#the us/uk queer movements get to be represented by actual queer people

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

boy's love / yaoi / danmei & dangai are not queer representation and queer art. or to be exact, it's more complicated than that; asian queer movements in real life express themselves and make their statements through other channels unrelated to fandom. the rise and increasing acceptance of danmei & dangai media isn't a brave push against censorship, it's the age-old story of pink economy exploitation; you just don't know how censorship states function. supporting actual queer asian peoples is not the same as loving and supporting yaoi.

not to be completely disillusioned and cynical. but the c-media circle on tumblr and every single eng-speaking site is so dreadfully racist. (us/uk) chinese diaspora are most guilty of this behaviour while also being the most vocal about racism against chineseness. how many times do i have to witness a racist post made under the guise of "fandom is just for fun!!!!"

#me is mark#are there any intl cmedia fans who actually understand asian censorship states and their queer minorities?#and the politics there?#the us/uk queer movements get to be represented by actual queer people#queer academia and literature and movies and performance art and documentaries#and queer figures who put themselves out there#but chinese queer activism is represented by capitalist cash-ins exploiting the yaoi market?#acted and produced by the same straight and conforming agents who make other mainstream dramas?

6 notes

·

View notes

Note

Just going a little more into the whole thing about understanding young dnp differently now that we have the whole story, something else I have been thinking about so much is queer rights movements and legislation in the uk. Im a good decade younger than them, when gay marriage was legalised I was 12. I was old enough to understand what it was, but i didnt really have any sort of understanding of how it affected me bc i hadnt even started to figure out who i was yet. To me it feels like so long ago, i feel like ive always had it, which is an immense privelage. But dan and phil were not only already in their mid twenties and in a 5 year strong relationship, they already had an active career on youtube. Watching ditl in london, that was the year gay marriage was legalised in the uk. That was who they already were as people and as creators. I cant imagine what it would have been like when the bill passed. They were still so closeted, but that was also such a big win for them and the whole community. I wonder if at the time it still seemed like such a far fetched thing anyway, bc i cant imagine they were even close to wanting to come out yet. Idk if they thought at that point they ever would. And then i think about the fact that they had been in a committed relationship for 5 years at that point. I cant imagine what it would be like to be with my self-proclaimed 'soulmate' and know that you can not legally recognize your relationship. To not know if you ever would. Which then makes sense as to why its not necessarily a priority for them now. Idk, its like you said. Its strange and a little sad to know now who they were then, but in the end it all worked out. They made it to the other side and i could not be happier for them.

oh wow yeah!! im about the same age as you I think, and yes it was much the same for me in the sense that I was aware of same-sex marriage legislation being passed but I had no real grasp on like, what that actually meant for people lol. this got me curious so I went back and tried to see if they ever even talked about same-sex marriage being legalized in the UK. from what I can see they didn't tweet about it at all, and im assuming they didn't make any other statements about it? then in 2015 when it was legalized in the US, they did both tweet, but quite impersonally (I mean I get why im not saying they should've been making grand statements or anything like that). like even setting their relationship aside for a moment, I can imagine it was incredibly difficult for them as two closeted gay men to navigate how to address things like this publicly—obviously when it came to the UK they didn't even address it at all. but im sure it was a huge deal for them to see it legalized just in the sense of what it represents. but even with this landmark that represented lgbtq+ ppl being more generally accepted, they were still closeted, so there was only so much they could say. like I would love to know their thoughts that they couldnt express in 2013/2014/2015 on what it meant to them! but also how it affected them that they couldnt share their thoughts

but then yeah I do wonder how it was for them in the context of their relationship. bc like before it wasn't even a possibility that they could get married. and then they did have the option, but actually not really because they were still closeted, so even if they wanted to they still technically couldnt without outing themselves. but obviously just knowing you now have the option when you couldnt before meant a lot to them im sure

16 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Tweet here, article here. Highly recommend reading the whole article, but just a few choice quotes: I want to first question whether trans-exclusionary feminists are really the same as mainstream feminists. If you are right to identify the one with the other, then a feminist position opposing transphobia is a marginal position. I think this may be wrong. My wager is that most feminists support trans rights and oppose all forms of transphobia. So I find it worrisome that suddenly the trans-exclusionary radical feminist position is understood as commonly accepted or even mainstream. I think it is actually a fringe movement that is seeking to speak in the name of the mainstream, and that our responsibility is to refuse to let that happen. -- AF: One example of mainstream public discourse on this issue in the UK is the argument about allowing people to self-identify in terms of their gender. In an open letter she published in June, JK Rowling articulated the concern that this would "throw open the doors of bathrooms and changing rooms to any man who believes or feels he’s a woman", potentially putting women at risk of violence. JB: If we look closely at the example that you characterise as “mainstream” we can see that a domain of fantasy is at work, one which reflects more about the feminist who has such a fear than any actually existing situation in trans life. The feminist who holds such a view presumes that the penis does define the person, and that anyone with a penis would identify as a woman for the purposes of entering such changing rooms and posing a threat to the women inside. It assumes that the penis is the threat, or that any person who has a penis who identifies as a woman is engaging in a base, deceitful, and harmful form of disguise. This is a rich fantasy, and one that comes from powerful fears, but it does not describe a social reality. Trans women are often discriminated against in men’s bathrooms, and their modes of self-identification are ways of describing a lived reality, one that cannot be captured or regulated by the fantasies brought to bear upon them. The fact that such fantasies pass as public argument is itself cause for worry. -- AF: The consensus among progressives seems to be that feminists who are on JK Rowling’s side of the argument are on the wrong side of history. Is this fair, or is there any merit in their arguments? JB: Let us be clear that the debate here is not between feminists and trans activists. There are trans-affirmative feminists, and many trans people are also committed feminists. So one clear problem is the framing that acts as if the debate is between feminists and trans people. It is not. One reason to militate against this framing is because trans activism is linked to queer activism and to feminist legacies that remain very alive today. Feminism has always been committed to the proposition that the social meanings of what it is to be a man or a woman are not yet settled. We tell histories about what it meant to be a woman at a certain time and place, and we track the transformation of those categories over time. We depend on gender as a historical category, and that means we do not yet know all the ways it may come to signify, and we are open to new understandings of its social meanings. It would be a disaster for feminism to return either to a strictly biological understanding of gender or to reduce social conduct to a body part or to impose fearful fantasies, their own anxieties, on trans women... Their abiding and very real sense of gender ought to be recognised socially and publicly as a relatively simple matter of according another human dignity. The trans-exclusionary radical feminist position attacks the dignity of trans people. -- First, one does not have to be a woman to be a feminist, and we should not confuse the categories. Men who are feminists, non-binary and trans people who are feminists, are part of the movement if they hold to the basic propositions of freedom and equality that are part of any feminist political struggle. When laws and social policies represent women, they make tacit decisions about who counts as a woman, and very often make presuppositions about what a woman is. We have seen this in the domain of reproductive rights. So the question I was asking then is: do we need to have a settled idea of women, or of any gender, in order to advance feminist goals? I put the question that way… to remind us that feminists are committed to thinking about the diverse and historically shifting meanings of gender, and to the ideals of gender freedom. By gender freedom, I do not mean we all get to choose our gender. Rather, we get to make a political claim to live freely and without fear of discrimination and violence against the genders that we are. Many people who were assigned “female” at birth never felt at home with that assignment, and those people (including me) tell all of us something important about the constraints of traditional gender norms for many who fall outside its terms. Feminists know that women with ambition are called “monstrous” or that women who are not heterosexual are pathologised. We fight those misrepresentations because they are false and because they reflect more about the misogyny of those who make demeaning caricatures than they do about the complex social diversity of women. Women should not engage in the forms of phobic caricature by which they have been traditionally demeaned. And by “women” I mean all those who identify in that way. -- AF: Threats of violence and abuse would seem to take these “anti-intellectual times” to an extreme. What do you have to say about violent or abusive language used online against people like JK Rowling? JB: I am against online abuse of all kinds. I confess to being perplexed by the fact that you point out the abuse levelled against JK Rowling, but you do not cite the abuse against trans people and their allies that happens online and in person. I disagree with JK Rowling's view on trans people, but I do not think she should suffer harassment and threats. Let us also remember, though, the threats against trans people in places like Brazil, the harassment of trans people in the streets and on the job in places like Poland and Romania – or indeed right here in the US. So if we are going to object to harassment and threats, as we surely should, we should also make sure we have a large picture of where that is happening, who is most profoundly affected, and whether it is tolerated by those who should be opposing it. It won’t do to say that threats against some people are tolerable but against others are intolerable. -- It is painful to see that Trump’s position that gender should be defined by biological sex, and that the evangelical and right-wing Catholic effort to purge “gender” from education and public policy accords with the trans-exclusionary radical feminists' return to biological essentialism. It is a sad day when some feminists promote the anti-gender ideology position of the most reactionary forces in our society. -- My point in the recent book is to suggest that we rethink equality in terms of interdependency. We tend to say that one person should be treated the same as another, and we measure whether or not equality has been achieved by comparing individual cases. But what if the individual – and individualism – is part of the problem? It makes a difference to understand ourselves as living in a world in which we are fundamentally dependent on others, on institutions, on the Earth, and to see that this life depends on a sustaining organisation for various forms of life. If no one escapes that interdependency, then we are equal in a different sense. We are equally dependent, that is, equally social and ecological, and that means we cease to understand ourselves only as demarcated individuals. If trans-exclusionary radical feminists understood themselves as sharing a world with trans people, in a common struggle for equality, freedom from violence, and for social recognition, there would be no more trans-exclusionary radical feminists. But feminism would surely survive as a coalitional practice and vision of solidarity.

#terfs/swerfs don't even breathe on this post#same for 'devil's advocates' and sympathizers#transphobia#feminism#judith butler#mlop#jk rowling#terfs#bioessentialism#radical feminism#fauxminism#gender#trans exclusionary radical fauxminists#lgbtq#MOGII#trans

39 notes

·

View notes

Text

Judith Butler on the culture wars, JK Rowling and living in “anti-intellectual times”

Thirty years ago, the philosopher Judith Butler*, now 64, published a book that revolutionised popular attitudes on gender. Gender Trouble, the work she is perhaps best known for, introduced ideas of gender as performance. It asked how we define “the category of women” and, as a consequence, who it is that feminism purports to fight for. Today, it is a foundational text on any gender studies reading list, and its arguments have long crossed over from the academy to popular culture. In the three decades since Gender Trouble was published, the world has changed beyond recognition. In 2014, TIME declared a “Transgender Tipping Point”. Butler herself has moved on from that earlier work, writing widely on culture and politics. But disagreements over biological essentialism remain, as evidenced by the tensions over trans rights within the feminist movement. How does Butler, who is Maxine Elliot Professor of Comparative Literature at Berkeley, see this debate today? And does she see a way to break the impasse? Butler recently exchanged emails with the New Statesman about this issue. The exchange has been edited. *** Alona Ferber: In Gender Trouble, you wrote that "contemporary feminist debates over the meanings of gender lead time and again to a certain sense of trouble, as if the indeterminacy of gender might eventually culminate in the failure of feminism”. How far do ideas you explored in that book 30 years ago help explain how the trans rights debate has moved into mainstream culture and politics? Judith Butler: I want to first question whether trans-exclusionary feminists are really the same as mainstream feminists. If you are right to identify the one with the other, then a feminist position opposing transphobia is a marginal position. I think this may be wrong. My wager is that most feminists support trans rights and oppose all forms of transphobia. So I find it worrisome that suddenly the trans-exclusionary radical feminist position is understood as commonly accepted or even mainstream. I think it is actually a fringe movement that is seeking to speak in the name of the mainstream, and that our responsibility is to refuse to let that happen.

AF: One example of mainstream public discourse on this issue in the UK is the argument about allowing people to self-identify in terms of their gender. In an open letter she published in June, JK Rowling articulated the concern that this would "throw open the doors of bathrooms and changing rooms to any man who believes or feels he’s a woman", potentially putting women at risk of violence. JB: If we look closely at the example that you characterise as “mainstream” we can see that a domain of fantasy is at work, one which reflects more about the feminist who has such a fear than any actually existing situation in trans life. The feminist who holds such a view presumes that the penis does define the person, and that anyone with a penis would identify as a woman for the purposes of entering such changing rooms and posing a threat to the women inside. It assumes that the penis is the threat, or that any person who has a penis who identifies as a woman is engaging in a base, deceitful, and harmful form of disguise. This is a rich fantasy, and one that comes from powerful fears, but it does not describe a social reality. Trans women are often discriminated against in men’s bathrooms, and their modes of self-identification are ways of describing a lived reality, one that cannot be captured or regulated by the fantasies brought to bear upon them. The fact that such fantasies pass as public argument is itself cause for worry. AF: I want to challenge you on the term “terf”, or trans-exclusionary radical feminist, which some people see as a slur. JB: I am not aware that terf is used as a slur. I wonder what name self-declared feminists who wish to exclude trans women from women's spaces would be called? If they do favour exclusion, why not call them exclusionary? If they understand themselves as belonging to that strain of radical feminism that opposes gender reassignment, why not call them radical feminists? My only regret is that there was a movement of radical sexual freedom that once travelled under the name of radical feminism, but it has sadly morphed into a campaign to pathologise trans and gender non-conforming peoples. My sense is that we have to renew the feminist commitment to gender equality and gender freedom in order to affirm the complexity of gendered lives as they are currently being lived. AF: The consensus among progressives seems to be that feminists who are on JK Rowling’s side of the argument are on the wrong side of history. Is this fair, or is there any merit in their arguments? JB: Let us be clear that the debate here is not between feminists and trans activists. There are trans-affirmative feminists, and many trans people are also committed feminists. So one clear problem is the framing that acts as if the debate is between feminists and trans people. It is not. One reason to militate against this framing is because trans activism is linked to queer activism and to feminist legacies that remain very alive today. Feminism has always been committed to the proposition that the social meanings of what it is to be a man or a woman are not yet settled. We tell histories about what it meant to be a woman at a certain time and place, and we track the transformation of those categories over time. We depend on gender as a historical category, and that means we do not yet know all the ways it may come to signify, and we are open to new understandings of its social meanings. It would be a disaster for feminism to return either to a strictly biological understanding of gender or to reduce social conduct to a body part or to impose fearful fantasies, their own anxieties, on trans women... Their abiding and very real sense of gender ought to be recognised socially and publicly as a relatively simple matter of according another human dignity. The trans-exclusionary radical feminist position attacks the dignity of trans people. AF: In Gender Trouble you asked whether, by seeking to represent a particular idea of women, feminists participate in the same dynamics of oppression and heteronormativity that they are trying to shift. In the light of the bitter arguments playing out within feminism now, does the same still apply? JB: As I remember the argument in Gender Trouble (written more than 30 years ago), the point was rather different. First, one does not have to be a woman to be a feminist, and we should not confuse the categories. Men who are feminists, non-binary and trans people who are feminists, are part of the movement if they hold to the basic propositions of freedom and equality that are part of any feminist political struggle. When laws and social policies represent women, they make tacit decisions about who counts as a woman, and very often make presuppositions about what a woman is. We have seen this in the domain of reproductive rights. So the question I was asking then is: do we need to have a settled idea of women, or of any gender, in order to advance feminist goals? I put the question that way… to remind us that feminists are committed to thinking about the diverse and historically shifting meanings of gender, and to the ideals of gender freedom. By gender freedom, I do not mean we all get to choose our gender. Rather, we get to make a political claim to live freely and without fear of discrimination and violence against the genders that we are. Many people who were assigned “female” at birth never felt at home with that assignment, and those people (including me) tell all of us something important about the constraints of traditional gender norms for many who fall outside its terms. Feminists know that women with ambition are called “monstrous” or that women who are not heterosexual are pathologised. We fight those misrepresentations because they are false and because they reflect more about the misogyny of those who make demeaning caricatures than they do about the complex social diversity of women. Women should not engage in the forms of phobic caricature by which they have been traditionally demeaned. And by “women” I mean all those who identify in that way. AF: How much is toxicity on this issue a function of culture wars playing out online? JB: I think we are living in anti-intellectual times, and that this is evident across the political spectrum. The quickness of social media allows for forms of vitriol that do not exactly support thoughtful debate. We need to cherish the longer forms. AF: Threats of violence and abuse would seem to take these “anti-intellectual times” to an extreme. What do you have to say about violent or abusive language used online against people like JK Rowling. JB: I am against online abuse of all kinds. I confess to being perplexed by the fact that you point out the abuse levelled against JK Rowling, but you do not cite the abuse against trans people and their allies that happens online and in person. I disagree with JK Rowling's view on trans people, but I do not think she should suffer harassment and threats. Let us also remember, though, the threats against trans people in places like Brazil, the harassment of trans people in the streets and on the job in places like Poland and Romania – or indeed right here in the US. So if we are going to object to harassment and threats, as we surely should, we should also make sure we have a large picture of where that is happening, who is most profoundly affected, and whether it is tolerated by those who should be opposing it. It won’t do to say that threats against some people are tolerable but against others are intolerable. AF: You weren't a signatory to the open letter on “cancel culture” in Harper's this summer, but did its arguments resonate with you? JB: I have mixed feelings about that letter. On the one hand, I am an educator and writer and believe in slow and thoughtful debate. I learn from being confronted and challenged, and I accept that I have made some significant errors in my public life. If someone then said I should not be read or listened to as a result of those errors, well, I would object internally, since I don't think any mistake a person made can, or should, summarise that person. We live in time; we err, sometimes seriously; and if we are lucky, we change precisely because of interactions that let us see things differently. On the other hand, some of those signatories were taking aim at Black Lives Matter as if the loud and public opposition to racism were itself uncivilised behaviour. Some of them have opposed legal rights for Palestine. Others have [allegedly] committed sexual harassment. And yet others do not wish to be challenged on their racism. Democracy requires a good challenge, and it does not always arrive in soft tones. So I am not in favour of neutralising the strong political demands for justice on the part of subjugated people. When one has not been heard for decades, the cry for justice is bound to be loud. AF: This year, you published, The Force of Nonviolence. Does the idea of “radical equality”, which you discuss in the book, have any relevance for the feminist movement? JB: My point in the recent book is to suggest that we rethink equality in terms of interdependency. We tend to say that one person should be treated the same as another, and we measure whether or not equality has been achieved by comparing individual cases. But what if the individual – and individualism – is part of the problem? It makes a difference to understand ourselves as living in a world in which we are fundamentally dependent on others, on institutions, on the Earth, and to see that this life depends on a sustaining organisation for various forms of life. If no one escapes that interdependency, then we are equal in a different sense. We are equally dependent, that is, equally social and ecological, and that means we cease to understand ourselves only as demarcated individuals. If trans-exclusionary radical feminists understood themselves as sharing a world with trans people, in a common struggle for equality, freedom from violence, and for social recognition, there would be no more trans-exclusionary radical feminists. But feminism would surely survive as a coalitional practice and vision of solidarity. AF: You have spoken about the backlash against “gender ideology”, and wrote an essay for the New Statesman about it in 2019. Do you see any connection between this and contemporary debates about trans rights? JB: It is painful to see that Trump’s position that gender should be defined by biological sex, and that the evangelical and right-wing Catholic effort to purge “gender” from education and public policy accords with the trans-exclusionary radical feminists' return to biological essentialism. It is a sad day when some feminists promote the anti-gender ideology position of the most reactionary forces in our society AF: What do you think would break this impasse in feminism over trans rights? What would lead to a more constructive debate? JB: I suppose a debate, were it possible, would have to reconsider the ways in which the medical determination of sex functions in relation to the lived and historical reality of gender.

22 September 2020

*Judith Butler goes by she or they

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

the idea that any significant portion of women irrationally hate men is anecdotal, it is not reality:

In Study 1 (n = 1,664), feminist and nonfeminist women displayed similarly positive attitudes toward men. Study 2 (n = 3,892) replicated these results in non-WEIRD countries and among male participants. Study 3 (n = 198) extended them to implicit attitudes. Investigating the mechanisms underlying feminists’ actual and perceived attitudes, Studies 4 (n = 2,092) and 5 (nationally representative UK sample, n = 1,953) showed that feminists (vs. nonfeminists) perceived men as more threatening, but also more similar, to women. Participants also underestimated feminists’ warmth toward men, an error associated with hostile sexism and a misperception that feminists see men and women as dissimilar. Random-effects meta-analyses of all data (Study 6, n = 9,799) showed that feminists’ attitudes toward men were positive in absolute terms and did not differ significantly from nonfeminists'. An important comparative benchmark was established in Study 6, which showed that feminist women's attitudes toward men were no more negative than men's attitudes toward men. We term the focal stereotype the 'misandry myth' in light of the evidence that it is false and widespread.

This trope has been used to delegitimize and discredit the movement, has deterred women from joining it, and motivated men to oppose it, sometimes with violence (Anderson, 2015; Ging, 2017; Roy et al., 2007).

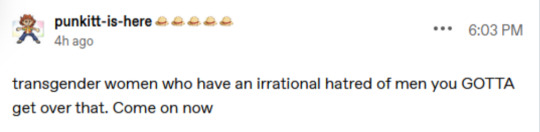

'but punkitt didn't say feminists, she said trans women' doesn't cut it because it's intellectually dishonest and condescending to suggest any trans women are hating men for irrational reasons detached entirely from gender politics.

the trans women on this website critiquing men and masculinity are transfeminists, people who live at the intersection of transphobia denying our womanhood while misogyny towards us affirms it, the most jaded of whom have been mistreated by the men in their lives — and have seen other trans women treated the same — so frequently they worry trans feminine separatism is the only way they'll get a safe space.

to reframe what i just said, because people never want to acknowledge this reality: there is no self described trans feminine separatist who has reached that conclusion without already having tried to participate in the broader trans and lgbtqia communities only to find herself mistreated by people she keeps being told are her brothers who are going to stand with her against oppression.

this has nothing to do with testosterone being evil or anything biologically innate to men, it is entirely about the systemic privilege afforded by patriarchy which is reflected in queer communities created under patriarchy: in a trans accepting space, trans men are men and trans women are women, with all of the sociopolitical and cultural baggage that comes with it.

the reason my reply to her post encouraged her to take a step back from the argument and take the time to get a better understanding of both transfeminism and how dire things are for less popular trans women on this website is because this addition to the original post is very antagonistic towards other trans women in a way that's extremely sad to see.

as i stated in my reply to her post, as someone who knows the sort of trans women being chided in the original post, nothing about their (as i've discussed, entirely rational) disdain towards men is rooted in bioessentialism: never do i, an entirely not passing trans feminine person living in a conservative area early in my medical transition who would risk violence presenting feminine and thus continues to present nonbinary masculine offline, feel like i am being excluded by these trans women, because their framework of transfeminism doesn't determine a person's gender by judging their appearance. judging the validity of a trans woman's identity by how feminine she presents is transmisogynist, it's textbook transphobia intersecting with misogyny. there are trans women who have internalized misogyny and transmisogyny, but that's not who she's addressing.

her post doesn't actually say anything positive, all it accomplishes is condescending to a bunch of the vulnerable trans women who don't have her follower base, but because 'she's literally just saying to be nice!' people will go to bat to defend her intellectually incurious, vibes-based politics.

she is attending a house party, yelling out the open window at the trans women on the lawn — who are discussing how cruel the people at the party were — that maybe if they were nicer to men things would be going better for them.

it's condescending, of course it's going to set some people off, and of course there are going to be trans women lamenting the way she approaches community issues haphazardly with no regard for the rest of the people she apparently expects to be in community with her, given she's making posts addressing them, but then turns around and calls people criticizing her — from a position of greater understanding of the issues she's discussing — stupid or dumbasses, as if they're contemptible, and not to be listened to as an equal with a different point of view who were hurt by her original post being flippant and rude. you can make the argument that people are being too mean to her, but when you've been watching trans women on tumblr deal with harassment from the website's CEO, TERFs and trans masculine users, it's a real kick in the teeth to see a popular trans feminine blogger telling you to be nicer to men.

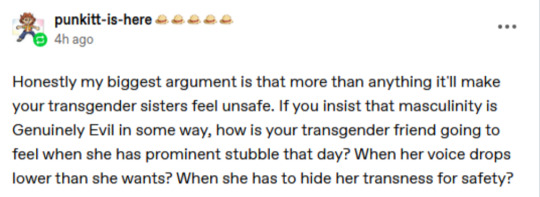

I'm absolutely losing my mind seeing "We need to not treat men and masculinity as inherently evil and worthy of hatred, and not fall back into biological and gender essentialism because that hurts everyone, including trans women" being misinterpreted as "Women need to stop oppressing men", "I think trans women are actually men" or "You specifically who have trauma around men need to get over it because men are the real victims". It's so willfully disingenuous. It makes me sick how willing people are to read in bad faith, especially how willing other trans women are to suddenly start harassing and dogpiling another trans woman.

I am a trans woman too, I understand what it's like to feel unsafe, but it helps no one this cynical attitude that crops up every time someone suggests being kind to men in our lives. "You could save a man you know from falling down the alt-right pipeline" is not the same as "It's your fault that men murder you". "There are people who could be on our side if we don't meet them with immediate hostility" is not the same as "You need to shut up and stop criticizing power structures for the sake of your oppressors' feelings" (I promise there are a lot of people who can be taught about their complicity in oppression without immediately shutting down but you need to work with them). This kind of attitude isn't somehow more informed or correct. It's just lashing out to avoid considering one's own agency.

Making a better, safer world for ourselves requires all kinds of work, but it's always work. It's hard to try to reach out to people who could very realistically harm us, it's work that not all of us can afford to or are able to do and that's fine because we're all just trying to survive. But some of you would rather condescend, tear each other down, and make more enemies before even considering it a possibility.

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

Here's my problem with the emotional left, and yes, I am collectivizing here. Don't read too much into it, I'm actually addressing a couple specific individuals -- though I'm positive they represent a phenomenon that extends well beyond our social circle. [...] With that said, I'm so glad you guys are so heavily invested in politics now that your days of sharing fucking top ten lists from BuzzFeed and Queer Voices via Mic, Vox, and HuffPo have been replaced with watch dog articles monitoring Trump's every waking movement from BuzzFeed, Mic, Vox, and HuffPo. And fuck off if you think because that wasn't a comprehensive list you're safe. Listen, I don't care if you're sharing shit from the UK as if that somehow makes it the objective authority on all things "keeping Trump in check." I don't even care that you're filling up an entire month's worth of space on your timeline with articles about Trump. You're the fucking "resistance" now against the scary orange dictator, we fucking get it. Now's your chance at being that revolutionary fighter you've been dreaming about since childhood. No, my problem here is that I see you playing the watch dog role ALL OF A SUDDEN, even though all this time you were doing everything you claimed the right was doing (fear-mongering, war-mongering, all the mongering), and now all of a sudden you're STILL DOING EXACTLY WHAT YOU'RE CLAIMING THE RIGHT IS DOING. I mean, I think it's great that you're starting to actually be critical of your president. But where the fuck were you over the past eight years? Do you know how much shit the Obama administration has done to run against your beliefs? Where the fuck were you? Republicans didn't even have the majority in Congress for a long fucking time until recently. No, I'll tell you where you were. In your own fucking asses. It should be very clear to you that you have an EXTREME political bias with a fucking BLINDSPOT for everything shady that occurs on "your side" and that you are the retarded ADHD children of the West that everyone likes to make fun of with the label of "Millennial" because of how easy it is to manipulate and (I love that I get to use this term) gaslight you via oversaturation of sensationalist headlines and "articles." What gets me is that you don't see this. You don't recognize this pattern. In fact, with every ounce of your being, you honestly think you're above it. And, once again, fuck off if you take exception to me saying "your side," because while I have historically been one of the fewer motherfuckers out there that actually gives a shit about nuance and individual perspective apart from the collective, YOU and everyone else on "your side" have been the ones whining and screaming and crying for the opposite. Because it gives you some invisible evil organization to fight against which in turn gives you moral solidarity or some shit but is really just rationalizing being evil and shitty for the sake of your collectivist identitarian politics. And now, it isn't even about left versus right anymore. It's about the collective versus the individual. Which is to say, authoritarianism (because how else are you going to enforce the collective) versus individualism. You've bought into the notion of "us versus them" or, worse, you actually believe that you're above that and yet you still play the game because "the other side is doing it, so why shouldn't I?" (I'm looking at a lot of you internet tough guys on the right, too) You've turned into media parrots. You've lost the ability to think critically and challenge your own points of view. You think you still have it in you, but I assure you, you do not. And no, saying some shit like, "well I did leave a comment once on someone else's post about Obama doing bad stuff that one time" does not somehow wash that bias and hypocrisy off you. Once again, where was this watch dog viva la revolution bullshit during the past eight years? What about all the rhetoric ramping up for conflict against Russia in the preceding four years? Oh, didn't notice it then? Fuckin' CNN and HuffPo didn't have enough "Obama Flirts with Nuclear Holocaust with Russia while on the Golf Course, click here to find out why" headlines for you to virtue signal and share on your wall? Actually, I'm fucking positive a few (and I mean a few) were out there but I'm just as positive you didn't give a shit about it back then. No, you're clearly not interested in actually seeing things from the other side. You never were. Like I said, I don't care about how you choose to manifest that behavior. But at least cop to it. You know, maybe use a trigger warning or some shit that lets everyone else know to stay away from the crazy cult people.

0 notes