#tech duinn

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

The Otherworld of Irish & Welsh Mythology

by Keziah

The Otherworld is a realm not quite separate from our own, all around us and yet not always accessible or visible to us. It has been interpreted as one expansive world and as having numerous realms and kingdoms within the one Otherworld, and is home to many beings – gods, fairies, and spirits of all sorts, along with some of the most honored and beloved dead.

It is described in ‘the Fairy-Faith in Celtic Countries’ by W.Y. Evans-Wentz:

‘But this western Otherworld, if it is what we believe it to be – a poetical picture of the great subjective world – cannot be the realm of any one race of invisible beings to the exclusion of another. In it all alike – gods, Tuatha De Danann, fairies, demons, shades, and every sort of disembodied spirits – find their appropriate abode; for though it seems to surround and interpenetrate this planet even as the X-rays interpenetrate matter, it can have no other limits than those of the Universe itself.’

This cosmological concept descends from the ancient Celtic religions, and the Otherworld (by its many names) is found throughout the lands in which the Celtic tribes resided and lives on within the traditions preserved by reconstructionist and traditional Celtic pagans and Celtic folk magic practitioners. The Otherworld, along with other Celtic pagan beliefs, can also be found within many neo-pagan and neo-druidic practices and movements.

NAMES OF THE OTHERWORLD

The Otherworld bears many names across the Gaelic and Brythonic mythologies and cosmologies.

Irish

In Irish tales, the names of the Otherworld or realms within the Otherworld include:

Tír na nÓg – ‘the Land of the Young’ or ‘the Land of Youth’

Tír Tarngire – ‘the Land of Promise or ‘the Promised Land’

Tír-Innambéo – ‘the Land of the Living’

Tír N-aill – ‘the Other Land’ or ‘the Other World’

Tír fo Thuinn – ‘the Land Beneath the Wave’ (meaning a land underwater)

Mag Mell – ‘the Plain of Delight’ or ‘the Plain of Happiness’

Mag Már – ‘the Great Plain’

Mag Réin – ‘the Plain of the Sea’ or ‘the Sea Plain’

Emain Ablach – ‘the Isle of Apple Trees’

Ildathach – ‘the Many-Colored Land’

Welsh

In Welsh narratives, the Otherworld has been called:

Annwn or Annwfn

DESCRIBING the OTHERWORLD:

In Irish Cosmology & Mythology

Beliefs as to what the Otherworld is like and where it is located range widely. It’s been described as a world beneath our own that can be entered through some portals in caves or at the base of hills and mountains. In many old Irish manuscripts, it’s described as being located somewhere in the Western Ocean. The phantom island of Hy-Brasil is believed by many to be part of the Otherworld. Irish myth tells of Hy-Brasil being cloaked in mist (perhaps féth fíada, a magical mist) or fog which renders it invisible. However, once every seven years the island becomes visible to the human eye for a whole day.

In the Irish tale ‘Immram Brain maic Febail’ (‘the Voyage of Bran mac Febal’), Bran embarks upon a quest to the Otherworld via a sea voyage. Some days into their journey, Bran and his company encounter Manannán mac Lir upon his chariot. Manannán informs them that though their surroundings appear as the sea to them, to the god it appears as a great field of flowers. In this tale, the realms of the Otherworld are depicted as individual islands somewhere in the Western Sea.

In the story ‘Echtrai Cormaic I Tir Tairngiri’ (‘the Adventures of Cormac in the Land of Promise’), Cormac enters the Otherworld and encounters great bronze palaces, houses of white silver that are thatched with the wings of birds, and a courtyard, in the center of which is a great fountain or well with five streams flowing from it. There is said to be a fairy palace beyond the fountain, and there Cormac encounters ‘the loveliest of the world’s women’.

In many tales and poems, the Otherworld is depicted as being incredibly beautiful and as having very many apple trees, hazelnut trees, and great oak trees. It’s said to have plains filled with colorful flowers and dew of honey. And of the food available in the Otherworld, there is nothing that is not irresistibly delicious. Those who dwell within the Otherworld do not age, nor do they feel pain or take ill. Some believe that it is the fruits that grow within the Otherworld that provide its inhabitants with their everlasting youth and good health. Others believe that it’s the Otherworld itself that keeps one young and well.

In modern day, the Otherworld is most known for being the realm of the fairies and their courts. It is less commonly – outside of Irish historians, practitioners of Celtic paganism and Druidry, and keepers of the age-old tradition of Celtic storytelling – understood as the realm of deities, as the realm of all the Sídhe-folk. Here, the Tuatha dé Danann are believed to reside.

The Tuath dé Danann are a tribe of gods and goddesses descended from the goddess Danu. The Tuatha dé Danann are said to have moved from our physical realm to the realm of the Otherworld after facing defeat at the Battle of Tailte. Manannán mac Lir – a famed warrior, sea god, and king over the surviving Tuatha dé Danann – conceals the Otherworld from humankind via féth fíada, a magical mist that is used by the Tuatha dé Danann to render themselves invisible to humankind. Though, it is believed that seers or those with the gift of second sight can see Otherworld portals and entrances, as well as being able to see those that dwell within the Otherworld.

Time moves differently within these realms. Many tales state that one could spend what felt like a few days in the Otherworld, only to return to this world and find that their friends and family had all died, and many years had passed whilst they were away.

In Welsh Cosmology & Mythology

In Welsh tales, the Otherworld (called Annwn) is not ruled over by Manannán mac Lir but by Arawn and, later, Gwyn ap Nudd. In many of the Welsh legends, Annwn is described as a world of eternal youth, free of illness and disease, where no one could ever go hungry for there were endless supplies of food and drink. It was a realm of incomparable beauty where the gods, fairy folk, great ancestors, elves, and spirits reside. Like in Irish myth, Annwn is believed to be either a subterranean realm, under the sea, or on an island to the west. It is also a magical realm hidden from humankind.

Some tales depict a paradise-like world that is like all the best and most beautiful things within our own world with sprawling gardens, plainlands, and orchards, while others describe a ‘hellish’ place (most likely an outcome of the Christianization of the Welsh culture and beliefs). Both interpretations, though, speak of Annwn as the land of the dead.

The Welsh epic ‘Cad Goddeu’ (‘the Battle of the Trees’) tells of a battle between Arawn’s army and the forces of Gwynedd. The army come forth from Annwn is described as being made up of unearthly creatures, such as enormous beasts bearing one hundred heads, great serpents, and giant toads with claws.

The well-known ‘Preiddeu Annwfn’ (‘the Spoils of Annwn’) is another tale mentioning the Otherworld. It is the story of a journey into the Otherworld led by King Arthur. The tale depicts various realms or kingdoms within the Otherworld, including the Fortress of the Mound, the Fortress of Hardness, the Fortress of Mead-Drunkenness, and the Glass Fortress; though some interpret these names to be alternate names for the Otherworld in its entirety and not of individual lands traversed by Arthur within the Otherworld.

The legendary island of Avalon is also seen as a later interpretation of Annwn. Avalon famously features in Arthurian legends as the paradisical Isle of Apples.

ENTERING the OTHERWORLD:

Many of the old tales speak of humans gaining access to the Otherworld. Sometimes they were invited or summoned there by some god or spirit (as Manannán mac Lir was known to do), sometimes they were stolen away or kidnapped by one of the Otherworld’s inhabitants, and some folk entered the Otherworld of their own design during those times of year when the walls between their world and the Otherworld were lowered, such as during Samhain and Beltane. There are also many tales of folk (some quite famous, such as Cuchulainn, Lanval, and Ossian) being lured or enticed away by a fairy to the Otherworld to live as the fairy’s lover. It is also believed that musicians would be stolen away to the Otherworld to entertain its inhabitants.

As mentioned already, many believe openings at the base of hills and mountains to be entrances to the Otherworld. So, too, are ancient burial mounds, bogs, and caves seen as Otherworld gateways. It is also believed that patches of mist or fog could have within them some opening to the Otherworld, as in the Irish tale ‘Echtra Cormaic I Tir Tairngiri’. In this story, King Cormac sets out from Tara with many soldiers to find his way into the Otherworld to take back his wife, daughter, and son (whom he lost in a trade-off for a magic silver bough). On his way, a thick fog befalls the party. When the fog is lifted, Cormac is alone in the plains of a foreign land, having been taken into the Otherworld.

In some tales, one could enter the Otherworld after they were gifted an apple or a branch bearing apples (such as the magic silver bough mentioned in the story above) from a sacred apple tree. The apple or branch was magical and acted as a key, allowing one to pass into the realm of the Sídhe-folk so long as the apple or branch was in their possession.

Sídhe, though now commonly used in reference to those inhabitants of the Otherworld, are the mounds, hills, or places believed to provide access to the Otherworld. Previously, the term sídhe was used specifically to mean the palaces, courts, or halls in which the spirits of the Otherworld resided.

TECH DUINN:

In Irish lore, there is a separate Otherworld where one goes after death. This realm of the dead is Tech Duinn, the domain of Donn – an ancient god of the dead and ancestor of the Gaels. Tech Duinn means ‘the House of the Dark One’ (‘Donn’ means ‘the dark one’).

There is a 9th-century poem which states that Donn’s dying wish was to have his descendants gathered to him when they died – “To me, to my house, you shall all come after your deaths.” While the Otherworld is often described as being a paradise of great beauty, that is not how Tech Duinn is usually depicted. Rather, it is most commonly portrayed as a frightful place of darkness and dread. Why, I do not know. Perhaps this is simply due to it being the home of Donn, the Dark One.

Tech Duinn is said to lie at or beyond Ireland’s western coast. It is believed that the entrance to Tech Duinn lies on, within, or beneath Bull Rock, an islet bearing a natural tunnel and resembling a portal tomb. Bull Rock lies off the western point of the Beara Peninsula.

A line from Yeats comes to mind in regard to the Otherworld in general, but specifically when speaking of Tech Duinn and Donn’s dying wish -

‘In Ireland, this world and the world we go to after death are not far apart.’

Suffice it to say, the Otherworld has inspired numerous poems and exciting and moving tales, pieces of a time long gone by preserved (hopefully) forever through art. And today it is the source of much scholarly exploration and debate. How much of the Otherworld as we understand it now has been altered by Christianization? How many of the old tales were twisted and reinterpreted to suit the narratives of the Church? We do know that a great deal of this occurred within the preservation of Celtic lore and history, and what tales we have of the Otherworld were not left untouched by this. I hope that this piece, as brief as it is, might inspire others to explore the old Celtic tales in their many interpretations, for there is much to be enjoyed there, as well as much to be learned.

SOURCES & FURTHER READING:

'Cad Goddeu'

'Celtic Culture: A Historical Encyclopedia' - Koch, John T.

'Celtic Myths and Legends' - Rolleston, T.A.

'Dictionary of Celtic Mythology' - MacKillop, James

'Encyclopedia of Celtic Mythology and Folklore' - Monoghan, Patricia

'the Fairy Faith in Celtic Countries' - Evans-Wentz, W.Y.

'Hy Brasil: the Metamorphosis of an Island' - Freitag, Barbara

'Immram Brain mac Febail'

'Irish Fairy Tales' - Stephens, James

'the Lord of Ireland' - Ó hÓgáin, Dáithí; Prof.

'the Mabinogi and Other Medieval Welsh Tales' - trans. Ford, Patrick K.

'the Mabinogian - A New Translation' -Davies, Sioned

'Myth, Legend, & Romance: An Encyclopedia of Irish Folk Tradition' - Ó hÓgáin, Dáithí

'the Mythology of Ancient Britain and Ireland' - Squire, Charles

'Otherworlds: Fantasy and History in Medieval Literature' - Byrne, Aisling

'Preiddeu Annwn'

'the Religion of the Ancient Celts' - MacCulloch, J.A.

‘the Sacred Isle: Belief and Religion in pre-Christian Ireland’ - Ó hÓgain, Dáithí; Prof.

‘Tales of the Celtic Otherworld’ -Matthews, John

#otherworld#the otherworld#tech duinn#celtic mythology#irish mythology#welsh mythology#annwn#Tír na nÓg#Cad Goddeu#celtic myth#celtic folklore#irish folklore#welsh folklore#the mabinogion#preiddeu annwn#celtic paganism#celtic pagan#irish paganism#welsh paganism#sheydmade#sheydmade mythology#sheydmade cosmology#sheydmade folklore

40 notes

·

View notes

Audio

Clarissa Connelly’s Tech Duinn

#clarissa connelly#tech duinn#brystet#music#pop#electronic#folk#new age#electronica#art pop#folktronica#chamber music#chamber pop#vocal#baroque pop#avant garde#experimental#bandcamp#its a clarissa connelly christmas#that first song is just so so good#and you can really see why she got signed to warp

35 notes

·

View notes

Text

every time i think "i should do some endgame content" i see the words tech duinn and decide to go afk fishing instead

#wwaffles bein' an idiot#wwaffles plays mabi#im scared of endgame content#the hardest thing i've done is run hardmode advanced dungeons solo#last time i went to tech duinn (which was also the first time i went) i couldnt even damage the enemies

0 notes

Text

🏃🏾♀️💨

la creatura is going to church now! 🎉

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

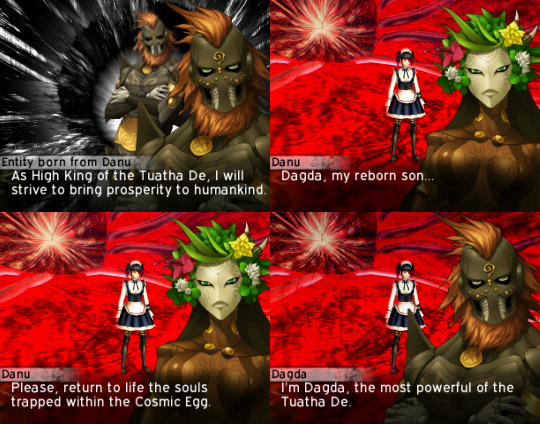

The origins of Dagda and what gets adapted into SMTIVA

Colonization, religious syncretism and famine all play roles in this unusual representation.

1) Who are the Tuatha Dé Danann?

There was a series of invasions of Ireland by a succession of peoples, the fifth of whom was the people known as the Tuatha Dé Danann.

They faced opposition from their enemies, the Fomorians, led by Balor of the Evil Eye. Balor was eventually slain by Lugh.

With the arrival of the Gaels, the Tuatha Dé Danann retired underground and eventually became the fairy people of later myth and legend.

A quick overview to situate those unfamiliarized but their tales aren't the subject of this post.

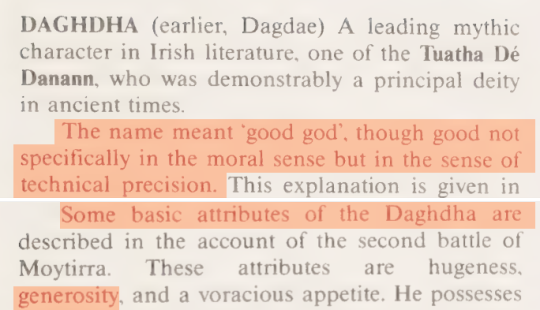

2) Who is Dagda?

Dagda is the chief of the Tuatha Dé Danann, portrayed as a large bearded man in father-figure and druid roles. He is often described as an ideal of masculine excellence (although with a comical tone). He had many mates among female Irish figures.

Dagda possess items that gave him advantage over the Fomorians:

→ A magic club of dual nature: its end could kill nine men in one blow but with the handle he could return the slain to life → A shirt of protection from sickness → A cloak of shape-shifting → A magic harp not only able to command people, but also the seasons → And last, a cauldron which never runs empty. Through these, Dagda becomes able to control life and death, the weather and crops, as well as time and the seasons.

3) Humans or deities?

In truth... The lore of Tuatha Dé Danann being descended from a previous wave of inhabitants of Ireland comes from euhemerized accounts. In non-euhemerized accounts, they are descended from Danu, the mother goddess (lit. "Peoples of the Goddess Danu").

The medieval writers who wrote about the Tuatha Dé Danann were Christians. They described them as neutral angels who sided neither with God nor Lucifer and were punished by being forced to dwell on the Earth. Due to the hesitance in calling them by ‘gods’, they were often stripped of this title and instead lessened as simply ‘humans who had become highly skilled in magic’.

Medieval sources depicted Dagda as “a king of Ireland for eighty years, until turning it over and being killed in battle against the Fomorians”; however, this was an obvious attempt to rationalize his divine nature. Not only Dagda is a leader of gods, it’s not in the exact same sense of a king either.

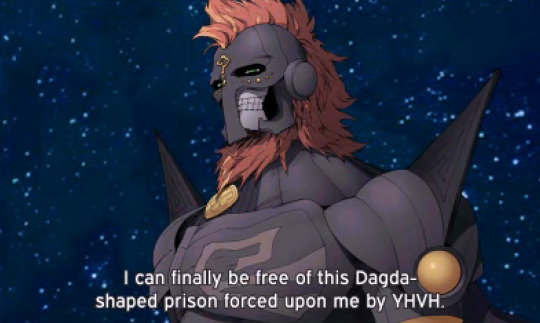

Thus, it’s fair to assume an intended contrast between the “diminished human form” Dagda depicted in the obviously Christian-biased surviving sources and SMTIVA’s “deity-like” Dagda that doesn’t make use of numerous tools to in order to have the means to display unique powers.

4) The Celtic Otherworld

In Irish mythology, Tír na nÓg ('Land of the Young') is one of the names for the Celtic Otherworld (or part of it).

It’s an island paradise and supernatural realm of everlasting youth, beauty, health, abundance and joy, where times also moves differently. Besides deities, it’s also a realm for the dead.

Left: "Land of the Ever Young" (Arthur Rackham) in Irish Fairy Tales (1920). Right: the DLC location Dagda takes you for grinding macca, EXP or items

Means of entry

It exists either in parallel alongside our own, or as a heavenly land beyond the sea or under the earth. Despite its elusiveness, various mythical heroes—such as Cú Chulainn and Fionn —visit it either through chance or after being invited by one of its residents. They often reach it by entering ancient burial mounds or caves, or by going under water or across the western sea.

Sometimes, mortals suddenly find themselves in the Otherworld with the appearance of a magic mist, supernatural beings or unusual animals.

Tech Duinn

In Irish myth, there is another otherworldly realm called Tech Duinn ("House of Donn" or "House of the Dark One"). It was believed that the souls of the dead traveled to Tech Duinn; perhaps to remain there forever, or perhaps before reaching their final destination in the Otherworld, or before being reincarnated.

"Who is the Dark One?", you might wonder.

5) Donn, The Irish God of Death

If you’re familiar with ancient Mediterranean polytheistic religions, you might notice that Donn (the Dark one) shares “death god” similarities with Hades and Pluto.

"One is struck here by the resemblance to the Greek lore of Pluto and the ferrying of souls across the river Styx. The similarity may be explained as a common ancient tradition concerning the dead which had come down to both Greek and Celts but… it seems more sensible to regard it as having originated in general Greek influence. Since the emphasis in these death-beliefs was on the imagery of the west, it is not surprising that the lore was further extended to the westernmost island of Celtdom, Ireland itself.” The Sacred Isle: Belief and Religion in Pre-Christian Ireland (1999)

Donn is responsible for guiding souls from the land of the living to the land of the dead.

Donn’s island, Tech Duinn, is in reality little more than a rock (now known as Bull Rock) situated off the coast of the Beara peninsula. But for centuries that rock inspired fear in the minds of the ancient Irish.

"[...] three red horsemen appear as an omen of death, and they announce: ‘We ride the horses of toothless Donn from the tumuli, although we are alive we are dead!’ Donn is here a personification of the elders buried in the tumuli, which illustrates the physical aspect of funerary practice." The Sacred Isle: Belief and Religion in Pre-Christian Ireland (1999)

Myth vs Pseudohistory

A purely mythological figure, Donn the death god would later become conflated with the quasi-legendary Donn son of Milesius.

“Medieval Irish texts describe the ‘belief of the heathen’ to the effect that souls go there to Donn, and in the pseudo-history Donn is euhemerised as one of the leaders of the Gaelic people when they came to Ireland. We read of this pseudo-historical Donn, however, that he was not destined to reach the shore of Ireland, but was drowned near the rock which bears his name.”

The Gaelic people are also known as the Milesians, namesake of Donn’s dad Milesius. The Milesians were the final invaders/settlers of ancient Ireland. They were the ones who defeated the Tuatha Dé Danann and sent them underground to their tumuli in the euhemerised version.

Donn was an important Milesian military commander and the eldest of Milesius’ eight sons. He seemed like a character fated for a heroic life, yet in every account of Donn’s deeds during the Milesian invasion of Ireland, he was doomed to fall off to his death in the sea in the island and intermixed his tradition to that of death god Donn.

Pre-Celtic roots

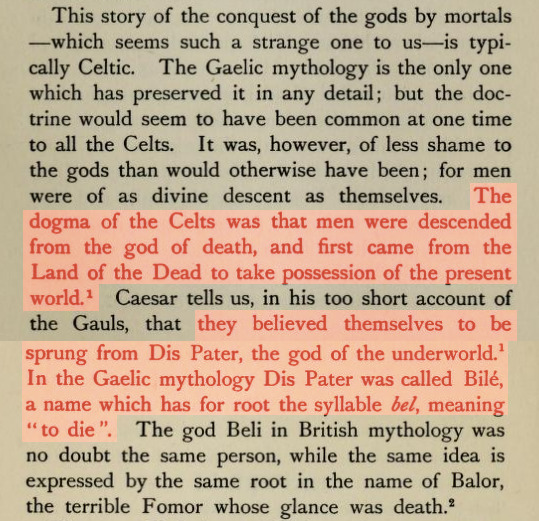

On a following note, some historians suggested that Donn might be actually an iteration of Bilé, Irish god of death who originated in ancient Gaul. Bilé, in turn, is the Gaelic iteration of a much older Celtic god who is often referred to as Bel or Belinos in the Brythonic tradition. He is the namesake of the Celtic feast day Beltane, which was—and among some groups, still is—celebrated on May Eve and May 1st.

In some Irish texts, Bilé is euhemerized as the father of the aforementioned Milesius. Therefore, Bilé is the quasi-historical father of Milesius, making him Donn’s grandfather, and clearly establishing Bilé as the original, more senior Celtic god of death.

"Mistifying" enemy nations

Bilé and the rest of the Gaels who invaded Ireland are described as coming “from Hades.” On a different note, the god of death Bilé is described as also being the source of human life:

The Mythology Of The British Islands: And Introduction to the Celtic Myth, Legend, Poetry, and Romance (1905)

And as shown earlier by what we discussed about Tír na nÓg, the Celts didn't consider the Land of the Dead as being a punishing and oppressive place like hell.

“In Celtic belief the underworld was probably a fertile region and a place of light, nor were its gods harmful and evil.” The Religion of the Ancient Celts (1911)

Totally the same, right? Left: Hortus Deliciarum - 12th century Hell (Herrad von Landsberg) Right: "They rode up to a stately palace" (Stephen Reid)

Are you realizing where this is going?

6) Donn = Bilé = Dagda

"Irish god of the dead whose abode is at Tech Duinn (House of Donn) which is placed on an island off the south-west of Ireland. The house is the assembly place of the dead before they begin their journey to the Otherworld. In modern folklore Donn is associated with shipwrecks and sea storms and sometimes equated with the Dagda and Bilé." A Dictionary of Irish Mythology (1987)

We've reached full circle with our representative always being at the boundary between the world of the dead and the world of the living even under different names and locations.

Also, among Dagda's many names, two are relevant both on this discussion and for his SMTIVA portrayal:

-> An Dagda -> Dagda Donn "The Good God" "Dark Dagda"

While 'good' isn't particularly regarding his own morality, the same source mentions that Dagda is charitable, hence the title can be accurate in an altruistic sense as well.

Meanwhile, the possible (combined, even) reasons behind Dagda being called "Donn (Dark)"...

a) Due to having a dun tunic and a dark cloak b) Due to the death and ancestral god Donn (aka Bilé) originally being a form of Dagda thus being the original dark reflection of Dagda c) "Donn Dagda" being also... "Lord Dagda".

On a similar note, both Dagda and Donn have also been likened to the Germanic god Odin regarding shared motifs and, as pointed out by their dynamic in SMTIVA, Celtic cultures are the ancestors of Germanic people.

This is also emphasized by many of Dagda's other names:

Eochu Ollathair "Horse Great-Father"--generally taken as his "true" name

Fer Benn "man of the peaks" or "horned/pronged man"; could be a poetic reference to lightning, or could indicate a now-lost idea of the Dagda being horned, a not-uncommon feature in British and Gaulish iconography.

Cerrce It may derrive from *perkw "striker", i.e. lightning

Dagda (n)dur/Dagdai duir "harsh/stern" Dagda, but duir also may refer to the oak dair; the association of duir and dair also appears in the ogham tracts. Comparing the Dagda to an oak would also lend credence to the interpretation of him as a thunder god.

But back to the "Good Dagda" and "Dark Dagda" discussion.... What if SMTIVA took these two titles as two separate selves?

Donn Dagda -> Original dark reflection of Dagda -> The Ancestor Dagda from his Pre-Celtic era -> The "Old Dagda" that Nanashi fights against in Bonds while allies with in Massacre -> Immutable part of himself

An Dagda -> His heroic Tuatha Dé Danann self -> More aligned to how he's written in biased sources -> The "Entity created by Danu" that Nanashi allies with in Bonds -> Continuously reborn as long as Danu exists

Notice Danu's choice of wording. "My wish" Donn starts belonging to Danu as a Tuatha Dé Danann (Person of Danu) "good king" "good god" Donn was forced into a "personified" role over simply being nature itself. "forbidden magic" Danu is being self-aware about her true "pagan" origins, as she serves humans as both Tuatha Dé Danann and as Black Maria.

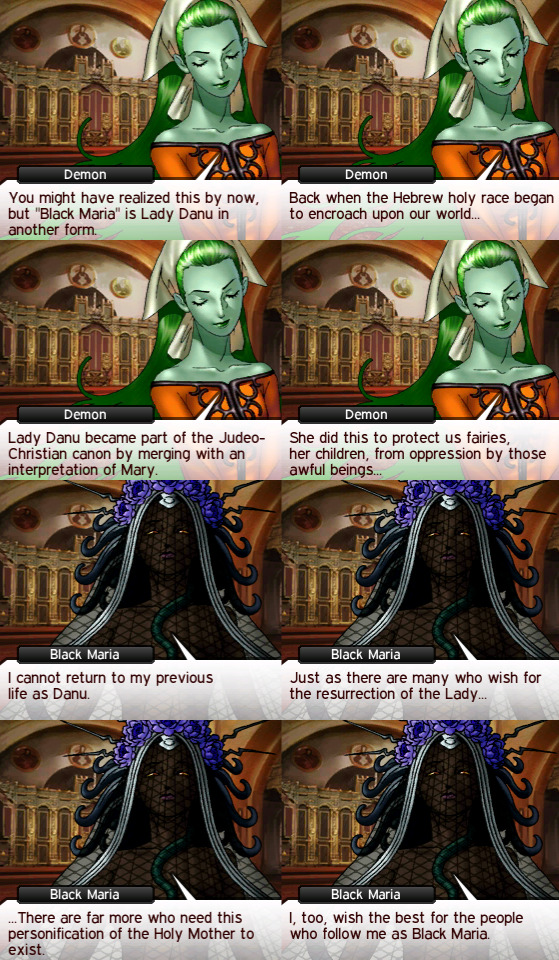

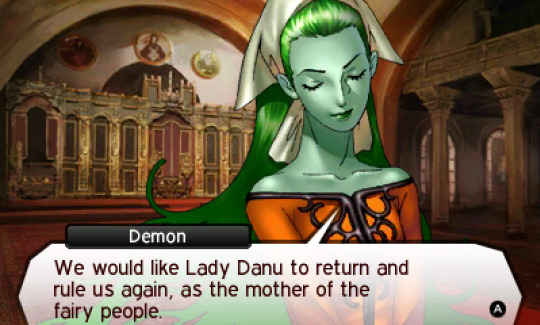

7) Effects of Christianity on Irish folklore

When Christianity was first brought in Ireland during the 5th century by missionaries, they were not able to replace the pre-existing beliefs in the Celtic societies. However, Irish folklore did not remain untouched.

As we mentioned earlier, the fairy folk, who were previously perceived as Gods, became merely magical and of much lesser importance, thus adapted to enforce Christian ideals.

All in all, the current Irish folklore shows a strong absorption of Christianity, including its lesson of morality and spiritual beliefs.

Most of these manuscripts were created by Christian monks, who may well have been torn between a desire to record their native culture and hostility to pagan beliefs.

The Tuatha De Danann were known to come from the heavens, but that may be from scribes not knowing how to execute their origin. So the scribes borrowed from past religions like the Greek, Roman, and Eastern myth to create an origin story.

Earth was also thought to be a woman at the time, so this was thought to be a metaphorical birth.

The uncertainty of Danu's origins

Danu has no surviving myths or legends associated with her in any of the primary Irish texts.

Danu is a hypothesised entity whose sole attestation is in the genitive in the name of the Tuatha dé Danann, which may mean 'the peoples of the goddess Danu' in Old Irish.

In Cormac’s Glossary from the 9th century, the goddess Anu is stated as the mother of the gods. Some scholars suggest that Danu was a conflation of Anu and is the same goddess.

in which case Danu could be a contraction of *di[a] Anu ("goddess Anu"). Also cognates with Dana

Left: Mother Earth image, Atalanta Fugiens Right: The Paps of Danu, a pair of breast-shaped mountains in County Kerry, Ireland.

Some later Victorian folklorists attempted to ascribe certain attributes to Danu, such as association with motherhood and agricultural prosperity due to a "general Mother Earth concept".

"Danu herself probably represented the earth and its fruitfulness, and one might compare her with the Greek Demeter. All the other gods are, at least by title, her children." Squire (1905)

As shown by the flimsy lore attempts regarding Danu, whether medieval Irish literature provides reliable evidence of oral tradition remains a matter for debate. This is indicated in SMTIV&A by how fragile and dependent on biased Christian sources her existence is.

"Nativist" claims have been challenged by "revisionist" scholars who believe that much of the literature was created, often in imitation of the epics of classical literature that came with Latin learning, such as the Illiad. They also argue that the materials depicted in the stories generally date closer to those of the time of their composition (such as bows and chariots) than to those of the distant past.

The Mythological Cycle, which comprised stories of the former gods and origins of the Irish (including the Tuatha Dé Danann), is the least well preserved of the four cycles thus many manuscript sources that could have been what later myth writers based on may have been since disappeared, leading to Tuatha Dé Danann eventually becoming forgotten in the current era.

English colonization

During the 16th century, the English conquest overthrew the traditional political and religious autonomy of the country.

The Great famine of the 1840s, and the deaths and emigration it brought, weakened a still enduring Gaelic culture, especially within the rural proletariat, which was at the time the most traditional social grouping.

In the state of things, with depopulation the most terrific which any country ever experienced, [...] together with the rapid decay of our Irish bardic annals, the vestige of Pagan rites, and the relics of fairy charms were preserved, - can superstition, or if superstitious belief, can superstitious practices continue to exist? - William Wilde

Moreover, global migration has helped overcoming special spatial barriers making it easier for cultures to merge into one another.

All those events have led to a massive decline of native learned Gaelic traditions and Irish language, and with Irish tradition being mainly an oral tradition, this has led to a loss of identity and historical continuity.

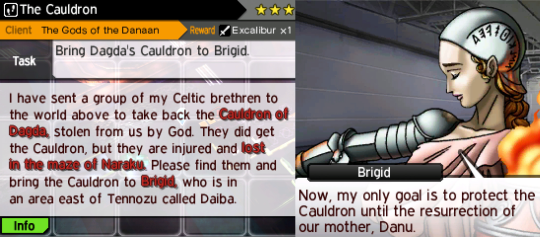

Dagda's (briefly mentioned in-game) daughter

Brigid ('exalted one') is the daughter of Dagda and "the goddess whom poets adored". She is associated with wisdom, poetry, healing, smithing and domesticated animals.

The goddess Brigid was syncretized with the Christian saint of the same name. Medieval monks took the ancient figure and grafted her name and functions onto her Christian counterpart, Brigid of Kildare.

Saint Brigid shares many of the goddess's attributes and her feast day, February 1st, was originally a pagan festival called Imbolc, the first day of spring in Irish tradition.

Art mural depicting the duality of Brigid the pagan goddess and Brigid the saint.

As the more well-known goddess, and later saint, the legends of numerous "minor" goddesses with similar associations may have over time been incorporated into the symbology, worship and tales of Brigid, including Danu and Dagda's own.

This is subtly brought up in the request she makes for Flynn prior to SMTIVA: she requires the rescue of her (then absent) father's cauldron that could feed crowds of people and wait for the return of Danu, the "representative piece" of their group, in order to turn it back to its original state.

On a following note, Brigid's affectional and protective nature is distinctive as she not only began the custom of keening (traditional form of vocal lament for the dead in the Gaelic tradition) while mourning the death of her son but even her animals were said to cry out whenever plundering was committed in Ireland.

Which leads us to the final topic of this post...

8) Irish and the celebration of death

Long before the rise of Christianity, Celtic druids preached that the human soul was eternal thus in death, one simply moved into a different plane of existence (which is the Otherworld we mentioned earlier).

Irish myths also emphasized to us that the barriers between the land of the living and the Otherworld are not always solid, which is perfectly displayed in the festival Samhain:

They believed that on the last night of the old year (October 31st) the lord of death gathered together the souls of all those who had died in the passing year [...], to decree what forms they should inhabit for the next twelve months.

The Book of Hallowe’en (1919)

Brigid alongside Dagda are "personified" concepts that show the picture of how intimate the Irish's relationship with death is.

To quote Scottish journalist Kevin Toolis, you’d be hard-pressed to find a country other than Ireland “where the dying… the living, the bereaved and the dead still openly share the world and remain bound together in the Irish wake.”

The oppressive YHVH forced those whose existences contradicted his own to step down from being gods. The divided Danu wishes to "claim back her lost authority" while still respecting the will of people that interpret her as part of Judeo-Christian lore. Meanwhile, Dagda subverts both YHVH and Danu as desiring to go back to being nature itself rather than its personification that continues the cycle of human dependency on gods and viceversa.

Death begets life. And the most fertile soil is that which is rich with the remains of the once-living. Dagda, as the spiritual father to humankind, wishes to become 'fertile soil' for Nanashi and a new world of humans.

The Donn reflection of Dagda, which is linked to the mythological ancestor of the Gaels, is crucial to the circle of life itself.

44 notes

·

View notes

Text

He has bore countless names over the ages. The Prince of Tech Duinn, The Black Lion - the Devil King by his enemies. And at one point even: 'The Warrior of Light'. Yet eventually all these were lost and forgotten, subsumed by one - Lord Diabolos.

#mine#syrus reverien#i'm spinning a lot of headcanons up here but i'm biting my knuckles about it#in anticipation of Real Void Lore one day#but i figure yanno... it'd probably be like the first#we'd get portions of the world but definitely not All of it right??

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

Current brainworm, none of the Celtic cultures' creation myths have survived, even though they almost certainly had one. The closest we have is the Lebor Gabala Erenn from Irish mythology, but it isn't a creation story, it records the various settlements of Ireland, ending in the Gaels. However, it is thought that there are reflections of an earlier creation myth in the LGE and in the Tain, and there are similar themes that validate that the Gaels at least viewed the creation of the landscape in this way from various other stories. Additionally, we can compare other Indo-European creation myths to figure out what elements the Gaelic creation myth almost certainly would have had. These include:

Before creation, there is a void of some kind

In that void, fire interacts with water/ice to create the first life

A primordial bovine, most likely a cow (bulls were more common in IE cultures that emphasized pastoralism over crops. The Romans had a she-wolf, because they had to be edge lords)

One primordial being or possibly a set of twins who are sustained by the milk of the cow

One of the twins/the primordial being is dismembered to create the physical world

So already we have the makings of a general creation story, and if you're familiar with Norse mythologies, you might recognize it. In fact, it's thought that the Norse creation myth has retained the most elements of the original IE myth

However, scholars point out that the primordial being that is killed is called *Yemo, meaning "twin", which means there was likely originally two first beings. In the one sacrificing the other, the act renders the brother doing the sacrificing as the First Priest, who creates the concept of death, but in doing so turns that death into the living world. The sacrificed brother is then typically rendered as the First King and Ruler of the Land of the Dead. By setting up this order for the world, the First Priest establishes that life cannot exist without death (whether it be harvesting crops or butchering livestock), and typically, these myths continue and establish the role of the priests in society, who's job it is to ensure the continuity of the original sacrifice and maintain the living world

Now, here's where we get into my speculation;

I think it's likely that the Irish creation myth involved a set of twins. Off the top of my head, I think that possible reflections of this can be found in the brothers Amergin and Donn and in the Donn Cuailnge and Finnbhennach from the Táin. With Amergin and Donn, Donn insults the goddess of the land and is drowned. In doing so, Donn becomes a god of the dead and all the souls of the dead have to gather at or pass through Tech Duinn. Amergin however, secures the support of these goddesses and is able to go on and give order to the Gaelic rule of Ireland by deciding who will rule what and serves as the Chief Ollam (bard) of Ireland. In the Táin, after the main Plot has gone down, the Donn Cuailnge and Finnbhennach fight and the the Donn Cuailnge ends up killing Finnbhennach. As the Donn Cuailnge passes through the landscape, pieces of Finnbhennach drop off his horns and form/name part of the landscape. I think it's also interesting how in both these stories, one of the duo is explicitly associated with the color white (Amergin is called "white knees") and the other one is dark, but the opposite one dies first in the stories

Also, if we look at myths like the creation of the Shannon and the Boyne rivers, where in the goddesses Sionnan and Boann, respectively, die in the rivers' creations, we further see that the death of one figure to create an element of the landscape is a relatively common one, so a creation story similar to the one I hypothesize the Irish had wouldn't have been outside of pagan Irish belief

Additionally, if we look at the duíle, kind of like the Irish elements/natural features, we see that the nine elements/features are each explicitly associated with body parts. Stone is associated with bones, the sea with blood, the face with the sun, ect. I think this could be a call back to that earlier creation myth

Off the top of my head, that's what I've been mulling over. Idk, I might be completely off the mark, but if anyone wants give their thoughts, I'd love to hear them. I'm certainly not an expert in Irish mythology and there may be some key factor that completely sinks this idea

#Sword speaks#Irish mythology#Irish pagan#Irish polytheist#Celtic pagan#Celtic polytheist#creation myth#idk man my brain has been like a dog with a bone with this for days and I'm curious what others might think

259 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Irish House of the Dead

Is in Cork, to the surprise of no one.

(Bull Rock, Co. Cork)

Not much is directly known about pre-Christian belief pertaining to the afterlife, there is however many mythological texts from a post Christian period. These texts may give us an indication of what some of these beliefs may have been. From this we can reconstruct a belief in a location known as Tech Duinn as a location visited by the departed. This being Irish for House of Donn

Who's Donn?

A house tends to have a master, and this ones is Donn. Donn is an ancestorial figure to the people of Ireland and is the first of the Milesians to die in Ireland. In the Metrical Dinnseanchas his dying body was placed on a high rock before docking in Ireland to avoid the spreading of the curse of disease put upon it by the Tuatha Dé (link). In the Lebor Gabála Érenn he drowns at this rock due to a battle of curses with the Tuatha Dé (link page 39 & 65). This rock then becomes known as Tech Duinn. He lives on in some capacity however as much later he fathers Diarmuid Ua Duibhne. (link) (maybe, not actually sure if this is a related Donn)

His House and Its Connection to the Dead

This rock on which he died is known as Tech Duinn and is said to be a place in where soul gather after death.

"‘....his folk shall come to this spot.’ So hence it is called Tech Duinn: and for this cause, according to the heathen, the souls of sinners visit Tech Duinn before they go to hell, and give their blessing, ere they go, to the soul of Donn. But as for the righteous soul of a penitent, it beholds the place from afar, and is not borne astray. Such, at least, is the belief of the heathen" (link). The Metrical Dindshenchas-Tech Duinn

Tech Duinn is mentioned in connection to being a place for the departed in numerous places including the above Metrical Dindshenchas and the following texts:

Men of Donn say that "Though we are alive we are dead" in Togail Bruidne Dá Derga. (link).

In the Acallam na Senórach, the Fianna snatch a woman from this house to marry off, this is not specifically related to death but a seemingly regular woman was living in this sidhe and was then taken. Also important to note, Tech Duinn is explicitly said to be in Munster here. (link).

(Hate to rec wikipedia but their page on Donn is decent enough)

Where is it?

In the Acallam na Senórach, Tech Duinn is explicitly called a Sidhe. A mound which connects this world with the Otherworld, this along with the fact that in the Metrical Dindshenchas, Donn's failing body can be placed upon it, implies that this Tech Duinn is a physical location in this world which leads to a house in the Otherworld. The Acallam na Senórach also specifically states this place to be in Munster. As in the LGE Donn drowns as his people attempt to port in Ireland, it is clearly a place off the coast of the country.

These facts all line up quite nicely with folklore which states that Bull Rock, a small island off the coast of Cork, near Dursey Island, is this Sidhe, Tech Duinn. (link) (link)

Bull Rock is a tiny island with an arch going through it, the only thing of note is the lighthouse placed upon it (link)(link). The island has not had a population bigger than 5 in recorded history and is currently uninhabited. It should be noted however that the adjacent Dursey Island is home to evidence of humanity from the bronze age to well past the Medieval era (link) and even is home to multiple Holy Wells (link). It is not farfetched to me that the nearby rock would gain some sort of significance to the people living in this area, especially once the ethereal nature of the rock is seen.

A video recorded of a boat going through the arch of Bull Rock.

vimeo

(Abandoned Buildings on Bull Rock)

What to Take Away From This

It is likely that pre-Christian belief in an afterlife where the soul of the departed traveled to Tech Duinn to be with an ancestorial figure known as Donn, where they stayed with him possibly before moving elsewhere to Hell in Metrical Dindshenchas or possibly under go a process of metempsychosis. This House of Donn was most likely reached through Bull's Rock in County Cork, a small island that resembles a Sidhe.

#donn#ceantar#na déithe#irish paganism#celtic paganism#gaelic paganism#ireland#mine#gaelpol#witchblr#pagan#celtic#Vimeo#resources

74 notes

·

View notes

Text

Tech Duinn, the House of Donn

Many might not know that the Irish have a god of the dead, Donn. His domain is thought to be located around Bull Rock, off the coast of Cork, and every Samhain, he comes to welcome new spirits and guide them westwards to the Otherworld.

This is also my October postcard, so if you’d like to sign up to get one, you can do so here!

#irish mythology#artists on tumblr#irish folklore#illustration#celtic mythology#fantasy illustration#Donn#original illustration#my art

63 notes

·

View notes

Text

The norito or ritual prayers in this Oharae ceremony refer to the land of the dead as Ne no Kuni, a land beyond the sea. The ancient Japanese image of the land of the dead, however, combined two concepts of separate origin. The concept of Ne no Kuni was probably derived from south Asian beliefs that the netherland lay across the sea. The name, which means "root country," suggests that Ne no Kuni was also seen as the original overseas homeland of the Japanese people. Ne no Kuni eventually came to be identified with Yomi no Kuni, the land of the dead beneath the earth in beliefs of north Asian lineage

! land of the dead as across the sea rather than underground or in the sky! not sure what south asian tradition he's referencing, this is from "Early Kami Worship" by Matsumae. seems like this was a thing in ireland and scotland, although not universal

There are a few tales associated with Donn and how he came to be known as the god of the dead to the Irish, ruling over Tech Duinn (‘The House of Donn’), which is said to be situated off the Beara peninsula on the south-west coast.9 It is commonly identified with Bull Rock, an island in the area that has a distinctive dolmen-like shape, with the gap allowing the sea to pass under the rock as if through a gateway.10

the people of the trobiands have a similar belief

A remarkable thing happens to the spirit immediately after its exodus from the body. Broadly speaking, it may be described as a kind of splitting up. In fact, there are two beliefs, which, being obviously incompatible, yet exist side by side. One of them is, that the Baloma (which is the main form of the dead man’s spirit) goes “to Tuma, a small island lying some ten miles to the northwest of the Trobriands.” This island is inhabited by living man as well, who dwell in one large village, also called Tuma; and it is often visited by natives from the main island. The other belief affirms that the spirit leads a short and precarious existence after death near the village, and about the usual haunts of the dead man, such as his garden, or the sea beach, or the waterhole. In this form, the spirit is called kohsi (sometimes pronounced kohsa).

59 notes

·

View notes

Text

Donn, Primordial Irish god of Death. The other half of Danu, Donn was Danu’s lover before creation. The two were wrapped in a primeval embrace of love, from this coupling came the first generation of the Tuatha Dé Danann. Of those born were: Ogma, Nuada, Mananánn Mac lir, the Morrigan, and most importantly the Dagda. The children born were stuck between the two lovers’ embrace in an unmoving vice grip. The lovers couldn’t bear to consciously separate, so their son the Dagda, came up with a plan. He’d hit Donn hard enough to knock him out in one blow so his siblings could free themselves. But when the Dagda struck his father he hadn’t realized just how strong he was, as the Dagda accidentally struck his father dead. Upon the loss of her beloved Donn, Danu wept an unrivaled sob that washed away the Tuatha Dé. Donn’s corpse became the earth, and Danu’s tears became the sea. From the body of Donn grew the world tree Bilé which grew the fruit called humanity. Despite his body’s death, Donn’s soul roamed and built a place for dead souls to go to: Tech Duinn.

Donn’s existence is debated among researchers, as with a majority of subjects regarding pre Christian Ireland there simply isn’t enough evidence to conclude any one answer. My cosmogonic story I wrote above is based on the reconstruction of the pagan Irish creation myth. The name Donn comes from an ancient Irish poem that states that his dying wish was for everyone to gather at Tech Duinn or “the house of Donn” when they die, the idea he was a death god comes from Roman sources which states that the Irish claim decent from a death god. The name Donn may have been originally another name for the Dagda, with Bilé being proposed as the original name for Donn, as in the modern day the two names are used interchangeably for the same deity. Donn and Danu represent two contrasting yet intertwined primal forces, much like the Yin and Yang of Taoism. The name Donn means “the dark one”.

#art#character design#mythology#deity#celtic mythology#irish mythology#celtic#ireland#Irish#donn#bilé#death god#supreme god#tree god#world tree#tuatha de danann#duality god#divine couple

8 notes

·

View notes

Note

28. Diartoria

Prompt: 28. "Your smile brings me so much joy." Ship: Diarturia Tags: Romance

As he stared into her eyes, brushing her blonde hair from her cheek, he wondered if she’d let him kiss her. She looked so beautiful like this, with the sun casting its golden glow upon her face and a lovely tinge of red dusting her cheeks. Her gaze was fond, and her smile soft. The Irish knight was half-convinced he was lost in a dream. He never had any luck with love, after all, and yet, here he was, so smitten .

Describing exactly what the Once and Future King meant to him was a challenge all on its own. There was no one quite like her, and no one with whom he shared the same connection. Theirs was an everlasting dance of blades made to the rhythm of steel on steel. When their weapons clashed, he felt like he was dancing on the clouds. When they were apart, it was like gravity itself drew them together till they clashed once more in a flurry of sparks.

Something in her green irises told him she could see right through to him; take the pages that were his life; read between his every line. He bared his soul to her unafraid, because he knew that with her there was no gavel nor jury that would damn him to a life on the run. There was only her, the regal knight who turned out to be so much more than just the chivalrous figure he met at the docks. He fell twice: for the king she became, and the girl she didn’t get to be.

He was sure the day he met her. He was sure now. She was the culmination of all the work he put in as a knight, the light at the end of the tunnel, the reward that awaited him for his service. He wouldn’t trade anything for the fire he saw in her eyes as they exchanged blows, or the laughter that erupted from his lips when she won, or the smile that graced her face when he claimed victory. She was everything he wanted. Everything.

Arturia’s lips tasted like a warm welcome after a long journey; her mouth, like an embrace before a hearth; her kiss, sweet as hot chocolate on a chilly night. As they parted for a breath, she cupped his cheeks and nudged her forehead into his fondly. She wore a delicate smile upon her face as he pulled her body closer. Diarmuid decided that very moment that he wasn’t losing her again, he didn’t care what impossibilities he’d have to overcome. He’d march up to Avalon and take her to his Tech Duinn, if he had to.

“What is it?” she asked lightheartedly, drinking in the soft chuckle that escaped Diarmuid’s lips.

“Nothing, my lady, I just…” the knight lightly touched the pad of his thumb to her lips. “Your smile brings me so much joy. I no longer believe I can continue on without it– without you.”

Diarmuid took a deep breath, distracted by the smell of her hair.

“I want you to come home with me,” he whispered happily for only her ears to hear. There was confusion in her eyes, but she stayed comfortably circled within his arms.

“What do you mean?” she asked him, stroking her thumb across his cheek. “We do not exactly have lives to live anymore.”

True, they were both Heroic Spirits after all, neither resurrection nor incarnation awaited them now that they were relieved from service. The knight chuckled again, feeling her grin against his mouth as he stole another kiss. “And yet, we have the afterlife, do we not?”

When they parted, Diarmuid dragged his finger down the curve of her lips until the corner. He had always been proud to be one of the few privileged enough to see her so happy. Not everyone could make her feel this way.

“This smile–your smile…” he professed endearingly, “brings me so much joy, my dearest king. No heaven awaits me in my father’s home without it. I would simply waste away.”

Arturia nearly glowed red hearing his words. She didn’t know where he’d found the courage to make such declarations without even a hint of hesitation, when every word was laced with the same truth: he loved her. He loved her so much, he’d denounce eternity’s paradise if it meant he wouldn’t be with her. She’d always thought maidens were being dramatic when they swooned, but she was just short of it herself.

After all, she too would find it terribly lonely, if she were to spend the afterlife without the spearman she grew to love. She didn’t know how Diarmuid could pull this off, nor if it were even possible to leave Avalon and leave with him to Tech Duinn. All she knew was that she wanted the future that he envisioned. They would have each other, forever, and that would be enough.

“Then yes,” she said at last, sealing the promise with another kiss. “I’ll go with you.”

_____

You can't tell me Aengus wouldn't kick down the gates of Avalon and ship Arturia off to Tech Duinn with an exclusive passport made by Donn, you just can't. HAHAHA

thank you for the ask. I hope you are doing well.

-akampana

#akampana asks#rcdp#diarturia#diartoria#diarmuid#arturia pendragon#arturia#diarmuid ua duibhne#fate#saber x lancer

48 notes

·

View notes

Text

Irish Mythology | Donn Fírinne, The Dark One

In Irish mythology, Donn is a god of the dead. Donn is the modern Irish word for the colour brown and appears as an element in many Irish surnames like Donegan, Donovan, Donnelly and on its own as Dunn/Dunne. However in the case of Donn the word derives from the Celtic word ‘dhuosnos’ meaning dark – Dark Lord. Donn is said to dwell in Tech Duinn (the ‘house of Donn” or ‘house of the dark one’). A…

View On WordPress

#Acallam na Senórach#Bull Rock#Celtic Mythology#Clare#Co. Cork#Diarmuid Ua Duibhne#Donn Fírinne#Ireland#Irish Mythology#Jean Guichard Photography#Lebor Gabála Érenn#Limerick

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Donn potentially (?) becoming a god after drowning because he pissed off Ériu is objectively funny once you start thinking about it.

Do the Tuatha Dé ever get together and there’s Donn, in the corner, looking very wet and drowned and dead?

Do they ever greet him with: “Dia duit, Invader!”

Does he join the Tethra/Mannanán “Deity associated with the sea who is Done with this business” club? Do they even want him in the club?

Does Bres hate him because he was mean to his mommy? (Jail for the sons of Míl, jail for one thousand years)

Does Lugh hate him because he invaded Ireland (bad) or love him because he fought against the three sons of Cermait (good)?

Does the Dagda enjoy sometimes whacking him with his staff a few times just for the sake of establishing dominance + punishing him for fighting against his grandsons?

Is there a separate little place for the deities of the sons of Míl to hang out, or is he all alone, hanging out at Tech Duinn and being bullied by the TDD?

Do he and the Cailleach Beara hang out? IS there a Cailleach Beara for him to hang out with?

Maybe drowning wasn’t the worst thing to happen to him.

#donn#irish mythology#mythological cycle#donn is one of the few figures who seems likely to have been a deity at some point#and the because of his treatment in LGE it’s incredibly funny

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

Pagan Afterlife: Where Do Pagans Go When They Die?

posted by : kitty fields

Just as Christians and other religions have their beliefs in an afterlife, so do pagans. Depending on the pagan tradition and even down to the individual, the pagan afterlife will have different names and legends to go along with it. Learn about different ideas of the pagan afterlife and we will answer the question “where do pagans go when they die?”

The Pagan Afterlife

What we’ll cover in this article:

The Wiccan Summerland

The Celtic Otherworld

Norse Pagan Afterlife: Valhalla, Folkvangr and Helheim

Reincarnation

Variations in Belief

Where Do Wiccans Go When They Die?

Wicca is a religion unto itself. Often people get Wiccans mixed up with Pagans. They think if you’re pagan, you must be Wiccan, right? Wrong. There are many different forms of paganism, Wicca is just one branch. That being said, Wiccans believe in a pagan afterlife and they call it the Summerland. The Wiccan Summerland is comparable to the Christians’ Heaven with some pagan differences.

Wiccans believe souls travel to the Wiccan Summerland after death to await reincarnation. Once the soul learns or experiences all it needs, the reincarnation cycle ends. Then the soul stays in the Wiccan Summerland for eternity. Of course, beliefs on exactly how this happens varies. The Wiccan Summerland belief was no doubt influenced by the Celtic Otherworld and the Norse Pagan afterlife.

The Celtic Otherworld

To our ancient Celtic ancestors, death was just a part of the cycle of life. There were various beliefs in a Celtic pagan afterlife, depending on the people. In Welsh mythology, the Celtic Otherworld was called Annwn and was a place of abundance, health, and eternal youth. The Welsh Celtic god Arawn ruled the Celtic Otherworld, as told in the early Welsh prose story The Four Branches of the Mabinogi.

The Irish Celts also believed in the Celtic Otherworld, located somewhere under the earth or under/over the sea. There were many names for it including Tir Na Nog, Tir Naill, Tech Duinn, and Mag Mell. Whether these were different names for the Celtic Otherworld or separate places within it remains a mystery. The Celtic Otherworld was a place where the gods and ancestors lived – a place of eternal life.

Our bodies become the earth after life and are then recycled.

The Norse Germanic Pagan Afterlife

Similar to the Celts’ belief in the Otherworld, the Norse peoples believed in a pagan afterlife too. The World Tree concept was an integral part of Norse paganism, but their name for it was Yggdrasil. The tree consisted of nine realms: Niflheim, Muspelheim, Asgard, Midgard, Jotunheim, Vanaheim, Alfheim, Svartalfheim, and Helheim. The gods, dwarves, giants, elves, humans, and the dead dwelled in various realms throughout.

Maybe you’ve heard the word Valhalla, mentioned often in the popular TV show Vikings. Valhalla was one of the places the dead could go after death – a place with Odin in Asgard for fallen warriors to go in preparation for a future war known as Ragnarok. Hel was another realm of the dead, somewhere under or in the earth, ruled by the goddess Hel. The goddess Freya presided over a field of the dead called Folkvangr.

Valhalla

You’ll find many people online who claim you must be a soldier or die in battle to go to Valhalla with Odin. I believe if you are a warrior for a cause (it doesn’t have to be literal) and you/or you are Odin’s devotee, you have the ability to reach Valhalla. Ultimately it was up to the gods and your deeds on earth that determined where you went in the Norse Pagan afterlife. More can be read about the Norse Pagan beliefs in the Edda by Snorri Sturluson.

Folkvangr: Freya’s Hall of the Dead

Many people forget, there is more than one place in the Norse afterlife where the dead may go. Freya, goddess of love, war and witchcraft, also had her own hall of the dead called Folkvangr. The Norse myths say that those who died on the battlefield were first surveilled by Freya, and she took those whom she wanted FIRST…before Odin received his fallen warriors in Valhalla. But there’s other Sagas that point to the fact that it wasn’t just warriors or fallen warriors that went to Freya’s realm. But those who were devoted to her, as well.

Helheim a.k.a. Hel

No, this is not the same place as the Christian Hell. Though it does have a similar name. I’m sure that happened for a reason. But Helheim, also known as the goddess Hel’s realm, is another place where the dead could go in the Norse pagan afterlife. Although Snorri Sturluson, the scholar who recorded many of the Norse myths, painted Helheim to be a very bleak and torturous place. Modern scholars and neo-pagans believe Sturluson’s view of Helheim was clouded by the Christian influence all around him at the time. Still others claim Helheim is a place where the dead go to rest and even “party” with their ancestors. It is potentially a place where we go before reincarnating…

Pagan Belief in Reincarnation

In addition to having a place for the dead to go after life, many pagans believe in the process of reincarnation. Reincarnation is the belief the soul cycles in and out of physical bodies. When you die in this life, your soul will return to the earth in another body. This concept is worldwide and ancient. Reincarnation can be found in Hinduism, Buddhism, Sikhism, Jainism, and other far east religions. Before the rise of the Church in Europe, the Celts believed in reincarnation and so did the Norse people.

But what happens upon death, exactly?

No one alive knows exactly what happens upon death. I would venture to say the only people who may know have had near-death experiences and were clinically dead for a period of time. Often their stories are similar – floating out of their bodies, flying up into a tunnel of light, and then seeing their dead loved ones or hearing voices on the “other side” before returning to their bodies. This is a consistent story and correlates to the dreams of death I’ve had. Yes, I’ve died in my dreams. I float out of my body, up into the sky, and look around to see the stars before going to a “place” in the sky. It felt as if I was being absorbed into the Universe. If I had to tell you what happens upon death, it would be this.

Variations in Pagan Afterlife Beliefs

Because paganism is an umbrella term, and because there are so many branches of paganism, it’s impossible to give one answer to the question where do pagans go when they die? Every tradition has its own beliefs such as Valhalla, Tir na Nog, and the Summerland. Every individual has their own beliefs about such places which might vary from someone else who follows the same tradition. Still others say we have options when we die: we may choose to go be with the gods, reincarnate, or even to become a guide or ancestor and stay on the earthly plane.

In my humble opinion, I believe whatever you believe in the afterlife is what will happen to you. We create our own realities. That being said, it’s difficult for me to believe in anything other than the cycle of life/death/rebirth. I’ve had too many dreams and experiences that indicate an afterlife is inevitable. Energy never dies, only changes form. So whether we have a soul that moves to the beyond upon death, or whether our energy goes into the earth upon death, either way – our energy just transforms into something else. Therefore, we live forever in one way or another. Othala.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

all travellers who arrive at tech duinn, the house of the dead, the isle of the afterlife, are welcomed with a performance of the ancient ceremonial song: the gambler by kenny rodgers (acoustic)

2 notes

·

View notes