#thus the name Anthony (although that might be subject to change)

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

I wanna know who gave him a rock LMAO

Also heh………my creatures

#art#artists of tumblr#artists on tumblr#my art#welcome home#fanart#welcome home arg#welcome home fanart#wally darling#welcome home oc#my oc#the one on the right is an ant#thus the name Anthony (although that might be subject to change)#no last name for him atm#the rainbow monster on left has no name rn#but I have a nickname for him: oompa loompa#you’ll understand when I get his ref sheet done LOL

54 notes

·

View notes

Text

Saint Anthony, The Miracle Worker

June 13th - Today is the Feast Day of Saint Anthony of Padua. Ora pro nobis. (Pray for us)

He is one of the most famous saints of the Church, known universally as the super-competent manager of the celestial “Lost and Found” department. (“Tony, Tony, come around; something’s lost and can’t be found” is a prayer whispered by millions.)

For those of us accustomed to this familiar relationship, however, it may come as a shock to learn who Saint Anthony of Padua, O.F.M. actually was. For though he only lived 35 years, Anthony was renowned during his lifetime for his forceful preaching and expert knowledge of scripture – and for his miracles.

So well regarded was he, in fact, that in all of the 2000-year history of the Church, Anthony was to become the second-most-quickly canonized saint, after Peter of Verona. Anthony was canonized by Pope Gregory IX on 30 May 1232, at Spoleto, Italy, less than one year after his death.

Fernando’s Life Plans, Changed

Fernando Martins de Bulhões was born in 1195 to an aristocratic Lisbon family and initially joined the Augustinians at the age of fifteen. He was the guest master for their abbey containing the famous library at Coimbra, when his whole world suddenly changed.

Franciscan friars had settled at a small hermitage nearby; their Order had been founded only eleven years before. News soon arrived that five Franciscans had been beheaded in Morocco; the King ransomed their bodies to be returned and buried as martyrs in the Abbey.

Inspired by their example and strongly attracted to their simple, evangelical lifestyle, Fernando obtained permission to join the new Order, upon his admission adopting the name ‘Anthony.’ He then set out for Morocco; however, he fell seriously ill and on the return voyage his ship was blown off course and landed in Sicily. When he found his way to northern Italy, Anthony was finally assigned to a rural Franciscan hermitage, due to his poor health. There he lived in a cell in a nearby cave, where he spent much time in private prayer and study.

ANTHONY THE HOMILIST: One Sunday in 1222 a number of Dominican friars visited for an ordination and a misunderstanding arose as to who should preach. The Dominicans were renowned for their preaching, but had come unprepared, thinking that a Franciscan would be the homilist. Anthony was entreated him to speak whatever the Holy Spirit should inspire him with; his homily that day created a deep impression and began his career as a speaker. By 1224, St Francis of Assisi, founder of the Order, entrusted Anthony with the theological preparation for his priests.

Anthony focused on the grandeur of Christianity in his homilies and when a few years later he was sent as the envoy from the Franciscans to Pope Gregory IX, the Pope commissioned his collection, Sermons for Feast Days (Sermones in Festivitates). Gregory IX himself described him as the “Ark of the Testament.”

ANTHONY THE MIRACLE WORKER: The stories of Anthony’s 13th century miracles make fascinating reading for today’s Catholic. Despite their obvious folkloric tone, it is the miracles’ utter originality that impresses most. One comes away thinking that such astonishing occurrences can only be fairy tales — or the special kind of reality that seems to envelope the saints. As there are far too many miracles to recount here, we’ll focus on three of the most famous:

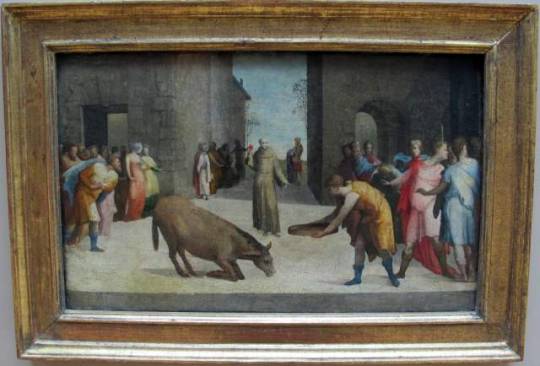

THE KNEELING MULE: The teaching of the Real Presence was disparaged in northern Italy during the 1200s, as the gnostic heresy of the Albigensians had spread from France. One day, Anthony was publically challenged. “The heretic stood up and said: ‘I’ll keep my beast of burden locked up for three days and I will starve him. After three days, in the presence of other people, I’ll let him out and I’ll show him some prepared fodder. You, on the other hand will show him what you believe to be the body of Christ. If the starving animal, ignoring the fodder, rushes to adore his God, I will sincerely believe in the faith of the Church.’

“The saint agreed straight away. God’s servant entered a nearby chapel, to perform the rites of the Mass with great devotion. Once finished, he exited where the people were waiting, carrying reverently the body of the Lord. The hungry mule was led out of the stall, and shown appetizing food. The man of God said to the animal with great faith: “In the name of virtue and the Creator, who I, although unworthy, am carrying in my hands, I ask you, o beast, and I order to come closer quickly and with humility and to show just veneration, so that the malevolent heretics will learn from this gesture that every creature is subject to the Lord, as held in the hands with priestly dignity on the altar”.

God’s servant had hardly finished speaking, when the animal, ignoring the fodder, knelt down and lowered his head to the floor, thus genuflecting before the living sacrament of the body of Christ.”

THE LISTENING FISH: The story takes place in Rimini, a port on the Adriatic near Padua. On a Sunday morning, the Saint found the fishermen there not at Mass. He began to preach to them and met only with ridicule. Anthony then stood at the edge of the water, looked in the distance, and proclaimed so that everyone would hear:

“’From the moment in which you proved yourselves to be unworthy of the Word of the Lord, look, I turn to the fish, to further confound your disbelief.’

“And filled with the Lord’s spirit, he began to preach to the fish, elaborating on their gifts given by God: how God had created them, how He was responsible for the purity of the water and how much freedom He had given them, and how they were able to eat without working.

“The fish began to gather together to listen to this speech, lifting their heads above the water and looking at him attentively, with their mouths open. As long as it pleased the Saint to talk to them, they stayed there listening attentively, as if they could reason. Nor did they leave their place, until they had received his blessing.

ANTHONY & THE BABY JESUS: Anthony was welcomed by a local resident in an Italian town where he was to preach. His host gave him a room set apart, so that he could study and contemplate undisturbed. Soon, however, his curiosity about his famous guest overcame him and his host peeped through Anthony’s window. What he saw there has been immortalized in almost every Catholic Church in the world. “A beautiful joyful baby appear in blessed Anthony’s arms. The Saint hugged and kissed him, contemplating the face with unceasing attention. The landlord was awed and enraptured by the child’s beauty, and shocked when, after a long time spent in prayer, the vision disappeared; the Saint called the landlord, and he forbade him from telling anyone what he had seen. After the Saint passed away, the man told the tale crying, swearing on the Bible that he was telling the truth.”

SOMETHING’S LOST AND CAN’T BE FOUND: An incident in the university city of Bologna is the origin of the Saint’s fame as a finder of lost items, people and spiritual goods. Anthony possessed a book of psalms with valuable notes and comments for use in teaching his students. A novice who had decided to leave the Order stole the prized psalter. Anthony prayed his psalter would be found or returned. The thief was moved to restore the book to Anthony and return to the Order. The stolen book is said to be preserved in the Franciscan friary in Bologna.

THE FAME OF ST. ANTHONY SPREAD GLOBALLY with the former Portuguese Empire and with the diaspora of 19th and 20th century Italian emigrants. Stories of the Saint’s interventions are reported, therefore, from the four corners of the earth:

In Siolim, a village in the Indian state of Goa, St. Anthony is always shown holding a serpent on a stick . This is a depiction of the incident which occurred during the construction of the church wherein a snake was disrupting construction work. The people turned to St. Anthony for help, and placed his statue at the construction site. The next morning, the snake was found caught in the cord placed in the statue’s hand.

THE GRAVE OF SAINT ANTHONY OF PADUA: Anthony was proclaimed a Doctor of the Church on 16 January 1946, and his Basilica in Padua contains his mortal remains.

By Fr. Francis Xavier Weninger, 1877

St. Anthony, who derived his surname from the city of Padua, in Italy, because he spent many years there in preaching the Gospel, was a native of Lisbon, in Portugal. He received, in holy baptism, the name of Ferdinand, and was very piously educated by his parents. No sooner had he become acquainted with the dangers of the world, than he, in the fifteenth year of his age, to be safe from temptation, went into the cloister of the regular Canons, which is not far from Lisbon, where he also made his religious vows. As, however, he was disturbed too much there by the visits of his friends, he went, with the permission of his superiors, to Coimbra, into the monastery of the Holy Cross. To this house came, one day, five friars of the Order of St. Francis, who were travelling to Africa to preach the Gospel to the Moors. They suffered martyrdom, however, soon after their arrival there, and their holy bodies were brought back to the monastery of the Holy Cross, at Coimbra, and solemnly interred in the church attached to it. Antony, hearing how fearlessly these martyrs had preached the true faith and had suffered for Christ’s sake, conceived an intense desire to preach the Gospel to the heathen and to give his life for the word of God. Hence, he determined to enter the Order of St. Francis, that he might have an opportunity to gratify the wishes of his heart.

After much hardship, he was at length, when 20 years of age, received into the Order, and after his novitiate, he obtained permission to sail for Africa and preach the Gospel to the Saracens. Scarcely had he arrived there, when God proved him by a severe sickness, which exhausted all his strength, and forced him to return to Spain. The ship, however, in which he embarked for home, encountered contrary winds, and instead of going to Spain, was driven to Sicily. No sooner had he set foot on land, than he heard that St. Francis, the holy founder of his order, had called a general chapter at Assisium. He immediately went thither, in order to receive the blessing of the Saint, which was cheerfully given. When the assemblage dispersed, not one among the superiors was found willing to be burdened with Antony, who was greatly enfeebled by his long illness, and moreover, was thought to be not quite sane. The Father Provincial of the Roman province was at last moved with compassion, and sent him to a house called Mount St. Paul, which was situated in a wilderness. There St. Antony lived a most austere life, performing the most humble labor, and occupying all his other time with prayers and holy meditations.

After passing several years in this manner, he was sent with a few other religious to Forli to be ordained priest. The guardian of the monastery requested the Dominican priests, who had also assembled there, that one of them should make an exhortation or deliver a short sermon. As they all excused themselves from so doing, he said, more in jest than in earnest, that brother Antony should speak to those assembled. Antony obeyed, and delivered so eloquent a sermon that all were astonished at his knowledge and ability, as, until now, they had deemed him one of the least gifted. Not willing that his extraordinary talent should any longer be hidden, St. Francis himself had him ordained priest, and gave him a double employment, namely, to instruct his brethren in theology and also to preach. The duties of both functions were discharged by him, with great credit to himself and an indescribable benefit to others. He converted the most hardened sinners by his sermons, and among others induced twenty-two murderers to do penance and change their wicked course of life. The heretics he convinced so thoroughly of their errors, that they could not withstand him, on account of which he was called the “Hammer of the heretics.”

Many of them he converted to the true faith, among whom was Bonovillus, who had denied the substantial presence of Christ in the Blessed Sacrament. Not able to reply to Antony’s arguments he requested the following miracles. Having starved his ass for three days, he was to bring him food at the same time that Saint Antony should come with the holy Eucharist; and if the beast, before touching his food, should fall down before the Blessed Sacrament, he would believe the Saint’s words. At the appointed time, the Saint arrived with the Blessed Sacrament, accompanied by many Catholics, and addressing the ass, which was held by Bonovillus, he said: “I command thee, in the name of thy Creator and my Saviour, whom I, although an unworthy priest, carry at this moment in my hands, that you come, in all humility, and pay Him due honors.” Bonovillus, at the same time, threw down the animal’s food and called him to come and eat. But without touching the food, the ass fell down on his fore knees, and bent his head. The Catholics rejoiced at this incontestable miracle, but the heretics hid their heads and Bonovillus was converted. At Rimini, the chief seat of the heretics, he ascended the pulpit; but as no heretic would come and listen to him, the Saint went to the sea-shore, where just at that time many of them were standing, and called to the fishes to hear his words, as men would not be instructed. And behold! suddenly a great number of fishes raised their heads out of the water, as if to listen. Speaking for a short time of their Creator, he blessed and dismissed them. This miracle caused the heretics to listen more attentively to St. Antony and to follow his admonitions.

At another time, he made the sign of the cross over a goblet filled with poison, and drank it without being harmed. The cause of his doing this was that some heretics promised to return to the true Church, if he would drink the poison and not die. A perpetual miracle was the fact that, although he preached only in one language, yet all his hearers understood him, no matter what might be their nationality.

Who can count all the miracles God wrought through this Saint, or who can sufficiently praise the wonderful gifts with which he was graced? More than once it happened that at the same time when he was standing in the pulpit to preach, he appeared also in the choir and sang the lesson of the daily office of the Church, which was pointed out to him. He prophesied many future events and knew by divine revelation many secrets of the heart. There lived, in a French city, a writer, who publicly led a most immoral life. St. Antony resided for some time in this city, and as often as he met this man, he bowed very low to him. The writer, on perceiving it, was greatly incensed, as he believed it was done by the holy man only to deride him: hence he reproached him with menacing words. The Saint, however, replied: “Be not surprised that I show such respect to you before others. I have long prayed God for the grace to die a martyr, but it has not been granted me. You, however, will receive this honor, and therefore I evince such particular respect for you.” Although the writer laughed and made a mockery of this prophecy, yet the future showed that the Saint had spoken the truth. After the expiration of some time, this immoral man made a voyage to the Holy Land, in company with the Bishop of the city. On arriving there, he was seized by the Saracens, who demanded of him that he should deny his faith. He, however, remained firm in confessing it, and after having been greatly tormented, he suffered the death of a martyr.

St. Antony was as undaunted and fearless in punishing the wicked, when circumstances required it, as he was famous by the gift of prophecy. At that period Florence was governed by Ezelinus, who, among other cruel deeds, had executed 11,000 men of Padua, part of whom were in his service and part in garrison at Verona, because the inhabitants of Padua had rebelled. Nobody dared to oppose this tyrant in the execution of further barbarities but St. Antony, who had sufficient courage to go to him, and representing most powerfully his inhuman conduct, threatened him with the just wrath of the Almighty and the torments of hell, in case he repented not and abstained from, his tyranny.

During this menace flames of fire darted from the countenance of St. Antony, as Ezelinus afterwards related, which so thoroughly frightened the tyrant, that he fell trembling at the feet of the Saint, and most earnestly promised repentance. As he converted this and many other sinners by admonition, he moved others , in a different way to do penance. Many said that he had suddenly appeared before them at night and exhorted them to repent. “Rise quickly, said he at such times, and confess the sin by which you have offended the majesty of God.”

I should hardly know where to end, were I to relate all that St. Antony did to convert sinners, or how many future events he foretold. I will mention only a few more facts, from which the conclusion may be drawn that, as the holy man appeared in different places at the same time, so also, by the power of God, he was miraculously transported, in one moment, from one place to another. The father of St. Antony resided at Lisbon in Portugal, as treasurer of the royal revenues, the duties of which office he discharged with fidelity and integrity. One day, he was requested by some gentlemen in the king’s service to advance them some money out of the king’s treasury, making a verbal promise to return the same in a short time. The pious treasurer, who neither feared deception nor danger, gave them what they asked, without taking a written receipt. When the time arrived at which he had to deliver his account, he asked the officers for the borrowed money, but they denied having received any. This perfidy grieved the kind man deeply, and he knew not what to do. Seeking refuge in fervent prayers to God, he received help in a miraculous way through his son, who resided at that time in Italy. At the time he was to appear before the royal judge to be sentenced to return the missing money, his holy son suddenly appeared in the room, and addressed the officers in the following manner: “This kind man, my father, has advanced you, upon your request, a sum of money out of the royal treasury, on such a day, at such an hour, in such a place, as is well known to you. I warn you to return it to him and to indemnify him; otherwise, divine vengeance will strike you, and you will be heavily punished.” The guilty men were not less astonished at the presence of the holy man, than at his menaces and the revelation of their wickedness. They immediately testified in writing how much each of them had received, promising at the same time to repay it in a short time. No sooner was this done, than the Saint disappeared from their view.

This pious treasurer was in still greater danger at another time. He was accused of having committed murder, and sentence was to be executed on him and his servant on the following day. Antony was at Padua; but God revealed to him what had taken place at Lisbon. The Saint asked permission of his superior to seek some recreation out of the city. Hardly was he out of the place, when, like Habakuk, he was carried by an angel through the air to Lisbon. He went to the judge and represented his father’s innocence. Finding, however, no willing ear in the judge, he repaired to the grave of the murdered man, commanded him to rise, and leading him to the judge, he requested of him to say if his father was the man, who, with the aid of his servant had assassinated him. The risen man replied distinctly: “No: it was not he.” The Judge requested that St. Antony should demand of him the name of the real murderer: the Saint, however, replied: ” I have not come to bring death to a guilty man, but to rescue the innocent.” Upon this, his father and his servant were released, and Antony was carried back to Padua by the angel.

After this wonder-working servant of God had filled all Italy and France with the fame of his miracles and conversions, God revealed to him his approaching last hour. He repaired to an isolated spot, and having prepared himself for his end, he returned very sick to Padua, received extreme unction, recited the seven Penitential Psalms, and his usual prayer: “O Glorious Lady, &c.” The divine mother appeared to him with the child Jesus, and the Saint conversed with them most lovingly until his pure soul went to the abode of the blessed. This took place in 1231, when he was hardly 36 years of age. They desired to keep his death concealed from the people for some time, but the little children proclaimed it by calling out in the streets: “The Saint is dead.” Thirty-two years later, when his holy remains were raised, his tongue was found entirely incorrupt. St. Bonaventure taking it in his-hand, said: “O blessed tongue, which always praised God and taught others how to praise Him! Now we have evidence how great thy merits were before God!”

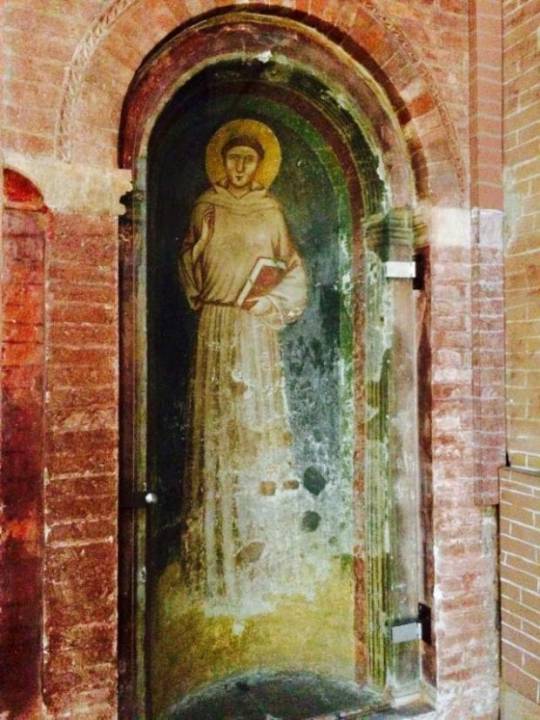

The Saint is generally represented with the divine Child, as He appeared to him and embraced him. The lilies are also dedicated to him as an emblem of his unspotted innocence and purity. It is well known that this Saint is invoked when things are lost or have been purloined. Countless occurrences show at this day that the intercession of this Saint is powerful at the throne of the Almighty.

By: Beverly Stevens

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Towards Relational Design by Andrew Blauvelt

Is there an overarching philosophy that can connect projects from such diverse fields as architecture, graphic and product design? Or are we beyond such pronouncements? Should we even expect such grand narratives anymore?

I’ve spent more time in the field of graphic design, and within that one discipline it is extremely difficult to pinpoint coherent sets of ideas or beliefs guiding recent work — certainly nothing as definitive as in previous decades, whether the mannerisms of so-called grunge typography, the gloss of a term such as postmodernism, or even the reactionary label of neo-modernism. After looking at a variety of projects across the design fields and lecturing on the topic, new patterns do emerge. Some of the most interesting work today is not reducible to the same polemic of form and counter-form, action and reaction, which has become the predictable basis for most on-going debates for decades. Instead, we are in the midst of a much larger paradigm shift across all design disciplines, one that is uneven in its development, but is potentially more transformative than previous isms, or micro-historic trends, would indicate. More specifically, I believe we are in the third major phase of modern design history: an era of relationally-based, contextually-specific design. The first phase of modern design, born in the early twentieth century, was a search for a language of form that was plastic or mutable, a visual syntax that could be learned and thus disseminated rationally and potentially universally. This phase witnessed a succession of “isms” — Suprematism, Futurism, Constructivism, de Stijl, ad infinitum — that inevitably fused the notion of an avant-garde as synonymous with formal innovation itself. Indeed, it is this inheritance of modernism that allows us to speak of a “visual language” of design at all. The values of simplification, reduction, and essentialism determine the direction of most abstract, formal design languages. One can trace this evolution from the early Russian Constructivists’ belief in a universal language of form that could transcend class and social differences (literate versus oral culture) to the abstracted logotypes of the 1960s and 1970s that could help bridge the cultural divides of transnational corporations: from El Lissitzsky’s “Beat the Whites with the Red Wedge” poster to the perfect union of syntactic and semantic form in Target’s bullseye logo.

The second wave of design, born in the 1960s, focused on design’s meaning-making potential, its symbolic value, its semantic dimension and narrative potential, and thus was preoccupied with its essential content. This wave continued in different ways for several decades, reaching its apogee in graphic design in the 1980s and early 1990s, with the ultimate claim of “authorship” by designers (i.e., controlling content and thus form), and in theories about product semantics, which sought to embody in their forms the functional and cultural symbolism of objects and their forms. Architects such as Robert Venturi, Denise Scott Brown, and Steven Izenour’s famous content analysis of the vernacular commercial strip of Las Vegas or the meaning-making exercises of the design work coming out of Cranbrook Academy of Art in the 1980s are emblematic. Importantly, in this phase of design, the making of meaning was still located with the designer, although much discussion took place about a reader’s multiple interpretations. In the end though, meaning was still a “gift” presented by designers-as-authors to their audiences. If in the first phase form begets form, then in this second phase, injecting content into the equation produced new forms. Or, as philosopher Henri Lefebvre once said, “Surely there comes a moment when formalism is exhausted, when only a new injection of content into form can destroy it and so open up the way to innovation.” To paraphrase Lefebvre, only a new injection of context into the form-content equation can destroy it, thus opening new paths to innovation.

The third wave of design began in the mid-1990s and explores design’s performative dimension: its effects on users, its pragmatic and programmatic constraints, its rhetorical impact, and its ability to facilitate social interactions. Like many things that emerged in the 1990s, it was tightly linked to digital technologies, even inspired by its metaphors (e.g., social networking, open source collaboration, interactivity), but not limited only to the world of zeroes and ones. This phase both follows and departs from twentieth-century experiments in form and content, which have traditionally defined the spheres of avant-garde practice. However, the new practices of relational design include performative, pragmatic, programmatic, process-oriented, open-ended, experiential and participatory elements. This new phase is preoccupied with design’s effects — extending beyond the design object and even its connotations and cultural symbolism.

We might chart the movement of these three phases of design, in linguistic terms, as moving from form to content to context; or, in the parlance of semiotics, from syntax to semantics to pragmatics. This outward expansion of ideas moves, like ripples on a pond, from the formal logic of the designed object, to the symbolic or cultural logic of the meanings such forms evoke, and finally to the programmatic logic of both design’s production and the sites of its consumption — the messy reality of its ultimate context.

Design, because of its functional intentions, has always had a relational dimension. In other words, all forms of design produce effects, some small, some large. But what is different about this phase of design is the primary role that has been given to areas that once seemed beyond the purview of design’s form and content equation. For example, the imagined and often idealized audience becomes an actual user(s) — the so-called “market of one” promised by mass customization and print-on-demand; or perhaps the “end-user” becomes the designer themselves, through do-it-yourself projects, the creative hacking of existing designs, or by “crowdsourcing,” producing with like-minded peers to solve problems previously too complex or expensive to solve in conventional ways. This is the promise that Time magazine made when it named you (a nosism, like the royal we) person of the year in 2006, even as it evoked the emerging dominance of sites such as MySpace, Facebook, Wikipedia, Ebay, Amazon, Flickr and YouTube, or anticipated the business model of Threadless. The participation of the user in the creation of the design can be seen in the numerous do-it-yourself projects in magazines such as Craft, Make and Readymade, but they can also be seen in the generic formats for advertisements and greeting cards by Daniel Eatock.

Even in most instrumental forms of design, the audience has changed from the clichéd focus group sequestered in a room answering questions for people hiding behind two-way mirrors to the subjects of dogged ethnographic research, observed in their natural surroundings — moving away from the idealized concept of use toward the complex reality of behavior. Today, the audience is thought of as a social being, one who is exhaustively data-mined and geo-demographically profiled — taking us from the idea of an average or composite consumer to an individual purchaser among others living a similar social lifestyle community. But unlike previous experiments in 1970s-style community-based design or behavioral modification, today’s relationship to the user is more nuanced and complicated. The range of practices varies greatly, from the product development methods employed by practices such as IDEO, creators of the famed Nightline shopping cart, to the “social probes[,]” of Anthony Dunne and Fiona Raby who create designed objects, not to fulfill prescribed functions but instead use them to gauge behavioral reactions to the perceived effects of electromagnetic energy or the ethical dilemmas of gene testing and restorative therapies.

Once shunned or reluctantly tolerated, constraints — financial, aesthetic, social, or otherwise — are frequently embraced not as limits to personal expression or professional freedom, but rather as opportunities to guide the development of designs; arbitrary variables in the equation that can alter the course of a design’s development. Seen as a good thing, such restrictions inject outside influence into an otherwise idealized process and, for some, a certain element of unpredictability and even randomness alters the course of events. Embracing constraints — whether strictly applying existing zoning codes as a way to literally shape a building or an ethos of material efficiency embodied in print-on-demand — as creative forces, not obstacles on the path of design, further opens the design process demanding ever-more nimble, agile and responsive systems. This is not to suggest that design is not always already constrained by numerous factors beyond its control, but rather that such encumbrances can be viewed productively as affordances. In architecture, the discourse has shifted from the purity and organizational control of space to the inhabitation of real places — the messy realities of actual lives, living patterns over time, programmatic contradictions, zoning restrictions, and social, not simply physical, sites. For instance, architect Teddy Cruz in his Manufactured Sites project, offers a simple, prefabricated steel framework for use in the shantytowns on the outskirts of Tijuana — a structure that participates in the vernacular building practices that imports and recycles the detritus of Southern California’s dismantled suburbia. This provisional gesture integrates itself into the existing conditions of an architecture born out of crisis. The objective is not the utopian tabla rasa of architectural modernism — a replacement of the favela — but rather the interjection of a micro-utopian element into the mix.

Not surprisingly, the very nature of design and the traditional roles of the designer and consumer have shifted dramatically. In the 1980s, the desktop publishing revolution threatened to make every computer user a designer, but in reality it served to expand the role of the designer as author and publisher. The real “threat” arrived with the advent of Web 2.0 and the social networking and mass collaborative sites that it has engendered. Just as the role of the user has expanded and even encompasses the role of the traditional designer at times (in the guise of futurist Alvin Toffler’s prophetic “prosumer”), the nature of design itself has broadened from giving form to discrete objects to the creation of systems and more open-ended frameworks for engagement: designs for making designs. Yesterday’s designer was closely linked with the command-control vision of the engineer, but today’s designer is closer to the if-then approach of the programmer. It is this programmatic or social logic that holds sway in relational design, eclipsing the cultural and symbolic logic of content-based design and the aesthetic and formal logic of modernism’s initial phase. Relational design is obsessed with processes and systems to generate designs, which do not follow the same linear, cybernetic logic of yesteryear. For instance, the typographic logic of the Univers family of fonts, established a predictive system and closed set of varying typeface weights. By contrast, a Web-based application for Twin, a typeface by Letterror, can alter its appearance incrementally based on such seemingly arbitrary factors as air temperature or wind speed. In a recent design for a new graphic design museum in the Netherlands, Lust created a digital, automated “posterwall,” feed by information streams from various Internet sources and governed by algorithms designed to produce 600 posters a day.

Perhaps the best illustration of this movement toward relational design can be gleaned through the prosaic vacuum cleaner. In the realm of the syntactical and formal, we have the Dirt Devil Kone, designed by Karim Rashid, a sleek conical object that looks so good it “can be left on display.” While the vacuum designs of James Dyson are rooted in a classic functionalist approach, the designs themselves embody the meaning of function, using color-coded segmentation of parts and even the expressive symbolism of a pivoting ball to connote a high-tech approach to domestic cleaning. On the other hand, the Roomba, a robotic vacuum cleaner, uses various sensors and programming to establish its physical relationship to the room it cleans, forsaking any continuous contact with its human users, with only the occasional encounter with a house pet. In a display of advanced product development, however, the company that makes the Roomba now offers a basic kit that can be modified by robot enthusiasts in numerous, unscripted ways, placing design and innovation in the hands of its customers.

If the first phase of design offered us infinite forms and the second phase variable interpretations — the injection of content to create new forms — then the third phase presents a multitude of contingent or conditional solutions: open-ended rather than closed systems; real world constraints and contexts over idealized utopias; relational connections instead of reflexive imbrication; in lieu of the forelorn designer, the possibility of many designers; the loss of designs that are highly controlled and prescribed and the ascendency of enabling or generative systems; the end of discrete objects, hermetic meanings, and the beginning of connected ecologies.

After 100 years of experiments in form and content, design now explores the realm of context in all its manifestations — social, cultural, political, geographic, technological, philosophical, informatic, etc. Because the results of such work do not coalesce into a unified formal argument and because they defy conventional working models and processes, it may not be apparent that the diversity of forms and practices unleashed may determine the trajectory of design for the next century.

Andrew Blauvelt, Towards Relational Design (2008) Design Observer, 07.09.20

0 notes

Text

Nietzsche’s “Untimely Meditations”

❍❍❍

A very difficult book to read in English. The best translation I have found is the one by Ludovici and Collins. The worst is by R.J. Hollingdale published by Cambridge University Press. The good translation by Ludovici and Collins, however, is published by Digireads.com and has the worst introduction by anti-semitic and white-nationalist Oscar Levy written in 1909. His review was probably the most racist and white-nationalist academic writing I have ever read. The introduction of the Cambridge University Press by Daniel Breazeale is very deep and enlightening.

The Digireads book has the essays non-chronologically. It has the first and last meditation as Part 1 and has the second and third meditation as Part 2. It works better because I could just ignore the part 1, which contains the 2 most boring works of Nietzsche: "David Strauss, the Confessor and the Writer” and “Richard Wagner in Bayreuth”. You need to have a full scholarship to read both of those essays and not fall sleep. Although Nietzsche admits that the real subject of the essays “Richard Wagner in Bayreuth” and “Schopenhauer as Educator” is himself, we don’t see the usual fire that is inside his writings in part 1 of meditations. I think, its mostly, due to Nietzsche’s narrow focus on the German condition rather than a border analyzation that we see in part 2 of the meditations. That might be the reason he abandons the projects after finishing the “Richard Wagner in Bayreuth”.

The young Nietzsche was into Schopenhauer, Goethe, and Machiavelli. The mature Nietzsche was into Stendhal, Dostoyevsky and (again) Machiavelli. He might have been inspired by La Rochefoucauld for his aphorisms in the latter part of his life but I don’t think the influence was as high as other figures.

It is also understandable that writing of thesis meditations is simultaneous with Nietzsche’s shift of interest from philology to philosophy. Nietzsche seems to be focusing on concepts of “culture” and evolution of “culture through education”, especially in “Schopenhauer as Educator”. I am not sure if by culture he means national culture? I wouldn’t expect him to know any better, especially that 140 years ago culture was widely understood to belong to nations. The state was the precursor to culture. In that view, without state, there would be no culture –a colonial idea that dominated the 19th century Europe and dehumanized southern peoples with a darker complexion. Montserrat Guibernau has a great essay on this topic in analyzing Anthony D. Smith’s national identity and culture. She focused on the idea that the European conception of nation and culture often mixed with the notion of state. In this view, the existence of nations without state becomes undermined.

The right-wing interpreters of Nietzsche admire this book because it contains most of Nietzsche’s philosophy minus the most important part; “harsh and direct attack on Christianity”. Currently –but for not much longer– I live in Finland. The brute skin-head racism here functions similar to the rest of the white-majority countries. The idea that a traditionally white nation cannot become mixed with darker peoples. Recently, Jussi Halla-aho the leader of the second-largest political party in Finland (True Finns) announced that the only “real Finnish people” are white and Christian. Simultaneous with this type of violence, some white academics who see themselves in opposition with the far-right mentality, think racism is an import of globalization and a side effect of the current economic system. They omit the notion of racial/cultural homogeneity and monochrome Christian practices and its history.

On Nietzsche’s criticism of Christianity, Reza Aslan comes to mind, an academic who wrote the book “Zealot: The Life and Times of Jesus of Nazareth” on the life of Jesus. Since 2013, he received much criticism simultaneous with death-threats solely because he is Muslim. In some part of the book, he argued how the catholic church has preferred to promote Jesus as a peaceful spiritual teacher rather than a politically motivated revolutionary who urged his followers to keep his identity a secret.

Going back to Nietzsche, his meditation “On the Uses and Disadvantages of History for Life” was the essay that inspired Foucault in his work on madness. “Schopenhauer as Educator” has probably inspired other postmodern thinkers who were interested not just in culture but in different modes of thinking and knowledge production. Edward Said ends his introduction of Orientalism (1978) with a quote from Raymond Williams and invites us to engage in a process which will result in “unlearning” of “the inherent dominative mode” [of thinking]. We see the roots of this idea not just in “Schopenhauer as Educator” but in Nietzsche’s life itself. How do you break with your teacher and friend, who have uplifted you to where you are? And more important than that how do you engage in a field that is completely antagonistic to what you have been taught? We can see the evolution of Nietzsche’s oeuvre from “Richard Wagner in Bayreuth” to “Nietzsche contra Wagner” which he wrote in the last years of his career. And we can see a change in Nietzsche’s mode of living from Wagner years to his solitude and madness. Similar to his Zarathustra who first ascents to the mountains to solitude, then descend back to humanity. One might interpret this process as an Eternal Return (eternal recurrence) -a non-Deleuzian interpretation of the concept which is contrary to Deleuze's Eternal Return as the moment in which extremity of differences is reached.

As far as historical heretics and political activists names such as Mansur Al-Hallaj and Shahab al-Din Suhrawardi come to my mind. Mansour Al-Hallaj was a Persian mystic, poet and teacher of Sufism in his book, “Kitaab al-Tawaaseen��� (902) he mentions:

If you do not recognize God, at least recognize His sign, I am the creative truth because through the truth, I am eternal truth. — Ana al-Haqq (I’m the truth/God)

This is the place where we have to be reminded of “writing with one’s own blood”, writing as an activist, making art as an activist. A more contemporary figure that comes to mind in reading Nietzsche's Meditations is Malcolm X. He has definitely read Nietzsche or at least “On the Uses and Disadvantages of History for Life”. Malcolm understood the notion of healing the wounds which he also referred to in some of the interviews. Thinking about Nietzsche’s emphasis on the philosopher’s way of life, and what Nietzsche himself has done to Wagner, we can see a correlation to Malcolm X’s life. What Malcolm X has done to Elijah Muhammad is not much different than what Nietzsche has done to Wagner (although we can agree that anti-semitic Wagner was a much lower and nastier character than Elijah Muhammad). How do you break apart from your teacher, admit our mistake, mature yourself and your ideas? In almost every photo or interview, Malcolm X is smiling and laughing. How to maintain a cheerful attitude toward life in the midst of dark and gloomy events?

Malcolm X was always direct and on point. One of the examples of ideal greatness which Nietzsche used in Thus Spoke Zarathustra was borrowed from ancient Persians: “To speak the truth, and be skillful with bow and arrow”. Shooting well with arrows has a connotation to be on point and straight forward. (1)

“In order to determine this degree of history and, through that, the borderline at which the past must be forgotten if it is not to become the gravedigger of the present, we have to know precisely how great the plastic force of a person, a people, or a culture is. I mean that force of growing in a different way out of oneself, of reshaping and incorporating the past and the foreign, of healing wounds, compensating for what has been lost, rebuilding shattered forms out of one's self. There are people who possess so little of this force that they bleed to death incurably from a single experience, a single pain, often even from a single tender injustice, as from a really small bloody scratch. On the other hand, there are people whom the wildest and most horrific accidents in life and even actions of their own wickedness injure so little that right in the middle of these experiences or shortly after they bring the issue to a reasonable state of well being with a sort of quiet conscience.” (On the Use and Abuse of History for Life, translated by Ian C. Johnston)

Malcolm X’s life can be an embodiment of Nietzschean philosophy, a better example than the life Nietzsche lived himself. One can argue that Malcolm X might have been slightly inspired by Nietzsche, or maximally Malcolm X completed Nietzsche’s philosophy by actualizing it in his own life. Nietzsche’s philosophy is not made to be actualized or utilized in a state level, cultural level, or worst national-cultural. It starts with the individual and stops at the individual level. His critique of modernity and modern humans is one and the same.

“Every philosophy which believes that the problem of existence is touched on, not to say solved, by a political event is a joke- and pseudo-philosophy. Many states have been founded since the world began; that is an old story. How should a political innovation suffice to turn men once and for all into contented inhabitants of the earth? But if anyone really does believe in this possibility he ought to come forward, for he truly deserves to become a professor of philosophy at a German university…” -Schopenhauer as Educator, translation by R. J. Hollingdale, 1984 Cambridge University Press

“Culture and the state—let no one deceive himself here—are antagonists: ‘cultural state’ is just a modern idea. The one lives off the other, the one flourishes at the expense of the other. All great periods in culture are periods of political decline: anything which is great in a cultural sense was unpolitical, even antipolitical.”–Twilight of the Idols, translated by Large, Duncan. (2)

In a talk about Nietzsche and Derrida, Spivak mentioned that the life of an activist requires more than writing. Gramsci, Malcolm X, and such people didn’t just write books, they had notebooks or a series of essays and speeches. Gramsci and Malcolm X were operating outside of the academy, next to their communities and comrades where their struggle was taking shape. They were writing with blood.

At the first look, there might not be any similarity between Malcolm X and Nietzsche. The former was a political activist and the latter was a philosopher-artist. The former was a Muslim minister and the latter was a Christian heretic and son of a Lutheran minister. Malcolm was nationally famous at the time of his assassination. Nietzsche was almost unknown outside of his close circle at the time of his death. Yet, there might be some parallel characteristics between the two. In the past, there has been some informal comparison between these two figures and their works. For instance, Malcolm X’s House Negro Speech and Nietzsche’s On the Genealogy of Morality.

Both Nietzsche and Malcolm X were tired of their contemporary condition, the political climate of their region, and the failed struggles of the past generations that were passed on to them. Nietzsche took refuge in Greek tragedy, classical antiquity and Pre-Socratic philosophy. Malcolm took refuge in Islam, international black struggles, Pan-Africanism and Organization of Afro-American Unity. They both experienced a dramatic shift in their ideology and position, although with different intensities. Nietzsche shifted away from Wagner and German Wagnerism, and Malcolm X shifted from Elijah Muhammad and Nation of Islam toward a more comprehensive radical positionality, especially in regard to white Americans.

When Malcolm was in prison he read Nietzsche, Schopenhauer, and Kant. In his autobiography, he described his education: “Many who today hear me somewhere in person, or on television, or those who read something I’ve said, will think I went to school far beyond the eighth grade. This impression is due entirely to my prison studies.” (3)

One contrast between Malcolm and Nietzsche’s life is that Nietzsche’s isolation and his idea’s of solitude have very radical individual aspect built into it, while Malcolm’s struggle as much as it was personal, to a great degree it was a predicate from the general social isolation of African-Americans in pre-Civil Rights Act of 1964 America. Both Malcolm and Nietzsche disliked alcohol drinking and smoking.

"The heaviest weight. -What if some day or night a demon were to steal into your loneliest loneliness and say to you : 'This life as you now live it and have lived it you will have to live once again and innumerable times again; and there will be nothing new in it, but every pain and every joy and every thought and sigh and everything unspeakably small or great in your life must return to you, all in the same succession and sequence - even this spider and this moonlight between the trees, and even this moment and I myself. The eternal hourglass of existence is turned over again and again, and you with it, speck of dust!' Would you not throw yourself down and gnash your teeth and curse the demon who spoke thus? Or have you once experienced a tremendous moment when you would have answered him: 'You are a god, and never have I heard anything more divine.' If this thought gained power over you, as you are it would transform and possibly crush you; the question in each and every thing, 'Do you want this again and innumerable times again?' would lie on your actions as the heaviest weight!" Nietzsche, Friedrich. The Gay Science. Cambridge University Press, 2001, p. 194.

Photo: Mirza Cizmic, “Reality is finally better than my dreams”, from “Broken Fragments, 2019”

I like to connect Nietzsche with the new “Iranian nationalism” and opposition to the Islamic Republic which sometimes results in Islamophobia and another version of Uncle Tomism of the Middle East. Nietzsche is a very dangerous thinker, he can mess you up or uplift you to a higher human. As he says, “I am not a man, I am a Dynamite!”. What you get out of Nietzsche can depend on many things, how you read him, and when you read him, where you are in society and where you have come from. Nietzsche is not only against God, but he is against the god-like sovereign world-view. The universalism of European objectivity and concepts such as theology, history and even science are deeply problematic for him.

Reading Nietzsche after leaving Iran to Germany transformed Aramesh Dustdar an Iranian Heideggerian philosopher into an Islamophobe. In 2010, after the Green movement in Iran, he wrote a letter to Jürgen Habermas, condemning Islam and calling the recent events in Iran as “Shia-Iranian...magic show” staged by a bunch of crafty “pretenders to philosophy.” (4) This letter sparked a lot of debate among Iranian intellectual community condemning Dustdar for his Eurocentric views upholding the orientalist banner: non-Europeans are incapable of thinking.

According to Badiou (wink wink), Modernism started in music before fine arts and Richard Wagner was one of the people who started it. Even if we want to speak in such a categorical language, Wagner’s violent modernism was challenged by Nietzsche who took up the task of overcoming the centricity of the absolute mediums. He identified as an artist more than a philosopher and often used poetry in his works. He believed that old-school rigid theoreticians inside European academies and philosophy as a whole are following the footpath of Hegel's absolute knowledge and scientific objectivity. Something that he saw very dangerous and sought to overcome.

“What people in earlier times gave the church, people now give, although in scantier amounts, to science.”

Anti-semitic Wager used the term Gesamtkunstwerk (total work of art) for his operas where all sorts of visual and auditory mediums were combined: music, dance, theatre, and images. There is an array of white supremacists supporting Wagner’s case (from Hitler to today’s Roger Scruton) on defending Wagner and bringing back the very white/pure European modernity which Scruton calls “high culture", he writes: “Modern high culture is as much a set of footnotes to Wagner as Western philosophy is, in Whitehead’s judgement, footnotes to Plato”. (5)

“…let us leave the superhistorical people to their revulsion and their wisdom. Today for once we would much rather become joyful in our hearts with our lack of wisdom and make the day happy for ourselves as active and progressive people, as men who revere the process. Let our evaluation of the historical be only a western bias, if only from within this bias we at least move forward and not do remain still, if only we always just learn better to carry on history for the purposes of living! For we will happily concede that the superhistorical people possess more wisdom than we do, so long, that is, as we may be confident that we possess more life than they do. For thus at any rate our lack of wisdom will have more of a future than their wisdom.”

“Insofar as history stands in the service of life, it stands in the service of an unhistorical power and will therefore, in this subordinate position, never be able to (and should never be able to) become pure science, something like mathematics. However, the problem to what degree living requires the services of history generally is one of the most important questions and concerns with respect to the health of a human being, a people, or a culture. For with a certain excess of history, living crumbles away and degenerates. Moreover, history itself also degenerates through this decay.” (6)

Bib.

1. Nietzsche, Friedrich and Common, Thomas. Thus Spoke Zarathustra. s.l. : Dover Publications, 1999. 0486406636. 2. FRIEDRICH NIETZSCHE, Duncan Large. Twilight of the Idols or How to Philosophize with a Hammer. s.l. : OXFORD WORLD’S CLASSICS, 1998. 3. 15 Books Malcolm X Read In Prison. radicalreads.com. [Online] APRIL 10, 2018. https://radicalreads.com/malcolm-x-favorite-books/. 4. HAMID DABASHI, AHMAD SADRI, MAHMOUD SADRI. An Open Letter to Jürgen Habermas. PBS. [Online] October 17, 2010. https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/pages/frontline/tehranbureau/2010/10/an-open-letter-to-jurgen-habermas.html. 5. Jakobsen, Peter. Wagner and Modernism. www.thevarnishedculture.com. [Online] May 26, 2016. http://www.thevarnishedculture.com/wagner-and-modernism/. 6. Nietzsche, Friedrich. The Untimely Meditations (Thoughts Out of Season 1-2). s.l. : Digireads.com, 2010. ISBN13: 9781420934557.

(Cover photo by Negin)

youtube

Suva, “Interminably outside the box” 2019

0 notes

Text

coffeewyrm:

I personally feel that Bob might be less than eager to come out and flatly name Jarlaxle as Pan sexual simply because, as he’s said at booksignings, etc (trust me, I’ve asked), that although he write these characters, they’re not entirely licenced to him.

I personally would love to see stuff written about Zaknafein and Jarlaxle from the old days, but he’s said that will likely never happen because it’s not necessarily popular.

I feel the same may possibly be said for Jarlaxles sexuality. He writes as “questionably” as possible without outright saying it.

Not saying it’s right or fair, but saying it’s likely that’s where he stands.

[[ You bring up a fair point. Just for my own clarity, did you mean that you’ve asked Bob at booksignings specifically if Jarlaxle is pan? I wasn’t sure if you meant that you’d asked about that subject explicitly, or about something more general pertaining to the extent of Bob’s ownership of the characters and the franchise. XD

I do agree that what Bob can and cannot disclose are affected by his lack of total ownership of the characters in the Drizzt books. However, I feel that there’s a not insignificant difference between shared licensing preventing him from not making a character a certain way versus him not writing certain books. The former has to do with creative decision-making, whereas the latter, although we’d like to also be mostly about creative decision-making, boils down to financial factors.

As mentioned in my original post (reblog chain truncated here because I didn’t want to spam people’s dashes XD), it is indeed the case that Bob doesn’t fully “own” the characters in the Drizzt books, technically WotC does (and TSR before them, but WotC bought TSR). The balance of power definitely favors WotC in that relationship, for Bob can’t publish Drizzt books on his own without WotC’s sanctioning, and WotC could theoretically, and has in the past, contract with a different author to write Drizzt. However, WotC’s experiment with having another author write Drizzt didn’t amount to much beyond a short story, as the conflicts between them and Bob were resolved (the story was "Fires of Narbondel" by Mark Anthony, from Realms of the Underdark. That short story is basically non-canon at this point). Furthermore, in the past, WotC/TSR has wanted to do things like kill off Entreri during the global purge of assassins in the events detailed in the Avatar Series. Needless to say, that didn’t happen, and the details were recently re-explained by James D. Lowder in the Forgotten Realms Archives group on Facebook,

“The ‘assassins’ died in Avatar because the class vanished in the initial 2nd edition D&D rules and Avatar was supposed to reflect the changes in the world wrought by changes in the game rules from 1st to 2nd edition. I recall the elimination of assassins being a move, like the renaming of devils and demons, intended to take away some of the most obvious targets for reactionary criticism of D&D by the moral panic crowd, but I was not in on those design or PR discussions. As Avatar editor, I recall getting news of that decision after the novels were already underway, so the assassins' mass death ended up being shoehorned into the story, without much grace and without a lot of time to consider repercussions across the other Realms fiction series. (This is a good example of a game rules change that cannot be reflected well in fiction, not without a lot of lead time and some serious work put into the continuity decisions.) In the end, it was decided that who the assassin worshiped and how they defined themselves mattered, which allowed Artemis to survive. (...) It was a discussion more than Bob just refusing. Bob said he didn't want to kill off the character and I got together with his editor and the head of the department to figure out options. We knew the apparent ban on assassins was not workable in the Realms fiction, but we needed to convince higher-ups to let us find some wiggle room.”

Another thing is before the Double Diamond Triangle Saga was declared to be non-canon, what would’ve been a permanent injury sustained by Entreri as written by the group of authors that did not include Bob had to be done away with because Bob didn’t want to work with what WotC had contracted them to write. I suppose that at the end of the day though, WotC does get the final say, but it’s not as absolute as a boss and minion type of relationship. Bob actually has a lot more power than he lets on, because even though his characters are technically “owned” by WotC, they are still Bob’s characters, and WotC does want things related to the Drizzt franchise to align with what Bob wants. I think that Lowder’s explanation sheds a lot of insight into the balance of power between WotC and author relationships, especially that while the publisher (WotC) could say no, they’re more likely to indulge their authors rather than not, so long as they’ve actually got a contract that’s already been agreed upon.

That being said, the situation with additional books, such as a spin-off about Jarlaxle and Zaknafein, is different from ascribing certain characteristics to existent characters or even the addition of new characters, so long as the contract already exists. I suspect that, even though we're just now hearing about the lack of any new novels planned for the future, that Bob already knew about it long before. Even if he hadn't, the trend since 3.5e has been significantly reduced number of novels, so he would've seen something like that coming. And, even if he didn't foresee that, he can’t publish Drizzt and/or Forgotten Realms books on his own, because they’re owned by WotC. The creation of these sorts of books would generate revenue, which is legally relevant and not something he can just do. I suppose he could theoretically write on without WotC’s endorsement, but he could not be paid for it, nor would anything he writes like that be considered “canon”. Some authors, like Elaine Cunningham, write supplements for their published Realms works that they offer for free, but these documents’ official status is “fanfiction”. Many fans don’t care and embrace as canon anything written by the original creators anyway, but the potential issue is that WotC could always contract someone else to write and publish stuff that overwrites what the original author creates, so most just don’t bother. Still, as you can imagine, it’s mutually beneficial for the original authors to keep creating in their sub-franchises, so long as WotC approves any additional creation at all, which is not happening with the novels. But, ultimately, all of that stuff is just about the money, and when money’s involved, things get tricky.

The sense that I've gotten from Forgotten Realms novels as a whole is that WotC is not a heavy-handed overlord when it comes to micromanaging the creative expression of their contracted authors. It is the case that WotC dictates what happens in their world, because fundamentally, the novel lines are supplementary material to the game and thus events in the books must reflect events in D&D. This leads to prevailing themes/events like the Time of Troubles, the Spellplague, the Sundering, etc. However, WotC doesn’t dictate details like the sexuality of characters. It isn’t that homosexuality hasn’t been a theme for a long time in Salvatore’s books, but rather, it’s homosexuality restricted to one gender/sex for two decades before we saw a change. The father of the Forgotten Realms, Ed Greenwood, has always stated that the Realms is a place that, unlike our world, is free from sexuality-targeted prejudices. Many authors have expanded upon this theme, and while Salvatore hasn’t actively violated it, the fact that the only beings capable of homosexual behavior in his books for so freaking long have been exclusively female is a choice on his part, one that not all of his fellow Forgotten Realms authors made. The only alternative is that TSR/WotC told him to put in gratuitous lesbian pairings/sex to make his books more attractive while not doing the same to its other authors, which doesn’t make much sense, but I suppose it’s always possible. Both Erik Scott de Bie and Erin M. Evans said that WotC did not impose such restrictions onto them while they wrote their novels, but they’re also more current authors, with Erik’s first FR novel being published in 2005 and Evans’ in 2010. Greenwood has never been so restricted either, but again, he’s an exception, being the creator of the setting and thus granted certain things like anything he says about the Realms is automatically canon. Still, I do think it’s unlikely that WotC was the chief motivator for the conspicuous lack of non-heterosexual males in Bob’s Drizzt books until very recently. Thus, I do hold Bob, and not WotC, accountable for not being upfront with regards to Jarlaxle’s sexuality.

Sorry for the long post, I’m thorough to a fault. XD ]]

#ooc#responses#coffeewyrm#Jarlaxle#Jarlaxle Baenre#Drizzt#drizzt do'urden#legend of drizzt#Artemis Entreri#Entreri#Zaknafein Do'Urden#Realms of the Underdark#The Avatar Series#Double Diamond Triangle Saga#TSR#WotC#Wizards of the Coast#James D Lowder#Erin M Evans#Erik Scott de Bie#Elaine Cunningham#R A Salvatore#Ed Greenwood#Forgotten Realms#lgbt representation#fantasy literature

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Circles of tragedy and How To Act

Clare Finburgh, Senior Lecturer in Drama and Theatre at the University of Kent, responds to How To Act.

A circle. Anthony Nicholl, the “successful theatre director in his fifties” invited in Graham Eatough’s How to Act to give an acting masterclass, asks members of the audience to remove their shoes, which he then places centre-stage to form a circle. Nicholl marks out the circular space in which his participant, the young female actor Promise, will do improvisation exercises based on her own past.

According to Friedrich Nietzsche The Birth of Tragedy (1872), tragedy pulls “a living wall … around itself to close itself off entirely from the real world and maintain its ideal ground and its poetic freedom”.

[1]

Since its ancient Greek origins, tragedy has demarcated itself clearly as an art form distinct from the lives of the audience members watching it, a feature that the circle in How to Act recreates. In this, and in other respects, How to Act returns to the vast scope of the Classics. At the same time, How to Act expands classical tragedy in order to speak eloquently both to theatre today, and to politics today.In a number of respects How to Act, like the “prize-winning tragedians of ancient Athens” to which Nicholl refers, foregrounds its own status as art. Like a classical tragedy, How to Act features a chorus. The chorus self-consciously draws attention to the fact that what the audience is watching, is a piece of theatre. In addition, according to the French cultural theorist Roland Barthes, the chorus constitutes the very definition of tragedy, since it draws attention to the tragic dimension of the play by remarking on it.

[2]

How to Act differs, though, in that the members of an ancient chorus tend to pass judgement on the proceedings in the play, whereas Eatough’s chorus involves clapping and movement, which are performed in the circle. But in the extent to which ancient plays themselves featured song and dance,

How to Act does inherit from classical tragedy.Predating Nietzsche by over two millennia, the first theorisation of tragedy in theatre was provided by Aristotle, whose Poetics stated that the central tenet of tragedy must be one single, unified, clearly defined plot – what Nicholl in How to Act describes as “Proposition – dilemma – response. The fundamental building blocks of drama.” The circular space in which a tragedy is performed becomes a kind of boxing ring, a scene of combat in which conflicts are battled out until their final dénouement. Within the circle, the two conflicting worlds of Nicholl and Promise – male and female, European and African, older and younger, coloniser and colonised – clash. However, the plot in How to Act is far from straightforward. Eatough introduces a play-within-a-play device, where Promise, following Nicholl’s instructions, enters the circle and conducts drama exercises in which she enacts scenes from her childhood in her native Nigeria. When Promise reveals that Nicholl, who had formerly travelled to Nigeria to conduct research for his theatre practice, had no doubt had a brief affair with her mother, it is not clear if she is enacting a fiction, or whether she has actually come in search of the man who might be the father she never knew. Like the French author Jean Genet’s The Maids (1947), where two maids play at being a maid and her mistress; or indeed the most famous play-within-a-play of all, The Mousetrap in Shakespeare’s Hamlet (1599?), levels and layers of fiction in How to Act become entangled, as it is never quite certain on whose behalf the doubled characters speak. Like Shakespeare before them, generations of playwrights have abandoned the unity of an Aristotelian tragic plot in favour of multiple interweaving narratives. Indeed, the mid-twentieth-century German playwright, director and theatre theorist Bertolt Brecht, to whom I come presently, argues that today’s world is far too complex to be encapsulated in a singular dramatic plot:

Petroleum resists the five-act form; today’s catastrophes do not progress in a straight line but in cyclical crises; the ‘heroes’ change with the different phases, are interchangeable, etc.; the graph of people’s actions is complicated by abortive actions; fate is no longer a single coherent power; rather there are fields of force which can be seen radiating in opposite directions.[3]

“The truth is that theatre is dying and we all know it”, declares Nicholl in How to Act.

Whereas Nietzsche entitled his major work The Birth of Tragedy, George Steiner in the twentieth century announced The Death of Tragedy (1961) – the name of his important study. Steiner argues, “tragic drama tells us that the spheres of reason, order, and justice are terribly limited and that no progress in our science or technical resources will enlarge their relevance”.

[4]

For Steiner and other Marxist theorists and theatre-makers, notably Brecht, the incontrovertible fate in tragedy is incompatible with a political commitment to the radical transformation of society: tragedy in art is anti-progressist because it reinforces political fatalism in life. It is important to note that Aritotle’s Poetics does not in actual fact mention fate, although ancient tragedies do often submit tragic heroes to their destiny. Sophocles’s Oedipus is the classic example: before his birth it was predicted that Oedipus would murder his father and marry his mother; and despite his and his parents’ lifelong efforts, this is precisely what takes place. The circle in Eatough’s How to Act thus denotes the inescapable circularity of fate.

The Algerian playwright Kateb Yacine, many of whose works were written during the Algerian War of Independence (1954-62), named his tetralogy of tragedies, which was inspired by Aeschylus’sThe Oresteia, the Circle of Reprisals (1950s). In this series of plays, as in Aeschylus’s House of Atreus in the Oresteia, a closed circuit of violence, an ancestral cult of violence, reprisals, revenge, fatality and failure, become inevitabilities for all of Algeria’s population. Kateb writes:

For me, tragedy is driven by a circular movement and does not open out or uncoil except at an unexpected point in the spiral, like a spring. […] But this apparently closed circularity that starts and ends nowhere, is the exact image of every universe, poetic or real. […] Tragedy is created precisely to show where there is no way out, how we fight and play against the rules and the principles of “what should happen”, against conventions and appearances.[5]

This resignation to a doctrine of circular fate is illustrated when Promise in How to Act says:

It’s all been written for us hasn’t it? Sometime in the past. Before we met anyway. Before you met my mother even. None of it could have been any other way. You thought you could make a difference. Control things. Control the story. But it’s not yours to tell. You’re just a part of it. Like we all are. You’re just in it. Subject to it. It’s all been decided. Who we are. What we mean to each other. How this turns out. I was always going to find you. Come back to you. Like a curse. Show you who you really are. A liar. That’s how this ends. There’s no escape.

It is precisely this belief in the circle of fate and the absence of a possibility for escape from this circle, that has been rejected by Marxist playwrights and directors like Brecht.

Instead of submitting to a destiny of suffering, for Brecht, characters – and the audience – must seek to understand the reasons for suffering, and to redress the social and economic injustices that cause that suffering. Marxist cultural theorist Walter Benjamin, Brecht’s contemporary, explains how Brecht’s politics distinguish between simplicity and transparency. Simplicity denotes the defeatist acceptance of misery and resists challenge to the status quo: “That’s just the way it’s always been”; transparency, on the other hand, rejects the mystifications that lead society to believe that suffering is universal and eternal. Erwin Piscator, a Marxist dramaturg who was also contemporary to Brecht, summarizes how tragedy is the result not simply of fate, but of political and socio-economic circumstances:

What are the forces of destiny in our own epoch? What does this generation recognize as the fate which it accepts at its peril, which it must conquer if it is to survive? Economics and politics are our fate, and the result of both is society, the social fabric. And only by taking these three factors into account, either by affirming them or by fighting against them, will we bring our lives into contact with the “historical” aspect of the twentieth century.[6]

In How to Act, the causes of suffering on the African continent, notably in Nigeria, are given clear explanations by Promise. As Brecht highlights in the quotation to which I have already referred, “petroleum” is one of today’s most pressing and complex problems. Promise explains how, in spite of Nigeria’s vast oil wealth, it has been crippled by “debt to western governments and the World Bank.” In addition, she describes how “western oil companies” such as “Shell, Exon, Chevron and Total” have not only made many billions of dollars of profits out of Nigerian oil and gas and massively expanded the west’s consumption of energy and goods while their employees live on “less than a dollar a day”. In addition, these oil companies have committed human rights abuses by encouraging the Nigerian government to execute activists campaigning for social and environmental justice. These perspectives provided by the play engage directly with current geopolitics, since in June 2017 the widows of four of the nine activists extrajudicially executed in 1995 by the Nigerian government for campaigning against environmental damage caused by oil extraction in the Ogoni region of Nigeria, launched a civil case against Shell, accusing them of being complicit in the torture and killings of their husbands.[7] While inheriting from classical tragedy, How to Act conducts, in parallel, a typically Marxist analysis that seeks out the causes for suffering, rather than submitting to them. “[Y]our having everything depends on us having nothing.”, admonishes Promise.

In Theatre & Ethics, Nicholas Ridout defines ethics by posing the question, ‘Can we create a system according to which we will all know how to act?’

[8]

By admitting to the reasons for social, economic, gender and environmental injustices, we can strive towards an ethics of “how to act”, as the title of Eatough’s play suggests.

In some respects How to Act could be described as a postcolonial play, or at least a play that examines and exposes the afterburns of British colonial occupation in Nigeria. The Nigerian playwright and Nobel Laureate Wole Soyinka, rather than dismissing tragedy outright, argues for the “socio-political question of the viability of a tragic view in a contemporary world”. For him, as he demonstrates in some of his great tragedies, notably Death and the King’s Horseman (1975), the theosophical school which would accept suffering and death as the natural order of things, and the Marxist school which insists that the historical reasons for human suffering must be explored, understood, and rectified, can indeed be encapsulated in the same play (1976: 48). Graham Eatough demonstrates, as Kateb Yacine and Wole Soyinka have done before him, and as authors such as the Lebanese-born Quebecan playwright and director Wajdi Mouawad continue to do today, that tragedy is an enduring form that can not only affirm the inevitability of suffering and injustice, but can also candidly expose the reversible reasons for that suffering. There are economic, social and political reasons for tragic suffering which must be comprehended and apprehended, in order to effect change. These artists replace circles with spirals, and spirals have an end.

[1] Friedrich Nietzsche, The Birth of Tragedy, trans. Shaun Whiteside, London: Penguin, 1993, 37-8.

[2] Roland Barthes, “Pouvoirs de la tragédie antique” [1953], in Ecrits sur le théâtre, Paris: Seuil, 2002, p. 44.

[3] Bertolt Brecht, Brecht on Theatre, trans. John Willett, London: Methuen, 2001, p. 30.

[4] Steiner, George. The Death of Tragedy. London: Faber & Faber, 1961, p. 88.

[5] Kateb Yacine, “Brecht, le théâtre vietnamien : 1958”, Le Poète comme un boxeur : Entretiens 1958-1989, Paris: Seuil, 1994, p. 158, my translation.

[6] Erwin Piscator, The Political Theatre [1929], trans. Hugh Rorrison, London: Methuen, 1980, p. 188.

[7] Rebecca Ratcliffe, Ogoni widows file civil writ accusing Shell of complicity in Nigeria killings, The Guardian, 29 June 2017, https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2017/jun/29/ogoni-widows-file-civil-writ-accusing-shell-of-complicity-in-nigeria-killings.

[8] Nicholas Ridout, Theatre & Ethics, Basingstoke: Palgrave, 2009, p. 12.

HOW TO ACT Written and directed by Graham Eatough.

Internationally-renowned theatre director Anthony Nicholl has travelled the globe on a life-long quest to discover the true essence of theatre. Today he gives a masterclass. Promise, an aspiring actress, has been hand-picked to participate. What unfolds between them forces Nicholl to question all of his assumptions about his life and art.

https://www.nationaltheatrescotland.com/content/default.asp?page=home_How%20To%20Act

0 notes