#third-person global subjective point-of-view

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

What to Watch at the End

I've been happy to run in to a couple pieces of media back-to-back over the last week or so- plenty of down time, since I have that bug that's going around. They make pretty interesting companion pieces to one another, actually. With the end of the world so close now, we're starting to get a bit more genuinely thoughtful art about the subject, stuff you really can't say until you have this kind of vantage point.

They are The Power Fantasy (written by Kieron Gillen), an early-days ongoing comic of the 'deconstructing superheroes' type, and Pantheon (created by Craig Silverstein), one of those direct-to-streaming shows that get no marketing and inevitably fade away quickly; this one's an adult cartoon with two eight-episode seasons, adapted from some Ken Liu short stories, with a complete and satisfying ending. I'll put in a cut from here; targeted spoilers won't occur, but I'll be talking about theme and subject matter as well as a few specific plot beats, so you won't be entirely fresh if you read on.

Pantheon is a solid, if wobbly, stab at singularity fiction, with more of a focus on uploaded intelligence than purely synthetic (though both come in to play). It's about two-thirds YA to start, declining to about one-fifth by the end. The Power Fantasy, by contrast, is an examination of superpowers through a geopolitical lens that compares them to nuclear states; I'm not as good a judge of comics over all (particularly unfinished comics), but this one seems very high quality to me.

The intersection of the Venn Diagram of these two shows is the problem of power, and in particular the challenges of a human race handing off the baton to the entities that supersede it. They're both willing to radically change the world in response to the emergence of new forces; none of them even try to 'add up to normal' or preserve the global status quo. Both reckon with megadeath events.

I'm a... fairly specific mix of values and ethical stances, so I'm well used to seeing (and enjoying!) art and media that advance moral conclusions I don't agree with on a deep level. I used to joke that Big Hero Six was the only big-budget movie of its decade that actually captured some of my real values without compromise. (I don't think it's quite that bad, actually, I was being dramatic, but it's pretty close.)

Pantheon was a really interesting watch before I figured out what it was doing, because it felt like it was constantly dancing on the edge of either being one of those rare stories, or of utterly countermanding it with annoying pablum. It wasn't really until the second or third episode that I figured out why- it's a Socratic dialogue, a narrative producing a kind of dialectical Singularity.

The show maintains a complex array of philosophies and points of view, and makes sure that all of them get about as fair a shake as it can. This means, if you're me, then certain characters are going to confidently assert some really annoying pro-death claims and even conspire to kill uploaded loved ones for transparently bad reasons. If you're not me, you'll find someone just as annoying from another direction, I'm sure of it. Everybody has an ally in this show, and everybody has an enemy, and every point of view both causes and solves critical problems for the world.

For example, the thing simply does not decide whether an uploaded person is 'the same as' the original or a copy without the original essence; when one man is uploaded, his daughter continues thinking of him as her dad, and his wife declares herself widowed, and both choices are given gravitas and dignity. He, himself, isn't sure.

This isn't something you see in fiction hardly at all- the last time I can think of was Terra Ignota, though this show lacks that story's gem-cut perfection. It's that beautiful kind of art where almost nobody is evil, and almost everything is broken. And something a little bit magical happens when you do this, even imperfectly, because the resulting narrative doesn't live in any single one of their moral universes; it emerges from all of them, complexly and much weirder than a single simplistic point of view would have it. And they have to commit to the bit, because the importance of dialogue is the core, actual theme and moral center of this show.

The part of rationalism I've always been least comfortable with has been its monomania, the desire to sculpt one perfect system and then subject all of reality to it. This becomes doomerism very quickly; in short order, rationalists notice 'out of the crooked timber of humanity, no straight thing was ever made', and then conclude that we're all very definitely going to die, once the singleton infinite-power system takes over, because it too will be flawed. (e.g. this joking-not-joking post by Big Yud.)

And don't get me wrong, I do take that concern seriously. I don't think I can conclusively, definitely convince myself that rationalism is wrong on this point, not to a degree of confidence that lets me ignore that risk. I don't at all begrudge the people devoting their entire professional lives to avoiding that outcome, even though I don't take it as given or even as particularly likely myself.

But it is precisely that monomania that is the central villain of this show, if it even has one. Breakdowns in dialogue, the assertion of unilateral control, conquering the world for its own good. The future, this show says, is multipolar, and we get there together or not at all.

That's a tremendously beautiful message, and a tremendously important one. I do wish it was more convincing.

The Power Fantasy works, quite hard, to build believably compassionate personalities into the fabric of its narrative. It doesn't take easy ways out, it doesn't give destroy-the-world levels of power to madmen or fools. Much like Pantheon, it gives voice to multiple, considered, and profoundly beautiful philosophies of life. Its protagonists have (sometimes quite serious) flaws, but only in the sense that some of the best among us have flaws; one of them is, more or less literally, an angel.

And that's why the slow, grinding story of slow, grinding doom is so effective and so powerful.

In a way that Pantheon does not, TPF reckons with the actual, specific analysis of escalation towards total destruction. Instead of elevating dialogue to the level of the sacred, it explores the actual limits and tendencies of that dialogue. It shows, again and again, how those good-faith negotiations are simply and tragically not quite good enough, with every new development dragging the world just an inch closer to the brink, making peace just a little bit more impossible. Those compassionate, wise superpowers are trapped in a nightmare that's slowly constricting around them, and they're compassionate and wise enough to know exactly what that means while remaining entirely unable to stop it.

It's most directly and obviously telling a story about the cold war, of course, not about artificial intelligence per se. The 'atomics' of TPF are just X-Men with the serial numbers filed off, and are therefore not constructed artifacts the way that uploaded and synthetic minds are; there's some nod to an 'superpowers arms race' in the AI sense of the term, but it's not a core theme. But these are still 'more than human' in important ways, with several of the characters qualifying directly as superintelligences in one way or another.

The story isn't complete (just getting started, really), so I don't want to speak too authoritatively about its theme or conclusions. But it's safe to say that the moral universe it lives in isn't a comfortable one. Echoing rationalists, the comic opens with an arresting line of dialogue: "The ethical thing to do, of course, would be to conquer the world."

In his excellent book Superintelligence, Nick Bostrom discusses multipolarity somewhat, and takes a rather dim view of it. He sees no hope for good outcomes that way, and argues that it will likely be extremely unstable. In other words, it has the ability to cloud the math, for a little while but it's ultimately just a transitional phase before we reach some kind of universal subordination to a single system.

The Power Fantasy describes such a situation, where six well-intentioned individuals are trying to share the world with one another, and shows beat-by-beat how they fail.

Pantheon cheats outrageously to make its optimism work- close relationships between just the right people, shackles on the superintelligences in just the right degree, lucky breaks at just the right time. It also has, I think, a rather more vague understanding of the principles at play (though it's delightfully faithful to the nerd culture in other ways; there's constant nods to Lain and Ghost in the Shell, including some genuinely funny sight gags, and I'm pretty sure one of the hacker characters is literally using the same brand of mouse as me).

TPF doesn't always show its work, lots of the story is told in fragments through flashbacks and nonlinear fragments. But what it shows, it shows precisely and without compromise or vagueness. It does what it can to stake you to the wall with iron spikes, no wiggle room, no flexibility.

But all the same, there's an odd problem, right? We survived the Cold War.

TPF would argue (I suspect) that we survived because the system collapsed to a singleton- the United States emerged as the sole superpower, with the Pax Americana reigning over the world undisputed for much of the last forty years. There were only two rivals, not six, and when one went, the game functionally ended.

In other words, to have a future, we need a Sovereign.

So let me go further back- the conspicuous tendency of biospheres to involve complex ecosystems with no 'dominant' organism. Sure, certain adaptations radiate quickly outward; sometimes killing and displacing much of what came before. But nature simply gives us no prior record of successful singletons emerging from competitive and dynamic environments, ever. Not even humans, not even if you count our collective species as one individual; we're making progress, but Malaria and other such diseases still prey on us, outside our control for now.

TPF would argue, I suspect, that there's a degree of power at which this stops being true- the power to annihilate the world outright, which has not yet been achieved but will be soon.

But that, I think, has not yet been shown to my satisfaction.

Obligate singleton outcomes are a far, far more novel claim than their proponents traditionally accept, and I think the burden of proof must be much higher than simply having a good argument for why it ought to be true. A model isn't enough; models are useful, not true. I'm hungry for evidence, and fictional evidence doesn't count.

It's an interesting problem, even with the consequences looming so profoundly across our collective horizon right now. TPF feels correct-as-in-precise, the way that economists and game theorists are precise. But economics and game theory are not inductive sciences; they are models, theories, arguments, deductions. They're not observations, and not to be trusted as empirical observations are trusted. Pantheon asserts again and again the power of dialogue and communication, trusts the multipolar world. And that's where my moral and analytical instincts lie too, at least to some degree. I concern myself with deep time, and deep time is endlessly, beautifully plural. But Pantheon doesn't have the rigor to back that up- this is hope, not deduction, and quite reckless in its way. Trying to implement dialectical approaches in anything like a formal system has led to colossal tragedy, again and again.

One narrative is ruthlessly rigorous and logically potent, but persistently unable to account for the real world as I've seen it. The other is vague, imprecise, overconfident, and utterly beautiful, and feels in a deep way like a continuation of the reality that I find all around me- but only feels. Both are challenging, in their way.

It's a bit scary, to be this uncertain about something this consequential. This is a question around which so much pivots- the answer to the Drake paradox, the nature of the world-to-come, the permanence of death. But I simply don't know.

#All told I think this is a pretty good post for somebody with a 102 degree fever#but I do apologize if there's any glaring evidence that I had a 102 degree fever while I was writing it#might have to go back and addendum it some later#if any such emerges

42 notes

·

View notes

Text

some new project 2025 pages, some new analysis

the third "promise" focuses on "sovereignty, borders, and global threats"

"ordered liberty" is SUCH an interesting choice of wording as a national ideal! who exactly gets to "order" this liberty! i have about 40 guess for you.

the woke left does not trust "the american people" and "disdains the Constitution's restrictions on their ambitions"! what are these restrictions, exactly? you haven't argued for why exactly you think the "administrative state" is unconstitutional? is it perhaps because you don't have evidence, you just have buzz words?

never seen such anti-intellectualism in my life.

however... there are some points being made towards legitimate, justified anger that was not at all addressed by the democrats going into this election. the line "contemptuously call fly-over country" is. just an accurate description of how a lot of people on The Side of the Aisle I Belong To view me and mine.

they really hate being part of international clubs and being beholden to other nations. at all. like oh no nato treaties that didn't go through congress! un treaties that didn't go through congress! yeah. we kind of. share the planet. american isolationism is back in!

.... are they really alluding to fucking waco as the pillar of american ideals? WACO?!?!

"intellectual sophistication, advanced degrees" have "no bearing" on a person's knowledge of how to live well. well actually people who know things about subjects tend to know How To Make Those Things Happen. that kind of. comes with the territory.

apparently they hate woodrow wilson specifically with a passion. that's new info to me.

..... open borders are not an example of "cheap grace". i don't think that anti-nazi lutheran theologian dietrich bonhoeffer would agree with you that Actually Some People Broke The "Right" Law that Makes Them Subhuman.

environmentalism is "not a political cause but a pseudo-religion meant to baptize liberals' ruthless pursuit of absolutely power in the holy water of environmental virtue". huh. have you ever heard of a little concept called... projection? like it is not WRONG that some people take environmentalism to religious extremes and that ecofascism exists, but that doesn't make The Very Concept of Not Killing the Planet something you should get rid of to own the libs. again, nuances that aren't being addressed properly on the left because we're so holier than thou and eat each other with infighting

there is a point to be made about the way that the american business industry has shifted most production overseas has hurt this country, but the idea that this must make Everyone Else Everywhere Else the super scary bad guy is absurd.

"the corporations profiting failed to to export our values of human rights and freedom" i don't trust your view of those concepts "rather they imported China's anti-american values" again, don't trust your view of "anti-american" document that views me personally as a sex offender for being kind to trans children at work.

wall street "outright cheered the elimination of america's manufacturing jobs (learn to code!)" this cheerful If You Were Only As Cool and Smart As Me You Would Be Fine IS an issue, and it is one that hasn't been addressed or rectified. however.... the way that people are allowing the President Utilizing This Document, who put elon "worst offender on earth" musk in power proves that they don't care!

"illegal immigration should be ended; not mitigated." well that's fucking terrifying. "the border sealed, not reprioritized" again: terrifying.

.... how the hell do they expect america to "control the global energy market". this is at least partially about greenland oh my fucking gOD

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Magicians in The Raven (1963)

Have you ever listened to the Sword Breaker podcast? You should, but more on that later.

Recently…

Spencer of the Keep Off The Borderlands podcast hosted a Movie Monday call in episode.

The idea behind these episodes is that once a month the podcast host picks a movie and all the listeners watch it. Then they call in to the show to share their thoughts. Since this is primarily a gaming podcast there’s an optional topic of how elements of the movie can inform our gaming.

Spencer is, I believe, the third person to take up the mantle of Movie Monday. With the previous host being Jason of Nerd’s RPG Variety Cast.

This month’s movie was Roger Corman’s The Raven from 1963.

I adore this film. It’s fun and full of petty wizards…also has nothing to do with the Poe poem, but that’s okay.

The Renaissance Wizard

One of the things that strikes me about the film is that it’s set in 1506, which is in the renaissance rather than the middle ages as I would have expected for the subject matter.

This allows the movie to do two very interesting things:

We get all the trappings of the middle ages fantasy, like castles and magic

Magic gets to be viewed as a science, or more specifically, a leisurely academic pursuit

To further drive the point home that wizards are rich academics, each magic-user in the film has a doctorate.

Boris Karloff plays a dastardly sorcerer opposite Vincent Price’s kindly magician. They’re both excellent in the film and their motivations are perfectly mundane.

Price just wants to “practice his magic quietly at home”. Whereas Karloff, the head of a brotherhood of magicians, is envious of Price’s magical powers. He doesn’t want anyone to be a threat to his position in the brotherhood and seeks to coerce Price’s knowledge.

There’s no global conquest or ancient prophecy. The Brotherhood of Magicians and Sorcerers seems to be little more than a social club. Peter Lorre’s character (also a treat in the film) even mentions how wizards meet each other at conventions. It all conjures up images of an academic society or elks lodge.

So Karloff’s character is willing to do horrible things so he can…stay president of a social club? So he can get speaking invitations to conferences and have his academic papers peer reviewed. Probably good money in being the keynote speaker at the college of alchemy’s commencement.

This is peak petty wizard comedy to me. Very reminiscent of Jack Vance’s Dying Earth, specifically Rhialto the Marvellous.

Never Let Writing Go To Waste

Now I love silly wizard stuff, particularly organizations. The absurdist bureaucracy really tickles me.

This brings us back to Sword Breaker. In this all-killer no-filler podcast Logan generates lists around a single topic per episode. It’s all incredibly usable stuff. Wonder if he’s ever published it somewhere…

Anyway, for the gaming aspect of my Movie Monday call, I decided to create a table of magical societies in keeping with the mood of the film. Here they are, for your amusement:

d6 magical societies

1 - The Hermetic Order of Psychonautics

A loose knit collective of high level magic-users seeking to transcend the physical world. Meetings take place in total silence on underground lakes which are used like a giant sensory deprivation tank. Magicians then project their spirits and “sail” on metaphysical yachts in the astral sea, where they discuss enlightenment and free-form jazz. Members often dress in bright colors and carry tuning forks.

2 - The Grand Priory of Illuminates

Chaos magicians who seek to undo their alignment’s negative public perception. Specializing in happy accidents, this group uses subtle magic to alter the course of events in positive but unexpected ways. To become part of the organization, applicants must successfully add to an ever more complex Rube Goldberg machine.

3 - The Society of Reformed Diabolists

Demon worshippers, dread necromancers, and blood magicians trying to turn over a new leaf banded together to form this support group. Members meet regularly to share their experiences with foul sorcery and celebrate monthly or yearly mine stones of being evil-magic free. They also speak at local magic colleges about the dangers of dark rituals.

4 - The Brotherhood of Neptune

These far-seeing astrologers wear blue robes, are excellent swimmers, and perform divination through use of tide pools. They revere the number 8 and as such must spend 8 days a year in meditation, meet every 8 months in groups of no more or less than 8, and establish headquarters 8 blocks from any coastal city center.

5 - The Ancient Order of Pseudepigraphas (soo-di-pig-ra-fa’s)

If you’ve ever wondered how magical knowledge stays so hidden and confusing, it’s probably because of this secret society. Its members spend their time placing errors into magical texts, thwarting efforts to translate or catalog arcane information, and misattributing manuscripts. The extreme secrecy of this sect prevents meetings but they still communicate through scribbles in returned library books.

6 - The Unseen Eye

The least secret secret order you’ll ever see. These occultists are typically high society ladder climbers who seek to manipulate global events from the shadows. However, their attempts at subterfuge are undone by their need to be recognized. Meeting fliers are often posted everywhere and initiates are sent home with all manner of branded merchandise, including wristbands, tea cozies, and hats.

#osr#rpg#indie ttrpg#roger corman#vincent price#boris karloff#peter lorre#film#magic#fantasy#renaissance

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

That's fair. The political line has to be developed through struggle, and you can mess it up if you have no process. But based on what I've seen there are a lot of people who talk a radical game, but when you push them on things, you see that on some level they don't care about winning.

I suppose I'm talking about the more serious and committed forms of error, not the kind of thing that can be fixed with a tweek to practice. The people whose communist identity is built on a sense of tribal loyalty to a specific org, or staking out a radical brand while only prioritizing their own career, over and above the desire to see the war won. I know people who think communists should be seeking connections with established non-profits and union leadership above all, because the point for them is just to be Influential™️. There's a lot of people out there who've given up, even if they won't admit it to themselves.

When a group like the CR-CPUSA/Red Guards shat on everyday people for rejecting their out of touch commandism, to continue on that path in the face of countervailing evidence from the people requires that, on some level in your mind, you're placing victory on a lower level. You get in because you care about the struggle, and you stay in because you end up caring more about the org, or getting your career in politics, or whatever path it is you've chosen in the face of failure.

People can be short sighted, and stumble into opportunism and tailism, but those people are easy to correct and I don't view them as the primary problem. Getting them out of error is just a matter of political education, experience, and mentorship. It's the people who dig their heels in when you try to pull them back that I view as a threat. The kind of people who gave up on communism in the 90s and 00s but still cling to leadership positions in parties across the planet.

The dogmatic ultra-leftists may imagine themselves to be the opposite, but I still see the most egregious prioritizing themselves or their orgs over the victory of communism in some way, while calling it communism. And some have admitted to me that they view revolution as so far out it's irrelevant, or they think it's impossible because of the inherently reactionary nature of the people. Third-Worldism becomes their ideological cover for giving up while holding on to their self-identification as a radical.

People can say they intend whatever, but at a certain point you have to analyze their priorities by what they do and what they push for. This is the subjective condition of humanity, that our consciousness imposes a faulty unity on the contradictions within our own brain. If you believe in victory and prioritize it, then you'll have a motivation to check and correct yourself. If you stop believing, the sides that care about clout or personal advancement can take over, even if you're still saying all the things you learned to believe.

To reverse it: I'd argue a key part of correcting a comrade's tendency for opportunism or dogmatism, is to remotivate and refocus them on the primacy of winning actual victories, here and now, for global communism.

Not sure now how I would phrase it to communicate that.

Both opportunism and dogmatism arrise from a common source: nihilistic subculturalism. Once you give up on the possibility of victory, revolutionary politics can only be driven by personal goals--professional advancement, or clique membership. It no longer matters if you fail to attack capitalism or the people reject you. Political struggle becomes ritualized.

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

Book Review: Michelle Sagara's The Emperor's Wolves

Book Review: Michelle Sagara’s The Emperor’s Wolves

First in The Wolves of Elantra fantasy series (and 0.1 in The Chronicles of Elantra series) revolving around Severn Handred, the Wolf first assigned to work with Kaylin Neya in Cast in Shadow, 1. My Take Sagara has, er, had been making me wonder about Severn and how he ended up with the Wolves. Now, at last, we get to find out. I love that we learn more about Kaylin’s background from Severn’s…

View On WordPress

#author Michelle Sagara#book review#cold case#dragons#executioners#fantasymagic#law enforcement#serial killer#survival#telepaths#The Chronicles of Elantra series#The Wolves of Elantra series#third-person global subjective point-of-view

1 note

·

View note

Text

ℙ𝕤𝕪𝕣𝕖𝕟 ℝ𝕖𝕧𝕚𝕖𝕨

Originally, this was just going to be my quick thoughts after reading the manga, but as I wrote this, I realized I have more to say than I intitially thought. Reading the manga before reading this is recommended, not only because of plot spoilers but because of the plot details I may leave out. I’m mentioning only what I think is relevant to the point I’m making, so if something sounds amiss to you, a non-Psyren reader, then the manga itself probably has what you’re missing.

This is the second review I’ve done, and it also happens to be on a Shonen manga that was mildly popular enough to get an official English translation but never popped off in the west, or in the case of Psyren, sadly never got an anime. I hope to do more of these in the future, since I imagine there’s not a lot of thematic analysis on these types of manga. The average person seems to assume there’s nothing of worth to get out of these childrens’ manga, and only series with big enough followings like Naruto or One Piece seem to get the analysis they deserve. Hopefully, I can right this wrong just a little bit with my reviews.

Psyren is about the nature of humanity. Very original, I know. It’s not the greatest manga ever made, but I’m a firm believer that every piece of media like this has something of worth to say and I would like to hear it out.

Ageha Yoshina is a troubled high schooler. It doesn’t really show in how he acts, though. At least, not at first. Before he time travels into the future and obtains psychic powers, he’s introduced gleefully beating up some school bullies after being paid by a girl from his class. Whether he’s doing it out of the goodness of his heart, to make money, or simply to let out some anger, is left ambiguous. With the context of the entire series, however, what he did it for doesn’t matter. In my opinion, the reason he did this was a combination of all three. Ageha is shown to be unnaturally kind and helpful to people that he has sympathy for throughout the course of the manga. He is also known for being self-interested, not so much to be considered a bad guy, but enough to be considered a teenager making his way through an unsatisfying life. Lastly, and most importantly, Ageha is a bit destructive. This will be fleshed out much more later on, but Ageha himself seems intrinsically tied to destruction.

To imply that destruction is inherently negative, however, is deductive. Drastic measures for the sake of your own justice are common place amongst the heroes and villains of this series. Ageha, who gets himself into the action of the story through his desire to help a sad girl, ends up finding himself unable to feel sympathy for a member of the villain organization that he ends up nearly killing. This character is not written in a sympathetic manner, but this will come up later with Ageha’s refusal to see our main antagonist’s point of view. Other characters in the final arc, who are previously shown to go out of their way to spare villains, swiftly go for the kill during the final arc when the stakes are high.

In chapter 1, Ageha is shown to be deep in thought regarding the current state of the world. Needless wars, global warming... He can’t imagine a future in which these issues are solved. However, he resolves to himself to keep living in the present and not let the future worry him. This is a good and healthy mindset more often than not, but as we see from how Ageha’s future fighting friends feel about it, and how Ageha himself comes to resonate with their feelings, lying back and accepting your fate isn’t good enough. The series makes it very clear that humanity is corrupt, but this is a hopeful story about doing everything you can to fight against the “fate” you’re given.

Before we can continue talking about Ageha, we must discuss our main antagonist.

Miroku Amagi was the third subject of the Grigori project, a project funded by the government which implanted children with psychic powers and subjected them to physical and emotional torment for the sake of gaining their powers. Miroku and his sister, Number 7, were both very kind, sweet children. They were sent to the project by their parents for a large sum of money. Number 7 quickly learned to shut off her emotions to prevent as much mental damage as possible, but Miroku remained cheerful, and hopeful that he would be able to meet his family again soon, which he was lied to about. His parents had abandoned him, they had no means of contacting them. Eventually, as Miroku grew, he became jaded, and the kindness had left his eyes. A sympathetic scientist allowed him a moment of rest away from his psi-reducing technology for his birthday, which gave him the chance to burn the facility to the ground with his psychic powers, leaving only the sympathetic scientist alive, albeit leaving him under strict surveillance to assure he wouldn’t become a detriment to Miroku’s plans. Miroku offered his sister a spot in the new world he would soon create, a world where people with special gifts wouldn’t be subjugated and tortured for their gifts, but she denied, unable to see the man that was once her brother doing such a thing. Number 7 would then go on to create the Psyren game, which lead Ageha and the protagonists into the future world, so that they may find out more about the future and inevitably stop Miroku’s schemes.

Miroku’s ability to steal the souls of others is likely symbolic of his innate hatred of humanity, not merely their actions but the way that humans are able to shamelessly embody hypocritical traits, such as kindness and destruction, without acknowledging that the things they hate about psionists are present within themselves. While labeling Psionists as monsters without a heart, they themselves created them out of pure greed. The heroes, also Psionists, refuse to accept Miroku’s drastic measures, yet they themselves will kill for what they believe, from Miroku’s perspective being the same thing as he is doing. Such hypocrisy doesn’t compute with him, and so must be destroyed. By using their souls to power himself and leaving them an empty husk, he strips them of such contradictions and leaves them the same as him; empty.

In contrast, Miroku Amagi himself may very well be void of contradictions, at least on the surface. The mask he wears to others is that of a God, beckoning destruction and creation for a new future. Unbeknownst to him, however, he is not completely void of the feelings which he observes in humans. He longs to fix this corrupt world just like Ageha, but their methods and points of view are very different. To be described later, he is also a person that wants love.

“I am the sky around which destiny revolves.”

This quote was in my head for the majority of the climax. It took me a bit to realize what the core message of this manga was, or at least how it tied into the story and characters. I realized after reading, however, that I was focused on it for the wrong reasons. Psyren isn’t a story about fated rivalries or destiny, but it’s about the issues with deeming people as “special.” Miroku, who is artificially created to BE special, is naturally, well, special. However, out of hatred for his captors, and for the human world that allowed such a thing to be acceptable, he seeks to remake the world to accommodate special people like himself. A world filed with PSI, where normal people are either given psychic powers, transformed into monsters, or killed.

Both normal humans and Psionists are portrayed as complicated people, not intrinsically good or evil. Not to say that every character is morally gray, but for every twisted monster from one group there’s a genuinely good, yet troubled person, or an awful person now attempting to do good.

Miroku attempts to ascend above the humans that made him. He attempts to distance himself from this gray cycle by establishing himself as the dominant force in this new world. However, in his final encounter with the heroes, he would get to meet his sister again, and through receiving her will, he recalled her words.

He realizes his mistake. In his delusions of grandeur, he lost track of what made humans truly happy. It’s easy to get lost in the despair of the modern world, as Psyren’s post-apocalyptic setting makes clear, but despite being capable of both great good and great evil, humans are simple beings that need only love to get by. In the final battle, Ageha as well is nearly killed, but is awakened by his friends calling out to him. In this battle, may I add, Ageha and Miroku work together for the first time, in order to defeat the embodiment of Psionic energy that was attempting to swallow the planet. Although unfortunately rushed thanks to the series’ early cancellation, the idea here is clear. The two opposites, the Sun and the Moon, manage to overcome the physical representation of the idea that some people are special, as in they are exempt from what makes humans human. Nobody can escape the nature of humanity within them, as much as a person may try to shut off their emotions, like Number 7 or Sakurako, or attempt to force everyone into subjugation, like Miroku or Grana, everybody is human, and everybody does what they believe is right for a cause they believe is just.

While I’m not here to analyze every character, the majority of the main cast serves to strengthen the general theme, while mainly serving as their own characters. Kyle’s overwhelming desire for the thrill of combat during the final arc when stakes are the highest they can be, Kirisaki’s cowardly nature coming back around and causing him to become an incredibly powerful anti-psychic powers combatant, and Oboro’s original nature of being a curious, slightly emotionless man becoming warped by his long trip through the future as he implants himself with Taboo cores, the power sources of the monsters that live in the future, and acts purely out of his own desires to have an interesting life, chaotically “supporting” the protagonists near the end. Most notably would be the main love interest, Sakurako Amamiya, who stores the emotions that she can’t handle away in her subconscious, becoming a cold woman. However, her deep thoughts become a sentient personality and threaten to overtake her, but through accepting this part of herself, the two sides may fight together, expressing both sides of her personality and both sides of humanity. Sakurako harnessing this power and fighting alongside it is an inherent contradiction. One part of her was born from hiding her emotions away, and the other is the result of lacking said emotions, so how can they both exist? The answer is, they are not so simple. They are people, they are humans. They have their own will beyond why and how they were created.

Getting back to Ageha for a moment, his character arc is not inherently a positive one. If it were purely positive, it likely wouldn’t get across the message the way the author wanted. My only complaint is how quickly he comes to terms with himself and his issues, but this is due to a forcefully rushed ending by cancellation and I’ll be discussing it nonetheless, as the core idea gets through, simply subpar execution.

In the final battle against Miroku Amagi, Ageha is overcome with rage at Miroku’s attempt to kill his sister and cut off the last bit of human connection he has stopping him from reaching true impartiality. His ability, the Melzez Door, takes over his body and gives him a new form, where he becomes unable to hold back his anger and hatred for this man. While it had been heavily suggested up to this point that the nature of humanity is to act according to one’s own beliefs and not what is correct or incorrect, Ageha here refuses to listen to Miroku, and simply crushes him. Whether this is morally justified or not, Ageha is becoming more and more like Miroku. Number 7 even notes that she chose Ageha to help her because he reminds her of Miroku.

In the aftermath of the fight, Ageha is once again worried by his own turbulent emotions. If Ageha represents destruction, then one can only invoke change by accepting the destruction within themselves, however Ageha was swallowed by it. The one who can change the world is one who can accept the destructive nature of humanity, not one who denies it as Miroku does.

Ageha struggles to accept, however. Naturally so, no one person can achieve true enlightenment, and “accepting destruction” is not a naturally positive thing either. The light and the dark, human nature, is complicated, nobody will ever be satisfied with one single conclusion, other than the one you decide for yourself.

The final battle is against Ouroboros, which was earlier mentioned to be a reference to the deity of creation and destruction, the snake which continuously swallows itself in an endless circle. Wholeness, infinity. Ageha confronts the present Miroku, in his new “monstrous” form. By becoming a monster, he’s able to confront humanity’s destroyer. However, he is gravely injured during the fight and nearly dies. He is awakened from his 6 month coma by his friends calling out for him. The only way for one to truly confront humanity’s, they must steep themselves in said darkness, but through the bonds and connections you’ve formed, you tether yourself to reality, no matter how far gone you may be, no matter how hopeless the future may be.

A common symbol that reappears throughout the series is phones. By picking up mysterious phone calls from Nemesis Q, later revealed to be Miroku’s sister Number 7, the heroes are transported into the future, so that they may find out the truth about Miroku for her. Although Number 7 portrays herself as a hardened, empty person, describing herself as above the good and bad that humans are so engulfed by, ultimately she began the story so that she could get closer to her brother and learn why he became such a person, even if she doesn’t say it like that.

Phones are the method through which the characters are able to communicate with themselves in the present and future. Phones connect people. Nemesis Q’s catchphrase whenever transporting the heroes between times is “This world is connected.” You see how it becomes relevant by the end of this manga. As much as it may feel impossible to communicate with people sometimes, or as much as you may feel like you can’t even communicate with yourself, through basic human kindness, embodied by Number 7 through her message to Miroku and telephones through their connection to Number 7 herself, the world may become connected once again, and we can face our future with a smile.

No matter what happens down the road, our world is connected. Thank you for reading.

#psyren#manga analysis#psyren analysis#manga art#shonen#shounen#weekly shonen jump#ageha yoshina#miroku amagi#amagi miroku

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

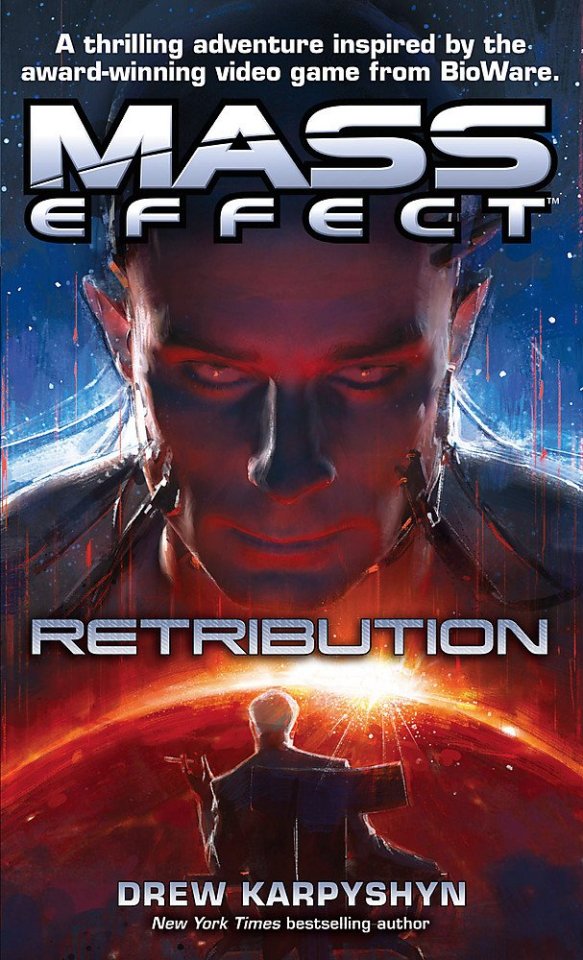

Mass Effect Retribution, a review

Mass Effect Retribution is the third book in the official Mass Effect trilogy by author Drew Karpyshyn, who happens to also be Lead Writer for Mass Effect 1 and Mass Effect 2.

I didn’t expect to pick it up, because to be very honest I didn’t expect to like it. 9 years ago I borrowed Mass Effect Revelations, and I still recall the experience as underwhelming. But this fateful fall of 2020 I had money (yay) and I saw the novel on the shelf of a swedish nerd store. I guess guilt motivated me to give the author another try: guilt, because I’ve been writing a Mass Effect fanfiction for an ungodly amount of years and I’ve been deathly afraid of lore that might contradict my decisions ever since I started -but I knew this book covered elements that are core to plot elements of my story, and I was willing to let my anxiety to the door and see what was up.

Disclaimer: I didn’t reread Mass Effect Revelation before plunging into this read, and entirely skipped Ascension. So anything in relation to character introduction and continuity will have to be skipped.

Back-cover pitch (the official, unbiased, long one)

Humanity has reached the stars, joining the vast galactic community of alien species. But beyond the fringes of explored space lurk the Reapers, a race of sentient starships bent on “harvesting” the galaxy’s organic species for their own dark purpose. The Illusive Man, leader of the pro-human black ops group Cerberus, is one of the few who know the truth about the Reapers. To ensure humanity’s survival, he launches a desperate plan to uncover the enemy’s strengths—and weaknesses—by studying someone implanted with modified Reaper technology. He knows the perfect subject for his horrific experiments: former Cerberus operative Paul Grayson, who wrested his daughter from the cabal’s control with the help of Ascension project director Kahlee Sanders. But when Kahlee learns that Grayson is missing, she turns to the only person she can trust: Alliance war hero Captain David Anderson. Together they set out to find the secret Cerberus facility where Grayson is being held. But they aren’t the only ones after him. And time is running out. As the experiments continue, the sinister Reaper technology twists Grayson’s mind. The insidious whispers grow ever stronger in his head, threatening to take over his very identity and unleash the Reapers on an unsuspecting galaxy. This novel is based on a Mature-rated video game.

Global opinion (TL;DR)

I came in hoping to be positively surprised and learn a thing or two about Reapers, about Cerberus and about Aria T’loak. I wasn’t, and I didn’t learn much. What I did learn was how cool ideas can get wasted by the very nature of game novelization, as the defects are not singular to this novel but quite widespread in this genre, and how annoyed I can get at an overuse of dialogue tags. The pacing is good and the narrative structure alright: everything else poked me in the wrong spots and rubbed how the series have always handled violence on my face with cruder examples. If I was on Good Reads, I’d probably give it something like 2 stars, for the pacing, some of the ideas, and my general sympathy for the IP novel struggle.

The indepth review continue past this point, just know there will be spoilers for the series, the Omega DLC which is often relevant, and the book itself!

What I enjoyed

Drew Karpyshyn is competent in narrative structure, and that does a lot for the pacing. Things rarely drag, and we get from one event to the next seamlessly. I’m not surprised this is one of the book’s qualities, as it comes from the craft of a game writer: pacing and efficiency are mandatory skills in this field. I would have preferred a clearer breaking point perhaps, but otherwise it’s a nice little ride that doesn’t ask a lot of effort from you (I was never tempted to DNF the book because it was so easy to read).

This book is packed with intringuing ideas -from venturing in the mind of the Illusive Man to assist, from the point of view of the victim, to Grayson’s biological transformation and assimilation into the Reaper hivemind, we get plenty to be excited for. I was personally intrigued about Liselle, Aria T’loak’s secret daughter, and eager to get a glimpse at the mind of the Queen Herself -also about how her collaboration with Cerberus came to be. Too bad none of these ideas go anywhere nor are being dealt with in an interesting way!!! But the concepts themselves were very good, so props for setting up interesting premices.

Pain is generally well described. It gets the job done.

I liked Sanak, the batarian that works as a second to Aria. He’s not very well characterized and everyone thinks he’s dumb (rise up for our national himbo), even though he reads almost smarter than her on multiple occasions, but I was happy whenever he was on the page, so yay for Sanak. But it might just be me having a bias for batarians.

Cool to have Kai Leng as a point of view character. I wasn’t enthralled by what was done with it, as he remains incredibly basic and as basically hateable and ungrounded than in Mass Effect 3 (I think he’s very underwhelming as a villain and he should have been built up in Mass Effect 2 to be effective). But there were some neat moments, such as the description of the Afterlife by Grayson who considers it as tugging at his base instincts, compared to Leng’s description of it where everything is deemed disgusting. The execution is not the best, but the concept was fun.

Pre-Reaperification Paul Grayson wasn’t the worst point of view to follow. I wasn’t super involved in his journey and didn’t care when he died one way or the other, but I empathized with his problems and hoped he would find a way out of the cycle of violence. The setup of his character arc was interesting, it’s just sad that any resolution -even negative- was dropped to focus on Reapers and his relationship with Kahlee Sanders, as I think the latter was the least interesting part.

The cover is cool and intringuing. Very soapy. It’s my favorite out of all the official novels, as it owns the cheesier aspect of the series, has nice contrasts and immediately asks questions. Very 90s/2000s. It’s great.

You may notice every thing I enjoyed was coated in complaints, because it’s a reflection of my frustration at this book for setting up interesting ideas and then completely missing the mark in their execution. So without further due, let’s talk about what I think the book didn’t do right.

1. Dumb complaints that don’t matter much

After reading the entire book, I am still a bit confused at to why Tim (the Illusive Man’s acronym is TIM in fandom, but I find immense joy in reffering to him as just Tim) wants his experimentation to be carried out on Grayson specifically, especially when getting to him is harder than pretty much anyone else (also wouldn’t pushing the very first experiments on alien captives make more sense given it’s Cerberus we’re talking about?). It seem to be done out of petty revenge, which is fine, but it still feels like quite the overlook to mess with a competent fighter, enhance him, and then expect things to stay under control (which Tim kind of doesn’t expect to, and that’s even weirder -why waste your components on something you plan to terminate almost immediately). At the same time, the pettiness is the only characterization we get out of Tim so good I guess? But if so, I wished it would have been accentuated to seem even more deliberate (and not have Tim regret to see it in himself, which flattens him and doesn’t inform the way he views the world and himself -but we’ll get to that).

I really disliked the way space travel is characterized. And that might be entirely just me, and perhaps it doesn’t contradict the rest of the lore, but space travel is so fast. People pop up left and right in a matter of hours. At some point we even get a mention of someone being able to jump 3 different Mass Relays and then arrive somewhere in 4 hours. I thought you first had to discharge your ship around a stellar object before being able to engage in the next jump (and that imply finding said object, which would have to take more than an hour). It’s not that big of a deal, but it completely crammed this giant world to a single boulevard for me and my hard-science-loving tastes. Not a big deal, but not a fan at all of this choice.

You wouldn’t believe how often people find themselves in a fight naked or in their underwear. It happens at least 3 times (and everyone naked survives -except one, we’ll get to her later).

Why did I need to know about this fifteen year’s old boner for his older teacher. Surely there were other ways to have his crush come across without this detail, or then have it be an actual point of tension in their relationship and not just a “teehee” moment. Weird choice imo.

I’m not a fan of the Talons. I don’t find them interesting or compelling. There is nothing about them that informs us on the world they live in. The fact they’re turian-ruled don’t tell us anything about turian culture that, say, the Blue Suns don’t tell us already. It’s a generic gang that is powerful because it is. I think they’re very boring, in this book and in the Omega DLC alike (a liiittle less in the DLC because of Nyreen, barely). Not a real criticism, I just don’t care for them at all.

I might just be very ace, but I didn’t find Anderson and Kahlee Sanders to have much chemistry. Same for Kahlee and Grayson (yes we do have some sort of love-triangle-but-not-really, but it’s not very important and it didn’t bother me much). Their relationships were all underwhelming to me, and I’ll explain why in part 4.

The red sand highs are barely described, and very safely -probably not from a place of intimate knowledge with drugs nor from intense research. Addiction is a delicate topic, and I feel like it could have been dealt with better, or not be included at all.

There are more of these, but I don’t want to turn this into a list of minor complaints for things that are more a matter of taste than craft quality or thematic relevance. So let’s move on.

2. Who cares about aliens in a Mass Effect novel

Now we’re getting into actual problems, and this one is kind of endemic to the Mass Effect novels (I thought the same when I read Revelation 9 years ago, though maybe less so as Saren in a PoV character -but I might have forgotten so there’s that). The aliens are described and characterized in the most uncurious, uninspired manner. Krogans are intimidating brutes. Turians are rigid. Asaris are sexy. Elcors are boring. Batarians are thugs (there is something to be said with how Aria’s second in command is literally the same batarian respawned with a different name in Mass Effect 2, this book, then the Omega DLC). Salarians are weak nerds. (if you allow me this little parenthesis because of course I have to complain about salarian characterization: the only salarian that speaks in the book talks in a cheap ripoff of Mordin’s speech pattern, which sucks because it’s specific to Mordin and not salarians as a whole, and is there to be afraid of a threat as a joke. This is SUCH a trope in the original trilogy -especially past Mass Effect 1 when they kind of give up on salarians except for a few chosen ones-, that salarians’ fear is not to be taken seriously and the only salarians who are to be considered don’t express fear at all -see Mordin and Kirrahe. It happens at least once per game, often more. This is one of the reasons why the genophage subplot is allowed to be so morally simple in ME3 and remove salarians from the equation. I get why they did that, but it’s still somewhat of a copeout. On this front, I have to give props to Andromeda for actually engaging with violence on salarians in a serious manner. It’s a refreshing change) I didn’t learn a single thing about any of these species, how they work, what they care about in the course of these 79750 words. I also didn’t learn much about their relationships to other species, including humans. I’ll mention xenophobia in more details later, but this entire aspect of the story takes a huge hit because of this lack of investment of who these species are.

I’ve always find Mass Effect, despite its sprawling universe full of vivid ideas and unique perspectives, to be strangely enamoured with humans, and it has never been so apparent than here. Only humans get to have layers, deserving of empathy and actual engagement. Only their pain is real and important. Only their death deserve mourning (we’ll come back to that). I’d speculate this comes from the same place that was terrified to have Liara as a love interest in ME1 in case she alienated the audience, and then later was surprised when half the fanbase was more interested in banging the dinosaur-bird than their fellow humans: Mass Effect often seem afraid of losing us and breaking our capacity for self-projection. It’s a very weird concern, in my opinion, that reveals the most immature, uncertain and soapy parts of the franchise. Here it’s punched to eleven, and I find it disappointing. It also have a surprising effect on the narrative: again, we’ll come back to that.

3. The squandered potential of Liselle and Aria

Okay. This one hurts. Let’s talk about Liselle: she’s introduced in the story as a teammate to Grayson, who at the time works as a merc for Aria T’loak on Omega, and also sleeps with him on the regular. She likes hitting the Afterlife’s dancefloor: she’s very admired there, as she’s described as extremely attractive. One night after receiving a call from Grayson, she rejoins him in his apartment. They have sex, then Kai Leng and other Cerberus agents barge in to capture Grayson -a fight break out (the first in a long tradition of naked/underwear fights), and both of them are stunned with tranquilizers. Grayson is to be taken to the Illusive Man. Kai Leng decides to slit Liselle’s throat as she lays unconscious to cover their tracks. When Aria T’loak and her team find her naked on a bed, throat gaping and covered in blood, Liselle is revealed, through her internal monologue, to be Aria’s secret daughter -that she kept secret for both of their safety. So Liselle is a sexpot who dies immediately in a very brutal and disempowered manner. This is a sad way to handle Aria T’loak’s daughter I think, but I assume it was done to give a strong motivation to the mother, who thinks Grayson did it. And also, it’s a cool setup to explore her psyche: how does she feel about business catching up with her in such a personal manner, how does she feel about the fact she couldn’t protect her own offspring despite all her power, what’s her relationship with loss and death, how does she slip when under high emotional stress, how does she deal with such a vulnerable position of having to cope without being able to show any sign of weakness... But the book does nothing with that. The most interesting we get is her complete absence of outward reaction when she sees her daughter as the centerpiece of a crime scene. Otherwise we have mentions that she’s not used to lose relatives, vague discomfort when someone mentions Liselle might have been raped, and vague discomfort at her body in display for everyone to gawk at. It’s not exactly revelatory behavior, and the missed potential is borderline criminal. It also doesn’t even justify itself as a strong motivation, as Aria vaguely tries to find Grayson again and then gives up until we give her intel on a silver platter. Then it almost feels as if she forgot her motivation for killing Grayson, and is as motivated by money than she is by her daughter’s murder (and that could be interesting too, but it’s not done in a deliberate way and therefore it seems more like a lack of characterization than anything else).

Now, to Aria. Because this book made me realize something I strongly dislike: the framing might constantly posture her as intelligent, but Aria T’loak is... kind of dumb, actually? In this book alone she’s misled, misinformed or tricked three different times. We’re constantly ensured she’s an amazing people reader but never once do we see this ability work in her favor -everyone fools her all the time. She doesn’t learn from her mistakes and jump from Cerberus trap to Cerberus trap, and her loosing Omega to them later is laughably stupid after the bullshit Tim put her through in this book alone. I’m not joking when I say the book has to pull out an entire paragraph on how it’s easier to lie to smart people to justify her complete dumbassery during her first negotiation with Tim. She doesn’t seem to know anything about how people work that could justify her power. She’s not politically savvy. She’s not good at manipulation. She’s just already established and very, very good at kicking ass. And I wouldn’t mind if Aria was just a brutish thug who maintains her power through violence and nothing else, that could also be interesting to have an asari act that way. But the narrative will not bow to the reality they have created for her, and keep pretending her flaw is in extreme pride only. This makes me think of the treatment of Sansa Stark in the latest seasons of Game of Thrones -the story and everyone in it is persuaded she’s a political mastermind, and in the exact same way I would adore for it to be true, but it’s just... not. It’s even worse for Aria, because Sansa does have victories by virtue of everyone being magically dumber than her whenever convenient. Aria just fails, again and again, and nobody seem to ever acknowledge it. Sadly her writing here completely justifies her writing in the Omega DLC and the comics, which I completely loathe; but turns out Aria isn’t smart or savvy, not even in posture or as a façade. She’s just violent, entitled, easily fooled, and throws public tantrums when things don’t go her way. And again, I guess that would be fine if only the narrative would recognize what she is. Me, I will gently ignore most of this (in her presentation at least, because I think it’s interesting to have something pitiful when you dig a little) and try to write her with a bit more elevation. But this was a very disappointing realization to have.

4. The squandered potential of Grayson and the Reapers

The waste of a subplot with Aria and Liselle might have hurt me more in a personal way, but what went down between Grayson and the Reapers hurts the entire series in a startling manner. And it’s so infuriating because the potential was there. Every setpiece was available to create something truly unique and disturbing by simply following the series’ own established lore. But this is not what happens. See, when The Illusive Man, our dearest Tim, captures Grayson for a betrayal that happened last book (something about his biotic autistic daughter -what’s the deal with autistic biotics being traumatized by Cerberus btw), he decides to use him as the key part of an experiment to understand how Reapers operate. So he forcefully implants the guy with Reaper technology (what they do exactly is unclear) to study his change into a husk and be prepared when Reapers come for humanity -it’s also compared to what happened with Saren when he “agreed” to be augmented by Sovereign. From there on, Grayson slowly turns into a husk. Doesn’t it sound fascinating, to be stuck in the mind of someone losing themselves to unknowable monsters? If you agree with me then I’m sorry because the execution is certainly... not that. The way the author chooses to describe the event is to use the trope of mind control used in media like Get Out: Grayson taking the backseat of his own mind and body. And I haaaaate it. I hate it so much. I don’t hate the trope itself (it can be interesting in other media, like Get Out!), but I loathe that it’s used here in a way that totally contradicts both the lore and basic biology. Grayson doesn’t find himself manipulated. He doesn’t find himself justifying increasingly jarring actions the way Saren has. He just... loses control of himself, disagreeing with what’s being done with him but not able to change much about it. He also can fight back and regain control sometimes -but his thoughts are almost untainted by Reaper influence. The technology is supposed to literally replace and reorganize the cells of his body; is this implying that body and mind are separated, that there maybe exists a soul that transcends indoctrination? I don’t know but I hate it. This also implies that every victim of the Reaper is secretely aware of what they’re doing and pained and disagreeing with their own actions. And I’m sorry but if it’s true, I think this sucks ass and removes one of the creepiest ideas of the Mass Effect universe -that identity can and will be lost, and that Reapers do not care about devouring individuality and reshaping it to the whims of their inexorable march. Keeping a clear stream of consciousness in the victim’s body makes it feel like a curse and not like a disease. None of the victims are truly gone that way, and it removes so much of the tragic powerlessness of organics in their fight against the machines. Imagine if Saren watched himself be a meanie and being like “nooo” from within until he had a chance to kill himself in a near-victorious battle, compared to him being completely persuaded he’s acting for the good of organic life until, for a split second, he comes to realize he doesn’t make any sense and is loosing his mind like someone with dementia would, and needs to grasp to this instant to make the last possible thing he could do to save others and his own mind from domination. I feel so little things for Saren in the former case, and so much for the latter. But it might just be me: I’m deeply touched by the exploration of how environment and things like medication can change someone’s behavior, it’s such a painfully human subject while forceful mind control is... just kind of cheap.

SPEAKING OF THE REAPERS. Did you know “The Reapers” as an entity is an actual character in this book? Because it is. And “The Reapers” is not a good character. During the introduction of Grayson and explaining his troubles, we get presented with the mean little voice in his head. It’s his thoughts in italics, nothing crazy, in fact it’s a little bit of a copeout from actually implementing his insecurities into the prose. But I gave the author the benefit of the doubt, as I knew Grayson would be indoctrinated later, and I fully expected the little voice to slowly start twisting into what the Reapers suggested to him. This doesn’t happen, or at least not in that slowburn sort of way. Instead the little voice is dropped almost immediately, and the Reapers are described, as a presence. And as the infection progresses, what Grayson do become what the Reapers do. The Reapers have emotions, it turns out. They’re disgusted at organic discharges. They’re pleased when Grayson accomplish what they want, and it’s told as such. They foment little plans to get their puppet to point A to point B, and we are privy to their calculations. And I’m sorry but the best way to ruin your lovecraftian concept is to try and explain its motivations and how it thinks. Because by definition the unknown is scarier, smarter, and colder than whatever a human author could come up with. I couldn’t take the Reapers’ dumb infiltration plans seriously, and now I think they are dumb all the time, and I didn’t want to!! The only cases in which the Reapers influence Grayson, we are told in very explicit details how so. For example, they won’t let Grayson commit suicide by flooding his brain with hope and determination when he tries, or they will change the words he types when he tries to send a message to Kahlee Sanders. And we are told exactly what they do every time. There was a glorious occasion to flex as a writer by diving deep into an unreliable narrator and write incredibly creepy prose, but I guess we could have been confused, and apparently that’s not allowed. And all of this is handled that poorly becauuuuuse...

5. Subtext is dead and Drew killed it

Now we need to talk about the prose. The style of the author is... let’s be generous and call it functional. It’s about clarity. The writing is so involved in its quest for clarity that it basically ruins the book, and most of the previous issues are direct consequences of the prose and adjacent decisions.The direct prose issues are puzzling, as they are known as rookie technical flaws and not something I would expect from the series’ Lead Writer for Mass Effect 1 and 2, but in this book we find problems such as:

The reliance on adverbs. Example: "Breathing heavily from the exertion, he stood up slowly”. I have nothing about a well-placed adverb that gives a verb a revelatory twist, but these could be replaced by stronger verbs, or cut altogether.

Filtering. Example: “Anderson knew that the fact they were getting no response was a bad sign”. This example is particularly egregious, but characters know things, feel things, realize things (boy do they realize things)... And this pulls us away from their internal world instead of making us live what they live, expliciting what should be implicit. For example, consider the alternative: “They were getting no reponse, which was a bad sign in Anderson’s experience.” We don’t really need the “in Anderson’s experience” either, but that already brings us significantly closer to his world, his lived experience as a soldier.

The goddamn dialogue tags. This one is the worst offender of the bunch. Nobody is allowed to talk without a dialogue tag in this book, and wow do people imply, admit, inform, remark and every other verb under the sun. Consider this example, which made me lose my mind a little: “What are you talking about? Kahlee wanted to know.” I couldn’t find it again, but I’m fairly certain I read a “What is it?” Anderson wanted to know. as well. Not only is it very distracting, it’s also yet another way to remove reader interpretation from the equation (also sometimes there will be a paragraph break inside a monologue -not even a long one-, and that doesn’t seem to be justified by anything? It’s not as big of a problem than the aversion to subtext, but it still confused me more than once)

Another writing choice that hurts the book in disproportionate ways is the reliance on point of view switches. In Retribution, we get the point of view of: Tim, Paul Grayson, Kai Leng, Kahlee Sanders, David Anderson, Aria T’loak, and Nick (a biotic teenager, the one with the boner). Maybe Sanak had a very small section too, but I couldn’t find it again so don’t take my word for it. That’s too many point of views for a plot-heavy 80k book in my opinion, but even besides that: the point of view switch several times in one single chapter. This is done in the most harmful way possible for tension: characters involved in the same scene take turns on the page explaining their perspective about the events, in a way that leaves the reader entirely aware of every stake to every character and every information that would be relevant in a scene. Take for example the first negotiation between Aria and Tim. The second Aria needs to ponder what her best move could possibly be, we get thrown back into Tim’s perspective explaining the exact ways in which he’s trying to deceive her -removing our agency to be either convinced or fooled alongside her. This results in a book that goes out of his way to keep us from engaging with its ideas and do any mental work on our own. Everything is laid out, bare and as overexplained as humanly possible. The format is also very repetitive: characters talk or do an action, and then we spend a paragraph explaining the exact mental reasoning for why they did what they did. There is nothing to interpret. No subtext at all whatsoever; and this contributes in casting a harsh light on the Mass Effect universe, cheapening it and overtly expliciting some of its worst ideas instead of leaving them politely blurred and for us to dress up in our minds. There is only one theme that remains subtextual in my opinion. And it’s not a pretty one.

6. Violence

So here’s the thing when you adapt a third person shooter into a novel: you created a violent world and now you will have to deal with death en-masse too (get it get it I’m so sorry). But while in videogames you can get away with thoughtless murder because it’s a gameplay mechanic and you’re not expected to philosophize on every splatter of blood, novels are all about internalization. Violent murder is by definition more uncomfortable in books, because we’re out of gamer conventions and now every death is actual when in games we just spawned more guys because we wanted that level to be a bit harder and on a subconscious level we know this and it makes it somewhat okay. I felt, in this book, a strange disconnect between the horrendous violence and the fact we’re expected to care about it like we would in a game: not much, or as a spectacle. Like in a game, we are expected to root for the safety of named characters the story indicated us we should be invested in. And because we’re in a book, this doesn’t feel like the objective truth of the universe spelled at us through user interface and quest logs, but the subjective worldview of the characters we’re following. And that makes them.... somewhat disturbing to follow.

I haven’t touched on Anderson and Kahlee Sanders much yet, but now I guess I have too, as they are the worst offenders of what is mentioned above. Kahlee cares about Grayson. She only cares about Grayson -and her students like the forementioned Nick, but mostly Grayson. Grayson is out there murdering people like it’s nobody’s business, but still, keeping Grayson alive is more important that people dying like flies around him. This is vaguely touched on, but not with the gravitas that I think was warranted. Also, Anderson goes with it. Because he cares about Kahlee. Anderson organizes a major political scandal between humans and turians because of Kahlee, because of Grayson. He convinces turians to risk a lot to bring Cerberus down, and I guess that could be understandable, but it’s mostly manipulation for the sake of Grayson’s survival: and a lot of turians die as a result. But not only turians: I was not comfortable with how casually the course of action to deal a huge blow to Cerberus and try to bring the organization down was to launch assault on stations and cover-ups for their organization. Not mass arrests: military assault. They came to arrest high operatives, maybe, but the grunts were okay to slaughter. This universe has a problem with systemic violence by the supposedly good guys in charge -and it’s always held up as the righteous and efficient way compared to these UGH boring politicians and these treaties and peace and such (amirite Anderson). And as the cadavers pile up, it starts to make our loveable protagonists... kind of self-centered assholes. Also: I think we might want to touch on who these cadavers tend to be, and get to my biggest point of discomfort with this novel.

Xenophobia is hard to write well, and I super sympathize with the attempts made and their inherent difficulty. This novel tries to evoke this theme in multiple ways: by virtue of having Cerberus’ heart and blade as point of view characters, we get a window into Tim and Kai Leng’s bigotry against aliens, and how this belief informs their actions. I wasn’t ever sold in their bigotry as it was shown to us. Tim evokes his scorn for whatever aliens do and how it’s inferior to humanity’s resilience -but it’s surface-level, not informed by deep and specific entranched beliefs on aliens motives and bodies, and how they are a threat on humanity according to them. The history of Mass Effect is rich with conflict and baggage between species, yet every expression of hatred is relegated to a vague “eww aliens” that doesn’t feed off systemically enforced beliefs but personal feelings of mistrust and disgust. I’ll take this example of Kai Leng, and his supposedly revulsion at the Afterlife as a peak example of alien decadence: he sees an asari in skimpy clothing, and deems her “whorish”. And this feels... off. Not because I don’t think Kai Leng would consider asaris whorish, but because this is supposed to represent Cerberus’ core beliefs: yet both him and Tim go on and on about how their goal is to uplift humanity, how no human is an enemy. But if that’s the case, then what makes Kai Leng call an Afterlife asari whorish and mean it in a way that’s meaningfully different from how he would consider a human sex worker in similar dispositions? Not that I don’t buy that Cerberus would have a very specific idea of what humans need to be to be considered worth preserving as good little ur-fascists, but this internal bias is never expressed in any way, and it makes the whole act feel hollow. Cerberus is not the only offender, though. Every time an alien expresses bias against humans in a way we’re meant to recognize as xenophobic, it reads the same way: as personal dislike and suspicion. As bullying. Which is such a small part of what bigotry encompasses. It’s so unspecific and divorced from their common history that it just never truly works in my opinion. You know what I thought worked, though? The golden trio of non-Cerberus human characters, and their attitude towards aliens. Grayson’s slight fetishism and suspicion of his attraction to Liselle, how bestial (in a cool, sexy way) he perceives the Afterlife to be. The way Anderson and Kahlee use turians for their own ends and do not spare a single thought towards those who died directly trying to protect them or Grayson immediately after the fact (they are more interested in Kahlee’s broken fingers and in kissing each other). How they feel disgust watching turians looting Cerberus soldiers, not because it’s disrespectful in general and the deaths are a inherent tragedy but because they are turians and the dead are humans. But it's not even really on them: the narration itself is engrossed by the suffering of humans, but aliens are relegated to setpieces in gore spectacles. Not even Grayson truly cares about the aliens the Reapers make him kill. Nobody does. Not even the aliens among each other: see, once again, Aria and Liselle, or Aria and Sanak. Nobody cares. At the very end of the story, Anderson comes to Kahlee and asks if she gives him permission to have Grayson’s body studied, the same way Cerberus planned to. It’s source of discomfort, but Kahlee gives in as it’s important, and probably what Grayson would have wanted, maybe? So yeah. In the end the only subtextual theme to find here (probably as an accident) is how the Alliance’s good guys are not that different from Cerberus it turns out. And I’m not sure how I feel about that.

7. Lore-approved books, or the art of shrinking an expanding universe

I’d like to open the conversation on a bigger topic: the very practice of game novelization, or IP-books. Because as much as I think Drew Karpyshyn’s final draft should not have ended up reading that amateur given the credits to his name, I really want to acknowledge the realities of this industry, and why the whole endeavor was perhaps doomed from the start regardless of Karpyshyn’s talent or wishes as an author.

The most jarring thing about this reading experience is as follows: I spent almost 80k words exploring this universe with new characters and side characters, all of them supposedly cool and interesting, and I learned nothing. I learned nothing new about the world, nothing new about the characters. Now that it’s over, I’m left wondering how I could chew on so much and gain so little. Maybe it’s just me, but more likely it’s by design. Not on poor Drew. Now that I did IP work myself, I have developed an acute sympathy for anyone who has to deal with the maddening contradictions of this type of business. Let me explain.

IP-adjacent media (in the West at least) sure has for goal to expand the universe: but expand as in bloat, not as in deepen. The target for this book is nerds like me, who liked the games and want more of this thing we liked. But then we’re confronted by two major competitors: the actual original media (in ME’s case, the games) whose this product is a marketing tool for, and fandom. IP books are not allowed to compete with the main media: the good ideas are for the main media, and any meaningful development has to be made in the main media (see: what happened with Kai Leng, or how everyone including me complains about the worldbuilding to the Disney Star Swars trilogy being hidden in the novelization). And when it comes to authorship (as in: taking an actual risk with the media and give it a personal spin), then we risk introducing ideas that complicate the main media even though a ridiculously small percent of the public will be attached to it, or ideas that fans despise. Of course we can’t have the latter. And once the fandom is huge enough, digging into anything the fans have strong headcanons for already risks creating a lot of emotions once some of these are made canon and some are disregarded. As much as I joke about how in Mass Effect you can learn about any gun in excrutiating details but we still don’t know if asaris have a concept for marriage... would we really want to know how/if asaris marry, or aren’t we glad we get to be creative and put our own spin on things? The dance between fandom and canon is a delicate one that can and will go wrong. And IP books are generally not worth the drama for the stakeholders.