#the hindu vocabulary today

Text

One of Aldous's major preoccupations was how to achieve self-transcendence while yet remaining a committed social being.

Julian Huxley, on his late brother.

Today (11/22/23) marks the sixtieth anniversary of the death of Aldous Huxley, author of Brave New World. Aldous Huxley was an interesting figure for many reasons, but it was this work, a work that warns of a future in which a combination of fetal manipulation and social conditioning conspire to cause people to "come to love their oppression," that has made him a household name.

A spirited spiritualist, Aldous Huxley had an interest in mysticism of all kinds, and it was this interest that brought him into contact with the Southern Californian Vedanta Society, which was founded by Swami Prabhavananda (who authored The Sermon on the Mount According to Vedanta). As a member of this society, Huxley wrote a series of articles that sought to explain spiritual principles and practical mysticism, using the vocabulary of the Christian and Vedantic Hindu traditions interchangeably. Among his more noteworthy works was his commentary on The Lord's Prayer, and an introduction to Prabhavananda's translation of the Bhagavad Gita.

Huxley's perspective on life has been referred to by at least one author as "Orientalized Christian," but a more accurate (and less offensive) label might be that of New Age. His opinions on mysticism and spirituality can be found in his book, The Perennial Philosophy, as well as the appendices of The Devils of Loudun. Huxley believed in the importance of the dignity of the individual, while at the same time fearing the effacement of individual identity through mob mentality. Some quotes for Aldous Huxley below:

"The end of human life cannot be achieved by the efforts of the unaided individual. What the individual can and must do is to make himself fit for contact with Reality and the reception of that grace by whose aid he will be enabled to achieve his true end. [...] We need grace in order to be able to live in such a way as to qualify ourselves to receive grace."

"First Shakespeare sonnets seem meaningless; first Bach fugues, a bore; first differential equations, sheer torture. But training changes the nature of our spiritual experiences. In due course, contact with an obscurely beautiful poem, an elaborate piece of counterpoint or of mathematical reasoning, causes us to feel direct intuitions of beauty and significance. It is the same in the moral world."

"Civilization demands from the individual devoted self-identification to the highest of human causes. But if this self-identification with what is human is not accompanied by a conscious and consistent effort to achieve upward self-transcendence into the universal life of the Spirit, the goods achieved will always be mingled with counterbalancing evils."

#Aldous Huxley#Christianity#Hinduism#Vedanta#spirituality#mysticism#New Age#grace#goodness#Holy Spirit#beauty

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Hindu Editorial Analysis : 28th September 2024

The Hindu Editorial Analysis

We understand the significance of reading The Hindu newspaper for enhancing reading skills, improving comprehension of passages, staying informed about current events, enhancing essay writing, and more, especially for banking aspirants who need to focus on editorials for vocabulary building. This article will delve into today’s editorial points along with practice…

0 notes

Text

Preparing for the Rajasthan Judicial Services Exam requires a thorough understanding of the syllabus. At Rajasthali Law Institute, we ensure that our students are well-versed in every aspect of the syllabus, which is divided into two main parts: Preliminary Examination and Main Examination, followed by an Interview. Here is a detailed breakdown of the syllabus for each stage:

Visit website

website : www.rajasthali.org.in

Preliminary Examination

The Preliminary Examination is an objective type test designed to screen candidates for the Main Examination. The syllabus includes:

Law:

Constitution of India

Code of Civil Procedure

Criminal Procedure Code

Evidence Act

Indian Penal Code

Contract Act

Partnership Act

Specific Relief Act

Limitation Act

Transfer of Property Act

Negotiable Instruments Act

Arbitration and Conciliation Act

Rajasthan Rent Control Act

Proficiency in Hindi and English Language:

Comprehension and grammar skills

Vocabulary and usage

Sentence structure

General Knowledge:

Current affairs

History and culture of Rajasthan

General science

Geography and economic developments

Main Examination

The Main Examination consists of descriptive type papers that test the candidate’s knowledge in-depth. It includes the following papers:

Law Paper-I:

Code of Civil Procedure

Law of Torts

Law of Contract and Specific Relief

Hindu Law

Muslim Law

Law Paper-II:

Evidence Act

Indian Penal Code

Criminal Procedure Code

Law of Judgments and Orders

Law of Arbitration and Conciliation

Law of Limitation

Language Paper-I (Hindi Essay, Grammar and Translation):

Essay writing

Grammar and usage

Translation from English to Hindi

Language Paper-II (English Essay, Grammar and Translation):

Essay writing

Grammar and usage

Translation from Hindi to English

Interview

Candidates who clear the Main Examination are called for an Interview. The Interview is designed to assess the candidate’s overall personality, aptitude, and suitability for a judicial role. It includes:

General awareness

Legal knowledge and understanding

Problem-solving ability

Communication skills

Ethical and moral values

Preparation Strategy at Rajasthali Law Institute

Detailed Study Materials:

Comprehensive notes and books covering the entire syllabus.

Regular updates on current legal developments.

Interactive Classes:

Expert faculty delivering lectures on each topic.

Interactive sessions for doubt clearing.

Practice Tests and Mock Exams:

Regular mock tests based on the exam pattern.

Detailed feedback and performance analysis.

Language Proficiency:

Special classes to enhance Hindi and English language skills.

Practice sessions for essay writing and translations.

Interview Preparation:

Mock interviews with experienced panelists.

Guidance on communication skills and personality development.

Enroll Today

Join Rajasthali Law Institute to get a structured and strategic preparation plan for the Rajasthan Judicial Services Exam. Our tailored coaching and extensive resources ensure that you are fully prepared to excel in every stage of the examination.

For more information and to enroll, visit our website or contact our admission office.

Contact Us:

Call:7665688999

website : www.rajasthali.org.in

0 notes

Text

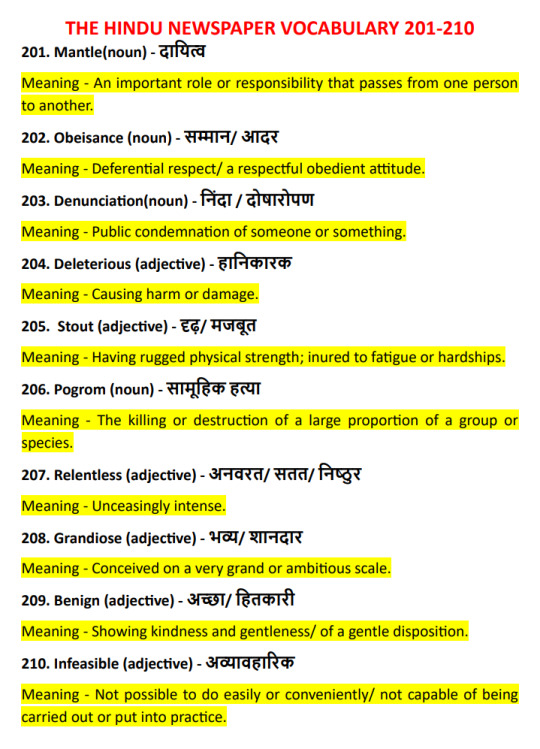

The Hindu Newspaper Vocabulary 201-210

The Hindu newspaper Vocabulary 201-210

Vocabulary play an important role in every competitive exams so you learn daily 10 new words. You can download PDF. Below Hindi meaning PDF download link available.

Today’s 10 words with Meaning , Synonyms, Antonyms, Verb forms and Example.

Download PDF

201. Mantle(noun)

Meaning – An important role or responsibility that passes from one person to…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

19TH C.'S POLITICS..LANGUAGE .

A shocking & eye-opening discussion on the huge ill-effects that Ram Mohan Roy (rightly lauded for his pioneering activism in helping rid Indian society of the hugely regressive dastardly age-old 'sati'/ widow self-immolation practice in Hindu culture), allegedly had on Indian civilization & culture, vis a vis his propagation of the replacement of Indian Sanskrit with British English, in early 1800s, which paved the way for the English language takeover of India, a decade later.

Was aghast that someone as visionary as Roy, could opine that Sanskrit, or any language, especially as ancient as that, from a land, famed for millennia on end, as being a intellectual-spiritual powerhouse, could 'stunt growth of scientific temperament' as apparently argued by Roy.

Most thoughtful people would agree, that the barometer for the self-sufficiency of a language, scientifically speaking, in sustaining a people, is it's vastness of emotion-to-word vehicle construct, in short, vocabulary. And there is nothing in history, that, all personal affinities & prejudices & general talent in it, aside, points to such inadequacy in the Sanskrit language perse.

The dangers of such abrupt singeing of India's oldest roots, that perhaps contributed to an extra century or so of 'easy' British colonization & re-indoctrination of India, especially with its basic & otherwise powerful vehicular foundations, taken away from under their feet, & so soiled in inferiority & mediocrity, being, the snatching away of, the 'ancient spiritual Indian ethos', created millennia back with the potential to absorb & digest more & more good & grow in sync with it's external surroundings WHILST NOT COMPROMISING ITS MOST FUNDAMENTAL DIVINE PRINCIPLE, in essence dismantling the bedrock for its oldest sustained existence & civilization.

To give more tangible success stories, from the 2 ancient lands, that contrary to India, didn't succumb to the colonial influence, whilst growing with the times, being China & Japan, who never allowed their own languages to be taken away in exchange for scientific vision, & in fact creatively used their ancient languages, modified & expanded them, to become even bigger scientific powers than the colonizers.

I challenge any language scholar, to prove that, Sanskrit,as an exception, didn't hold the vocab power, to allow for development of Scientific thot, within its aegis.

Sad, that such supposed greats(& in some context genuine heroes) of Indian history, could be now thot of, as a potential mass negative turning point for Indian life.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WRd0gngmFds

(On other allegation herein, namely, the mysterious superior "We are more Bengali(or Tamil) over Indians" attitude alleged to exist in West Bengalis-Bangladeshis & Tamilians-SriLankans, not allegedly the case btwn Ind & Pak Punjabis, that is a continually existing divisive force..a sufficient counter-argument is- Bangladesh was birthed with Indian support as good friend, & SL always India's oldest good neighbor, so that bond is most definitely not a divisive 'anti-nation' rather a 'beyond nation' bond. Moreover, Pakistan was birthed with Ind as enemy. And despite it, that they can keep their natural apparent cultural similarities with enuf respect as glue till today, further proves these bonds to be a positive life force for all) .

1 note

·

View note

Photo

“Quasi-religious forms of physical culture swept Europe during the nineteenth century and found their way to India, where they informed and infiltrated popular new interpretations of nationalist Hinduism. Experiments to define the particular nature of Indian physical culture led to the reinvention of asana as the timeless expression of Hindu exercise. Western physical culture-oriented asana practices, developed in India, subsequently found their way (back) to the West, where they became identified and merged with forms of "esoteric gymnastics," which had grown popular in Europe and America from the mid-nineteenth century (independent of any contact with yoga traditions). Posture-based yoga as we know it today is the result of a dialogical exchange between para-religious, modern body culture techniques developed in the West and the various discourses of "modern" Hindu yoga that emerged from the time of Vivekananda onward. Although it routinely appeals to the tradition of Indian hatha yoga, contemporary posture-based yoga cannot really be considered a direct successor of this tradition.”

“For example, the claim that specific gymnastic asana sequences taught by certain postural schools popular in the West today are enumerated in the Yaiur and g Vedas is simply untenable from a historical or philological point of view. This claim is made by K. Pattabhi Jois about the süryanamaskar sequences in his Ashtanga Vinyasa system (see note 4 in chapter 9).& Assertions such as this are made with some frequency in popular yoga discourse, and there is no question of accepting them as statements of historical or philological fact. However, the practices themselves cannot be written off as lacking interest or validity merely on the grounds of their late accession to the postural vocabulary of yoga or because of their divergence from the "traditional yoga" invoked on their behalf.”

“I am well aware on the basis of several years of presentations and informal discussions on the material presented here--that my work will elicit some very specific reactions in certain quarters. For those who prefer hagiography to history, such as some Western apologists of "traditional" systems of postural modern yoga, this work is easily dismissed as either irrelevant or malign in intent, and its author as an academic trespasser on hallowed ground. Others, who situate themselves in an antagonistic relationship to the authority of modern traditions (or who are angry about what "has been done" to yoga), revel in what they see as a much needed exposure of convenient but specious myths. Both these responses are based on the assumption that my intention is to "demolish" the validity of modern yoga or to show that the postural forms that abound today are "bastardized," "compromised," "watered down," "confected" (and so on) with regard to the true meaning and authentic practice of yoga. Both responses, however, aside from misrepresenting my position, are inadequate and undesirable as they stifle genuine and sustained thinking about the substance of modern yoga. While there seems little point in protesting that this material is not presented through love of controversy or iconoclasm on my part, it is worth suggesting that there may be more profitable ways to view this book than as a hostile but ultimately irrelevant academic exercise on the one hand, or a righteous destruction of false idols on the other. A more valid and helpful way of thinking beyond such unproductive positions might be to consider the term yoga as it refers to modern postural practice as a homonym, and not a synonym, of the "yoga" associated with the philosophical system of Patanjali, or the "yoga" that forms an integral component of the Saiva Tantras, or the "yoga" of the Bhagavad Gita”

“While there are references to tapps practicing ascetics (called muni, resin or vratya)

as early as the vedic Brahmanas, the first occurence of the word; "yoga' is itseltf in the katha Upanisad (third century BCE), where it is revealed to the; boy Nacketas by Yama, god of death, as a means to leave behind joy and sorrow and overcome death itself. The Svetasvatara Upanisad (third century BCE) further outlines a procedure in which the body is maintained in an upright,

posture while the mind is brought under control by the restraint of the breath. The much later Maitri Upanisad describes a sixfold yoga method of yoga, namely (1) breath control (pranáyama), (2) withdrawal of the sense, (pratyahara), (3) meditation (dhyána), (4) placing of the concentrated mind (dharana), (5) philosophical inquiry (tarka), and (6) absorption (samadhi). These technical terms will later (with the exception of tarka) be used to designate five of the eight elements of Patanjali's astángayoga scheme. The section of the Mahabharata known as the Bhagavad Gita lays out three paths of yoga by which the aspirant can know the Lord, or supreme person, here

known as Krsna. The first is the path of action (karmayoga), in which one gives up the fruits of one's actions but continues to be an agent in the world, guided by Krsna himself? The second is the path of devotion (bhaktiyoga), in which one's devotion to Krsna swiftly liberates one from worldly suffering, regardlessof caste.The third is the path of knowledge (janayoga), which liberates through discrimination of the true nature of self and universe.4 The Gità also describes a range of practices undertaken by yogins of the day (such as an internalization of the vedic ritual, as in the sacrifice of the inhalation (prana) into the exhalation (apana) (26 [4): 22-31), as well as instructions for the preparation of a yoga sadhana and for the withdrawal of the senses (28 [6]: 1-29). The Yogasütras (VS, C. 250 CE?) ascribed to Patañjali consist of 195 brief aphorisms (sutrani) outlining diverse methods for the attainment of yoga. It is heavily influenced by Sämkhya philosophy (Larson 1989, 1999; Bronkhors! 1961), but also contains distinct elements from Buddhism® and a variety of Sramana (renunciant ascetic) traditions.& The Yogasütrabhagya attributed i°

Vasa (6. 500-600 cF), is the first and most influential commentary on the tell and is sometimes even regarded as a component part of the YS itself. Although the text has received an enormous amount of interest from modern scholars, even coming to be known as the "Classical Yoga.

beetle mind that it is one among many texts on yoga and may not necessarily be the authoritative source for Indian yoga traditions, as is commonly supposed. It has become the primary text for anglophone yoga practitioners in the twentieth century, largely due to the influence of European scholarship on the one hand, and early promoters of practical yoga like Vivekananda”

“In spite of the scarcity of information regarding asana in the sutras themselves and in the traditional commentaries, the text is routinely invoked as the source and authority of modern postural yoga practice (e.g., lyengar 1993a; Maehle 2006). This is in no small measure due to the authority and prestige that the association with Patañjali confers on modern schools of yoga and their prac- tices. Although I do not deal with it at any length in the present study, it is clear that the refurbishment of Patanjali in the modern era is one of the key loci of transnational yoga's development (see Singleton 2008a). Saiva Tantras and other Agamic compendia often contain detailed descrip- tions of yoga practice. For example, the Vijnanabhairava, an eighth-century cE collection from the Saivâgama, contains 112 types of yoga aiming at the union of the aspirant with Siva (cf. Singh 1979). Or we find the yogic teachings from the Malinivijayottaratantra, a Tantra of the Trika division of Saivism, which "attempts to integrate a whole plethora of competing yoga systems," the common feature of which is that they all require the yogin "to traverse a 'path' (adhvan) towards a goal' (laksya)" (Vasudeva 2004: xi-xii).? In all the systems of yoga mentioned here, not much emphasis is placed on the practice of ásana. Even early Tantric works such as that examined by Vasudeva teach only a small number of seated postures (Vasudeva 2004: 397-402). Any assertion that transnational postural yoga is of a piece with the dominant orthopraxy of Indian yogic tradition is there- fore highly questionable.”

“The earliest of the well-known texts of hatha yoga is probably Goraksa Satako (G5), ascribed to Goraksanätha, followed by Siva Samhità (5S, fifteenth century E), Hathayogapradipikà (HYP, fifteenth-sixteenth century), Hatharatnävali (HP seventeenth century), Gheranda Sarnhità (GhS, seventeenth-eighteenth century CE), and the Jogapradipakà (P, eighteenth century).' As Bouy (1994) has shown. hatha yoga techniques aroused much interest among the followers of Sankara's advaita vedanta, and a number of texts from Näth literature were assimilated wholesale into the corpus of 108 Upanisads compiled in South India during the first half of the eighteenth century. 10 Mallinson (2007: 10) has demonstrated that the orthodox vedantin bias of these compilers resulted in the omission of some key aspects of Näth hatha yoga, such as the practice of khecarimudra." As we shall see, a similar process of omission occurred during the modern hatha yoga revival. Since many of the asana systems considered in this study purport to derive from, or to be, hatha yoga, a brief examination of the main features of its doctrines and practices is in order. This account is drawn mainly from HYP, Ghs, and Ss, which are the hatha yoga texts best known to English language readers. Hatha yoga is concerned with the transmutation of the human body into a vessel immune from mortal decay. GhS compares the body to an unbaked earth enware pot which must be baked in the fires of yoga to purify it and even refers to this system as the "yoga of the pot" (ghatasthayoga) rather than hatha yoga." A preliminary stage of the hatha discipline is the six purifications (satkarmash. which are (with some variation between texts) (1) dhauti, or the cleansing ofthe stomach by means of swallowing a long, narrow strip of cloth: (2) basti, or "yogl enema" effected by sucking water into the colon by means of an abdomina vacuum technique (uddliyana bandha); (3) neti, or the cleaning of the nasal pose "Jafes with water and/or cloth; (4) trataka, or staring at a small mark or candle "until the eyes water; (5) nauli or laulik, in which the abdomen is massaged by forcibly moving the rectus abdominus muscles in a circular motion; and (6) kapdlabhai, where air is repeatedly and forcefully expelled via the nose by contraction o the abdominal muscles.”

“The HYP names asana as the first accessory (anga) of hatha yoga and lists its benefits as the attainment of steadiness (sthairya), freedom from disease (ärogya), and lightness of body (añgalaghava) (1.19). The text outlines fifteen asanas, some of which are credited with curative properties, such as destroying poisons (e.g., mayürásana, 1.33). The ChS places the asanas after the purifica- tions, and briefly describes thirty-two of them. The SS mentions that there are eighty-four asanas, but describes only four seated postures. The mainstay of hatha practice is pranayama (also called kumbhaka, or "retention," in HYP). Pranâyama cleanses and balances the subtle channels of the body (nädi) and in combination with certain bodily "seals," or mudrãs, 13 forces the prana (vital air) into the central channel called susumnã or brahmanadi. This in turn raises the kundalini energy, which is visualized as a serpent sleeping at the base of the spine.”

“Modern medical hatha yoga as initiated by the likes of NC Paul, Major D. Basu and some decades later Swami Kuvalavananda (1883 -1956) and Shri Yozent, (1897-1989), is deeply concerned with this subtle physiology,! and New Ag. books about the spiritual anatomy of the cakras (such as the current best. selling works of Caroline Myss) continue to draw readers even today. our essentialy their application to modern forms of yoga is limited to a general recognition of the three principal nadis, the cakras, and the role that these may play in kundalini type experiences. While such references are commonly e be found in popular texts fashionable in yoga circles and in practitioners imo, inaire, the larger theories and related practices are usually kept to a minimum, and only occasionally are they encountered in actual yoga teaching and practice Indeed, the average anglophone yoga class today is far more likely to foreground the sole practice of asana and largely ignore the subtle system of hatha yoga. Student yoga teachers commonly learn something about nädis and cakras during their training, and many will read a modern commentary and translation of HYp but it is rare for this theoretical knowledge to be applied as part of a hatha yoga practice such as that outlined in the traditional texts or that described by Theos Bernard during his experience of a traditional hatha sadhana in India (Bernard 1950). Tibetan systems of physical yoga from the Bön and Buddhist Vajrayana traditions, which have recently begun to be taught in the West and which bear a close affinity to hatha yoga, are far more likely to retain an emphasis on the subtle physiology of the body and on practices that work with this body (Chaoul 2007). These Tibetan techniques highlight the extent to which transnational, Indian haha yoga has become decontextualized from the system it claims to repre sent! In sum, the Indian tradition shows no evidence for the kind of posture based practices that dominate transnational anglophone yoga today.”

“The practice of asanas within transnational anglophone yogas is not the outcome of a direct and unbroken lineage of hatha yoga. While it is going too far to say that modern postural yoga has no relationship to asana practice within the Indian tradition, this relationship is one of radical innovation and experimentation. It is the result of adaptation to new discourses of the body that resulted from India's encounter with modernity.”

“In his "Prize Essay on the Hindu System of Medicine," published in the Guy's Hospital Gazette (London) in 188g and cited in Vasu's 1915 foreword to the 5S, Major Basu asserts- in what is one of the very first public and international claims of tantric yoga's scientific, medical status- that "better anatomy is given in the Tantras than in the medical works of the Hindus" (Vasu 1915: i). According to him, the siva Samhità gives "a description of the several ganglia and plexuses of the nervous system" (i) and is proof that the Hindus were acquainted with the spinal cord, brain, and central nervous system. In this essay, and in a paper on the "Anatomy of the Tantras" published a year earlier in the Theosophist (March 1888), Basu commenced a mapping of tantric body symbolism onto Westen anatomy that would keep the later pioneers of "scientific" hatha yogic phenom end occupied for many decades to come. Kuvalayananda himself, indeed, identified Basu's Theosophist article as "the oldest attempt in the direction df scentially interpreting the Yogic anatomy" (1935: 3). It is here, perhaps, l) for the first time a "scientific" attempt is made to identify the Nads, Chalt, and Radiast of hathe yoga with the conduits of the spine and the plexuses of the anatomical body- an identification that is still pervasive in popular transnational hatha yoga today. Captain Basu's enquiry is based on the eminent empirical, rationalistic question, *Are the padmas and anekras real, or do lie, the rots es the imagination of the Tantrists?”

“Basu professes, "we nevertheless believe that the Tantrists obtained their knowledge about them by dissection" (il). Contrary to Basu's assertion, we should note, there is no evidence whatever that "Tantrists," or any other religious group in India, ever engaged in the dis- section of corpses. In fact, the first dissection by a Hindu was probably under. taken in 1836 by Madhusüdana Gupta in Calcutta (Wujastyk 2002: 74). As Bharati writes, "Ancient Indians never opened up dead bodies to study organs empirically.... The horror of defilement and ritual pollution was so strong in India that anatomical and physiological experimentation seemed until recently out of the question" (1976: 165). As far back as 1670, indeed, Bernier had noted the same horror among Indians with regard to anatomical dissection (1968 (1670): 339). Basu's claim should therefore be understood as a projection of the scientific present onto the screen of tradition and as an expression of the mod- ern need to view the hatha yogic body as anatomical and "real." It is this need that forms the impetus and rationale for the hatha experimentation of the twen- tieth century. This point can be illustrated further by a (possibly apocryphal) anecdote from the life of Hindu firebrand and founder of the Arya Samaj, Dayananda Saraswati (1824-1883). On a tour of India in 1855, Dayananda pulls a corpse from the river and dissects it to ascertain the truth of the tantric cakras he has been reading about. When his search fails, he scornfully tosses his yogic texts (including the Hatha Yoga Pradipika) into the water (Yadav 2003 (1976): 46). His experiment leads him to "the conclusion that with the exception of the Vedas, Patanjali and Sankhya all other works on the science of yoga are false" (Yadav 2003 [1976]: 41). While Basu's optimism and Dayananada's pessimism regarding the truth-value of hatha yogic texts are clearly at odds, they nonetheless have in common that they enthrone rational empiricism as monarch in the kingdom of yoga.”

“the kind of thinking that prompts Dayananda to undertake his dissection and which also lies behind Basu's project to find cakras in plexuses, is based on the notion that the world is one and that the traditional and modern explanations of it are both true and can be made to coincide”

“Geoffrey Samuel notes with regard to Tibetan medicine's encounter with the West that only those elements that can be readily assimilated into a material- ist epistemology are retained, while those that do not "fit" are forgotten or rejected (Samuel 2006). It is clear that similar forces are at work in anglophone hatha yoga as it negotiates its way into the Western scientific paradigm. That today some fourteen million Americans are recommended yoga by their thera- pist or doctor (Yoga Journal 2008) is in many respects a late consequence of yoga's assimilation into medical science that began in the mid-nineteenth century.”

“it is easy to see how the ásanas of hatha yoga would readily have been interpreted by readers as the Indian equiva- lent of Western sideshow contortionist routines. The increasing numbers and high profile of yogin-entertainers in India from the mid-800s onward also con. tributed to such interpretations. There is a clear, circumscribed vocabulary of postural forms both within the posture-master tradition and among later performers such as those depicted in The Strand. Many of the most common positions are a perfect match with the advanced postures of popular postural yoga today, coincidences that may be at least partially due to the structure and limitations of the human body itself. As Elkins remarks, "despite whatever meanings are elided by the fantasy of bone- lessness, it won't be possible to evade the basic possibilities of the normal body" (Elkins 1999: 105). While the apparent similarities between modern yoga pos- tures and contortionist turns are to some degree a function of these basic pos- sibilities, they remain nonetheless suggestive. The most frequently occurring postures are, to use lyengar's 1966 nomenclature, gandabherundásana, natarajasana, hanumanasana, tittibhasana, samakonasana, and padängustha dhanurasana. For instance, the postures in Faux's advertisement in the figure above correspond (left to right) to urdhvadhanurasana, adhomukhavrksasana, and gandabherundasana in lyengar's nomenclature (1966). As further visual evi- dence of this formal proximity, I include here a photo-montage of standard Western contortionist poses from the late nineteenth century alongside some advanced asana performed by B. K. S. lyengar himself. I point out these similarities not to suggest any causal link between the pos- tural forms of the Western sideshow contortionist and the asanas of modern postural yoga but to further emphasize the strong associations that extreme postural forms, such as those demonstrated by Dass, would have naturally had in the European (and American) psyche.”

“To a large extent, popular postural yoga came into being in the first half of the twentieth century as a hybridized product of colonial India's dialogical encoun- ter with the worldwide physical culture movement. The forms of physical prac- tice that predominate in popular international yoga today were developed in a climate of intense experimentation and research around a suitable regimen for Indian bodies and minds. "Yoga," foregrounded in certain quarters as the epit- ome of Hindu physical culture, became one of the names of this new national physical culture. The launching of the popular physical culture self-instruction genre and the staging of the first modern Olympics coincide chronologically with the appearance of Vivekananda's Raja Yoga (1896), which ushered in a new phase of yoga's long history (De Michelis 2004). Moreover, the first ever mod- ern bodybuilding display took place on August 1, 1893 (Dutton 1995: 9), the very day that Vivekananda himself arrived on Western soil. Transnational anglophone yoga was born at the peak of an unprecedented enthusiasm for physical culture, and the meaning of yoga itself would not remain unaltered by the encounter. As a vital contextual prelude to our examination of modern postural yoga”

“Norman Sjoman argues, "the therapeutic cause-effect relation (of asana] is a later superimposition on what was originally a spiritual discipline only (1996: 48).3 While we might well take issue with Sjoman's notion of "spiritual only" here, it is true that in the twentieth century individual yoga postures came to be explicitly associated with the cure of particular conditions.”

“Sandow's trip to India "indicated the politically subversive potential of phys- ical culture as well as its inherent malleability" (Bud 1997: 85) in that his meth- ods were transformed into tools for independence. In the hands of nationalist leaders such as Sarala Debi (see below) physical culture such as that popular- ized by Sandow "was not considered inherently or uniquely Western, but as separated from its user, and capable of serving any master" (85). It could be used, in other words, both as a symbolic rebuttal of colonial degeneracy narra- lives and-at times--as an underpinning for violent, forcible resistance. Sandow's thetoric was shot through with notions of exercise as religious prac- lice, which made it all the more compatible with Indian nationalistic fusions of *religion and bodybuilding”

“At the time--as Gray declares of physical education in general- there simply was no "system" or "brand" of physicalized yoga that could satisfactorily meet India's need. This had to be created out of what was available, including a large number of exercises that had not hitherto been considered part of yoga (most significantly, nature cure, therapeutic gymnastics, callisthenics, and bodybuilding). When India built "her own programme" of physical culture, one of the names she gave it was “yoga." “

This sense of physical and racial degradation was in large part the result of a stereotype promulgated by the colonial powers and internalized by Indians themselves, often via the anglicized education system. One function of this myth of Indian effeminacy was to justify in the minds of the colonizers contin- ed British subjugation. Baden-Powell, the founder of the international scout movement, considered the task of colonial education in India as "that great work of developing the bodies, the character and the souls of an otherwise feeble people" (Sen 2004: 94). His view is typical of the British conviction of the physi- cal, moral, and spiritual inferiority of Indians, as judged against the idealized masculine body and perfect conduct of the English gentleman. The "degeneracy narrative" in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries served as "an explana- tion of otherness, securing the identity of, variously, the scientist, (white) man, bourgeoisie against superstition, fiction, darkness, femininity, the masses, effete aristocracy” (Pick 1989: 230), and here it is applied by a renowned advocate of colonial man-making as an account of the otherness of the very humanity he seeks to reform.”

“The dire diagnostics of the Western bodybuilding mandarins appeared to be addressed directly to Indians: not only were their bodies weak, but "physical effeteness seemed often a mere index of spiritual downfall" (Rosselli 1980: 125). The twin myths of physical degeneration and prelapsarian vigor were used as goads by Hindu nationalist leaders and physical culture revivalists alike. The struggle to define an Indian form of body discipline was rendered ambiva- lent by the adoption of certain core ideological values of a Western, and ultimately imperialist, discourse on manliness and the body. The akhara and the Hindu melä worked alongside (and sometimes squarely within) the current of colonial educa- tion reform and "indigenous" physical culture movements maintained a permea- bility to Western influence, based on a deep appreciation of the cultural and political potential of the nationalistic gymnastic movements of Europe. Indeed, even in the schools and gurukuls of the Arya Samaj, that most ardently "swadeshi" of the Indian Samajs and "perhaps the greatest indigenous educational agency" (Rai 1967: 145), the students would arise before dawn and immediately perform "'umbbell exercises and calisthenics" (145), a regime clearly borrowed from the methods of physical culture in vogue in Europe at the time and widely dissemi- haled throughout India.? It was through experiments such as these that physical culture became " a central part of the educational programme" in India (Watt 1997: 361. Physically fit, healthy citizens of good character dedicating themselves to the betterment of Mother India thereby became "important symbols of a strong and vibrant nation in an age when Hindus felt that they lacked'manliness, were weak; "lacking in courage;' were a 'lethargic race' “

“If we are to give credence to his historical assessment of the process, yoga as physical culture would have entered the sociocultural vocabulary of India partly as a specific signifier of violent, physical resistance to British rule. To "do yoga" or to be a yogi in this sense meant to train oneself as a guerrilla, using whichever martial and body strengthening techniques were to hand, and it is thus that the yoga tradh ton itself, as Rosselli puts it, "could be used to underwrite both violence and non-violence” (1980: 147). Furthermore, the long list of Indian and Western, methods acquired under Manick Rao indicates at once the proliferation of exercise activities within this milieu and the ease with which they could be combined, under the heading of yoga. It is clear that the "canon" of modern ásana that we know today was still very much in a state of flux”

“Nile Green argues with regard to meditation that such modernized culture, of self discipline "cannot be disentangled from colonial efforts towards taming the violence of the holy man”

“For Yogendra, yoga exercises “have all the merits of medical and preventive gymnastics” (1989 [1928]: 162). His self-pro- claimed “yoga renaissance” (see De Michelis 2004: xvii) should be understood as in large measure a holistic and scientific system of movement cure, conceived within the context of the modern “renaissance of gymnastics” (Dixon and McIntosh 1957: 92) but proclaimed as a uniquely indigenous Indian therapy— more ancient and effective than the European styles that had been imposed as the standard form of exercise in India during the nineteenth century. Yogendra yogic teleology, like so much physical culture and modern yoga writing of this period, also manifests the influence of Social Darwinist and eugenic thought (see “Physical Culture as Eugenics” in chapter 5). The “technol- ogy of Yoga” functions for Yogendra as a fillip toward higher states of “physical, mental, moral and psychic” development which “the slow process of evolution” tarries in attaining (1978: 28).4 Yogendra terms this process śıḡ hramokṣasyahetuḥ, literally “the cause of swift liberation.” That he equates mokṣa with the evolution- ary project of “modern science” and eugenics shows the extent to which his vision of yoga diverges from “classical” yogic conceptions of liberation.

Similarly, Yogendra shares what is by then a fairly widespread belief that “the very concept of evolution originated and developed with (Sāṃkhya) Yoga” (1978: 27). While his committed populism would make it unlikely for him to partake of the racial exclusivism of many eugenicists of the time, Yogendra is nonetheless fascinated by the prospect of human genetic modification through yoga. As a materialist who from a very early age distrusted the magical elements of traditional yoga, his version of yoga eugenics remains rooted in the physical and biological. For Yogendra, as for Nietzsche, Darwin’s stately vision of prog- ress through the ages is not sufficient. Natural evolution, lamentably, does not alter the “germ plasm” determining a man’s hereditary disposition, but through the project “contemplated by yoga” this substance can be modified to produce a “permanent germinal change” (1978: 29). Such a transformation effects not only the yoga practitioner himself “but by inheritance also becomes transmitted as the germinal instinct (propensity) of the progeny” (29). It is this transforma- tive technology, he asserts, that is “the crux of the entire metaphysical perspec- tive in ancient India” (29).

Yogendra here revives the Lamarckian dream of acquired, transmittable characteristics and imbues it with the mystical landscape of ancient India. This yogic neo-Lamarckism would seem to be a rejoinder to the influential germ plasm theory of the embryologist August Weismann (1834–1914) which had effectively discredited Lamarck’s apparently simplistic cause-effect model of heredity. Weismann had asserted that “the force of heredity resided in a substance imper- meable to environmental influence”

“Day-to-day activities at lyer's gymnasium, as well as the popular correspon. dence courses, were the practical expression of this "blending of the two Systems" of physical culture and yoga (lyer 1930: 43), offering an integral regime of süryanamaskär (salutations to the sun), "yoga" as medical gymnastics and body-conditioning on the one hand, and state of the art dumbbell work and freehand European bodybuilding techniques on the other. lyer was not the first to use suryanamaskär as part of a bodybuilding Regimen. The creator of the modern suryanamaskar system, Pratinidhi Pant, the Rajah of Aundh, was him- self, like lyer, a devoted bodybuilder and practitioner of the Sandow method, and he went on to definitively popularize the dynamic sequences of asanas that have become a staple of many postural yoga classes today. As Pant writes in his manual of the süryanamaskär method: "In 1897….. we purchased all [Sandow's] apparatus and books, and for fully ten years practised regularly and continu- ously according to his instructions" (Pratinidhi and Morgan 1938: 90). Süryanamaskär, today fully naturalized in international yoga milieux as a pre- sumed "traditional" technique of Indian yoga, was first conceived by a body. builder and then popularized by other bodybuilders, like lyer and his followers, as a technique of bodybuilding (see Goldberg 2006, forthcoming). Let us stress, however, that at this time, for Pratinidhi, lyer, and those who practiced and taught their techniques, suryanamaskär was not yet considered a part of yoga.”

“Originally a breakaway faction of Mary Eddy Baker's Christian Science, New Thought began in New England in the 1880s as a broad-based, para-Protestant movement preaching the innate divinity of the self and the power of positive thinking to actuate that divinity in the world, usually to the ends of personal affluence and health. It is no exaggeration to say that elements of these popular esoteric doctrines are so uniformly present in practical yoga primers intended for the European and American reading public that it Is unusual not to find some degree of blending during the first half of the twenti eth century. It seems to have been widely taken for granted that positive think ling, auto-suggestion, and the "harmonial," this- worldly belief framework of New Thought was not so much a contribution to yoga as its expression (albel in optimistic, Americanized accents). Conversely, it was largely assumed that 1082 was the perennial, exotic repository of these newly (re-)discovered truths”

“For Payot, as for later New Thoughters, the body held the secret of spiri- tual advancement, and it was through developing the "healthy animal" (247) that the god in man would be revealed. The "physiological conditions of self-masterj" (247) were to be attained through a regime of muscular exercise and "respiratory gymnastics" (259) that would function as "a primary school for the will" (265). Payot's ideas and methods were taken up by the New Thought movement (Griffith 2001) and developed in the writings of such figures as Frank Channing Haddock, whose "Power Book Library" series represents a momentous event in twentieth-century New Thought history. Haddock draws heavily on Payot's work in his Power of the Will of 1909. The physical exercises he describes therein are based, as for Payot, on the exertion of the will-not for physical gains but for the training of the will itself and for the moral and spiritual benefit to be derived from this training. During the exercises, one repeatedly affirms "I am receiving helpful forces!... Streams of power for body and mind are flowing in!" (Haddock 1909: 162). One should send such affirmations into the body itself-_-rather than outward toward the cosmos-_and "throw" the thought "into the limbs”

“Gherwal notes that "one of the outstanding features of the Twentieth Century mode of scientific muscular exercise is that this most valuable will power or soul power is roused, disciplined and developed to an enviable degree," such that "physical culture comes to be studied from the Yogic point of view (40). In effect, it is the converse that occurs: yoga comes to be considered as an

Eastern variant of New Thought physical culture. Gherwal's manual is steeped in the rationale of the New Thought mode of physical culture, even down to the admiration for the "auto-suggestions imparted to the muscles and physical tissues" (1923: 44) so favored by Haddock and other New Thought luminaries”

“Indeed, the same socioeconomic group of white, mainly Protestant women who lauded Vivekananda and enthusiastically took up the practice of yoga in their own homes (Syman 2003) was also dabbling in mystical dance. It was these women's endorsement of Vivekananda's yoga (which, as De Michelis 2004 has demonstrated, fed back to them a version of their very own

esoteric convictions) which was instrumental in establishing Vivekananda as an authoritative spiritual and political voice in his homeland.”

“Perceived as dissolute, licentious, and profane, these groups were greeted with puzzlement and hostility by early European observers. The performance of yogic postural austerities was the most visible and vaunted emblem of Indian religious folly, and as yogins increasingly took to exhibitionism as a means of livelihood, this association became consolidated in the popular imagination.’

“What seems clear is that the breathing, stretching, and relaxation classes attended every week by thousands of twenty-first-century Londoners as yoga recapitulate the spiritualized gymnastics undertaken by their grandmothers and great-grandmothers in the 1930s. There can be no doubt that Stack's incorpora ton of asanas into a combined program of dynamic stretches, rhythmic breath. ing, and relaxation within a "harmonial" context closely mirrors the creative modulations of many of today's "hatha yoga" classes. As already noted, the term "hatha yoga" is routinely used among London's postural yoga teachers and practitioners today to indicate a generic, nondenominational, and eclectic sys- tem of gentle postural practice and to distinguish it from "named" brands like lyengar, Ashtanga, or Sivananda. Postural yoga teachers who profess to teach "hatha yoga" will usually creatively combine postures, sometimes in flowing sequences, and invent poses of their own (a far less common occurrence in the "branded" forms like lyengar). As contemporary posture teacher Dharma Mitra puts it, "even today dozens of new poses are created each year by true yogis all over the world" (2003: 13). A compelling explanation of the often radical dissimi:- larity of such systems from "classical" hatha yoga is that they stem, to a large extent, from "modern traditions" such as Stack’s.”

“linsofar as this gendered format of modern sports and gymnastics has been transmitted into international hatha yoga in the twentieth century, we can dir ferentiate between masculinized forms of postural yoga issuing from a "muscu lar Christian," nationalistic, and martial context (see chapters 4 and g), and harmonial "stretch and relax varieties of postural yoga stemming from the sup. thesis of women's gymnastics and para-Christian mysticism. The former group, which foregrounds strength, classical ideals of manliness, and (often) the relil gio-patriotic cultivation of brawn, is exemplified by bodybuilders such as her and Ghosh, freedom-fighting yogis such as Tiruka, the early (pre-Pondicher) Aurobindo, and Manick Rao. It is also the dominant form in certain present-day "militant" yoga regimes, such as those of the Hindu cultural nationalist organi- zation, the RSS (see Alter 1994; McDonald 1999). On the other hand, gentler stretching, deep breathing, and "spiritual" relar- ation colloquially known in the West today as "hatha yoga" are best exemplifed by the variants of harmonial gymnastics developed by Stebbins, Payson Cal. Cajzoran Ali, Stack, and others--as well as the stretching regimes of secur women's physical culture with which they overlap. In practice, however,this* best a heuristic division, since postural modern yoga forms rarely fit excusie/ into one category or the other. It does, however, furnish a frameworkforthin through the influences behind varieties of postural styles at large today.”

“My intention in this chapter has been to demonstrate that there were firmly established exercise traditions in the West that included forms and modes of practice virtually indistinguishable from certain variants of "hatha yoga" now popularly taught in America and Europe. As a result, the sheer number of positions and movements that could be henceforth classified as asana swelled considerably and continues to do so. For example, both Bühnemann (2007a) and Sjoman (1996) point out the absence of standing postures in premodern ásana descriptions. The overlap of standing asanas and modern gymnastics is extensive enough to suggest that virtually all of them are late additions to the yoga canon through postural yoga's dialogical relationship with modern physi- cal culture. The same hypothesis extends beyond the standing poses to the mul- titude of apparently new ásana forms. Jan Todd argues that "woven throughout the multitude of exercise prescrip- tions for twentieth-century women can be found most of the basic principles of early nineteenth-century purposive training (i.e., health and fitness regimes)" (Todd 1998: 295).”

“The phenomenon of international posture-based yoga would not have occurred without the rapid expansion of print technology and the cheap, ready availability of photography. Furthermore, yoga's expression through such media funda- mentally changed the perception of the yoga body and the perceived function of yoga practice. These propositions rest on the assumption that photography land the text that accompanies it) is by no means an objective medium reflect- ing what is simply "there" but an active structuring process through which soci- ety and "reality" are themselves endowed with meaning (Barthes and Howard 1981; Burgin, 1982). They are based also on the observation that postural yoga came fully into the public eye only when it was visually represented, most signifi- cantly through photography. I take this chronological coincidence less as a pro. cess of post factum documentation (i.e., a "transparent" setting down in images of what was already there) than as a bringing forth of the modern yoga body. Technologies are never simply inventions people use but means by which they- and their bodies-_are reinvented”

“Pultz argues that photography stands as the very metonym of the empiri- cally driven Enlightenment, which prized sensory evidence as the principal means of understanding human reality. Photography represented "the perfect Enlightenment tool, functioning like human sight to offer empirical knowledge mechanically, objectively, without thought or emotion" (1995: 8). Through pho- tography the world was captured and laid flat, readied for inspection and clas. sification. The popularizationofphotography-andin particular, portraiture--also brought about a revolution in social consciousness, with a whole generation of people seeing, often for the first time, pictorial representations of their own bod- ies (13). Such images, argues Pultz, radically altered the status of the human body within society and brought a self-conscious, self-observing, and corpore- ally aware European middle class into existence (17). It is important to remem- ber alongside this that photography was at the same time the "perfect tool" of Empire, serving as an (apparently) objective, expedient method for the ethno- graphic cataloguing of subject peoples in the interests of "scientific" anthropol- ogy.”

“Partha Mitter identifies two periods in the history of "colonial" art in India: an era of "optimistic Westernization" between 1850 and 1900, dominated by pro-Western groups with an allegiance to European ideas and sensibilities; and its counterpoint, the cultural nationalism of the swadeshi doctrine of art (C.1900-1922), sympathetic to the sovereignty of the emergent Hindu identity (1994: 9). This new orientation prompted a reassessment of "the traditional heritage, from which the elite had recoiled in the first place" (9) and sanctioned long-ignored indigenous modes of artistic expression, which were now seen to be in harmony with modern Indian aspirations. Within this revival, however, art remained permeable to the technological advances of the West. which was felt to have the upper hand in the areas of painting and sculpture. In the art schools of India, Mitter notes, "the student was expected to be schizo- phrenic in his response: he would learn to appreciate Indian design and apply this insight in his work. But when he needed instructions in the "true" principles of drawing, he would turn to the West" (51). Such responses were never wholly expunged from cultural nationalist forms of painting, which mediated their vaunted indigenous authenticity through modernity itself. As in modern Europe, "the historicist revival of an 'authentic tradition' in India was a symptom of its loss. Significantly, the quest for authenticity did not begin in India until tradi- tional art had virtually disappeared" (243). Much in the same way that the cate- gory of the "classical" was a symptom and expression of the modernity with which it was contrasted, so too the quest for the authentic tradition was a singu- larly modernist preoccupation, indicative of an acutely felt disconnection from that tradition.”

“While scholars studying yoga (viz. Patanjali) during the "optimistic," philosophical period of colonialism mainly recoiled from the figure of the hath yogin, the cultural nationalists of the late nineteenth century began to look to grassroots ascetic traditions to forge a new ideal of heroism and nobility for the modern Indian. This reworking of spiritual heroism created the conditions that would eventually allow hatha yoga's inte- gration into transnational anglophone yogas, but in greatly modified form. As Sondhi writes half a century later in the Santa Cruz Yoga Institute's journal, within the "renaissance" brought to full flower by the likes of Yogendra, hatha yoga was expected to render "the rationale for what was known in the freedom struggle as the "Swadeshi" movement" (1962: 66). That is to say, as the exem- Plary Indian body-discipline-elect, the practice of hatha yoga represented the most basic, elemental assertion of self-rule and, some years later, of emanci- pated and internationally recognized cultural identity. As such, it could reason- ably be considered "the physiological basis of other Indian cultural disciplines" (66). However, as with Indian colonial art, the search for 'true' principles" (65) underlying hatha yoga occasioned an extensive project of validation through scientific, medical, and physical culture paradigms that were largely extraneous to the prior tradition, and it is in this sense that we can speak of an ongoing "schizophrenia" within modern hatha yoga, as Mitter does with regard to Indian art.”

“What is significant for our consideration of mass-produced, photographic modern yoga primers is the extreme rarity of this text, which remains "Quite unique" (Bühnemann 2007a:156) in its visual representation of asana. Indeed. the text and illustrations, warns Bühnemann, should by no means be taken to point toward an ancient asana lineage: "such an ancient tradition of 84 pos- tures," she writes, "is not accessible to us, nor is there any evidence that it ever existed" ”

“I have been considering the growth of postural yoga as a function ofawere wide revival of physical culture. Here I focus on a single school of posturi yoga- the laganmohan Palace yogasalà of T. Krishnamacharya-arguing that t is only against this broader backdrop of physical education in India that we can fil, understand the historical location of Krishnamacharya's hatha yoga method. The style of yogasana practice that has come to prominence in the West since the late 1980s through Pattabhi Jois's Ashtanga Vinyasa (and its various derivative forms) represents a unique and unrepeated phase of Krishnamacharya's teach ing. After he left Mysore in the early 1950s, his methods continued to evolve and adapt to new circumstances, and it is telling in this regard that the teaching sile of his later disciples in Chennai (such as son T. K. V. Desikachar and senior student A. G. Mohan) bears little resemblance to the arduous, aerobic sequences taught by Pattabhi Jois. If we are to understand the derivation and function d modern forms of "power yoga" we must first enquire why Krishnamachan* taught this way during his years in Mysore.'

“The physical culture experiments that bur- geoned in the state during this period should therefore be understood as being in accord with his wishes and with the combined expertise in asana and physical culture of lieutenants like Krishna Rao. It was within this milieu that another of the Maharaja's donees, Krishnamacharya, would develop his own system of hatha yoga, rooted in brahminical tradition but molded by the eclectic physical culture zeitgeist.”

“it suggests (once again) that at this time süryanamaskär was not yet considered part of yogasana. Krishnamacharya was to make the flowing movements of süryanamaskär the basis of his Mysore yoga style, and Pattabhi Jois still claims that the exact stages of the sequences ("A" and "B"), as taught by his guru, are enumerated in the Vedas. As noted in the introduction, this last claim is difficult to substantiate! What is important for our purposes, however, is that in those days it was far from obvious that süryanamaskar and yoga were, or should be, part of the same boot of knowledge or practice. As Shri Yogendra insists, "süryanamaskaras or prosti tions to the sun--a form of gymnastics attached to the sun worship in India- indiscriminately mixed up with the yoga physical training by the illinformed is definitely prohibited by the authorities"

“The elusive manual is also today commonly elicited as a practical elabora- tion of Patanjali. In one version of Krishnamacharya's biography, the Yogakurunta is said to have combined in one volume Vamana's "jumping" system of Ashtanga yoga and the Yogasutras with Vyasa's Bhasya, and is therefore taken to represent one of the few "authentic representations of Patanjali's sutra that is still alive" (Maehle 2006: 1). Hastam (1989) attributes a similar view to Krishnamacharya himself. As I argue elsewhere (Singleton 2008a), such asser- tions can be better considered as symptomatic of the post hoc grafting of mod- en ásana practice onto the perceived "Pätañjala tradition" (as it was constituted through Orientalist scholarship and the modern Indian yoga renaissance) rather than as historical indications of the ancient roots of a dynamic postural system called Ashtanga Yoga.”

“Yoga Kurunta is one of a number of "lost" texts that became central

1 Krishnamacharya's teaching; Sri Näthamuni's Yoga Rahasya, which

Krishnamacharya received in a vision at the age of sixteen, is another. Some

scholars are of the opinion that the verses of Yoga Rahasya are a patchwork of

other, better-known texts plus Krishnamacharya's own additions (Somdeva

Vasudeva, personal communication, March 20, 2005), while even certain stu-

dents of Krishnamacharya have cast doubt on the derivation of this work. For

instance, Srivatsa Ramaswami, who studied with Krishnamacharya for thirty-

three years until the latter's death in 1989, recalls that when he asked his teacher where he might procure the text of the Yoga Rahasya, he was instructed "with a chuckle" to contact the Saraswati Mahal library in Tanjore (Ramaswami 2000: 18). The library replied that no such text existed, and Ramaswami, noticing that the Slokas recited by Krishnamacharya were subject to constant variation, concluded that the work was "the masterpiece of [his| own guru" (18). It is entirely possible that the Yoga Kurunta was a similarly "inspired" text, attributed to a legendary ancient sage to lend it the authority of tradition.”

“Given Krishnamacharya's commitment to the "Patañjala tradition," and his uncompromising rejection of the satkarmas because they do not appear in the Yogasutras, it may seem quite a stretch to promote a form of aerobic ásana pra.- tice that has such a tenuous link to this tradition. Ultimately, Krishnamachanas sublimation of twentieth-century gymnastic forms into the Pätañjala traditionis less an indication of a historically traceable "classical" asana lineage than of the modern project of grafting gymnastic or aerobic ásana practice onto the Yogasutras, and the creation of a new tradition.”

“The various sequences of Ashtanga Vinyasa are, he asserts, the innovation

of Pattabhi Jois, and do not reflect how Krishnamacharya was teaching at this

time. In his opinion Pattabhi Jois' system may even prove harmful in so far as it

"continues without any consideration of the constitution (of the individual). Now, while this certainly supports T.R.S. Sharma's memories of the yogasala

style of teaching, the ascription of the Ashtanga Vinyasa series to Pattabhi Jois

is probably mistaken, not least because Krishnamacharya published a list of the

series in Yogasanagalu. Furthermore, according to B. K. S. lyengar, Pattabhi Jois was deputed by Krishnamacharya to teach asana at the Sanskrit Pathasala when the yogasalä was opened in 1933, and so was actually "never a regular student" there (lyengar 2000: 53). This in itself would account for why lois's system differs from what Krishnamacharya appears to have taught to others at this time. It may well be the case, then, that the aerobic sequences which now form the basis of Ashtanga Vinyasa yoga represent a particularized method of practice con- veyed by Krishnamacharya to Pattabhi Jois, but are not representative of Krishnamacharya's overall yogic pedagogy, even during this early period. It also seems likely, given Krishnamacharya's commitment to the principle of adaptation to individual constitution, that these sequences were designed for Pattabhi Jois himself and other young men like him. Since Pattabhi Jois's duties at the Päthasalà prevented him from being exposed to the kind of instruction in ásana given to T.R.S. Sharma and others, his teaching remained confined to the powerful, aerobic series of äsana formulated for him and his cohort by Krishnamacharya. These series would eventually form the basis of today's Ashtanga Vinyasa yoga. What is more, a prescribed sequence where each asana is part of an unchanging order, performed to a counted drill, would have offered a convenient and uncompli- Sated method for a novice teacher like lois (who was then eighteen years old).”

“Indeed, Krishnamacharya himself indicated to Ramaswami that such dynamie sequencing, called "vrddhi" (lit. growth, increase) or "rustikrama" (from srustim- kr, lit. to obey), is "the method of practice for youngsters," and is particularly suited to group situations (Ramaswami 2000: 15). In such a system, "one will be able to pick and choose some of the appropriate vinyasas and string them together (ibid.). Could it be that what has come to be known since the 1970s as "Ashtanga Vinyasa" represents the institutionalization in transnational anglophone yoga of a specific and localized vinyasa bricolage designed by Krishnamacharya in the 1930s for South Indian youths, but transmitted subsequently by Pattabhi Jois to (mainly Western) students as the ancient, orthopractic form for asana practice, delineated in the Vedas and the lost Yoga Kurunta?”

“We should also note here the account given of the lean pre-sälá years by Fernando Pagés Ruiz in the pages of Yoga Journal, during which Krishnamacharya sought to popularize yoga and "stimulate interest in a dying tradition" by demon- strating extraordinary feats of strength and physiological control, such as sus- pending his pulse, stopping cars with his hands, performing difficult asanas, and lifting heavy objects with his teeth (Ruiz 2006). As Ruiz comments, "to teach people about yoga, Krishnamacharya felt, he first had to get their attention" (Ruiz 2006). It seems eminently possible that the advanced asana extravaganzas per- formed in later years by his senior students had a similar function and shared in a common "modern strongman" discourse. As we saw in chapter 5, such feats of strength are common in modern Indian physical culture literature, where they are often (at least nominally) associated with hatha yoga. We recall, for instance, the case of the bodybuilder and physical culture luminary Ramamurthy, who regularly performed stock feats of strength such as Krishnamacharya's. These demonstra- tions, in other words, were leitmotifs that straddled the worlds of modern body- building and yoga.”

“A common refrain among the first- and second-generation students of Krishnamacharya whom I interviewed, as well as others who knew him during his Mysore days, is the association of his teaching with the circus. For example, the bodybuilding and gymnastics teacher Anant Rao, who for several years shared a wing of the Jaganmohan Palace with Krishnamacharya, feels that the latter was “teaching circus tricks and calling it yoga” (interview, September 19, 2005). T. R. S. Sharma considers the yoga he learned at Kaivalyadhama to be “more rounded” than Krishnamacharya’s approach, which “was more like circus” (inter- view, September 29, 2005) but nonetheless feels that it is inappropriate to call the postures “tricks” (personal communication, February 3, 2006, after reading a first draft of this chapter). And Sŕ ̄ınivas̄ a Rangac̄ ar (one of Krishnamacharya’s earliest students, about whom more shortly) similarly deemed the as̄ ana forms he learned “circus tricks” (interview, Shankara Narayan Jois, September 26, 2005). A later student of Krishnamacharya, A. V. Balasubramaniam, states in a recent film documentary on the history of yoga:

In the thirties and forties when he felt that yoga and interest in it was in a low ebb, [Krishnamacharya] wanted to create some enthusiasm and some faith in people, and at that point in time he did a bit of that kind of circus work . . . to draw people’s attention. (Desai and Desai 2004) The āsana systems derived from this early chapter of Krishnamacharya’s career dominate the popular practice of yoga in the West today, and yet it is largely overlooked that they stem from a pragmatic program of solicitation that exploits a long theatrical tradition of acrobatics and contortionism. This is not to say, of course, that Krishnamacharya approached his demonstrations like sideshows at a mela, but merely that audiences would have recognized the per- formances as belonging to a well-established topos of haṭha yogic fakirism and circus turns”

“Pattabhi Jois also participated in a large number of demonstrations, along with senior Pātḥ aśālā students like Mahadev Bhat and a number of Arasu boys. The āsanas were distributed beforehand into primary, intermediate, and advanced categories, with the younger boys performing the easiest poses while Jois and his peers demonstrated the most advanced (interview, Pattabhi Jois, September 25, 2005). These sequences were, according to Jois, virtually identical to the aerobic schema he still teaches today: that is, several distinct “series” within which each main āsana is conjoined by a short, repeated, link- ing series of postures and jumps based on the sūryanamaskār model. Although he would never endorse such an interpretation himself, his description sug- gests that the three sequences of the Ashtanga system may well have been devised as a “set list” for public demonstrations: a shared repertoire for stu- dent displays.”

“Indeed, Srinivasa Rangäcar related to one of his senior students that during his time as a student-teacher at the yogasala Krishnamacharya used "all kinds of gymnastic equipment" in his teaching (including rope climbing apparatus) and that in those days, Krishnamacharya's teaching "was considered gymnastics alone"

“The functional/descriptive names given to Bukh’s exercises are also mirrored in the functional/descriptive names that characterize what Sjoman postulates are late āsanas (in contradistinction to the symbolic objects, animals, sages, and deities that gave their name to earlier postures, Sjoman 1996: 49).

I point out these similarities not to suggest that Krishnamacharya borrowed directly from Bukh but to indicate how closely his system matches one of the most prominent modalities of gymnastic culture in India, as well as in Europe. And as we saw in chapter 4, Bukh-influenced gymnastics were, by the mid-1930s, a standard choice for children’s physical culture in popular publications like Health and Strength. While this notion challenges the narrative of origins com- monly rehearsed among Ashtanga practitioners and teachers today, it is really hardly surprising, given the context, to see elements of Danish children’s gym- nastics emerge in Krishnamacharya’s pedagogy in Mysore. Sjoman inquires with regard to Krishnamacharya’s system, “are the asanas really part of the yoga system or are they created or enlarged upon in the very recent past in response to modern emphasis on movement?”

“It is clear that these sections of the syllabus represent a fusion of popular “indigenous” aerobic exercises with āsana to create a system of athletic yoga mostly unknown in India before the 1920s. This was partly a response to the influence of the rhythmic acrobatics of Western gymnastics. Krishnamacharya’s dynamic teaching style in Mysore is of a piece with this trend, and his elaborate innovations in āsana represent virtuoso additions to what was, by the time he began teaching in Mysore, becoming a standard exercise format across the nation. Although the evident proficiency of his young troupe was probably unsur- passed at the time, the mode of practice was in itself by no means exceptional.”

“An attempt to exhaust the possible influences that may have given rise to Krishnamacharya’s āsana system would be fruitless and dull. It has rather been my intention in this chapter to establish that Krishnamacharya was not working

within a historical vacuum and that his teaching represents an admixture of cultural adaptation, radical innovation, and fidelity to tradition. This is not a particularly contentious assertion. The attribution of all his learning to the grace of his guru and to the mysteriously vanished Yoga Kurunta can be understood as a standard convention in a living (Sanskritic) tradition where conservation and innovation are tandem imperatives. As Pierre-Sylvain Filliozat explains,The orthodox pandit is not in the least concerned to restore an ancient state of affairs. If he were to point out the diachronic differences between the base-text and his own epoch, he would have to reveal his own share of innovation and his individuality. He prefers to keep this latter hidden. For him, the important thing is to present the whole of his knowledge—which contains both the ancient heritage and his new vision—as an organized totality. (Filliozat 1992: 92, my trans.)”

“This chapter and those which precede it have outlined some of the ways in which the early modern practice of āsana was influenced by various expressions of physical culture. This does not mean that the kind of posture-based yogas that predominate globally today are “mere gymnastics” nor that they are necessarily less “real” or “spiritual” than other forms of yoga. The history of modern physi- cal culture overlaps and intersects with the histories of para-religious, “unchurched” spirituality; Western esotericism; medicine, health, and hygiene; chiropractic, osteopathy, and bodywork; body-centered psychotherapy; the mod- ern revival of Hinduism; and the sociopolitical demands of the emergent mod- ern Indian nation (to name but a few). In turn, each of these histories is intimately linked to the development of modern transnational, anglophone yoga. Historically speaking, then, physical culture encompasses a far broader range of concerns and influences than “mere gymnastics,” and in many instances the modes of practice, belief frameworks, and aspirations of its practitioners are coterminous with those of modern, posture-based yoga. They may indeed be at variance with “Classical Yoga,” but it does not follow from this that these practices, beliefs, and aspirations (whether conceived as yoga or not) are thereby lacking in seri- ousness, dignity, or spiritual profundity. For some, such as best-selling yoga scholar Georg Feuerstein, the modern fascination with postural yoga can only be a perversion of the authentic yoga of tradition. “When traditional yoga reached our Western shores in the late nine- teenth century,” writes Feuerstein, “it was gradually stripped of its spiritual ori- entation and remodeled into fitness training” (2003: 27).22 However, as should be clear by now, several aspects of Feuerstein’s assessment are misplaced. First, Vivekananda’s system should not be considered “traditional yoga” in any strict sense but rather the first (and possibly most enduring) expression of what I have termed “transnational anglophone yoga.” Second, the notion that “fitness” is somehow opposed to the “spiritual” ignores the possibility of physical training as spiritual practice, in India as elsewhere”

0 notes

Text

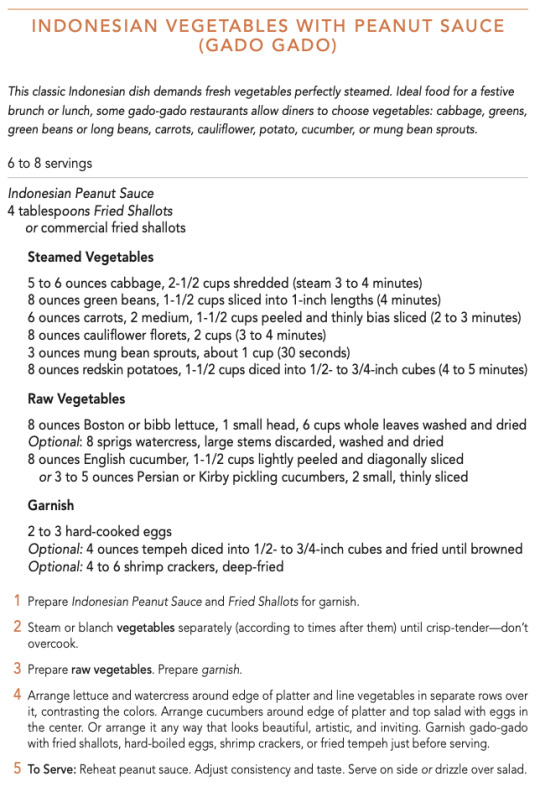

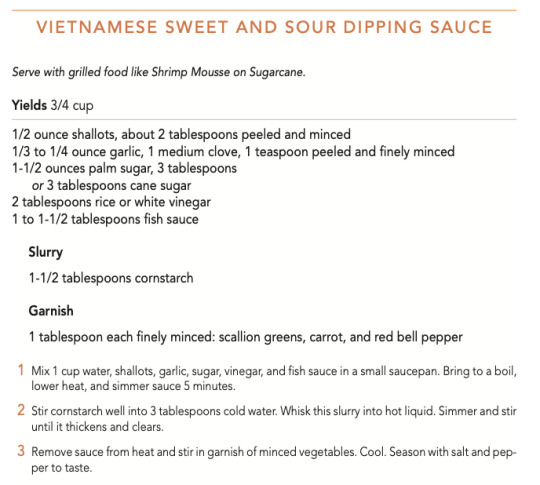

South East Asia: Thailand, Vietnam, and Indonesia

Week 3: Chapter 2: Thailand, Vietnam, and Indonesia Sustainability Topic: Animal husbandry

INTRODUCTION

This week, I will be learning…

Method: soup, rice paper rolls, stirfry noodle, rice

Menu: Thai Chicken Coconut Soup, Sticky Rice, Vietnamese Sweet & Sour Dipping Sauce, Vietnamese Rice Paper Wrapped Rolls, Indonesian Fried Noodles with pork, Indonesian Vegetables with peanut sauce

Vocabulary: galangal, papaya, tom kha gai, pad thai, gaeng bah

Prior Knowledge

I have made thai curry before; it is one of my favorite things to make whenever I have the ingredients. I have not had much Vietnamese food or Indonesian food. I know that south east asia uses fish as a source of umami. I have used the little dried shrimp in my curry paste before.

Learning Objectives

This week, we will introduce three of the most influential countries of South East Asia, their histories, geography, cultural influences, and climates.

We’ll introduce the culinary cultures, regional variations, and dining etiquette of Thailand, Vietnam, and Indonesia. We’ll identify the foods, flavor foundations, seasoning devices, favored cooking techniques of Thailand, Vietnam, and Indonesia, and how they differ and where they are similar. We’ll discuss technique and recipes of the major dishes of Thailand, Vietnam, and Indonesia.

RESEARCH

Method of Cooking

Origin and History

Thailand contains two flourishing cuisines:

the palace cuisine and the simple, practical peasant cuisine. (Street food is a much-relished third.) Peasant cuisine is spicy and robust, fast-cooked with stir-fried noodles or meat. Palace cuisine is sweeter, less intense, with richer ingredients like coconut milk and lots of fruit and vegetable carving and elaborate presentation. Rice, fish, and seafood are important to both.

Vietnam:

“Originally a breakfast from North Vietnam’s capitol, Hanoi, pho has become the signature noodle dish or soup of all Vietnam. Vietnamese eat it for breakfast, lunch, or a late-night snack. Prepare it with beef, chicken, shrimp, or pork. Hanoi-style pho bo with beef and pho ga with chicken are the favorites.”

“Northern pho uses wide noodles and more green onion than southern style pho. Southern Vietnamese pho broth is sweeter and includes bean sprouts and many fresh herbs with variations in meat, broth, and additional garnishes such as lime, hoisin, bean sauce, and chili sauce.”

Indonesia:

Indonesia contains people of many ethnic backgrounds due to the huge amount of trade that took place in the sixteenth century. “Multiethnic Indonesia’s national motto is Unity in Diversity. Today almost 90 percent of Indonesians are Muslim, with Buddhist, Hindu, and Christian minorities. Indonesians speak numerous languages and dialects, but Bahasa Indonesia is the official language.”

In Indonesia, cultivated or forest grown crops like rice, corn, vegetables, sago, coconut, spices, mung beans, cabbage, carrots, peanuts, potatoes, and asparagus prevail.

Map of Cuisines

Class Discussion Questions

• Study area maps

• What influences the various areas being studied? For example, does the area have maritime influences, mountains, dry, Mediterranean climate,

what is the weather like? Thailand: mountains, river

• Prepare the follow questions for class discussion:

- Name two large countries that influenced Southeast Asian cuisine

- What two types of cuisine flourish in Thailand? Describe the differences.

- What two countries influenced Vietnamese cuisine? Discuss their influences.

- Name one Vietnamese dish and discuss its preparation.

- Name the three main islands of Indonesia.

- What were the key cultural influences on Indonesian cuisine and why?

- What two foods define the Indonesian diet?

- In your research, bring one-two interesting findings from the area to share in class.

Dish Method Variations