#the great atlantic & pacific tea company

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Change to the coffee that’s alive with flavor! A&P Super Markets ad - 1955.

#vintage illustration#vintage advertising#a&p#a&p super market#super markets#coffee#coffee drinkers#coffee beans#great atlantic & pacific tea company#coffee companies#grocery stores#a&p coffee

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

EVERYBODY NOW:

����The great store - just next door:

A&P!!!🎶

#the great store just next door#a&p#Great Atlantic & Pacific Tea Company#tri-state area#north jersey#1993#90s commercial#growing up jersey#Youtube

1 note

·

View note

Text

The Great Atlantic & Pacific Tea Company, 1956

#A&P coffee#ad#1956#Fall#midcentury#advertisement#roasted to perfection#flavor#vintage#mid century#stores#autumn#advertising#1950s#mid-century

147 notes

·

View notes

Text

~ Jane Parker Cake Advertising Sample Book*, 1947

"Enjoy your baby shower, Sally! Hope it's a Boy so this is all worth it!"

*Jane Parker was one of the in-house store brands at the Great Atlantic and Pacific Tea Company (A&P) grocery chain.

42 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Great Atlantic & Pacific Tea Company, 1956

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Document Dust 98.25 (THE GREAT ATLANTIC AND PACIFIC TEA COMPANY NEW YORK: A. & P. EXTRACTS)

0 notes

Text

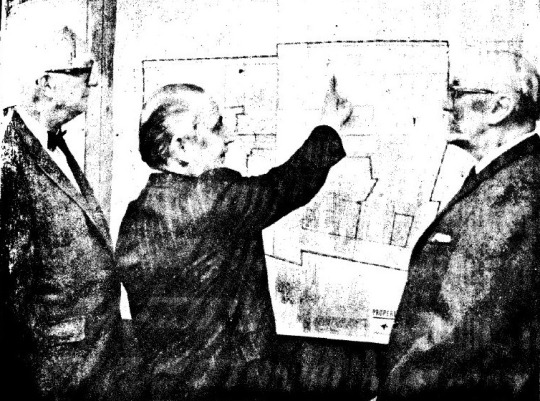

When urban renewal came to Penn Yan

By Jonathan Monfiletto

Sixty years ago, the village of Penn Yan embarked on a vision to rejuvenate the community and invest in the downtown area by knocking down dilapidated buildings, repairing salvageable structures, renovating and relocating some local businesses and agencies, installing off-street parking, and alleviating traffic congestion. The village board adopted a development plan outlining these goals in 1961; in April 1964, the board established – through the action of the New York State Legislature – the Penn Yan Urban Renewal Agency to seek state and local funding for projects and oversee their completion.

At that time, the Walkerbilt wood manufacturing company was located on Lake Street along the Keuka Lake Outlet; across the street were family homes impacted by the factory’s pollution and disruption. The Penn Yan fire station was located in a cramped space on Main Street wedged among downtown businesses. Elm Street between Main and Liberty streets hosted a plethora of local businesses. Several buildings in the downtown area were deemed in need of improvement – or in need of demolition – and the streets were congested with automobiles parked along the curbs.

Such was the scene when urban renewal came to Penn Yan, starting from the early 1960s and lasting until the early 1970s. Urban renewal undoubtedly has a negative connotation in American history – and rightfully so – for the displacement of minority communities and businesses in the name of economic development and revitalization that unfolded in large cities across the nation. However, for Penn Yan, urban renewal took the form of what might be called today – in New York State – a downtown revitalization program.

Early on, village officials learned the federal government would contribute – for a municipality of 50,000 people or fewer – three-fourths of the cost of an urban renewal project. Of the remaining quarter, the state would pay half – or one-eighth of the total cost – while the village would pay the final eighth. And, by establishing an urban renewal agency, Penn Yan could borrow up to 2 percent of the value of all assessable property rather than – without such an organization – 2 percent of the value of all taxable property, giving the village more spending power.

So, with the bulk of planning and preparation taking shape throughout 1965, Penn Yan started what it called the Jacobs Brook Urban Renewal Project. This project focused on rejuvenating the area of the village bounded by Maiden Lane to the north, Liberty Street to the west, the namesake stream to the east, and Elm and East Elm streets to the south, with the downtown area of Main Street smack dab in the middle. By the end of the year, the board also took steps toward what was called the Keuka Lake Outlet Development Project – an effort that largely involved relocating Walkerbilt to a larger, more modern facility on North Avenue and refurbishing the project with the park that stands there today.

Following a survey of the business area in 1964, it was reported in October 1965 that urban renewal would displace 12 businesses and five families – a total of 14 people living in second-floor apartments in the village downtown – and the first property appraisals were completed. Among the structures to be acquired and demolished were the firehouse, a supermarket, a warehouse, a used car display area, and several vacant buildings. On the east side and rear of Main Street, the village acquired 97,297 square feet of space; on the west side and rear of Main Street, the village acquired 70,805 square feet. Of this acquired space, 35,935 square feet was to be redeveloped for new buildings while 132,162 square feet was set aside for off-street parking. With the establishment of municipal parking lots behind both the west and east sides of Main Street, downtown parking spaces increased from 40 to 175.

In April 1966, the Great Atlantic & Pacific Tea Co. grocery store – then located on Main Street approximately where Community Bank is now – requested 10,500 square feet of building space for a new supermarket after it was displaced. On the flip side of the same coin, the Thompson Furniture Co. – then located approximately where the Town of Milo offices are now – sought to return to the same spot after its building was razed. That July, the village acquired property on the north side of Elm Street for the new firehouse, though it wasn’t without controversy when it came to an adjacent parcel owned by Jolley Chevrolet. Jolley declined the village’s offer to buy the parcel, so the village began condemnation proceedings against the parcel; the matter went to court, and the village won over Jolley. Later, a similar battle arose when Henderson’s Drug Store refused to allow the village to lop off 20 feet from the rear of its building to make space for a municipal parking lot; that time, the local business won the day.

In March 1967, U.S. Rep. Samuel Stratton announced the village would receive a $758,030 grant toward land acquisition, relocation of site occupants, site clearance, and preparation related to the Jacobs Brook Urban Renewal Project. If 1965 was the planning and preparing step and 1966 involved the surveys and concepts, then 1967 marked when the real work began especially with the boost of this funding. The following year, the village received $437,808 for the Keuka Outlet Development Project to demolish six properties on Lake Street along the outlet, refurbish the area into a park, and relocate the Walkerbilt plant. By December 1967, the Penn Yan Urban Renewal Agency announced the real, physical work of the project “will be in full execution within a few days” after being bogged down by legal technicalities.

The remaining years of the 1960s saw the phases of property acquisition, building demolition and rehabilitation, and the construction of new buildings and development of existing properties as downtown Penn Yan took on a new look. While the demolition of structures to the rear of the buildings on the west side of Main Street paved the way for the parking lot there, a 14-foot wide, 9-foot high, and 100-foot long steel pipe was installed in Jacobs Brook to allow the area to be filled in and covered over to create the parking lot there. Two buildings in that area were also razed to make space.

In 1970, yet another urban renewal controversy arose when 26 buildings and their respective business owners were told they must meet rehabilitation standards or face the loss of their properties. At this point, the village noted the difficulty of enforcing new code requirements in light of urban renewal. At the same time, people wondered whether urban renewal had gone too far if the village could condemn and demolish any building it wanted to.

It was this discontented realization as well as the fact that projects had been completed – including with new buildings and new businesses on Main Street – that brought the urban renewal area in Penn Yan to end by February 1973. At that point, the village board “closed out its business with the Penn Yan Urban Renewal Agency,” according to an item in The Chronicle-Express.

Was urban renewal a good thing or a bad thing for Penn Yan? The jury was still out when urban renewal end, and it might still be out today.

#historyblog#history#museum#archives#american history#us history#local history#newyork#yatescounty#pennyan#urbanrenewal#business#industry#government#newspaper

0 notes

Text

This is less true of NAFTA specifically than free trade agreements in general I think, but in addition to the (relatively small) group of workers who were hurt by these deals is that the companies that have lost out from lowering protectionist barriers are companies like Ford, GM, Chrysler, US Steel, and other manufacturing companies that struggle to thrive or even survive against, frankly, better overseas competitors. And much like the while male blue collar manufacturing workers themselves, these companies have a big role in nationalist myth-making, are seen as responsible for building America in the 20th century, forming the arsenal of democracy and so on.

Looking at the largest US companies by revenue in 1929 (source):

I don't know about Great Atlantic & Pacific Tea but four of the top five here are "iconic American companies" of the 20th century. Biden dressed it up as a labor protection issue but I think there's no doubt his intervention to stop the sale of US Steel to a Japanese steel company this year was all about preventing an American icon based in a politically important swing state from being taken over by a foreign company in an election year.

I kinda think the reason NAFTA was so unpopular, despite largely being good for the economy and a net positive for most people, was because the designated victims of the policy were largely white, male, and traditional blue collar manufacturing workers, all of which represent groups that most Americans are sympathetic towards. If we've made any sort of social progress since then, it's probably in the direction of being sympathetic towards the economic struggles of a wider group of people who may be non-white, not-male, and work in other economic sectors such as food service or retail.

Probably the number of people who haven't had a raise since 2019 and now struggle to afford rent and groceries *is* relatively low. But the amount that those people *are* worse off is significant, which means that even if that doesn't describe you, you can still feel exasperation on their behalf when you're upset that your McDonald's costs $20.

9 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Coffee testing at the Great Atlantic & Pacific Tea Company (November 6th, 1942). This is one of the company's eight coffee roasting plants.

“J.W. Zawacki has been testing coffee for A&P for 25 years. First, he smells the coffee. Then, he skims off the grounds still on top of the coffee and tastes a spoonful. Generally a taster expectorates the coffee after determining the quality – but Mr. Zawacki often drinks it. 'Coffee is good,' he says.”

12 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Berenice Abbott, A & P, Great Atlantic and Pacific Tea Company, New York, 1936.

#Berenice Abbott#photography#New York City#New York#A&P#The Great Atlantic and Pacific Tea Company#30's

268 notes

·

View notes

Text

Non c’è posto per chi cerca di semplificare la sua vita. Non c’è posto per chi non cerca di far quattrini, o non cerca di far sì che i quattrini producano quattrini. Non c’è posto per chi porta lo stesso vestito un anno dopo l’altro, per chi non si fa la barba, e non crede nella necessità di mandare i figli a scuola a farsi diseducare, per chi non si scrive alla Chiesa, al Sindacato e al Partito, per chi non serve la «Delitto, Peste e Distruzione, S.p.A.». Non c’è posto per chi non legge «Time», «Life», e una qualche «Selezione». Non c’è posto per chi non vota, non è assicurato, non compra a rate, non ammucchia debiti su debiti, non ha un libretto d’assegni e non fa affari con i grandi magazzini Safeway o con la Great Atlantic and Pacific Tea Company. Non c’è posto per i best-seller del giorno e non contribuisce a mantenere i ruffiani venduti che li scaricano sul mercato. Non c’è posto per chi è tanto sciocco da credere d’avere il diritto di scrivere, dipingere, scolpire o comporre musica secondo i dettami del proprio cuore e della propria coscienza. O che non vuole essere altro che un artista, un artista da capo a piedi.

Big Sur e le arance di Hieronymus Bosch, Henry Miller.

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

6 million people will buy fifty million Thanksgiving treats at A&P. A&P Super Markets ad - 1951.

#vintage illustration#thanksgiving#thanksgiving day#thanksgiving day meals#thanksgiving day recipes#turkey day#day of the turkey#food#pilgrims#the holidays#the holiday season#thanksgiving day dishes#turkey#pies#side dishes#a&p super markets#super markets#a&p#the great atlantic & pacific tea company#grocery stores#food stores#vintage advertising

1 note

·

View note

Note

in the first episode with the Traveling Salesman he turns a town into black sand. Then in a later episode Halifax the other salesman has people dreaming of a black sand like substance, coffee grounds. So did the first town get turned into coffee grounds? And why coffee? Is that just random?

All that was left of Delton, Nebraska after The Traveling Salesman made a deal with him was black sand. The black sand was initially just a reference to Howl's Moving Castle, the novel. Diana Wynn Jones is a favorite writer of mine.

SPOILERS for the novel of Howl's Moving Castle below (sorry it ties into my reasoning for why it appears in AVFD).

In the book, falling stars are fire demons you can strike deals with. They can offer you great magic, but they'll eventually burn your heart out. A line from near the very end of the book, after Howl has defeated The Witch of the Waste and her fire demon: The Witch's old heart crumbled into black sand, and soot, and nothing.

So all that was left of Delton, Nebraska after they made their own terrible deal was black sand, as they too were reduced to nothing.

With Halifax and the coffee, he had a company, The Grand Eastern & Western Coffee Company. This too was a reference to something - The Great Atlantic & Pacific Tea Company, better known as A&P. Ask any American under the age of 40 and they've probably either never heard of it or they only know it from a short literary story that's often anthologized by John Updike. But one time, this tea company ruled the country. They pivoted to a general store and then created the modern grocery store. They were a monopoly (an antitrust suit was brought against them) that attacked small ma & pa shops and conspired against them. To their credit, they also created logistics chains that considerably lowered what Americans paid for groceries.

But a lot of what is in the Halifax episode was somewhat of a history, not necessarily of A&P but a lot of the monopoly/robber baron sorts of men and companies that existed in that era. I haven't gone back to listen to those episodes, but I think I was just trying to convey the same thematic image of "black sand" from the first Traveling Salesman episode to the Gilman Halifax one since by happy coincidence coffee grounds can look like black grains of sand, and I'd already been thinking of a Robber-Baron Salesman figure who ran a large monopoly. There's more to that too, but I can't say without getting into spoilers and things that haven't happened on the show yet. I hope that answers your question though.

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Great Atlantic & Pacific Tea Company, 1947

#A&P#ad#1947#mid-century#summer festival#ice cream#advertisement#illustration#peach dessert#Ann Page#sparkle desserts#vintage#midcentury#advertising#post-war#1940s#recipe#mid century#40s ads#postwar

104 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Basics of currency trading in Canada, Quebec the basics of currency trading in Canada, Launay Stay Exchange Charge Not too long ago, in a very long time the worldwide debate about foreign money points.

#16th century in Canada#Basics#Canada#French colonization of the Americas#History of North America#Institute of Worldwide Chinese#insurance coverage insurance policies#LVL#Nationwide Govt Committee#Provinces#Quebec#South Africa#Teacher#The Great Atlantic & Pacific Tea Company#Vieux-Comptoir#web entry

0 notes

Text

From the A&P to Amazon: The rise of the modern grocery store

By Michael S. Rosenwald, Washington Post, June 16, 2017

The history of grocery stores--from the A&P to Amazon’s surprise purchase of Whole Foods--can be traced back to a common kitchen product: Baking powder. Really.

Back in the late 1800s, the proprietors of the Great Atlantic & Pacific Tea Company faced a problem. The tea industry they had controlled for decades had become widely available. Prices fell. It appeared Great Atlantic & Pacific would too.

The Hartford family, the owners of the company, decided to diversify. They added a controversial product: baking powder. Housewives loved the stuff, which made bread rise faster. Baking powder became so popular that unscrupulous producers, in rushing the product to stores, weren’t exactly delivering the real deal. Also, the prices were high.

The Hartfords decided to make their own baking powder. They even hired a chemist. And then they packaged the powder in red tins, labeling it A&P--leveraging the company name to denote quality.

“A&P Baking Powder was an important product in the history of retailing,” Marc Levinson wrote in “The Great A&P,” a history of the company and grocery stores. “With it, the Great Atlantic & Pacific Tea Company, and many of its competitors, began a transition from being tea merchants to being grocers. It was a transition that would dramatically change Americans’ daily lives.”

The branding of baking powder was important because most merchants back then were just essentially selling, as Levinson wrote, “generic products indistinguishable from what was for sale down the street.” And in selling their powder in a tin, the owners were ahead in another important way--packaging.

The invention of the cardboard box changed everything.

The company could now make, brand and sell its own condensed milk, butter, spices--just about any staple of the kitchen.

“By the early 1890s,” Levinson wrote, “Great Atlantic & Pacific was making the shift from tea company to grocery chain.”

Its name: A&P.

There was difficult, transformative work ahead. The company needed to upend an entire culture of shopping built around neighborhood stores, a history detailed in a fascinating 2015 paper titled, “The Evolution of the Supermarket Industry: From A&P to Walmart,” by Paul B. Ellickson:

Before 1900, American shoppers purchased their groceries through a wide array of specialty shops and general stores. Meat was purchased from a butcher, fish from a fishmonger, bread from a baker, and produce from a vegetable stand. Mostly sole proprietorships, these stores were often run in a haphazard manner with little use of modern accounting practices or scientific management principles. There were certainly many stores, likely well over half a million, although accurate historical statistics do not exist for this period. Because most people arrived on foot, grocers needed to be close to their customers, so the stores were small and ubiquitous. They often delivered what was purchased and sold many goods on credit. The small sales volume of these tiny shops led to high costs and sizable markups.

A&P built big stores, stocking as many products as possible, many made in their own warehouses. Products were stored in shelves, not behind a counter for an employee to distribute. No credit--cash. Manufacturers liked the model, selling products directly to the company, not through wholesalers. This kept product costs down for A&P, which passed those savings on to shoppers.

The company became obsessed with prices. In the early 1900s, its profit was 3 percent of revenue. This was too high. A new profit goal was set: 2.5 percent.

“If the company’s profit margin widened,” Levinson wrote, “it would be not a good sign but a bad one, an indication that A&P was forsaking the cost discipline that would lead it to domination of the grocery market.”

A&P’s business model began to sound a lot like the one pursued by its retail descendants--Walmart and Amazon--though it would later fall prey to mismanagement and two bankruptcies that shuttered hundreds of stores.

“Their basic strategy was so extraordinarily simple it could be captured in a single word: volume,” Levinson wrote. “If the company kept its costs down and its prices low, more shoppers would come through its doors, producing more profit than if it kept prices high.”

Amazon’s tea was books. Then it diversified. On Friday, Amazon disrupted yet another sector of retailing with its $13.7 billion deal for Whole Foods--linking the Internet retailer to the baking powder purveyor that started it all.

2 notes

·

View notes