#teraterpeton

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Allokotosaur (archosauromorph) propaganda: Teraterpeton is literally the reptile version of a plague doctor. Definitely gender vibes right there.

reptiles are the only TRUE genders

all of these clades can be found on the wikipedias

421 notes

·

View notes

Text

Drepanosaurs were a weird little group of tree-climbing Triassic reptiles with prehensile claw-tipped tails, chameleon-like bodies, humped backs, grasping feet, long necks, and somewhat bird-like skulls that may have been tipped with toothless beaks in some species.

Recently some of them have been recognized as also having adaptations for digging and ripping into insect nests, similar to modern anteaters, with highly specialized forelimb bones and a massively enlarged hoked claw on each hand.

And now we have another one of these digging drepanosaurs: Unguinychus onyx, whose name delightfully translates to "claw claw claw"!

Living in what is now New Mexico, USA during the late Triassic, around 215-208 million years ago, Unguinychus is only known from its enlarged hand claws but was probably similar in size to some of its close relatives, likely around 40cm long (~1'4").

Based on skin impressions from the early drepanosaur Kyrgyzsaurus it also would have been covered in small scales, possibly with a skin crest and a chameleon-like throat sac.

Drepanosaurs' evolutionary relationships are rather unclear, with various studies classifying them as an early branch of diapsid reptiles, as close relatives of the gliding kuehneosaurids, or as protorosaurian archosauromorphs. But recently another idea has been proposed, instead placing them slightly further up the archosauromorph evolutionary tree in the allokotosaur lineage close to trilophosaurids – and notably making them very closely related to fellow Triassic bird-headed weirdo Teraterpeton.

———

NixIllustration.com | Tumblr | Patreon

References:

Alifanov, V. R., and E. N. Kurochkin. "Kyrgyzsaurus bukhanchenkoi gen. et sp. nov., a new reptile from the Triassic of southwestern Kyrgyzstan." Paleontological Journal 45 (2011): 639-647. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/257843064_Kyrgyzsaurus_bukhanchenkoi_gen_et_sp_nov_a_New_Reptile_from_the_Triassic_of_Southwestern_Kyrgyzstan

Buffa, Valentin, et al. "‘Birds’ of two feathers: Avicranium renestoi and the paraphyly of bird-headed reptiles (Diapsida:‘Avicephala’)." Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society (2024): zlae050. https://doi.org/10.1093/zoolinnean/zlae050

Jenkins, Xavier A., et al. "Using manual ungual morphology to predict substrate use in the Drepanosauromorpha and the description of a new species." Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 40.5 (2020): e1810058. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/344545876_Using_Manual_Ungual_Morphology_to_Predict_Substrate_Use_in_the_Drepanosauromorpha_and_the_Description_of_a_New_Species

Pugh, Isaac, et al. "A new drepanosauromorph (Diapsida) from East–Central New Mexico and diversity of drepanosaur morphology and ecology at the Upper Triassic Homestead Site at Garita Creek (Triassic: mid-Norian)." Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology (2024): e2363202. https://doi.org/10.1080/02724634.2024.2363202

#science illustration#paleontology#paleoart#palaeoblr#unguinychus#clawclawclaw#drepanosauridae#drepanosauromorpha#drepanosaur#allokotosauria#maybe#archosauromorpha#reptile#art#triassic weirdos#THE CLAAAWWW

262 notes

·

View notes

Text

BoYS

Snoot and chonky

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

Teraterpeton hrynewichorum

By @stolpergeist

Etymology: Wonderful creeping thing

First Described By: Sues, 2003

Classification: Biota, Archaea, Proteoarchaeota, Asgardarchaeota, Eukaryota, Neokaryota, Scotokaryota, Opimoda, Podiata, Amorphea, Obazoa, Opisthokonta, Holozoa, Filozoa, Choanozoa, Animalia, Eumetazoa, Parahoxozoa, Bilateria, Nephrozoa, Deuterostomia, Chordata, Olfactores, Vertebrata, Craniata, Gnathostomata, Eugnathostomata, Osteichthyes, Sarcopterygii, Rhipidistia, Tetrapodomorpha, Eotetrapodiformes, Elpistostegalia, Stegocephalia, Tetrapoda, Reptiliomorpha, Amniota, Sauropsida, Eureptilia, Romeriida, Diapsida, Neodiapsida, Sauria, Archosauromorpha, Crocopoda, Allokotosauria, Trilophosauridae

Status: Extinct

Time and Place: 237 to 227 million years ago, in the Carnian of the Late Triassic

Teraterpeton is known from Nova Scotia.

Physical Description: Teraterpeton was a bizarre archosauromorph. It is an allokotosaur, a member of a clade of relatively large herbivorous archosauromorphs. Some of them, including Teraterpeton, have snouts that lack teeth at the front, but have teeth posteriorly. These toothless regions may have been covered by a “beak” of sorts, similar to those that would evolve many times in ornithodirans. Teraterpeton stands out from its relatives because its snout is very long; about half of the skull would have been the front beak! The front of the upper and lower jaws are toothless and would have tapered to a narrow point anteriorly. The teeth, which were present further back in the jaw, were shaped so that the upper teeth formed a perfect contact with the lower teeth.

Further back on the skull, both the orbit and the nasal openings were large. Also interestingly, one of the temporal fenestrae at the back of the skull is closed. Most diapsids have two large holes in the back of the skull, upper and lower temporal fenestrae. In Teraterpeton, the lower temporal fenestra is closed. This “euryapsid” condition is also present in the marine ichthyosaurs and sauropterygians. Teraterpeton’s neck vertebrae Teraterpeton would have had moderately long legs and a sprawing gait. The claws on both the hands and feet were relatively large.

Diet: Teraterpeton was herbivorous; it likely used the beak at the front to snip off plant matter and used the posterior teeth to chew them up.

Behavior: Unfortunately, little is known about the behavior of allokotosaurs. The limbs were not well-suited for deep digging, but the large claws indicate that they may have been used to grab at something in the ground, such as exposed roots. Like the related Trilophosaurus, Teraterpeton probably grew relatively slowly, and may have had a lower metabolism than more derived archosauromorphs.

Ecosystem: The Wolfville Formation of Nova Scotia is a sandstone, indicating that Teraterpeton lived in a desert. It’s difficult identifying most of the skeletons from this area, as preservation is generally not great, but other creatures that lived in the area include the cynodont Arctotraversodon and the temnospondyl “Metoposaurus” bakeri.

Other: Allokotosaurs are a truly bizarre group of archosauromorphs. There are two main clades: Azendohsauridae, which includes Azendohsaurus, Malerisaurus, and Shringasaurus, and Trilophosauridae, which includes Teraterpeton, Trilophosaurus, Spinosuchus, Variodens, and three scrappy things from Russia that were first identified as procolophonids. There’s also the long-necked, insectivorous Pamelaria, which is just kind of its own thing.

~ By Henry Thomas

Sources under the cut

Marsh, A.D., Parker, W.G., Kligman, B.T., Lessner, E.J. 2017. Bonebed of a carnivorous archosauromorph from the Chinle Formation (Late Triassic: Norian) of Petrified Forest National PArk. GSA Annual Meeting, Seattle.

Pritchard, A.C., Sues, H.-D. 2019. Postcranial remains of Teraterpeton hrynewichorum (Reptilia: Archosauromorpha) and the mosaic evolution of the saurian postcranial skeleton. Journal of Systematic Palaeontology.

Sues, H.-D. 2003. An unusual new archosauromorph reptile from the Upper Triassic Wolfville Formation of Nova Scotia. Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences 40: 635-649.

Werning, S., Irmis, R. Reconstruction the ontogeny of the Triassic basal archosauromorph Trilophosaurus using bone histology and limb bone morphometrics. 70th Annual Meeting of the Society of Vertebate Paleontology, Pittsburgh.

#teraterpeton#allokotosaur#archosauromorph#triassic#triassic madness#triassic march madness#prehistoric life#paleontology

178 notes

·

View notes

Text

#Archovember Day 18 - Teraterpeton hrynewichorum

These guys were /weird/. With a long, possibly-beaked, head and a sprawled lizard-like body, Teraterpeton’s name translates to “wonderful creeping thing.”

Teraterpeton is so weird that I got stuck for a very long time trying to figure out what to color it. No one really knows what niche it filled, though it seems to have been highly specialized for /something/. I ended up looking into where it was found, Nova Scotia, and at the time it was alive the area was a desert. I then looked up Canadian desert animals, and decided a badger fit Teraterpeton’s body plan the closest, so I used an American badger as my starting point. So, here we are, with a strange, beaked badger thing.

#my art#Teraterpeton#Teraterpeton hrynewichorum#archosauromorphs#reptiles#Archovember#Archovember2020#Dinovember#Dinovember2020#DrawDinovember#DrawDinovember2020#SaritaDrawsPalaeo

13 notes

·

View notes

Photo

#ArchosaurArtApril Day 27 - #teraterpeton . There have been so many arcgosaurs I have never even heard of but I have been glad to learn about and this one is among them. It sort of reminds me of a kiwi bird. But as an archosaur. . . . . #archosaur#sketch #sketchbook #paleoart #animalart#animals #animalartist #drawing #pencildrawing#pencilart #traditionaldrawing #traditionalartist#traditionalart #dailydrawing #dailyart #instart#instartist #artistsoninstagram #smltart #authenticpad https://www.instagram.com/p/Bw5UCjMlTLx/?utm_source=ig_tumblr_share&igshid=1lic3lg9jsf7a

#archosaurartapril#teraterpeton#archosaur#sketch#sketchbook#paleoart#animalart#animals#animalartist#drawing#pencildrawing#pencilart#traditionaldrawing#traditionalartist#traditionalart#dailydrawing#dailyart#instart#instartist#artistsoninstagram#smltart#authenticpad

19 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Never before has there been an animal with such a perfect name. (Art by Liam Elward)

1 note

·

View note

Text

Foreigna is a planet full of Genetically modified Teraterpetons, highly derived descendants of unknown cephalopods, and highly derived descendants of jawless fish. In the beginning, there where only one vertebrate, a Foregon. A genetically modified Teraterpeton that was left to evolve on this planet for millions of years. Small invertebrates alongside them evolved to fill niches and produce weird life forms. No one knows why they're there. Some people theorized that hyperintelligent beings created this world just for the pure fun of it and for curiosity. Others argue that an unknown force of physics created this world. Some others claim that God created it. Overall, no one knows who made it. Here, you'll find a lengthy guide to the planet's flora and fauna that many brave scientists and explorers have discovered on Foreigna.

(Be free to criticize. I’m only going to show the present day of this project, rather than the whole timeline. And also, I have an account in youtube which you can see videos.)

#speculative evolution#spec evo#speculative fiction#speculative zoology#digital art#art#illustration

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

if teraterpeton doesnt win triassic march madness then we riot

it looks like a plague doctor mask brought to life.

its name means wonderful creeping thing. thats because it is a wonderful creeping thing.

how can you argue with either of those? you cant so dont try

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Weird Heads Month #07: The Wonderful Creeping Thing

The Triassic was an incredibly weird time, full of evolutionary experiments in the wake of the worst mass extinction in Earth's history.

Teraterpeton hrynewichorum here was part of group known as allokotosaurs, a lineage of mostly-herbivorous archosauromorphs that also included the long-necked bull-horned Shringasaurus.

Living in Nova Scotia during the Late Triassic, around 235-221 million years ago, Teraterpeton (meaning "wonderful creeping thing") was first named in the early 2000s based on a skull and partial skeleton, with some additional skeletal material being described recently in 2019.

Its head had a confusing mix of anatomical features, with a long beak-like toothless snout at the front of its jaws, small sharp interlocking cheek teeth further back, a huge nasal opening, and a closed-up fenestra at the back of its skull making it look more like the skulls of marine reptiles.

It also had a lizard-like body, perhaps up to 1.8m long (~6'), with rather long slender limbs and large blade-like claws, and more anatomical weirdness in the pelvic region convergently resembling those of distantly related groups like rhynchosaurs and tanystropheids. It had a sprawling posture, but its hind limb musculature suggests it might have been capable of getting up into a more erect stance when walking, somewhat similar to modern crocodilians' "high walk" gait.

It was clearly quite an ecologically specialized animal, but quite what it was specialized for is still uncertain. It was presumably a herbivore like its close relatives, but it must have been eating a very different diet with its long beak, and its deep claws could have been used for scratch digging to get at roots and tubers.

Another possibility it that it could have been an insectivore with a diet similar to modern aardvarks or armadillos, probing with its beak and digging with its claws for insects, grubs, and other invertebrates. Since termite-like social insect nests do seem to have existed around the same time, it might even have been one the earliest known animals to specialize in myrmecophagy.

———

Nix Illustration | Tumblr | Pillowfort | Twitter | Patreon

#weird heads 2020#science illustration#paleontology#paleoart#palaeoblr#teraterpeton#trilophosauridae#allokotosauria#archosauromorpha#reptile#art#wonderful creeping thing#excellent names

307 notes

·

View notes

Text

Round One: Match Twenty-Seven

Lystrosaurus

By @thewoodparable

Versus

By @stolpergeist

Teraterpeton

Click on the above links to refresh your memory about these animals! And feel free to use this post to debate and argue on what people should vote for!

The Official Tag for Triassic Madness is “#Triassic March Madness��! Be sure to look there for posts!

#Triassic Madness#Triassic March Madness#Triassic#Palaeoblr#TMM#Round One#Round One Match Twenty-Seven#Lystrosaurus#Teraterpeton

52 notes

·

View notes

Text

Why can't we get reptileevolution off of Google page 1 results? Anyone?!?

0 notes

Photo

Allokotosaurs were a group of mostly-herbivorous archosauromorph reptiles, distantly related to the ancestors of crocodiles, pterosaurs, and dinosaurs. They lived across Eurasia, Africa, and North America during the mid-to-late Triassic period, and their lineage included some weird and diverse forms – such as the bull-horned Shringasaurus, the long-beaked Teraterpeton, and possibly also the gliding kuehneosaurids.

Spinosuchus caseanus here was yet another one of these Triassic allokotosaurian weirdos, part of the trilophosaurid family and closely related to Trilophosaurus and Teraterpeton.

Living about 221-212 million years ago in what is now northwest Texas, USA, Spinosuchus was around 2.2m long (~7'2") and had distinctive elongated neural spines along the vertebrae of its back and the base of its tail, forming a "high back" or short "sail". Since it's only known from a partial spinal column the rest of its anatomy isn't known for certain, but it probably had body proportions similar to its close relative Trilophosaurus, with sprawling limbs and a short-snouted beaked head adapted for herbivory.

Like many other fossil "sailbacked" animals the exact function of Spinosuchus' elongated vertebrae is unclear, but the structure may have been used for visual display. I've depicted it here with a speculative frill of colorful elongated scales, along with a flashy dewlap.

———

Nix Illustration | Tumblr | Twitter | Patreon

#science illustration#paleontology#paleoart#palaeoblr#spinosuchus#trilophosauridae#allokotosauria#archosauromorpha#reptile#art history#sailback

212 notes

·

View notes

Text

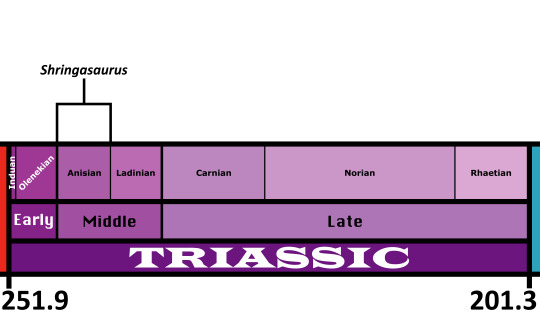

Shringasaurus indicus

By Stolp

Etymology: Horned Reptile

First Described By: Sengupta, Ezcurra & Bandyopadhyay, 2017

Classification: Biota, Archaea, Proteoarchaeota, Asgardarchaeota, Eukaryota, Neokaryota, Scotokaryota Opimoda, Podiata, Amorphea, Obazoa, Opisthokonta, Holozoa, Filozoa, Choanozoa, Animalia, Eumetazoa, Parahoxozoa, Bilateria, Nephrozoa, Deuterostomia, Chordata, Olfactores, Vertebrata, Craniata, Gnathostomata, Eugnathostomata, Osteichthyes, Sarcopterygii, Rhipidistia, Tetrapodomorpha, Eotetrapodiformes, Elpistostegalia, Stegocephalia, Tetrapoda, Reptiliomorpha, Amniota, Sauropsida, Eureptilia, Romeriida, Diapsida, Neodiapsida, Sauria, Archosauromorpha, Crocopoda, Allokotosauria, Azendohsauridae

Status: Extinct

Time and Place: Between 247.2 to 242 million years ago, in the Anisian of the Middle Triassic

Shringasaurus is known from the Denwa Formation in Madhya Pradesh, India

Physical Description: Shringasaurus is a very strange looking reptile (befitting of the allokotosaur title), and basically looks like one of those retro ‘slurpasaurs’ from those old dinosaur movies where they just glued horns onto an iguana. At around 3–4 metres long, Shringasaurus was pretty large for a Middle Triassic archosauromorph, and could have potentially stood tall enough to look you in the eye. Shringasaurus had some very unusual proportions, with a small blunt-snouted head on a long, very thick neck attached to some very deep shoulders with tall withers over them. These chunky forequarters contrast with its rear end, with proportionately small hips and a tail that is relatively short compared to other stem-archosaurs. Of course, its most famous features are its bizarre horns over its eyes. These are remarkably similar to the horns of ceratopsid dinosaurs like Triceratops, and are yet another fabulous example of the Triassic doing everything dinosaurs did first. These horns can be as tall as the skull again in large individuals, and curve to face up and forwards. These horns were proportionately smaller in younger animals, and so likely grew in as they matured. Interestingly, one juvenile specimen lacks horns at all, even though a similar sized specimen has them, suggesting that some Shringasaurus, possibly females, didn’t have them. Even on closer inspection Shringasaurus is weird. For instance, it has palatal teeth like some other reptiles, but lots of them, and they’re all shaped exactly like the teeth on the edges of its jaws. No other reptile besides it and its close relative Azendohsaurus have teeth like that. Just imagine how that would look when it opened its mouth.

Shringasaurus embodies the typical azendohsaurid body plan of combining bizarrely ‘advanced’ sauropod-like traits with those of more ‘primitive’ archosauromorphs. Its long neck and small head has obvious superficial similarities, but features of its jaws and teeth are so sauropod-like that they’re only seen in sauropods themselves and azendohsaurids like Shringasaurus—yet another remarkable example of convergent evolution in these animals. Features of its arms are similar to sauropodomorphs too, but its posture was decidedly more ‘primitive’ than them. Its back legs sprawled completely, like those of a lizard, and while the front legs weren’t anything as upright as sauropods, they may still have been held more off the ground in a sort of semi-sprawl than the back ones. This would have given Shringasaurus a sloped back and raised the head and neck higher above its shoulders, so in a way it was still superficially sauropod-like. With horns.

Diet: Shringasaurus was clearly a herbivore from the shape of its teeth, which are leaf-shaped and serrated (indistinguishable from herbivorous dinosaur teeth, infact). The teeth and jaws of its close relative of Azendohsaurus have been studied in detail, and suggest it preferred feeding on the softer parts of plants like leaves rather than tough stems and branches. Shringasaurus had similar teeth, so it likely fed on soft vegetation also. Quite how it used its freaky palatal teeth is anyone’s guess.

Behavior: Not much can be said for sure about its behaviour, but since so many Shringasaurus individuals were found together of different ages, it’s possible that they lived in mixed-aged herds. Sexual dimorphism, if really present, would be a good indicator that the horns were used at least for display, but like the horns of ceratopsids and living bovids it’s also possible they were used in combat, locking their horns in jousts to settle disputes over food, mates, territory, or anything else they might have been grumpy over. The shape of the horns in particular implies they were mostly likely used for this kind of wrestling.

Ecosystem: Shringasaurus co-existed with a decent variety of other typical mid-Triassic animals in the Denwa Formation. Other large herbivores included two dicynodonts, one a stahleckeriine and the other more like the older Kannemeyeria, as well as an early rhynchosaurid. No less than four temnospondyl amphibians are known from there, including the predatory Cherninia and Paracyclotosaurus crookshanki, a brachyopoid (think Koolasuchus), and a long-snouted gharial-like trematosaurid. The extinct lungfish Ceratodus was also swimming around here too. Shringasaurus was one of the largest animals known in this ecosystem, and probably would have only rubbed shoulders with the large stahleckeriine dicynodont for food sources, browsing on tall, lush plants out of reach of the other herbivores. The environment was a broad, semi-arid floodplain with slow meandering rivers, subject to seasonal rainfall and droughts that may have periodically dried up rivers and ponds.

Other: Shringasaurus belongs to a recently recognised group of archosauromorphs called Allokotosauria, the “strange reptiles”, which includes other peculiar stem-archosaurs like Trilophosaurus and bizarre Teraterpeton. Allokotosaurs all appear to be herbivores, and can be characterised by their strange teeth, but they’ve all got different types of them! Shringasaurus and other azendohsaurids all have jaws full of teeth (including the roof of the mouth) that look just like herbivorous dinosaur teeth. The resemblance is so uncanny that Azendohsaurus was considered to be a dinosaur for decades before the rest of its body was discovered. Trilophosaurids meanwhile have a characteristic beak, which in the unique case of Teraterpeton is so long and pointed that it vaguely resembles an anteater, and their teeth are cusped and interlocking for shearing leaves.

Early archosauromorphs used to be thought of as mostly carnivores and insectivores, while the role of large herbivores was dominated by the synapsid dicynodonts in the Early and Middle Triassic, with archosaurs like dinosaurs and aetosaurs, as well as the rhynchosaurs, only taking over in the Late Triassic. Allokotosaurs like Shringasaurus demonstrate that this was wrong, and that stem-archosaurs were just as capable of being derived herbivores capable of competing with synapsids in the Middle Triassic just as well as the later derived rhynchosaurs and archosaurs, including at large sizes as big as Shringasaurus. Intriguingly, there’s evidence to suggest that Azendohsaurus was endothermic to some degree, i.e. warm-blooded, and given their close relationship it’s probable that Shringasaurus was too. This would make azendohsaurids like Shringasaurus some of the earliest stem-archosaurs to have been warm-blooded!

~ By Scott Reid

Sources under the Cut

Bandyopadhyay, S. and Sengupta, D.P., 1999. Middle triassic vertebrates of India. Journal of African Earth Sciences, 29(1), pp.233-241

Cubo, J.; Jalil, N.-E. (2019). "Bone histology of Azendohsaurus laaroussii: Implications for the evolution of thermometabolism in Archosauromorpha". Paleobiology. 45 (2): 317–330

Ghosh, P., Sarkar, S. & Maulik, P. Sedimentology of a muddy alluvial deposit: Triassic Denwa Formation, India. Sedimentary Geology 191, 3–36 (2006)

Goswami, A.; Flynn, J.J.; Ranivoharimanana, L.; Wyss, A.R. (2005). "Dental microwear in Triassic amniotes: implications for paleoecology and masticatory mechanics". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 25 (2): 320–329

Maulik, P. K., Chakraborty, C., Ghosh, P. & Rudra, D. Meso- and Macro-Scale architecture of a Triassic Fluvial Succession: Denwa Formation, Satpura Gondwana Basin, Madhya Pradesh. Journal Geological Society of India 56, 489–504 (2000)

Mukherjee, R.N. and Sengupta, D.P., 1998. New capitosaurid amphibians from the Triassic Denwa Formation of the Satpura Gondwana basin, central India. Alcheringa, 22(4), pp.317-327

Mukherjee, D., Sengupta, D.P. and Rakshit, N., 2019. New biological insights into the Middle Triassic capitosaurs from India as deduced from limb bone anatomy and histology. Papers in Palaeontology

Nesbitt, S.J;, Flynn, J.J.; Pritchard, A.C.; Parrish, M.J.; Ranivoharimanana, L.; Wyss, A.R. (2015). "Postcranial osteology of Azendohsaurus madagaskarensis (?Middle to Upper Triassic, Isalo Group, Madagascar) and its systematic position among stem archosaur reptiles". Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History (398): 1–126

Robinson, P. L. 1970. The Indian Gondwana formations–a review. In First IUGS International Symposium on Gondwana Stratigraphy and Paleontology, 201–268

Sengupta, S.; Ezcurra, M.D.; Bandyopadhyay, S. (2017). "A new horned and long-necked herbivorous stem-archosaur from the Middle Triassic of India". Scientific Reports. 7: 8366

#Shringasaurus#Shringasaurus indicus#Reptile#Archosauromorph#Triassic#Triassic Madness#Triassic March Madness#Palaeoblr#Allokotosaur#Prehistoric Life#Paleontology#Prehistory

364 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sharovipteryx mirabilis

By @stolpergeist

Etymology: Sharov’s Wing

First Described By: Sharov, 1971

Classification: Biota, Archaea, Proteoarchaeota, Asgardarchaeota, Eukaryota, Neokaryota, Scotokaryota, Opimoda, Podiata, Amorphea, Obazoa, Opisthokonta, Holozoa, Filozoa, Choanozoa, Animalia, Eumetazoa, Parahoxozoa, Bilateria, Nephrozoa, Deuterostomia, Chordata, Olfactores, Vertebrata, Craniata, Gnathostomata, Eugnathostomata, Osteichthyes, Sarcopterygii, Rhipidistia, Tetrapodomorpha, Eotetrapodiformes, Elpistostegalia, Stegocephalia, Tetrapoda, Reptiliomorpha, Amniota, Sauropsida, Eureptilia, Romeriida, Diapsida, Neodiapsida, Sauria, Archosauromorpha, Protorosauria, Sharovipterygidae

Time and Place: 242 million years ago, in the Ladinian of the Middle Triassic

Sharovipteryx is known from the Madygen Formation of Kyrgyzstan

Physical Description: Ah Sharovipteryx. Are there many Triassic weirdos as iconic as this one? It was a weird, Archosauriform reptile, only about 25 centimeters long from snout to tail, and extremely thin - its tail is practically ephemeral, and its head is small and sharply pointed at the tip of the snout. Its body was also very skinny and almost flat, and it had short, skinny forelimbs. It’s hindlimbs were also skinny - and very, very, very long. The reason for this length is simple - the fossils show that there was a very long membrane of skin extending from the tips of the toes to the armpits, utilizing the legs as an anchor for this membrane. The skin of the hind-limbs may have been just a membrane, but Sharovipteryx did have scales like those of a lizard covering its entire body. The long and skinny tail seems to have lacked ornamentation altogether.

Diet: With small, sharp teeth, Sharovipteryx probably would have fed mainly on insects.

Behavior: Sharovipteryx was a glider, utilizing its hind limbs in a Delta-Wing formation, possibly one of the only animals - certainly one of the only known reptiles - to do so. The thin front limbs would have been like an aeronautic canard, helping the animal move with more agility in the air, and also would have been useful in steering. The tail could have been bent up and down to create drag, slowing down its movement from tree to tree. It couldn’t flap, but it wouldn’t need to, as its densely forested environment allowed it to move quickly by gliding from tree to tree and controlling pitch with its forelimbs. Sharovipteryx probably evolved from climbers, which used their ridiculous hind limbs to go up and down tree trunks; these little animals then leapt from tree to tree, and eventually developed gliding capability in the process. Sharovipteryx appears to have been relatively uncommon, so its possible it wasn’t very social; whether or not it would have taken care of its young is unknown. It probably used its small narrow head to grab food easily, though mostly it would have been decent streamlining for gliding (much like Delta-Wing Aircrafts like Viggens and Gripens).

By @stolpergeist

Ecosystem: As we’ve learned before, the Madygen was an extremely densely forested ecosystem, with thick coniferous trees packed around large lakes set in deep, clay-filled mud. This made it a very wet and green environment, without many large animals, but instead with many animals adapted for the trees and then well preserved in the extensive mud. Many different animals and insects have been preserved in this environment along with Sharovipteryx. Insects included the earliest Hymenopterans, Titanopterans like Gigatitan, moths, beetles, crickets, mosquitos, flies, grigs, and other weird insects with no modern analogues - plenty of food for Sharovipteryx. There were other vertebrates, too - sharks such as Fayolia, Lonchidion, and Palaeoxyris; ray-finned fish like Alvinia, Megaperleidus, Sixtelia, Ferganiscus, Oshia, and Saurichthys; the salamander-like Triassaurus; the primitive cynodont Madysaurus; the Drepanosaur Kyrgyzsaurus; and, of course, the great hockey-scale-creature Longisquama. Such a weird and fascinating slice of Triassic life!

Other: Sharovipteryx is classified as a Protorosaur - a group of Triassic Weirdos that are probably more closely related to Archosaurs than anything else that includes animals like the long-necked Tanystropheus, the reptile-monkeys like Drepanosaurus, and the Permian Archosauromorph (!!! big deal alert!!!) Protorosaurus. That said, this group is probably an artificial one, with these animals not actually grouped together to the exclusion of other Archosauromorphs. While relationships among the animals within the group clearly exist, it is uncertain how many of them are really grouped together. That said, weirdly enough, Tanystropheids and Sharovipteryigds do have a certain amount in common, so they might stay together yet. More study on the evolution of Archosauromorphs is, clearly, needed as we try to figure out the details of their relationships and where exactly Sharovipteryx and its cousin Ozimek go.

~ By Meig Dickson

Sources Under the Cut

Alifanov, V. R., and E. N. Kurochkin. 2011. Kyrgyzsaurus bukhanchenkoi gen. et sp. nov., a new reptile from the Triassic of southwestern Kyrgyzstan. Paleontological Journal 45(6):42-50.

Cowen, R. 1981. Homonyms of Podopteryx. Journal of Paleontology 55:483.

Dyke, G. J., Nudds, R. L. and Rayner, J. M. V. (2006). "Flight of Sharovipteryx mirabilis: the world's first delta-winged glider". Journal of Evolutionary Biology.

Dzik, Jerzy; Tomasz Sulej (2016). "An early Late Triassic long-necked reptile with a bony pectoral shield and gracile appendages". Acta Palaeontologica Polonica. 61 (4): 805–823.

Ezcurra, Martín D. (2016). "The phylogenetic relationships of basal archosauromorphs, with an emphasis on the systematics of proterosuchian archosauriforms". PeerJ. 4: e1778.

Fischer, J.; Voigt, S.; Schneider, J.W.; Buchwitz, M.; Voigt, S. (2011). "A selachian freshwater fauna from the Triassic of Kyrgyzstan and its implication for Mesozoic shark nurseries". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 31 (5): 937–953.

Gans, Carl; Darevski, Ilya; Tatarinov, Leonid P. (1987). "Sharovipteryx, a reptilian glider?". Paleobiology. 13 (4): 415–426.

Ivakhnenko, M. F. 1978. Tailed amphibians from the Triassic and Jurassic of Middle Asia. Paleontological Journal 1978(3):84-89.

Nesbitt, J., Sterling; 1955-, Flynn, John J. (John Joseph); 1987-, Pritchard, Adam C.; 1953-, Parrish, J. Michael; Lovasoa., Ranivoharimanana; R., Wyss, André (2015-12-07). "Postcranial osteology of Azendohsaurus madagaskarensis (?Middle to Upper Triassic, Isalo Group, Madagascar) and its systematic position among stem archosaur reptiles. (Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History, no. 398)".

Pritchard, Adam C.; Hans-Dieter Sues (2019). "Postcranial remains of Teraterpeton hrynewichorum (Reptilia: Archosauromorpha) and the mosaic evolution of the saurian postcranial skeleton". Journal of Systematic Palaeontology. 17 (20): 1745–1765.

Sharov, A. G. 1970. An unusual reptile from the Lower Triassic of Fergana. Paleontological Journal 1970(1):112-116.

Sharov, A. G. 1971. Novye letayushche reptilii is Mesosoya Kazachstana i Kirgizii [New Mesozoic flying reptiles from Kazakhstan and Kirgizia]. Trudy Paleontologicheskiya Instituta Akademiy Nauk SSSR 130:104-113.

SHCHERBAKOV, Dmitry (2008). "Madygen, Triassic Lagerstätte number one, before and after Sharov". Alavesia. 2 (5): 125–131.

Tatarinov, L. P. 2005. A new cynodont (Reptilia, Theriodontia) from the Madygen Formation (Triassic) of Fergana, Kyrgyzstan. Paleontological Journal 39:192-198.

Udurawane, Vasika. 2016. Sharovipteryx, the Triassic reptile with leg-wings. Earth Archives.

Unwin, D. M., V. R. Alifanov, and M. J. Benton. 2000. Enigmatic small reptiles from the Middle-Late Triassic of Kirgizstan. In M. J. Benton, M. A. Shishkin, D. M. Unwin, E. N. Kurochkin (eds.), The Age of Dinosaurs in Russia and Mongolia. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 177-186

#sharovipteryx#sharovipterygid#archosauromorph#diapsid#triassic#triassic madness#triassic march madness#prehistoric life#paleontology

239 notes

·

View notes

Text

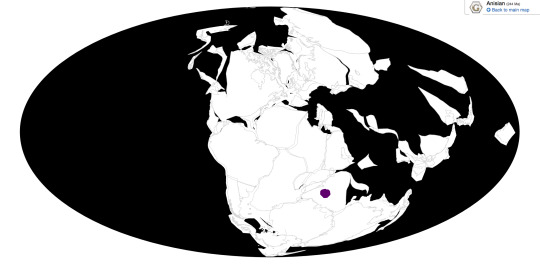

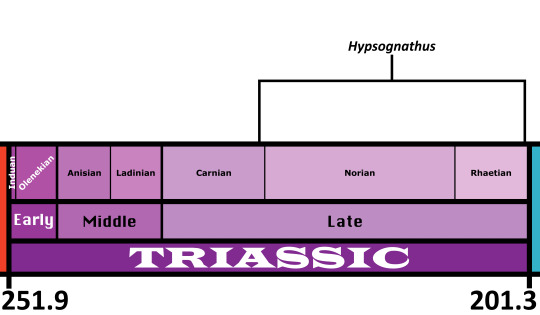

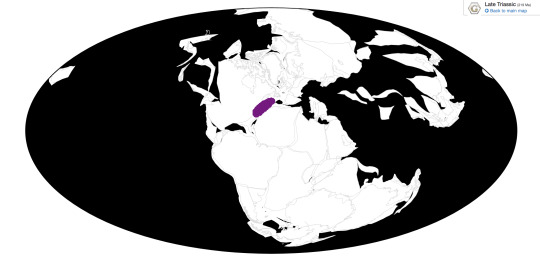

Hypsognathus fenneri

By Ashley Patch

Etymology: High Jaw

First Described By: Gilmore, 1928

Classification: Biota, Archaea, Proteoarchaeota, Asgardarchaeota, Eukaryota, Neokaryota, Scotokaryota, Opimoda, Podiata, Amorphea, Obazoa, Opisthokonta, Holozoa, Filozoa, Choanozoa, Animalia, Eumetazoa, Parahoxozoa, Bilateria, Nephrozoa, Deuterostomia, Chordata, Olfactores, Vertebrata, Craniata, Gnathostomata, Eugnathostomata, Osteichthyes, Sarcopterygii, Rhipidistia, Tetrapodomorpha, Eotetrapodiformes, Elpistostegalia, Stegocephalia, Tetrapoda, Reptiliomorpha, Amniota, Sauropsida, Diapsida?, Parareptillia, Procolophonomorpha, Ankyramorpha, Procolophonia, Procolophonoidea, Procolophonidae, Leptopleuroninae, Leptopleuronini

Time and Place: Between 228 and 202 million years ago, from the Carnian to the Rhaetian of the Late Triassic

Hypsognathus is known from a wide variety of formations, including the Wolfville and Blomidon Formations of Nova Scotia, the New Haven Formation of Connecticut, and the Passaic Formation of New Jersey.

Physical Description: Hypsognathus was a Parareptile, a group of odd creatures much more common in the Permian but had their last hurrah during the Triassic. These animals were some of the most varied and fascinating creatures of their time, including some of the first bipeds, first megafauna, and first aquatic reptiles. In the Triassic, most looked like your generic tetrapod - lizards, except without their specializations and long tails; salamanders but with scales. Some, however, kept doing weird things, including our friend Hypsognathus here. Hypsognathus was about 33 centimeters long, with stocky limbs and a thick trunk. Its head was almost half as wide as the body was long at 12.5 centimeters, and it wasn’t very mobile (or kinetic) - instead, fixed in place for extra support and sturdiness. Notably, Hypsognathus had extensive spikes and protrusions coming off of its head to the sides and down on the face, making it look rather monstrous from the front. These spikes may have even been longer than the fossil indicates, covered by keratin for display purposes. Its jaw was curved upwards, giving it a weird sort of permanent smile, and it had giant teeth protruding from its mouth. These teeth were blunt and thick, allowing for strong mashing of food. These teeth were also fascinating because there was clear tooth replacement, usually alternating - in the sequence of ABABABAB, the A’s would get replaced, and then the B’s. The rest of its body was fairly standard for a Procolophonid - with short, splayed out legs for walking slowly and from side to side; wide and thick fingers and toes for gripping the ground; and a short stubby tail not used for much at all. It would have probably been covered in something akin to scales, and well adapted for dry conditions as a result.

Diet: Hypsognathus was an herbivore, feeding on high-fiber, tough plant material.

Behavior: Hypsognathus was, more likely than not, a burrowing animal. The lack of kinesis in the skull allowed it to use it like a shovel, which may have been one of the uses of the spikes on its face. It could then dig into the ground to hide from predators, burrowing deep and not worrying about the fact that the rest of its body is relatively unprotected since it is being hidden by the dirt. This also explains the lack of ornamentation elsewhere on the body, and its squat and short structure. A long tail, or long limbs, would not have aided in hiding in the dirt! In addition, those wide and thick fingers and toes would have helped in kicking up dirt and escaping from predators quickly. The spikes may have also been able to anchor Hypsognathus within the burrow itself, preventing it from being dug out by a small predator. These spikes would have also been decent as display structures, with longer or more ridiculous looking ones appearing Fancy to other Hypsognathus. This could have been added on to with more keratin sheaths, reflecting the ability of an individual Hypsognathus to waste energy - and burrow space - on more elaborate horns because it was doing so well. It would then emerge from the burrows to feed on roughage and tough plants - though it may have been able to feed on roots and tubers underground as well. Given it could have used the horns for display, it was probably at least somewhat social; however, we have no idea how much or if it took care of its young, or had any other complex behaviors. Juvenile and young specimens are known, and they also have spikes, so if they served for communication, social life may have been a part of youth as well as adulthood.

Ecosystem: Hypsognathus was a consistent feature of Northeastern North America during the Late Triassic, present in a variety of environments and ecosystems along the geologically active area that would eventually open up to begin forming the Atlantic Ocean. It generally favored sandy beaches lining seasonal lakes and rivers, with a variety of coniferous trees and swamp trees rooted in the lake. There were also ferns, cycads, and plankton abundant around and within the water. There were also proto angiosperms! While Hypsognathus lived with a wide variety of animals, some creatures kept popping up over and over again - the Aetosaur Stegomus, Phytosaurs such as Belodon and Rutiodon, Rhynchosaurs like Scaphonyx and Colobops, predatory Pseudosuchians such as Erpetosuchus and Rauisuchians, the weirdo Tanystropheid Gwyneddichnium and the Allokotosaur Teraterpeton, other Procolophonids like Scoloparia and Acadiella, the Temnospondyl Metoposaurus, the Cynodont Arctotraversodon, and there were also early dinosaurs and late Dicynodonts (though only footprints were preserved). In fact, Hypsognathus is most commonly preserved alongside footprints, lending credence to the idea that it would burrow in wet, sandy places, and get trapped and preserved there in the same events that preserved the prints.

Other: This strange burrower with a spikey head was a very successful animal - it was found all over Eastern North America, throughout the Late Triassic, and seems to have only gone extinct because of the end-Triassic extinction. This is notable, because it is one of the last surviving Parareptiles, ever. The other Parareptiles of the Triassic were also small, squat lizard-like burrowers, many with interesting head ornamentation as well. While the heyday of Parareptiles was behind them, they managed to put on an excellent (and adorable) final act. In fact, morphological diversity of Parareptiles went down from a wide variety of shapes and forms and lifestyles to just one, the Procolophonids like Hypsognathus. This makes Hypsognathus a unique example of an ancient lineage, survivors of one Mass Extinction just to be finished off by another.

~ By Meig Dickson

Sources Under the Cut

Carroll, R. L., E. S. Belt, D. L. Dineley, D. Baird, and D. C. McGregor. 1972. In D. J. Glass (ed.), Guidebook: Excursion A59. Vertebrate Palaeontology of Eastern Canada 1-113.

Colbert, E. H. 1946. Hypsognathus, a Triassic reptile from New Jersey. Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History 86: 225 - 274.

Ford, D. P., R. B. J. Benson. 2020. The phylogeny of early amniotes and the affinities of Parareptilia and varanopidae. Nature Ecology & Evolution 4: 57 - 65.

Gilmore, C. W. 1928. New Fossil Reptile from the Triassic of New Jersey. Proceedings of the United States National Museum 73(7):1-8.

Lucas, S. G. 2018. Late Triassic Terrestrial Tetrapods: Biostratigraphy, Biochronology, and Biotic Events. The Late Triassic World, Topics in Geobiology 46: 351 - 405.

Macdougall, M. J.; D. Scott, S. P. Modesto, S. A. Williams, R. R. Reisz. 2017. New material of the reptile Colobomycter pholeter (Parareptilia: Lanthanosuchoidea) and the diversity of reptiles during the Early Permian (Cisuralian). Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society 20: 1 - 11.

MacDougall, M. J.; N. Brocklehurst, J. Frobisch. 2019. Species richness and disparity of pararpetiles across the end-Permian Mass Extinction. Proceedings of the Royal Society B 286: 2018572.

Olsen, P. E., and D. Baird. 1986. The ichnogenus Atreipus and its significance for Triassic biostratigraphy. In: K. Padian (ed.), The Beginning of the Age of Dinosaurs: Faunal Changes Across the Triassic-Jurassic Boundary. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 61-87.

Olson, P. E. 1988. Paleoecology and Paleoenvironments of the Continental Early Mesozoic Newark Supergroup of Eastern North America: In Manspeizer, W. (ed.), Triassic-Jurassic Rifting and the Opening of the Atlantic Ocean, Elsevier, Amsterdam, p. 185-230.

Palmer, D. 1999. The Marshall Illustrated Encyclopedia of Dinosaurs and Prehistoric Animals. London: Marshall Editions.

Sues, H. D., P. E. Olsen, D. M. Scott, P. S. Spencer. 2000. Cranial Osteology of Hypsognathus fenneri, a latest Triassic procolophonid reptile from the Newark Supergroup of Eastern North America. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 20 (2): 275 - 284.

Sues, H.D. 2019. The Rise of Reptiles: 320 Million Years of Evolution. JHU Press.

Tsuji, L. A. 2017. Mandaphon nadra, gen. Et sp. Nov., a new procolophonid from the Manda Beds of Tanzania. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 37 (supp1): 80 -87.

Zaher, M., R. A. Coram, M. J. Benton. 2018. The Middle Triassic procolophonid Kapes bentoni: computed tomography of the skull and skeleton. Papers in Palaeontology 5 (1): 111 - 138.

#hypsognathus#parareptile#procolophonid#triassic#triassic madness#triassic march madness#prehistoric life#paleontology

113 notes

·

View notes