#the ravages of time

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Another video of collection of things I love, simply like to look at, or looking forward to. XD With the song "River of Blood" by Huang Xiaoyun.

Qin's Moon (Animation TV series)

9 Songs of the Moving Heavens (Animation TV series)

Legendary Twins (Animation TV series)

The Ravages of Time (Animation TV series)

The Demon Hunter (Animation TV series)

THRUD (Animation TV series)

Green Snake (Animation movie)

New Gods: Yang Jian (Animation movie)

Honkai: Star Railway (Video game)

Punishing: Gray Raven (Video game)

Black Myth: Wukong (Video game)

Where Winds Meet (Video game)

Condor Heroes (Video game)

Project: The Perceiver (Video game)

Aether Gazer (Video game)

Gujian 3 (Video game)

I would have added Moonlight Blade Mobile too, but I think I'll wait until I have more clips or something.

This upload focuses only on Chinese animation and Chinese video games. It's because the list was pretty long already and I didn't want to squeeze in the others.

This song is from (or is for) a mobile game titled Justice Online/逆水寒. Probably a promotion song for it. I got curious about the lyrics and ended up giving it a rough translation.

#donghua#chinese video game#Qin's Moon#9 Songs of the Moving Heavens#Legendary Twins#The Ravages of Time#The Demon Hunter#THRUD#Green Snake#New Gods: Yang Jian#Honkai: Star Railway#Punishing: Gray Raven#Black Myth: Wukong#Where Winds Meet#Condor Heroes#Project: The Perceiver#Aether Gazer#Gujian 3

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

Dying is easy in this day and age. But real courage comes from knowing that more can be done if you stay alive.

chapter 602, The Ravages of Time

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Ravages of Time episode 6

After so long, it's finally here! This was a lot of work for something that maybe two and a half people will read, but I had a lot of fun with it and am ridiculously proud of everything I've learned working on this.

Episode 6

I say Lü Bu is not human

Lü Bu, courtesy name Fengxian, was a famous general of the late Eastern Han dynasty, a skilled horseback archer and a brave and experienced warrior.

Lü Bu was appointed a Registrar by the Bingzhou governor Ding Yuan [1], but later killed him and became Dong Zhuo’s sworn son [2], acting as the official in charge of the imperial palace security, then grew suspicious of Dong Zhuo, and killed him with the help of the Minister over the Masses Wang Yun [3]. He then tried to join Yuan Shu [4], but was refused, and instead turned to Yuan Shao [5], only to again be met with suspicion, and later joined Zhang Yang [6]. After that, Lü Bu and Cao Cao opposed each other for two years. Lü Bu was also occasionally allies, occasionally enemies with Liu Bei, creating the story of Lü Bu shooting the halberd [5].

On the third year of Liu Xie’s third reign (should be around 199 CE), after Lü Bu defeated Liu Bei and Xiahou Dun [6], Cao Cao personally went on a campaign against him. There was a rebellion in Lü Bu’s forces, and he was defeated and taken prisoner. Cao Cao had Lü Bu executed.

---

Readmore here because there are so many notes...

[1] Ding Yuan – a warlord who was summoned to Luoyang alongside with Dong Zhuo to assist in the power struggle against the eunuchs, but arrived slightly later. According to the Records of the Three Kingdoms, he was originally from a poor family and rose to power through his bravery and sense of responsibility. Just like Lü Bu, he was a skilled rider and archer.

[2] Sworn son – typically translated as “adopted son”. However, I wanted to dive a little deeper into the nature of their relationship – see this post on the matter.

[3] Wang Yun – a Han dynasty official and politician known mostly for his part in Dong Zhuo’s murder. That was the height (at the time he was the Minister over the Masses – one of the three highest posts in Han dynasty) and the end of his career – within a few months, he was assassinated by Dong Zhuo’s followers in Chang’an.

[4] Yuan Shu – a Han dynasty warlord with an admittedly long and curious biography that won’t all fit here – besides, he’ll be an active participant in the events I assume will make it into the donghua. For now, after Dong Zhuo fled Luoyang, Yuan Shu came into the possession of the Imperial Seal, given to him by his subordinate Sun Jian.

[5] Yuan Shao – another Han dynasty warlord and another active participant in the Late Han politics. He and Yuan Shu did not have a good relationship, partially due to the circumstances of Yuan Shao’s birth. Now this is where things get complicated. English Wikipedia will tell you that he was Yuan Shu’s half-brother, but that’s… not really known, and under the circumstances, I don’t think any certain claims can be made. Yuan Shao was the son of a servant, and later adopted by Yuan Shu’s uncle Yuan Cheng who had no heirs (he is referred as just Yuan Cheng’s “son”, and if you’ve read the “sworn sons” post, looks like it was one of those relationships that gave him the family name and the right to inherit). Either way, despite the shady circumstances of birth, his status was higher than that of Yuan Shu’s, which didn’t stop Yuan Shu from claiming Yuan Shao wasn’t a “true” Yuan when they had disputes. Family.

[6] Zhang Yang – this Han dynasty general didn’t die by Lü Bu’s hand, but he was murdered by a subordinate a few years later while trying to help Lü Bu in his struggle against Cao Cao. He was described as a brave warrior, but wasn’t as involved in court politics as Yuan Shu or Yuan Shao. From what I’ve read in his biography, it almost sounds like politics was happening to him and not the other way around – he was mostly kept out of real power by the people in charge, even when they recognized his talents and contributions.

[7] The story of Lü Bu shooting the halberd is a famous story from the Romance of the Three Kingdoms. Basically a feat of unmatched marksmanship, but more on that later.

In chapter 16 of the novel, Lü Bu gets caught between two opposing forces of Liu Bei and Ji Ling (Yuan Shu’s general). Ji Ling, who had helped Lü Bu previously, was threatening Liu Bei, and Liu Bei, despite the reservations of his allies, decided to turn to Lü Bu for help. Not wanting to directly oppose Ji Ling and yet also not wanting him to win and gain more strength, Lü Bu called the two of them to his camp to settle things. While Liu Bei was eager to reach a peaceful solution, Ji Ling was intent on fighting. Finally, Lü Bu asked for his halberd, had it set in the ground 150 paces away and made a deal with the two that if Lü Bu could shoot the small blade from a bow, they’d leave peacefully. Certain that the task was impossible, Ji Ling agreed, Lü Bu shot the halberd, and thus the matter was temporarily resolved.

Now, just to put things into perspective, 150 paces is… a lot. To the best of my knowledge, during Han dynasty that would have been around 200 meters (650 feet) (even more if we assume the early Ming dynasty measurements of the time of the writing, that would be about 240 meters (790 feet)). Just… that’s an insane distance for archery. In modern Olympic archery (with the fancy bows and equipment), the largest distance for a recurve bow is 70 meters (230 feet). In traditional archery competitions, I don’t think I’ve ever seen anything over 40 meters (130 feet), and the typical distance is 20 meters (65 feet).

I don’t have a conclusion for this, really. Although Lü Bu is typically depicted with a halberd, there’s a reason one of his main defining characteristics is that he was an excellent archer. Of course, this is a fictional tale, but it certainly goes to show how Lü Bu was perceived.

[8] Xiahou Dun – one of Cao Cao’s trusted generals, nicknamed “one-eyed Xiahou” after he lost his eye to a stray arrow some time in the late 190’s. In historical records he is described just as a loyal and humble warrior as well as thoughtful administrator who kept the needs of the common folk in mind. The Romance of the Three Kingdoms really leaned into the whole one-eyed general thing though, describing him yanking the arrow (shot by Lü Bu in this version) out and eating his eyeball.

And now onto episode spoilers!

The song Xiao Meng sings before Dong Zhuo is unfortunately a song written for the show, since Xu Lin is a fictional character, and isn’t an actual old poem. Not sure if Guanshan Road there refers to a specific road, I haven’t been able to find a name for anything period-appropriate, so it could have just been a generic reference to a path through a mountain pass.

The official subtitles are a bit unclear in the part of Dong Zhuo’s speech where the dragon appears, because the translation… doesn’t feature a dragon? It goes something like, “A ruler will be revered by thousands of people wherever he goes. The real ruler is in our hands right now!” The actual words are more like, “Wherever he goes, he will be a dragon revered by thousands of people. This true dragon is now in our hands.”

(Additionally, having finally got around to reading at least the very beginning of the manhua, I actually get why sleeping with Dong Zhuo is absolutely not an option for Xiao Meng. It’s completely omitted in the donghua, but in the manhua Xiao Meng is in fact a eunuch.)

Pretty sure the instructor of the Imperial Guards Yuan Tai is a fictional character.

I had the funniest reaction after reaching the scene of Xiao Meng refusing Dong Zhuo, because that was the first time I fully realized the fake name is Diao Chan. The legendary beauty Diao Chan. And then I went back and rewatched episode 2. And indeed, Xiao Meng is sent to Wang Yun, Minister over the Masses, and I completely missed it then, too busy agonizing over Lü Bu’s halberd and the timelines.

It hasn’t really come up in previous notes, because it’s a fictional story used in the Romance of the Three Kingdoms, but there, part of the reason for the disagreements between Lü Bu and Dong Zhuo is a woman named Diao Chan (often stylized as Diaochan), Wang Yun’s daughter.

Actually, Diao Chan as Lü Bu’s wife appeared in previous stories, too, the depictions ranging from a woman completely unaware of the surrounding conspiracies to a femme fatale. But I think it was the Romance of the Three Kingdoms that established her connection to Wang Yun and sets Diao Chan as Dong Zhuo’s concubine that Lü Bu falls in love with.

Obviously that’s not what happens in The Ravages of Time, but that story was still clearly a source of inspiration. Though now I have to wonder, with Xiao Meng exposed, will Wang Yun’s involvement in the story change, or will they gloss over that part completely?..

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

My circle and I have a shopee shop, now!

You can visit us at:

https://id.shp.ee/ptXfJ5X

We also consider international shippings and orders outside Shopee! Do pm us for those~

Come take a look at our shop! And have an 'eggscellent' day~ 🥚💚

#fan merch#Magic hatch#honkai star rail#genshin impact#Obey me#Obey me!#limbus company#Pokemon#baldur's gate 3#call of duty#doki doki literature club#a3!#a3! act addict actors#the ravages of time

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

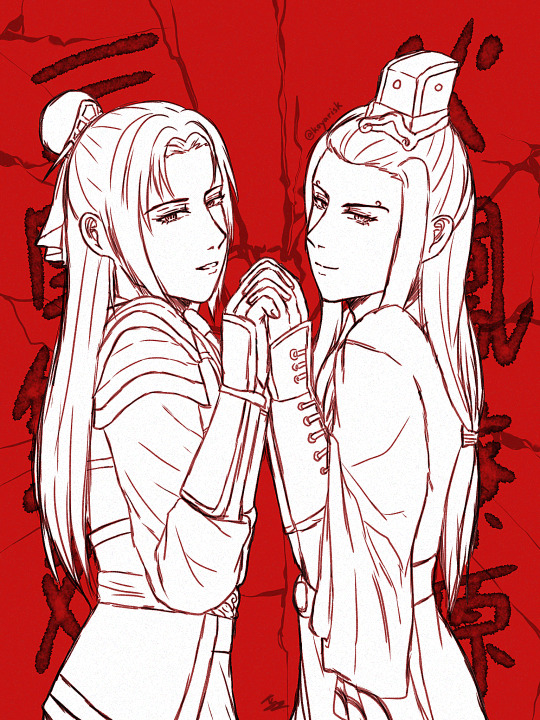

My coloring [The Ravages Of Time manga, Chapter 568]

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Ravages Of Time - Ch 149 Lineart & coloring :me

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

evil guy and his evil cat but the cat is actually the mama and the guy is her kitten,,

#am i making sense here#its eepy time when ravage says its eepy time and not a moment later#gfhrgufh i should be animating rn but imso im so like urghfhg#my art#soundwave#ravage#laserbeak#buzzsaw#rumble#frenzy

7K notes

·

View notes

Text

According to auto-translate, I think The Ravages of Time (火鳳燎原) season 2 will be released some time next year? I can't wait to see how Cao Cao is portrayed in this animation. Also looking forward to other characters who had yet to appear. <3

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Your father [Ma Teng] was a hero of Liangzhou! Don't let this decision destroy his illustrious name!

chapter 608, The Ravages of Time

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

On sworn fathers and sons

As I was translating the card for episode 6 of The Ravages of Time, I came across a conundrum. The relationship between Dong Zhuo and Lü Bu is typically translated into English as “adopted father and son”, but I feel like that’s a bit misleading. It is a similar concept to the “sworn brotherhood”, with the classic example being Liu Bei, Guan Yu and Zhang Fei, but it isn’t as easily adapted into English language and Western culture.

I suppose it’s tempting to try and push a square peg into a round hole and try to find similarities between the concepts we are accustomed to and the ones we see in different cultures – I readily admit I’ve done that myself, even in the translations for The Ravages of Time, albeit for a very minor character. This approach has its merits, and certainly makes the media more accessible to the wider audience. But I think it’s at least fun and at most quite helpful to try and figure out what it really means, especially for the cases where the differences become important.

Even just looking into the history of specifically the Three Kingdoms era, there are many kinds of relationships that are distinctly different from one another, with regards to if the people involved changed surnames, had inheritance rights, as well as how they were regarded by their peers. They are all typically translated into English as “adoption”, which automatically loses some of the context provided by the specific term.

Looking into a dictionary, there are quite a few terms that can be translated as “adopted son” into English. They don’t all mean the same thing, and while some are much more likely to turn up in various media, I’m going to go over all that I’ve come across one by one. That said, there is some debate on how these terms are meant to be used and sometimes the meaning is a bit muddled even in the writings of native speakers.

I will include the more literal meanings of the terms here, mostly for convenience of referring to different words without overloading this post with Chinese characters or pinyin.

义子 [yì zǐ] – lit. “sworn/righteous” son. This is probably the most common one and the one used for Lü Bu regarding Dong Zhuo. The character 义 is also the one used in “sworn brother”, and generally “sworn son” can mean the child of a sworn brother/sister. While there are some rituals involved in recognizing someone as a “sworn son”, it is not a legal process but rather a folk tradition and therefore did not give the right to inherit.

Since “sworn sons” were often adults (like in Lü Bu’s case, for example), it wasn’t uncommon for someone to enter such a relationship specifically for the perks of getting a talented heir/powerful patron.

To better illustrate the relationship between Lü Bu and Dong Zhuo, I’ll once more turn to Records of the Three Kingdoms andBook of Later Han (the passages are almost identical in both chronicles, and I used both sources to make the translation more accurate; that said, I found the Book of Later Han version slightly easier to understand in most places) and their description of Lü Bu’s decision to kill Dong Zhuo in a conversation with Wang Yun.

"From the start, Minister over the Masses Wang Yun had a close relationship with Lü Bu, having received him kindly. After Lü Bu came to Wang Yun, he complained how Dong Zhuo had tried to kill him several times. At the time, Wang Yun and the Vice Director of the Imperial Secretariat Shisun Rui were plotting against Dong Zhuo, so he offered Lü Bu to join them. Lü Bu said, “When we’re like father and son?” Wang Yun said, “Your surname is Lü, you are not his flesh and blood. Today he didn’t have time to worry about your death, what do you mean by father and son? When he threw a halberd, did he also feel like you’re father and son?” Lü Bu then agreed to kill Dong Zhuo himself, as is described in Dong Zhuo’s biography. Wang Yun gave Lü Bu the title General of Spirited Strength [1], granted him the Insignia [2], made him a Three Dignitaries Equal [3], and gave him the Wenxian county."

[1] General of Spirited Strength – uh. Look. I kind of went with the poetic feel, but just for reference, this has been translated by Moss Roberts as “General Known for Vigor-in-Arms” and by Charles Henry Brewitt-Taylor as "General Who Demonstrates Grand and Vigor Courage in Arms"

[2] Insignia – it’s kind of… a symbol of (usually military) power? Like, you have this thing, you can command/execute/etc. people even if you technically shouldn’t have the right to do so. They were usually granted temporarily for a particular mission.

[3] Three Dignitaries Equal – someone who isn’t one of the Three Dignitaries (included Minister over the Masses – Wang Yun himself, Minister of Works and Defender-in-Chief; also known as the Three Dukes), but has all the rights of one.

(This has nothing to do with the sworn sons thing, but Shisun Rui’s title literally means “charioteering archer” despite being an administrative rather than a military position. I just think that’s neat.)

养子 [yǎng zǐ] – another common one, lit. “raised/supported” son. One difference between the “sworn son” and “raised son” is in the actual act of raising – while the sworn son is typically of age, a “raised son” is a child and needs to be looked after. In modern society, this is the word used for what we would typically consider as official adoption or fostering, and comes with full inheritance rights (the legal translation seems to be fostering, but, uh, I’m not a lawyer).

That said, the word had existed for much longer than the modern legal system; so in the more historical context this would be a bit more muddled and sometimes used almost synonymously to a “sworn son”, just with a bit more legal rights.

One famous historical example of a “raised son” is Liu Feng, who was adopted by Liu Bei. At the time, Liu Bei didn’t have a heir, but later, after his biological sons were born, he stopped regarding Liu Feng as highly as before, eventually leading to mutual resentment and Liu Bei blaming Liu Feng for Guan Yu’s death and sentencing him to death (or, more accurately, ordering Liu Feng to kill himself). Even before that though, Liu Bei’s heir was announced to be his son by blood, Liu Shan.

干儿(子)[gān ér (zǐ)]- a “nominal” son, also sometimes translated as “godson”. Is usually used as a complete synonym for “sworn son” or “raised son”, but I believe is a bit more modern and appeared with the decline in the usage of “sworn son”.

契子 [qìzǐ] – lit. “contract” son. A dialect variant of “nominal son” used in Hakka Chinese. Some Chinese-English dictionaries seem to give the meaning as “adopted son” by default, but in Chinese-Chinese encyclopedias I don’t seem to see it for dialects other than the Hakka varieties – I might be wrong though.

寄子/儿 [jìzǐ/ér] – lit. “entrusted/dependent” son. That’s the one that was probably the most confusing for me. For one, it’s used to describe a similar relationship in Japanese culture. I suspected it might be a less-used spelling of “succeeding son” (see later) – the pronunciation is the same, and some of the descriptions of the terms match – but the online consensus seems to be that “dependent son” is more synonymous to “nominal son”. Unfortunately, the search for specifics is made difficult by the existence of a Japanese manga of the same title.

假子 [jiǎzǐ] – lit. “false/fake” son. It can be used as a synonym for the previous variants, or for a son of a previous husband/wife, and seems to carry a negative undertone, sometimes used to express dislike of the person it refers to or the fact that he’s not considered by the speaker to be a “real” child of the family. In the examples I’ve seen it’s only ever been used by outsiders, not by the people actually involved.

嗣子 [sìzǐ] – lit. “inheriting” son, can confusingly also mean an heir, an official son from a wife rather than a concubine. This refers specifically to someone who is going to inherit after a person, and I believe is somewhat limited to nephews. Gaining this status meant severing the legal connection with your own parents and becoming, for all intents and purposes, your uncle’s son.

祧子 [tiāozǐ] – lit. “picked” son. Unlike the “inheriting son”, didn’t need to sever ties with their original family and didn’t need to call the uncle “father”. A bit less formal than “inheriting son” but allowed one to be counted as a member of both families essentially.

继子 [jìzǐ] – lit. “succeeding” son, similar to the previous ones, but even less strict, with this relationship not being limited to nephews. Sometimes also refers to sons of ex-husbands/ex-wives.

螟蛉/螟蛉子/蛉子 [mínglíng/mínglíngzǐ/míngzǐ] – lit. “corn earworm” (or the larvae of a bunch of insects – you know what, this isn’t a biology post, whatever. You get the point). It’s a metaphor coming from an ancient misunderstanding of how they propagated. Basically, some wasps often use the larvae to store eggs (and later as food for the hatched eggs), but people used to think that wasps didn’t have children of their own and instead “adopted” the earworms. Is used as a synonym for “sworn son” or “raised son”.

微子 [wēizǐ] – lit. something like… “a little bit” son? Used to refer to the son not from the legitimate wife. Mostly this refers to the first ruler of the Song dynasty, and I’ve never come across its “illegitimate son” meaning, much less the “adopted son” given in some dictionaries. (Fun fact for Weil specially: since the “子” character means “particle” as well as “son”, 中微子 is how neutrino is spelled.)

This is all the options I’ve found! Some are very niche or even questionable, but I wanted to be thorough and cover all the possibilities one might come across in various Chinese media.

To finish this off, with so many different ways to take a child into the family, there is also a distinct word to describe children of one’s own blood – 亲子 [qīnzǐ].

At the end of the day, especially in historical context, I think it’s important to remember that many of the relationships described above were not codified, or were only partially codified. The specific dynamic relied on the interpretation of a particular person, and as we’ve seen with some of them, could even be revoked at any moment when it no longer suited the needs of the individuals involved.

I hope this was helpful!

9 notes

·

View notes