#First Anglo-Sikh War

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Treaty of Lahore

9 ਮਾਰਚ 1846 ਈਸਵੀ! ਪਹਿਲੀ ਸਿੱਖ ਅੰਗਰੇਜ਼ ਲੜਾਈ ਤੋਂ ਬਾਅਦ ਦੋਨਾਂ ਸਰਕਾਰਾਂ ਵਿੱਚ 9 ਮਾਰਚ 1846 ਈਸਵੀ ਨੂੰ ਸੁਲ੍ਹਾ ਨਾਮਾ ਹੋਇਆ; ਜਿਸ ਤੇ ਅੰਗਰੇਜ਼ਾਂ ਵੱਲੋਂ ਫਰੈਡਰਿਕ ਕਰੀ , ਹੈਨਰੀ ਲਾਰੰਸ ਆਦਿ ਸਨ ਤੇ ਲਾਹੌਰ ਦਰਬਾਰ ਵੱਲੋਂ ਭਾਈ ਰਾਮ ਸਿੰਘ, ਲਾਲ ਸਿੰਘ, ਤੇਜ ਸਿੰਘ, ਭਾਈ ਚਤਰ ਸਿੰਘ ਅਟਾਰੀਵਾਲਾ, ਰਣਜੋਧ ਸਿੰਘ ਮਜੀਠਾ, ਦੀਵਾਨ ਦੀਨਾ ਨਾਥ ਅਤੇ ਫ਼ਕੀਰ ਨੂਰਦੀਨ ਆਦਿ ਨੇ ਦਸਤਖ਼ਤ ਕੀਤੇ ਸਨ ! ਇਸ ਸੰਧੀ ਦੇ ਨਾਮ ਤੇ ਗੋਰਾ ਸ਼ਾਹੀ ਨੇ ਰੱਜ ਕੇ ਨਬਾਲਿਗ ਮਹਾਰਾਜੇ ਨਾਲ ਬੇਇਨਸਾਫ਼ੀ ਕੀਤੀ ; ਜਿਸ…

View On WordPress

#Anglo-Sikh war#first#Gursikh satth media#lahore#nimana#Punjab#sikh#sikhism#singh#Treaty#treaty of lahore

0 notes

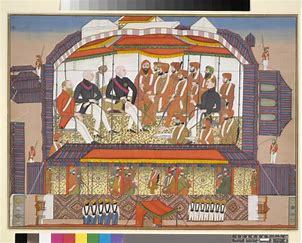

Photo

Second Anglo-Sikh War

The Second Anglo-Sikh War (1848-9) once again saw the British East India Company defeat the Sikh Empire in northern India. The war, which started off as a rebellion against British colonial rule, included the high-casualty Battle of Chillianwala, but the conflict was finally won by the EIC with a decisive victory at the Battle of Gujrat in February 1849.

The EIC & the Sikh Empire

The British East India Company had been grabbing territory since its victories at the 1757 Battle of Plassey and the 1764 Battle of Buxar, which gave the British a vast and regular income in local taxes, besides other riches. The EIC kept on expanding and defeated the southern Kingdom of Mysore in the three Anglo-Mysore Wars (1767-1799) and the Maratha Confederacy of Hindu princes in central and northern India in the three Anglo-Maratha Wars (1775-1819). Next came expansion in the far northeast and more victories in the Anglo-Nepalese War (1814-1815) and the three Anglo-Burmese Wars (1824-1885). The next and final target of the EIC was northwest India and the Punjab, the heartland of the Sikh Empire.

The Punjab, located in the northwest of the Indian subcontinent, is an area which today covers parts of Pakistan and India. The Sikh Empire had risen due to the gradual decline of the Mughal Empire (1526-1857). Sikh territories were divided between 12 misls or armies, each led by a chief who collectively formed a loose confederation. The greatest of Sikh leaders was Ranjit Singh (1780-1839), the 'Lion of Lahore'. He forged the Sikh Empire by modernising the army and conquering Multan and Kashmir (1819), Ladakh (1833), and Peshawar (1834). This expansion rang alarm bells in the offices of the East India Company, especially after their failure in the First Anglo-Afghan War (1838-42) to the north.

In 1839, the Sikhs, Afghans, and British signed a treaty to protect existing borders. Ranjit Singh died in June 1839, and political turmoil weakened the Sikh government's control over its own army. Rajit Singh's youngest son, Duleep Singh (l. 1838-1893), was selected as the new Sikh ruler in 1843, but as he was but a child, his mother, Jind Kaur (aka Rani Jindan, d. 1863), ruled as regent. Jind Kaur supported a military escapade against the British since, even if the Sikhs lost, this would cut the army down to size, perhaps ending the interference of the generals in government affairs and certainly reducing the threat of a military coup.

The EIC exploited the turmoil and conquered the Sindh province (southwest of the Punjab) in 1843. Confident that some of the Sikh misls in the east supported closer ties with the EIC, the British prepared for war in the Punjab and amassed an army of 40,000 men to the southeast of the Sikh state. In the wider world of empires, the British no longer considered the Sikh Empire a useful buffer zone in case of expansion of the Russian Empire into Afghanistan and northern India – the so-called Great Game. The Sikhs would now have to fight the seemingly unstoppable armies of the East India Company.

Continue reading...

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

Maharani Jind Kaur

Maharani Jind Kaur, also known as Rani Jindan, was a significant figure in Sikh history, serving as the last queen of the Sikh Empire from 1843 to 1846. Born in 1817 in Gujranwala, she became the youngest wife of Maharaja Ranjit Singh, the founder of the Sikh Empire. After Ranjit Singh's death in 1839, Jind Kaur took on the role of regent for her son, Maharaja Duleep Singh. Jind Kaur's reign as regent was marked by political turmoil and conflict with the British East India Company. In 1845, during the First Anglo-Sikh War, she dispatched the Sikh Army to confront the British, leading to the annexation of the entire Punjab in 1849. After her son's dethronement, she faced imprisonment and exile by the British. Despite challenges, Jind Kaur escaped captivity in 1849, disguising herself as a slave girl and finding refuge in Nepal. Her efforts to resist British dominance continued through correspondence with rebels in Punjab and Jammu-Kashmir. She later reunited with her son in Calcutta in 1861, influencing him to return to Sikhism. Jind Kaur's exile took a toll on her health, and she passed away in her sleep on August 1, 1863, in Kensington, England. Denied the opportunity to be cremated in Punjab, her ashes were eventually brought back to India in 1924 and reburied in the Samadhi of Maharaja Ranjit Singh in Lahore. Despite her challenging life and exile, Maharani Jind Kaur's legacy endures as a symbol of resilience and resistance against colonial rule. In 2009, a memorial plaque was unveiled at the Kensal Green Dissenters Chapel, honouring her contributions to Sikh history.

#sikh empire#jind kaur#mahrani jind kaur#maharaja duleep singh#duleep singh#history#women in history#indian women in history#colonialism#british imperialism#indian royalty

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sword from India dated to the 17th Century on display at the Highlander's Museum in Inverness, Scotland

This sword was presented to Sir Patrick Grant during the First Anglo-Sikh War (1845 - 1846) where he fought for the British East India Company. It is said to have belonged to a soldier in the service of Shah Jhan, a Mughal Emperor from the 17th century.

Such weapons were often taken by East India Company and British soldiers during the expansionist wars in India. They were briught back to Britain as symbols of conquest for museums or private collections.

Photographs taken by myself 2024

#art#military history#sword#17th century#mughal empire#india#indian#early modern period#highlanders museum#inverness#barbucomedie

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Events 12.6 (before 1950)

1060 – Béla I is crowned king of Hungary. 1240 – Mongol invasion of Rus': Kyiv, defended by Voivode Dmytro, falls to the Mongols under Batu Khan. 1492 – After exploring the island of Cuba for gold (which he had mistaken for Japan), Christopher Columbus lands on an island he names Hispaniola. 1534 – The city of Quito in Ecuador is founded by Spanish settlers led by Sebastián de Belalcázar. 1648 – Pride's Purge removes royalist sympathizers from Parliament so that the High Court of Justice could put the King on trial. 1704 – Battle of Chamkaur: During the Mughal-Sikh Wars, an outnumbered Sikh Khalsa defeats a Mughal army. 1745 – Charles Edward Stuart's army begins retreat during the second Jacobite Rising. 1790 – The U.S. Congress moves from New York City to Philadelphia. 1803 – Five French warships attempting to escape the Royal Naval blockade of Saint-Domingue are all seized by British warships, signifying the end of the Haitian Revolution. 1865 – Georgia ratifies the 13th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution. 1882 – Transit of Venus, second and last of the 19th century. 1884 – The Washington Monument in Washington, D.C., is completed. 1897 – London becomes the world's first city to host licensed taxicabs. 1904 – Theodore Roosevelt articulated his "Corollary" to the Monroe Doctrine, stating that the U.S. would intervene in the Western Hemisphere should Latin American governments prove incapable or unstable. 1907 – A coal mine explosion at Monongah, West Virginia, kills 362 workers. 1912 – The Nefertiti Bust is discovered. 1916 – World War I: The Central Powers capture Bucharest. 1917 – Finland declares independence from the Russian Empire. 1917 – Halifax Explosion: A munitions explosion near Halifax, Nova Scotia kills more than 1,900 people in the largest artificial explosion up to that time. 1917 – World War I: USS Jacob Jones is the first American destroyer to be sunk by enemy action when it is torpedoed by German submarine SM U-53. 1921 – The Anglo-Irish Treaty is signed in London by British and Irish representatives. 1922 – One year to the day after the signing of the Anglo-Irish Treaty, the Irish Free State comes into existence. 1928 – The government of Colombia sends military forces to suppress a month-long strike by United Fruit Company workers, resulting in an unknown number of deaths. 1933 – In United States v. One Book Called Ulysses Judge John M. Woolsey rules that James Joyce's novel Ulysses is not obscene despite coarse language and sexual content, a leading decision affirming free expression. 1941 – World War II: Camp X opens in Canada to begin training Allied secret agents for the war.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

also. so many actual heirlooms were looted from us. so many people were looted by the british. and like i'm sorry but lieutenant-general maharaja sir bhupinder singh, gcsi, gcie, gcvo, gbe, gcsg, owner of 44 rolls royces, master of a harem of 350 concubines, client of the largest cartier order of the time while everyone else was starving in a post-wwi economy, first indian to own a private plane, staunch supporter of the british raj and ally to the east india company in the first anglo-sikh war, was not "looted".

#diljit dosanjh#even if the british didn't exist even if we weren't colonized we STILL would not have access to these pieces#yknow why? because 'we' were working the farms.

0 notes

Video

youtube

ਜੰਗ ਮੁੱਦਕੀ ਦਾ । ਜੰਗ ਹਿੰਦ ਤੇ ਪੰਜਾਬ ਦਾ ।First Sikh Anglo war | Battle of M...

0 notes

Text

History

December 11, 1845 - The first Anglo-Sikh War in India began as the Sikhs attacked British colonial forces. The Sikhs were defeated after four battles. Part of the Punjab region of northwestern India was then annexed by the British.

December 11, 1901 - The first transatlantic radio signal was transmitted by Guglielmo Marconi from Cornwall, England, to St. John's, Newfoundland.

December 11, 1936 - King Edward VIII abdicated the throne of England to marry "the woman I love," a twice-divorced American named Wallis Warfield Simpson. They were married in France on June 3, 1937, and then lived in Paris.

December 11, 1941 - A major turning point in World War II occurred as Japan's Axis partners, Italy and Germany, both declared war on the United States. The U.S. Congress immediately declared war on them. President Roosevelt then made the defeat of Hitler the top priority, devoting nearly 90 percent of U.S. military resources to the war in Europe.

December 11, 1994 - Russia sent tanks and troops into Chechnya to end the rebel territory's three-year drive for independence.

December 11, 1998 - The House Judiciary Committee approved three articles of impeachment charging President Bill Clinton with perjury and obstruction of justice.

Birthday - New York Mayor Fiorello H. LaGuardia (1882-1947) was born in New York City. A beloved, gregarious politician, "The Little Flower" (the meaning of Fiorello) served as a U.S. Congressman and was then elected three times as mayor of New York City beginning in 1933. He was a liberal Republican who supported organized labor, women's rights and child labor laws. As mayor of New York, he reformed the city government and battled corruption, but kept his sense of humor. "When I make a mistake it's a beaut!" he once joked.

0 notes

Text

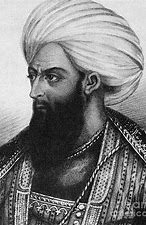

Hari Singh Nalwa - A Prominent Military Commander of the Sikh Empire

Hari Singh Nalwa was a prominent military commander and general of the Sikh Empire in northern India, during the rule of Maharaja Ranjit Singh. He served as the Commander-in-Chief of the Sikh Khalsa Army and was known for his bravery, military tactics, and administrative skills. He fought in several battles and campaigns, including the First Anglo-Sikh War, and expanded the boundaries of the Sikh…

View On WordPress

#administrative skills#Afghan Empire#Attock#Battle of Jamrud#bravery#chronic illness#Conquest of Peshawar#First Anglo-Sikh War#Gujranwala#Hari Singh Nalwa#hero#India#Indian History#Jamrud#Jatt family#legacy#Maharaja Ranjit Singh#mid-to-late 40s#Military Commander#military tactics#Muslim forces#Nowshera#Pakistan#political realities#Sardar Chatha#Sikh Empire

4 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

The First Anglo Sikh War: Part 1, The Rise of the Sikh Empire How did the Sikhs become such an important power in India and who...

#history#military history#first anglo-sikh war#amarpal sidhu#redcoat: british military history#youtube

21 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Armies of the East India Company

The East India Company (EIC) was first England's and then Britain's tool of colonial expansion in India and beyond. Revenue from trade and land taxes from territories it controlled allowed the EIC to build up its own private armies, collectively the largest armed force in South and South East Asia.

The EIC mixed British and Indian soldiers (sepoys), hired regular regiments of the British Army, and funded its own navy, the Bombay Marine. The vast resources of the company allowed it to eventually employ over 250,000 well-trained and well-equipped fighting men. This force expanded the EIC's domains, seeing off competition from Indian princely states, pirates, and other European trade companies.

From Trade to Imperialism

The East India Company was founded as a joint stock company by royal charter on 31 December 1600. Initially, the company limited itself to trade from centres or 'factories' it set up at already established ports belonging to the Mughal Empire (1526-1858) in India. From 1668, Bombay (Mumbai) became the EIC's main trade hub after it was acquired from the Portuguese Empire. By the end of the century, the EIC had a major presence at Madras, Calcutta (Kolkata), and Hughli in Bengal amongst others. These early arrangements were entirely peaceful, but the EIC wanted more control and more power that would give even greater returns to its private investors.

It was in the mid-18th century that the EIC gained the right through a royal charter to raise its own army, principally in order to protect its assets like warehouses and man its fortifications. From 1757, the EIC used this army in an aggressive campaign of conquest. The EIC thus began to control territory of its own, and in 1759, it took over the major port of Surat completely. Essentially, the EIC was now the "sharp end of the British imperial stick" (Faught, 6). A key step in this transformation from trader to imperialist was victory against Shah Alam II, the Mughal emperor, and Mir Qasim, Nawab of Awadh at the Battle of Buxar in 1764. In a 1765 peace treaty, Shah Alam II awarded the EIC the right to collect land revenue (dewani) in Bengal, Bihar, and Orissa. This was a major development and ensured the company now had vast resources to fund an army for further territorial expansion.

Men like Robert Clive (1725-1774) carved out an empire in the EIC's name. Clive of India, as he was popularly known, rose from clerk to Governor of Bengal and secured a famous victory in June 1757 at the Battle of Plassey against the forces of the Nawab of Bengal. Clive defeated a larger enemy force where the wealth of the EIC was seen in the disparity of artillery pieces: 50 against the EIC's 171. More territory came after the Four Anglo-Mysore Wars (1767-99) and the two Anglo-Sikh Wars (1845-49). These territories had to be protected against various Indian princely states, the Mughal Empire, the Marathas, the Mysores, and rivals such as the Dutch East India Company (VOC), founded in 1602, and the French East India Company, founded in 1664. These European bodies had armies as well-equipped as the EIC forces, and so the British expansion was not entirely a smooth one. For example, the French twice took possession of Madras and controlled large parts of southern India. It is no surprise then, given these challenges, that by the end of the 18th century, the EIC was spending half its income on military personnel and hardware.

Continue reading...

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

So really, if you want the full historical context it’s more like

#photo#cuz Napoleon’s attempts were the earliest things that got Britain paranoid#which led to the great game between Britain and Russia for most of the 19th century#which led to the first Anglo-Afghan war#the first Anglo-Sikh war#the second Anglo-Sikh war#the second Anglo-Afghan war#Afghanistan becoming a British protectorate#the third Anglo-Afghan war in the midst of WW1 leading to Afghanistan’s independence#Afghanistan becoming a republic in 1973 after 54 years as a kingdom#the Soviet invasion that led to US covert support of the Mujhadeen that became the Taliban#and THEN 9/11#history#long post

102K notes

·

View notes

Photo

“On 10 August 1851, in Moulmein, the capital of British Burma, a gang of one hundred Indian convicts was engaged in its routine monthly task of loading coal onto the East India Company's paddle steamer HC Tenasserim, at the docks of Mopoon. This ship was one of many that plied the Company's trading routes around the Bay of Bengal, connecting port cities in South and South East Asia. Like other Company steamers, the HC Tenasserim carried a diverse cargo. This included men, women, and children – Company officials with their families and servants, merchants and traders, military officers and troops, and labourers – and trade goods like cotton, spices, pepper, opium, and betel nut. In common with other such vessels, the Tenasserim also routinely conveyed Indian transportation convicts into sentences of penal labour. Port cities like Moulmein, one such carceral site, were key locations through and in which the Company repressed and put to work colonized populations. They were places in which convicts joined other colonial workers in the formation of a remarkably cosmopolitan labour force.

The Moulmein convicts working in the docks of Mapoon had, in the early hours of the day, marched the three miles between their jail and the coal shed wharf. The deputy jailer, Mr Edwards, with twenty-six guards, had supervised their work, with a half dozen armed reserve stationed a short distance away. As usual, the convicts were close to finishing the task by the early afternoon. But this was no ordinary day in Moulmein. Just as they were finishing loading the boat, nineteen of the convicts grabbed three of the lascars (sailors) who were holding the ropes tethering the ship to the riverbank and threw them overboard. Their guards approached, but other convicts kept them back by pelting them with lumps of coal. The rest let go of the ropes and pushed the boat off. With Moulmein sitting at the southern confluence of the point at which the Salween River splits into four, they set sail north towards Martaban and got behind their oars, with both the wind and the flood tide in their favour. If port cities were places of convict repression and coerced labour, they were also always potential spaces of collective rebellion. Immediately, deputy jailer Edwards ordered a party to set off along the river in pursuit of the convicts. It quickly caught them up, for the coal boat was heavy, and managed to board the steamer and recapture the men. Despite the convicts’ capitulation, the reaction of the guards was brutal. They killed three men, and wounded eleven, who suffered dreadful and multiple injuries, including sabre wounds, fractured skulls, and broken legs.

Most of the convicts involved in the 1851 outbreak in Moulmein... were from the Punjab, which the Company had annexed in 1849 following its victory in the first and second Anglo-Sikh Wars of 1845–1846 and 1848–1849. In the aftermath of these wars, the British convicted, jailed, and transported dozens of former soldiers to mainland prisons or penal settlements in South East Asia, many under charges of “treason”. These military men were well trained, drilled, and experienced in handling weapons. In later years, particularly after remaining loyal to the East India Company during the Indian rebellion of 1857, the British came to favour men of this region for employment in both the Bengal army and the Indian police service. They constituted one of India's “martial castes”, for their alleged physical superiority and military prowess. During the intervening decade, however, they were certainly not preferred prisoners or transports. Defeated, demoralized, and dispossessed, Punjabi soldier convicts carried anti-imperial sentiment with them into transportation, and agitated continuously against their penal confinement, sometimes in concert with ordinary convicts.

In Burma, for instance, convicts organized mass escapes after a general tightening up of discipline, including the introduction of common messing. The new rules prescribed that convicts should cook and eat their rations together, rather than in self-selecting groups, according to their own desires or cultural and religious imperatives. In November 1846, convicts attempted to break out, and when they failed instead burnt down their wards and guard rooms. A month later, a road gang of 120 mounted but did not succeed in another mass escape attempt. Clearly pre-organized, the jemadar (head overseer) heard one convict say to another shortly before giving the signal to attack the tindals (overseers), “Are you ready?” The commissioner of Arakan claimed that the outbreak was at least partly the consequence of the convicts’ knowledge that he had no power to sanction them, for they were already subject to the severe punishment of hard labour in chains for life. In 1849, there was a mutiny at the Moulmein coal depot in Mopoon. One hundred convicts employed in preparing coal for delivery to the Company steamer rose against their guards. They, too, failed in their bid to escape, with the Company guard killing three and severely wounding eight men in an effort to prevent their flight. British commissioner Bogle reported: “the Secks had […] bound themselves by an Oath never to return to the prison and to eat beef sooner than abandon their purpose […] Bold men will ever be found keen to emancipate themselves from thraldom, and when determined upon it, they are not to be restrained […]”.

The following year, 1850, a military general named Narain Singh led a violent mutiny among thirty-nine convicts on board a river steamer on the way to Alipur jail, in Calcutta, which was the holding depot for transportation to Burma. After quelling the outbreak, and securing the convicts, they continued to plot their escape, including in prison stops along the way. There were significant logistical challenges both in moving convicts securely into transportation, and in keeping them to labour in relatively open environments, which often bordered rivers or the sea. This was of course most notably the case in ports. Though convicts failed in their bid for freedom on that occasion, there and in the other cases noted above, their penal mobility – across land, along water, and in outdoor working gangs – put them into close physical contact, which was necessary for the planning of collective action. Paradoxically, whilst the Company effected transportation as a punishment, it also put into motion the spread of rebellious sentiments to the port cities of South East Asia.

The penal transportation of the soldiers of a defeated army following the Anglo-Sikh Wars was entirely consistent with Company justice, which can be dated in this regard to the turn of the nineteenth century. Following the loss of their kingdom during the wars of 1799–1801, Polygar chiefs, for instance, were shipped by the British from south India to both Fort William (Calcutta) and Penang. Repressive penal transportations also followed the final crushing of the Chuar rebellion in 1816, the second and third Maratha Wars (1803–1805, 1816–1819), the Kol revolt of 1831, the 1835 Ghumsur war against the Konds in Orissa, the 1844 anti-Company revolt in the princely state of Kolhapur, and the Santal hul (rebellion) of 1855. During this entire period, the East India Company also used transportation to expel peasant rebels, particularly low caste and tribal subjects resistant to the Company's occupation of land, extraction of natural resources (notably the timber used for railway sleepers), and taxation regime.

The political convicts of Company Asia joined forces with ordinary, “criminal” convicts to resist their situation at every turn. In 1816, for instance, a dozen convicts rose up and escaped from the Bel Ombre plantation in Mauritius. Some of these men had been sepoys (soldiers), others were low-caste Kols or Chuars who had been convicted of offences relating to peasant rebellion in the Bengal Presidency. They had been confined together to await their transportation in Calcutta's Alipur jail, where a few of the men had been involved in serious riots and were transported in groups on three separate transportation ships. These men were religious rebels of sorts, protesting against the contravention of caste norms regarding the sharing of cooking and eating pots. They stole weapons and escaped into the mountains, allegedly joining a band of maroon (runaway) slaves. In the ensuing trial at the Court of Assizes, they called each other camarade (in French or Mauritian Kreol, comrade) or bhai (Hindustani for brother). Kolhapur rebels transported to Aden in the mid-1840s likewise led repeated escape attempts, including one collective effort in which Company guards shot dead three convicts, whilst at least ten others drowned in their bid to escape.

Though it succeeded in the expulsion of undesirable imperial subjects, transportation failed as a means of containing anti-imperial sentiment and action. Rather, it facilitated its spread, with subaltern action often turning on the same socio-political grievances that had underpinned convicts’ initial transportation. As noted above, the close confinement of convicts’ river journeys enabled them to plot collective action. The same was true of sea voyages, and there were over a dozen convict mutinies in the period to 1857. Many were both effected and repressed with spectacular levels of violence. The largest of all was the seizure of the Clarissa by more than one hundred convicts in 1854. This failed when the convicts ran aground off the coast of Burma and attempted to sign a treaty with a local ruler, in the false belief that he was holding out against the East India Company. In fact, he had already signed a treaty with the British. In regard to the importance of often long journeys into transportation as spaces of rebellion, it is significant that the Company often referred to transportation convicts as transmarine, that is to say, from the other side of the sea. This connected together convicts’ place of origin to their journeys and destinations in a way that suggested, implicitly at least, a close relationship between the three.

The 1857 revolt in India proved a turning point in the history of Indian convict transportation, as the British recognized and feared the consequence of the spread of transregional solidarities of resistance in their Asian settlements. One of the Punjabi convicts sent to Singapore following the Second Anglo-Sikh War, for example, Nihal Singh, had led anti-British forces and was widely regarded as a “saint-soldier”, known by the honorific title Bhai Maharaj (“brother ruler”) Singh. The British deputy commissioner wrote at the time: “He is to the Natives what Jesus Christ is to the most zealous of Christians. His miracles were seen by tens of thousands, and are more implicitly relied on, than those worked by the ancient prophets […] This man who was a God, is in our hands”. Afraid of his influence in the cosmopolitan working environment of the port, the British did not put Nihal Singh to ordinary labour, and attempted to keep him away from both convicts and free workers. He had been transported to Singapore with Khurruck Singh, who the British described as his “disciple”. By the time of the outbreak of rebellion in 1857 Nihal Singh had died, but the British expressed grave anxieties about Khurruck Singh's influence on the convicts and Indians then in Singapore. The British had formerly allowed him to live at large, under police surveillance, and he had gone to live with a free Parsee spice merchant. After the outbreak of revolt in the mainland, however, the governor of the Straits Settlements ordered his confinement in the civil jail, and no longer allowed him freedom of movement. Meantime, fearing revolutionary contamination, they evacuated all the “Sikh” convicts then in Singapore, some to the penal settlement of Penang.

In the port city of Moulmein, too, the British feared the spread of rebellion. In July 1857, the superintendent of the jail reported that the convicts possessed “a most unsteady feeling”. A shipload of fifty convicts had arrived on the Fire Queen, bringing, he claimed, “exaggerated stories” with them. The Company had put them in heavy chains, and in distinction to routine transportation practice they were guarded by Europeans, not Indians. The officiating commissioner refused to land them, however, directing them back to Calcutta. He wrote that, like the newly arrived convicts, the jail peons and town police were nearly all “up countrymen” (i.e. from northern India). Moreover, there were 250 ticket-of-leave convicts in the port. “From conversations which have been overheard”, he reported, “it is not impossible that they and a portion of the Mahomedan population of the Town might form a collusion for a general outbreak of the Jail”. This fear was certainly not groundless, for one of the key features of the 1857 revolt was the breaking open of prisons. The consequence of this alliance between rebels and prisoners was the serious damage or destruction of over forty jails, and the escape of over 20,000 inmates.” - Clare Anderson, “Convicts, Commodities, and Connections in British Asia and the Indian Ocean, 1789–1866.” International Review of Social History, Volume 64, Special Issue S27 (Free and Unfree Labor in Atlantic and Indian Ocean Port Cities (1700–1850)). April 2019 , pp. 205-227.

Image is: “Arracan [Arakan] 14th February [1849] Kyook Phoo [Kyaukpyu] Ghat & Prisoners Carrying Water in Buckets, Isle of Ramree.” Watercolour by Clementina Benthall. Benthall Papers, Centre of South Asian Studies, University of Cambridge.

#burma#british empire#moulmein#prison riot#prisoner resistance#convict revolt#convict transportation#penal colony#prisoner solidarity#east india company#british imperialism#punjab#colonial rebellion#indian history#burmese history#indian mutiny#crime and punishment#history of crime and punishment#arakan#calcutta#penang

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Events 2.10 (before 1940)

1258 – The Siege of Baghdad ends with the surrender of the last Abbasid caliph to Hulegu Khan, a prince of the Mongol Empire. 1306 – In front of the high altar of Greyfriars Church in Dumfries, Robert the Bruce murders John Comyn, sparking the revolution in the Wars of Scottish Independence. 1355 – The St Scholastica Day riot breaks out in Oxford, England, leaving 63 scholars and perhaps 30 locals dead in two days. 1502 – Vasco da Gama sets sail from Lisbon, Portugal, on his second voyage to India. 1567 – Lord Darnley, second husband of Mary, Queen of Scots, is found strangled following an explosion at the Kirk o' Field house in Edinburgh, Scotland, a suspected assassination. 1712 – Huilliches in Chiloé rebel against Spanish encomenderos. 1763 – French and Indian War: The Treaty of Paris ends the war and France cedes Quebec to Great Britain. 1814 – Napoleonic Wars: The Battle of Champaubert ends in French victory over the Russians and the Prussians. 1840 – Queen Victoria of the United Kingdom marries Prince Albert of Saxe-Coburg-Gotha. 1846 – First Anglo-Sikh War: Battle of Sobraon: British defeat Sikhs in the final battle of the war. 1861 – Jefferson Davis is notified by telegraph that he has been chosen as provisional President of the Confederate States of America. 1862 – American Civil War: A Union naval flotilla destroys the bulk of the Confederate Mosquito Fleet in the Battle of Elizabeth City on the Pasquotank River in North Carolina. 1906 – HMS Dreadnought, the first of a revolutionary new breed of battleships, is christened. 1920 – Józef Haller de Hallenburg performs the symbolic wedding of Poland to the sea, celebrating restitution of Polish access to open sea. 1920 – About 75% of the population in Zone I votes to join Denmark in the 1920 Schleswig plebiscites. 1923 – Texas Tech University is founded as Texas Technological College in Lubbock, Texas. 1930 – The Việt Nam Quốc Dân Đảng launches the failed Yên Bái mutiny in hope of overthrowing French protectorate over Vietnam. 1933 – In round 13 of a boxing match at New York City's Madison Square Garden, Primo Carnera knocks out Ernie Schaaf. Schaaf dies four days later. 1936 – Second Italo-Abyssinian War: Italian troops launch the Battle of Amba Aradam against Ethiopian defenders. 1939 – Spanish Civil War: The Nationalists conclude their conquest of Catalonia and seal the border with France.

0 notes

Text

The First Anglo-Afghan War (1839-1842): Britain’s Great Game ends up meeting a dead end...

The region of Afghanistan has a long and varied history, one that is rugged like its topography of many mountain ranges, valleys and deserts. Its mix of barren wastes, snowy caps and forested patches of oasis. Its history has placed it at the crossroads of the geopolitical focus over the centuries. The focus of empires and of trade, often trying to assert its own path in history but so often a focal point of foreign ambition. As always to appreciate the modern we need to go back to earlier times.

Early History:

-Afghanistan is a patchwork of peoples, a testament to its status as a crossroads of empires over the ages. Primarily it sits in the eastern end of the ethnolinguistic region of Iranian peoples, a mix of ethno linguistically related but diverse groups of peoples from Persians (Farsi), Kurds, Ossetians, Baloch to Pashtun and Tajik among others. The latter two being the primary groups found in Afghanistan today, along with smaller Iranian groups like the Hazara & Baloch. Others include the Turkic Uzbek and Turkmens and a small number of Arabs.

-In ancient times Afghanistan was home to Iranian groups known as Bactrians & Sogdians who inhabited portions of the country. These peoples were incorporated into their fellow Iranians sphere of influence, the first Persian or Achaemenid Empire. This empire stretched from the Indus Valley in the East (modern Pakistan/India) to Greece and the Balkans in the West. Members of these groups served in the Persian Empire’s army but maintained their own traditions too. It is widely believed that the religion of the Persian Empire and of most Iranians in this time was Zoroastrianism, founded by Zoroaster in the region of Balkh in North Central Afghanistan. This religion would serve in some ways as an influence on the monotheistic Abrahamic religions of Judaism, Christianity & Islam later on history.

-During Alexander the Great’s march to conquer the Persian Empire, having defeated the Persians in three major battles and taken the western half of their empire, he sought to conquer the eastern half too which took him into the modern region of Afghanistan. The Macedonian armies under Alexander founded new cities here and brought forth Greek culture which began to merge with the local religion and culture. This Hellenistic culture spread as far as India as with Greek paganism, Hinduism, Buddhism and Zoroastrianism all mixing in the same cities as times. In the wake of Alexander’s death, his empire which essentially replaced the Persian Empire had no set structure of succession and quickly dissolved into portions going to his various generals. The largest expanse of which was the Seleucid Empire which spanned the whole of the Iranian plateau to India and to the Levant, this included Afghanistan. The region underwent many changes with portions being given to the Indian superpower of the day, the Mauryan Empire and later a successful uprising against the Seleucids, forming the Greco-Bactrian Kingdom which found itself at war with the Parthian Empire, a resurgent Iranian Empire which swept away the remnants of Seleucid Greek rule. These wars left Afghanistan open to nomadic invasions, namely from the nomadic branch of Iranians from the Eurasian steppe, coming in different waves. The Yuezhi and Scythians, the Scythians would later establish a kingdom that controlled portions of the region, the Indo-Scythian Kingdom as did the Yuezhi which became the Kushan Empire. Eventually this gave way to the second Persian Empire or Sassanid Empire which took over the region.

-All the while this region sat along the Silk Road spanning from the eastern reaches of the Roman Empire in the West to the Han Chinese in the East. Goods and peoples of different backgrounds travelled through the region, most just passing through but they all shared their influence, establishing Afghanistan as an important crossroads of commerce and not just conquest. Additionally, ancient sources attest to portions of Afghanistan, namely the region around the city of Herat being a major source of grain due to fertile farmlands in Central Asia as well as supplying vineyards of grapes for winemaking in the Persian world.

-In terms of religion, Afghanistan reflected the many changes of its many ruling peoples religions remaining a hub of Buddhism, Hinduism and Zoroastrianism along with lingering elements of Greek culture. This would change with the eventual downfall of the Sassanids in the 7th Century AD to the Islamic Caliphates and their gradual expansion over the Iranian plateau. Overtime Islam began to gradually take hold as the religion over the area but it was still set side by side with numerous other faiths and lived in relative tolerance to the other faiths. Eventually the Ghaznavid and Ghurid & Khwarazmian dynasties ruled over the area, a mix of Iranian and Turkic peoples who gradually made Islam the unifying religion of the region by the Middle Ages.

-The Mongols would invade and devastate the region in the 13th century. The devastation was so complete that the many settled cities were ruined, forcing the peoples of Afghanistan back into rural agrarian societies, something which has not been fully removed from the majority of Afghan society today. Overtime the peoples of Afghanistan, a region long noted for its literary, especially Islamic poetic contributions and had been a hotbed crossroads of cultural interfacing, was now reverted to an mostly tribal agrarian society once more. With some centers of learning gone forever Its peoples divided along ethnolinguistic grounds and into clans from there.

-There was somewhat a renaissance in the ages with the Turco-Mongol ruler, Timur and his empire ruled with new additions to architecture and culture contributed to the region but this was short lived. Meanwhile, a descendant of Timur named Babur would base himself in Afghanistan before launching an invasion of India and upon overtaking the Sultanate of Delhi, became the founder and ruler of the new Mughal Empire, the Islamic superpower that was to overrun much of India and dominate the subcontinent and beyond in the coming two centuries.

-Meanwhile, Afghanistan once more found itself on the fringe of an Iranian power, half the country at max was under the control of the Safavid Empire, a Kurdish dynasty that took power in Persia and expanded to reclaim historical “Persian” lands. Indeed the Persian (Farsi) language was regarded as the lingua franca of the region for centuries and was the language of the learned and most educated in the Islamic world as a whole, whereas Arabic was for mostly religious celebration. Persian was the language of government and the arts.

-Safavid rule was tenuous at best and their primary focus was facing the Turkish Ottomans to the west, leaving much of Afghanistan to de-facto local rule. Here the tribal societies that have dominated Afghanistan to the modern era, in part a result of the resumption of rural life after the Mongol destruction of the major cities held sway, with tribal leaders functioning as more or less warlords among the Pashtun and Tajik peoples and their various clans among others ruled over certain sections of the country. Only Islam united them in their differences. Much time was spent raiding and fighting each other, along with the few travelers who ventured into this increasingly isolated and remote portion of the world.

-The Hotak dynasty of Pashtuns had a hand in the downfall of the Safavids which was increasingly corrupted and weakened by intrigue at the royal court. In the wake of this, a Turco-Persianate ruler named Nader Shah took the reins in Persia and put down the Hotaks before setting up his own short lived Persian Empire, known as the Afsharid dynasty which pillaged the Mughals in India and defeated the Ottomans several times before Nader Shah was killed and his successors failed to maintain control. In Afghanistan, another Pashtun dynasty, the Durrani took power in the middle 18th century.

-The Durrani would for the first time in the modern age have a local Afghan power base that expanded beyond the borders of Afghanistan with any longer lasting impact. These mostly Pashtun peoples supported by some Persians invaded and controlled portions of India, defeating the Hindu superpower, the Maratha Empire at the peak of their powers at the Third Battle of Panipat in 1761. However the Durrani dynasty and its Emirate of Afghanistan, was weakened through ongoing external and internal pressures, military defeats from the Qajar dynasty in Persia and the new Sikh Empire in the Indian Punjab put closed in their borders. Eventually, internal conflict led to the fall of the Durrani dynasty with one its Emirs (leader), Shuja Shah going into exile in India hoping to return to rule. By 1823 the country had fractured into many smaller entities with civil war taking place until by 1837 Dost Mohammed Khan, founder of the Barakzai dynasty took power as Emir and reunited the country...

The Great Game:

-The exile of Shuja Shah and rise of the Barakzai dynasty in Afghanistan after much civil war by the end of the 1830′s was the state into which Afghanistan again entered wider geopolitics. Namely amidst the geopolitical struggle between the British and Russian Empires. Called the Great Game by the British as Tournament of Shadows by the Russians, this rivalry for geopolitical and economic influence was a likened to a game of chess whereby each power vied for influence, mostly through proxies, a precursor to the Cold War of the 20th Century between the US and USSR. Afghanistan it was hoped by both Empires would be one of those proxies.

-The British since the 16th and 17th centuries had pushed to become a naval power as well and felt that international commerce was the way to expand their economic and political power. Along with the Spanish, Portuguese, French and Dutch they all took an interest in naval power and setting up colonies in other parts of the world. In Asia, the Indian subcontinent became their primary focus. It was rich in resources such as tradable goods like cotton, silks, spices, jewels, salt, opium, various minerals and other commodities. It was also a vital link in the idea of a global empire in protecting commerce links on the way to Indonesia and China. Denying their main rival, France, influence in India was of high importance and by the mid 18th century, they became the unrivalled European power defeating the French at the Battle of Plassey during the Seven Years War. India was not united in any meaningful fashion at the time locally with various empires, kingdoms and principalities fighting locally over this vast area. They were divided by various ethnicities, religions and the usual drives of personal power and wealth. Due to this division, the Europeans who first established small trading factories gradually could expand their power to the interior of India and through mutual alliances of convenience between them and their local Indian trading partners they could compete with other Europeans. For some Indians, the European powers were initially more to their benefit, their presence was small but their weapons and military advantages were far superior giving them a strategic advantage over their opponents. In time, this power dynamic changed as the Indians had to continually grant the Europeans more power, namely the British who routinely defeated the Indians and began ceding more territory to them. Also the British’s vast wealth could now employ Indians against other Indian powers. Especially after France’s defeat at Plassey, no other Europeans seriously threatened the British interests. Britain’s East India Company, a joint-stock venture given great autonomy in the name of the British Crown had its own military, its own military officers school and total monopolies over half the world’s trade at one point.

-The British East India Company’ army had British officers, mostly Indian rank and file soldiers called sepoys and occasional regular British army regiments to complement it in its venture to conquer the whole of India by any means necessary. The East India Company also known as the Company had since the 17th century established a number of trading posts, most importantly Calcutta which was the capital of Bengal in the eastern portion of the country. This was decisively established after defeating the French and remnants of the crumbling Mughal Empire which they supported and which had declined since the 18th century due to the rising power of the Maratha Empire, India’s last great Hindu superpower before the British era.

-Britain focused their efforts of conquest on south India, first defeating after much initial difficulty the Kingdom of Mysore, run by Tipu Sultan. Later, battling the Maratha Empire which had piqued by the mid 18th century. Following their defeat by the Afghan Durrani Empire at the Third Battle of Panipat, the Maratha started a gradual decentralization that led to civil war, the Company got involved trying to place their preferred candidates in power in the Maratha hierarchy. The first war saw a British defeat but by the early 19th century, the British with Arthur Wellesley, the future Duke of Wellington, fought a second war, defeating the Marathas at Assaye from which they gained territory. They finished off the Marathas in 1818 and had by then essentially absorbed the whole of India with exception of the Punjab where the Sikh Empire had arisen under Maharaja Ranjit Singh at the end of the 18th century and grew in power in the first decades of the 19th century. The Sikhs had thrown off the last remnants of the Mughals in their realm and then pushed out the Afghans on their borders too.

-The Sikh Empire like many Indian powers used foreign mercenaries and officers from Europe & America to join their ranks, supply them with European and American style military training doctrine and supply them with the latest in military technology which far surpassed anything made in India at the time. The Sikh army was quite strong and had French officers providing most of the training, the Company’s default position was to make an alliance with them. The Sikh’s had troubles with Afghanistan, namely over the city of Peshawar and the Khyber Pass.

-The Russians for their part had expanded from Russia over the whole of Siberia towards the Pacific, this process had begun in the late 1500’s and was completed by the end of the 17th century. Leading to Russian exploration and colonization in Alaska and elsewhere in the Pacific during the 18th century.

-Russian expansion into Central Asia was in part a result of their off and on conflicts with the Ottomans and Persians in the past. By the second decade of the 19th century with the threat of Napoleonic France gone, their attention turned to maintaining a balance of power in Europe and a free rein in Central Asia. The threat to their influence as they saw it was Britain, which Russian tsars, namely Nicholas I, viewed with suspicion as far too “liberal” for their belief in absolute monarchy and conservative values. The British in turn were suspicious of Russian threats to their geopolitical spheres, namely gaining too much power at the expense of the Ottoman Empire or more directly to British India which was after the American Revolution to become the crown jewel in their global empire.

-The Russians gradually defeated the various Islamic emirates in Central Asia, taking over modern Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan. The process was drawn out over several decades but through military conquest by the late 19th century would be achieved. It was as this Russian encroachment neared Afghanistan, that alarm amongst the British in India began to be raised…

The British Misinterpret Everything:

-Britain’s government and the East India Company misinterpreted the Russian view of events. It is true Russia sought to expand its influence but the British interpreted the expansion into Central Asia as meaning only one thing, eventual invasion and conquest of British India. Only Tsar Paul I in 1800 seriously pressed for an invasion of British India but he was assassinated and the plans for invasion never thought of as a practical reality by most in Russia’s military were cancelled. The Russians did want increased political influence in the area but even the most conservative of Russian tsars always believed a reproach with Britain could be obtained.

-The British also saw civil war in Afghanistan as well as the strength of the Sikh Empire as threats to their border and greater sphere of influence in India. The conflict between the Sikhs and Afghans meant they had to choose sides, they couldn’t be an alliance with both. Precisely, because of this conflict and the greater specter of Russian influence did Britain find itself on a course for war.

-In Afghanistan, the British and Russians had spies and intelligence agents acting as emissaries. The British had Scotsman Alexander Burnes, who joined the British East India Company. Burnes was stationed in Kabul and in turn his presence spurred the Russians to counter with their own envoy, the Polish-Lithuanian born Jan Prosper Witkiewicz. Both British and Russian envoys hoped to make an alliance with Afghanistan’s emir, Dost Mohammad Khan against the other. The emir for his part sought to regain Peshawar, recently lost to the Sikhs. This, however put the British in an awkward position, Company controlled India bordered the Sikh Empire and both sides had a mutual if tense respect for one another. The Sikh Empire was the last major independent kingdom of India outside of British rule and while Britain sought to eventually neutralize it, now was not the time. Furthermore, the Sikhs had a large standing army, with European doctrine, modern weapons and European officers who could pose a threat to British India, a threat they saw as greater than Afghanistan. Afghanistan had no formal army, only tribal men with tribal loyalties but nominally served their overlord the emir in times of national defense.

-Dost Mohammed Khan wasn’t enthused about the Russians to begin with but he believed the entertaining of an alliance might force the British to offer their alliance. Instead, given the British calculations of realizing they couldn’t support the Afghans over the more powerful Sikhs but also couldn’t abide the possibility of s Russian allied Afghanistan, moved closer to a casus belli for war.

-Burnes was apparently distraught at the arrival of the Russian envoy in 1836-1837, he wrote panicked reports. The Russians in turn reported on British maneuvers in Kabul. The British governor-general of India, Lord Auckland sent what amounted to a cease and desist letter to Dost Mohammed Khan. The letter was very demanding of Khan, ordering him to not negotiate with the Russians or even receive them as envoys. Khan was angered by this but wanted to avoid war. He had his own advisor, an American named Josiah Harlan talk to Burnes. Burnes argued he could only report on matters not make policy directly himself, Harlan saw this as merely stalling on his part and on his advice Khan expelled the British mission.

-Lord Auckland was now determined to force Afghanistan to submit to British demands. Furthemore, Russia and Afghanistan couldn’t come to a deal and their mission too broke down. Meanwhile, Afghanistan’s major western city, Herat was besieged by Qajar Persia with Russian material support. Fearful the Russians might use this as a pretext to invade Afghanistan proper, Auckland would in turn use it as a pretext to restore “order” in Afghanistan.

-Auckland reached a reproach with Ranjit Singh, the Sikh Maharaja. His goal was to fend off the Persians and their Russian support. He would also depose Dost Mohammed Khan as emir, seeing him as too unfriendly to British interests by his earlier negotiations with the Russians, as well his conflict with the Sikhs, who the British treated as a nominal ally at the time. His plan included placing the former Durrani emir, Shuja Shah on the throne once more. Shah had lived in exile in British india since 1818 and had been deposed in 1809. In the three decades since he last reigned, he was hardly remembered by anyone, aside from those who remembered his cruelty that had led to his deposition in the first place. Shah had been given a Company pension and comfortable living in exile, considered a useful pawn in British geopolitics, he in turn was willing to ally with anyone who would support his restoration to the throne. Auckland was led to believe that Shah was actually popular and that the instability in Afghanistan meant Khan was unpopular himself, the inverse turned out to be the case...

The First-Anglo-Afghan War:

-By October 1838, Auckland sent the so called Simla Declaration which resolved the British and the Sikhs to march in Afghanistan and restore Shuja Shah to the throne on the grounds that Dost Mohammed Khan was unpopular, had lead to instability within the country, was a threat to the Sikhs and British by extension and given rise to the prospect of foreign (Russian) interference.

-In Punjab, Lord Auckland and Ranjit Singh held a grand parade of the so-called Grand Army of the Indus which would march in Afghanistan jointly to bring “order”. Two things happened in the interim. The Persian siege of Herat was called off and the Russian tsar had recalled his envoy altogether. The British pretexts for war ended before war began. Auckland and others heading the Company’s policy in India however were deadset to commit to a military operation, believing Afghanistan essentially needed to be put in its place, meaning it needed a British backed ruler who would amount to a puppet and could put British interests in the region first.

-December 1838 saw the British East India Company’s 21,000 strong army set out for Afghanistan. Composed of British and Indian troops (mostly rank and file Indians and British officers) along with nearly 40,000 Indian camp followers, Indian servants, families and even prostitutes following too. Ranjit Singh in the end backed out of the plan, not sending any troops to aid in Afghanistan.

-The British trek took months to cross the snowy Hindu Kush mountains. Finally they reached the area near Kandahar in April 1839. From there they waited two months until better conditions in the summer to march to Kabul. The British found themselves having to besiege the fortress-city of Ghazni in July. Eventually upon destroying a weakened gate, they breached the city and after much fighting captured the city.

-Khan upon hearing of Ghazni’s fall, offered a surrender to the British, he was replied with removal of his position on the throne to a life of exile in India, this was unacceptable, so the march to Kabul continued, though Ghazni remained occupied.

-A battle took place outside of Kabul which forced Dost Mohammed Khan to flee the city, the British entered and Shuja Shah was placed on the throne. The war was seemingly at end, the main objective achieved, Khan’s removal and Shah placed on the throne. Most of the British Indian force returned to India, leaving some 8,000 to occupy Afghanistan in various places from Kandahar to Kabul.

-The initial invasion was successful but the occupation and continued support of Shuja Shah was costly in terms of public relations for the British. Shah resumed his cruelty, he punished and executed those who he considered traitors from decades before. By his own admission, his people were dogs in need of “obedience” and corrective punishment. He raised taxes which hurt the already impoverished economy. This hurt his limited popularity along with his essentially martial rule, upheld by the British. Now, a guerilla war phase was being instituted by various Afghan groups, some loyal to Khan and some just offended by the presence of foreign invaders.

-The British for their part did not help matters. Many officers imported their families from India into Kabul, where they took residence in a cooler mountain valley climate, they created gardens and set up English country gentrified life in the Afghan capital. Some English customs weren’t especially troublesome to the Afghans, tea drinking socials, cricket and polo, even ice skating on frozen ponds in the winter which actually amazed the Afghans having never before seen such a thing.

-However, the more the British lingered, the sense they'd never leave crept in, their presence in the daily markets brought raised prices which coupled with higher taxes meant they were linked with such economic hardship. The British also drank alcohol and had wine cellars fully stocked, in a devout Muslim country this was offensive given Islamic prohibitions on alcohol. However, most trying for the Afghan populace was the sexual relations between the occupiers and Afghan women. British men soon found themselves acquiring the services of willing Afghan women for prostitution. Afghanistan was quite poor to begin with and coupled with hardships brought on by the invasion a number of Afghan women, married or unmarried found themselves becoming prostitutes to the British. Afghan women realized even the lowest paid British soldier was more wealthy than Afghan men, so their turns to prostitution were not unsurprising. Others willingly entered into romantic relationships with the British and indeed some British officers did marry Afghan women, including daughters of tribal leaders. This development offended the Afghan men, particularly the Pashtun who had a sense of society that revolved around honor to manhood, any slight real or imagined could be responded to with justified violence in their code of honor. The Pashtun men could enact honor killings on women who fraternized with the British, on the grounds that these women brought shame to the men in their family for engaging in immoral behavior and for sleeping with infidel Christians.

-The guerilla war that developed in reaction to the British also spurred their sense of prolonging their stay. Shuja Shah knew more British was the only way to ensure his continued reign. Isolated British outposts or patrols could be attacked in ambush due to fighters whose entire fighting style relied less on technical skill or discipline beyond waging ambushes and raids. Most Afghan warriors would have been armed with little more than an old matchlock musket or possibly a dagger or sword.

-The British nevertheless were negotiating with Shuja Shah to develop a standing army and do away with the tribal levy system. He argued there was not enough infrastructure or more succinctly, funding to maintain a standing army. So the British occupation dragged on.

-Dost Mohammed Khan was eventually taken prisoner and exiled to India. However, his sons continued to wage the war on their dynasty’s behalf.

- By 1841, George Elphinstone was in charge of the British forces in Kabul, most of his time was spent bed ridden with gout and other ailments.

-Early November, saw in motion a planned uprising. For months through Shuja, tribal chieftains had their loyalty earned by bribes of money. The British used this as a way to pacify the resistance with some success but it was a tenuous development. The spark for the uprising in Kabul came from British agent, Alexander Burnes. Burnes had been particularly well known for his sexual relations and womanizing of Afghan women and was viewed as largely a focal point of the resentment Afghans had towards the British. The final straw came when a slave girl from Kashmir who belonged to a Pashtun chieftain escaped to Burnes home. At first the chieftain sent retainers to retrieve the girl, only to find Burnes in the act of sleeping with her himself, Burnes own guards then beat the retainers and sent them on their way. The chieftain, having his code of honor offended along with other chieftains, proclaimed jihad. The next morning a large riot broke out at Burnes residence in Old Kabul, away from the British camp which had moved to the outside of town. Burnes, his brother and others were hacked to death by the angry mob, their beheaded skulls placed on pikes for display. Shuja Shah sent a single British regiment to put down the events, it suffered casualties and was forced to return. Shuja realized the people were rebelling against him and the British and he was effectively overthrown.

-Elphinstone was gripped with indecision on how to deal with the matter, he wrote to the Company Civil Administrator, William Macnaughten. Macnaughten tried to negotiate with Akbar Khan, son of Dost Mohammed, with an eye towards making him vizier, in exchange for extending the British stay. Macnaughten also negotiated with other tribal leaders to assassinate Akbar Khan. The news of these two faced dealings led to Macnaughten being captured and killed by Khan’s men, his body dragged through the streets of Kabul.

-Elphinstone realized it was time to withdraw, the British presence no longer tenable. The Afghans had not attacked the encampment directly due to the concentrated British strength but these appeared to be only a matter of time. He made the decision to withdraw the garrison, 4,500 strong with 12,000 camp followers including family and mostly Indian servants and some Afghan women who preferred life with their British lovers as opposed to facing the wrath of their angered families who would kill them for shaming them.

-January 1842 saw Elphinstone’s withdrawal in a massive column through snowy passes. The retreat dragged out for weeks with little food, bad weather and repeated attacks from Pashtun guerillas who attacked and killed as many as they could. Repeatedly, Elphinstone met with Akbar Khan to call off the attacks, Khan allowed the English women and children to return to Kabul to be ransomed later, but the Indian camp followers were not spared, they were forced to freeze to death in the snowy passes. Meanwhile as Elphinstone and the army marched on, the attacks continued with Khan playing Elphinstone for a fool. Eventually, he treated Elphinstone to a good meal before taking him prisoner, Elphinstone would die as a hostage some months later. The 44th Foot, the only all British regiment made a famous last stand fending off many Afghan charges before being overrun. The British column was mostly starved, frozen or hacked to death in the passes, most of the victims being Indian sepoys or their families and camp followers (servants) of the British officers. Some British women and children remained in Afghan captivity for a time, with some being ransomed and released, most being well treated. Some women were forced to marry their captors and others as children were adopted into Afghan families, some living into the early 20th century in Afghanistan. Only one British doctor and some scattered sepoys survived the ordeal at all. Much of this episode was detailed by Lady Florentia Sale in a diary, later published to great acclaim. She would spend nine months in captivity before her and her daughter were rescued by the British.

-The Afghans stormed the other British garrisons but all these attacks were repelled, in turn British reinforcements were arriving from India. These reinforcements subsequently beat Akbar Khan in a pitched battle. Plans were underway for a retaking of Kabul with a new larger force but Lord Auckland suffered a stroke and was replaced by Lord Ellenborough as Governor-General of India. Plus, elections in Britain’s parliament brought a new government with orders to change policy, withdraw from Afghanistan, which found itself in a military stalemate. A last battle took place in which Akbar Khan who was routinely defeated in pitched battles was beaten again with huge casualties at Kabul. However, the measure was merely punitive for the deaths of Elphinstone’s column. The Company at government orders withdrew all British troops from Afghanistan, having inflicted numerous deaths on the Afghan side and destroyed more forts of theirs but politically been unable to change the situation.

-Dost Mohammaed Khan was allowed to return where he co-ruled with his son Akbar who eventually died in 1845, possibly poisoned on orders from his father, who is rumored to have misgivings about his ambition. Dost Mohhamed Khan’s primary goal was to restore Peshawar from the Sikhs all along, during the Anglo-Sikh Wars that followed in the decade ((1845-1846 & 1848-1849), he was nominally neutral albeit he somewhat supported his old rivals the Sikhs with an Afghan mercenary force, still hoping to negotiate Peshawar. These wars resulted in British victory over the Sikhs, the last of Indian independent kingdoms fell and India was more or less completely in Company hands, the Afghan border nor directly bordered British India in the Punjab. The British never returned Peshawar despite their own promises to do so, but Dost having faced his own temporary overthrow and captivity realized, the British were far too powerful to resist in the long run and so he maintained quiet on his part, staying neutral during the Indian Mutiny of 1857, ruling until his death in 1863.

-The British for their part were defeated in the first Anglo-Afghan War, though their military generally held the upper hand in pitched battles and their initial invasion for all its hubris and motivations was successful. It was the occupation that proved too much of an expense than originally endeavored. British arrogance and ignorance of local custom also worsened reception of their plans. In the end, it was British paranoia, belief in imperial prestige and jingoism that had led to a war that while a limited military success was a political failure, having achieved none of their goals, which seemed to shift as the situation shifted. It was a confused war, brought on by people on all sides misreading the events surrounding them and made worse by their stubborn commitment to short-sighted policy goals and ego. Britain would avoid venturing into Afghanistan for nearly forty years when similar disputes over diplomacy led to a second war...

#19th century#military history#afghanistan#the great game#british imperialism#british east india company#india#islam#pashtun#tajik#persian#russian empire#guerilla warfare#kabul

7 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

First Anglo-Sikh War ਦੀ ਪਹਿਲੀ ਜੰਗ ਹਾਰਨ ਦੇ ਕਾਰਨ || The History Series || ...

0 notes