#that is will and henry. that is Very Directly What Happened in 1985.

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

rotating henry emily in my mind

#clarifying now that this is abt the games#the fandom at large is missing out on henrys character i think and its such a shame#bc he + his dynamic with william are sososo interesting#like this isnt abt anyone specific but it seems like most people portray him as just another parent that lost a kid (but Plot Relevant)#but the thing is. he was completely complicit in the missing childrens incident. he wasnt actively helping william or anything#but he KNEW it was him From The Beginning. he KNEW william was a threat. but the only time he ever said anything was To William Directly.#we dont talk enough abt the candy cadet story about the boy and the snake. or the “bear of vengeance” cutscenes.#that is will and henry. that is Very Directly What Happened in 1985.#in a lot of theories (coughgametheorycough) its stated that henry kicked william out. except william left on his own.#henry was upset with him yes he tried to confront him yes but he could NEVER kick him out.#the boy could not bear to get rid of the snake#and all of that is. so much more compelling than henry being demoted to the sidelines.#rrghfgrgrrh anyway. ask me about. fnaf.#fnaf#five nights at freddy's#henry emily

30 notes

·

View notes

Note

idk literally anything abt ur fnaf rewrite. ig I'll ask what's up w the cassidy, charlie and henry since they're my favorite fnaf characters

i'll make this quick, so here's a short summary for each-

Henry: actual good dad (because i think, despite what the books say, it would've been great to have Henry be a good dad to contrast with William sucking. and as such Lefty kinda. doesn't exist in the Rewrite. also because Please, I Just Want One Good Father Figure In Fnaf). loves his kids very much. was devastated after Charlie’s death. left the company in 1985 due to not wanting to work directly with William, but was still a technician/engineer for the company (never went to the police because he technically didn't have proof). blames himself for a lot of things that happened.

Charlie: twelve years old, and the oldest of the original dead kids. doesn't fully know what she's doing, but is trying her best. someone give her a break.

Cassidy: technically, Cassidy is the Crying Child! still the Vengeful Spirit, though. he's pissed at a Lot of stuff. there is a fifth MCI kid, though, named Kelsey, although he isn't the Vengeful Spirit. he's actually the more shy one.

#fnaf#fnaf rewrite#henry emily#fnaf charlie#fnaf crying child#hope this explains them well enough. this is just a general gist of the characters#Dandy's Interesting Fnaf Rewrite

2 notes

·

View notes

Note

right back atcha with mr. terrance silver 😎

favorite thing about them: he’s SUCH A SIMP. the way he was like, how dare you come into bronco henry’s dojo when he told you to go away >:( to stingray in the middle of betraying kreese. oh my god, i think it’s terminal. if tumblr were around in 1985 he’d be running a tradwife inspo blog about the importance of making your man feel big and strong, hell maybe he is now

least favorite thing about them: i thought that kreese and silver splitting up over kreese’s weird obsession with johnny would be one of the last things to happen in the series so i’m not sure how much i’m looking forward to terry as a solo villain, we shall see

favorite line: nothing particular, but terry probably has my favorite overall diction of any of the characters (he’s a real drama queen)

brOTP: him and margaret! the corporate bond between a self-loathing gay man and a stern older woman is something that can be so special (i know this because i've watched succession). i also think there's a very compelling alternate universe where he smokes a joint with johnny instead of swearing vengeance upon him. they hang out and bitch about kreese and his whole thing, the way normal people do at unpleasant family gatherings.

OTP: him and kreese. i think terry's happiest life is one spent tolling for ducks. kreese rubs him behind his ears every time he drops a bird at his feet, and at night he sleeps curled up at the foot of their bed. they’re happy together the way they were before his dad got in the way, before kreese abandoned him, before johnny lawrence ruined everything just as it was finally coming together

nOTP: it's not really a notp, but i want it on the record that i think silverusso is dull 🤷♀️ it lacks a strong personal connection! they want what johnny and kreese have so bad but they'll never be a 10th as rancid

random headcanon: he suffers from delusions where he believe that lana del rey is singing directly to him about his relationship with kreese and has attempted (unsuccessfully) to take legal action against her over it on multiple occasions. also if you cut off his hair he loses the ability to do karate

unpopular opinion: i don’t think his plan to christen the old cobra kai dojo with johnny’s blood wasn’t vengeful or a test, so much as a characteristically cuckoo apology? he was reasserting his own loyalty and, ehe, devotion in earnest after mistakenly ‘breaking rank’ (a normal person might have bought flowers). it’s spelled out early on via robby that he misinterprets kreese’s attempts to psspsspss his karate son/legacy back into his life as vindictive. i also got the sense that kreese’s "he’s a great guy, unless you beat him at monopoly” thing has been pretty par for the course in their relationship, thus nothing to retaliate over--i’m super fond of the notion that he was being serious when he told mr miyagi that kreese wasn’t always like that. if he ever actually suspected that kreese’s affections had shifted, he was in denial of that up until the very last minute. sincerity and fallibility are more interesting to me

song i associate with them: scars by papa roach. i’m sorry, he aggravates an aspect of my id that’s been buried since the end of middle school. sorry again

favorite picture of them: every frame of him in that stupid sparkly silver sweatshirt is unbearably cute, especially the ones where he’s on the verge of tears. do you think that’s available in the general cobra kai merch store, or did he have it made just for himself?

#i forgot about these :(#cobra kai#kreese trampled the sole parameter terry imposed on their relationship his one selfish desire without even noticing it men are pigs#PIGS!!!!#asks

20 notes

·

View notes

Link

via Politics – FiveThirtyEight

Television shows are writing the 25th Amendment into their ripped-from-the-headlines storylines. Pundits debate the possibilities of the removal and succession of the president if he is incapacitated. Even former FBI Director James Comey has weighed in on whether Donald Trump is “medically unfit to be president.” (He doesn’t think so.) In the unlikely — but politically fascinating — event that a Cabinet were to use the power to oust a sitting president, what would come next?

Let’s take a deeper look at the 25th Amendment and think about what each section of it has meant in the past — and what it might mean for Trump-era politics.

Section 1. In case of the removal of the President from office or of his death or resignation, the Vice President shall become President.

The amendment’s initial section revisits what Article II of the Constitution set up from the beginning — the vice president takes over if the president dies or is unable to serve — but with clearer language to clean up previous constitutional confusion. When William Henry Harrison died shortly after his inauguration in 1841, there were questions about whether John Tyler, nicknamed “His Accidency,” was truly the president or just an “acting” president of some kind. Tyler made clear his intent to fully occupy the office and do everything an elected president would have done — and he forged his own path separate from Harrison. Since then, seven presidents have taken office after a presidential death (all before the 25th Amendment was ratified) and one after a resignation. In this way, the amendment codified the status quo.1

What this means now: Many have already discussed the possibility of a President Pence. But it’s worth underscoring how much he represents a different, more establishment brand of Republicanism than Trump. If Trump were to be removed for incapacity, it would be an interesting test of whether Trumpism could survive if carried out by a leader with a very different temperament and political profile — or if that leader would abandon Trumpism altogether.

Section 2. Whenever there is a vacancy in the office of the Vice President, the President shall nominate a Vice President who shall take office upon confirmation by a majority vote of both Houses of Congress.

Before this, if the vice president became president, there was … no vice president. That exact situation accounted for 24 years of U.S. history, including a period just before Congress took up the 25th Amendment in 1965. From taking the oath of office in November 1963 until he and Hubert Humphrey were sworn in after winning election in 1964, Lyndon Johnson had no vice president. Instead, the next two people in line (per the 1947 Presidential Succession Act) were both in poor health and, in the words of Roll Call’s David Hawkings, “a combined 157 years old.” This section of the 25th Amendment has since been invoked twice, when Spiro Agnew resigned in 1973 and Richard Nixon chose Gerald Ford to replace him, and when Ford succeeded Nixon as president in 1974 and chose Nelson Rockefeller as his VP.

What this means now: If Pence became president, he could choose his own veep, subject to congressional approval. Depending on party control of Congress, that could get interesting. It would offer a chance for Pence to either choose a Trump ally or move the party in a different direction. Pence’s choice could say a lot about whether invoking the amendment was a reaction to Trump personally or a repudiation of his overall approach to politics.

Section 3. Whenever the President transmits to the President pro tempore of the Senate and the Speaker of the House of Representatives his written declaration that he is unable to discharge the powers and duties of his office, and until he transmits to them a written declaration to the contrary, such powers and duties shall be discharged by the Vice President as Acting President.

This section seems like it should be pretty straightforward. It was invoked without controversy twice in the early 2000s when President George W. Bush signed over power to Vice President Dick Cheney for a few hours during sedation for routine medical procedures. But it can get fuzzy.

The 25th Amendment wasn’t invoked when Ronald Reagan was shot in 1981, despite the fact that the White House physician kept a copy of the amendment in his bag. Bill Clinton didn’t formally put Section 3 provisions in place when he had knee surgery in 1997, saying that he was never under general anesthesia. However, Clinton’s press secretary indicated that the chief of staff had been in close contact with Vice President Al Gore’s staff in case “anything about the 25th Amendment is indicated.”

And there is disagreement on whether Reagan properly invoked the 25th Amendment in 1985 when he underwent surgery to remove a polyp from his colon. Reagan submitted letters to the House speaker and Senate president pro tempore designating Vice President George H.W. Bush as acting president, citing an “existing agreement” between the two. The letters also stated that Reagan was not specifically activating the process laid out in the 25th Amendment and that he did not believe that “the drafters of this Amendment intended its application to situations such as the instant one.”

Some argue that this message reflected the basic spirit of the 25th Amendment, while others suggest that because it wasn’t a formal invocation, it’s not really an instance of a president using the 25th Amendment.

What this means now: When people talk today about invoking the 25th Amendment, they aren’t talking about Trump having minor surgery and temporarily handing the reins to Pence. But the resistance of earlier presidents to using the 25th Amendment in such cases, even though the amendment seems directly designed for those instances, illustrates the depth of the struggle and complications over control of presidential power.

Section 4 (first paragraph). Whenever the Vice President and a majority of either the principal officers of the executive departments or of such other body as Congress may by law provide, transmit to the President pro tempore of the Senate and the Speaker of the House of Representatives their written declaration that the President is unable to discharge the powers and duties of his office, the Vice President shall immediately assume the powers and duties of the office as Acting President.

Here’s where we transition from historical explanation to future speculation. This section has never been invoked, and it has a number of ambiguous phrases that leave it open to a range of possibilities. For starters, who exactly gets to decide that the president isn’t able to serve? The conventional interpretation of the amendment is that it needs the vice president plus a majority of the Cabinet.2

But with the deciders well agreed upon, if not explicitly spelled out, what does “unable to discharge powers and duties of the office” mean, and who gets to provide the definition? The context for the 25th Amendment was pretty clearly aimed at the kind of physical and mental incapacities that come after strokes, heart attacks and bullets. Woodrow Wilson’s stroke, Dwight Eisenhower’s heart attack and John F. Kennedy’s assassination (and the related worry about what would have happened if he had survived but been incapacitated) all informed the debate about the amendment. But there’s nothing in the text that actually requires a diagnosis.

What this means now: This could end up being a test of the authority of the Cabinet as much as anything else. The amendment empowers the Cabinet to take this action. But what we see with Section 3 is that a lot of anxiety about giving up power still looms over the process. Even if the Cabinet followed the letter of the law, it might still look like a palace coup. In order to get around this, the Cabinet has to have a certain amount of stature — an issue that would be put to the test if it sought to remove the commander in chief.

Section 4 (second paragraph). Thereafter, when the President transmits to the President pro tempore of the Senate and the Speaker of the House of Representatives his written declaration that no inability exists, he shall resume the powers and duties of his office unless the Vice President and a majority of either the principal officers of the executive department or of such other body as Congress may by law provide, transmit within four days to the President pro tempore of the Senate and the Speaker of the House of Representatives their written declaration that the President is unable to discharge the powers and duties of his office. Thereupon Congress shall decide the issue, assembling within forty-eight hours for that purpose if not in session.

In other words, the 25th Amendment provides a way for the president to respond to accusations of a lack of fitness. And that’s where things get interesting. After the president offers a declaration that he or she is able to serve, the Cabinet has four days to object and respond. But who gets to be president during that time? The text isn’t clear. It goes on to say:

If the Congress, within twenty-one days after receipt of the latter written declaration, or, if Congress is not in session, within twenty-one days after Congress is required to assemble, determines by two-thirds vote of both Houses that the President is unable to discharge the powers and duties of his office, the Vice President shall continue to discharge the same as Acting President; otherwise, the President shall resume the powers and duties of his office.

Many parts of the Constitution are vague, but this one sets the country up for a pretty wild ride. Constitutional scholar Brian Kalt points out: “Section 4 is drafted less than perfectly. The best reading of Section 4’s text — and the clear message from its drafting history — is that when the president declares he is able, he does not retake power until either (1) four days pass without the vice-president and Cabinet disagreeing; or (2) he, the president, wins the vote in Congress. But the text is ambiguous on this point and commentators have frequently misread it as allowing the president to retake power immediately upon his declaration of ability.”

This opens up a possibility that Kalt describes in detail in his book “Constitutional Cliffhangers,” in which the country ends up with two presidents and two Cabinets. In the fictional scenario, the vice president and 11 Cabinet members agree to remove a president whose behavior has been erratic. But she conspires with her chief of staff to “declare that no inability exists,” reclaims power, and fires and replaces the Cabinet that removed her. In this setup, an amendment aimed at preventing a constitutional crises has now created one.

Kalt and others have pointed out that, in addition to the ambiguity of the text, it is difficult to remove a president through the 25th Amendment. In the event that the president disagrees about the incapacity issue, the amendment requires two-thirds of the House and Senate to remove him or her (as opposed to the impeachment process, which requires a simple majority of the House to impeach and two-thirds of the Senate to convict).

What this means now: The provision of the amendment that everyone’s been talking about is the one we know the least about. Since the 25th Amendment was ratified, presidents, vice presidents and White House officials have tread very cautiously around the provisions of Section 4. It seems fairly safe to say that there are lingering legitimacy issues when it comes to members of the executive branch actually talking about removing the president and replacing him or her with the vice president. And even under perfectly innocuous circumstances, presidents seem very reluctant to entertain the idea of being temporarily replaced under the amendment’s provisions.

All of this points to a conclusion we probably already knew: The Cabinet, especially as it’s currently constituted, is pretty unlikely to take action against Trump. But Congress has its own set of political pressures, and if the Democratic “wave” happens, we may see a serious attempt to go after the president. If impeachment proceedings don’t get off the ground, Congress could turn to the 25th Amendment: While Congress can’t initiate removal of the president under the amendment, it can convene a body to investigate the president’s fitness to serve — and such legislation has already been proposed.

Convening an investigative commission might seem like a bureaucratic and indirect step compared with the drama of impeachment. But such a commission might be easier to sell to members of Congress who are wary of impeachment. It might also be a way to address the legitimacy issues that otherwise seem to plague the 25th Amendment — a president’s removal from office may be less likely to be seen as a coup if it comes from the people’s elected representatives. And voting to create a commission might be more palatable for congressional Republicans.

One of the arguments against invoking the 25th Amendment to remove Trump is that it wasn’t really intended for this purpose. But looking at how the amendment has been used in practice reveals that political context matters, and so does legitimacy. Presidents have avoided activating Section 3 of the article, appearing reluctant to concede even temporary power to their own vice presidents. And Section 4 spells out a process that is legally unclear. It’s likely that any discussion of the 25th Amendment will be about the politics of the moment rather than the precise text of its provisions. Whether we see it put into practice will depend on whether Congress or members of the Cabinet see political benefit in doing so. A critical part of that process would be to overcome the legitimacy challenges and political disruption that using the 25th Amendment would create.

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ford Bronco: A generational look back ahead of the brand-new SUV’s expose

What a long, unusual journey it’s been.

Ford.

Yes, it’s really been three years since Ford first revealed the return of the Bronco at the 2017 Detroit Auto Program

From the start of the nameplate’s production in 1965, the Bronco has actually lived a number of unique lives.

1966-1977 Bronco: Pony young boy leaves evictions

Regardless of growing to inhabit larger sectors in future models, the initial Bronco was destined to be a compact SUV, going up against the likes of the International Harvester Scout and the Jeep CJ-5 Recreational utility vehicles were still brand-new at this moment, giving Ford the opportunity to take a crack at a blossoming section.

None aside from famous auto officer Lee Iacocca authorized the first-generation Bronco for production in early1964 Its chassis was special in that no other Ford-family vehicle utilized its short, 92- inch wheelbase. Four-wheel drive was basic initially, rocking Dana drivetrain components from the axles to the transfer case.

At launch, the Bronco’s sole engine was a 2.8-liter I6 (based on the engine in the Falcon sedan) making 105 horse power. The next year, a 200- hp, 4.7-liter V8 would be used, broadening to 5 liters by the 1969 design year. A 4.7-liter I6 was the basic powertrain offering beginning in the 1973 design year, continuing through the generation’s end in 1977.

The first-gen Bronco’s appearance was no-nonsense, selecting things like flat glass panels to keep expenses in control and simple-to-press sheetmetal types. It was readily available in 3 different body styles, including the normal two-door setup, in addition to more interesting versions like an open-top roadster. As the years went on, though, these bodies were ultimately shelved in favor of the most popular two-door “wagon” layout. Sales balanced between 14,000 and 25,000 units per year throughout its run.

1978-1979 Bronco: The embiggening

Considering that the Bronco’s beginning, the SUV section began removing. But compact SUVs weren’t the object of everybody’s attention by the late 1970 s– larger models grew in popularity, despite the side effects of the 1973 oil crisis. With lorries like the Chevrolet K5 Blazer and the Jeep Cherokee, Ford required to respond to the market’s impulses.

Therefore, the second-gen Bronco grew– a lot. Borrowing its chassis from the F-100 pickup (a trend that would continue in later generations), the 1978 Bronco included an entire foot to its wheelbase, in addition to growing 11 inches larger and 4 inches taller. A Dana 44 strong front axle worked alongside a Ford 9-inch rear axle, making this the last Bronco without independent front suspension. Four-wheel drive stayed standard for the second-gen Bronco. A three-door wagon was the only body style available this time around.

For the second generation, two V8 engines lived under the Bronco’s hood. Both the 5.8-liter and 6.6-liter V8s produced almost the very same horse power (156 and 158, respectively), but the 6.6-liter had the torque advantage at 277 lb-ft versus the smaller sized V8’s 262 lb-ft. In 1979, both variants got a catalytic converter that slightly impacted horsepower output.

The growing Bronco accomplished a few things. Sharing a base with the F-100 suggested brand-new animal comforts like cooling and a tilting steering wheel column. This recently grown young boy also sold like gangbusters, with Ford pressing 77,917 Broncos out the door in 1978 and 104,038 in 1979.

1980-1986 Bronco: Taking shape

The oil crises demanded sleeker, more efficient automobiles. While the Bronco’s dimensions stayed mostly the exact same for the third generation, the powertrain range was widened. A 4.9-liter I6 was standard, together with a manual transmission. The base V8 was a 4.9-liter unit, with a 5.8-liter Windsor V8 and 5.8-liter 351 M V8 also available. Updates like fuel injection slowly worked their way into the lineup, too.

In keeping with the second-gen Bronco’s family tree, the third-generation Bronco as soon as again obtained the majority of its updates from the F-Series pickup truck line. From the doors forward, it’s basically the same as the pickup, including the positioning of Ford’s blue oval logo. The Bronco also used the very same trims, including the outdoor-themed Eddie Bauer edition that made its method to numerous Ford SUVs in time.

While it didn’t quite reach the very same sales success as its forebear, the Mk 3 Bronco did pretty well for itself. Sales hovered around 40,000 systems each year from 1980 to 1985, when it shot up to 54,000 systems, completing its run in 1986 with 62,127 examples offered.

1984-1990 Ford Bronco II is a complement, not a replacement

See all images

1984-1990 Bronco II: The stepsibling

Through the 1980 s, Ford didn’t precisely have the best history with putting “II” after a name. The Mustang II? Not precisely anybody’s favorite Mustang. Henry Ford II? Let’s … simply not go there. Then there’s the Bronco II.

The Bronco II was never suggested to be a replacement for its bigger brother or sister. Derived directly from the smaller sized Ranger pickup, and packing dimensions closer to the first-generation Bronco, the Bronco II was meant to take on a brand-new class of energy lorries. 4×4 was once again basic, although rear-wheel drive was provided in 1986.

In addition to borrowing appearances and body parts from the Ranger, the Bronco II also yoinked its powertrain. Early Bronco II models rocked a 2.8-liter V6 with 115 hp, growing to 2.9 liters and 140 hp in the 1986 design year. A turbodiesel was at one point readily available, however it wasn’t that excellent and many people simply avoided over it.

The Bronco II died to make room for the Ford Explorer, however before that happened it was dogged with safety-related controversies. Particularly, the automobile was thought to be vulnerable to rollovers, and lawsuits followed Ford well into the 1990 s.

Not every new generation requires to be groundbreaking.

Ford.

1987-1991 Bronco: Some new stuff, absolutely nothing insane

The fourth-gen Ford Bronco entered production in 1986 with a raft of modifications. The brand-new Bronco picked up all the exact same looks as the eighth-gen F-150, which was also brand-new at the time. It’s a little sleeker, with aero improvements focused on enhancing performance. The interior was revamped, too, however that wasn’t for fuel economy’s sake. Individuals similar to new stuff.

There were some new technical enhancements. The fourth-gen model picked up push-button controls for its four-wheel-drive system, and both the base 4.9-liter I6 and high-output 5.8-liter V8 intensified injection. Five-speed manual transmissions replaced the old four-speed setup, and the optional automated transmission gained an additional forward gear, also.

Sales were OKAY to begin, averaging about 43,000 units up until a spike saw 69,470 sales in1989 That number dropped to about 55,000 the list below year, with 1991 seeing simply 25,001 Broncos heading out the door.

1992-1996 Bronco: The Juice is loose

The last O.G. Bronco came out for the 1992 model year, following the intro of the ninth-gen Ford F-150

The Bronco also got a number of security updates, consisting of crumple zones and, for the 1994 design year, a standard motorist air bag.

Of course, we can’t talk about the last Bronco without discussing O.J. Simpson. Ford/Instagram.

2021 Ford Bronco: Letting the horses out once again

A quarter of a century has actually passed since the Ford Bronco vanished from dealers, however that’s set to alter with the intro of the 2021 model this year.

While Chevrolet went and turned its truck-based Blazer into a unibody cookie-cutter crossover meant to fill the sliver of white space in between the Equinox and Traverse, the Bronco will serve as something a bit more specialized. Rocking 2 different body styles, in addition to a smaller Bronco Sport version that will certainly be much better than the Bronco II, Ford’s latest SUV is prepared to regain buyers that may have gathered to cars like the Jeep Wrangler

With the exception of specific truck trims, Ford hasn’t had an effectively large off-roader in a long time. Thinking about the teasers and leakages we have actually seen thus far, it appears like the Huge Blue Oval is set to correct that product gap in a big method.

Read More

from Job Search Tips https://jobsearchtips.net/ford-bronco-a-generational-look-back-ahead-of-the-brand-new-suvs-expose/

0 notes

Text

The Quintessential Group B Homologation Special – The Lancia Delta S4 Stradale

The Lancia Delta S4 was one of the fastest and most advanced Group B rally cars ever developed, it would also directly lead to the entire Group B class being shut down by the FIA. In some ways the Delta S4 was the quintessential Group B machine – it was a lighting fast, fire-breathing rally car that proved both successful and lethal.

What is Group B?

For the uninitiated, Group B was founded in 1982 by the FIA alongside Group A and Group C. Group A was for production-derived vehicles with a minimum homologation production numbers of 5000 vehicles per year, and there were strict rules governing power, weight, and technology. Group C had far fewer restrictions but there were limits placed on fuel load and minimum vehicle weight.

Group B was the Goldilocks class that had very few restrictions on technology and power, and the minimum homologation production number was just 200 vehicles per year. This allowed manufacturers to build the fastest and most advanced rally cars the world had ever seen, in 1982 Group B cars were producing ~250 hp and by 1986 this number had increased to well over 500 hp.

Many consider Group B to be a true golden era in the history of racing, the cars that were built to compete are now revered as legends and road-legal Group B homologation cars change hands for oftentimes eye-watering figures.

The class was cancelled abruptly at the end of 1986 due to a number of accidents. The crash that killed Henri Toivonen and his co-driver Sergio Cresto in the 1986 Tour de Corse when they missed a corner in their Lancia Delta S4 is often pointed to as the moment the FIA chose to end Group B permanently.

The Lancia Delta S4 Stradale

The Lancia Delta S4 Stradale was the street-legal homologation car built by Lancia in order to allow the more hard-edged Lancia Delta S4 to race – “stradale” means “road” in Italian.

The FIA required that 200 be built however it’s widely believed that Lancia only built 80 or so examples, there’s a long history of manufacturers fudging the numbers to get cars homologated so Lancia are by no means alone in this regard – if this is what truly happened.

The cost of the Delta S4 Stradale made it a challenge to sell when it was released in 1985, it cost approximately 100 million Lira in 1985 which was 5 times the cost of the Lancia HF Turbo.

The reason for this price difference would become immediately clear once you saw beneath the silhouette bodywork however. The Delta S4 may have looked similar to its stamped steel siblings from the factory but it shared almost no parts with them other than the badge.

Lancia developed a chromoly space frame for the Delta S4 that was closely based on the Lancia 037, the engine was mounted amidships where the back seat would normally have been, and power was sent to all four wheels via a central differential co-developed by Hewland that sent 60 to 70% of torque to the rear limited slip diff and the remaining torque to the open front diff.

Advanced fully independent suspension was used, also based somewhat on the 037, with twin shock absorbers per wheel in the rear and a single coil over per wheel up front. Competition disc brakes were used on all four corners, and the body was made of composites with front and rear sections that were easily removable for accident repairs and mechanic access.

The car was powered by one of the first twincharged engines, an engine that uses both a supercharger and a turbocharger. Twincharging was chosen for the 1.8 litre, DOHC inline-4 S4 engine as it was fitted with a hefty KKK K27 turbo with a boost threshold of 4500 rpm – the supercharger provided boost at engine revs below this level to keep power predictable and avoid a sudden surge as the engine passed the 4500 rpm mark. Power was approximately 400 hp initially but this number quickly rose with development, and the car was producing over 500 hp by the time the program was cancelled.

Lancia introduced the Delta S4 at the 1985 RAC Rally and it would immediately take both 1st and 2nd place in the hands of Henri Toivonen and Markku Alén respectively. The car would take a slew of victories despite its relative lack of development time, its continued development would be cut short by the tragic crash of Toivonen and co-driver Sergio Cresto in the 1986 Tour de Corse.

The Stradale version of the mighty Delta S4 is now one of the most highly sought after Group B homologation specials, it has an interior that included many luxuries not found on the rall cars, like air conditioning and sound proofing. The Stradale Delta S4 produces 247 hp and 215 ft lbs of torque, making it a spritely performer, particularly by the standards of the era.

The car you see here is due to cross the auction block with Bonhams on the 6th of February in Paris, with an estimated hammer price of between €550,000 and €650,000. If you’d like to read more about it or register to bid you can click here.

Images courtesy of Bonhams

The post The Quintessential Group B Homologation Special – The Lancia Delta S4 Stradale appeared first on Silodrome.

source https://silodrome.com/lancia-delta-s4/

0 notes

Text

currently on Netflix

Todrick Hall grew up in the small town of Plainview, Tex., many miles from a legitimate theater. But at age 10, he saw three live performances that changed his life: Cats, Jekyll & Hyde and Joseph and the Amazing Technicolor Dreamcoat. And he’s now convinced they led to his career as a Broadway performer. But they may also have had something to do with his appearance on television as a contestant on “American Idol,” because the “live performances” he saw as a child were not on a stage—they were on his TV screen. “It was the live aspect that interested me,” Hall recalled. “I thought it was so cool how the scenery would move and nobody was moving it.”

I spoke to Hall in 2011, when he was a member of the ensemble in the then-current Broadway musical “Memphis,” which had agreed to what was then considered an experiment. A camera crew had taped five live performances of the show at Broadway’s Shubert Theater, in order to create a picture-perfect movie version of the show, which was presented on screens in more than 500 movie theaters across the United State

“I was very supportive of it,” Hall told me then. “Some people in the company were very ‘anti.’ They were of the old-school idea that musicals should remain on the stage.”

Much has happened in the last eight years. Todrick Hall himself has gone from TV watcher, ensemble member and American Idol contestant to “YouTube sensation,” which no doubt helped lift him into starring roles on Broadway in Kinky Boots and Waitress. And taping live Broadway shows for the screen is no longer seen as an experiment. It’s a routine practice, and it’s moved from movie theaters to home computers.

Life is not all that’s gone online in a major way. So has theater.

Betty Corwin at a taping of a Broadway show for TOFT

Todrick Hall in his Beyonce Youtube video

Audible audiobooks made from plays

from 1900 film of Sarah Bernhardt in Hamlet

Thoughts about this remarkable cultural shift were sparked with the news this week of the death of Betty Corwin, at the age of 98. Forty-nine years ago, Corwin did something truly unprecedented. She created the Theater on Film and Tape Archive, housed at the New York Public Library for the Performing Arts at Lincoln Center. The idea behind TOFT, as it’s called by those in the know, was to preserve productions for posterity, and for researchers. It took her masterful diplomatic skills to convince all parties involved that the archiving would be of benefit, not harm.

There are now more than 8,000 recordings, including, as her Times appreciation/obituary points out, “every play in August Wilson’s 20th-century cycle, starting with “Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom” in 1985; the 1978 New York Shakespeare Festival production of “The Taming of the Shrew,” starring Meryl Streep and Raul Julia; the original Broadway production of “Angels in America,” recorded in 1994; and the 1988 Lincoln Center Theater production of “Waiting for Godot,” starring Robin Williams and Steve Martin.” One can view them on monitors roughly the size of desktop computers.

TOFT remains limited to scholars and researchers (although the definition encompasses anybody from students to actors) But, as the technology has improved, so has the incentive to monetize the recording of live theater..

Netflix, which began in 1998 as an online DVD rental service, introduced streaming services in 2007, and first produced original online programming (“House of Cards”) in 2013, now offers a steady, well, stream of shows that originated on Broadway. And the trend on Netflix seems clear.

Look at the Broadway titles currently available on Netflix. Four of them – Cabaret (1972) The Phantom of the Opera (2004), Mamma Mia (2008) and Jersey Boys (2014) – are movie adaptations of the original stage musicals. But four others (most of them more recent) were recorded directly from the Broadway stage – “Shrek” (2013), “Oh, Hello” (2017) and both “Springsteen on Broadway” and “Latin History for Morons” (2018.) And more are on the way – “American Son” is coming to Netflix on November 1.

BroadwayHD, which was launched in 2015 as an online subscription service, was the first (according to the Guinness Book of World Records) to live stream a Broadway show. In 2016. It streamed the revival of “She Loves Me” in real time.

It’s unclear whether live-streaming of theater will take off. But recording of live theater for future playback is without question increasing, and taking an odd and potential consequential turn. Audible, a subsidiary of Amazon that is the world’s largest producer and seller of “audiobooks,” has invested in theater in a major way. Yesterday, it announced that it will record “Sea Wall/A Life,” which is running through September 29th on Broadway’s Hudson Theater starring with Jake Gyllenhaal & Tom Sturridge, and turn it into what it calls “an Audible original production.” Audible has taken over the Off-Broadway MinettaLane Theater, and commissions plays (all of them so far solo shows) that are presented on stage, and subsequently sold as audiobooks. It has also created a $5 million “Emerging Playwrights Fund” to develop original “one- and two-person audio plays driven by language and voice….”

One can argue that the effort to distribute recordings of live theater is nothing new; it goes back to the invention of film and radio. As early as 1900, Sarah Bernhardt’s stage performance as Hamlet was immortalized on film (which was recently projected during the Broadway production of Theresa Rebeck’s play “Bernhardt/Hamlet“) Richard Burton’s 1964 Broadway turn in the same role was taped, transferred to film, and shown in some 1,000 movie theaters throughout the nation.

Television has also frequently turned its cameras to the stage: In 1948, a program called “Tonight on Broadway” began broadcasting live 30-minute excerpts directly from Broadway stages, offering TV viewers black-and-white glimpses of such shows as “Mister Roberts” with Henry Fonda and “The Heiress” with Wendy Hiller and Basil Rathbone. This was the precursor to such television series as “American Playhouse” and the long-running “Great Performances,” both on PBS.

But the new turn, represented by Audible’s specification for its commissions, prompts a new question to add to the many that the issue already provokes: Will the streaming of theater change the actual content of what we see and hear not just on recordings, but on the stage?

Putting Broadway Live on Screen and Stream: From Sarah Bernhardt to Betty Corwin to Todrick Hall to Netflix and Audible Todrick Hall grew up in the small town of Plainview, Tex., many miles from a legitimate theater.

0 notes

Text

The super enemies of the humankind are the crooked languages, says Brightquang. www.brightquang.com

Exclusive: After resigning over the Watergate political-spying scandal, President Nixon sought to rewrite the history of his Vietnam War strategies to deny swapping lives for political advantage, but newly released documents say otherwise, writes James DiEugenio.

By James DiEugenio

Richard Nixon spent years rebuilding his tattered reputation after he resigned from office in disgrace on Aug. 9, 1974. The rehabilitation project was codenamed “The Wizard.” The idea was to position himself as an elder statesman of foreign policy, a Wise Man. And to a remarkable degree through the sale of his memoirs, his appearance with David Frost in a series of highly rated interviews, and the publication of at least eight books after that Nixon largely succeeded in his goal.

There was another aspect of that plan: to do all he could to keep his presidential papers and tapes classified, which, through a series of legal maneuvers, he managed to achieve in large part. Therefore, much of what he and Henry Kissinger wrote about in their memoirs could stand, largely unchallenged.

President Richard Nixon with his then-National Security Advisor Henry Kissinger in 1972.

It was not until years after his death that the bulk of the Nixon papers and tapes were opened up to the light of day. And Kissinger’s private papers will not be declassified until five years after his death. With that kind of arrangement, it was fairly easy for Nixon to sell himself as the Sage of San Clemente, but two new books based on the long-delayed declassified record one by Ken Hughes and the other by William Burr and Jeffrey Kimball undermine much of Nixon’s rehabilitation.

For instance, in 1985 at the peak of President Ronald Reagan’s political power Nixon wrote No More Vietnams,making several dubious claims about the long conflict which included wars of independence by Vietnam against both France and the United States.

In the book, Nixon tried to insinuate that Vietnam was not really one country for a very long time and that the split between north and south was a natural demarcation. He also declared that the Vietnam War had been won under his administration, and he insisted that he never really considered bombing the irrigation dikes, using tactical nuclear weapons, or employing the strategy of a “decent interval” to mask an American defeat for political purposes.

Nixon’s Story

In No More Vietnams, Nixon said that after going through a series of option papers furnished to him by National Security Advisor Henry Kissinger, he decided on a five-point program for peace in Vietnam. (Nixon, pgs. 104-07) This program consisted of Vietnamization, i. e., turning over the fighting of the war to the South Vietnamese army (the ARVN); pacification, which was a clear-and-hold strategy for maintaining territory in the south; diplomatic isolation of North Vietnam from its allies, China and the Soviet Union; peace negotiations with very few preconditions; and gradual withdrawal of American combat troops. Nixon asserted that this program was successful.

But the currently declassified record does not support Nixon’s version of history, either in the particulars of what was attempted or in Nixon’s assessment of its success.

When Richard Nixon came into office he was keenly aware of what had happened to his predecessor Lyndon Johnson, who had escalated the war to heights that President Kennedy had never imagined, let alone envisaged. The war of attrition strategy that LBJ and General William Westmoreland had decided upon did not work. And the high American casualties it caused eroded support for the war domestically. Nixon told his Chief of Staff Bob Haldeman that he would not end up like LBJ, a prisoner in his own White House.

Therefore, Nixon wanted recommendations that would shock the enemy, even beyond the massive bombing campaigns and other bloody tactics employed by Johnson. As authors Burr and Kimball note in their new book Nixon’s Nuclear Specter, Nixon was very much influenced by two modes of thought.

First, as Vice President from 1953-61, he was under the tutelage of Secretary of State John Foster Dulles and President Dwight Eisenhower, who advocated a policy of nuclear brinksmanship, that is the willingness to threaten nuclear war if need be. Dulles felt that since the United States had a large lead in atomic weapons that the Russians would back down in the face of certain annihilation.

Nixon was also impressed by the alleged threat of President Eisenhower to use atomic weapons if North Korea and China did not bargain in good faith to end the Korean War. Nixon actually talked about this in a private meeting with southern politicians at the 1968 GOP convention. (Burr and Kimball, Chapter 2)

Dulles also threatened to use atomic weapons in Vietnam. Burr and Kimball note the proposal by Dulles to break the Viet Minh’s siege of French troops at Dien Bien Phu by a massive air mission featuring the use of three atomic bombs. Though Nixon claimed in No More Vietnams that the atomic option was not seriously considered (Nixon, p. 30), the truth appears to have been more ambiguous, that Nixon thought the siege could be lifted without atomic weapons but he was not against using them. Eisenhower ultimately vetoed their use when he could not get Great Britain to go along.

Playing the Madman

Later, when in the Oval Office, Nixon tempered this nuclear brinksmanship for the simple reason that the Russians had significantly closed the gap in atomic stockpiles. So, as Burr and Kimball describe it, Nixon and Kissinger wanted to modify the Eisenhower-Dulles brinksmanship with the “uncertainty effect” or as Nixon sometimes called it, the Madman Theory. In other words, instead of overtly threatening to use atomic bombs, Nixon would have an intermediary pass on word to the North Vietnamese leadership that Nixon was so unhinged that he might resort to nuclear weapons if he didn’t get his way. Or, as Nixon explained to Haldeman, if you act crazy, the incredible becomes credible:

“They’ll believe any threat of force that Nixon makes because it’s Nixon. I call it the Madman Theory, Bob. I want the North Vietnamese to believe I’ve reached the point where I might do anything to stop the war. We’ll just slip the word to them that ‘for God’s sake you know Nixon is obsessed about communism. We can’t restrain him when he’s angry, and he has his hand on the nuclear button.’”

Nixon believed this trick would work, saying “Ho Chi Minh himself will be in Paris in two days begging for peace.”

Kissinger once told special consultant Leonard Garment to convey to the Soviets that Nixon was somewhat nutty and unpredictable. Kissinger bought into the concept so much so that he was part of the act: the idea was for Nixon to play the “bad cop” and Kissinger the “good cop.”

Another reason that Nixon and Kissinger advocated the Madman Theory was that they understood that Vietnamization and pacification would take years. And they did not think they could sustain public opinion on the war for that long. Secretary of Defense Melvin Laird and Secretary of State William Rogers both thought they could, their opinions were peripheral because Nixon and Kissinger had concentrated the foreign policy apparatus in the White House.

Playing for Time

Privately, Nixon did not think America could win the war, so he wanted to do something unexpected, shocking, “over the top.” As Burr and Kimball note, in 1969, Nixon told his speechwriters Ray Price, Pat Buchanan and Richard Whalen: “I’ve come to the conclusion that there’s no way to win the war. But we can’t say that, of course. In fact we have to seem to say the opposite, just to keep some degree of bargaining leverage.”

In a phone call with Kissinger, Nixon said, “In Saigon, the tendency is to fight the war for victory. But you and I know it won’t happen it is impossible. Even Gen. Abrams agreed.”

These ideas were expressed very early in 1969 in a document called NSSM-1, a study memorandum as opposed to an action memorandum with Kissinger asking for opinions on war strategy from those directly involved. The general consensus was that the other side had “options over which we have little or no control” which would help them “continue the war almost indefinitely.” (ibid, Chapter 3)

Author Ken Hughes in Fatal Politics agrees. Nixon wanted to know if South Vietnam could survive without American troops there. All of the military figures he asked replied that President Nguyen van Thieu’s government could not take on both the Viet Cong and the regular North Vietnamese army. And, the United States could not help South Vietnam enough for it to survive on its own. (Hughes, pgs. 14-15)

As Hughes notes, Nixon understood that this bitter truth needed maximum spin to make it acceptable for the public. So he said, “Shall we leave Vietnam in a way that by our own actions consciously turns the country over to the Communists? Or shall we leave in a way that gives the South Vietnamese a reasonable chance to survive as a free people? My plan will end American involvement in a way that will provide that chance.” (ibid, p. 15)

If the U.S. media allowed the argument to be framed like that, which it did, then the hopeless cause did have a political upside. As Kissinger told Nixon, “The only consolation we have is that the people who put us into this position are going to be destroyed by the right. They are going to be destroyed. The liberals and radicals are going to be killed. This is, above all, a rightwing country.” (ibid, p. 19)

Could anything be less honest, less democratic or more self-serving? Knowing that their critics were correct, and that the war could not be won, Nixon and Kissinger wanted to portray the people who were right about the war as betraying both America and South Vietnam.

Political Worries

Just how calculated was Nixon about America’s withdrawal from Vietnam? Republican Sen. Hugh Scott warned him about getting out by the end of 1972, or “another man may be standing on the platform” on Inauguration Day 1973. (ibid, p. 23) Nixon told his staff that Scott should not be saying things like this in public.

But, in private, the GOP actually polled on the issue. It was from these polls that Nixon tailored his speeches. He understood that only 39 percent of the public approved a Dec. 31, 1971 withdrawal, if it meant a U.S. defeat. When the question was posed as withdrawal, even if it meant a communist takeover, the percentage declined to 27 percent. Nixon studied the polls assiduously. He told Haldeman, “That’s the word. We say Communist takeover.” (ibid, p. 24)

The polls revealed another hot button issue: getting our POW’s back. This was even more sensitive with the public than the “Communist takeover” issue. Therefore, during a press conference, when asked about Scott’s public warning, Nixon replied that the date of withdrawal should not be related to any election day. The important thing was that he “didn’t want one American to be in Vietnam one day longer than is necessary to achieve the two goals that I have mentioned: the release of our prisoners and the capacity of the South Vietnamese to defend themselves against a Communist takeover.” He then repeated that meme two more times. The press couldn’t avoid it. (Hughes, p. 25)

Still, although Nixon and Kissinger understood they could not win the war in a conventional sense, they were willing to try other methods in the short run to get a better and quicker settlement, especially if it included getting North Vietnamese troops out of South Vietnam. Therefore, in 1969, he and Kissinger elicited suggestions from inside the White House, the Pentagon, the CIA, and Rand Corporation, through Daniel Ellsberg. These included a limited invasion of North Vietnam and Laos, mining the harbors and bombing the north, a full-scale invasion of North Vietnam, and operations in Cambodia.

Or as Kissinger put it, “We should develop alternate plans for possible escalating military actions with the motive of convincing the Soviets that the war may get out of hand.” Kissinger also said that bombing Cambodia would convey the proper message to Moscow.

If anything shows that Kissinger was as backward in his thinking about Indochina as Nixon, this does. For as Burr and Kimball show — through Dobrynin’s memos to Moscow — the Russians could not understand why the White House would think the Kremlin had such influence with Hanoi. Moscow wanted to deal on a variety of issues, including arms agreements and the Middle East.

So far from Kissinger’s vaunted “linkage” theory furthering the agenda with Russia, it’s clear from Dobrynin that it hindered that agenda. In other words, the remnants of a colonial conflict in the Third World were stopping progress in ameliorating the Cold War. This was the subtotal of the Nixon/Kissinger geopolitical accounting sheet.

Judging Kissinger on Vietnam

Just how unbalanced was Kissinger on Vietnam? In April 1969, there was a shoot-down of an American observation plane off the coast of Korea. When White House adviser John Ehrlichman asked Kissinger how far the escalation could go, Kissinger replied it could go nuclear.

In a memo to Nixon, Kissinger advised using tactical nuclear weapons. He wrote that “all hell would break loose for two months”, referring to domestic demonstrations. But he then concluded that the end result would be positive: “there will be peace in Asia.”

Kissinger was referring, of course, to the effectiveness of the Madman Theory. In reading these two books, it is often hard to decipher who is more dangerous in their thinking, Nixon or Kissinger.

In the first phase of their approach to the Vietnam issue, Nixon and Kissinger decided upon two alternatives. The first was the secret bombing of Cambodia. In his interview with David Frost, Nixon expressed no regrets about either the bombing or the invasion. In fact, he said, he wished he had done it sooner, which is a puzzling statement because the bombing of Cambodia was among the first things he authorized. Nixon told Frost that the bombing and the later invasion of Cambodia had positive results: they garnered a lot of enemy supplies, lowered American casualties in Vietnam, and hurt the Viet Cong war effort.

Frost did not press the former president with the obvious follow-up: But Mr. Nixon, you started another war and you helped depose Cambodia’s charismatic ruler, Prince Sihanouk. And because the Viet Cong were driven deeper into Cambodia, Nixon then began bombing the rest of the country, not just the border areas, leading to the victory of the radical Khmer Rouge and the deaths of more than one million Cambodians.

This all indicates just how imprisoned Nixon and Kissinger were by the ideas of John Foster Dulles and his visions of a communist monolith with orders emanating from Moscow’s Comintern, a unified global movement controlled by the Kremlin. Like the Domino Theory, this was never sound thinking. In fact, the Sino-Soviet border dispute, which stemmed back to 1962, showed that communist movements were not monolithic. So the idea that Moscow could control Hanoi, or that the communists in Cambodia were controlled by the Viet Cong, this all ended up being disastrously wrong.

As Sihanouk told author William Shawcross after the Cambodian catastrophe unfolded, General Lon Nol, who seized power from Prince Sihanouk, was nothing without the military actions of Nixon and Kissinger, and “the Khmer Rouge were nothing without Lon Nol.” (Shawcross, Sideshow, p. 391)

But further, as Shawcross demonstrates, the immediate intent of the Cambodian invasion was to seek and destroy the so-called COSVN, the supposed command-and-control base for the communist forces in South Vietnam supposedly based on the border inside Cambodia. No such command center was ever found. (ibid, p. 171)

Why the Drop in Casualties?

As for Nixon’s other claim, American casualties declined in Indochina because of troop rotation, that is, the ARVN were pushed to the front lines with the Americans in support. Or as one commander said after the Cambodian invasion: it was essential that American fatalities be cut back, “If necessary, we must do it by edict.” (ibid, p. 172)

But this is not all that Nixon tried in the time frame of 1969-70, his first two years in office. At Kissinger’s request he also attempted a secret mission to Moscow by Wall Street lawyer Cyrus Vance. Part of Kissinger’s linkage theory, Vance was to tell the Soviets that if they leaned on Hanoi to accept a Nixonian framework for negotiations, then the administration would be willing to deal on other fronts, and there would be little or no escalation. The negotiations on Vietnam included a coalition government, and the survival of Thieu’s government for at least five years, which would have been two years beyond the 1972 election. (As we shall see, this is the beginning of the final “decent interval” strategy.)

The Vance mission was coupled with what Burr and Kimball call a “mining ruse.” The Navy would do an exercise to try and make the Russians think they were going to mine Haiphong and five other North Vietnamese harbors. Yet, for reasons stated above, Nixon overrated linkage, and the tactic did not work. But as Kissinger said, “If in doubt, we bomb Cambodia.” Which they did.

As the authors note, Nixon had urged President Johnson in 1967 to extend the bombing throughout Indochina, into Cambodia and Laos. Johnson had studied these and other options but found too many liabilities. He had even studied the blockading of ports but concluded that Hanoi would compensate for a blockade in a relatively short time by utilizing overland routes and off-shore unloading.

But what Johnson did not factor in was the Nixon/Kissinger Madman Theory. For example, when a State Department representative brought up the overall military ineffectiveness of the Cambodian bombing, Kissinger replied, “That doesn’t bother me we’ll hit something.” He also told an assistant, “Always keep them guessing.” The problem was, the “shock effect” ended up being as mythical as linkage.

In 1969, after the failure of the Vance mission, the mining ruse, the warnings to Dobrynin, and the continued bombing of Cambodia, which went on in secret for 14 months, Nixon still had not given up on his Madman Theory. He sent a message to Hanoi saying that if a resolution was not in the works by November, “he will regretfully find himself obliged to have recourse to measures of great consequence and force.”

What were these consequences? Nixon had wanted to mine Haiphong for a long time. But, as did Johnson, he was getting different opinions about its effectiveness. So he considered massive interdiction bombing of the north coupled with a blockade of Sihanoukville, the Cambodian port that was part of the Ho Chi Minh trail apparatus on the west coast of Cambodia.

Plus one other tactic: Kissinger suggested to his staff that the interdiction bombing use tactical nuclear weapons for overland passes near the Chinese border. But the use of tactical nukes would have created an even greater domestic disturbance than the Cambodian invasion had done. Secretary of Defense Melvin Laird objected to the whole agenda. He said it would not be effective and it would create too much domestic strife.

Backing Up Threats

So Nixon and Kissinger decided on something short of the nuclear option. After all, Nixon had sent a veiled ultimatum to Hanoi about “great consequence and force.” They had to back it up. The two decided on a worldwide nuclear alert instead, a giant nuclear war exercise that would simulate actual military maneuvers in attempting to mimic what the U.S. would do if it were preparing for a nuclear strike.

As Burr and Kimball write, this was another outmoded vestige of 1950s Cold War thinking: “It was intended to signal Washington’s anger at Moscow’s support of North Vietnam and to jar the Soviet leaders into using their leverage to induce Hanoi to make diplomatic concessions.” (Burr and Kimball, Chapter 9)

It was designed to be detected by the Soviets, but not detectable at home. For instance, the DEFCON levels were not actually elevated. The alert went on for about three weeks, with all kinds of military maneuvers at sea and on land. Finally, Dobrynin called for a meeting. Kissinger was buoyant. Maybe the ploy had worked.

But it didn’t. The ambassador was angry and upset, but not about the alert. He said that while the Russians wanted to deal on nuclear weapons, Nixon was as obsessed with Vietnam as LBJ was. In other words, Dobrynin and the Soviets were perceptive about what was really happening. Nixon tried to salvage the meeting with talk about how keeping American fatalities low in Vietnam would aid détente, which further blew the cover off the nuclear alert.

Burr and Kimball show just how wedded the self-styled foreign policy mavens were to the Madman Theory. After the meeting, Nixon realized he had not done well in accordance with the whole nuclear alert, Madman idea. He asked Kissinger to bring back Dobrynin so they could play act the Madman idea better.

The authors then note that, although Haiphong was later mined, the mining was not effective, as Nixon had been warned. In other words, the Madman idea and linkage were both duds.

Nixon and Kissinger then turned to Laird’s plan, a Vietnamization program, a mix of U.S. troop withdrawals, turning more of the fighting over to the ARVN, and negotiations. The November 1969 Madman timetable was tossed aside and the long haul of gradual U.S. disengagement was being faced. Accordingly, Nixon and Kissinger started sending new messages to the north. And far from isolating Hanoi, both China and Russia served as messengers for these new ideas.

The White House told Dobrynin that after all American troops were out, Vietnam would no longer be America’s concern. In extension of this idea, America would not even mind if Vietnam was unified under Hanoi leadership.

Kissinger told the Chinese that America would not return after withdrawing. In his notebooks for his meeting with Zhou En Lai, Kissinger wrote, “We want a decent interval. You have our assurances.” (Burr and Kimball, Epilogue)

Timing the Departure

But when would the American troops depart? As Ken Hughes writes, Nixon at first wanted the final departure to be by December of 1971. But Kissinger talked him out of this. It was much safer politically to have the final withdrawal after the 1972 election. If Saigon fell after, it was too late to say Nixon’s policies were responsible. (Fatal Politics, p. 3)

Kissinger also impressed on Nixon the need not to announce a timetable in advance. Since all their previous schemes had failed, they had to have some leverage for the Paris peace talks.

But there was a problem. The exposure of the secret bombing of Cambodia began to put pressure on Congress to begin to cut off funding for those operations. Therefore, when Nixon also invaded Laos, this was done with ARVN troops. It did not go very well, but that did not matter to Nixon: “However Laos comes out, we have got to claim it was a success.” (Hughes, p. 14)

While there was little progress at the official negotiations, that too was irrelevant because Kissinger had arranged for so-called “secret talks” at a residential home in Paris. There was no headway at these talks until late May 1971. Prior to this, Nixon had insisted on withdrawal of North Vietnamese troops from South Vietnam.

But in May, Kissinger reversed himself on two issues. First, there would be no American residual force left behind. Second, there would be a cease-fire in place. That is, no withdrawal of North Vietnamese troops. As Kissinger said to Nixon, they would still be free to bomb the north, but “the only problem is to prevent the collapse in 1972.” (ibid, pgs. 27-28) The Decent Interval strategy was now the modus operandi.

And this strategy would serve Nixon’s reelection interests, too. As Kissinger told Nixon, “If we can, in October of ’72 go around the country saying we ended the war and the Democrats wanted to turn it over to the communists then we’re in great shape.” To which Nixon replied, “I know exactly what we’re up to.” (ibid, p. 29) Since this was all done in secret, they could get away with a purely political ploy even though its resulted in the needless deaths of hundreds of thousands of soldiers and civilians. All this was done to make sure Nixon was reelected and the Democrats looked like wimps.

Kissinger understood this linkage between the war’s illusionary success and politics. He reminded Nixon, “If Cambodia, Laos and Vietnam go down the drain in September of 1972, they they’ll say you went into those … you spoiled so many lives, just to wind up where you could have been in the first year.” (ibid, p. 30)

In fact, the President’s February 1972 trip to China was directly related to the slow progress on Vietnam. Kissinger said, “For every reason, we’ve got to have a diversion from Vietnam in this country for awhile.” To which Nixon replied, “That’s the point isn’t it?” (ibid, p.32)

A Decent Interval

In preparations for China, Kissinger told Zhou En Lai that Nixon needed an interval of a year or two after American departure for Saigon to fall. (ibid, p. 35) He told Zhou, “The outcome of my logic is that we are putting a time interval between the military outcome and the political outcome.” (ibid, p. 79)

But aware of this, Hanoi made one last push for victory with the Easter Offensive of 1972. Remarkably successful at first, air power managed to stall it and then push it back. During this giant air operation, Nixon returned to his Foster Dulles brinksmanship form, asking Kissinger, should we “take the dikes out now?”

Kissinger replied, “That will drown about 200,000 people.”

Nixon said, “Well no, no I’d rather use a nuclear bomb. Have you got that ready?”

When Kissinger demurred by saying Nixon wouldn’t use it anyway, the President replied, “I just want you to think big Henry, for Christ’s sake.” (Burr and Kimball, Epilogue)

The American press took the wrong message from this. What it actually symbolized was that Saigon could not survive without massive American aid and firepower. (Hughes, p. 61) But even with this huge air campaign, the Pentagon figured that the north could keep up its war effort for at least two more years, even with interdiction bombing.

The political ramification of the renewed fighting was that it pushed the final settlement back in time, which Nixon saw as a political benefit, a tsunami for his reelection.

Nixon: “The advantage, Henry, of trying to settle now, even if you’re ten points ahead, is that that will ensure a hell of a landslide.”

Kissinger: “If we can get that done, then we can screw them after Election Day if necessary. And I think this could finish the destruction of McGovern” [the Democratic presidential nominee].

Nixon: “Oh yes, and the doves, which is just as important.”

The next day, Aug. 3, 1972, Kissinger returned to the theme: “So we’ve got to find some formula that holds the thing together a year or two, after which, after a year, Mr. President, Vietnam will be a backwater no one will give a damn.” (Hughes, pgs. 84-85)

All of this history renders absurd the speeches of Ronald Reagan at the time: “President Nixon’s idealism is such that he believes the people of South Vietnam should have the opportunity to live under whatever form of government they themselves choose.” (Hughes, p. 86) While Reagan was whistling in the dark, the Hanoi negotiator Le Duc Tho understood what was happening. He even said to Kissinger, “reunification will be decided upon after a suitable interval following the signing.”

Kissinger and Nixon even knew the whole election commission idea for reunification was a joke. Kissinger called it, “all baloney. There’ll never be elections.” Nixon agreed by saying that the war will then resume, but “we’ll be gone.” (ibid, p. 88)

Thieu’s Complaint

The problem in October 1972 was not Hanoi; it was President Thieu. He understood that with 150,000 North Vietnamese regulars in the south, the writing was on the wall for his future. So Kissinger got reassurances from Hanoi that they would not use the Ho Chi Minh Trail after America left, though Kissinger and Nixon knew this was a lie. (ibid, p. 94)

When Thieu still balked, Nixon said he would sign the agreement unilaterally. How badly did Kissinger steamroll Thieu? When he brought him the final agreements to sign, Thieu noticed that they only referred to three countries being in Indochina: Laos, Cambodia and North Vietnam. Kissinger tried to explain this away as a mistake. (Hughes, p. 118)

When Kissinger announced in October 1972 that peace was at hand, he understood this was false but it was political gold.

Nixon: “Of course, the point is, they think you’ve got peace. . . but that’s all right,. Let them think it.” (ibid, p. 132)

Nixon got Senators Barry Goldwater and John Stennis to debate cutting off aid for Saigon. This got Thieu to sign. (ibid, p. 158)

In January 1973, the agreement was formalized. It was all a sham. There was no lull in the fighting, there were no elections, and there was no halt in the supplies down the Ho Chi Minh Trail. As the military knew, Saigon was no match for the Viet Cong and the regular army of North Vietnam. And Thieu did not buy the letters Nixon wrote him about resumed bombing if Hanoi violated the treaty.

But Nixon had one more trick up his sleeve, which he pulled out as an excuse for the defeat in his 1985 book, No More Vietnams. He wrote that Congress lost the “victory” he had won by gradually cutting off aid to Indochina beginning in 1973. (Nixon, p. 178)

It’s true that the Democratic caucuses did vote for this, but anyone can tell by looking at the numbers that Nixon could have sustained a veto if he tried. And, in fact, he had vetoed a bill to ban American bombing in Cambodia on June 27 with the House falling 35 votes short in the override attempt.

Rep. Gerald Ford, R-Michigan, rose and said, “If military action is required in Southeast Asia after August 15, 1973, the President will ask congressional authority and will abide by the decision that is made by the House and Senate.”

The Democrats didn’t buy Ford’s assurance. So Ford called Nixon and returned to the podium to say Nixon had reaffirmed his pledge. With that, the borderline Republicans joined in a shut-off vote of 278-124. In the Senate the vote was 64-26. (Hughes, p. 165)

Having Congress take the lead meant that Nixon did not have to even think of revisiting Vietnam. He could claim he was stabbed in the back by Congress. As Hughes notes, it would have been better for Congress politically to double the funding requests just to show it was all for show.

As Hughes writes, this strategy of arranging a phony peace, which disguised an American defeat, was repeated in Iraq. President George W. Bush rejected troop withdrawals in 2007 and then launched “the surge,” which cost another 1,000 American lives but averted an outright military defeat on Bush’s watch. Bush then signed an agreement with his hand-picked Iraqi government, allowing American troops to remain in Iraq for three more years and passing the disaster on to President Barack Obama.

Hughes ends by writing that Nixon’s myth of a “victory” in Vietnam masks cowardice for political courage and replaces patriotism with opportunism. Nixon prolonged a lost war. He then faked a peace. And he then schemed to shift the blame onto Congress.

As long as that truth is masked, other presidents can play politics with the lives hundred of thousands of innocent civilians, and tens of thousands of American soldiers.

At Nixon’s 1994 funeral, Kissinger tried to commemorate their legacy by listing their foreign policy achievements. The first one he listed was a peace agreement in Vietnam. The last one was the airing of a human rights agenda that helped break apart the Soviet domination in Eastern Europe. These two books make those declarations not just specious, but a bit obscene.

James DiEugenio is a researcher and writer on the assassination of President John F. Kennedy and other mysteries of that era. His most recent book is Reclaiming Parkland.

0 notes

Text

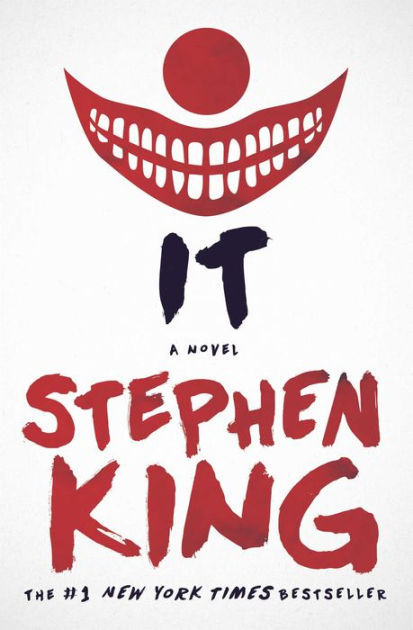

IT by: Stephen King

Finished: 1/24/2018

Hey everybody! It has been awhile since I’ve posted a review, but that is only because I’ve been reading this behemoth of a book (1153 pages, yikes). Here are some of my thoughts on what I read (Just a heads up, this review will most likely be significantly longer than my other reviews due to the length of the book):

Overview: It is about a group of seven kids that must deal with a menace in their town. This menace is pure evil and It feeds off of fear and brutally maims children, taking the form of their nightmares.This menace often takes the form of a clown that goes by the name of Pennywise that haunts Derry, Maine, about every 27 years. The children think they have dealt with It until they get a call 27 years later. This time It wants revenge.

Writing: I really enjoyed the writing in this. King goes into detail about everything that goes on in the quaint little town of Derry, most of the events being quite evil. This book is set in 1985 when all the children have grown up into adults and have forgotten most of the horrific things that they had to go through. About half the book is told in flashbacks to 1958 when they had to confront It. I think what really hooked me was the history of the town and just how awful all of the residents can be. A lot of the horrifying things that go in this book are things that Pennywise isn’t even (directly) a part of. I don’t want to go into too much detail, but there are some pretty messed up things that happen within Derry. This book definitely shocked me with some of the brutality that occurs throughout. By far my favorite thing within this book is when the Losers club (the 7 main children) are just hanging out and having fun. King does such an amazing job at writing the simplicity of childhood and I thought there was just a really nice heart-warming feeling while I read these parts. I will say that if you are kind of sensitive towards the subjects of racism or homophobia you might not want to read this. Like I said, a lot of the people in this fictional town are really bad. Now the really important question that everyone wants to know: Is the book scary? This book didn’t give me nightmares or anything, but I will say that this book is super creepy and disturbing. A good majority of the book is psychological horror with some gory stuff thrown in throughout. King set up a very elaborate backstory for Derry that unfolds as the book goes on and a lot of it was super interesting. Also, the dialogue was spot on. When one of the kids are saying something it sounds like something a kid would say. I really liked that. I can’t really think of any negatives as far of the writing goes. King did a great job of having just the right amount of description and the conversations flowed really well.

Characters: Alright folks, strap in because this is an important one. This novel has some of the best character development I’ve ever read. You almost feel like you grew up with these characters and watched as they matured. Not only that but you then get to learn about how specific events from their childhood unconsciously affected them. A big theme in this book is about growing up, the innocence of childhood, and how much we really forget as we grow older. I want to briefly go over the main cast of characters and kind of why I love them all.