#the king of the Connacht fairies

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Knockma Hill (Cnoc Mheada) | Co Galway

Cnoc Meadha is a hill west of Tuam, Co Galway. It is said in legend to be the residence of Finnbheara, the king of the Connacht fairies. Of two large cairns on the hill, one was thought to be the burial-place of Finnbheara and the other of (the other) Queen Medb, whose name may be transformed in the name Cnoc Meadha. Knockma Hill is topped with prehistoric cairns. G. H. Kinahan wrote of the…

View On WordPress

#Cairns#Castle Hackett#Cnoc Meadha#Co. Galway#Finnbheara#Knockma Hill#Lough Corrib#Queen Medb#the king of the Connacht fairies#The Tuath Dé Danann#Tuam

8 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Mórrigan

The Mórrigan (also Morrighan, Môr-Riogain or Morrigu), usually referred to with the definite article, was a great warrior-queen goddess in Irish-Celtic mythology. She was most associated with inciting war, then stirring up the fury and frenzy of battle, and finally, as the bringer of death. The goddess was able to take any form of living creature she wished and she helped bring about the demise of the hero-warrior Cú Chulainn after he spurned her many attempts to seduce him as different animals. Her coupling with the Dagda, another major warrior-god, was an important part of the Samhain festival which the Celts celebrated to mark the beginning of a new year.

Names & Associations

The name Mórrigan, which may have several variations of spelling, means 'great queen', 'phantom queen', 'queen of nightmares' or, more literally, 'mare-queen'. She may have evolved from the ancient territorial goddess Mór Muman who was associated with the sun and kingship in southern Ireland. She is a war-goddess, and she is particularly associated with the fury of war, hence her 'demonic' nature and another name by which she is sometimes known, the 'queen of demons'.

Mórrigan is closely associated with two other war-goddesses: Badb and Macha (or alternatively Nemain). This trio is collectively known as the Mórrigna. Some scholars suggest that the trio of goddesses are simply different aspects of the Mórrigan as the triple aspect of gods is a common theme in Celtic religion which emphasises the potency of deities. Appropriately, then, all three goddesses are the daughters of Ernmas, the great mother deity, and their father is, in some tales, the sorcerer god Cailitin. The Mórrigan has one son, the evil figure Mechi, who has three hearts, each of which contains a serpent. Mechi's father is not named.

The Mórrigan has a terrible appearance, and it is this and her aggression which have a strong psychological effect on whoever she chooses during a battle. At the same time, the goddess can be sexually attractive. Consequently, the Mórrigan is both a symbol of destruction and fertility. The goddess has certain powers such as being able to predict the future and to cast spells. Even more impressive, she can change her form at will and become a beautiful young girl, the wind, or any animal, fish or bird. The creature she is most connected with is the crow or raven, which the Celts associated with war, death, and inciting conflict. This aspect of the Mórrigan may well be the origin of the banshee, a female fairy that figures in later Irish and Scottish mythology. The banshee foretells death in a household by letting out a loud plaintive wail and, though she is rarely seen in physical form, when she is, she is an old woman with long white hair.

Another figure from Celtic folklore (in Ireland, Scotland, and Brittany) associated with the Mórrigan is the 'washer at the ford'. This figure, sometimes envisaged as a young and weeping female, at others, an old and ugly woman, was considered an omen of death as she would make certain clothes being washed in a river ford the colour of blood. Whoever's clothes were thus marked was thought to be in imminent danger.

When dwelling in this world, the Mórrigan's home was thought to be a cave in County Roscommon in northwest Ireland. This cave was known as the cave of Cruachan and the 'Hell's Gate of Ireland' since it was believed to be a passage to the Otherworld. In one myth, the Mórrigan lures the woman Odras to her cave by having one of her cows stray inside. The goddess then changes the hapless mortal into a pool of water. Cruachan was regarded as the seat of ancient kings of Connacht and has been identified as part of the group of archaeological sites at Rathcroghan in County Roscommon.

Continue reading...

57 notes

·

View notes

Text

My OCs Jacqueline and Finvarra. Been working on getting better at art and script writing these last few years so I can finally create a folklore and fairy-tale inspired Webcomic with these two. Jacqueline is the granddaughter of Jack The Giant Slayer and is searching for the giant who attacked the royal family and kidnapped her mother as a child.

He may very well hold the key to tracking down her mother, but requesting help from the fae always comes with a price.

Finvarra is based on the amorous Irish fairy King of Connacht of the same name and has strong associations with horses, ensuring good harvests as well as death. He has a penchant for "borrowing" mortals who catch his fancy and whisking them away to the Otherworld for a time. He's also the youngest brother of Angus Og and son of The Dagda. And incredibly frustrating to find information on XD Anyway, I'm going to be sharing a bunch of sketches, ref sheets, redoing old pieces and little one off comics as I continue to rework and flesh out the script in the new year. I plan on coloring this too :3 Also, if anyone knows how to put longer posts under a cut, please let me know. I want to info dump about my OCs and giants in folklore so bad but scared of annoying people ;w;

#giant tiny#g/t art#giant/tiny#size difference#Finvarra#tiny oc#gt#sfw gt#g/t related#tiny person#giant king#irish folklore#jack and the beanstalk#jack the giant slayer#MyArt#original content#fairy tale inspired#oc rambles#folklore inspired#sketch

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

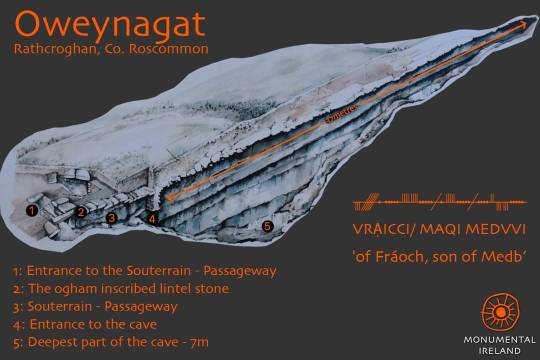

Oweynagat Cave from Monumental Ireland

"Within the ritual landscape of Rathcroghan, the ancient royal capital of Connacht, amongst the earthen mounds and ceremonial enclosures, there is an even more ancient place, a place not made by mortals.

Oweynagat, (Uaimh na gCat meaning ‘Cave of the Cats’) is an underground cavern (37m long, 2.5m wide, descending 7m below the ground) created by a fissure in the limestone bedrock. In ancient times, this rift into the earth below was considered to be an entrance to the ‘otherworld’.

In mythology it is called ‘Uaimh Cruachan’ (Crochan’s Cave) or ‘Síd Cruachan’ (Crochan’s (otherworld) Abode). Named after Crochan Crogderg, (meaning ‘blood-red cup’), a mythical character who gives her name to the ancient capital itself: Rathcroghan (meaning ‘the fort of Crochan’).

According to the Dindshenchas (Lore of Places), Crochan was handmaiden to Queen Étaíne and accompanied her mistress when she fled from her husband the High King, with her fairy lover, Midir.

While on the run they stayed at Oweynagat; which, according to the text, is a sort of otherworldly palace. Crochan was so enamoured with the cave/palace that she was granted it by Midir and it was here that Crochan later gave birth to a daughter, Medb, the mythical queen of Connacht.

Access to the cave is though a 10m long dry-stone passageway (souterrain) built in the Early Medieval Period (600-800AD). There is a lintel stone over the entrance with an Ogham inscription that reads VRẠICCI/ MAQI MEDVVI 'of Fráoch, son of Medb’. Although it cannot be proven that this inscription refers to Medb, legendary Queen of Connacht, it is hardly coincidental that the name is found here at her traditional birthplace.

The type of Ogham script in which the name is written indicates a pre-6th Century date, making it the earliest written reference to the mythical queen. Also ‘Fráoch’ was a character from the Táin who was married to Medb’s daughter, Findabair.

Although the name ‘Oweynagat’ is usually translated as ‘the cave of the cats’ (Uaimh na gCat), it may actually be a mis-translation of ‘Uaimh na Cath’ meaning ‘the cave of battle’ . A perhaps more fitting title, given the caves association with The Morrígan, the goddess of battle and strife from Irish mythology, who was also said to have resided there.

According to legend, each Samhain (Halloween), The Morrígan would emerge from the cave on a chariot, driving her fearsome otherworldly beasts out to ravage the surrounding landscape and make it ready for Winter.

“The horrid Morrígan, out of the cave of Cruachu, her fit abode, came”… (Odras - Metrical Dindshenchas)

A poem, entitled Odras, in the Metrical Dindshenchas, explains that Odras , wife of Buchat, lord of cattle, refused to let one of her cows mate with a bull owned by the Morrígan. When the Morrígan came and stole the cow, Odras followed her to Oweynagat.

However, upon arrival at the cave, Odras fell into a deep enchanted sleep. The Morrigan then cast a spell, transforming poor Odras into a river/stream which then bore her name (thought to be the River Boyle).

It was folk tales such as these that led early christian writers to describe Oweynagat as ‘Ireland’s Gate to Hell’.

These days, the best way to visit the cave is via the Rathcrogan Visitor Centre in Tulsk. They provide guided tours of the whole Rathcroghan complex, including a visit to Oweynagat... Along with a brilliant bookshop, and an excellent All-Day Breakfast."

32 notes

·

View notes

Text

the disney channel 2001 original movie luck of the irish honestly deserves a whole video essay for how wild it is but imo the wildest part is how much depth is implied about seamus mctiernan and the fact that the extent of his character is being a mere villain in a DCOM instead of the main character of like a series of original novels or something

like maybe i’m just biased bc he’s timothy omundson and also hot and i’m gay but here are canonical facts or at least implications about him:

he’s a fear dearg, a type of irish fairy really more similar to a changeling than a leprechaun, which i’ve never seen utilized in any other media

he’s stolen the luck of clearly thousands of leprechaun clans. there’s a long story to be told there

he’s been alive since at least the 1100s, most likely long before

implied by the line “it’s a king we had in ireland, and it’s a king i’ll be.” the last irish king died in 1198.

his powers, whether innate or granted by all the luck he’s stolen, include stopping time, extreme long-distance transportation, glamours complex enough to be considered reality-bending

one show of his powers was opening up a portal between time and space to just be slighly more dramatic instead of simply continuing to walk another 20 feet

yet he got bested by a couple of 13 year olds, so at the same time he is not OP

he’s extremely passionate about Being Irish, yet he actively participates in the bastardization of his own culture for either monetary gain, fame, or some extended degree of manipulation.

or possibly bc it helps him continue to steal more luck from more clans, judging by how he somehow Knew that kyle was at the fair and got a goon to steal the coin from him during the performance. which means a lot of his stolen luck was probably taken the exact same way that he got it from kyle.

he even sells fake gold-painted iron versions of the leprechaun clans’ coins as a gimmick. probably as a private joke to himself

his fame spreads far enough for him to have been on TV, and it’s implied he does cross-country tours to perform as the Saint of the Step

his attractive Modern Human form is likely an active choice of his, all the while that he surrounds himself with objectively much less attractive men (big ego lol)

those men are most likely human, too, since they don’t have accents and the movie tries to really drive home that all the leprechauns are Instinctively Irish. but they do know what HE is. so where’d he get them from?

also we don’t see any of the actual dancers after the one dance sequence at the fair. there don’t seem to be any other tour buses - it’s just the one that carries seamus and his goons. are the other dancers even real? based on seamus’s powers they could very easily all be a glamour

god he’s just so dramatic at every turn that there is simply no way he’s straight. i’m just saying.

by the end of the movie, while all the lucky gold coins in his bus (RV?) were likely (hopefully) redistributed by kyle, he still has “ten times that hidden away in a cave in Connacht.” that’s a LOT of leftover power that, if he happened to have someone loyal to him who knew where it was and could bring it to him.... could easily restore him to the way he was and get him out of the deal that he had to live in lake erie

also he’s been in america for HOW long and didn’t know what lake erie was when kyle mentioned it????

case in point, seamus mctiernan is a really fucking interesting character who had the misfortune of being used exclusively for a dumb 90-minute movie and i intend to rectify that someday

#seamus mctiernan#luck of the irish#luck of the irish 2001#timothy omundson#if i still had my original blog this would actually reach a decent amount of ppl who cared but now.. lmao

116 notes

·

View notes

Text

Irish Mythology and Folklore at Cork City Libraries

by Catherine Kane

Ireland is famous for its rich mythology and folklore traditions. From heroic tales of warriors like Fionn Mac Cumhaill and Cúchulainn, to tales of magic like Oisín’s adventures in Tír na nÓg and the Children of Lir.

Cork City Libraries have many books to offer to those who want to learn more about these stories and lose themselves for a while in the adventures of the Otherworld and the magic of its characters, as well as for those who want to learn more about our unique connection to our landscape and its traditions.

Below are a selection of titles available on the BorrowBox app for both children and adults to enjoy during the St. Patrick’s festival.

The Táin: Ireland’s Epic Adventure by Liam Mac Uistin (Illustrated by Donald Teskey)

Liam Mac Uistin’s children’s adaptation of Táin Bó Cuailnge (The Cattle Raid of Cooley) remains popular since its first publication in 1989. Such is its popularity that it has become known as the most accessible version of Ireland’s National Epic for the young reader (7-8+). It is also a lifelong personal favourite of this blog writer!

Mac Uistin was a celebrated playwright and writer in both Irish and English. This adaptation of the famous epic tells the tale of the young warrior Cúchulainn’s battle against Queen Maeve of Connacht for the Brown Bull of Cooley while he defends Ulster single-handedly against the might of Ireland’s warriors. A story of bravery, battles, magic and ancient Ireland. It is the centrepiece story of the Ulster Cycle collection of Irish mythology.

Like the popular adult translation by Thomas Kinsella, Mac Uistin’s adaptation of The Táin also features its own wonderful and iconic black sketch illustrations by illustrator Donald Teskey to bring the characters to life for the reader’s imagination. Mac Uistin’s masterful storytelling will surely keep both adult and child spellbound!

Celtic Tales of Enchantment by Liam Mac Uistin (illustrated by Shane Johnson and Russell Barnett)

Published in 2001, this short collection of four Irish folk tales includes the story of Oisín and Tír na nÓg, the humorous Quest for the Giolla Deacair and how Fionn Mac Cumhaill and his mighty Fianna warriors became trapped in The Enchanted Palace.

All told with MacUistin’s popular style and featuring illustrations by Shane Johnson and Russell Barnett, these stories will leave the young reader and adults alike enchanted and seeking out more! Ireland’s Trees: Myths, Legends and Folklore by Niall Mac Coitir (illustrated by Grania Langrishe)

Published in 2015, Ireland’s Trees: Myths, Legend and Folklore is a wonderful collection of stories and a treasure of information about Ireland’s native trees, from the magical fairy Hawthorn to the mighty Oak.

Mac Coitir focuses each chapter on a specific tree and includes detailed descriptions on traditional Irish folk beliefs and customs, information on the traditional uses of the different trees in the Irish landscape as well as examples of where they appear in Irish mythology and folklore. Each chapter includes black and white sketches in addition to the beautiful colour illustrations of the various tree species appearing throughout the book, courtesy of illustrator Grania Langrishe.

A wonderful read as we head into Spring 2021 and the trees begin open their leaves again.

Ireland’s Animals: Myths, Legends and Folklore by Niall Mac Coitir (illustrated by Gordon D’Arcy)

Published in 2015, Ireland’s Animals: Myths, Legends and Folklore introduces the reader to a wide variety of our native animals and insects.

Mac Coitir breaks down the animals into Fiery, Earthy, Airy and Water groupings and gives each creature an individual chapter. There is a wealth of information from the badger to the bee and each chapter includes fascinating folk belief and mythology as well as historical information for each creature and our interaction with them as humans.

The book also includes a collection of beautiful colour images by illustrator Gordon D’Arcy. The O’Brien Book of Irish Fairy Tales & Legends by Una Leavy (read by Aoife McMahon)

The O’Brien Book of Irish Fairy Tales & Legends by Una Leavy is a charming collection of Irish folklore. Read by Aoife McMahon, this is an audiobook collection aimed at younger children (5+). The collection is very diverse with something for everyone.

Included are short stories such as how the young warrior Cúchulainn got his famous name, the story of the magical swans of the Children of Lir and and the magical secret kept by a king!

At 1 hour and 53 minutes, this collection could be taken story by story and is sure to keep the little ones entertained. Best Loved Irish Legends by Eithne Massey (read by Aoife McMahon)

Best Loved Irish Legends by Eithne Massey is another charming collection of Irish fairy tales.

Also read by Aoife McMahon, this audiobook collection contains short stories such as the magical Salmon of Knowledge, the story of Fionn’s encounter with the giant and the adventures of Oisín in Tír na nÓg.

A shorter collection at 35 minutes, this would be ideal for sharing nice variety of stories with young children (5+). All titles available on BorrowBox

1 note

·

View note

Text

Dangerous Women of Irish Mythology

Article by Sharon Blackie @ DWP

I’ve often heard it declared that Celtic myths and legends are largely heroic in nature, dominated by the exploits of roving adventurers like Fionn Mac Cumhaill, the battles of formidable warriors like Cú Chulainn, and the courtly questings of Gawains, Galahads and Percevals for the Holy Grail. It’s true of course that the old stories have their fair share of male heroism and adventure, but what often goes unrecognised is that the major preoccupation of their heroes is with service to and stewardship of the land. And the Otherworldly (divine) woman who just as consistently appears in these tales happens to be the guardian and protector of the land, the bearer of wisdom, the root of spiritual and moral authority for the tribe.

Old Irish texts contain an abundance of stories of powerful women who were embodiments of the Sovereignty, an allegorical figure who in many senses represented the spirit of the Earth itself, the anima mundi, a deeply ecological force. The power of Sovereignty (in Irish, flaithius) was the power to determine who should rule the land – but if the power she bestowed was abused, then disaster befell the tribe. Whilst a king reigned who was favoured by the goddess, the land was fertile, and the people were prosperous and victorious in war. But if the king didn’t meet her expectations, crops would fail and the tribe would falter.

So it was that the ancient rites of kingship in Ireland included a ceremonial marriage contract, the banais ríghi, between the king and the goddess of the land, and so fundamental was that idea to the Irish way of life that those rites lasted into the sixteenth century. In this sacred marriage, the king swore to uphold and protect the land and his people, and to be true to both; in return Sovereignty granted him the gifts which would help him to keep his oath. These old stories make it clear that, while there is mutual respect between the two partners – between the goddess and the king, between the land and the people, between nature and culture, between feminine and masculine – then all is in harmony and life is filled with abundance. But when the contract is broken, the fertile land becomes the Wasteland.

Sovereignty figures, however, are very different from the usual ‘Earth-Mother’ archetypes who symbolise fertility and prosperity. Like most women in early Irish literature, they are infinitely more ambiguous, unpredictable, and on occasion, decidedly dangerous. Mess with them at your peril. Sovereignty could show herself as a beautiful young woman, fairy mistress or wife; she could appear as a powerful (and by modern standards, promiscuous) sexual figure; she could take the form of a leprous old hag, or a harbinger of war and death.

Let’s take the example of Macha, just one of many fascinating and complex Sovereignty figures in early Irish mythology. Typically, her attributes include tribal/territorial goddess (she is associated with Armagh, Ard Mhacha, in Ulster) and fertility goddess – but she is also a battle goddess. And as is so often the case with these complex divine women, there are three different versions of Macha in the early texts.

In one story, Macha appears as a typical Otherworldly bride, turning up out of the blue at the door of Cruinniuc, an unsuspecting farmer, and bestowing good fortune and prosperity on him. But one day, at a fair, disobeying Macha’s instructions, he boasts to King Conchobar of Ulster that his wife can run faster than any of the king’s horses. In spite of the fact that she is heavily pregnant, Conchobar forces Macha to come and prove herself: to race against his horses. She wins easily, but at the finishing line she collapses and goes into labour; as soon as her twins are born she dies. But before she does, she curses the men of Ulster to experience labour pains at the hour of their greatest need.

In a second story, Macha Mong Ruad (‘red mane’), daughter of Áed Rúad, is the only queen in the List of High Kings of Ireland. She defends her right to her father’s throne against male rivals who deny her because she’s a woman. She marries one of them, defeats the other in battle, and pursues the latter’s sons into the wilderness of Connacht. Surprisingly, since she’s disguised as a leper, the men seem to find her attractive and, one by one, they follow her into the woods to sleep with her. But Macha overcomes each of them and takes them back as slaves to her territory, where she forces them to build her a fortress: the great Emhain Mhacha. This Macha, clearly, is keeping the Sovereignty firmly for herself.

In a third set of references to her, Macha is a woman of the Tuatha Dé Danann, one of three daughters of Ernmas – the others being Morrígu, the dangerous and powerful goddess who appears often as a raven or crow, and Badb. In the Yellow Book of Lecan, she is referred to as ‘one of the three morrígna’, ‘raven women who instigate battle’. In the Second Battle of Mag Tuired, the Morrígan ensures victory for the Tuatha Dé Danann by sleeping with the Dagda, one of their leaders.

Inevitably perhaps, the old goddess of Sovereignty has been treated badly over the centuries, as patriarchal values have increasingly taken hold. She began to lose some of her power when these stories from ancient oral traditions were first committed to paper by Christian monks. Later, she might find herself reinvented as a saint. But if the qualities she embodied in a specific incarnation didn’t fit new images of what a good woman should be, she would be dismissed simply as a ‘fairy woman’, or (for example, in many stories about Medb – or Maeve – of Connaught) remodelled as a promiscuous, pseudo-historical queen. The Morrígan, impossible to whitewash, was simply written out of later versions of the old stories. And by the seventeenth century, when a woman could no longer be accepted in any significant position of influence, all that persisted of the once-powerful goddess of Sovereignty were the dreamlike visions known as aislings in which she appeared as a muse to inspire (male) poets – a weak, melancholy, vaguely Otherworldly maiden, sexless, romanticised and distinctly unreal.

And yet, in the last century Sovereignty, irrepressible, has risen up out of her iconic landscapes and undergone something of a renaissance. We see her, alive and well, in contemporary Irish poetry – from the fertile, female bogs to which Seamus Heaney declared his betrothal, to Nuala Ní Dhomnaill’s Cailleach-ridden Kerry mountains. We see her in a growing interest in the female divine, and the divine female of Irish legend is more interesting than most. It is her complexity, perhaps, that fascinates above all else; these dangerous women for sure don’t lend themselves to easy archetypes, to simple psychological classifications, as has happened with the Greek pantheon in way too many ‘find the goddess within you’ books by a string of Jungian psychologists. Throughout their stories, these women of old Irish literature teach us about the beauty of balance and the dangers of excess. Along with fertility comes promiscuity; the giving of life is balanced by the bringing of death; adherence to the light must be balanced by embracing the dark.

Sources

Lebor Gabála Érenn: The Book of Invasions

Annals of the Four Masters

The Second Battle of Mag Tiured

Secondary sources

Bitel, Lisa M. Land of Women: Tales of Sex and Gender from Early Ireland. (Cornell: Cornell University Press, 1996)

Clark, Rosalind. The Great Queens: Irish Goddesses from the Morrígan to Cathleen ní Houlihan. (Gerrards Cross: Colin Smythe, 1991)

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

Queen Mab

A queen appearing in Celtic mythology. She is the queen of Connacht in Ireland. Her name means "she who intoxicates." She is considered a goddess of the harvest and of rulership, owing to her many marriages with Irish kings. Queen Mab tried to seduce the Irish hero Cu Chulainn using her own daughter, but failed. In the end, enraged by the enormous losses he inflicted on the army of Connacht, she manipulated him into breaking his geis (taboo), weakening him, and then had him killed by her magicians. Mab is also known as queen of the fairies, and is identified with the fairy queen Titania.

Suggested Arcanas: Magician, Lovers

1 note

·

View note

Text

Question time

Tagged by @stereden

RULES: Always post the rules. Answer the questions asked, then write 11 new ones. Tag 11 people to answer your questions, as well as the person who tagged you.

1. Paper or e-book? I can’t actually hold paper books anymore (my hands are pretty much shot to hell) so e-book, I love my little Kindle. God I’m going to get so much flack for that aren’t I?

2. Which deceased celebrity/famous person would you bring back to life and why? Johnny Cash, I love his music, I’ve got the big San Quentin poster of his hanging behind my bedroom door, just giving me the finger all the time! Or Freddie Mercury, because he was an amazing performer and I would loved to have seen Queen live

3. Favourite fairy tale? Why? I’ve got three, and they all have their roots in Irish and Celtic history, is that okay? Cú Chulainn, also spelt Cú Chulaind or Cúchulainn ([kuːˈxʊlˠɪnʲ] ( listen); Irish for "Culann's Hound") and sometimes known in English as Cuhullin /kəˈhʊlᵻn/,[1] is an Irish mythological hero who appears in the stories of the Ulster Cycle, as well as in Scottish and Manx folklore.[2] He is believed to be an incarnation of the god Lugh, who is also his father.[3][4][5] His mother is the mortal Deichtine, sister of Conchobar mac Nessa.Born Sétanta, he gained his better-known name as a child, after killing Culann's fierce guard-dog in self-defence and offered to take its place until a replacement could be reared. At the age of seventeen he defended Ulster single-handedly against the armies of queen Medb of Connacht in the famous Táin Bó Cúailnge ("Cattle Raid of Cooley"). It was prophesied that his great deeds would give him everlasting fame, but his life would be a short one. He is known for his terrifying battle frenzy, or ríastrad[6] (translated by Thomas Kinsella as "warp spasm"[7] and by Ciaran Carson as "torque"[8]), in which he becomes an unrecognisable monster who knows neither friend nor foe. He fights from his chariot, driven by his loyal charioteer Láeg and drawn by his horses, Liath Macha and Dub Sainglend. In more modern times, Cú Chulainn is often referred to as the "Hound of Ulster".[9]

Of course, I copied that and the other two from Wikipedia

Children of Lear

Bodb Derg was elected king of the Tuatha Dé Danann, much to the annoyance of Lir. To appease Lir, Bodb gave one of his daughters, Aoibh, to him in marriage. Aoibh bore Lir four children: one girl, Fionnuala, and three sons, Aodh and twins, Fiachra and Conn.

Aoibh died, and her children missed her terribly. Wanting to keep Lir happy, Bodb sent another of his daughters, Aoife, to marry Lir.

Jealous of the children's love for each other and for their father, Aoife plotted to get rid of the children. On a journey with the children to Bodb's house, she ordered her servant to kill them, but the servant refused. In anger, she tried to kill them herself, but did not have the courage. Instead, she used her magic to turn the children into swans. When Bodb heard of this, he transformed Aoife into an air demon for eternity.

As swans, the children had to spend 300 years on Lough Derravaragh (a lake near their father's castle), 300 years in the Sea of Moyle, and 300 years on the waters of Irrus Domnann[2][3] Erris near to Inishglora Island (Inis Gluaire).[4] To end the spell, they would have to be blessed by a monk. While the children were swans, Saint Patrick converted Ireland to Christianity.

And the Legend Behind The Giants Causeway

In overall Irish mythology, Fionn mac Cumhaill is not a giant but a hero with supernatural abilities. In Fairy and Folk Tales of the Irish Peasantry (1888) it is noted that, over time, "the pagan gods of Ireland [...] grew smaller and smaller in the popular imagination, until they turned into the fairies; the pagan heroes grew bigger and bigger, until they turned into the giants".[12] There are no surviving pre-Christian stories about the Giant's Causeway, but it may have originally been associated with the Fomorians (Fomhóraigh);[13] the Irish name Clochán na bhFomhóraigh or Clochán na bhFomhórach means "stepping stones of the Fomhóraigh". The Fomhóraigh are a race of supernatural beings in Irish mythology who were sometimes described as giants and who may have originally been part of a pre-Christian pantheon.[14]

Goodness you’d be forgiven for thinking that I was a rampant nationalist but Mum had a big book of Irish Legends and Fairy Tales when I was growing up, so I probably heard more about those stories than I did about Thumblina and such. I also went to a Catholic/Nationalist primary school and I can remember the teachers reading us those stories.

4. What is your favourite season and why? Summer, because I can see more of my extended family, we’re all spread over Ireland and one in America! And I tend to get less pain in the summer months, right now I’m a little ball of pain

5. If you could do any sport or hobby, what would it be? Wheelchair rugby (so very cool) or Gaelic Football

6. What did you want to be when you grew up when you were a kid? (like <12) Honestly? I think at one stage I want to be a postwoman (then I realised that dogs would bark at me so that put me off) then a teacher

7. Do you speak multiple languages? I learned Spanish and French is school but I can’t remember enough to converse. I might have learned a tiny bit of Irish but I’m not sure. So unless sarcasm counts? Only English

8. What language would you like to learn? French or Irish, one of the hospitals I go to is in West Belfast and I’d love to even be able to read the Irish on the road signs, even though the signs are also in English, it would be interesting

9. Harry Potter or His Dark Materials? Harry Potter far and away, did you know I finished reading the first Harry Potter book in a hospital in France when I had been knocked down?

10. What TV show would you like to live in? Oh, now that’s a difficult one maybe Doctor Who?

11. If you could have the power to convince ONE person in the world that your opinion is the right one and that they would change their actions in consequence, who would it be? Trump, or maybe the politicians of Northern Ireland

My turn now!

1. Do you have any bad habits that you keep thinking you need to quit? 2. Do you ever think I wish I hadn’t reblogged that? Or I shouldn’t have posted that? 3. After you write a fic do you ever stare at the screen waiting for someone to comment or hit kudos? 4. Do you have a loud sneeze? 5. What is your favourite fandom? 6. Do you like animals? 7. Have you any pets? 8. Harry Potter or Lord of the Rings? 9. Do you ever feel like some elements of fandom are toxic? 10. Do you ever feel like punching our politicians in the throat (or balls)? If so who was it? 11. Have you ever broken the law?

And I’m tagging…. @stereden @pinkpandorafrog @latessitrice @absentlyabbie @usedkarma @veryprompted @thestanceyg @nobutsiriuslywhat @leighlim @phoenix-173 @notbecauseofvictories and anyone else who wants to do it

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

An Táin, a tale retold -Time for The March

It all started with a husband and wife having an argument. Maebh and her husband Ailill were having a grand ould time in Cruachanaí admiring their armies and wealth til they started a "mine is better than yours" quarrel that got out of hand. "I'm better than you" said the man. "No, you're not" said his wife in return "I'm better than you." "I have more than you" says he. "No you don't, I have more than you". In fact they were equal in all except that Ailill had a bull and Maebh did not. "Ah but I have a bull and you don't" said Ailill. "That is really my bull, you just took him." "No I didn't, he preferred to be with me so Finnbhennach (The name of the Bull, the white one) is mine and now I have more bull than you." "So you do but I can get one of my own and I will" and off she went on her travels to Cooley to rent the great bull Donn Cuailinge (the brown one) and thereby have as much bull as her husband. And she nearly did ....... Until her servants let the cat out of the bag, in their merrymaking and partying at Cooley,in Ulster that she would have taken the bull by the horns with or without his owner Dáire mac Fiachna's permission. He didn't like that and he chased them home with their tails between their legs and no bull. Maebh being proud and not one to let it go, got her armies together with Fergus mac Róich and headed off to take the bull from Dáire. Unfortunately for the men of Ulster they were taken ill thanks to Macha putting a curse on their king because he wasn't very nice to her, and that's a nice way of putting it but it's another story for another day. The only one able to fight was the young hero Cú Chulainn who was too busy horsing around instead of guarding the border so he never noticed the army coming in to capture the bull. He and Láeg, his charioteer, (Did you know they had great chariots, better than any roman ones?) waged guerrilla warfare against the army and when that didn't work he fought champion after champion in single combat for a very long time, I mean, a very very long time, a very very very long time and Maeve still got the bull. Poor Cu Chulainn had a hard old time. The fairy folk played with him The Morrigan, a powerful Goddess, pretended to be a beautiful young woman and offered to love him but he was a bit too busy for love at that time and said no. She got angry and messed with him in his next fight. She became an eel who tripped him, a wolf who stampeded the cattle and then a heifer at the head of the stampede. Cú Chulainn wounded her each time and once he won his fight Morrigan appeared as an old woman milking a cow with three wounds in the places Cú Chulainn had wounded the eel, the wolf and the heifer. She offered him milk and he gladly took it being thirsty after his battle and each time he took a drink, (funny enough three times) he blessed her and each blessing healed her wounds. Lugh, a great and mighty God visited him during a really heavy fight and announced he was Cú Chulainn's father, timing is everything! Lugh put him to sleep for guess how many days...... three, imagine that, and he healed his wounds while he slept. While he was sleeping the young warriors of Ulster came to help in the fight but were killed. He woke up and was very angry and turned into The Incredible Hulk, oh sorry that's another story, but his body did twist in his skin in anger and he became a monster full of rage and went after the Connacht camp, killing six for every one of his friends that were killed. Nasty!! Once he calmed down he began the one on one battles and the rounds were short and full of knock outs like McGregors. Maebh didn't stick to the rules at times and sent lots of men at once for the fight but he still won because he is Wolverine, oh I mean Cú Chulainn. Now you all know he had just met Lugh, his father so that means he wasn't brought up by Lugh but had a foster-father, and this man's name was Fergus, the one mentioned before so you now know that unfortunately Fergus was on the Connacht team and not the Ulster team. Fergus was sent out to fight his foster-son whether he wanted to or not. They made a pact to take turns winning with Cú Chulainn agreeing to yield to him on the condition that Fergus yielded the next time they meet. Now remember that!! The fighting went on and on for miles and miles and up and down the country, along the path of An Táin March that we are going to join in, aren't we? Finally there was a How many days? Yes you guessed it, a three-day duel between the hero, who is the hero? Cú Chulainn and his foster-brother and best friend Ferdiad, who he grew up with and trained with and loved. Cú Chulainn won and killed Ferdiad. Then, when it was too late for Ferdiad, just like in the films, the Ulstermen started to get better, one by one at first, then all of them and the final battle began. Cú Chulainn was a bit tired and sore so sat down. Fergus , his foster father was about to kill Conchobar, a king of Ulster, but Cormac, Conchobar's son stopped him so Fergus chopped the top of, how many? Yes, three hills off in rage. Cú Chulainn got fed up watching and joined in and confronted Fergus, reminding him of their deal.Do you remember their deal? Fergus yielded to Cú Chulainn and his allies from Connacht panicked and so Maebh had to retreat, ah but.... She got the bull! Maebh brought the brown bull back to Connacht but the white bull wasn't happy and they fought another long battle. The brown bull killed the white bull but he was wounded too and wandered around Ireland creating placenames before going home to die. Some people say that Cú Chulainn was wounded by Ferdiad and was tied to a post facing his enemies standing while he died but actually that's another story too.

0 notes

Text

Knockma Hill (Cnoc Mheada) | Co Galway

Knockma Hill (Cnoc Mheada) | Co Galway

Cnoc Meadha is a hill west of Tuam, Co Galway. It is said in legend to be the residence of Finnbheara, the king of the Connacht fairies. Of two large cairns on the hill, one was thought to be the burial-place of Finnbheara and the other of (the other) Queen Medb, whose name may be transformed in the name Cnoc Meadha. Knockma Hill is topped with prehistoric cairns. G. H. Kinahan wrote of the…

View On WordPress

#Cairns#Castle Hackett#Cnoc Meadha#Co. Galway#Finnbheara#Knockma Hill#Lough Corrib#Queen Medb#the king of the Connacht fairies#The Tuath Dé Danann#Tuam

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Knockma Hill (Cnoc Mheada) | Co Galway

Knockma Hill (Cnoc Mheada) | Co Galway

Cnoc Meadha is a hill west of Tuam, Co Galway. It is said in legend to be the residence of Finnbheara, the king of the Connacht fairies. Of two large cairns on the hill, one was thought to be the burial-place of Finnbheara and the other of (the other) Queen Medb, whose name may be transformed in the name Cnoc Meadha. Knockma Hill is topped with prehistoric cairns. G. H. Kinahan wrote of the…

View On WordPress

#Cairns#Castle Hackett#Cnoc Meadha#Co. Galway#Finnbheara#Knockma Hill#Lough Corrib#Queen Medb#the king of the Connacht fairies#The Tuath Dé Danann#Tuam

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Knockma Hill (Cnoc Mheada) | Co Galway

Knockma Hill (Cnoc Mheada) | Co Galway

Cnoc Meadha is a hill west of Tuam, Co Galway.

It is said in legend to be the residence of Finnbheara, the king of the Connacht fairies. Of two large cairns on the hill, one was thought to be the burial-place of Finnbheara and the other of (the other) Queen Medb, whose name may be transformed in the name Cnoc Meadha. Knockma Hill is topped with prehistoric cairns.

G. H. Kinahan wrote of the place:

View On WordPress

#Cairns#Castle Hackett#Cnoc Meadha#Co. Galway#Finnbheara#Knockma Hill#Lough Corrib#Queen Medb#the king of the Connacht fairies#The Tuath Dé Danann#Tuam

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Knockma Hill (Cnoc Mheada) | Co Galway

Knockma Hill (Cnoc Mheada) | Co Galway

Cnoc Meadha is a hill west of Tuam, Co Galway.

It is said in legend to be the residence of Finnbheara, the king of the Connacht fairies. Of two large cairns on the hill, one was thought to be the burial-place of Finnbheara and the other of (the other) Queen Medb, whose name may be transformed in the name Cnoc Meadha. Knockma Hill is topped with prehistoric cairns.

G. H. Kinahan wrote of the place:

View On WordPress

#Cairns#Castle Hackett#Cnoc Meadha#Co. Galway#Finnbheara#Knockma Hill#Lough Corrib#Queen Medb#the king of the Connacht fairies#The Tuath Dé Danann#Tuam

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Knockma Hill (Cnoc Mheada) – Co Galway

Knockma Hill (Cnoc Mheada) – Co Galway

Cnoc Meadha is a hill west of Tuam, Co Galway.

It is said in legend to be the residence of Finnbheara, the king of the Connacht fairies. Of two large cairns on the hill, one was thought to be the burial-place of Finnbheara and the other of (the other) Queen Medb, whose name may be transformed in the name Cnoc Meadha. Knockma Hill is topped with prehistoric cairns.

G. H. Kinahan wrote of the place:

View On WordPress

#Cairns#Castle Hackett#Cnoc Meadha#Co. Galway#Finnbheara#Knockma Hill#Lough Corrib#Queen Medb#the king of the Connacht fairies#The Tuath Dé Danann#Tuam

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Knockma Hill (Cnoc Meadha), Co Galway

Knockma Hill (Cnoc Meadha), Co Galway

Cnoc Meadha is a hill west of Tuam, Co Galway. It is said in legend to be the residence of Finnbheara, the king of the Connacht fairies. Of two large cairns on the hill, one was thought to be the burial-place of Finnbheara and the other of (the other) Queen Medb, whose name may be transformed in the name Cnoc Meadha. Knockma Hill is topped with prehistoric cairns. G. H. Kinahan wrote of the…

View On WordPress

#Cairns#Castle Hackett#Cnoc Meadha#Co. Galway#Finnbheara#Knockma Hill#Lough Corrib#Queen Medb#the king of the Connacht fairies#The Tuath Dé Danann#Tuam

1 note

·

View note