#they teach the revolutionary war so many times in school

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

We've literally been killing people to resolve policy differences and express a viewpoint since the begining. That is in fact a thing we historically do.

#they teach the revolutionary war so many times in school#which is did involve killing a lot of people over a policy change#if king george iii hadn't been an ocean away#i'm sure they might have tried taking out the source of their problems#we have unions because the alternative was taring and feathering or murder#us politics#current events

48K notes

·

View notes

Text

Interview With a Writer

It is that blessed time when the wonderful and talented Miss Maggie, @inthedayswhenlandswerefew, gives us some behind-the-scenes insight to her latest brilliant narration. [Feel free to check out the Spotify playlist of all the songs mentioned and let me know if I forgot one!]

Here is masterlist to my Interview With a Writer series and the other talented individuals who allow me to continue this self-indulgent series! 💜 Picture(s) source.

Name: inthedayswhenlandswerefew

Story: 1968

Paring: modern Aemond Targaryen x female!reader, modern Aegon Targaryen x female!reader

Warnings: 18+ mature themes. Be mindful of chapter warnings.

Where did the idea for 1968 come from?

I am a high school social studies teacher by trade, and my absolute favorite class to teach is American History. The 1960s and 70s were actually one of my weak spots when I got my first teaching job back in 2020, so I ended up researching a lot about that period of time and got absolutely obsessed with it. In my American History class, I spend a whole lesson on JUST 1968, because so many important events happened in that year that are emblematic of broader trends and tensions.

One day I was re-reading one of my favorite books, The Other Mrs. Kennedy by Jerry Oppenheimer, which is specifically about Bobby Kennedy’s wife Ethel, but also gives a lot of insight into the Kennedy family generally and what it was like to live through that era. The idea of using this setting as a fic AU occurred to me, and I ruminated on it for a few weeks while finishing up Napoleonville.

Eventually, I had a revelation of the ending of 1968 (true to my usual pattern), and then knew I’d have to write the fic! I was actually really worried about all the political and historical details being too boring and/or confusing (especially for non-U.S. readers), so I was relieved that so many people gave it a chance. 🥰

Honestly, it was brilliant with the similarities to the Kennedys and Targaryens in the story. Were there any historical cameos in 1968 that you enjoyed channeling? Or perhaps struggled with?

I find LBJ super fascinating, and I feel that because of the Vietnam War he really doesn’t get a fair assessment when people look back on his presidency. His work for civil rights and the Great Society (SNAP, Medicaid, Head Start, Job Corps, PBS, etc.) was truly revolutionary, and as someone who grew up in poverty and benefitted from a lot of those programs, I don’t think LBJ’s contributions get the recognition and praise they deserve. I perceive him as a haunted sort of figure, and I really enjoyed his cameos. (To be clear, he was also super problematic and bizarre personally, and I don’t mean to excuse any of that 😂).

As for someone who was difficult to write about…honestly, the George Wallace research I did was super depressing, so while he was necessary to include, I didn’t really enjoy working on those parts!

Was there anything in specific that inspired your Reader portrayal?

Io is a bit of a composite sketch. Ethel Kennedy was known as doggedly committed to her husband’s career above all else (despite eventually being the mother of 11 children!!), and I think that inspired Io’s single-minded determination to help Aemond win the election in the first few chapters. Ethel was traditional in the sense that her husband was the center of her world and made all the important decisions, as was expected of women of her social class in that time period. But Io is also a manifestation of the counterculture of the late-60s. She is young, educated, genuinely progressive politically, and likes to party. She tries to reconcile the expectations of her family/time period and her actual personality by intentionally choosing a husband with whom she can have an equal partnership making the world a better place. And…we all know how that worked out.

[Photo Ethel and Bobby Kennedy, m. 1950]

Can you explain your interpretation of Aegon? How does he compare and contrast to Aemond? What drives them? Why are they the way that they are?

In 1968, Aegon is 40 years old, and so his role in the Targaryen political dynasty is very well-established: once his family realized he couldn’t be weaponized for their purposes, he was largely disposed of, and lives this aimless, uninspired, self-loathing sort of existence. He does have some genuine love for his family—missing Daeron and feeling guilt over him being sent to Vietnam, a vague sort of fondness for Mimi and the kids, distress when Aemond is shot in Palm Beach, an apology of sorts to Alicent by performing “Mama Tried” at her birthday party—but Aegon exists on the periphery, and he knows this, and while he doesn’t want to be a politician the rejection still stings.

At first, he perceives Io as yet another person who makes him feel inadequate and unloved; and in fairness, she is cruel to him, in fact more so than Aegon is to Io in return. It is noteworthy that in Chapter 1, she viciously criticizes Aegon in front of everyone in the waiting room (“if someone had to get killed tonight it should have been you”), but he doesn’t return fire until they are alone (the infamous cow comment), and even then he seems to regret it immediately.

Aegon, fundamentally, is more sad than mean. When in Chapters 2 and 3 Io abruptly reveals herself to be someone who is vulnerable, wounded, abandoned, and kind of a hippie lowkey, Aegon begins to perceive her differently, and she becomes an opportunity for him to be truly understood, protected, and loved for the first time in his life.

I think we would all describe Aemond as ambitious and ruthless, determined to prove that he is the best to compensate for deep, lifelong insecurities. He is a progressive politically because he sees a path to build a winning coalition, and perhaps in small part because of the whole Greeks-being-despised immigrants thing. But in 1968 there is a sense that you never fully understand who he is as a person. This is intentional! 1968 is Io’s story, and she never gets to see the whole Aemond. She sees parts of the picture, but never the full image. As awful as he is to Io, there is also a side of Aemond that truly (even if in an…unorthodox way 😂) loves Alys and their child, and there are clues that Alys understands him like no one else can (that Ouija board message… 👀). He’s by no means a good guy, but he is multifaceted. I think the stress of the presidency, and his long separation from Alys, ends up softening Aemond a bit, hence him defending Io’s reputation and ultimately letting her go.

Did anything inspire your other OCs? Specifically "The Ones Who Married In" club?

I didn’t sit down and plan what sorts of characters would be in the “The Ones Who Married In” club. I was possessed by these random visions of them: a perpetually drunk Mimi, a perhaps not too bright but very sweet Fosco, and Malibu Barbie but make her Polish Ludwika, and I was thinking: “These people are ridiculous, this will never work!” But then when I thought about it more, I realized that Mimi, Fosco, Ludwika, and Io all serve strategic roles to help advance Aemond’s career, and so it would make sense that Otto and Aemond cobbled them together and shoved them into the family portraits. I ended up really loving them, but they weren’t a big part of my original outline for 1968. 🙂

How would Io rate them based on her friendship with each of them?

Fosco is definitely #1; they connect on an emotional level that is deep but also largely unspoken. Ludwika is a close #2; she’s Io’s shopping buddy but also witty, supportive, and very feminist in her own way. And then Mimi is a distant #3. Io pities Mimi and feels loyalty to her as a fellow Targaryen, and goes out of her way to try to protect Mimi from her own self-destructive tendencies. But Io, as a collected and self-reliant person, also has difficulty understanding and dealing with someone as messy as Mimi. And of course, once Io realizes she is super into Aegon, that creates some one-sided resentment of Mimi!

Do you have a feeling of what happened after chapter 12? What is the ending you vaguely see with Aegon and Io? What about Aemond and Alys?

Where I end a fic is really the last clear image I see of the characters, so I sadly don’t have a lot of specifics to offer. What I do feel is that Io and Aegon have children of their own (like, several children, maybe even 5+ children) and Aegon is present for their early years in a way he wasn’t able to be for his kids with Mimi. Io is a stepmom to Aegon’s OG kids and has a good relationship with them, but she’s only really close with Cosmo.

I also sense that Aemond has basically no contact with Io or Aegon, which makes sense considering his abuse of Io and the lifelong fury Aegon would therefore have towards him. Aemond is happy with Alys and their son (as happy as someone like him is capable of being); he does the ex-president thing and settles into a largely ceremonial role and advises Democratic politicians, although he is not very friendly with President Reagan.

And then my wild theory is that a Daeron/John McCain ticket ends up winning the 2000 election and the War On Terror plays out completely differently!

And finally... 1968 seemed to pour from you like a fever dream. Does this mean something else might be coming to continue the Maggie's Suffering Sunday tradition?

1968 did seem to fly by, despite it being a longer fic at 12 chapters! I do have something planned for this Sunday... 😉 All I can say for now is that it is very weird, totally unexpected, and tonally a mashup of Comet Donati and When The World Is Crashing Down.

Does that seem impossible?? Think again 😏 I will be reblogging hints until Sunday! I hope you enjoy this new journey 🥰🐍

33 notes

·

View notes

Text

by Christopher Rufo

Portland, Oregon, has earned its reputation as America’s most radical city. Its public school system was an early proponent of left-wing racialism and has long pushed students toward political activism. As with the death of George Floyd four years ago, the irruption of Hamas terrorism in Israel has provided Portland’s public school revolutionaries with another cause du jour: now they’ve ditched the raised fist of Black Lives Matter and traded it in for the black-and-white keffiyeh of Palestinian militants.

I have obtained a collection of publicly accessible documents produced by the Portland Association of Teachers, an affiliate of the state teachers’ union that encourages its more than 4,500 members to “Teach Palestine!” (The union did not respond to a request for comment.)

The lesson plans are steeped in radicalism, and they begin teaching the principles of “decolonization” to students as young as four and five years old. For prekindergarten kids, the union promotes a workbook from the Palestinian Feminist Collective, which tells the story of a fictional Palestinian boy named Handala. “When I was only ten years old, I had to flee my home in Palestine,” the boy tells readers. “A group of bullies called Zionists wanted our land so they stole it by force and hurt many people.” Students are encouraged to come up with a slogan that they can chant at a protest and complete a maze so that Handala can “get back home to Palestine”—represented as a map of Israel.

Other pre-K resources include a video that repeats left-wing mantras, including “I feel safe when there are no police,” and a slideshow that glorifies the Palestinian intifada, or violent resistance against Israel. The recommended resource list also includes a “sensory guide for kids” on attending protests. It teaches children what they might see, hear, taste, touch, and smell at protests, and promotes photographs of slogans such as “Abolish Prisons” and “From the River to the Sea.”

In kindergarten through second grade, the ideologies intensify. The teachers’ union recommends a lesson, “Art and Action for Palestine,” that teaches students that Israel, like America, is an oppressor. The objective is to “connect histories of settler colonialism from Palestine to the United States” and to “celebrate Palestinian culture and resistance throughout history and in the present, with a focus on Palestinian children’s resistance.”

The lesson suggests that teachers should gather the kindergarteners into a circle and teach them a history of Palestine: “75 years ago, a lot of decision makers around the world decided to take away Palestinian land to make a country called Israel. Israel would be a country where rules were mostly fair for Jewish people with White skin,” the lesson reads. “There’s a BIG word for when Indigenous land gets taken away to make a country, that’s called settler colonialism.”

Before snack time, the teacher is encouraged to share “keffiyehs, flags, and protest signs” with the children, and have them create their own agitprop material, with slogans such as “FREE PALESTINE, LET GAZA LIVE, [and] PALESTINE WILL BE FREE.” The intention, according to the lesson, is to move students toward “taking collective action in support of Palestinian liberation.”

The recommended curriculum also includes a pamphlet titled “All Out for Palestine.” The pamphlet is explicitly political, with a sub-headline blaring in all capital letters: “STOP THE GENOCIDE! END U.S. AID TO IRSAEL! FREE PALESTINE!” The authors denounce “Zionism’s long genocidal war on Palestinian life” and encourage students to support “boycott, divestment, and sanctions” policies against Israel.

The pamphlet includes chants that teachers can adopt in the classroom. Some imply support for militancy and political violence: “Resistance is justified when people are occupied!”; “We salute all our martyrs! mothers, fathers, sons and daughters!”; “Justice is our demand! No peace on stolen land!”

It’s not immediately clear to what extent the “Teach Palestine!” lessons have been adopted in Portland public school classrooms. But the teachers’ union claims that the district has been “actively censoring teachers” for promoting pro-Palestine ideologies; in response, it has assembled a legal guide for how teachers can keep promoting the lessons under the guise of meeting state curriculum standards.

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

Period dramas- El Mestre Que Va Prometre El Mar (The teacher who promised the sea) (2023)

7,7/10 ⭐ on IMDB

The film focuses on the life of Antoni Benaiges , a teacher from Mont-roig del Camp, in the Baix Camp, in Tarragona, Catalunya, who in 1935 was sent to the public school in Bañuelos de Bureba, a small town in the province of Burgos, Castilla la Vieja (Castilla y León). Little by little, and thanks to a pioneering and revolutionary teaching methodology for the time, he will begin to transform the lives of his students, but also that of the town, which is not always to everyone's taste.

It's based on the book of the same name by Francesc Escribano and has been adapted for the big screen by Albert Val, and its director is Patrícia Font.

To tell the story of Antoni Benaiges (Enric Auquer), the film interweaves past and present and the master's story will be known through the eyes of Ariadna (Laia Costa), a woman looking for her great-grandfather who disappeared during the Civil War.

The producers of the film wanted to emphasize the essence of this exciting story: " 'El mestre que va prometre el mar' is a great story that has been unfairly forgotten for many years. With this film we are repairing an oblivion and at the same time valuing the work of the republican teachers and recognizing the struggle of so many people who still continue to search for their relatives buried anonymously in mass graves. An exciting and fully valid story.

Part of the technical team is made up of David Valldepérez, director of photography; Josep Rosell, art director; Dani Arregui, editor, and Natasha Arizu, composer, among other professionals.

The film is shot for six weeks in various locations in the demarcation of Barcelona, in Mura, and in Briviesca (Burgos). It is a production of Minoria Absoluta, Lastor Media, Filmax and Mestres Films AIE.

RTVE and TV3 participate and it has the support of the ICAA and the ICEC . Filmax is in charge of distribution to cinemas.

Length: 1 h 45 min

Premiere: November 10th 2023

Cast

Enric Auquer: Antoni Benaiges

Laia Costa: Ariadna

Luisa Gavasa: Charo

Ramón Agirre: Adult Ramón

Gael Aparicio: Carlos

Alba Hermoso: Josefina

Nicolás Calvo: Emilio

Antonio Mora: Mayor

Milo Taboada: Priest Primitivo

Jorge Da Rocha: Camilo

Eduardo Ferrés: Rodríguez

Alba Guilera: Laura

Laura Conejero: Rosa

Xavi Francés: Education inspector

David Climent: Falangist Chief

Felipe García Vélez: Adult Carlos

Elisa Crehuet: Adult Josefina

Padi Padilla: Encarna

Alicia Reyero: Ángeles

Gema Sala: Jacinta

Alía Torres: Ariadna's daughter

Carlos Troya: Bernardo Ramírez

Arnau Casanovas: Portraitist

Laura Gaja: Elvira

María Escoda: Juana

Chus Gutiérrez: Archivist

Joan Scufesis: Sergio

Cristina Murillo: Residency nurse

Sara Madrid: Hiker

Pep Linares: Falangist waiter

Albert Malla: Radio announcer

Izan Barragán: Leandro (School boy)

Didac Cano: Casimiro (School boy)

Hernán Gracia: Eulogio (School boy)

Noa Guillén: Asunción (School girl)

Ona Macía: Saturnina (School girl)

Elena Moreno: Dionisia (School girl)

Gal-La Petit: Hilaria (School girl)

Genís Lama: Falangist

#el mestre que va prometre el mar#the teacher who promised the sea#films#period dramas#Youtube#enric auquer#laia costa#luisa gavasa#ramón agirre#gael aparicio#alba hermoso#nicolás calvo#antonio mora#milo taboada#jorge da rocha#eduardo ferrés#alba guilera#laura conejero#xavi francés#david climent#felipe garcía vélez#antoni benaiges#elisa crehuet#padi padilla#alicia reyero#gema sala#alía torres#carlos troya#arnau casanovas#laura gaja

36 notes

·

View notes

Text

Incoming extra long post 💜

Pushing something a little different today-

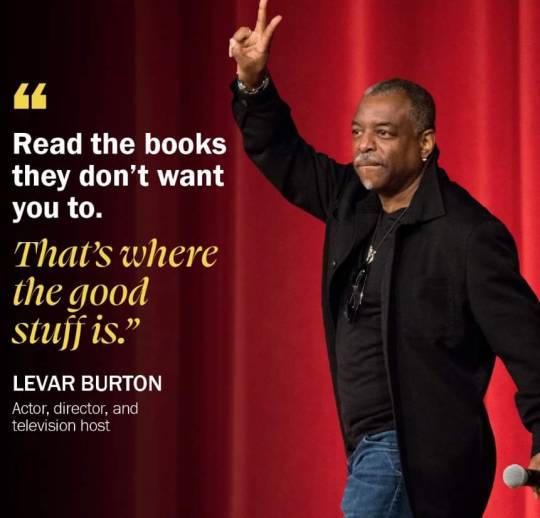

Let's talk banned and challenged books

Warnings- this post is going to mention racial and gender issues, violence, and use some foul language. I do not graphically discuss anything, but I want that warning out there right away.

I've gone through 5 different banned/challenged books lists, and I wanted to share with you my favorite books on these lists and why I think everyone should read them.

I want to start with WHO creates the banned book lists and what it is. The banned or challenged book list is a list of books that are not allowed within a school district, and sometimes, when pushed hard enough, public libraries. It is meant to limit access to materials deemed "explicit in nature." It's not made by the government. It's parents and average people create these lists and typically threaten schools if they teach from them or offer these books to kids in libraries. I fully believe and support parents having the right to ease their kids into adult topics, but challenging your kid is the point of school.

I did notice there's common themes in the books on these lists

Race and race theory is discussed in the books

Mental health is discussed in the books

Body autonomy is discussed

The women's rights movement, LGBTQ+ movement, BLM, or any other minority movement it discussed

The book is critical of the government or religion

The book discusses war and the toll it plays

Slavery is ACTUALLY discussed

The book contains sexual content (consensual or nonconsensual)

The book questions society norms

Magic (Yes. Magic)

This list is updated almost weekly in some school districts, and 99% of the time, it is not to remove a book. It is to add one.

A few of these I won't discuss in as much detail in fear I will risk a community guidelines report, but I wanted to discuss some of them and why I love them.

Always keep in mind that you alone are responsible for your reading intake, and check your triggers on all the books mentioned. I will be posting my personal feelings on which age I feel the books are appropriate for as well. I also have not read a few of these in a bit, so hopefully, I have everything as accurate as possible!

If the ✨️ emoji is by the book, it's one of my personal favorites. Like, I may have multiple covers and editions favorite, or it is a book I frequently think about, or it holds a special place in my heart. Without further ado, I present to you Elizabeth's 21 favorite banned books in no particular order:

Maus by Art Spiegelman - banned for discussions of violence, torture, and death- This is a comic book/graphic novel series based on the author's father, who was a Polish Jew and is a survivor of the Holocaust. It is gut-wrenching. It is disgusting. It is heartbreaking. I do not recommend it for anyone under 16, but I personally think it's okay to be uncomfortable and learn from the past.

✨️Animal Farm by George Orwell - banned for open criticism of the government - I LOVE Animal Farm. Animal Farm is based on the Russian government/monarchy being overthrown (which is why it surprises me that it is banned in so many districts in the US.) In summary, animals over throw their human masters and create a society of their own. It is meant to challenge and discuss the fact that no matter how small a person is, the revolutionary mindset is a powerful one. I highly recommend Animal Farm to 16+.

✨️Beloved by Toni Morrison (get used to her name. You'll see it one more time. I could make a post solely on her.) -banned for violence, SA, realisitic depictions of segregation and slavery - Beloved is about the treatment of black women in the south during and after slavery, and how things circled for them. This book has haunted me since I read it at 15. I'm 27 now. Toni is a superb writer who truly pulls at your heart with her stories. I do not feel this book should be banned. What happened in the United States needs to be discussed openly to work on the racial divide. Please consider reading this if you haven't, and if you have siblings 16+, let them read it as well and have an open discussion with them on how it made them feel. This is one I also recommend checking triggers for.

Burned by Ellen Hopkins (you'll see this name several times, too. I'm shocked her name isn't plastered as the first thing on every list honestly) - banned for questioning religion and parental figures - I also love Ellen Hopkins. I have paid to listen to her lecture several times. I love the way she writes. I love her willingness to challenge society. I love her openly discussing hard topics. This book is one of those topics. It is about a young group of kids sent to what my brain thinks is a religious reformation camp in Nevada. They are supposed to be finding salvation and redemption in Christ, but instead find love and acceptance in each other. There's a few heavy topics (the whole book is heavy. Her books, in general, can be heavy). I'd recommend it to anyone 14+.

Call of the Wild by Jack London - if you're my age and grew up in the American School system, take all the time you need to process the fact that this book is on all 5 of the lists I looked at- banned for animal cruelty and violence - this was required reading when I was in school. I was 12. It is focused on the Klondike Gold Rush, and arguments could be made that it is more based on the treatment of animals at that time. I do not feel I should have been exposed to this at the tender age of 12, but I tend to carry more sympathy towards animals than I do people. I feel safe saying 15+ with discussions being had regularly.

✨️ Fahrenheit 451 by Ray Bradbury - banned for challenging the government and violence - I have chills as I am getting ready to write about this book, tears are welling up, this is my coming of age novel. It is one of the books I read by choice in high school that actually began my question everything and look at all angles mindset. I can not recommend this book enough. It is about book and media censorship and a dystopia based society where common practice is to burn books, a real thing that has happened in so many countries, on government orders in order to keep the general population conformed and uneducated. It discusses the consequences of that on society and humanity, it discusses the dangers of rebellion against that mind set, and I could not put it down. 15+. Please please please read this book if you never have. Especially as an adult who can recognize the behaviors discussed in the book and how it parallels modern society

For Whom the Bell Tolls by Ernst Hemmingway - banned for discussions of war - this book graphically discusses the consequences of war. I am not overly comfortable getting too far into it. I will say, this one will shatter you if you are an immeserive reader who gets so into a book it becomes your surroundings and reality instead of just a pleasure reader. Please read with caution. 17+

Lord of the Flies by William Golding - banned for violence and language (I personally think there's more reasons and those two are the scapegoats) - again, if you are my age, take the time to process your shock. This book centers around children who survive a plane crash on an island and are forced to create their own society and government, and it quickly goes to hell in a hand basket. Everything from sex, to racism, to discrimination against disabilities (does it sound familiar yet) is discussed and challenged by the groups formed in this book. 15+ with supportive discussions

Of Mice and Men by John Steinbeck - another one for people my age to go "wait what" to - banned for "depressing themes" and "antibusiness" - this book discusses the tragic lives of two migrant works and the conditions they were forced to endure. It's main lesson is about humanity and compassion. This is a really educational book that I feel should be in classrooms. 14+

Tricks by Ellen Hopkins - banned for SA and sexual nature - this one I would not recommend to anyone under 17. It is about teens trapped in sex work. Please check your own triggers before reading this.

✨️The Crank Triology by Ellen Hopkins (Crank, Glass, and Fallout) - banned for open discussion of drug use and addiction - these novels are actually based on the life of the author's daughter and her downwards spiral into m3th addiction. They are heartbreaking (fallout will hit you HARD if you have friends who are the kids of an addict or you are a child of a parent who is an addict). They were the first books I read by her, and I am sad to say I live in a community where they were banned hard enough that it passed to all three school districts and the public library. 16+ and please check triggers

Hold your breath, my loves. ✨️A Court Of Mist and Fury by Sarah J Maas -banned for sexual content, violence (domestic and situational), and ✨️magic use✨️ - if someone can explain to me why this is the only book from this series I've found on a banned/challenged list and why NONE of the Throne of Glass books are on them, I'm all ears. Do I think your 13 year old should be reading this? F no. A 16 year old, though? Yes. Let them have that Rhys Crease in those paperbacks. I'd rather my kid read smut than watch it. Also, kudos and congrats to SJM for being a banned author in 12 school districts, thus making her one of the top bans for the 2022-2024 school years. There's some great authors and novels on this list. It was pretty cool to get to include her.

✨️The Bluest Eyes by Toni Morrison - banned for race theory, racism, abuse - oof. This one is hard. Be ready to cry if you read it. It takes place after the Great Depression in the US and is mainly about a young black girl. It centers a created inferiority complex she developed because, due to societal norms regarding beauty, She does not see beauty in herself and her skin. Definitely 14+. Definitely should be read in classrooms as it is one of the most powerful books I've read that centered on black women and their voices that need to be heard.

✨️ Milk and Honey by Rupi Kaur - banned for sexuality and representing the feminist movement - this one is quite frankly insulting. This is a poetry novella about healing and finding power inside of yourself as a female and finding your self-worth. It's banned in 10 districts, making it part of the top 10 bans. I might actually cry over this one being banned. My daughter will read it 14, and we're going to discuss it. I think it is that worthy and powerful. I will leave you with my favorite quote from this one "I am not a hotel room. I am home. I am not the whiskey you want. I am the water you need. Don't come here with expectations and try to make a vacation out of me."

✨️ The Catcher in The Rye by JD Salinger - banned for teen rebellion - this is the first book I gave to my younger brother that I thought would resonate with him, he still has that torn up, creased, and notated copy that was passed from my mother to our big brother, then to me, and now to him. He told our parents once he's pretty sure it saved his life. This book centers around 16 year old Holden after he is expelled from school. He begins to challenge adults and societal norms regarding children. It critiques a superficial society and brings to light the consequences of some choices we make. Teens can relate to this book. My siblings and I all did. This book has sat on a pretty much national ban list for far too long. It needs to be brought into classrooms, especially classrooms in schools with behaviorally challenged teens who've never found a book that speaks to their soul and feelings. 16+ with guidance and open discussion.

✨️I Know Why the Caged Birds Sing by Maya Angelou - banned for "bitterness and hatred toward white people" in the majority of the state Texas - break my heart harder, Maya. This is the only autobiography on I have on my tops list at the moment. It focuses on young Maya Angelou and the discrimination and racism she faced. There is so much symbolism and history to dive into with this book. Have tissues ready if you read this. 16+

The Kite Runner by Khaled Hosseini - banned for open discussion of war and violence - another oof. This is another book I handed to my little brother and said, "Read this and get back to me." It was not one of my personal favorites until he sat me down and told me how the book made him feel. I genuinely wish I could have him typing this one out, but he's off doing his adventures and seeing the world. It is a beautiful coming of age novel set in the Middle East during the invasion of Soviet Russia to the United States and the downfall of the Taliban. It centers around the importance of paternal figures, friendship, and key relationships. 15+ there is a SA scene that is rarely mentioned on the banned books list so keep that in mind.

✨️The Lovely Bones by Alice Sebold - banned for discussions of childhood SA, pedophilia, and murder - one of my top 10 favorite books of all time. If you've watched the movie, please read the book. It is about a family struggling after their daughter is SA'd and killed by a serial predator, and it is told from the daughter's perspective in the afterlife and from the eyes of her family. You will go on a roller-coaster of emotions. Anger, sadness, joy. I really do love this book. I have a hardcopy for display purposes, and a paperback with a separate note book filled with notes, quotes, etc. 16+ just due to the heavy nature of it, but for a mature reader and personality 14+

✨️I want to scream from the rooftops on how bullshit this one is. To Kill a Mockingbird by Harper Lee - banned for open discussion of segregation, racism, violence, and "general hatred towards white people - this book should be required reading. This book openly discusses consequences of false accusations based on race, it discusses the mistreatment of minorities, and it discusses a white superiority complex. It needs to be read and discussed, and I will die on that hill. 14+

This one also makes me want to scream✨️The Great Gatsby by F. Scott Fitzgerald - banned for violence, alcohol promotion, anti business beliefs- this book is a classic and it brings to question a lot regarding income levels, old and new money, and financial segregation. It has beautiful symbolism that you have to be paying attention to catch, and is so much more than a Leonardo Dicaprio movie. 14+

It is with a heavy sigh and heart I introduce the next author: ✨️JRR Tolkien✨️ if I would have just listed his books, it'd be this whole list - banned for violence and ✨️magic use✨️ - these novels and short stories are the back bone of the modern day fantasy writer and have even created countless table top RP games. The fact that so many Middle Earth based novels are banned is almost a stab in the back to the idea that schools are supposed to push and celebrate growth, individuality, and knowledge. I have the Lord of the Rings and the books that prequel it on a pedestal. They are my comfort novels and go tos when I'm feeling down and truly want to lose myself into a well-done and built world. I recommend them to anyone who already loves Fantasy or wants to get into fantasy 15+

EDITED TO ADD ✨️Slaughterhouse Five by Kurt Vonnegut - there's a lot of reasons this book is now banned, and I was just informed by my best friend she saw it had hit an official list - If you want science fiction mixed with anti war look no further. This book addresses a very deadly and tragic bombing in ww2 using a narrative from a character who is "stuck there" over and over again. Please really check triggers for this one. It's easily another 16+ book.

Theres a few books I came across on these lists I haven't read yet, but currently have in my cart to purchase. Do any of you have a favorite banned book? Are you interested in any of these books? If you are and have questions, please shoot me a message or comment. I'm always happy to discuss banned books. They're my favorites. 💜

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

i like my mentor teacher and i'm learning so many things! and i especially like her classroom management strategy of NO BRIBES! but i'm angry at how social studies and science have been reduced in most k-5 classrooms and it like actually enrages me. for my entire elem experience, we had daily social studies and science instruction. if not in kindergarten, i know for a fact it was daily at least in first and beyond. DAILY. now it's been reduced to a 45 min block called "content" that teachers may or may not get to. i don't love standardized testing but tbh getting rid of the tests meant teachers and districts as a whole ditched science and social studies! it's crazy to me because research has shown time and time again that children's literacy suffers when they don't have the necessary background knowledge about the world AND the achievement gap widens when students don't get regular social studies instruction! and today we did a read aloud on the history of the us flag and one out of the only two black students raised his hands and asked if african americans were enslaved during the revolutionary war. (this school is 90% white.) and my mt responded yes, slavery did not end until later, and that we'd talk more about black history in FEBRUARY. i'm like actually really frustrated...black history shouldn't wait until february. in my classroom next year i'm injecting as much social studies as i can. and in my lessons here i might ask to do some social studies because this is a disgrace. i literally had a better social studies education in my rural elementary school even if it was problematic in a lot of its teaching. what????

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

SUMMER - 1988 - JAMES KENDALL

My name is James Kendall, most people call me Jim, and I was born in Meade County, Kentucky on August 2, 1940. I have one brother that is three years younger. My family has lived in this section of Kentucky since the Revolutionary War. With travel being restricted in this area until after the nineteen hundreds, I am kin in some manner to most people in my county.

I have been married three times and have what is now popularly called an extended family. Children, stepchildren, grandchildren of all ages, children younger than their nieces and nephews, instead of an extended family it should be called a nightmare for a genealogist. Perhaps I should not complain too loudly, that may be what keeps me young in thought.

I enjoy travel, the new places and people that you can meet. Somewhere out there just might be the most beautiful scene or the most delightful person that you may ever meet. It would be a shame for that to never happen. Some of the most interesting people that I have ever seen are the very young and the extremely old, the young still have not had their imagination suppressed and the old are extremely versed in the experience of what will work in life.

My mother had a positive influence on my education, she had only an eighth grade schooling, and felt that for me and my brother to amount to anything, we should have a good education. I think that to some of my relatives, it is still debatable whether it succeeded or not in my case. I have attended Kentucky Wesleyan College in Owensboro, Kentucky and the University of Louisville in Louisville, Kentucky.

Some of my earliest memories are of my mother reading stories to me of places that were so very different from the way that we lived. I could read at the age of three and I feel that my mother reading to me and her encouragement was responsible for my reading at such an early age. I started to school much younger than most children. When I was six, the age that most children start to school, I was in the third grade.

Literature has been an important aspect of my life. I enjoy any form of well written fiction. I have written short stories and poetry every since I was a young child but my writing never had the polish and professionalism that I wanted it to have. I had a creative writing course in college, but the only thing that I felt that I got from it was that people do not talk in perfect English and form that school teaches.

I am interested in any form of new technology. Computers and satellite receiver equipment are two areas that I am involved in. I have some very strong feelings about these two forms of communication being the soap box in the park for the twentieth century and any effort to stifle these forms of communication is a dart spot on our Constitution. With interests in these areas, naturally science fiction would be one of my favorite forms of reading. Two of my favorite authors are Robert A Heinlein and L. Ron Hubbard. I think that Battlefield Earth by Hubbard is one of the most interesting and powerfully written science fiction books that I have ever read.

Another author that I greatly admire is a native of Kentucky, Jessie Stewart. I feel that his writings of his beloved state has helped people in other areas understand the people of Kentucky. To me he has a very descriptive method that paints a picture of his characters, as clearly as an oil painting by a master artist. He is perhaps the one author that I would like to be able to duplicate in style. When I finish this course, if I could write with one tenth the clarity that Jessie Stewart did, I would be satisfied.

There are so many stories and tales in my mind that are waiting to be written, that at times I feel that they rule my life. I don’t feel that it would be a justice to the stories to write them in a form that would not be the best of my abilities.

Perhaps it is as Jessie Stewart once said of short stories, “in the future, short stories will be only for yourself and your family. There will not be a market for the general public”. If this were to be so, I still would like for my stories to be as well polished and professional as it possible for me to create.

I would like to be able to stir the emotions in people who would read my stories, if something that I write is funny, make them happy, if it is sad, make them cry, or any of the emotions between the two I would like to be able to have my writing read and like I said about Jessie Stewart, be able to say that I had painted a portrait with words. I live in a very beautiful valley in the country and sometimes early in the morning the day breaks with such beauty that you can almost smell and taste the day come alive. I would like to be able to convey that taste and smell into written word. This has not been an easy task for me. Of all of the things that I know and write about, Jim Kendall is on the bottom of the list

-written by James "Jim" Kendall

summer of 1988

0 notes

Note

Growing up in a socially progressive environment: How has this affected your feelings about success? Were you taught that forming a nuclear family played a role in that measurement? Or were you taught to value yourself strictly in terms of stuff like grades and academic achievements? Or maybe that whole talk was geared towards personal happiness, in whatever form it took for you?

Also, at school: did you have to do stuff like the pledge of allegiance? Was Columbus Day and history class transparent or did your teachers omit the fucked up parts?

--

The closest my mother ever came to advice about a nuclear family was: "Find a boyfriend after college. Roommates are awful."

(Though from what she said, this belief stemmed from being the one clueless white girl in an apartment with three black girls becoming politically conscious in 1970s Chicago. I'm pretty sure Mom was the annoying roommate in that scenario, so...)

She really didn't discuss success. I never asked, but I assume that this was a conscious choice the same as she never once mentioned my looks either positively or negatively. (I asked her about the latter, and she said it's something she'd decided on before having me.)

I've spent the last couple of years carting hundreds of pounds of books out of the house. Among them was a massive collection of child development books from the 70s through 90s. A lot of them were on topics like raising intellectuals rather than just kids who get good grades or fostering a sense of self worth and emotional self sufficiency.

My mom was an educator, and she disliked a lot of the status-obsessed ways people deform their children's senses of self. Grades = worth is not a message she'd ever have espoused, though she did send me to hard schools and expect me to do my work. She could be a school snob as much as anyone, but she didn't explicitly talk about success in those terms. I think a big part of it is that all of her friends from when she was young were intellectuals who wanted to be professors, found there were no jobs, and ended up as carpenters or in the Peace Corps or all kinds of other random things. My mother herself started a PhD in... epidemiology...? (Something sciencey anyway.) She bombed out when her much older sister died unexpectedly and ran off to Kathmandu to hang out with an old high school friend who was studying Tibetan Buddhist religious logic.

She was certainly concerned with me finding meaningful work and being self sufficient, but she just didn't talk in terms of "success".

And more than that, worth as a human is inherent. It has nothing to do with success. If you want to raise a strong person, you give a kid unconditional love, clear boundaries, and a sense of stability. You teach them that all humans are valid and worthwhile just because. They don't have to do anything to gain that. It just is.

Perhaps that's not how you meant "success", but I've seen far too many otherwise intelligent parents mutilate their children's ability to learn by treating education and knowledge as the source of value in the world and not as something pleasurable in their own right.

Perhaps happiness = success is closest to what my mother would have espoused, but really, being a valid human being is a separate axis from being happy or successful or any other particular measure of a life well lived.

--

None of my schools would have been caught dead making us say the pledge of allegiance. They were all hippie private schools. We did shit like learn to sing This Land is Your Land.

We spent a lot of time on Indigenous history—though still in a "That was long ago" kind of way that made me assume everyone was dead and gone. Genocide was mentioned often. Columbus was mentioned rarely, and not in positive terms.

I still wouldn't say it was particularly well-rounded history. I'd rather have learned more about the Mexican-American war and less about the utterly irrelevant snoozeville that is the American Revolutionary War. Frankly, as a Californian, I would reduce the Revolutionary war to "It happened" and our equally boring Civil War to the politically important parts that it was indeed fought over slavery as Southerners themselves said at the time, that all that noble lost cause shit is just a retcon by white supremacists, and anybody who repeats it in the modern day can fuck themselves.

We did have pretty good stuff on Harriet Tubman in second grade and lots on Japanese internment later. Some of the schools I went to were better than others, usually because they were less beholden to stuffing our heads with irrelevant garbage that's on major history tests. I could have done with slightly fewer traumatizing documentaries on the Holocaust though.

--

As for my personal feelings about success, towards the end of my 30s, I was looking around for what should come next. I decided to finally write a novel, and I feel a lot better about my 40s having done so. I wasn't desperate or self hating like a lot of people I see around me fearing aging, but I did feel a lack of accomplishment in a sense.

My next goal... well, my immediate next goal is to finish book 2 of my series, but in the longer term, my goal is to not just finish writing things but to become financially successful as a writer.

50 notes

·

View notes

Text

“That a certain segment of the internet would be so hungry for even a fleeting glimpse of Malick is not surprising. The director is as famous for his closely guarded privacy as his output. He has not given an on-the-record interview in nearly four decades. From 1978, when Paramount released Malick’s second film, the Panhandle-set Days of Heaven, until 1998, when his World War II epic, The Thin Red Line, premiered, Malick more or less vanished. Rumors circulated around Hollywood that he was living in a garage, that he was teaching philosophy at the Sorbonne, that he was working as a hairdresser. Even as he returned to filmmaking, was nominated for Oscars, won the Cannes Film Festival’s Palm d’Or, and doubled down on his experimental style (cinephiles will never stop debating his decision to punctuate a fifties Texas family drama with CGI dinosaurs in The Tree of Life), Malick continued to maintain his silence.

(…)

Malick was born in Illinois in 1943 and spent his boyhood mostly in Waco and Bartlesville, Oklahoma, the eldest of three brothers. His mother, Irene, was a homemaker who had grown up on a farm near Chicago; his father, Emil, was the son of Assyrian Christians from Urmia, in what is now modern-day Iran, and staked out a career as an executive with the Phillips Petroleum Company. Emil was aggressively accomplished, a multi-patent-holding geologist who played professional-level church organ and served as a choir director, and he pushed the young Malick to succeed on all fronts from an early age. (A Waco Tribune-Herald news brief from 1952 noted that “eight-year-old Terry” had “surprised his classmates at Lake Waco Elementary School by presenting a 43-page paper on planets.”) But Emil could be a stern taskmaster, and he and Malick often butted heads. “They had some conflicts over the years,” Jim Lynch, a close friend of Malick’s since high school, told me. “That’s one reason Terry came to St. Stephen’s.”

St. Stephen’s is known as the Hill, both for its steep topography and its aspiration to be an enlightened beacon (as in the biblical “city on a hill”), and Malick thrived in a culture that emphasized spirituality, intellectualism, and rugged individualism. “When I first got there, it was made known that he was the local genius,” Lynch told me. Malick had the highest standing in the class his junior and senior years, served in student leadership positions like dorm council, played forward on the basketball team, and, with Romberg, co-captained the football team, playing both offensive and defensive tackle, an accomplishment of which he’s still proud. (“He says that in football he was ‘the sixty-minute man,’ ” Linklater told me. “Ecky says that the only time he boasts is when he talks about his high school athletic prowess.”)

None of Malick’s peers—or, it would seem, Malick—had any inkling that he would stake out a career as a filmmaker, but he was already exploring many of the ideas that would animate his work. Students at St. Stephen’s went to chapel twice a day, and the spiritual education there was both rigorous and open-minded, with The Catcher in the Rye taught alongside more traditional religious texts in the school’s Christian ethics class. “It was religious in a broad humanities sense,” Lynch said, a conception that Malick embraced. “Terry doesn’t like anything sectarian or dogmatic,” Lynch added. “His grounding is more in a philosophical sense of wonder.”

(…)

After Harvard and a Rhodes Scholarship at Oxford University, Malick began experimenting with more-white-collar careers. He worked for a short time as a globe-trotting magazine journalist, interviewing Haitian dictator “Papa Doc” Duvalier and spending four months in Bolivia reporting for the New Yorker on the trial of the French philosopher Régis Debray, who had been accused of supporting Che Guevara and his Marxist revolutionary forces. (Malick never completed the piece.) Then there was a year as a philosophy lecturer at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, during which Malick concluded that he “didn’t have the sort of edge” required to be a good teacher. And finally, he moved to Hollywood, where he studied at the American Film Institute and quickly became an in-demand screenwriter, working on an early version of Dirty Harry, writing the script for the forgotten Paul Newman–Lee Marvin western Pocket Money, and making powerful friends like Bonnie and Clyde director Arthur Penn and AFI founder George Stevens Jr.

But Malick wanted to make his own film, and he found a story he wanted to tell in the late-fifties murder spree of Charles Starkweather. Though Malick had never directed a feature, he insisted on total freedom and had few qualms about scrapping the production schedule when he became inspired to shoot a different scene or location, exasperating many in the crew. But when Badlands, starring Martin Sheen and Sissy Spacek, opened at the New York Film Festival in 1973, Malick became an instant sensation. The New York Times critic Vincent Canby called it a “cool, sometimes brilliant, always ferociously American film” and wrote that the 29-year-old Malick had “immense talent.” (The Times also reported that getting Malick to talk about Badlands was “about as easy as getting Garbo to gab.”)

Soon, Malick began production on his follow-up, Days of Heaven, a tragic love story starring Richard Gere, Sam Shepard, and Brooke Adams set in the North Texas wheat fields where Malick had worked after high school. Badlands hadn’t been an easy shoot, but on Days of Heaven, Malick’s unorthodox approach had the crew on the brink of mutiny, and when the film finally came out, in 1978, the reviews were decidedly mixed, sometimes within the same review. “It is full of elegant and striking photography; and it is an intolerably artsy, artificial film,” wrote Harold C. Schonberg in the New York Times.

Days of Heaven won an Academy Award for best cinematography, and it is now widely regarded as a masterpiece. (Roger Ebert, delighting in the stunning magic-hour photography and the poetic tone, would judge it “one of the most beautiful films ever made.”) But the experience of making the film had been so grueling for Malick that, according to Badlands producer Ed Pressman, “he just didn’t want to direct anymore.” The year after Days of Heaven premiered, Malick abandoned production on his next project, a wildly ambitious movie called Qasida that he’d hoped would tell the story of the evolution of Earth and the cosmos, and informed friends and colleagues that he was relocating full-time to Paris.

(…)

There is only one publicly available recording of Malick’s voice. Around halfway through Badlands, he makes the single on-screen cameo of his career, engaging in a brief, tense exchange with Kit Carruthers, the Charles Starkweather–like killer played by Martin Sheen. Malick speaks in a slow, soft, higher-pitched drawl. He is unfailingly polite, a little retiring, and warm without being chummy. Malick has one of those voices that lends itself to imitation—broad and regional and distinctive—and when I spoke with his friends and colleagues, I heard several versions of it. They all sounded like the Malick we see in Badlands.

Malick’s friends describe him as a generous and humble man with a capacious intellect and a child’s insatiable curiosity. He likes going deep on birding, cosmological events, and the interconnectedness of the natural world. (“You’ll be talking to him about butterflies in the Barton Creek watershed, and then he’ll start talking about the soil and all the soil insects,” said filmmaker Laura Dunn.) He enjoys discussing the fundamental questions that drive religious and philosophical inquiry and has a deep knowledge of the Bible. (Lynch remembers that after seeing Mel Gibson’s The Passion of the Christ, Malick—a fluent French speaker, with conversational German and Spanish—mentioned that he understood the film’s spoken Aramaic, because he’d grown up hearing it from his paternal grandparents.) And yet, as in high school, Malick can be just as down-to-earth as high-minded. He’ll show up for lunch at an unfussy cafe wearing a bright Hawaiian shirt and talk about football or gush about pop-culture schlock like the genetically-modified-shark movie Deep Blue Sea or drop a quote from Ben Stiller’s Zoolander. (After hearing that Malick was a fan, Stiller made an in-character happy-birthday video for the director.)

(…)

Malick is even more buttoned-up about his work. He politely shrugs off compliments about his films—which, in the old Hollywood style, he calls “pictures”—seemingly agonizing over flaws, missed opportunities, and bad memories of the production. “I’ll mention something like, ‘Hey, I heard there were some seventy-millimeter prints of Days of Heaven. And he’ll say, ‘Oh, gosh, when that opened, I was out of the country,’ ” Linklater said. “I think talking about his work takes him back emotionally.”

Laura Dunn, whom Malick recruited to direct The Unforeseen, a documentary about Austin’s development boom and the pollution of Barton Springs, told me that Malick finds it difficult to watch movies from start to finish. “He’s the kind of artist who seems almost tormented by his need to keep working on something,” she said. “If he’s sitting in a dark room, watching a movie all the way through, he’s restless because he’ll still be editing one of his own movies, or he’ll think about all the things he did that he regrets and wants to go back and change.”

(…)

Malick takes years to finish his films, hiring teams of editors to put together different cuts, and finding and discarding entire story lines during the post-production process. In the final cut of The Tree of Life, Malick resolves the drama at the center of the film by having his young protagonist’s family move away from his boyhood home. There’s a bittersweet sense of a chapter closing and an uncertain future lying ahead. But in an earlier, unreleased version of the film, the story of the protagonist, Jack, ends not with his family’s departure from Waco but on a more triumphant note: he arrives as a boarding student at St. Stephen’s. It doesn’t take a deep familiarity with Malick’s life story to see the parallels between the family in the film and Malick’s own. Jack bridles under the discipline of his stern, accomplished, and ultimately loving father. He worships his angelic mother. He and his two younger brothers turn to each other for support. The film is framed around the premature death of the middle brother. (Malick’s brother Larry took his own life as a young man.)

(…)

Malick’s silence has always seemed, in part, a way to resist such a reading. When Lynch mentioned to Malick that he saw the director’s last three features—The Tree of Life, To the Wonder, and Knight of Cups—as an “autobiographical trilogy,” Malick took umbrage. “He didn’t like me labeling them that way,” Lynch said. “He didn’t want people thinking that he was just making movies about himself. He was making movies about broader issues.” Malick might very well say the same of Song to Song, but nevertheless, it’s tempting to see his latest work as an extension of that discarded Tree of Life ending—the aging director offering a raucous love letter to the city that offered him inspiration as a boy and has sustained him ever since.”

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

muse

name: Alexander Kozachenko

nickname(s): Sasha, Buddy

age: verse dependent

race/nationality: Caucasian, Eastern European

place of birth: Holigrad, Eastern Slav Republic

gender: cis male

sexuality: demisexual

occupation: teacher (English, Math), former revolutionary

height: 190cm - (6 ft 3 in)

hair: dark brown

eyes: hazel

laterality: right-handed

~spoilers for Resident Evil: Damnation below.~

bio: Born and raised in Holigrad, today’s capital of the Eastern Slav Republic, Sasha always felt that he grew up as a child should: sheltered, surrounded by friends and loved ones, free to chase his dreams and ambitions under the watchful eye of a loving mother.

All things considered and even with the weight of an absent father hanging over him at times, his childhood was a happy one. Not least of all because of his two lifelong friends, JD and Irina, both of which did their part of keeping him hale and whole throughout.

It was true that they went along with most of his reckless ideas when they came to him. He had been a wild child. Easily excited, with sheer endless energy and a sense of adventure instilled in him by stories his mother read to him from as early as he can remember. More than once did their little group of friends butt heads with other kids. Sasha having been easy to anger back then, too. A weakness of his that persevered way into his adult years, only ever eased by Irina who always knew how to temper his anger when needed, and JD who lightened his mood when he lost himself to brooding after yet another squabble lost.

If asked today why he eventually chose the road that led him to teaching, he would be embarrassed to admit that in essence it had been Irina to push him towards it, telling him she was certain he would make a great teacher. And him, at the time already quite smitten with her, easily followed where she went, grateful for every hour spent studying together, for every minute spent talking about the years to come.

In the end, the story went as it always does: they fell in love, were happy, made plans for a joined future even before Sasha worked up the courage to ask Irina for her hand in marriage...

Sasha’s life was what people would call normal, maybe he’d even count as happier than some. Up until the day tragedy struck and in one fell swoop derailed his entire life and squashed any dreams of a future.

Unrest had been sown among his countrymen for years, even decades now. A civil war raged among the people, two parties grappling for power. The ruling class and the resistance. Rich against poor, an age old song that left nothing but blood and tears in its wake.

Sasha hadn’t been blind nor deaf to the state of his hometown, of his country, and yet the attack to the school during the middle of the day blindsided everyone, although he would go on to blame himself for years to come. He should have known. Should have done something --anything-- against the accusations voiced that the school housed a resistance cell, which in turn ultimately lead to the justification of an attack against civilians, against children. So many lives were lost that day, including Irina’s, leaving Sasha standing among the burned ruins of what was once his life.

Grief and anger no longer able to be held back by the soothing touch or kind words of his lover manifested themselves into the wish - no - the need for revenge, leaving him aching for what he perceived as justice, carving out a dark hollow place deep inside himself that left a grim and reckless determination to set things right.

He had never held a gun before joining the resistance under the guidance of a member of the Council of Elders, but he had always been a quick study. A natural they called him, but it was empty praise to him. Nothing mattered anymore other than ending the war with the resistance as the victor. His comrades said he fought like a man possessed, in awe of someone burning so brightly for their cause, not afraid to die in the line of duty.

Sometimes he wonders if he wasn’t simply tired of living.

He went through the motions for the longest time after joining the ranks. Killed when necessary, followed orders without question, but never without remorse. He still has nightmares about all the lives he took during that time, no matter how much he reasoned with himself that it had been for the right cause, for freedom at the time.

It was easier in the beginning, with the anger still fresh in his mind, but the longer the fight went on and the further the memory of his fiancée drifted into the past, the harder it got to justify his actions, and the more hopeless he felt. In the end, the conviction that he believed to be inherent to himself turned into a crutch, something to hide behind, to cling to, because if he wasn’t Buddy, the soldier, he was still Sasha, the man who lost everything.

Of course, fate has a weird way of pushing one onto a different path and so it happened that shortly after the resistance got their hands on the means to control what they called B.O.W.s an American government agent stumbled into his path just as the civil war came to a head in the capital.

Today, Sasha wouldn’t be able to recount all that led to him facing down enemies alongside the man who’s throat he had put a knife to upon first meeting him. The entire battle a haze of pain and rage and fear after he allowed the Plaga into his body and until this moment he can still not understand the motivations that had Leon Kennedy save his life not once, but multiple times throughout them making what he assument to be their last stand at the time.

It must have been pure adrenaline what kept him going throughout he thinks, that and the Plaga, the dominant species of a biochemically engineered parasite used to control the other B.O.W.s and it is also this which he blames for his spotty memory of the events.

But even so, he’ll never remember anything more clearly than the moment he tried to take his own life after the dust settled, fear of turning into one of those monsters running rampant in his mind, only to be stopped by Leon, the man staring him down with such conviction that even when he pointed a gun at him to rid him of the parasite that had attached itself to his spinal chord he felt overwhelming relief overshadow the gutwrenching anguish over knowing what was to come: pain, agony even and then more loss, the loss of his legs, maybe even more, he couldn’t know, but something in Leon’s eyes told him that he’d live..

That is my answer. And your answer.

5 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hi! Do you have any Cherik Army AUs? I've managed to find just 3.

Hi Anon, thanks for the ask. I found some good Army AUs, though some might not quite fall into the category of 'Army AU'. There are, surprisingly, few Army AUs that I have found, whereas there are several military and war AUs, but those don't necessarily involve an army. I did include a variety that involve an army in one way or another, though some fit the bill better than others. I hope you find some that you enjoy!!

Cherik Army AU

I Want to Guard Your Dreams And Visions – luninosity

Summary: I was reading Barbara Hambly’s Abigail Adams mystery novels, and then Erik/Charles American Revolutionary War AU happened. Little snippet in which they share a tent, drink coffee, and provide support to each other.

The Eggnog Riot – Sophia_Bee

Summary: 1826. The American Military Academy in West Point. The day after Christmas. Cadet Erik Lehnsherr wakes up naked with a certain cadet Xavier sprawled across his chest. He can only blame the eggnog.

No Man’s Land – ikeracity

Summary: It's 1914 in Ypres, Belgium. British soldier Charles Xavier has been in the trenches for four months of endless artillery fire, bone-deep cold, and constant fear of the enemy. But on Christmas Eve, the gunfire falls silent, and they climb out of their trenches for a Christmas truce. Charles, of course, meets Erik, the German soldier across the way.

My Land’s Only Borders Lie Around My Heart – pseudoneems

Summary: WW1 Christmas truce of 1914. Opposing soldiers Erik and Charles meet.

Le soldat – Iggyassou

Summary: Erik is in the trenches, trying to survive the war so that he can go back to Charles, his young lover waiting for him back at home.

Names – Squeegee

Summary: In the summer of 1917, British soldier Charles Xavier finds himself taking cover in a shell crater.

Not sure if the 'graphic' tag applies or not, but I'd rather be safe than sorry.

Quell a storm with pen and ink – patroclux

Summary: Charles had spared his life. That was not something he could easily repay.

They wrote letters to each other for two years, until Charles was pulled out of the war from a sudden illness and Erik remained to fight for a cause he didn't believe in. One that ultimately had no effect; one that stole away four years of his life.

Traumatized and persecuted, Erik applied for a post at Janus, a lighthouse in the middle of the Irish Sea. He thought being alone would do him good.

Despite the letters and despite the love, Erik didn't expect Charles to find him.

Hier steh ich an den Marken meiner Tage – MonstrousRegiment

Summary: Erik Lehnsherr is a spy in the SS, and his British liaison is strategist Charles Xavier. Their relationship from the moment they meet to a year after the end of the war.

Theme and Variations: War – ninemoons42

Summary: Erik Lehnsherr is a musical prodigy and a man destined for great things and great stages. But his life is shattered by a terrible accident that leaves him blind and trying to find his way back to his life, his music, and his place in the world.

Then he meets Charles Xavier, an agent of Section 8 of the Military Intelligence Directorate of Providence, and he finds himself listening in to clandestine radio transmissions and clicking Morse code, and these sounds are part and parcel of a war that can only take place in the shadows and the hidden places of history.

Strib nicht von Mir – ravenoftheninerealms

Summary: A squad of Allied Forces, led by Charles Xavier, liberates the Nazi concentration camp where Erik was being held prisoner.

Cold foxholes, warm hearts – oddegg

Summary: Basically, this is Band of Mutants. A little slice of life in Bastogne.

Photographs and Memories – tirsynni

Summary: When war-battered Erik Lehnsherr met Charles Xavier, the man kneeling in the dirt and whispering to a lost refugee child, Erik feared his days of running from his deviance was done.

Marching Home – Quietbang

Summary: For a prompt on the meme asking for fic dealing with the fact that, in comics canon, Charles served in the Korean war.

War meant something different to this generation, Charles knew.

Crash on the Levy (Down in the Flood) – Quietbang

Summary: “This is much bigger than you think. You're in the middle of a war, and you don't even realize, do you?”

He pauses, and answers his own question.“No, of course you don't. How silly of me."

The Knight and the Dagger – Dow

Summary: A Lieutenant in the Soviet Army, Erik Lensherr had no other goals than to find the man that killed his parents. But when a discovery yields a little boy with wings like an angel, Erik is shocked to realize that he isn’t alone. There are other people like him, both dangerous and alluring.

Lifelong Service – Pookaseraph

Summary: Erik thinks he should be the one to teach their recruits hand-to-hand combat; Charles makes a persuasive argument to the contrary.

Footsteps of uprooted lovers – ninemoons42

Summary: Against a turbulent backdrop of artistic, social, and political upheaval, the playwright Charles Xavier and the photographer Erik Lehnsherr find themselves meeting under less-than-polite circumstances, but part rather more amicably than they'd met.

When they find each other again in a Barcelona that is falling inexorably toward war, they find themselves taking up arms, each in his own way, and together they join a struggle for freedom, for love, and for their very lives.

Dear Soldier – Lindstrom, ToriTC198

Summary: "Dear Soldier,

I pray that this package finds you well. The organization gave us a list of odds and ends that you might need, but I thought that a person so far from home might appreciate something more than soap and tube socks."

When Charles' school decides to send care packages to the soldiers fighting in Vietnam, he chooses to also include a letter and a few personal touches. When Staff Sergeant Erik is the recipient of that particular care package it will spur a relationship that will change them both.

Fortunate Son – blueink13

Summary: he days leading up to and during Alex's deployment in Vietnam. Everyone handles it in their own way. Some handle better than others.

You’re Here – Deshonana

Summary: Everyone decides its a good idea not to tell Erik when his boyfriend comes home from the military.

Welcome Home – loveydoveyecstasy

Summary: It's been two years since Charles was deployed to Afghanistan, and Erik can't wait to pick him up at the airport.

When Secrets have Secrets – ximeria

Summary: The arguments that take place in General Xavier's office when General Lehnsherr has a bad day are legendary. Quite frankly, no one really knows what's going on and if the two men have it their way, no one ever will.

Quiet Company – Sophia_Bee

Summary: Erik Lehnsherr is always on the move. He's spent the last many years going from war torn country to war torn country telling the stories of the people there through photographs. Then one of his pictures is selected as a winner for the Pulitzer Prize and Erik finds himself stuck in London for longer than he wants. He ends up with an assignment to photograph Charles Xavier, a wealthy philanthropist who is intrigued to find himself working with a Pulitzer-winning war photographer. Erik is far less intrigued by someone he considers privileged and out of touch. Both of their lives are about to change in ways they couldn't imagine.

The City is Ours – RedStockings

Summary: Erik felt his heart racing with excitement, lightened, and for once felt joyful. Charles had looked at him, really looked at him, and there had been something there, a knowing of a kind. As the soldiers laughed amongst each other, and joked each other about who would succeed in marrying the boy, Erik made himself a silent vow. Charles was going to be his, and nothing would keep him from having him. He’d marry him, and he’d save him, and Charles would love him for it.

Not even the war could keep them apart... right?

Sign of the Times – dsrobertson

Summary: Casablanca-ish AU.

Charles Xavier meets Erik Lehnsherr in Paris, 1937. They spend the next two years with one another, stupid in-love, until war comes heavy in September 1939. Erik leaves for Poland and the Resistance movement there, promising to return. Charles is left in Paris, where Nazi jackboots march in, Summer of 1940. He becomes a member of the underground French Resistance, publishing illegal newsletters, leaflets, until news comes through in February 1942: Erik is dead. Charles throws himself into more dangerous work, meeting with Communists, helping derail a German train, and he does too much, goes too far. His friends find him safe passage out of France, out across the Mediterranean, to Morocco, Casablanca. It is here he finds Erik, alive.

The Waste Land – nekosmuse

Summary: The White Queen and her Shadow King sit on their throne, safe behind the psionic shields of the Walled City. The armies of Genosha batter uselessly at the gates, a war locked in stalemate. Magneto, camped in the frozen mud, receives word the Citadel intends to send a telepath to the front lines. The same telepath he met two years ago, who sat across a carved wooden chess set and offered Magneto the first friendly smile in a lifetime. The same telepath who still haunts his dreams.

Winter Comes With a Knife – RedStockings

Summary: It apparently came to no one’s surprise that the war-mage Erik Lehnsherr took up residence in the Dark Keep. I knew he was going to choose my sister, Raven, to be his apprentice so why wouldn’t he let me go? What did he want from me?

My name is Charles Xavier, I can read minds and use magic. I’ve met Kings and Queens, mages and magic users. I’ve travelled through lay-lines and jumped through the Dark Void… but none of that really matters.

I am leading an army into war, I am scared and I never wanted this. I’ve come to realise that what I want, rode into my life when I was still a child. Now he’s out there, ready to charge into battle. Ready to die for me.

Polaris – LastAmericanMermaid

Summary: Charles Xavier is 19 years old, doe-eyed and soft; Erik Lehnsherr is 24 years old, steely-hard and bitter. One is a soldier, the other a refugee. Both are mutants. There will be pain, oh yes.

(An AU in which Charles is a wounded British soldier, Erik is the German hiding in France who nurses him back to health, and the contents of this fic are best read to the soundtrack of Atonement.)

Note: Unfinished

MEDIC! – paladin_danse

Summary: A British airborne medic finds himself alone and afraid behind enemy lines. When he decides to save the life of an S.S. German officer he finds wounded in the snow, he has no idea the choice he has made will alter the course of the war—and their lives—forever.

Note: Sadly unfinished

Suicide is Painlesss – weethreequarter

Summary: Erik Lehnsherr did not become a doctor to pick bullets out of children. Unfortunately the US Army had other ideas.

Stuck in the middle of the Korean War, Erik and his fellow civilian surgeons have to battle not only the war, but also weather, mud, and boredom. And that's without mentioning Major Sebastian Shaw who thinks war is the best thing that's ever happened to him and never should've been allowed to pick up a scalpel, or Colonel William Stryker who may or may not work for the CIA and probably doesn't even know himself.

Throw in new arrival Captain Charles Xavier, and Erik is in for a very interesting war.

Note: Unfinished

A Light That Never Goes Out – R_Cookie

Summary: It was meant to be the war to end all wars; these two men were never supposed to meet. One a German Jew, the other a British surgeon. The odds that their paths should cross were next to none - but War defies the expected. It always has, and always will.

From the beaches of Dunkirk to the treacherous slopes of Monte Cassino - this is their story.

WWII AU.

Note: Unfinished

82 notes

·

View notes

Text

• U.S Army Nurse Corps

The United States Army Nurse Corps (AN or ANC) was formally established by the U.S. Congress in 1901. 96% of the 670,000 wounded soldiers and sailors who made it to a field hospital staffed by nurses and doctors survived their injuries. By the end of the war, the Army and Army Air Forces (AAF) had 54,000 nurses and the Navy 11,000—all women.

Nurses served in Washington's Army during the Revolutionary War. Although the women who tended the sick and wounded during the Revolutionary War were not nurses as known in the modern sense, they blazed the trail for later generations when, in 1873, civilian hospitals in America began operating recognized schools of nursing. Professionalization was a dominant theme during the Progressive Era, because it valued expertise and hierarchy over ad-hoc volunteering in the name of civic duty. The Army Nurse Corps became a permanent corps of the Medical Department under the Army Reorganization Act (31 Stat. 753) on February 2nd, 1901. Nurses were appointed in the Regular Army for a three-year period, although nurses were not actually commissioned as officers in the Regular Army until forty-six years later-on in April 1947. The number of nurses on active duty hovered around 100 in the years after the creation of the corps, with the two largest groups serving at the general hospital at the Presidio in San Francisco and at the First Reserve hospital in Manila. In World War I (American participation from 1917–18) the military recruited 20,000 registered nurses (all women) for military and navy duty in 58 military hospitals; they helped staff 47 ambulance companies that operated on the Western Front. More than 10,000 served overseas, while 5,400 nurses enrolled in the Army's new School of Nursing.