#that is- Allin Kawsay

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Some of My Notes on Sahumos, or Smoking [a person, object or place].

The Medicine of Sahumos is supported by the Medicine of the Jaguar, the Full Moon and Earth, in the sacred herbs used and their effects in our bodies. It is supported by the Medicine of the Snake, the Waning Moon and Water, in the libations offered and the blood we carry. It is supported by the Medicine of the Qori Kinti, the New Moon and Air, in the cry of our songs and the prayers whispered. But more importantly, it is the Medicine of the Kuntur, the Waxing Moon and Fire, of our Energy and our Spirits. The Fire is the Vulture eating at our flesh, cleansing us of impurities, to be reborn anew from it's smoke.

"The Medicine of Sahumos will tear you apart. It will show you the beautiful parts of yourself, and the painful. It will shed light on parts of yourself you'd rather not see, but you must look and eat at them with your fire. It can't be just lighting an incense stick. All elements must be present. The Mesa must be laid out and your Yanapaq called. There's offerings and permissions. There's prayer and song. (...) And we must be able to identify what is sámi and what is hucha in ourselves first if we want to help others with our smokes. We must recognize and make space for our own emotional and spiritual state first, respect our own processes. (...) The growth is well worth the pain, and it is our responsibility, in order for us to walk this path with Integrity."—words from an experienced Sahumadora Andina, Andean Smoke Medicine Carrier, and whom I'm learning this Art from. Translated by me.

#sahumadora#Vultur Bikephalos#here Integrity means not only our own good health but also#the three principles of andean medicine I wrote about a while back#allin yachay allin munay and allin ruray#to walk the qhapaq ñam -the path of the Ancestors- with Integrity#that is- Allin Kawsay#hucha mikhuy is the act of eating away at that hucha to transform it back into sámi in this case using the fire and smoke#my notes#Regina Mundi

7 notes

·

View notes

Note

algito para las chicas ecuatorianas? porfaaa 🙏

Una mujer Otavaleña 🌼🏵🌼

La modela: hayetcb

Allin Kawsay 😚 ñañakuna

#Otavaleña#ecuatoriana#native south american#andina#mujer andina#ndn tumblr#Ecuador native#indigenas#otavalo#imbabura#ñañakuna#native to Ecuador#andean#andean pride#indigena

33 notes

·

View notes

Text

Las dos izquierdas latinoamericanas

Por Alexis Cortés

Fuentes: Jacobin [Foto vía CELAG]

La izquierda latinoamericana debe dar respuesta a la emergencia climática tanto como a la necesidad de estructurar un proyecto de desarrollo distributivo y de integración.

En un artículo publicado en 2006 que llegó a ser bastante influyente, Jorge Castañeda buscó trazar una línea divisoria entre los distintos gobiernos de cuño progresista de la región que por esa época protagonizaban el «ciclo progresista» u «ola rosa». Castañeda distinguía entre dos izquierdas: una correcta, de carácter moderno, reformista, global y de mente abierta, y otra incorrecta, de tradición populista, radical, nacionalista, de mente cerrada y de acciones estridentes.

De aquel momento al presente, esa distinción parece estar medianamente superada, no solo por la capacidad que tuvieron las candidaturas de derecha de arrebatarle primeras magistraturas a ambos tipos de izquierda —afectando una de las principales características del ciclo: la capacidad de reelegirse y mantenerse en el poder— sino, sobre todo, por el fracaso de una de las principales referencias del ideal de «izquierda correcta» en el análisis de Castañeda. La Concertación de Partidos por la Democracia de Chile entró en una crisis terminal que acabó por entregarle dos veces el gobierno al derechista Sebastián Piñera, a pesar de sus intentos por incorporar elementos más propios de lo que —para Castañeda— sería la «incorrección política», en un esfuerzo por responder al creciente malestar de la población con las consecuencias sociales y económicas de un neoliberalismo avanzado y extremo.

Hoy resultaría difícil sostener que un proyecto político que no asuma un horizonte claro de superación del neoliberalismo pueda ser considerado de izquierda. La Revuelta Popular del 18 de octubre de 2019 en Chile pareció ponerle una pala de sal al modelo que se consideró ejemplar para la región: la vía chilena al neoliberalismo. A pesar de la promesa de los movilizados de que Chile sería «la cuna del neoliberalismo, pero también su tumba», la superación de este paradigma, aunque unifica diferentes vertientes de la izquierda latinoamericana, aún presenta nudos críticos que dificultan su traducción a un modelo alternativo. La izquierda en la región enfrenta una nueva tensión que la divide.

¿Vivir bien?

En 2011, una serie de artículos publicados por Pablo Stefanoni que retrataban lo que irónicamente denominó como el embate entre «pachamámicos» versus lo que sus detractores tacharon de «modérnicos», dejaron en evidencia una de las principales contradicciones del proceso boliviano. A saber, la pugna en el campo de la izquierda local (pero extensible a la región) de dos tendencias: una vertiente neodesarrollista y extractivista, asociada al gobierno de Evo Morales, y otra identitario-ambientalista, asociada al movimiento indígena y a buena parte de la intelectualidad que terminó rompiendo con el MAS.

Para Stefanoni, el «pachamamismo», munido de una pose de autenticidad ancestral, más parecería una filosofía próxima a un «indigenismo new age» que, entre otras cosas, elude los problemas políticos del ejercicio del poder y del Estado, así como las discusiones en torno a un nuevo modelo de desarrollo que logre superar el extractivismo y la reprimarización. En sus palabras, en lugar de discutir cómo combinar las expectativas de desarrollo con un eco-ambientalismo inteligente, el discurso pachamámico nos ofrece una catarata de palabras en aymara, pronunciadas con tono enigmático, y una cándida lectura de la crisis del capitalismo y de la civilización occidental.

Los momentos constituyentes que acompañaron la instalación de los gobiernos de Bolivia y Ecuador se identifican con un proceso de coincidencia estratégica entre estas posiciones que hoy se han vuelto cada vez más antagónicas. Las cartas magnas fueron extremamente innovadoras al incluir, entre otras cosas, la perspectiva andina del «buen vivir» (suma qamaña en aymara y allin kawsay o sumak kawsay en quechua), o sea, la promoción de un bienestar holístico cuya base es la armonía con la naturaleza y con la comunidad.

Sin embargo, tal como lo resume Andreu Viola, por más positivo que sea el cambio de actitud hacia valores y estilos de vida no occidentales que la reivindicación de este término implica, el mismo no deja de ser una tradición que no ha logrado precisarse de un modo más concreto, quedando ambiguamente plasmada en las Constituciones. Más aún: el «buen vivir» no ha conseguido reflejarse en los planes económicos de esos gobiernos progresistas, que mantuvieron las visiones economicistas y tecnocráticas del desarrollo.

Así las cosas, el problema radica, por un lado, en la idealización del mundo rural andino y, por otro, en la discordancia de estos ideales con las políticas macroeconómicas impulsadas por esos gobiernos.

La izquierda del «buen vivir» ha contribuido a poner de relieve en las agendas de la región la urgente necesidad de la protección del medio ambiente, reivindicando las prácticas ancestrales de los pueblos indígenas como un modelo alternativo a las lógicas depredadoras del capitalismo neoliberal. Según el antropólogo colombiano Arturo Escobar, es un tipo de pensamiento posdesarrollista que se construye «desde abajo, por la izquierda y con la tierra». Sin duda, este movimiento intelectual ha entregado poderosas herramientas conceptuales para la reemergencia de grupos indígenas y de comunidades ambientalistas que resisten ante la expansión extractivista latinoamericana. Pero ha descuidado los debates sobre un modo de producción alternativo que genere condiciones de bienestar material para la población.

Si bien, como ha procurado mostrar Álvaro García Linera, en el comunitarismo andino no solo hay expresiones precapitalistas sino también anticapitalistas —que pueden ser la base de una reorganización económica—, estas experiencias no son suficientes para responder a la pregunta de con qué reemplazar el actual modelo de (sub)desarrollo en la región.

Desarrollismo sin desarrollo

Lo paradojal es que la perspectiva desarrollista, que pone en el centro de sus preocupaciones y prácticas la cuestión económica, tampoco parece tener una respuesta consistente a este desafío. Tal como lo ha retratado Maristella Svampa en sus estudios críticos sobre el periodo político reciente en América Latina, la ola rosa, aunque asociada a una expansión de la frontera de derechos sociales, también estuvo ligada a una ampliación de las fronteras del capital, particularmente en territorios indígenas.

El ciclo posneoliberal se sostuvo gracias al auge de los precios de los commodities, reemplazando el consenso de Whashington por uno que mantiene un crecimiento basado en la exportación de materias primas, proceso que la autora denomina «Consenso de los Commodities», es decir el ingreso a un nuevo orden, a la vez económico y político-ideológico, sostenido por el boom de los precios internacionales de las materias primas y los bienes de consumo cada vez más demandados por los países centrales y las potencias emergentes, lo cual genera indudables ventajas comparativas visibles en el crecimiento económico y el aumento de las reservas monetarias, al tiempo que produce nuevas asimetrías y profundas desigualdades en las sociedades latinoamericanas.

Este modelo extractivo-exportador, afirmado principalmente en megaproyectos invasivos, ha tenido como resultado una fuerte ambientalización de las luchas sociales y ha consolidado una nueva racionalidad ambiental posdesarrollista, aumentando la brecha entre estas dos izquierdas. Por otra parte, aunque el ciclo progresista habría estimulado un «regionalismo latinoamericano desafiante», según Svampa, también ha inaugurado nuevas formas de dependencia, a partir del intercambio asimétrico con China, nuestro principal socio comercial en la región, en tanto comprador de materias primas.

Aunque la ola rosa se afirmó desde un horizonte posneoliberal, parece no haber alterado uno de los pilares de las lógicas neoliberales: el aprovechamiento de las ventajas comparativas de los países emergentes, que no es otra cosa sino la renuncia a una opción industrial en favor de la explotación de materias primas.

En efecto, todo modelo de desarrollo supone un modo de acumulación, regulación y distribución. En el caso del neoliberalismo, la acumulación se basa en las ventajas comparativas y en una fuerte financierización económica; al mismo tiempo promueve una fuerte (des)regulación económica, basada en la retracción estatal; y finalmente, distribuye mediante la creencia en el derrame económico y en la intervención focalizada de la pobreza extrema. En América Latina, el extractivismo y la reprimarización parecen ser una constante tanto en gobiernos neoliberales como en aquellos que se supone aspiran a superarlo; aunque han promovido un resurgimiento de las capacidades estatales para intervenir y regular la economía, sobre todo a través de la nacionalización de los recursos estratégicos. Finalmente, los gobiernos progresistas han estado lejos de implementar políticas sociales universales que consoliden derechos; han optado por lógicas focalizadas de transferencia de renta, en la medida que los altos precios de los commodities lo han permitido. Con todos los avances y contradicciones político-sociales de los gobiernos progresistas, estos no innovaron en cómo dejar atrás el neoliberalismo.

Aunque se le acusa a estos gobiernos de neodesarrollistas —en alusión, sobre todo, al pensamiento cepalino del siglo XX—, del balance de este ciclo no podemos desprender nada equivalente a un proyecto como el modelo de Industrialización por Sustitución de Importaciones, tal como ha mostrado, entre otros, el sociólogo José Maurício Domingues. Sin duda, la industrialización sigue siendo un término clave para el futuro. La cuestión pasa por cómo lidiamos con el hecho de que se puede incrementar la presencia industrial en el continente sin modificar la posición subordinada de nuestras economías en la división internacional de trabajo. El cruce de fronteras de las maquiladoras estadounidenses a México en busca de mejores condiciones de extracción de plusvalía, industrializa, pero al mismo tiempo subordina.

Tal como señalaba la economista Alice Amsden, el desafío de los países periféricos es pasar de una estrategia «compradora» de tecnología, como en el caso de las maquiladoras, a una sustentada en la «producción» de tecnología. Para eso es indispensable que el Estado asuma un rol de ser «conducto y conductor» de ese desarrollo, pues otros actores económicos difícilmente romperán con la comodidad de un rentismo poco inclinado a la inversión estratégica y acostumbrada a amplios márgenes de ganancia, basados en la renta de la tierra y en la superexplotación del trabajo —precario— latinoamericano. Al mismo tiempo, ese desarrollo debe considerar los límites plantarios y la necesidad de un nuevo pacto socioecológico que contribuya a revertir la crítica situación climática y ambiental que han hecho más patente la advertencia de Jameson de que «es más fácil pensar el fin del mundo que el fin del capitalismo».

Construir futuro

La izquierda latinoamericana difícilmente será alternativa de futuro si no es capaz de responder tanto a la emergencia climática como a la necesidad de estructurar un proyecto de desarrollo que permita distribuir riqueza e integrar a los ciudadanos excluidos de la región al consumo y a estándares materialmente más elevados de vida. ¿Pero, es posible? ¿Acaso la superación de la pobreza y el aumento de la capacidad de consumo no van de la mano con un incremento de los factores que empeoran la crisis climática?

La respuesta no es fácil. Pero el actual estado de cosas nos obliga a pensar ordenamientos económicos más racionales para aminorar nuestro impacto en el medioambiente y para reducir la desigualdad económica que campea en la región. El capitalismo neoliberal se caracteriza por destruir las principales fuentes de producción de la riqueza: la naturaleza y el trabajo. La izquierda latinoamericana tiene la misión de superar su actual contradicción y contribuir a hacer más fácil pensar el fin de ese capitalismo que nos tiene al borde del fin del mundo.

[*] El autor agradece al Proyecto FONDECYT 1200841, marco en el cual se ha desarrollado esta reflexión.

Fuente: https://jacobinlat.com/2021/10/28/las-dos-izquierdas-latinoamericanas/

0 notes

Text

Indigenous food sovereignty in the Andes: Locals discuss agro-ecology and reciprocity in the Quechua cosmovision

Excerpts:

In the Andean world, Allin Kawsay reflects the core conceptions of Andean cosmovision such as the concept of interconnectedness with the cosmos, human and non-human world leading to a stage of equilibrium with nature (Huanacuni, 2010; Gudynas, 2014; Lajo, 2005; Jaramillo, 2010).

In this study, when research participants across the four Quechua communities when prompted with the question about the role of Allin Kawsay in food practices, unanimous answers were provided by all. As one study participant stated:

“Allin Kawsay is an ancestral principle and this principle has been practiced since many centuries ago. It is an ideology of sustainable living because if it was not for Allin Kawsay then there would have been no systems of governance and law in our community. For example, we have the ayllu (community), and ayni (reciprocity) principles that enable us to work well together’’.

Another research participant stated: “All our actions and labour are connected with our rituals and nurturing attitude towards Pachamama. In my house, we all know that all things on earth are living spirits and deserve respect. I help my neighbour with minka and yananti when a widow needs help with her chacra. All those actions reflect my Andean cultural identity, my cosmovisions, and that leads me to Allin Kawsay”

The narrative above about Allin Kawsay is supported by Peruvian Indigenous scholar Javier Lajo, who is one of the very few Peruvian scholars who has written about Allin Kawsay and who supports the narratives above. Regarding Allin Kawsay, Lajo explains:

It is a philosophy for the sustainable use of the natural resources available on Pachamama, and managed accordingly to Andean principles of reciprocity, duality, and solidarity for the overall state of equilibrium with Pachamama, human and all living beings. (Lajo, 2011; authors’ translation).

Further, empirical analysis brought to light a range of features among these, four that are particularly relevant to food security (see Figure 4): Ayni; reciprocity Ayllu: collectiveness Yanantin and Masintin: equilibrium Chanincha: solidarity

(...) In effect, this study reveals that Quechua communities adopt a series of food policies to prevent them from facing food hardship. One of them prioritizes local agricultural production by producing food first for their own family and community consumption. Then any surplus is exchanged through a bartering system with other ayllus.

--

Marialena Huambachano. Enacting Food Sovereignty in New Zealand and Peru: Revitalizing indigenous knowledge, food systems and ecological philosophies. Journal of Sustainable Agriculture.

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

NEW WORLD

There was no such thing as Western civilisation before the European Renaissance. Greece and Rome became part of the narrative of Western civilisation then, not before. With the Renaissance, a double movement began. First, the colonisation of time and the invention of the European Middle Ages. Second – with the emergence of Atlantic trade – the colonisation of space and the invention of New and Old Worlds. This separation, seemingly so natural today, is obviously historical: there could be no Old World without a New one – America. (Later, the Old World would be divided into imperial – Atlantic Europe – and colonial – Asia and Africa.)

A recent proposal to re-inscribe (not to recover or to turn back the clock on) the communal into contemporary debates on pluri-national states is El sistema communal como alternativa al sistema liberal [The Communal System as an Alternative to the Liberal System], by Aymara sociologist Félix Patzi Paco.

The common and the communal: the left and the de-colonial

This is a crucial point, as it highlights the difficulty of equating the communal and the common. The latter is a keyword in the reorientation of the European left today. And that should be no surprise: the idea of ‘the common’ is part of the imaginary of European history. Yet the communal is an-other story: it cannot be easily subsumed by the common, the commune or communism.

The communal is not grounded on the idea of the ‘common’, nor that of the ‘commune’,The communal is something else. It derives from forms of social organisation that existed prior to the Incas and Aztecs, and also from the Incas’ and Aztecs’ experiences of their 500-year relative survival, first under Spanish colonial rule and later under independent nation states. To be done justice, it must be understood not as a leftwing project (in the European sense), but as a de-colonial one.

So what, then, is the ayllu? It is a kind of extended familial community, with a common (real or imaginary) ascendancy that collectively works a common territory. It is something akin to the Greek oikos, which provides the etymological root for ‘economy’. Each ayllu is defined by a territory that includes not just a piece of land, but the eco-system of which that land is one component. The territory is not private property. It is not property at all, but the home for all of those living in and from it. Remember: here, we are not in a capitalist economic organisation

Moreover, the notion of ‘property’ is meaningless in a vision of society in which the goal is working to live and not living to work. It is in this context that Evo Morales has been promoting the concept of ‘the good living’ (sumaj kamaña in Quechua, sumak kawsay in Quichua, allin kausaw in Aymara or buen vivir in Spanish). ‘The good living’ – or ‘to live in harmony’ – is an alternative to ‘development’. While development puts life at the service of growth and accumulation, buen vivir places life first, with institutions at the service of life. That is what ‘living in harmony’ (and not in competition) means.

W. Mignolo

http://www.turbulence.org.uk/turbulence-5/decolonial/

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ceremonia Ritual por el Año Nuevo Andino en Saywite

Ceremonia Ritual por el Año Nuevo Andino en Saywite

► Como todos los años cada 21 de junio se conmemora el Año Nuevo Andino, con éste motivo las autoridades educativas de la DIGEIBIRA-MINEDU, DREA, la UGEL Abancay, asimismo representantes del INC-Apurímac, docentes y estudiantes de la UNAMBA participaron en la ceremonia ritual en el Centro Arqueológico de Saywite.

En esta oportunidad estuvo de cargo en la organización la Dirección Regional de…

View On WordPress

#Allin Kawsay#Año Nuevo Andino#Centro Arqueológico de Saywite#DIGEIBIRA-MINEDU#Dirección Regional de Educación de Apurímac#DREA#energías del Cosmos#INC-Apurímac#Ramiro Sierra Córdova#Richard Hurtado#UGEL – Abancay#Universidad Nacional Micaela Bastidas de Apurímac (UNAMBA)

0 notes

Text

My Notes on Medicinal Plant Wheels or Solar Medicinal Rotations.

As a sort-of-continuation from this post. These are the more solar wheel rotations that deepen the lunar rotations, and add value by taking into account the wider scope of things, directing and carrying our intentions through a longer, more stable path.

Medicinal Plant Wheels (Ruedas de plantas medicinales) usually last a year, but they can last for as long or as short of a time as we need them to. The idea behind it is to rotate medicines taking into account seasonality, with plant allies accompanying, easing us into, our different processes through the year. This connects us to Earth's natural cycles, through the use of plant allies that are fresh, spiritually and physically available during that season, aswell as supports our own inner processes (choosing each ally carefully, catering to our needs for that time of year and intention).

I like to call them Solar rotations, or LuniSolar Rotations (since they combine both lunar and solar cycles), with the added consideration that it is not only preventive medicine, acute care or preparation for a ceremony. It is more constant, unwavering support throughout our inner seasons as the outer seasons of the world change, and demand change and adaptation from us. The physical medicinal properties of each plant are of course taken into account, but there is also a big interest on their spiritual properties, on the medicine that plant ally may bring to our Spirit, through bringing them into our bodies.

Each LuniSolar Month of the Andean agricultural and ritual calendar, an intention is set. One that aligns with that month's energies, with that Pacha. Then, plant allies are sellected according to that intention (and Pacha), to fit each of the stages that will bring us to our goal (planting the seed, growing, maturity and reaping), stages that correspond both to the lunar cycles, aswell as reflect (in a microcosmic way) the overall solar-agricultural year. Plant allies may be consumed (through hot or cold infusions, tinctures, etc) or burned (in sahumos), aswell as accompany us in countless other ways: taking herbal baths, making ofrendas to their Spirit, singing songs to them, carrying their root as a lucky charm, making art with their colors or writing with ink made from them, meditating with their Spirit, putting a branch under your pillow to allow it's Spirit to communicate to you in dreams, and many other things. This is where each person finds their own ways to connect with the Allies' Spirits and allow them to guide our path into Allin Kawsay, Right Living, and through it, to our goals.

The main purpose of these rotations is to acknowledge and align our inner and outer worlds to our actions, and that way, be able to move in the right path toward our intention. Elders tend to say that the Right Path often feels like the path of least resistance, but that doesn't mean it's the easiest path. There may be many challenges to overcome in our path, if even the "least resistance" is, for example, a battle to change something deeply seated in us or in those around us. A healing crisis may be necessary, that will bring true, deep healing, even if painful. "Least resistance" in this case means the most natural course of events. One that honors our truth, aswell as that of the world around us.

"When a healing crisis presents to us after consuming an herbal ally, we do not force our Body and Spirit through it. Never push someone past their limits. People tend to try to "see how much they can stand" when it comes to pain or suffering and that is simply not healthy, and not how we move in andean traditions. Our support [and from our Spirit Allies] comes from love. Deep love. That love doesn't push further when you say you can't take it any more. There is such a thing as "too much medicine", that turns the medicine into poison, and not everyone needs the same dosage for a reason. There must be a healthy balance between the crisis and the positive results we can get from it. When the struggle surpasses the positive results, we cut it. A healing crisis may very well be the indicator to us [the Medicine provider] that the dosage has to be lowered. Lower it as much as it is necessary, until you reach the minimum dosage of a pinch. Just a pinch in a liter of water is more than enough. In even the tiniest pinch of material, the entire Spirit of the Plant can be found, no more than that is necessary for Their Spirit to bring us healing." — words from a Quechua Elder.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Three Principles we must follow when making medicine in the Quechua Andean Tradition are:

Allin Yachay : Good Thoughts & Good Knowledge. Heeding always to Ancestral Wisdom. Knowing what is Right. In modern times this includes all forms of our cultural, traditional knowledge aswell as integrating new western-scientific knowledge.

Allin Munay : keeping a Good Heart, wanting the Right Thing, acting out of kindness, out of love, holding appreciation for our medicinal allies, and in loving remembrance of the Ancestors (human and non-human) who've taught us the medicine we're making. It also includes keeping Right Relation with all our Spirit allies, ancestral, herbal and other kinds, through maintaining proper Reciprocity (Ayni).

Allin Ruray : Good Work. Putting your hands to work on the Right Thing, based on what you know and how you feel. Your Actions must reflect the best out of both Mind and Heart, and be the Right choice, the right action, for both healer and patient. This also requires the supervision of Ancestral Spirits who must approve and allow for the healing process. If there's disapproval from the Spirits, for example, due to a lack of knowledge, a lack of clarity, being the wrong person or simply not being the right time for it, the healing will not occur and the patient must be turned away or redirected elsewhere, where they may find their right path.

These Three Principles represent how the Mind, Heart and Actions of the Healer must be in internal harmony for the act of Healing to happen, aswell as the harmony that must exist externally between Healer and the Natural-Spiritual environment in order to lead the patient back to their own internal and external harmony.

No wrong thought should cloud the mind, no grievances should cloud the heart, and our actions mustn't be unqualified nor uncalled for, to allow the patient to be led back to Good Health, Allin Kay, and Right Living, Allin Kawsay.

#blood and water#Regina Mundi#Herbalism#Indigenous herbalism#Native herbalist#Indigenous herbalist#Andean Medicine#My notes#All this came from me hearing an aymara relative mentioning just how we must be in the Right Mindset to work our medicine#and left me thinking about what that looks like for me#''The Right Mindset“ is these three things for me#Right Mind Right Heart and Right Action#Both inside ourselves and in relation to others#And the Others including humans involved but also Spirits#Ancestors Herbal Allies etc etc etc#yerbatera#khuyasqay yuyokunay

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Few more notes from Huambachano’s article on agro-ecology and egalitarian principles in Andean cosmovision:

[T]he food security framework of Quechua and Māori resonates with conceptions of food sovereignty. Food sovereignty focuses on the human right-based approach to respect and protect people who produce food and the right of individuals to have access to healthy and affordable food (Holt-Gimenez, 2014; Wittman et al. 2010). In resonance with the concept of food sovereignty is the vibrant set of cultural and ecological values of Quechua and Māori that ensures that both the rights of individuals and the human right to food are achieved without compromising the sustainability of the ecosystems.

Collectivity and self-governance

To illustrate this argument, Quechua people exercise their right to define their agricultural and food policy through their ancestral self-governance system known as ayllu. This tradition includes a sector of land that is operated communally alongside chacras or small plots allotted to individual families, and there is an ayllu leader chosen by all ayllu members. Quechua farmers use the ayllu to decide collectively what they want to produce and consume and has prevented them from experiencing issues in their food systems. Thus, good living principles such as the ayllu plays a key role in the communal governance of Andean people to ensure that all members of the ayllu have access to sufficient and nutritious food (Esteva, 2002; Earls, 1998; Gonzales, 2015).

Reciprocity

With regard to the role of the Ayni principle in food security, Peruvian historical accounts suggest that the Ayni played a spiritual and essential role in guiding the Andean people’s ethical principles and beliefs when working in the Tahuantisuyo for their food sustenance (Argumedo & Wong, 2010; Espinoza, 1987; Estermann, 2007; Lajo, 2005; 2011). For example, the Andean people would ‘reciprocate’ the gifts given by their gods – sea (fish),earth (food crops) and sea (water), not only by conducting offerings and rituals before the beginning and at the end of their harvest festival season, but also by applying this Indigenous philosophy in their daily lives (Lajo, 2011). This study supports such argument and extends knowledge by providing evidence that the ayni complements the functioning of the ayllu system, and thus ensures the availability of food for agricultural production.

Research analysis shows that both yanantin and mansitin complement one another and embody the principle of ‘duality’. An example, of these principles is in the transmission of knowledge relating to agricultural practices, where the roles of women and men complement each other. In an attempt by research participants to explain me about yanantin and mansitin, they referred to my experience of observing them cultivating food together. Indeed, I observed that both man and women carefully selected both male and female seeds for pollination. Then the man ploughed the land and together men and women planted the seeds. They added that this process ends in the culmination of the ‘harmonious’ experience of complementary. Thus, it is understood that yanantin and mansitin are principles that are intertwined.

Ecological and social solidarity

Chaninchay, it is an act of solidarity: for example, as one research participant stated ‘’we do community work and go and help the elderly. We go and assist the elderly by gathering food on their behalf and they have a sense of community support”. Other research participants described Chaninchay as “to talk truthfully and with clarity, it is about being kind and having integrity”. Chaninchayis used in the agricultural management systems, which are based on principles of ecological, productive, and social solidarity. At the core of this principle is a profound respect for Pachamama and reverence for the power and fragility of the environment for the attainment of Allin Kawsay – good living (Estermann, 2007, Lajo, 2011).

-

Marialena Huambachano. Enacting Food Sovereignty in New Zealand and Peru: Revitalizing indigenous knowledge, food systems and ecological philosophies. Journal of Sustainable Agriculture.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Communal relationships, healthy ecosystems, and reciprocity in Andean cosmology and ecology: “A Brief Inca-Andean-Quechua ‘Cosmovision’ Glossary”

The ayllu concept of an interdependent community; the ayni concept of reciprocity; the Masintin concept of egalitarianism and the supplementary relation among equals; and non-duality are important concepts in the Andes.

This glossary was compiled and maintained by Giorgio Piacenza Cabrera.

Below are some of the concepts I’ve seen referenced a lot in discourse about ecology, agriculture, and anthropology. To see the full list of terms, visit Cabrera’s site.

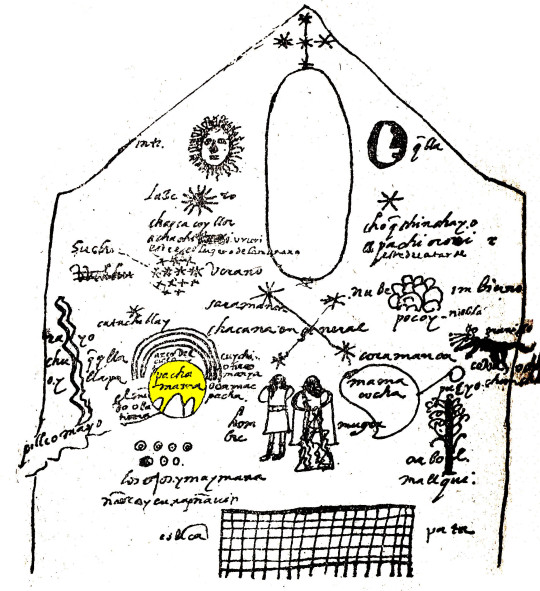

Joan Santa Cruz Pachacuti Salcamaygua's XVI Century "Ideogram" of aspects of Quechua-Inca Cosmology and Cosmovision. [Caption and image by Cabrera, 2012.]

Excerpt:

The following emergent, semi-formal and semi-alphabetically listed glossary reflects my progressing understanding of Quechua terms stemming from a partly lost but also still ongoing Quechua-Andean-Inca “cosmovision.” (...)

More important than exactly defining concepts to the satisfaction a typical Western analytical mind, the less culturally contaminated Quechua people reveal a participatory way of being within a community of multiple relations. These relations define the self- identity of individuals and extend into all of forms of existence.

The main idea in this “cosmovision” is to harmonize with Life (Kawsay Pacha) through various forms of practical and ritualistic exchange or reciprocity. An ‘energy’ and ‘presence’ is felt as moving through all beings from all possible worlds and it is quietly, simply and naturally revered. Relationships (rather than an intense search for ‘oneness’ or for a transcendent ‘Other’ prevailing over multiplicity) are emphasized. While I do not over-romanticize all aspects of Quechua society and culture, I think that it does offer unique “pearls of wisdom” which may be part of a deeper, waiting-to-be-integrated-into-a-planetary-culture knowledge.

-

Alasita: Symbolic physical representation or prototype of a good. Allin: That which is good.

Amaru Runa: Literally means “serpent man.” This refers to wise men and women whose energy and awareness is capable of relating, connecting or threading across the pachas. The sinuous serpent energy is depicted as a “chakana” or three steps in a stair usually depicting the three levels of reality or three “pachas” of the Andean world.

Apu: Powerful lord. A living, conscious, spirit of the mountain protecting and-or overseeing a community or “Ayllu.” Most known apus are male and some (like Mama Simona) are known as female. There are major Apus like “Salcantay,” “Ausangate” and “Machu Picchu” (meaning “old mountain”). There are major apus and minor ones and some have to be kept satisfied with ritual offerings or else they can harm the community. There can be competition among different apus. There also are more local ‘minor’ Apu deities often called “Awkis.”

Ayllu: Community.

Ayni: Reciprocity. A main principle of life and the practice of fair exchanges of work, goods and services. It can occur along with an expectation of an equivalent return (wage wage) or without a specific calculation of how much is has been given and how much it is expected in return. It can only take place with that which is known. The exchange must also be ritualistic or done with feeling.

Masintin: The supplementary relation among equals. It can be a competitive or cooperative relation between equals. Resembles the relation of parts sharing the same hierarchical or holarchical level in a whole.

Kawsay: Living energy or, simply, “life.” Its an infinite energy that forms and sustains every being and also the “pachas.” Kawsay Pacha: The world or cosmos of living energy. Kawsay Puriy: Integration with the living energy. Sumaq Kawsay: Beautiful Life. An inspiring principle.

Kintu: Three healthy coca leaves gently held by to offer prayers and recognition to deities and to divine forces during rituals.

Tawa Chakana: A symbol of interconnection. Four stairs and four-sided bridge. Each side displays the three steps depicting the three main “pachas.” It may show an empty, open center. The “Tawa Chakana” represents how the worlds relate and connect. It is sometimes called the “Inca cross” but it is a symbol that existed even before the Incas (the Quechua people) for instance in the pre-Inca culture of Tiwanako (tawanaco, Tiahuanaco).

Sisan: To flourish.

Sami: Good life energy. “Kawsay” is “Sami” unless blocked and densified into “Hucha.”

Jawa (Hanan): Exterior. Radiating, giving order, abstract, in the open, higher, available. It associates with “Illa” (that which shines, light of wisdom). Time-wise, it might be considered an origin of the past, perhaps (in terms of chaos theory) an attractor toward the past.

Uku: Interior, hidden. That which can give rise to emergence (as from inside the soil). Instinctive, possible, intimate, hidden, chaotic. “Uku” ‘energies’ are experienced with instinct. Time-wise, it might be considered an origin from the future, perhaps (in terms of chaos theory) an attractor toward the future.

Paqarina: Place of origin. Place from where civilization originated.

Pacha: Time, space, world, nature. A level of reality (which in a Western, philosophical sense can be considered as having metaphysical and-or ontological connotations). Representing ‘time’, “pachas” regenerate each other cyclically and each of them exist simultaneously. The past and the future are always latent.

Pachamama: The living Earth Mother. Time and Space as an entire living entity.

Taripay Pacha: Time for recovering or finding our true selves.

Kay Pacha: A realm of actual, or ‘present’ experience. It constitutes a community of shared experience where other relations can take place. It it normally considered the physical world we know but, in my view, any world in which experience can be shared and actualized is a “Kay Pacha.” Every Kay Pacha is actualized by the relationship between the “Jawa” and “Uku” principles. The physical world we also understand as “Kay Pacha” is represented by a Puma. The idea of “Llankay” (work) applies to this active, relational realm. “Munay” (feeling, sentiment) and “Yachay” (understanding) should come together in this experiential “pacha.”

Wiracocha: One if the meanings of “Wiracocha” implies a certain understanding of the idea of non-duality. It refers to deity considered supreme above the rest and from which all other deities, beings, the ‘cosmos’ (I know it’s a Greek term) and life itself originate. “Wira” can be considered as “grease” and “cocha” as water, lake, lagoon or the sea. Since these naturally repel, bringing them together suggests that which can reconcile the repulsion that keeps opposites apart. The name “Illa Teqsi (or Ticsi) Wiracocha Pachayachachi” can be understood as “Illa” (Ineffable Light), “Teqsi” (the “foundation”) “Wiracocha” (that which can relate opposites), “Pachayachachi” (maker or creator of the world). One of the few recognized temples of the Wiracocha cult (a cult perhaps reserved to the priests, nobles, teachers in the Inca Empire) is in Raqchi, Cuzco. When the Spaniards arrived in Peru their God concept was naturally associated with “Wiracocha.”

Nuna: Soul.

Tocapu: 24 kinds of Inca geometrical designs perhaps representing four areas coordinated by an exchange principle.

Waka: Sacred. A sacred place or an object that possesses sacred, spiritual force or presence. In modern Perú most people call “Waka” (or Huaca) pre-hispanic temples which have become archaeological sites.

- [End of excerpt] -

These are just some concepts from the glossary. Cabrera’s site is more extensive.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Qaywakuy a la Pachamama: Agradecimiento a la Madre Tierra

Qaywakuy a la Pachamama: Agradecimiento a la Madre Tierra

» Colectivo Cultural “Pachakuyaq Ayllu” realizó un ritual de agradecimiento a la Madre Tierra en Qorimarka — El pasado 12 de agosto, integrantes de la Asociación Cultural “Pachakuyaq Ayllu” organizaron una Ceremonia Ritual de agradecimiento a la Madre Tierra: Qaywakuy a la Pachamama, dicho acto espiritual se realizó en el Centro Ceremonial de Qorimarka del distrito de Huanipaca.

Participaron…

View On WordPress

#agradecimiento a la Madre Tierra#Allin Kawsay#Centro Ceremonial de Qorimarka#Educación Intercultural Bilingüe#Huanipaca#Pachakuyaq Ayllu#Pachamama#Qaywakuy#Qorimarka

0 notes