#tolmie government

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Photo

“Hands Off Wages, Is Warning of Conservatives,” The Province (Vancouver). March 7, 1931. Page 1. --- Vancouver Executive Demands Exemptions Up to $2000. === Patronage Bacon Issue In Demanding Resignation of Members. ---- EMPHATIC protest against an Provincial Government tax devoid of exemptions except for the very lowest salaries and for farmers isvoiced in a resolution passed by the Conservative Association at a meeting Wednesday night.

"We do not approve of a direct taxation on wages," declared party leaders in a formal resolution, "but if the province's financial condition is as bad as suggested and there is no way out except by direct income taxation of one per cent., there appointments. should be exemption of $1000 for single persons and $2000 for married persons or single persons with dependents."

MORE AND BETTER BACON. While officers of the association are both shy and forgetful when questioned about proceedings Wednesday night,

Party workers voiced loud complaints about the lack of patronage available from the Tolmie administration. This complaint was chiefly responsible for the resolution which called for the resignation of the six Vancouver members of the Legislature, but it carried with it a promise of support if these representatives took action to bring home the patronage bacon.

IGNORED BY CABINET. Supporters of the motion asking for resignation of the Vancouver members state that the Tolmie government has consistently refused to listen to the workers on the subject of government they admit that the then approaching budget and the matter of patronage.

Discontent became so general in Conservative ward associations, they say . that an effort was made to discuss the situation with a member of the cabl net, who, they continue, sidestepped the meeting on one pretext and an While officers of the association are other.

The gathering storm broke Wednesday night with passage of the resignation notice.

#vancouver#tax exemption#income tax#tax increase#tolmie government#government of british columbia#political patronage#conservative party of british columbia#great depression in canada#bc politics

0 notes

Photo

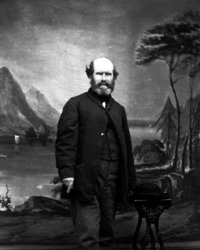

William Fraser Tolmie was born in Inverness on February 3rd 1812, I have the same surname but he isn’t an ancestor, as far as I am aware.

William’s mother died when he was three and he spent some years under the “irksome and capricious authority” of an aunt. He was educated at Inverness Academy and Perth Grammar School. An uncle encouraged his interest in medicine and is said to have financed his studies at the medical school of the University of Glasgow for two years, 1829–31. Although almost invariably referred to as Dr Tolmie, he was not an md: during these two years he worked for credits toward a diploma as licentiate of the Faculty of Physicians and Surgeons of Glasgow, a body independent of the university. Tolmie did well in his studies, won prizes in chemistry and French, and received his diploma in the spring of 1831. He had hoped to study in Paris, but a near-fatal illness prevented him. When he recovered, he served from February to May 1832 as clerk in an emergency cholera hospital organized in Glasgow to cope with the epidemic then raging.

In the summer of 1832 the Hudson Bay Company was looking for two medical officer, William and another, Dr Meredith Gairdner signed that September a five-year contract to serve in the dual capacity of clerk and surgeon. As a clerk he would receive an annual salary rising from £20 to £50, and as a surgeon £100 per annum.

The ship arrived at Fort Vancouver in the spring of 1833. In his journal, he wrote about his accommodations at the fort, recording that the doctor's office had "a very excellent supply of surgical instruments." Just days after his arrival, Chief Factor Dr. John McLoughlin was stricken by the so-called "intermittent fever" (malaria). Tolmie treated him by him, a common practice in 19th century medicine. Like most doctors at the time, Tolmie was also a dedicated naturalist, and many plant and animal specimens as he travelled through the Pacific Northwest. He sent at least two collections of Northwest bird and animal specimens to Scotland - one to a museum in his hometown, Inverness, and one to fellow naturalist John Scouler. After Fort Vancouver, Tolmie went on to serve at several other Hudson's Bay Company posts in the Pacific Northwest.

William Tolmie enjoyed a good relationship with Native Americans, and in one case supported Chief Leschi of the Nisqually Tribe who was was charged with murder during the Puget Sound War, oor William measured distances, and determined it was impossible for Leschi to have made the trip to the murder site in the time required. The local Military refused to carry out the sentence as Leschi would not have been guilty as the tribe and the government were at war at the time.

Tolmie petitioned the Governor for Clemency, but the sentence was upheld. . Leschi was executed in 1858. Later, the trial was judged to have been unlawfully conducted, the execution wrong, and Leschi innocent.

He died at age 74 in Victoria, Canada and Tolmie State Park Washington, is named after him. Tolmie was the first European to explore the Puyallup River valley and Mount Rainier in what is now Washington Tolmie Peak is named in his honour, as is Tolmie Street in Vancouver. Plants bearing his name include Tolmie's star-tulip (Calochortus tolmiei) and Tolmie's onion (Allium tolmiei). The scientific name of MacGillivray's warbler is also named for him: Oporornis tolmiei.

13 notes

·

View notes

Link

#CAPSecurity#capsecurity#commonlaw#Constitution#debtloanpayoff#debttermination#FederalTerritorialGovernment#historicalfacts

0 notes

Photo

“We Oughta Get These Unions Affiliated - Gosh Ding It!” Vancouver Sun. March 2, 1933. Page 1.

#vancouver#political cartoons#editorial cartoons#satirical cartoons#british columbia history#british columbia politics#tolmie government#conservative party of bc#i don't get it#great depression in canada

0 notes

Text

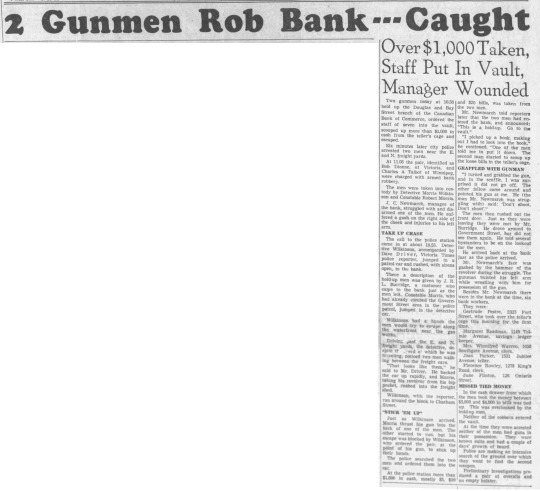

"2 Gunmen Rob Bank - Caught," Victoria Daily Times. September 20, 1943. Page 1. --- Over $1,000 Taken, Staff Put In Vault, Manager Wounded ---- Two gunmen today at 10.50 held up the Douglas and Bay Street branch of the Canadian Bank of Commerce, ordered the staff of seven into the vault, scooped up more than $1,000 in cash from the teller's cage and escaped,

Six minutes later city police arrested two men near the E. and N. freight yards. At 11.06 the pair, identified as Bob Dionne, of Victoria Charles A Talbot of Winnipeg, were charged with armed bank robbery.

The men were taken into custody by Detective Morris Wilkinson and Constable Robert Morris. J. C. Newmarch, manager of the bank, struggled with and disarmed one of the men. He suffered a gash on the right side of the cheek and injuries to his left arm.

TAKE UP CHASE The call to the police station came in at about 10.55. Detective Wilkinson, accompanied by Dave Driver, Victoria Times police reporter, jumped in a patrol car and rushed, with sirens open, to the bank.

There a description of the hold-up men was given by J. R. L Burridge, a customer who came to the bank just as the men left. Constable Morris, who had already combed the Government Street area in the police patrol, jumped in the detective car.

Wilkinson had a hunch the men would try to escape along the waterfront near the gas works.

Driving west of the E. and N. fright yards, the detective, despite the speed at which he was traveling, noticed two men walking between the freight cars. "That looks like them," he said to Mr. Driver. He backed the car up rapidly, and Morris, taking his revolver from his hip pocket, rushed into the freight shed. Wilkinsen, with the reporter. ran around the block to Chatham Street.

"STICK 'EM UP" Just as Wilkinson arrived, Morris thrust his gun into the back of one of the men. The other started to run, but his escape was blocked by Wilkinson, who ordered the pair, at the point of his gun, to stick up their hands.

The police searched the two men and ordered them into the car.

At the police station more than $1,000 in cash, mostly $5 and $10 and $20 bills, was taken from the two men.

Mr. Newmarch told reporters later that the two men had entered the bank, and announced: "This is a hold-up. Go to the vault"

"I picked up a book, making out I had to look into the book," he continued. "One of the men told me to put it down. The second man started to scoop up the loose bills in the teller's cage.

GRAPPLED WITH GUNMAN "I turned and grabbed the gun, and in the scuffle, I was surprised it did not go off. The other fellow came around and pointed his gun at gun at me. He (the man Mr. Newmarch was struggling with) said: "Don't shoot. Don't shoot"."

The men then rushed out the front door. Just as they were leaving they were met by Mr. Burridge. He drove around to Government Street, but did not see them again. He told several bystanders to be on the lookout for the men.

He arrived back at the bank just as the police arrived. Mr. Newmarch's face was gashed by the hammer of the revolver during the struggle. The gunman twisted his left arm while wrestling with him for possession of the gun.

Besides Mr. Newmarch there were in the bank at the time, six bank workers.

They were:

Gertrude Pestre, 2323 Fort Street, who took over the teller's cage this morning for the first time.

Margaret Readman, 1149 Tolmie Avenue, savings ledger keeper.

Mrs. Winnifred Warren, 1000 Southgate Avenue, clerk.

Joan Parker, 1531 Jubilee Avenue, teller.

Florence Rowley, 1278 King's Road, clerk.

June Flinton, 126 Ontario Street.

MISSED TIED MONEY In the cash drawer from which the men took the money, between $3,000 and $4,000 in bills was tied up. This was overlooked by the holdup men.

Neither of of the robbers entered the vault.

At the time they were arrested neither of the men had guns in their possession. They wore brown suits and had a couple of days growth of beard.

Police are making an intensive search of the ground over which they went to find the second weapon.

Preliminary Investigations pro duced a pair at overalls and an empty bolster.

#victoria#bank robbery#bank robbers#masked bandits#armed robbery#armed robbers#bank clerks#canada during world war 2#crime and punishment in canada#history of crime and punishment in canada

0 notes

Text

“If labour camps were to be the solution to the transient problem, it would make fiscal sense for those who already owned camps to branch out into this line of business. On 29 October 1930, Relief Officer Cooper, along with Mayor Malkin and a handful of aldermen, met with a delegation from the BC Loggers’ Association at the latter’s request. In a memo to Alderman Atherton a few days later, Cooper noted that “bad market conditions” would soon add to the seven thousand lumber workers already jobless. The association’s representatives, led by those from the Abernethy Lougheed Logging Company, offered to “accommodate these men in the Camps” under the arrangement that Vancouver would contribute money toward feeding the jobless loggers, while the industrialists would provide “sleeping accommodation free” to the municipality. “A salient point of the proposal,” Cooper pointed out to Atherton, “is that the men should sign acknowledgements for the amount expended, which would be collected by the Loggers’ Association from their pay, when conditions are again normal.”

In short, as part of a relief program, unemployed men would be charged not just for food but also for the use of a bunk in a bunkhouse that would have otherwise remained empty, and then would have to work off their incurred debt once market conditions indicated the resumption of activities: not for nothing had British Columbia earned the nickname “The Company Province.” Cooper and the City’s other elected officials believed that they lacked sufficient funds to devote at the outset of the project and encouraged the association to present its plan to the Province. Meanwhile, several representatives of the United and Anglican churches expressed their concern that the plan entailed “comparative idleness” for the unemployed because it contained no work-related component.

Substantial controversy erupted when knowledge of the offer became public: the Abernethy Lougheed Logging Company was partly owned by Nels Lougheed, a long-time Tory MLA and a current cabinet minister of Tolmie’s government. With a political firestorm spreading, Lougheed contacted Cooper via telephone to clarify matters, after which Cooper wrote a curious memorandum to Atherton, which, in today’s terms, resembles a non-denial denial:

The suggestion that the Abernethy Lougheed Co. be paid $1.00 per day for boarding single men, did not originate with the Company. During the discussion between representatives of the City and the Company as to how best to utilize the vacant camps for relief purposes, a tentative suggestion was made by the Company’s representatives that the City pay $1.00 towards the $1.50 per day which is the approximate cost of feeding the men under usual conditions.

Alderman Angus MacInnis loudly denounced the plan at the 3 November meeting of City Council. Observing that no actual logger had been consulted, MacInnis highlighted the Loggers’ Association’s long opposition to industrial unionism, which had led the association to maintain what MacInnis claimed was “the most efficient blacklist of any organization on this continent.” Instead, “the loggers should get assistance the same as all other workers,” he demanded. Most council members ignored MacInnis and passed a motion that civic representatives should express their support for the plan in the upcoming meeting with the provincial government. On 11 November, Mayor Malkin offered to purchase bedding to be used by Abernethy Lougheed as an incentive for the Province to adopt the plan. Nonetheless, MacInnis did not stand alone in opposition to the camps. “Not a ‘Bum’” wrote to the Vancouver Sun to complain of the association’s logic. He noted that an association member had declared that the lumber workers to be housed in the camps “are not bums. They have too much pride to appeal for aid from the city.” The disgruntled worker went on: “This appears to be a direct slap to all who register for relief work. It is a fine state of affairs we have arrived at when a man who registers for work is branded as a ‘bum.’” The most detailed critique of the plan appeared in the Unemployed Worker under the title “Back to the Woods”:

The Lumber Bosses of the province intend taking advantage of the plight of the thousands of idle loggers in order that in the future they will be able to exploit them even more savagely than heretofore. This gang of industrial pirates have presented to the civic and provincial authorities a scheme which in its viciousness beats anything yet launched. They want to get the jobless loggers out in their logging camps to be fed until the camps open up (whenever that will be). The money is to be advanced by the government and charged against the loggers, to be paid back by them when they start work. This scheme is along the same line as the Belgian bosses, through King Leopold, put over in the Belgian Congo, which was, and is a world scandal. Or like the debt system of slavery in the British African possessions and India. The lumber barons want a tighter grip on their slaves and this is why they are trying to introduce the peonage system in the woods. . . . The introduction of such a system will mean that the loggers will be bound to the bosses by the debts contracted and be in an even more helpless condition than before. This is the most brazen attempt yet made to prevent workers leaving the job when conditions become rotten.

The global analysis in this Communist critique captured the plan’s most notable feature: its quasi-legal binding of loggers to logging companies in a manner calculated to ensure their future dependence and thus their availability for work. Just as meal and bed tickets issued for the Central City Mission or the Emergency Refuge separated homeless transients from the free market and subjected them to forms of discipline, the scheme of the Loggers’ Association would deny to lumber workers the right to apply for government relief or even to remain in Vancouver. Instead, relief would become a loan, although without the contractual protections usually afforded in such an arrangement In other words, this was not relief at all but rather unfree labour-in-waiting, a form of “peonage” made possible by the economic crisis.

Not surprisingly, the loudest municipal campaign for relief camps was Vancouver’s. While lobbying the province to endorse the plan of the Loggers’ Association, the Relief and Employment Committee simultaneously discussed a proposal for a “concentration camp” to be set up in the Exhibition buildings in Hastings Park. The cost to house a thousand men for five months was estimated at $10,000, exclusive of food, in addition to the $7,000 start-up expenses. Some residents worried that council members had not thought through the ramifications of creating a camp on the Exhibition grounds. Although then a luggage salesman, Mr. F. Leighton Thomas had had some experience with disciplinary projects; besides having worked as an inspector on the Canadian Pacific Railway, Thomas claimed to have participated in British campaigns in Afghanistan, Alexandria, and Burma. While believing the idea of labour camps to be “an admirable one,” Thomas felt obliged to draw attention to their history in Vancouver, building his narrative around “the tremendous difference in morale of the unemployed today, and the men (largely Veterans of the Great War) who were formerly in camp at Hastings Park” in 1922:

The unemployed of today are largely made up of the scum of Europe, wholly undisciplined, and almost entirely under the influence of these Communistic Leaders, and if you put a thousand men in camp there, I am perfectly certain that unless they are under the strictest discipline and controlled by an adequate Police Force, then you are going to have trouble galore.

Thomas advocated using RCMP officers to control the population, because “the scarlet coat and the gun on a North West Constable has more effect, on these scum of European hoboes, than twenty City Constables (no matter how good they may be) would have.” If the council failed to take adequate measures, “the City may wake up to find the whole of their Exhibition Building in ashes.” But even before the mayor received this dire warning, support for a civic camp had met with practical limits, related not to fears of destruction but to financing.

Civic leaders once again turned to their brethren. In January 1931, City Council sent a group to the capital to meet with Tolmie’s Unemployment Committee. The message was a simple one: “single men could be maintained in camps or central stations at considerably less cost” than the current arrangements of bed and meal tickets. Delegates stressed the necessity of a “substantial initial outlay” in order to reconfigure “certain public buildings . . . as central stations for the unemployed single men.” Additionally, the representatives argued that the lion’s share of financial responsibility should rightly be assumed by the other governments because the camps would be used to house transients from across Canada. The politicians left Victoria optimistic that Tolmie would fund Vancouver’s camps.”

- Todd McCallum, Hobohemia and the Crucifixion Machine: Rival images of a new world in 1930s Vancouver. Edmonton: Athabaska Univesity Press, 2014. pp. 205-208.

#vancouver#canadian history#relief camps#work camps#administration of poverty#unemployment#unemployed#unemployment relief#loggers#logging company#logging camp#bush camp#forced labour#when freedom was lost#infrastructure construction#company province#capitalism in canada#capitalism in crisis#great depression in canada#working class politics#academic research#research quote#hobohemia and the crucifixion machine#british columbia history#bc politics

6 notes

·

View notes

Photo

William Fraser Tolmie was born in Inverness on February 3rd 1812, I have the same surname but he isn't an ancestor, as far as I am aware.

William received a medical degree from the University of Glasgow at age 20 and was a licentiate on the faculty of the university. In 1832, when the Hudson's Bay Company was looking for medical officers for the Columbia District of the Pacific Northwest, Dr. Tolmie signed a five-year contract to serve in the dual capacity of clerk and surgeon.

He arrived at Fort Nisqually Washington, May 1833 and served as the post's first surgeon. He soon was trading furs with the Indians and showed a marked aptitude for dealing with them. As a surgeon and trader, he arranged good relations with the Native Americans and served as chief legislator for the Hudson's Bay Company north region for some 16 years.

In 1859, the Hudson's Bay Company transferred him to British Columbia, where he served on the HBC Board of Management until retiring in 1871. He also was active in politics, serving as a member of the House of Assembly of Vancouver Island and a member of the Legislative Assembly of British Columbia.

William Tolmie enjoyed a good relationship with Native Americans, and in one case supported Chief Leschi of the Nisqually Tribe who was was charged with murder during the Puget Sound War, oor William measured distances, and determined it was impossible for Leschi to have made the trip to the murder site in the time required. The local Military refused to carry out the sentence as Leschi would not have been guilty as the tribe and the government were at war at the time.

Tolmie petitioned the Governor for Clemency, but the sentence was upheld. . Leschi was executed in 1858. Later, the trial was judged to have been unlawfully conducted, the execution wrong, and Leschi innocent.

He died at age 74 in Victoria, Canada and Tolmie State Park Washington, is named after him. Tolmie was the first European to explore the Puyallup River valley and Mount Rainier in what is now Washington

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

“In April 1930, [Vancouver] City Council passed a resolution asking for help from the provincial government on the basis of an estimate that 60 percent of relief cases had resided in Vancouver for less than six months. By June’s end, after Colonel H.W. Cooper had become the relief officer, the department had already consumed almost $350,000 of its $500,000 budget, and City Comptroller A. J. Pilkington estimated that an additional appropriation of at least $250,000 was required to cover projected expenditures for the remaining six months. Officials complained to Premier Simon Fraser Tolmie that “this financial burden is far beyond what the City either can or should be called upon to assume.” Most of the problem, they felt, could be laid at the feet of transients: using statistics taken at the height of the influx in January 1930, they suggested that the “floating population” accounted for 80 percent of single cases and 30 percent of married cases. Hoping to prompt provincial action and to reduce their own budget, Vancouver officials ceased all relief programs for single men, transient and resident, on 10 May; married men who could not prove a continuous twelve-month residency lost their eligibility on 29 July. Civic officials opted to end relief for transients not because these people no longer required support but in defence of their argument about jurisdictional responsibility: these cases rightly belonged to other cities. Alderman Angus MacInnis criticized the policy as impractical, suggesting that officials could not enforce the requirement of twelve months of continuous residence because “you’d have to bury them before a year was up.”

Despite the policy shift, relief remained an open wound for the civic treasury. In October, Cooper announced, “The number of unemployed in the City today, cannot be less than 10,000.” Department officials observed a marked increase in applications from white-collar workers, a dangerous sign of things to come. By the third week of November, the department registered over 4,500 married men, 5,200 single men, and 144 women. Cooper maintained that these figures understated the extent of unemployment because groups like clerical workers, seamen, and union members tended to avoid state relief programs if they could. The much-hoped-for abatement of relief spending was nowhere in sight, and the streets once again turned turbulent: December 1930 witnessed unemployed demonstrations led by the usual Communist organizers. The transient was at the centre of social disorder. In the early 1930s, the transient question always possessed a particular charge on the West Coast, subsuming other types of social conflict that wracked North America. Even the campaign to ban married women from wage work failed to gather much steam in Vancouver in this period: one Mrs. Fleming noticed that Alderman Atherton raised the issue at a City Council meeting but “did not get any support.” “Why don’t they wake up?” she asked, lamenting that public discourse about state expenditures somehow always managed to miss the point.

Complaints about the cost of relief provision to transients often dominated the council’s agenda. Yet many of the budgetary issues that led to civic debt can be traced to the added expenses associated with work relief programs, enshrined as the preferred form of provision by the federal government in the Unemployment Relief Act of 1930, and not to the itinerant hordes. The act was “a measure bold in conception, yet simple in operation,” in Colonel Cooper’s judgment: “Its sponsors at least showed courage and initiative in this experiment.” His optimistic assessment is not shared by most historians, who instead point to the financial drain on municipal resources that the program entailed. The act allotted $20 million — $16 million for work relief and $4 million for direct relief — to be administered by local governments. The federal share of work relief projects was limited to 25 percent; in order to qualify, municipalities were required to put up 50 percent of the cost, with a further 25 percent contributed by the Province.

The cost of equipment and other materials as well as supervisory labour costs also belonged exclusively to cities. Cooper complimented the Unemployment Relief Act for “captur[ing] the imagination of the public.” Its structure, nonetheless, made it an expensive proposition. Federal money was allotted on the basis of the ability of municipalities to fund their share of the project, not according to the extent of unemployment in that locality; cities with small budgets or large numbers of jobless found it difficult to raise the money to provide enough work for all in need. While work relief remained the ideal form of relief provision to able-bodied men because it provided the municipality with both economic and moral dividends, or so it was thought, federal regulations made it impractical to launch projects that would put even the majority of unemployed men in Vancouver to work.

Work relief cost municipalities more than direct relief for several reasons. Projects required gang bosses, supervisors, engineers, and the occasional architect. They also involved an abundance of machines, tools, and other materials. Often, these had to be purchased for the specific task at hand; roadbuilding projects, for instance, could require a greater number of shovels than possessed by smaller municipalities, and the use of equipment on work relief projects contributed to its depreciation. These schemes also often involved extensive capital outlays. During the early 1930s, Vancouver involved hundreds of unemployed men, most of them married residents, in the construction of the Fraser Golf Course, a municipally owned enterprise in South Vancouver.

Many politicians favoured this project because once completed, it would produce revenue. Yet for the unemployed to be able to finish the first nine holes so that the course could open, the municipality had to commit money to purchasing a large number of lots that remained in private hands. At a time when many businesses were forced to undertake retrenchment measures, government spending of this type inevitably ruffled feathers. Finally, because this type of program was predicated upon an exchange — relief in return for work — it appealed to those who hesitated to accept charity because of its association with dependence. Relief Officer Cooper noted a marked increase in the number of single men applying for relief after the department began a program requiring them to work one day per week for their relief. “These men would not accept relief unless they gave some return for it,” he explained.

This was the revenge of work discipline: more applicants came out of the woodwork to take advantage of the opportunity to work for relief, overturning accepted wisdom that work-test programs always reduced the number of applicants. In many ways, work relief projects had a disproportionate effect on civic resources compared to direct relief, so much so that Vancouver officials illegally diverted provincial relief funds to cover their own administrative spending on bylaw-mandated road work projects in 1933 and 1934.

Cooper eventually recognized that the policies laid out in the 1930 Unemployment Relief Act would not resolve the bulk of Vancouver’s difficulties because of the investment required of the municipality. The will to put transients to work was there, but the resources were not. Only one month after it was enacted by law, Cooper estimated that he needed an additional grant of $127,000 to cover expenses on work relief projects. Despite the lack of available funds, Cooper emphasized the moral and physical benefits accruing to those who required work of recipients: regardless of budgetary constraints, married men should be obliged to work one day per week in return for their allotment of groceries in order to “prevent the deterioration inevitable to a long spell of idleness. A conscientious applicant would feel that he was in some measure earning his family’s food, and it would also serve to eliminate any who might attempt to impose upon the humanity of the taxpayers.” Gangs of single men found themselves clearing driftwood from English Bay beach and cutting logs into firewood to be used to heat the houses of married relief cases. Recognizing the limited disciplinary reach of his department, Cooper hoped that private citizens would band together to provide programs for single transients in order “to make profitable their enforced idleness.” However, as noted, federal policy made it too expensive for the Relief Department to arrange for work for all male relief recipients, resident and transient. In future, Vancouver’s shrinking work relief budget would be largely reserved for male resident household heads and would be doled out not as a form of punishment but as a reward: in return for working, married men could earn an additional allowance. In this sense, Vancouver work relief projects in the mid-1930s acted as a bonus system analogous to Ford’s profit-sharing system for automobile workers.” - Todd McCallum, Hobohemia and the Crucifixion Machine: Rival images of a new world in 1930s Vancouver. Edmonton: Athabaska Univesity Press, 2014. pp. 121-123.

#vancouver#canadian history#relief recipient#relief department#welfare#welfare officer#administration of poverty#welfare as social control#unemployment#unemployed#single unemployed men#provincial-dominion relations#great depression in canada#transients#hoboes#workfare#municipal government#make work projects#civic improvements#hobohemia and the crucifixion machine#academic research#research quote

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

“GO EAST FOR MORE RELIEF,” The Province (Vancouver). April 5, 1932. Page 20. --- Hon. Ralph Bruhn and Ald. John Bennett Away. ---- COOPER GOES ALSO --- Ald. John Bennett, chairman of the civic finance committee, appointed by the City Council Monday afternoon to watt on Dominion authorities to seek approval of Vancouver's new $1,550,000 relief programme, left for Ottawa this morning Col. H. W. Cooper, city relief officer, was this morning instructed to join Ald. Bennett on the trip.

They accompanied Hon. R. W. Bruhn, minister of public works, who arrived from Victoria overnight. The minister will make representations to Ottawa regarding amplification of the relief programme in British Columbia. REPRESENTS PREMIER. According to statements made to the civic relief committee, Premier S. T. Tolmie had intended to attend conference of provincial premiers with federal authorities in Ottawa on April 15. This date was advanced to April 9, and the Premier delegated Mr. Bruhn to represent him.

In telephonic communication with civic authorities, Mr. Bruhn suggested that Vancouver send a delegate to a subsequent interview with the Dominion Government on relief matters.

TO URGE PAYMENT. Apart from the proposed new relief programme, the city is seeking payments from federal and provincial authorities of roughly $981,000 owed to Vancouver by the province and Dominion as their share of relief costs in the city. On Monday $37,000 was received from the province toward relief work costs.

#vancouver#legislative assembly of british columbia#unemployment relief#unemployment#unemployed#relief department#relief officer#dominion-provincial relations#british columbia politics#welfare officer#government of british columbia#great depression in canada#capitalism in canada#capitalism in crisis

0 notes

Text

“On Halloween 1931, Nelson businessman Charles F. McHardy lectured Premier Simon Fraser Tolmie on the state of his province’s roads. “Good roads mean more to us in dollars and cents than tariffs, or inter-Empire trade”: McHardy based this bold declaration on his personal observations of daily life in the hinterland. “We travel the roads daily,” he wrote, “and are paying a terrific price for damages as a result of accidents and a still larger price in unwarranted and unfair wear and tear. On top of this, the loss we sustain, owing to the fact that tourists will only travel over our roads once, and will, if possible, keep their friends from coming even once, is a very serious matter.” In McHardy’s analysis, the terrible condition of British Columbia’s roads served as an obstacle to, rather than a conduit for, economic development. As long as transportation remained difficult and dangerous, he argued, the Depression would continue.

With this account of BC’s prospects, McHardy found a compatriot in engineer Pat Philip. Philip valued the highways of British Columbia as an asset worth $67 million at the end of 1932. Unfortunately, the policy of “so-called retrenchment” then pursued, including the suspension of basic road maintenance, meant “a heavy loss to the Government through deterioration.” Philip maintained that in calculating the balance sheet, the debit column had to include the subsequent “loss of revenue from the tourist traffic and the economic loss suffered by the people, which are incalculable.” While “fully in sympathy with the policy of reducing expense to the minimum,” Philip remained firm in his belief that cutting spending on road maintenance was short-sighted, damaging future economic development. Of the plethora of commentators on the deterioration of BC’s roads, Pat Philip occupied a unique position, since he spent his days working as chief engineer of Tolmie’s Department of Public Works: as such, he was also the Deputy Minister of Public Works. From the onset of the provincial government’s relief camp scheme, Philip’s responsibilities included the planning and supervision of all work relief projects. His was a Fordist vision that embraced the potential for expansion-oriented relief projects to generate value and end the downturn sooner. A camp located adjacent to a major highway, he explained to the premier, “can be used to the best advantage in connection with construction, re-construction and repairs to the road.”

Beyond the developmental promise of road work, Philip offered a simple economic rationale: this type of endeavour, which entailed the bulk of common labour being performed under conditions of relief, would ultimately prove cheaper for the government than the postponement of all projects until after the recovery, when regular wage rates would be the norm. “The cost to the Government, using unemployed labour,” Philip observed, “will amount to approximately $40.00 per month per man inclusive of materials, etc.” However, “under normal conditions, the same work would cost the Government $100.00 per month per man.” Ever the engineer, Philip dismissed the popular perception of unemployed labour as low in value; he estimated a loss of efficiency in his relief camps of only 30 per cent. “Even with this allowance,” he noted, “you will see that there is a vast saving to the Government by now taking advantage of the surplus labour available.”

These were not the arguments of a man chiefly concerned with how best to implement humanitarian schemes. Philip did not explain how a greater rate of exploitation than that of “free” labourers would benefit the transient. There was, in fact, no contemplation of any of the character-based issues we associate with moral regulation, such as indolence and illicit sexual activity, in his administrative correspondence. Nor did Philip seek to understand the future dreams of camp residents with an eye to facilitating their dreams through government programs. Instead, Philip posed a question of property allocation: how could the government best “take advantage” of this surplus labour? Through their collective work in isolated settings, the labour of jobless men would be objectified, used to create and develop property owned by the Province. For Philip and many others, production, not regulation, formed the crux of the camp system, although to stimulate the former required the latter. Private property lay at the heart of this civilizing project, and the quest for development drew attention to the end result — the road or the sewer, the park or the golf course — and not to the exploitive social relations that produced them. Such relief schemes had a barbaric character, “taking advantage” of misery and suffering — intensifying them, in fact — to produce property and increase its value.”

- Todd McCallum, Hobohemia and the Crucifixion Machine: Rival images of a new world in 1930s Vancouver. Edmonton: Athabaska Univesity Press, 2014. p. 196-198.

#nelson#british columbia history#bc government#canadian history#relief camps#administration of poverty#work camps#forced labour#unfree labour#when freedom was lost#transients#unemployment#unemployed#single unemployed men#unemployment relief#infrastructure construction#road building#road work#great depression in canada#pressures of the great depression#academic research#research quote#hobohemia and the crucifixion machine#bc politics

0 notes

Text

“During his tenure as [Vancouver] relief officer, Colonel Cooper relied heavily on private missions because they furthered the regulatory designs of the Relief Department regarding the investigation and control of transient workers and were cost-effective in doing so, thus helping to relieve some of the workload of administering relief to thousands of people, resident and transient, in Vancouver. Indeed, the creation of a workable, separate relief system for unattached transient men that, because of its distinct administrative and provisional forms, could be financed by other levels of government would never have come to fruition without the missions, which ended up, through no fault of their own, the front-line sites of transient regulation within the city limits. ... ... we commence our investigation with the Emergency Refuge, the private charity created as an expression of the philanthropic spirit of W.C. Woodward, the son of Charles, the owner of Woodward’s Department Store, a Vancouver institution. In November 1930, W.C. launched a shelter for single transient men, who, in light of the street battles of the previous winter, had come to be considered a substantial threat to social order. Having solicited his friends to capitalize the endeavour, Woodward and his Refuge served at its peak fourteen hundred meals per day and provided beds for seven hundred. Since the Refuge extended the reach of the civic relief system with its own investigators and record-keeping services, Relief Officer Cooper arranged a cheap rate with the Refuge: $1.75 per man per week with each person to be given two meals per day. This cheap price meant that the Refuge had to keep per unit costs low in order to sustain operations, and officials more than achieved this aim. James Thomson, a Tory patronage appointment to the provincial liquor board, related the Refuge’s success to Premier Simon Fraser Tolmie: “On this agreement with the City, they ran for two months, and at the end of the period they found they had made $2,000.00 — or $1,000.00 per month. This money is in a fund, in case the operation should again be needed. This will give you some idea what thorough organization and efficiency will do.” In providing meals and beds to several thousand men over the course of two months, the Refuge accumulated value equivalent to 1,142.8 man-weeks of relief. I do not mean to suggest that Woodward and his colleagues set out to make money by providing relief to transients but rather that they simply couldn’t help themselves: in organizing the Refuge according to the business principles that struck them as common sense, they created the conditions in which surpluses were made through the thousands of relief exchanges that took place each and every day.

Vancouver was home to almost twenty private charitable institutions devoted to itinerant unemployed men, half of them exclusively religious in orientation... One April 1930 report explains that most missions quickly used up their small allocation of beds and referred the bulk of single transients who requested aid to the Relief Department instead. While these institutions contributed to the relief effort, their limited resources meant that any substantial increase in the number of jobless applicants had to be shouldered by the Relief Department. A few locations, however, did service substantial numbers. As of August 1930, the Central City Mission and the Salvation Army each housed approximately 200 men per night. In November 1930, the Ex-Servicemen’s Billets run by the Canadian Legion served food to an average 180 men. By March 1931, Legion officials estimated that they had served 500 ex-servicemen daily since November for a total of 60,000 meals. The destruction of the jungles in September 1931 forced the Relief Department to reverse its March policy that had removed transient men from the relief rolls and once again open its doors to single men.

By the third week in September, the department had issued bed and meal tickets to 2,500 single male transients, although the Tolmie government promised to reimburse the city for the cost. Faced with the necessity of once again administering to thousands of transients, Cooper toyed with the idea of abolishing the ticket system and instead devising “some central system” for feeding and housing transients, but this did not come to fruition. Instead, he opted to rely on the missions, especially the Central City Mission and the Emergency Refuge; each transient case dispatched to the missions was valued at forty cents per day for food and shelter, the same as was accorded to restaurants and rooming houses.

From the standpoint of civic administration, the missions had advantages beyond the purely pecuniary. Logging companies provided the bulk of funding for the Scandinavian Mission, an offshoot of the United Church, which fed on average two hundred men per night in the winter of 1930–31. The Scandinavian Mission conducted evening classes “for the study of English and good citizenship” for its members, mostly Swedes and Finns. “We believe,” one lumber company official wrote, “that this has had a very important bearing in offsetting the spirit of Communism which has been spreading quite seriously among the unemployed.” Cooper’s favourite, the Emergency Refuge, supplied 4,578 beds and 19,130 meals in September 1931, and 5,370 beds and 22,972 meals in October 1931, mostly to men made homeless after the clearance of the jungles. The relief officer used the Refuge “as a means of testing these men.” His logic was simple: those suspected of shirking would no doubt prefer work to a stay at the Refuge. In this way, the Refuge, with its investigatory procedures, had been of “assistance in reducing the cost to the taxpayer.”

Cooper also looked to the Refuge to discipline those who fell through the cracks of the relief camp system. The Tolmie government had pledged to create camps for those itinerants who entered British Columbia after the registration scheme closed in the summer of 1931, but this promise went unfulfilled due to the financial crisis that followed quickly on the opening of the camps, as detailed in the next chapter. Cooper proposed to put this group to work, housing them in the Refuge until the Tolmie government lived up to its pledge and arguing that, with a plan of work and strict supervision by Refuge employees, “there would be little inducement for the unemployed of other Provinces to flock to Vancouver.” Yet the Refuge also reduced the cost of relief because many transients simply refused to use bed and meal tickets issued there. One correspondent for the Unemployed Worker named “Shorty” observed that upon entering the Refuge, an official collected his book of weekly bed and meal tickets and issued him a separate ticket to be punched each day. “Many workers who get that ticket eat there only once,” claimed Shorty, and yet the Refuge could redeem the entire book of tickets: “it seems obvious that the grafter that runs the place is doing fairly well.” The available evidence allows us to confirm Shorty’s description of the process, if not the accusations of graft: in January 1932, Refuge organizers sent the Relief Department cheques totalling $4,587.80, representing beds and meals allotted by the City to transient men but not redeemed. This figure represented almost 11,500 man-days of relief since the destruction of the jungles in September. In the first two weeks of August 1932, 4,315 bed tickets were issued on the Refuge but only 2,140, just under 50 percent, were redeemed. Given a choice between a mission and the street, hundreds of unemployed men hit the pavement.

Relief Department officials thus intended their use of private charities like the Refuge to reduce relief costs and protect against what they saw as the exploitation of municipal resources by transients. At the same time, these explicitly stated goals meant that some transients were less likely to avail themselves of government aid precisely because they took offence at the suggestion that their character could be improved through a short stint under such punitive circumstances. Allotted tickets for the Mission, one unemployed man, F. H. Richardson, complained to A. E. Tutte, the head of the single men’s section. Tutte, however, refused his request for tickets for rooming houses on the grounds of moral improvement: according to Richardson, Tutte told him that “there w[ere] worse things than the do[se] of lice I would get at the Mission. That the men who were given their preference of eating places [were] probably full of venereal or some other contag[i]ous disease.”“

- Todd McCallum, Hobohemia and the Crucifixion Machine: Rival images of a new world in 1930s Vancouver. Edmonton: Athabaska Univesity Press, 2014. pp. 179-182.

#vancouver#canadian history#vancouver emergency refuge#rooming house#missions#shelters#relief recipient#relief department#unemployment#unemployed#single unemployed men#transients#administration of poverty#capitalism in canada#punishing the poor#welfare as social control#capitalism in crisis#great depression in canada#hobohemia and the crucifixion machine#canadian legion

0 notes