#the first Anglo-Sikh war

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Hari Singh Nalwa - A Prominent Military Commander of the Sikh Empire

Hari Singh Nalwa was a prominent military commander and general of the Sikh Empire in northern India, during the rule of Maharaja Ranjit Singh. He served as the Commander-in-Chief of the Sikh Khalsa Army and was known for his bravery, military tactics, and administrative skills. He fought in several battles and campaigns, including the First Anglo-Sikh War, and expanded the boundaries of the Sikh…

View On WordPress

#administrative skills#Afghan Empire#Attock#Battle of Jamrud#bravery#chronic illness#Conquest of Peshawar#First Anglo-Sikh War#Gujranwala#Hari Singh Nalwa#hero#India#Indian History#Jamrud#Jatt family#legacy#Maharaja Ranjit Singh#mid-to-late 40s#Military Commander#military tactics#Muslim forces#Nowshera#Pakistan#political realities#Sardar Chatha#Sikh Empire

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Treaty of Lahore

9 ਮਾਰਚ 1846 ਈਸਵੀ! ਪਹਿਲੀ ਸਿੱਖ ਅੰਗਰੇਜ਼ ਲੜਾਈ ਤੋਂ ਬਾਅਦ ਦੋਨਾਂ ਸਰਕਾਰਾਂ ਵਿੱਚ 9 ਮਾਰਚ 1846 ਈਸਵੀ ਨੂੰ ਸੁਲ੍ਹਾ ਨਾਮਾ ਹੋਇਆ; ਜਿਸ ਤੇ ਅੰਗਰੇਜ਼ਾਂ ਵੱਲੋਂ ਫਰੈਡਰਿਕ ਕਰੀ , ਹੈਨਰੀ ਲਾਰੰਸ ਆਦਿ ਸਨ ਤੇ ਲਾਹੌਰ ਦਰਬਾਰ ਵੱਲੋਂ ਭਾਈ ਰਾਮ ਸਿੰਘ, ਲਾਲ ਸਿੰਘ, ਤੇਜ ਸਿੰਘ, ਭਾਈ ਚਤਰ ਸਿੰਘ ਅਟਾਰੀਵਾਲਾ, ਰਣਜੋਧ ਸਿੰਘ ਮਜੀਠਾ, ਦੀਵਾਨ ਦੀਨਾ ਨਾਥ ਅਤੇ ਫ਼ਕੀਰ ਨੂਰਦੀਨ ਆਦਿ ਨੇ ਦਸਤਖ਼ਤ ਕੀਤੇ ਸਨ ! ਇਸ ਸੰਧੀ ਦੇ ਨਾਮ ਤੇ ਗੋਰਾ ਸ਼ਾਹੀ ਨੇ ਰੱਜ ਕੇ ਨਬਾਲਿਗ ਮਹਾਰਾਜੇ ਨਾਲ ਬੇਇਨਸਾਫ਼ੀ ਕੀਤੀ ; ਜਿਸ…

View On WordPress

#Anglo-Sikh war#first#Gursikh satth media#lahore#nimana#Punjab#sikh#sikhism#singh#Treaty#treaty of lahore

0 notes

Photo

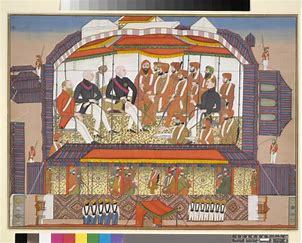

Second Anglo-Sikh War

The Second Anglo-Sikh War (1848-9) once again saw the British East India Company defeat the Sikh Empire in northern India. The war, which started off as a rebellion against British colonial rule, included the high-casualty Battle of Chillianwala, but the conflict was finally won by the EIC with a decisive victory at the Battle of Gujrat in February 1849.

The EIC & the Sikh Empire

The British East India Company had been grabbing territory since its victories at the 1757 Battle of Plassey and the 1764 Battle of Buxar, which gave the British a vast and regular income in local taxes, besides other riches. The EIC kept on expanding and defeated the southern Kingdom of Mysore in the three Anglo-Mysore Wars (1767-1799) and the Maratha Confederacy of Hindu princes in central and northern India in the three Anglo-Maratha Wars (1775-1819). Next came expansion in the far northeast and more victories in the Anglo-Nepalese War (1814-1815) and the three Anglo-Burmese Wars (1824-1885). The next and final target of the EIC was northwest India and the Punjab, the heartland of the Sikh Empire.

The Punjab, located in the northwest of the Indian subcontinent, is an area which today covers parts of Pakistan and India. The Sikh Empire had risen due to the gradual decline of the Mughal Empire (1526-1857). Sikh territories were divided between 12 misls or armies, each led by a chief who collectively formed a loose confederation. The greatest of Sikh leaders was Ranjit Singh (1780-1839), the 'Lion of Lahore'. He forged the Sikh Empire by modernising the army and conquering Multan and Kashmir (1819), Ladakh (1833), and Peshawar (1834). This expansion rang alarm bells in the offices of the East India Company, especially after their failure in the First Anglo-Afghan War (1838-42) to the north.

In 1839, the Sikhs, Afghans, and British signed a treaty to protect existing borders. Ranjit Singh died in June 1839, and political turmoil weakened the Sikh government's control over its own army. Rajit Singh's youngest son, Duleep Singh (l. 1838-1893), was selected as the new Sikh ruler in 1843, but as he was but a child, his mother, Jind Kaur (aka Rani Jindan, d. 1863), ruled as regent. Jind Kaur supported a military escapade against the British since, even if the Sikhs lost, this would cut the army down to size, perhaps ending the interference of the generals in government affairs and certainly reducing the threat of a military coup.

The EIC exploited the turmoil and conquered the Sindh province (southwest of the Punjab) in 1843. Confident that some of the Sikh misls in the east supported closer ties with the EIC, the British prepared for war in the Punjab and amassed an army of 40,000 men to the southeast of the Sikh state. In the wider world of empires, the British no longer considered the Sikh Empire a useful buffer zone in case of expansion of the Russian Empire into Afghanistan and northern India – the so-called Great Game. The Sikhs would now have to fight the seemingly unstoppable armies of the East India Company.

Continue reading...

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

Maharani Jind Kaur

Maharani Jind Kaur, also known as Rani Jindan, was a significant figure in Sikh history, serving as the last queen of the Sikh Empire from 1843 to 1846. Born in 1817 in Gujranwala, she became the youngest wife of Maharaja Ranjit Singh, the founder of the Sikh Empire. After Ranjit Singh's death in 1839, Jind Kaur took on the role of regent for her son, Maharaja Duleep Singh. Jind Kaur's reign as regent was marked by political turmoil and conflict with the British East India Company. In 1845, during the First Anglo-Sikh War, she dispatched the Sikh Army to confront the British, leading to the annexation of the entire Punjab in 1849. After her son's dethronement, she faced imprisonment and exile by the British. Despite challenges, Jind Kaur escaped captivity in 1849, disguising herself as a slave girl and finding refuge in Nepal. Her efforts to resist British dominance continued through correspondence with rebels in Punjab and Jammu-Kashmir. She later reunited with her son in Calcutta in 1861, influencing him to return to Sikhism. Jind Kaur's exile took a toll on her health, and she passed away in her sleep on August 1, 1863, in Kensington, England. Denied the opportunity to be cremated in Punjab, her ashes were eventually brought back to India in 1924 and reburied in the Samadhi of Maharaja Ranjit Singh in Lahore. Despite her challenging life and exile, Maharani Jind Kaur's legacy endures as a symbol of resilience and resistance against colonial rule. In 2009, a memorial plaque was unveiled at the Kensal Green Dissenters Chapel, honouring her contributions to Sikh history.

#sikh empire#jind kaur#mahrani jind kaur#maharaja duleep singh#duleep singh#history#women in history#indian women in history#colonialism#british imperialism#indian royalty

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sword from India dated to the 17th Century on display at the Highlander's Museum in Inverness, Scotland

This sword was presented to Sir Patrick Grant during the First Anglo-Sikh War (1845 - 1846) where he fought for the British East India Company. It is said to have belonged to a soldier in the service of Shah Jhan, a Mughal Emperor from the 17th century.

Such weapons were often taken by East India Company and British soldiers during the expansionist wars in India. They were briught back to Britain as symbols of conquest for museums or private collections.

Photographs taken by myself 2024

#art#military history#sword#17th century#mughal empire#india#indian#early modern period#highlanders museum#inverness#barbucomedie

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Events 12.6 (before 1950)

1060 – Béla I is crowned king of Hungary. 1240 – Mongol invasion of Rus': Kyiv, defended by Voivode Dmytro, falls to the Mongols under Batu Khan. 1492 – After exploring the island of Cuba for gold (which he had mistaken for Japan), Christopher Columbus lands on an island he names Hispaniola. 1534 – The city of Quito in Ecuador is founded by Spanish settlers led by Sebastián de Belalcázar. 1648 – Pride's Purge removes royalist sympathizers from Parliament so that the High Court of Justice could put the King on trial. 1704 – Battle of Chamkaur: During the Mughal-Sikh Wars, an outnumbered Sikh Khalsa defeats a Mughal army. 1745 – Charles Edward Stuart's army begins retreat during the second Jacobite Rising. 1790 – The U.S. Congress moves from New York City to Philadelphia. 1803 – Five French warships attempting to escape the Royal Naval blockade of Saint-Domingue are all seized by British warships, signifying the end of the Haitian Revolution. 1865 – Georgia ratifies the 13th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution. 1882 – Transit of Venus, second and last of the 19th century. 1884 – The Washington Monument in Washington, D.C., is completed. 1897 – London becomes the world's first city to host licensed taxicabs. 1904 – Theodore Roosevelt articulated his "Corollary" to the Monroe Doctrine, stating that the U.S. would intervene in the Western Hemisphere should Latin American governments prove incapable or unstable. 1907 – A coal mine explosion at Monongah, West Virginia, kills 362 workers. 1912 – The Nefertiti Bust is discovered. 1916 – World War I: The Central Powers capture Bucharest. 1917 – Finland declares independence from the Russian Empire. 1917 – Halifax Explosion: A munitions explosion near Halifax, Nova Scotia kills more than 1,900 people in the largest artificial explosion up to that time. 1917 – World War I: USS Jacob Jones is the first American destroyer to be sunk by enemy action when it is torpedoed by German submarine SM U-53. 1921 – The Anglo-Irish Treaty is signed in London by British and Irish representatives. 1922 – One year to the day after the signing of the Anglo-Irish Treaty, the Irish Free State comes into existence. 1928 – The government of Colombia sends military forces to suppress a month-long strike by United Fruit Company workers, resulting in an unknown number of deaths. 1933 – In United States v. One Book Called Ulysses Judge John M. Woolsey rules that James Joyce's novel Ulysses is not obscene despite coarse language and sexual content, a leading decision affirming free expression. 1941 – World War II: Camp X opens in Canada to begin training Allied secret agents for the war.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

It is not a compliment to note that book reminded me of some of the more shamefully jingoistic histories I've had the displeasure to read:

In particular where the book's nationalism stretched credulity way too far for any halfway literate person to more than halfway accept is that its first four chapters loudly and proudly note that Sikhs were and are morally superior to a caste-ridden backwards India of fanatical Muslims and Hindus who gleefully slaughter, rape, pillage, and burn Sikhs with a whim. Then after the conquest and absorption of the Sikhs into the Raj, the Sepoys are dirty treacherous sneaks who work with the British and the Sikhs who endorse the Raj and made up a disproportionate portion of its armies are all honorable people doing what's right for their nation and their culture.

Sikhs are proudly neither Hindu nor Muslim and had every expectation of keeping all their land and their sacred sites together, but anyone who notes that this might possibly smack of separatism is an anti-Sikh bigot where the Sikhs in turn very much developing precisely what they were feared to.....because the very fear spurred brutality that led to it is presented as straightforwardly honest. The Sikhs having an army and a willingness to use it to wage holy wars and build a great empire is sterling progress against their backwards barbarian neighbors, anyone who shoots back at the natural-born morally superior ruling caste is a filthy dog that deserves to die in the gutter. And that's this book's take on the various wars the Sikh fought up to the Anglo-Sikh Wars and also after them.

This is, to put it at its most blunt, about as much of a pretense of shame or honesty as that one book on the Forest Brothers by the Estonians who noted outright that the Nazis intended to exterminate Estonians and held as a matter of pride that even so the Estonian Forest Brothers were all in the Waffen-SS and where it did mention the Jews they were filthy traitors who deserved the massacre.

Or any right-wing US book on any of the bad things the USA's done. These vices are very much not limited to one people or one culture, unfortunately.

2 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

ਜੰਗ ਮੁੱਦਕੀ ਦਾ । ਜੰਗ ਹਿੰਦ ਤੇ ਪੰਜਾਬ ਦਾ ।First Sikh Anglo war | Battle of M...

0 notes

Text

History

December 11, 1845 - The first Anglo-Sikh War in India began as the Sikhs attacked British colonial forces. The Sikhs were defeated after four battles. Part of the Punjab region of northwestern India was then annexed by the British.

December 11, 1901 - The first transatlantic radio signal was transmitted by Guglielmo Marconi from Cornwall, England, to St. John's, Newfoundland.

December 11, 1936 - King Edward VIII abdicated the throne of England to marry "the woman I love," a twice-divorced American named Wallis Warfield Simpson. They were married in France on June 3, 1937, and then lived in Paris.

December 11, 1941 - A major turning point in World War II occurred as Japan's Axis partners, Italy and Germany, both declared war on the United States. The U.S. Congress immediately declared war on them. President Roosevelt then made the defeat of Hitler the top priority, devoting nearly 90 percent of U.S. military resources to the war in Europe.

December 11, 1994 - Russia sent tanks and troops into Chechnya to end the rebel territory's three-year drive for independence.

December 11, 1998 - The House Judiciary Committee approved three articles of impeachment charging President Bill Clinton with perjury and obstruction of justice.

Birthday - New York Mayor Fiorello H. LaGuardia (1882-1947) was born in New York City. A beloved, gregarious politician, "The Little Flower" (the meaning of Fiorello) served as a U.S. Congressman and was then elected three times as mayor of New York City beginning in 1933. He was a liberal Republican who supported organized labor, women's rights and child labor laws. As mayor of New York, he reformed the city government and battled corruption, but kept his sense of humor. "When I make a mistake it's a beaut!" he once joked.

0 notes

Text

Hari Singh Nalwa - A Prominent Military Commander of the Sikh Empire

Hari Singh Nalwa was a prominent military commander and general of the Sikh Empire in northern India, during the rule of Maharaja Ranjit Singh. He served as the Commander-in-Chief of the Sikh Khalsa Army and was known for his bravery, military tactics, and administrative skills. He fought in several battles and campaigns, including the First Anglo-Sikh War, and expanded the boundaries of the Sikh…

View On WordPress

#administrative skills#Afghan Empire#Attock#Battle of Jamrud#bravery#chronic illness#Conquest of Peshawar#First Anglo-Sikh War#Gujranwala#Hari Singh Nalwa#hero#India#Indian History#Jamrud#Jatt family#legacy#Maharaja Ranjit Singh#mid-to-late 40s#Military Commander#military tactics#Muslim forces#Nowshera#Pakistan#political realities#Sardar Chatha#Sikh Empire

0 notes

Text

Queen Camilla's coronation crown has been revealed, and it won't feature the divisive Koh-i-Nûr Tuesday, Buckingham Palace announced that the 75-year-old Queen Consort, who will be crowned with Queen Mary's Crown during the May 6 ceremony beside her husband, King Charles, whose spectacular sparkler is set with 2,200 diamonds and was commissioned by Charles' great-grandmother Mary for the 1911 coronation of her husband, King George V.

The choice avoids the Koh-i-Nûr diamond, a staggering 105.6-carat stone believed to be one of the world's most extensive cuts that were featured in the Queen Mother's coronation crown, which she wore to the 1937 coronation of her husband, King George VI, and the 1953 coronation of her daughter, Queen Elizabeth II.

According to Historic Royal Palaces, the disputed gem is viewed as a "symbol of conquest" and was taken into British possession by the East India Company in the form of a diamond from 10-year-old Maharaja Duleep Singh, the last ruler of the Sikh empire, who surrendered it to Queen Victoria as part of the peace treaty at the end of the First Anglo-Sikh War and has remained in the royal vault ever since, despite periodic calls for it to be returned to India.

"Opposing legends have maintained that the diamond is both lucky and unlucky," Historical Royal Palaces states.

As plans for the coronation of King Charles and Queen Camilla began to take shape in the fall, it was speculated that the Queen Consort might wear the Queen Mother's coronation crown for the religious ritual very close to his grandmother, and reports swirled that the regal headpiece had always been earmarked for Camilla.

Calling back to the Koh-i-Nûr diamond's problematic past, a source from the Bharatiya Janata Party in India told The Telegraph in October, "The coronation of Camilla and the use of the crown jewel Koh-i-Nûr bring back painful memories of the very little memory of the oppressive past when six generations of Indians suffered under multiple foreign rules for over five centuries," the source said, "but the coronation of the new Queen Camilla and the use of the Koh-i-Nûr do transport a few Indians back to the days of the British Empire in India."

Queen Mary's coronation crown originally used the Koh-i-Nûr diamond for the 1911 coronation, as did Queen Alexandra's crown for the coronation of 1902, according to the Royal Collection Trust.

When the Queen Mother had her crown commissioned for the coronation of 1937, she had the giant diamond removed from Queen Mary's crown for her own, as her mother-in-law had done before her.

Instead of the Koh-i-Nûr diamond, Queen Camilla's crown is currently being worked on to set the Cullinan III, IV, and V diamonds that were part of Queen Elizabeth II's collection and frequently worn as brooches by the Royal Collection Trust.

"In 1907, the Cullinan was presented to King Edward VII by the Government of the Transvaal," the Royal Collection Trust explains, as a symbolic gesture intended to heal the rift between Britain and South Africa following the Boer King's acceptance of the gift on the recommendation of being taken under heavy police escort to Sandringham and formally presented on the king's table in nine pieces, which were numbered. King George V had Cullinan I and II set in the Sovereign's Sceptre and Imperial State Crown, where the stones from the Crown, Sovereign's Sceptre, and Sovereign's Orb were all used during the September 2022 funeral of Queen Elizabeth.

According to the Royal Collection Trust, the remaining numbered diamonds were kept by Asschers, the company that cut the diamond, and VIII was later brought privately by King Edward VII as a gift for Queen Alexandra; others were acquired by the South African Government and given to Queen Mary in 1910 "in memory of the Inauguration of the Union," and were bequeathed to Queen Elizabeth II in 1953.

0 notes

Photo

The Armies of the East India Company

The East India Company (EIC) was first England's and then Britain's tool of colonial expansion in India and beyond. Revenue from trade and land taxes from territories it controlled allowed the EIC to build up its own private armies, collectively the largest armed force in South and South East Asia.

The EIC mixed British and Indian soldiers (sepoys), hired regular regiments of the British Army, and funded its own navy, the Bombay Marine. The vast resources of the company allowed it to eventually employ over 250,000 well-trained and well-equipped fighting men. This force expanded the EIC's domains, seeing off competition from Indian princely states, pirates, and other European trade companies.

From Trade to Imperialism

The East India Company was founded as a joint stock company by royal charter on 31 December 1600. Initially, the company limited itself to trade from centres or 'factories' it set up at already established ports belonging to the Mughal Empire (1526-1858) in India. From 1668, Bombay (Mumbai) became the EIC's main trade hub after it was acquired from the Portuguese Empire. By the end of the century, the EIC had a major presence at Madras, Calcutta (Kolkata), and Hughli in Bengal amongst others. These early arrangements were entirely peaceful, but the EIC wanted more control and more power that would give even greater returns to its private investors.

It was in the mid-18th century that the EIC gained the right through a royal charter to raise its own army, principally in order to protect its assets like warehouses and man its fortifications. From 1757, the EIC used this army in an aggressive campaign of conquest. The EIC thus began to control territory of its own, and in 1759, it took over the major port of Surat completely. Essentially, the EIC was now the "sharp end of the British imperial stick" (Faught, 6). A key step in this transformation from trader to imperialist was victory against Shah Alam II, the Mughal emperor, and Mir Qasim, Nawab of Awadh at the Battle of Buxar in 1764. In a 1765 peace treaty, Shah Alam II awarded the EIC the right to collect land revenue (dewani) in Bengal, Bihar, and Orissa. This was a major development and ensured the company now had vast resources to fund an army for further territorial expansion.

Men like Robert Clive (1725-1774) carved out an empire in the EIC's name. Clive of India, as he was popularly known, rose from clerk to Governor of Bengal and secured a famous victory in June 1757 at the Battle of Plassey against the forces of the Nawab of Bengal. Clive defeated a larger enemy force where the wealth of the EIC was seen in the disparity of artillery pieces: 50 against the EIC's 171. More territory came after the Four Anglo-Mysore Wars (1767-99) and the two Anglo-Sikh Wars (1845-49). These territories had to be protected against various Indian princely states, the Mughal Empire, the Marathas, the Mysores, and rivals such as the Dutch East India Company (VOC), founded in 1602, and the French East India Company, founded in 1664. These European bodies had armies as well-equipped as the EIC forces, and so the British expansion was not entirely a smooth one. For example, the French twice took possession of Madras and controlled large parts of southern India. It is no surprise then, given these challenges, that by the end of the 18th century, the EIC was spending half its income on military personnel and hardware.

Continue reading...

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

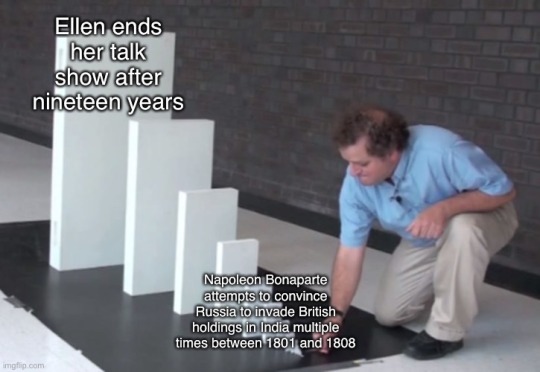

So really, if you want the full historical context it’s more like

#photo#cuz Napoleon’s attempts were the earliest things that got Britain paranoid#which led to the great game between Britain and Russia for most of the 19th century#which led to the first Anglo-Afghan war#the first Anglo-Sikh war#the second Anglo-Sikh war#the second Anglo-Afghan war#Afghanistan becoming a British protectorate#the third Anglo-Afghan war in the midst of WW1 leading to Afghanistan’s independence#Afghanistan becoming a republic in 1973 after 54 years as a kingdom#the Soviet invasion that led to US covert support of the Mujhadeen that became the Taliban#and THEN 9/11#history#long post

102K notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

The First Anglo Sikh War: Part 1, The Rise of the Sikh Empire How did the Sikhs become such an important power in India and who...

#history#military history#first anglo-sikh war#amarpal sidhu#redcoat: british military history#youtube

21 notes

·

View notes

Photo

“On 10 August 1851, in Moulmein, the capital of British Burma, a gang of one hundred Indian convicts was engaged in its routine monthly task of loading coal onto the East India Company's paddle steamer HC Tenasserim, at the docks of Mopoon. This ship was one of many that plied the Company's trading routes around the Bay of Bengal, connecting port cities in South and South East Asia. Like other Company steamers, the HC Tenasserim carried a diverse cargo. This included men, women, and children – Company officials with their families and servants, merchants and traders, military officers and troops, and labourers – and trade goods like cotton, spices, pepper, opium, and betel nut. In common with other such vessels, the Tenasserim also routinely conveyed Indian transportation convicts into sentences of penal labour. Port cities like Moulmein, one such carceral site, were key locations through and in which the Company repressed and put to work colonized populations. They were places in which convicts joined other colonial workers in the formation of a remarkably cosmopolitan labour force.

The Moulmein convicts working in the docks of Mapoon had, in the early hours of the day, marched the three miles between their jail and the coal shed wharf. The deputy jailer, Mr Edwards, with twenty-six guards, had supervised their work, with a half dozen armed reserve stationed a short distance away. As usual, the convicts were close to finishing the task by the early afternoon. But this was no ordinary day in Moulmein. Just as they were finishing loading the boat, nineteen of the convicts grabbed three of the lascars (sailors) who were holding the ropes tethering the ship to the riverbank and threw them overboard. Their guards approached, but other convicts kept them back by pelting them with lumps of coal. The rest let go of the ropes and pushed the boat off. With Moulmein sitting at the southern confluence of the point at which the Salween River splits into four, they set sail north towards Martaban and got behind their oars, with both the wind and the flood tide in their favour. If port cities were places of convict repression and coerced labour, they were also always potential spaces of collective rebellion. Immediately, deputy jailer Edwards ordered a party to set off along the river in pursuit of the convicts. It quickly caught them up, for the coal boat was heavy, and managed to board the steamer and recapture the men. Despite the convicts’ capitulation, the reaction of the guards was brutal. They killed three men, and wounded eleven, who suffered dreadful and multiple injuries, including sabre wounds, fractured skulls, and broken legs.

Most of the convicts involved in the 1851 outbreak in Moulmein... were from the Punjab, which the Company had annexed in 1849 following its victory in the first and second Anglo-Sikh Wars of 1845–1846 and 1848–1849. In the aftermath of these wars, the British convicted, jailed, and transported dozens of former soldiers to mainland prisons or penal settlements in South East Asia, many under charges of “treason”. These military men were well trained, drilled, and experienced in handling weapons. In later years, particularly after remaining loyal to the East India Company during the Indian rebellion of 1857, the British came to favour men of this region for employment in both the Bengal army and the Indian police service. They constituted one of India's “martial castes”, for their alleged physical superiority and military prowess. During the intervening decade, however, they were certainly not preferred prisoners or transports. Defeated, demoralized, and dispossessed, Punjabi soldier convicts carried anti-imperial sentiment with them into transportation, and agitated continuously against their penal confinement, sometimes in concert with ordinary convicts.

In Burma, for instance, convicts organized mass escapes after a general tightening up of discipline, including the introduction of common messing. The new rules prescribed that convicts should cook and eat their rations together, rather than in self-selecting groups, according to their own desires or cultural and religious imperatives. In November 1846, convicts attempted to break out, and when they failed instead burnt down their wards and guard rooms. A month later, a road gang of 120 mounted but did not succeed in another mass escape attempt. Clearly pre-organized, the jemadar (head overseer) heard one convict say to another shortly before giving the signal to attack the tindals (overseers), “Are you ready?” The commissioner of Arakan claimed that the outbreak was at least partly the consequence of the convicts’ knowledge that he had no power to sanction them, for they were already subject to the severe punishment of hard labour in chains for life. In 1849, there was a mutiny at the Moulmein coal depot in Mopoon. One hundred convicts employed in preparing coal for delivery to the Company steamer rose against their guards. They, too, failed in their bid to escape, with the Company guard killing three and severely wounding eight men in an effort to prevent their flight. British commissioner Bogle reported: “the Secks had […] bound themselves by an Oath never to return to the prison and to eat beef sooner than abandon their purpose […] Bold men will ever be found keen to emancipate themselves from thraldom, and when determined upon it, they are not to be restrained […]”.

The following year, 1850, a military general named Narain Singh led a violent mutiny among thirty-nine convicts on board a river steamer on the way to Alipur jail, in Calcutta, which was the holding depot for transportation to Burma. After quelling the outbreak, and securing the convicts, they continued to plot their escape, including in prison stops along the way. There were significant logistical challenges both in moving convicts securely into transportation, and in keeping them to labour in relatively open environments, which often bordered rivers or the sea. This was of course most notably the case in ports. Though convicts failed in their bid for freedom on that occasion, there and in the other cases noted above, their penal mobility – across land, along water, and in outdoor working gangs – put them into close physical contact, which was necessary for the planning of collective action. Paradoxically, whilst the Company effected transportation as a punishment, it also put into motion the spread of rebellious sentiments to the port cities of South East Asia.

The penal transportation of the soldiers of a defeated army following the Anglo-Sikh Wars was entirely consistent with Company justice, which can be dated in this regard to the turn of the nineteenth century. Following the loss of their kingdom during the wars of 1799–1801, Polygar chiefs, for instance, were shipped by the British from south India to both Fort William (Calcutta) and Penang. Repressive penal transportations also followed the final crushing of the Chuar rebellion in 1816, the second and third Maratha Wars (1803–1805, 1816–1819), the Kol revolt of 1831, the 1835 Ghumsur war against the Konds in Orissa, the 1844 anti-Company revolt in the princely state of Kolhapur, and the Santal hul (rebellion) of 1855. During this entire period, the East India Company also used transportation to expel peasant rebels, particularly low caste and tribal subjects resistant to the Company's occupation of land, extraction of natural resources (notably the timber used for railway sleepers), and taxation regime.

The political convicts of Company Asia joined forces with ordinary, “criminal” convicts to resist their situation at every turn. In 1816, for instance, a dozen convicts rose up and escaped from the Bel Ombre plantation in Mauritius. Some of these men had been sepoys (soldiers), others were low-caste Kols or Chuars who had been convicted of offences relating to peasant rebellion in the Bengal Presidency. They had been confined together to await their transportation in Calcutta's Alipur jail, where a few of the men had been involved in serious riots and were transported in groups on three separate transportation ships. These men were religious rebels of sorts, protesting against the contravention of caste norms regarding the sharing of cooking and eating pots. They stole weapons and escaped into the mountains, allegedly joining a band of maroon (runaway) slaves. In the ensuing trial at the Court of Assizes, they called each other camarade (in French or Mauritian Kreol, comrade) or bhai (Hindustani for brother). Kolhapur rebels transported to Aden in the mid-1840s likewise led repeated escape attempts, including one collective effort in which Company guards shot dead three convicts, whilst at least ten others drowned in their bid to escape.

Though it succeeded in the expulsion of undesirable imperial subjects, transportation failed as a means of containing anti-imperial sentiment and action. Rather, it facilitated its spread, with subaltern action often turning on the same socio-political grievances that had underpinned convicts’ initial transportation. As noted above, the close confinement of convicts’ river journeys enabled them to plot collective action. The same was true of sea voyages, and there were over a dozen convict mutinies in the period to 1857. Many were both effected and repressed with spectacular levels of violence. The largest of all was the seizure of the Clarissa by more than one hundred convicts in 1854. This failed when the convicts ran aground off the coast of Burma and attempted to sign a treaty with a local ruler, in the false belief that he was holding out against the East India Company. In fact, he had already signed a treaty with the British. In regard to the importance of often long journeys into transportation as spaces of rebellion, it is significant that the Company often referred to transportation convicts as transmarine, that is to say, from the other side of the sea. This connected together convicts’ place of origin to their journeys and destinations in a way that suggested, implicitly at least, a close relationship between the three.

The 1857 revolt in India proved a turning point in the history of Indian convict transportation, as the British recognized and feared the consequence of the spread of transregional solidarities of resistance in their Asian settlements. One of the Punjabi convicts sent to Singapore following the Second Anglo-Sikh War, for example, Nihal Singh, had led anti-British forces and was widely regarded as a “saint-soldier”, known by the honorific title Bhai Maharaj (“brother ruler”) Singh. The British deputy commissioner wrote at the time: “He is to the Natives what Jesus Christ is to the most zealous of Christians. His miracles were seen by tens of thousands, and are more implicitly relied on, than those worked by the ancient prophets […] This man who was a God, is in our hands”. Afraid of his influence in the cosmopolitan working environment of the port, the British did not put Nihal Singh to ordinary labour, and attempted to keep him away from both convicts and free workers. He had been transported to Singapore with Khurruck Singh, who the British described as his “disciple”. By the time of the outbreak of rebellion in 1857 Nihal Singh had died, but the British expressed grave anxieties about Khurruck Singh's influence on the convicts and Indians then in Singapore. The British had formerly allowed him to live at large, under police surveillance, and he had gone to live with a free Parsee spice merchant. After the outbreak of revolt in the mainland, however, the governor of the Straits Settlements ordered his confinement in the civil jail, and no longer allowed him freedom of movement. Meantime, fearing revolutionary contamination, they evacuated all the “Sikh” convicts then in Singapore, some to the penal settlement of Penang.

In the port city of Moulmein, too, the British feared the spread of rebellion. In July 1857, the superintendent of the jail reported that the convicts possessed “a most unsteady feeling”. A shipload of fifty convicts had arrived on the Fire Queen, bringing, he claimed, “exaggerated stories” with them. The Company had put them in heavy chains, and in distinction to routine transportation practice they were guarded by Europeans, not Indians. The officiating commissioner refused to land them, however, directing them back to Calcutta. He wrote that, like the newly arrived convicts, the jail peons and town police were nearly all “up countrymen” (i.e. from northern India). Moreover, there were 250 ticket-of-leave convicts in the port. “From conversations which have been overheard”, he reported, “it is not impossible that they and a portion of the Mahomedan population of the Town might form a collusion for a general outbreak of the Jail”. This fear was certainly not groundless, for one of the key features of the 1857 revolt was the breaking open of prisons. The consequence of this alliance between rebels and prisoners was the serious damage or destruction of over forty jails, and the escape of over 20,000 inmates.” - Clare Anderson, “Convicts, Commodities, and Connections in British Asia and the Indian Ocean, 1789–1866.” International Review of Social History, Volume 64, Special Issue S27 (Free and Unfree Labor in Atlantic and Indian Ocean Port Cities (1700–1850)). April 2019 , pp. 205-227.

Image is: “Arracan [Arakan] 14th February [1849] Kyook Phoo [Kyaukpyu] Ghat & Prisoners Carrying Water in Buckets, Isle of Ramree.” Watercolour by Clementina Benthall. Benthall Papers, Centre of South Asian Studies, University of Cambridge.

#burma#british empire#moulmein#prison riot#prisoner resistance#convict revolt#convict transportation#penal colony#prisoner solidarity#east india company#british imperialism#punjab#colonial rebellion#indian history#burmese history#indian mutiny#crime and punishment#history of crime and punishment#arakan#calcutta#penang

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Events 1.22 (before 1950)

613 – Eight-month-old Constantine is crowned as co-emperor (Caesar) by his father Heraclius at Constantinople. 871 – Battle of Basing: The West Saxons led by King Æthelred I are defeated by the Danelaw Vikings at Basing. 1506 – The first contingent of 150 Swiss Guards arrives at the Vatican. 1517 – The Ottoman Empire under Selim I defeats the Mamluk Sultanate and captures present-day Egypt at the Battle of Ridaniya. 1555 – The Ava Kingdom falls to the Taungoo Dynasty in what is now Myanmar. 1689 – The Convention Parliament convenes to determine whether James II and VII, the last Roman Catholic monarch of England, Ireland and Scotland, had vacated the thrones of England and Ireland when he fled to France in 1688. 1808 – The Portuguese royal family arrives in Brazil after fleeing the French army's invasion of Portugal two months earlier. 1824 – The Ashantis defeat British forces in the Gold Coast. 1849 – Second Anglo-Sikh War: The Siege of Multan ends after nine months when the last Sikh defenders of Multan, Punjab, surrender. 1863 – The January Uprising breaks out in Poland, Lithuania and Belarus. The aim of the national movement is to regain Polish–Lithuanian–Ruthenian Commonwealth from occupation by Russia. 1879 – The Battle of Isandlwana during the Anglo-Zulu War results in a British defeat. 1879 – The Battle of Rorke's Drift, also during the Anglo-Zulu War and just some 15 km (9.3 mi) away from Isandlwana, results in a British victory. 1890 – The United Mine Workers of America is founded in Columbus, Ohio. 1901 – Edward VII is proclaimed King of the United Kingdom after the death of his mother, Queen Victoria. 1905 – Bloody Sunday in Saint Petersburg, beginning of the 1905 revolution. 1906 – SS Valencia runs aground on rocks on Vancouver Island, British Columbia, killing more than 130. 1915 – Over 600 people are killed in Guadalajara, Mexico, when a train plunges off the tracks into a deep canyon. 1917 – American entry into World War I: President Woodrow Wilson of the still-neutral United States calls for "peace without victory" in Europe. 1919 – Act Zluky is signed, unifying the Ukrainian People's Republic and the West Ukrainian National Republic. 1924 – Ramsay MacDonald becomes the first Labour Prime Minister of the United Kingdom. 1927 – Teddy Wakelam gives the first live radio commentary of a football match, between Arsenal F.C. and Sheffield United at Highbury. 1941 – World War II: British and Commonwealth troops capture Tobruk from Italian forces during Operation Compass. 1943 – World War II: Australian and American forces defeat Japanese army and navy units in the bitterly fought Battle of Buna–Gona. 1944 – World War II: The Allies commence Operation Shingle, an assault on Anzio and Nettuno, Italy. 1946 – In Iran, Qazi Muhammad declares the independent people's Republic of Mahabad at Chahar Cheragh Square in the Kurdish city of Mahabad; he becomes the new president and Haji Baba Sheikh becomes the prime minister. 1946 – Creation of the Central Intelligence Group, forerunner of the Central Intelligence Agency. 1947 – KTLA, the first commercial television station west of the Mississippi River, begins operation in Hollywood.

0 notes