#the stories of john cheever

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

The Stories of John Cheever

Purple Violets

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

"The Death of Justina" (The Stories of John Cheever)

Cheever lets his freak flag fly and gets a little libertarian at least as far as local politics are concerned.

So here's that Mad Men inspired by John Cheever story. The main character is in advertising and just drops the fact that he quit drinking and smoking on his doctor's advice so he was already in a bad mood. So he went into his advertising office and his wife's cousin dies on the couch.

So Moses, the protagonist gets stuck at the office, trying to write ad copy. Because the other ad man had to go home because of another excuse and the boss with a satanic smile tells him to write the damn ad. He writes:

"Are you falling out of love with your image in the looking glass? Does your face in the morning seem rucked and seamed with alcoholic and sexual excesses and does the rest of you appear to be a grayish-pink lump, covered all over with brindle hair? Walking in the autumn woods do you feel that a subtle distance has come between you and the smell of wood smoke? Have you drafted your obituary? Are you easily winded? Do you wear a girdle? Is your sense of smell fading, is your interest in gardening waning, is your fear of heights increasing, and are your sexual drives as ravening and intense as ever and does your wife look more and more to you like a stranger with sunken cheeks who has wandered into your bedroom by mistake? If this or any of this is true you need Elixircol, the true juice of youth. The small economy size (business with the bottle) costs seventy-five dollars and the giant family bottle comes at two hundred and fifty. It's a lot of scratch, God knows, but these are inflationary times and who can put a price on youth? If you don't have the cash borrow it from your neighborhood loan shark or hold up a local bank. The odds are three to one that with a ten-cent water pistol and a slip of paper you can shake ten thousand out of any fainthearted teller. Everybody's doing it. (Music up and out.) I sent this in to MacPherson via Ralphie, the messenger boy, and took the 4:16 home, traveling through a landscape of utter desolation."

So the rest of this story is Moses arguing with the local politicians because zoning laws mean that no one can operate a funeral home near him, or even pick up a body and if he really wants anything done, he's going to have to put the body in a car and drive it over a municipality.

The story doesn't so much ramp up as get sillier. His ad writing becomes even more smartass and his fights with the municipality become even more frustrating. But then it just ends. He manages to convince the mayor to write an exception at the threat of just burying Justina in his backyard.

And his final ad copy is The Lord is my Shepherd.

So what are we talking about here? The story is supremely silly with a dead body, a smartass ad man (totally appreciated as someone who used to write ad copy when I was trying ot be a web designer) and John Cheever imagining a character who actually quits drinking. It's one of his lighter ones but it is also one where he is getting weird. Granted, Cheever is always much weirder than your average 20th century white dude writer talking about infidelity. But 1950s Cheever was weird in characters getting extreme at weird moments, like an elevator operator guilting all of the residents into giving him food for Xmas or a dude assuming that his old friend is a black widow who is out to kill him just because she has really bad taste in men.

So here we are with Cheever using a dead body for comedy.

#1960s#John Cheever#The Stories of John Cheever#Tim Lieder#corpose#corpse#funny death#funny corpse#weird#surrealism#20th century#suburbia#advertising#mad men#ida blankenship#the lord is my shepherd#psalms#smartass ad copy#ad copy#local politics#zoning laws#body in the backyard

1 note

·

View note

Video

1950 illustration by Edwin Georgi by totallymystified Via Flickr: For the story The Opportunity by John Cheever. From Good Housekeeping.

#Edwin Georgi#artist#illustrator#illustration#actress#stage#theatre#John Cheever#author#writer#story#fiction#retro#vintage#nostalgia#1950s#fifties#Good Housekeeping#magazine#flickr

4 notes

·

View notes

Note

8 for spot ify

Lemonworld by The National!

#thank you for sending!!#this is my sister’s favorite song by The National#Lemonworld and their other song ‘Humiliation’ remind me of John Cheever’s short story ‘The Swimmer’#maddi answers stuff

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

I say I’m ok but deep inside I’m still pondering the mental health implications of American writer John Cheever’s work—The Swimmer—from my last semester of college English

#John Cheever#the swimmer#literature#books#bookworm#classic literature#Cheever#the swimmer short story#bipolar disorder#bipolar literature#manic depression#manic depressive disorder#mental health

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

REUNION Written by John Cheever The last time I saw my father was in Grand Central Station. I was going from my grandmother’s in the Adirondacks to a cottage on the Cape that my mother had rented, and I wrote my father that I would be in New York between trains for an hour and a half, and asked if we could have lunch together. His secretary wrote to say that he would meet me at the information booth at noon, and at twelve o’ clock sharp I saw him coming through the crowd. He was a stranger to me -- my mother divorced him three years ago and I hadn’t been with him since-- but as soon as I saw him I felt that he was my father, my flesh and blood, my future and my doom. I knew that when I was grown I would be something like him; I would have to plan my campaigns within his limitations. He was a big, good-looking man, and I was terribly happy to see him again. He struck me on the back and shook my hand. "Hi, Charlie," he said, "Hi, boy. I’d like to take you up to my club, but it’s in the Sixties, and if you have to catch an early train I guess we’d better get something to eat around here." He put his arm around me, and I smelled my father the way my mother sniffs a rose. It was a rich compound of whiskey and after shave lotion, shoe polish, woolens, and the rankness of a mature male. I hoped that someone would see us together. I wished that we could be photographed. I wanted some record of our having been together.

We went out of the station and up a side street to a restaurant. It was still early, and the place was empty. The bartender was quarreling with a delivery boy, and there was one very old waiter in a red coat down by the kitchen floor. We sat down and my father hailed the waiter in a loud voice. "Kellner!" he shouted. "Garcon! Cameriere! You!" His boisterousness in the empty restaurant seemed out of place. "Could we have a little service here?" he shouted.“Chop-chop.”Then he clapped his hands. This caught the waiter’s attention, and he shuffled over to our table. "Were you clapping your hands at me?" he asked. "Calm down, calm down, Sommelier," my father said. "If it isn’t too much to ask of you, if it wouldn’t be too much above and beyond the call of duty, we would like a couple of Beefeater Gibsons." "I don’t like to be clapped at," the waiter said. "I should have brought my whistle," my father said. "I have a whistle that is audible only to the ears of old waiters. Now, take out your little pad and your little pencil and see if you can get this straight: two Beefeater Gibsons. Repeat after me: two Beefeater Gibsons." "I think you’d better go somewhere else," the waiter said quietly. "That," said my father, "is one of the most brilliant suggestions I have ever heard. C’mon, Charlie, let’s get the hell out of here." I followed my father out of that restaurant and into another. He was not so boisterous this time. Our drinks came, and he cross questioned me about the baseball season. He then struck the edge of his empty glass with his knife and began shouting again. "Garcon! Kellner! Cameriere! You! Could we trouble you to bring us two more of the same?" "How old is the boy?"

"That is none of your God damned business." "I’m sorry, sir," the waiter said, "but I won’t serve the boy another drink." "Well, I have some news for you," my father said. "I have some very interesting news for you. This doesn’t happen to be the only restaurant in New York. They’ve opened another on the corner. C’mon, Charlie." He paid the bill, and I followed him out of that restaurant into another. Here the waiters wore pink jackets like hunting coats, and there was a lot of horse tack on the walls. We sat down, and my father began to shout again. "Master of the hounds! Tallyhoo and all that sort of thing. We’d like a little something in the way of a stirrup cup. Namely, two Bibson Geefeaters." "Two Bibson Geefeaters?" the waiter asked, smiling. "You know damned well what I want," my father said angrily. "I want two Beefeater Gibsons, and make it snappy. Things have changed in jolly old England. So my friend the duke tells me. Let’s see what England can produce in the way of a cocktail." "This isn’t England," the waiter said. "Don’t argue with me," my father said. "Just do as you’re told." "I just thought you might like to know where you are," the waiter said. "If there is one thing I cannot tolerate," my father said, "it is an impudent domestic. C’mon, Charlie." The fourth place we went to was Italian. "Per favore, possiamo avere due cocktail americani. Subito." The waiter left us and spoke with the captain, who came over to our table and said,"I’m sorry, sir, but this table is reserved." "All right," my father said. "Get us another table." "All the tables are reserved," the captain said. "I get it," my father said. "You don’t desire our patronage. Is that it? Well, the hell with you. Vada all’ inferno. Let’s go, Charlie." "I have to get my train," I said. "I’m sorry, sonny," my father said. "I’m terribly sorry." He put his arm around me and pressed me against him. "I’ll walk you back to the station. If there had only been time to go upto my club." "That’s all right, Daddy," I said. "I’ll get you a paper," he said. "I’ll get you a paper to read on the train." Then he went up to a newsstand and said, "Kind sir, will you be good enough to favor me with one of your God damned, no good, ten cent afternoon papers?" The clerk turned away from him and stared at a magazine cover. "Is it asking too much, kind sir," my father said, "is it asking too much for you to sell me one of your disgusting specimens of yellow journalism?" "I have to go, Daddy," I said. "It’s late." "Now, just wait a second, sonny," he said. "Just wait a second. I want to get a rise out of this chap." "Goodbye, Daddy," I said, and I went down the stairs and got my train, and that was the last time I saw my father.

0 notes

Text

Ze deep joy we take een le company of people weeth whom we have just recently fallen in love is undeesguisable.

Pepe le Pew

0 notes

Text

week twelve - england and the us

Here's the last week! I really did have a lot of fun with all of these stories, no matter if I personally enjoyed them or not. I have a lot more authors to look into (as if my tbr wasn't long enough) and it was just nice to read some short stories instead of longer pieces for these last few months.

For week twelve I read: Russell Banks' "The Child Screams and Looks Back at You" John Cheever's "The Country Husband" William Gass' "Order of Insects" Ian McEwan's "First Love, Last Rights"

To be completely honest, I still have a very thin understanding of the theme for this week. However, after writing everything down, I think we're ending this last week with one of the most potent human emotions: shame. Whether this shame is in yourself, your relationships, or the life you've decided to live, shame is a powerful motivator to lie, hide, and deceive. It can easily break a person down into the smallest parts of themselves to which there is no putting them back together.

Known for his themes on personal relationships, Russell Banks' "The Child Screams and Looks Back at You" makes use of a jumping nature in the narration to bring a creeping sense of dread to the reader. Once you learn of the illness that had befell one of the narrator's children, you already know that it's far too late to save him. The mother is ashamed of her behavior, the sons ashamed of their father, the doctor ashamed that he put making the family feel better over the actual health and well-being of the child he was called to help. No, instead the doctor hits on the mother and when her son gets worse in the night, she is too ashamed of accepting the doctor's advances that she doesn't call him to come back. Her shame follows her in her dreams, in her waking moments: she had taught her sons how to forgive and while the rest of her children had forgiven her, she'll never get that from the her now dead son. How do you cope with that shame? For the mother, it appears that there is no miracle waiting to absolve her, just the cold silence of a child who she can never apologize to.

John Cheever's "The Country Husband" takes this idea of shame a step further. Considered a master at uncovering the duality of the human experience, the narrator of "The Country Husband" weaves through both the love and shame of his uninteresting, suburban life. He has a near-death experience, almost begins an affair with his babysitter, and ruins a young man's reputation just because Francis didn't like him - and yet what sets off his wife is that he was rude to one of their neighbors and almost damaged their social standing in the neighborhood. All of this is enough to drive him crazy and it does, too, just enough that he goes to a psychiatrist in tears. Conforming to this life, and then straying away from it, is killing him with shame. He can't be honest with anyone; not with something as big as his time in WWII or as small as telling a neighbor that he doesn't care about her curtains. He's in love with more exciting things, but can't go after them without shaming himself or his family. He's stuck and that, too, is shameful.

Out of all the stories this week, "Order of Insects" by William Gass confused me the most. Gass is the author of many a depressing story, which at first made his penmanship of "Order of Insects" confusing until you look into the obsession the narrator has developed over the course of the story. She's deeply ashamed of herself for finding common ground in the dead insects she finds around the house. She keeps saying over and over again that she is a woman, and a housewife at that. She is suppose to be afraid of these bugs, to sweep them up in horror of them, but she's not. Eventually, she finds them even beautiful, and keeps some like how some people pin butterflies. It's almost existential to read as she almost seems to be losing her mind over this connection she has made with the beetles she finds. She cannot have any duality, she can only ever be one thing and that thing is a housewife, a mother, a woman. She's not suppose to be anything else, to want anything else. She keeps looking at the insects just a bit too long before vacuuming them away.

The last story is "First Love, Last Rites" by Ian McEwan - yes, that Ian McEwan, though I must say I was sorely unimpressed. Was there merit to this story? Of course! It's a good story. It's also terribly boring; things can contain multitudes. At first glance, this is just the story of young lovers together over the summer, both trying to make money before they have to become anything important. What makes this story interesting in the small scratches behind the walls of the building they're staying in. At first the noise is easy to write off, especially when they're usually busy having sex to notice the sound. The scratching gets louder and louder, mimicking the rising heat of the summer and the lovers' slow descent into lethargy, until out bursts a rat to everyone's horror. While the rat is quickly killed, it is an obvious mirror to the two of them; they quickly find out that the rat was pregnant and that the unborn pups will soon die with their mother. The circle of life stopped in its tracks. There's a give and take here, though, as the ending might imply that the young girl is pregnant herself (though they had been careful, well, as careful as two teenagers can be, previously to make sure such a thing wouldn't happen). Humanity is full of these gives-and-takes, the shame of being too young and too old, the beauty of both as well. This was their last summer before they must go off into the world, becoming rats scratching at the wall to let them in.

I have to say, not exactly what I was expecting to be the last stories we'd be reading! I don't know why I was prepared for something happier when most of these short stories weren't, ya know, exactly made of fluff. This week was especially weird, though, just because of how vague some of the writing was this week. Though shame is, as I said, a potent emotion, I've never really had to feel much shame in my life, so perhaps I can not as well equipped to connect with the theme of this week. Whatever it is, it sure was an interesting time!

#russell banks#john cheever#william gass#ian mcewan#english literature#short stories#ENGL 4430#miistical murmurs

0 notes

Text

Book Editions

These are my posts featuring pictures of some novels' specific editions. This list will be updated continuously.

Oscar Wilde’s The Picture of Dorian Gray (first novel edition, 1891)

E. F. Benson's Bensoniana (first edition, 1912)

E. F. Benson's David Blaize & David of King's (1920s dust jackets)

Petronius’ Satyricon (Norman Lindsay's illustrations, 1922)

E. F. Benson's Colin (first American edition, 1923)

Doc Savage novels (Walter M. Baumhofer's covers)

Evelyn Waugh’s Brideshead Revisited (first edition, 1945)

Marguerite Yourcenar’s Memoirs of Hadrian (first edition, 1951)

Mary Renault’s The Charioteer (first edition, 1953)

Mary Renault’s The Charioteer (English-language covers)

Michael Scarrott's Ambassador of Loss (first edition, 1955)

Mary Renault’s The Last of the Wine (first edition, 1956)

John Cheever’s The Wapshot Chronicle (first edition, 1957)

Christopher Isherwood’s A Single Man (first British edition, 1964)

Gordon Merrick's novels (Victor Gadino's covers)

John Cheever's The Stories of John Cheever (first edition, 1978)

Ensan Case's Wingmen (covers)

Ensan Case's Wingmen & Beach Head (first editions, 1979/1983)

E. F. Benson's novels (Millivres' covers, 1990s)

Related: Gay literature posts

18 notes

·

View notes

Note

I think we have brush that subject once when rwrb came out. From my casual film watching i came to understand that when a book is adapted into a movie that the director actually purchased the right from the author(i might be completely wrong). Every single time a movie is made from a book it bring the question how true does the director have to stay from the book? Do they just get the overall topic of the book and go from there? How do they choose what to cut Nd keep from the book? Films are such a complex topics to me

I think with the baldoni/lively things also comes from the fact that he wants to shine the light on DV while she wants to makes it look like a woman empowerment movement which people are saying can take away from the real issues discussed in the book.

Thanks @5813 for giving me the opportunity to talk about adaptation. I remember some of the talks that took place about this when RWRB came out and I think my position was that we should be able to look at the film as a work of its own, hence my criticism of it shouldn't automatically offend the fans of the book that it had been adapted from.

I'll try to keep this brief and not turn it into a lesson. My knowledge is only slightly refreshed anyway as I've briefly looked through the notes I had on adaption from many years ago. They're mostly a summary of the major theories regarding the topic.

But first of all, let's establish what is an adaption? It's the transfer of a work of art into another medium, different from the one in which it was originally created: from literature to film, literature to music, theater plays to film, a painting into a film/theater play, etc. Adaption is not only a product, but also a process. I find the latter a more interesting frame to analyze and understand a work, beyond judgement of values of whether it is a good adaption or not.

Adaption also has an original text as a source which often is seen as having authority over the end result of the adaption. This leads to the principle of fidelity and one that is still considered as the most relevant and important to this day in certain circles, despite the huge amount of scholarly research that has brought forth the numerous ways in which what can be determined as a good adaption doesn't need to be only the one that fully respects the original source.

Going back to the principle of fidelity, you'll find its definition familiar, because it is the main discourse. In this case, an adaptation has to not only capture the artistic and ideological features, but also to reproduce the contents and the structure of the story. A lot of the times, the more an adapted work is as close as possible to the original text, the better it is considered to be (Think of the BBC adaptions of the works of Jane Austen). That is because from that perspective, the original text (often time coming from literature) is considered superior while the second medium will never be able to fully capture the complexity of the book. Hence, for those who use this argument, the cinema and the process of adaptation it engages with is not seen as its own separate art form, with its own grammar through which the transformation of a story can take a new life and create a separate work of art that can stand on its own and be just as valuable.

In contrast, I want to offer some other examples of type of adaptation just so you can get an idea.

Homage adaption – a re-adaption of a former adaption. For example, Gus van Sant's Psycho is an homage to Hitchcock's Psycho which in turn was a story adapted from a book.

There's the adaptation that focuses on romanticizing a past, without investigating it, the focus is on nostalgia – The Great Gatsby from 1974.

An adaptation can be compressed (a 500 page book needs to become a 2-hour movie, there will definitely be cuts) or extended (a short story like John Cheever's The Swimmer had to be extended with other scenes added to it in order to turn it into into a 1h30min film. (extension also applies to films based on music albums)

A favorite of mine is the process through which a text is transformed in order to reflect the ideology of the present, hence also showing its thematic universality. A famous example of this is 10 Things I Hate About You which is an adaption of Shakespeare's The Taming of the Shrew. The action takes place in the present, all the stylistical elements are contemporary, the dialogue is changed as well, but the essence and the skeleton of the story remains the same.

There's more to this and also grouped based on various schools of thought, but for the purpose of your ask, I think I've answered your question a little bit.

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

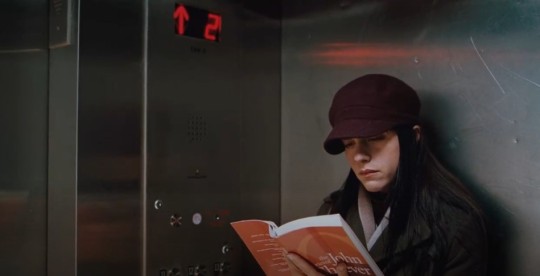

The Uncollected Stories of Mavis Gallant (Book acquired, 2 Jan. 2025)

The Uncollected Stories of Mavis Gallant publishes later this month from NYRB. And oof is she a big boy! NYRB’s blurb: Mavis Gallant’s extraordinary mastery of the short story remains insufficiently recognized. She may be the best writer of stories since the early-1950s prime of John Cheever, Eudora Welty, and Flannery O’Connor, and even in such august company, her work is sui generis. Gallant’s…

View On WordPress

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Stories of John Cheever

Rescue Me: "Harmony"

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Three Stories" (The Stories of John Cheever)

There's a fine line between clever and stupid.

So these are barely stories. More like sketches. And in almost all of them you feel like Cheever is going "aren't I cute?" Two of the stories are "clever" in a way that just feels cloying while the middle story is mysterious in a way that can be intriguing or irritating depending on your bias.

I. The first story is told from the perspective of a stomach. It's basically a fat guy talking to himself. Only, it's the stomach trying to push its agenda. The stomach is happy to have grown but then went through an irritating time when the man try to get it to shrink.

Basically, you get older and you get fat and unless you want to be obsessive and insane about your weight loss, you might as well just give up and let your waist size get bigger. Sure, you have to buy new pants, but do you really want to NOT eat all the good food?

II. This one is mysterious since it's about a woman who is married to a man who dies in a car accident. A few years later, she marries another man who ALSO dies in a car accident. There's a great deal of scenes where the town is trying to expand the highway and then trying to save a woman's home.

And people keep dying on the highway. Only someone is shooting the truckers. So is it the woman? Or is it someone else? The woman seems to be pretty blase about the fact that she keeps getting married to guys who die on that highway, but there was no talk about bullets in the first couple of accidents. Either way, she moves away and gets married again and....I don't know?

III. This one has a twist ending. You think that it's going one place but it's going another place. From the beginning you think it's about an irritating guy who is trying to flirt with a woman who isn't interested. Like she's really not interested. Seriously dude, shut up.

He asks her what she's reading and she won't say. He's telling her pleasant dreams when she falls asleep but she rolls her eyes. Everything he says is a source of annoyance and yet he won't stop.

Twist ending - they are married. So what looks like a creepy dude trying to hit on a woman is actually a husband trying to talk to his wife. Only his wife is treating him like a stranger who won't shut up.

The twist would be more interesting if this wasn't another story in an endless series of stories about husbands and wives who hate each other. Like the entirety of 20th century marriage humor seemed to be "fuck my wife" (or take my wife...please) and there's a reason why fans felt so betrayed when John Mulaney left his wife. He wrote a lot of jokes about how much he loved her and was crazy about her so it was refreshing not to have the standard borscht belt jokes about shrew wives.

So here, our sympathy is to the woman who has to put up with this guy until Cheever outright tells us that she married him. Then we are supposed to think that she's a shrew and he's just a sad sack. Whatever.

#John Cheever#Stupid#3 tales#3 stories#guts#stomahc#murder#highway murder#sharpshooter#pickup#failed pick up#marriage is evil#Tim Lieder#bad romance#widows

0 notes

Text

THE END OF AN AFFAIR?

I think my life-long love affair with books is over. I’m not quite sure why. But I know that I no longer enjoy reading the way I once did. It takes me far longer to finish what I’m reading than it ever has. Writers I’ve read and enjoyed for years have begun to aggravate me. Instead of looking at my books with desire in my eyes, I view them with contempt. Instead of dreaming of having bookshelves filled with books throughout the house, I want what remains of my collection gone completely, and I look at my bookshelves now, and think, “Hmm…I wonder what else I could do with that space?” More than once this year I came very close to packing them all up in a box, and dropping them off at Goodwill.

Since I retired in 2020, I’ve read 307 books. When I retired, I had more than 700 unread books on my shelves, and I had a plan to have them all read by 2028. But when our landlords suddenly sold the house we’d rented for 25 years out from under us without warning, I was forced to downsize. I got rid of something in the neighborhood of 70% of what I had, cherry picking what I believed to be the best – books I absolutely had to read. I’ve bought a few since we moved, and I’ve read 100 of the books I had left since May of 2022 – with increasingly disappointing results.

Unlike most people I’ve met who read, I like a far wider variety of things. I like books related to music, biographies, history, genre fiction (mysteries, horror, science fiction, espionage), as well as science, sports, poetry, pop culture, sociology, short stories, plays, essays, and letters. I’m someone who has often spent more than a couple of hours browsing a well-stocked bookstore. But with the sudden devaluation of used books (where instead of offering you a paltry 50 cents or a dollar for a good title in mint condition, they tell you they can’t pay you for them, but if you just want to get rid of them they can send them to be recycled), I no longer have any reason to visit used bookstores, and there are now only two “new” bookstores where I live – neither of them close by, and I haven’t visited either in the past several months, and doubt I’ll go out of my way to ever visit them again. I used to visit the local book fair annually as well. But I no longer do that either.

The only thing keeping me from dumping the lot of them is that I spent money on them, and I’d like to get some value out of them. Since no one wants to buy them – even on the cheap - the only value I can get from them is to read them. So, I tell myself that I’ve just had a run of bad luck, and that what’s left on the shelves will be better than what I’ve read the past couple of years. A look at my annual lists of books read reveals the kinds of books I’ve always read, along with many name authors I’ve enjoyed for years, and though it’s all there, I can count on one hand the number of truly great books I’ve read the last couple of years. The list of books that were so bad that I wished I’d never read them far exceeds that. Everything else falls into the category of “just okay” or “not bad” or “somewhat disappointing.” So, I can’t help thinking I’m at the end of the road, and maybe it’s time to pull the plug.

What I do know is that the more you read almost any single author, the more likely it is that you will wind up hitting a wall, and swearing off ever reading them again. That’s happened to me with Anne Rice, John Cheever, Jack Kerouac, J.K. Rowling, Graham Greene, Kurt Vonnegut, Pete Hamill, and a few others. I still have books on my shelf by John Updike, Philip Roth, and Norman Mailer, but I’m not certain how much I want to read them – even though most of them were well-reviewed, and some critically acclaimed. That’s why they’re in my collection to begin with. I did my homework. I researched writers, ferreted out their best works, read books that are considered to be quite good, even classics, or masterpieces. They are, at the very least, highly regarded by those who are supposed to know. But much of it is disappointing.

Writers all seem to have an agenda. All of them are obsessed with some theme or a particular point of view. Their works may seem diverse, but you begin to realize they’re making the same point, but in a different way.

Writers also have annoying habits related to their style that I find myself increasingly unable to tolerate. For example, I can’t stand a writer that isn’t reader friendly. What I mean by that is a writer who thinks nothing of writing a single paragraph that stretches on for two or three pages. I don’t like writers who will use ten words when a single right word will do just fine. I don’t like writers who meticulously, and thoroughly research a subject, and then insist on using every last bit of it in the book rather than using only what’s relevant. I can’t count the number of non- fiction books I’ve read that have been ruined because the author refuses to edit himself, turning a great 400-page book, for example, into an unreadable 600-page doorstop. I don’t like the liberal use of words or phrases in a foreign language with no English translation. I’m not going to stop in the middle of a paragraph, and ask Google to translate a word or phrase from a book I’m reading in English. There’s a John Updike book called Memories of the Ford Administration where he does that throughout the book – sometimes whole paragraphs appear in French with no translation – not even a footnote! I’m not an advocate of book burning, but when I finished reading it I wanted to set it on fire. And I took two years of French in school, but not enough to navigate the volume of it in this book. It was simply unnecessary. But if you insist on doing it, at least put a translation in the footnotes. As a result, I’m wary of ever reading another Updike book again. (He also writes terrible dialogue, but that’s another issue.) And I can’t even write him a nasty letter complaining about it because the s.o.b. died a few years ago. Even an author I won’t mention who self publishes his own stuff, publishes in a wide page, soft cover format that is not in any way user friendly. The wider the page, the more the reader has to work to not lose his place. Not to mention the questionable practice of doing a wide page soft cover book of 500 pages that weighs more than my dachshund. Don’t make me work to read your book. If I didn’t enjoy his writing, I’d never read him again.

I had to read a few of Norman Mailer’s books to realize that every one of his books (fiction, non-fiction or journalism) is about Norman Mailer. All of the Kurt Vonnegut books I’ve read seem to carry the same theme: WAR IS BAD! Okay. I agree, but what else ya got? James Ellroy writes very violent crime novels, but in far too many of them, one or more characters are decapitated! Really James? How often does that happen in real life? If On the Road hadn’t been a classic, Jack Kerouac would’ve struggled to get a contract to write another book. Every Philip Roth book I’ve ever read is about the trials and tribulations of being Jewish.

But it’s not a case of reading the same authors every year, again and again, and just growing weary of them. I read a dozen books this year by authors whose books I’ve never read. But I cannot seem to find new authors who are worth reading that can actually write, and have something to say that I want to read.

My wife reads a great deal, and she constantly finds new authors she likes, and they recommend authors they like, and so she’s able to keep everything fresh. Her tastes aren’t as diverse as mine, but her batting average as to what she likes is far higher than mine. I envy her success, and her luck. But I can’t even branch out and simply read something different because I already read books that are shelved all over the bookstore. So, it seems I’ve reached an impasse.

I’m considering simply taking 2025 off from reading any narrative books at all, and just reading magazines or anthologies of short stories or essays. If you don’t like what you’re reading there, you can quickly finish and move on to something else. But I’m sure every time I walk into the closet, I’ll hear my books whispering to me, “Pick me! Read me now!” And after a month or two of no additional free space in my closet, I’ll throw in the towel, and start again.

I know, I know. This is a first world problem. In some countries people can’t read at all. It’s just that most everything I once enjoyed doing has fallen by the wayside already. Now it’s happening with books, too? Jeez! The asteroid can’t come soon enough. (And as I was finishing this piece, a podcast tipped me to a new music book that I think would be a great read. Damned internet!)

2 notes

·

View notes

Note

What are your most and least favorite pieces of literature?

Favourite Novel: Notre-Dame de Paris (Victor Hugo), As We Are Now (May Sarton)

Favourite Novella: The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde (Robert Louis Stevenson), The Dead (James Joyce)

Favourite Short Story: The Swimmer (John Cheever), A Clean, Well-Lighted Place (Ernest Hemingway)

Favourite Poem: Mending Wall (Robert Frost), Rime of the Ancient Mariner (Samuel Taylor Coleridge), Darkness (Byron), Goblin Market (Christina Rossetti), A Valediction: Forbidding Mourning (John Donne)

Favourite Play: Fortitude (Kurt Vonnegut)

Least Favourite Work in All of Literature: Miss Julie (August Strindberg)

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Burt Lancaster in The Swimmer (Frank Perry, 1968)

Cast: Burt Lancaster, Janet Langford, Janice Rule, Joan Rivers, Tony Bickley, Marge Champion, Kim Hunter, Bill Fiore, Rose Gregorio, Charles Drake, House Jameson, Nancy Cushman, Bernie Hamilton. Screenplay: Eleanor Perry, based on a short story by John Cheever. Cinematography: David L. Quaid. Art direction: Peter Dohanos. Film editing: Sidney Katz, Carl Lerner, Pat Somerset. Music: Marvin Hamlisch.

The Swimmer evokes that common anxiety dream in which you're naked or in your underwear in a familiar place like work or school. The people around you don't seem to notice, but you suspect that they're secretly laughing at you. The dream is produced, of course, by something that you don't want other people to know about you. Ned Merrill (Burt Lancaster) isn't naked, but he's exposed, wearing swim trunks and barefoot, when we first see him walking through the woods. He comes upon a group of his neighbors gathered around their swimming pool. They greet him heartily, commenting on how long it's been since they got together, serving drinks and making small talk. Ned suddenly has an idea: All of his neighbors have pools. Why couldn't he swim his way home, moving from pool to pool until he reaches his destination? The group cheers him on. Ned is an athletic middle-aged man (Lancaster was in his mid-50s when the film was made, but looked perhaps ten years younger), and the day is sunny and warm. But as he continues his pool-hopping, he injures himself slightly and the day gets darker and chillier, and so does the reception of the pool-owners he encounters. We begin to discover that Ned is in financial trouble and that the marriage he initially portrayed as happy has fallen apart. The John Cheever story on which the film is based is often read as a fable about suburban hypocrisy and male anxiety, and the movie supports those and other interpretations. Lancaster is perfect casting, not only because of his physical fitness but also because of the signs of aging that the camera inevitably reveals -- camera angles, for example, sometimes show the thinning of the hair at the crown of his head. But the film version lacks the Everyman quality of Cheever's story, missing some of the shock of recognition by the reader, an inevitability in its translation to a visual medium. It also ran into some trouble with producer Sam Spiegel, who had many scenes recast and reshot, firing director Frank Perry and replacing him with Sydney Pollack. It was not a success at the box office, being a little too oblique for audiences and some critics, but it has gained stature with time.

5 notes

·

View notes