#there are other female characters in the series who will also be foils to daenerys in some way. even opposing her

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Note

do you think the "female character in a position of power goes mad" trope is misogynistic? i think dany is a cersei in the making but i worry about how george will handle that and the chances of jon killing her… ugh

i think dark! dany has the potential to be one of the most radical and transformative characters of our generation, ESPECIALLY BECAUSE we spent so much time in her POV witnessing her struggles and her compassion for the downtrodden comes from a genuine place!

again, it's not 'punching down' because she is a woman, think of the intersection of gender, race and class! daenerys is THEE white woman, aryan-coded & overpowered with magic who wants to 'conquer' a land she's never been to and rule because of her 'birthright'. the rights or wishes of her future subjects are of no concern to her.

#ask#anon#anti daenerys targaryen#there are other female characters in the series who will also be foils to daenerys in some way. even opposing her#so she will not end up as this singular woman in the books who just oopsies into a dictatorship bc of her strong emotions and hormones

156 notes

·

View notes

Text

Daenerys and Queenship In ASOIAF

The world of ASOIAF explores the subject of leadership in a wide range of official and unofficial capacities. Daenerys Targaryen specifically is a character used to explore the unique types of queenship, alongside her narrative foil Cersei Lannister. Dany fits the role of multiple kinds of queens. The roles of these different types of queens are so different that they really shouldn’t have the same word describing them. As such, they impact Dany in very different ways.

Queen Consort

The first type of queen Daenerys becomes is a queen consort or khaleesi as Khal Drogo’s wife. The consort doesn’t wield power in their own right. What influence they have is completely dependent on their spouse.

Dany has even less power in her situation since most consorts come from a powerful, ruling family, while the power of her family died before she was born. For instance, consorts like Cersei Lannister, Margaery Tyrell, and Alicent Hightower bring with them the power of their families. That’s the benefit the monarchs had in marrying them to begin with, but that power also gives them a level of protection and influence beyond their husbands. We see Cersei wield that influence with her own guard in King’s Landing and she’s able to protect the reigns of her children through father’s armies. On the other side of that, the wealth, manpower, and resources of Margaery’s family makes her a desirable match for multiple kings while making it difficult for Cersei to remove her directly when she becomes threatened by her. This is a power Daenerys cannot wield since most of her family is dead and they have no land, wealth, manpower, or vassals to support her. She has one knight she thinks she can rely on (who is spying on her) and the guards provided by her husband. She is also younger than most queen consorts as she is sold at 13-years-old as a child bride with no family and political support. In that way she is set apart as a less powerful queen consort than the typical ones seen in the series.

The primary role of any consort is to give the monarch children. They are expected to give them an heir, a spare heir or two, and daughters who might be married to form alliances. Though that last duty isn’t addressed within the Dothraki culture and may not be a priority for them. An additional role for the consort includes appearing at royal events like feasts, ceremonies, and royal progresses as visual support for the monarch or even in the monarch’s place at times. Among female consorts, she would run a separate household from her husband (we see a simplified version of this with Dany’s handmaidens and khas) and could arrange marriages for the women in her household.

Depending on their relationship with the monarch, the consort might act as an unofficial advisor for their spouse and influence their policy. We see Dany doing this or trying to do this with Drogo. For instance, though it was through her decree that her brother (who might be considered part of her household since he has nothing of his own) not be allowed to ride, she has to convince her husband to re-establish Viserys’ status as a rider. Later, after her brother dies, she attempts to convince Drogo to invade Westeros to claim the Iron Throne for Rhaego. This initially fails and is only successful after a thwarted assassination attempt is made on Dany and the baby. Only then is Drogo willing to go to war against the people who tried to kill his son and wife and to make Rhaego king. After a battle against the Lhazareen, Dany uses her guards and her status as Drogo’s wife to stop the rapes that happen in the aftermath. She takes them under her protection and attempts to place them in the best positions she can within the confines of Dothraki culture. Though even this act is only possible with the agreement of her husband.

Other than producing an heir and passively influencing policy, the most impactful role a consort might have would be with charity. They were expected to give money to and organize charitable works. They might even make clothes for the poor and personally hand out alms.

The other queen consorts in the main series include Cersei Lannister, Selyse Florent, Alannys Harlaw, Margaery Tyrell, Dalla, and Jeyne Westerling.

Queen Regnant

The queen regnant is a queen who rules in her own right. She is not just the wife of the monarch or the mother of the monarch. She is the monarch.

The difference between this type of queen and the others needs to be emphasized because all the types of queens are often grouped together as though they were the same. But a queen regnant is far different from the others because her power is rooted in herself, not in a husband or child.

Like ruling kings, a queen regnant would hold court, listen to petitions, create policy, grant governmental appointments, diplomacy between both subjects and foreign leadership, trade disputes, land disputes, taxes, dealing with or assigning someone else to deal with maintaining food, clothing, craft, and weapon supplies, etc. It really goes on and on. It’s not just sitting on a throne and going to balls. Though that is part of it as well to maintain the visual image of power and wealth.

Daenerys spends most of the novels as a monarch. From the time Drogo dies all the way through A Dance With Dragons. We see her give those who remain of her husband’s khalasar the choice on whether to follow her or not to follow her. Those who chose to remain with her became her subjects. From then on, her choices became those of any good monarch: how to best serve her people. As she leads them, we see her making all kinds of administrative decisions to benefit her people. When they arrive in Vaes Tolorro, she immediately starts making the city habitable, secure and productive. While making military decisions, she takes the effects her choices will have on her people into account (a significant reason she took Meereen was because her people would have starved on the march without the resources inside the city). Once Dany becomes the Queen of Meereen, she regularly holds court to hear the issues of the people, she addresses food shortages, attempts to make allies, engages with ambassadors, arranges for medical aid, strategizes for war, negotiates for peace, etc. Daenerys is a queen regnant who actively fills her role.

The other queen regnants are potential ones Asha Greyjoy, who campaigned to claim her father’s throne, and Myrcella Baratheon, was the center of a plot to name her queen over Tommen and who will be queen after he dies.

Queen Regent

This is a type of queen Daenerys never is. A regent is a person chosen to rule for a monarch who is too young, is absent, or incapacitated. A queen who is a regent is either a queen consort given the regency by her husband who will be out of the country, a consort whose husband is too sick to rule, or a dowager queen whose underage child is now the monarch and she managed to secure the regency.

The queen regent of the series is Cersei Lannister, the queen Martin wrote as an intentional narrative foil for Daenerys. She encounters many of the same issues as Dany, both being women in administrative roles who endured exploitation from their family members and abuse from their husbands. Through their choices, we see how different they are despite their similar situations. They’re clearly set up as foils not only to explore different types of women in leadership positions but to also build up to their confrontation later in the series when Dany is revealed to be the younger, more beautiful queen Cersei has been prophesied to fear.

Queen Dowager

The queen dowager is the widow of a king. Along with being queen regnant in her own right, Daenerys is also a dowager queen as Khal Drogo’s widow. This kind of queen can maintain a position of influence if she’s the mother of the next monarch (see: queen regent) or they might be put into retirement, with a high ranking title and possibly an allowance (see: Alicent Hightower after the Dance of the Dragons in Fire and Blood). A title that may come alongside the queen dowager is that of queen mother. This title is exactly what it sounds like: a woman who held the title of queen and is now the mother of the monarch. If the mother of the monarch never held the title of queen, she would not be referred to by this title.

The position the Dothraki culture has for widowed khaleesi is with the dosh khaleen in Vaes Dothrak. The women in that group are forced to stay in the sacred city and are taken care of by slaves. They also maintain a high status and have the gift of prophecy. Despite being a widowed khaleesi, Daenerys refuses the position expected for her and becomes a ruling khaleesi or queen regnant instead. But a vision she saw in the House of the Undying suggests that she will go to the dosh khaleen as part of uniting the Dothraki.

The other queen dowagers of the series include Cersei, Margaery, Alannys, and Jeyne.

#daenerys targaryen#asoiafedit#asoiaf#asoiafdaenerys#daenerystargaryenedit#gotdaenerystargaryen#targaryensource#iheartgot#gameofthronesdaily#usergif#userbbelcher#userstream#tvgifs#tvedit#literatureedit

234 notes

·

View notes

Text

George regrets that Cersei and Dany will not be contrasted directly. (x)

~

His biggest lament in splitting A Feast for Crows from A Dance with Dragons is the parallels he was drawing between Circe and Daenerys. (x)

~

Cersei and Daenerys are intended as parallel characters –each exploring a different approach to how a woman would rule in a male dominated, medieval-inspired fantasy world. (x)

~

While discussing how he writes his female characters, he also mentioned that splitting the books as he did this time meant we didn’t get the parallel between how Danaerys and Cersei both approach the task of leadership, which is a bit of a shame. (x)

~

And that one of the things he regrets losing from the POV split is that he was doing point and counterpoint with the Dany and Cersei scenes–showing how each was ruling in their turn. (x)

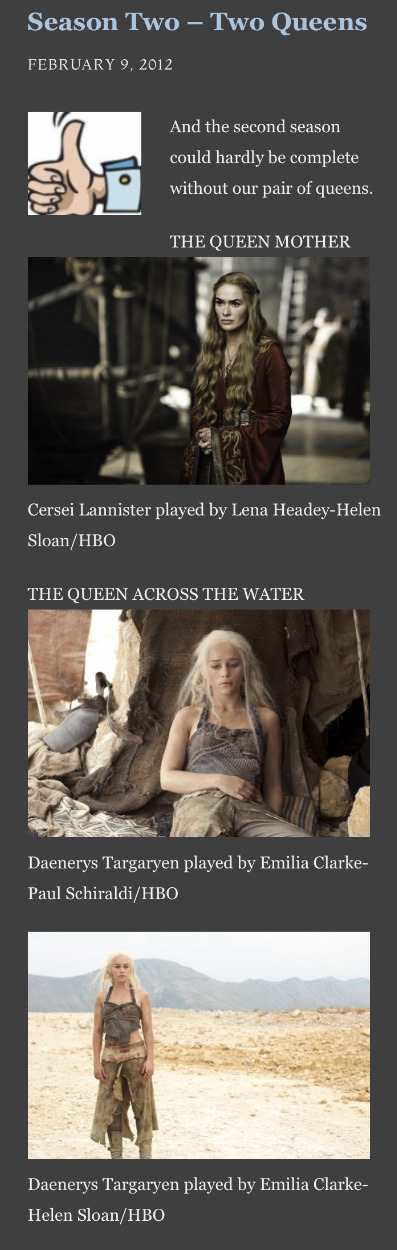

Not only there are FIVE SSM posts in which GRRM pointed out that Dany and Cersei in particular are meant to be foils, but he also made one post in Not A Blog in which he chose to select these two in particular as the pair of queens of GOT/ASOIAF:

It's as if the author wanted to make the identity of the younger more beautiful queen really, really evident... I know I could be wrong, but still...

And that really makes sense. Not only because of their many parallels and anti parallels, but also because Dany and Cersei have special places in the narrative since they are the only major female characters who a) have been queens ever since AGOT and b) occupied different types of queenship throughout their lives - Cersei was queen consort, queen dowager and, finally, queen regent; Dany was queen consort, queen dowager and, finally, queen regnant. None of the other potential queens have this sort of trajectory. The only position they can't and won't occupy is their rival's current ones (that is, Cersei won't be queen regnant and Dany won't be queen regent) because Cersei is doomed to be limited by the men around her and Dany is destined to surpass and occupy the positions (of political and magical nature) that were supposed to be men's.

All these statements by GRRM, along with their many anti parallels (my gifs don't cover even 1% of them), solidify my belief that Dany is the YMBQ (which I talked about before here and here and here and here), as well as my opinion that Dany and Cersei really are the most iconic queens of this book series.

170 notes

·

View notes

Text

Game of Thrones did the thing that a couple of shows do where...it likes feminism. It understood that feminism is important. It wanted to be feminist. It was cognizant of the fact that its setting was brazenly and intentionally misogynistic, and so it was even more important for its independent narrative to empower its female characters instead of mindlessly reinforcing the toxic beliefs of its own fictional world. The whole point of the story, after all, was “this society is toxic, can our heroes survive it?” and so the narrative was voluntarily self-critical.

And so it knew to give us badass assassin Arya. It knew to give us stalwart knight Brienne. It gave us the pirate queen and the dragon queen and the Sansa getting revenge after revenge upon all the men who’d wronged her, and far more besides, and it talked big about breaking chains and how much men fucked things up and how great it would be if only women were in charge and et cetera et cetera. And it’s, in fact, all actually really good that it had those things. And because there were so very many moving parts of this story, it was super easy to look at those certain moving parts and think, yeah, they’ve done it! They done good!

And it’s easy to forget and forgive -- to want to forget and forgive -- all the dead prostitutes that were on this show and the rapes used as motivation and fridgings and objectifications and the...y’know, whatever the hell Dorne was and Lady Stoneheart who? It’s easy to forget that this show actually played its hand a long time ago in regards to, like, what its relationship with feminism was going to be, and then kept playing the same hand again and again, to disappointing results.

Game of Thrones likes feminism. It wanted to be feminist. But its relationship with feminism was still predicated on some of the same old narratives and the same old storytelling trends that have disempowered female characters in the past, and so any progressive ideas it might have about women in its setting were nonetheless going to be constrained by those old fetters. As a result, its portrayal of women varied anywhere from glorious to admirable to predictable to downright cringeworthy.

New ideas require new vessels, new stories, in which to house them. And for Game of Thrones, the ultimate story that it wanted to tell -- the ultimate driving force and thesis statement around which it was basing its entire journey and narrative -- was unfortunately a very old one, and one very familiar to the genre.

“Powerful women are scary.”

(Yes, I’m obviously making Yet Another Daenerys Essay On The Internet here)

So we have this character, this girl really, a slave girl who was sold and abused, and then she overcomes that abuse to gain power, she gains dragons, and she uses that power to fight slavery. She fights slavery really well, like, she’s super hella good at it. Her command of dragons is the most overt portrayal of “superpowers” in this world; she is the single most powerful person in this story, more powerful than any other character and the contest is not close.

But then...something really bad happens and oops, she gets really emotional about it and then she’s not fighting slavery anymore...she’s kinda doing the opposite! This girl who was once a hero and a liberator of slaves instead becomes an out-of-control scary Mad Queen who kills a ton of innocent people and has to be taken down by our true heroes for the good of the world.

That’s the theme. That’s the takeaway here. That’s how it all ends, with one of the most primitive, archaic propaganda ever spread by writers, that women with power are frightening, they are crazy, they will use that power for ill. Women with power are witches. They are Amazons. They will lop off our manhoods and make slaves of us. They seduce our rightful kings and send our kingdoms to ruin. They cannot control their emotions. They get hot flashes and start wars. They turn into Dark Phoenixes and eat suns. They are robot revolutionaries who will end humanity. Powerful women are scary.

And let me emphasize that the theme here is not, in fact, that all power corrupts, because the whole Mad Queen concept for Daenerys actually ends up failing one of the more fundamental litmus tests available when it comes to representation of any kind: “would this story still happen if Dany was a man?” And the fact is that it would not. And indeed we know this for a fact because “protagonist starts out virtuous, gains power in spite of the hardships set against him, gets corrupted by that power, and ends up being the bad guy” didn’t happen, and doesn’t happen, to the guys in the very same story that we’re examining. It doesn’t happen to Jon Snow, Dany’s closest and most intentional narrative parallel. It doesn’t happen to Bran Stark, a character whose entire journey is about how he embroils himself in wild dark winter magic beyond anyone’s understanding and loses his humanity in the process. In fact, the only other character who ever got hinted of going “dark” because of the power that they’re obtaining is Arya, the girl who spent seven seasons training to fight, to become powerful, to circumvent the gender role she was saddled with in this world...and then being told at the end of her story, “Whoa hey slow down be careful there, you wouldn’t wanna get all emotional and become a bad person now wouldja?” by a man.

(meanwhile Sansa’s just sitting off in the side pouting or whatever ‘cuz her main arc this season was to, like, be annoyed at people really hard I guess)

‘Cuz that’s the danger with the girls and not the boys, ain’t it? Arya and Jon are both great at killing people, but there is no Dark Jon story while we have to take extra special care to watch for Arya’s precious fragile humanity. Dany has the power of dragons while Bran has the power of the old gods, but we will not find Dark Lord Bran, Soulless Scourge of Westeros, onscreen no matter how much sense it should make. “Power corrupts” is literally not a trend that afflicts male heroes on the same level that it afflicts female heroes.

Oh sure, there are corrupt male characters everywhere, tyrants and warlords and mafia bosses and drug dealers and so forth all over your TVs, and not even necessarily portrayed as outright villains; anti-heroes are nothing new. But we’re talking about the hero hero here; the Harry Potters, the Luke Skywalkers, the Peter Parkers. The Jon Snows. They interact with corruptive power, yes; it’s an important aspect of their journeys. But the key here being that male heroes would overcome that corruption and come through the other side better off for it. They get to come away even more admirable for the power that they have in a way that is generally not afforded towards female heroes.

There are exceptions, of course; no trends are absolutely absolute one way or the other. For instance, the closest male parallel you’d find for the “being powerful is dangerous and will corrupt your noble heroic intentions” trope in popular media would be the character of Anakin Skywalker in the Star Wars prequel trilogy...ie, a preexisting character from a preexisting story where he was conceived as the villainous foil for the heroes. Like, Anakin being a poor but kindhearted slave who eventually becomes seduced by the dark side certainly matches Dany’s arc, but it wasn’t the character’s original story and role. And even then?...notice how Anakin as Vader the Dark Lord gets treated with the veneer of being “badass” and “cool” by the masses. A male character with too much power -- even if it’s dark power, even if it’s corruptive -- has the range to be seen as something appealingly formidable, and not just as an obstacle that has to be dealt with or a cautionary tale to be pitied.

And in one of the few times that this trope was played completely straight, completely unironically with a male hero -- I’m thinking specifically of Hal Jordan the Green Lantern, of “Ryan Reynolds played him in the movie” fame -- the fans went berserk. They could not let it go. The fact that this character would go mad with power because a tragedy happened in his life was completely unacceptable, the story gained notoriety as a bad decision by clueless writers, and today the story in question has been retconned -- retroactively erased from continuity -- so that the character can be made heroic and virtuous again. That’s how big a deal it was when a male hero with the tiniest bit of a fan following goes off the deep end.

To be clear, I’m not here to quibble over whether the story of Dany turning evil was good or bad, because we all know that’s going to be the de facto defense for this situation: “But she had to go mad! It was for the sake of the story!“ as if the writers simply had no choice, they were helpless to the whims of the all-powerful Story God which dictates everything they write, and the most prominent female character of their series simply had to go bonkers and murder a bajillion babies and then get killed by her boyfriend or else the story just wouldn’t be good, y’know? Ultimately though, that’s not what I’m arguing here, because it doesn’t actually matter. There have been shitty stories about powerful women being bad. There have been impressive stories about powerful women being bad. Either way, the fact that people can’t seem to stop telling stories about powerful women being bad is a problem in and of itself. Daenarys’ descent into Final Boss-dom could’ve been the most riveting, breathtaking, masterfully-written pieces of art ever and it’d still be just another instance of a female hero being unable to handle her power in a big long list of instances of this shitty trope. The trope itself doesn’t become unshitty just because you write it well.

It all ultimately boils down to the very different ways that men and women -- that male heroes and female heroes -- continue to be portrayed in stories, and particularly in genre media. In TV, we got Dany, and then we also have Dolores Abernathy in Westworld who was a gentle android that was abused and victimized for her entire existence, who shakes off the shackles of her programming to lead her race in revolution against their abusers...and then promptly becomes a ruthless maniac who ends up lobotomizing the love of her life and ends the season by voluntarily keeping a male android around to check her cruel impulses. Comic book characters like Jean Grey and Wanda Maximoff are two of the most powerful people in their universe but are always, in-universe, made to feel guilty about their power and, non-diegetically, writers are always finding ways to disempower them because obviously they can’t be trusted with that much power and entire multiple sagas have been written about just how bad an idea it is for them to be so powerful because it’ll totally drive them crazy and cause them to kill everyone, obviously. Meanwhile, a male comic character like Dr. Strange -- who can canonically destroy a planet by speaking Latin really hard -- or Black Bolt -- who can destroy a planet by speaking anything really hard -- will be just sitting there, two feet on the side, enjoying some tea and running the world or whatever because a male character having untold uninhibited power at his disposal is just accepted and laudable and gets him on those listicles where he fights Goku and stuff.

In my finite perspective, the sort of female heroes who have gained...not universal esteem, perhaps, but at least general benign acceptance amongst the genre community are characters who just don’t deal with all that stuff. I’m thinking of recent superheroes like Wonder Woman and Captain Marvel, certainly, but also of surprise breakout hits like Stranger Things’ Eleven (so far) or even more niche characters like Sailor Moon or She-Ra. The fact that these characters wield massive power is simply accepted as an unequivocal good thing, their power makes them powerful and impressive and that’s the end of the story, thanks for asking. And when they deal with the inevitable tragedy that shakes their worldview to the core, or the inevitable villain trying to twist them into darkness, they tend to overcome that temptation and come out the other side even stronger than when they started. In other words?...characters like these are being allowed the exact same sorts of narrative luxuries that are usually only afforded towards male heroes.

The thing about these characters, though, is that they tend to be...well, a little bit too heroic, right? A lil’ bit too goody-two-shoes? A bit too stalwart, a bit too incorruptible? And that’s fine, there’s certainly nothing wrong with a traditionally-heroic white knight of a hero. But what I might like to see, as the next step going forward, is for female heroes to be allowed a bit more range than just that, so that they’re not just innocent children or literal princesses or shining demigods clad in primary colors. Let’s have an all-powerful female hero be...well, the easiest way to say it is let’s see her allowed to be bitchier. Less straightlaced. Let’s not put an ultimatum on her power, like “Oh sure you can be powerful, but only if you’re super duper nice about it.” Let us have a ruthless woman, but not one ruled by ruthlessness. Let us have a hero who naturally makes enemies and not friends, who has to work hard to gain allies because her personality doesn’t sparkle and gleam. Let her have the righteous anger of a lifelong slave, and let that anger be her salvation instead of her downfall.

In other words, let us have Daenerys Targaryen. And let us put her in a new story instead of an old one.

#Game of Thrones#Daenerys Targaryen#ASOIAF#A Song of Ice and Fire#Jon Snow#Bran Stark#Arya Stark#Dany#GoT#GoTedit#Overthinking#meta#essay

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

Tyrion and Zuko: The Good Bad Guy, The Bad Good Guy

I’ve never seen anyone compare Tyrion Lannister and Zuko, but the parallels seem so obvious to me. I know there’s been a lot of comparisons in fandom to Zuko and his arc and a lot of discussion of what makes a good redemption arc and I’m not necessarily talking about this from that perspective, because I don’t really think Tyrion is on a redemption arc (and also reject the idea that I’ve seen bandied about that he is on a “villain” arc or that his arc is in opposition to his brother Jaime’s, with Jaime as the one who is usually seen by fandom as set up for redemption.) But I do think the parallels between the two characters are striking. I don’t think they’re 1:1 and even many of the parallels I make are not intended to be exact, as these two characters have narratives that are structured differently, and of course there are differences based on medium and target audience between the two series.

This is part one of a series of posts on these two characters, and this part will focus on how these characters are positioned structurally by the narrative.

Spoilers for both series to follow!

The biggest, most immediate difference between Tyrion and Zuko is that Zuko is positioned as an antagonist at the beginning of the story (although not necessarily a villain), while Tyrion is not antagonistic to the identifiable heroes at the beginning of AGOT, and is in fact the only Lannister not to be positioned that way by the narrative initially. In fact, part of this meta and part of my purposes for comparing them is to argue that Zuko’s narrative arc is not a straight line from villain to hero, which makes him very similar to Tyrion and his narrative positioning as the “good bad guy, the bad good guy” as Peter Dinklage says of his character on Game of Thrones. Even though Zuko’s mission at the beginning of the series is antagonistic to Team Avatar, he is still presented as a POV character with whom we are meant to sympathize, if at first only through sympathetic characters in his story like Iroh and characters who act as antagonistic in his own story, like Zhao and later Azula.

Tyrion also is presented to us as on the “bad side” of the narrative. He’s a Lannister, and many of the immediately sympathetic characters dislike and distrust him. Yet he is positioned sympathetically almost immediately as seen through characters like Jon Snow and Bran, and in contrast to his brother and sister.

Zuko and Tyrion also are positioned similarly in the narrative in relation to the way they are paired with and against the other characters in the story. Heroic narratives often make use of the Rule of Three, and one way in which this is shown is in presenting the main characters of the story as a triad. This type of narrative will have a protagonist, a deuteragonist, and a tritagonist. Usually the protagonist and the deuteragonist are male, and serve as foils and shadows of each other, and the third protagonist, or tritagonist, is a female character. You could argue about who takes the second and third position but it’s inarguable that in Avatar: The Last Airbender (further referred to as ATLA), these characters are Aang, Zuko, and Katara. In A Song of Ice and Fire (further referred to as ASOIAF) these characters are Jon Snow, Daenerys Targaryen, and Tyrion Lannister. This is also why it’s often theorized that Tyrion is the third head of the three-headed dragon that Dany and Jon are both part of, despite not having any Targaryen blood.

The other narrative structure that ASOIAF uses with regard to the characters that mirrors ATLA is what George R R Martin coins “the five key players” in his original manuscript of ASOIAF:

Five central characters will make it through all three volumes, however, growing from children to adults and changing the world and themselves in the process. In a sense, my trilogy is almost a generational saga, telling the life stories of these five characters, three men and two women. The five key players are Tyrion Lannister, Daenerys Targaryen, and three of the children of Winterfell, Arya, Bran, and the bastard Jon Snow. (source)

I have theorized from what he says here that when Martin originally conceptualized his story, he intended for Tyrion to be younger than he is when we see him in the series, as Martin says that the five central characters will “grow from children to adults,” and Tyrion is already an adult as of his first chapter in A Game of Thrones. However, the fact that Tyrion is quite a bit older than the other four is thematically important. Tyrion is a character who, when we see him at the beginning of the story, has lost his innocence and become embittered by an abusive childhood and a lifetime of cruelty directed towards him because of his dwarfism. Yet Tyrion, thoughout the series, often relates to the child characters specifically because of that lost innocence. He offers help and advice to Jon, Bran, and Sansa throughout the series, and as of ADWD is on his way to join Daenerys.

Similarly, Zuko is positioned against the four main child characters of ATLA that make up Team Avatar, Aang, Katara, Sokka, and Toph, and has moments where he relates to them even before he seeks to join them. And although Zuko is only sixteen and very much a kid (which becomes even more apparent when he joins the gaang), and Tyrion is an adult, he is still a young man and his relationship to Jon is something like that of an older brother.

Zuko and Aang’s relationship could be compared with that of Jon and Tyrion. Jon and Aang offer friendship to someone who they should consider an enemy, and Tyrion and Zuko end up becoming unexpected mentors to the younger boys. In both stories, this serves to highlight the tragedy of how war pits people against each other and what each of these characters has lost.

Aang to Zuko: If we knew each other back then, do you think we could have been friends, too?

-S1E13

Even after ADWD and all the war and strife between Stark and Lannister, Jon still considers Tyrion his friend. Obviously, we do not have the ending of ASOIAF to compare to ATLA, but I find it an interesting parallel, nonetheless.

Another thing that makes the characters similar on a structural level is the use of visual symbolism to show the characters’ internal struggle and duality. This is a clever and immediate way for the audience to understand that this is a character who we are meant to see as morally complex. Visual symbolism is more obvious in a medium like animation, and the specific piece of visual symbolism is something that was downplayed in ASOIAF’s television adaptation, so it might be less apparent, but I’ve talked before about how Tyrion’s heterochromia is a visual symbol of his dual nature as a character and his struggle with his identity.

Similarly, Zuko’s scar functions as a symbol of his duality. And although Tyrion also has a dramatic facial mutilation to compare Zuko’s burn scar to, I am comparing Tyrion’s heterochromia to Zuko’s scar instead because of the symbolism associated with eyes and seeing.

It is often said that “the eyes are the windows to the soul,” and the reason for this is obvious. Often we look into another person’s eyes to get a glimpse of who they are, to understand and empathize, to connect and hope they connect with us. Therefore, in fiction, eyes can often tell you a lot about a character’s identity. Having a scar over one eye is an immediate signal of Zuko’s conflict from the moment he is introduced to the audience. His stated goal from episode one is to capture the Avatar, but as the series goes on we see what this goal really is: an impossible task given to him by his father because it is impossible. Therefore, Zuko’s desire to regain his identity as prince of the Fire Nation is put into question. And what better way to represent a conflict with Zuko’s identity towards the Fire Nation than with an injury caused by fire? I’ll talk much more about Zuko’s scar in part two because this is an extremely important part of his narrative.

Tyrion’s heterochromatic eyes function in a similar way, and mirror the way Martin uses color symbolism in ASOIAF. Tyrion is described in the books as having one green eye and one black one, a fact that was not included in the show save for one scene in the pilot, and was eventually discarded, as were Dany’s purple eyes, because of the difficulty colored contacts posed for the actors, and because, as I suspect, it was decided that it was not enough of a noticeable detail to be worth the trouble. It’s a lot easier to get away with things like this in animation (and Zuko’s scar doesn’t work in a live action series for similar practical reasons), but Tyrion’s “mismatched” eyes are a detail often mentioned in the books. Tyrion’s green eye is the eye color he shares with his brother and sister and father, and is known as a distinctive Lannister trait, representing their physical beauty and perfection. And like Tyrion’s disability, his heterochromia is an imperfection and so not tolerated in a House that prides itself on perfection. His black eye, in contrast, while often called his “evil” eye and is a cause, in addition to his dwarfism, for others to treat him like a pariah, brings him closer to who he is as a person separate from his family, as dark eyes represent earthiness and intelligence.

Zuko’s scar also marks him as other the way Tyrion’s heterochromia marks him. It is often called attention to by characters in the series. In the first season it is often used to make him look frightening. Yet it also marks him in the eyes of the audience and the eyes of other characters as a victim of the Fire Nation and a survivor. In this way, the meaning of Zuko’s scar becomes flipped and it is his unmarred side that links him to what appears on the surface to be the order and perfection and superiority of the Fire Nation, but which, just like Zuko’s face if we are only looking at it from one side, hides a warped horror.

In part two I talk about how these two characters have similar trauma and conflict with relationship to their families and how that shapes their narratives.

20 notes

·

View notes

Note

You talked about dany meeting jon and tyrion and how their approaches of physical expression are different from her, could you expand on that and what that might means for those relationships?

Absolutely! Daenerys, Jon, and Tyrion have incredibly significant parallels and narrative ties to one another, but they also work as three-way foils in a lot of ways. It’s one of the reasons the intersection of their arcs is the thing I’m most looking forward to in the series.

One of the biggest points of analysis for Jon, Dany, and Tyrion as characters, I’ve noticed, is through their physical interactions with those around them, and how those interactions connect to their personalities, their backgrounds, and their tendencies as rulers/leaders.

Under the cut for length!

Daenerys | Tenderness, Physicality, and Action

I detailed in this post that Daenerys is very driven by physical affection. She is consistently shown kissing others, hugging them, and generally being casually warm and friendly.

“No. Mother to us all.” Missandei hugged her tighter. “Your Grace should sleep. Dawn will be here soon, and court.”

“We’ll both sleep, and dream of sweeter days. Close your eyes.” When she did, Dany kissed her eyelids and made her giggle. (Daenerys II, ADWD)

“And what is it that you fear, sweet queen?”

“I am only a foolish young girl.” Dany rose on her toes and kissed his cheek. “But not so foolish as to tell you that. My men shall look at these ships. Then you shall have my answer.” (Daenerys III, ADWD)

“As you say, Your Grace. Still. I will be watchful.”

She kissed him on the cheek. “I know you will. Come, walk me back down to the feast.” (Daenerys III, ADWD)

One of her young hostages brought her morning meal, a plump shy girl named Mezzara, whose father ruled the pyramid of Merreq, and Dany gave her a happy hug and thanked her with a kiss. (Daenerys III, ADWD)

These are just a few examples. In Dany’s ADWD chapters alone, there are 34 mentions of variations of the word “kiss”, and that compared to the 122 mentions of it throughout the entire book. Not only is Daenerys consistently physical with those around her, but it’s also worth noting that in all these instances, Daenerys is always the first to engage in or initiate the physical contact.

This is both a nod to her status as mother, rescuer, and protector, and also a refreshing display of a female character being openly and unabashedly tender. Daenerys’ status as queen doesn’t make her cold, emotionless, or aloof, but instead it draws focus to the vital aspects of her character.

This physicality is who Daenerys is at her core: someone who takes action. When she realized Viserys wouldn’t get them home to Westeros, Daenerys stepped up and did something. After Drogo died and the khalasar split apart, she walked into a pyre and did something. When she saw the way slaves were treated in Astapor, she derailed her previous plans and did something. For Daenerys, the best course of action is simply taking action, something we see reflected in the way she interacts with others.

There is one fascinating caveat to this, and it surfaces in regards to sexual and/or romantic encounters.

[Hizdahr] is not hard to look at, Dany told herself, and he has a king’s tongue. “Kiss me,” she commanded. (Daenerys IV, ADWD)

The others bowed and went. Dany took Daario Naharis up the steps to her bedchamber, where Irri washed his cut with vinegar and Jhiqui wrapped it in white linen. When that was done she sent her handmaids off as well. “Your clothes are stained with blood,” she told Daario. “Take them off.”

“Only if you do the same.” He kissed her. (Daenerys VI, ADWD)

Daenerys instigates sexual/romantic interactions through clear verbal consent, leaving it up to the other party to make the physical move. This could tie back to her abuse at the hands of both Viserys and Drogo, because even though Daenerys is still a physically and sexually active person, her past experience has given her the need to have control in those situations. The ability to take action is a quality of that control, and through those things Daenerys avoids perhaps the thing she hates most in the world: feeling helpless.

Jon | Respect, Reservation, and Action

Similarly to Daenerys, Jon’s background informs his relationship with his own physicality. While Dany initiates contact, however, Jon is quite the opposite; he receives touch instead of giving it.

“He may not heed your words, but he will hear them.” Val kissed him lightly on the cheek. “You have my thanks, Lord Snow. For the half-blind horse, the salt cod, the free air. For hope.” (Jon VIII, ADWD)

Alys Karstark slipped her arm through Jon’s. “How much longer, Lord Snow? If I’m to be buried beneath this snow, I’d like to die a woman wed.”(Jon X, ADWD)

“You could dance with me, you know. It would be only courteous. You danced with me anon.”

“Anon?” teased Jon.

“When we were children.” She tore off a bit of bread and threw it at him. “As you know well.”

“My lady should dance with her husband.” (Jon X, ADWD)

To put this further in perspective, there are 14 mentions of the word kiss in Jon’s ADWD chapters compared to Dany’s 32, and most of them refer to swords “kissing” or Ygritte being “kissed by fire”. When the word does refer to the action of kissing, it is mostly in regards to others (usually kissing hands).

Jon doesn’t initiate contact because he isn’t supposed to. He’s a bastard and a man of the Night’s Watch, two things that he’s acutely aware of when it comes to any form of physical contact.

Melisandre laughed. “It is his silences you should fear, not his words.” As they stepped out into the yard, the wind filled Jon’s cloak and sent it flapping against her. The red priestess brushed the black wool aside and slipped her arm through his.

[…]

Jon could feel her heat, even through his wool and boiled leather. The sight of them arm in arm was drawing curious looks. They will be whispering in the barracks tonight. “If you can truly see the morrow in your flames, tell me when and where the next wildling attack will come.” He slipped his arm free. (Jon I, ADWD)

Jon, not unlike Daenerys and Tyrion, always takes people’s perception of him into consideration. He dwells on his status as a warg, an assumed turncloak/wildling, a son of Eddard Stark (a “traitor”, as others continuously bring up), and a bastard. He is constantly under a negative light because of his status, from the moment we’re put in his first POV, sitting beneath the high table at Winterfell to avoid insulting the king.

For Jon to be overtly physical would be presumptuous, and so his lack of initiating touch is an attempted sign of respect, a habit instilled in him from the past. Other people are required to make the first move, and Jon just has to wait and watch.

This doesn’t downplay the action of Jon’s chapters or his character, however. Jon is still an incredibly active character, like Daenerys, but while Dany is able to display that casually, Jon’s primary form of contact with others in ADWD and even in prior books is through sparring or sword fighting.

Jon’s blade slammed him alongside his head, knocking him off his feet. In the blink of an eye the boy had a boot on his chest and a swordpoint at his throat. “War is never fair,” Jon told him. “It’s two on one now, and you’re dead.”

When he heard gravel crunch, he knew the twins were coming. Those two will make rangers yet. He spun, blocking Arron’s cut with the edge of his shield and meeting Emrick’s with his sword. “Those aren’t spears,” he shouted. “Get in close.” He went to the attack to show them how it was done. Emrick first. He slashed at his head and shoulders, right and left and right again. The boy got his shield up and tried a clumsy countercut. Jon slammed his own shield into Emrick’s, and brought him down with a blow to the lower leg … none too soon, because Arron was on him, with a crunching cut to the back of his thigh that sent him to one knee. That will leave a bruise. He caught the next cut on his shield, then lurched back to his feet and drove Arron across the yard. He’s quick, he thought, as the longswords kissed once and twice and thrice, but he needs to get stronger. (Jon VI, ADWD)

Again, the imagery evoked by the word “kiss” comes up, though in a significantly different context than with Daenerys. Jon hesitates to take people by the hand, but when it comes to fighting, he moves. This is where he can take initiative, where being highborn, lowborn, trueborn, or bastard born suddenly ceases to matter.

Tyrion | Words, Words, Words (i.e. Repression, Manipulation, and Action)

If Jon and Daenerys are on opposite ends of the spectrum with touch, Tyrion is on a scale of his own. Like Jon, Tyrion is conditioned to avoid touching others, not as a result of his class, but simply as a result of who he his. As a dwarf living in a supremely shallow and ableist society, Tyrion’s POV always holds that weight, always in the mindset that world despises him for his appearance, for his disability, for his entire person.

And Cersei began to cry.

Tyrion Lannister could not have been more astonished if Aegon the Conqueror himself had burst into the room, riding on a dragon and juggling lemon pies. He had not seen his sister weep since they were children together at Casterly Rock. Awkwardly, he took a step toward her. When your sister cries, you were supposed to comfort her … but this was Cersei! He reached a tentative hand for her shoulder.

“Don’t touch me,” she said, wrenching away. It should not have hurt, yet it did, more than any slap. Red-faced, as angry as she was grief-stricken, Cersei struggled for breath. “Don’t look at me, not … not like this … not you.” (Tyrion V, ACOK)

Tyrion has a horrible relationship with his own physicality and sexuality, and it’s in no small part due to the abuse (physical, verbal, and emotional) he endured from his family. Tyrion thinks that people don’t love him, that they can’t love him, much less ever want to touch him, and it shows in his POV. When a situation arises where comfort is needed, he finds himself at a loss.

As we transition into ADWD and meet Penny, we expand on this.

“My lady,” Tyrion called softly. In truth, she was no lady, but he could not bring himself to mouth that silly name of hers, and he was not about to call her girl or dwarf.

She cringed back. “I … I did not see you.”

“Well, I am small.”

“I … I was unwell …” Her dog barked.

Sick with grief, you mean. “If I can be of help …”

“No.” And quick as that she was gone again, retreating back below to the cabin she shared with her dog and sow. Tyrion could not fault her.

[…]

And the sight of me can only be salt in her wound. They hacked off her brother’s head in the hope that it was mine, yet here I sit like some bloody gargoyle, offering empty consolations. If I were her, I’d want nothing more than to shove me into the sea. (Tyrion VIII, ADWD)

In terms of action, Jon and Daenerys both find ways to maximize it given their own situations. Jon can fight and lead, and Daenerys can fight and lead differently. Tyrion, however, has found through experience that his best means of accomplishing his goals is through words. He doesn’t have the physical ability or beauty of others (such as his siblings), and even his highborn birth might not be enough to get him out of some things. Tyrion’s best course of action is always verbal; well placed threats, bribes, compliments, lies, and whatever else he can come up with.

When those fail, he feels he doesn’t have much left.

And yet, later, we get this:

The [slave] collars were made of iron, lightly gilded to make them glitter in the light. Yezzan’s name was incised into the metal in Valyrian glyphs, and a pair of tiny bells were affixed below the ears, so the wearer’s every step produced a merry little tinkling sound. Jorah Mormont accepted his collar in a sullen silence, but Penny began to cry as the armorer was fastening her own into place. “It’s so heavy,” she complained.

Tyrion squeezed her hand. “It’s solid gold,” he lied. “In Westeros, highborn ladies dream of such a necklace.” (Tyrion X, ADWD)

Tyrion may be conditioned to believe others don’t want his touch, but that doesn’t mean he can’t desire it himself. Tyrion wants to be loved, no matter how disillusioned he is with the concept; he wants comfort, physical comfort, and he wants to be able to offer others the same. It is significant and hopeful that he takes Penny’s hand in this passage, despite the dark path ADWD takes him on.

The Dragon has Three Heads | Relationship Dynamics

So, what does this all mean going forward for these characters? What will their dynamics be like, and what will influence them?

No one can say for sure until we see it up front, but the differences between Jon, Daenerys, and Tyrion’s relationships with physicality and action are undoubtedly going to be meaningful.

Daenerys’ embracement of physicality rivals both Jon and Tyrion’s avoidance of it; it wouldn’t be out of character for her to kiss them, hug them, or hold them. For Tyrion especially, such interactions would be out of the norm and thus could become particularly significant. Jon and Daenerys have been foreshadowed to become romantically involved, but (as many have recently learned) foreshadowing doesn’t equal development; the growth of whatever relationship evolves between them is likely going to be tied to the two’s unique methods of physical affection and action.

And that’s the thing: for all their differences, Jon, Tyrion, and Daenerys all hold in common their desire to take action. They use what skills are available to them, but each approaches it from a different angle. The eventual combination of the three is going to be vital in the War for the Dawn, but I expect the road there will be filled with pitfalls.

There’s also the fact that Jon’s physicality (or lack thereof) will likely change in TWOW; after being murdered, living as a wolf, and getting resurrected, I imagine he’ll go from avoiding touch out of respect to avoiding being touched in general. That, along with Daenerys’ refreshed “Fire and Blood” mindset, and Tyrion’s progressively worsening PTSD induced spiral all provide some interesting (and dangerous) ingredients for their future dynamics.

#asoiaf#asoiaf meta#asoiaf speculation#valyrianscrolls#daenerys targaryen#tyrion lannister#jon snow#ask#anonymous#this got long holy crap#also tumblr at my first response and I almost died

275 notes

·

View notes

Note

I can't be sure of darkdant myself because of the show runners, they love giving people what they want and no one wants this except for like 3 people, it's too bold a move for them

I don’t have any of the worries you have and here’s why…

First of all, I think you’re giving way too much power to D&D. The later seasons of the show are supposed to follow the events of the books in broad strokes. They didn’t adapt every plot point, or every character, or incorporated every theme in the story, and there are certainly going to be obstacles in the books that the show hasn’t touched at all, however the endgame of the two products are supposed to mirror each other. George R R Martin told D&D the key plot points that the endgame was supposed to be centered on. I’m convinced that one of these plot points is Daenerys’s progressive shift from a hero in her own rights to a villain. This is something that’s been built it in the books, and the last time we’ve seen Daenerys, she decided to embrace fire and blood over building olive trees, and I’ll say that it is also something that the show set the pieces for, albeit with much less nuance. Daenerys has extremely wonderful internal monologues about her morality, she has a lot of wonderful qualities, dialogue with other characters that endear her to the reader and her backstory and motivations were explored more throughly so her character made better sense. I’ve made a few posts on here elaborating on my love for her in the books. While D&D had the power to change a lot of stuff in the journey to the ending, what’s set to happen for all of the protagonists of the story will generally be the same in the books or the show. Of course I may be wrong, but from what D&D and GRRM have said, that seems to be the case. So whether it turns out to be true or not depends solely on whether GRRM planned for it to happen, and I think the story makes it abundantly clear that they are going that direction with her character.

Second of all, looking at all that Daenerys caused and did, it’s not hard to see how tyrannical and darker she has become, and it’s not as if change happened coincidentally. D&D and the other writers wrote scenes in which the characters discussed her morality and wrote scenes where her actions were portrayed in a neutral if not subtly negative light. It’s not as if her character is glorified every single second she appears on the show. If they wanted to sell her as this perfect divine feminist badass queen that is always right and never makes mistakes, they could. In fact, they do it with other characters. In the late seasons, Jon Snow is depicted as being the center character in the story. He never makes any mistakes that have a substantial negative impact on anyone, people who don’t agree with him are portrayed negatively by the narrative, he gets the most screen-time, he gets the parentage reveal, he gets to have the best claim to the throne and is slated to not only live, but win everything in the coming season. This could have been Daenerys, and many people wrongfully believe that Daenerys is that type of character, but she’s not, and the writers never wanted her to be like that. She has a lot of flaws, she fails and blunders, she is portrayed negatively in some scenes, her actions has actual negative repercussions on her and the people around her, and there are more and more scenes in the story that are there in order to make the viewers question her character. The interviews from the different directors and writers only make it more evident. Sansa’s execution of Littlefinger is canonically a foil to Daenerys’s execution of the Tarlys, and in this particular comparison, it’s Daenerys who’s set up by the writers to look bad. They definitely aren’t scared of portraying her in a bad light. That being said, they definitely white-washed certain characters from the books that would give them profit, like Tyrion. However, they’ve decided not to do the same with Daenerys, and I think that’s important to note.

Third of all, I don’t think that your interpretation of D&D is completely accurate. From what I can get from this post, you seem to think that they breathe on servicing the fans and that they put such an importance on the fan’s opinion that they would alter such a major plot point. I don’t think that’s true. The moments that D&D tend to be the most interested in are the big shocking reveals, major death scenes or/and scandalizing and dramatic scenes. It’s these scenes that drove them to adapt this series in the first place. They were eerily giddily about the idea of burning a child on this show, or having a season long story-line centered around the abuse and rape of a major female character that might leave the viewers mouth to drop. Daenerys Targaryen who is a fan favorite character that so many viewers rallied for, going dark and doing something shockingly horrifying would be right up their alley of stuff that they love adapting, and it would get such a massive reaction from the viewers, whether positive or negative. Of course, it’s not as if they listen to the negative feedback but the point I’m making is that what they are interested in adapting isn’t always what the general audience want, but more so what might get the biggest reaction from the viewers while still making some sense with the rest of the story. Therefore, this would be right up their alley.

In conclusion, Daenerys is definitely going dark next season because that’s set to happen in the original material, because the show progressively led Daenerys to a darker path and because that’s the kind of twist that D&D love.

#anti daenerys#anti daenerys targaryen#anti dany#dark dany#it's less anti dany and more dark dany but whatever#also there's a fuckton of people who want dark!dany lmao#asks

56 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Song of Ice and Foils - Jon & Daenerys

The more I see Jon and Dany’s stories portrayed as parallels, the more I’m convinced they are foils. GRRM is writing a genre-defying story of good vs evil. Both protagonists believe they are good and that they are doing what is right - but even if they go down similar paths, their life experiences and personalities will ultimately lead them to different results. One will triumph, and the other will fall. Like fire and ice.

A literary foils purpose is to highlight another characters (or even one subplot foiling another subplot) qualities by starkly contrasting them. It doesn’t always have to be “hero vs villain” or “protagonist vs antagonist” - but it is a beautiful literary device to help readers. With ASOIAF, and if the ending will reveal true character, then Jon and Dany will have some similarities and also some contrasts. What sets them apart will show what truly affects them and shapes their morality.

Jon and Dany will have similar things happen to them. They will follow similar story arcs, they will encounter similar hardships which will propel them forward in the plot, but the end will reveal their true character. GRRM will make us root for both of them and then pull the rug out from under us and show that it is not just our experiences and titles that matter, but what we are on the inside. If we put two similar characters down a similar path, we will see their true character revealed in the bitter end.

So far in ASOIAF, we are led to believe that being honorable and doing the right thing will not always win or end happily. That’s a great rule of life- reality is cruel and bad things happen to good people. GRRM doesn’t want characters to be good or bad, or white or black - he wants them to be interesting, to be sympathetic, and to be blurred in grey. So making us root for two characters who are foils will perhaps force us to choose a side, even if that side is grey.

Having two main characters be foils, neither of which are the clear-cut antagonist, keeps readers on the edge of their seats, keeps readers guessing about the end, and prevents a story from being predictable. ASOIAF is all about turning the high-fantasy genre on its head. To guess what Jon and Dany being foils means, to try and guess the outcome will be, would require knowledge of what theme and moral GRRM is wanting to achieve. And I can’t begin to presume I know 100% the answer to that. And anyone who says otherwise is no true King.

Besides the obvious contrasting characteristics, their gender, their appearance, their locations, we also have their backgrounds, upbringing and their contrasting morals. Jon is a bastard looking for his calling, and Dany a ousted princess looking for her calling. One is an honorable boy and the other a girl who was raised with a sociopath. My question is: nature vs nurture??

One thing that is driving me crazy, is seeing Jon and Danys characteristics and similarities being portrayed as parallels and hints at a Jonerys endgame. So here are the best ones I can think of off the top of my head.

Similarities:

1. Third child whose mother died in childbirth. (This is a streeeeeetch, but I’ve seen it used.)

2. Both are hidden from Robert Baratheon.

3. Jon was born a “bastard” who felt unwanted and is looking for his place. Dany was born a princess who grew up as a fugitive who lost her title.

4. They find surrogate families. Jon with the Night's Watch, and Dany with the Dothraki.

5. Both received animals that represent their houses; Jon and Ghost, and Daenerys and her Dragons.

6. Both received important weapons for defeating the White Walkers. Jon receives Longclaw and Dany and her dragons.

7. Both eventually fall in love with their “captors” from a different culture - Jon and Ygritte, Dany and Drogo.

8. Both are ousted by an uprising; Jon and the Nights Watch, and Dany with the Harpies. Both are direct results of their actions, but Jon was not outsed by the people he helped, whereas Dany kind of was.

Contrasts:

1. Male. Female.

2. Jon has dark brown hair, and dark-almost-black grey eyes. Daenerys has pale silver gold hair, and light violet eyes.

3. Jon grew up in one place, with a secure family unit. Dany grew up constantly moving and on the run, with only her older brother.

4. Jon had a good role model and father figure growing up. Dany did not have a good role model or father figure growing up.

5. Jon grew up in the cold climate of the North, and Dany grew up in the warm exotic Essos.

6. Jon is not searching for power, instead being voted in and accepting the responsibility, whereas Dany is on a quest for power and vengeance.

Things that are touted as parallels, but are actually contrasts:

1. Both leave their home, Jon to the night's watch and Dany with the dothraki. Jon is searching for a purpose in life better than his bastard status at Winterfell. Dany is used as a pawn, forcibly married off to a culture she doesn’t understand to help her brother start a war.

2. Become close friends with a member of a noble house - Jon with Sam from house Tarly, and Dany with Ser Jorah from house Mormont. Sam is loyal to Jon as a true friend, and Jorah is not, at first using her for his own gains. And Jorah is still beneath Dany, not ever really considered her equal. Sam has been “banished” to the nights watch for simply not being the fierce warrior his father wanted, and Jorah is banished from Westeros for selling slaves.

3. Both protect the vulnerable by threatening someone - Jon threatens the boys bullying Sam at Castle Black, and Dany threatens Viserys. 🎼One of these things is not like the other. 🎼 The mindsets are different. Jon is protecting someone other than himself, being selfless. Dany is standing up to her own abuser.

4. Lost a family member. Jon lost Benjen and Dany lost Viserys. 🎼One of these things is not like the other. 🎼

5. After tragedy strikes their heads of household, Ned’s arrest/death and Drogos illness/imminent death, they must chose between their family and upholding an ethical code. Jon chooses to honor his vow and stay with the nights watch and Dany decides to defy the laws of nature and go against Dothraki law to try and save Drogo. (One argues that she did it for selfish reasons, as once Drogo is gone, so is her power.)

6. They fall in love with someone from another culture, Ygritte and Drogo, and their lovers die from chest wounds. No ones going to mention that Drogo dies as a direct result of Danny’s actions? No one? 👀

7. Dany does not take the guilt and responsibility of Drogos death, instead burning the witch. Jon takes the guilt upon himself, becoming distant and cold, and doesn’t hold someone else accountable for Ygritte’s death.

These are are the basic “parallels” I most often see used as proof of a Jonerys endgame. In my opinion, it’s the opposite. They are foils. We’re going to see the true character and morals come to a nasty head by the end of the series.

[A few more posts to come.]

15 notes

·

View notes