#they live in Ohio and in a new yorker

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

@rainbowroadonsteroids

staying close w people long distance really is about the mundane stuff. i get texts like "made quesadillas" "spilled mop water all over the floor :(" "lady on the bus has not one not two but three tiny dogs in her purse" andits like wow. i love you more than words can express

#moth and me core#they live in Ohio and in a new yorker#so we have all kinds of crazy shit to share when we text#mel/moth✨#comet rambles#putting in queue to deploy later

169K notes

·

View notes

Text

Thinking about Peter and Wade on a totallynotadateitsjustlunchpaldontgettooexcited date (they have those often) and wondering just how much "Aye im walkin' ere!" Rubs off on Wade.

Wade is about as New yorker as Ohions are from Ohio. This being said he's the FIRST to say that this place is shit and that we should tear it all down and start again except not with a flood, with lava (cause if we're in church* The flood aint gonna do no good, just like aunt tams tuna cassarole. That'll have ya on the toilet from cock's call to cy-yote howl**) and try again.

*If were being honest here **5 am to 5 am literally all day.

This is peters city. Born and raised. This is also Wade's city. Not born or raised but damn it New York is his and he so judges people for what bodegas they stop at and what kind of pizza they like/ how they eat it.

Wade: Why are you pattin' your pie?

Peter, patting some of the grease off his slice: You ever swing around the big apple with diarrhea? Not fun

Wade: I guess not. I still can't believe you got basil.

Peter: Look pal, I love it here and I wanna live long enough to see it.

Wade, folding his pizza and taking a bite: I don't.

Peter, folding his pizza too: I know you don't. It's why you eat all that grease.

Logan, because he's here too: He's going to complain later about his stomach hurting

Peter, staring, insulted as he watches Logan cut his pizza with his claws:....

Wade:...What the fuck are you doing?

Logan: what?

Peter: I cant believe you did that.

Wade: Im so sorry. Hes so embaressing. Look gramps, You don't cut up your pizza, 'kay? Now throw that garbage to the dog and ill get ya another.

Puppins: 😋

Logan, eating the now cut up pieces: I like it.

Puppins: 😞

Wade, putting a hand on peters shoulder: Im so sorry you had to see that. I don't know whats gotten into him lately.

Peter: I don't risk my life for this city just for someone to do this

Wade: *pats him*: I know I know.

Logan: Im not eating my pizza like a taco. That defeats the purpose. If you wanted a taco you should have gotten one.

Wade: You aren't invited to my spiderman themed birthday party if you're just going to keep embarrassing me.

Logan: *eyeroll* you guys are so drimatic.

#sassy ADULT spiderman my beloved#spideypool#poolverine#old man logan LMAO#new york pizza#mary puppins#peter parker#spiderman#the amazing spider man#deadpool and wolverine#logan howlett#deadpool#wade wilson#deadpool 3#wolverine#how do you like your pizza?#sliced or folded?#pizza pie#pizza!!!#deadclaws

101 notes

·

View notes

Text

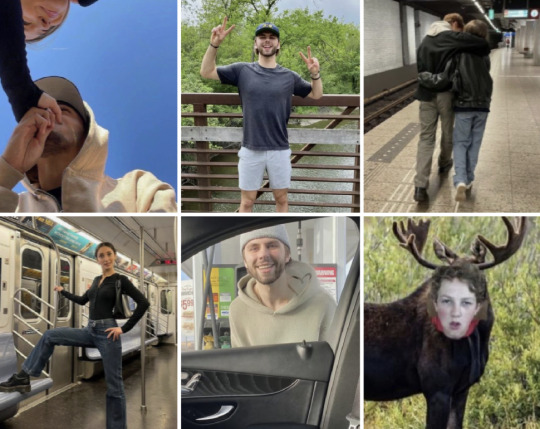

my new york girl | adam fantilli

a fantilli x oc !

@tinafromny: new yorker in ohio part 1/?

4.5k likes, 209 comments.

|| @lhughes_06: im a meme...?

@tinafromny: yes sir u are 🦅

@edwards.73: am I a babygirl ?

@tinafromny: ew gross

@dylanduke25: the last one 🥺

@tinafromny: ik the carhartt .. so American

@adamfantilli: loml

@tinafromny: babygirl

@edwards.74: TINA

@tinafromny: ETHAN

@childrenoftheyost: we'll we get a tina from NY sighting soon?

@tinafromny: yknow it! have to see baby luca 🙈

@luca.fantilli: im not the baby...

@tinafromny: when you can grow a beard better than a...snap me

@luca.fantill: ADAM

@adamfantilli: ?

@gavin.brindley: baby luca 🫶🏻

@tina'sbff: Tina in ohio pt 1/1 u can never leave me again

@tinafromny: ummmmmmmm

@tina'sbff: she has a flight booked already i presume @adamfantilli

@adamfantilli: 🙃🙃

@parsonsny: Tina from ny is serving in the first and third 😌

@tinafromny: love y'all to jupitar and back !

@dylanduke25: did you have fun tho?

@tinefromny: its Ohio dyl...you cant possibly have fun in that state

@tylerduke: RUDE-- youre uninvited to the lake this summer

@alyssa_duke: wait but I like her??

@tinafromny: hi guys I went back (:

7.8k likes, 455 comments.

||

@lhughes_06: why everytime i come here i am abused

@tinafromny: because ur u and im me

@tinafromny: also ur an easy target

@dylanduke25: she said what she said

@gavin.brindley: the 4th is giving

@adamfantilli: its giving 'im running on 0 coffee this morning'

@Nolan_moyle: MOOSE

@seamscasey26: MOOSEY

@mackie.samo: he's passenger princess?

@tinafromny: yes bc he scares me when driving...as do all Canadians driving in this god for saken country

@tina'sbff: thats the new yorker in ya

@tinafromny: in the most brooklyn accent

@adamfantilli: passenger princess for life🥺

@lianabarzal: need u back in ny and get ur cute butt to long island

@tinafromny: omg babe yes -- im comin!

@adamfantilli: come back

@tinafromyny: I promise soon bubs

@nickblankenburg: pls do...he looks like a sad and wet puppy

@rutgetmcgroarty: the michigan hat...come back soon adam 🥺

@adamfantilli: soon!

@johnnyorlando: he's just ... ken (?) and youre barbie

@tinafromny: yeah and thats why he's not allowed inside my apt

@tina'sbff: he would moja doja house it so badly...

@tinafromny: we've already have enough rats in NY we don't need one inside

@adamfantili: blocking u rn

@luca.fantilli: ur a rat ada

@tinafromny: my rat ;)

@adamfantilli: love me some ny

87.9k likes, 1.2k comments.

||

@tinafromny: oh woah -- a hard launch?

@adamfantilli: ofc

@tinafromny: i feel so seen

@adamfantilli: anything for my love

@luca.fantilli: did you seriously have to steal my bestie ?

@adamfantilli: did you have to steal my girl????

@tinafromny: omg

@tinafromny: guys guys i can be two places at once !

@edwards.74: time travelor!!!!

@tinafromny: nah im just an avid ft user

@johnnyorlando: and insta liver

@tinafromny: yeah...because u won't let adam give me your # so buh bye orlando

@johnnyorlando: I have good reasons

@adamfantilli: take this to the live pls

@johnnyorlando: they grow up so fast 😢

@Luca.fantill: ur crying? im crying

@tinafromny: can confirm

@tina'sbff: ur alright canadian dude

@adamfantilli: ur alright too pigeon

@tinafromny: LONG LIVE MY PIGEON

─── ⋆⋅☆⋅⋆ ──

hope you all enjoyed! please like and reblog if you did !!!

🤍🤍🤍🤍

Tags: @jayda12 @cuttergauthier @slafgoalskybaby

#adam fantilli#adam fantilli x oc#adam fantilli blurb#adam fantilli imagine#adam fantilli fic#michigan hockey#luca fantilli#ethan edwards#gavin brindley#johnny orlando

78 notes

·

View notes

Text

what has sam sunspeared been up to in real life

if you're seeing this post and you're like "shit I remember her, she fell off the face of the tunglr," yes I sure did and here's a short life summary for the last 5 years

fuck it we ball let's get a PhD in biology in our 30's why not. they are letting me touch big microscope. this is the only detail I will give

(got into my dream Ivy and then promptly gave it up for an equally prestigious and even more wealthy state school in a cute town where I'm having a good time)

(I mean in a very real sense I'm straight up having a bad time. but I have many friends and a very supportive program; I'd say 90% of it is great.)

(how is the health insurance?" thank you for asking. it fucks most severely)

is it impostor syndrome if you immediately reframe it as "I am the greatest con artist who has ever walked this sinful earth"

living in the midwest is wild. the grocery stores here are hot ass and no one knows how to cross the street, which is to say no one crosses the street like an asshole, as is their god-given right as a pedestrian.

as a(n upstate) new yorker I love two learn about all these provincial little state rivalries. ohio isn't a real state

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

One of the first voices millions of commuting New Yorkers hear each morning is the measured tone of former traffic reporter Bernie Wagenblast reminding them to stand away from the platform edge. Wagenblast, AKA “the voice of New York”, reminds AirTrain passengers at JFK or Newark that the doors are closing, and hosts a podcast about infrastructure, including episodes on Ohio’s bridges and wildlife crossings in Oregon. But that […] voice, honed by years of practice to impart clarity and authority but not alarm, is changing. Earlier this year, Wagenblast, 66, went on the radio to present herself publicly as a transgender woman, and has this month been participating in US Pride celebrations with gusto, including the march at Asbury Park on the Jersey shore. Wagenblast is still Bernie, but that’s now derived from Bernadette. […] She has had support from the people she knows, even casually. The reception from her friends from Catholic university has been similarly supportive, and she’s working with her high school classmates for their 50th reunion without issue. “It’s wonderful,” she says. “Times have changed.” Hateful comments have only come from people who do not know her, she says. Her relationships with female associates, she says, have also benefited from her public presentation. “They’re comfortable and accept me and it’s been one of the great pleasures.” […] One of the side-effects of a public transition is, she hopes, to give encouragement to those who are still not out. Each time somebody in the subway station hears her voice, she says, they will know that LGBTQ people are part of everyday life. “We’re not just on TV or people you read about that are somewhere else but an intricate part of day-to-day living. I think that can be very powerful.”

#wait i'm. so happy wtf#like. i'm so glad for her that she's been able to come out and have a good time of it#and also just like. really warm fuzzy feeling at like. trans guardian angel voice#really really love that for me/us/nyc <3

81 notes

·

View notes

Text

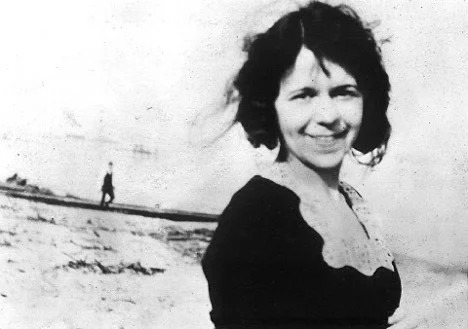

Since that post about Martha Gellhorn is popular here's a post about another writer who is more interesting than Hemingway.

Dawn Powell on the beach, circa 1914.

Tim Page, the Estate of Dawn Powell

This is the third story in The Unmarked Graveyard: Stories from Hart Island series from Radio Diaries. You can listen to the next installment on All Things Considered next Monday, and read and listen to previous stories in the series here.

Dawn Powell infiltrated the writing world by hanging out in bars and taverns around New York's Greenwich Village in the 1920s, rubbing shoulders with the likes of Ernest Hemingway and Edmund Wilson.

"She came from nowhere, she was no one," writer Fran Lebowitz told Radio Diaries.

But Powell had a voice. She had style. And she rose from obscurity by turning her gaze on the city of New York itself and its cast of characters. Over the coming decades, Powell wrote novels, diaries and more than a dozen plays — earning her renown, and even a National Book Award nomination.

Then, in 1965, she died. What happened next didn't go according to script.

A voice lost to the world

Powell had been clear in her will: she wanted her body to be donated to the Weill Cornell Medical Center for research. Yet five years after her death, when Cornell asked her executor, Jacqueline Rice, what to do with her remains, Rice left the decision up to the center.

So, unbeknownst to her family and friends, Powell was buried on New York's Hart Island — America's largest public cemetery. Then, all of her work went out of print.

A generational talent of New York was buried in its heart, but lost to the world and those who knew her.

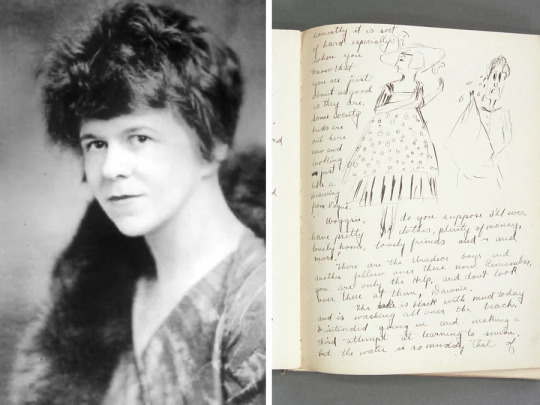

Powell circa 1930, and an entry in her diary circa 1914.

Tim Page, the Estate of Dawn Powell

Hart Island, located off the coast of the Bronx, has no headstones and no plaques. It's often seen as a place for those who went unrecognized in their lifetime — not for well-known writers.

Powell had been writing stories since she was a child. Growing up in Ohio, she endured considerable emotional abuse from her stepmother and often used writing as an escape. In 1918, she left Ohio for New York City, with dreams of being a writer.

"She knew that she was smart enough, good enough to be very good in New York, which is the most competitive place in the world," Lebowitz said.

Powell's humble beginnings in the bars of Greenwich Village turned into a career. In the coming years, she wrote witty pieces on New York life for magazines like The New Yorker and Esquire. Her career picked up steam when she began writing novels about New York: satirical, risque fiction about people who'd come to the city from a small town and indulged in its joys and vices. Her most well known novels include A Time to Be Born (1942) and The Wicked Pavilion (1954).

"She was a very smart, tough, sarcastic, woman who put all of that into her books," said Tim Page, a critic and author of Dawn Powell: A Biography. "She made fun of millionaires and communists. She basically thought human beings were silly and frivolous, but she loved them."

Powell's writing reflected her personal life. Her characters were often young people who ached for success and recognition, but rarely got it. Though her work was in the public eye (her last novel, The Golden Spur, was a finalist for the 1963 National Book Award), she did not reach the level of fame of other writers, male or female, in her era.

"Some critics thought she was mean," Page said. "All the very famous women writers were usually ending their stories with a man and a woman falling in love and living happily thereafter. Dawn had seen enough of life to realize, well, sometimes that's the case but it's not what usually happens in the world."

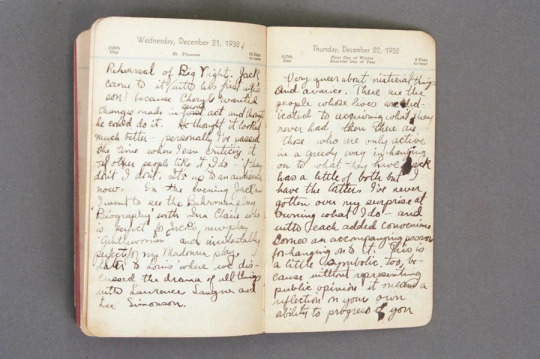

Powell's diary, December 1932.

Tim Page, the Estate of Dawn Powell

Powell struggled with money for much of her life. She and her husband, Joseph Gousha, had a disabled son who needed costly medical care. By the end of her life, she also needed medical care of her own. She developed intestinal cancer, which led to her death.

While her will was specific about her body going to the Weill Cornell Medical Center, it didn't specify what to do with her body after its donation. In addition to being Powell's general executor, Jacqueline Rice was also her literary co-executor, largely responsible for her literary estate. When her client died, Rice simply stopped responding to inquiries from publishers and filmmakers. It was some time before Rice told Powell's family about where she had ended up.

Years later, Powell's great-niece Vicki Johnson was told by her mother about the burial on Hart Island, also known as a Potter's Field.

"My mom told me it was a Potter's Field, and it was just a place where people are buried who didn't have any money or no family to take care of them," Johnson said. "My grandparents would have certainly found a better resting place for her than where she was buried."

The effort to bring Powell's work back

Powell isn't the only well-known person buried on Hart Island. There's former child actor Bobby Driscoll, who starred in some of the most iconic Disney films of the time, like Treasure Island and Peter Pan — and even won a Juvenile Oscar by the age of 13.

Driscol fell into a pattern of substance abuse and run-ins with the law in his teenage years, ranging from drug smuggling to assault. He was found dead in his Greenwich Village apartment at 31. When no one claimed his body, he ended up on Hart Island.

The cemetery is also home to Rachel Humphreys — the muse and lover to Lou Reed, and the inspiration for several songs on his album Coney Island Baby. Though her official cause of death remains unknown, Humphreys died at the age of 37 at St. Clare's hospital, known for housing AIDS patients. Hers was among the many bodies sent to Hart Island during the AIDS epidemic.

Johnson and others insist Powell wouldn't have minded being buried at Hart Island.

"I think she'd be a little amused by the fact that she's buried with a Disney star and a rock and roller," Page said. "She loved New York. She told the truth about New York and I'm not sure she'd want to be anywhere else."

Dawn Powell circa late 1940s, early 1950s.

Tim Page, the Estate of Dawn Powell

Though Powell's descendants have chosen not to remove her body from Hart Island, there has been a considerable effort to unbury her work. In 1987, her writer and friend, Gore Vidal, published an article in The New York Review of Books, praising Powell as one of American literature's lost greats. The article ignited interest in Powell in the writing world.

Steerforth Press also published a volume of Powell's diaries, edited by Page, in 1998. The Library of America put nine of her novels back in print in 2001.

These days, Powell has gained a cult-like following. Celebrities like Julia Roberts and Anjelica Huston have tried turning her books into films, and she's gotten a shout-out on the TV show Gilmore Girls.

"There will come a time when people will realize that she's one of America's greatest writers," Page said.

This story was produced by Mycah Hazel of Radio Diaries. It was edited by Deborah George, Ben Shapiro and Joe Richman. Thanks also to Nellie Gilles, Alissa Escarce, and Lena Engelstein of Radio Diaries.

This story is the third in a series called The Unmarked Graveyard: Stories from Hart Island. You can find other stories from Hart Island on the Radio Diaries Podcast.

#Dawn Powell#Women writers#Unmarked Graveyard: Stories from Hart Island#Radio Diaries#1920s#Greenwich Village#Weill Cornell Medical Center#Out of print books#Books by women#A Time to Be Born (1942)#The Wicked Pavillion (1954)#Books about women#Dawn Powell: A Biography by Tim Page#The Golden Spur

33 notes

·

View notes

Text

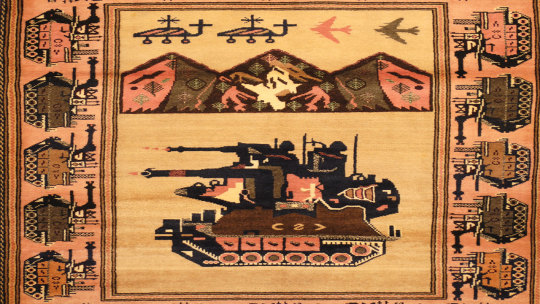

Attorney Mark Gold has an oriental rug in his western Massachusetts home that most people call “nice-looking” until he tells them to inspect it more closely. Then they’re enthralled, because this is no run-of-the-mill textile—it’s what is called an Afghan war rug, and what it depicts is somber and stunning: cleverly mixed with age-old botanical and geometric designs are tanks, hand grenades and helicopters. “It’s a beautiful piece in its own right,” says Gold, “but I also think telling a cultural story in that traditional medium is fascinating.”

The cultural story Gold’s rug tells is only the beginning. Since the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan in 1979, the country’s war rugs have featured not only images of the instruments of war, but also maps detailing the Soviet defeat and, more recently, depictions of the World Trade Center attacks.

It was women from Afghanistan’s Baluchi culture who, soon after the arrival of the Soviets, began to weave the violence they encountered in their daily lives into sturdy, knotted pile wool rugs that had previously featured peaceful, ordinary symbols, such as flowers and birds. The first of these rugs were much like Gold’s, in that the aggressive imagery was rather hidden. In those early years, brokers and merchants refused to buy war rugs with overt designs for fear they would put off buyers. But with time and with the rugs’ increasing popularity, the images became so prominent that one can even distinguish particular guns, such as AK-47s, Kalashnikov rifles, and automatic pistols.

A decade later, the Soviets withdrew from Afghanistan, and rugs celebrating their exodus appeared. Typical imagery includes a large map with Soviet tanks leaving from the north. These rugs, principally woven by women of the Turkman culture, often include red or yellow hues and are peppered with large weapons, military vehicles and English phrases such as “Hand Bom [Bomb],” “Rooket [Rocket]” and “Made in Afghanistan.”

To many, this script is a firm indication of the rugs’ intended audience: Westerners, and in particular, Americans, who funded the Afghan resistance—the Mujahadeen—during the Soviet occupation. “The rugs are geared for a tourist market,” says Margaret Mills, a folklorist at Ohio State University who has conducted research in Afghanistan since 1974. “And they verbally address this market.” Sediq Omar, a rug merchant from Herat who dealt in war rugs during and after the Soviet occupation, agrees. “Afghanis don’t want to buy these,” he says. “They’re expensive for them. It’s the Westerners who are interested.”

While this may be true, it’s likely that the first “hidden” war rugs from the early 1980s were meant for fellow Afghanis, according to Hanifa Tokhi, an Afghan immigrant who fled Kabul after the Soviet invasion and now lives in northern California. “Later on, they made it commercialized when they found out that people were interested,” she says. “But at the beginning, it was to show their hatred of the invasion. I know the Afghan people, and this was their way to fight.”

Kevin Sudeith, a New York City artist, sells war rugs online and in local flea markets for prices ranging from $60 to $25,000. He includes the World Trade Center rugs in his market displays, and finds that many passersby are disturbed by them and read them as a glorification of the event. “Plus, New Yorkers have had our share of 9/11 stuff,” he says. “We all don’t need to be reminded of it.” Gold, a state away in Massachusetts, concurs. “I appreciate their storytelling aspect,” he says. “But I’m not there yet. It’s not something I’d want to put out.”

Yet others find World Trade Center rugs collectable. According to Omar, American servicemen and women frequently buy them in Afghanistan, and Afghani rug traders even get special permits to sell them at military bases. Some New Yorkers find them fit for display, too. “You might think it’s a ghoulish thing to own, but I look upon it in a different way,” says Barbara Jakobson, a trustee at Manhattan’s Museum of Modern Art and a longtime art collector. “It’s a kind of history painting. Battles have always been depicted in art.” Jakobson placed hers in a small hallway in her brownstone.

In an intriguing twist, it turns out the World Trade Center rugs portray imagery taken from U.S. propaganda leaflets dropped from the air by the thousands to explain to Afghanis the reason for the 2001 American invasion. “They saw these,” says Jakobson, “and they were extremely adept at translating them into new forms.” And Nigel Lendon, one of the leading scholars on Afghan war rugs, noted in a recent exhibition catalog that war rug depictions—both from the Soviet and post-9/11 era—can be “understood as a mirror of the West’s own representations of itself.”

If Afghanis are showing how Americans view themselves via World Trade Center war rugs, Americans also project their views of Afghan culture onto these textiles. In particular, the idea of the oppressed Muslim woman comes up again and again when Americans are asked to consider the rugs. “Women in that part of the world have a limited ability to speak out,” says Barry O’Connell, a Washington D.C.-based oriental rug enthusiast. “These rugs may be their only chance to gain a voice in their adult life.” Columbia University anthropology professor Lila Abu-Lughod takes issue with this view in a post-9/11 article “Do Muslim Women Really Need Saving?” She notes the importance of challenging such generalizations, which she sees as “reinforcing a sense of superiority in Westerners.”

Whether in agreement with Abu-Lughod or O’Connell, most conclude that the women who weave Afghan war rugs have a tough job. “It’s very hard work,” says Omar. “Weavers experience loss of eyesight and back pain—and it’s the dealers who get the money.”

But as long as there’s a market, war rugs will continue to be produced. And in the U.S., this compelling textile certainly has its fans. “These rugs continue to amaze me,” says dealer Sudeith. When I get a beautiful one, I get a lot of pleasure out of it.” And Gold, who owns five war rugs in addition to the hidden one he points out to visitors, simply says, “They’re on our floors. And we appreciate them underfoot.”

Mimi Kirk is an editor and writer in Washington, D.C. {read]

#smithsonian#article#USSR#propaganda#war#russian imperialism#us imperialism#imperialism#rugs#art#craft#21st century#20th century#Afghanistan

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Mask Bans Insult Disabled People, Endanger Our Health, and Threaten Our Ability to Protest

As a high-risk disabled person who depends on others to keep me safe, I have written about the importance of masking, and I advocate for mask mandates in health care settings. But those individual efforts seem futile against the onslaught of proposed mask bans that would contribute to the spread of COVID and other illnesses, while also pushing high-risk people out of public spaces and protests, violating their right to assemble under the First Amendment.

[...]

Today, the mask is the unsightly marker of deviant individuals: the sick, the immunocompromised, the disabled, and the protester who wishes to keep their identity anonymous. (Many demonstrators at pro-Palestine marches have worn medical masks or other face coverings, both to protect their identity from authorities and to protect their health in large crowds.) We’re told such masked individuals threaten the moral order of society, and these bans are meant to keep the public “safe.”

[...]

Across the country, protests on college campuses have shaken leaders who are unsure how to handle such a groundswell of activism. Leaders in some states took the opportunity to go after student mask use, as in Ohio, where the Republican attorney general threatened on-campus protesters with an obscure anti-mask law. Now, with Democratic officials in California and New York also exploring mask bans, we're reminded that ableism is a bipartisan project. Any mask ban is a dangerous prospect, as many regions are currently dealing with an increase in COVID cases, and these patterns are expected to continue multiple times a year. (Days after Los Angeles’s Democratic mayor Karen Bass said the city would look into a potential mask ban at protests, she contracted COVID.) A mask ban on the subway would endanger a public good that many people depend on — and have a right to — and the ability of high-risk people to participate in society, to be seen, and matter to the broader community. Mask bans are a labor issue, as well. A resident of New York City, who asked to remain anonymous to protect their privacy, says, “I wear a mask and encourage others to do so because, prior to COVID, masks were a common form of PPE for indoor and outdoor airborne hazards at work.… The criminalization of masks is a criminalization of workers protecting ourselves…." The resident continues, "Governor Hochul and Mayor Adams supporting attempts to ban masks are the latest examples of New York State Democrats trying to destroy the lives of poor and working-class New Yorkers.”

[...]

What is clear to me is that disabled people have never felt safe. Many of us view masking as a form of solidarity with workers, activists, and people of color all over the world fighting fascism and genocide. But mask bans send the message that it is a crime to be disabled. I think of people who have fought hard to stay relatively safe since early 2020, those who hang on a precipice that feels like it could fall at any moment. Some days I wonder what my breaking point will be.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

New York Dating Chronicles: Donald

I moved to New York nine months ago now and what a trip it has been.

I decided quickly after my arrival that I wanted to be someone different here (as all faux-New Yorkers, transplants are we’re called, do) and thought long and hard about what that version of myself looked like. I needed to know what she liked, disliked, dressed like, sounded like, acted like, how she treated people, how she treated herself, and so on & so forth. It wasn’t going to be easy, so I turned to the resource that I always sought out whenever I had big life changes to make – other people. I decided for the entire year of 2024 I would go on one date a week. The line of thinking was that maybe I’d be able to find myself in others.

Now there were some rules with this little experiment. The rules are as follows:

At least one date a week and all dates must be tracked in the New York Dating Spreadsheet

Your roommate and/or best friend must always have your location, the date’s full name, and plan for the evening

You can count one person as three separate dates on the spreadsheet, but anything after that is just dating

It’s more about the number and less about the timeframe – so, as long as you get 4 dates in one month, it doesn’t matter the consistency in which you have them. (meaning if you have 4 dates in 1 week, you’re set for the month in the same way you would be if you only did 1 date a week for 4 weeks)

I’ve decided every worthy experiment deserves to be properly documented. Thus begins my New York Dating Chronicles, this little blog right here. I’ll keep you updated on every date, person, and experience I encounter. And who knows? Maybe we’ll both learn something along the way.

Donald, 39, Attorney

I shakingly raise my hand to fix my mess, the red lipstick has spread to my right front tooth. Gently, I smudge the spot as my phone buzzes in my hand, “I’m sorry. We’ve talked about it, and we aren’t comfortable with you going on a date with this grown-ass man without having his last name”. Gabby has been the bravest of us since we all hugged hello for the first time 17 days ago in the NYU dorms. Clicking instantly, our friendship has blossomed into something that will hopefully last a lifetime. This concern is not out of character and quickly snapped me back to the reality that I am, in fact:

In New York City, living with a bunch of strangers

About to go on a date with a 39-year-old man who prefers I refer to him as Daddy at all times

About to go on my 3rd date ever, like in my life

I don’t know said “daddy’s” last name, or any truly identifiable facts about him (I don’t even have a picture of his face) and I’m more afraid of scaring him off than I am of what it might mean for me if I don’t get this information before the date

This reality is jarring, and not for the first time since I crossed the George Washington Bridge in the back of my father’s Kia Sportage, I realize I don’t recognize myself at all. This isn’t the 22-year-old, midwestern girl who left the state of Ohio for the first time a mere two and a half weeks ago.

I glance again in the mirror, red lipstick smeared slightly in the corner of my mouth now and a few too many buttons undone, and feel like I’m six years old again playing dress up in my Grandma Yulie’s closet. My heels slipped as my toes gripped them to my feet, dress pooling as I twirled in the center. Only this time, the giddy faux sophistication is replaced with an empty pit. The comfort of being found and redressed in age-appropriate clothes so far away.

“You’re right.” I reply “Let me see what he says”.

—

The train slaps my hair against my face and it sticks with the sweat this 90-degree day has provided me. I pull the strands away, careful to make sure my red lip is intact, and step onto my very first solo subway ride. “Mortes” his text reads, and so I send this to my new friends. A 10-minute walk to the bar and I have arrived at another of my very firsts, my first date in New York City. He looks next to nothing like his pictures. A few inches shorter, bald, and a full beard now. It’s obvious his pictures were taken at least 7-10 years earlier. He stands up to greet me with a hug, and all I can think about is the sweat still lingering on my skin. Pulling out the bar stool, he tells me he’ll stand (there’s only one seat available). The bartender asks the two girls on the other side of us if they’ll scoot down so that he can have a seat as well, and they do. However, the bartender has now brought their attention to me and the man close to twice my age – their eyes linger.

He’s kind. That is the first thing I notice. He obligatorily compliments my outfit, even though I have my purse tucked in front of me almost like a shield between him and myself. The look he gives me as he compliments me though makes me feel like a sack of meat that he will happily devour. He’s loud. That’s the second thing I noticed. At times, the groups of people around us will notice him when he speaks, and ultimately then the attention is turned to me.

At many points throughout the date, the girls who originally moved seats for us had glanced at me for the 3rd time. Their whispers were apparent and their eyes beaming with amusement. I caught the one on the left’s eyes at one point and for a second there was a question in them. “Are you okay?” I didn’t know how to answer because I…didn’t know. I didn’t even know who I was really, let alone if I was okay. But instead of trying to let her in on this little personal dilemma, I just gave a subtle nod and slight grimace. It would have to do.

Where are you from? What do you like to do? What are your kinks? Hands-on thighs, hands in hair, hands on cheek, hands everywhere. And my personal favorite, “Do you like Disney movies? Do you watch them often? Which is your favorite?”

Quickly this took a turn towards politics. When I expressed my knowledge about the communist manifesto and the Marx book club I started in college, he went quiet for the first time that night. “I’m not a communist or anything” I rushed out, fearful I just lost any opportunity I had to impress him. “I just like some of his ideas and principles more than what we are following now”. This kick-started his chatting back up, he told me about how he disagreed with transwomen competing in sports, “for your benefit, ya know. It only harms women”. “Then let it be a woman’s issue”, I said, finally finding my voice for the only time that night. Jumping from topic to topic, he often quickly found another thing to hear himself talk about. It soon became apparent that whether I was there or not didn’t matter. He was more concerned with getting everything he had to say out. And boy did he have things to say. Eventually, he worked his way to telling me about his wife. Yes, his wife. They are ethically non-monogamous (must say: brace yourself, this is a recurring theme in the coming pages).

I never had the pleasure of learning her name but to this day I worry I will see her out in public and just never know. He once told me, months after our first date, that he talked about me to his wife frequently and she was fascinated by his stories. She wanted to meet me eventually. It was then I truly felt for the first time the shocking pain of being the other woman. But there was something different about this though, I wasn’t even unique enough to be the secret that we kept to ourselves. I was never going to be the illicit affair that he just couldn’t keep his hands off of and had to risk everything for, no. There was no risk, no worries. I was simply there for him to get off to when his wife wasn’t around or he was in the mood for something young and new. There was never any love and there would never be any love. There was no competition, he went home to her every night.

The Aperol spirits soothed my shaking hands and my briefly hurt pride. None of this was recognizable to me at the time, of course. 22-year-old, inexperienced and insecure me didn’t know why there was an empty crater in her chest as she rode the 4 train back to Union Square station that night.

I know now, I was expecting something from him that he would never give me. Not that he couldn’t, just that he didn’t want to.

Swiping into the dorm suite, I can hear laughter on the other side already. Light music is playing and disco lights hit me as I open the door. I’m greeted with a “She’s back!”, a pre-made dirty Shirly, and a take-out box of leftover pasta they got for me at the dinner they went to earlier in the night. The warmth that fills the crater makes me forget about being his second choice because right now, I was their first.

#writeblr#creative writing#writing#dating#newyork#newyorkcity#datinginnewyork#dating in your 20s#dating in 2024#newyorkdatingchronicles#lifeinnewyork#living in new york#dating sucks#onedateaweek#idon'tknowwhatidon'tknow#concerninglyconfusedcherry

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Having lived in so many different states has given me the personality of someone who just did their 23andme and lists every single flag in their bio. People ask me where I’m from and I’ll be like well I’m a first generation New Yorker living in the diaspora but I’m also 12% florida 34% Ohio 10% Virginia 2% Maryland 0.5% Texan and I’ve got a little bit of North Carolina in me because I went there on vacation once. Also I’m Italian but not for any particular reason I just decided that one

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Genuinely though, what is supposed to be the difference between the Sahara and Ohio, aside from Climate? It's not as if the Nile doesn't run through part of the Sahara and thus create a strip of immense agricultural productivity that helped it become a cradle of civilization.

Even MORE similarly, people say "the Mongolian steppes!" As if the vast stretches of emptiness somehow negates the millennia of a gazillion different kingdoms and empires popping up or marching through??

Yes the population density might be low. Yes, there is a lot of big empty of human space because it's massive. The steppes stretch I to meeting the Taklaman-Gobi which is huge. That desert also houses the Tarim river basin. There's a lot of extreme weather in that whole band of land and yet it was the basis of one of the largest empires by landmass in human history. Like. Okay?

Steppes are just a type of grassland. Like to be clear in the US, we call temperate grasslands a prairie if it's in the Americas and a steppe if it's in Asia. They're the same thing. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Temperate_grasslands,_savannas,_and_shrublands https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Great_Plains

The prairie/great plains lands are west of Ohio but yes Nebraska is just like the Mongolian steppes in that they are literally both temperate grasslands.

That's a perfect comparison. Low population density places may not have a ton of contemporary big city human infrastructure in big stretches of land, or "fun things to do," in very concentrated areas but that doesn't mean they aren't full of life or important. It doesn't even necessarily mean there's nothing for people to do, just that I personally don't desire to do those things, and have no experience with that kind of life.

But also yeah if you ever fly across the country (as I have done many times in my life) theres huge huge stretches of land that doesn't have visible cities or towns, and plenty of places where you can see there's clearly farmlands and maybe a town to sustain that, but not something extremely dense. People live there, it's just you have a very different level accessibility to certain lifestyles based on your human environment. You can't live like a New Yorker on a sitcom if you live in the great plains suburbs. Hell you don't even need to fly. Take a road trip. There's going to be hours of seeing almost nothing but highway and nature and neverending flat prairie and billboards.

always blows my mind as a european when people talk about states like “yeah theres nothing in ohio/montana/wyoming/etc” because i look at a map like but. but theyre so big. every state could qualify as its own country what do you mean theres nothing there. and then i ask people from those states and theyre like “yeah theres nothing here” what do you mean theres nothing there!!!

148K notes

·

View notes

Text

Toni Morrison and the Ghosts in the House

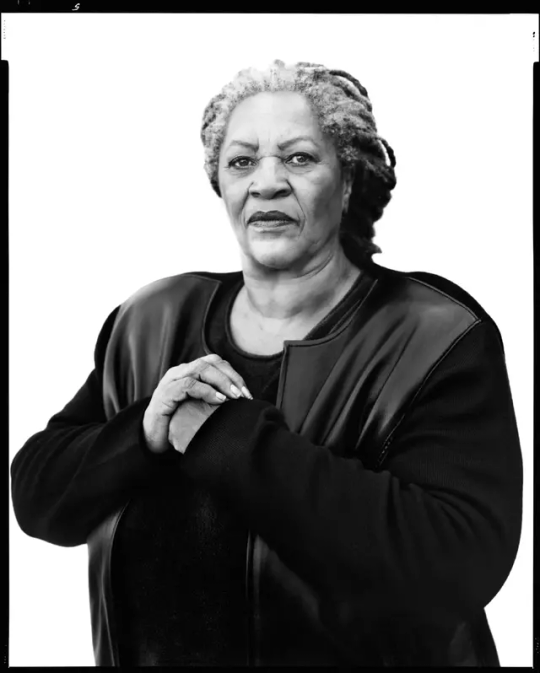

“Being a black woman writer is not a shallow place to write from,” Morrison says. “It doesn’t limit my imagination; it expands it.”Photograph by Richard Avedon for The New Yorker / © The Richard Avedon Foundation

From 2003: As an editor, author, and professor, Morrison has fostered a generation of black writers.

By Hilton Als October 19, 2003

No. 2245 Elyria Avenue in Lorain, Ohio, is a two-story frame house surrounded by look-alikes. Its small front porch is littered with the discards of former tenants: a banged-up bicycle wheel, a plastic patio chair, a garden hose. Most of its windows are boarded up. Behind the house, which is painted lettuce green, there’s a patch of weedy earth and a heap of rusting car parts. Seventy-two years ago, the novelist Toni Morrison was born here, in this small industrial town twenty-five miles west of Cleveland, which most citydwellers would consider “out there.” The air is redolent of nearby Lake Erie and new-mown grass.

From Morrison’s birthplace it’s a couple of miles to Broadway, where there’s a pizzeria, a bar with sagging seats, and a brown building that sells dingy and dilapidated secondhand furniture. This is the building Morrison imagined when she described the house of the doomed Breedlove family in her first novel, “The Bluest Eye”: “There is an abandoned store on the southeast corner of Broadway and Thirty-fifth Street in Lorain, Ohio,” she wrote. “It does not recede into its background of leaden sky, nor harmonize with the gray frame houses and black telephone poles around it. Rather, it foists itself on the eye of the passerby in a manner that is both irritating and melancholy. Visitors who drive to this tiny town wonder why it has not been torn down, while pedestrians, who are residents of the neighborhood, simply look away when they pass it.”

Love and disaster and all the other forms of human incident accumulate in Morrison’s fictional houses. In the boarding house where the heroine of Morrison’s second novel, “Sula,” lives, “there were rooms that had three doors, others that opened on the porch only and were inaccessible from any other part of the house; others that you could get to only by going through somebody’s bedroom.” This is the gothic, dreamlike structure in whose front yard Sula’s mother burns to death, “gesturing and bobbing like a sprung jack-in-the-box,” while Sula stands by watching, “not because she was paralyzed, but because she was interested.”

Morrison’s houses don’t just shelter human dramas; they have dramas of their own. “124 was spiteful,” she writes in the opening lines of “Beloved” (1987). “Full of a baby’s venom. The women in the house knew it and so did the children. For years each put up with the spite in his own way.” Living and dead ghosts ramble through No. 124, chained to a history that claims its inhabitants. At the center of Morrison’s new novel, “Love,” is a deserted seaside hotel—a resort where, in happier times, blacks danced and socialized and swam without any white people complaining that they would contaminate the water—built by Bill Cosey, a legendary black entrepreneur, and haunted by his memory.

Morrison spends about half her time in a converted boathouse that overlooks the Hudson in Rockland County. The boathouse is a long, narrow, blue structure with white trim and large windows. A decade ago, when Morrison was in Princeton, where she teaches, it burned to the ground. Because it was a very cold winter, the water the firefighters used froze several important artifacts, including Morrison’s manuscripts. “But what they can’t save are little things that mean a lot, like your children’s report cards,” she told me, her eyes filling with tears. She shook her head and said, “Let’s not go there.”

We were in the third-floor parlor, furnished with overstuffed chairs covered in crisp gray linen, where we talked over the course of two days last summer. Sun streamed through the windows and a beautiful blue-toned abstract painting by the younger of her two sons, Slade, hung on the wall. As we chatted, Morrison wasn’t in the least distracted by the telephone ringing or the activities of her housekeeper or her secretary. She is known for her powers of concentration. When she is not writing or teaching, she likes to watch “Law & Order” and “Waking the Dead”—crime shows that offer what she described as “mild engagement with a satisfying structure of redemption.” She reads and rereads novels by Ruth Rendell and Martha Grimes.

Morrison had on a white shirt over a black leotard, black trousers, and a pair of high-heeled alligator sandals. Her long silver dreadlocks cascaded down her back and were gathered at the end by a silver clip. When she was mock-amazed by an insight, she flushed. Her light-brown eyes, with their perpetually listening or amused expression, are the eyes of a watcher—and of someone who is used to being watched. But if she is asked a question she doesn’t appreciate, a veil descends over her eyes, discontinuing the conversation. (When I tried to elicit her opinion about the novels of one of her contemporaries, she said, “I hear the movie is fab,” and turned away.) Morrison’s conversation, like her fiction, is conducted in high style. She underlines important points by making showy arabesques with her fingers in the air, and when she is amused she lets out a cry that’s followed by a fusillade of laughter.

“You know, my sister Lois was just here taking care of me,” she said. “I had a cataract removed in one eye. Suddenly, the world was so bright. And I looked at myself in the mirror and wondered, Who is that woman? When did she get to be that age? My doctor said, ‘You have been looking at yourself through the lens that they shoot Elizabeth Taylor through.’ I couldn’t stop wondering how I got to be this age.”

When “The Bluest Eye” was published, in 1970, Morrison was unknown and thirty-nine years old. The initial print run was modest: two thousand copies in hardcover. Now a first edition can fetch upward of six thousand dollars. In 2000, when “The Bluest Eye” became a selection for Oprah’s Book Club, Plume sold more than eight hundred thousand paperback copies. By then, Toni Morrison had become Toni Morrison—the first African-American to win the Nobel Prize in Literature, in 1993. Following “The Bluest Eye,” Morrison published seven more novels: “Sula” (1973), “Song of Solomon” (1977), “Tar Baby” (1981), “Beloved” (1987), “Jazz” (1992), “Paradise” (1998), and now “Love.” Morrison also wrote a critical study, “Playing in the Dark: Whiteness and the Literary Imagination” (1992), which, like all her novels since “Song of Solomon,” became a best-seller. She has edited several anthologies—about O.J., about the Clarence Thomas hearings—as well as collections of the writings of Huey P. Newton and James Baldwin. With her son Slade, she has co-authored a number of books for children. She wrote the book for a musical, “New Orleans” (1983); a play, “Dreaming Emmett” (1986), which reimagined the life and death of Emmett Till, the fourteen-year-old black boy who was murdered in Mississippi in 1955; a song cycle with the composer André Previn; and, most recently, an opera based on the life of Margaret Garner, the slave whose story inspired “Beloved.” She was an editor at Random House for nineteen years—she still reads the Times with pencil in hand, copy-editing as she goes—and has been the Robert F. Goheen Professor in the Council of the Humanities at Princeton since 1989.

“I know it seems like a lot,” Morrison said. “But I really only do one thing. I read books. I teach books. I write books. I think about books. It’s one job.” What Morrison has managed to do with that job—and the criticism, pro and con, she has received for doing it—has made her one of the most widely written-about American authors of the past fifty years. (The latest study of her work, she told me, is a comparison of the vernacular in her novels and William Faulkner’s. “I don’t believe it,” I said. “Believe it,” she said, emphatically.) Morrison—required reading in high schools across the country—is almost always treated as a spokeswoman for her gender and her race. In a review of “Paradise,” Patricia Storace wrote, “Toni Morrison is relighting the angles from which we view American history, changing the very color of its shadows, showing whites what they look like in black mirrors. To read her work is to witness something unprecedented, an invitation to a literature to become what it has claimed to be, a truly American literature.” It’s a claim that her detractors would also make, to opposite effect.

“I’m already discredited, I’m already politicized, before I get out of the gate,” Morrison said. “I can accept the labels”—the adjectives like “black” and “female” that are often attached to her work—“because being a black woman writer is not a shallow place but a rich place to write from. It doesn’t limit my imagination; it expands it. It’s richer than being a white male writer because I know more and I’ve experienced more.”

Morrison also owns a home in Princeton, where nine years ago she founded the Princeton Atelier, a program that invites writers and performing artists to workshop student plays, stories, and music. (Last year, she brought in the poet Paul Muldoon as a co-director.) “I don’t write when I’m teaching,” she said. “Teaching is about taking things apart; writing is about putting things together.” She and her sons own an apartment building farther up the Hudson, which houses artists, and another building across the street from it, which her elder son Ford, an architect, is helping her remodel into a study and performance center. “My sister Lois said that the reason I buy all these houses is because we had to move so often as children,” Morrison said, laughing.

Morrison’s family—the Woffords—lived in at least six different apartments over the course of her childhood. One of them was set on fire by the landlord when the Woffords couldn’t pay the rent—four dollars a month. In those days, Toni, the second of four children (she had two brothers, now dead), was called Chloe Ardelia. Her parents, George and Ramah, like the Breedloves, were originally from the South (Ramah was born in Greenville, Alabama; George in Cartersville, Georgia). Like many transplanted Southerners, George worked at U.S. Steel, which was particularly active during the Second World War and attracted not only American blacks but also displaced Europeans: Poles, Greeks, and Italians.

Morrison describes her father as a perfectionist, someone who was proud of his work. “I remember my daddy taking me aside—this was when he worked as a welder—and telling me that he welded a perfect seam that day, and that after welding the perfect seam he put his initials on it,” she recalled. “I said, ‘Daddy, no one will ever see that.’ Sheets and sheets of siding would go over that, you know? And he said, ‘Yes, but I’ll know it’s there.’ ” George also worked odd jobs, washing cars and the like, after hours at U.S. Steel. Morrison remembers that he always had at least two other jobs.

Ramah, a devout member of the African Methodist Episcopal Church, was a homemaker. From the first, it was clear that Morrison was not made to follow in her footsteps. “I remember going outside to hang some clothes on the line,” she said. “And I held the pants up, I hooked them by the inside pockets. And whatever else I was doing, it was completely wrong. Then my mother or my grandmother came out and they just started to laugh, because I didn’t know how to hang up clothes.” Her parents seemed to have different expectations for her, anyway. “I developed a kind of individualism—apart from the family—that was very much involved in my own daydreaming, my own creativity, and my own reading. But primarily—and this has been true all my life—not really minding what other people said, just not minding.”

The Woffords told their children stories and sang songs. After dinner, their grandfather would sometimes take out his violin and everyone would dance. And no matter how many times Ramah told the ghost stories she had learned from her mother and her Auntie Bell in Alabama, Chloe always wanted to hear more. She used to say, “Mama, please tell the story about this or that,” her mother recalled in a 1982 interview with the Lorain Journal. “Finally I’d get tired of telling the stories over and over again. So I made up a new story.” Ramah’s stories sparked Morrison’s imagination. She fell in love with spoken language.

Morrison always lived, she said, “below or next to white people,” and the schools were integrated—stratification in Lorain was more economic than racial—but in the Wofford house there was an intense suspicion of white people. In a 1976 essay, Morrison recalled watching her father attack a white man he’d discovered lurking in their apartment building. “My father, distrusting every word and every gesture of every white man on earth, assumed that the white man who crept up the stairs one afternoon had come to molest his daughters and threw him down the stairs and then our tricycle after him. (I think my father was wrong, but considering what I have seen since, it may have been very healthy for me to have witnessed that as my first black-white encounter.)” I asked her about the story. “The man was a threat to us, we thought,” Morrison replied. “He scared us. I’m sure that man was drunk, you know, but the important thing was the notion that my father was a protector, and particularly against the white man. Seeing that physical confrontation with a white man and knowing that my father could win thrilled, excited, and pleased me. It made me know that it was possible to win.”

Morrison’s family was spread along a color spectrum. “My great-grandmother was very black, and because we were light-skinned blacks, she thought that we had been ‘tampered with,’ ” she said. “She found lighter-skinned blacks to be impure—which was the opposite of what the world was saying about skin color and the hierarchy of skin color. My father, who was light-skinned, also preferred darker-skinned blacks.” Morrison, who didn’t absorb her father’s racism, continues to grapple with these ideas and argue against their implications. In a television interview some years ago, she said that in art “there should be everything from Hasidic Jews to Walter Lippmann. Or, as I was telling a friend, there should be everything from reggae hair to Ralph Bunche. There should be an effort to strengthen the differences and keep them, so long as no one is punished for them.” Morrison addressed her great-grandmother’s notion of racial purity in “Paradise,” where it is the oppressive basis for a Utopian community formed by a group of dark blacks from the South.

As a child, Morrison read virtually everything, from drawing-room comedies to Theodore Dreiser, from Jane Austen to Richard Wright. She was compiling, in her head, a reading list to mine for inspiration. At Hawthorne Junior High School, she read “Huckleberry Finn” for the second time. “Fear and alarm are what I remember most about my first encounter” with it, she wrote several years ago. “My second reading of it, under the supervision of an English teacher in junior high school, was no less uncomfortable—rather more. It provoked a feeling I can only describe now as muffled rage, as though appreciation of the work required my complicity in and sanction of something shaming. Yet the satisfactions were great: riveting episodes of flight, of cunning; the convincing commentary on adult behavior, watchful and insouciant; the authority of a child’s voice in language cut for its renegade tongue and sharp intelligence. Nevertheless, for the second time, curling through the pleasure, clouding the narrative reward, was my original alarm, coupled now with a profoundly distasteful complicity.”

When she was twelve years old, Morrison converted to Catholicism, taking Anthony as her baptismal name, after St. Anthony. Her friends shortened it to Toni. In junior high, one of her teachers sent a note home to her mother: “You and your husband would be remiss in your duties if you do not see to it that this child goes to college.” Shortly before graduating from Lorain High School—where she was on the debating team, on the yearbook staff, and in the drama club (“I wanted to be a dancer, like Maria Tallchief”)—Morrison told her parents that she’d like to go to college. “I want to be surrounded by black intellectuals,” she said, and chose Howard University, in Washington, D.C. In support of her decision, George Wofford took a second union job, which was against the rules of U.S. Steel. In the Lorain Journal article, Ramah Wofford remembered that his supervisors found out and called him on it. “ ‘Well, you folks got me,’ ” Ramah recalled George’s telling them. “ ‘I am doing another job, but I’m doing it to send my daughter to college. I’m determined to send her and if I lose my job here, I’ll get another job and do the same.’ It was so quiet after George was done talking, you could have heard a pin drop. . . . And they let him stay and let him do both jobs.” To give her daughter pocket money, Ramah Wofford worked in the rest room of an amusement park, handing out towels. She sent the tips to her daughter with care packages of canned tuna, crackers, and sardines.

Morrison loved her classes at Howard, but she found the social climate stifling. In Washington in the late forties, the buses were still segregated and the black high schools were divided by skin tone, as in the Deep South. The system was replicated at Howard. “On campus itself, the students were very much involved in that ranking, and your skin gave you access to certain things,” Morrison said. “There was something called ‘the paper-bag test’—darker than the paper bag put you in one category, similar to the bag put you in another, and lighter was yet another and the most privileged category. I thought them to be idiotic preferences.” She was drawn to the drama department, which she felt was more interested in talent than in skin color, and toured the South with the Howard University Players. The itineraries were planned very carefully, but once in a while, because of inclement weather or a flat tire, the troupe would arrive in a town too late to check in to the “colored” motel. Then one of the professors would open the Yellow Pages and call the minister of the local Zion or Baptist church, and the players would be put up by members of the congregation. “There was something not just endearing but welcoming and restorative in the lives of those people,” she said. “I think the exchange between Irving Howe and Ralph Ellison is along those lines: Ralph Ellison said something nice about living in the South, and Irving Howe said, ‘Why would you want to live in such an evil place?’ Because all he was thinking about was rednecks. And Ralph Ellison said, ‘Black people live there.’ ”

After graduating from Howard, in 1953, she went on to Cornell, where she earned a master’s degree in American literature, writing a thesis titled “Virginia Woolf’s and William Faulkner’s Treatment of the Alienated.” What she saw in their work—“an effort to discover what pattern of existence is most conducive to honesty and self-knowledge, the prime requisites for living a significant life”—she emulated in her own life. She went back to Howard to teach, and Stokely Carmichael was one of her students. Around this time, she met and married Harold Morrison, a Jamaican-born architect. She joined a writing group, where the one rule was that you had to bring something to read every week. Among the writers in that group were the playwright and director Owen Dodson and his companion the painter Charles Sebree. At first, Morrison said, she brought in “all that old junk from high school.” Then she began writing a story about a little black girl, Pecola Breedlove, who wanted blue eyes.

“I wanted to take the name of Peola”—the “tragic mulatto” character from the 1934 movie “Imitation of Life”—“and play with it, turn it around,” Morrison said. When she was young, she said, “another little black girl and I were discussing whether there was a real God or not. I said there was, and she said there wasn’t and she had proof: she had prayed for, and not been given, blue eyes. I just remember listening to her and imagining her with blue eyes, and it was a grotesque thing. She had these high cheekbones and these great big slanted dark eyes, and all I remember thinking was that if she had blue eyes she would be horrible.”

When Morrison read the story to the writing group, Sebree turned to her and said, “You are a writer.”

In 1964, Morrison returned to Lorain. Her marriage had fallen apart and she had to determine how she was going to take care of her family—her son Ford was three years old and Slade was on the way. An ad in The New York Review of Books listed a position with L. W. Singer, a textbook division of Random House that was based in Syracuse. Morrison applied for and got the job. She took her babies (Slade was born in 1965) and moved East. She was thirty-four years old. In Syracuse, she didn’t care to socialize; instead, she returned to the story about the girl who wanted blue eyes and began to expand it. She wrote when she could—usually after the children went to sleep. And since she was the sole support for her children, she couldn’t sacrifice the real world for her art. “I stole time to write,” she said. “Writing was my other job—I always kept it over there, away from my ‘real’ work as an editor or teacher.” It took her five years to complete the book, because she enjoyed the process so much.

Holt, Rinehart & Winston published “The Bluest Eye” in 1970, with a picture of Morrison lying on her side against a white backdrop, her hair cut in an Afro. Taken at the moment when fashion met the counterculture—when Black was coöpted as Beautiful and soul-food recipes ran in fashion magazines next to images of Black Panther wives tying their heads up in bright fabric—the picture was the visual equivalent of the book: black, female, individualistic.

Set in Lorain at the end of the Depression, “The Bluest Eye” remains the most autobiographical of Morrison’s novels. In it, she focusses on the lives of little black girls—perhaps the least likely, least commercially viable story one could tell at the time. Morrison positioned the white world at the periphery; black life was at the center, and black females were at the center of that. Morrison wasn’t sentimental about the black community. Cholly Breedlove rapes his daughter Pecola because it is one of the few forms of power he has (“How dare she love him?” he thinks. “Hadn’t she any sense at all? What was he supposed to do about that? Return it? How? What could his calloused hands produce to make her smile?”); a group of children scapegoat her as her misfortune worsens (“All of us—all who knew her—felt so wholesome after we cleaned ourselves on her. We were so beautiful when we stood astride her ugliness”); and three whores are her only source of tenderness (“Pecola loved them, visited them, and ran their errands. They, in turn, did not despise her”).

The writing, on the other hand, was lush, sensible-minded, and often hilarious. If Morrison had a distinctive style, it was in her rhythms: the leisurely pace of her storytelling. Clearly her writing had grown out of an oral tradition. Rather than confirm the reader’s sense of alienation by employing distancing techniques, Morrison coaxed the reader into believing the tale. She rooted her characters’ lives in something real—certainly in the minds of black readers.

This came at a time when the prevailing sensibility in most American novels was urban and male, an outgrowth of the political and personal concerns that Ellison and Bellow, Baldwin and Roth had developed living in predominantly black or Jewish neighborhoods. Morrison was different. She grew up in an integrated town in the heart of America. “The point was to really open a book that’s about black people, or by a black person, me or anybody,” she said. “In the sixties, most of the literature was understood by the critics as something sociological, a kind of revelation of the lives of these people. So there was a little apprehension, you know—Is it going to make me feel bad, is it going to make me feel good? I said, I’m going to make it as readable as I can, but I’m not going to pull any punches. I don’t have an agenda here.”

One of the few critics to embrace Morrison’s work was John Leonard, who wrote in the Times, “Miss Morrison exposes the negative of the Dick-and-Jane-and-Mother-and-Father-and-Dog-and-Cat photograph that appears in our reading primers and she does it with a prose so precise, so faithful to speech and so charged with pain and wonder that the novel becomes poetry. . . . ‘The Bluest Eye’ is also history, sociology, folklore, nightmare and music.”

The poet Sonia Sanchez, who taught “The Bluest Eye” in her classroom at Temple University, saw the book as an indictment of American culture. For Pecola, the descendant of slaves, to want the master’s blue eyes represents the “second generation of damage in America,” Sanchez told me. “For this woman, Toni Morrison, to write this, to show this to us—it was the possible death of a people right there, the death of a younger generation that had been so abused that there was really no hope. What Toni has done with her literature is that she has made us look up and see ourselves. She has authenticated us, and she has also said to America, in a sense, ‘Do you know what you did? But, in spite of what you did, here we is. We exist. Look at us.’ ”

“What was driving me to write was the silence—so many stories untold and unexamined. There was a wide vacuum in the literature,” Morrison said. “I was inspired by the silence and absences in the literature.” The story she told was a distinctly American one: complicated, crowded, eventful, told from the perspective of innocents. “I think of the voice of the novel as a kind of Greek chorus, one that comments on the action,” she once said. She was a social realist, like Dreiser, with the lyricism and storytelling genius of someone like Isak Dinesen.

In 1968, Morrison was transferred to New York to work in Random House’s scholastic division. She moved to Queens. (“I never lived in Manhattan,” she said. “I always wanted a garden.”) A couple of years later, Robert Bernstein, who was then the president of Random House, came across “The Bluest Eye” in a bookstore. “Is this the same woman who works in the scholastic division?” he asked Jason Epstein, then the editorial director of Random House. Morrison had been wanting to move into trade publishing, and went to see Robert Gottlieb, the editor-in-chief of Knopf, an imprint of Random House. Gottlieb recalled the interview: “I said, ‘I like you too much to hire you, because in order to hire you I have to feel free to fire you. But I’d love to publish your books.’ ” He became her editor, and Morrison got a job under Epstein as a trade editor at Random House.

At Random House, Morrison published Gayl Jones, Toni Cade Bambara, and Angela Davis, among others. She was responsible for “The Myth of Lesbianism,” one of the first studies of the subject from a major publisher, and “Giant Talk,” Quincy Troupe and Rainer Schulte’s anthology of Third World writing. Morrison gave me a copy of one of the first books she worked on, “Contemporary African Literature,” published in 1972, a groundbreaking collection that included work by Wole Soyinka, Chinua Achebe, Léopold-Sédar Senghor, and Athol Fugard. (For some of them, it was their first publication in America.) The book is lavishly illustrated, with many color photographs of African tribesmen and African landscapes. Showing me the table of contents, Morrison said, “What was I thinking? I thought if it was beautiful, people would buy it.” (Not many did.)

The women she worked with, in particular, became some of her closest friends. “Single women with children,” she said, when I asked her about that era. “If you had to finish writing something, they’d take your kids, or you’d sit with theirs. This was a network of women. They lived in Queens, in Harlem and Brooklyn, and you could rely on one another. If I made a little extra money on something—writing freelance—I’d send a check to Toni Cade with a note that said, ‘You have won the so-and-so grant,’ and so on. I remember Toni Cade coming to my house with groceries and cooking dinner. I hadn’t asked her.” The support was intellectual as well as practical. Sonia Sanchez told me, “I think we all looked up and saw that we were writing in different genres, but we were experiencing the same kinds of things, and saying similar kinds of things.” Their books formed a critical core that people began to see as the rebirth of black women’s fiction.

Before the late sixties, there was no real Black Studies curriculum in the academy—let alone a post-colonial-studies program or a feminist one. As an editor and author, Morrison, backed by the institutional power of Random House, provided the material for those discussions to begin. The advent of Black Studies undoubtedly helped Morrison, too: “It was the academic community that gave ‘The Bluest Eye’ its life,” she said. “People assigned it in class. Students bought the paperback.”

In order to get attention for her authors—publishers still thought that the ideal book buyer was a thirty-year-old Long Island woman, and reviewers would lump together books by Ishmael Reed and Angela Davis, along with children’s books, in a single article—Morrison decided to concentrate on one African-American text each season. She worked diligently. “I wanted to give back something,” she said. “I wasn’t marching. I didn’t go to anything. I didn’t join anything. But I could make sure there was a published record of those who did march and did put themselves on the line. And I didn’t want to fail my grandmother. I didn’t want to hear her say, ‘You went to college and this is all you thought up?’ ” She laughed. “Compared to what my family had gone through and what I felt was my responsibility, the corporation’s interest was way down on the list. I was not going to do anything that I thought was nutty or disrupt anything. I thought it was beneficial generally, just like I thought that the books were going to make them a lot of money!”

Morrison’s view of contemporary black literature transcended the limitations of the “down with honky” school of black nationalism popularized by writers like Eldridge Cleaver and George Jackson. She preferred to publish writers who had something to say about black American life that reflected its rich experience. In 1974, she put together “The Black Book,” a compendium of photographs, drawings, songs, letters, and other documents that charts black American history from slavery through Reconstruction to modern times. The book exercised a great influence over the way black anthropology was viewed.

At first, Random House resisted the idea of “The Black Book.” “It just looked to them like a disaster,” Morrison said. “Not so much in the way it was being put together, but because they didn’t know how to sell it. ‘Who is going to buy something called “The Black Book”?’ I had my mother on the cover—what were they talking about?” She wrote about the project in the February 2, 1974, issue of Black World: “So what was Black life like before it went on TV? . . . I spent the last 18 months trying to do a book that would show some of that. A genuine Black history book—one that simply recollected Black Life as lived. It has no ‘order,’ no chapters, no major themes. But it does have coherence and sinew. . . . I don’t know if it’s beautiful or not (it is elegant, however), but it is intelligent, it is profound, it is alive, it is visual, it is creative, it is complex, and it is ours.”

Despite all misgivings, the book garnered extraordinary reviews. Writing in the Cleveland Plain Dealer, Alvin Beam said, “Editors, like novelists, have brain children—books they think up and bring to life without putting their own names on the title page. Mrs. Morrison has one of these in the stores now, and magazines and newsletters in the publishing trade are ecstatic, saying it will go like hotcakes.”

Morrison got a letter from a man in prison who had read the book. “Somebody had given him a copy, and he wrote to say thank you,” Morrison told me. “And then he said, ‘I need two more copies, because I need one to pass out to other people, and I need another one to throw up against the wall. And I need the one I have to hold close.’ So there were readers on, quote, ‘both sides of the street,’ which is the way they put it.” I recall buying “The Black Book” as a teen-ager and feeling as if I had been given a road map of the Brooklyn community where I lived at the time.

“Toni became not a black editor but the black editor,” a friend of hers told me. In 1975, D. Keith Mano, the “Book Watch” columnist for Esquire, devoted an entire article to Gayl Jones and her new book, “Corregidora,” but the piece was as much about Morrison as about Jones. “Toni Morrison is Gayl’s Svengali editor at Random House,” Mano wrote. “Toni is dynamic, witty, even boisterous in a good-humored way. And sharp. Very sharp. She often uses the pronoun I. She’ll say, ‘I published “Corregidora.” ’ . . . I suspect the title page of ‘Corregidora’ should read, ‘by Gayl Jones, as told to Toni Morrison.’ ” If Morrison had been a man or white, it seems unlikely that Mano would have noticed her championing of an author. Jones was uncommunicative and Morrison had books to sell. If a writer needed fussing, she fussed, and if not, not.

Morrison was a canny and tireless editor. “You can’t be a slouch in Toni’s presence,” the scholar Eugene Redmond told me. “Her favorite word is ‘wakeful.’ ” (She still gets up at 4 a.m. to work.) When she published the books of Henry Dumas—a little-known novelist and poet whose work was left fragmentary when he was murdered by a transit officer in the New York City subway in 1968, in a case of mistaken identity—she sent copies to Bill Cosby, Ossie Davis, Ruby Dee, and all the major movie executives and television hosts. In a letter inviting people to read at a tribute to Dumas, she wrote, “He was brilliant. He was magnetic and he was an incredible artist. . . . We are determined to bring to the large community of Black artists and Black people in general this man’s work.”

The racial climate in the mid-seventies made it especially hard for Morrison to promote certain books—books that might be taken as too radical. Morrison remembered that the marketing department balked when she wanted to have a publication party in a club on 125th Street. No one from Random House came—it was rumored that someone in management had cautioned the staff about the danger—except the publicist and her assistant, who said it was the best party they’d ever been to. A couple of news crews showed up, however, and the party was on the evening news, giving the book hundreds of thousands of dollars’ worth of free publicity, by Morrison’s reckoning. Similarly, Morrison said, when she brought out Muhammad Ali’s autobiography, “The Greatest,” in 1976, all the department stores that were approached about hosting the book signing backed out, fearing riots and looting. When E. J. Korvette’s, the now defunct department store, agreed to host the signing, Morrison brought in members of the Nation of Islam, who came with their families, as peacekeepers. She also installed a white friend, a woman who worked in the sales department, to guard Ali. “You stand right next to Ali,” she said. “And when people come up and punch him—‘Hey, Champ!’—you stop them. Because he’s not going to say it ever, that it hurts when you get a thousand little taps. And when you think Ali is tired give him a baby to play with. He likes babies.” Two thousand people came to E. J. Korvette’s, on a rainy night, and, with the Brothers of the Nation of Islam milling around in the crowd, everything was serene and orderly.

Throughout the seventies, Morrison worked as a teacher at Yale, sunyPurchase, Bard, Rutgers, and suny Albany. “Random paid about ten cents, so Toni took on teaching jobs,” Jason Epstein recalled. In a 1998 interview, she said, “When I wanted a raise, in my employment world, they would give me a little woman’s raise and I would say, ‘No. This is really low.’ And they would say, ‘But,’ and I would say, ‘No, you don’t understand. You’re the head of the household. You know what you want. That’s what I want. I want that. I am on serious business now. This is not girl playing. This is not wife playing. This is serious business. I am the head of a household, and I must work to pay for my children.’ ”

“The Bluest Eye” had made the literary establishment take notice. In “Sula,” which was published three years later, Morrison’s little colored girls grew up and occupied a more completely rendered world. “The Bluest Eye” was divided by seasons; “Sula” was divided into years, stretching from 1919 to 1965. Again, the story is set in a small Ohio town, in a neighborhood called the Bottom. (“A joke. A nigger joke. That’s the way it got started.”) Sula Mae Peace, Morrison’s heroine, is the progeny of an eccentric household run by formidable women. She leaves the Bottom in order to reinvent herself. Morrison does not relay what Sula does when she ventures into the world, but her return is catastrophic. (The first sign of impending disaster is a plague of robins.) Her return also brings about a confrontation with her grandmother Eva—a parable of the New Negro Woman confronting the Old World.