#there is more nuance to their dynamic than my art ever gives them credit for thats just an essay for another time.

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

alexa play victorious by panic! at the disco

#fallout#fallout new vegas#benny gecko#courier six#fnv#this is just a dump of stuff i cant justify uploading individually or that im sick of sitting on my hard drive lololol#maybe i'll finish some of it someday. who knows#there is more nuance to their dynamic than my art ever gives them credit for thats just an essay for another time.#and nobody askng to see that shit lmfao#im just not a very good Artiste#my art

145 notes

·

View notes

Text

cdrama rec/review: go ahead

KDRAMA AND CDRAMA MASTER LIST OF REVIEWS

Series: go ahead Episodes: 40 Genres: family, healing/melodrama, slice of life, romance Spoilers in the Rec: for the first 20% ish/set-up If You Like, You’ll Like: reply 1988, le coup de foudre, find yourself (same production company/main male actor), rain or shine/just between lovers, found family stories, meet again stories

Rank: 10/10** (see Drawbacks section)

PREMISE

widower hai chao and his 6 year old daughter jian jian live happily above his noodle restaurant despite the recent, tragic death of his wife. one day, dysfunction junction a married couple (he ping, a police officer, and chen ting, a real piece of work) move into the same building with their 7 year old son, ling xiao. immediately, jian jian attaches herself to ling xiao, who is unexpectedly grim for a small child.

because ling xiao’s family is less-than-healthily grieving the loss of their youngest child, ling xiao’s sister who died in a terrible accident. The Apartment of Unhealthy Coping Mechanisms eventually implodes, ending with chen ting abandoning her husband and son. he ping, suddenly a single father, and hai chao come to a friendly partnership that is clearly alluding to gay marriage where they co-raise both of their kids--hai chao as the primary caregiver, and he ping supporting them financially through his job as a policeman.

meanwhile, the neighborhood busybody is dead-set on getting hia chao remarried. eventually she introduces him to a divorced single mother, he mei, and her son zi qiu, who is ling xiao’s age. they sort of start to date, but it culminates in he mei skipping town and leaving zi qiu behind. hai chao, man with a heart of gold, informally adopts him and zi qiu becomes jianjian’s foster brother.

from there, the trio grow up happily and become inseparable. but once zi qiu and ling xiao graduate high school, the bullshit parade their respective childhood skeletons reappear in their lives. circumstances lead to the boys moving overseas, leaving jianjian and their fathers behind.

they reunite after 9 years, when the boys return to a home where they hope to pick things back up from where they left off. things are more complicated than that, as jianjian finds herself in a new life and surrounded by new people.

MAIN CHARACTERS

li jian jian

hai chao’s daughter and the only girl in the family. she attended the required short-hair-low-grades training program required of all cdrama youth female leads. super positive and outgoing, as well as the youngest of the three pseudo-siblings, jian jian grows up spoiled and over protected by her father and brothers, and as a result is completely devastated once her family falls apart. it’s so sad.

after the time skip, she’s an on-the-verge successful artist who makes woodcarvings, and exudes big art bro energy. inhales sugar like it’s nobody’s business. she inherited her father’s disease called caring too much, and it’s incurable!!

ling xiao

the eldest brother and resident fun police. ling xiao comes from a seriously toxic home that finally seems to improve once his mother leaves. but then she comes back. fucking great. introverted to the point of being withdrawn to anyone but his chosen family, ling xiao’s had to carry a lot of emotional weight that takes a larger and larger toll on him as the series progresses. please get this boy some therapy.

becomes a dentist because jian jian needs one. wears a lot of monochromatic outfits with low necklines because heavy angst but make it fashion. has been in love with jian jian since high school and is still carrying that torch 9 years later.

he zi qiu

the middle child who grows up in hai chao and jian jian’s home, and is her foster brother in all but paperwork. hotheaded, zi qiu and jian jian basically share two brain cells that ling xiao routinely takes from them for safekeeping. he spoils jian jian, sneaking her snacks and junk food and wants to become a pastry chef so he can open a sweet shop for her!!

my favorite character. just wants to be wanted 8( him and hai chao’s relationship is my favorite dynamic in the series. will sob while driving a pink moped. is too proud to beg

li hai chao (left) and ling he ping (right)

the greatest (hai chao) and okayest (he ping) dads in the world! noodle dad/hai chao has never done anything wrong in his life, ever, and we know this and we love him. he ping isn’t a bad person, but demonstrates pretty classic absentee parenting/isn’t as emotionally present in his son’s life as hai chao. hai chao is the heart of the family, and would do anything for his kids 8(

SOME SUPPORT CHARACTERS

tang can (left) and qiu ming yue (right)

jian jian’s #GirlGang and roommates. they, like literally everyone in this drama, have some severe mom issue hang-ups. tang can (left) is a former child actress who is struggling with her lack of success as an adult and gives well-meaning but absolutely terrible advice on the regular.

ming yue (right) is jian jian’s best friend since childhood and as an adult is trying to break free from her mother’s controlling nature--she’s also had a thing for ling xiao for the last 9 years. raises fish for symbolism purposes.

chen ting

ling xiao’s mom and certified garbage human. unable to cope with the death of her daughter that was her fault lbr, she abandons her family and disappears for ten years. she forces her way back into ling xiao’s life when he turns 18, where it’s revealed that she’s remarried and ling xiao has a younger half-sister chengzi (”little orange”). shit goes down, and soon ling xiao is forced to move back to singapore to serve as primary caregiver to both his mother who abandoned him and the half sister he barely knows.

emotionally abusive and basically hits every single square on the toxic parent bingo card. i just. i just hate her. even typing this out is making me mad.

he mei

zi qiu’s mother. after a few dates with hai chao, she ends up ditching her kid and disappearing for unknown reasons. is a slightly better parent than chen ting but that’s like saying some poison kills you slower. the show tries to bring us around on her but it didnt work for me.

SOME OTHERS

zhuang bei, zi qiu’s best friend growing up who i would like a lot less if he wasn’t played by the same actor who played my beloved dachuan

zheng shuran, jian jian’s first boyfriend and fellow artist who’s got a weird thing for women’s waists and pretentious artists’ statements

du juan, jian jian’s friend who co-owns their woodworking studio. has absolute trash taste in men

chengzi, ling xiao’s half-sister who can be a brat but dear god does she need to be protected/saved

**DRAWBACKS

so this is a weird one for me. what i didn’t like i really didn’t like, but what i loved i really loved. ultimately, the factors/uniqueness of this show and the loveability of the main characters outweighed the negatives and it’s one of my favorite dramas.

THAT SAID. i got some #thoughts on this one.

first, there are literally no positive mother figures in this show. not a damn one. they are all negligent or controlling at best or down right abusive at worst. no woman over 30 is portrayed positively and that’s a big No from me.

the last 10 eps have some pacing issues and focus on the wrong people. spending the remaining episodes focused on one of the most universally hated characters vs. the main family was a bad move

the show tried to redeem or make us sympathize with characters that were, to me, completely irredeemable. one case is worse than the other, but both of them were terrible people that deserved to be cut out of the main family’s lives.

REASONS TO WATCH

the main family. the characters are so wonderful and nuanced, and their dynamics with one another were amazing. you’ll fall in love with hai chao aka noodle dad and the trio. they go through so many trials but they still stick together and it’s ultimately a healing drama and i loved it very much.

the central romance was less in focus, but the pining is enough to make jane austen emerge from the grave. i loved the leads together, and while LOL ling xiao’s attachment to jian jian was not always healthy, they supported each other and it made me smile. i love me a tortured pining dude.

#Acting. everyone played their parts to perfection. the child actors in particular were so well-cast (esp baby zi qiu)

the soundtrack lmao. you watch the opening credits and know you’ll need to buckle up

idk it’s a very unique show, and i haven’t seen one like it. reply 1988 comes close, but it doesn’t tackle the same issues and it was all just very real and earnest.

Final Thoughts.

GOODNIGHT, GOOODBYYYYYE MY CHILDREEEEEEEN

99 notes

·

View notes

Text

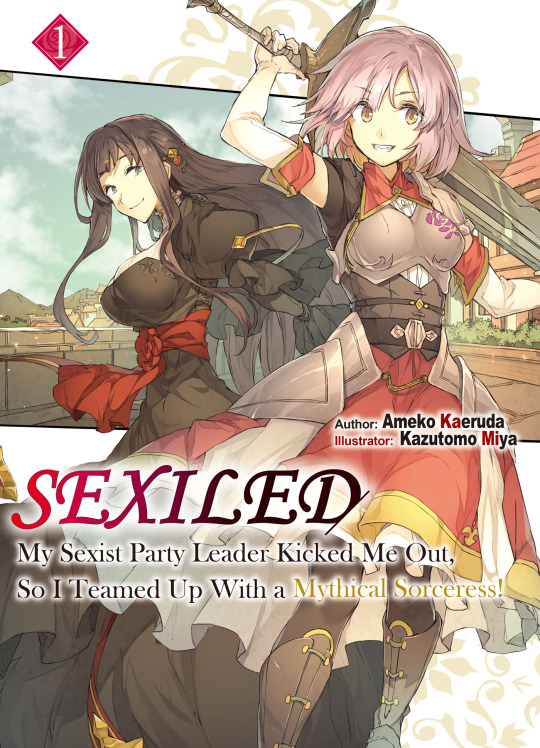

LGBTQ Light Novel Review - Sexiled Vol. 1

When J-Novel Club announced that they would be releasing Ameko Kaeruda’s light novel Sexiled: My Sexist Part Leader Kicked Me Out, So I Teamed Up with a Mythical Sorceress! I remember seeing some backlash on Twitter for the main title and cover art of the Sorceress, Laplace, exposing a solid third of breasts in a tight black dress. However, I dug a bit deeper into the work (because it is my job to do so) and was very excited at the prospective plot of women kicking ass, kissing girls, and fighting the patriarchy. After reading Sexiled, I am thrilled to say that my expectations were not only met, but exceeded by the length of a massive and impractical anime sword. This book is an excellent work of feminist literature and one of the best light novels I have ever read.

As the long title suggests, the story begins when Tanya Artemiciov, a prodigious mage, is fired from her adventuring party by its leader Ryan. The slimy, sexist, and cowardly antagonist of the book. Outraged, Tanya sets out to the wasteland to blow off steam in a spectacular and curse-riddled manner, when she accidentally releases Laplace, an ancient sorceress sealed away for centuries. After besting Laplace, the two women agree to form a party to enact sweet revenge against Ryan and take down the patriarchal society while they are at it.The story is not subtle at all with its mean themes. From the start, it is clear to the reader that sexist ideas dominate this society. Everything in the story, from the comments men make, “us men are just naturally better equipped for the job” to the oversexualized garments female adventurers are forced to wear, trace back to sexism. Great credit must be given to Kaeruda here, as the examples and instances of sexism are all taken from reality. The scores of female applicants to the mage’s school being docked mirrors last year’s scandals of Tokyo Medical School. Female adventurers are paid less and expected to retire early to start families, reflected the treatment of women in the corporate world. A full comparative list would easily take up half this review.

Not only are so many issues of sexism identified and explored in the light novel, but they are also each confronted by the heroes. Sexiled’s world and characters are typical of a power fantasy series. The protagonist is leagues stronger than anyone else, and the world has game-like qualities, with classes and levels. However, unlike the typical annoying male protagonist whose best defining character trait is “exists,” the women in Sexiled use their incredible powers to obliterate the oppressive systems. It is a pure indulgence to read, as there are few experiences more satisfying than reading descriptions of god-tier characters destroy selfish, egotistical, and demeaning men.

The sexist setting is the main focus of the story, which makes some of the plotlines predictable. However, there is a surprising amount of nuance in some of the issues presented. Tanya has lived her whole lives in this society and is thus blinded to the harsh reality and unfair circumstances around her. One of my favorite moments sees the women discussing armor and how revealing and sexual clothing is demeaning when forced, and empowering when chosen:

“‘Um, Laplace? You forgot to cover up your, uh… chest area.’ Hmm? Why should I?’ ‘Well, weren’t you saying we don’t need to show skin?’ ‘Correct–we don’t need to. But in this case, I want to.’”

Unfortunately, the plot is a bit monotonous. The one-note that is it, powerful women using magic to fight against sexism, is a superb one, but I would have liked to see a bit of variety or actions taken by women that were not solely motivated by men. It is disappointing to see that all the actions taken are in response to the atrocities of society, especially considering how feminist the book is. The points, while important, are merely the blemishes on a masterful work of art and culture. Sexiled remains one of the most engaging, fun, and relevant visual novels on the market.

Speaking of light novels, I have to mention and praise the prose in Sexiled. Usually, the writing in light novels is tolerable at best, and agonizing at worst. However, Kaeruda and the English translator Molly Lee, have done the unthinkable, crafting a light novel that is not only easy but enjoyable to read. Everything from the wonderful descriptions, entertaining dialogue, clever references, and wondrous use of profanity are highly polished and well crafted. A particular favorite of mine is Tanya’s incantation for the spell explosion, “From twilight, I summon the ultimate f***ing destruction! Ashes to ashes, dust to dust; heed my call and unleash your f***ing might! F*** this s***!” Sexiled has become the new bar for light novel localizations! A complete side note, Lee is also translating Seven Sea’s English adaption of the Adachi and Shimamura light novels, which gives me such hope for that series. Before I sing any more praises of Lee and Kaeruda, I should talk about the characters.

Both the main characters in Sexiled are lovely. Tanya is confident, powerful, kind, and a hilarious drunk. She seamlessly transitions between ruthlessness in battle to loving and compassionate when speaking to her friends. However, she never loses the sharp wit that helps her stay refreshing and hilarious. While I adore her, I am entirely entrenched by Laplace, who also goes by some fantastic pseudonyms, including “the Wicked Dragonwhore” and “Stone Cold Stunner.” She has an immense amount of self-confidence and an irresistible bravado. She is also very playful and enjoys teasing Tanya. The interactions between these two make for some of the best moments in the volumes:

“‘That look on your face says you think I’m nothing more than a human-shaped balloon.’ ‘Damn right!’ ‘Wow… I wish you would’ve at least tried to deny it…” They are perfect together.

Many of the female side characters have equally precise and detailed treatments. Nadine Amaryllis, a low-level healer that joins the girls’ party, is likable and has a comprehensive and dramatic backstory that functions as one of the work’s best reveals. Additionally, the minor villain, Katherine Foxxi, is one of the more dynamic characters. She starts blind to the sexism in her world but slowly changes throughout the novel. Unfortunately, Foxxi is also the focal point for one of the book’s only bad sequences. I would not be surprised to see a full redemption story or maybe an anti-hero persona for her in future volumes. However, the male villains are decidedly shallow. In fact, there is not a single half-decent, or even well-intentioned man present in the story. I do not mind, but it is a bit suspect. Other light novels have had similar villains and themes while still allowing for nuance and avoiding stereotyping an entire demographic.

The yuri elements in Sexiled are pretty minimal. Most of the story focuses on the women’s’ quest for revenge and their fight against the patriarchy, leaving little room for romance. There are a few light service moments where Laplace kisses Tanya, such as when she unlocks the mage’s full potential, but other than that, there is no physical contact. However, the strong bonds between the characters are apparent, and they all share a few touching scenes before the final chapters. A particular favorite of mine is Laplace using magic to make Nadine fly. There are also clear indications that the characters have multiple targets for their affections. Both Laplace and Tanya are implied to have interest in Nadine, as well as each other, thus sewing seeds for future romantic plots. While subtle, intense romantic relationships are present, and they add to the story while never distracting readers from it, which is a massive plus.

Sexiled: My Sexist Party Leader Kick Me Out, So I Teamed Up With a Mythical Sorceress! is an absolute must-read. The detailed and phenomenal writing is matched beautifully with strong female characters, hilarious dialogue, and exceptionally satisfying moments. It manages to expose the flaws of our society while providing an escape for those who suffer because of them. It does not make any profound or unique statements but allows the reader to revel in its indulgences. Sexiled is a spectacular masterpiece of fantasy and feminism that far outpaces other works in its genre and medium. This book is easily a new obsession of mine, and I cannot wait for the English release of volume two.

Ratings: Story – 10 Characters – 9 LGBTQ – 3 Lewd – 2 Final – 9

You can purchase Sexiled digitally now on Amazon: https://amzn.to/2J14WCj

Review copy provided by J-Novel Club

#yuri#reviews#lgbt#lgbtq#femnism#feminist#sexiled#queer#manga#light novel#anime#literature#wlw#fantasy#gay#lesbians

874 notes

·

View notes

Text

Cyberpunk 2077: Is This To Be An Empathy Test?

Cyberpunk 2077 is an adaptation and extrapolation of the popular tabletop pen-and-paper role-playing game Cyberpunk, originally published in 1988. The video game uses an extrapolation of the setting and Interlock system, translated to video game format.

When I finished the game, credits rolled. And rolled. And rolled. More than 15 minutes went by.

Now, days later, as I reflect on more than 70 hours of playtime, Cyberpunk 2077 feels like many people have had their hands in the pie. Its strengths and weaknesses stem from its massive ambition, marketing, and promises.

Different Experiences

I played CP2077 on a Ryzen 7 3700x with 32 gigs of RAM and an RX 2700 GPU. I was able to get around 35 FPS at 1440p without noticeable drops (except when looking in mirrors), and I played on ultra-settings without ray tracing on. I began playing it with the rest of the PC consumers with the day 1 patch.

As a crafted experience, I can say that it is the most impressive looking game I've ever played, and my playthrough seems to be a fortunate one, with maybe a handful of glitches or bugs across the entire 70 hours. None of which were remotely game-breaking. I was never unable to progress in the story. I never had a crash. The most annoying thing I experienced was sometimes crosshairs from a gun would continue to stay onscreen after it was holstered.

I mention this because I think a major component of why I come away with a positive experience is because my computer could deliver the intended experience. And Cyberpunk 2077 is unrivaled in its execution of a funneled narrative. Characters and environments have never felt more genuine and cinematic.

The sound design is some of the best I've heard, and it's perfect in every aspect of the game. From the sound of a throaty exhaust to the scraping of metal-tipped hands against hardwood, the sound is superb and adds to the immersion.

The World

With a setting as old as Cyberpunk, there will be consumers who are familiar with the setting and have a grasp on the worldbuilding. For the uninitiated, however—of which, I think most customers will be—the aesthetic and gameplay elements the marketing team used in advertisements will be the primary hook. The game doesn’t go out of its way to communicate that it is anything more than that, either.

What was most compelling about Night City was the meticulous detail and care devs clearly put into every nook and cranny of the city. Distinct and disparate, no part of it feels reused or like its filler. It is the most gorgeous and well-realized environment I've encountered in a video game.

Yet the gangs, fixers, and side jobs located within it feel one dimensional when viewed from a macro, worldbuilding perspective.

Typical fixer missions are varied enough and have different small bits of story, but usually just elucidating that specific mission and its characters. You’ll find little bits of lore some of the time, which augment the siloed stories, but often don’t give a wider context to help situate the faction you’re interacting with.

The gangs seem to have a central theme, but I never learned why they were actually there from a worldbuilding perspective, beyond the fact that the game wants you to be looting and shooting.

Culturally, the gang elements are too often a pastiche and don’t feel real. They have scripted lines that are often dehumanizing and feel unrealistic. Some of them don't even make any sense. They'll find a dead body and start yelling for you to come out, "cunt", or some other misogynistic pejorative. How do they know it's a woman? Making them all say and act that way feels so cheap, encouraging you to take them out because they're demonstrably “bad” people. And it doesn’t matter what kind of mission it is. Context doesn’t matter.

With the bits of lore you’ll find all over the place (often repeated), it feels like a missed opportunity to not humanize and characterize the gang identities as a whole; even if you are spending most of your time mowing them down, at least you’d come to understand why the city is the way it is and what its general makeup is better than just knowing which gang claims which area of the city.

The world feels overly concerned with aesthetics that the player never gets context for, so it feels like a caricature used for aesthetic purposes only.

For instance, Arasaka, the megacorporation controlling/running Night City, has a highly traditional, tyrannical, Japanese businessman who has had his life extended with cybernetics. He’s over one hundred years old and controls Arasaka with an iron fist. The inference on my part is that locations in Night City with heavy Asian aesthetics are there because of this megacorp’s influence. But it still feels strange because, in other lore given, the city has been run by other corporations not that long ago and had other cultural influences asserted. So why is Little China, Japantown, and Kabuki a weird pastiche and the only place that seems to assert its cultural influence on the city? When you enter other areas, they don’t look like they’re trying to recreate foreign cultures. Is it because of the Arasaka influence? Possibly, but I never found any lore that explained it. Visually, this aesthetic dominated my playthrough.

The result is a siloed microworld that feels like it might be there simply to justify some of the predominantly Asian gangs, who seem to be basically just cyberized yakuza and come up fairly often in fixer missions. The main story also springboards off some of these locations, so the game really wants this look to make an impression on the player.

When you explore in-depth, all of the interactable, consumable portions of the city have a faux quality because you can only look at them. Sometimes you can buy food from a couple of vendors and clothes, but everything exists solely to be interacted with in a hyper-specific way, rather than extrapolated from a perspective divorced from what would be merely aesthetically interesting and actually realistic enough to let V feel like a character that is a part of this world.

You can sleep with and date a few different people, depending on your gender presentation, but the relationship's extent beyond that varies. There are some texts between characters, but you don't get to, say, go home and do anything with them. Their interactions with you in person are the same as though you had phoned them.

You can talk to people on the sidewalk, but they have a regurgitated one-liner and then go back to what they're doing. You can't go up to a gang member and talk to them because once they see you, they’ll attack you if you get too close.

The only things that feel genuinely next level are the prescriptive story elements. And that's okay! It just doesn't jive with the level of detail or how much you think you'll be able to interact with things when you first see them. Marketing makes it seem like the world at large may be something you can interact with, but those all end up being the curated narratives.

Because the worldbuilding framework is from a first-wave cyberpunk perspective, unfortunately, pitfalls like techno-orientalism are prevalent.

The themes around the commodification of those things that make us human, from our body, faith, and art, are all interesting themes present in the genre—but here they are skewed toward fetishizing minorities and subcultures, just as first-wave cyberpunk texts tended to do.

V is ostensibly a cyberpunk and it follows that they would be a part of the same subgroup as the minorities who are underrepresented and lacking nuance in the CP2077 world, but V is actually traversing the story with their only integration into a subculture being that they’re a mercenary. With few exceptions, they all seem to not really share punk values, either. Some take jobs from corps (you certainly can if you want), some don’t like the corps but aren’t particularly anti-establishment or pro direct action. Most just seem to hang out at a bar. You don’t hear about what they do on the news or in the world. You don’t get jobs from fixers that are ideologically aligned with being punk. And you don’t integrate with any other subcultures when out of the main narratives.

The exploitation of people and the world's general themes and sensibilities still feel firmly rooted in the late 80s, early 90s. It is not aware enough to fully realize an actual subculture or even the dynamics of criminal elements in the city, so it frames the story from a mainstream perspective for mass appeal.

The problem is that, with so many people consuming the game, this becomes the default that those consumers will adopt. It has a responsibility precisely because it is so popular and will become a part of the general intellect. Rather than be progressive with its themes and push mainstream depiction of cyberpunk to something in line with what can be found in literature today, it is regressive.

Ultimately, the worldbuilding is the most disappointing aspect of Cyberpunk 2077. The main narratives, however, are a different story.

Story

Arguably, the most important thing for a role-playing game experience is the story. In 2077, you play V, a mercenary on the edges of society trying to make it big in Night City. In classic cyberpunk genre fashion, a chance at a big score drops into your relatively inexperienced hands, and you seize it. A heist is planned; it doesn't go as planned—and Johnny Silverhand, a long-dead anarchist and misogynistic jerk—basically a proto-typical embodiment of 70’s rock ethos—ends up in your head. He has his own agenda, and V can either go along, get along, or make their own decisions about what to do next. For the most part.

The story beats are as meticulously crafted as corners of Night City. The character animations are the most advanced I’ve ever seen—: they’ll smoke a cigarette for a portion of the conversation, stub it out, then get up and pace nervously while delivering their lines. Their emotions will be written on their face and flow naturally. They'll touch items or other people in the scene. They look and act like real people and sound like it too.

There’s a 4-part storyline with a trans character in which you just won’t ever learn their story unless you talk with them and earn their trust. You can go through the whole narrative and help them out (or not), and never learn much about them. But if you spend the time and ask questions, you'll always get something from these storylines, even if they initially seem to be just another gig on the map.

Because the game's worldbuilding, including in-game ads, is blind to its own defaultism, stories like this are absolutely vital. I wish there were more of them and I hope the free DLC forthcoming are things like this.

2077 is populated with genuine, human moments. They communicate why you should care about the city and the people you encounter. And most importantly: these moments define V as much as the main storyline.

Whether intentional or purely a byproduct of how each facet of the game was developed, these stories augment the play experience a tremendous amount.

What I remember most is finding out if Johnny can, and will, actually change or if he's just trying to manipulate me, discovering how my decisions alter the way he interacts with me, and going down a rabbit-hole, sex trafficking narrative that initially feels a bit too archetypical, only to have it morph into a multi-part story that rooted V's narrative in an emotional and impactful way.

These are the stories that you can actually, meaningfully change. And because I did them all before the main storyline, they all felt like they meshed well with my V’s overall story.

Of course, you could do the main story right away and then go back and do these side stories. I think the experience would be quite different because of the knowledge and relationship you have with Johnny at the end of the main story experience, though.

The main storyline has multiple endings; I've experienced four of them, and they all deliver fairly well on expectations. These endings do not consider anything that isn’t a main or side job, which is labeled as such in your log. Your relationships with the main characters do change the endings slightly, but they don't change the overall outcomes for V and Johnny. This made the game's main attraction for me the fleshed-out side narratives and a few other mysterious side jobs that crop up without a fixer giving them to you.

These other stories were more enjoyable because I felt like I really mattered and could actually mess them up. The main storyline is only preoccupied with whether or not you did X and, if so, you can see the Y ending. It felt like it had lower stakes.

Conclusion

I do feel like 2077 is a new way to consume an immersive role-playing video game experience. It's unfortunate and unfair to many people that multiple promises the game makes cannot be fulfilled unless they can experience it on a particular platform (with a fairly sizeable amount of money in the investment). A decent computer to play it on is the best way, and it’s expensive if you want to max out absolutely everything. Next-generation consoles aren't even optimized for it yet. Last generation consoles are struggling. Crashes, bugs, poor textures, and framerates.

What is Cyberpunk 2077 when it can’t replicate the ideal delivery for its desired experience?

So much of what made the experience singular and noteworthy for me comes down to how life-like and human the people I came to care about the most in the game looked and acted. Take that veneer away, and the cracks in the façade appear.

Doing most of the side content before the main jobs gave my V a meta-narrative: they were a ruthless killer that would do pretty much whatever a fixer asked of them. Those were the expectations set by the world outside of the story. But then V morphs into a person confronting that life, questions who they want to be, and what it takes to thrive in Night City when you hit the main narratives. That’s why I had a positive experience. And that’s why I’ll return to the city and do things differently.

Ironically, Cyberpunk 2077's overall game experience relies on technology to build empathy between the player and the main cast. Yet, the world outside of the main narrative denies that same empathy to the denizens and factions it populates Night City with. If the platform you’re playing on can’t effectively utilize the demanding Red Engine developed for Cyberpunk 2077, the most likely outcome is an experience devoid of the only substantive thing it has to offer.

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Nilo Blues Pays Homage to Cult Anime Film Akira in “Akira Harakiri” [Premiere + Q&A]

Photo: Frank Lin

The city of Toronto never ceases to amaze us. What can arguably be considered the epicenter for a new wave of hip-hop, Toronto has become notorious for generating underground sensation after sensation. Through their cultivation of hypnotic and innovative soundscapes, to their impeccable flows and lyricism, Toronto has solidified an extensive roster of industry frontrunners, and Nilo Blues is proving to be the newest addition to the team.

Despite being a self-proclaimed poster child for Generation Z, the 21-year-old is anything but ordinary. Growing up in the Toronto art scene, Blues encompasses what it means to be a multi-hyphenate creative, utilizing his talents as a singer, rapper, dancer, and producer to tell stories that grapple with his Asian identity within the context of western society.

His debut single, “No Risk Involved,” is an intrepid statement on Asian cultural identity and showcases how Blues’ struggle to live and create beyond rigid stereotypes has ultimately fueled him to pave his own way, in music and life. His nuanced and complex approach to the modern trap soundscape mirrors that of his own evolution and understanding of his own personal identity. Woven within his uncompromisingly honest storytelling and conviction lies the infectious hooks, melodic arrangements, and unsparing production of a true, multi-hyphenate artist. And despite “No Risk Involved” being the official introduction to his discography, we’re here to tell you that it’s just the tip of the iceberg for Blues.

As we patiently await his debut EP, set to release this summer, Blues gives us a peek at what’s to come with his most recent drop, “Akira Harakiri.” Explosive and audacious, this track has the power to cause havoc to the silencers of a corrupted system. Compiled within roaring trap-laden beats and terse hip-hop rhythms, Blues’ adroit vocals and dynamic fluidity convey a sense of fervor, all while challenging the status quo of Asian representation within American culture.

“Akira Harakiri” pays homage to the anime that Blues grew up with, most notably the raw tenacity of Akira and the thriving energy of Dragonball Z, which influenced its sonic foundation and cinematic execution. In an effort to gain a more comprehensive understanding of his artistry, we spoke with Blues about his position in the current Toronto-trap soundscape and what motivates him to create breakout tracks like “No Risk Involved” and “Akira Harakiri.”

Ones To Watch: It seems like dancing used to be a significant part of your life before music. What sparked your transition?

Nilo Blues: Growing up I was surrounded by music, whether it be at home or in the dance studio. I always had this natural appreciation for music grow in me because of all the different sounds I was surrounded by. I remember having 10-hour dance rehearsal days and then coming home to record photo booth videos of me and my best friend spitting melodies and lyrics over beats we found. I started producing at 16 when I discovered the iMaschine app for iPhone. I would spend hours trying to cook up beats until one day I decided to learn Ableton Live. My mentor cracked it on my laptop and started showing me the ropes, instantly I was hooked. My musical journey honestly started out from me just wanting to make music I could dance to. I owe a lot of myself to dance. 100%.

Has being a dancer influenced your creative process at all?

Dance has influenced me creatively in many different aspects of the process. Growing up as a dancer, you immediately instill a high level of discipline and work ethic as a young child. We were training like athletes and expressing like actors. It shaped the way I hear music (especially my own), it developed my approach on execution and staying on my P’s and Q’s, and it allows me to perform and add a visual component to the sonics. I grew up admiring Michael Jackson, James Brown, JT, Usher and now Bruno Mars. They all hold all aspects of their art to such a high standard. I’m trying to set that exact same standard and quality, through my own vernacular.

Growing up in what can be considered as the epicenter of Canadian hip-hop, do you think Toronto, and the artists that have put it on the map, have influenced your sound at all?

I started learning how to make music right when the 2015-2016 Toronto rap boom happened, so definitely. I feel like Toronto artists collectively do such an amazing job at emulating the vibe of Toronto. At a time where Toronto was only synonymous with Drake (the GOAT), The Weeknd, and PND, Toronto artists really stepped up to the plate and let the world hear the type of shit we’re on. It's super inspiring, and I just want to keep pushing the envelope. I’m trying to land where no one has before, and make my mark in everything I set my mind to. I’m hungry and I want to get great shit done. I thank Toronto and the lively music scene in the city for sparking that.

Your first single “No Risk Involved” highlights the misrepresentation of Asian identity in mainstream culture. Why was it so important for you to create your own narrative and debunk westernized versions of Asian culture and identity?

My family was the main inspiration for wanting to evoke that conversation. Western media loves to exploit the great ideas from different cultures without ever giving credit to the cultures that cultivated them to begin with. They perpetuate false narratives and generalize us in order to keep control. I’ve seen what my family has gone through in order to even be here. My mom is Filipino, and my dad is Viet-Chin, so I’ve had my fair share of perspectives at a young age. One thing I can guarantee is that Asians aren’t as one-dimensional as the media portrays us to be. It’s about genuinely telling our stories, and being able to control the narrative in the world we share with the culture.

How was it filming the “No Risk Involved” video? Did you have a vision for how you wanted it to look?

It was amazing. I definitely felt back in my element while performing on-screen. The positive energy and hard work by everyone on set was the difference-maker. I feel like that energy shines through the video. I’m so grateful to have had such an amazing cast and crew, they fucking killed it. As for the concept, NRI was one of the very first concepts I started developing with my team. Had my first meeting with Angelica Milash, the director of the video, and everything clicked. The inspiration was drawn from aesthetics you’d see in legendary Hong Kong movies like Young & Dangerous. We also based the female looks on different characters from movies that included Asian characters with exaggerated Asian female stereotypes.

youtube

You once tweeted “I love good music but when an artist can pull off a great visual it tells you a lot about that artist.” Do you think it’s important for artists to be active creative directors in the videos they come out with?

Personally, I love dipping my fingers in every pot when it comes to my creative direction. I believe it takes a strong team in order to create beautiful shit, and, as the artist, I want to lead the team to victory. If one of us wins, we all win. Being active as a leader is what’s important. Sharing ideas, and building with the people around you. That’s how the best ideas shine through. You just gotta be a leader with this shit. Take control of your vision and work together to execute. If you aren’t paying attention to every aspect of your craft, you’re only going to see one perspective. At the end of the day, no one will execute your own ideas better than yourself. We all have that capability.

Your newest single “Akira Harakiri” is inspired by the 1988 cult cyberpunk film Akira. How did this iconic anime influence your lyrical and production process?

I wanted the essence of the track to emulate the same essence of the movie. The production was what sparked the idea. Colin Munroe was working on the beat while we bounced ideas around and I instantly felt the beat belonged in an anime. Akira was an automatic click. This song is supposed to feel like a song The Capsules gang would bump around Neo-Tokyo. I loved the dynamic between Kaneda and Tetsuo in the film, and wanted to combine the charisma and poise of Kaneda with the maniacal energy of Tetsuo. That’s also something I want to tap into on the visual component as well. This song is an homage to a visual masterpiece, as well as an iconic moment in film and culture.

What are some of your favorite anime films?

I grew up watching anime on TV like Dragonball Z, Yu-Gi-Oh!, Pokémon, Digimon. As I grew older, I wasn’t exposed to as much as before, but I rediscovered my love for it in high school when I binge-watched Death Note twice in succession. Now I’m trying to watch as much as possible. I feel like I have so much to catch up on lol.

What are some of your goals for 2020? Both as an artist and as a human being?

I want to work on killing the urge of having a cigarette or vaping again. I quit at the end of 2019, and started working out four times a day with my trainer. I’m trying to stay consistent in doing my laundry but that shit fucking sucks. I'm trying to meditate more, as I’ve recently picked up on transcendental meditation and want to keep consistent. Other than that I wanna keep dropping cool shit and repping what I know best. I wanna keep pushing myself to my limits and keep evolving. I hope people find strength in my music and I want to evoke new thought and conversation.

What can we expect to hear more of in your future projects?

More genuine energy. You’ll definitely be able to feel exactly how I felt when creating the music, from the growing pains to the gratitude. More singing too. You’ll be able to identify the spectrum of my sound, and how dynamic it is.

Who are your Ones to Watch?

I’ve been on my hip-hop shit as of late, so I’ve been bumping a lot of Kaash Paige, Fivio Foreign, The Kid LAROI and shit. Deb Never is an artist that I've been wanting to work with personally. Out of Toronto, definitely keep your eye out for Stefani Kimber. One of the most talented artists I’ve ever heard and a great human being. She’s definitely one of my top Ones to Watch artists.

youtube

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

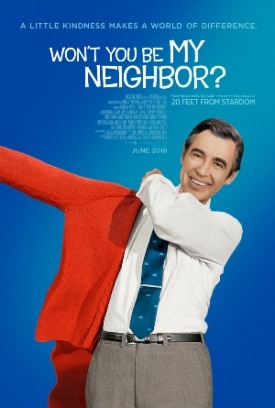

The Most Affecting Films of 2017

I love putting this list together because a.) I’m a film geek and own it, b.) this writing exercise is cheaper than therapy, and c.) it helps me discover previously unrecognized themes shared across my selections. The thread of history runs through these picks, that of nations as well as the complex and messy relationships between parents and children. History is parent to our present, and thus the thematic through line of my favorite movies of 2017. Each title brought me to tears or rented space in my mind for days after the initial viewing, often both, but earned this response through quality of storytelling.

Choosing my top ten was difficult (see the following “Runners Up List” for evidence) because 2017 was a fine year in film. We should celebrate cinema, and the opportunity to do so, as long as it remains this dynamic.

-Matt

Honorable Mention: Their Finest

Directed by Lone Scherfig

Written by Gaby Chappe and Lissa Evans

A movie celebrating storytelling and writing, chronicling the making of a movie about the Dunkirk rescue, set in England during the Blitz, addressing the role women played in the war effort, packed with an embarrassment of Britain’s best character actors, exploring how cinema’s escape can help heal us in times of crisis, and that is also a love story has no right to work. Scherfig’s film defies such limitations and hops between these aspects like a trapeze artist. It’s a crowd-pleaser, a heartbreaker, and a movie celebrating movies, all buoyed by Gemma Arterton in the lead.

10. The Lost City of Z

Written and Directed by James Gray

Cinematography by Darius Khondji

The real Percy Fawcett’s 1925 disappearance in the Brazilian jungle provides an unanswerable question that hangs over Gray’s film as he endeavors to explore mysteries of the egocentric self through immersion in the natural world. Like the protagonist, this seems simultaneously paradoxical and fitting.

Some clever non-linear editing and a final shot of Nina Fawcett, the only actual hero here, walking into the reflected image of a jungle, make for a lingering metaphor on those understandings our hearts are granted, and those we can never attain.

9. Toni Erdmann*

Written and Directed by Maren Arden

When I thought this dark European comedy couldn’t get more surreal or funny, it didn’t, but instead ends with a peerless final beat, then drops The Cure’s “Plainsong” over the credits.

Cut to me radiant with joy at what cinema makes possible.

Hollywood stories of parents and children aren’t ever this delightfully weird, or dappled with scenes that let us find our own insights about economic disparity, sexism, and capitalism’s darker outcomes. Hollywood stories aren’t ever this genuine.

Maren Arden proves herself a visionary, not just among up-and-coming female directors, but all directors, and since her open-ended final scene is perfection, I’ll let the last dialogue in her script finish the same way:

The problem is, [life is] so often about getting things done. And then you still have to do this, or that. And, in the meantime, life just passes by. But how are we supposed to hang on to moments?

* released in 2016 but I had no way to see it until 2017

8. The Big Sick

Directed by Michael Showalter

Written by Emily V. Gordon & Kumail Nanjiani

Gordon and Nanjiani’s story (based on the origin of their own marriage) took me two viewings across two seasons to relent and finally love it. Now it has my whole heart thanks to an earned emotional response and a script respecting the perspectives of all its characters. Likely the best screenplay of the year that might not be recognized as such, stand up comedy and parents are rarely revealed onscreen with such nuance, and never before in the same film.

7. Five Came Back

Written by Mark Harris (based on his book Five Came Back: A Story of Hollywood and the Second World War)

Directed by Laurent Bouzereau

This three-part Netflix documentary chronicles the contributions from five of the top directors in Hollywood during WWII, many of whom gave up lucrative careers to serve the war effort via their craft. We see how filmmaking and storytelling, as the translation of fact and occurrence through moving image, can be a weapon and should be used with care. The stories of these five directors and how their lives and art were impacted by the conflict is engagingly humane. And the talking heads (aka legendary current filmmakers) are so damn insightful. MVP being Guillermo Del Toro.

We celebrate such humanity, and in it our own, flawed and beautiful as both might be. This is best captured in Capra’s final voiceover proposing hope where it is needed.

6. Wind River

Written and Directed by Taylor Sheridan

Sheridan’s crime-as-myth story is most concerned with grief and the ways we numb ourselves to pain at the cost of the memories of loved ones lost. Winter and the West stand in a neo-western backdrop where he colors the idea of how struggle can hollow out even the strongest among us.

We get our genre kicks in the Mexican Standoff shootout (praise to the screenplay-rulebook shredding use of editing and a flashback to set up this reckoning). The patience in ending his film with not one but two conversation scenes shows a preference for empathy over spectacle, and the way the injured souls connect therein haunts me.

5. Three Billboards outside Ebbing, Missouri

Written and Directed by Martin McDonagh

I enjoy being challenged by a film. McDonagh’s picture beat the shit out of me then tossed me a lollipop, and I beamed like a lovestruck idiot. An early reference to “A Good Man is Hard to Find” alludes that that there will be no predominant tone to cling to but instead a vacillation of many throughout this winding trip into darkness where any good that exists is a miracle. In the final scene and sublime character change of Sam Rockwell’s Officer Dixon, it does.

4. Blade Runner 2049

Directed by Denis Villeneuve

Cinematography by Roger Deakins

There wasn’t a more thoughtful film this year than Deakins’ visual magnum opus. The intelligence expected of Villeneuve surfaces throughout in beautifully complex questions about life, witnessing, and how we achieve our sense of identity.

The choice of Gosling’s K / Joe as protagonist, his illusory sense of importance as the “one” and what is done with this concept, shows how important it is to value the willingness to make choices, even when they seem tiny and tossed into the void. In Joi, he may have found a facsimile of love, or he may have actually found it. In response, we question our right to declare another’s life or love “artificial”. The Hero’s Journey archetype is so common that it’s almost instinctive. Villeneuve subverts these expectations by stripping heroic action to its purest and leaving us with K / Joe’s not-tears in the ashen snow.

The acting is typically strong because, while he isn’t noticed for it, Villeneuve always gets strong work from his actors. Through one of Harrison Ford’s best performances, the theme of parents, children, and sacrifices made just for the latter’s prospect of a better life is most poignantly rendered in one line: “Sometimes to love someone, you got to be a stranger.” As 2017’s best sympathetic villain, Luv doesn’t possess the freedom of her inferior replicants; she is bound to Wallace, a slave in her programming. Wanting to be special, to be the “best one”. This denied want and inability to make her own choices, to create life and be alive, warp her into a destructive force seeking to stomp out anything that reminds her of her chains. Leto’s megalomaniac Wallace is a god-aspiring big bad in the Greek chorus role, showing up to voice the film’s themes but in a way that avoids ponderousness.

I could write an essay on this film. (Note to self: write more essays on films.)

3. Lady Bird

Written and Directed by Greta Gerwig

Gerwig’s work is so accomplished that my mind boggles when contextualizing it as her first directed film. The movie world exists here as specific enough to leap outside of time and place in that mysterious dynamic of singular-becoming-universal. Coming of age stories with comedy draped around them, or them around it, are usually judgemental of broad supporting characters who get portrayed in one shade only. This film is so balanced and sympathetic to its people, and I say “people” with intention, that we turn from cursing them to pitying to loving as fluidly as we do from laughing to choking up. The final sequence might be the year’s most affecting editing through a use of different characters in essentially the same shot, and shows that car chases have nothing on cross-cutting between drivers in the Sacramento magic hour.

2. Columbus

Written and Directed by Kogonada

Sheila O’Malley in her Rogerebert.com review:

"Columbus" is a movie about the experience of looking, the interior space that opens up when you devote yourself to looking at something, receptive to the messages it might have for you. Movies (the best ones anyway) are the same way. Looking at something in a concentrated way requires a mind-shift. Sometimes it takes time for the work to even reach you, since there's so much mental ballast in the way. The best directors point to things, saying, in essence: "Look." I haven't been able to get "Columbus" out of my mind.

Wholeheartedly agreed. It clung to me. First time director Kogonada gives us an immaculate use of the frame and mise en scene. My eyes wanted desperately to eat the screen, each and every frame a morsel. And my entire being wanted to remain in the film’s world. Sadness and all.

Kogonada’s work isn’t all visual gloss but uses stillness and subdued conversations to belie an emotional tempest inside each of the two characters. This is a romance, but one just as in thrall with life as it is with clean modernist lines and the creation of form through negative space that here symbolizes those unknowable aspects of Jin and Casey (Haley Lu Richardson lights the screen in my favorite performance this year), and by extension those they love. We carry our parents with us just as these buildings carry their histories. Columbus’ characters need to navigate the empty spaces in and around themselves to connect, even if fleetingly.

1. Dunkirk

Written and Directed by Christopher Nolan

Cinematography by Hoyte Van Hoytema

Score by Hans Zimmer

I can rightfully be called a Christopher Nolan fanboy, but there’s no arguing the viscerality of this experiment. Nolan, Hoyte Van Hoytema, Hans Zimmer, and the rest of their collaborators crafted a singular war film that really isn’t a war film. It’s a story more existential. Time is elided, shattered, and edited with an exactitude that comments on history unlike any other movie in this genre.

That audiences responded to a story asking them to participate, emotionally and physically, but learn little of its characters is also fitting for the theme of people choosing to risk their own well being for the betterment of others. The lesson is to put aside your wants and let an experience take you.

The propulsive score, like the tension, never relents. How such induced anxiety can be thrilling is for later study (and this film will be studied for decades hence). It’s the notion, however, that I can be brought to tears by the shot of a Spitfire coasting across sky, out of gas but not fight, by small boats dotting the sea that are referred to as “Home”, and by Mark Rylance simply nodding to his son in acknowledgement that the right thing to do is often an act of empathy running against our in-the-moment emotional surge, that belies an elegance words can represent, but only sound and image can actually invite you to feel.

_______________________________________________________________________

We are born into a box of space and time. We are who and when and what we are and we're going to be that person until we die. But if we remain only that person, we will never grow and we will never change and things will never get better.

Movies are the most powerful empathy machine in all the arts. When I go to a great movie I can live somebody else's life for a while. I can walk in somebody else's shoes. I can see what it feels like to be a member of a different gender, a different race, a different economic class, to live in a different time, to have a different belief.

This is a freeing influence on me. It gives me a broader mind. It helps me to join my family of men and women on this planet. It helps me to identify with them, so I'm not just stuck being myself, day after day.

The great movies enlarge us, they civilize us, they make us more decent people.

-Roger Ebert

_______________________________________________________________________

Promising 2017 releases that I haven’t seen yet and might vie for retroactive inclusion on either this or the “Runners Up” list:

Star Wars: The Last Jedi

The Disaster Artist

Darkest Hour

Mudbound

First They Killed My Father

Spielberg

The Post

Molly’s Game

Phantom Thread

The Shape of Water

1 note

·

View note

Text

mother! A Dark Allegory Sacralizing the Relationship Between Religion and Secularism

My vitals are oatmeal, my brain is slain, my soul is recovering from the syringe-injected wtf emotion. I haven’t been this excited since Aronofsky’s last release, NOAH (2014). And BLACK SWAN (2010) before that. And THE WRESTLER (2008) before that. And…you get the point. I’ve been team Aronofsky from the beginning (Sundance 1998, where he debuted PI). And, like all of his films, I’m destroyed in the most cathartic way as the credits roll. I’m reveling in the darkness of this feeling, this theater, paralyzed with intense awe. I have strong hope there’s light dancing somewhere inside my marred head, guiding me through the fiery, hellbent tunnels of what I just experienced. And MOTHER! is an experience!

What an absolutely sickening, messed up, brilliant cinematic masterpiece!!!!

Here is a film that only Aronofsky could’ve made, a film that contains a motherlode of rich interpretations, a symbolic maelstrom of ideas needing to be painfully birthed. The imagery stains, the ideas baffle, the third act impossible to predict, stomach, or prepare for. Believe me when I tell you: The barbs are real. And it makes for an ultra provocative kind of art because it’s so vulnerable, so sprawling, relevant and contentious in its reach. I might even describe it as a scalpel-sharp metaphor that rips, grinds, and eviscerates every faction of humanity ever to exist. No one is safe. Everyone is indicted. And Aronofsky, like the God of Genesis, is pissed with everyone, pissed with creation, pissed with politics and religion, with the overall state of the world, and he’s ready to burn it all down and start anew.

It’s a film that kind of plays out like NOAH — its prequel and sequel—but replaces the watery deluge with apocalyptic fire. It uses a biblical framework to shape and express a lot of political and humanitarian turmoil, and wraps them all together into one grand, outrageous, cyclical metaphor that might be difficult to grasp without a solid backing in these subjects.

MOTHER! isn’t a political or religious film per se as it is a human film commenting on the state of the world and how we endlessly abuse it. It evokes political and religious overtones to the extent of retelling the creation myth from a gnostic, secularized perspective. It’s also about a lot of other things — the social dynamics between artist, muse and feasting fandom, the creation of art itself, the downfall of civilization, of ecosystems, of human safety, the obsession with social media, tabloids and selfies, the portrait of a decaying marriage, the dangers of open-mindedness, and the list goes on. The interpretations will be myriad.

I found its retelling of the creation myth, however, one of the most moving, cross-pollinating attempts to ever sacralize the warring relationship between religion and secularism.

That retelling might go something like this:

The Earth — our world — is feminized, a Mother to all, a source of both nourishment for humanity and victim of male aggression.

Man’s aggression spawns from greed — from His dominion over Her (the Earth) — thereby becoming a catalyst for His belief in His dominion over Woman.

And so as the Earth is mastered, conquered, penetrated, plowed, tilled, burned, subdued, inhabited, and controlled, so is Woman.

Her paradisiacal garden is turned to waste, but Man continues to plant and labor and sow, and by brute sweat makes Woman yield — conceive.

The Earth — the Mother of all — “gives and gives and gives,” and in return gets invaded, pillaged, and raped, rebirthing the vicious cycle.

And Mother bears it, endures it, braves it, serves it, puts up with it.

Cruel male pagan gods divine this link between Mother and Earth, they gaslight it, and allow for the problem of evil to run amok for the sake of artistic musing and divine retribution for sin.

We’ve seen Aronofsky’s pagan sensibility shine before in BLACK SWAN, where anything that manifests itself to you may be a god, but in MOTHER! this paganism pulses and groans under the weight of what I found were five highly potent, timeless, relevant-in-2017 themes:

1) Mother, as an earthen vessel, holds the seeds to every noxious, selfish, unbending human crime within Her.

2). Mother, as an earthen vessel, may be pillaged, raped, and controlled by Man through “divine” rights, even corporation rights, unleashing the revelations and purgatories within Her.

3) Mother, as an earthen vessel, births, feeds, rears, nourishes, and puts up with a lot of vile, inane, intruding human garbage.

4) Yet Mother, even as this earthen vessel, can reach a furious, volcanic melting point, a chamber that can no longer contain the scalding pressure inside, exclaiming:

(!) “Enough!” (!) “No More!” (!) “The End!” (!)

5) Yes Mother! now as embodied, apocalyptic fury, can reject crude male taming and savagely roar back and boil over with destructive, unmatched chaos.

These themes stretch towards the sacred and the profane equally, finding home within the religious and irreligious alike. It’s a brand of home invasion horror that’s critical now. A story about our world bellyaching, roaring, reaching critical melting point — now! And what’s fascinating here is how Aronofsky transfers his past auteur portraits of hysteria and madness (think PI, BLACK SWAN, NOAH) over from his characters now suddenly to the lap of his audience. This will hit very close to home, and many will feel uncomfortable. In fact, the film almost plays out like Aronofsky’s middle finger to humanity at large, a venting frustration at how we mistreat each other and abuse our sacred, mother planet.

The result? Piqued reactions, confused reactions, zero neutrality, shifting accountability, and above all, a puzzle to be ciphered and querulously debated for years to come. This is the BEST kind of art. The kind that divides yet hopefully unites. It certainly is one of the most moving, thought-provoking films I’ve ever seen, one that hits personally close to home. I say this especially as a devout theist who leans on the side of a culturally religious agnosticism.

While this experience won’t be for everyone, I’d argue there’s a moral blade to the film that cuts DEEP, DEEP, DEEP into a problem that everyone is complicit in, right and left, black and white, male and female, me and you, but it isn’t necessarily preachy or scorning in presentation. Ok, it’s seriously messed up. But I reject any reading that claims Aronofsky is a misogynist or without compassion — especially for Jennifer Lawrence’s character — in part because this posture entirely misses the point by disguising a surface criticism as one that ignores the film’s larger, looming global symbolism, and the mighty realities for which those symbols stand.

MOTHER! might be the kind of art that liberals love to hate because some are unable to fathom how bad things being depicted is not equivalent to bad things being endorsed, but merely commented, mourned and reflected on. You need look no further for evidence of this than when Javier Bardem stated in an interview with USA Today, “Darren is the opposite of my character…He’s more into Jennifer’s character than my character. When I met him, I was like, ‘Where is this darkness coming from?’ Because he is the opposite of that. He’s nice, caring, generous, funny, very creative.”

MOTHER! has a moral edge to the extent that it forgoes pleasure, or punishes it wherever it occurs, to deliver a higher message. And my reaction to the film was one of total compassion, like a surgeon cutting into rotten tissue to find what parts are still salvageable. Put differently, Aronofsky plunges DEEP, DEEP, DEEP into darkness in order to find what shards of light may be hiding there, a skill he has always excelled at. His canon of work has proven how repeatedly and exceptionally acrid his ability is to peer into the abyss to yield enlightenment. And to make great art you have to go to the darkest place, the forbidden place. MOTHER! raises this cost as an insanely moving, nuanced presentation of what happens when you stare into the abyss — the forbidden place — too long.

If REQUIEM FOR A DREAM is Aronofsky’s required viewing for D.A.R.E programs, MOTHER! is his required viewing for earth stewards and married couples. If NOAH is Aronofsky’s biblical making of Genesis, MOTHER! most certainly unleashes his apocalyptic, unmaking, hellfire vision of Revelation. If PI is Aronofsky getting into the confined, mentally ill space of his characters, MOTHER! is him flipping that headspace burden over to his audience. If BLACK SWAN is Aronofsky doing hysteria-horror, MOTHER! is him making BLACK SWAN wishing it were difficult material for Sunday School. If THE FOUNTAIN is Aronofsky’s metaphysical view of history, MOTHER! is him exclaiming there won’t be any history left if our course goes unaltered.

And Aronofsky was right: No matter how many trailers/snippits I read prior to watching, NOTHING could prepare me for this sacred, unholy event. NOTHING! And don’t worry, my take here won’t spoil the madness you, too, will be put through (assuming you dare to step inside his theater!). And the third act. Good sweet mother Mary of all things blessed and disturbing, the third act! Good hell. Can’t wait to follow #mothermovie on that one. In sum, I’ve never seen anything like this. Will never be the same again. And will never answer a door knock again. Thanks a lot Darren.

#film#film critique#religion#philosophy#spiritual#politics#divine humanism#film nerd#poetry#darren aronofsky#allegory#bible study

9 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

Tangerine (2015) dir. Sean Baker

A Trans Woman of Color Responds to the Trauma of “Tangerine”

Why is it that trans women of color have to experience so much violence to remember that they have each other’s back?

That’s what I got from the movie Tangerine. I enjoyed it. Mya Taylor (who plays Alexandra, one of the two trans leads) and Kitana Kiki Rodriguez (who plays Sin-dee, the other) were fucking brilliant. They were not respectable, they were surviving in the best way they knew how and they were supporting each other even though it was difficult. I loved that they didn’t apologize for their lives or their existence.

Despite this, the audience still laughed at really inappropriate parts, showcasing the way that the film itself fails the story it’s trying to portray. And don’t get me wrong, the story is real. But the way it’s set up, how it’s shot, the progression of the plot — it’s clear that it is offering up the story to a mostly white, bougie audience. It was voyeuristic in the worst possible way. And while the two stars did have a lot of input into the making of the script, white men are still the ones who get the credit. The names of white men are on the script and white men directed the movie. The story was only made real by the beautiful performance of the actors.

One of the things that frustrated me was the way Razmik (an Armenian taxi driver who is a frequent customer of Alexandra and Sin-dee, played by Karren Karagulian) is juxtaposed to that terrible john. Razmik is no better then the dude that tried to rip off Alexandra. But the narrative manipulates you into feeling sorry for him. He is just a poor misunderstood dude who lies to his wife and keeps his desire secret. But he was just as awful as all the other non trans women in the film. He reduces trans women to what we can do for him sexually, fetishizes our bodies and refuses to publicly acknowledge that he desires trans women. He is still exploits them — he just pays well. Whats more, I don’t care at all about men and how they’re impacted by transmisogyny. Because the only reason Razmik and men like him get any kind of grief is because of transmisogyny. But it is not men who bear the brunt of that violence, it is us. Trans women are murdered for the same reasons that men are shamed. So for this film to focus almost half of the narrative on this man and how hard he has it, is very frustrating. Because even in films that are ostensibly about us, we still have to deal with men and their feelings. We still try to center male experiences.

The complicated relationship that these two trans women had with the men/love in their life was hard to watch. These were people who really and truly hated Sin-dee and Alexandra but said that they love them. They manipulate, take advantage of and abuse them. Chester was an awful abusive liar, but what choice does Sin-dee have? When validation and love come, even if it’s twisted and fucked up, you take it because otherwise you are just alone and sometimes the illusion of someone supporting you is better than nothing at all. I saw my experiences with men reflected in theirs and it fucking hurt. Trans women of color aren’t valued — again, we exist only to serve and perform for men. What does it mean that the people that are supposed to value us the most end up abusing us? What does it mean that trans women of color are often the victims of domestic violence but there is no narrative about it. We cannot be victims because we cannot be loved.

The final moment of the film comes after Sin-dee realizes that Alexandra slept with her boyfriend. Sin-dee is upset with Alexandra and tries to go off by herself but Sin-dee is assaulted, called a tranny faggot and gets urine splashed all over her. An intimate moment ensues where Alexandra takes care of Sin-dee and Sin-dee forgives Alexandra. That moment of sisterhood is so real. Nobody is going to look out for trans women of color except other trans women of color. We only matter to others when we are performing for them. But why does the film find it necessary to emphasize this sisterhood by subjecting them both to violence? What does it say about the director and the audience that this was the only way to bring them back together, because they have no other choice because the world is trying to kill them. This scene also shows them taking off their wigs which is just another instance of that trope saying that trans women’s femininity is not real. It’s a fabrication that comes off during intimate moments, cause what’s “real” is what’s on the “inside”. What does it mean that all the character development that occurred in that film was through trauma and violence? What does it mean that we can only see their vulnerability, their strength, their resilience through this moment of degendering?

I’m glad I went to see it. Seeing some of my experiences reflected in that film were really important and some of the ways they handle sex work and relationships is real. I appreciated the nuance in the way that they displayed men and their relationships to trans women. Trans women of color are almost always seen as objects to be controlled, held and exploited. The movie was clear about this. Clear that the ways men relate to trans women is toxic and fraught with dynamics of power that are abusive. Chester (Sin-dee’s boyfriend and pimp, played by James Ransone) was terrible to Sin-dee and he manipulated his way back into her good graces. Razmik was only interested in how these women could serve his pleasure. Both models — both through intimate relationship and client — capture the way that men are terrible to trans women time and again.

I also liked the way that Sin-dee was in control of her interaction with Dinah (the white, cis woman and sex worker who Chester cheats on Sin-dee with, played by Mickey O’Hagan). So often, cis white women will invalidate our womanhood. They will exclude us from women’s spaces and be generally awful to us. Transmisogyny is pervasive and cis white women are not exempt from perpetuating that. It was satisfying to see another trans woman of color in control of her interaction with someone who was actively denying her womanhood, who mocks Sin-dee’s desire to be valued and seen by her partner. It was satisfying to see her take what she needed from her when so often trans women of color are denied. White feminists might be inclined to read what Sin-dee does as violence against women but Sin-dee is not in a position of power over Dinah. And it was satisfying to watch. And while I do not trust the intentions of the white male director who shot that scene (because he would be perpetrating that violence), I do appreciate the moment for the satisfaction it gave me.

Even with these positive experiences, the voyeurism and almost lurid lens that the film was shot in makes it so that it only serves the consumption of cis white people. I cannot separate or ignore the fact that this was a film made by white men. And how these white men’s careers are going to profit from this film while the actress’s careers will most likely languish.

And why is it that so few TWOC (aside from Laverne Cox and Janet Mock) get any kind of airtime when it doesn’t involve trauma? Why are cis folks only interested in seeing us hurt, traumatized and alone? Those select few trans women who do get the spotlight, not just when they are murdered, are the exception and often tokenized by the spaces that they are in. You only ever hear about TWOC after we have been murdered. And in many ways this film is no different. It relies on the difficulty of our lives, it’s fetishizes the way our existence is marked by this world in order to titillate, to entice. The exotic other enchanting the “normal” cis white audience. And they leave the theater thinking that they know something, that they are more familiar with the lives of trans women. But our lives are not like in the movies.

After the last shot and the credits started rolling, I just broke down and cried. All that trauma and pain laid out like that so that people who don’t give a fuck about us, who just want to eat us alive — it was too much. It was so much to be in that audience, hearing their laughter and knowing we are just some fucking joke to them. That the things we face are a fantasy playground they can hang out in and then leave. That our lives only have meaning through the trauma experience. And don’t get me wrong, our trauma is real. But trauma isn’t the only thing about my existence that is real. But it’s the only thing cis folks care to see. Because a trans woman happy and loved is just so fucking weird to be real. Because seeing the full breadth of our lives is too much for people to handle. And because white people cannot help but exploit our lives.

In many ways, this film is similar to Paris is Burning. Brilliant and important and life saving while at the same time exploitative to the actors/subjects. The reviews of this film go on and on about Sean Baker and how he shot this film on a iPhone but where are the interviews asking how Mya Taylor felt shooting this film? Where are all the accolades for Kitana Kiki Rodriguez and her beautiful nuanced performance? Jennie Livingston made out like a bandit from that film and so will Sean Baker from this one. And the system is set up that only a white person could even get the funding for this project. TWOC doing this for ourselves doesn’t get the same level of attention or money. When will we get our coins? When will the work we do, the art we make, the lives we lead be for us, by us? When will white cis people stop exploiting our bodies for their profit?

https://www.autostraddle.com/a-trans-woman-of-color-responds-to-the-trauma-of-tangerine-301607/

0 notes

Text

2018 Favorite Movies

It’s been a while since I’ve made one of these lists. This year was filled with great foreign films and documentaries, as (spoiler alert) you will see many of below. As always, I have not seen every movie of the year, but I think I have gotten better over the years at understanding what kinds of movies I would find interesting, and what directors I will always look out for, so in that regard, I think I have been as exhaustive as I can to make this list.

Honorable Mentions:

The Ballad of Buster Scruggs: I’ll watch anything the Coen’s do, and if history suggests anything, I’ll probably like it. This is one of the most unique formats I’ve seen a Coen film (anthology), but I’m glad I got to see their take on this film format, because I do enjoy films like this (Paris, Je’Taime, and Wild Tales are two of my favorites). This film did a good job of keeping with the overall western theme they were going for, even if some of the stories were more engaging than others. The timings were a little uneven as well, as some stories were (and felt) longer than others, which kind of threw off the pacing and rhythm of the film. If I know the Coen’s though, they might not be done exploring the genre of the Old Western.

Green Book: One of the more “meh” best picture winners of the past several years, maybe since The Artist. Viggo Mortenson did a great job and the chemistry between him and Mahershala Ali felt authentic, but I wish there wasn’t so much cheese spread across the film. I wish I could have a caution sign that pops up in front of a director’s eyes before they shoot a scene, reading: “Does this scene require this much drama (cheese) to effectively move the plot or build upon the character(s) in an appropriate manner? If it is not a resounding YES, please RECONSIDER altering the scene to be more authentic!!” I’m rambling and may be piling on this movie for the shortcomings of a lot of Oscar “bait,” but I (and many others) see it every year and every instance of it gets more and more frustrating.

They Shall Not Grow Old: War documentaries are nothing new, but I was thoroughly impressed by this take on the documentary format by Peter Jackson. I highly recommend sticking around to the very end of the film (after the credits) to see a mini-documentary on how they made the film and their thinking behind the structure, layout, and overall design of the film. The amount of work they put into the project is even more apparent after seeing that, and it just underscores the grand scale a world war was.