#the museum of prelapsarian history

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Fallen London Travel Guide:

The Museum of Prelapsarian History

The Museum of Prelapsarian History is London’s preeminent historical institution. The past is best known as that segment of time that is entirely more popular, yet no less treacherous, than the shrinking future or the ever-stretching present.

#fallen london#fallen london travel guide#fl travel guide#my post#the museum of prelapsarian history#museum of prelapsarian history#tw human remains#tw skull#tw bones#tw animal skeleton#tw taxidermy#veilgarden

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Airs of Rebel's Outopos

Not every night in the new city is the same.

Inspired by a recent post and challenge - accessible here - that created "Airs of X" for their character's version of the City in Silver. Thought I'd have a go at trying the same.

The following city may include: spiders, militants, the breaking of cosmic law for ideological and personal gain, and fungi.

0: Beyond the walls, the distant crack of a gunshot.

1-3: Something humped and many-legged scuttles across the façade of a building, then is gone.

4-6: Shadowy figures cluster around a communal bonfire, laughing and chatting.

7: Tracklayers kneel around a patch of soil and pull strange-shaped devices from the dirt. Some devices hum. Others tick.

8-10: A hinge-hound nudges your side and whines in search of a pet. A bloody Ministry badge dangles from its lower-left jaw.

11-14: Urchins shriek and whoop from the roof-tops as they set off unlicensed fireworks at each other.

15-18: A visiting hobbyist looks on with awkward thanks as her automobile is pulled from the muck by a horse-sized, moon-eyed monitor lizard.

19-22: Spiders spill from an open sewer hatch in a shimmering, emerald tide.

23-26: Moonlight washes gently over the street. Somewhere else, the Internationale is played on union pipes.

27-30: A Young Stag recent to the city walks tentatively, but openly hand-in-tentacle with his rubbery nurse paramour.

31-34: A sudden clearing of the crowd: a reiver patrol has returned to the city. The booming calls and clicks of their terror birds reverberate in the bones.

35-38: False-skeletons from the Bone Market are an increasingly popular novelty fad. Most inhabitants find them kitsch. Some find them aspirational.

39-42: Noises erupt from an ampitheatre. Some are the cheers of the crowd. Some are the bellows of ancient creatures. Some are like nothing you have ever heard.

43-45: Anarchists and cladesfolk from the Roof conduct illicit business in open plazas. Weapons for allies; metal for flesh.

46-49: Phosphorescent scarab hives score mesmeric ribbons of viric and apocyan in the air. Passersby yawn and remember their beds.

50: The city’s vitality leads to miniature ecosystems within the depths of the costermongers’ carts. Leechberries parasitize the helpless flanks of the thunder melons but flee from the predation of needle-carrots. All hide from the vakeapple.

51-53: Amateur aero-enthusiasts and beast-breeders alike surround a recently-docked balloon from the Roof. Talk is already forming of a locally-grown air fleet.

54-57: The side of a wall is plastered with broadsheets, posters, hand scrawled drawings: faces of officials, constables, factory owners. A new arrival walks up to carefully, methodically cross out the face of an Iron and Misery overseer.

58-61: Webs shroud a cluster of streets like banners. Handmade signs advertise the services of silk weavers, scrimshanders, venom mixologists.

62-65: Raucous youth assemble for a trip to London. There is furious argument over whether to see the Museum of Prelapsarian History or Museum of Injustice first.

66-69: Poets of the Nocturnal Ooze movement seek inspiration in the city’s fungal-commons. The more fortunate find their lips and pens fecund with creative spore. The less fortunate are attacked by blemmigans.

70-73: Mist forms on the opposite side of a mirror. The eyes of the aurochs are upon you.

74-76: Tracklayers hack away at undergrowth recently and rapidly sprouted up through an alleyway. The city’s vitality is appreciated, but occasionally overwhelming.

77: Banners with popular phrases of resistance are plentiful on festival days. ‘CAST OFF THESE CHAINS’. ‘DUSK BEFORE DAWN’. ‘DO NOT FORGET. DO NOT FORGIVE’.

78-80: The rattling of an osteomonger’s tambourine. Bones! Bones for the picking!

81-83: Urchins crowd around the storefront of a recently-immigrated Unsettling Toymaker. They stare at a City Seeding automaton with longing and awe.

84-86: A field of puffballs explodes into a cloud of white, soft spores. For a few moments, it is as if false-winter has come to the city.

87-90: A diplomatic deviless discusses opportunities for collaboration with an opportunistic insurgent, mandibles slowly scraping at a tin of tobacco.

91: The air is hazy, clotted and copper-scented. The heart races; the teeth bare. Someone is committing Red Science.

92: Around the armory, the earth shudders and metal screams in birthing-cry: another mortar-beast claws its way out from the dirt to add to the city’s defenses.

93: Shapelings of all forms relax in an amber spring, bathing and contorting their flesh in novel configurations. It is difficult not to stare.

94: Droplets of slobber on your shoulders. Many eyes, watching. You curse whoever decided to hatch enough brachiating spindlewolves for them to breed true.

95: A visiting academic runs from a nearby lecture hall with pale face and heaving breath. “The sigils,” they moan. “They just…cut open the sigils!”

96: A dirigible from Station VIII drifts closer than it should have. Howitzer-beasts stir. Rockets sprout like teeth. A hush falls over the city for several hours.

97: Here, the city’s walls are slick with a viscid slime-mold that stains crimson and splotches like a fresh bruise. Is the city remembering an injury it once suffered? An injury it once inflicted?

98: A furious rain falls tonight, far from the tepid drizzles of London. By tomorrow morning, the city’s walls will have sprouted further still.

99: Tonight the walls drip with amber and the scent of lemon wafts from underneath the city: an auspicious time, according to local legend, for creating new beasts and new families.

100: For the briefest of moments, you can feel the pulse of the city’s heart. For the briefest of moments, there is no light, no cold, no death: only dark, warmth, and vitality. This is the Liberation of Night.

8 notes

·

View notes

Note

🖕 which characters do ur guys like to annoy lol

Ohoho you know the right stuff to ask-

Wadiya: His Amused Lordship. The text from their BAL ending about stealing meat from him first placed the idea in their mind, but their Persuasive stat of 173, low respectability, and his forced inclusion on the GHR cinched it- they will bother him until the earth itself is dust and rubble.

Leigh: The Jovial Contrarian. Leigh tries to annoy him, but always ends up being the one having to leave the Social Event because he's the one annoyed. It's hilarious.

Emery: The Soft Hearted Widow. He bites at the hands that feeds him. It's a pride thing.

Eliza: Mr Pages. Its very existence and level of power and status is an annoyance to Pages, but it also goes about it in pettier ways. Pages' favorite pens died painful deaths, in its claws.

Whism: With how they've been hanging around the Museum of Prelapsarian History? F.F. Gebrandt. They've been here for months. Please stop wandering the exhibits and leave.

Damodar: Weirdly enough, Furnace. They just have very different goals, and Damodar is so knowledge-inclined, they've been butting heads over this whole GHR Adventure, and she's just accepted that she can't do anything to not annoy Furnace, so she's leaned into being a thorn in her side.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Natural History Wing

The Natural History wing draws in the crowds, who come to gawk at the great beasts of the Mesozoic.

→ Stroll in the garden of bones A whole Jurassic forest's worth of animals have been reconstructed and mounted.

Fascinating Scientific accuracy is the order of the day. For every skeleton, an extensive label. For every room, a clear theme. Gebrandt's reconstruction of the history of life is rational, comprehensive, and perhaps even mostly correct.

A group of scruffy visitors sporting the heavy gloves and overalls of tracklayers are engaged in heated discussion in the Theropod Room. They appear to be taking extensive notes.

→

0 notes

Text

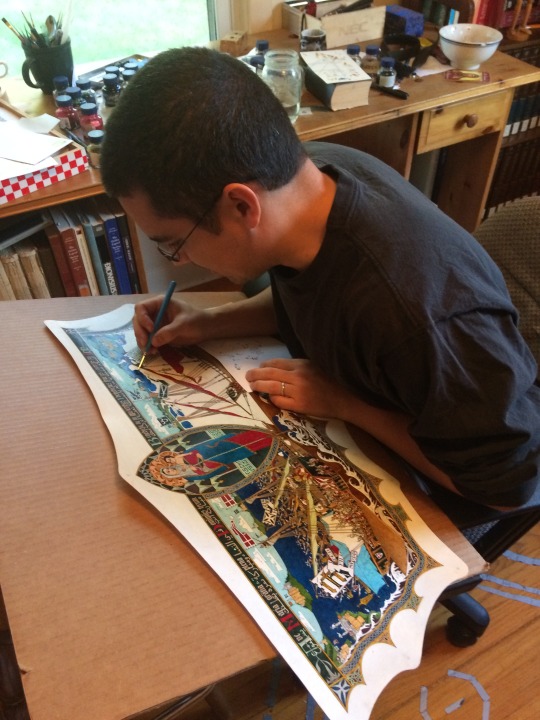

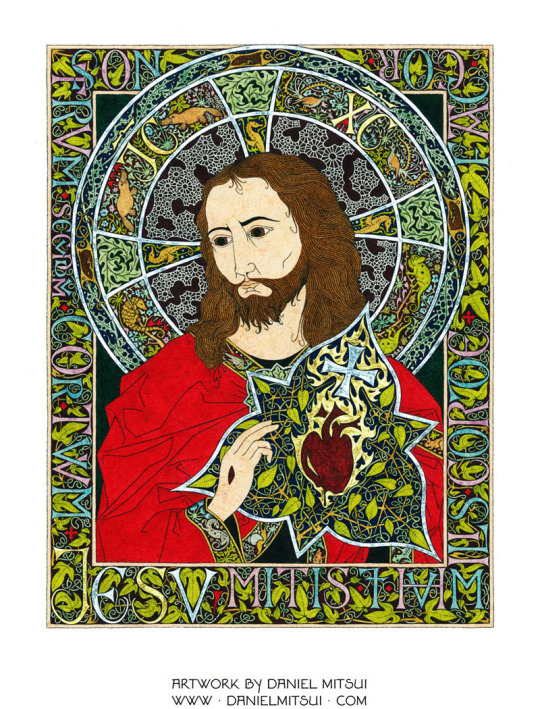

Meet Indiana-based Artist Daniel Mitsui

DANIEL PAUL MITSUI is a Hobart, Indiana-based artist specializing in ink drawing on calfskin and paper. His work is mostly religious in subject, inspired by medieval illuminated manuscripts, panel paintings and tapestries. www.danielmitsui.com

CATHOLIC ARTIST CONNECTION: Where are you from originally, and what brought you to Hobart, IN?

DANIEL MITSUI: I was born at Fort Benning, Georgia, where my father was an infantry officer. I grew up in the suburbs of Chicago, and lived in Chicago for most of my adult life. About two and a half years ago, I moved with my wife and four kids to Hobart, Indiana, which is sort of the easternmost edge of Chicagoland.

How do understand your vocation as a Catholic artist? "Catholic Art" can mean a number of different things: art that happens to be made by a Catholic, whatever it is; art that communicates Catholic ideas and values; art that explicitly treats the Catholic religion as its subject; or art that is considered "sacred" art, meaning that it is intended to communicate religious truth and to assist prayer.

Most of my artwork is of this last kind, so I understand my task as twofold. First, I do my best to follow an established tradition as far as composition and arrangement are concerned. Sacred art should corroborate sacred scripture and liturgy, and the exegesis of the Church Fathers - because it too is a means by which the memory of Jesus Christ's revelation is carried forward through the centuries.

Second, I do my best to make the art as beautiful as possible, because the experience of beauty is a way for men and women in a fallen world to remember dimly the prelapsarian world, and to grow in their desire for reunion with God. As I wrote in one of my lectures:

It is important "not to consider sacred art a completed task, not to consider any historical artifact to be a supreme model to be imitated without improvement. To make art ever more beautiful is not to take it away from its source in history, but to take it back to its source in Heaven. Sacred art does not have a geographic or chronological center; it has, rather, two foci, like a planetary orbit. These correspond to tradition and beauty. One is the foot of the Cross; the other is the Garden of Eden."

I am Catholic, and an artist, so I have no objection to being called a "Catholic artist.” However, I do not want to make an advertisement of my personal faith or piety, to suggest to other Catholics that they ought to buy or commission artwork from me because of the sort of person I am, rather than because of the artwork's own merits. An artist who would make an advertisement of his personal faith or piety has received his reward.

At this time, my personal mission is to complete a large cycle of 235 drawings, together making an iconographic summary of the Old and New Testaments and illustrating the events that are most prominent in sacred liturgy and patristic exegesis. I call this the Summula Pictoria, and I plan to spend the next twelve years of so working to complete it, alongside other commissions. I already have spent more than two years on it, mostly on preliminary research and design work.

Where have you found support in the Church for your vocation as an artist? The Catholic Church is of course much more than its institutional structures; it is all the faithful. Most of my patronage comes from private individuals rather than parishes and dioceses. I do receive some commissions from ecclesiastical institutions - in 2011 I even completed a large project for the Vatican - but I do not go out of my way to secure them. In ecclesiastical institutions, there tend to be committees involved, and a whole lot of politics; the usual result is that an artist spends time preparing proposals, reserving his most interesting ideas, and just fighting for permission to make the best artwork possible. I feel sorry for artists like architects and sacred musicians who, by the nature of their medium, have to do this. I avoid it whenever possible.

I choose to make artwork that is small enough and inexpensive enough that private individuals can commission and buy it. I think this may be the future of Catholic art patronage; there is not much reason to think that ecclesiastical institutions will be able to provide it much longer. You can look at the demographic changes, at the money lost both through diminishing donations and lawsuits because of clerical scandals, at the amount of artwork already available as salvage from closed parishes - none of this suggests that ecclesiastical institutions will become great patrons of new sacred art any time soon.

How can the Church be more welcoming to artists? I think that sacred art should have four qualities: it should be traditional and beautiful, as I said already; and it should be real and interesting.

What the clergy and theologians of the Church could do to help artists is to advance an argument for art that has these qualities. They have not advanced this argument much lately, and a good number of them probably don't even believe it.

By "real" I mean that sacred art ought, at least as an ideal, to be made by real human hands or voices. Music sung or played in person is a different thing, and a better thing, than an electronic recording. A picture drawn by hand is qualitatively superior to picture printed by a computer. There is at least a rule on the books that liturgical music needs to be sung or played live, not off of a CD, but even there a lot of fake things are broadly tolerated: bell sound effects played from speakers in a tower, or synthesizers dressed up in casings to look like pipe organs. Visual artists don't even have this sort of rule in place for them. Printing technology - both 2D and 3D - is now so sophisticated that I worry about it displacing human artists, without the clergy or theologians objecting.

I fear that some time soon, one of the great artistic or architectural treasures of Christianity will be ruined - more completely and irreparably than Notre Dame de Paris - and that in response to demands that it be rebuilt exactly as it was before, living artists will dismissed from the task as untrustworthy. Instead, a computer model will be constructed from the photographic record, and everything will be 3D printed in concrete or faux wood. Once that happens, a precedent is set, and living artists and architects thenceforth will compete, most likely at an economic disadvantage, against computers imitating the old masters.

I don’t oppose reproductions themselves; I have digital prints on display in my own home, and I sell digital prints of my own artwork. I listen to recordings of music. I do oppose the idea that these can, in themselves, provide a sufficient experience of art and music. I oppose the idea that sacred art and music can be fostered through attitudes that would have made their existence impossible in the first place.

By "interesting," I mean that art and music should command attention. So many Catholics have gotten it into their minds that the very definition of prayer or worship is "thinking pious thoughts to oneself.” They close their eyes and obsess about whether they can think those pious thoughts through to a conclusion without noticing anything else. With this mindset, art and music are praised as"prayerful" simply for being easy to ignore. Art or music that are particularly excellent are condemned as "distracting.”

This, really, is wrongheaded. Distractions from prayer are foremost interior, the result of our own loud and busy and selfish thoughts. Sacred art or music that draw us out of our own thoughts, that make us notice their beauty, are fulfilling their purpose; they are bringing us closer to the source of all beauty, God.

I can't remember the last time I heard a living priest of theologian say as much.

How can the artistic world be more welcoming to artists of faith? I don't really think that it makes sense to speak of an artistic world as opposed to any other world, at least when it comes to sacred art.

This art is meant to be in churches, or in homes, or in any places where people pray - that is to say, anywhere. It belongs to everyone. I have no objection to seeing my artwork in galleries or museums, but I don't seek out those spaces; I try to make my artwork available to anyone, as directly as possible.

How do you afford housing as an artist? The medium in which I chose to work - small scale ink drawing - does not require a very large working space, and uses no toxic materials or dangerous equipment. So really, all I need is a room in which to work. It doesn't need to be a space outside the home, or away from my kids.

So affording housing as an artist is, for me, the same as affording housing in general. I moved to my current home after my wife and I decided that our family was too large to stay in apartments any more; we have four children, and wanted a yard of our own for them. We wanted to be near Chicago, but everything on the Illinois side of the border was too expensive. It took about six months of house hunting, and one temporary move, before we found what we wanted, and we had to borrow most of the money to buy it. So I don't know that I should be giving out advice, except perhaps to urban artists who are "apartment poor" like I used to be, not to let that situation go on too long.

I advise any artists who are still early enough in their careers not to be wedded to a particular medium to consider how their choice of medium will affect what sort of living space they will need eventually, especially if they hope to have a family. If you want to paint pictures or make prints that require pigments or chemicals too toxic to have around young children or pregnant women, that is something you should be prepared to deal with in advance.

How do you financially support yourself as an artist? My artwork is my livelihood. About half of my income is from commissioned drawing, and about half from print sales, licensing and book royalties. I do teach, write and lecture on occasion, but this is not a significant part of my income. I've never had a residency or a grant, and I do not seek them out.

I've had my own website, www.danielmitsui.com, since maybe 2005, and use this as the primary means of displaying, selling and promoting my work.

What are your top 3 pieces of advice for Catholic artists? In one of my lectures, Heavenly Outlook, I gave three pieces of advice to anyone who want to appreciate or make sacred art, and I will repeat them here:

First, never treat art like data. Second, be guided by holy writ and by tradition itself: liturgical prayer, the writings of the church fathers and the art of the past. Third, do not consider sacred art a completed task. Do not consider any historical artifact to be a supreme model to be imitated without improvement. Please pray for me, and for my family.

#daniel mitsui#hobart#indiana#visual art#artist#catholic#catholic artist#catholic artists#catholic art#art#catholic artist connection

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Independent Study

Reading Notes

1. Stewart, Susan. “Objects of Desire.” On Longing: Narratives of the Miniature, the Gigantic, the Souvenir, the Collection. Duke University Press, 1993, pp.132-169.

We might say that this capacity of objects to serve as traces of authentic experience is, in fact, exemplified by the souvenir (Stewart 135).

We do not need or desire souvenirs of events that are repeatable. Rather we need and desire souvenirs of events that are reportable, events whose materiality has escaped us, events that thereby exist only through the invention of narrative (Stewart 135).

The souvenir speaks to a context of origin through a language of longing, for it is not an object arising out of need or use value; it is an object arising out of the necessarily insatiable demands of nostalgia (Stewart 135).

The souvenir reduces the public, the monumental, and the three-dimensional into the miniature, that which can be enveloped by the body, or into the two-dimensional representation, that which can be appropriated within the privatized view of the individual subject (Stewart 137-138).

Such souvenirs are rarely kept singly; instead they form a compendium which is an autobiography (Stewart 139).

Scrapbooks, memory quilts, photo albums, and baby books all serve as examples.

It is significant that such souvenirs often appropriate certain aspects of the book in general; we might note especially the way in which an exterior of little material value envelops a great “interior significance,” and the way both souvenir and book transcend their particular contexts (Stewart 139).

Because of its connection to biography and its place in constituting the notion of the individual life, the momento becomes emblematic of the worth of that life and of self’s capacity to generate worthiness (Stewart 139).

Although a book may hold little significance to others, it holds great value to the possessor who spent time, money and effort creating it. This is what makes objects sentimental to individuals. Souvenirs move history into private time; once we take the souvenir, we as the individual decide what we do with it. Display it, store it or share it.

The double function of the souvenir is to authenticate a past or otherwise remote experience and, at the same time, to discredit the present (Stewart 139).

The nostalgia of the souvenir plays in the distance between the present and an imagined, prelapsarian experience, experience as it might be “directly lived.” The location of authenticity becomes whatever is distant to the present time and space; hence we can see the souvenir as attached to the antique and the exotic (Stewart 140).

Souvenirs of the mortal body are not so much a nostalgic celebration of the past as they are an erasure of the significance of history (Stewart 140).

Tourism work

Less common tourist items - dish towels/dust cloths

Not intended to serve their original purpose but are fixed to the wall

“Spurious”

The photograph as souvenir is a logical extension of the pressed flower - the preservation of an instant in time through a reduction of physical dimensions

The narration of the photograph will itself become an object of nostalgia

Souvenir moves history into private time

2. Açalya Allmer

Storytelling and memory

Personifying the objects in the museum

Unlike a typical collector; to be proud of the collection he possesses (3)

A catalogue of notional objects which represent Kemal’s love for Fusun

Embed the objects into a narrative

Sensities the reader to the museum’s collection (4)

The museum of innocence is in fact not just a novel, but also a symbol of Pamuk’s passion for collecting

‘Accomplish the renewal of existence through the whole range of childlike modes of acquisitions from touching things to giving them names (5)

‘Tempered mode of sexual perversion’

Collecting objects because they make us remember our good moments

‘For a true collector the whole background of an item adds up to a magic encyclopedia whose quintessence is the fate of his object

The Museum of Innocence should not be considered as an architectural adaptation of the story. (6)

Pamuk wants the objects to represent the story in their own way. If you take these everyday objects at the practical level, the visitor to the museum will be disappointed (6)

The Museum of Innocence is a project that arises not only from Kemal’s commitment to Füsun and his collection of objects, but also from Pamuk’s commitment to his novel. Pamuk, in an interview, calls himself a ‘museum person’ and it seems that there is a lot of Kemal in Pamuk

Wunderkammer - cabinet of curiosities

The Museum of Innocence exemplifies how invented worlds can orient and organise our lives. If we visit Istanbul and go to the Museum of Innocence on a Saturday afternoon to see the objects that ‘Kemal’ collected over the years, we realise how Pamuk is tied to Kemal’s actions and emotions (7)

3. Anthropologist James Clifford offers a critique of a 1984 show at the Museum of Modern Art (MOMA), called '"Primitivism' in 20th Century Art: Affinity of the Tribal and the Modern."

One could encounter tribal objects in a number of locations

MOMA - Primitivism, 20th century art; Affinity of the Tribal and the Modern

Ethnographic specimens

Modernism is thus presented as a search for “informing principles” that transcend culture, politics, and history

Modernist primitivism, with its claims to deeper humanist sympathies and a wider aesthetic sense, goes hand-in-hand with a developed market in tribal art and with definitions of artistic and cultural authenticity that are now widely contested (8)

“We are offered treasures saved from a destructive history, relics of a vanishing world” (9)

In terms of the aesthetic code. Art is art in any museum (12)

Achebe’s image of a “ruin” suggests not the modernist allegory of redemption (a yearning to make things whole, to think archaeologically) (12)

The Maori have allowed their tradition to be exploited as “art” by Western cultural institutions and their corporate sponsors in order to enhance their own international prestige and thus contribute to their current resurgence in New Zealand society (13-14)

They were quickly integrated, recognised as masterpieces, given homes within an anthropological-aesthetic object system (15)

That question the boundaries of art and the art world, an influx of truly indigestible “outside” artifacts (15)

0 notes

Text

notes on "islands of the mind" by john gillis (ch. 7)

Ch. 7: "Worlds of Loss: Islands in the Nineteenth Century" 121: "It is difficult to imagine losing a mountain or a continent, but islands are forever going astray." "Today, despite the fact that the world is now mapped in the minutest detail, searches for "unknown" islands continue." 122: "Our obsession with getting on, with moving ahead, prompts us to draw up the bridges to our past. The measure of an "advanced" society is the degree to which it has left the past behind; modern maturity is equally dependent on the metaphor of growth, leaving behind a series of extinguished earlier selves. Yet precisely because the modern collective and individual sense of self is so reliant on distancing the past, both have become wholly dependent on tangible evidences of what has been lost to validate themselves. Never before has so much been memorialized, reconstructed, and preserved." "The story modern Western civilization has told itself about progress requires that it distance itself from the past in order to reassure itself of its forward movement. As Fritzsche puts it: "While nostalgia takes the past as its mournful subject, it holds it at arm's length. Nostalgia constitutes what it cannot possess and defines itself by its inability to approach its subject, a paradox that is the essence of nostalgia's melancholy." (quote from "Spectors of History: On Nostalgia, Exile, and modernity" by Peter Fritzsche, in American Historical Review, Dec. 2001) 123: "The modern sense of the passing of time depends on a series of bounded, discrete locations--home, school, workplace, retirement communities, cemeteries--which keep each age and era separate from another. In effect, the modern sense of self depends on the spatialization of the past, islanding it by keeping it neatly bounded and distant. Not all spaces are amenable to this function. Open, contiguous spaces do not readily maintain the aura of historicity. Urban life offers few refuges for the past. The period styles of suburbs offer only the illusion of tradition, propelling our quest for the bygone ever farther afield. Remote places seem so much better suited to the preservation of the past, and none better than islands, which have become, often despite themselves, a prime repository of pastness." "Community, something that modernity had torn apart, seems to have survived only on islands." "Once again islands were becoming symbols of something that had little to do with their own realities." "Indeed, over the course of the nineteenth century, the pace of change on most islands was as great, if not greater, than that in many parts of the mainlands. But this did not prevent them from being viewed as anachronisms, mired in the past, appearing as was the fate of the Hebrides, "as if in a rear-view mirror."" (reference here to The Western Isles Today by Judith Ennow, 1980) "Modern nostalgia is the product of the profound sense of historical rupture that came with the revolutions of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. At this critical moment, the past became a foreign country, all the more precious because it seemed so remote and inaccessible." 124: "Islands became important sites for the appreciation of the quaint and the primitive. If islands no longer provided a vision of the future, they were nevertheless ideal venues for time travel to bygone eras. They came to be associated with the infancy of mankind and with childhood itself. Reconfigured as places of origin, islands were no longer treated as gateways to the future but as access to a mythic past. Once the favored destination of male adventurers who left women and children at home, islands became the resort of families, identified with domestic pursuits and with home itself. What had once provided space for masculinist dreams of escape now nurtured fantasies of return to the womb." 125: "Mainlanders were intent on finding on islands peoples who were untouched by the rapid changes that they themselves were experiencing. Yet islands were anything but exempt from modernity's ceaseless creative/destructive

forces, arising first from commercial expansion and later from the industrial revolution." 126: "As genteel mainlanders came to be more frequent visitors to islands, the result was not a diminution but a magnification of differences between them and islanders. Even as physical isolation was being overcome, the illusion of insularity was being cultivated for the benefit of the newly developed tourist industry." 131: "Islands had come to be seen by mainlanders as living museums where what had been sacrificed to modernity elsewhere miraculously survived in a purer, more authentic form."

133: regarding the Hebrides: "Islanders had come to live in a time warp not of their own making. They saw themselves through the eyes of outsiders who were bent on preserving crofting as tradition no matter how recent its origins. In many instances it was the visitors who stood in the way of sensible changes, conserving outmoded ways that the islanders themselves would rather have turned their backs on."

136: regarding Inishbofen: "Islanders preferred canned food to fresh, ignoring the harvest of berries and shellfish that so delighted the tourists. For the people of Inishbofen "the industriousness of years past is now a symbol of poverty, humiliation." They told Tall that they would not eat mussels because it reminded them of famine times when shellfish was all that was to be had on the island." (reference here to The Island of the White Cow: Memories of an Irish Island by Deborah Tall, 1986)

138: "By the middle of the nineteenth century, Britain had lost nearly all the original wild places that the first generations of romantics had so glored in. ... Lacking wild lands, the British chose this moment to make the sea their wilderness. It was then that Englishmen began to return to the sea, not as an occupation, but as avocation. It became for them their last frontier, the place where, in small sailing boats, they would test themselves against the elements, proving their manhood to themselves and to the women waiting on shore. "England's only untamed wilderness, where men might still be small and alone in the vastness of Creation, was the sea," writes Raban. "To go to sea was to escape from the city and the machine." (reference here to two books by Jonathan Raban: Coasting (1986) and The Oxford Book of the Sea (1992))

138-139: "Though the sea offered the ultimate escape from stifling civilization, the great adventure for Victorian men seeking to prove their masculinity in an increasingly effeminized domesticated world, the island was a retreat where they could preserve something of their innocence in an otherwise cruel and unforgiving world. There were still plenty of Crusoes, men who viewed islands as their own private kingdoms and a projection of their own inflated egos, but there were also males like Pastor Wyss, the author of Swiss Family Robinson, for whom the island was the setting for family romance, where the instinct for adventure gave way to that yearning for security and comfort that was also a feature of the Victorian era. On land, time moved relentlessly forward, but on the island it moved backward to a more innocent age, toward the beginnings of the human species or to the childhood of the individual. As the fantasy of returning to the innocence of childhood became more powerful among middle-class men in the nineteenth century, the appeal of Crusoe's island gave way to that of Swiss Family Robinson and finally to that of Peter Pan. Ad as islands grew less valuable politically and economically, their reputation for happy domesticity grew proportionally. Islands became ever more associated with the kind of virtuous life that was becoming harder to come by on the mainlands. Occupying a place between the overcivilized land and the wildness of sea, islands were increasingly attractive to a Western middle class yearning for personal freedom but not at the expense of moral respectability. Islands came to be seen as the preeminent "happy Prelapsarian Place." (reference here to The Echafed Flood, or, The Romantic Iconograpjy of the Sea by W.H. Auden, 1950)

139: "By the twentieth century, islands ceased to be thought of as destinations and became places of return, fixed points where an increasingly mobile mainland urban population eager for seasonal respite could savor a sense of stability and continuity."

139-140: "Already in the nineteenth century, people on the mainland were experiencing the erasure of place produced by increased mobility and speed of communication. The resulting sense of rootlessness triggered the uniquely modern quest for place in a placeless world, for home in the vast, featureless landscapes of urban industrial society. The search was not just for residence but for that elusive sense of being at home in the world, as much a mental as a physical endeavor, more likely to be achieved at a distance in the absense of that which was called home. In a world of temporal and spatial movement, where for many there was no long a place to return to, home became a state of mind, "something to be taken along wherever one decamps."" (reference here to the Introduction to Migrants of Identity: Perceptions of Home in a World of Movement, eds. Nigel Rappaport and Andrew Dawson, 1998) (i would also add that the movement of populations & widespead dislocation is also related to and created by the needs of capital.)

140: ""Under conditions of modernity, place becomes increasingly phantasmagoric," writes Anthony Giddens. (reference here to The Consequences of Modernity by Anthony Giddens, 1990) Home became detached from residence, less a physical location than a mental construct, a think of dreams as well as memories, no less real even if it is rarely, sometimes never, actually inhabited."

"Over time the dream house and memory palace moved out, transferring ever farther afield to weekend and summer places. These became locations of "the lost origin and the future dream, both vanishing points where we imagine ourselves at peace, surrounded by comfort and harmony." (reference here to Sex and Real Estate: Why We Love Houses by Marjorie Garber, 2000) It provided easier to animate meaningful, habitable worlds at a distance, with the result that for those who can afford them, the dearest homeplaces are often those they visited only occasionally, sometimes never returned to, however frequently they are visited mentally. Island houses, rarely occupied year-round, were already becoming in the late nineteenth century the quintessential family places where generations, scattered throughout the mainlands, could share time and space, if only occasionally. In Amy Cross's view, the summer place is "not real estate, it is more a state of mind that can be packed and moved to any woods or seaside. And many of us travel through life with a memory of a perfect place waiting for our return." (reference here to The Summer House: A Tradition of Leisure by Amy Willard Cross, 1992)

141: "Modern maturity has been particularly demanding on men, requiring that they distance themselves from domestic, childish things, producing in them a yearning for childhood that has characterized middle-class male culture ever since. In the resulting quest for childhood lost, summer islands became the favored place for retrospection and recuperation. The isles allowed a brief sojourn in childishness that did not threaten the adulthood associated with mainland existence."

0 notes

Text

10 Artists Who Unpacked the Symbolism of the Four Seasons

They say the only constant is change, and there may be no more reliable change than the advance of the seasons. A universal reminder of the passage of time and life’s cyclical nature, the four seasons have long been a favorite allegorical vessel for artists. Ancient Greek sculptures personify them, medieval European illustrations moralize virtuous and vicious behavior, and Edo-period Japanese prints render seasonal shifts in fashion and ritual. As with many formally and thematically conventional art historical subjects, artists have been tweaking, revising, and upending the theme for centuries.

From artists who imbue the subject’s broad allegorical meanings with deeply personal or pointedly political messages to others who update the tried-and-true formula through contemporary mediums like photography and video, the following 10 examples attest to the polyvalent power of the seasons in art history: ebullient as spring, irresistible as summer, colorful as fall, and cool as winter.

Giuseppe Arcimboldo’s cornucopic portraits

Giuseppe Arcimboldo, Winter, 1573. Photo via Wikimedia Commons.

Giuseppe Arcimboldo, Autumn, 1573. Photo via Wikimedia Commons.

The Milanese master Giuseppe Arcimboldo cemented his place in art history when, in the mid-16th century, he managed to fuse two of the most popular painting genres: portraiture and still life. His elaborate paintings of archetypes and allegorical figures made up of thematically appropriate objects—from a librarian made of books to a chef composed of food and cookware—remain as popular today as they were in his lifetime.

In 1563, as a court painter to soon-to-be Holy Roman Emperor Maximilian II, Arcimboldo offered his patron a series of figural paintings personifying the four seasons that he had created earlier in the decade. Of the originals, one has never been found, and only Winter and Summer have survived (they belong to the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna), but Maximilian II liked them so much that he ordered a second set from Arcimboldo in 1573 as a gift for Augustus, the Elector of Saxony.

Giuseppe Arcimboldo, Summer, 1573. Photo via Wikimedia Commons.

Giuseppe Arcimboldo, Spring, 1573. Photo via Wikimedia Commons.

The second set remains intact and belongs to the Louvre. It includes a bearded figure for autumn made up of root vegetables, grapes, and apples; a grimacing winter formed chiefly from a knotty tree trunk with branches for hair; a blossoming spring figure with a leafy torso and flowery coif; and a grinning summer with ripe vegetables and fruit making up its face and hair, along with a shimmering wheat collar. (As a testament to the series’s enduring popularity, American artist Philip Haas made four monumental sculptures based on the paintings in 2009.)

Arcimboldo returned to the subject of the seasons later in life, when he’d moved back to Milan. About three years before his death, he created Four Seasons in One Head (ca. 1590), a fantastical and dark three-quarter portrait of an aged tree figure with a pockmarked and somber face. That painting, which invites ruminations on the passage of the seasons and the effects of time on the body and mind, was not publicly exhibited until 2007, and was subsequently acquired by the National Gallery of Art.

Nicolas Poussin’s biblical seasons

Nicolas Poussin, Autumn (The Spies with the Grapes of the Promised Land), 1660-64. Photo via Wikimedia Commons.

Another artist who found poignancy in the cycle of seasons late in life was Nicolas Poussin, whose last set of works stages four Old Testament stories in four different seasons and times of day. The French artist painted them for the Duc de Richelieu, great-nephew of the famous Cardinal Richelieu, between 1660 and 1664. The following year, the Duc promptly lost them (along with nine other Poussin paintings) to King Louis XIV in a tennis match.

Nicolas Poussin, Winter (The Deluge), 1660-64. Photo via Wikimedia Commons.

Nicolas Poussin, Spring, 1660-64. Photo via Wikimedia Commons.

Nicolas Poussin, Summer, or Ruth and Boaz, 1660-64. Photo via Wikimedia Commons.

“The Four Seasons” (1660–64) now hang together at the Louvre. The dramatic narrative sequence begins with Spring (The Earthly Paradise), a pre-dawn, prelapsarian scene of Adam and Eve in a verdant wilderness, and concludes with the stormy and apocalyptic nighttime depiction of Noah’s Ark, Winter (The Flood). In between are much brighter daytime tableaux. An image showing a summertime grain harvest recounts the parable of Boaz and Ruth, and an autumnal, apple-filled landscape serves as the stage for a scene in the Book of Numbers in which two Israelite spies carry giant grapes from the Promised Land on a pole. The series powerfully contrasts the cyclical nature of the seasons with the finality of the biblical narrative.

Rosalba Carriera’s sensual allegories

Rosalba Carriera, Spring, mid-1720s. Courtesy of The Hermitage, St. Petersburg.

Rosalba Carriera, Winter, mid-1720s. Courtesy of The Hermitage, St. Petersburg.

Venetian artist Rosalba Carriera began honing her craft by painting portrait miniatures on snuffbox lids, even incorporating ivory into her tiny compositions. Subsequently, she pioneered the use of pastels for serious portraiture (pastels were previously used primarily for preparatory sketches), which earned her a good deal of fame and enabled her to study in Rome and then travel to Paris, where she painted the young King Louis XV.

Among the many portraits and allegorical figures she depicted in the flagrantly frilly and overtly sexual style that would come to be known as Rococo was a suite of four risqué portraits of women. Each represents a different season, but is dressed as if it were the hottest summer day: A springtime figure wears flowers in her hair, while a scantily-clad sitter representing winter dons a fur shawl.

Utagawa Kunisada’s ukiyo-e narratives

Utagawa Kunisada I (Toyokuni III), Snow in the Palace Garden, from the series “The Four Seasons,” 1847-52. Courtesy of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

Today, Katsushika Hokusai might be the best-known printmaker from Japan’s Edo period, but at the time, no artist was more famous or prolific than Utagawa Kunisada. Among his many ukiyo-e woodblock prints, which were bestsellers in Japan in the first half of the 19th century, is the series “Shiki no uchi” (“Four Seasons”)—40 of which are in the collection of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

Ornate scenes rich with narrative detail include portrayals of figures enjoying a casual, lived relationship with the environment, as well as allegorical depictions of the seasons. In one print, courtship rituals play out between couples dressed in exquisitely patterned robes as they stroll through the snowy imperial palace. In another, barefoot figures playfully seek shelter during a warm spring shower.

Marc Chagall’s sweeping vision of Chicago

Detail of Marc Chagall, The Four Seasons, at the Exelon Plaza, Chicago, 1974. Photo by UGArdener, via Flickr.

Amid the streamlined geometry of Chicago’s Chase Tower Plaza stands a startling and fanciful sight: Marc Chagall’s freestanding mosaic mural, The Four Seasons (1974). Made up of inlaid chips in 250 different hues, the sprawling mosaic depicts six visions of Chicago, including references to its iconic modernist architecture. Indeed, Chicago’s skyline had changed so much between the artist’s previous visit to the city and the mosaic’s installation 30 years later that he made several last-minute changes, modifying buildings and incorporating fragments of Chicago brick into the mosaic.

The enormous work features a mix of everyday and supernatural scenes, with hybrid flying creatures soaring above children, musicians, dancers, lovers, and more. Though the mosaic doesn’t make specific reference to Chicago’s punishing winters, they left it worse for wear, and in 1994, it underwent an extensive restoration, with a protective canopy built over it.

Jennifer Bartlett’s skeletons for every season

Jennifer Bartlett, Summer, 1990. Courtesy of the artist and Locks Gallery.

Jennifer Bartlett, Fall, 1990. Courtesy of the artist and Locks Gallery.

Though she is best known for grid-based paintings that marry elements of figuration and abstraction, Jennifer Bartlett’s print series “The Four Seasons” (1990–93) is bursting with figurative imagery. Each of the four screenprints finds a human skeleton set in a grassy landscape and surrounded by animals, dishes, handprints, dominoes, playing cards, and swaths of decorative patterns.

Jennifer Bartlett, Winter, 1990. Courtesy of the artist and Locks Gallery.

Jennifer Bartlett, Spring, 1990. Courtesy of the artist and Locks Gallery.

Whereas the cycle of nature—life ends in death, which, in turn, gives way to new life—is a staple theme in historical depictions of the four seasons, Bartlett subverts the formula by making death the focus throughout. Her inclusion of dominoes and cards also adds an element of chance amid the predictable sequencing, adding to the enigmatic nature of the series.

Liu Dahong’s cyclical political critique

FOUR SEASONS, 2006. Liu Dahong Aura Gallery

FOUR SEASONS, 2006. Liu Dahong Aura Gallery

While some artists have rather subtly layered political or philosophical messages into their riffs on the four seasons motif, there’s nothing subtle about Liu Dahong’s print series “Four Seasons” (2006), which takes up his favorite subject: the Cultural Revolution. The outrageous images feature Mao Zedong, Zhou Enlai, and other Communist Party leaders in dramatic scenes that borrow from the history of Chinese painting, with nods to propaganda posters, social realism, comics, textbooks, and other sources. The satirical images posit these Communist authorities as deities surrounded by faithful followers—including some who seem to be freezing to death in the wintry scene.

FOUR SEASONS, 2006. Liu Dahong Aura Gallery

FOUR SEASONS, 2006. Liu Dahong Aura Gallery

“The past is a resource you use to arm yourself,” Liu said in a 2016 interview. “The West is very good at that, but not China, where there isn’t enough discussion about the past in general and nobody ever touches the Cultural Revolution.” His take on the four seasons suggests that history, like nature, can be cyclical—especially when we don’t learn from the mistakes of the past.

Wendy Red Star decolonizes nature

Spring (The Four Seasons series), 2006. Wendy Red Star Haw Contemporary

In most instances, artistic renderings of the seasons play on parallels between the natural world and human behavior, but artist Wendy Red Star took up the motif specifically to subvert this trope. Her 2006 photo series “The Four Seasons” lampoons the essentializing Western characterization of Native Americans as being inherently more connected to nature. In the images, she sits in traditional Crow dress in front of studio backdrops of dramatic landscapes, surrounded by plastic and cardboard props.

Fall (The Four Seasons series), 2006. Wendy Red Star Haw Contemporary

Winter (The Four Season series), 2006. Wendy Red Star Haw Contemporary

Indian Summer (The Four Seasons series), 2006. Wendy Red Star Haw Contemporary

Though she considers the series her “gate opener,” the images were not well-received when she first showed them as a student in UCLA’s MFA program. “I was told, ‘These works will never show, they’re not professional enough,���” she recounted to Cowboys and Indians. “I realize now that [my instructors] were adept with the privileged language of theory and abstraction. But when it came to identity-based art, they didn’t know how to talk about things like race and cultural history.” Nine years later, the series was included in the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s landmark 2015 exhibition “The Plains Indians: Artists of Earth and Sky.”

David Hockney’s travels through time

The seasons have been a palpable force in David Hockney’s work for decades—or, in the case of his portraits of Southern California collectors in their sun-splashed homes, the lack of seasons. His best-known landscape paintings capture views of the English countryside teaming with lush plant life in the spring and summer, sprinkled with rain or strewn with dead leaves in the fall, and blanketed with snow in the winter.

In addition to a deluge of iPad drawings, Hockney’s recent embrace of technology has resulted in a far more elaborate and ambitious take on the passing seasons: the 36-screen digital video piece The four seasons, Woldgate Woods (Spring 2011, Summer 2010, Autumn 2010, Winter 2010), currently on view at Richard Gray Gallery. Playing across four nine-screen grids, the piece is a video collage of sorts that leads the viewer down country roads in the titular Yorkshire woods as the seasons pass, transforming the landscape.

Sibyl Kempson performs the solstice

Performance of Sibyl Kempson, 12 Shouts to the Ten Forgotten Heavens, at the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, Spring Equinox, 2016. Photo © Paula Court. Courtesy of the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York.

For some, equinox and solstice parties are part of a hippie phase or an occasional burst of exuberance with a granola crunch. For the artist Sibyl Kempson, they’re a generative wellspring. For nearly three years, the director, playwright, and performer has marked every equinox and solstice with a performance at the Whitney Museum of American Art.

Kempson developed the specially commissioned series, entitled “12 Shouts to the Ten Forgotten Heavens,” in collaboration with Thomas Riccio, a scholar of ritual, shamanism, and indigenous performance. Past iterations, performed with her theater company 7 Daughters of Eve Thtr. & Perf. Co. in and around the Whitney, have included everything from a broom-sweeping ceremony and a male beauty contest to a ladies-only rosé tasting, the ritual burning of plants and herbs, and what she described as a “bad translation” of August Strindberg’s Miss Julie.

Kempson sees the project—which continues this Saturday and concludes in December—as an opportunity to “observe [seasonal] patterns that we wouldn’t notice otherwise,” she told Art in America. “A lot of the beauty of a city partly has to do with nature.”

from Artsy News

0 notes

Photo

“Deana Lawson’s Kingdom of Restored Glory” by Zadie Smith

Imagine a goddess. Envision a queen. Her skin is dark, her hair is black. Anointed with Jergens lotion, she possesses a spectacular beauty. Around her lovely wrist winds a simple silver band, like two rivers meeting at a delta. Her curves are ideal, her eyes narrowed and severe; the fingers of her right hand signal an army, prepared to follow wherever she leads. Is this the goddess of fertility? Of wisdom? War? No doubt she’s divine—we have only to look at her to see that. Yet what is a goddess doing here, before these thin net curtains? What relation can she possibly have to that cheap metal radiator, the chipped baseboards, the wonky plastic blinds? Where is her kingdom, her palace, her worshippers? Has there been some kind of mistake?

Examining Deana Lawson’s “Sharon” (2007), a black viewer may find the confusion of her earliest days reënacted. Before you’d heard of slavery and colonialism, of capitalism and subjection, of islands and mainlands, of cities and ghettos, when all you had to orient yourself was what was visually available to you; that is, what was in front of your eyes. And what a strange sight confronts the black child! The world seems upside down and back to front. For your own eyes tell you that your people, like all people, are marvellous. That they are—like all human beings—beautiful, creative, godlike. Yet, as a child, you couldn’t find many of your gods on the television or in books; they were rarely rendered in oil, encountered on the cinema screen or in the pages of your children’s Bible. Sometimes, in old reruns, you might spot people painted up, supposedly to look like your gods—with their skin blackened and their lips huge and red—but the wise black child pushed such toxic, secondary images to the back of her mind. Instead, she placed her trust in reality. But here, too, she found her gods walking the neighborhood unnoticed and unworshipped. Many of them appeared to occupy lowly positions on a ladder whose existence she was only just beginning to discern. There were, for example, many low-wage gods behind the counters at the fast-food joints, and mostly gods seemed to shine shoes and clean floors, and too many menial tasks altogether appeared to fall only to them. Passing the newsstand, she might receive her first discomforting glimpse of the fact that the jail cells were disproportionately filled with gods, while in the corridors of power they rarely set a foot. Only every now and then did something make sense: a god was recognized. There’s little Michael Jackson and grand Toni Morrison, and, look, that’s James Baldwin growing old in France, and beautiful Carl Lewis, faster than Hermes himself. The kinds of gods so great even the blind can see them. But back at street level? Too many gods barely getting by, or crowded into substandard schools and crumbling high-rise towers, or harassed by police intent on clearing Olympus of every deity we have. And, for a long, innocent moment, everything about this arrangement will seem surreal to the black child, distorted, like a message that has somehow been garbled in the delivery. Then language arrives, and with language history, and with history the Fall.

Deana Lawson’s work is prelapsarian—it comes before the Fall. Her people seem to occupy a higher plane, a kingdom of restored glory, in which diaspora gods can be found wherever you look: Brownsville, Kingston, Port-au-Prince, Addis Ababa. Typically, she photographs her subjects semi-nude or naked, and in cramped domestic spaces, yet they rarely look either vulnerable or confined. (“When I’m going out to make work,” Lawson has said, “usually I’m choosing people that come from a lower- or working-class situation. Like, I’m choosing people around the neighborhood.”) Outside a Lawson portrait you might be working three jobs, just keeping your head above water, struggling. But inside her frame you are beautiful, imperious, unbroken, unfallen.

Born in 1979 and raised in prelapsarian Rochester, New York—well before the collapse of Kodak—Lawson arrived in the world with a matchless origin story: her grandmother cleaned the home of George Eastman, the founder of the Kodak empire. (In what she has called the “mythology” of her family, her grandmother overheard Eastman ask his nurse where his heart was situated, the morning before he shot himself through the chest.) Kodak was foundational in practical ways, too. When Lawson’s mother applied for a factory job there, the man who interviewed her felt that she was more suited to office work, and so instead she landed an administrative job, which she kept for the next thirty-nine years. The Lawsons thus found themselves in an interesting social position: “middle-class-aspiring,” living on the working-class East Side of Rochester but not on blue-collar salaries, and with a father, a manager at Xerox, who, as Lawson has described him, was an avid family photographer, daily documenting Deana and her identical twin, Dana, in times both happy and sad.

On one memorable occasion, he took a picture of the twins on the stoop together, Dana with a recently broken thumb and Deana holding her sister’s cast in her own hand: “We’re both dressed exactly alike. We both have the same frowns on our head. That picture kind of pierced me. I think that was, like, the beginning of identifying with another person, or trying to understand another human being’s pain, in a way, through looking at myself.” This self-in-other experience intensified years later, when Lawson’s sister, then seriously ill with multiple sclerosis, permanently dropped out of Penn State (the twins had arrived together), leaving Lawson with the weight of her family’s expectations on her shoulders. (“When my sister got sick, I had to win for both of us.”) It was in college that Lawson wriggled out of her business major and started taking photographs. From the outset, they were “staged”—like a family portrait, only more so—for she always liked to choose the people, the setting, the clothes, and the pose.

As Cindy Sherman has amply demonstrated, the most obvious route for a photographer with these anti-vérité instincts might be the self-portrait, but in the bulk of her work Lawson appears only in relation: she is the unseen person whom all these striking-looking people are looking at. How she manages to create this relation is a fascinating question. In person, Lawson—a striking woman in her own right—has a soft-spoken, rather shy manner that seems to belie the fearlessness and will it must surely require to travel to far-flung places, talk your way into strangers’ homes, and then get them to pose precisely as you want. (My own response upon seeing her work for the first time was: How do you convince Jamaicans to take their clothes off?) To do so, you would need to know how to listen, but also how to ask the right question, and at the right moment. You’d have to be self-effacing and yet forceful enough to pursue significant leads. With her ethnographic skills, and in her choice of destinations, Lawson might remind us of Zora Neale Hurston, whose idiosyncratic 1938 anthropological study of voodoo and folk practices in the diaspora, “Tell My Horse,” traverses some of the same territory to which Lawson has been drawn—Jamaica, Haiti—and is a text that Lawson herself has cited as an early inspiration.

Like Lawson, Hurston was constitutionally attracted to the marginalized, the obscure, the ostensibly lowly. And, like Hurston, Lawson’s fullest subject is the diaspora itself. Looking at “Otisha” (2013), in which a young, naked Jamaican woman poses like a piece of West African statuary among the many leatherette couches that fill a cramped and overdecorated living room in Kingston, I thought of the Pocomania (or Pukkumina) cult that Hurston encountered in Jamaica, and which she heard a local man define as the compulsion to make “something out of nothing.” The diaspora is a broad and various thing, but one rich vein running through it has surely been the historical, economic, and personal necessity of making “something out of nothing.” In an illuminating conversation that Lawson had with Arthur Jafa, a Los Angeles-based artist and filmmaker, Jafa sketches this journey from nothing to something in miniature:

“Initially, when Africans step off those ships they have the same battery of cultural verification and affirmation that most people have. But a defining experience for black people during slavery is the separating of folks from their children, from their partners, from their families. So, very quickly, Africans become a new kind of people, black people. We create culture in free fall, but we also create kinship in free fall.”

Jafa, too, is a diaspora explorer. (His 2017 video installation at the Museum of Contemporary Art, in L.A., “Love Is the Message, The Message Is Death,” was set to Kanye West’s sublime gospel-inflected “Ultralight Beam,” and used a huge variety of found film footage to create a phantasmagoria of black images through history.) In their conversation, which will be published later this year in “Deana Lawson: An Aperture Monograph,” Lawson and Jafa declare themselves profoundly interested in this new kind of people, a concern that never aspires to a sociological neutrality but, instead, pulses with love. Black people are not conceived as victims, social problems, or exotics but, rather, as what Lawson calls “creative, godlike beings” who do not “know how miraculous we are.” In her work, she tells Jafa, she wants “to try to locate the magnificent and have it come through in the picture.” In response, Jafa notes, “It’s like black people are inherently scarred by our circumstances, and you’re trying to take photographs of them that look past that, like an X-ray looks past surface scars.”

Which is not to say that the surface scars pass unrecorded in Lawson’s photographs. Circumstances are in no way hidden or removed from the shot; nothing is tidied up or away, and everything is included. Dirty laundry is aired in public (and appears on the floor). Half-painted walls, faulty wiring, sheetless mattresses, cardboard boxes filled with old-format technology, beat-up couches, frayed rugs, curling tiles, broken blinds. (It’s instructive to contrast Lawson’s staged portraits of low-income black folk with the young Californian photographer Buck Ellison’s staged portraits of wealthy white folk, replete with the discreet symbols of wealth: wood panelling, cashmere sweaters, silk shirts, linen pants, polished chrome kitchen-cabinet handles, crystal tumblers.) That these circumstances should prove so similar—from New York to Jamaica, from Haiti to the Democratic Republic of the Congo—carries its own political message. But the repetition also takes on a mystical cast, as we note visual leitmotifs and symbols that seem to reoccur across time, space, and cultures. Paragraphs could be written on Lawson’s curtains alone: cheap curtains, net curtains, curtains taped up—or else hanging from shower rings—curtains torn, faded, thin, permeable. Curtains, like doors, are an attempt to mark off space from the outside world: they create a home for the family, a sanctuary for a people, or they may simply describe the borders of a private realm. In these photographs, though, borders are fragile, penetrable, thin as gauze. And yet everywhere there is impregnable defiance—and aspiration. There is “kinship in free fall.”

In “Living Room” (2015), taken in Brownsville, Brooklyn, all the scars are visible: the taped-up curtain, the boxes and laundry, the piled-up DVDs, that damn metal radiator. At its center pose a queen and her consort. He’s on a chair, topless, while she stands unclothed behind him. They are physically beautiful—he in his early twenties, she perhaps a little older—and seem to have about them that potent mix of mutual ownership and dependence, mutual dominance and submission, that has existed between queens and their male kin from time immemorial. But this is only speculation. The couple keep their counsel. Despite being on display, like objects, and partially exposed—like their ancestors on the auction block—they maintain a fierce privacy, bordered on all sides. They are exposed but well defended: salon-fresh hair, with the edges perfect; a flash of gold in her ear; his best bluejeans; her nails on point. Self-mastery in the midst of chaos. And the way they look at you! A gaze so intense that it’s the viewer who ends up feeling naked.

When you create kinship in free fall, you may grab at certain items on the fly. The similarity between these items constitutes its own realm of interest. How often we find—especially in the more comfortable homes—luxurious sateen in brown and gold, heavy brown wood, silver jewelry, fabrics of dark green and dark red, tiles and wallpaper intricately patterned in geometric form. (I am describing my own mother’s living room as surely as any Lawson has photographed.) What deep satisfaction, then, to stand in front of “Kingdom Come” (2014), in which two young Ethiopians in Addis Ababa, a boy and a girl, stand ramrod straight, staring out at us, dressed in the Coptic-like finery of their church. Their gowns are a dark-red velvet, threaded with silver embroidery; the walls behind them are deep red, too, and panelled in dark wood; gold crosses hang behind them. In such an image, you find yourself able to track the aesthetic roots of so much of what Lawson has shown us in diasporic living rooms worldwide: the red and the gold, the geometric patterns, the heavy wood, and that ubiquitous silver bling in which, elsewhere, Lawson photographs a bedazzled New Yorker, “Joanette” (2013), who has stripped to the waist, the better to highlight her silver bangles, her silver hoops, her silver rings. Kinship in free fall, yes, but still connected, however tenuously, to the thick braid of our African heritage, cut off at the root so long ago.

Sometimes, as in a picture like “Mama Goma” (2014), taken in Gemena, in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, that heritage feels close at hand. A young, heavily pregnant woman stands in a cheap-looking shiny blue dress, meant to imitate the finest satin, with a large hole cut in the middle from which her bump protrudes. Her palms face upward, like someone about to begin a ritual or ceremony. Behind her, sprays of cheap tinsel are pinned to the wall; before her, a silver spoon sits on a table like an offering. The remnants of ancient faiths and previous glories touch the edges of the frame; echoes of the Vili people of the Kingdom of Loango, maybe, who traded their copper, finely carved objets d’art, and luxurious fabrics with the people of Holland, a historical memory that is here transmuted—but somehow not reduced—into a tablecloth patterned with flowers and a Dutch windmill that turns no more. In “Hotel Oloffson Storage Room” (2015), a naked woman, perhaps an employee of the hotel in Port-au-Prince, Haiti, perches on the edge of a discarded bed, surrounded by old mattresses, old chair cushions, and old hotel art. These simple paintings have been left half-forgotten in the lowliest corner of a tourist spot—one is of trees, the other of three mystical-looking owls—but in their humble way they each make reference to Haiti’s storied art factions, the Jacmel school (dominated by landscape art) and the Saint-Soleil school (incorporating voodoo symbolism). Meanwhile, on the door hangs an amateurish bust of Jean-Jacques Dessalines, Haiti’s revolutionary general. And in all this décor—in the cushion covers and the bedspread, the walls and the art itself—that red, green, and gold persist, framing our mysterious nude and, like her, retaining an innate magnificence.

You make something out of nothing. You borrow, steal, adapt. Sometimes, in Lawson, this adaptation involves direct quotation. (Her “Three Women,” 2013, which poses naked girls standing in Beyoncé-like formation, recalls Albert Arthur Allen’s naked chorus lines of the nineteen-twenties; in “Ashanti,” 2011, a nude on a sheetless mattress in a grim, bare room assumes the position of the figure in Ingres’s “Grande Odalisque.”) More often, the referents seem to come from intimate experience. I’ll bet there are diaspora folk stretching from London to Kingston to Detroit who will recognize, as Lawson does, how many couches can be squeezed into a space that cannot really accommodate that many couches, and, moreover, how one couch in particular will be a matter of special pride, and therefore covered with plastic for its own protection.

This bold visual recognition of rarely acknowledged commonalities is a great source of pleasure in Lawson’s work. One of the things many people in the diaspora have shared—unavoidably—is the experience of poverty, but Lawson’s work suggests other, deeper vectors that may also connect us: certain gestures and interpersonal attitudes, strategies of escape, modes of defense or display, pleasures and fears, aesthetics, superstitions, and, perhaps most significant, shared fantasies. First among these is an idealized vision of Africa. Of course, Africa has an independent reality, made up of fifty-four separate states, but Lawson isn’t trying to capture that reality any more than she is photographing Detroit when she sets up her camera in that city. Naturalism is never the intention. Everything has an otherworldly aura, each space is both the particular and the universal, and each person at once an individual and a symbol, an archetype, an avatar. “Africa,” in Lawson’s photographs, is unabashedly the site where diasporic longing, fantasy, and sentiment—after much journeying and seeking—finally converge and are fulfilled.

When I look at Lawson’s women, for example, this sentimental instinct in me grows particularly strong. I see Nicole—“Nicole” (2016)—a young mother lounging provocatively on her own rug, her kid’s toys piled up behind her, and up surge the catchphrases of the day: slay, queen; you go, girl; you get yours; and so on. But a picture like “Wanda and Daughters” (2009) defies such easy sloganeering. Wanda, in her mid-forties, is resting against a tree, while her two daughters rest on her. They are in the midst of nature but are dressed in their city best: gold hoops and silver rings for Wanda, perfectly braided hair with many-colored bows for her girls. Wanda has a face like thunder: I dare you to mess with her. Easy to think her a queen, or, if you prefer, an African lioness, protecting her cubs. But you can also read this photograph sequentially rather than sentimentally, moving from face to face, and find a more ambivalent story. Wanda’s fierce gaze tells us that she has sampled the tree of knowledge, that she knows the ways of the world. She’s known for a long time. But her melancholy firstborn is only just discovering how things are, and her younger daughter, with her beaming smile, is still (happily!) in that Eden of innocence in which Lawson has pointedly framed the three of them. Which raises the question: When we call black women queens or lionesses, or when we call Asian mothers tigers—or any of the other colorful terms we conjure up to describe minority women fighting the daily battles of their lives—what are we doing? We come to praise. But, at the same time, don’t we bury—and implicitly sanction—the idea that a fierceness like Wanda’s is the bare minimum needed to raise a black family? I’m again reminded of the ladies in Buck Ellison’s pictures: languid, relaxed, sometimes a little bored, at worst a little impatient for the camera to go click. They have not the slightest touch of fierceness about them. But, then, they have no need of it.

In the history of photography that has concerned itself with Africa and its diaspora, the concept of the portal has been central. In a newspaper, say, a photograph of a black subject is usually conceived as a window onto another world. Even the most well-meaning journalistic images of black life have the intention of enabling a passage, from the First World to the Third, for example, or from one side of the railway tracks to the other. It might be impossible for a black photographer in a largely white art world ever to wholly divest herself of this way of seeing, but in Lawson’s “Portal” (2017) we come as close as I can imagine. What are we looking at? A ripped hole in a couch. That’s all: no human figures, no other context. Just a hole in the kind of couch with which Lawson has made us, by now, very familiar. After staring at it awhile, you might notice that it is almost Africa-shaped, but what you see initially is its magical properties. Like the voodoo practitioners Zora Neale Hurston met in Haiti, Lawson has the rare capacity of being able to take an everyday domestic object and connect it to the spiritual realm. Her work does not show us “how the other half lives.” Rather, it opens up a portal between the everyday and the sacred, between our finite lives and our long cultural and racial histories, between a person and a people. “Portal” presents, in abstract, what Lawson is doing in every other photograph:

“I feel a lot of the figures that I use, I want them to be like a pivotal point, or like a vehicle or a vessel for something else. Diane Arbus was always keen on this idea of what the photograph is and what it does. What you see in the photograph is one thing; the specifics or what it references or what it’s symbolic of is greater than that. She said the subject is always more complex than the picture.”

What you see is not what you get. We are more than can be seen. We are here and elsewhere. Some of Lawson’s portals appear to facilitate a crossing over into the realm of myth and fable, especially in her pictures of young black men, whom she has several times photographed in groups, emerging from pitch-black backgrounds, like figures painted by Caravaggio. Out of the void they come, riding in on horseback (“Cowboys,” 2014) or throwing gang symbols with their hands (“Signs,” 2016). Both idealized by Lawson (in their physical beauty) and pathologized by the culture (as symbols of violence or fear), they are largely liberated from the kinds of domestic circumstance and context in which Lawson tends to frame her women. Such images are transhistorical, transpersonal, transcendent, and take at least some of their inspiration from previous portals, as Lawson explains to Jafa:

“Jorge Luis Borges and just his writing of “The Aleph,” and the center of the world is pinpointed in the basement. Or, in “The Matrix,” the oracle was the black woman in the kitchen smoking a cigarette and making cookies. Like, that’s where, like, the shit is—the knowledge. That’s the site of another dimension, maybe, but we don’t know it. That information has been distorted. But if black folks really knew that, we’d just be on a different plane.”

To reach this plane, you must pass through a portal—or maybe it’s a veil, or a curtain. Where should you seek it? There are some obvious points of entry you might visit—funeral homes, voodoo festivals—but you should also try places more obscure: broken couches, broken blinds, broken windows. Don’t give up. The reward will be great, once you arrive. In recent years, Lawson has begun explicitly framing this destination: she has taken a picture of a loving, naked couple in the lush Congolese forests, half hidden in the undergrowth (“The Garden,” 2015) and another of beaux fondly clinging, half-dressed, posed together in tropical gardens (“Oath,” 2013). These images are infused with a spirit of fantasy, set as they are in a dreamed-of Africa, an imagined and beloved homeland where harmony reigns, reunited souls pledge their troth, and glorious black bodies luxuriate, unashamed, in a natural environment. This isn’t a practical or political reality but a state of mind, sacred precisely because it is literally unattainable and geographically fantastic. This Africa of the mind contains Detroit and Kingston and Port-au-Prince and Brownsville. It is eternal and everywhere. It is in all of us. It is the portal that leads us back to ourselves.

0 notes

Photo

Mirabilia New work by Aoife Collins 17.01.2014 - 14.02.2014 Curated by Tom Keogh Aoife Collins is concerned with the idea of glamour. Her interest is not solely related to beauty and fame, although both present themselves in her work. She works with the more sinister idea of glamour as a shape-shifting entity changing its form to mirror the thing most desired and feared by the viewer. Feared because we sense the possibility of losing ourselves to our most superficial longings. For this exhibition in Izmir, Aoife has created new work concerned with the expectations placed upon certain images and objects surrounding the individual in contemporary life. She has chosen magazine advertisements, kitsch ornaments and samples of dazzlıng fabrics and beads to represent a certain everyday materiality which she then places under stress as the objects presented are delicately worked on, mutated or placed in anti-congrous predicaments. The straightforward disregard normally embedded in our interactions with these mass produced images, ‘objets d’art’ and decorative trimmings is exposed, as is the slippery language used by much of 20th century and contemporary art history to position our notions of what an Art work should be. Aoife Collins www.aoifecollins.com Collins received a BA from the National College of Art and Design, Dublin, followed by an MA from Chelsea College of Art and Design, London. She attended Skowhegan, Maine in 2006. Selected residencies include Location One, New York; Irish Museum of Modern Art, Dublin; Atlantic Art Centre, Florida; Scottish Sculpture Workshop, Scotland and A.I.R Kino Kino, Norway. Selected exhibitions include Tickling The Ivories, Flashpoint, Washington; There is No Release My Darling, The Process Room at the Irish Museum of Modern Art, Dublin; With Words Like Smoke, Chelsea Space, London; Altered Sequence, E:vent, London; Lost in your eyes, Form Content, London; Wet eye,Location One, New York; Culture clash, Working Rooms, London; Comfort burn, Artspace, Buffalo;Phoenix park, Kerlin Gallery, Dublin; ev+a, Limerick; Prelapsarian/here-and-now/postlapsarian, Goethe Institute, Dublin; Perspective, Ormeau Baths Gallery, Belfast, and Permaculture, Project Gallery, Dublin.

0 notes

Text

A Curious Request

When you unfold the letter, the handwriting is fluid and slanted, letters cresting over each other like waves.

'Hello,