#to interpret the point of his arc where he shows difficulty expressing/understanding his feelings as. he doesn't even have certain feelings

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

i know i've said this before on this account but it's been a while and i feel strongly so i'll express it again: i really feel like some of yall need to stop believing that being aroace only manifests in the same few stereotypical personality types. people can be aroace despite being openly flirtatious and affectionate, people can be aroace despite having romantic and sexual desires, people can be aroace no matter what

#squishy talks too much#DISCLAIMER: yall is very general i don't mean yall as in. my followers. this is not targeted#my hot take is that i am so tired of only seeing aroace futaba and yusuke hcs#and i say this as someone who likes the aroace futaba hc#even hotter take tho: i dislike aroace yusuke. like entirely#to interpret the point of his arc where he shows difficulty expressing/understanding his feelings as. he doesn't even have certain feelings#i just kinda dislike that interpretation. nothing personal to yusuke aroace believers tho#my challenge to allo people is to have an aroace hc that makes allos go “ermmmmm they're not aroace”#“they literally said [insert statement that thousands of aroace people across the world have said] so they are NOT aroace”#anyways MAKOHARU IS AN AROACE LESBIAN RELATIONSHIP *shouting out to an entire crowd and nobody claps*

33 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Scarf - Mr. Pigeon 72 Endcard

@8unnix2 pointed out the huge presence of the scarf in the endcard.

It's funny how they particularly featured Adrien wearing that scarf in most of the posters out of all the gazillion pictures they could have used. They pretty much threw it right in our faces. Foreshadowing? Symbolism?

I have an own idea of my own. It may be a bit of a stretch.

Umbrella Scene 2 created a turning point in terms of Marinette expressing herself.

It reflected her growing and becoming more direct with her feelings.

A big obstacle in previous episodes was her inability to express her feelings, she'd never be able to express her feelings clearly. She kept sending Adrien mixed messages throughout the seasons.

However, this scene presents her taking a step forward, and clearly expressing what she wants. Instead of creating a complicated scheme or doing something stupid like saying the opposite of what she actually wants like she would've done previously.

No complications. No schemes. She straight-up asks him whether he wants to walk home with her. And that's what drives their interaction in the scene.

That conveys a shift in status quo. It reflects her learning to express her feelings clearly.

Despite her still struggling, despite her stammering, she's taken a step forward to clearly express her feelings.

And that's important to note.

I want to go back to an essential scene in the NY special.

The one where Nino and Alya discuss why Adrien and Marinette can never get closer.

Nino: Yup. I love Adrien, but he's like a baby chick that's just started cracking out of his egg. He has a hard time understanding the signals people send him.

Alya: What signals? Marinette isn't exactly sending them clearly. I mean, look! What is she doing with her arms? Telling him what to do in case of an emergency landing or something?

Nino: If only this trip could help Adrien finally come out of his shell.

Alya: And if only it could help Marinette be more honest with herself and clearer about her feelings!

The two problems that Alya and Nino highlight here are:

Marinette being unclear about her feelings.

Adrien's difficulty in "cracking out of his shell".

These are the reasons every time why Marinette and Adrien can never seem to get closer.

Marinette keeps sending Adrien mixed signals and this poor oblivious boy who's been confined to his home his entire life faces difficulty in understanding her, he's not very good with social cues in the first place, she confuses him even more. That's what contributed to miscommunication/lack of communication between them.

NY didn't really resolve this problems. It's intention was never to resolve. It's intention was to address them and build on them but never to completely resolve them. As these issues have existed for a really long time, and it takes a lot more than one special to solve them. It's part of their character arcs.

However, for Obstacle Number 1, Mr. Pigeon 72 was the turning point. Umbrella Scene 2 depicted Marinette being able to clearly express herself and carry a conversation with Adrien. It reflected that Marinette's is the closest to overcome that obstacle than ever! Which is really really good.

What about Obstacle Number 2...

Adrien's difficulty in "cracking out of his shell".

The way I interpret this phrase is that Adrien really needs to open up to his surroundings more. He's been in his little reserved shell for too long, and therefore faces difficulty in opening up to who he really is.

This was even addressed in Lies. Adrien's many masks to conceal his "real self".

His model mask and his Chat Noir self.

These are all sides to Chat.

His model image is who is father wants him to be.

Him as Chat is who he wants to be.

But is it who he really is?

His model image is to be an image of perfection.

Him as Chat is meant to be his cheerful side.

But they conceal his insecurities, his awkwardness, his deeper feelings in most cases.

They conceal his trauma.

They conceal his desires.

They conceal how scared he actually is.

He maintains these images to everyone. He doesn't want to open up to who he really is. He doesn't want to show anyone that shy, awkward, broken boy. And that is reasonable. Because that's not something you want everyone to see. But Adrien masks himself to people who want to help him. He masks it completely. It's really important that Nino mentions him cracking out of his shell.

Because Nino is the first person who saw that awkward boy on their very first day.

He saw how bad he felt with the whole incident. He saw how bad he wanted to fix things with Marinette. He saw how much it hurt for him that he felt like he messed up on his first ever day of school, and how he was clueless with what to do, with how socially incapable he is.

Adrien doesn't how to present himself. He can't open up to his surroundings. He's wears too many masks because that's what he's used to, that's what he's comfortable with. He hasn't interacted with people enough to know that it's okay to open up and express some sides to yourself that you'd think people wouldn't like (screw Gabriel for raising him to be a perfect child).

Obstacle Number 2 hasn't had its turning point yet. It still exists. The reason why it's important that Adrien opens himself up more in terms of Adrienette development is to prevent miscommunication and misunderstandings between them. Things that have been happening for the past few seasons. They need to be able to interact and understand each other better.

Coming back to the actual reason I made this post: the scarf.

The reason why the scarf is such a strong symbol to the audience is because Adrien is oblivious that Marinette is the one who made the scarf.

His under the illusion that the scarf is from his father, not Marinette.

The scarf represents his obliviousness.

Firstly, that connects with him being unaware of Marinette's feelings, which is mainly reliant on her unclear form of expressing herself, but it also shows that they're more obstacles between them than what's in their control.

Secondly, the illusion that it's from his father does build on how eager Adrien is for his father's affection, and how much he wants to believe it. But he's oblivious to his father's true intentions with this mindset, he's chasing after something that's bound to break.

Thirdly, being under his father's arm, conveys him being in his shell. He has to live up to a perfect image. Restrict himself from the world. All whilst blindly believing in his father despite his intentions. It shows that Adrien can't carry on like this. He needs to break out of this shell. He can't be perfect anymore. He shouldn't restrict himself. And he shouldn't blindly believe someone who's doing something horrible.

The massive presence of the scarf in the endcard could foreshadow a similar/sibling scene to Umbrella Scene 2.

The scarf reveal.

It's really important as this happens because it destroys everything that prevented Adrien from opening up.

He's made aware of Marinette's intentions. Causing him to see her in a much brighter light. A different life. And he's drawn to open up with her even more. It pulls them closer. She did this to make him happy. And that'll strike a chord within him that'll make him want to open up with her.

But it'll also hurt Adrien. That illusion is broken. That illusion where he thought his father actually did something affectionate and nice for him once. He's been believing and treasuring that illusion since the very beginning. He can't trust it anymore. Hope for his father, the prime reason for him being in his shell, is going to crack a little, and so is his shell, and it'll make him want to strive out of it more.

If Umbrella Scene 2 fixed Obstacle Number 1 with a turning point of Marinette striving to clearly express herself, let loose and dance in the rain for Adrienette development and Marinette development.

A Scarf Reveal will fix Obstacle Number 2 leading to Adrien to open himself up more (especially with Marinette), try to become more aware of his surroundings instead of being trapped under illusions of oblivion. Paving way for another turning point in the Adrienette dynamic and contributing to Adrien's character development.

It's a lovely win-win situation.

#sugar analyses#ml spoilers#mr pigeon 72#ml speculation#ml analysis#ml season 4#ml meta#adrien agreste#marinette dupain cheng#adrienette#ml love square#gabriel agreste#miraculous ladybug#miraculous#umbrella scene#scarf reveal

157 notes

·

View notes

Text

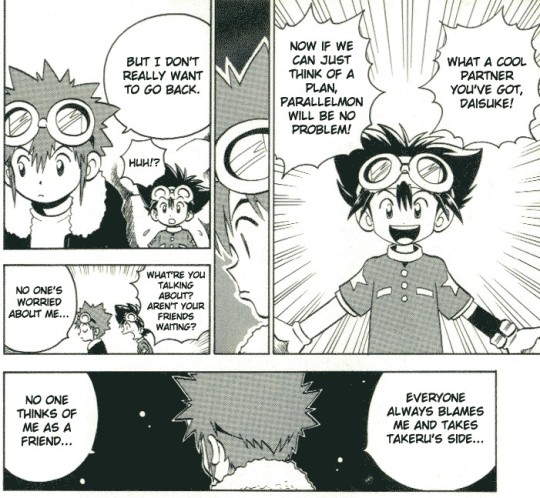

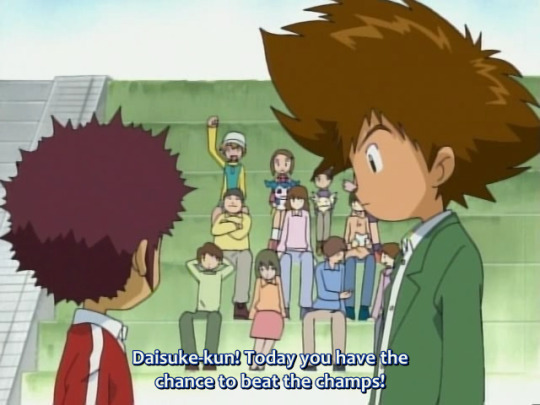

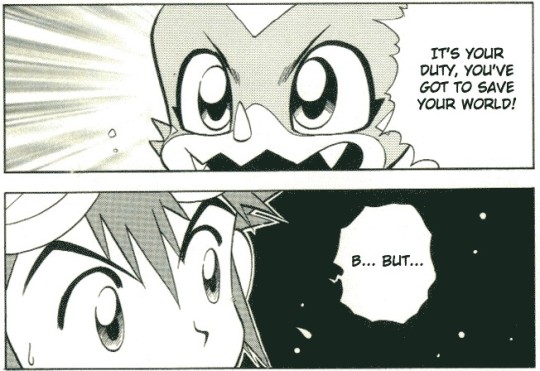

Daisuke’s characterization in V-Tamer is actually out of character

This is a post rather different from the usual content I do for this blog, and to be honest, I’m a bit hesitant about it, since it’s hard not to make it sound like some kind of scathingly critical negativity about the relevant chapter. It’s not intended that way -- V-Tamer’s crossover chapter with 02 lies firmly in “Bandai-commissioned spinoff” territory with what was most likely very little input from the anime staff, and with these kinds of things, right hand very rarely talks to left hand, and you see it in things like Tag Tamers having major contradictions with the anime despite how ostensibly important it is to 02′s story. Izawa and Yabuno were busy with V-Tamer production, and it’s very likely Toei and Bandai only provided them with very scant details of 02′s base premise (especially since the chapter itself doesn’t refer to any major 02 plot details besides XV-mon’s and Magnamon’s existence). I really do not blame them for not necessarily having thorough awareness of Daisuke and his character arc (especially since he himself is a rather deceptive character), and having to make a lot of assumptions while writing.

In the end, I decided to write this due to personal request from an acquaintance, who pointed out that there are a lot of people out there who like to claim things like "Daisuke got more character development in this single chapter than he did in 02 itself” (which is another manifestation of the constantly repeated fanbase mantra that Daisuke was lacking in that department when he really wasn’t). The thing is, this chapter’s interpretation of Daisuke is so far removed from the character he was even at the start of 02 that this “development” only works by artificially engineering a conflict that shouldn’t have even happened with Daisuke in the first place.

Again: This is not something meant to criticize this chapter as something bad (personally, I do think it’s rather entertaining in its own way) as much as, simply, out of character is still out of character, and I'm mainly just writing this in the hopes of making a case that this version of Daisuke should not be reflected back on the original series.

(Screenshots below are from the DH translation of V-Tamer, and PositronCannon’s 02 subs.)

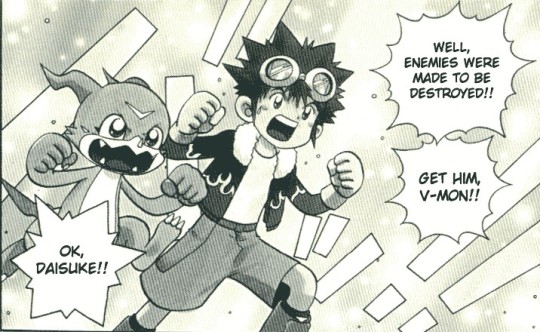

The issue here is that the whole plot of the chapter itself is based on the idea that Daisuke is the kind of person who likes fighting for the sake of fighting, and has an impulsive urge to charge in aggressively to the point of even looking down on his friends for denying him. Certainly, on the surface, it does seem to match up with Daisuke still having difficulties adjusting to these new kids being his friends at the beginning of the series, and generally having an abrasive, rough-around-the-edges personality, but...

Ah.

The above screenshots are from 02 episode 7, which is a very early episode -- one that clearly takes place before Magnamon’s appearances in Hurricane Touchdown and 02 episode 20-21, and XV-mon’s appearance in 02 episode 22 -- and one that’s still part of Daisuke’s early bout of “shallow” episodes, in which he’s still instinctively lashing out at Takeru due to his perception of having something going on with Hikari. And while he does initially lash out at them for wanting to turn back, the moment everyone else makes a good case for them turning back (especially when their own Digimon run out of energy), he -- rather easily -- grits his teeth and actually calls the retreat himself.

On top of the fact that Daisuke is very capable of pulling back when he practically understands it’s necessary (even if he hates it), some important points need to be made about his behavior here: Daisuke does not push forward on fighting because he likes fighting and attacking things, but because he practically wants to see the Dark Tower destroyed (and the Dark Tower is causing problems for everyone everywhere right now). He hates the Kaiser, and wants to fight everyone under him, because he’s hurting others. Only one episode later, Daisuke vocalizes that he’s even okay with losing a soccer game as long as he gets to play someone who’s inspired kids all over the country and enjoy the match.

The other problem is that it actually implies that Daisuke would be able to do anything without his friends’ approval. Despite Daisuke’s ostensibly rough surface demeanor, he gets strung along easily. It is absurdly easy to shut him down or override his opinions just by being assertive enough. There’s a very good reason why he’s been described as “prevented from doing much in the first half”. Daisuke spends the first half of the series largely unable to make his own decisions because his friends keep making them for him, and part of his character development involves him becoming able to actually put his foot down and do what he wants when it’s something he cares about, which is something that very much does not set in until the second half.

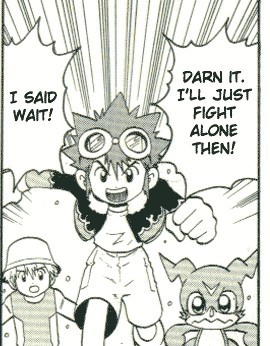

In addition, the implication that Daisuke would be actively belligerent to the point of having the priority of “destroying enemies�� instead of “helping others” is very contrary to the whole point of his character arc:

In 02 episode 20, the first time Daisuke does truly put his foot down against the wishes of the others in the group, it’s because seeing Chimeramon destroy so many things hurt him that badly that he hates sitting around and doing nothing. Again: Daisuke is a person who does things because he cares about and wants to protect others, not because he necessarily likes fighting. It’s also important that he makes this statement that he’ll go in “even alone” -- he does not look down on the others or show distaste for them for choosing to recuse, because they’re understandably exhausted, but simply says that he’s frustrated at the idea of giving up this one chance, and doesn’t want to squander it. (It’s also consistent with the way he treats the mortified Ken in 02 episode 48 -- he reminds him that Jogress won’t work if Ken’s not feeling up to it, and says that he’ll do it alone if he has to because something has to be done.)

And speaking of Ken, this trait of Daisuke’s is why that whole character arc of him reaching out to Ken works in the first place! Because, again, Daisuke hated the Kaiser because he was doing horrible things. The moment the Kaiser stopped doing horrible things, Daisuke didn’t feel up to kicking him while he was down, actually urged him to do the first thing he could do to make amends -- “go home” -- and ultimately chose to reach out to him because he thinks in terms of moving on and creating positive things, not for destruction for the sake of destruction. Because Ken seemed to not be hurting anyone anymore, and he’s actually doing something to help, so why not believe in him and let him help?

Again: with the exception of episode 48 (which is just reinforcing something from before), all of these episodes are before XV-mon’s first appearance in 02 episode 22. Daisuke had always been this kind of positive and supportive person from day one; those traits had just not been very easily visible because he was still trying to deal with his initial awkwardness and being rather rough around the edges, but they’re still traits he’d always fundamentally had.

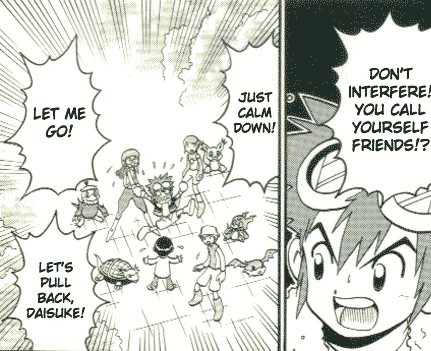

The chapter continues with Daisuke actually looking down on his other friends and protesting angrily against them trying to pull him back. Beyond the fact that (as stated above) the anime’s portrayal of Daisuke would make him very unwilling to fight back against opposition at this point of the series, the idea he’d actually be condescending about his friends is a little...hmm. Because, again, in 02 episode 7:

Daisuke does momentarily lash out at Iori and Takeru in a moment of emotional compromise when he’s stressed over Hikari getting trapped in the Digital World, but he actually takes it back. Incredibly quickly. He apologizes to Iori, and decides to not let Takeru put the blame on himself, even though his emotionally-compromised moment had initially gotten him to instinctively try to pin it on him. (Which is important because, yes, even when Daisuke’s inclined to lash out at Takeru for his perceived existing relationship with Hikari and be jealous of him, he still cares about Takeru himself to the point he doesn’t want him to load himself with the guilt.)

Daisuke’s brashness is portrayed during this early part of 02 as him very, very badly needing validation. This means that going out of his way to push aside the people he calls friends would be the last thing he wants to do, because he actually wants their approval, and for them to like him, and therefore he’s willing to apologize quickly and try to make amends because he plays badly with actual confrontation.

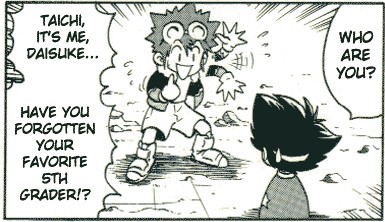

While this line isn’t quite off, it does rather clash with the way Daisuke actually portrays himself, which is that he doesn’t really have this much of an ego. The literal translation of this line is that he calls himself “your cute little junior”, but even the more liberal translation used here doesn’t quite work with Daisuke’s character, since it’s not implied at any point that Daisuke thinks Taichi actually cares about him back the way he adores Taichi.

Again, Daisuke is an extremely deferential person who craves validation, and this is especially in the case of Taichi, who arguably is the one who creates the easiest mood shift in Daisuke for the early parts of the series. Whenever Taichi is nearby, Daisuke immediately becomes deferential and respects literally everything he does.

Observe Daisuke’s very resigned and very deferential facial expressions and attitude in 02 episodes 8 and 10, whenever it comes to Taichi (and note that the third screenshot here also comes from a situation where Daisuke wanted to advocate for pushing forward instead of retreating; it was that easy for Taichi to shut him down). For all it’s worth, Daisuke’s never really shown to have a lot of pride in himself (beyond the occasional joke), and it’s heavily implied that he sees Taichi as so amazing that he’s not even remotely in his league. That’s why it’s such a big deal that Daisuke puts his foot down and protests against what Taichi wants them to do in 02 episode 39, and it’s not even rudely or aggressively (he still uses polite Japanese!) as much as just firmly “I have a friend and I need to help him, I’m sorry.”

During the chapter, Daisuke claims that he doesn’t want to go back and meet his friends, because he doesn’t think they care about him, but, well, again: Daisuke is someone who craves approval. It’s somewhat understandable that he’d maybe have some degree of insecurity that they don’t like him as much as he wants them to, but the series by this point (remember, we’re talking episode 22, given XV-mon’s appearance) makes it very clear that Daisuke is well aware that his friends like him this much, and he has no real grudges against them.

This is one of the reasons it’s so important that 02 had so many scenes of the kids just...bantering in the computer room, or having tons of “free time off hours” that had nothing to do with Digimon fights, because although Daisuke is brash and rough around the edges, otherwise, the group of friends here get along perfectly fine. Once the stress of fighting is removed, these kids are part of each others’ social circle and love hanging out for the sake of hanging out, and even someone as dense as Daisuke should know very well that they do at least like him this much.

And, more importantly, whatever Daisuke might think about what his friends think of him, he himself likes them a lot. He cares about them a lot. Even all the way back in 02 episode 10 and 11, with Miyako and Takeru (whom he ostensibly banters and gets touchy with a lot), he still makes it clear he likes what Miyako’s doing and wants to check on her (without prompting), and later, when he gets in a fight with Takeru, he blames himself for not understanding Takeru’s feelings instead of feeling inclined to blame it on him. (In fact, this so-called hostility with Takeru is really overblown here, because there’s no reason Daisuke should think everyone takes Takeru’s side; when they did get in a fight in 02 episode 11, everyone was more concerned about getting them to calm down than they were about taking sides, because both of them did have a very reasonable position.)

And while Daisuke getting set off by the Takeru and Hikari issue might have been in-character at one point, it’s not for him at this point in the series, because 02 episode 22, the very episode that introduces XV-mon, has him take a completely different view of the situation:

Daisuke had already gotten over a lot of it by this point. The last time he shows any indication of Takeru and Hikari having ~something going on~ to the point he suspects Takeru of being an obstacle is all the way back in episode 17, which oh-so-coincidentally happens to be the same episode where he later learns about the truth of his seniors’ great adventure in 1999, and therefore receives the full context of why Takeru and Hikari knew each other beforehand (which they had been absolutely terrible at elucidating for 17 episodes). By the time we get to this epsode, Daisuke does not hold anything against Takeru himself, and he doesn’t even accuse them of having a thing, just moping that they “get along so well”. He’s not angry about it, he’s sad about it, and it’s heavily implied that he’s really just sad about being third-wheeled more than anything.

It’s also important to realize that this is long past the point where Daisuke would have shown any outright hostility towards Takeru at all. At worst, he maybe scoffs “do whatever you want!”, or ends up a little sad that they’re leaving him out, but he ends up putting this on himself more than he ever lashes out at others about it anymore. The grudge against Takeru had already gone long under the bridge, by this point Takeru is just a friend that he likes reasonably well and is sad to be third wheeled by, and it’s only 13 more episodes before he’ll stop bringing his crush on Hikari into the issue for the rest of the series.

And, remember, Daisuke has always been someone who does things “because other people are being hurt”. He’s not actually that selfish! Whenever people are really in trouble, he goes in to help them -- remember, back in 02 episode 8, he was crushed because Ken turned out to be the Kaiser, and someone indirectly trampling on the dreams of all the soccer-playing kids in the country. Had this been Daisuke from the anime, he probably would have immediately wanted to go back the moment he realized there are people in need and hurt left behind, regardless of his own feelings on his relationship with his friends.

The rest of the chapter is fairly on-the-nose, with Daisuke managing to create a “miracle” through the power of his feelings by remembering what it meant for Taichi to give him his goggles, and for managing to connect to his friends despite them being trapped, with Daisuke and Taichi eventually parting on good terms and Daisuke even getting the honor of doing the victory dance with him. This is why I want to emphasize (I’ll say this in bold) that I do not think this is a “bad” chapter just because it’s not compliant with Daisuke’s anime characterization. Given what the chapter sets out to accomplish, setting up a story of someone who feels neglected by his friends and eventually decides to reach out to them with his own feelings, it’s thematically solid and well-plotted out as a story, and the crossover and thought experiment of how Daisuke would react to an alternate version of Taichi is very entertaining. Plus, Izawa’s writing and Yabuno’s art is charming, and it’s lovely to see the 02 kids in this style.

It’s just, well, the entire premise of this chapter relies on a conflict generated by Daisuke being a character he is very much not. And, again, it’s not something that I can really criticize Izawa and Yabuno for; Daisuke’s quite the deceptive character, and it really doesn’t seem like Toei and Bandai gave them a lot to work with, especially since this chapter only works within a very narrow range of 02′s timeline, between 02 episodes 22 and 25, when V-mon can evolve to Adult but Ken hasn’t formally joined the team yet. (And in fact, I’d generally apply this sort of caveat to things relevant to Daisuke that come from the Bandai side instead of Toei side; too many things out there seem to only really be working with the base details of “Taichi’s junior who has a crush on Hikari” with no regard to the actual nuances of his character.) Personally, it seems that Izawa and Yabuno did their best with what they had to work with, and they even made it a fun chapter while they were at it! -- so I would simply say that it’s probably best to enjoy this chapter without thinking about the lack of canon compliance too hard, but also not to judge the actual anime version of Daisuke too much by this portrayal.

#digimon#digimon adventure v tamer 01#digimon adventure 02#motomiya daisuke#daisuke motomiya#shihameta

53 notes

·

View notes

Text

After the End (Again)

Despite all the words I’ve poured out on the subject, I don’t think I ever completely cracked Hussie’s endgame.

One year out from the Epilogues, and the question of what The End of Homestuck means feels even more complicated.

Granted, there’s a lot I feel like I understand (I’m so happy to see most of the fandom be on the same page about stuff like Dave’s arc or the meaning of the Gnostic references), but Hussie’s goals for the original end of the comic remain elusive, much like the man himself. Possibly deliberately. I’m eagerly looking forward to his final batch of commentary, where, in many years, we’ll finally get his own take on the subject. Probably.

I saw someone say recently that the Epilogues improved Homestuck – that as an ending, Act 6+7 is incomplete, and relies on the Epilogues to give Homestuck a definitive final statement.

On the other hand, I’ve also heard plenty of people say that the Epilogues ruined Homestuck, altering its final meaning to something unrecognizable.

Maybe there’s a way to make sense of both of these things?

The more time goes by, and the more I read of Hussie’s own thoughts on his work, the more I become convinced that Homestuck’s central thesis is the rejection of existing narratives. Or, to put it in other words: Fuck clichés.

This takes many forms, from Dave’s “there’s a vampire in the closet oh fuck get in the minivan” riff to Hussie’s emphasis on women as active drivers of plot to Dave’s own rejection of toxic masculinity. It’s also the main plot arc of Act 6 + Act 7: we escape Lord English, controller of the total narrative.

But these inherited narratives are insidious things. It’s hard to escape their hold over our brains. We live in a society, even when we start all over and try to build a new one. We might, for instance, see someone echo the same toxic ideas about authority and power out of a feeling of necessity. So the theme of the Epilogues is Act 6+7’s theme inverted: how are we still bound by these narratives?

From Divine Comedy to Divine Tragedy, revealing and reflecting each other.

My feeling is that Hussie wanted to express both of these things as Homestuck entered its final stages. He chose to tackle one, wait a while, and then tackle the one that was far more difficult to render compellingly.

This is how I make sense of the utopian, gnostic themes of late Act 6 + 7. They present a sincere aspect of Homestuck’s message: tear off the ideological chains of your mind. Transcend to the Pleroma. Build a new world. But this Gnostic hope was always going to be followed up by a statement on the difficulty of doing just that. For the power of the Demiurge is great, and his illusions deeply rooted in your mind.

I used to get in all sorts of debates as to whether Act 6-6-5-Act 7 (Ending 1 of Homestuck, if you will) was good or bad. Maybe that’s not the right question, though? Maybe it doesn’t matter anymore, or it never mattered.. I think it would be kind of impossible to tell, anyway. Because what Hussie left us with in 2016 was a thick stew of fascinating ideas to dig into and discuss and try to understand. Act 5 was a mechanical puzzle, challenging us to figure out how the world of SBURB worked; Act 6 a thematic one, challenging us to become better readers who engage with Homestuck’s metaphors and themes. Given the level on which we understand these things now, I think we resoundingly succeeded.

And when we started to ask the right questions, then—only then—were we ready for the Epilogues.

It’s true that the Epilogues have a certain feeling of primacy now. That’s inevitable, given their role of deepening the conversation and their at times shocking content. But I think it would be a mistake to read them as more important than the first ending.

Because I think Homestuck genuinely believes in the importance of that escape. The other reason for that three-year pause? Maybe it was to give us time to draw our own conclusions. Both in the sense of wrapping our minds around Hussie’s thematic puzzle, and in the sense of creating our own stories to follow the ending. Because if English’s narrative, aka Homestuck, is the thing we’re escaping from, then to follow the gnostic vision of escape is to enter the Pleroma of fan creation. The actual, canonical nature of Earth C is a multiverse of fan interpretations, reaching in every different direction, many of them offering hope, a utopian society, and/or the possibility of major growth for our characters. Those didn’t go away after the Epilogues. For my part, I read quite a few Davekat fics that still stick with me after all this time, informing how I understand the characters. Guess what? Homestuck explicitly grounds them as significant.

To put it in Rose’s terms, these timelines and stories may not be essential, but they are true and relevant.

Now, fandom is not perfect. (Understatement of the century.) Fan writers hold onto clichés and toxic narratives as much as anyone. One of the goals of the Epilogues is to offer a counterpoint to that vision as well—to show the dark side of redemption arcs, marriage proposals, and coffee shop AUs.

But at the same time, the three-year feast of storytelling made possible by the Final Pause remains an important, and explicitly heroic part of the Homestuck multiverse.

(It’s been a treat to see how the community has responded to the darker points raised by the Epilogues as well. A great example is Sarah Zedig’s Godfeels series, which returns to the idea of Earth C as a place of meaningful growth and change (for June Egbert, especially), but recognizes the difficulty of making that change when the people you know are stuck in their own ideas of what the world should be. I’m looking forward to reading more works in this vein going forward.)

All this suggests an intriguing possibility: that the dissatisfied feelings many walked away from the original ending with may have been deliberate. Not to say that there aren’t some pretty satisfying arcs in Act 6. But perhaps some were left open and ambiguous, even frustrating, on purpose: to point us in the direction of filling those gaps. Fertile, untilled ground for the fanonical imagination.

Is that good storytelling? I have no idea. What I do know is that there’s nothing else like it out there.

And honestly? I’m really glad something as weird as Homestuck exists.

And that we get to be a part of it.

<3 Ari

#act 7#the epilogues#gnostic influences#homestuck analysis#escaping canon#the endgame#fanon metaphysics#earth c#utopian themes#things i'm still thinking through#the importance of writng fanfiction#inherited narratives#fuck cliches#feast of homestuck 2020

52 notes

·

View notes

Text

Some personal Akatsuki ramblings

I rarely talk about Akatsuki herself in length -- usually when I’ve spoken about her in the past, it was about her role in the story as it pertains to Shiroe. I have a draft for my character analysis of her that’s been rotting away in my drafts for like, 2 or 3 years now but I’ve never been able to finish it. (I know what’s to come in future volumes, but without an official translation, I’m hesitant to take my own Google Translated-interpretations at face value.)

Some of this will be quite personal, maybe a bit controversial as well, so I’m keeping the bulk of it under a read more. (Mobile users... sorry.)

One thing that has slightly bothered me over my past few years in the LH fandom is how often Akatsuki gets reduced to either “best girl” or “failure love interest who sees a middle school girl as a rival”. Of course, there’s nothing wrong with liking Akatsuki for her awkward quirkiness, or disliking her because her insecurities (and the character arc resulting from it) are rooted in a rather unrealistic character gimmick (somehow looks like an elementary schooler as a college student?). But I think it’s completely overlooking the root reason why Akatsuki is the way she is.

While I initially had a negative reaction to volume 6 when I first read it, after time (and an official translation), I’ve found myself intensely relating to Akatsuki’s situation. Though I’m not completely qualified to speak about this and would like some insight into the matter from people with more knowledge/experience in the subject, it seems to me that Akatsuki may in fact be autistic (or at the very least, neurodivergent in some form).

I speak from the perspective of a (maybe) neurotypical person (more about that later), so perhaps someone would disagree with me. However, I think Akatsuki’s awkwardness is rooted in something deeper than mere “she isn’t good at talking,” which is where most people find her relatable and then stop there.

In volume 6, she explicitly says that she’s never had friends her own age. When she gets grilled for her lack of communication, she bemoans the fact that she doesn’t know how to express her feelings and can’t just show people what she’s thinking. Even Shiroe points out in volume 5 that they have difficulty keeping conversations going, and after he asks her to provide a conversation topic when she protests this, she comes up short.

Akatsuki’s almost hyper-focus on the master-ninja roleplaying (which Shiroe also explicitly gets weirded out by, and cause other characters concern) seems in line with the “restricted interests and repetitive behaviors” often found in those with autism. Whenever Shiroe tries to gently suggest he’s not interested in his role in their assumed roleplay, she digs her heels in and he gives up -- perhaps an example of “trouble understanding another person’s point of view,” another trait common in those with autism.

So, what’s that all got to do with me? Well, simply put, I saw a lot of myself in Akatsuki. The difference between series I’m intensely interested in (special interest/hyperfixation?) and ones that I casually like are like day and night. For series that I’m truly into, my interest spans several years, and usually involves maintaining or aiding a wiki about it or otherwise having blogs devoted to analyzing it thoroughly. It ends up eating at my time and my attention to my own detriment, and as William later says in volume 7, I even think about it when I eat and when I shower. This line in particular hit home:

Akatsuki had been avoiding the things she really had to do. She’d worked desperately at only the things she liked doing, and had tried to convince herself that was effort.

Oftentimes, I know what I have to do. My homework, my job search, networking with people, building relationships. But if it doesn’t interest me, no matter how hard I push and pull at it, I end up going back to the things I like doing or thinking about. Sometimes, I don’t even like what I do, I just do it because it’s something I can do.

My lack of communication skills is also much like Akatsuki’s. It’s not a casual “lol what even is talking to people”; reading Akatsuki’s introspection and seeing things from her point-of-view felt like I was seeing things through my own perspective of the world.

I don’t know how to express myself and sometimes, I don’t even know if there’s something to express. I can be “my way or the highway” to the point where it’s driven people away. I can’t keep up a conversation and I’m perfectly content with not talking with others. I find small talk inane and people casually conversing with me (whether they’re strangers or friends) puts me on edge.

When Akatsuki struggles to express familiarity with the other girls, it takes Rayneshia declaring her a friend to give her the words to speak. Throughout high school, there were only a few people I can definitely say was a friend. Everyone else, I could never get a read on. Did they consider me a friend? Was I an annoyance, or was I just wallpaper in the backdrop of the school? I was rarely ever anyone’s “first pick” for anything and I usually stayed to myself as to not cause trouble for anyone; I learned in middle school not to stick myself into already-established friend groups.

In a lot of ways, Akatsuki probably felt the same about the Watermaple group. She was there on Shiroe’s orders, not because the other girls there liked her. So in her eyes, the greatest courtesy she can do is eliminate the threat on her own... which she fails to do.

What makes Akatsuki even more relatable is that she isn’t explicitly autistic; Mamare has never spoken about whether his characters are societal commentary (though personally, I think they are). The most he’s ever said about them is that he tries to make them like people he knows.

Maybe Mamare isn’t even (fully) aware that Akatsuki was written in this way. Perhaps he wrote her thinking “someone out there will relate to her.” And he’s right. In a way, not making her (possible) neurodivergence solidified canon is what makes her even more relatable to me.

As a result of my Chinese-American background, the sort of cultural perspective on neurodivergence I’ve been raised in is, to put it bluntly, “Well, tough.” If you don’t have a severe disability, that means you don’t have a disability, and you better damn well act like a normal person. (For some measure of “normal” that I have yet to figure out.)

Things like autism and developmental orders were treated as something for “others.” In fact, for most of my elementary through high school years (I lived in a predominantly white neighborhood), I genuinely thought autism and ADHD were a white people thing. To be fair, given some cursory research into the general view on autism in China and Japan, they probably think so too -- if they even know about such things at all.

A fair number of the general populace seem to be unaware of them; I’ve seen Japanese tweets spreading awareness about ADHD on twitter, and a JP twitter mutual had a mental breakdown as a result of their ADHD and anxiety making them unable to perform at work. It makes me wonder if Akatsuki exhibits autistic traits because Mamare knows people who act similarly (or perhaps, he can relate to them himself), but none of them actually know that there’s an actual underlying reason and it’s not a mere relatable personality quirk.

So in the end, I have absolutely no idea whether I’m normal or not. I can’t tell if I’m actually neurodivergent or if I’m faking it to make an excuse for myself. I’m Akatsuki as she watches Minori and Shiroe at the end of volume 5: feeling helpless, knowing that our juniors are “ahead” of us and “more successful.” We want to push our ineptitude on our inexperience and our sub-par equipment, but what we’re really lacking is interpersonal skills and, even though we know that’s what we’re missing, but we have no idea how to work on that.

31 notes

·

View notes

Text

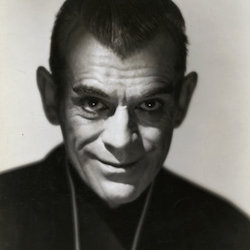

Boris Karloff: Creature Comfort

Not many actors paid their dues for as long and as hard as Boris Karloff did. Born William Henry Pratt near London in 1887, he was the self-described black sheep of his family (both of his parents were Anglo-Indian). In a photo at age three-and-a-half, he already looks alarmed by something, or by someone.

Pratt traveled to America to become an actor and changed his name so as not to embarrass his family. He played on stage in stock and learned through make-up how to become any character he wanted to be, much as Lon Chaney did. In between plays—and later in between films in the 1920s when he was slotted into many small and usually villainous roles—Karloff had to sometimes work as a day laborer or ditch-digger, which meant that he had problems with his back when he was an older man.

His 1920s villains were usually of Arab or Indian extraction, and his staring eyes and molded features lent themselves to glowering wickedness. Karloff very often didn’t get enough to eat in these years, which added to his impression of aesthetic gauntness. As a mesmerist in The Bells (1926), his best part in silent pictures, Karloff does mesmerize with abrupt gestures that he somehow slows down even before we have taken them in. Just watch the way he manages a very false slow smile, moving the corners of his mouth up and then tossing the smile contemptuously away. This shows an actor in tune with what the camera needs, and what it needed from him was menace.

What made Karloff such a distinctive screen player was the slow, lingering way he moved through space, which created its own atmosphere of dread. In Howard Hawks’s The Criminal Code (1931), which he had played in on stage, he is a convict named Ned Galloway, a man bent on revenging himself on the stool pigeon who got him sent back to prison just for taking a drink. Karloff has a way of suspending his words here—creating a whole little protective world around them—but it is the slowness of his movements that really makes the strongest impression.

Stealing up on the stool pigeon, Karloff approaches this man with slow and almost slow motion physical grace. The man turns and sees him and gives a start, and Karloff gives his own little start, as if to say, “You’re done for, and you must accept it.” There’s something almost tender about the way Karloff does that, something lyric and inevitable, like a movement out of a Martha Graham dance.

It is this skill in silent movement that would come to the fore in the part that finally made Karloff a star at age 44, the creature or monster in James Whale’s Frankenstein (1931). The creature was given the brain of a murderer, yet he is new born, innocent, and untouched. Karloff always gave make-up artist Jack Pierce much credit for the look of the creature, but he himself suggested the heavy eyelids.

Karloff had to make the full imaginative leap into the creature’s point of view in Frankenstein, and he chooses to portray him as a very poetic figure. Lon Chaney, who was supposed to play the part before his untimely death, would almost certainly have been far harsher in the role, far more the re-animated man with a murderer’s brain, whereas Karloff’s later partner and rival Bela Lugosi, who had made such a hit earlier in the year for Universal as Dracula, would have been scary as the creature, maybe, but never touching (Lugosi actually turned the role down).

Karloff has an essentially gentle, dreamy sensibility, and he emphasizes the pure yearning of the creature, the way he reaches out for light and smiles when Little Maria (Marilyn Harris) gives him a flower. What happens next with Little Maria is the stuff of child nightmares, a scene that was almost always cut but now stands in most release prints: Karloff’s creature throws her into the water of a lake after he runs out of flowers to throw. The murder of Little Maria is only mitigated by the uncomprehending way the creature reacts when he tries and fails to understand what he has done to his little friend.

Karloff’s creature has anger, but it never seems to be the anger from the past life of the murderer’s brain in his head; it is always the anger at what he sees in the world and how he is treated, and it was Karloff who decided to play him this way. “The Monster was inarticulate, helpless and tragic, but I owe everything to him,” Karloff said. “He’s my best friend.” Karloff would remain the fastidious, colorful silk thread winding through the coarse, itchy fabric of the horror genre, and he stayed with it through many incarnations and revivals.

He played a twitchy gangster for Hawks in Scarface (1932), and there his acting seems a bit old-fashioned and external, a mark of the stock theaters he’d played in as a younger man. Karloff is given a big build-up in the credits of Whale’s The Old Dark House (1932) and top billing, with a title card trumpeting his “great versatility,” but he was limited by his looks and demeanor.

It’s hard to imagine Karloff playing something like Alec in David Lean’s Brief Encounter (1945), or anything so romantically straightforward. In The Old Dark House, Karloff is a drunken and mute brute of a butler with a lech for Gloria Stuart, a straight man in a semi-spoof for the first of many times to come, and he brings some genuine menace and fear to the screen in between the campy laughs of that film.

He was billed as just “Karloff” now, like “Garbo.” He played The Mummy (1932), an Egyptian man buried alive and still seeking his love, and this was a feat of make-up and his slow vocal delivery. Over at MGM in The Mask of Fu Manchu (1932), Karloff is forced into a camp mode himself, for there is no other way to play the absurd and racist script of that film. “Boris was a fine actor, a professional who never condescended to his often unworthy material,” wrote his on-screen daughter in that movie, Myrna Loy, in her 1987 memoir.

After scads of work for years (he had 15 credits in 1931 and nine in 1932), Karloff slowed down and went back to England for the first time in decades, where he was reunited with his family and made one picture there, The Ghoul (1933). He made several movies with Lugosi, including Edgar Ulmer’s The Black Cat (1934), and there was no feeling of rivalry between them, at least from Karloff’s side. His films with Lugosi could get pretty gruesome, with characters skinned alive and vindictive plastic surgery and other things to bring about the shudders and the heebie-jeebies.

“Poor old Bela, it was a strange thing,” said Karloff of his screen partner in an interview in 1964 for Films in Review. “He was really a shy, sensitive, talented man who had a fine career on the classical stage in Europe. But he made a fatal mistake. He never took the trouble to learn our language…He had real problems with his speech, and difficulty interpreting his lines.” Karloff was aware when his films were poor, whereas Lugosi didn’t seem to be, which makes Lugosi a lesser actor than Karloff but also somehow scarier because of this lack of awareness.

Karloff was a religious fanatic in John Ford’s The Lost Patrol (1934) and an anti-Semite in The House of Rothschild (1934) with George Arliss, but the public clamored to see him in more horror. He returned to the creature in The Bride of Frankenstein (1935), where he went deeper into the Monster’s conflict between self-protective and even outright malicious urges and a vulnerable reaching out for beauty and love, and friendship. “Alone bad…friend good,” the creature says here, after being befriended by a blind hermit. (Karloff didn’t think the creature should talk, but he was persuaded otherwise.) Karloff’s creature even sheds a tear after deciding to blow everyone up because he has been rejected by his hissing bride (Elsa Lanchester).

Censorship helped to bring an end to the first cycle of horror movies, and so budgets for Karloff films plunged while he played many a mad scientist, his intensity and trouper’s belief rarely wavering in the grind of similar and often threadbare material. He tread a fine line between threat and camp threat, and few players can equal Karloff for pure stamina. Surely he must have sighed sometimes as he got script after script along the same lines, so that it is difficult to tell one of these films from another.

Karloff was reduced to appearing at the poverty row studio Monogram by 1938 but returned to his creature one last time in Son of Frankenstein (1939). He was a man who “looked like Boris Karloff” in the comedy Arsenic and Old Lace for years on Broadway and missed out on the film version because he was still playing it on stage.

Even his patience had some limits. He was scornful of the monster mash House of Frankenstein (1944), and he was vocal about the fact that producer Val Lewton subsequently saved his soul as a performer in a series of low budget, intelligent movies beginning with The Body Snatcher (1945), where he dug up graves himself as once Dr. Frankenstein had dug him up. Lewton allowed Karloff to play three-dimensional people rather than the cardboard cutouts he had gotten used to, and he responded expressively, with lots of careful, poetic character shadings.

There were some changes of pace after World War II for Karloff. He steals Douglas Sirk’s noir Lured (1947) in his reel as a demented and embittered fashion designer, which stands out in his career for its sheer unexpectedness. This film showed his skill at being slightly funny and also fully menacing all at once, which he also needed for the awkwardly titled Abbott and Costello Meet the Killer, Boris Karloff (1949). Karloff often had better luck with parts on stage than in movies in his later years, scoring as Captain Hook opposite Jean Arthur in Peter Pan and winning a Tony nomination for his work in The Lark, which starred Julie Harris as Joan of Arc.

On TV, Karloff had his own anthology series and also played Kurtz in a 1958 adaptation of Conrad’s Heart of Darkness for Playhouse 90, realistically and stirringly shuddering about the horror he has seen, and he was the voice of the Grinch in the much-replayed animated special How the Grinch Stole Christmas.

A TV program called Shock Theater re-ran Karloff’s old horror films, and this brought him into the nightmares of Baby Boomers who are still scared by the thought of what happens to Little Maria, or by The Mummy. His program pictures became a staple on television, for they featured those baleful eyes and the hypnotic, soothing voice that could send late-night TV watchers off to sleep sure of a nightmare or two involving the supposedly dead and the supposedly living.

Karloff was in very ill health in his last years, but he still liked to work, finding himself in some campy horrors for producer Roger Corman that co-starred Vincent Price, Peter Lorre, and a young Jack Nicholson. The gravity of his face and voice were undiminished by time or poor assignments, and he brought some human dignity and feeling to nearly everything he did.

Karloff played a vampire for Mario Bava in Black Sabbath (1964), and then he was given an affectionate and knowing swan song by the young cinephile director Peter Bogdanovich in Targets (1968), where he played Orlok, a retiring star of horror films. “Do I have to say such bad things about myself?” he asked Bogdanovich, fully aware that Orlok was based on his own image. Bogdanovich reassured him that audiences would disagree when Orlok calls himself a relic, but Karloff wasn’t so sure. He is maybe a little uncomfortable with the meta aspects of that film, but he was a good sport about it.

“He really was a gentle soul,” said his only daughter Sara for a TV documentary. “I don’t think he scared anybody, not in real life.” Karloff was a very generous man and very loath to have that talked about (look at the horrified way he reacts when something generous he had done was mentioned on the This Is Your Life show in the late 1950s). By the time he was finished, he had 207 credits, some of which were only being released after his reported death. Surely some real life mad scientist somewhere might one day re-animate him for us.

by Dan Callahan

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

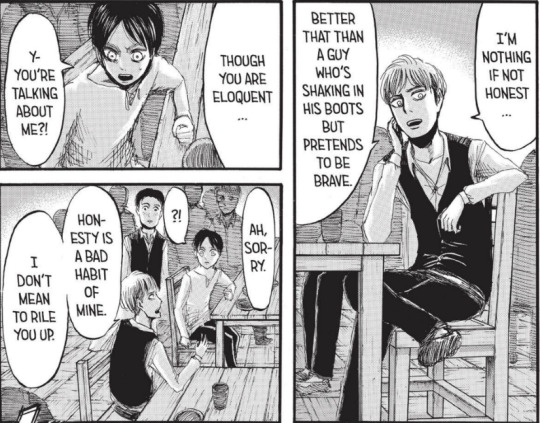

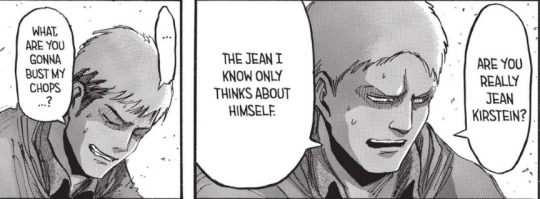

@mirandafandomette Yup! In this booklet that comes with an Armin figure, it says that “Jean dislikes that Armin is always together with Eren.” As we’ve already talked about on chat (but I haven’t talked about it on my blog before, so I’m gonna use this comment as a jumping off point, thank you lol), this booklet’s canon status vis-à-vis the manga is questionable, but I think it’s a defensible interpretation to say that Jean is at least slightly jealous of Armin and Eren’s relationship in the manga. However, I think Jean primarily dislikes their closeness because he thinks Armin underestimates his own skills as compared to Eren’s. And Jean is right, in a way, as we know from the Trost arc–Armin is surprised at the faith that Eren and Mikasa have in his abilities, worried that he’s primarily been a burden to them. The way I read it in the manga, it seems that Jean wants to be close to Armin himself, but in a way that he feels is more genuine and equal than the manner in which Eren and Armin relate. (I’m not taking a stab at Eren and Armin’s actual friendship here, only attempting to explain Jean’s initial understanding of it!)

The rest of my analysis is under the cut because I’m long-winded and I like pictures ^^’

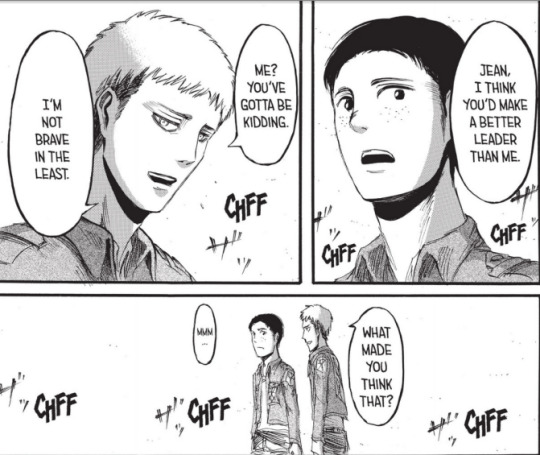

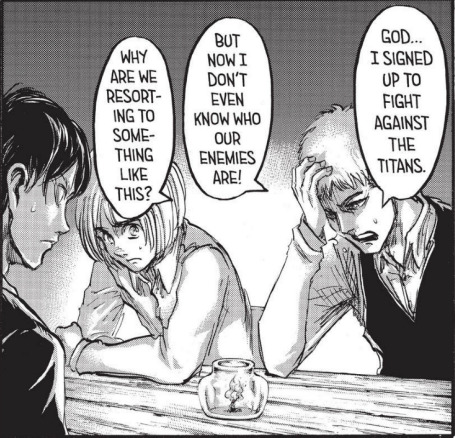

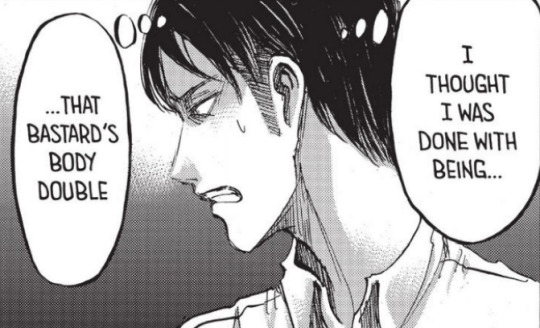

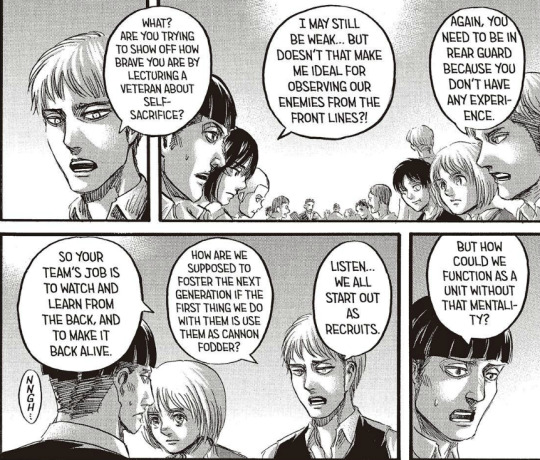

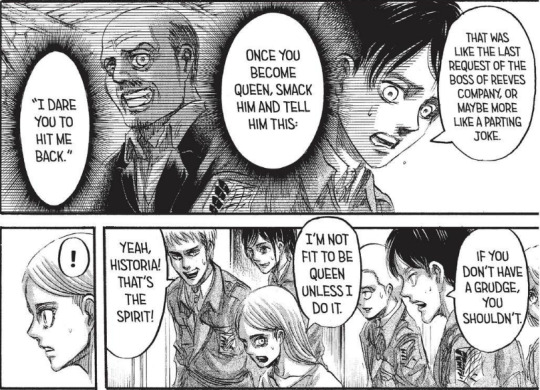

To begin, I’m pretty sure the booklet is making a direct reference to the following scene from chapter 23:

Now, I know these panels have caused a lot of discourse, and I’m probably getting myself into hot water by bringing them up, but I feel like I eventually have to address them as a Jean/Jearmin fan (just like I inevitably had to talk about chapter 53 …), so here goes nothing.

This scene poses a lot of difficulty of interpretation because it’s translated slightly differently each time I see it. This screen grab is from the official English translation of the manga, and it seems to be riding a pretty hard line between Jean calling Armin a sycophant who depends on a guy when he doesn’t need to, and Jean essentially saying, “No homo, like you and Eren, but you’re a pretty legit dude.” “Creeped out” and “fawn” are quite ambiguous words, and (according to a friend who reads Japanese) they’re reflecting a similar ambiguity in the original text, although most of that polysemy is apparently generated by Jean using “rude conjugations”. The gist of her reading is that she can’t definitively say Jean’s language is homophobic, but she also can’t rule it out as a possible meaning. However, the English dub of the anime (and my friend confirmed that the Japanese is the same in the anime and the manga for this scene) translates Jean’s comment as, “It always bothered me how you clung to Eren like a security blanket, but I always knew you were brilliant.” I think, based on the second half of Jean’s statement here and after consulting with my friend, that this is an equally defensible interpretation of Jean’s words. His line “I always thought you were capable” implies that his first comment is mostly about Armin relying on Eren when he really doesn’t need to; Armin is very capable on his own, and Jean sees this about him. And Armin’s response almost seems to affirm Jean’s assessment because, according to my friend, he’s also using rude speech forms! He rises to the occasion and meets Jean banter for banter. In the words of my Japanese consultant (who, I should say, doesn’t read or watch Attack on Titan), “Wow, they’re really going at each other!”

So, keeping all of these difficulties about the language in mind, how should we interpret this scene? I’ve seen several different readings of it, but I don’t think I’ve seen one that totally captures all the nuances at play here, so I’m going to try my hand at it. Jean is saying that he is disturbed a capable or “brilliant” soldier such as Armin would waste his time on a guy like Eren–so this comment is kind of a dig at Eren too. At this point, Jean just doesn’t get Armin and Eren’s friendship, and suggests that Eren doesn’t deserve Armin’s attention. He expresses himself in strong language, in a way that implies there is something extreme about Armin’s devotion to Eren. In the manga translation there’s an implication of a romantic interest on Armin’s part, and in the anime translation Jean suggests that Armin’s reliance on Eren is childish. I prefer the anime translation in this case because I think it also speaks to a broader criticism of Eren that Jean has: that he’s not thinking of the way his choices hold back his childhood friends, who are both more capable than Eren in someways.

Chapter 3.

When this critique is turned on Armin for following Eren instead of Eren for leading a friend astray, the accusation becomes that he is hero-worshiping Eren at his own expense. I recognize that “no homo” is still a possible valence of this moment, but I think that doesn’t account for the full meaning of the sentence: even though you devote your efforts to Eren’s causes, your capabilities actually exceed his. Whether or not we fully agree with Jean’s assessment, that appears to be the sentiment behind his words.

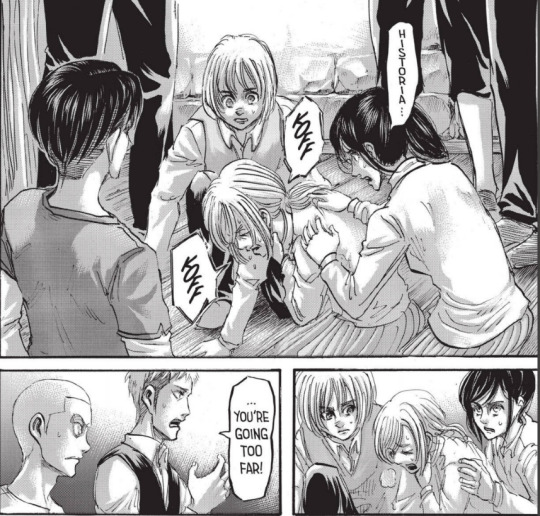

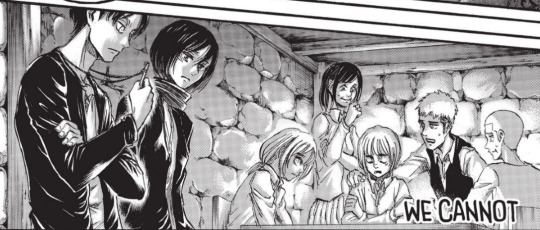

There’s further context for interpreting this moment to be found in Reiner’s reaction to Jean and Armin’s exchange.

Throughout this whole conversation, Reiner has been commenting on how supposedly selfish Jean Kirstein has suddenly starting thinking about others and acting like the member of a team. Here we get a rare personal reflection from Reiner on the change in Jean, seemingly triggered by his conversation to Armin: “Jean really is different.” Given Reiner’s response here, I think we should read Jean’s comment to be intended as a compliment, even if it comes out in a really backhanded and problematic way. Does that absolve Jean of his rudeness? No. But it gets at the core meaning of his words: he respects Armin despite the fact that he’s a confidant of Eren, Jean’s ideological rival. And in order to have come to such an opinion of Armin, Jean had to be observing him. Jean has revealed to Reiner that he has been paying more attention to his comrades than he previously let on, that he actually has respect for some of them, and that he’s willing to assist them when they need it, even at great personal risk (ex: the whole “distract the Female Titan” plan they’re about to execute).

And perhaps we can read some jealousy in this moment too. Jean thinks Armin is too capable to be relying so much on Eren. I think, based on later scenes of Jean and Armin’s burgeoning friendship–a development which is spurred by Jean continually seeking Armin out to debate morality and strategy–that we can interpret Jean as jealous of Eren having such a talented friend, although I think it would go too far to say that Jean wants Armin to “fawn” over him like he thinks Armin “fawns” over Eren (even for a shipper like myself, I don’t think Jean would want a romantic relationship where there was a lot of fawning; it might feel disingenuous to him). Jean admires both Armin and Mikasa, and doesn’t seem to want to become their Eren so much as he wants to build his own kind of relationships with them. He sees their relationship to Eren as unequal somehow, with Eren under-appreciating their talents and support, and thoughtlessly leading them into serious danger. So I believe he is jealous of their closeness, but not wishing for them to see him exactly as they see Eren.

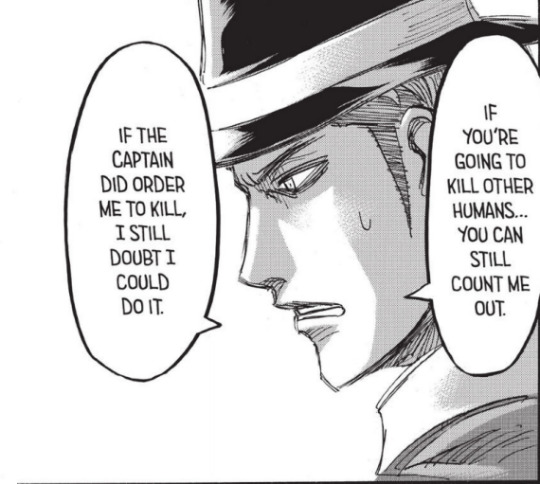

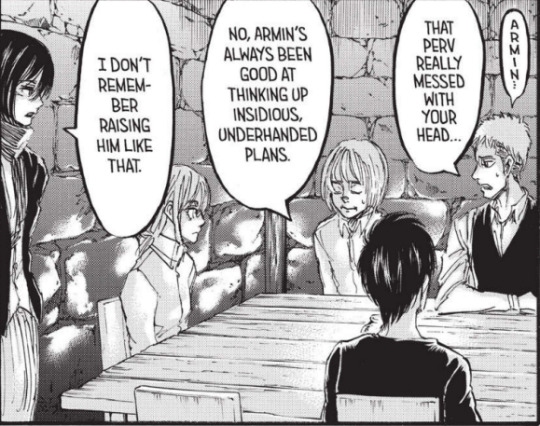

As a final thought to wrap up these ramblings, Jean also seems to have a peculiar way of expressing affection for Armin where he jokingly insults him. We see him speak this way to Armin at least twice more, once at the beginning of their friendship and again when they are closer.

Chapter 33.

Chapter 82.

Although Jean seems comfortable openly expressing his admiration for Mikasa, he tends to qualify his praise of Armin’s brains with tongue-in-cheek digs at his intelligence. This is probably due to their genders; while Jean does appear to be comfortable showing more physical affection to Armin than his other male friends, he struggles sometimes with open verbal affection. And so they have this repartee, their own particular way of communicating within their friendship that does, indeed, differ from the way Eren and Armin interact. Although there is clearly mutual affection between them (and Jean takes such care of Armin’s emotions, but that’s a subject for another post), there’s also a semi-ironic lack of “fawning”–Jean’s admiration and care for Armin is palpable, but he jokes that he’s not fawning, nope, not even a little bit! We can see here that Armin understands his meaning from the way he smiles … and Armin must feel some guilt about how he’s about to sacrifice himself for a victory at Shiganshina.

Okay, so to try to tie all of these seemingly disparate observations together into a coherent conclusion: Jean initially dislikes Eren and Armin’s closeness because he feels it undermines Armin’s own talents; he probably feels jealousy over the fact that someone like Eren has such a capable friend like Armin, even if he doesn’t want to have the same kind of friendship with Armin as Eren does; his distaste for “fawning” (even if we do want to interpret it as a homophobic dig) does not necessarily mean that his attraction to Armin does not have the potential to be romantic, only that he distrusts elaborate expressions of affection and possibly has some internalized homophobia; and that this scene fits into a pattern of Jean expressing his respect and admiration for Armin with ironic insults.

#replies#mirandafandomette#jean kirstein#armin arlert#jearmin#snk#snk meta#maybe i overread#and maybe i overthink my interpretations#i dunno lol#gotta consider all the angles#but i like my interpretation#i think i am right lol#tw: homophobia#just a bit of discussion of homophobia#but just to be on the safe side!

93 notes

·

View notes

Text

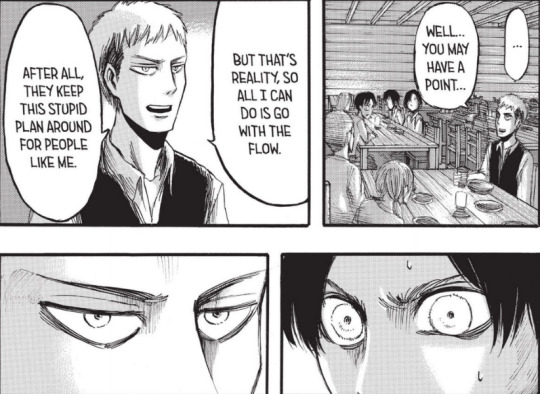

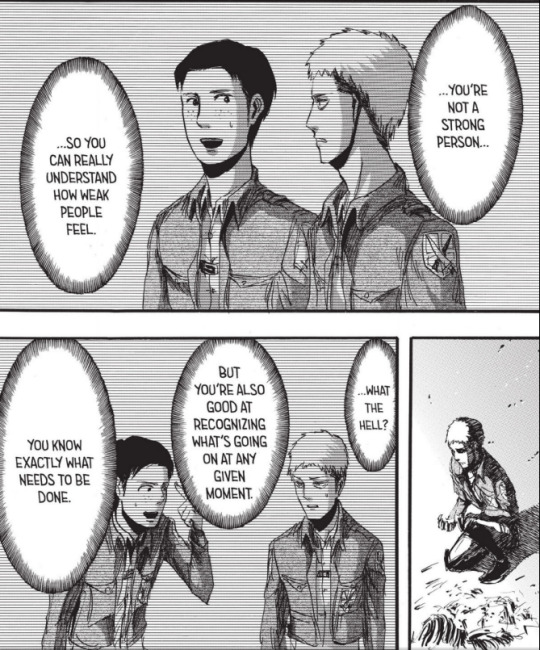

Some Thoughts Jean’s Character Development (Prompted by the HS AU).

CW: Bullying and the molestation scene.

So, in keeping with the rhetorical principle of kairos (timeliness of an argument), I think the time is ripe for a (re?)consideration of Jean Kirstein’s presentation in the Attack on Titan manga. I noticed that a bit of a discussion about Jean’s character popped up in the wake of the High School AU fake preview for volume 22 (one which I’ve already participated in a few times) and since we’ve just had a massive time-skip in the series to kick off the final arc, I feel like we can examine the development of the characters from the fall of Wall Maria to their journey to the ocean as discreet units. In fact, it may be useful to look at where some of them have ended up and how they got there before launching off into the new arc, so if you like what I have to say about Jean please send me suggestions for more character analysis like this!

The reasons I want to talk about Jean are twofold. The first is obviously personal interest. I’m discussing Jean regardless of whether or not anyone else really wants to read it because I find his portrayal and development intriguing xD. But my jumping off point is a little bit more specific, to come back to the question of kairos. The High School AU, however silly or tongue-in-cheek, has raised questions in fandom about whether or not Jean is a bully in canon or would be one in an AU that I would like to address.

Although I’m taking an AU’s depiction of Jean as the starting point of my inquiry, this post is pretty much only concerned with the canon material of the manga (not the anime: I have already discussed discrepancies between the manga and the anime’s portrayals of Jean here). Even though Isayama drew the High School AU and therefore it probably has value as meta, I feel strongly that the Jean depicted therein has little in common with Jean in the manga. I’ve been attempting to follow up on an interview which was mentioned to me, where Isayama supposedly said that in any other universe Jean would be one of Armin’s bullies (I’d appreciate any help in locating it! So far I’ve only been able to find other people mentioning it in their posts but no source). I find this kind of blanket statement on Isayama’s part a little bit more troubling—how did he come to understand his character this way? I guess it doesn’t matter to a certain extent, because authorial intent or understanding is by no means the end-all be-all of interpretation—and therefore I would like to further explore the question of Jean’s canonical presentation to attempt to answer the question: is Jean Kirstein ever, at any point, a bully?

My answer, as you may be able to guess from the fact that my blog is Jean themed, is a pretty hard no. In fact, within canon I would argue that Jean is one of the more empathetic and morally astute characters, and that the development he undergoes is less of a complete ethical realignment and more of an adjustment of his goals and strategies. He doesn’t begin cruel and transform into a kinder person; he starts off as astute but self-centered and his development revolves around using his skills to protect and champion others rather than just himself.

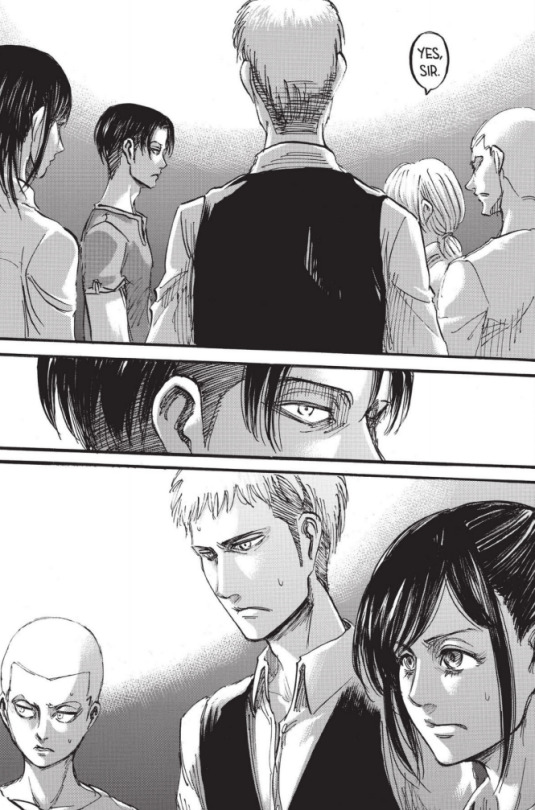

I would say Jean actually starts off as a bit of an outsider among the 104th (a facet of his personality that the original draft of the HS AU actually preserves) and that Eren generally has more clout than him; in fact, trainee Eren would probably not be a compelling target for a bully, all things considered. Jean’s fights with him don’t seem to come from a place of maintaining dominance over someone weaker and instead take the form of pretty mutual brawling. Indeed, he may be at a bit of a disadvantage when fighting against Eren physically, as demonstrated in this scene.

Chapter 3. Jean is “punching up” here, as it were. After a battle of words, Eren and Jean hit each other simultaneously and initiate a fight in which, according to Reiner, the odds may be slightly against Jean. Mikasa also implies Eren picked this fight after she intervenes. Also I just noticed that dude giving peace signs in the far left corner lol.

All in all, Jean is never depicted as picking on someone weaker than himself to establish dominance at pretty much any point in the series, as far as I can remember (in fact, he’s the only one to stand up to bullying in some situations, as will be discussed below). Isayama shows Jean hassling Marco, teasing Sasha, and picking fights with Eren (the first of whom has some pretty naive worldviews and the latter of whom give as good as they get and even start said fights). Jean’s so irritating to Eren--at least in the manga, I know they nerf him considerably in the anime--because he’s astute and quite often actually has a point. He’s not, unlike Armin’s bullies in the series, calling Eren a heretic for even thinking of going outside; rather, he seems concerned that Eren is going to drag other people outside to killed along with him (particularly Mikasa, initially). He can be rude and he has a short fuse but he’s not seeking people out to hurt them and enjoying it. He has a sore spot about Eren, but that’s really more of a fight between equals--they make each other mutually uncomfortable because Jean reminds Eren of the stakes involved in achieveing his goals and Eren provokes action from Jean.

In fact, I’d say Jean’s commitment to the truth aligns him a lot more with Armin than his bullies or even with the other members of the 104th. For instance, as this post points out, they both get themselves into trouble by speaking their minds as kids.

Armin in chapter 1 and Jean in chapter 16. I still can’t get over Jean calling Eren “eloquent”; regardless of Eren’s good intentions, I think Jean is very right in pointing out how Eren’s rhetoric doesn’t sound all that different from the story the higher ups told about the cull. But I also find it super interesting that there is no bad intent in Jean’s speech here; given the “truce” they call afterwards, I think he’s serious that he doesn’t mean to attack Eren. In the anime Jean doesn’t get this line about eloquence in and the scene is much more hostile.

Which brings me to my point about his development. The way I read it in the manga, Jean’s journey is not about transforming from a cruel person into a kinder one (since he is never depicted as cruel in the first place), but from a self-centered individual into a responsible one: specifically, a person tasked with championing the weak. Jean has always seen the problems with the government--he talks about the cull of twenty-percent of the population as a suicide mission, he pokes fun at the rhetoric of calling the people who are forced to settled in outskirt towns “heroes”--but instead of attempting to do anything about it his initial impulse is to play the system so that he survives as long as possible.

Chapter 17. They stand up to start fighting simultaneously immediately after this. Eren is sweating here, implying nervousness, and his eye is twitching; Jean’s pretty calm now, but in just a few panels his jealousy over Eren’s friends will get him into trouble.

In fact, Marco thinks Jean’s pragmatism and desire of self-preservation put him in a unique position to stand up for the weak--the opposite of picking on them.

Chapter 18. This memory comes to Jean when he’s trying to decide how best to protect his comrades from further death and devastation.

Marco’s point is that Jean has a unique combination of skills and personality traits which he can utilize to protect the weak, both from the titans and (eventually) other humans who are seeking to oppress them. Jean’s “weakness” leads him to value life, so he’s not going to take certain risks unless he has to--and he’ll be honest it about it with his soldiers, so they’ll know he has their interests at heart. He only makes sacrifices reluctantly, when he must in order to preserve a larger number of people (as seen in Trost). He’s also astute: he’s suspicious of empty rhetoric (like the government deals in--it’s so weird that Marco is the one implying some of this, given his fondness for the king; perhaps it’s just that the society views these attributes as weak, given how messed up it is) and he can take in any situation pretty quickly. He’s aware of the systems of oppression that govern the Walled World (culls and bait towns), and his development seems to center on widening the scope of how he resists those systems rather than his awakening to their existence: he needs to look out not just for himself, but others or else he is complicit in their suffering. So he joins the Survey Corps, not because he sees Eren’s vision of “freedom, no matter how high the costs” but because he wants to protect his friends.

Chapter 18. I don’t think bullies worry so much about others. There’s a sense of camaraderie that seems to include Jean expressed at other points in the manga--like, yeah he’s a bit rude sometimes, but he’s our rude guy and we like him that way. No one seems to have a serious problem with him.

This seems to be how others understand Jean’s change of heart as well. Everyone is weirded out by how “responsible” he is now, rather than how much kinder--implying they didn’t really see him as cruel in the first place. No one comments, for instance, on Jean personally supporting Connie or Armin after some of their difficulties, but they do notice when he speaks up for helping others more generally, particularly at great risk to himself.

Reiner in volume 6, when Jean suggests buying time for the platoon to retreat after the Female Titan devastated their forces.

Connie, Eren, and Armin commenting on how Jean’s changed in volume 13. I’m not quite sure about Armin’s comment here; was Jean ever really a “bad guy” or just a bit of an asshole sometimes in the course of disagreeing with Eren?

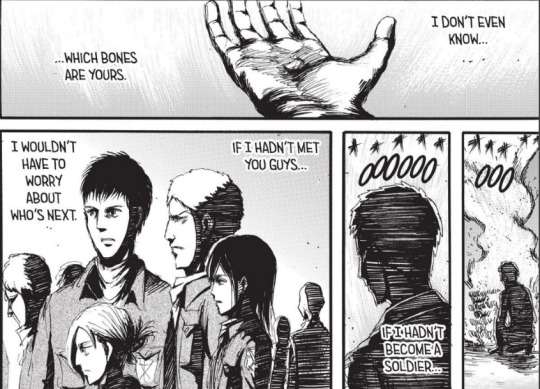

And I think Jean takes his newfound commitment to others seriously, which leads to some of his struggles during the Uprising arc as he tries to distinguish the most ethical course of action when the metric of “human versus titan” fails. He always attempts to voice his objections within the parameters allowed to him by the military, although not always in the most productive ways (think about that joke about stabbing incompetent commanders in the back . . .). In fact, he’s even willing to challenge the SC when he thinks they’re going too far in the name of the coup: part way through my initial read through of the series, I started looking to Jean for commentary on the morals of a coup that stems from within the military rather than from the will of populace.

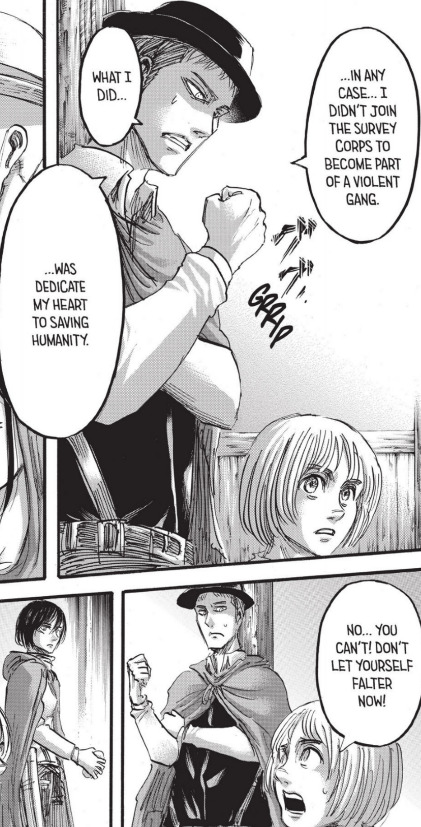

Jean voices his objections to torture, volume 14. Surely someone with a cruel streak or the impulse to bully would be able to think of some justification for torture.

Everyone is upset over Levi’s treatment of Historia, but Jean’s the only person who actually says anything, volume 14.

Jean is the first and last person to raise objections about the coup’s methods in this scene, volume 14. He feels so strongly about it he considers defying orders.

And I don’t necessarily want to get too much into the molestation scene from chapters 52 and 53, but Jean seems to object to being asked to participate in the “bait” scheme, because it makes him somewhat complicit in what happens to Armin. While presumably other members of the 104th comforted Armin after his trauma, we only see Jean doing it. In fact, he’s the only one who speaks about it apart from Mikasa, who alludes to the molestation once on the rooftop while she and Levi are setting up the trap.

Jean struggles with the tenants of the mission, which is to act as bait until they can spring a trap for the big boss of the Reeves’ company, volume 13. The implication seems to be if he were not compelled to be “Eren” at this point he could do something about what is happening to Armin.

From volume 13. Unfortunately, it also seems like Connie and Sasha are laughing here. :(

Of course, even at this stage of his maturation there’s still room for Jean to grow. For example, Jean’s response to Armin’s second “gesumin” moment, wherein he suggests fooling the masses in order to get them on the survey corps side, is to blame Armin’s unethical proposal on his recent trauma.

Volume 14.

This is not Jean’s finest moment, but I read it as him (however problematically) trying to make sense of Armin’s suggestion; a suggestion which involves manipulation and lying, two things antithetical to Jean’s own values. This ableism doesn’t belong just to Jean, but is pervasive throughout the world of Attack on Titan (many people toss around insults related to intelligence and mental health), so I read this also as a bit of a knock to their society; they could all do better. This is not to excuse Jean here, but to just acknowledge the systematic nature of the problem.

Overall, however, Jean’s the only person who’s attempting to help Armin (that we see, obviously) and I think these scenes are where we get a fuller sense of his empathy; an empathy that also leads him to try to help Eren (again, in his own blunt and awkward way) after the events of the Reiss chapel. It’s the same empathy, I think, that Marco alludes to when he says Jean understands the weak and should endeavor to help them. We can read that empathy back into his concern for his fellow soldiers, who are constantly asked to risk their lives for causes that may not even have their best interests at heart. Whereas Armin’s analytic nature leads him to discover people’s secrets and predict their movements, Jean’s empathy grants him perspective on their feelings--he can see the human in pretty much anybody, which I view as his main strength.

Over the course of the coup, Jean becomes the main voice of dissent. Although Sasha and Connie often nod along with him, he’s usually the one who either speaks first or speaks at all, and Levi realizes that he’s going to have to convince Jean eventually if he’s going to maintain order in his ranks.

From volume 14. I think it’s so interesting that we’re looking first at Jean from behind and then at him through Levi’s eyes. It’s almost like we’re meant to be identifying primarily with Jean and Levi’s looking at us--Levi has to convince us he’s right, in addition to convincing Jean. He’s also centered here, suggesting his leader status among the other recruits.