#this is probably dialectal but also very common

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

9 lil things abt the way some ikevil chars speak in japanese you probably didnt know

in the jp version, even after getting into a relationship, kate actually still consistently calls elbert with his title, “lord elbert” [エルバート様] (erubāto-sama). in jp, the only ones who do not use the honorific would be victor, william, and on occasion, alfons, who seems to switch between [エル] (eru), [エルバート] (erubāto), [エル様] (eru-sama), and [エルバート様] (erubāto-sama) on a whim.

in case en doesnt localize this well or fully when it does come…there is a time when victor switches his personal pronoun from [僕] (boku) to [俺] (ore). these words mean the exact same thing (i, me, my, etc), but the latter is meant to have a more “masculine” feel. [僕] (boku) is used quite a bit by boys as well (in fact, ellis’ personal pronoun is [僕]), but it can also treated as a sorta “gender-neutral” character in songs, for example, and girls can use [僕] as well. on the other hand, you wouldnt ever see a girl using [俺].

nica has an interesting…speaking quirk, where certain words that should be written in hiragana r written in katakana. for example, he might say [イイ] (ī) as opposed to [いい] (ī), or [ホント] (honto) rather than [ほんとう] (hontō), [ワケ] (wake) over [わけ], [てアゲル] (—te ageru) over [てあげる], etc. this is likely a “personal style” thing to make him seem more flippant, cuteish, or youthful. this kind of thing is also more common in fictional characters who were raised abroad.

darius uses [ほっぺ] (hoppe) to say “cheeks”. the traditional way to say cheeks is [頬] (hoho). they mean the exact same thing, but saying [ほっぺ] (hoppe) to refer to cheeks has a childish or “innocent” air to it, partially due to the way its written entirely in hiragana. he does tend to have a childish air abt him, and this is probably one of the most direct examples of his childishness when it comes to the way he speaks.

alfons changed his way of speaking at some point after entering the greetia manor. before then, he often used more casual speech, known as [くだけた表現] (kudaketa hyōgen), but eventually he changed his way of speaking to whats known as [です・ます] (desu•masu) form, even using [敬語] (keigo), which is like very polite or humble japanese with their own set of vocabulary and conjugations. this is likely due to becoming elbert’s “attendant.” so he likely had to speak that way and it may have just become a habit or a sort of integral part of his identity, as he uses this language even after getting into a relationship with kate.

another tidbit of victor: he often — for example — ends questions with [かい] (kai). the other way to end questions in japanese would be to just use [か] (ka). but by adding [い] (i) to it, it can add emphasis or “soften” the tone. its mostly used by men, and using such a form is often associated with older men and women (40+), but younger men can use this too.

it might be more noticeable with jude bc he originally speaks in a whole different dialect [関西弁] (kansai-ben), and will switch to queens english, i.e. standard tokyo japanese, for business related reasons or if he feels its necessary to for a reason. but roger also can switch his way of speaking as well. he would mainly do this with ppl hes not well acquainted to or with well respected personages. he normally speaks pretty casually in japanese, shortening words or phrases, though not speaking in a different dialect. for example, he might say [そりゃ] (sorya) instead of [それは] (sore ha). but in certain situations, he might opt to use [それは].

william and elbert speak in the same form [だ・である] (da•dearu) due to the fact they r nobles — such a form comes off as more direct, imposing, or just strong in general — but they also do have their own “speaking quirks” as well. for example, when saying the word “but” or “however”, will often uses the word [が] (ga), while elbie opts for [けれど] (keredo). will also tends to end his sentences or remarks with [だな] (da na), something that elbie does not really do. that said, the way they both say “yes” is the same: [ああ] (ā).

kate uses honorifics with ring, specifically [くん] (—kun), when requested by ring to not be so formal with him (btw kate also uses [くん] with ellis), but when ring refers to kate by her name rather than “robin”, he doesnt use any honorific on her. on the other hand, nica continues to call her “robin” / spatzi / rotkehlchen what have you, but asks her to not use [さん] (—san) with him at all. so kate just calls him [ニカ] (nika). not using any honorifics is what’s known as [呼び捨て] (yobi-sute), and its smth that should really be done with ppl you feel v close to or with family (or otherwise its incredibly rude), but kate probably only did so with nica at that pt so she could respect his request, rather than an actual feeling of closeness.

246 notes

·

View notes

Text

Headcanon: one of the reasons why Gallifreyan is a) so complex, and b) so inconsistent, is because it's less one language and more a complex mishmash of thousands of languages and dialects.

Think about how one of the reasons English can be complex to learn is because of the mix of Germanic and romance language roots, and now take it up to 11.

While one might expect Gallifrey to be monolingual, given its age and class structure, this probably isn't technically the case. After all, why limit your culture to one language when the average citizen is effectively panlingual (to the point that TARDIS translation circuits are actually dependent on their pilots' knowledge, rather than the other way round)?

Thus, if there once were distinct languages on Gallifrey, they probably have all been merged at this point into modern Gallifrey's super-Esperanto. Add in loan words from notable civilisations across all of spacetime (but likely primarily from Gallifreyan colonies and allies like Dronid, Minyos, Cartego etc.), and it quickly becomes quite unwieldy.

It's also likely that there's a lot of overlap between these sub-languages, which can make distinguishing meaning hard to an outsider. Gallifreyans likely get around this courtesy of their telepathic connections.

TBH, given Time Lord sensibilities, it's likely that every single word variation has its own delicate meanings, derived not just from their societal uses but also from the etymology and history of each one. Canonically (though I don't have a source) we know that there are 30 different words meaning "culture shock", for example, which likely have very minor distinctions in meaning. We also know, unsurprisingly, that there's at least 208 tenses to help in describing time travel.

As an example - imagine being a Sunari ambassador at an embassy gathering and accidentally offending every Time Lord in the room because you accidentally used a definite article derived from the memeovored Old High Tersuran colony dialect, now considered low-brow by association with modern Tersuran, when you intended to use a nearly identical form of the word originating from the Founding Conflict, a triumphant post-Rassilonian intervention, distinguished by a near-imperceptible glottal stop.

It's likely that some of these Gallifreyan sub-languages/dialects may still be spoken with increased frequency under certain conditions, such as in one's own House or when visiting other city complexes. We know, for example, that Arcadia seems to be associated with a "Northern English" accent (which Nine picked up subconsciously post-regeneration, with the Fall of Arcadia being one of the last things the War Doctor remembered before DOTD's multi-Doctor event - hence "lots of planets have a north") when translated, which may indicate some dialect differences in the original language. I suspect there is a societal expectation for Gallifreyans to code-switch depending on the situation, with Citadel business generally expecting the Gallifreyan equivalent of RP, though it's relatively common for Time Lords less concerned with respectability and politicking to not comply.

One nice benefit of all this complexity, and the reason I made this post, is that there's a good argument to be made that every fan attempt to construct a Gallifreyan language can be 'canon', contradictions and all.

Greencook Gallifreyan? A formal evolution of Pythian prophecy scripture into the post-Intuitive Revelation era (based on its similarities with the Visionary's scrawling in The End of Time).

Sherman Gallifreyan? A modern katakana-like phonetic alphabet for the rapid-onslaught of new loan words following President Romana's open academy policies. Recently adopted by the Fifteenth Doctor for writing human proverbs.

Teegarden Gallifreyan? An archaic but recognisable near-Capitolian dialect from the Prydonian mountains, once spoken by Oldblood houses like Lungbarrow and Blyledge.

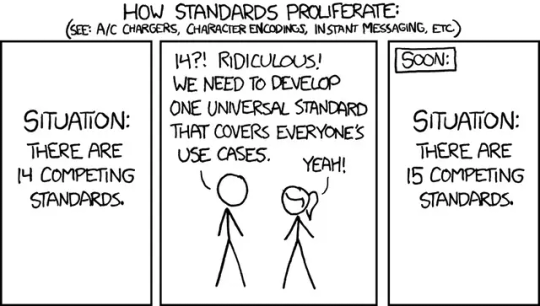

Or, in a nutshell, the state of Gallifreyan conlangs (and maybe in-universe Gallifreyan dialects):

I guess the dream project would be to accept the complexity and create some sort of grand modular "meta-Gallifreyan" conlang, merging as many fan interpretations as possible with their own distinctions and overlaps, that can continue to be updated as new ideas come up and new stories are released...

211 notes

·

View notes

Text

Different Languages AU Part 1: Wait, Fuck, They Don't Speak Basic?

First things first motherfuckers, let’s get one thing straight: Basic as a language does exist in this AU! It’s just less common outside of the Core/Mid Rim. SO. What does that give us? Well, it gives us way more interesting conflict, for one thing, and for another, so many languages. Let’s get crackalackin!

In the Outer Rim, Huttese is largely The Language To Speak. If you don’t speak Huttese, you might as well just hurl yourself into the nearest bottomless pit now and save yourself the time and trouble. Even in the Core and Mid Rim, Huttese is a very common language just because of how useful it is if you ever find yourself in the Outer Rim. Most bounty hunters (i.e. Jango Fett, just for one completely random example) speak Huttese fluently, alongside their native languages. Naturally, then, this is a language Anakin is very familiar with. In fact, when he became a Jedi, it was the language he knew the best, and most people thought his speech was stilted in Basic because of this. He spoke Basic maybe once every month on Tatooine—can you blame him?

In the Mid Rim, each planet has their own language and conversations between diplomats are typically done as they are on Earth—via interpreters, to avoid any misunderstandings. Padmé, for instance, does speak Basic, but that is the language she would use in the Senate, not on Naboo. The same goes for Palpatine, but we’ll get to him in a minute, because he sucks and I want to not talk about him for as long as I feasibly can.

The Core means Basic, Basic, Basic, because of just the sheer number of people making it necessary. Coruscant is a weird case because of how communities develop there. Since it’s kind of like a gigantic version of a modern city (I’ll use NYC as an example because I know it the best), it’s broken up into enclaves. Cultures clump—it’s a thing. Some neighborhoods in NYC are predominantly Jewish, some are predominantly Italian, the list goes on. The same goes for Coruscant, although on a supersized scale. There’s some areas where non-Mandalorians need not apply, some where everyone is a Twi’lek or Togruta, some where everyone is a Mirialan, et cetera. Also, Coruscant dialects of certain languages are very much a thing.

Anyway. Let’s talk Kamino, because that’s why I started this to begin with!

Jango Fett is a Mandalorian. He’s also a bounty hunter. He’s from Concord Dawn and was a True Mandalorian. Therefore we can guess he probably at the bare minimum speaks two dialects of Mando’a (Concord Dawn, True Mandalorian) Huttese, and has at least passing Basic. He probably speaks more than that given how well-traveled he is, but those are the ones I can name for sure. So Jango Fett, who speaks Mando’a and Huttese and Basic, encounters Count Dooku. Count Dooku is from Serenno, but he was also a Jedi, so he probably speaks Serennese, Basic, Huttese, and a few more. He may even speak Mando’a, but his dialects wouldn’t be likely to overlap with Jango’s. Count Dooku tells Jango to go to Kamino and let them clone him in exchange for an exorbitant amount of money. Jango does, because Jango is a thinking human being and thinking human beings under capitalism do not turn down exorbitant amounts of money in exchange for what amounts to (at most) being a three or four-time sperm donor.

And on Kamino, our intrepid Mandalorian encounters something a bit weird. The Kaminoans, being that they are an extremely isolated species and thus have absolutely no reason to have developed humanoid vocal chords, have to rely on droid translators. Cool! This means Jango can speak to them exclusively in his native language (Concord Dawn Mando’a), and they can speka to him exclusively in theirs, and everyone’s largely happy. Jango negotiates the finer points of the contract, acquires an infant who he names Boba, and calls up some old friends (and acquaintances) to teach the clones to kick ass. He informs them they don’t have to worry about speaking Basic, so they don’t bother speaking Basic.

Thus, we have our setup. The Kaminoans have no reason to make the clones speak Basic because literally none of these outsiders are bothering to inform that oh yeah there’s this whole common language thing going on, and said outsiders have no reason whatsoever to tell them because it would ultimately just be an inconvenience. They’ve got a good thing going, and Jedi are required to speak more than one language anyway. The clones can definitely find at least one in common!

So the clones learn to speak Mando’a, understand Kaminoan, and speak and/or understand one extra elective language. Most pick something weird because they can—everyone around them speaks either Mando’a or Kaminoan so why would they bother with languages they don’t care about, like Basic? Unfortunately for the Kaminoans and the trainers in equal measure, they do also realize that in order to express themselves in private they need their own universal language, so they acquire one. They just call it clonespeak to keep things simple, and for most of them, that’s their native language. They feel most comfortable speaking in it because that’s the language they associate with safety and with their siblings/parents.

Thus: the predicament.

Obi-Wan arrives on Kamino. Obi-Wan is a Jedi. Obi-Wan speaks Basic.

Uh-oh. See, Jango is out of practice—the Kaminoans can’t make those noises. Boba’s language skills begin and end with Mando’a and some random bits of clonespeak right now—he’s kind of conversational with Huttese but every once in a while he just throws in a Mando’a word or an idiom in clonespeak and Jango has to take a minute to breathe lest he slam his head straight through the wall in frustration because he doesn’t understand clonespeak. And so much performing of charades, many awkward moments, and exactly one sentence in Basic later, Obi-Wan is heading back to Coruscant with several questions.

First: why the fuck did Sifo-Dyas order an army who didn’t speak Basic? No one knows. No one can find any records of this order, for one thing. No one knows who Tyrannus is, for another.

And second: what languages do the clones speak? Obviously, Mando’a is amongst them, but Jango’s extremely intensely staring son also spoke another, infinitely weird language and no one can find any record of it, and not even Jango seemed to understand him. Do they understand the Kaminoans’ clicking noises? Are they just mute? Is it constantly Shut The Fuck Up Friday up in there? What is going on?

The Council loses their collective minds. Shaak Ti is about ready to haul ass across the galaxy to collect these poor, lost young men—Plo Koon is right there with her. Yoda is—well, Yoda is swearing loudly in several dead languages right now. Mace Windu, ever the voice of reason, just has one thing to say: how about they meet the clones, first. Before they panic.

In the face of this intense, all-consuming, glorious sensibility, the Council collectively shuts the fuck up. They decide to let things run their course.

And then Geonosis. Quickly, Yoda collects several hundred clones, manages to communicate to one of them—who speaks a really weird, ancient, and fucked up dialect of Basic that could basically scan to Elizabethan English, and whose name is probably Kowalski—what he needs, and that one tells an older, larger and more intimidating one. Then that one yells a lot in a language Yoda has never heard before, and several hundred clones are suddenly hauling ass into gunships.

Enter one Anakin Skywalker and one Padmé Amidala, who are about to acquire some friends, none of whom understand a word they’re saying. They fuck some things up, get strapped to some poles to be devoured by Space Beasts of some sort, and then escape.

Battle of Geonosis happens. Mace Windu quickly discovers that the answer to the question what do the clones speak is effectively every language except Basic, and the answer is also supremely inconsistent. He is Suffering. He is Experiencing The Horrors. Obi-Wan is likewise fighting for his life because he speaks a fancy-ass dialect of Mando’a that the clones don’t understand. This is because they, like normal people, don’t talk like dignitaries on diplomatic missions.

Moving on! Obi-Wan gets assigned Alpha-17. Alpha-17 is a demon. Actually. He probably speaks Basic but refuses to out of spite. This is the biggest asshole to ever stomp his way into a Venator and terrify Anakin Skywalker into cowering submission. (He may even be why Anakin behaved like that as Vader. We will never know!) Like most clones, Alpha-17 speaks four languages. Clonespeak, Mando’a, Kaminoan, and Huttese. In that order. So he has no real trouble communicating with either Anakin or Obi-Wan.

What he does have, though, is a surplus of kids. Like it or not (he insists he doesn’t) they are his kids, and he wants them to have a shot at having a moderately tolerable existence. Enter everyone’s favorite group of six weirdos: Wolffe, Ponds, Fox, Bly, Cody, and Rex.

Wolffe is easy. He’s horrible with languages, and so gets sent to Plo Koon, who speaks through a translator anyway. Add Mando’a to the translator, and bang! Easy. Done. They understand each other perfectly.

Ponds is also easy. He, being sensible, learned Basic, so he goes to Mace Windu, who is equally sensible (and grateful for the easy transition).

Fox, who is a scheming little shit and also just so happens to speak Naboo, get sent to Coruscant. The Chancellor can’t get one over on him if Fox can understand every word he says, and most Senators have protocol droids with them for translation anyway.

Bly speaks Ryll, so she gets Aayla Secura. Again, easy.

Cody, on the other hand? Cody speaks the same languages as 17. Cody has a favorite younger brother who needs guidance. Cody, therefore, gets deposited with Obi-Wan, and Rex? Rex gets Anakin.

But the issue with Rex is he and Anakin have no language in common. Rex’s elective language was Togruti, and like the rest of his batch he also speaks Tusken sign. Because his batch are a bunch of assholes who wanted an extremely private way to talk.

So. Anakin and Rex start off the war with no way to communicate! None! Literally not one language in common!

And they do try to communicate—via charades, via text, et cetera—but they don’t really have access to translation software on a regular basis and thus things become complicated.

Things are made even more complicated by the fact that Rex, like Wolffe, is shit at language learning. Anakin, who isn’t, could try to learn clonespeak, and does! But when you can’t communicate with the person teaching you it is immensely slow going.

And thus, our premise is complete. How do you run a war with someone you can’t talk to?

Well, it depends. If you’re Anakin, you say, maybe I can figure a way around this.

If you’re Pong Krell?

I dunno man. Yell? Yeah, that sounds about right.

#hahaha#heeeeere's nonsense!#lee writes#different languages au#star wars#tcw#jango fett#obi-wan kenobi#anakin skywalker#alpha-17#commander cody#captain rex

253 notes

·

View notes

Text

Interesting Kisame Notes:

Some of these I think are common knowledge in the fandom at this point, but in case they haven’t reached some ears yet I’ll list them anyway.

His characterization is totally different in Japanese vs English dub, partly because his English VA typically voices utter meat-heads and given that Kisame looks like he would be, I guess it fits…buuuuuut it really doesn’t lol. In English, Kisame is very blunt and sounds pretty aggressive; but in Japanese he’s almost the total opposite:

The dialect of Japanese that Kisame speaks is called Keigo, which is a very old dialect spoken predominantly in Kyoto. It’s extremely formal — the nearest English equivalent dialect I can think of would be an amalgam of 1860’s Victorian High London English. Which is about the right time period, actually, that keigo sorta “belongs” to. (Meiji Era). I could go on trying to explain it, but the gyst is that Kisame is very formal and sometimes a little rude — there is, in fact, a register in Keigo that allows you to be both simultaneously— but he’s also meek. He’s non-committal and generally soft-spoken, even though he’s got an impressive and commanding presence. He doesn’t exactly minimise himself in a physical space or manner, but he definitely comes across like he’s trying not to “be the big baddie”, contrary to his English VA. He also refers to Itachi as -san even though by all rights he ought to use -kun, given that Itachi is 11 years his junior, which is a much loftier raise in respectful position than it would seem (all the moreso because Itachi is a little shit to him at first lol).

Kisame likes to fight, BUT he likes to fight fair. I have many disagreements with the Wiki, but this is probably my biggest gripe about Kisame on there. He’s demonstrably an honorable person, when he can afford to be. Kisame does taunt his opponents occasionally, but it’s never really anything more, and it’s clearly more for fun than for goading. He never mocks them, though, not even when they’re very clearly outmatched, and he is curiously fond of complimenting his opponents, again even when outmatched. He’s also quite patient, albeit not as much as Itachi, but that I think comes down to their fighting styles more than anything. Itachi prefers a defensive approach, aiming to disarm, whereas Kisame has a much more smash-n-grab approach, wearing his opponent down in a contest of stamina and brute force. (Truly, these two are terrifying when you consider what they’re capable of when coordinating together.) either way, Kisame reminds me of an old Samurai in some ways, in that he follows a code, although maybe it’s one only he knows, and he sticks to it.

Kisame is very probably based on a Youkai called either the Koujin or more often Samebito. Or at the very least the Hoshigaki clan is likely inspired by the myth. Samebito are shark merfolk, essentially, and look pretty terrifying, but they’re actually quite benevolent to benign towards humans. In their mythology they specialize in making textiles of a special silk that’s entirely waterproof and very tough. They’re also, being water Youkai, very sensitive and often emotional creatures, which like some other youkai, cry tears that can crystallize into precious stones. (Water is the element of emotion). There’s a particularly famous story about one, which I won’t get into here — but the ways in which the myth reflects the man are such: Samebito are incredibly loyal to people that help them, and will literally hurt themselves or even kill themselves to help a friend or ally. They also have an honor system, one which prioritizes hospitality and fairness. They may not necessarily go out of their way to help a random human, but they’ll save people from drowning and if you do right by them, they’ll be sure to return the favor.

Kisame and Jiraiya are almost the same height. (Kisame 195cm or 6’4 3/4”, usually rounded up to 6’5” in the data books, Jiraiya is 191cm, about 6’3”) . They both are the tallest characters in manga canon, followed by Gai at 184cm, 6’0”.

Something that frequently goes unmentioned is that being one of the 7 swordsmen is more than just a title in Kiri, it awards you a special government role. What exactly that role is, is a bit up in the air, but we know that the swordsmen commanded units, and could command ANBU if they saw fit to. It’s also implied that there’s desk work and other managerial responsibilities associated with the position, which makes sense if we’re going the military commander route. Now obviously some of them were total whack jobs, but the fact nobody except arguably Mangetsu really liked Kisame, (we don’t know about Zabuza, but Kisame’s reaction implies they minded their own business when it came to the other) it’s interesting to think about how exactly that came to be. Cause Mr. Lightning Boy (I do not remember his name) that turns up in part 1 anime is not the sort I envision doing diligent paperwork or anything like proper commanding lol. I know I’m solidly in HC territory here, but I can envision Kisame actually trying to do his job as it says on the tin and every other swordsman looking at him like he’s nuts for sticking to his principles instead of buying into the corruption lol.

In other HC territory that is sort of canon-ish but I guess got retconned for plot or something: Kisame has a PHENOMENAL sense of smell. He’s a very good tracking nin. He’s a sensing type, with added sharky benefits. (Sharks can sense electrical activity in the muscles of prey, so I imagine Kisame is Extra perceptive.) Ergo, it has not ever once made sense to me that he’d of been genuinely surprised by the Tobi/Madara reveal. Unfortunately the tone he uses in Japanese is extremely neutral, so it’s (possibly deliberately) hard to read into. Is he being sarcastic? I’d like to think so, given what canon presents us with, but this is Kishimoto we are talking about lol. In case it’s not clear, I find it Highly doubtful that Obito could have completely changed his scent AND chakra signature beyond recognition, and the fact Itachi knows he’s playing pretend sort of leans into Kisame being aware of it, because I doubt Itachi could really keep his own skepticism under that tight of lock and key. Not around Kisame.

Alrighty, it’s 5am and I need to sleep 🤣 so take this as ye will for now

103 notes

·

View notes

Note

maybe the most difficult worldbuilding question of all, what are some popular jokes in your setting? what about ones based on the vocabulary you have established so far, but which just don't translate to english?

I only have one thing established that is purely a Joke that isn't translatable to english-

A lot of Wardi dick jokes revolve partially around this animal, the long-suffering hippegalga

The name 'hippegalga' means 'little horn'.

Hippe/hippi is a somewhat antiquated word for 'small/little', in contemporary dialect it's still recognizable as having connotations of 'small' but isn't commonly used in actual vocabulary (you'll find it more often in names). Galga was originally one of several words for 'horn', in this case broadly pertaining to the horns of antelope ('meti' is the most generalized word for animal horns, while specific animal groups (antelope, khait and cattle) have their own horn words.

Hippegalga horns are considered to be notably phallic among all animal horns (big male hippegalga tend to have horns approximately the size of an average human penis) and are ascribed beneficial qualities for male development and fertility (taken powdered as medicine and/or worn) while also serving the non-sexual functions of a general phallus when worn as an amulet.

The word 'galga' or its shortened 'gal' tends to be used on its own specifically for this animal's horn (ie: if you're describing a hippegalga's horn, you just say 'galga' instead of 'hippegalga galga', while if you were describing another antelope's horn you Would say '[antelopes name] galga'). Because of this, the word has greatly absorbed the animal's phallic connotations while still retaining the meaning 'horn'. As such, galga/gal has earned additional meaning as euphemistic slang for 'penis' in common dialect.

The name 'hippegalga', which once had absolutely no penis connotations, now sounds to most Wardi speakers like you're saying 'small penis'. It's like if in english there was a very common, well-known backyard bird called the 'little cock'. You'd know damn well that it's not Supposed to mean 'little penis', you'd know that the bird was probably named before 'cock' became more commonly used as penis slang than a word for 'male bird', but it sure is a funny name.

What's more, hippegalga are VERY common wild animals that adapt well to urban environments (they're basically as ubiquitous to urban areas as squirrels) and are very tameable and kept as pets. Their ubiquity and familiarity makes them very fertile ground for dick jokes and innuendo.

So you'll see 'hippegalga' used as a basic slang term for 'small penis' (ie: "I saw his hippegalga the other day"), or used in more complex ways in comedic plays/poetry/etc as a euphemism IE:

"he left to tend to his hippegalga" - innocently meaning "he left to feed his pet antelope" while strongly implying "he went off to crank his (notably small, which is funny) dick" "she was disappointed to find a herd of hippegalga waiting at her door" - innocently meaning "she was annoyed that a herd of little antelopes were blocking her doorway", and depending on the context could imply something like "she found a bunch of disappointing, impotent male suitors lurking around her doorway" or "she's having sex with several men and is disappointed to find their dicks are small"

(TANGENT: average sized penises are culturally considered ideal, with notably large penises implying an outsized libido and un-masculine lack of self control, and notably small penises implying sexual impotence and general weakness. It tends to be assumed that if a woman has an outsized libido she will be interested in men with larger penises)

Gal(ga) as euphemistic slang for penis plays into the name of gannegal soup, which is a dish that contains bull penis as one of its ingredients. 'Gannegal' is effectively a double entendre. You're not saying 'ox penis' soup (that would be 'ganne gemane'), the dead literal translation of gannegal IS 'ox horn'. But this is not the Naturalistic way you would say 'ox horn' either, because 'gal(ga)' is not used for the horns of cattle (you would say 'gannemitla' or just 'mitla'). So like to a Wardi listener the name 'gannegal' is politely saying 'ox horn' while heavily implying its contents of bull penis.

"Gal(ga)" as both a word for horn and slang term for penis has a lot of other applications in jokes/puns/euphemisms.

I don't have the words established for the full Wardi language version, but a phrase that translates to "a hawk carrying a bull by the horns" (using 'galga' instead of the naturalistic 'gannemitla') is used to describe a woman as sexually domineering, or to describe a couple being consisted of a conniving sexually controlling woman and a weak-willed libidinous man. The imagery is a small predatory bird controlling a physically superior, powerful animal, and implying via 'galga' that the control is sexual in nature. It's usage is Kind Of similar to 'henpecked husband' in implying a man as weak and overly controlled by his wife (with acutely misogynistic undertones that he's a failure in that he should clearly be the dominant party instead), just with an explicitly sexual layer.

There's also variants like "he's a bull led by his horns" as something you might say about a superficially powerful man that you're implying is mentally weak (the galga euphemism implies this mental weakness is specifically lack of sexual control, but this phrase is sometimes used in more generalized contexts).

---

This one's less of a joke per se, but "digging out the viper" "digging out the viper's tail" "digging out the tail" is a saying that describes something as a high effort and utterly futile exercise, a doomed vanity project, etc.

This refers to the Viper seaway, which is named for its fat snakelike shape. The 'tail' of the Viper dead-ends about 50 miles away from the actual ocean, which makes this sea ultimately unimportant in the larger sea trade system (you don't have to enter its waters at all to get to any major trade hubs). However, it would become EXTREMELY important to sea trade if someone managed to dig a canal between the Viper's 'tail' and the eastern sea.

This would be very difficult- a lot of the terrain is rocky and hilly (the actual canal might have to be closer to 70 miles long AT MINIMUM to work around the terrain). The people who actually live on this land (mostly Ubiyan pastoralists) are not heavily involved in the sea trade system, and most of their communities have never particularly wanted foreigners digging a huge fucking canal through their lands and building up a sea trade hub around it.

So, there have been at least two major historical attempts to dig the canal, both of which failed. One was through a strained alliance of Royal Dain kingdoms, and one was an attempt by Imperial Bur at its height (in which it controlled all the coasts on the south end of the Viper, among other places). Both failed spectacularly, due to a combination of logistical issues (the sheer scale of manpower needed, feeding this manpower, and sustaining the endeavor), internal political disagreement on the projects viability, and organized reprisals from the Ubiyan population. As it stands, the attempted canal exists as about 20 miles of shallow ditches, heavily eroded and washed out by rain.

The idea of digging out the canal now tends to be regarded as a spectacular and utterly futile act of hubris, to the point that variants of "digging out the Viper" as an expression of futility exist in Wardi, Burri, Dain, Finn, and Ubiyan languages.

The saying itself isn't quite a joke, but can very easily be Used in jokes and wordplay: IE in a play where the stock Arrogant Idiot character excitedly goes off to fight a group of bandits singlehandedly, you could see an exchange between other characters like "What did he say he was going to do?" "He said he has to go dig out a viper's tail" (which would not be regarded as uproariously funny but would probably elicit a chuckle from the audience).

This saying also lends itself to more sexual wordplay in that one partly antiquated word for tail (cunna) is now mostly used as slang for anus (though is still Recognizable as having meaning as an animals tail). (Kind of like in american english how most people Know the word 'ass' has meant 'donkey' for most of its history, but you don't often see it used as such).

The related word 'cunnari' stems from it (this is untranslatable, it dead literally means 'anus person') and is used to describe someone as passive in anal sex. This is Extremely insulting to use on a man (probably the closest approximation to 'faggot' in this language, though with different connotations) and degrading even when not.

A man (at least rhetorically) threatening to sexually penetrate another man is kind of like saying "I'll make you my bitch". So you might see variants on "digging out the viper's tail" which use the word 'cunna' for tail to mock an instance of this alpha male type declaration. IE: in the context of a play, this type of threat might be responded with a "ha, good luck digging out my tail" (your threats are laughably futile) or a more elaborate sort of "do I look like a viper to you? I can see why the likes of you is so interested in my tail" (you must be fucking stupid, you're the type to engage in hopeless endeavors of vanity). Etc.

On the other way around you might see 'cunnari' slipped into reversals of 'digging out the tail', ie: "he'll have no troubles digging out that cunnari", "If only the Viper was a cunnari, he'd have spread his tail wide open and saved Old Bur all its trouble". Etc

121 notes

·

View notes

Text

i'd like to think that the island of mideel is a sort-of ff7 universe equivalent to real-world iberian peninsula, with banoran being portuguese and mideelian being spanish. it's not as simple as that, of course, as (specifically european) portuguese and spanish are very different languages despite sharing approximately 89% of their vocabulary

but i'd like to think that it's a good basis for developing language and cultural headcanons for mideel. banoran is the far smaller language, with all of the residents of banora being expected not only to learn mideelian but also common at a very young age. their culture is similar to the rest of mideel while staying distinct, partially due to the influence of shinra moving their staff there around the time of gillian hewley's house arrest and partially due to natural cultural development differing despite small geographical distance

people from mideel generally don't learn banoran - they understand enough of it and why bother to learn such a small language if all the residents speak mideelian anyway. there are of course exceptions, but mideel in general also has very complicated views on banora due to shinra's influence over the time and banora's sudden rise to fame with its banora white production. it sucks to live so close to the source of the best fruit in the world but mostly losing access to it due to all of it being either processed into juice and other food items or being exported to midgar and the gold saucer

both genesis and angeal learn mideelian before they learn common, but by the time they join shinra they are more than fluent in all three languages, with only a mild accent betraying where they're from. genesis does more than angeal to hide his accent. while he's not ashamed of where he's from, he embraces the city life of midgar with all he has, even if it means picking up the same odd way sephiroth speaks. it's a lot of effort and whenever he gets top emotional he stops caring. angeal doesn't care. as long as he's understood he doesn't give a shit if he has a perfect midgar dialect or not

they still speak banoran together whenever it's just the two of them, and after a while they start to teach sephiroth some of the words. they're proud of their language and culture and will always always be quick to correct people when they say they're from mideel (we're from banora, you utter imbeciles - genesis, probably) because at the end of the day, it is its own distinct place with its own history, similarity to mideelian language and culture or not

#ff7#genesis rhapsodos#angeal hewley#crisis core#my headcanons#ff7 tag#look im going on about languages again

61 notes

·

View notes

Text

okay SO. it took longer than I expected for various life reasons but here is the massive conlang masterpost, featuring all the languages and prominent dialects that I imagine would exist within the grishaverse. under a cut bc it got really long!

RAVKA

"standard" Ravkan. this is the language spoken in Os Alta, as well as most other places in East Ravka. used on any official documents within Ravka. spoken by most nobility, including those in West Ravka

West Ravkan. this dialect formed only after the creation of the Fold - because the two sides of the country were separated from each other, linguistic drift occurred. over the 400 years that the Fold existed, the two languages diverged from each other significantly, but are still mutually intelligible - they're still very clearly dialects of the same language, not separate languages altogether. most West Ravkan nobility don't use this dialect, although those who are in favour of West Ravka becoming an independent country WILL use this dialect to promote independence. many West Ravkans also speak "standard" Ravkan, because of military service; they would have to communicate with people from across the country - however, many of them would still speak West Ravkan at home, with family, etc. most East Ravkans, especially nobility, wouldn't speak West Ravkan and would probably look down on those who do; I imagine Nikolai speaks at least some because it's the kind of thing he'd do (and the place he's Grand Duke of, Udova, is in West Ravka)

Suli. definitely a completely separate language from Ravkan; they don't have much in common. spoken predominantly by travelling Suli, and very rarely by non-Suli - although in canon, it is taught at the Little Palace, and some Grisha will learn the language. diplomats who often have dealings with Suli communities, and soldiers who serve in areas with high Suli populations, will often learn some (though probably not enough to become fluent) - canon states that it's useful for travelling in the west and northwest of Ravka.

Suli/Ravkan dialect. in areas with high Suli populations (predominantly in the west and northwest), locals may have adopted parts of the Suli language, and vice versa, to create a pidgin language that can be understood by both groups. probably NOT spoken by soldiers/diplomats/etc, who prefer to learn the original Suli language

various other dialects! while the most significant difference is between "standard" and West Ravkan, small towns and communities across the country will speak slightly different versions of the language, just because of how big Ravka is

ancient Ravkan. this is briefly mentioned in canon - I imagine it bears a similar relationship to modern Ravkan as that between Old English and modern English; ie, it's a completely different language! very old books that were printed in ancient Ravkan probably still exist; I imagine it's spoken by some members of the clergy, similar to how the Catholic Church uses Latin in our world. often studied by historians or other scholars. iirc Mal's tattoo is also written in ancient Ravkan, which means that either he or somebody around him must have spoken it fairly well. I would guess that Tamar and Tolya probably speak at least some ancient Ravkan because they grew up in the church

FJERDA

"standard" Fjerdan. again, spoken in Djerholm, by the military and by the government. fun canon facts I found while researching for this: all nouns are both plural and singular (similar to English words like "fish") and the language has three grammatical genders, but they are called wolf class, hare class, and tooth class!

Hedjut. the Hedjut, in canon, are an indigenous group living on Kenst Hjerte, a pair of islands off the coast of Fjerda. though some have come to live on the mainland (I believe Ylva, Jarl Brum's wife, is Hedjut?) most still live on the islands and speak their own language, separate from Fjerdan

liturgical Fjerdan. religion plays a huge part in Fjerdan culture, and imo their holy texts would have been written in this liturgical version of the language, many centuries before canon takes place. drüskelle are probably taught liturgical Fjerdan. some people might also prefer to pray to Djel in liturgical Fjerdan? speakers of modern Fjerdan can probably understand it, but with some effort

again, multiple other dialects. Fjerda has a lot of peninsulas; the language would have developed differently in different places. when Nina is in the Elling peninsula in KoS, she probably has to speak the local dialect rather than the "standard" Fjerdan which she probably learnt in training

other indigenous languages. now, this is purely conjecture, but the grishaverse map shows other small islands off the coast of Fjerda, which don't seem to be part of Kenst Hjerte. it's entirely possible that there's other indigenous groups, like the Hedjut, living there, with their own separate languages. on the other hand, in an age of sea travel, it's likely that Fjerda would have colonised those islands and brought them into the larger country, meaning that the groups living there would be classed as Fjerdans and encouraged to speak Fjerdan

KERCH

"standard" Kerch. this one is so interesting because Kerch is canonically the language used for international trade, so diplomats and politicians across the grishaverse would likely be able to speak Kerch. knowing the language is probably also a sign of status in other countries, including Ravka. it's spoken by most people within Kerch, as well as being the language used for any kind of international relations. for example, I imagine that at the summit at the end of Rule of Wolves, both the Ravkan and Fjerdan delegations spoke Kerch

Barrel Kerch. has a similar relationship to "standard" Kerch as Cockney does to "standard" English - they're recognisably the same language, though spoken with very different accents, but Barrel Kerch has created so much new vocabulary that doesn't exist in "standard" Kerch. I also think that this is why Wylan didn't recognise the word "mark" in Six of Crows - it simply didn't exist in the version of Kerch he's used to speaking!

other dialects. Kerch is much smaller than Ravka or Fjerda, so I imagine there's fewer separate dialects, but people living in the Kerch countryside probably speak a slightly non-"standard" version of Kerch. Kaz probably grew up speaking a country dialect, and had to adjust when he started living in Ketterdam

SHU HAN

official Shu. probably? we know very, very little about the language(s) within Shu Han, but it's a fair bet that there's an official version of the language used by the government etc. this is probably the dialect that's taught to students studying Shu, particularly noble children or diplomats. its main difference from common Shu is that it has a smaller, simpler vocabulary and is easier to communicate effectively in

"common" Shu. in canon, we get a lot of references to words or phrases in Shu that are untranslatable - often in poetry or literature. that would probably be really impractical for a language used in business, so imo the dialect used by most people would be slightly different from the dialect used in government. this dialect has a lot of flowery, poetic language.

other dialects. while Shu Han is smaller than Ravka, it's still pretty big, so I imagine that again, there would be slightly differing variants of the language spoken in different places

THE WANDERING ISLE

there is no standard version of Kaelish. in my personal headcanon, the Wandering Isle is based on a mix of multiple different Celtic cultures and so has multiple different languages. honestly I could make a whole other masterpost based on my headcanons for the Wandering Isle, but I'll stick to the languages for now

Central Kaelish. this is what I imagine Colm and Jesper speak; it's loosely based on Welsh, given that Jesper's middle name is Welsh. it's probably Colm's first language, but he taught Jesper to speak it so he wouldn't lose touch with his Kaelish heritage

North Kaelish. this is what I think Pekka Rollins's dialect is; loosely based on Scottish Gaelic

basically, there's dozens of dialects across the country; some of them overlap somewhat with others, while some are more distinct

NOVYI ZEM

okay SO. once again there's like, zero canon material to work with here, but it's fine. canonically the language spoken is Zemeni. like with most of these countries, there's probably a "standard" version which is used for official purposes, spoken in and around the capital city, Shriftport

Northern Zemeni. the capital city is in the south of the country, so the dialect which differs most from "standard" Zemeni is probably spoken mostly in the north

other dialects. if I had to guess, I'd say that the other big separation of dialects is between coastal areas and inland areas - coastal cities which see a lot of trade would probably use "standard" Zemeni, so they can communicate with people who've learnt Zemeni (who would likely have studied the "standard" dialect), while inland areas would have developed their own dialects

OTHER AREAS

the Southern Colonies: is canonically a colony of Kerch, so their official language is probably "standard" Kerch. it's also canonically a place where criminals from Kerch are exiled (and the former King and Queen of Ravka, but that's almost certainly a rare exception) so there's probably also a lot of Barrel Kerch being spoken, that the criminals have brought over

there's almost certainly at least one indigenous language spoken there as well, though. whatever culture it used to have before being colonised by Kerch probably hasn't been entirely erased. the closest real-world comparison is probably Australia, where English criminals used to be sent? so I do think that there are indigenous groups living there, with their own culture and languages

a dialect has probably formed that mixes parts of Kerch with parts of the indigenous language, forming a new pidgin so that locals and new arrivals can communicate

if the Southern Colonies ever gets independence, I imagine that the original indigenous language would become its official language - the pidgin is probably used more day-to-day, though

it's also possible that the Southern Colonies used to be a part of Novyi Zem before being colonised; in which case, the indigenous people might speak Zemeni? I personally think it's separate, though

the Bone Road: a set of islands, near the Wandering Isle. apparently there are dozens but only two have names - the names they've been given sound vaguely Ravkan. I imagine that those two, Jelka and Vilki, have been "discovered" by Ravkan explorers (though probably not colonised? I think if they were Ravkan territories that would've been mentioned when Nikolai takes Alina to the Bone Road in S&S) and given Ravkan names

however, all of the islands have their own cultures and languages. they're pretty small islands so I don't think that there would be many different dialects within each island. on the other hand, I wouldn't be surprised if the languages spoken on each island were all quite similar to each other, though recognisably distinct. they're probably all at least from the same language family

#holy shit this took ages lmao#but I'm really proud of it!!#if anybody has any questions about any of this DEFINITELY send them my way - I'd love to chat about linguistics/conlangs/etc#I might actually make that Wandering Isle masterpost sometime tbh bc I have soooo many thoughts#mayhem.txt#grishaverse#mayhem grishaverse originals#I really hope I haven't forgotten anything here lmao#shadow and bone#six of crows#king of scars

97 notes

·

View notes

Text

[ID: The first image is of four stuffed artichoke hearts on a plate with a mound of rice and fried vermicelli; the second is a close-up on one artichoke, showing fried ground 'beef' and golden pine nuts. End ID]

أرضي شوكي باللحم / Ardiyy-shawkiyy b-al-lahm (Stuffed artichoke hearts)

Artichoke hearts stuffed with spiced meat make a common dish throughout West Asia and North Africa, with variations on the recipe eaten in Lebanon, Syria, Palestine, Algeria, and Morocco. In Palestine, the dish is usually served on special occasions, either as an appetizer, or as a main course alongside rice. The artichokes are sometimes paired with cored potatoes, which are stuffed and cooked in the same manner. Stuffed artichokes do not appear in Medieval Arab cookbooks (though artichokes do), but the dish's distribution indicates that its origin may be Ottoman-era, as many other maḥshis (stuffed dishes) are.

The creation of this dish is easy enough once the artichoke hearts have been excavated (or, as the case may be, purchased frozen and thawed): they are briefly deep-fried, stuffed with ground meat and perhaps pine nuts, then stewed in water, or water and tomato purée, or stock, until incredibly tender.

While simple, the dish is flavorful and well-rounded. A squeeze of lemon complements the bright, subtle earthiness of the artichoke and cuts through the richness of the meat; the fried pine nuts provide a play of textures, and pick up on the slight nutty taste that artichokes are known for.

Terminology and etymology

Artichokes prepared in this way may be called "ardiyy-shawkiyy b-al-lahm." "Ardiyy-shawkiyy" of course means "artichoke"; "ب" ("b") means "with"; "ال" ("al") is the determiner "the"; and "لَحْم" ("laḥm") is "meat" (via a process of semantic narrowing from Proto-Semitic *laḥm, "food"). Other Palestinian Arabic names for the same dish include "أرضي شوكي محشي" ("ardiyy-shawkiyy maḥshi," "stuffed artichokes"), and "أرضي شوكي على ادامه" ("ardiyy-shawkiyy 'ala adama," "artichokes cooked in their own juice").

The etymology of the Levantine dialectical phrase meaning "artichoke" is interestingly circular. The English "artichoke" is itself ultimately from Arabic "الخُرْشُوف" ("al-khurshūf"); it was borrowed into Spanish (as "alcarchofa") during the Islamic conquest of the Iberian peninsula, and thence into English via the northern Italian "articiocco." The English form was probably influenced by the word "choke" via a process of phono-semantic matching—a type of borrowing wherein native words are found that sound similar to the foreign word ("phonetics"), and communicate qualities associated with the object ("semantics").

"Artichoke" then returned to Levantine Arabic, undergoing another process of phono-semantic matching to become "ardiyy-shawkiyy": أَرْضِيّ ("ʔarḍiyy") "earthly," from أَرْض ("ʔarḍ"), "Earth, land"; and شَوْكِيّ ("shawkiyy") "prickly," from شَوْك ("shawk"), "thorn."

Artichokes in Palestine

Artichoke is considered to be very healthful by Palestinian cooks, and it is recommended to also consume the water it is boiled in (which becomes delightfully savory and earthy, suitable as a broth for soup). In addition to being stuffed, the hearts may be chopped and cooked with meat or potatoes into a rich soup. These soups are enjoyed especially during Ramadan, when hot soup is popular regardless of the season—but the best season for artichokes in the Levant is definitively spring. Stuffed artichokes are thus often served by Jewish people in North Africa and West Asia during Passover.

Artichokes grow wild in Palestine, sometimes in fields adjacent to cultivated crops such as cereals and olives. Swiss traveler Johann Ludwig Burckhardt, writing in 1822, referred to the abundant wild artichoke plants (presumably Cynara syriaca) near لُوبْيا ("lūbyā"), a large village of stone buildings on a hilly landscape just west of طبريا ("ṭabariyya," Tiberias):

About half an hour to the N. E. [of Kefer Sebt (كفر سبط)] is the spring Ain Dhamy (عين ظامي), in a deep valley, from hence a wide plain extends to the foot of Djebel Tor; in crossing it, we saw on our right, about three quarters of an hour from the road, the village Louby (لوبي), and a little further on, the village Shedjare (شجره). The plain was covered with the wild artichoke, called khob (خُب); it bears a thorny violet coloured flower, in the shape of an artichoke, upon a stem five feet in height.

(Despite resistance from local militia and the Arab Liberation Army, Zionist military groups ethnically cleansed Lubya of its nearly 3,000 Palestinian Arab inhabitants in July of 1948, before reducing its buildings and wells to rubble, The Jewish National Fund later planted the Lavi pine forest over the ruins.)

Artichokes are also cultivated and marketed. Elihu Grant, nearly a century after Burckhardt's writing, noted that Palestinian villages with sufficient irrigation "[went] into gardening extensively," and marketed their goods in crop-poor villages or in city markets:

Squash, pumpkin, cabbage, cauliflower, lettuce, turnip, beet, parsnip, bean, pea, chick-pea, onion, garlic, leek, radish, mallow and eggplant are common varieties [of vegetable]. The buds of the artichoke when boiled make a delicious dish. Potatoes are getting to be quite common now. Most of them are still imported, but probably more and more success will be met in raising a native crop.

Either wild artichokes (C. syriaca) or cardoons (C. cardunculus, later domesticated to yield modern commerical artichokes) were being harvested and eaten by Jewish Palestinians in the 1st to the 3rd centuries AD (the Meshnaic Hebrew is "עַכָּבִיּוֹת", sg. "עַכָּבִית", "'aqubit"; related to the Arabic "عَكُوب" "'akūb," which refers to a different plant). The Tosefta Shebiit discusses how farmers should treat the sprouting of artichokes ("קינרסי," "qinrasi") during the shmita year (when fields are allowed to lie fallow), indicating that Jews were also cultivating artichokes at this time.

Though artichokes were persistently associated with wealth and the feast table (perhaps, Susan Weingarten speculates, because of the time they took to prepare), trimming cardoons and artichokes during festivals, when other work was prohibited, was within the reach of common Jewish people. Those in the "upper echelons of Palestinian Jewish society," on the other hand, had access to artichokes year-round, including (through expensive marvels of preservation and transport) when they were out of season.

Jewish life and cuisine

Claudia Roden writes that stuffed artichoke, which she refers to as "Kharshouf Mahshi" (خرشوف محشي), is "famous as one of the grand old Jerusalem dishes" among Palestinian Jews. According to her, the stuffed artichokes used to be dipped in egg and then bread crumbs and deep-fried. This breading and frying is still referenced, though eschewed, in modern Sephardi recipes.

Prior to the beginning of the first Aliyah (עלייה, wave of immigration) in 1881, an estimated 3% of the overall population of Palestine, or 15,011 people, were Jewish. This Jewish presence was not the result of political Zionist settler-colonialism of the kind facilitated by Britain and Zionist organizations; rather, it consisted of ancestrally Palestinian Jewish groups, and of refugees and religious immigrants who had been naturalized over the preceding decades or centuries.

One such Jewish community were the Arabic-speaking Jews whom the Sephardim later came to call "מוּסְתערבים" or "مستعربين" ("Musta'ravim" or "Musta'ribīn"; from the Arabic "مُسْتَعْرِب" "musta'rib," "Arabized"), because they seemed indifferentiable from their Muslim neighbors. A small number of them were descendants of Jews from Galilee, which had had a significant Jewish population in the mid-1st century BC; others were "מגרבים" ("Maghrebim"), or "مغربية" ("Mughariba"): descendents of Jews from Northwest Africa.

Another major Jewish community in pre-mandate Palestine were Ladino-speaking descendents of Sephardi Jews, who had migrated to Palestine in the decades following their expulsion from Spain and then Portugal in the late 15th century. Though initially seen as foreign by the 'indigenous' Mista'avim, this community became dominant in terms of population and political influence, coming to define themselves as Ottoman subjects and as the representatives of Jews in Palestine.

A third, Yiddish- and German-speaking, Askenazi Jewish population also existed in Palestine, the result of immigration over the preceding centuries (including a large wave in 1700).

These various groups of Jewish Palestinians lived as neighbors in urban centers, differentiating themselves from each other partly by the language they spoke and partly by their dress (though Sephardim and Ashkenazim quickly learned Arabic, and many Askenazim and Muslims learned Ladino). Ashkenazi women also learned from Sephardim how to prepare their dishes. These groups' interfamiliarity with each other's cuisine is further evidenced by the fact that Arabic words for Palestinian dishes entered Ladino and Yiddish (e.g. "كُفْتَة" / "kufta," rissole; "مَزَّة" "mazza," appetizer); and words entered Arabic from Ladino (e.g. "דונסי" "donsi," sweet jams and fruit leather; "בוריק" "burek," meat and cheese pastries; "המים" "hamim," from "haminados," braised eggs) and Yiddish (e.g. "לעקעך" "lakach," honey cake).

In addition to these 'native' Jews were another two waves of Ashkenazi migration in the late 18th and early-to-mid 19th centuries (sometimes called the "היישוב הישן," "ha-yishuv ha-yashan," "old settlement," though the term is often used more broadly); and throughout the previous centuries there had also been a steady trickle of religious immigration, including elderly immigrants who wished to die in Jerusalem in order to be present at the appointed place on the day of Resurrection. Recent elderly women immigrants unable to receive help from charitable institutions would rely on the community for support, in exchange helping the young married women of the neighborhood with childcare and with the shaping of pastries ("מיני מאפה").

In the first few centuries AD, the Jewish population of Palestine were largely farmers and agricultural workers in rural areas. By the 16th century, however, most of the Jewish population resided in the Jewish Holy Cities of Jerusalem (القُدس / al-quds), Hebron (الخليل / al-khalil), Safed (صفد), and Tiberias (طبريا / ṭabariyya). In the 19th century, the Jewish population lived entirely in these four cities and in expanding urban centers Jaffa and Haifa, alongside Muslims and Christians. Jerusalem in particular was majority Jewish by 1880.

In the 19th century, Jewish women in Jerusalem, like their Christian and Muslim neighbors, used communal ovens to bake the bread, cakes, matzah, cholent, and challah which they prepared at home. One woman recalls that bread would be sent to the baker on Mondays and Thursdays—but bribes could be offered in exchange for fresh bread on Shabbat. Charges would be by the item, or else a fixed monthly payment.

Trips to the ovens became social events, as women of various ages—while watching the bakers, who might not put a dish in or take it out in time—sent up a "clatter" of talking. During religious feast days, with women busy in the kitchen, some families might send young boys in their stead.

Markets and bakeries in Jerusalem sold bread of different 'grades' based on the proportion of white and wheat flour they contained; as well as flatbread (خبز مفرود / חובז מפרוד / khobbiz mafroud), Moroccan מאווי' / ماوي / meloui, and semolina breads (כומאש / كماج / kmaj) which Maghrebim especially purchased for the Sabbath.

On the Sabbath, those who had brick ovens in their sculleries would keep food, and water for tea and coffee, warm from the day before (since religious law prohibits performing work, including lighting fires, on Shabbat); those who did not would bring their food to the oven of a neighbor who did.

Palestinian Jewish men worked in a variety of professions: they were goldsmiths, writers, doctors, merchants, scientists, linguists, carpenters, and religious scholars. Jewish women, ignoring prohibitions, engaged in business, bringing baked goods and extra dairy to markets in Jerusalem, grinding and selling flour, spinning yarn, and making clothing (usually from materials purchased from Muslims); they were also shopkeepers and sellers of souvenirs and wine. Muslims, Jews, and Christians shared residential courtyards, pastimes, commercial enterprises, and even holidays and other religious practices.

Zionism and Jewish Palestinians

Eastern European Zionists in the 1880s and 90s were ambivalent towards existing Jewish communities in Palestine, often viewing them as overly traditional and religious, backwards-thinking, and lacking initiative. Jewish Palestinians did not seem to conform with the land-based, agricultural, and productivist ideals of political Zionist thinkers; they were integrated into the Palestinian economy (rather than seeking to create their own, segregated one); they were not working to create a Jewish ethnostate in Palestine, and seemed largely uninterested in nationalist concerns. Thus they were identified with Diaspora Jewish culture, which was seen as a remnant of exile and oppression to be eschewed, reformed, or overthrown.

These attitudes were applied especially to Sephardim and Mista'arevim, who were frequently denigrated in early Zionist literature. In 1926, Revisionist Zionist leader Vladimir Jabotinsky wrote that the "Jews, thank God, have nothing in common with the East. We must put an end to any trace of the Oriental spirit in the Jews of Palestine." The governance of Jewish communities was, indeed, changed with the advent of the British Mandate (colonial rule which allowed the British to facilitate political Zionist settling), as European political and "socialist" Zionists promoted Ashkenazi over Sephardi leadership.

Under the Ottomans, the millet system had allowed a degree of Jewish and Christian autonomy in matters of religious study and leadership, cultural and legal affairs, and the minting of currency. The religious authority of all Jewish people in Palestine had been the Sephardi Rabbi of Jerusalem, and his authority on matters of Jewish law (like the authority of the Armenian Patriarchate on matters of Christian law) extended outside of Palestine.

But British and European funding allowed newer waves of Ashkenazi settlers (sometimes called "היישוב החדש," "ha-yishuv ha-khadash," "new settlement")—who, at least if they were to live out the ideals of their sponsors, were more secular and nationalist-minded than the prior waves of Ashkenazi immigration—to be de facto independent of Sephardi governance. Several factors lead to the drying up of halaka (donated funds intended to be used for communal works and the support of the poor in Sephardi communities), which harmed Sephardim economically.

Zionist ideas continued to dominate newly formed committees and programs, and Palestinian and Sephardi Jews reported experiences of racial discrimination, including job discrimination, leading to widespread poverty. The "Hebrew labor" movement, which promoted a boycott of Palestinian labor and produce, in fact marginalized all workers racialized as Arab, and promises of work in Jewish labor unions were divided in favor of Ashkenazim to the detriment of Sephardim and Mizrahim. This economic marginalization coincided with the "social elimination of shared indigenous [Palestinian] life" in the Zionist approach to indigenous Jews and Muslims.

Despite the adversarial, disdainful, and sometimes abusive relationship which the European Zionist movement had with "Oriental" Jews, their presence is frequently used in Zionist food and travel writing to present Israel as a multicultural and pluralist state. Dishes such as stuffed artichokes are claimed as "Israeli"—though they were eaten by Jews in Palestine prior to the existence of the modern state of Israel, and though Sephardi and Mizrahi diets were once the target of a civilizing, correcting mission by Zionist nutritionists. The deep-frying that stuffed artichokes call for brings to mind European Zionists' half-fascinated, half-disgusted attitudes towards falafel. The point is not to claim a dish for any one national or ethnic group—which is, more often than not, an exercise in futility and even absurdity—but to pay attention to how the rhetoric of food writing can obscure political realities and promote the colonizer's version of history. The sinking of Jewish Palestinian life prior to the advent of modern political Zionism, and the corresponding insistence that it was Israel that brought "Jewish cuisine" to Palestine, allow for such false dichotomies as "Jewish-Palestinian relations" or "Jewish-Arab relations"; these descriptors further Zionist rhetoric by making a clear situation of ethnic cleansing and settler-colonialism sound like a complex and delicate issue of inter-ethnic conflict. To boot, the presentation of these communities as having merely paved the way to Zionist nationalism ignores their existence as groups with their own political, social, and cultural lives and histories.

Help evacuate a Gazan family with Operation Olive Branch

Buy an eSim for use in Gaza

Help Anera provide food in Gaza

Ingredients:

Serves 4 (as a main dish).

For the artichokes:

6 fresh, very large artichokes; or frozen (not canned) whole artichoke hearts

1 lemon, quartered (if using fresh artichokes)

250g (1 1/2 cups) vegetarian ground beef substitute; or 3/4 cup TVP hydrated with 3/4 cup vegetarian 'beef' stock from concentrate

1 yellow onion, minced

Scant 1/2 tsp kosher salt

1/2 tsp ground black pepper

1 pinch ground cardamom (optional)

1/4 tsp ground allspice or seb'a baharat (optional)

1 Tbsp pine nuts (optional)

Water, to simmer

Oil, to fry

2 tsp vegetarian 'beef' stock concentrate, to simmer (optional)

Lemon, to serve

Larger artichokes are best, to yield hearts 3-4 inches in width once all leaves are removed. If you only have access to smaller artichokes, you may need to use 10-12 to use up all the filling; you might also consider leaving some of the edible internal leaves on.

The meat may be spiced to taste. Sometimes only salt and black pepper are used; some Palestinian cooks prefer to include seb'a baharat, white pepper, allspice, nutmeg, cardamom, and/or cinnamon.

Medieval Arab cookbooks sometimes call for vegetables to be deep-fried in olive oil (see Fiḍālat al-Khiwān fī Ṭayyibāt al-Ṭaʿām wa-l-Alwān, chapter 6, recipe no. 373, which instructs the reader to treat artichoke hearts this way). You may use olive oil, or a neutral oil such as canola or sunflower (as is more commonly done in Palestine today).

Elihu Grant noted in 1921 that lemon juice was often served with stuffed vegetable dishes; today stuffed artichokes are sometimes served with lemon.

For the rice:

200g Egyptian rice (or substitute any medium-grained white rice)

2 tsp broken semolina vermicelli (شعيريه) (optional)

1 tsp olive oil (optional)

Large pinch salt

520g water, or as needed

Broken semolina vermicelli (not rice vermicelli!) can be found in plastic bags at halal grocery stores.

Instructions:

For the stuffed artichokes:

1. Prepare the artichoke hearts. Cut off about 2/3 of the top of the artichoke (I find that leaving at least some of the stem on for now makes it easier to hollow out the base of the artichoke heart without puncturing it).

2. Pull or cut away the tough outer bracts ("leaves") of the artichoke until you get to the tender inner leaves, which will appear light yellow all the way through. As you work, rub a lemon quarter over the sides of the artichoke to prevent browning.

3. If you see a sharp indentation an inch or so above the base of the artichoke, use kitchen shears or a sharp knife to trim off the leaves above it and form the desired bowl shape. Set aside trimmings for a soup or stew.

4. Use a small spoon to remove the purple leaves and fibers from the center of the artichoke. Make sure to scrape the spoon all along the bottom and sides of the artichoke and get all of the fibrous material out.

5. Use a paring knife to remove any remaining tough bases of removed bracts and smooth out the base of the artichoke heart. Cut off the entire stem, so that the heart can sit flat, like a bowl.

6. Place the prepared artichoke heart in a large bowl of water with some lemon juice squeezed into it. Repeat with each artichoke.

7. Drain artichoke hearts and pat dry. Heat a few inches of oil in a pot or wok on medium and fry artichoke hearts, turning over occasionally, for a couple minutes until lightly browned. If you don't want to deep-fry, you can pan-fry in 1 cm or so of oil, flipping once. Remove with a slotted spoon and drain.

8. Prepare the filling. Heat 1 tsp of olive oil in a large skillet on medium-high and fry onions, agitating often, until translucent.

Tip: Some people add the pine nuts and brown them at this point, to save a step later. If you do this, they will of course be mixed throughout the filling rather than being a garnish on top.

9. Add spices, salt, and meat substitute and fry, stirring occasionally, until meat is browned. (If using TVP, brown it by allowing it to sit in a single layer undisturbed for 3-4 minutes, then stir and repeat.) Taste and adjust spices and salt.

10. Heat 1 Tbsp of olive oil or margarine in a small pan on medium-low. Add pine nuts and fry, stirring constantly, until they are a light golden brown, then remove with a slotted spoon. Note that, once they start taking on color, they will brown very quickly and must be carefully watched. They will continue to darken after they are removed from the oil, so remove them when they are a shade lighter than desired.

11. Stuff the artichoke hearts. Fill the bowl of each heart with meat filling, pressing into the bottom and sides to fill completely. Top with fried pine nuts.

12. Cook the artichoke hearts. Place the stuffed artichoke hearts in a single layer at the bottom of a large stock pot, along with any extra filling (or save extra filling to stuff peppers, eggplant, zucchini, or grape leaves).

13. Whisk stock concentrate into several cups of just-boiled water, if using—if not, whisk in about a half teaspoon of salt. Pour hot salted water or stock into the pot to cover just the bottoms of the stuffed artichokes.

14. Simmer, covered, for 15-20 minutes, until the artichokes are tender. Simmer uncovered for another 5-10 minutes to thicken the sauce.

For the rice:

1. Rinse your rice once by placing it in a sieve, putting the sieve in a closely fitting bowl, then filling the bowl with water; rub the rice between your fingers to wash, and remove the sieve from the bowl to strain.

2. Place a bowl on a kitchen scale and tare. Add the rice, then add water until the total weight is 520g. (This will account for the amount of water stuck to the rice from rinsing.)

3. (Optional.) In a small pot with a close-fitting lid, heat 1 tsp olive oil. Add broken vermicelli and fry, agitating often, until golden brown.

4. Add the rice and water to the pot and stir. Increase heat to high and allow water to come to a boil. Cover the pot and lower heat to a simmer. Cook the rice for 15 minutes. Remove from heat and steam for 10 minutes.

To serve:

1. Plate artichoke hearts on a serving plate alongside rice and lemon wedges; or, place artichoke hearts in a shallow serving dish, pour some of their cooking water in the base of the dish, and serve rice on a separate plate.

Tip: The white flesh at the base of the bracts (or "leaves") that you removed from the artichokes for this recipe is also edible. Try simmering removed leaves in water, salt, and a squeeze of lemon for 15 minutes, then scraping the bract between your teeth to eat the flesh.

199 notes

·

View notes

Text

And I am following from here with part 2 lol

Also, I am standing with the first cousin thrice removed, this drama is something my family has in common and definitely I have first cousins thrice removed (and I envy a tiny bit functional families).

Anyway. Also, I know, but also I am having fun, so pls? forgive any incongruences.

Normal: Westron

Typed: Legolas and his sylvan dialect

Italic: Sindarin

Bold: Khuzdul

Bold in red: Ancient Khuzdul

Cursive: Quenya

When Galadriel received a first message indicating that the Fellowship was at the borders of Lothlorien, she sighed with relief.

But when a second message arrived carrying news of what appeared to be a very tall Elf with red hair, she had to make sure that she heard loud and clear.

It couldn't be.

She exchanged a pregnant look with her husband Celeborn, who sighed in frustration and closed his eyes - they probably were considering whether helping with the secret errand was worth having a war criminal - and cousin thrice removed - walk through their realm.

Galadriel in particular was telling herself that DEFINITELY it was ANOTHER Elf with red hair.

And they decided to take the risk, if anything the entirety of the Elvish army would outnumber him, if things went downhill.

Maybe.

---

The fellowship entered Lothlorien carefully, before being spotted by Haldir and the other guards - all of them young compared to the ancient Elf, he wondered if they knew well about what he did back then and if that changed things for the rest of the company. Maedhros looked really uncomfortable, if he remembered Galadriel well he was very sure he'd be killed on the spot.

Such thing did not happen, however.

Aragorn, who seemed to have taken the mantle of leader of their group, seemed to be negotiating some sort of passage on behalf of the Dwarf - something strange to him.

As far as he remembered Dwarves and Elves were getting along well enough.

He would have to ask - there was not a chance that the halflings would know, and Aragorn and Legolas were busy discussing with Haldir. He sighed softly.

"Uh... Gimli son of Gloin, right? Why are Elves not getting along with Dwarves?"

Yeah, he truly needed to brush up his Khuzdul. He was however pleasantly surprised when the Dwarf responded back in the same language.

"Tis right, lad. We hold a lot of grudges here. Also, why do you know Khuzdul, albeit ancient?"

"I see that it has not changed a lot. I used to be a really good friend with Dwarves. One of my brothers more than me, he was a smith."

"You both sound quite the sensible people, for being Elves. As for the ancient Khuzdul, we learn it, but it is not commonly spoken."

The two stayed in silence for a while, mulling over the conversation. The discussion with Haldir, on the other hand, was getting heated. Gimli grumbled, crossing his arms. "Wish I could understand what they are talking about."

Maedhros made a half smile. "It seems that the negotiations around passage means that you, Master Dwarf, shall pass blindfolded and tied. And I might follow, as the unwelcome guest that I am."

And that made Gimli nearly blow up the negotiations. Legolas looked at Aragorn in frustration, whilst Aragorn looked at everyone and was not impressed by the behaviours shown.

"Well then, everyone will proceed blindfolded and tied." Aragorn announced. Legolas was less than thrilled.

"I am their kin! I refuse to go blindfolded and tied through this ordeal!" Gimli scoffed. "Seems like I am the only one thinking that this is fair!"

An argument was about to start and at that point Maedhros went to Haldir. "I will go blindfolded and tied, if this is the condition. Elr- no, Aragorn clearly knows what he is doing and time is pressing."