistic, puritanical society. People develop toxic attitudes about sex from watching porn because sex education doesn't teach you what is and isn't normal or pleasurable during sex and people do not communicate with their partners about what they actually want. The problems with porn do not exist because porn in and of itself is misogynistic, they exist because porn, like everything else in our society, is affected by patriarchy.

5K notes

·

View notes

Text

Since I seem to enjoy Starting Shit on the Internet today, I'm going to share some thoughts on the OnlyFans debacle.

First: sex work is real work. I said it, I believe it, that settles it.

It seems a lot of people (often young women, I've noticed?) are really celebrating OnlyFans banning all NSFW content. They’re having a great time saying things about how they hope all the (cis) men who liked NSFW OnlyFans content die mad about the NSFW ban and so on. It’s downright gleeful. And it seems like they're celebrating on the grounds of stopping trafficking and protecting minors and so on. And that's a noble thing, ending trafficking and protecting minors--do not misunderstand me: trafficking and abuse of minors is a real and serious issue and I absolutely support ending trafficking, rescuing victims, and protecting minors.

It is my opinion (insert Vine here) that OnlyFans banning NSFW content is going to hurt sex workers and also will do absolutely nothing to protect minors or stop trafficking.

A considerable number of people here in the US lost their jobs during the pandemic. And, among those people, are those who desperately need income. They're of age, they're legally allowed to do these things, and they need some way to survive. And, in the absence of a UBI or even a country that seems to care about the wellbeing of its own citizens, you have to find a way to survive. And a lot of the people who found themselves unemployed discovered that they could earn enough of an income through OnlyFans to actually survive. They could keep the lights on, get food, pay for medication, put gas in their car so they could drive to job interviews. It became a means of self-employment.

Are you thinking of the people on OnlyFans and elsewhere who are doing sex work as actual people? Or are they just a mass, just a concept, onto which you can project your ideals of Purity Culture? You’re giggling gleefully about unhappy men with blue balls, but I feel like you’re forgetting the women who are still stuck in a Capitalist situation.

"But they didn't start doing it willingly!" You can't prove that that's true for everyone on the site. You cannot prove that. You do not speak for everyone. Maybe some people turned to OnlyFans out of desperation, sure. But others may have felt relieved that they had it there. Others may have even felt liberated or enjoyed the work. I don't know. And you don't know either.

"But if you make sex work legal, that makes trafficking easier!" Yes, yes, I've seen the whole "Nordic System" argument. I've read it. My issue with it is that everyone is using it in the wrong way.

Remember when Oregon decriminalized possession of small amounts of most drugs? It was a decision made on the grounds of harm reduction. If you won’t get arrested for having some crack in your pocket, you can feel safer. Look at what the War on Drugs has accomplished: legal slavery and police brutality. It doesn’t work. And it’s an excellent experiment to try something else.

If sex work is declared protected or legal (and banks and credit cards cannot therefore refuse payment made to legal providers of the service), then any sex worker who is threatened, abused, harmed, attacked can make a report without fears of repercussions for doing sex work. Do you know how many sex workers are killed? If only there were some way to report a threat or a risk to the police without repercussions...

Beyond that: if someone is trafficked and they make a report about what's happening to them, it can be taken seriously because sex work is considered a legitimate area and trafficking would be very much outside the laws related to sex work. Same thing with minors in the same situation: it’s outside the laws, so it’s a crime, but someone reporting it would not be held as a criminal themselves. Collateral damage.

To go back to Oregon for a minute: if you decriminalize possession of small amounts of drugs, are you going to stop drug deals altogether? No. Oregon knows that too. But you can assist the people who do use drugs when they come forward with information about, say, murders connected to drug deals. And you can also provide a means for them to leave their situation if they so choose.

Yes, ACAB, but we can at least provide a measure of protection to people who need assistance. See how this works? If a sex worker knows about minors being abused or trafficking going on and they make a report about it, they themselves don't have to worry about getting caught up and charged for also being engaged in sex work.

More protection for more people.

Lastly, and this might make you mad, you can thank the US Conservatives for a lot of this.

It’s the good ol’ Moral Majority come back from the dead. Again.

Any time someone yells about pedophiles or trafficking, it gets everyone concerned--and rightly so. But the problem is that it immediately becomes "if you're not overtly against it, then you must be tacitly for it, so agree to this bill." And so, anyone who's progressive or vaguely left-leaning signs off on legislations or statements about how sex work is bad and sinful.

But in doing this one thing, the US Conservatives and especially the Conservative Evangelicals of the US, can then convince more and more people to sign off on a longer and longer list of laws or beliefs that the Conservative Evangelicals want to push through. That’s their goal: to push through their ideas of a Good and Wholesome Christian Nation, with all the white supremacy and misogyny and homophobia and transphobia that entails.

So you start off with the existing laws regarding sex work, then you start sliding into "all of these kinds of sex work are illegal" and then "all sex work is illegal" and then "all pornography of all kinds is banned" and then you start slipping into lawmaking like ending access to birth control (because that encourages casual sex) and ending the rights of LGBTQ people (because "perversion"). You've seen it before, you could see it again. (And yet we can't seem to get child marriage completely banned in the US. Funny how that works.)

I don't mean to "slippery slope" this stuff but, trust me, it seems bad now but it can get so much worse. And I hope it doesn’t get worse.

“If you’re a feminist, how can you be in favor of sex work?” Because sex work is work. And, if you look back through history, you’ll find that banning sex work and punishing sex workers didn’t make things better, it drove everything down deeper and made everything worse. Less safety, less security, more risk, more punishment.

It seems like a shallow version of feminism if all you’re doing is sneering at cis men and turning up your nose at sex workers. I think you ought to reexamine your beliefs.

9 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hey, I'm a white trans person, and I saw your post about how white people don't have to think about racism. Would it be inappropriate to compare it to transphobia/transmisogyny? I know they aren't like, the same, but I think they're similar in that I have to think about transphobia all the time, while cis people don't.

It's on a similar vein, yes! However, as you already correctly identified, these are somewhat similar things, but not at all the same. I'm way too tired to get into all the historical implications of racism in America and the manner in which our entire country is built on furthering and maintaining white supremacy. I would say this. Rather than comparing the two situations, or any types of opression, really, do this. Take the pieces of my post that sound familiar to you, that you see echoed in your experiences with oppression. Use those to further your understanding of the BIPOC experience in America, and know that there is so much nuance and history that will never be familiar to you, and that is okay. It's like if a white cis gay man was talking to me (I'm also trans btw) about how he understands exactly what I mean when I'm talking about my experience with race. I don't wanna hear that, because it's impossible, and reductive to the point of being offensive. My experience is so big and so deep and so varied that the only way to truly understand it is to have lived it, in the same way I don't understand what it is to be a white cis gay man. But if this same man told me that his experience as a gay man in America has given him enough perspective to understand and relate to some parts of my experience, that's fine. If he says that he's going to do his part in bringing those bad experiences to an end, that's solidarity. And that's the goal. We won't ever truly understand the experiences of those who deal with opression that we don't face. But we don't have to. We know enough to stand up for each other, and that's what we must do. I hope that all makes sense, and thank you for your question!

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

On Twitter, there’s a new movement that started up on... Thursday, I guess, with the hashtag #SpeakingOut, where women were encouraged to call out instances of sexual abuse. I’m not sure if it started with the pro wrestling community or not, because earlier in the week I saw some stuff about comic book pros like Warren Ellis and Cameron Stewart, but maybe that was a precursor. All I know is that right now, I’ve been seeing all sorts of names being dropped in the pro wrestling business, each of them accused of being sexual predators, or covering up for the crimes of others. Some of the names I don’t recognize, because they’re independent wrestlers from promotions I’m not familiar with, but I’ve seen some names I do know, and that’s pretty tough to take. I’m going to discuss this here.

Predictably, I’ve seen some backlash to #SpeakingOut, which reminds me of the same bullshit talking points used by the #IStandWithVic crowd last year. In case you didn’t know, Vic Mignogna was a voice actor who worked for Funimation and provided the dub performances for Broly in DBZ, and Eward Elric in Fullmetal Alchemist. I think those were his two most famous roles. Over the decades, Vic garnered a reputation for being a sex pest, kissing and inappropriately touching women and teenage girls at conventions, and harassing his colleagues. I assume the release of the “Dragon Ball Super: Broly” movie in the U.S. in 2019 precipitated a newfound interest in those allegations, and fans started objecting to his bookings at 2019 conventions. By mid-year, Vic was fired from Funimation and RoosterTeeth, and he responded to this by starting an ill-advised defamation lawsuit.

Vic’s defenders are, to put it mildly, idiots. There were professional lawyers on Twitter who explained, very clearly, why this lawsuit was a bad idea. The main reason being that it was done in Texas, which has a lot of laws designed to make it harder to sue people for defamation. I think Vic’s goal was to find some way to punish his accusers for making him look bad and getting him fired. Winning the lawsuit, was a way for him and his supporters to feel like they “cleared his name”, except that was never how it worked. If he had been arrested and tried for sex pest crimes, the burden of proof would be on his accusers to show that he really did bad things. But he was suing people for slander, so that means the burden of proof was on him to show that they really were saying things that were demonstrably false and damaging to his reputation. The main problem with that is everyone had been talking about his sex pestery for years, so it doesn’t make sense to single a few people out in 2019 and blame them for reinforcing something everyone already believed. But the ISWV crowd kept insisting that this distinction didn’t matter, and that it was wrong to ostracize or turn against Vic without “proof”. I see the same demands for “proof” being tossed around for all these wrestling personalities.

I think there’s a couple of things going on with this. One is simple denial. If you’re a fan of someone and you find out they did something terrible, you really don’t want to believe it. I was never that into a lot of these guys, but I know I felt pretty low when I first heard about Vic’s shenanigans, because I liked his work. And I’m feeling that way about Warren Ellis now. Not a huge fan, but I liked some of his stuff, and now I feel a little guilty by association for ever liking that stuff in the first place. It would be nice, I suppose, to just pretend that I hadn’t heard those accusations, or that they weren’t real. Then I could just go back to the way things were before, without all the uncomfortableness. I just can’t do that, but it seems like a lot of people can and will. It’s not about “proof”, it’s about putting up some sort of barrier that will excuse them from confronting an unpleasant truth.

I think this is why you see people going out of their way to defend Christopher Columbus and Confederate monuments. They want to believe that there was something noble about that stuff, because the alternative is to admit that a lot of the things they learned in school aren’t true, and a lot of the “heritage” they cling to is built on white supremacy and slavery. I don’t think anyone really cares about a Robert E. Lee statue, but I’ve seen people go out of their way to try to say Lee opposed slavery, like he’s one of the good Confederates, so he should get a pass. Except he did own slaves, and even if he hadn’t, he still fought to defend a nation founded on slavery as a guiding principle. Tearing down a statue of Lee is a tacit admission that Lee never deserved a statue in the first place, and everyone who admired him was wrong, and maybe the admiration was rooted in racism all along. That’s a bitter pill for people to swallow, and a lot of them just refuse to swallow it. So they deny and deflect, and do anything they can to make this about something else.

The other side of it is just plain hatred. I don’t know if Vic’s defenders were all misogynists to begin with, but it seems like they all got there, one way or another. The train of thought always seemed to be “He didn’t do these things, but even if he did there’s nothing wrong with it.” From what I saw, it really seemed like Vic’s backers were all fired up about defending a man’s right to creep on women in any way he sees fit. “What, so kissing is illegal now?” No, jackass, but when you’re fifty-fucking-five and you kiss a seventeen-year-old girl who only wanted to take a picture with you, it’s pretty damn messed up. When you use your celebrity status to try to mack on young fans, that’s messed up. When you’re an established wrestler and you try to take advantage of up-and-coming wrestlers, that’s messed up. And some of that behavior is totally illegal, but the sad reality is that most of these creeps will never get prosecuted for any of it. That’s why the calls for “proof” are so hollow, because everyone knows it’ll never end up in a courtroom. At best, some of these guys will get fired, and guess what? “Innocent until proven guilty” doesn’t apply to employers. I lost a job once because my “teamwork” wasn’t good enough, and that was the closest thing to an explanation I got. Don’t bullshit me about “proof”.

I guess I should tie this train of thought in with Black Lives Matter while I’m at it. I find it absurd that the police in this country are so out of touch that when there’s a nationwide protest against police brutality, their immediate response is... more brutality. This, more than anything I’ve seen, is the reason to defund the police. They appear to only have the one mode of conduct, and they don’t even know how to do things a different way. If the situation is this bad, we may as well scrap the police as they are and start over. If the cops wanted to fix this situation, all they have to do is treat people with respect and hold themselves accountable, but they can’t let go of their hatred for five fucking minutes and figure that out. This is why you hear about those guys who make up stories about restaurants spitting in their food. They’re paranoid that everyone’s out to get them because they know they deserve to face some consequences, so they’re constantly on guard for this sort of thing. It’s sick.

Somehow, people who support these guys end up supporting the very behavior they were supposed to be denying. Maybe this is why Columbus is such a sticking point. I never gave a shit about Columbus. One of my high school yearbooks had a Columbus theme because it just happened to come out on the 500th anniversary of his first voyage to North America, but I never understood what that had to do with my high school. I think there’s people that want to give him tons of credit, basically thank him for everything that’s happened in the Western Hemisphere since 1500, not in spite of his atrocities, but to retroactively justify them. What I mean is, if you can convince society that Columbus was a great man, and that his achievements outweigh his wrongdoing, then you can also convince society that the wrongdoings aren’t actually that bad. “The price of progress,” they can say. It’s like the idea that Robert E. Lee is admired solely for his “brilliant” military mind. His side lost the fucking war, so I never understood how he gets all this credit for being a great general. The point is that if you can convince people that he was a noble man in spite of the slavery thing, then you can open the door to the idea that the Confederacy as a whole wasn’t That Bad, and that only opens the door to the idea that slavery wasn’t That Bad, and so on.

Same deal with Roman Polansky and Woody Allen. It amazes me that people will still try to defend those fucks, but it probably has a lot to do with all the other sex pests in Hollywood, who hope that everyone will stick up for them when they get exposed. So you have this little chesnut about how “Yeah, they did bad things, but they sure made some good movies.” The implication is that you have to accept a few sex crimes if you want good art. And no, that’s not true, and even if it were true, it wouldn’t be worth it.

I don’t know where things will end up with J.K. Rowling. I’d like to think that one of these days, she’ll wake up and apologize for all this TERF rhetoric she’s been spouting. That would probably be the best-case scenario. More likely, she’ll cause an entire generation of Harry Potter fans to wrestle with their loyalty to her books. There’s no job to fire her from, no laws to punish her, no government agency to step in. She’s got no financial stake in repairing this PR damage. There’s going to be an audience of bigots that will still kiss up to her no matter what she says, so her ego will be well-insulated. Maybe a hundred years from now, people will be talking about tossing her statue in a river, as society admits that we don’t need to accept transphobia in exchange for YA literature.

I don’t know, I think I went all over the place with this one, but I had a lot to get off my chest. I think the overall lesson from this year is that we can’t put these people on pedestals. Some of them are just hell-bent on letting us down, and it’s just a matter of time before their misdeeds are brought to light. I see these dopes with Thin Blue Line flags and “I stand with [X]” hashtags and I’m like “Who are you supporting here? What is it you’re standing for, exactly? Why should they be worthy of your loyalty?” And I think the answer is less about loyalty to a person or group, and more about sticking it to someone else. Women, minorities, whoever. They just want to stand by someone to spite someone else. And that’s awful.

9 notes

·

View notes

Photo

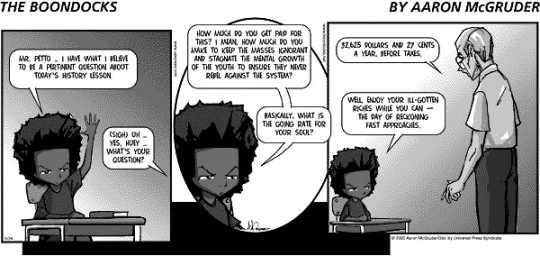

Questioning the Questioning of Authority

Having now lived in Eugene, Oregon for over twenty years, I’ve long dreamed of parking next to a car with a “Question Authority” bumper sticker and asking the driver: “By what authority do you tell others to question authority?” The resulting conversation would, without doubt, be interesting; with any luck, it might also be civil.

The slogan, quite popular in university cities such as Eugene, was apparently made popular by the notorious psychologist and LSD proponent Timothy Leary, and it certainly reflects the mentality of “the Sixties,” which sought to question, reject, or even attack any and all authority: political, social, academic, and religious. But, actually, it wasn’t opposed to all authority because, of course, it assumes some sort of authority on the part of the person proclaiming the slogan.

The key word here is “assumes,” for when it comes to personal autonomy and authority, most people makes significant assumptions. The recent conflicts between racist groups and Antifa (or “anti-fascist”) groups is a good, if depressing, example. The rhetoric of both is filled with strong assumptions about authority.

For example, one Antifa website states, “We don’t rely on the cops or courts to do our work for us. This doesn’t mean we never go to court, but the cops uphold white supremacy and the status quo. They attack us and everyone who resists oppression. We must rely on ourselves to protect ourselves and stop the fascists.”

This, without doubt, is all about authority: who has it, whose authority is legitimate, how authority should be handled. The site further outlines the Antifa desire to “to build a broad, strong movement of oppressed people centered on the working class against racism, sexism, nativism, anti-Semitism, Islamophobia, homophobia, transphobia, and discrimination against the disabled, the oldest, the youngest, and the most oppressed people.” This includes supporting “abortion rights and reproductive freedom.” And what is the ultimate goal? “A classless, free society.”

Never mind that such a stance never could actually result in a “classless, free society,” for the simple reason that the claim to authority immediately and logically creates a class—that is, those with supposed moral and political authority—and also raises the question of what “freedom” is like in such a society. (I think Islam is a serious concern and I believe homosexual acts are immoral; would I be free to say so? It doesn’t sound like it.) Who decides what “freedom” involves? And, to go even deeper, how does the Antifa movement decide what is “oppression” and “discrimination”? Is not the killing of unborn babies a form of oppression? As is almost always the case, such idealistic movements are heavy on passion and light on philosophical substance.

Every philosophy, institution, movement, and belief system relies upon some sort of authority. The Catholic apologist, in considering the claims of, say, an atheist or the Watch Tower Society or a Protestant, should always examine the assumptions made about authority. This is one reason I left Evangelicalism and became Catholic: I realized that the claims to authority made by the Catholic Church had a logic and substance not found in the Protestant tradition, whose claims to authority had serious defects.

A wonderful guide in this regard was Monsignor Ronald Knox (1888-1957). The son of the Anglican bishop of Manchester, Knox became Catholic as a young man and went on to write a wide range of books and even translated the entire Bible. In his classic 1927 apologetic work, The Belief of Catholics, he addressed the growing skepticism in England about the claims of Christianity and certain arguments made against the Catholic Church by various Protestants. One of the latter is the faulty claim that a Christian is not dependent, whether historically or practically, upon the Catholic Church for correct doctrine—all a believer needs is the Bible. In the chapter titled “Where Protestantism Goes Wrong,” Knox demonstrated that how one views the Church will either make or break the basis of one’s view of Christ, the Bible and, yes, authority:

[A] proper notion of the Church is a necessary stage before we argue from the authority of Christ to any other theological doctrine whatever. The infallibility of the Church is, for us, the true induction from which all our theological conclusions are derived. The Protestant, stopping short of it, has to rest content with an induction of the false kind; and the vice of that false kind of induction is that all its conclusions are already contained in its premises. Perhaps formal logic is out of date; let me restate the point otherwise. We derive from our apprehension of the living Christ the apprehension of a living Church; it is from that living Church that we take our guidance. Protestantism claims to take its guidance immediately from the living Christ. But what is the guidance he gives us, and where are we to find it?

The claim of many Christians that it is the Bible that fully guides them and provides the authoritative say in matters of their faith is inconsistent; it cannot stand in the face of reason, as Knox explained with brilliant lucidity:

In fact … the Protestant had no conceivable right to base any arguments on the inspiration of the Bible, for the inspiration of the Bible was a doctrine which had been believed, before the Reformation, on the mere authority of the Church; it rested on exactly the same basis as the doctrine of Transubstantiation. Protestantism repudiated Transubstantiation, and in doing so repudiated the authority of the Church; and then, without a shred of logic, calmly went on believing in the inspiration of the Bible, as if nothing had happened! Did they suppose that Biblical inspiration was a self-evident fact, like the axioms of Euclid?

Not only does the Bible itself not teach that it is the final and sole authority in the Christian life, such a belief ignores the historical facts about how we received the Bible and by whose authority the canon of Scripture has been set. The Catholic faith, in sum, is a seamless garment demanding “all or nothing”; if someone accepts the authority of Scripture, it is logical that he, like Ronald Knox, must also accept the authority of the Catholic Church—it is both necessary and consistent. So, yes, feel free to question authority, but be sure to tease out the logic of your questions to their very end.

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

get out: black educator edition (new orleans schools)

by a black educator in new orleans | pen name barbara jean wells

The 2015-2016 school year was easily the most traumatic work year of my adult life. I was a teacher at an alternative high school in New Orleans, a job very similar to one I left in Philadelphia. Alternative schools are intended to address the pushout crisis by creating spaces for students who have not found success in traditional schooling environments. Sometimes this is simply because they need a smaller environment than those provided by traditional schools. Sometimes it’s because they are the kids who have dropped out or been pushed out of the charters that claim to be educating ALL of our kids. Sometimes they are kids in the justice system, or young parents caring for children of their own. The possibilities are endless. It’s a population that I am very comfortable with, having worked in alternative education for a few years and also one that I care deeply about because of the unique challenges and struggles that come with serving youth.

Despite my passion for, and comfort with, alternative education, last year led me to question the very foundation that I had built my career as an educator on. I cried a lot, emoted on facebook, journaled during professional development meetings, frequented happy hours with other educator-friends and soaked it all away over margaritas paired with chips, and salsa (yes, we’ll need another pitcher). I worked out for self-care, got a therapist to maintain balance, and dug into my yoga practice to begin meditating regularly. I did the usual things one does when they’ve got a stressful job.

When those folks are teachers, all of the above are done with student stories sprinkled in between. Exasperating, funny, touching, and annoying moments with kids that make the job everything that it is. But when my coworkers and I went out to vent about a stressful day, the kids weren't the main topic of conversation. We talked about them, sure, but much more of our dialogue was spent on how racism played out in the daily grind of our work as educators. We vented about administrators whose savior complexes were evident in the very way they spoke to and about students. We talked about how meager the expectations were of our low-income, predominately Black kids. We talked about the lack of ability for our white coworkers to even acknowledge the life differences between themselves and their students, so great was their desire to be colorblind. And more than anything, we talked about how the behaviors that spawned from these beliefs about Black kids and the communities they came from indicated the same age-old (and, well… racist) idea that our students should not be expected to excel.

What I realized halfway through this school year was that my desire to center Blackness in the classroom, to help my students unlearn most of the things that the media told them about themselves, still had to be done within a racist system. Perhaps this isn’t shocking to folks of color who are teachers, but after 9 years in the profession, the realization hit me like a ton of bricks. The progress I felt like I was making in the classroom with my students was directly counteracted frequently by other staff members in the building: those who looked down on them, made wild assumptions about their lives based on stereotypical views of Black communities, and centered conversations about the kids on their academic deficits more than anything else.

So what exactly did this look like on a day-to-day basis?

Extreme white saviorism

For starters, the level of white saviorism was intense. In this alternative school setting it translated to exceedingly low expectations of students and their futures. In one staff meeting, a white teacher claimed that it was actually a great thing if students ended up working at local grocery stores after graduating because at least, “they weren’t in the streets shooting each other up.” Others nodded along in agreement.

The idea that they were essentially “saving” kids from themselves and the communities around them drove some staff members to befriend kids rather than encourage their academic or personal development. One white teacher whose actions were particularly infuriating, let’s call him Mr. Frank, taught special education students who struggled behaviorally and academically. In this setting, it meant his class was full of the Black boys who could not sit still. Students dubbed it the place you go to “listen to music and eat snacks.” In meetings, Mr. Frank spoke openly and often about all the academic tasks he felt like students were incapable of even trying. These ideas help to explain some of the trash that passed for rigor in his classroom. He let students print Wikipedia pages and paste them to trifolds for final project work. He excused them from completing assignments and rarely failed kids regardless of what their effort or attendance looked like. Instead of encouraging academic growth in any meaningful way, he took kids to the store, bought them food, and handed out money. Let’s pause here, because many of these things sound incredibly sweet when done by a family member or friend. And yes, relationships are super important when teaching. But building them isn’t the ONLY part of teaching. As educators we focus on building relationships with kids in order to better TEACH them. To do this we have to actually believe in their intellectual capabilities enough to push for their academic growth. Mr. Frank didn’t see the second part of the equation as important though. He thought so little of the kids’ intelligence that there was no urgency in actually teaching them. He was there to be nice to them. To call them his “boys.” To make friends.

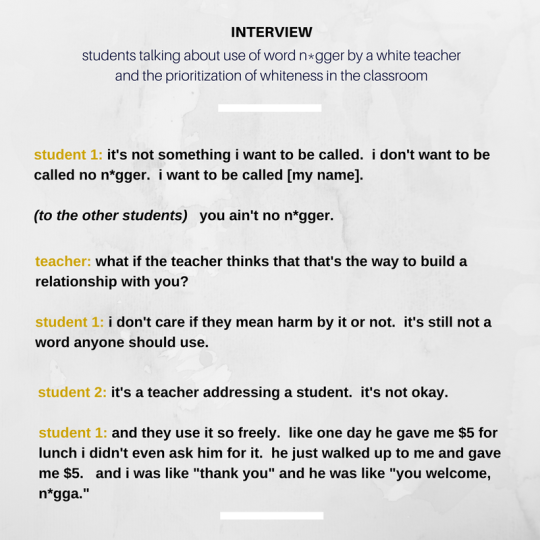

Mr. Frank’s existence as a 60-something year old white man didn’t stop him from greeting Black kids as the n-word and jokingly calling a young woman a “ratchet ass bitch” in front of a group of males in order to get a laugh from them. In previous years before I had arrived to the school, Mr. Frank had a co-teacher who was a gay trans man. When students in his class had been verbally assaulting, and in one instance physically taunting the co-teacher, Mr. Frank simply ignored the situation. He claimed his co-teacher needed to make better relationships with the kids, instead of using the teachable moment to encourage students to confront their blatant homophobia and transphobia. It would not have been easy. But actual, true teaching never is.

Over the course of my year there, it became clear that Mr. Frank’s class was a fun holding cell. Its sole purpose was to have somewhere to put kids. And with the low expectations and easy grades, it wasn’t difficult to see how the desire to be a savior to his idea of poor, broken, Black kids translated to the goal of befriending his students rather than teaching them.

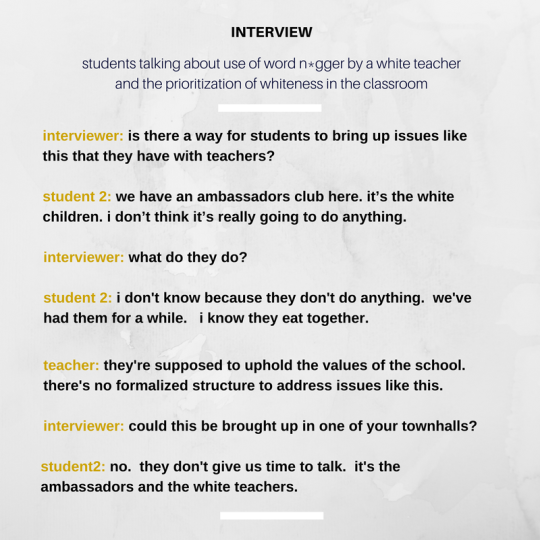

the following is a snapshot of interviews with teachers and students about their experience.

The privileging of white voice/ opinion

Outside of Mr. Frank’s outrageous everyday actions, another obvious indicator of racism in our workplace was the constant approval of white opinion and the subsequent shutting down of voices of color. One white teacher who was covering a Black educator’s classroom told students that their definition of racism, one that recognizes that all whites receive benefits and privileges from systems of white supremacy, was wrong because it made white people uncomfortable. He justified his assertion by coolly stating that he could speak to the issue because his partner was mixed race.

Over the course of the year, several teachers of color had complained about Mr. Frank’s behavior, specifically about their discomfort with him using the n-word and how his decision to do so made the workplace feel unsafe. They were told several times, “He has his methods.” Early in the year, a young Black woman was hired as his co-teacher but didn’t last in his classroom a month before needing to be placed with another educator. She expressed to me that he often seemed unprepared to teach and when she asked for lesson plans or outlines, she was scolded. He told her, “You don’t ask questions. I’ve been doing this for years. I’m the surgeon, you’re the assistant.” When she went to the principal with complaints of being treated condescendingly, she was reprimanded for causing trouble and made to sign a contract stating that she would never discuss Mr. Frank with other teachers while on the school premises.

Later in the year, when I tried to organize a meeting with a few teachers of color to talk about how best to deal with a white man calling Black kids the N-word, and brainstorm coping strategies for the growing list of racial microaggressions at work, I was called into the principal’s office for a meeting with her and the dean. Some folks suspected that someone had ratted me out and brought the principal the information. Others insisted that she regularly read staff emails. Either way, in the meeting I was made to apologize for my unprofessional behavior, despite the fact that I had previously addressed the principal with my concerns and was dismissed without any promise of further action.

All these instances taught an easy lesson. Other teachers of color and I quickly learned that if you had issues with how white teachers treated you, you kept your mouth shut. If you questioned how certain practices and behaviors were impacting students of color, you kept your mouth shut. And if you wanted to address issues of microgressions that made the workplace toxic, you didn’t discuss it at work in hopes of bringing about change. You went to happy hour with people you trusted and cried.

Valuing Intention over Impact

One of the major things that became apparent to me during my time at this school was how heavily white people who made the workspace uncomfortable leaned on their good intentions. Because everyone meant well, because everyone could couch their behaviors in the altruistic deed of educating Black kids with huge academic gaps, they did not seem to mind if their actions had negative impacts on coworkers of color or even the Black children they were supposed to be serving. When I realized this about my boss and coworkers, I began to see how strongly whiteness seeks to protect itself in schools. Everything from Mr. Frank’s “methods,” to teachers doing work for students they didn’t deem capable, to oft-expressed colorblind sentiments that white teachers used to make connections between themselves and the kids, were excused and never questioned because the people who did or said them “meant well.” It didn’t matter what impact this had on the kids and it sure as hell didn’t matter how it made staff members of color in the school feel.

It was around this time that I began to draw connections between law enforcement and education systems in this country. I knew from the many instances of cops who got off for murdering unarmed Black men and women, that whiteness in their institution also tended to protect itself. And much like with law enforcement, the issues that exist in education aren’t addressed as system-wide problems indicative of attitudes and biases towards people of color. Instead we discuss the few bad apples. In the education field, this means the teachers who DON’T care at all. They are essentially, the teachers with ill intent.

The problem with this approach is that most all white folks, teachers and otherwise, never see themselves as bad apples. They know that they mean well so they assume that they couldn’t possibly be a part of the problem. At this alternative school, the white folks who caused a great deal of the microaggressions could barely hear us decrying their actions and language. I imagine because our complaints were drowned out by the sound of them patting themselves on their backs every day for their hard work.

Recently, I read a headline that announced that percentages of Black teachers in the classroom have fallen drastically in the past few years. I didn’t bother reading the article because I felt like the wounds from last year were a little too raw for me to willingly subject myself to stories about why others like me may have been driven off. Halfway through the year when I was processing the notion of the education system being corrupt and failing to serve Black and Brown students, I posted a rant on Facebook. In it, I reflected on nearly 9 years in the education field and the experiences it took to get there. I specifically recalled going to grad school with people who made sweeping generalizations about Black/ Brown communities and consequently stereotyped their students as well. I remember smoking cigarettes after classes with fellow students of color lamenting the fact that some of the people in our Ivy League program were already in positions of power in schools full of Black children. I remember how proud they seemed of themselves for taking on the work of “fixing“ kids and schools, despite the lack of desire to fix their own racist viewpoints, language, approaches, etc.

Like last year, I brushed it all off over happy hours. I was still hopeful then. I thought that I could teach Black and Brown youth in a way that centered them, their stories, their beauty, and their lives. I did not consider that those grad school classmates who thought so little of us, and that people who shared their ideas, were already running the system and starting the charter schools. I did not consider that fighting for my kids essentially meant fighting against these people. It was a battle I was unprepared for when I first started teaching in 2007. It is a battle I expect to fight for the rest of my life. Though the new hope is to one day do it within an institution that is willing to take on the fight with me. This would save me from a career of holding my tongue until I get to half-priced drinks with other teachers of color who have learned that silence is the only way to stay in the ring.

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

7 layer burrito review

This is probably the closest taco bell comes to a hip modern burrito joint type burrito, rather than meat and cheese tubes. It’s also one of the oldest vegetarian items on the menu, somehow ostensibly healthy, as my mom would urge me to eat it instead of a bean and cheese tube. As an adult though I can tell you sour cream and guac are not actually all that much healthier for you than beans and cheese. This burrito is delicious, though. Yer mileage may depend on how much you like guac, but dang if this whole flavor profile doesn’t come together real well. It’s an underrated mainstay of the regular menu of Taco Bell.

I’ve been reading stuff by people “on the left side of the spectrum” who decry “SJWs” for being too crazy/out there/too far left. The folks saying this are generally trying to be sort of in that reasonable center position because going further left looks too tenuous and liable to lose you friends amongst people who are not also that far left. (because at the end of the day personal politics are more about what kind of social acceptance you want from which peers rather than anything like “principle” or an actual reasoned belief in how the world should be) A lot of the time when you interact with these folks they’ll delegitimize your social justice arguments as shrill. They’ll point out the hypocrisy in decrying child labor on an iPhone (which is irrelevant to whether or not child labor is bad or good). They’ll just flatly contradict statistics or demand and ignore evidence or try and deflect criticism by claiming their statements weren’t serious. Anything at all to avoid facing the criticisms head-on through argumentation or consideration.

And why would they? Most folks aren’t equipped with a strong critical thinking skillset. They’re not in the habit of rationally examining any part of their lives, let alone political statements. This isn’t a weakness in their ability or morality, at the end of the day rationality is wildly overrated and basically unnecessary to function as a human being. Most of the ideologies based around idolizing rationality only do so from the basis of the glamor that has inexplicably accrued to nerd-dom.

(It’s not actually inexplicable and has a lot to do with the development of new and very profitable technologies creating an advantage for the white men who helped enriched the old money folks who hired them, creating a feedback loop where these dudes have the most disposable income and thus cultural production geared toward them is advantaged, mostly in the form of heroic or power narratives that glamorize being a white male nerd throughout the 80s and 90s and 00s and 10s)

Actual rationality is scarce, unnecessary, and uncool (robotic, ahuman, unempathetic, cold, cruel, callous, etc) in most contexts. Is this a weird idea? I think it’s definitely something to consider. We live in a world where it’s basically impossible to change other people’s minds through rational debate and because we glamorize rationality this is treated as a sort of tragedy. The douchebag who runs the Oatmeal just did a really long comic about it. But like, think about the premise of these sort of sentiments. Rationality is good and awesome and separates us from the animals and lets us build jetplanes and basically a lot of these things are coterminous with “Science” as an idea. But at the end of the day think about it. What is the actual use value of rationality? Do you really need it in your day to day life, building arguments and justifications for why you eat or sleep or poop at any given moment? Do you need to be rational to gain power or influence in society? If we are living in a society built by irrational people using irrational means to gain power, what good is rationality? And if it is not that useful, why would people use it? They do not.

But that’s a little far afield here, back to the SJW thing. A lot of that comes back to folks not wanting to address the enormity of white supremacy or the relentlessness of transphobia. It’s not the arguments that scare them as much as the fundamental change that would be necessary to address them. The complete upheaval of their society and their worldview. More often than not a redress of their character, of their social habits, of their aspirations and goals and fears. A complete destruction of their present identity as beneficiaries of interlocking systems of oppression. It’s not a small thing, and it’s not an easy thing. I believe, and many others believe, it’s the Right thing to do.

At the end of the day, though, the personal benefit of maintaining a status quo outweighs conforming to an external moral code that causes literal self-harm, at least until we can create the social conditions where it’s more advantageous to follow that moral code than not. No amount of pointing out how fucked up of an individual you are for failing to give a shit about those around you will actually make you give a shit about those around you, that’s just something you have to come to in your life. A friend of mine accused me of being nihilist because I have a pretty bleak outlook on this, but honestly I don’t believe in free will and I think worrying too hard over vast systems in which you have no agency does no benefit to yourself. My advice is as always, love your friends and enemies and love yourself. Do what feels right to you. Express yourself completely. You might be a horrible person. I might be a horrible person. It happens. We’ll all be dead soon, and forgotten soon after that. That’s rationality with a little bit of sentiment mixed in. Awful, right?

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Because Black people don't exist as a monolith, relationships with each other are mostly defined by common experiences. Arguably, no communities within the Black diaspora have exhibited animosity between themselves than Africans and African Americans. To understand the friction between these communities is to closely examine white supremacy as a culprit. White supremacy is a system, or power structure, established to prioritise the feelings, interests, care, attention, and prosperity of White people even at the expense of other racial groups.

Its role in colonisation, violent capture and forceful removal of native Africans from their homelands is well documented. In truth, a significant number of African Americans today would have remained in Africa were it not for the disruptive event of the transatlantic slave trade. And although this has since been abolished, it has left internalised racism as a by-product for Black people to grapple with. To stay in context, Black Americans and Africans.

Source Of Tensions

African immigrants in America not only have to navigate systemic racism, but also microaggressions within African American spaces. But the migration regime that has enabled Africans to arrive in America to seek education, economic opportunities and others was made possible by the Civil Rights movement.

''I don't think this represents how all Black Americans think but I think the reason for this tension between Africans is that some Black Americans feel African immigrants come to America to take away opportunities,'' says Chanel Johnson, a Black American residing in Baltimore, Maryland, ''We are talking about opportunities in colleges that award scholarships and other educational or welfare packages to Black immigrants to thrive. We are also talking about opportunities away from academia. I also think dealing with racism and discrimination as Black Americans is pushing some of us to see how we are neglected and impoverished by the system.''

Although the friction between Black Americans and Africans predates social media popularity, a platform like Clubhouse for instance, is showing how this discord is ever-present. The voice-only app launched last year to massive reception, allowing for real-time conversations. Along the line it has produced xenophobic attitudes, misogyny, racism, homophobia, transphobia and antisemitism. Black Americans and Africans are no different when it comes to propping up long-held sentiments against each other.

''This in-fighting is such a regular theme on Clubhouse that whenever I enter the app and see no room with an inflammatory title targeting Africans or Black Americans, I always think something is wrong,'' shares Nigeria-based Tracy Imafidon. ''I have been in a room where a Black American man was openly xenophobic towards Nigerians and said we always cause problems wherever we go, even in America. On the contrary, Nigerians are doing well for themselves in America and becoming successful, whether it is school or work. And maybe this is what is eating Black Americans up? On the other side, I have also witnessed Nigerians and Africans be rude and uncouth towards Black Americans, using police brutality against them.''

Before Clubhouse, these kinds of interactions existed on Instagram, Facebook and Twitter. Interestingly enough, anything can act as a trigger. The cultural meltdown around the release of Beyoncé's Black Is King visual album last year, where Africans criticized it for flattening various African experiences pitted them against Black Americans. Or even this tweet that proclaims Black American culture as the blueprint for other Black cultures.

Common Struggles Much?

Despite the differences in realities that Black groups have, the news cycle has shown how Black people around the world and their political struggles are intersecting across white supremacy, imperialism and capitalist exploitation. The establishment of the police system during colonialism and slavery was primarily to subjugate people and protect capitalist interests. With anti-police brutality movements like Black America's #BlackLivesMatter and Nigeria's #ENDSARS, Black people are finding commonalities in their struggles.

Chris Edeh, a Nigerian-American currently residing in the UK, is more curious about solutions. ''What I have noticed about these divisions is that you don't actively need White people to divide Black people. We as Black people have internalized what white people have said about us and we use it against each other, and this is why we should embrace Pan-Africanism and read the works of Pan-Africanist thinkers. This doesn't mean we should ignore our differences. There are different groups of White people, but history shows how they had one thing in mind — capitalist expansion and accumulation of wealth via slavery and colonization. Likewise, Black people need to be united for the goal of liberation. I'm talking about having a Pan-African consciousness.''

Not all Black people subscribe to Pan-Africanism, an anti-slavery and anti-colonisation movement formed in the 19th Century and built on the premise that people of African descent should be in solidarity to achieve common goals. And while Pan-Africanism pushed for the liberation of Africans and those in the diaspora, the era of independence installed African dictators who once espoused Pan-African ideas but still went ahead and oppressed their own people. It's also why Pan-Africanism failed to deliver socio-economic prosperity for Africans.

''I don't believe in Pan-Africanism as the approach to address issues within Black communities,'' argues Joan Agyapong, a Ghanaian feminist living in Accra. She adds: ''Africa itself is too polarized and there's also the need for the continent to decolonise or break away from colonial notions that have been instilled in us. What I will recommend for individual Black communities is to continue to build enough political and revolutionary power to combat its issues on small levels. And you know what? It's already happening. We all in Ghana admired the END SARS movement in Nigeria and what it sought to achieve. I think it's rather lazy to suggest Black universality as a revolutionary praxis when today's Black realities contain more nuance than before.''

The existing tensions between Africans and Black Americans can also be seen through the lens of American exceptionalism and imperialism. America as a global power wields much cultural and political clout that it provides a ready infrastructure for Black Americans to be hyper-visible than other Black groups. Unwittingly, their experiences and culture is framed as a kind of 'superior Blackness,' filtering into their interactions with others on the Black spectrum. At least, mutual respect and understanding are necessary for Black Americans and Africans to co-exist courteously.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

#RadThursdays Roundup 06/15/2017

A frowning child holds up a postcard that reads, "White supremacy is killing me". Source.

Issues

Fighting Words: "On May 26, 2017, white supremacist Jeremy Christian allegedly murdered two men and maimed another as they attempted to defend two women he took to be Muslim from his abuse on Portland public transit. Days later, appearing in court, Christian roared out the same refrain that conservatives and far-right agitators alike have been repeating online for years: Racist violence is free speech. 'Get out if you don’t like free speech,' he howled. 'You call it terrorism, I call it patriotism. You hear me? Die.' Words have consequences. What was surprising was not how precisely a bloodthirsty criminal can echo the language employed both on racist reddit forums and by milquetoast liberal commentators wondering whether left-wing student activists aren’t the real fascists after all. What was surprising was that anyone at all was surprised. Where did you think this was going to end? When you start telling people that standing up for racism and bigotry makes them brave free speech defenders, they’re going to believe you, and they’re going to act on it. Two men are dead in Portland, and their murderer believes himself a hero. Internet, take a good look at your boy."

Three Thoughts on Emotional Labour: "Acknowledging the ways that emotional labour goes unseen and uncredited is important. We need to name the exploitation and devaluation of this important work. At the same time, the acknowledgement that emotional labour is frequently exploited has translated into a belief that emotional labour is inherently exploitative. As a femme who frequently performs emotional labour, both in my personal and professional life, I do not appreciate my important, needed, complex skill set being framed as something that is necessarily oppressive to me. I do not appreciate the suggestion that I am somehow being tricked into doing the hard and necessary work that is deeply important to me. This discourse devalues emotional labour. So, instead of assuming that emotional labour is necessarily and inevitably exploitative, can we consider how we might accept emotional labour ethically?"

Anti-Civilization AMA: Interesting AMA from a few anti-civ anarchists that address some of the most common questions around transphobia and ableism, along with questions about gardening, cities, asteroids, and more. "First, I would say that a huge amount of illness and disability is a product of civilization […] Second, a huge amount of folk medicine has been lost and nearly wiped out by specialization and the division of labor. I think the technocratic medical establishment, broadly speaking, is a symptom of and producer of deskilling and dependence. […] Third, I think a critique of the medical establishment is important for keeping our perspective of its value in check. […] Fourth, a huge part of the reason we need specialized care for certain groups like the elderly, sick, and disabled is that most people do not have the time and energy to care for those to whom they are close and do not live with them, and moreover because many people do not have close ties and so need to seek care from specialists. […] Fifth, as regards trans people, I am not trans myself and do not claim to know that experience (or anyone else's experience) except by inference; but I am or have been close with a number of people who identify as gender non-conforming in different ways and have talked with them at some length on these topics. Some have told me that they think some significant part of their gender dysphoria is a result of the intense imposition of gendered ideology that has always characterized civilization, and that they might feel it less intensely in a very different world."

People lie on the ground outside the Wisconsin capitol holding tombstones above them as part of a die-in to protest the repeal of the Affordable Care Act. The tombstones list various reasons for death: "Pre-Existing Condition: Being Female", "Pre-Existing Condition: Cancer", "Cut From Medicaid", "Couldn't Afford Premium", "Suicide: Mental Health Coverage Optional", "Pre-Existing Premium Too High", and "One of the 24 Million". Source.

Women in Refrigerators

eyes I dare not meet in dreams: Short story by Sunny Moraine. "At 2:25 a.m. on a quiet Friday night on a deserted country road in southeastern Pennsylvania, the first dead girl climbed out of her refrigerator."

Women in Refrigerators: "'Women in Refrigerators' can refer to three different pages on TVTropes: Disposable Woman: A female character, who is present in the story just so that she can be attacked. Her attack spurns the story forward, and that's all. Stuffed into the Fridge: A character is killed off in a particularly gruesome manner and left to be found just to offend or insult someone, or to cause someone serious anguish. Women In Refrigerators: The original website, created by Gail Simone, documenting the disproportionate tendency of female characters in comic books to be brutalized."

Short Business: "Eyes I Dare Not Meet In Dreams" by Sunny Moraine: "Moraine's creepy short story is taking on that most despised of tropes - fridging the ladies. Fridging is the practise of killing a character (usually a female, non-binary, chromatic or LGBTQ character, and including characters that have intersectional identities) in order to further a plot. Characters are usually fridged in order to give a male character (generally a cisgendered, straight and white male character) the motivation to pursue a goal or embark on a quest. Stories that hinge on an instance of fridging also tend to focus on the male character's emotional pain and desire for revenge rather than the life, feelings or pain of the character who gets fridged."

A smiling Black woman poses with her sign that reads, "Pay Me Like A White Man!" at the Women's March in Washington, D.C. back in January. Source.

Direct Action Item

June 11th was the International Day of Solidarity with Long-Term Anarchist Prisoners. "Each year, June 11th serves as a day for us to remember our longest imprisoned anarchist comrades through words, actions and ongoing material support." Prisoner support is important, under-acknowledged work. What can you do to help? From regular correspondence, being on a support team, and fundraising to sharing prisoners' stories and words, putting up flyers, and writing one-off letters, your imagination—and unfortunately, prison correspondence restrictions—is the limit!

A large billboard displays a quote by Robert Jones: "We can disagree and still love each other—unless your disagreement is rooted in my oppression and denial of my humanity and right to exist." Source.

If there’s something you’d like to see in next week’s #RT, please send us a message.

In solidarity!

What is direct action? Direct action means doing things yourself instead of petitioning authorities or relying on external institutions. It means taking matters into your own hands and not waiting to be empowered, because you are already powerful. A “direct action item” is a way to put your beliefs into practice every week.

0 notes

Text

a friend of mine linked this interesting article: How French intellectuals ruined the West and it has some interesting ideas but I need to nitpick at a few things

“This, along with Foucauldian ideas, underlies the current belief in the deeply damaging nature of “microaggressions” and misuse of terminology related to gender, race or sexuality.” Is she suggesting that microagressions are not deeply damaging? Or that the language used to discuss gender, race or sexuality does NOT affect the politics of the discussion at hand, sometimes even making the argument itself aggressive?

“we are at a unique point in history where the status quo is fairly consistently liberal, with a liberalism that upholds the values of freedom, equal rights and opportunities for everyone regardless of gender, race and sexuality.” This is highly subjective depending on who and where you are! In response to this, I’m just going to copy a status written by a transgender woman living in Oregon: “But think of the time we exist in. Where fascists have full backing of the cops to beat people on the streets with impunity, where women’s health is being attacked simply out of violent misogyny to the point where almost every form of health care for women is being threatened, and where the right-wing is getting more and more violent and dangerous and powerful while the attempts to be kind and compromise have only made the problem worse because the fascists interpret that as weakness and have openly stolen elections and given rise to a whole resurgence of literal nazis happily sieg hieling across America.” These two women are literally talking about modern times in the same country!

“Freedom of speech is under threat because speech is now dangerous. So dangerous that people considering themselves liberal can now justify responding to it with violence. The need to argue a case persuasively using reasoned argument is now often replaced with references to identity and pure rage.” Speech has always been dangerous. Speeches about how black people are shiftless criminals, Muslims are violent sexist terrorists, trans women are child rapists are dangerous. Yes, we have to watch ourselves not to censor others just because we catch a whiff or a hint of opposition. At the same time I see nothing wrong with censoring racist, white supremacist speeches done in public places by drowning them out with megaphone noise. Is this the violence she speaks about? Or is she talking about people vandalizing and setting the Free Speech bus on fire? Because that bus was literally a tool to spread hatred and misinformation around, stopping it was an action that benefited everyone. Extreme yes, but also justified. I know saying “the end justifies the means” is a dangerous thing to say, because it can easily slide into becoming oppression. It’s something important to watch out for. However, I don’t think it’s NEVER appropriate, I’m just not that hardcore of a pacifist.

“Despite all the evidence that racism, sexism, homophobia, transphobia and xenophobia are at an all-time low in Western societies, Leftist academics and SocJus activists display a fatalistic pessimism,” Again, highly subjective and a tad too optimistic in my opinion (this piece was published March 27 of this year, post-US election and post-all the shitstorms that came of it). There is truth here in that people tend to focus on the negative and that the negative tends to make bigger news than the positive. THAT SAID I’m really doubting that “all time low” when in the US and Europe literal white supremacy parties are getting a lot of political traction. Heck, I’d say the way that the US election and Brexit happened was due to xenophobia. What’s the reality then?

“In South Africa, the #ScienceMustFall and #DecolonizeScience progressive student movement announced that science was only one way of knowing that people had been taught to accept. They suggested witchcraft as one alternative.” I thought we were talking about Western postmodernism here? And this statement has been heavily condemned by African scientists and scholars, some of them even the students at the event! Also one person/group going to an illogical extreme doesn't mean the entire movement is invalid. This reminds me of the BLM activist who suggested we phase out the police entirely: an very reactionary and implausible goal; but that doesn't negate the fact that police brutality is highly racialized and that's a big problem. Racist bias in science and medicine are a problem too.

“I encountered the same problem when trying to write about race and gender at the turn of the seventeenth century. I’d argued that Shakespeare’s audience’s would not have found Desdemona’s attraction to Black Othello, who was Christian and a soldier for Venice, so difficult to understand because prejudice against skin color did not become prevalent until a little later in the seventeenth century when the Atlantic Slave Trade gained steam, and that religious and national differences were far more profound before that. I was told this was problematic by an eminent professor and asked how Black communities in contemporary America would feel about my claim. If today’s African Americans felt badly about it, it was implied, it either could not have been true in the seventeenth century or it is morally wrong to mention it.” Problematic does not mean “it shouldn’t exist”, it means “you need to examine this more closely and critically to make sure it passes muster”. Studying racism and colorism and how attitudes towards black people have fluctuated across the ages is actually important work!, but you do have to watch out with how you present and phrase things. And I think you’re reading too much into that implication, because I get the feeling most non-Shakespearean scholars would find that tidbit fascinating.

“The rise of populism and nationalism in the US and across Europe are also due to a strong existing far-Right and the fear of Islamism produced by the refugee crisis.” I agree with this, but it seems in contradiction to the earlier bit about how such things are at an all-time low.

“The Left is not responsible for the far-Right or the religious-Right or secular nationalism, but it is responsible for not engaging with reasonable concerns reasonably and thereby making itself harder for reasonable people to support. It is responsible for its own fragmentation, purity demands and divisiveness which make even the far-Right appear comparatively coherent and cohesive.

We must address concerns about immigration, globalism and authoritarian identity politics currently empowering the far- Right rather than calling people who express them “racist,” “sexist” or “homophobic” and accusing them of wanting to commit verbal violence.” So we should address these concerns, but not identify the root cause? We can acknowledge and validate people’s concern while still pointing out that these ideologies were borne from prejudice and hatred. This last bit seems overly concerned with white fragility: we can tell people they’re wrong, but if they call them racist the whole argument gets shut down. If this is the problem, what solution is the author suggesting? That we tiptoe around the feelings of the people who are (ignorantly or not) espousing harmful ideas?

0 notes

Link

To save our movements, we need to come to terms with the connections between gender violence, male privilege, and the strategies that informants…use to destabilize radical movements….Despite all that we say to the contrary, the fact is that radical social movements and organizations in the United States have refused to seriously address gender violence as a threat to the survival of our struggles.

– Courtney Desiree Morris, “Why Misogynists Make Great Informants: How Gender Violence on the Left Enables State Violence in Radical Movements”