#teixidor

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Paintings by Josefa Teixidor, also known as Pepita Teixidor (1875-1914). Museu Nacional d'Art de Catalunya.

Josefa Teixidor is considered the best flower painter in the Catalan Modernist movement, an art movement where flowers and nature were very present. She was celebrated during her life, and she was chosen as one of the three artist who would represent Catalonia in the Universal Exhibition held in Paris in 1900, together with Ramon Casas and Santiago Rusiñol.

Despite the recognition of her work, at the time women weren't usually allowed to exhibit their work in art galleries. Josefa Teixidor, together with other Catalan women artists of the time like Lluïsa Vidal, Visitación Ubach, Antònia Farreras, and Maria Lluïsa Güell, fought for the right of women to exhibit their art in Barcelona. Her success allowed her to exhibit her work here and also in France. She was also involved in the Catalan feminist magazine Feminal, that gave support to and published about the work of women artists, scientists and industrials.

She was awarded both in Catalonia and in France. Soon after her early death at 39 years old, she became the first woman who was neither a saint nor a queen to have a statue dedicated to her in Barcelona, Catalonia's capital city. (Even nowadays, Barcelona only has 14 statues of women who aren't saints nor queens, and that is including fictional characters. For comparison, Barcelona has at least 168 statues of real men in that category).

Inauguration of Josefa Teixidor's bust in Barcelona's Parc de la Ciutadella public park. 1917. Catalonia National Archive.

Bust to Pepita Teixidor nowadays.

Sadly, most of her work is owned by private collectors, only the three paintings included in this post are owned by a museum (MNAC). However, MNAC owns a huge collection and exhibits only a fraction of it, and none of Josefa Teixidor's works are displayed.

While making this post, it was difficult to find images of her work in good quality, because for some reason MNAC didn't have her works uploaded to their online catalogue. I sent them a message about it, and they answered the next day with the three works uploaded on their website (many things can be achieved by complain at the right people!). I hope making these paintings publicly available, together with this post, will make Josefa Teixidor more present in our minds. Sadly, she has been forgotten by most of society, while her male contemporaries like Rusiñol and Casas are still among the most famous artists of all times in our country. When we think of Modernist painters, from now on I hope we also think of Josefa Teixidor.

#pepita teixidor#josefa teixidor#arts#pintura#història#barcelona#catalunya#catalonia#coses de la terra#museums#flowers#watercolor#women in art#women in history#women painters#watercolor art#modernisme#history#feminism

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

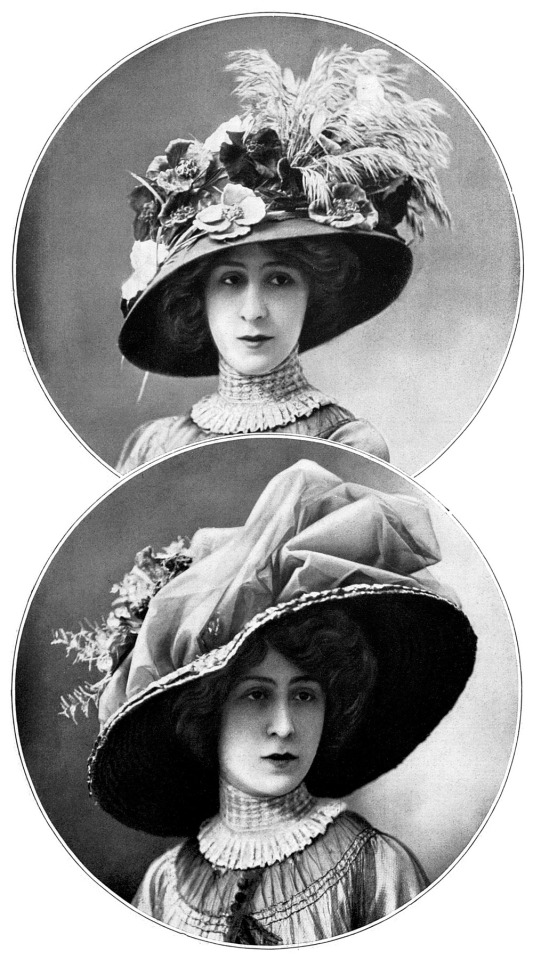

1910 Was a Big Year for Hats -

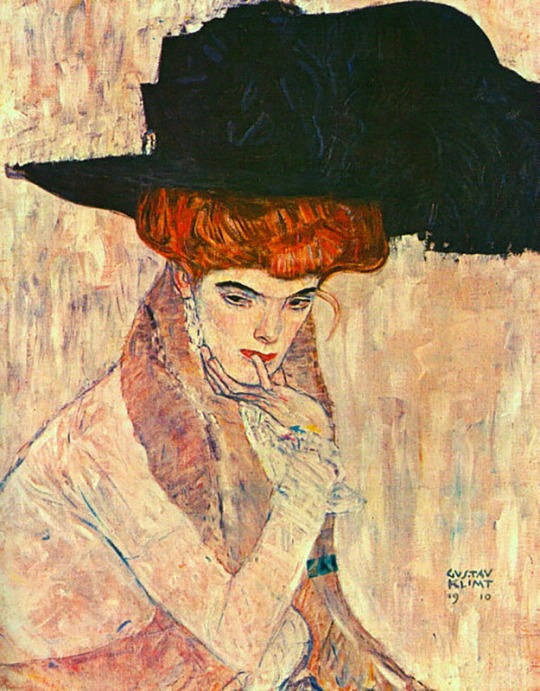

1910 The Black Feather Hat by Gustavv Klimt (location ?). From tumblr.com/lonequixote/128857458717/gustav-klimt-the-black-feather-hat 625X800.

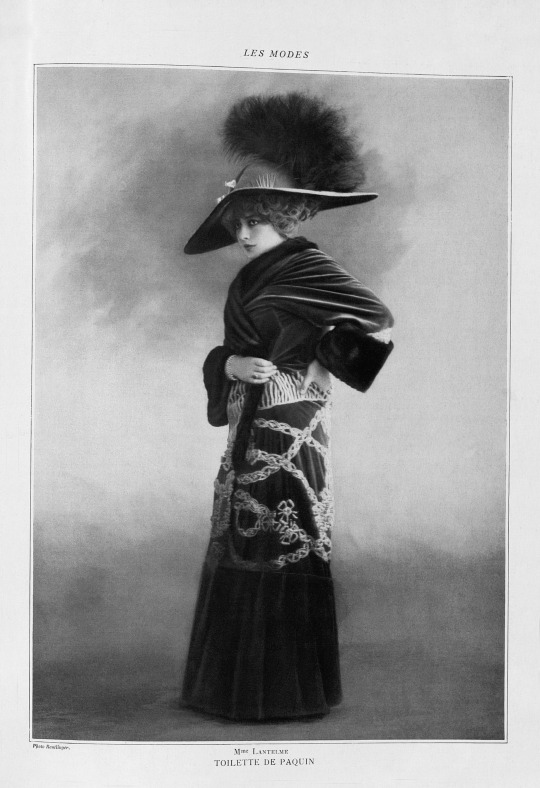

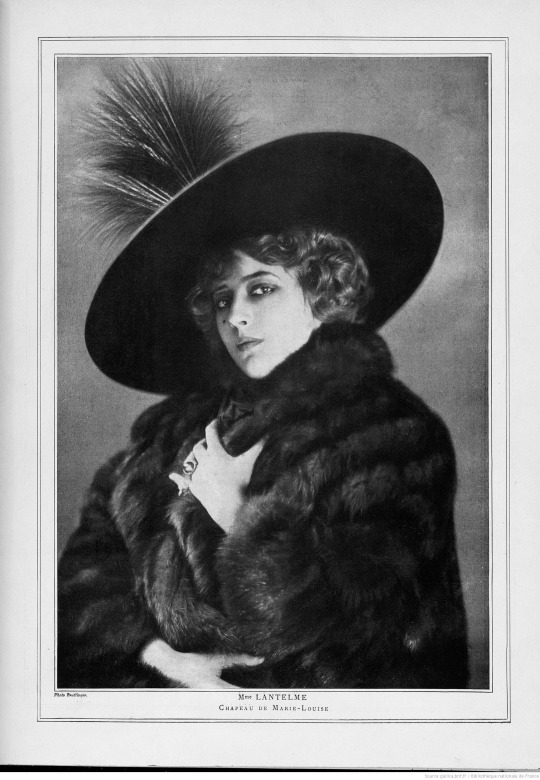

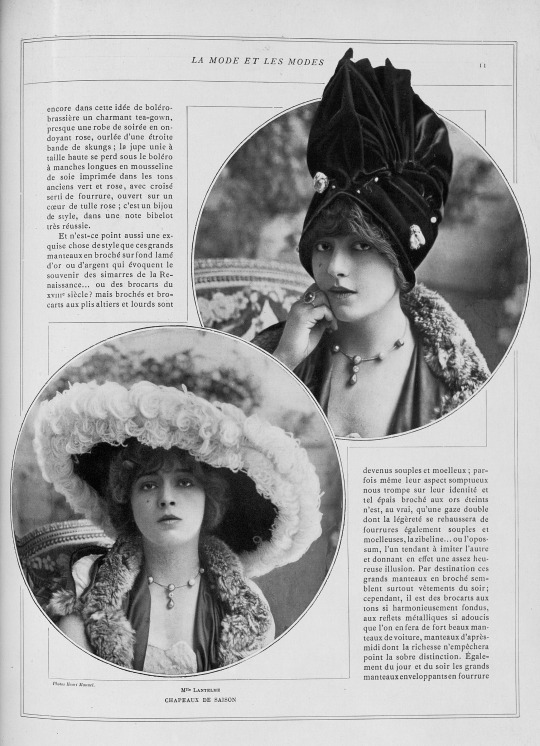

According to Wikipedia, "Geneviève Lantelme (born Mathilde Hortense Claire Fossey, 20 May 1883 – 24/25 July 1911) was a French stage actress, socialite, fashion icon, and courtesan. Considered by her contemporaries to be one of the most beautiful women of the Belle Epoque..." She posed wearing the spectacular hats of the time.

Left 1910 (December) Lantelme in wide hat and Paquin dress photo by Reutlinger Les Modes. From verbinina.wordpress.com/page/8/; fixed spots w Pshop 1844X2691.

Right 1910 (January) Lantelme in hat by Marie-Louise Les Modes. From verbinina.wordpress.com/page/8/ 2048X2959.

1910 (July) Lantelme in hat by Carlier photo by Félix Les Modes. From verbinina.wordpress.com/page/8/; fixed spots w Pshop 1354X1458.

1910 (November) Lantelme modeling hats. From verbinina.files.wordpress.com/2011/06/lantelme-nov1910-2 2048X2828.

1910 (November) Lantelme modeling high hat. From verbinina.files.wordpress.com/2011/06/lantelme-nov1910-2 1295X1638.

Left 1910 (May) Les Modes Hats by Maison Dalnys. From les-modes.tumblr.com/search/1910s/page/13 1000X1802.

Right 1910 (August) Les Modes Hat by Alphonsine. From les-modes.tumblr.com/search/1910s/page/2; fixed spots w Pshop 1280X1800.

Left 1910 (May) Walking ensemble by Bernerd, Les Modes - photo by Félix. From les-modes.tumblr.com/page/13; fixed spots w Pshop 761X1920. This is a very subdued hat for 1910.

Right 1910 (October) Dresses and hats by Jeanne Lanvin, Les Modes - photo by Paul Nadar. From les-modes.tumblr.com/page/15; fixed spots w Pshop 1280X1804. Very subdued for the day.

Left 1910 Feathered hats at the races. From les-modes.tumblr.com/post/146935641890/fashion-at-the-races-les-modes-july-1910-photo; fixed spots w Pshop 755X1630.

Right 1910 Hat and parasol. From les-modes.tumblr.com/post/146935641890/fashion-at-the-races-les-modes-july-1910-photo; fixed spots w Pshop 750X1624.

1910 Pepita Teixidor Drawing by Ramon Casas (location ?). From titturasculturapoesiamusica.com/2014/08/Ramon-Casas-Carbo.html 1228X1600.

1910 The Blue Hat by Kees Van Dongen (private collection). From the discontinued Athenaeum Web site 841X1024.

#1910s fashion#1910 fashion#Belle Époque fashion#Edwardian fashion#feathered hats#wide hats#Gustavv Klimt#Geneviève Lantelme#Jeanne Paquin#Reutlinger#Marie Louise#Carlier#Maison Dalnys#Alphonsine#high feathered hat#Augusta Bernard#Les Modes magazine#Pepita Teixidor#Ramon Casas#Kees Van Dongen#Drecoll

27 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Su ogni filo del telegrafo è appesa una piccola stella: un globo di neve.

In ogni atomo del cuore aleggia una bambolina: la noia.

Solo la neve immacolata ce ne libera momentaneamente.

Joan Teixidor, Febbraio, da Poesie, 1932

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

La Selva de Leones, XXIII. La vuelta al mundo de la hormiga Miga de Emili Teixidor. (De 6 a 11 años)

A la leona Patata Peluda le está encantando una superheroína que ha descubierto. Tiene menos pretensiones que los de Marvel pero es más divertida y sin duda sus aventuras son más variadas: ¡la Hormiga Miga! Así que este segundo libro se lo contó a su amiga el león Patata Pistacho y ¡ha venido hoy a charlar! Y eso, que nos han contado de sus viajes por Japón, China, Australia y como llegó a estos…

View On WordPress

#10 años#11 años#6 años#7 años#8 años#9 años#Barco de Vapor#comic#Emili Teixidor#La hormiga Miga#La vuelta al mundo#León Científico Bigotón#León Patata Peluda#León Patata Pistacho#lectura infantil#Leona Salchicha#podcast

0 notes

Note

was mithra/mithras worshipped in mesopotamia like was his worship introduced into this area during the achaemenid and later periods? what about cities near mesopotamia like Palmyra and dura europos? also was he syncrestised With any local gods? maybe shamash

I’m sorry but due to space constraints and lack of sufficient familiarity with (or deeper interest in) most Roman mystery cults I can’t help much with the dissemination of Mithras and Mithraism on the eastern periphery. There is no evidence of his cult being present in Palmyra (Javier Teixidor, The pantheon of Palmyra, p. 106) but on the other hand it was definitely present in Dura Europos (the mithraeum discovered there is notable enough to have its own wiki page, apparently); I’m not really aware of any attestations from even further east. According to Encyclopedia Iranica, “though represented virtually everywhere in the Roman empire, it was much stronger in the Latin speaking West than in the (predominantly) Greek-speaking East”. As for Mithra proper: the oldest datable attestation of him - or a derivative, at least, since we are dealing with a highly divergent oddity with a plural name, it seems - is technically at least Mesopotamia-adjacent.

The treaty between Suppiluliuma of the Hittite Empire and Šattiwaza of Mittani (c. 1330 BCE) lists “the Mitra-gods (d.MEŠMitraššil; the determinative signifies plurality), the Varuna-gods, Indra, the Nasatya-gods” (translation courtesy of Gary Beckman, Hittite Diplomatic Texts, p. 43) among deities invoked as witnesses on the Mittani side. As stressed most recently by Eva von Dassow in Mittani and Its Empire (published in The Oxford History of the Ancient Near East), their position is not prominent, and they do not appear anywhere else. People who try to make this attestation into a big deal are basically automatically untrustworthy. The Mitanni rulers, regardless of their origin, were culturally Hurrianized to such a degree the presence of some derivative of Mithra in a single treaty is borderline irrelevant - and it might not even be strictly speaking Mithra, but rather generic “treaty gods” (hence the plural). I’m not really aware of any Achaemenid, Arsacid or Sasanian efforts to introduce the strictly Zoroastrian version of Mithra to Mesopotamia.

Whether it’s possible to speak of any connection between Mithra and Shamash is a complex matter so that’s addressed under the cut. The material from Hatra pertains to that so it’s covered there too.

To begin with, I’m not aware of any clear case of identification between Mithra and Shamash. It’s a suggestion which sometimes pops up in scholarship, but without any conclusive evidence, as far as I am aware. It’s not entirely implausible, though.

Typically the comparisons depend on sharing both judiciary and solar roles, but it needs to be stressed here that Mithra didn’t really have strong solar associations until relatively late. This aspect of his character is absent from the Avesta, and according to his article in Encyclopedia Iranica there’s no clear evidence for him having a solar role predating Strabo’s account of Persian beliefs. Therefore, it probably only developed at some point in the Achaemenid period.

One relatively recent example of seeking possible connections between Mithra and Shamash I’ve stumbled upon is the article Mesopotamian Influence on Persian Sky-watching and Calendar. Part I. Mithra, Shamash and Solar Festivals by Krzysztof Jakubiak and Arkadiusz Sołtysiak (accessible via De Gruyter). Some quite bold claims are made there, with the supposed influence going all the way back to the Bronze Age. However, the authors provide basically no archeological evidence for early Iranian-Mesopotamian contact (they also don’t address the fact early Iranians would very obviously encounter Elamites first when moving westwards); and some of their sources indicate that a thorough survey of literature wasn’t made (in many cases outdated generalist publications are the only sources consulted). I’m reluctant to recommend it as a point of reference for this reason. It seems much more sound to seek possible influence in the Achaemenid period or beyond. However, matters are complicated by the fact that Mithra is essentially absent from some of the earliest available sources like the Persepolis fortification archives, and largely just appears in theophoric names before the reign of Artaxerxes II.

Margaret Cool Root suggests in Defining the Divine in Achaemenid Persian Kingship (published in Every Inch a King – Comparative Studies on Kings and Kingship in the Ancient and Medieval Worlds, accessible via Brill) that there is already evidence for Persians being familiar with the iconography of Shamash and his association with royal power and legitimacy during the reign of Darius I. However, she doesn’t propose any connection with Mithra, only with the semi-divine king and Ahura Mazda, and relies just on motifs in monumental art. More sound evidence is available from the early centuries CE. Michael Shenkar (Intangible Spirits and Graven Images, p. 102) notes a figure on the relief from Tang-e Sarvak might be either Mithra depicted in a similar manner to Shamash or just outright Shamash. He also proposes that an unusual depiction of the Kushan emperor Vima Kadphises rising from between mountains with rays/flames emanating from his shoulders is patterned on Shamash’s iconography (Royal regalia and 'Divine Kingship' in the pre-Islamic Central Asia, p. 58) and that Iranian and adjacent groups might have associated the images of Shamash rising from between mountains with the customary description of Mithra as responsible for surveying the world from atop Mount Harā. He points out Shamash was still depicted this way in the second century CE, as indicated by works of art from Hatra. I personally found these arguments convincing at least in terms of iconography. The situation in Hatra is somewhat unique, and requires some additional explanations, though.

A good recent outline can be found in Aleksandra Kubiak-Schneider’s Hatra of Shamash. How to assign the city under the divine power? (there is a small mistake on p. 799 though - referring to Ereshkigal as a sister of Shamash is a questionable syllogism at best, and even her sibling credentials wrt Inanna are questionable as recently stressed by Alhena Gadotti). She argues the city god, Maran/Maren, was essentially a derivative of Shamash - or Shamash under an Aramaic title, something like “our lord”. Some of his local features are unique - for example, his symbol was an eagle, but Shamash was never associated with this bird elsewhere in earlier periods (it was mostly Zababa’s thing). Kuciak-Schneider suggests this might be an evolution of depicting him symbolically as a winged solar disk (p. 798). A slightly different view can be found in an earlier publication. Ted Kaizer in his 2000 overview article Some remarks about the religious life of Hatra states that it cannot be determined with certainty if the Shamash worshiped in Hatra was derived from the Mesopotamian god, or instead from the Arabic sun goddess (p. 234). He also the local pantheon combined “Mesopotamian, Arab, Syrian and Graeco-Roman elements” (p. 230) - but not Iranian. This obviously requires partial revision, since Lucinda Dirven in her fantastic My Lord with his Dogs. Continuity and Change in the Cult of Nergal in Parthian Mesopotamia does demonstrate at least a degree of Iranian influence on the worship of Nergal in Hatra. However, all I dug up in the case of Mithra is a handful of Iranian theophoric names listed by Enrico Marcato in Personal Names in the Aramaic Inscriptions of Hatra: Daosha-Mithra (“Mithra is my friend”), Mithra, Mithra-bandag (“servant of Mithra”) and Mithra-dāta (“given by Mithra”). It doesn’t seem these have any deeper implications than that there were some people with an Iranian background in Hatra, though. Marcato states that the presence of an actual cult of Mithra in Hatra is implausible (p. 167) and has been already disproven in the 1970s by Han J. W. Drijvers in the article Mithra at Hatra? Some remarks on the problem of the Irano- Mesopotamian syncretism, which I tragically failed to find online. For what it’s worth, he also notes some of the same theophoric names occur in material from Palmyra as well.

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

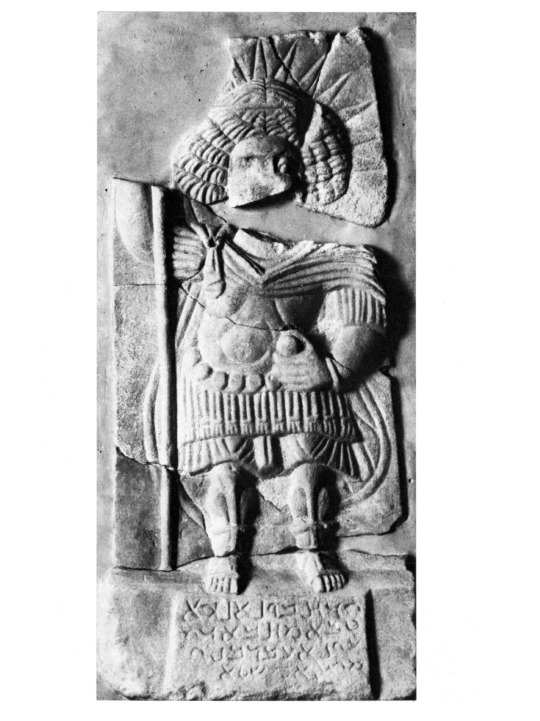

Yarhibol, the Sun-God Dura-Europos, Syria c. 50 CE Source: The Pantheon of Palmyra by Javier Teixidor, 1979

#yarhibol#dura europos#canaanite paganism#canaanite polytheism#canaanite gods#levantine paganism#phoenician#phoenician paganism#phoenician polytheism#phoenician gods#syrian paganism#syrian polytheism#syrian gods#natib qadish#pagan#paganblr#paganism#polytheism#witchcraft#witchblr#magic#occult

83 notes

·

View notes

Text

------------Pfizer---> Rezifp-----------

Reshef (a destra) raffigurato sulla stele di Qadesh.

Il termine è presente come etimo in lingua ebraica con il significato di "fiamma, fulmine" (Salmi 78:48), da cui derivano significati figurativi, come "freccia" (Libro di Giobbe 5:7) e "febbre che infiamma" (Deuteronomio 32:24)

Per la sua capacità di controllare e scatenare malattie e pestilenze, presso i greci venne accostato ad Apollo ed al vedico Rudra, mentre le caratteristiche marziali e belligeranti di Reshef ne hanno spesso favorito l'occasionale paragone con le figure di Marte e del dio babilonese della morte Nergal. I fenici si riferirono a lui come Resheph Gen (‘Reshep del Giardino’) e Baal Chtz (‘Signore delle frecce’), mentre gli ittiti lo hanno descritto come il dio cervo o il dio gazzella. A Larnaca, Cipro, Reshef aveva l'epitteto di ḥṣ, inteso come "arco" da Javier Teixidor, che, di conseguenza, interpretava Resheph come dio delle malattie, comparabile ad Apollo, le cui frecce portarono la peste contro gli Achei (Iliade I.42-55). Reshef compare anche in testi mitologici ugaritici come il poema epico di Kirta.

il testo di un'antica formula apotropaica invoca il nome di Reshef, insieme a quello di Astarte, come rimedio all'azione del demone cui si attribuiva la causa dei dolori addominali. Nel suo duplice aspetto di divinità guerriera e guaritrice, capace di coniugare in sé le opposte polarità di vita e morte, Reshef era conosciuto in Egitto e nel vicino Oriente.

-----

scateniamo l'immaginazione...;-)

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

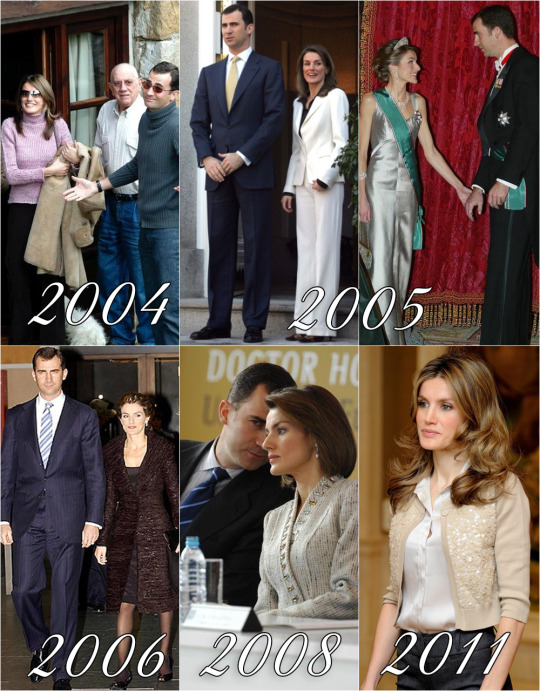

Felipe and Letizia retrospective: January 31st

2004: Visit to Letizia’s paternal grandparents in Sardeu, Asturias (1, 2)

2005: Lunch & Gala dinner offered to the president of Hungary, Ferenc Madl, and his wife.

2006: Celebration of the 100th anniversary of “Mundo Deportivo”

2008: Investiture of professors D. Valentín Fuster Carulla, D. Joan Rodés Teixidor and D. Pedro Alonso as Doctors Honoris Causa

2011: Audiences at la Zarzuela

2013: Inauguration of the new corporate headquarters of the company REPSOL

2017: 19th CODESPA Awards

2018: Diplomatic Corps Gala.

2019: 20th CODESPA Awards & Ibedrola Foundation Scholarships

2020: Received the female Waterpolo National Team (European Champions) and the male Waterpolo National Team (European Silver) at la Zarzuela & Meeting with the delegate comission of the Princess of Girona Foundation

2022: Inaugurated the “Dali-Freud” exhibition at the Unteres Belvedere Museum in Vienna, Austria.

2023: Inaugurated the Integrated Systems Europe (ISE) 2023 and the IOT Solutions World Congress (IOTSWC); Meeting of the Network of Direct Care Centers and Specialized Services of the Spanish Federation of Rare Diseases (FEDER) & Graduation of the 71th class of the Judicial Career and the 22nd class of the fourth rotation

F&L Through the Years: 1124/??

#King Felipe#Queen Letizia#King Felipe of Spain#Queen Letizia of Spain#King Felipe VI#King Felipe VI of Spain#F&L Through the Years#January31

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

HRNDZ, Madrid, 18 de noviembre de 2023 (sala Rockville).

HRNDZ es el proyecto del guitarrista Rafael Hernández (La Frontera, Desperados).

Y en este grupo de rock que ha formado se han reunido Juanma del Olmo y Emilio Galiacho (Elegantes), Dani Álvarez (Burning), Javier Teixidor (Mermelada, J. Teixi Band), Luis Martín (Los Ronaldos) y el productor, músico y escritor José Gallardo.

(Fotografías cedidas por Tina Jara).

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

17a Fira de Nadal de Banyoles i Mostra d'Oficis - Banyoles

0Dies 14 i 15 de desembre del 2024 a Banyoles (Pla de l’Estany) El segon cap de setmana de desembre l’Ajuntament de Banyoles organitza aquesta fira, en la qual col·labora l’associació, on es poden veure treballar els artesans de diversos oficis tradicionals: filadores, tenyidores, terrissaires, marroquiners, teixidors, escultors de fusta i alabastre, sarronaires i matalassers, sabaters,…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

aeroplanos, andreus (Ginebrosa), avions (de bassa) o avionets), barratgina/barretgina (Sóller/València), borinots, (cavalls de) bruixes, bumberots, burumbots, bombots, pixamines, cabots (Libellula depressa), cabuts, calabruixes, cavalls (de serp/de bruixa/d'aigua/), cavalles, cavall(et)s de Sant Martí, cavallets (del diable/dimoni), cavallets (de séquia/(cua) de serp/d'acer/de mar), cavallets voladors, cevils/civils, cuc de les basses, cucs plovedors, cuques voladores, damisel·les, diablets (Ondara), dianxos (a Gata), dimonis de safareig, dimoseles (Rosselló, Vallespir, Cerdanya) i madimoseles (Rosselló), doctors, dotors de bassa, escanyapits ((Fontpedrosa), escopetes, espantadimonis, espantacriatures, espiadimonis, espietes, esquitxidors, estiracabells, ferrers, fideues, gaiter(o)s, gambosins, gavatxos, gitanos, grandaios, guàrdies civils (Delta de l'Ebre), guitarretes, guitarrons, gulles, helicòpters, iaios (la Sénia), iaios figues (Mas de Barberans, Montsià), joanets, jolibeus/julibeus (a Pedreguer), judios, leonors, llagostins, mares de cavall, marianets, marietes, marotets (femella), marotetes (femella), médicos, micalets, mongetes (La Marina de Pinet), mor-te-i-fuigs/mortefuigs (Almenar), palometes, paraguais, paraigüer(o)s, pardals d'aigua (auia), pardalets d'estiu, parecabots (o parecabotes), pares vicaris, parits, parots (anisòpters: parots = èsnids i parotets = libel·lúlids), parots de bassa, parotets (mascle), passabarrancs (emprat potser a tort, puix que designa, també, els Cordulegaster) pericos, petins, pixatinters, pixavins (a Nules o Castelló), redolins (Delta de l'Ebre), reiets, relicari(o)s, remiqueris, rodabasses, rodadits (rodadit en singular. rodadits de bassa: Gomphus pulchellus, rodadits groc: Gomphus simillimus, rodadits esperonat: Gomphus graslinii), rodalitxos, rodapous, sangradors, sardineros (els Valentins, Montsià), sastres, senyores, senyoretes, serpents, serradits (en singular), tavals, tavans (d'aigua), tavanos, capellans, sangradors, tallanàs o tallanassos (invariable) (Alcanar), tallaorelles, teixidors, tixeires (Sallagosa), torerets (zigòpters), trencaporrons (en singular), treu-ulls, trisparís (Castelló), volantins de fontana, vicaris de bassa, voliaines (Targasona), voltabaixos, voltabasses (Alt Penedès), voltapous, xopaculs... (Wikipedia)

0 notes

Text

Plants Help Maghrebi Women Keep Traditions Alive in Marseille

Plants Help Maghrebi Women Keep Traditions Alive in Marseille https://ift.tt/BAugsQ4 Huet and colleagues studied how North African women in Marseille use medicinal plants to maintain their cultural identity. They found that traditional plant knowledge remains strong, with herbs and spices serving as tangible links to home. The most important finding reveals that mint and olive oil act as cultural keystones for Maghrebi women. These plants carry deep symbolic meaning, connecting migrants to family traditions and regional identity. One participant noted: “Mint is our ethos, we wake up with it, we sleep with it.” Researchers conducted interviews and workshops with 24 women, mostly of Algerian origin. They documented 131 plant species used for culinary, medicinal, and ritual purposes. Knowledge is primarily passed down through female family members. Previous studies show migrants often struggle to source familiar plants. However, Marseille’s Mediterranean climate and well-established North African community facilitate access. Women obtain plants through local shops, family networks, foraging, and community gardens. The importance of spices in Maghrebi and Mediterranean cultures is potentially linked to the historical importance of transcontinental trading of aromatic plants, and we found that indeed specialized local traders are the primary source of plants for our participants. Huet, M., Odonne, G., Baghdikian, B., & Teixidor-Toneu, I. (2024). Knowledge and Access to Medicinal and Aromatic Plants by Women from the Maghrebi Diaspora in Marseille. Human Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10745-024-00533-1 ($) ReadCube: https://rdcu.be/dSJmn Cross-posted to Bluesky, Mastodon & Threads. The post Plants Help Maghrebi Women Keep Traditions Alive in Marseille appeared first on Botany One. via Botany One https://botany.one/ September 02, 2024 at 08:30PM

0 notes

Text

ALUMBRAMIENTO

ALUMBRAMIENTO Dirección: Pau Teixidor Reparto: Sofía Milán, María Vázquez, Celia Lopera, Carmen Escudero, Paula Agulló. País: España Año: 2024 Guion: Pau Teixidor, Lorena Iglesias Duración: 101 min. Sinopsis: España, 1982. Lucía, de dieciséis años, se queda embarazada y su madre decide trasladarla a Madrid para dar fin a esta situación imprevista y no deseada. La joven ingresa en…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

La Selva de Leones, XXI. La hormiga Miga liga. (De 6 a 11 años)

La leona Patata Peluda está devorando una colección de libros de el Barco de Vapor y se ha fijado en 'La Hormiga Miga... ¡Liga!', de Emili Teixidor. El libro trata de un 'juicio de enamorados' bastante dispares...

La leona Patata Peluda está devorando una colección de libros de el Barco de Vapor y se ha fijado en ‘La Hormiga Miga… ¡Liga!’, de Emili Teixidor. El libro trata de un ‘juicio de enamorados’ bastante dispares: que si un camaleón y una lagartija, un amor no correspondido entre un hipopótamo y una mariposa amarilla, donde hay mucho ajetreo y todo eso… La jueza, que es la Hormiga Reina, encontrará…

View On WordPress

#10 años#11 años#6 años#7 años#8 años#9 años#Barco de Vapor#comic#Emili Teixidor#La hormiga Miga#León Científico Bigotón#León Patata Peluda#lectura infantil#Liga#podcast#Primeros Lectores

0 notes