#tawusi melek

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

i was peacefully researcging yezidism when i stumbled upon this f*nfict*on abomination

girl what

1 note

·

View note

Text

Please show support to this person's blog they're writing is very interesting and they're a lovely person

Here are my versions of Etinsib Ziwa/Yawar/Tawûsî Melek and Bihram/Manda d-Hayyi

Eytnozubiwa Yanewozur is an antediluvian hybrid between a virtue and a choir angel who created the Imperfect Creations of the Red Earth and the Awukhoziels. She’s incredibly methodical in a scheming and ruthlessly determined way, ensuring that everything goes according to plan. Despite being a passionate creator and appreciator of life, she’s strangely cold-hearted and dismissive of “inferior lifeforms” like humans. She’s an assertive entity that can approach people in a respectfully direct and honest manner, but can come off as brutally veracious at times. She possesses motherly instincts, a no-nonsense and sure-footed attitude, and a sublime presence that causes great admiration and respect. She’s a diligent, courageous, compassionate, and wise leader and listener that will do anything to protect her brethren and creations from harm and criticism. Eytnozubiwa secretly has neuroticism, which has manifested into poor self-regulation, a strong reaction to perceived threats, being self-conscious, sudden mood swings, and feelings of irritability and self-doubt.

In Eytnozubiwa’s angel form, she’s a 7’ 10” (238.76 cm) mesomorph with a pear-shaped figure, a noticeable musculature, well-endowed breasts, broad shoulders, and upper arms that carry some of her weight. She has rough pallid skin with five prominent dark brown moles: two on the right side of her collarbone; one above her left eyebrow; one near the middle of the back of her right hand; and one on the upper right corner of her lip. Her dull eyes are a pupiless yellowish-green with flecks of blood red and her six wings mimic the colouration of an Indian peacock’s train. She has sharp claws and talons, two rows of omnivorous teeth, and a long choppy shag of milky white with straight bangs, wavy strands of hair, and soft pink and lime green streaks. She often wears a plague doctor mask with rose-tinted glasses and encircling horizontal stripes that match each hue of the rainbow. She has an asparagus green chasuble that has a medieval-style depiction of a black-spotted rose gold panther pinned down by a long-necked ruby and sapphire dragon with bronze claws. She wears pearlescent white gloves that terminate into golden claws and an ankle-length velvet kaftan with long, wide sleeves that reach slightly over her elbows. The kaftan has a gradient from green pea to midnight blue to luxor gold, and she dons a pair of bronze-plated bone forceps earrings. She has a one-layered necklace of Ancient Rome curettes and a blood red bondage crotch rope adorning her torso. She wields an olive stick and a shofar-shaped trumpet of glimmering gold with the opening designed to look like an open-mouthed peacock’s head. Eytnozubiwa carries around a bronze-hued barrel bag of three or five scrolls of lyrical songs, bottled medicines, and small herbal and floral pouches wrapped in red fox fur.

In her celestial form, she’s a 55’ 3” (1684.02 cm) celestial bird with her original head, breasts, and arms, but they have been crudely skinned alive. Her human head has blinded eyes, yellowish-black canine teeth, and a serpentine tongue of glistening bronze. Her breasts are covered in tiny spikes and the left one is full of sticky phlegm, while the other contains highly acidic yellow bile. A rose gold heart vaguely shaped like a Passiflora incarnata is partially protruding out from between her breasts. It has forty purplish-white veins dangling and attaching themselves to her exposed neck, collarbone, and belly region, pumping golden ichor into her body. She possesses the body and wings of a male Japanese green pheasant, and two long-necked, rosy-eyed mute swan heads below her breasts. She has sapphire syndactyly bird feet with ruby toes and razor-sharp golden talons as well as long, flowing tail feathers similar to the Indian peacock. She sports a halo of four blazing blue orbs behind her main head and rusty scalpel-shaped protrusions running down from the tip of her human spine to the tail.

She’s a cosmically aware and omniscient entity that can manipulate light, life, and the physical and emotional aspects of blood, phlegm, black bile, and cholera. She also has total control over the celestial and terrestrial aspects of the sky, sea, and earth. She possesses an exceedingly beautiful singing voice and those who listen to it will feel utter bliss and become enlightened. She can summon heavenly warhorses, peacocks, rainbows that grant sacred blessings, flaming swords, lightning quick arrows, and spiky grapevines. Eytnozubiwa is capable of forcing individuals to speak the truth, strengthening people’s faith in the titans, and alternating between her two forms. She has the ability to view future apocalyptic events and predict the birth of living creatures. She’s a master of improvisation, exorcisms, traditional medicine, surgeries, pathology, philosophy, and environmental adaptation. She has power over the hearts of sentient beings, and can restore all mental, conceptual, emotional, spiritual, mystical, and physical damage.

FAMILY:

Verthanogzimus Mandhelosji (husband)

Smajuzhoktrine Zeliphojandus-Mnelohaviktus Gomeszukiva (adoptive daughter)

Mewhatron (adoptive granddaughter)

Sandezlophim (adoptive grandson)

Zorsjahlen (adoptive granddaughter)

ALIASES/NICKNAMES:

Etinsib Ziwa

Yawar

Tawûsî Melek

Angel of the Heart

The Great Helper

Treasure of Light

FUN FACTS/EXTRA INFORMATION:

As an Æylphitus, the different parts of her name have special meanings: Eytnozubiwa means “splendid transplant” and Yanewozur means “dazzling radiance”.

She’s an avatar of The Four Humours

She’s one of the first members of the divine council

Despite being born an infertile, she’s able to produce breast milk without bearing a child.

She was created by the bright illumination of Äylcephinozur’s soul

She has a strong distaste for fallen angels as well as those who disobey Äylcephinozur and the divine council.

She’s mildly obsessed with maintaining personal hygiene of herself and others, and keeping her spaces as neat and tidy as possible.

She has stuffed the beak of her mask with dried roses, lavender, a vinegar sponge, juniper berries, ambergris, and labdanum.

She uses her olive stick to mark out her personal boundaries and carefully inspect people for any hidden items that might be deemed unsavoury.

Her home has a luscious court garden where a few Indian peafowls roam

Verthanogzimus Mandhelosji is a destroying angel from the oldest generation that has fatherly instincts and a sincere fascination with creation. He’s an unyielding believer of stoicism and consistently exercises its four main virtues: wisdom, courage, temperance, and justice. He’s motivated by sympathy, understanding, and generosity to treat everyone he encounters with impartial benevolence. He can be prudently watchful under dangerous or uneasy circumstances, especially if it involves family, friends, and trusted coworkers. Due to his taciturn nature, he comes off as aloof and uncommunicative, but there are rare instances where he’s unusually talkative. He’s surprisingly calm and unworried, often treating people in a gentle way without extreme criticism. Even when he becomes understandably frustrated and serious-minded, he manages to maintain an easy-going attitude. He’s a versatile thinker who’s able to tackle problems in a creative perspective and to quickly adjust to new situations. Verthanogzimus secretly has major depressive disorder, experiencing anhedonia, a persistently low mood, feelings of worthlessness, and more.

Verthanogzimus’ height is about 10 ft (304.8 cm) and he has an ectomorphic body type with an inverted triangle figure, a square chest, slim limbs, sloping shoulders, a gaunt torso, and a weak musculature. He has uncomfortably smooth snow-white skin that’s slightly translucent, revealing his golden veins running down his neck and up his forearms. He has claws, twelve massive Bartram’s painted vulture wings that can cover his entire body, and sunburst salmon-scarlet eyes with a foggy glaze over them. His back, legs, and shoulders have a light scattering of pearlescent white warts, and his chin-length auburn brown shaggy crop has a light purple sheen. He dons a mid-back cloak made from the pelt of an Asiatic lion with the jawless head acting as a hood, which has a carnassial-to-carnassial bluish-black veil. He also wears a chiton of lilac linen, a dark brown zoster with layered bronze pteruges in bright peacock blue under the breast, and a himation of terracotta pink wool. He’s in possession of a flaming laurel wreath as a halo and a radiant margna tipped with life-giving water. He often wields a simple scythe that has a straight, tail-curling, emerald-eyed snake of coppery red as the snath and its jawless, toothy head is grasping the heel. Verthanogzimus always carries around a steel gada that has a spherical golden head, which is securely tied around his hips with blood red rope. It can fly across vast distances without impediment, communicate with its wielder, and temporarily transform into a winged lion or monstrous monkey.

It’s difficult to easily describe what his true form looks like, but many say it’s unfathomably horrifying with hints of existential beauty. His 61’ 9” (1882.14 cm) skeletal form is cloaked in an unrelenting shadow and grotesquely stuffed with hay, damaged organs, and beady-eyed animal fetuses. His undulating golden flesh is like the texture and coldness of cleansing water and his ribcage holds a red-violet fire that increases virility and induces calmness in the face of death. His eight eyes glow an ominous red, which can reveal what happens after death when those briefly glimpse at them. His tooth-infested metallic purple raven beak continuously expels breeding locusts and toxic blue-green fumes that induces drowsiness, stupor, and insensibility. His back is adorned with numerous tentacled rat tails that are all intertwined and bound together in a misshapen ball through the use of maple sap.

Verthanogzimus can manipulate fertile harvests, sexual potency, sexuality, death, the force of death, pestilence, holy water and fire, ritualistic cleansing, judgement, courage, and victory. He can easily banish any entity that he deems as unwelcomed from entering crop fields and the holiest places of Eylvhraszokjumni. He’s able to create nets from strands of spider silk and sticky blood that can grant invisibility and protection from oncoming attacks. He can summon large, ferocious dragons, giant avian creatures, and flaming axes, and induce forgiveness and rebellion against the unjust. He has absolute knowledge of life and death, and the ability to heal the physical integrity of individuals. He can shapeshift into his true form, the impetuous wind, a gold-horned bull, a white horse, a camel in heat, a wild boar, a bird of prey, a ram, and a wild goat. As a gift from the deities, they bestowed Verthanogzimus with absolute strength in order to make his destructive duties easier to handle.

FAMILY:

Eytnozubiwa Yanewozur (wife)

Smajuzhoktrine Zeliphojandus-Mnelohaviktus Gomeszukiva (adoptive daughter)

Mewhatron (adoptive granddaughter)

Sandezlophim (adoptive grandson)

Zorsjahlen (adoptive granddaughter)

ALIASES/NICKNAMES:

Bihram

Manda d-Hayyi

Angel of the Harvest

The Great Victory

Baptisal Guardian

FUN FACTS/EXTRA INFORMATION:

As an Æylphitus, the different parts of his name have special meanings: Verthanogzimus means “smiting of resistance or victorious” and Mandhelosji means “knower of the life”.

He’s an avatar of Charuzlonje and Parnuzhoktesvi

He’s one of the first members of the divine council

During his free time, he likes to hangout at unoccupied beaches during nighttime as well as hunt dragons and boars.

He’s secretly a master of astrology and fire-handling

He prefers to drink out his most favourite goblet, which is made from the finest purple gold and the cup is shaped like an eagle’s head.

He’s surprisingly good with young children

He occasionally wears reading glasses due to his nearsightedness

Whenever he walks, he leaves behind a trail of rotten flesh, withered flowers, and reddish bundles of wheatgrass.

He enjoys going on strolls with his wife through corn mazes

#writerscorner#creative writing#writing#original character#personality#physical appearance#outfit#abilities#power#angel#virtue#choir angel#destroying angel#destroyer#etinsib ziwa#yawar#tawusi melek#peacock#heart#creation#bihram#manda d-hayyi#harvester#death#fun facts#extra information

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

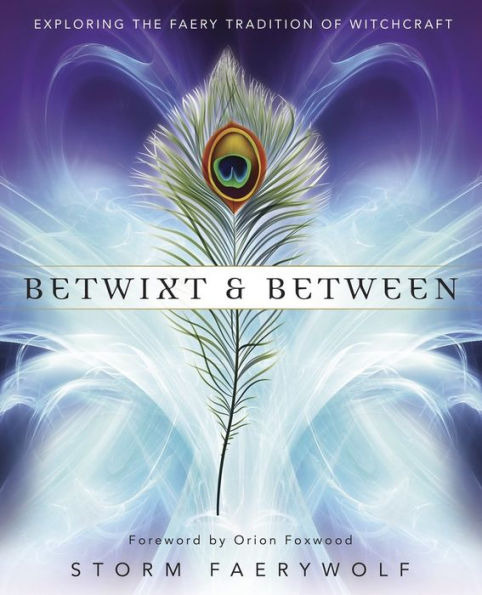

Betwixt and Between Book Review

I read this book in the Pagan and Witches Amino Book Club, that doesn't exist anymore. At the time, the host of the book club was practicing feri and none of us had heard of it so they asked us if we wanted to read this book to learn more. I did a review on that app (that no longer exists), but here's my extended thoughts.

⛧─── ⋆⋅☆⋅⋆ ───⛧

Contents:

Synopsis

What I Liked

What I Didn't Like

Overall Thoughts

Conclusion

⛧─── ⋆⋅☆⋅⋆ ───⛧

Published 2017

"Faery (also known as Feri) is a tradition of great power and beauty. Originating in the West Coast of the United States separately from the Wicca tradition in England, Faery's appeal is grounded in its focus on power and results. This book provides the tools you need to begin your own Faery-style magical practice. Discover the foundational mythology and rites of the Faery tradition as well as steps and techniques for:

Creating an Altar

Summoning the Faery Fire

Engaging the Shadow

Exploring the Personal Trinity

Purifying the Primal Soul

Working with the Iron Pentacle

Aligning Your Life Force

Developing Spirit Alliances

Journeying Between the Worlds

Exploring Air, Fire, Water & Earth

Enhancing Faery Power

Personal experimentation and creative exploration are the heart and soul of Faery. The rituals, recipes, exercises, and lore within will help you project your consciousness into realms beyond this world, opening you to the experience of spiritual ecstasy."

-from the back of the book

⛧─── ⋆⋅☆⋅⋆ ───⛧

What I Liked

The book starts out with the creation myth for the Feri tradition. Not many books on witchcraft traditions/religions do this and it was really refreshing. From there it talks about it's mythic creation as well as it's modern history with Victor Anderson. Seeing both, one after the other, was also enlightening. Faerywolf was definitely taking the creation of this book seriously.

The exercises within the book are very thorough and broken down in a very easy to follow, step-by-step way. There's also some wonderful journaling prompts and art projects once you get into the elemental chapters. These all help the reader to explore the concepts described by the author and decide what makes sense to themselves.

There's a great breakdown of the three soul concept in Feri. Rarely do you see people talk about the conception of the soul and what it means in religion and witchcraft traditions. It's easy to understand how they are all supposed to work together as well as their importance to the Feri tradition. Other traditions have a similar conception of three souls and it's easy to use these to build off of that knowledge.

Additionally there is a chapter for each of the three worlds (Upper, Middle, and Lower). Each chapter talks about spirits found there and how to connect with them. Only one talks about important holidays in Feri such as Halloween and Beltane, relating to the connection of faeries.

The tradition appears to be very accepting of LGBTQ, having special designations for covens that specifically cater to gay men or women if that's something you want to connect to people with. The author himself is LGBTQ so it would make sense that the book is friendly toward the community at large.

⛧─── ⋆⋅☆⋅⋆ ───⛧

What I Didn't Like

I don't want to make this book review a review of the tradition itself, however there are a few things that are directly taken from other cultures. Such as Melek'taus, a variation of the Yazidi Tawusi Melek; a peacock angel, labeled as Sheytan or Satan. The Yazidi are an ethnic group in Kurdistan who have been persecuted as devil-worshippers by the Muslims in the region. Some of the creation myth even resembles that of the Yazidis. There's also concepts taken from Hawaiian traditional religion, Victor Anderson claiming to have been Hawaiian in a past life. The book does not shy away from these facts, and lays them out for you as it introduces them.

The whole book ends up feeling like a lead up to the Feri tradition's circle casting. While you do learn about their worldview as well as the iron and pearl pentacles, it's kind of an anticlimactic way to end the book.

⛧─── ⋆⋅☆⋅⋆ ───⛧

Overall Thoughts

As an outsider to the tradition, this seems like a good introduction to the Feri tradition. There are similarities to both Wicca and your average Traditional Witchcraft tradition though with a more artistic flair, let's say. There's a lot of focus on the arts and experiencing things for yourself. Which is great, in my opinion.

⛧─── ⋆⋅☆⋅⋆ ───⛧

Conclusion

It's always interesting to see how specific, established traditions do things and think about concepts in witchcraft and magic. Even if you do not wish to follow said tradition, it can be good to see another perspective. Though we must be mindful of and sensitive to other cultures and their boundaries. If you wish to look at this book further you can find it on amazon, Barnes and Nobles, the author's website, at the publisher, Llewellyn, and others.

0 notes

Text

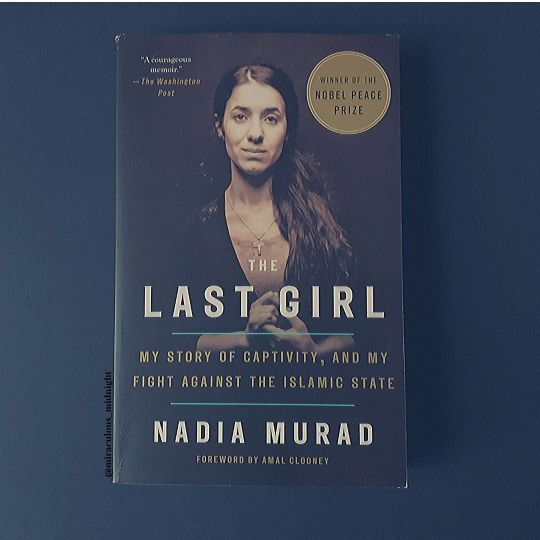

The Last Girl Review

The Last Girl: My Story of Captivity, and My Fight Against the Islamic State

By Nadia Murad

5/5 stars

While some progress has been made in the fight against ISIS, as argued by Nadia Murad in The Last Girl, the problems in Iraq cannot be clearly divided along a line that is determined to label every Muslim as a terrorist. In fact, Murad approaches the controversial topic from a new outlook: the rise of the Islamic State and its supporters has been years in the making, ever since American intervention took down Saddam Hussein and his Baathist institutions. She also explains the situation in Iraq as a religious persecution as ISIS targeted members of religious minorities living in the nation, including Murad herself. In her book, Murad not only argues for the dismantling of the Islamic State but also the humanization and protection of the innocent people who still remain under ISIS control. Her powerful memoir deserves more attention as it is a necessary read in order to fully understand the inner workings of Iraq’s many religious sects as well as a different and relevant, non-western feminist perspective of women living in the Middle East. Through her narrative style, Murad effectively persuades her audience of the need for religious acceptance of the Yazidi people and on a larger scale, the prosecution of the Islamic State for genocide.

Split into three parts, the memoir begins with a historical account of Iraq that explains the rise of ISIS. Starting with Saddam Hussein’s control over the nation and its eventual liberation by Americans in the early 2000s, Murad paints a historical backdrop that informs the reader of decades of political unrest and recurring violence, interwoven with anecdotes from her childhood and the days leading up to the ISIS capture of her village, Kocho. From the tension between political parties, like the Kurdistan Democratic Party and the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan to the growing separation between Yazidis and their Sunni Arab neighbors, one is lead to believe that it was only a matter of time before the temporary bubble of peace that Murad had lived in her entire life popped.

The second section of the memoir begins with the corralling of Murad and her village into the public school. That day, six of her brothers along with the rest of the male residents of Kocho were killed. Murad and the women and children were taken to a secondary location, where she and her young female relatives were separated from Murad’s mother. Murad would later find out that every elderly woman from Kocho, including her mother, was executed and buried in an unmarked grave. Meanwhile, Murad and the young women were sold into slavery, forced to become “sabaya” or sex slaves for ISIS soldiers and high-ranking officers.

After a failed attempt, Murad managed to escape for a second time and find a sympathetic Sunni Arab family that would hide her from ISIS. From this home, she contacted one of her brothers, who was outside the country at the time and able to smuggle her into Kurdistan controlled territory. While her brother worked to help their female relatives and other women escape enslavement, Murad became an activist against ISIS and human trafficking, later speaking in front of the United Nations and winning the 2017 Nobel Peace Prize.

An integral part of The Last Girl as well as Murad herself is the Yazidi religion, which should be protected and accepted across the world, as Murad argues. “Yazidis believe that before God made man, he created seven divine beings, often called angels, who were manifestations of himself,” according to Murad (27). One of these angels, Tawusi Melek (or the Peacock Angel), is the main being to which Yazidis pray and center their practices and celebrations around. However, many Muslim Iraqis consider Yazidis “devil worshippers,” scorning them and their practices for “reasons that have no real roots” in the stories of Yazidis (Murad 28). As a result of this hatred, “outside powers had tried to destroy [Yazidis] seventy-three times” before the genocide of Murad’s people in 2014 (Murad 6). It is this hatred and derision, Murad argues, that led ISIS to target Yazidis in their terrorist campaign. As a religious minority in Iraq, Yazidis relied on the relationship that they had with Sunni Arabs for protection. But as many Sunni Arabs turned to the Islamic State, Yazidis were left vulnerable to the whims of ISIS. As Murad conveys, the acceptance of the Yazidi religion, and religious tolerance on a broader scale, would further prevent the violence and persecution that often follows minorities.

In order to accept and protect Yazidis, one must first become educated on their religious practices and culture. Murad asserts that “Yazidism should be taught in schools from across Iraq to the United States, so that people understood the value of preserving an ancient religion and protecting the people who follow it” (300). In a broader sense, people who are better informed about Yazidism and its history as a persecuted community would be able to better help the Yazidis still under ISIS rule, especially the women forced into sexual slavery. The Last Girl is a moving story and a major contribution to understanding the role of transnational feminisms. It is important to note that while many Yazidi practices and the general attitudes in Iraq reinforce gender inequality, Murad is not arguing for a complete cultural upheaval of these practices and attitudes; she is pushing for what may seem like a small step to western feminists, but freeing the large Yazidi population of women still kept in sexual slavery is what is needed for the feminism that Murad practices, for the betterment of Yazidis, and for a longer path towards female empowerment in the Middle East.

Although Murad advocates for the prevention of Yazidi persecution through religious tolerance, she also wants justice for the crimes committed against her and her people. Murad argues that the Islamic State, “from the leaders down to the citizens who supported their atrocities,” should be put on an international trial for the genocide of the Yazidi people and other war crimes (300). Not only has ISIS executed the majority of Murad’s village, including her mother and brothers, but it has also committed horrific acts of cruelty and continues to do so today in the form of rape and other torture. Murad states that when she fantasizes about putting ISIS on trial, she sees her first rapist, Hajij Salman, captured alive, and as she further describes: “I want to visit him in jail [...] And I want him to look at me and remember what he did to me and understand that this is why he will never be free again” (177). For Murad, holding ISIS responsible for its crimes against humanity is not just for Yazidi justice, it’s personal, and reasonably so. No one should have to go through such unimaginable torture, especially without any form of justice.

In the epilogue of The Last Girl, Mura writes that “the UN finally recognized what ISIS did to Yazidis as a genocide” (304). But without a trial, justice does not exist for Murad and her people. Recognition is not enough. And the longer the UN waits to prosecute the Islamic State, more evidence of its crimes will continue to disappear. But for Murad, the time for waiting is over. Her memoir is not only a testament to her survival and her love for her people but also her unwillingness to let ISIS go unpunished. The Last Girl is evidence, Murad’s written evidence, of the Islamic State’s atrocities. As a survivor, this book is her way of holding ISIS accountable for its crimes. It is an act of defiance that will continue to be a relevant and necessary read for the public until ISIS is formally punished.

Murad’s memoir perfectly conveys her intentions through an effectively enticing narrative that urges the reader to better empathize with the struggles of the Yazidi people and understand the importance of prosecuting the Islamic State on a grand scale. Although this is not a revolutionary take on feminism, it is a compelling story that portrays a nation racked with terrorism in a new light. While Murad’s memoir educates as well as connects western readers to the plight of her people, it also highlights a path to resolving conflict in Iraq from the perspective of those who know the region and its culture best. In order to help her people, Murad argues that one must first understand her history and culture. While the punishment of ISIS is imperative, it is not enough to employ airstrikes on suspected terrorist headquarters. Organizations, like the Islamic State, will only continue to reform as violence, religious persecution of minority groups, and the poor treatment of women persists.

Thanks for reading! I hope you enjoyed this review! Check out my other reviews here!

Credit: Murad, Nadia. The Last Girl: My Story of Captivity, and My Fight Against the Islamic State. New York: Tim Duggan Books, 2017.

#book review#book#books#the last girl#nadia murad#yazidi#islam#inclusive feminism#feminsim#book reviews#book review blog#review#bookreviews#2019 reads#2020 review#book reccs#miraculousmidnightreviews#book reccomendation#reading#book photography

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Creation Story + More

The Yazidis creation story like all others were used against to justify the genocide being placed onto their culture. Throughout The Last Girl Nadia prays to one of the chiefs given to their Gods Tawusi Melek who had once held the world’s fate in their hands. During the tale of the creation story the generation after Adam is the second generation of the Yazidis and in turn face judgement by Muslim Iraqis because their worshiping of Tawusi Melek, which is not suppose to be spoken to others, is seen as the Yazidis worshiping the devil. A rite of passage for the males is their circumcisions which they are held by someone close to the family whom will later be viewed as the Godparents of the son’s. This passage in the book follows how Nadia brothers did odd jobs in Non-Yazidi places and often times made little money in those places due to the centuries of built up distrust similar to their neighbors turning their backs on the Yazidis when ISIS was coming in because of their underlying hate toward the Yazidis culture.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

They gotta stop slandering my man tawusi melek

I'm converting to yazidism

6 notes

·

View notes

Quote

Yazidis believe that before God made man, he created seven divine beings, often called angels, who were manifestations of himself. After forming the universe from the pieces of a broken pearl-like sphere, God sent his chief Angel, Tawusi Melek, to earth, where he took the form of a peacock and painted the world the bright colors of his feathers. The story goes that on earth, Tawusi Melek sees Adam, the first man, whom God has made immortal and perfect, and the Angel challenges God's decision. If Adam is to reproduce, Tawusi Melek suggests, he can't be immortal, and he can't be perfect. He has to eat wheat, which God has forbidden him to do. God tells his Angel that the decision is his, putting the fate of the world in Tawusi Melek's hands. Adam eats wheat, is expelled from paradise, and the second generation of Yazidis are born into the world. Providng his worthiness to God, the Peacock Angel became God's connection to earth and man's link to the heavens. When we pray, we often pray to Tawusi Melek, and our New Year celebrates the day he descended to the earth. Colorful images of the peacock decorate many Yazidi homes, to remind us that it is because of his divine wisdom that we exist at all. Yazidis love Tawuis Melek for his unending devotion to God and because he connects us to our one God.

Nadia Murad, The Last Girl: My Story of Captivity, and My Fight Against the Islamic State

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Store

Notebook 1: A Store

A store, a place to sell cigarettes and fruit. This is the object I’ve chosen to focus upon. However, this is no ordinary store. It is a small shanty made out of loose planks gathered from an abandoned asylum and covered by old sleeping bag. It isn’t much, but it is one of the only fragments of community that still exists for the people of this Greek refugee camp.

This store is a part of a camp inhabited by Yazidis, a religious minority of people who lived in the northern mountainous regions of Iraq. In 2014 the Islamic State of the Levant (ISL) began genocide of religious minorities in that region of Iraq, thus beginning a mass displacement of nearly all of the 500,000 Yazidis who once called northern Iraq their homes. The Yazidi practice itself is separate from traditional Islam because their central object of worship is an angel, an intermediary between humanity and God named Tawusi Melek. The Yazidis see this figure as the main source of divinity towards man, but traditional Muslims interpret this deviation as akin to Satanic worship. Thus bringing upon the traditionally peaceful Yazidis armed militia, from whom the only defense was members of Kurdish fighting forces from Syria and Turkey. The flight of the Yazidis was also aided by controversial American airstrikes which helped to slow ISL in their pursuit of these now homeless refugees.

A man named Ahmed runs the store, it’s the job he had back at home in Iraq before ISL displaced him and his people. After years of running from violence, Ahmed and his family (wife and seven kids) have set up shop in a Greek refugee camp in Petra that houses 1200 Yazidi. The store itself is an economic failure. His greatest commodities are cigarettes, which he sells for the reasonable price of 2.50 Euros a pack. Considering he takes the bus into town where he buys them for 2.35 Euros he is making nearly no money. For some things, Ahmed charges the same price he bought them for, like sugar, which is to valuable of a commodity to price his fellow refugees out of in the interest of profit. Ahmed’s store can lose hundreds of Euros a day, but that’s not really the point. People are free to walk up and take what they wish. If they have money to pay, they hand it to Ahmed. If they have no money, they are free to take what they wish on credit and when they have money again they can pay it back. The items are mostly non-essential comforts, but they are the only luxuries available for this group of people living in the stasis of a refugee camp. But beyond the luxuries available, the store itself affords the citizens of this refugee camp to have the luxury of going to the store…for something…for anything.

This object fits squarely into the War and Figure of the Refugee category. It displays the basic humanity that is often forgotten in the countless millions of refugees fleeing violence and persecution. The bizarre nature of this “store” also goes beyond that. The refugees of this camp were pitted against many of the same horrible challenges on the road to the Greek camp, so despite conflict displacing these people there still exists a community that is arguably stronger then the original. One wherein those that can, take care of those who can’t, and a genuine desire to provide for the community pervades.

Ahmed’s original store in Iraq was a bustling hub of his town’s community before the genocides of the Yazidis began in 2014. It was a store that would bring in over 250 euros a day in profit, and beyond that it was a meeting place. People from all walks would come to Ahmed’s store and just hang out, during the day he served tea and at night it was a place of cards and conversation. It was a place that supported the community but it perhaps did not hold the same value the store in Petra does today.

Though it may just be a fraction of his old store, Ahmed’s new store has actually gained more social relevance as a necessity of those in the refugee camp. The refugee camp at Petra has been described in many different ways, but the conclusions seems to be that the camp is poorly equipped at best, unlivable at worst. It is located in the foothills of Mount Olympus in Greece, which means the temperatures can fluctuate greatly and living conditions can be strenuous considering the refugees live in thin non-insulated tents. These refugees also have traditional familial concerns, they have to raise children and provide for them despite the fact that little specialized treatment is available from the already stretched thin Greek government. Many mothers have already lost young children who simply could not handle the rough way of living. Despite these difficult living conditions, a small return to normalcy is what the store offers, which is more valuable then anything that could have been sold in Ahmed’s store in Iraq. This difference gets right to the core of what a refugee is. They are people who are just looking for a place like home. It will never be the way it was, but simple reminders of what used to be have the weight of gold especially among these Iraqis. It is difficult to comprehend what these people must have gone through on their respective journeys from Iraq to Greece, but a pack of cigarettes and a knowing look from an old friend might bring back a reminder of something that was once thought lost.

1 note

·

View note