#the royal heir texas

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

While I'm at it, I want to precise something about the language of these 17th century fairytales like Perrault and d'Aulnoy.

There is something that might be confusing to foreigners not speaking French - that is confusing even to modern-day French folks unaware of the 17th century complexities - but that might be even more confusing for Americans and other people used to a very specific word... "Race".

Race pops up regularly in Perrault's and d'Aulnoy's fairytales, and I do not know how the word was translated in English, but the word "race" of these tales does NOT translate as modern day "race". Yes, race in the racist sense of today did exist by the 17th century... But it was a minor usage not very widespread nor common. What the French word "race" actually refers in these stories is... bloodline.

"Race" was for example used very regularly when princes or princesses speak of their family or ancestors. A princess' "race" means her royal house and royal ancestors. To "perpetuate the race" simply means "having an heir", as simple as that. It is by extension that "race" went from "a specific family or bloodline" to "a specific ethnicity or species". Think of the old house of "house". Like... House Lannister in Game of Thrones? In Perrault's text, it would have been written "the race of the Lannisters".

This is a point I myself came across when doing my paper about ogres, because when talking about the mother of the prince from Sleeping Beauty, Perrault specifies she is "de race ogresse". Today we can understand it as "she was an ogress" or "she was of the ogre species" and it does work since ogres are not human beings in popular culture... But Perrault's original text is much more subtle than that - because remember, in Perrault's fairytales ogres are ambiguously humans or half-humans - and what he actually meant was "she was of ogre bloodline".

By extension, and that was another point of my paper, it is a common part of ogre lore that ogres are always about family. This is why for example the mad clan of "Texas Chainsaw Massacre" is a good example of modern-day ogres: ogres always have a wife, sons, daughters, brothers or sisters somewhere. Perrault's ogres are a bloodline that seemingly mixes and mingles itself with nobility and royalty, and we have an ogre who has seven daughters ; madame d'Aulnoy presents us clans of ogres also with half a doen kids and who are focused on getting grandchildren. And this is even present in the uerco/orco lore of Basile's Pentamerone - for example in "The Golden Root" where the heroine has to fight or win the heart of an entire clan of ogres, mother, aunt, son and daughters (plus baby cousin thrown in a burning oven).

105 notes

·

View notes

Text

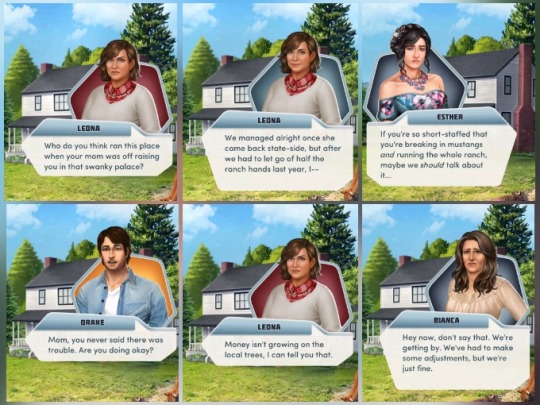

Leaping to Conclusions

Pairing: Liam x Riley

All characters belong to Pixelberry

Summary: The pressure to produce an heir is getting to Liam and Riley, leading them to turn to some unconventional methods.

Rating: PG, Adult Language

Word Count: 1,395

A/N: This fic is insanity guys, I'm not even going to pretend it's anything but. I learned the most absurd fun fact this week, and after sharing it with pretty much everyone I know, @ao719 convinced me that it needed to be a fic, and here we are.

For the record, this story doesn't take place in any of my timelines. My Liam and Riley can be weird, but never this weird. 😂

I am participating in @choicesflashfics, the prompt: “Wait a second. Pause and rewind … what did you just say?” will appear in bold below.

And finally, nobody has pre-read this, so apologies in advance for my horrendous grammar, and anything else about it that sucks.

Riley’s eyes fluttered open as she felt Liam’s lips trailing slowly across her shoulder. She moaned softly and arched back into him.

“Good morning, love.” He whispered huskily into her ear.

“When it starts like this it is.” She replied, reveling in the attention she was receiving from her husband.

As his hand traveled up her body, her stomach started to lurch. Her hand flew to her mouth and she leapt out of his arms and rushed to the bathroom of their guest room in the Walker ranch. Liam sat up and watched with worry as the door slammed shut.

After a few moments, Liam stood and approached the door. He could hear his wife on the other end, and he knew exactly what was going on. He rapped gently on the door. “Riley, are you alright? Can I get you anything?”

The only response he received were a few more retching noises, followed by the toilet flushing. Soon after, the door opened, and Liam met Riley’s red, blotchy eyes. “Sorry.”

Liam wrapped his arms around her, pulling her flush against him. “You don’t have to apologize, it’s not your fault.” They stood there in silence as Liam held her. “Riley, do you think you may need to take a test?”

Since the royal couple had gotten married, they’d been facing pressure to produce an heir. While they did not take their positions as monarchs lightly, for them, it was more about building a family together.

“It wouldn’t hurt.” Riley shrugged before returning to the bathroom, closing the door behind her. Liam took a seat at the end of the bed to wait for her.

“Oh no!” Liam stood and rushed back to the door at Riley’s cry. She came back into the bedroom, more distraught than she had been before. “I dropped the test in the toilet.” She buried her head in her hands.

Liam chuckled slightly, as he wrapped his arm around her. He had read that pregnancy hormones could cause overreactions; he assumed, hoped, that was why she was so upset. “It’s alright, just take another one.”

“Liam, it was the last one!” She snapped.

He stepped back, shocked by her aggression. “That’s alright, we can go into town and get more.”

“Are you kidding?!” Riley threw her hands up in frustration before moving to the bed and dropping down, burying her face in the pillow. “The press has been all over us, the last thing I need is for them to get a picture of me buying pregnancy tests!”

Liam sat beside her on the bed, rubbing her back gently as he racked his brain for a solution. “I’ve got it!”

Riley rolled over and sat up, leaning against the headboard. “What?”

“We’re in Texas, surely there is a frog around here somewhere.” He said as he moved to the dresser, pulling out a pair of jeans.

“Liam, this is no time to go wildlife gazing, I might be carrying the heir!” Riley chided him.

“Love calm down, the frog will be able to tell us.” He said matter of factly as he continued to get dressed.

Her face contorted into a confused expression. “Wait a second. Pause and rewind … what did you just say?”

He sat beside her on the bed and slid on his boots. “For about twenty years, starting in the nineteen forties, before the pregnancy tests we are familiar with today, there was the Hogben test. A British zoologist, Lancelot Hogben, discovered that when urine samples from pregnant women were injected into frogs, the frog would spawn eggs within eighteen hours. It was the most rapid and reliable pregnancy test of the time.”

Riley stared at her husband in stunned silence. “How the fuck do you even know that?”

“I like history.” He shrugged.

Still befuddled by her husband’s solution, Riley took a deep breath. “So you want to inject a frog with my pee, and then in 18 hours either nothing happens and I’m not pregnant, or I am pregnant and we also have a hundred and seventy two frog eggs?”

“They’re called frogspawn, love.” He corrected.

She slapped her palm against her forehead. “Yeah, because that’s the most crucial thing in this conversation.”

“I’m sorry, force of habit,” Liam smiled sheepishly. “Would you like to try it? It’s a fascinating concept, I would be interested to see it in action.”

“Liam, I don’t even want to touch a frog, let alone do science experiments on it.”

“I’ll take care of everything,” he insisted. “I’ll just need your… well, your um… sample.”

Riley chuckled when Liam started to get flustered. “Alright, if it’ll make you happy, and all I have to do is pee in a cup, then let’s give it a try.”

Liam grinned and leaned in, planting a quick kiss on Riley’s lips. “Excellent!”

“I guess Kermit was right, it’s not easy being green.” Riley said, shaking her head.

Liam made his way to a nearby pond in search of the perfect frog. His eyes roamed the banks in search of his test subject. “If I were a frog, where would I be?”

Finally, he noticed a slight movement out of the corner of his eye and turned to see a frog seated on a nearby rock. “Perfect.” He stalked toward his prey, making sure to stay as quiet as possible.

Liam was so laser focused that he didn’t notice Drake coming up behind him, curiously observing the actions of his best friend. “Li, what the fuck are you doing?”

Drake’s words startled Liam and before he had time to catch himself, he tumbled over into the pond as the frog lept away. Drake cackled as the King of Cordonia sat waist deep in the pond glaring at him.

“Sorry,” Drake apologized as he reached down, helping Liam out of the water. “But seriously, what are you doing?”

“Riley might be pregnant,” he answered.

Drake furrowed his brow, even more confused now that he had the explanation. “Okay, so you decided to go frog hunting to celebrate?”

“No, we lost the test,” he responded. When Drake continued to stare at him with a blank expression, Liam sighed and explained the Hogben test just as he had done for Riley earlier.

“And Brooks agreed to go along with this?” Drake chuckled.

“We would do anything for eachother.”

Drake rolled his eyes and moved toward the pond. A few moments later he returned with a frog.

“How did you do that?” Liam marveled.

“You had your training growing up, I had mine.” He shrugged in reply.

Liam took the frog from Drake, thanking him for his efforts and began walking back to the house.

“I’ve gotta see this.” Drake said to himself as he followed Liam.

Liam entered the house heading toward the stairs, until he saw Riley sitting with Madeleine on the living room couch. When he stepped up to them, he noticed the crestfallen expression on his wife’s face.

“Love, what’s wrong?”

“I’m not pregnant,” she responded, her eyes trained on the floor.

“But how do you know? I’ve got the frog right here.” He held it up to show her.

Madeleine stood from the couch, glaring in confusion and disgust at the sight in front of her. “When I was in town this morning, I bought some tests. I figured you would need them.”

“Oh Riley,” Liam moved to Riley, outstretching his arms.

“Liam,” she held a hand up to stop him from getting any closer. “You’re slimy, and wet… and holding a frog.”

“Oh, right.” Liam looked down at himself, and the frog in his hands. “I should shower. Care to join me?” He asked slyly.

“Um… maybe you should handle this one solo,” she cringed.

Liam handed the frog over to Madeleine, who grabbed it instinctively. He signaled for Riley to follow him, and they made their way up the stairs to the bedroom.

“So you’re not going to pee on a frog?” Drake called out as they exited the room.

“Ugh,” Madeleine groaned. “None of this would be happening if I were queen.” She turned to Drake, thrusting the frog in his direction. “Make yourself useful and deal with this thing.” She stormed out of the room, mumbling to herself, questioning where things went wrong for her.

Drake looked down at the frog with a grin. “God I love Texas.”

Permatag:

@3pawandme @alj4890 @busywoman @charlotteg234 @cordonia-gothqueen @cordoniaqueensworld @differenttyphoonwerewolf @emkay512 @foreverethereal123 @hopelessromanticmonie @iaminlovewithtrr @imashybish @kat-tia801 @kingliam2019 @malblk21 @mom2000aggie @neotericthemis @nestledonthaveone @queen-arabella-of-cordonia @secretaryunpaid @sincerelyella @theroyalheirshadowhunter @tessa-liam @twinkleallnight @txemrn

Liam:

@amandablink @custaroonie @jared2612

TRR:

@21-wishes @ao719 @belencha77 @burnsoslow @lovingchoices14 @the0afnan

@choicesficwriterscreations @choicesflashfics

#the royal romance#trr#choices#choices trr#choices the royal romance#trh#the royal heir#choices the royal heir#play choices#choices stories you play#cfwc#cfwc fics of the week#king liam#liam rys#king liam rys#liam x mc#liam x riley#trr liam#trh liam#trr king liam#try king liam#trr riley#trh riley#trr riley brooks#trh riley brooks#trr fandom#trr fanfic#trr fanfiction#trr fan fiction#trr fan fic

151 notes

·

View notes

Text

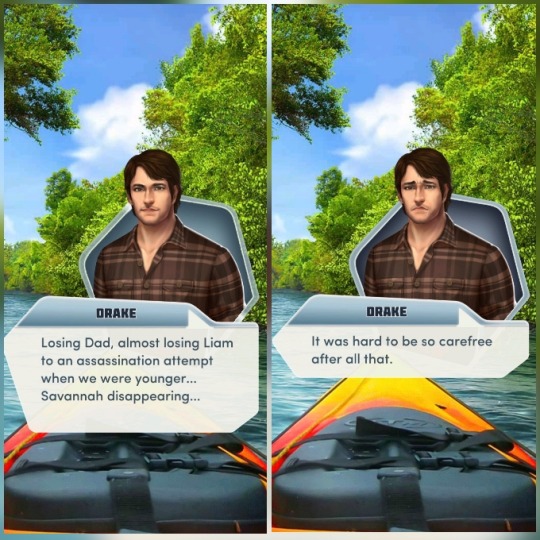

Victim of Love Chapter 15: Now and Forever

Series: Victim of Love

Fandom: The Royal Romance

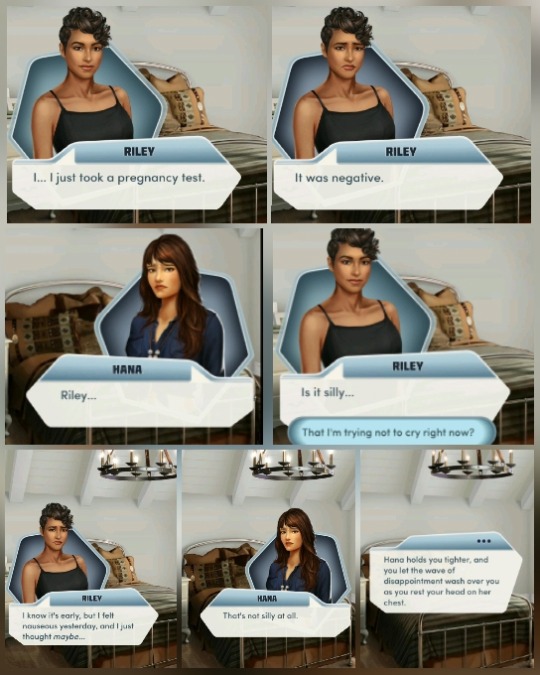

Pairings: Drake x Riley, Liam x Riley x Hana

Word Count: 1,555

Rating: MA

Warnings for this chapter: none

Song Inspiration for series: Victim of Love by The Eagles

You're just a victim of love I could wrong but I'm not no I'm not

A/N: Finally we come to the final chapter of this "one-shot" I wrote for World Whiskey Day.

My other stuff: Master List.

The press conference had been exhausting. Liam ushered his wife and child into their private quarters and closed the door with a relieved sigh. “Thank God that’s over,” he pulled at his tie as he made his way across the room, “Do you want me to take her?”

“No, I’ve got her. I think all the people made her fussy.”

It was tradition to present the new heir to the press at the age of three months. It had been Crown Princess Eleanor’s first public appearance ever. The public and the press corps oohed and ahhed appropriately, but it had been nerve-racking for the royal couple.

After the last several years of upheaval and his father’s death at the hands of terrorists, describing Liam as apprehensive about the whole thing would have been a gross understatement. He had quadrupled the normal guard detail for such an event, restricted attendance to less than a quarter of the typical amount and made all members of the press corps submit to background checks ahead of time.

He watched as his wife carried their daughter to the nursery for a nap with mixed emotions dancing through him. He couldn’t suppress the thought that it should have been Riley carrying his child through their home. It should have been her beside him on that dais. It should be her that was here with him now.

But it wasn’t and it never would be.

Hana was the mother of his child. Hana had stood beside him on that dais, and it was Hana that was here with him now. It would always be her by his side at official events. If there were to be another heir, it would be through her. He couldn’t find it in him to resent her for any of it. He had put her in this position, after all, and she had handled herself admirably through the last several months.

She had been restless on restricted activity in the months prior to Eleanor’s birth, but she had followed the doctor's orders to a T, determined to do what was best for their child, and had done an amazing job in the delivery room.

Hana was his wife. Hana was his queen.

But it was Riley who had calmed his nerves about the press conference, Riley who had reminded him of all the changes in the guard made under his watch, Riley who had convinced him to trust the men he had hired to do their jobs.

He had love and respect in his heart for his wife. But there was no doubt who he was in love with and they both knew it.

Riley and Drake had gotten married last month in a lavish ceremony at the ranch in Texas.

Liam had not been in attendance. Officially the reason given was that he could not be absent from Cordonia at that time due to both work and personal obligations. The public had accepted that without question as spending the first three months away from the public eye and social obligations was routine in Cordonian custom after the birth of a child.

The truth is, he had not been invited.

“I love you, Liam, I do. But our wedding day should be about me and Drake.”

She had been right, of course. He wasn’t sure he would have been capable of witnessing it.

There was a knock at the door and Liam hurried to answer it, a smile already spreading across his face. “Riley! Drake!”

He hugged Drake first then swept Riley into his arms with a delighted laugh.

Drake stepped aside as Liam spun her in a circle. He didn’t look back as Liam kissed her, crossing the room to help himself to the drink cart, “I think that went well.”

“It did,” Liam conceded, holding Riley’s hand as he crossed the room with her in tow. “Riley was right. I had nothing to worry about.”

“Of course, you didn’t,” she admonished, “I told you to trust your new King’s Guard Commander.”

Liam nodded as he addressed Drake, “I do like all the changes you’ve made. Things run smoother, there hasn’t been a single security breach since you’ve taken over and morale in the ranks has improved.”

“Well, I appreciate you giving me free rein and allowing me to take time off for the wedding right after I started.”

“Of course I did.” He would have given him anything he wanted to get him to relocate back to Cordonia, keeping Riley close to him.

The newly married couple would still visit the ranch often. Drake had hand-picked the new foreman and Bianca hadn’t put up much of a fuss about him leaving. She was too busy being ecstatic about their union. She might have said I told you so. She was already planning a trip to Cordonia to visit them at Valtoria.

Drake had just taken a seat only to immediately scramble to his feet as the queen entered the room.

“You didn’t have to get up,” Hana told him. She went first into Riley’s arms, hugging the other woman to her tightly, before turning and stepping into his embrace.

Riley had agreed to try and move her relationship with Liam forward only if Hana agreed to it. Hana had agreed to it, only if she and Riley worked on putting their relationship back together.

It was true that she had only married Liam to spite the woman who spurned her. It was true that her burning jealousy had never been over Liam, but over Riley.

“I just want a chance to put things right, if we can. I want my best friend back!”

“How’s my Goddaughter?” Riley asked as Drake resettled himself on the couch.

Hana seated herself next to Drake and snuggled under his lifted arm, “She wasn’t a fan of the press conference, but she’s sleeping away now.”

Though Hana was bisexual and liked Liam and found him physically attractive, she wasn’t in love with him. She was still in love with Riley. Once she and Riley had started rebuilding their relationship, her strained relationship with Liam began to improve as well. Mostly because she stopped resenting him as the thing that had come between them.

She was the one who had chosen to marry him, forcing herself to have a ringside seat for their continued love affair. It’s not like she hadn’t known they were in love with each other. Once she had accepted her role in the destruction of their friendship, things slowly started to improve between the three of them.

Not only had she gotten Riley back in her life and thawed her relationship with her husband, she had gained Drake as a friend as well. She snuggled closer and rested her head on his chest. If Riley could sleep with her husband, she could at least snuggle with hers. No one seemed to mind.

The four of them had become almost inseparable over the past few weeks as all the light and love trickled back into the two best friendships and the cracks healed between lovers and spouses.

Drake and Liam found new footing as they navigated loving the same woman. Liam and Riley fell back into the easy camaraderie interspersed with flares of passion that had characterized their relationship before it all went sideways. Liam and Hana were able to open up to each other now that all the cards were out on the table.

The roughest seas to sail had been the fractured bond between the two women. Both had been betrayed by the other, both had felt the sting of that betrayal.

Oddly enough, Drake had been instrumental in Hana’s healing process. Mostly by being a nonjudgmental ear. As she grew closer to Drake, Riley’s utter lack of resentment or jealousy of the friendship filled Hana with hope for the future. They could move forward together, all four of them. She wasn’t going to be left behind or left out ever again.

Drake ran his fingers distractedly through Hana’s hair as his eyes tracked Riley’s movements. She was seated next to Liam, her hand resting on his inner thigh. Liam’s gaze was locked on her face as ran his fingers up and down the exposed skin of her arm.

Drake lifted the tumbler of outrageously expensive scotch to his lips with his free hand, shaking his head in bemusement. If anyone had told him he’d end up in a committed relationship that was basically a foursome he would have laughed at them. But here they were.

Riley was romantically entwined with all of the other three members of their quad and Liam with both of the women. Drake was the only one involved with just one person, but as he and Hana drew closer, the what-ifs had been discussed and everyone had agreed that they were fine with whatever developed organically out of that.

Riley could do no less for Drake than he had done for her. He had opened up space in his heart for her while leaving her the freedom to love others. It was no small thing, and she was grateful for it, and for him. She loved him madly. Just like she loved Liam, and yes, Hana too.

They were truly one cohesive unit and more importantly, everyone involved was finally happy.

~Fin

#the royal romance#trr#the royal romance fanfic#drake walker#liam rys#trr au#trr poly#angelasscribbles#choices#choices fic writers creations#choices stories you play#cfwc fics of the week

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

Worthy

Author’s Notes

It is unversally accepted that a Spanish woman must be late to everything she proposes herself to do/participe, and I am no less lol. But better late than ever, right? This fic was so cute to make and I took inspo from @lorirwritesfanfic ‘s Niceness Test, though the context is a bit different, lol. Also, this is my entry for @hanaleeappreciationweek day four: relationships and home

Summary: Princess Stephanie’s investiture is close by the day, and while she questions her worth as heir, Hana is happy to remind her little blossom of her own worth as future queen.

Rating: G

Word Count: 2.6k

Pairing: Hana Lee x MC (Eclipsa Ice) Liam Rys x OC (mentioned)

Category: Family fluff

Book: The Royal Romance

May, 2038

“What if I mess up and they end up hating me?” Stephanie asked her godfather, the King, as he explained how the investiture of the Crown Princess would be like.

Liam blinked “Pardon?”

Stephanie sighed “What if I do something wrong and I plunge the country into chaos?”

Liam took her hand and squeezed it “You won’t, sweet blossom. If I’ve learned something from you these past eighteen years is how smart and strong you are. You got that from your mother.”

“Which one?”

Liam smiled “Both. You have Mama Hana’s iron will and Mummy Eclipsa’s fiery strength. You always have. Even as a baby, you were quite opinionated.” He joked.

Stephanie giggled “Was I?”

“Oh, yes. But it is a good thing. A ruler must first rule her own mind so they don’t become puppet kings or are driven by paranoia like…”

“Your father, King Constantine?”

Liam nodded, a nostalgic expression on his face. Stephanie bit her lip, feeling awful about having brought up such a topic. Especially with Dowager Queen Regina’s death so recent.

“Forgive me, I overstepped.”

Liam shook his head “Of course not. It is an elephant in the room that should be addressed from time to time.”

Stephanie thought of something to say, but her Mommy Eclipsa’s imposing figure stepped into the room, accompanied by her Mama Hana and her brother Marcus. Marcus bowed with a smile, and Hana embraced her daughter, kissing her forehead “How is my not-so-little blossom?”

“We were discussing queenly behaviours.” Liam stepped up.

Eclipsa smiled “Discussing how you’ll be queen while the king lives! Treason!”

Everyone laughed as Marcus chided his mother for watching too many times Magnificent Century, the Turkish series about Suleyman the Magnificent, which made the room laugh even harder.

Hana took a better look at her daughter: she had grown into a beautiful woman indeed, with thick, black and long hair, hazel eyes and freckles all over her face and part of her upper body, with her Eclipsa’s lips and questioning and defiant look. Many of their neighbours whispered what a wanted heiress she was, despite only remaining thirteen monarchies in Europe, the Auvernese having been abolished after Reena’s death. Isaac Achilles tried to put on a coup and seized the throne for a hundred days, until the military itself formed a government that overthrew him and kicked the Achilles family, proclaiming Auvernal a republic in 2030.

Cordonia had been growing strong, thankfully, and with the Council’s help. Bartie had joined when he turned eighteen, and he was now a man of twenty-one, taking on more duties as his father aged. Duchess Savannah had long retired and passed her time between Texas and Cordonia.

As Stephanie carried on practising the investiture, she and Eclipsa looked at one another. They had gone through much, perhaps too much, but made it to ���Happier Ever After’ in the end. To the investiture, it was rumoured that Amalas’ son, Henrik, would start vying for Stephanie’s hand. When Hana asked her daughter about it, she gave it a thought before her wise answer calmed her stormy thoughts “I am aware of what an advantageous match would but, but I also know that I am young and have many years ahead of me. I shall entertain him, but I won’t give him hope or anything like that. My marriage must be a sensible choice, not only for myself, but for Cordonia, for he will be the first Prince Consort in many centuries, if it comes to pass.”

Eclipsa whispered her to talk and both went to a quiet corner “How are the plans going? The investiture is this Friday.”

“Everything goes according to plan. I think we may be more nervous than Missmiss.”

They both chuckled, smiling wide at Stephanie’s adorable childhood nickname. It seemed like yesterday when they decided on that name based on Eclipsa’s deceased mother. Hana saw how much Eclipsa had missed her over Stephanie’s life. Indeed, Sonia Palacios had been fire incarnate, and that fiery temper that could light up all of Europe had passed onto Eclipsa and now Stephanie. Marcus was definitely Hana’s son, with her same reserved but sweet nature, her ability to learn new courtly skills, as well as her not-so-secret competitiveness.

He smiled at his sister and Stephanie smiled back, “Please, carry on. We were just checking in.”

Eclipsa and Hana found a corner and silently watched as Stephanie repeated the speech word by word, and Hana was quick to observe how she secretly fidgeted with the hem of her dress. When she looked at her, she gave her an encouraging smile. Marcus kept doing goofy faces, but Stephanie remained unfazed and composed, which was a great accomplishment.

Stephanie knew this was the turning point in her life. Everyone was counting on her. Despite her mothers being the best and most supportive women on earth, as well as the magic of her therapist, not everybody was as wonderful as her moms. The Council pressed on her being perfect, especially Countess Madeleine, in a rather passive-aggressive way. The woman was the embodiment of ‘forever stressed’, being a countess in Cordonia and a duchess in England by her own right, a personal gift from the king for her loyalty after Mr. Godfrey’s arrest. He had died when Steph was but a child.

The next thing coming up was the dress fitting, and Stephanie hated furs and tight, old clothes. Instead, she had convinced Uncle Liam to use a mantle that was made of environmentally safe material and made by Cordonian local textile commerce, and that she wore a tiara and only used the heavy crown on her coronation day only. And thus, Lady Lorelei, her grandmother, had commissioned the best jeweller in the whole world to make a tiara of a mighty heiress. It’d arrive three days before her investiture.

As she tried her white gown, which had been suggested by Duchess Kiara to signal her marriage and commitment to the country, and which the whole council approved, she looked at herself. Her hair, which she had been growing since she was fifteen and was now 48cm long, above the average woman in Cordonia, she thought to herself that, if she dared blink for too long, she’d soon be dressing for her coronation. And being crowned meant having buried a great man.

He was such a splendid king; she knew she’d never be like him. She had been too afraid to tell him, for she didn’t want to hurt his feelings, but a small part of her told her that change was good. He was Liam the Benevolent, the Brave, the People’s King. And she? She was not even a Rys by blood. Her legal name was Ice-Lee. And he had married when Stephanie was 12 to a wonderful woman: the now Queen Wren, a Senegalese self-made billionaire who had stolen Uncle Liam’s heart from her mother. Theirs was a story as beautiful, though lacking the epicness of her mother’s:

Liam had been on a diplomatic trip to Senegal and by then, Wren was a minister and a speech of hers had drawn the heartbroken king. The two of them wouldn’t see one another until she came to a diplomatic visit. They formally had dinner, and, according to Uncle Liam, her striking mind, her wicked wit and her incredible oratory speech had his heart right there, not to mention her striking brown eyes, which had small streaks of violet if one looked closely, an unusual case in a black woman who had been born with the Alexandria Syndrome.

Apparently, before coming to the country, she quitted politics, which, according to her, were not her calling, and invested in a new social media and soon gained incredible wealth overnight, over a million downloads. Right now, it was the second most popular social media, behind Pictagram, though it looks like it will dethrone it any day now.

This time, as Mama Hana had told her a million times, Liam wasted no time in asking her to be his wife and she accepted. She was crowned three months later, the first ever solo coronation of a queen in Europe.

“How’s my little cherub doing?” A familiar voice asked.

Stephanie turned around to look at her mother, Hana. In a way, Steph saw her face in her own. Hana kissed her forehead and squeezed her hand “I hope you like my design.”

“It’s splendid, Mama. You and Aunt Kiara have outdone yourselves.”

Hana smiled “Aunt Penelope helped.”

They both smiled “May I have a moment alone with my mother, please?”

They all left as they curtsied and Stephanie sat on the chair “I have been thinking of something.”

“Tell me, darling.”

She fidgeted with her hair “After the coronation, I’d like to donate my hair to little girls with cancer.”

Hana’s face lightened up “That is amazing, my girl! I am glad that me and your Mummy inspired you into joining the tradition!”

“You did. But…I’d also like to do it for my people, and I don’t want it to be propaganda. I want to earn my subjects’ respect. I don’t want their loyalty just because of Liam’s sake. I want them to trust me to be capable of me doing the job because of who I am.”

Hana’s face worried “Why would you say that?”

Stephanie sighed “I don’t think I deserve it, okay?!” She finally snapped “I feel like I am made heir only because I came out of the womb of the woman a king couldn’t have and wanted to immortalise his love for her! His children, Prince Fabian and Dominic, deserve the crown, not me! I will be the end of the Rys line!” Tears started flowing, and Hana placed her young daughter’s head on her chest.

“Don’t say that, baby! I know that you came here in an unconventional way, but just because you were not born into a dynasty doesn’t make you any less worthy of it. You are strong, capable, smart and qualified enough. And yes, Fabian and Dominic are wonderful boys, but he has recognized you as his legitimate heir many times!” She lifted her chin “When he announced it, I won’t lie: I was scared. To me, duty had been the tomb of life, but the moment I saw Liam with you, I knew it wasn’t entirely true. You’ve proved again and again that you have what it takes.”

Ten years ago

Stephanie had turned eight years old, and Hana observed her as she greeted the guests herself, getting every title right. Hana smiled, and the Dowager Queen leaned on her side “You’ve done an splendid job, my dear. Leo got them wrong on purpose, and Liam was painfully shy, the poor boy. She has Eclipsa’s charisma and your gentle charm.”

Hana smiled wistfully “I hope so. She is everything I wanted to be when I was younger.”

“You’ve outdone yourself. Look at them, they are in love with her! When her Season comes, we might have to draw a list.”

Both women laughed.

“That won’t happen for a long time, hopefully.”

Stephanie chuckled “I remember muttering to myself saying, ‘okay, this one is an earl, so he’d be my lord, and the dukes are graces, like mama’.”

Both chuckled, and Hana’s mind was flooded by yet another memory.

“Or do you remember when, at twelve, you singlehandedly managed your first press questions? I was so proud that day!”

Seven years ago

“Princess Stephanie, here!” The journalist cried.

“Princess Stephanie!” Ana de Luca placed herself between the princess and the door “Everybody saw that outfit you wore with Lord Beaumont! What do you think of people saying you’re too young for tank tops?”

Hana observed in anger and horror as they asked similar vicious questions. She balled her fists and was about to tell them off when Stephanie’s voice surprised her “I think that people should care less of what I wear and more of the true elephant in the room here: that a school burned down and we lost three children to the fire, yet all I see is the fact that I wore once a top. Sort out your priorities.” She lifted her chin and passed her way towards Eclipsa, who had a beaming smile on her face.

Hana hugged her daughter and whispered “Well done, my girl.”

“Look at them, I’ve never been able to make the flashes stop as fast as you, baby!”

Stephanie smiled triumphantly “I am glad to see that the press has changed much ever since. But I just said what everybody was thinking.”

Hana smiled knowingly. She was now legally an adult, but she had much to learn about the world and what people in power really had in their minds.

Four years ago

“I think a tour would be splendid!” Duchess Adelaide cried.

“Wherever should we go then?” Queen Wren inquired.

“Maybe Italy, Spain, New York—,”

“And why not, I don’t know, Senegal, Philippines, Peru, India? Why must we stick to the USA and the Mediterranean countries?”

Madeleine was rendered speechless to say the least. Many muttered, both in agreement and disagreement, and Hana was both impressed and proud, as well as scared for the possible criticism of the Council.

Bartie cleared his throat “Please, explain your point, I’d love to hear it.”

“Yes,” Liam added in support “please, go ahead, Your Highness.”

“Well, these countries have each important relevance, and are rarely visited. They may not be as wealthy in money, but they can still give us an overlooked richness, not to mention it’d make us stronger in other countries. We could have many benefits with these countries, and the more allies we have, the better, right? We certainly could use two or three more.”

Wren gave her a wide smile “I agree with her. Many often look down on these countries, but the other things they have to offer could be truly useful to us, and we could learn a thing or two about them. And a certain percentage of immigrants are from said countries, are they not?”

Madeleine quickly typed on her computer and nodded “Indeed. Over 70% of our immigrants are from those countries.”

As the adults debated on which countries to visit, Hana mouthed her pride to her daughter. Steph smiled.

Hana beamed at the memory. Diplomatic relations changed for the better since then. She took her daughter’s hands in her own and squeezed it “See? You’re not who you are on a whim, my darling. You’re here because you’ve earned it. You’ve proven time again and again that Liam made the right choice, biased or not. You deserve the throne, and everybody else thinks it the same!”

“Indeed,” finished Eclipsa, who had been listening for a while “A strong queen is just what this country needs.”

The three women hugged in a family sandwich. If she had any doubts of deserving the throne, she did not anymore.

It hadn’t been easy for Hana, raised in pressure to be perfect in everything, to raise a future queen, but watching the fruits of years of therapy, honest talks at three in the morning with her wife and encouraging herself that she was doing the right thing had now resulted in what she dreamt of many times: a woman who could speak for herself, unafraid of who she truly was and true to herself and proud of who she was. Everything it took her more than twenty-four years to become.

And having found her people and a great supportive network had helped not only Missmiss, but Hana as well, counting of course with her incredible wife.

And when Stephanie knelt before King Liam as he invested her Crown Princess of Cordonia, she could breathe in peace knowing that years of work had proved worth the tears and suffering of her youth, for raising Stephanie had helped her with herself and the people around her, and the old Hana would be proud and amazed by this new Hana.

And that brought her the greatest feeling of accomplishment.

#playchoices fanfiction#the royal romance#the royal heir#hana lee#king liam#liam rys#prince liam#hana lee x mc#mc: eclipsa ice#stephanie ice lee#princess stephanie ice#HLAW day 4#hana lee appreciation week#HLAW#liam x oc

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

"The Golden Son" Cover Symbolic Redesign Project

The book, “The Golden Son” by Shilpi Somaya Gowda is a book with much symbolism in regards to the main character Anil. From the chess pieces mentioned variously throughout this book to the weather of India described in each scene in which Anil thinks about or goes to India. This new cover of the novel reflects more on what Anil endured throughout this book. The golden, yellow, background is symbolizes success, triumph, fortune, and even royalty. Despite being the color mentioned in the title of this book, Anil himself becomes successful and fortunate after the years of suffrage he is faced with. From helping his best friend/lover find her true self and become safe, to finding an identity within his own family after the death of his father. Anil becomes successful in his life and practice after medical school in Texas as well as split the family business/duties in India among his brothers. Lastly, overall, Anil comes from a family of royalty. Royalty in the sense of high status, as they are one of the richest families in the village, making Anil heir to the thrown to continue this legacy.

In relation to the royal symbolism behind the background color, the font in which the title is written also relates to royalty. The sophisticated nature of the cursive letters reflects Anil's mature mindset. Being the oldest son he had dealt with taking on his father's role in resolving disputes, as well as creating a life outside his family by going to medical school. This new competitive environment Anil put himself in forces him to focus on being successful as he has no role model to look up to (because he is the only one in his family to go to medical school). Again, to reflect the royal nature of this font, it symbolizes the high-status Anil originates from and at the end uses to help his best friend Leena achieve freedom.

Unlike the font and background color of the new cover art, the symbolic image in the middle no longer reflects the maturity and elegance Anil has/had within him throughout the book. But now the struggle and pain he endured. The image of a person carrying a heavy load of books uphill reflects the work Anil put in, within his character development. Anil had to face discrimination and racism, the stress of medical school and family, and personal burdens to finally be content with his life. The books reflect his challenges, mostly medical school, family, and even Texas has he had to obtain his U.S. citizenship. Anil is found carrying books because it is mentioned multiple times in the novel itself that he was a kid different from the rest of his family. Always reading and being studious because of his desire to go to medical school.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

LETTER FROM IRAN

By Joseph Kraft December 10, 1978

A story from the Kennedy years which has the rare quality of being true is that once, when the President was otherwise engaged, Dave Powers, his original guide to the poor Irish of Boston and later a combined companion and jester at the White House, was delegated to kill a few minutes with the Shah of Iran. Subsequently, he was asked how he liked His Imperial Majesty. “Well,” Powers said, “he’s our kind of Shah.”

I was reminded of that story when I saw the Shah a few weeks ago here in Teheran. At that point, Mohammed Reza Pahlavi wasn’t anybody’s kind of Shah. He received me, as he had on several of my previous visits, in a ballroom on the second floor of the Niavaran Palace, on the northern outskirts of Teheran. He looked pale, spoke in subdued tones, and seemed dwarfed by the vast expanse of the room, with its huge, ornate chandeliers and heavy Empire furniture. He wore a double-breasted suit whose blackness suggested mourning. He started with an apology. He was sorry to have kept me waiting. The American and British Ambassadors had been in to see him. “They tried to cheer me up,” he said. “As if there were anything to be cheerful about.”

I expressed surprise at—and, indeed, felt some suspicion about—this show of gloom. There had been demonstrations in many parts of the country, and strikes, but Teheran, apart from the university, seemed calm, and the Army was in thorough control. Moreover, the opposition was headed by the Moslem clergy, and they were clearly divided. Surely, I said, the factions could be played off against each other.

“Possibly,” the Shah said, shrugging his shoulders in an elaborate show of disbelief.

I pointed out that the leader of the lay opposition, Karim Sanjabi, was due to go to Paris to see the most intransigent of the religious leaders, Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini. The gossip in Teheran was that a compromise deal was in the works. Sanjabi would win Khomeini’s blessing for a coalition government. The coalition would make reforms but maintain the monarchy.

The Shah expressed doubt that Khomeini would agree to that. “Certainly not with Sanjabi,” he said.

I further noted that, while there was obvious unrest in the country, the Shah himself had lifted the lid by easing up on security and initiating reforms. Maybe all that was required was a slower pace and more publicity for the changes he had made. I mentioned that one of the problems was corruption in the royal family. He had decreed a new code of conduct for royal behavior, but it had not been published. Could I get a copy? The Shah agreed—with a weary air.

If worst came to worst, I went on, there was always the Army. The military was strong, and its leaders were loyal. The Shah said that force had its limitations. “You can’t crack down on one block and make the people on the next block behave,” he said.

I asked him if the Army leaders realized that. “I hope so,” he said. He went on to mention his son and heir, Crown Prince Reza, who, at eighteen, is now an air cadet in Lubbock, Texas. The Shah said that he might not be able to pass all his powers on to his son, but he could at least pass on the throne.

I remarked that I had never seen him so sombre, and asked when the black mood had begun.

“Sometime in summer,” he said.

“Any special reason?”

“Events,” he said.

I intimated that maybe he was overdoing the blues to elicit sympathy and perhaps support from the United States. “What could America do?” he asked.

I said that that depended upon what happened, and asked him what he thought that might be. “I don’t know,” he said.

I asked him what his advisers thought was going to happen. “Many things,” he said, with a bitter laugh, and he rose, indicating that that was all he had to say.

The day after seeing the Shah, I drove, with an Iranian friend who had agreed to serve as an interpreter, to Qum, a religious center with a population of roughly two hundred and fifty thousand, about seventy-five miles south of Teheran. Qum is the country’s foremost training center for the priests—or mullahs, as they are known in common parlance—of Shiite Islam, the creed of ninety per cent of Iran’s thirty-six million people. Shiism was made the state religion at the beginning of the sixteenth century by a new dynasty, the Safavids, who needed to dig in against the Ottoman Turks. The Shiites form the minority—and largely Persian—branch of the Moslem religion. As distinct from the majority branch—the Sunnites (who for centuries vested the line of authority from Mohammed in a caliphate that followed the tides of history from Damascus to Baghdad and thence, with the Turks, to Constantinople)—the Shiites traced the line of descent through the Prophet’s son-in-law, Ali. Ali, according to Shiite law, was the first of twelve Imams, or holy leaders. The twelfth Imam withdrew from this world and is due to return some time as a Mahdi, or Messiah. Ali was buried in An Najaf, and his son, Hossein, in Karbala, and those cities, now in Iraq, are, after Mohammed’s tomb in Mecca, the principal shrines of Shiite Islam. The eighth Imam, Reza, died in Meshed, which is a town some five hundred miles east of Teheran, and is the most holy shrine in Iran. Reza’s sister, Fatima, died in Qum, so the city includes Iran’s second holiest shrine as well as many madressahs, or seminaries.

The most renowned students of Islamic law in Qum, Meshed, and other major cities are referred to by the title Ayatollah, which means, literally, “Sign of God.” For roughly the past fifty years, the Ayatollahs of Qum have been the dominant religious leaders in Iran. Ayatollah Khomeini, though born in eastern Iran, was educated in An Najaf, and then in Qum, and subsequently taught in Qum. He achieved national stature between 1961 and 1963 as the leader of the opposition to various features—including coeducation and, many say, land reform—of what the Shah called his “white revolution.” In 1963, Khomeini was expelled, and moved to the shrine of An Najaf. The radical regime in Iraq, which in 1975, after years of bickering, reached an accommodation with the Shah, forced Khomeini out last September, when troubles became intense in Iran, and he moved to Paris. He had been succeeded as the dominant figure in Qum by Ayatollah Shariatmadari. For most of the past dozen years, the madressah students have made Qum a center of opposition to the regime. Professor Michael Fischer, of Harvard, who spent much of 1975 in that city, described the atmosphere at the time, in a monograph he called “The Qum Report,” as “one of siege and courageous passive hostility to a state perceived to be the stronger, but morally corrupt, opponent.” The present wave of troubles was set in motion early this year by violent demonstrations against the Shah in Qum.

I had telephoned ahead for an appointment with Shariatmadari, and had been connected with a Pakistani aide of his named Seyyed Rivzi, who spoke English. Rivzi told me to be in Qum by eight in the morning, because His Holiness, as he called Shariatmadari, went to the mosque at nine and spent the rest of the day in prayer and meditation. My translator friend and I arrived before eight and, with the help of directions from the local police, found our way to Shariatmadari’s quarters. He lives in a narrow back street, paved with white brick and lined with yellowish walls. There are doors in the walls every ten yards or so, and, behind the doors, courtyards leading to buildings that are used as offices and houses. We were first shown into an office, where we were received by Rivzi, a fat, middle-aged man wearing spectacles and a black turban; he kept pushing the turban back from his forehead in order to scratch his scalp. Rivzi said that I was in luck, for His Holiness was feeling ill that day. Because he was not well enough to pray, there would be ample time for the interview. Rivzi asked me to disclose my questions in advance. He would write them down in Farsi and then read them off to His Holiness—that way, there would be no mistakes. I began reading from a list of questions I had prepared. He repeated them in English, then set them down in Farsi, and read them back to my Iranian friend for his approval of the translation. A couple of times, the English version of my question differed significantly from the original, and at length I pointed out one of the discrepancies. Rivzi said, “I was not trained as a reporter, but in the past few months I’ve been the interpreter for sixty-eight different interviews. I’ve become quite good at framing questions. I hope you don’t mind a little editing.”

After the questions had been given, edited, and translated, we moved across the street to see Shariatmadari. He is a man of seventy-six, with a white beard, a frail frame, and a thinnish voice. He, too, wore a black turban and glasses—in his case, thick glasses over weak but distinctly friendly eyes. He received us in a bare, whitewashed room lit by a single electric bulb, which dangled from the ceiling. There were some uninteresting rugs on the floor, and a curtain hung across the window on a string. Shariatmadari was lying down on an opened crimson bedroll, with his head and shoulders raised on a purple pillow. Rivzi and another aide, whose function I never discovered, sat, legs crossed, facing His Holiness. I sat parallel to him, also cross-legged, but with my back against a wall. In the course of our talk, which lasted several hours, various people came in to see Shariatmadari, kissing his hand, pressing petitions on him, often with money between the pages, and then hurrying away. A telephone by the bedroll rang frequently, but it was answered only rarely, by the non-Pakistani aide, who usually managed to pick it up after the caller had stopped trying to get through.

Shariatmadari began by asking about my trip down to Qum. I said that it had been easy but that we had noticed a lot of troops in the town and, on the wall of his house, a scrawled sign saying “Death to the Butcher Shah.”

His Holiness said, “I don’t know what is happening in Iran. I never saw a nation in such a spirit of revolt. It is erupting like a volcano, and, like a volcano, after building up pressure for years and years it is impossible to stop.”

My first question had to do with the revival of religion in Iran as a political force. Shariatmadari said, “Religion used to be considered marginal—apart from the mainstream of events. Now it has become much stronger than before. The reason is that religion provides answers to problems of conscience. It provides a vantage point for fighting injustice. In our Shiite religion, spiritual leaders are ready at all times to assert the truth and the right.”

I asked him what injustices he had in mind. He said, “We have never had free elections. The elections in the past were all dominated by local magnates or the consulates of foreign powers. The consequence has been that we now have laws repugnant to Islam and to the public interest. For example, alcoholic beverages are permitted. There is gambling. There is illegitimate sex—by that I mean sexual relations between people under twenty who are not married. The authority to marry is in the hands of civil officials. But it should not be. Marriage is not a deal or a contract. It is something spiritual, and so it should be performed by the religious authorities.”

At that point, there were sounds of firing in the distance, and I started. “Don’t be afraid,” he said. “We’re used to that kind of noise.”

I asked him to tell me about the troubles in Qum. He said, “From the beginning of the disturbances in Qum, we have asked people to speak their minds, but with calm and dignity, not in a provocative way. But I remember a few months ago a company of soldiers headed by a major general walked into these premises and announced they were on a mission from the government. They started breaking windows and shooting. One person was killed on the spot and another died in the hospital. Later, the government apologized. But I ask, ‘How can you apologize for killing people?’ Had it been the Prime Minister’s house, would it have been enough merely to apologize? Such an action alone is adequate for me to declare a holy war or a revolution. That might have happened if I were not devoted to the cause of moderation.”

I asked him how he would rectify the many injustices and wrongs he had cited. He said that he favored a return to the constitution of 1906—a document that a liberal movement with support from the clergy had wrung from the Qajar dynasty, which preceded the family of the present Shah. The 1906 constitution provided for, among other things, a supreme council of five religious leaders who would have a veto right over all laws. “If they found the laws repugnant to Islam or to principles of justice or against the interests of the majority,” Shariatmadari said, “they could reject them.”

I asked what would happen if the five religious leaders disagreed among themselves. He said, “That would not be possible, for they represent the highest spiritual authority.”

I persisted with the question about a possible disagreement. “In that case,” he said, “the issue would be referred to the highest spiritual authority in the land.”

I assumed he meant himself, and any doubts on that score were settled by Rivzi. He said, “His Holiness would have the final word.”

I remarked that many people in Iran, and in other parts of the world, had different views from His Holiness on such matters as religious liberty, land reform, and the role of women. He cut in before I could develop this theme. “The journalistic community in the world,” he said, pointing a bony finger at me, “has constantly made the libellous charge that we religious leaders are anti-progressive and reactionary and anachronistic. That is not the case. We want science, technology, educated men and women—physicists, surgeons, engineers. But we also want clean and honest political leaders. Those who make the charges against us are themselves reactionary, because their goal is to stop us from instituting a government of hope. The government of God is the government of the people by the people.”

I said that I would still like to know where he stood on the issue of equal rights for women—coeducation, for example.

Very smoothly, as if there were no break in the line of thought at all, he asked me how many Presidents there had been in American history. I said that it wasn’t altogether clear whether the figure was thirty-eight or thirty-nine.

He said, “You come all the way over to Iran to ask about the rights of women here, and you don’t even know how many Presidents you have had in your own country.”

I explained that the matter was complicated by the fact that Grover Cleveland had been President twice but not consecutively. I said that for the sake of argument we could assume there had been thirty-nine Presidents.

“How many of them have been women?” he asked.

I said that none had but that that seemed to me beside the point. What, for example, did he think about coeducation?

He said, “I’m not opposed to the education of women for all kinds of tasks. But I do not want coeducation. I want to separate the schools of learning from the schools of flirting. We in Islam don’t look on women as playthings, accepted as long as they are young and beautiful, and then cast away. In Islam, the older the woman, the higher her status. We know that in coeducational schools there is a corruption of moral values, which is reflected in the police records. The girls develop certain relations, and some have illegitimate children, and others have abortions. The girl loses her self-respect and her status in society. Either she suffers a great personal loss or she takes up another way of life—prostitution.”

I asked him his opinion of abortion. He said, “In Islam, abortion is considered murder. Therefore, abortion is not permitted.”

I asked him his views on birth control. He said, “Birth control depends on certain circumstances. In small, overpopulated countries that have no land, birth control is acceptable. But in our country, where the population occupies only one-fifth of the land, there is no need for birth control. Procreation should be free unless there is a particular problem. In our country, that problem doesn’t exist.”

I asked him whether there was equality in Islam for people of other religions. He said, “In Islam, Christians, Jews, and Zoroastrians are all accepted as equal—unless they become a Fifth Column for foreign meddling in this country. Jews are accepted as Jews but not as defenders of Zionist aggression.” He then referred to the Baha’i sect, which began as a reform offshoot of Shiite Islam, and has been popular in Iran, particularly among educated people who have done well in business and politics. He said, “Baha’i is accepted as Baha’i per se but not as a clique dividing up government posts among themselves and working for the foreign interests.”

I asked him where he stood on the land reform that the Shah had decreed in 1963. He said, “Land reform is a question of the past. Even if there were some objections made at the time, there were no objections to the principle of land reform but only to the means of implementation. The Shah could have done the same thing in accordance with the principles of Islam. That is typical of his regime. In order to build roads and streets, he destroys the house of an old woman and does not give her another house.”

At that point, Shariatmadari reproached me for picking out one issue at a time instead of dealing with the culture as a whole. “Culture is a mixture of many interwoven things,” he said. “You cannot in fairness just pick on individual matters as if they were unrelated. For example, in the West you cannot conceive of a banking system that does not charge interest on loans. But in Islam, for many different reasons, our view is that interest should not be charged.”

I said that that was true; no one in the West could understand how a government without the power to raise interest rates could control inflation. I went on to say that his point seemed valid, and so I would shift subjects. I asked him where he stood on the issue of meetings with representatives of the Shah.

He had had some “unofficial meetings,” he said, and went on, “But we can’t have official meetings. The religious authorities will participate in all offers of a solution to the present problems, but only with a fair and just government and parliament. We can coöperate fully only after free elections have returned a popularly chosen government.”

I said, and he acknowledged, that the Shah had tried to institute some reforms directed toward liberalization of the regime. I observed that many Americans felt that President Carter, by his human-rights campaign, had played a role in fostering those reforms.

Shariatmadari said, “Carter’s human-rights policy has not been a very important propelling force, though it has not been totally without effect in pushing liberalization. But in Islam we have some skepticism about the sincerity of Carter’s human-rights approach, because he doesn’t apply it to the United Nations. In the U.N., five countries have the veto. That means we are not equal. But the Americans don’t say anything about that.”

Acouple of days later, I flew to Isfahan, with my Iranian friend again accompanying me as an interpreter. Isfahan, as the 1966 Hachette Guide proclaims with unwonted effusion, is “one of the most marvellous places in the world.” The city lies on a plateau watered by a large oasis and a lovely stream. Shah Abbas I—the greatest Persian emperor, not excepting Xerxes and the three Dariuses—made it his capital at the end of the sixteenth century; at that time, it had a population of about half a million, and was among the largest cities in the world. I remembered from a previous visit, a decade ago, broad, tree-lined avenues; a magnificent central square, the Maydan-e-Shah; the extraordinary Bridge of Thirty-three Arches; and a general air of refined elegance. But even from the air, I could see burgeoning suburbs and smoke from factories—signs that change had come to Isfahan.

A local official, who asked not to be mentioned by name, rapidly brought me up to date on developments in Isfahan. He said, “Five years ago, there were five hundred and sixty thousand people in Isfahan, and this was one of the most beautiful cities in the world. Then the Shah decided that there was too much administrative and economic concentration in Teheran, and that he needed to decentralize. So he put a steel mill here. And an airbase, with a helicopter training center. Naturally, foreign companies followed suit. Bell Helicopter came in with the training base. Du Pont put a plant here. Now we have more than a million people. The doubling in five years of a population that had been stable for three hundred years has changed everything. This used to be an educational center, with a university, many religious schools, and lots of music. Now it is an industrial town. Over three hundred thousand workers have come in from the countryside, most of them without their families. They live five or six to a room in the poorer quarter of town. They make good wages—a dollar seventy-five an hour—but they don’t have their families, and they’re miserable. Everybody else has been affected, too. The bazaar merchants used to be very important. Now the banks manage credit, and the engineers are the big shots in town.

“Students have grown up under the Shah, and they don’t know what things were like before development started. All they know is that the Shah promised that Iran was going to be like France or Germany. That isn’t happening. The huge surge in population means that services are spread too thin and are constantly breaking down. There aren’t enough telephones. It’s impossible to buy a car. The schools are jammed. Housing is scarce. During the past three years, there has been a recession, especially in building, and many laborers are out of work. So the students are in a mood to reject everything that has happened. They are turning back to the old days, and pursuing an idealized version of what things were like then. They are pushing the mullahs to go back and re-create the wonderful past. The mullahs see a chance to regain their prestige and power. The students provide them with a power base for putting pressure on the government to give them the consideration and importance they have been seeking for years. So the mullahs go along. That’s the dynamic of trouble in Isfahan.”

I asked about the circumstances relating to the declaration of martial law in Isfahan back in August, a month before it was declared in the other major cities of the country.

The local official said, “That’s a perfect example. All through the spring and summer, after riots in Qum in January, and in Tabriz in late February, this town was seething with unrest. The workers were demanding better housing conditions, and more money to meet inflation. The bazaar merchants were bitching about the loss of their old status, about price controls, and competition from the big banks and supermarkets. The intellectuals were complaining about the lack of freedom. The students were telling the mullahs to do their stuff, and the mullahs were saying ‘right on.’ About the first of August, a mixed group of workers and students occupied the home of the most prominent local religious leader, Ayatollah Khademi. The governor-general and the local Army commander went to Khademi and told him to get them off the premises. He tried, but he couldn’t. On the contrary, the crowds got bigger and bigger. At one point, maybe twenty thousand people were camping there. When Khademi tried to cool them down, the students turned ugly. They took down the posters of the Shah and put up posters of Ayatollah Khomeini. On August 11th, the military decided to clear the place. Troops moved in, threw tear gas, and pushed the crowd out at bayonet point. The crowd then went on a rampage. It burned down a bank and a hotel and fifteen other buildings. It threw a bomb into a bus for Bell Helicopter employees. That’s when martial law was declared. The bazaaris—the bazaar merchants—immediately went on strike and closed down their shops in protest. The madressah students stayed in their schools, but they demonstrated every day, always making more radical demands. On the night of August 21st, two high-school teachers, who had built up a large following of anti-government young people, were arrested and sent to Teheran. Next day, the kids hit the streets, and there has been trouble of one kind or another ever since.”

I asked for and was given the names of the teachers—who had been released after a month in custody. They had no telephones, so my Iranian friend and I picked one—Hassan Zehtab—and drove out to see him. He lives on the outskirts of town, in a neighborhood of narrow, twisting unpaved streets. The car could barely squeeze between the walls, and the puddles and mud in the road reminded me anew of the origins of the custom of removing one’s shoes before entering a mosque. Once we were in the neighborhood, we had no trouble finding the house; everybody we asked knew Hassan Zehtab, and where he lived.

Mr. Zehtab turned out to be a partly bald, moonfaced middle-aged man with a complexion slightly darker in tone than that of most Iranians. He was carefully dressed, in a suit, white shirt, tie, and sweater. I saw only two rooms of his home, and they were modest in size and bare of ornament. When we arrived, Zehtab was meeting in one of the rooms with about forty disciples. He agreed to see me, and we moved into the other room, with ten of his disciples coming along. I asked Zehtab to tell me a little about who he was and what he believed.

He said, “I’m forty years old, and I have been a schoolteacher here in Isfahan ever since I graduated from the University of Teheran, fifteen years ago. In all this time, I haven’t seen one truly free election, or one instance of concern on the part of those in authority for the happiness of the people. I think the only way to bring about the happiness of the people is through an Islamic culture. We’re given to understand that the ruling clique is talking about religion now, and putting on a turban and the white garments of holiness. But that is a mere pretense. Even a child can see through that. It is like the ceramic facing on the wall of a building. Everybody knows that beneath the facing there is a real wall, of a different material.”

I asked him if it was not true that under the Shah the country had taken large strides toward economic development over the past fifteen years.

He replied, “I have to say with great sorrow that our economic growth is based on a windfall called oil. If we consider where we are, and then where the progressive states like Japan are, we realize how little we have accomplished. When I think of Japan, I think of a verse:

Leila and I were fellow-travellers on the road of life; She reached her home, and I am still a vagabond.”

I said that even if some countries had done better than Iran, Iran had done quite well.

He said, “What we see here is inflation—prices for food have gone way up. What we see is the depletion of our oil reserves. At the present rate, we have only twenty years to go. What we see is an agriculture worth zero. We buy vegetables from Israel, wheat from the United States, onions from Turkey, meat from Australia, oranges from six different countries. Our industry is just an assembly line for products made in other countries. We would be poor fools indeed if we were satisfied with that.”

I asked him what would satisfy him. He said, “My ideal future is within the framework of Islamic law. That is the guarantee of happiness and a good future for society. On particular religious questions, I don’t find it in my area of competence to make answers. I leave that to the highest religious authorities.”

All during the interview, Zehtab, his disciples, my Iranian friend, and I were sitting cross-legged on the floor. I was extremely uncomfortable, and it must have been evident, for one of the disciples asked if I would like a piece of fruit. I said yes, and he took an apple out of a bowl in the middle of the floor. He began to peel it for me, but at the first stroke of the knife the blade separated from its handle. He held out the broken knife. “There you see it all,” he said in disgust. “Our country owns twenty-five per cent of Krupp in Germany, but in Iran we can’t even produce a knife that cuts an apple.”

Everybody laughed, and I began questioning the disciples. All of them were students or professional men between the ages of twenty and thirty, and had participated actively in many demonstrations against the Shah. They all supported Zehtab in his quest for an Islamic society. I expressed surprise that young men with professional training should be so drawn to a religion that seemed—to a Westerner, at least—not exactly with it. I went around the room, asking the disciples, one by one, a single question: “What drew you toward Islam?”

The first to answer was a mullah, in robes and turban, who had a degree in psychology from the University of Teheran. He said, “My love for Islam has grown because I have studied it and compared it with other religions.” The others—four students, two employees of the National Iranian Oil Company, an accountant, an engineer, and a physicist—all gave nearly the same answer. Two of them said that they had compared Islam with the teachings of a nineteenth-century European social philosopher—that is, Marx, whose name has been taboo in Iran—and found it preferable. Another offered the generalization “Islam offers a solution to the complications of our life.”

As we drove away, I remarked to my Iranian friend that the similarity of the answers was disappointing. “You don’t understand,” he told me. “They all followed the lead of the mullah. It doesn’t make for interesting answers, but it makes them happy.”

Ispent the night in Isfahan at the Shah Abbas Hotel. The clientele was entirely foreign—a sprinkling of Japanese, Indians, Americans, and Europeans. Apart from the sight of a section of the hotel which had been damaged during the riots of August, and an armed guard in the gardens, there was no sign of trouble.

Before dinner, I visited Wanda Hake, an American psychologist employed by the United States companies working in the Isfahan region. Mrs. Hake reported that most of the Americans in the area lived in a compound, largely removed from contact with the Iranians. They had the problems usually found in such communities. There was great boredom—especially among the children. Alcoholism was common among the women, and many of the children had drug problems. There was a good deal of contempt for the Iranians. “Because of their turbans, many Americans call them rag heads,” Mrs. Hake said. “That’s the nicest name they call them.”

Mrs. Hake had some guests, and one of them was a bazaar merchant from an old Isfahan family. “I could cry about what has happened here,” he told me. “It used to be a paradise of water and gardens and beautiful buildings. Now the town is full of strangers. There are the people from the villages. They live in shantytowns. There are ten thousand Americans. They drive up the price of everything—especially houses. A house that rented for five thousand rials per month five years ago now costs forty thousand rials per month. Many people are unhappy. One of my interests is a building project. My workers were Afghanis—three hundred of them. The other day, the government sent the Afghanis home. I know why: There was a crime wave, and they did a lot of the stealing. But nobody gave me any warning. Now what do I do?

“Lots of the young men come to see me about their problems. They don’t know how to deal with the young women sitting next to them in their classes. In the past, they had never seen any women, even mothers and sisters, who were not wearing a veil. Now they see miniskirts and bare arms and bare legs. They say to me, ‘What do they want, these women? What are they trying to do to me?’

“When I go to Teheran, I feel as though I were in Hell. Somebody could die right in front of you and nobody would do anything. Deep sadness comes over me when I see the uses to which we have put our oil wealth. So it is not surprising that there has been a political eruption. Five years ago, Khomeini was nothing. Now he is held up as the equivalent of the Shah.”

At breakfast the next day, I met a professor of religion at the university who had been educated at Harvard and Oxford. His family are members of the Baha’i sect, and he is going back to Oxford, at least partly because of religious persecution. He said he would like to talk about the state of religion in Iran, but only on condition that I not mention his name. I agreed.

He said, “As a student of religion, I read with great interest Toynbee’s ‘A Study of History.’ I always wondered why he felt that the next stage of regeneration in the world would be religious. I felt that religion had been on the run all over the world for centuries. In some places, there have been adjustments, but they have been made only slowly and painfully. Christianity accommodated itself to Darwin, but it was hard even in a tolerant country like Britain. Islam has experienced a number of shocks and adjustments. There have been several efforts to update the religion. But they have all failed. By and large, the clergy remains narrow, fanatical, and ignorant.”

He went on, “The merchants of the bazaars worked hand and glove with the mullahs. They were the two most conservative elements in the cities. The bazaaris usually rented land from the religious foundations, and made the foundations big gifts. But both the bazaaris and the foundations have been outmoded by recent developments. When I left Iran to go abroad to school, in 1960, this was still a backward country. Only a few cities in the country had running water. There were only about ten thousand people who had been or were at universities. Most industry was handicrafts, and about eighty per cent of the people still lived in rural villages. In 1970, when I came back, it was a different country. All the young people—and that is over fifty per cent of the population—were going to school. There are a hundred thousand university graduates now and almost two hundred thousand people in universities. On a normal weekend, between one and two million people drive out of Teheran in their own cars.

“The mullahs have been losing steadily through these developments. Their base was education. Now they have to contend against state schools and universities. They’ve lost the large landholdings they once had. Most of their endowments have been nationalized, and are controlled by the state. No one ever paid much attention to them until the present wave of troubles. The bazaaris have also lost great power. The banks and big companies have taken away their control over loans and credit. There are shops out in the streets—across from your hotel, for example—so people don’t go to the bazaar as much. And for a while there was price inspection as part of a campaign against inflation. That hit the bazaaris very hard.”

After a pause, he continued, “People now don’t remember what it was like in the old days. As late as 1955, I remember going with my father to a village in the countryside. The local khan—the head man—did justice the religious way. He cut off hands for thievery, splitting people’s tongues for talebearing. There was a peasant in the village with a beautiful wife. The khan took her, and the peasant complained to my father. The khan went out riding with my father, and they encountered the peasant. The khan took his riding crop and beat the peasant senseless.

“The oil boom ended all that and put it out of mind. But it also brought lots of trouble. Mainly inflation. There are buses now, and vegetables, but most people can’t afford them. Moreover, a lot of the money has been spent—I almost said wasted—on big projects and arms purchases that don’t do ordinary people any immediate good. And it has to be said that on the cultural side the Western world has not done well in Iran. Students coming back from Europe and the United States present the cities there as meccas for drunks, whores, and illegitimate children. They depict a total breakdown of morale. So to the difficulties of local adjustment there is added a tarnishing of the classic model. The West is seen xenophobically, as something frightening, and the search for old values is intensified.

“It also has to be admitted that the Shah, in his enthusiasm to build the country, ignored the people in it. The masses were left out of his development program. The bazaaris were left out. The mullahs were left out. He thought he could bring them along through economic progress without any accompanying change in ways of thought. The heart of the difficulty, though, is the new group of university students. From fifty to seventy-five per cent of them come from poor homes. They are very disturbed when they sit next to a girl in class. They feel a sense of guilt, a fear of being polluted—of secularization. All this takes the form of opposition to the regime as the bearer of Western values. The sexual drive pushes the students in the direction of religion, and the mullahs latch on to them to maintain their position of importance.”