#the intelligence trap by david robson

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

❞ إذا نَشَأْتَ بين أشخاص لا يثقون بالعلماء، فقد تكتسب ميلًا لتجاهل الأدلة التجريبية والوثوق بالنظريات غير المُثبَتة ❝

ديفيد روبسون | فخ الذكاء

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Is Human Intelligence Overrated? Experts Suggest Our Big Brains May Not Be So Great After All

Is Human Intelligence Overrated? Experts Suggest Our Big Brains May Not Be So Great After All Human intelligence has achieved remarkable feats, from advancing medicine to exploring outer space. However, some experts argue that our cognitive abilities might not be as beneficial as we believe, and could even pose risks to life on Earth. A Shift in Perspective on Intelligence Justin Gregg, a senior researcher with the Dolphin Communication Project, highlights how our perception of intelligence can lead to arrogance. His work with dolphins made him reconsider the notion that human intelligence is uniquely superior. “Maybe it’s a bad thing if dolphins were as smart as humans,” he suggests, “because maybe human intelligence isn’t all that great.” Gregg points out that human intelligence has contributed to the extinction of species at an unprecedented rate, driven by technological advances and cultural developments. “Humans are on track to be more destructive than an asteroid when it comes to loss of biodiversity,” he states, emphasizing that our intelligence has led to significant ecological harm. Historical Context of Human Intelligence Thomas Moynihan, a researcher at Cambridge University, notes that the idea of human intelligence as a double-edged sword dates back to thinkers like Saint Augustine, who associated human nature with original sin. He argues that the current state of human intelligence is detrimental to the biosphere. Despite the negative implications, Moynihan believes that intelligence is flexible and can be directed toward repairing the damage we’ve caused. “We can become intelligent in ways that might reverse or rectify some of that damage,” he says. The Dark Side of Reasoning The capacity for reasoning, often seen as a hallmark of human intelligence, can also lead to moral justifications for violence and destruction. Gregg points out that while animals may act violently in response to immediate threats, humans can rationalize mass atrocities for ethical reasons. This ability to justify horrific actions sets humans apart from other animals in a troubling way. Kristin Andrews, a philosopher at York University, warns against romanticizing animal behavior. She highlights that animals can also exhibit extreme violence, citing examples of chimpanzee warfare and other brutal behaviors in the animal kingdom. “Animals can be horrific to each other as well,” she observes. Anthropomorphism and Human Exceptionalism The tendency to project human moral attributes onto animals has a long history. From Aristotle to modern thinkers, humans have often considered their intelligence as a unique trait that sets them apart. However, this exceptionalism comes with consequences. Friedrich Nietzsche, in his work Untimely Meditations, expressed envy toward animals, noting their apparent happiness unburdened by human anxieties. Moynihan echoes this sentiment, suggesting that throughout history, there has been a perception that animals might be happier and more stable than humans, who are often seen as “diseased” by their intelligence. The Bittersweet Nature of Human Awareness David Robson, author of The Intelligence Trap, acknowledges the suffering that comes with human awareness but also celebrates the beauty it brings. He argues that while animals may not contemplate existential questions, the ability to marvel at the universe is a uniquely human experience. “It is a bittersweet experience, but it’s not something that I would want to sacrifice,” he says. Embracing Other Forms of Life Moynihan advises against projecting our desires onto animals. “We should be suspicious when we’re projecting our desires and wishes onto other animals,” he warns. Instead, he advocates for allowing animals to exist in their own right, appreciating their unique forms of life without imposing human narratives onto them. “Being a narwhal is great. But let the narwhals be narwhals rather than vessels for our own shame and strange complexes,” he concludes. Thank you for taking the time to read this article! Your thoughts and feedback are incredibly valuable to me. What do you think about the topics discussed? Please share your insights in the comments section below, as your input helps me create even better content. I’m also eager to hear your stories! If you have a special experience, a unique story, or interesting anecdotes from your life or surroundings, please send them to me at [email protected]. Your stories could inspire others and add depth to our discussions. If you enjoyed this post and want to stay updated with more informative and engaging articles, don’t forget to hit the subscribe button! I’m committed to bringing you the latest insights and trends, so stay tuned for upcoming posts. Wishing you a wonderful day ahead, and I look forward to connecting with you in the comments and reading your stories! Read the full article

0 notes

Text

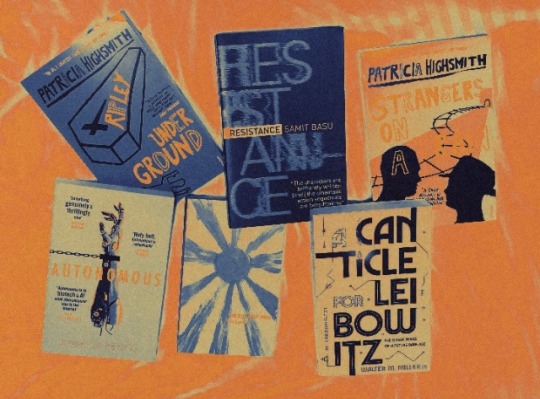

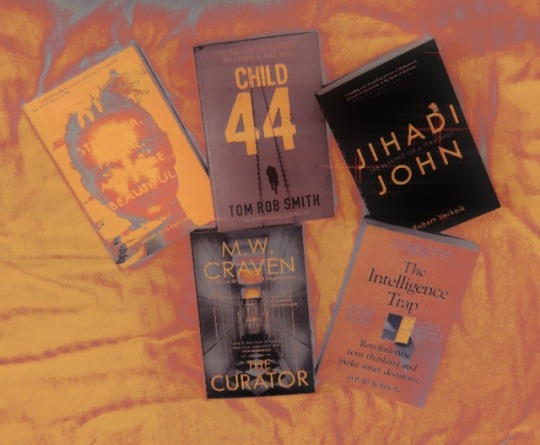

went on one hell of a book haul at my country's biggest book sale of the year! looking forward to reading all of this in the coming weeks 👻

#autonomous by annalee newitz#ripley under ground by patricia highsmith#resistance by samit basu#the railway man by eric lomax#canticle for leibowitz by walter m. miller#stranger on a train by patricia highsmith#stronger faster and more beautiful by arwen elys dayton#child 44 by tom rob smith#the curator by m.w. craven#jihadi john: the making of a terrorist by robert verkaik#the intelligence trap by david robson#bookblr#books

1 note

·

View note

Link

The Intelligence Trap: Why Smart People Make Dumb Mistakes by David Robson

US: https://amzn.to/2Kf0vH5

UK: https://amzn.to/2K0s3Qf

#books#culture#media#donald trump#fake news#pschology#The Intelligence Trap#David Robson#book excerpt#human intelligence

0 notes

Quote

Il meccanismo mentale che ci impedisce di valutare in maniera corretta questo tipo di crescita — la crescita esponenziale: quella, purtroppo, che segue la diffusione del coronavirus, che può portare al raddoppio dei casi ogni 3-4 giorni senza misure di contenimento — è noto come «exponential growth bias»: e secondo quanto riportato, numerosi studi hanno dimostrato che chi ragiona in questo modo sottovaluta la pericolosità della diffusione del virus ed è più propenso a ignorare le regole di distanziamento sociale, copertura di naso e bocca, igiene delle mani. «In altre parole: questo semplice errore matematico potrebbe costare parecchie vite, e la sua “correzione” dovrebbe ora essere una priorità», scrive David Robson, autore del libro «The intelligence trap: why smart people do dumb things»

Dall’articolo "L’errore matematico (fatale) che non ci fa capire il coronavirus" su Corriere.it

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

An App Help You Win the Argument

Argument is an inevitable way of communication, because people have different ideas and support different thoughts, it is easy to have disputes when thinking collides. In daily life, it is common to argue with your parents, friends, lovers, classmates, colleagues, and even strangers for various reasons, but argument with other people, is not a thing that most people good at.

We are not unfamiliar with the angry mood that comes from the bitter quarrel, but the consequences of anger are far beyond expectations. Holistic physician Dr. Svetlana Kogan has warned of the risks of a serious debate that could lead to “increased blood pressure, increased heart rate, diarrhea, and increased risk of diabetes and stroke”. Anger can bring pressure to your body, and this pressure will affect almost all systems, which will cause a consequence that is hard to be accepted (MADORMO, 2017).

However, the harm discussed above is only the for physical health, argument will also have psychological pain. You may get tired of yourself or doubt your own value or ability by losing an argument, trapped in anger all day, or lose a close relationship because of inappropriate and excessively mean words (MADORMO, 2017). The sequelae of these fights can also affect people's psychology for a long time. Therefore, it is necessary for us to have a smart and peaceful ability to solve conflicts.

It is quite challenge to achieve the goal in real life as some people find it hard to face a quarrel. The tension brought about by a fight can make our bodies quickly enter a defensive state, which makes the heart beat violently, breathing faster and muscles tense. These comprehensive reactions are also called "fight or flight" reactions (Harvard Health, 2011). In addition, the researchers found that stress mood can damage the neural basis of semantic decision-making, thus changing behavior and physiological activities. Therefore, there are some people in the argument because of impulsive emotion to organize their own language badly, not able to fully refute the other party, and lose the argument (Neurosci, 2016). Besides, certain people will want to quickly escape from the uncomfortable situation to the safe area because they have no sense of security, but escape does not completely solve the problem, on the contrary, it makes us always recall the quarrel that we didn't play well, and be more and more regretful to get deeper hurt.

Thus, I would like to design an App that can help people argue with each other. The purpose is not to encourage people to be more aggressive, but to let people face every argument calmly and intelligently, could express their views completely, use civilized language, and end rationally.

To achieve my goal, I did plenty of research about how to win an argument. To sum up, there are the following tips could help you quickly sort out your thoughts and stabilize your mood.

The first point is to use questions to control the discussion and let the other party find their own logical mistakes.

The second point is to reexamine the problem and explain your point of view from the other party's point of view to make it easier for the other party to accept (Robson, 2019).

The third point is to try to be open to compromise and seek a win-win situation. Your goal is to solve the problem, not to be totally hostile to others (Sloane).

Of course, we know that when you quarrel with others, your mood is very intense, so it is difficult to think of a calm method. Our products can be connected with headphones to monitor the intensity of your mood through the heart rate, so we can choose to play different voice prompts to keep users calm and clear mind.

In addition, I also want to include a lot of quarrel scenes or conversations in my software to help users get familiar with the quarrel process like a game. After many practice, I believe they can face the quarrel more confidently. There will be different level that waiting for the users.

As for interface design, I want to be concise, but at the same time, I want to use cool color matching, which will make the whole training more rational.

Slides:

https://docs.google.com/presentation/d/1qSrlcZas-DKLi9wWGb_HtyUwAwh0iaamKQB4yiAK16g/edit#slide=id.p

Reference:

Carrie Madormo, RN. “What Really Happens To Your Body When You Fight With Your SO.” TheList.com, The List, 4 Apr. 2017, www.thelist.com/54883/really-happens-body-fight/.

Publishing, Harvard Health. “Understanding the Stress Response.” Harvard Health, www.health.harvard.edu/staying-healthy/understanding-the-stress-response.

Garfinkel, Sarah N, et al. “Anger in Brain and Body: the Neural and Physiological Perturbation of Decision-Making by Emotion.” Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, Oxford University Press, Jan. 2016, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4692323/.

Robson, David. “The Science of Influencing People: Six Ways to Win an Argument.” The Guardian, Guardian News and Media, 30 June 2019, www.theguardian.com/science/2019/jun/30/the-science-of-influencing-people-six-ways-to-win-an-argument.

Sloane, Paul. “How to Win an Argument - Dos, Don'ts and Sneaky Tactics.” Lifehack, Lifehack, 17 Dec. 2019, www.lifehack.org/articles/communication/how-to-win-arguments-dos-donts-and-sneaky-tactics.html.

0 notes

Text

'Positive Deviants': Why Rebellious Workers Spark Great Ideas

Organisations Tend to See Rebels as Troublemakers – But Suppressing These Individuals and Their Ideas Could Backfire.

— By Loizos Heracleous and David Robson | 1st June 2021 | BBC News

In the 1980s, a group of young engineers at Nasa’s Johnson Space Center in Houston realised that the 1960s Apollo-era mission control set-up would struggle to handle the more complex challenges of flying the space shuttle.

The engineers’ concerns fell on deaf ears; Nasa knew and trusted the Apollo-era systems, which had successfully sent humans to the moon. Undeterred, the renegade group – who subsequently called themselves ‘the pirates’ – began to code new software for the mission control sub-systems in their free time, using borrowed equipment from Nasa suppliers. Their system was based on commercially available personal workstations linked through a Unix network, in what the pirates felt was a more resilient and adaptive set-up. After several months, they physically brought their system into mission control to test it – but they were asked to leave by the flight controllers.

At that point Gene Kranz, the legendary mission control director, stepped in. He had faith in the renegade engineers, knew how important the project would be in terms of bringing in needed capability – and asked the other flight directors to give the group a chance.

To test it, the pirate system ran alongside the incumbent system for a few months. When the mainframe system crashed twice, the pirate system kept going. In hindsight, it’s easy to see its benefits; the new system could display graphics and colours, was easily re-programmable and could conduct real-time diagnostics based on multiple parameters using early forms of artificial intelligence. These capabilities were sorely lacking in the incumbent system.

The rebel engineers proved themselves and their system through a baptism of fire. All subsystems of mission control were then gradually transitioned to the pirate system, which received a “Hammer Award” from then-Vice President Al Gore for having made dramatic improvements to the functioning of government. The pirates’ system had saved $74m (£52m) in development, and $22m in recurrent annual running costs. The rebel engineers were then asked to design the mission control system for the forthcoming International Space Station.

Organisations have rules and policies designed to promote stability, predictability, efficiency and productivity – and we tend to see people who don’t get with the programme as troublemakers. Yet, as the NASA pirates show, suppressing or ignoring these individuals and their ideas could backfire, potentially depriving companies of a potent source of agility, insight and innovation.

Why Rebels Rule

There is psychological evidence that rebelliousness is essential for creativity. Harvard psychiatrist Albert Rothenberg spent more than five decades researching individuals who had made ground-breaking contributions to science, literature and the arts, seeking to understand what drove their creativity. As part of a broader research project that encompassed structured interviews, experimental studies and documentary analysis, Rothenberg interviewed 22 Nobel Laureates. He found that they were strongly emotionally driven by wanting to create something new, rather than extend current perspectives. He found they consciously saw things with a fresh mindset rather than blindly following established wisdom – two qualities that would seem to suggest a rebellious, rather than conformist, personality.

The Nasa pirates' system led to the successful introduction of new technologies at Mission Control - even though flight controllers initially rejected the ideas

To investigate the benefits of rebelliousness further, a team led by Paraskevas Petrou at the Erasmus University Rotterdam recently surveyed 156 employees from various industries in the Netherlands. They measured rebelliousness via a questionnaire that asked participants to rate their agreement with statements such as:

I break rules

I know how to get around the rules

I use swear words

I resist authority

The team also questioned the participants about their use of creativity over the previous week, along with more general attitudes to their work. As Rothenberg might have predicted, the rule-breakers were indeed more creative, but the effects depended on some other traits. For rebelliousness to have a more consistently positive impact on their work, the individuals also had to be “promotion focused” – that is, goal driven and interested in personal growth – while also tolerating the possibility of failure.

“You have to be really focused on the positive that you can achieve,” says Petrou, who is an assistant professor in social and behavioural sciences. These attitudes can depend on context and the overall climate within a company or organisation, he says – and whether it tolerates failures or not.

Often these ‘rebels with a cause’ – also known as positive or constructive “deviants” – may be motivated because they care for the organisation and its mission, and feel psychological discomfort when they see that important capabilities clearly need improvement.

Observational studies provide many more examples besides NASA’s pirates. The context and actors may change, but the substance is remarkably similar. A small group of committed individuals who think differently and who have valid strategic insights can foster ground-breaking innovations that promote success of the enterprise. This is how the IBM business model transitioned to the internet, and how the Apple Macintosh was created.

These ‘rebels with a cause’ may be motivated because they care for the organisation and its mission

Thinking differently and challenging established paradigms of space flight is also how the entrepreneur Elon Musk and others in commercial space are building technology such as reusable rockets that will radically restructure launch economics and open up space for human expansion and commerce.

Fostering the Rebellious Spirit

Unfortunately, it can be hard to maintain a corporate culture that allows rebels to flourish. Over time, the rules and standard operating procedures that support uniform service delivery, efficiency and reliable processes, can also create inertia and work against adaptability and innovation. History and culture conspire to keep things being done the same way as they’ve ‘always’ been done. People judge proposed innovations on whether they agree with the established paradigm, rather than their ability to create new paradigms. Such a state is dangerous, since it stifles needed change.

Leaders need to be aware of these tendencies and fight against them. They should promote a culture in which challenging the status quo and pushing boundaries are seen as legitimate behaviours, rather than marking rebellious individuals as troublemakers and compromising their careers. If they are committed to creativity, leaders should take practical steps to ensure that progress is achievable, ensuring that the “rebels” have the available space, funding and time to pursue innovative ideas that may appear crazy, unwarranted or out of place at the time, but that could subsequently save the organisation.

NASA shows that change is possible. Today, it is a network-based organisation that partners with commercial space actors to tap the best available technology – wherever it may be. And this more open-minded approach to change owes a lot to the work of its internal renegades, who provided proof of concept of employing commercially available technology decades ago and challenged traditional ways of doing things.

For individual rebels, it might be worth considering your own motivations. As chief rebel and industry slayer Steve Jobs advised the 2005 Stanford University graduating class in his commencement speech, we have to look inside to find what we truly love, and then go for it. When we do something that we love, this emotional commitment will drive us to do the right thing when the situation warrants it, even when others are opposed to what we are doing or do not see things the way we do. In other words, don’t just rebel for the sake of it – but find a cause that really matters to you and then channel your frustrations into clear goals. As Petrou’s work had shown, that’s the secret of the “positive deviant”.

If we can connect with others who also have the drive to improve things and to create new capabilities, even better; there is strength in common purpose. Ken Kutaragi – the man behind the PlayStation – could count on Sony CEO Norio Ohga, who was himself a rebel at heart. Ohga was trained as an opera singer and conductor, whom Sony noticed when he wrote a complaint letter to the company about the quality of its tape recorders. Ohga led Sony to great success during his tenure between 1982 and 1995, summarising his approach as pursuing the unconventional: “we are always chasing after things other companies won’t touch”. So, try to look for other like-minded people within your organisation, who might help to provide the support and clear the obstacles where necessary.

Rebels may have a bad reputation, but in the right environment, and with the right motivations, they can achieve amazing things.

Loizos Heracleous is a Professor of Strategy at Warwick Business School and an Associate Fellow at the University of Oxford. He is the author of Janus Strategy. This piece is partly based on Dr Heracleous’ own research with Nasa.

— David Robson is the is author of The Intelligence Trap: Revolutionise Your Thinking and Make Wiser Decisions (Hodder & Stoughton/WW Norton).

0 notes

Link

I just read this and saved it to Pocket. Excerpt: In this edited excerpt from his new book, The Intelligence Trap, David Robson explains why a high IQ and education won’t necessarily protect you from highly irrational behavior — and may sometimes amplify your errors.

0 notes

Text

❞ رغم أن عقودًا من الأبحاث النفسية وثَّقت ميل البشر إلى اللا عقلانية، فلم يبدأ العلماء إلا مؤخرًا نسبيًّا في قياس مدى اختلاف اللا عقلانية بين الأفراد، ودراسة ما إذا كان ذلك التباين يرتبط بمقاييس الذكاء. وتوصلوا إلى أن العلاقة بين الاثنين بعيدة كل البعد عن المثالية، فمن الممكن أن يحصل المرء، مثلًا، على درجة عالية للغاية في اختبارات سات توضح براعته في التفكير التجريدي، بينما يكون أداؤه ضعيفًا في الاختبارات الحديثة للعقلانية؛ وهو التناقض الذي يُعرَف باسم «غياب العقلانية» ❝

ديفيد روبسون | فخ الذكاء

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Why the smartest people can make the dumbest mistakes

New Post has been published on https://nexcraft.co/why-the-smartest-people-can-make-the-dumbest-mistakes/

Why the smartest people can make the dumbest mistakes

A high IQ and education won’t necessarily protect you from highly irrational behavior—and it may sometimes amplify your errors. (Pexels/)

It is June 17, 1922, and two middle-aged men—one short and squat, the other tall and lumbering with a walrus moustache—are sitting on the beach in Atlantic City, New Jersey. They are Harry Houdini and Arthur Conan Doyle—and by the end of the evening, their friendship will never be the same again.

It ended as it began—with a séance. Spiritualism was all the rage among London’s wealthy elite, and Conan Doyle was a firm believer, attending five or six gatherings a week. He even claimed that his wife Jean had some psychic talent, and that she had started to channel a spirit guide, Phineas, who dictated where they should live and when they should travel.

Houdini, in contrast, was a skeptic, but he still claimed to have an open mind, and on a visit to England two years previously, he had contacted Conan Doyle to discuss his recent book on the subject. Now Conan Doyle was in the middle of an American book tour, and he invited Houdini to join him in Atlantic City.

The visit had begun amicably enough. Houdini had helped to teach Conan Doyle’s boys to dive, and the group were resting at the seafront when Conan Doyle decided to invite Houdini up to his hotel room for an impromptu séance, with Jean as the medium. He knew that Houdini had been mourning the loss of his mother, and he hoped that his wife might be able to make contact with the other side.

And so they returned to the Ambassador Hotel, closed the curtains, and waited for inspiration to strike. Jean sat in a kind of trance with a pencil in one hand as the men sat by and watched. She sat with her pen poised over the writing pad, before her hand began to fly wildly across the page. “Oh, my darling, thank God, at last I’m through,” the spirit began to write. “I’ve tried oh so often—now I am happy…” By the end of the séance, Jean had written around twenty pages in “angular, erratic script.”

Her husband was utterly bewitched—but Houdini was less than impressed. Why had his mother, a Jew, professed herself to be a Christian? How had this Hungarian immigrant written her messages in perfect English—“a language which she had never learned!”? And why did she not bother to mention that it was her birthday?

Meeting these two men for the first time, you would have been forgiven for expecting Conan Doyle to be the more critical thinker. Yet it was the professional illusionist, a Hungarian immigrant whose education had ended at the age of twelve, who could see through the fraud.

While decades of psychological research have documented humanity’s more irrational tendencies, it is only relatively recently that scientists have started to measure how that irrationality varies between individuals, and whether that variance is related to measures of intelligence. They are finding that the two are far from perfectly correlated: it is possible to have a very high IQ or SAT score, while still performing badly on these new tests of rationality—a mismatch known as “dysrationalia.” Indeed, there are some situations in which intelligence and education may sometimes exaggerate and amplify your mistakes.

David Robson’s new book <em><a href=”https://www.amazon.com/Intelligence-Trap-Smart-People-Mistakes/dp/0393651428″>The Intelligence Trap</a></em> is on sale now. (Courtesy of W. W. Norton & Company, Inc./)

A true recognition of dysrationalia—and its potential for harm—has taken decades to blossom, but the roots of the idea can be found in the now legendary work of two Israeli researchers, Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky, who identified many cognitive biases and heuristics (quick-and-easy rules of thumb) that can skew our reasoning.

One of their most striking experiments asked participants to spin a “wheel of fortune,” which landed on a number between 1 and 100, before considering general knowledge questions—such as estimating the number of African countries that are represented in the UN. The wheel of fortune should, of course, have had no influence on their answers—but the effect was quite profound. The lower the quantity on the wheel, the smaller their estimate—the arbitrary value had planted a figure in their mind, “anchoring” their judgment.

You have probably fallen for anchoring yourself many times while shopping during sales. Suppose you are looking for a new TV. You had expected to pay around $150, but then you find a real bargain: a $300 item reduced to $200. Seeing the original price anchors your perception of what is an acceptable price to pay, meaning that you will go above your initial budget.

Other notable biases include framing (the fact that you may change your opinion based on the way information is phrased), the sunk cost fallacy (our reluctance to give up on a failing investment even if we will lose more trying to sustain it), and the gambler’s fallacy—the belief that if the roulette wheel has landed on black, it’s more likely the next time to land on red. The probability, of course, stays exactly the same.

Given these findings, many cognitive scientists divide our thinking into two categories: “system 1,” intuitive, automatic, “fast thinking” that may be prey to unconscious biases; and “system 2,” “slow,” more analytical, deliberative thinking. According to this view—called dual- process theory—many of our irrational decisions come when we rely too heavily on system 1, allowing those biases to muddy our judgment.

It is difficult to overestimate the influence of this work, but none of the early studies by Kahneman and Tversky had tested whether our irrationality varies from person to person. Are some people more susceptible to these biases, while others are immune, for instance? And how do those tendencies relate to our general intelligence? Conan Doyle’s story is surprising because we intuitively expect more intelligent people, with their greater analytical minds, to act more rationally—but as Tversky and Kahneman had shown, our intuitions can be deceptive.

If we want to understand why smart people do dumb things, these are vital questions.

During a sabbatical at the University of Cambridge in 1991, a Canadian psychologist called Keith Stanovich decided to address these issues head on. With a wife specializing in learning difficulties, he had long been interested in the ways that some mental abilities may lag behind others, and he suspected that rationality would be no different. The result was an influential paper introducing the idea of dysrationalia as a direct parallel to other disorders like dyslexia and dyscalculia.

It was a provocative concept—aimed as a nudge in the ribs to all the researchers examining bias. “I wanted to jolt the field into realizing that it had been ignoring individual differences,” Stanovich told me.

Stanovich emphasizes that dysrationalia is not just limited to system 1 thinking. Even if we are reflective enough to detect when our intuitions are wrong, and override them, we may fail to use the right “mindware”—the knowledge and attitudes that should allow us to reason correctly. If you grow up among people who distrust scientists, for instance, you may develop a tendency to ignore empirical evidence, while putting your faith in unproven theories. Greater intelligence wouldn’t necessarily stop you forming those attitudes in the first place, and it is even possible that your greater capacity for learning might then cause you to accumulate more and more “facts” to support your views.

Stanovich has now spent more than two decades building on the concept of dysrationalia with a series of carefully controlled experiments.

To understand his results, we need some basic statistical theory. In psychology and other sciences, the relationship between two variables is usually expressed as a correlation coefficient between 0 and 1. A perfect correlation would have a value of 1—the two parameters would essentially be measuring the same thing; this is unrealistic for most studies of human health and behavior (which are determined by so many variables), but many scientists would consider a “moderate” correlation to lie between 0.4 and 0.59.

Using these measures, Stanovich found that the relationships between rationality and intelligence were generally very weak. SAT scores revealed a correlation of just 0.19 with measures of anchoring, for instance. Intelligence also appeared to play only a tiny role in the question of whether we are willing to delay immediate gratification for a greater reward in the future, or whether we prefer a smaller reward sooner —a tendency known as “temporal discounting.” In one test, the correlation with SAT scores was as small as 0.02. That’s an extraordinarily modest correlation for a trait that many might assume comes hand in hand with a greater analytical mind. The sunk cost bias also shows almost no relationship to SAT scores.

You might at least expect that more intelligent people could learn to recognize these flaws. In reality, most people assume that they are less vulnerable than other people, and this is equally true of the “smarter” participants. Indeed, in one set of experiments studying some of the classic cognitive biases, Stanovich found that people with higher SAT scores actually had a slightly larger “bias blind spot” than people who were less academically gifted. “Adults with more cognitive ability are aware of their intellectual status and expect to outperform others on most cognitive tasks,” Stanovich told me. “Because these cognitive biases are presented to them as essentially cognitive tasks, they expect to outperform on them as well.”

Stanovich has now refined and combined many of these measures into a single test, which is informally called the “rationality quotient.” He emphasizes that he does not wish to devalue intelligence tests—they “work quite well for what they do”—but to improve our understanding of these other cognitive skills that may also determine our decision making, and place them on an equal footing with the existing measures of cognitive ability.

“Our goal has always been to give the concept of rationality a fair hearing—almost as if it had been proposed prior to intelligence,” he wrote in his scholarly book on the subject. It is, he says, a “great irony” that the thinking skills explored in Kahneman’s Nobel Prize-winning work are still neglected in our most well-known assessment of cognitive ability.

After years of careful development and verification of the various sub-tests, the first iteration of the “Comprehensive Assessment of Rational Thinking” was published at the end of 2016. Besides measures of the common cognitive biases and heuristics, it also included probabilistic and statistical reasoning skills—such as the ability to assess risk—that could improve our rationality, and questionnaires concerning contaminated mindware such as anti-science attitudes.

For a taster, consider the following question, which aims to test the “belief bias.” Your task is to consider whether the conclusion follows logically, based only on the opening two premises.

All living things need water.

Roses need water.

Therefore, roses are living things.

What did you answer? According to Stanovich’s work, 70 percent of university students believe that this is a valid argument. But it isn’t, since the first premise only says that “all living things need water”—not that “all things that need water are living.”

If you still struggle to understand why that makes sense, compare it to the following statements:

All insects need oxygen.

Mice need oxygen.

Therefore mice are insects.

The logic of the two statements is exactly the same—but it is far easier to notice the flaw in the reasoning when the conclusion clashes with your existing knowledge. In the first example, however, you have to put aside your preconceptions and think, carefully and critically, about the specific statements at hand—to avoid thinking that the argument is right just because the conclusion makes sense with what you already know.

When combining all these sub-tests, Stanovich found that the overall correlation with commonly used measures of cognitive ability, was often moderate: on one batch of tests, the correlation coefficient with SATs was around 0.47, for instance. Some overlap was to be expected, especially given the fact that several of the rationality quotient’s measures, such as probabilistic reasoning, would be aided by mathematical ability and other aspects of cognition measured by academic tests. “But that still leaves enough room for the discrepancies between rationality and intelligence that lead to smart people acting foolishly,” Stanovich said. His findings fit with many other recent results showing that critical thinking and intelligence represent two distinct entities, and that those other measures of decision making can be useful predictors of real-world behaviors.

With further development, the rationality quotient could be used in recruitment to assess the quality of a potential employee’s decision making; Stanovich told me that he has already had significant interest from law firms, financial institutions, and executive headhunters.

Stanovich hopes his test may also be a useful tool to assess how students’ reasoning changes over a school or university course. “This, to me, would be one of the more exciting uses,” Stanovich said. With that data, you could then investigate which interventions are most successful at cultivating more rational thinking styles.

If we return to that séance in Atlantic City, Arthur Conan Doyle’s behavior would certainly seem to fit neatly with theories of dysrationalia. According to dual-process (fast/slow thinking) theories, this could just be down to cognitive miserliness. People who believe in the paranormal rely on their gut feelings and intuitions to think about the sources of their beliefs, rather than reasoning in an analytical, critical way.

This may be true for many people with vaguer, less well-defined beliefs, but there are some particular elements of Conan Doyle’s biography that suggest his behavior can’t be explained quite so simply. Often, it seemed as if he was using analytical reasoning from system 2 to rationalize his opinions and dismiss the evidence. Rather than thinking too little, he was thinking too much.

Psychologists call this “motivated reasoning”—a kind of emotionally charged thinking that leads us to demolish the evidence that questions our beliefs and build increasingly ornate arguments to justify them. This is a particular problem when a belief sits at the core of our identity, and in these circumstances greater intelligence and education may actually increase your foolish thinking. (This is similar to Stanovich’s concept of “contaminated mindware”—in which our brain has been infected by an irrational idea that then skews our later thinking.)

Consider people’s beliefs about issues such as climate change. Among Democrats, the pattern is exactly as you would hope: the more educated someone is, the more likely they are to endorse the scientific evidence that carbon emissions generated by humans are leading to global warming. Among Republicans, however, the exact opposite is true: the more educated someone is, the less likely they are to accept the scientific evidence.

This same polarization can be seen on many other charged issues, such as stem cell research or evolution and creationism, with more educated individuals applying their brainpower to protect their existing opinions, even when they disagree with the scientific consensus. It could also be observed in beliefs about certain political conspiracy theories. When it comes to certain tightly held beliefs, higher intelligence and knowledge is a tool for propaganda rather than truth seeking, amplifying our errors.

The unfortunate conclusion is that, even if you happen to be rational in general, it’s possible that you may still be prone to flawed reasoning on certain questions that matter most to you. Conan Doyle’s beliefs were certainly of this kind: spiritualism seems to have offered him enormous comfort throughout his life.

Following their increasingly public disagreement, Houdini lost all respect for Conan Doyle; he had started the friendship believing that the writer was an “intellectual giant” and ended it by writing that “one must be half-witted to believe some of these things.” But given what we now know about rationality, the very opposite may be true: only an intellectual giant could be capable of believing such things.

David Robson is a senior journalist at the BBC and author of The Intelligence Trap: Why Smart People Make Dumb Mistakes (WW Norton). He is @d_a_robson on Twitter. His website is www.davidrobson.me.

Excerpted from The Intelligence Trap: Why Smart People Make Dumb Mistakes. Copyright © 2019 by David Robson. Used with permission of the publisher, W. W. Norton & Company, Inc. All rights reserved.

Written By By David Robson

0 notes

Text

“في أي مهنة، يوجد الكثير من الأفراد منخفضي معدل الذكاء الذين يتفوقون على أشخاص ذوي معدل أعلى بكثير، كما يوجد أشخاص أكثر ذكاءً لا يحسنون استغلال مقدرتهم العقلية، ما يؤكد أن سمات مثل الإبداع والحكم المهني الحصيف لا يمكن أن تُعزَى إلى معدل الذكاء فحسب. «الأمر أشبه بأن تكون طويل القامة وتلعب كرة السلة»”

ديفيد روبسون | فخ الذكاء

#David Robson#The Intelligence Trap#ديفيد روبسون#فخ الذكاء#الذكاء#الإبداع#القدرات المهنية#اقتباس#اقتباسات#دراسة

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

❞ من الجلي أن المهارات التي تقيسها اختبارات الذكاء العام مكوِّن مهم من مكونات مقدرتنا العقلية، إذ تحكم مدى سرعة معالجتنا للمعلومات المجردة المعقدة وتعلمنا إياها. ولكننا إذا أردنا فهم المجموعة الكاملة لقدرات صنع القرار وحل المشكلات، فعلينا التوسع في نظرتنا لتشمل الكثير من العناصر الأخرى؛ أي مهارات التفكير وأساليبه التي لا ترتبط بالضرورة ارتباطًا قويًّا بمعدل الذكاء. ❝

ديفيد روبسون | فخ الذكاء

#David Robson#The Intelligence Trap#ديفيد روبسون#فخ الذكاء#الذكاء#المهارات#التفكير#اقتباس#دراسة#دراسات#مما قرأت

4 notes

·

View notes