#tanisha c. ford

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Read -> Reading -> To-Read

Here's what assistant librarian Ashley's been reading lately!

Just Read: Viper's Dream by Jake Lamar

This book is set in Harlem and follows a man know to the neighborhood as, Viper. This book is fueled with emotion, jazz, and blues.

Currently Reading: You Make It Feel Like Christmas by Donna Hill & Francis Ray

Just in time for the holidays, I am getting in the spirit and reading You Make It Feel Like Christmas which includes two stories within the one book: Rockin' Around that Christmas Tree and The Wish. So far, so good and definitely putting me in the holiday mood!

To-Read: Our Secret Society by Tanisha C. Ford

I have had this book on my list for quite a while and will finally tackle it. This story details the life of Mollie Moon and her great contributions to the Civil Rights movement and much, much more.

See more of Ashley's recs

#books and reading#book recommendations#historical fiction#nonfiction#christmas books#book recs#viper's dream#jake lamar#biography#you make it feel like Christmas#donna hill#francis ray#our secret society#tanisha c. ford#romance#mollie moon#read reading to read#ashleyrecs#LCPL recs

1 note

·

View note

Text

So i made this comment on a really long post about the politics of clothes but I'm not sure anyone is gonna get that far so I wanted to make a post about it so we we can all rejoice in how the coolest shit from American culture is cultivated by black folks. So the reason jeans took off in America is because of SNCC students campaigning in the South. Before this, denim was a tool of the poor working class, and SNCC students were continuing the 50s and early 60s 'Sunday Best' approach to dressing for civil rights activism. However, this was alienating and impractical for bussing thru the south, so SNCC students adopted the dress of southern working class black folk (tho this does not mean that every southern black person appreciated this, however, and should be noted that nuanced conversations were happening around this topic). They found that denim was easy to keep dirt off when traveling thru the south by bus, and overalls often had large pockets to hold pamphlets. (SNCC activists also embraced natural hairstyles at this point, both rejecting their privelege as middle class and because it was a necessity of being on the road without regular guaranteed access to salons and products). It was such a definitive part of SNCC members outfits in the 60s that it became synonymous with activism. Most news at the time usually focused on black activists who performed middle class and respectability to their standards, and thus the white volunteers w SNCC were the ones photographed in jeans, then co-opted by the hippie movement that wanted to capture denims association with activism.

Source: 'SNCC women, denim, and the politics of dress' by Tanisha C Ford in the journal of southern history

#fashion#us politics#us history#fashion history#Activist history#1960s#SNCC#Feminist history#black history#intersectional feminism

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Also, I'd like to add that the reason jeans took off in America is because of SNCC students campaigning in the South. Before this, denim was a tool of the poor working class, and SNCC students were continuing the 50s and early 60s 'Sunday Best' approach to dressing for civil rights activism. However, this was alienating and impractical for bussing thru the south, so SNCC students adopted the dress of southern working class black folk (tho this does not mean that every southern black person appreciated this, however, and should be noted that nuanced conversations were happening around this topic). They found that denim was easy to keep dirt off when traveling thru the south by bus, and overalls often had large pockets to hold pamphlets. (SNCC activists also embraced natural hairstyles at this point, both rejecting their privelege as middle class and because it was a necessity of being on the road without regular guaranteed access to salons and products). It was such a definitive part of SNCC members outfits in the 60s that it became synonymous with activism. Most news at the time usually focused on black activists who performed middle class and respectability to their standards, and thus the white volunteers w SNCC were the ones photographed in jeans, then co-opted by the hippie movement that wanted to capture denims association with activism.

SOURCE: "SNCC, women, and the politics of dress" by Tanisha C. Ford in the journal of southern history

ily, menswear guy

69K notes

·

View notes

Text

Black scholars on Twitter • Wednesday, January 6, 2021 (on the insurrection)

#our world#black scholars#2021#cite black historians#cite black women#tanisha c. ford#megan ming francis#justin zimmermans#dominique jean-louis#american history#politics#black scholars matter#black lives matter

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Remarkable Legacy of Queen Sugar

Illustration by Charles Chaisson for TIME

BY TANISHA C. FORD

NOVEMBER 28, 2022 12:15 PM EST

The New Orleans set of Queen Sugar is buzzing with energy. It’s a relentlessly humid July day, and creator Ava DuVernay has returned to direct the series finale, which will air on Nov. 29, her first time helming an episode since its debut season, in 2016. DuVernay yells “Cut!” and rises from her chair, moving nimbly through the immaculately decorated living room of the show’s central character, Nova Bordelon (Rutina Wesley). DuVernay converses with camera operators and grips. She positions props to her liking. Her light but authoritative touch is on everything from scripts to wardrobe. She finally stops in front of the couch where Wesley lies under a thick blanket, adjusting it to ensure that the actor’s striking face isn’t obscured. They talk briefly about the scene. “We have an unspoken language,” Wesley tells me later. “Ava would speak to me through her pen, and then I would respond with my work.”

To watch DuVernay in action is to understand her creative process on a deeper level. Later she will tell me that she likes to film many takes of the same scene—“collecting my toys,” she calls it—so she has options in the editing room. She’s looking for emotive glances, subtle shifts in posture, the “gentle moments” that characterize Queen Sugar’s intimate storytelling. The Juilliard-trained Wesley is a master at this kind of emotional dexterity. She begins delivering the last words Nova Bordelon will ever utter. As the crew looks on, they seem to carry the bittersweet knowledge that the series into which they’ve poured so much is coming to an end after seven seasons.

Scenes From Around the World in the Aftermath of Queen Elizabeth II’s Death

POSTED 2 MONTHS AGO

Watch More

Queen Sugar, arguably the longest-running African American family drama in history, has revolutionized TV. DuVernay and executive producer Oprah Winfrey charted a path for the show on OWN. It averaged more than a million weekly viewers in its first seasons—a major feat for a boutique cable network during the rise of streaming. African American viewers were hungry for a show that authentically depicted the lives of everyday Black people, that didn’t pathologize them or shroud them under a veil of respectability. The nuanced characters, lighting that celebrated the beauty of melanated skin, and soulful soundtrack galvanized a legion of Twitter fans who shared their commentary using #gimmiesugar. DuVernay and members of the cast and crew joined in, mirroring the type of community the show itself exemplified.

Read more: Ava DuVernay on What Gives Her Hope

SPONSORED CONTENT

TIME is launching a new Kids TV show, see how Smartsheet made it possible.

BY SMARTSHEET

Kofi Siriboe, Rutina Wesley and Dawn-Lyen Gardner on 'Queen Sugar'

OWN

Queen Sugar the show would not exist without Queen Sugar the novel, and Queen Sugar the novel might never have been put in front of DuVernay if not for Winfrey. And not just casually put in front of her: Winfrey was so determined for DuVernay to read Natalie Baszile’s 2014 book, about a woman who inherits an 800-acre family farm in rural Louisiana, that during the director’s stay at Winfrey’s Maui estate in 2014, the host placed copies of Queen Sugar in Ava’s room, at the kitchen table, on the porch. DuVernay finally devoured it, so inspired that she wrote the treatment for the television show on the flight back to Los Angeles.

When it came time to write the pilot, Winfrey encouraged DuVernay to let the book go and filter what she’d read through her own imagination and her own family’s Southern roots. Taking this note, DuVernay conjured magic, creating the Nova Bordelon character, who didn’t exist in the book but became the show’s spiritual anchor. She fleshed out the fictional milieu of St. Josephine, La. And while this worldmaking allowed DuVernay to tackle salient social issues, at its core, Queen Sugar is a show about the power and possibilities of Black love: familial love, romantic love, and love for one’s community. There is the love story between Darla and Ralph Angel, who piece their lives together after battles with addiction and incarceration. Mature Black women appreciated the May-December romance between Violet Bordelon and her devoted husband Hollywood Desonier. Seeing Nova bring her bourgeois sister Charley and nephew Micah deeper into the Movement for Black Lives acknowledged the rich history of grassroots community activism across the South.

More from TIME

Queen Sugar | Official Trailer | Oprah Winfrey Network

0 of 15 seconds,

This video will resume in 8 seconds

Winfrey unilaterally greenlighted the show for OWN. “I didn’t give it any thought,” she told me over the phone. “All of the great things I’ve ever done have come out of feeling and instinct.” Winfrey had launched OWN in 2011—a peak moment in TV’s golden era—to break new ground and support new talent. This golden age may have been in full swing ever since Tony Soprano took a seat in his therapist’s office, but the vestiges of Jim Crow segregation in the industry made it difficult for Black showrunners and executives to seize the moment. By the 2010s, some had busted through, producing shows across genre—Scandal, Being Mary Jane, Empire, Power,Black-ish—about multi-faceted African American characters who defied stereotypes. Shonda Rhimes, Issa Rae, Donald Glover, Lena Waithe, Kenya Barris, Lee Daniels, Courtney A. Kemp, Mara Brock Akil became voices of the so-called Black TV renaissance.

Dawn-Lyen Gardner, Ava DuVernay, Kofi Siriboe and Rutina Wesley on May 20, 2018 in New York City

Paul Bruinooge/Patrick McMullan via Getty Images

DuVernay vowed to keep that door open for others. She proposed to Winfrey that they hire only women to direct the show. That one decision established a creative ethos for Queen Sugar while helping transform industry hiring practices. “I give all, all praise to [Ava],” Winfrey says. At the time, women directors—especially Black women and other women of color—who wanted to break into episodic television were stymied by retrograde industry norms that granted men the most prestigious jobs. This created a maddening paradox: women couldn’t get hired if they didn’t have the experience, and they couldn’t gain the experience without getting hired.

Of the 42 women recruited to direct Queen Sugar, 39 had never directed an episodic series in the U.S. “Ava handpicked all of us,” says Shaz Bennett, who has directed, written, and served as the Season 7 showrunner. “From the beginning, [Ava] would say, ‘Watch the show, and get the feeling of it, but I want you to bring your skill to this.’” Each director’s creative bent brought an emotional texture that enhanced what Bennett describes as Queen Sugar’s “beautiful feminine gaze.”

Read more: 24 Essential Works of Black Cinema Recommended by Black Directors

The show counts among its alumnae Victoria Mahoney, Aurora Guerrero, Amanda Marsalis, and DeMane Davis, who’ve all gone on to have stellar careers in TV—Mahoney went on to direct for Lovecraft Country and The Morning Show, Marsalis for Westworld and Ozark—and their successes reflect those of their peers. Pioneering indie filmmaker Julie Dash, who had never directed a scripted series, had her TV career jump-started. “It’s changed the way people look at women directors,” says Bennett. “Now if you don’t have women directors on your roster, it’s like, ‘You haven’t even been looking.’” DuVernay is proud to see the women and people of color who’ve made up Queen Sugar’s production team parlay that big break into other high-profile opportunities. But she told me what matters most to her is being intentional about leveling the playing field.

“Queen Sugar has been my second job for six years,” DuVernay told me when I visited the set. She’s juggled Sugar while directing other projects, including A Wrinkle in Time and When They See Us, while also distributing films by underrepresented directors through her independent production company, ARRAY Filmworks. Now Queen Sugar is ending on her terms. “It feels complete,” she says. I looked around the set at Nova’s bungalow, Aunt Vi’s diner, and the Bordelons’ farmhouse, and realized I was standing in the brick-and-mortar manifestation of DuVernay’s imagination. She had dreamed this world and collaborated with people who could help her make it a reality. More than anything, I could feel the love between cast and crew, and the palpable spirit of creative excellence that captivated viewers week after week. This is Queen Sugar’s greatest legacy.

MORE MUST-READS FROM TIME

TIME's Top 100 Photos of 2022

I Tested Positive for COVID-19 Right Before the Holidays. What Should I Do?

Column: How To Create a Sense of Belonging In a Divided America

How to Survive the Holidays if You're a Scrooge

Life Expectancy Provides Evidence of How Far Black Americans Have Come

The 10 Best Albums of 2022

Iran Has a Long History of Protest and Activism

6 Ways to Give Better Gifts—Based on Science

CONTACT US AT [email protected].

Sent from my iPhone

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Olive Morris learned early in life the consequences of fighting injustice. She was just 17 in November 1969 when she became caught up in an incident of police brutality. One minute she was hanging out with friends at Desmond’s Hip City, a record store in Brixton, in South London, the next she found herself being beaten by officers.

Accounts vary on exactly what happened. What is known is that Clement Gomwalk, a Nigerian diplomat who was driving his Mercedes, was pulled over by the police near the record store and accused of stealing the car. At the time, the so-called British “sus” law — a reference to a “suspected person” — allowed the police to stop and search people purely on suspicion of wrongdoing, and black people often found themselves the target. Gomwalk protested his arrest and the police became more forceful. A scuffle ensued, and spectators joined in.

At some point Morris stepped in, and she was handcuffed. She fought back, and the officers arrested her on charges of assault and detained her at a police station. “Each time I tried to talk or raise my head I was slapped in the face,” she was quoted as saying in “Violence at Desmond’s Hip City: Gender and Soul Power in London,” an essay by Tanisha C. Ford from the book “The Other Special Relationship: Race, Rights, and Riots in Britain and the United States” (2016). After the police released her some hours later, she went to King’s College Hospital, where pictures were taken of her swollen face and body.

The incident catapulted her into a movement of black women in 1970s Britain fighting against racial discrimination. Morris went on to raise awareness of inequalities by traveling, writing, organizing protests and setting up support groups. She “represents the kind of Black women who, over the years, have thrown themselves into the struggle in this country and made an indelible, if anonymous, mark,” Stella Dadzie, Suzanne Scafe and Beverley Bryan wrote in “Heart of the Race: Black Women’s Lives in Britain” (1985). The authors helped start the movement.

Systemic racism in Britain in the 1970s was particularly acute in the wake of the right-wing politician Enoch Powell’s 1968 “Rivers of Blood” speech, an incendiary attack on racial integration that has been denounced as one of the most racist public addresses in modern British history. A disproportionate number of black families lived in poverty and were subject to police brutality. Black children were classed as educationally subnormal. Mounting racial tensions eventually fed into the Brixton Riots of 1981, in which mostly young black men attacked buildings, set fire to cars and fought the police for three days, resulted in the injuries of 300 people.

As a result, “our kids were being criminalized,” Dadzie said in a phone interview, “steered into a life of petty crime and unemployment.” Between temporary jobs doing clerical work at various offices, Morris helped set up the Brixton Black Women’s Group and the Organization of Women of African and Asian Descent, or OWAAD, the first networks for women of color in Britain. The networks, and OWAAD in particular, had a decisive influence, mobilizing black women to engage in politics and push back against inequalities, particularly in housing and education.

Morris was often one of the loudest voices at demonstrations, including one she helped organize in 1972 after two black children living in public housing died in a fire that was started when their portable heaters were knocked over. The protesters, including 15 children, rallied outside local government offices to demand safer heating in public housing.

Government workers threatened to call the police, but Morris knew the police wouldn’t arrest the children, so she told the group to disperse and sent the children inside the government office. Several minutes later, the head of the housing department came outside and agreed to look into the matter. Central heating was soon installed.

“She never regarded herself as a leader, but in fact she took the lead,” her partner, Mike McColgan, said in a phone interview. In 1972, Morris started squatting in underused buildings. Occupying empty or abandoned buildings was not a crime; rather, if squatters stayed in buildings long enough, they could eventually claim rights to them. At the time, thousands of people were on waiting lists for housing or were living in poor conditions, and by squatting, Morris and others called attention to the fact that properties remained vacant even as people were homeless.

In one instance, a vacant flat above a launderette in South London that Morris and a friend, Liz Obi, had squatted in was turned into a bookshop, called Sabaar, that catered to the black community. It became a meeting space for groups like the Black Workers’ Movement and Black People Against State Harassment.

Morris also traveled to broaden her knowledge and share what she had learned with others. In China she saw how workers were encouraged to develop ideas rather than simply complete mindless tasks, Morris wrote in the Brixton Black Women’s Group newsletter in 1977. “This at first was very difficult for us to understand, because we are so used to being told that workers can only do the mere minimum, like standing in front of a machine or pulling one lever at a time,” she wrote. “We as Black people, of course, are used to being told by racists that we can only learn one thing at a time.”

Olive Elaine Morris was born on June 26, 1952, in St. Catherine, Jamaica, to Vincent Nathaniel Morris and Doris Lowena (Moseley) Morris. Her parents later moved to London, leaving Olive and her three siblings with her grandmother. Olive and her brother Basil joined their parents in London in 1961, and their two younger siblings, Jennifer and Ferran, moved there later. Her father worked as a forklift driver. Her mother built radios and televisions in a factory and cleaned offices.

Morris studied economics and sociology at the University of Manchester on a scholarship, graduating in 1978. She joined the Black Panthers’ Youth Collective as a teenager at a time when there were few legal protections against racial discrimination in Britain. In that time she supported black and white workers on picket lines, protested an immigration law that restricted the rights of commonwealth citizens, and demonstrated against the “sus” laws.

In the summer of 1978, she was bicycling in Spain with McColgan when she felt a sudden pain. On returning home she learned she had non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, a form of cancer. She died on July 12, 1979, at St. Thomas’ Hospital in London. She was 27. The government in South London named an administrative building after her, but it is now set to be demolished, to clear the way for private housing to be built on the site. There are plans to lay a cornerstone memorializing Morris, and a scholarship fund will be set up in her name.

In 2015 Morris also became a face of the Brixton Pound, a currency designed to support businesses in South London. Those who knew Morris lament that she isn’t around to fight the inequalities that remain. Black people are still more likely than white people to be stopped by the police in Britain. Some argue that racism remains entrenched in the establishment and that intolerance has been rising. “If she was alive she would still be out there demonstrating,” her sister, Jennifer Lewis, said in a phone interview. “She would still be fighting.”

- Amie Tseng, “Overlooked No More: How Olive Morris Fought for Black Women’s Rights in Britain.”

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Book Review: Dressed In Dreams: A Black Girls Love Letter To The Power Of Fashion

Dressed In Dreams: A Black Girls Love Letter to Fashion is a book by Dr. Tanisha C. Ford. Tanisha C. Ford is an award winning writer, professor, and cultural critic. According to her professional biography, “Her work centers on social movement history, philanthropy and the cultural politics of money, Black feminism(s), material culture, the built environment, black life in the Rust Belt, girlhood…

View On WordPress

#Black fashion#Black Girls Love Letter to The Power of Fashion#book#book recommendation#book review#change#fashion#fashion book#Fashion Book Review#favorite#favorite book#good vibes#hope#info#Informative Book#it gets better#learning#love#positivity#Rec#recommendation#recommendations#review#Tanisha C Ford#uplifting

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

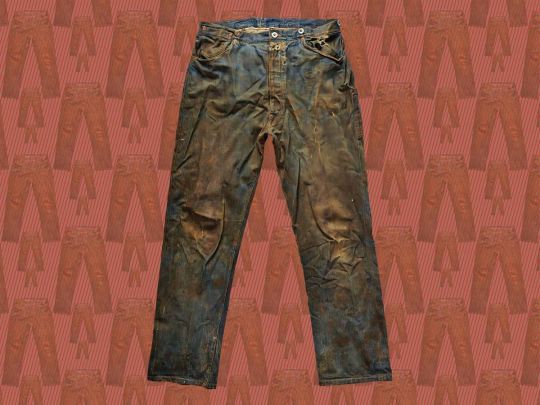

How Denim Became a Political Symbol of the 1960s

https://sciencespies.com/history/how-denim-became-a-political-symbol-of-the-1960s/

How Denim Became a Political Symbol of the 1960s

In the spring of 1965, demonstrators in Camden, Alabama, took to the streets in a series of marches to demand voting rights. Among the demonstrators were “seven or eight out-of-state ministers,” United Press International reported, adding that they wore the “blue denim ‘uniform’ of the civil rights movement over their clerical collars.”

Though most people today don’t associate blue denim with the struggle for black freedom, it played a significant role in the movement. For one thing, the historian Tanisha C. Ford has observed, “The realities of activism,” which could include hours of canvassing in rural areas, made it impractical to organize in one’s “Sunday best.” But denim was also symbolic. Whether in trouser form, overalls or skirts, it not only recalled the work clothes worn by African Americans during slavery and as sharecroppers, but also suggested solidarity with contemporary blue-collar workers and even equality between the sexes, since men and women alike could wear it.

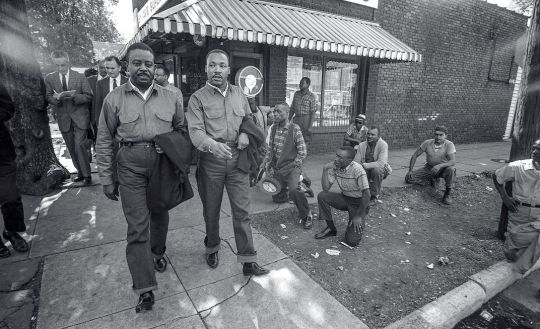

To see how civil rights activists adopted denim, consider the photograph of Martin Luther King Jr. and Ralph Abernathy marching to protest segregation in Birmingham, Alabama, in 1963. Notably, they are wearing jeans. In America and beyond, people would embrace jeans to make defiant statements of their own.

The Rev. Drs. Ralph Abernathy and Martin Luther King Jr. in Birmingham, Alabama, en route to a protest on April 12, 1963.

(Charles Moore / Getty Images)

Scholars trace denim’s roots to 16th-century Nîmes, in the South of France, and Genoa, in northwestern Italy. Many historians suspect that the word “denim” derives from serge de Nîmes, referring to the tough fabric French mills were producing, and that “jeans” comes from the French word for Genoa (Gênes). In the United States, slaveowners in the 19th century clothed enslaved fieldworkers in these hardy fabrics; in the West, miners and other laborers started wearing jeans after a Nevada tailor named Jacob Davis created pants using duck cloth—a denimlike canvas material—purchased from the San Francisco businessman Levi Strauss. Davis produced some 200 pairs over the next 18 months—some in duck cloth, some in denim—and in 1873, the government granted a patent to Davis and Levi Strauss & Co. for the copper-riveted pants, which they sold in both blue denim and brown duck cloth. By the 1890s, Levi Strauss & Co. had established its most enduring style of pants: Levi’s 501 jeans.

Real-life cowboys wore denim, as did actors who played them, and after World War II denim leapt out of the sagebrush and into the big city, as immortalized in the 1953 film The Wild One. Marlon Brando plays Johnny Strabler, the leader of a troublemaking motorcycle gang, and wears blue jeans along with a black leather jacket and black leather boots. “Hey Johnny, what are you rebelling against?” someone asks. His reply: “Whaddaya got?”

In the 1960s, denim came to symbolize a different kind of rebelliousness. Black activists donned jeans and overalls to show that racial caste and black poverty were problems worth addressing. “It took Martin Luther King Jr.’s March on Washington to make [jeans] popular,” writes the art historian Caroline A. Jones. “It was here that civil rights activists were photographed wearing the poor sharecropper’s blue denim overalls to dramatize how little had been accomplished since Reconstruction.” White civil rights advocates followed. As the fashion writer Zoey Washington observes: “Youth activists, specifically members of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, used denim as an equalizer between the sexes and an identifier between social classes.”

But denim has never belonged to just one political persuasion. When the country music star Merle Haggard criticized hippies in his conservative anthem “Okie From Muskogee,” you bet he was often wearing denim. President Ronald Reagan was frequently photographed in denim during visits to his California ranch—the very picture of rugged individualism.

And blue jeans would have to rank high on the list of U.S. cultural exports. In November 1978, Levi Strauss & Co. began selling the first large-scale shipments of jeans behind the Iron Curtain, where the previously hard-to-obtain trousers were markers of status and liberation; East Berliners eagerly lined up to snag them. After the fall of the Berlin Wall, when Levis and other American jean brands became widely available in the USSR, many Soviets were gleeful. “A man hasn’t very much happy minutes in his life, but every happy moment remains in his memory for a long time,” a Moscow teacher named Larisa Popik wrote to Levi Strauss & Co. in 1991. “The buying of Levi’s 501 jeans is one of such moments in my life. I’m 24, but while wearing your jeans I feel myself like a 15-year-old schoolgirl.”

Back in the States, jeans kept pushing the limits. In the early 1990s, TLC, one of the best-selling girl groups of all time, barged into the boys’ club of hip-hop and R&B wearing oversized jeans. These “three little cute girls dressed like boys,” in the words of Rozonda “Chilli” Thomas, one of the group’s members, inspired women across the country to mimic the group’s style.

Curiously, jeans have continued to make waves in Eastern Europe. In the run-up to the 2006 presidential elections in Belarus, activists marched to protest what they characterized as a sham vote in support of an autocratic government. After police seized the opposition’s flags at a pre-election rally, one protester tied a denim shirt to a stick, creating a makeshift flag and giving rise to the movement’s eventual name: the “Jeans Revolution.”

The youth organization Zubr urged followers: “Come out in the streets of your cities and towns in jeans! Let’s show that we are many!” The movement didn’t topple the government, but it illustrated that this everyday garment can still be revolutionary.

Why the dye that would put the blue in jeans was banned when it reached the West —Ted Scheinman

Fabrics soaked with indigo dye in Dali, Yunnan Province, China. “No color has been prized so highly or for so long,” Catherine E. McKinley writes.

(Alamy)

It might seem odd to outlaw a pigment, but that’s what European monarchs did in a strangely zealous campaign against indigo. The ancient blue dye, extracted in an elaborate process from the leaves of the bushy legume Indigofera tinctoria, was first shipped to Europe from India and Java in the 16th century.

To many Europeans, using the dye seemed unpleasant. “The fermenting process yielded a putrid stench not unlike that of a decaying body,” James Sullivan notes in his book Jeans. Unlike other dyes, indigo turns cloth vivid blue only after the dyed fabric has been in contact with air for several minutes, a mysterious delay that some found unsettling.

Plus, indigo represented a threat to European textile merchants who had heavily invested in woad, a homegrown source of blue dye. They played on anxieties about the import in a “deliberate smear campaign,” Jenny Balfour-Paul writes in her history of indigo. Weavers were told it would damage their cloth. A Dutch superstition held that any man who touched the plant would become impotent.

Governments got the message. Germany banned “the devil’s dye” (Teufelsfarbe) for more than 100 years beginning in 1577, while England banned it from 1581 to 1660. In France in 1598, King Henry IV favored woad producers by banning the import of indigo, and in 1609 decreed that anyone using the dye would be executed.

Still, the dye’s resistance to running and fading couldn’t be denied, and by the 18th century it was all the rage in Europe. It would be overtaken by synthetic indigo, developed by the German chemist Johann Friedrich Wilhelm Adolf von Baeyer—a discovery so far-reaching it was awarded a Nobel Prize in 1905.

#History

6 notes

·

View notes

Link

Could you say more about your new book, Dressed in Dreams?

This book is a deep dive into Black America’s closet. I look at iconic garments, hair styles, accessories, and I tell a black-girl-centered history of those items and those hairstyles. And I do that because, far too often, black women and girls have to prove to the fashion industry or the beauty industry that we’ve been wearing these styles.

Long before a Kardashian was doing it, anonymous black girls in every hood across the U.S. have been doing that thing. I wanted to write a love letter to those black women, to those black girls, to those non-binary femmes—who’ve really shaped so much of American fashion culture, but haven’t gotten the credit, and who don’t see themselves in the fashion magazines and, even more than the fashion magazines, don’t see themselves in books about fashion.

I wanted to write a book that centered us, that we could pick from a bookshelf and say: I feel seen. I feel understood. This is my history.

How does this book differ from Liberated Threads?

When I wrote Liberated Threads, I saw myself as a civil rights, black power movement historian using fashion as a lens to help us understand the everyday contours of that movement. But with Dressed in Dreams, I could write something that was deeply personal, that could use elements of creative non-fiction. I was excited to write in a different voice. I could also have something that focused on the human experience of getting dressed in a way that the archive I was using for Liberated Threads didn’t allow for or didn’t account for.

What archives did you work with for Dressed in Dreams?

I first wrote this piece on Dajerria Becton, the teenager who was assaulted by a police officer in a suburb of Dallas, Texas at a pool party, and I started thinking about how our clothes archive all of our experiences—how those experiences are embedded in an emotionality that is then interwoven with the garment itself.

That’s why our clothes mean so much to us. That’s why they have this special emotional value, even if you only paid $2.00 for it. You can care about it so much because you’ve lived in that garment, and part of your life memories are connected to that garment.

I really did collect old garments, and that was part of the process. I also recorded conversations with people where we’re basically just remembering a garment and all of our memories of that garment, or all of our memories together with that garment—so really mining memories, the archive of the mind.

What do you say to feminists whose impulse is to dismiss fashion or see it as a form of oppression? I’m thinking of those who wanted to get rid of the high heels and the bras. There are those who offer a critique of patriarchy and urge us to resist the trappings of femininity, which is what fashion and style is supposed to represent. Then there are the anti-capitalists who see it as just another commercialized project of overconsumption, or the environmentalists who have problems with fur, for example.

I remember when Beyoncé was critiqued for wearing fur in some of her videos for her self-titled album and how that supposedly contradicted her feminist identity. What do you say to any of those kinds of political arguments?

Feminism is expansive, and there are all these different strains of thought within it, so I think that my feminism is one that makes space for a conversation about fashion that doesn’t just take it as something that’s frivolous, but sees the potential for fashion to be liberatory, and also sees the long history in which feminists of all colors, classes and so forth have used style and garments as central to their movement, as central to their activism—creating uniforms, if you will, that help make their political message very clear.

For me, I think that it’s important—as a black feminist historian, as a black feminist thinker, as a black feminist—to understand that the range of responses to fashion are important. We need to understand that style and adornment have always been central to a feminist project and how feminists have defined themselves or pushed back against normative readings of the body.

read more

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

OVERLOOKED

These remarkable black men and women never received obituaries in The New York Times — until now. We’re adding their stories to our project about prominent people whose deaths were not reported by the newspaper.

Since 1851, The New York Times has published thousands of obituaries, capturing the lives and legacies of people who have influenced the world in which we live.

But many important figures were left out.

Overlooked reveals the stories of some of those remarkable people.

We started the series last year by focusing on women like Sylvia Plath, the postwar poet; Emma Gatewood, the hiking grandmother who captivated a nation; and Ana Mendieta, the Cuban artist whose work was bold, raw and sometimes violent. We added to that collection each week.

Now, this special edition of Overlooked highlights a prominent group of black men and women whose lives we did not examine at the time of their deaths.

Many of them were a generation removed from slavery. They often attempted to break the same barriers again and again. Sometimes they made myth out of a painful history, misrepresenting their past to gain a better footing in their future. Some managed to achieve success in their lifetimes, only to die penniless, buried in unmarked graves. But all were pioneers, shaping our world and making paths for future generations.

We hope you’ll spread the word about Overlooked — and tell us who else we missed.

Read about the project’s first year, and use this form to nominate a candidate for future Overlooked obits.

1907-1960

Gladys Bentley

A gender-bending blues performer who became 1920s Harlem royalty.

BY GIOVANNI RUSSONELLO

When it comes to loosening social mores, progress that isn’t made in private has often taken place onstage.

That was certainly the case at the Clam House, a Prohibition-era speakeasy in Harlem, where Gladys Bentley, one of the boldest performers of her era, held court.

READ MORE

1867-1917

Scott Joplin

A pianist and ragtime master who wrote “The Entertainer” and the groundbreaking opera “Treemonisha.”

BY WIL HAYGOOD

When Scott Joplin’s father left the North Carolina plantation where he had been born a slave, there was one thing he wanted to hold on to: the echoes of the Negro spirituals he had heard in the fields. In those songs he found a sense of uplift, hope and possibility.

In the post-Civil War era, the cruel breath of slavery and the aborted plan of Reconstruction still hung over the American South. But in the Joplin home, banjo and fiddle music filled the family’s evenings, giving the children — Scott in particular — a sense of music’s power to move.

READ MORE

1834-1858

Margaret Garner

In one soul-chilling moment, she killed her own daughter rather than return her to the horrors of slavery.

BY REBECCA CARROLL

Margaret garner, who was born as an enslaved girl, almost certainly did not plan to kill her child when she grew up and became an enslaved mother.

But she also couldn’t yet know that the physical, emotional and psychological violence of slavery, relentless and horrific, would one day conspire to force her maternal judgment in a moment already fraught with grave imperative.

READ MORE

1878-1932

Major Taylor

A world champion bicycle racer whose fame was undermined by prejudice.

BY RANDAL C. ARCHIBOLD

More than 100 years ago, one of the most popular spectator sports in the world was bicycle racing, and one of the most popular racers was a squat, strapping man with bulging thighs named Major Taylor.

He set records in his teens and was a world champion at 20. He traveled the globe, racing as far away as Australia, and amassed wealth among the greatest of any athlete of his time. Thousands of people flocked to see him; newspapers fawned over him.

READ MORE

1905-2001

Zelda Wynn Valdes

A fashion designer who outfitted the glittery stars of screen and stage.

BY TANISHA C. FORD

More than a half century before a “curvy” model made the cover of the Sports Illustrated swimsuit issue, and before hashtags like #allbodiesaregoodbodies, there was a designer who knew that it was the job of clothes to fit the woman, not vice versa.

Zelda Wynn Valdes was a designer to the stars who could fit a dress to a body of any size — even if she had to do so just by looking at the client. “I only fit her once in 12 years,” Valdes told The New York Times in 1994 of her long-time client Ella Fitzgerald, “I had to do everything by imagination for her.” Valdes would simply look at Fitzgerald in the latest paper, noting any changes in her full-figured body, and would design the elaborate gowns — with beads and appliques — that she knew Fitzgerald loved.

READ MORE

1941-1970

Alfred Hair

A charismatic businessman who created a movement for Florida’s black artists.

BY GORDON K. HURD

“Well-Known Artist Alfred Hair Slain,” read the headline in The Fort Pierce News Tribune newspaper in Florida.

But before he was killed in a barroom brawl on Aug. 9, 1970, at just 29, Hair had become more than just an artist. With his drive, charisma and business acumen, he helped start a collective of Floridian artists, all African-American, who painted vibrant landscapes of their home state. They would later come to be known as The Florida Highwaymen, or more simply The Highwaymen.

READ MORE

1912-1967

Nina Mae McKinney

An actress who defied the barrier of race to find stardom in Europe.

BY ANITA GATES

About 20 minutes into “Hallelujah,” Hollywood’s first all-sound feature with an all-black cast, Nina Mae McKinney appeared on screen as Chick, a singer and dancer, in a sexy flapper dress.

She had flashing eyes, an armful of jangly bracelets, and no qualms about cheating a handsome young cotton farmer out of the money he had just gotten for his family’s crop.

READ MORE

1856-1910

Granville T. Woods

An inventor known as the ‘Black Edison.’ He found that recognition came at a hefty price.

BY AMISHA PADNANI

He carefully sealed the drawings in a mailing tube and quietly placed them out of sight from his business partner, then went to a meeting.

But when he returned, Granville T. Woods found that his drawings — a design for a novel invention that held the potential to revolutionize transportation around the world — were gone.

READ MORE

1884-1951

Oscar Micheaux

A pioneering filmmaker prefiguring independent directors like Spike Lee and Tyler Perry.

BY MONICA DRAKE

Almost as soon as you settle in to watch the 1939 melodrama “Lying Lips,” you can figure out who is the victim, who is the villain and who is the hero. And even if you know how it all will end, you want to watch anyway.

That was the beauty of the filmmaker Oscar Micheaux. He made you want to soak up the exuberance he clearly felt in delivering a whole new way of telling stories.

READ MORE

1814-1907

Mary Ellen Pleasant

Born into slavery, she became a Gold Rush-era millionaire and a powerful abolitionist.

BY VERONICA CHAMBERS

When the abolitionist John Brown was hanged on Dec. 2, 1859, for murder and treason, a note found in his pocket read, “The ax is laid at the foot of the tree. When the first blow is struck, there will be more money to help.” Officials most likely believed it was written by a wealthy Northerner who had helped fund Brown’s attempt to incite, and arm, an enormous slave uprising by taking over an arsenal at Harpers Ferry in Virginia. No one suspected that the note was written by a black woman named Mary Ellen Pleasant.

In 1901, an elderly Pleasant dictated her autobiography to the journalist Sam Davis. As Lynn Hudson writes in the book “The Making of ‘Mammy Pleasant’: A Black Entrepreneur in Nineteenth-Century San Francisco,” Pleasant told Davis, “Before I pass away, I wish to clear the identity of the party who furnished John Brown with most of his money to start the fight at Harpers Ferry and who signed the letter found on him when he was arrested.” The sum she donated was $30,000 — almost $900,000 in today’s dollars.

READ MORE

1827-1901

Elizabeth Jennings

Life experiences primed her to fight for racial equality. Her moment came on a streetcar ride to church.

BY SAM ROBERTS

Because she was running behind one Sunday morning, Elizabeth Jennings turned out to be a century ahead of her time.

She was a teacher in her 20s, on her way to the First Colored American Congregational Church in Lower Manhattan, where she was the regular organist, when a conductor ordered her off a horse-drawn Third Avenue trolley and told her to wait for a car reserved for black passengers.

READ MORE

1876-1917

Philip A. Payton Jr.

A real estate magnate who turned Harlem into a black mecca.

BY ADEEL HASSAN

“Human hives, honeycombed with little rooms thick with human beings,” is how a white journalist and co-founder of the N.A.A.C.P., Mary White Ovington, described the filthy tenements that black New Yorkers were relegated to at the turn of the 20th century.

As more rural Southerners arrived in the city, the teeming Manhattan slums in which African-Americans were living had become the most densely populated streets in the city, nearly 5,000 people per block, according to one count, as landlords rented almost exclusively to white tenants.

READ MORE

1857-1924

Moses Fleetwood Walker

The first black baseball player in the big leagues, even before Jackie Robinson.

BY RICHARD GOLDSTEIN

When Jackie Robinson joined the Brooklyn Dodgers in 1947, becoming the first African-American player in modern major league baseball, he was not only a trailblazer in the sports world, but an inspiring figure in the modern civil rights movement.

But Robinson was not the first ballplayer in the long history of big league baseball known to be an African-American. That distinction belongs to Moses Fleetwood Walker.

READ MORE

https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2019/obituaries/black-history-month-overlooked.html?smtyp=cur&smid=tw-nytimes

#Emma Gatewood#Gladys Bentley#Scott Joplin#Margaret Garner#Major Taylor#Zelda Wynn Valdes#Alfred Hair#Nina Mae McKinney#Granville T. Woods#Oscar Micheaux#Mary Ellen Pleasant#Elizabeth Jennings#Philip A. Payton Jr.#Moses Fleetwood Walker#Ana Mendieta#NYT

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

Book Launch: "Kwame Brathwaite: Black Is Beautiful"

Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture Harlem USA May 14, 2019

An SRO full house came out for the New York City book launch and signing of Kwame Brathwaite's Black Is Beautiful (Aperture), featuring the photography that helped popularize the slogan “Black Is Beautiful.” The book is available ($40) at the Schomburg gift shop and online.

Brathwaite Sr.and his older brother, Elombe Brath, in the late 50's and early 60’s, did their part to spread this idea through Brathwaite’s writings and photographs, as well as the activities of the two organizations they helped co-found: AJASS (1956) and the Grandassa Models (1962). Grandassa Models was founded to challenge white beauty standards. This monograph — the first ever dedicated to Brathwaite’s remarkable career—tells the story of a key, but under-recognized, figure of the second Harlem Renaissance.

The launch event featured a conversation with Kwame S. Brathwaite (Jr.), Archive Director; Tanisha C. Ford, author and historian; former Grandassa Model Eunice Townsend; and was moderated by Kimberly R. Drew, art curator, writer and social activist. Many of Harlem's well-known photographers came out for the event, and took many photos of each other. One iconic photographer did not bring his camera, because of the rain. Bad call.

Attendees were encouraged to recreate looks and hair styles that pay homage to the "Naturally" fashion shows and cultural celebrations that are also reverberating in the current vernacular of Black style and culture. A fair number did.

#Kwame Brathwaite#Schomburg#Black Culture#Harlem Renaissance#Harlem#photography#african-american#Modeling#fashion#Black Is Beautiful

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

How the Fight for Civil Rights Helped Popularize Denim

Racked had a great article yesterday on how the fight for civil rights helped popularize denim. Most of us think of denim as a working class fabric, a symbol of the American West, as it was worn by miners and cowboys. The fabric, however, wasn’t accepted in fashion until well into the post-war period -- long after miners left California’s hills.

What really popularized denim were the political and cultural fights of the 1960s and ‘70s, ones pushed by civil rights activists, feminists, and anti-war organizers. Those movements, coupled with Hollywood films such as Rebel Without a Cause, made it possible to wear denim off a work site. An except from the Racked piece:

“There were some African Americans who felt that to wear jeans was disrespectful to yourself,” says James Sullivan, author of Jeans: A Cultural History of an American Icon. “For many African Americans, denim workwear represented a painful reminder of the old sharecropper system. James Brown, for one, refused to wear jeans, and for years forbade his band members from wearing them.” Sullivan points out that if you look at pictures of the sons and daughters of the sharecropper generations of the early 20th century who moved north to get away from the fields, you’ll notice that they wore suits, ties, and hats to their factory jobs, partly to create that distance.

Although some protestors knew their white neighbors would chafe against seeing them walk the streets in sharecropper clothes — and used that to their advantage — the strategy wasn't promoted by all Freedom Fighters. Respectability politics was still a popular tactic for gaining support. In 1965, before gearing up to drive down to three hard-core segregationist states in the Deep South to register people to vote, a NAACP representative went to the front of the room during a secret civil rights meeting in New York City, and flatly declared, “We don't want any girls in blue jeans. We don't want any boys in beards.” They wanted people’s hair pressed and collars crisp, knowing how quickly the evening news would misrepresent them if they came in anything less than their Sunday best.

But the responsibility to always look respectable wasn’t just a strategy move, but a burden forced on activists in order to keep white supremacists away from their front doorsteps. As Dr. Tanisha C. Ford explains in her essay “SNCC Women, Denim, and the Politics of Dress,” white supremacists would specifically attack the moral character of black women as a reason to keep their neighborhoods separate and their voting boxes white. Black women had to go above and beyond to prove their respectability in order to protect their characters, and the men and children in their communities. By looking like the type of woman who could bake a bundt cake in a French twist, black women were able to show their Christian propriety and manners, contrasting themselves against the racist stereotypes their white neighbors tried to pin on them. Jeans were not an option.

But as more and more groups headed south for registration projects, more volunteers started to trade in their bobby socks for bootcuts.

It wasn’t just for comfort and durability. To register to vote as a black person was to risk losing your job, or worse, your life by inviting the Klu Klux Klan to your backyard. The fear was evident in the statistics — in Mississippi, fewer than 7 percent of the eligible black population was on the voters list, and in many rural Southern counties there were none at all. And here were these student groups like the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee trying to convince black farmers to risk everything, handing them a clipboard while wearing penny loafers. It created a class divide, and blue jeans were not only the language that would bridge the gap between them, but their show of solidarity.

Even more than that, by putting on the working man’s uniform, revolutionaries showed they didn’t have to dress in a way their white peers deemed “acceptable” in order to gain the rights that were theirs to begin with. Even if activists showed up in banker’s pinstripes, that wouldn’t convert segregationists into allies. “No matter what the whites’ sense of justice tells them needs to be done for Negroes, are they going to let themselves to be bulldozed into doing it?” asked the Missouri Springfield Leader and Press in 1967. Whites refused to be “pushed” toward equality. The movement’s clothes weren’t the issue, and having their appearance policed was just another way of being controlled.

You can read the Racked article here.

47 notes

·

View notes

Photo

WE WILL BE CLOSED 08/31/2020 because of... Alton Sterling David McAtee Modesto Reyes George Perry Floyd Dreasjon “Sean” Reed Michael Brent Charles Ramos Breonna Taylor Manuel “Mannie” Elijah Ellis Atatiana Koquice Jefferson, Emantic “EJ” Fitzgerald Bradford Jr. Charles “Chop” Roundtree Jr. Chinedu Okobi Botham Shem Jean Antwon Rose Jr. Saheed Vassell Stephon Alonzo Clark Aaron Bailey Charleena Chavon Lyles Fetus of Charleena Chavon Lyles Jordan Edwards Chad Robertson Deborah Danner Trayford Pellerin Alfred Olango Terence Crutcher Terrence LeDell Sterling Korryn Gaines Joseph Curtis Mann Philando Castile Bettie “Betty Boo” Jones Quintonio LeGrier Corey Lamar Jones Jamar O’Neal Clark Jeremy “Bam Bam” McDole India Kager Samuel Vincent DuBose, Sandra Bland Brendon K. Glenn Freddie Carlos Gray Jr Walter Lamar Scott Eric Courtney Harris Phillip Gregory White Mya Shawatza Hall Meagan Hockaday Tony Terrell Robinson Janisha Fonville Natasha McKenna Jerame C. Reid Rumain Brisbon Tamir Rice Akai Kareem Gurley Tanisha N. Anderson Dante Parker Ezell Ford Michael Brown Jr. John Crawford III Eric Garner Jacob Blake …AND SO MANY OTHERS! Be the Change! Come in on Friday & Saturday to register to vote and talk about how we can be the change ! You can also hit the link in our bio to register to vote right now ! #BlackLivesMatter (at Sneaker Politics) https://www.instagram.com/p/CEay0dPhEoI/?igshid=mv65uqdoc5m5

0 notes

Text

Dressed in Dreams: Freida Pinto, Gabrielle Union team up for adaptation of Tanisha C Ford’s critically acclaimed book

Dressed in Dreams: Freida Pinto, Gabrielle Union team up for adaptation of Tanisha C Ford’s critically acclaimed book

[ad_1]

Slumdog Millionaire fame actor Freida Pinto and Hollywood actor Gabrielle Union are coming together for a series based on the criticially-acclaimed book “Dressed in Dreams: A Black Girl’sLove Letter to the Power of Fashion” by author and culture critic, Tanisha C Ford. The book was published in 2019 by St Martin’s Press to critical acclaim. In his review of the book, New York Times…

View On WordPress

#Ahmaud Arbery#Black#black lives matter#Black Lives Matter Movement#Blackout Tuesday#BLM Movement#Breonna Taylor#Bristol#Confederate#Donald Trump#Dressed in Dreams#Edward Colston#Facebook#Freida Pinto#Gabrielle Union#George Floyd#Hollywood#Instagram#london#minneapolis#New York#Police brutality#police violence#POTUS#protest#protests#racism#racist#Slavery#slaves

0 notes

Photo

*Post* I am in an odd situation. I very much love the people close to me. I want the best for them. However, I cannot take on your new-found anguish and sadness over the murder of George Floyd. Recent events have forced me to prioritize and deal with things internally and I cannot take on the burden of your suffering while also getting through my own caused by his death and the death of so many others. For fuck's sake, I'm STILL wearing a black hoodie every day for Trayvon. I understand that this is a lot for so many and the protests and advocacy and vigils are out there for you to demonstrate your support. Take the time and help each other through these times. I'm sorry that I can't make any of the people that I love to feel any better. I've had far too much. There have also been many to ask how I feel about it. I appreciate you asking and caring. I feel like I have for most of my life when it comes to these issues. I feel broken. I feel drained. I feel all the same ongoing trauma of a lifetime of being black in this country would provide. My glass runneth over long before we got t this point... P.S. If you are a person who feels the need to bring your "I don't think they should be rioting/protesting/looting/*insert whatever* to me then know, for certain, then it takes me absolutely no effort to act as I've never known you... I am not interested in your stance and seeing as I don't have the energy to help people I love I sure as shit don't have the energy to wait while you masturbate your politics AT me... ************************************** "Eric Garner had just broken up a fight, according to witness testimony. Ezell Ford was walking in his neighborhood. Michelle Cusseaux was changing the lock on her home's door when police arrived to take her to a mental health facility. Tanisha Anderson was having a bad mental health episode, and her brother called 911. Tamir Rice was playing in a park. Natasha McKenna was having a schizophrenic episode when she was tazed in Fairfax, Va. Walter Scott was going to an auto-parts store. Bettie Jones answered the door to let Chicago police officers in to help her upstairs neighbor,who had c https://www.instagram.com/p/CA0OOmOhrT2qhUz7CSom28X8nu_3FUGR4h7wL40/?igshid=1u3l2ik4x8mwq

0 notes

Quote

More than five decades ago, Abbey Lincoln introduced jazz audiences to her rebel sounds on We Insist!. Both cerebral and sensorial, the five-track album was a work of musical innovation, now considered one of the first overtly political albums of the Black Freedom movement. The only woman involved in the writing and composing (though she is only listed as a vocalist in the album’s credits), Lincoln uses her voice as both instrument and siren on “Freedom Day” and “Triptych: Prayer, Protest, Peace” to communicate the political urgency of the moment. Black rage, pain, despair, and hope are made palpable through Lincoln’s quiet hums and moans, which crescendo into screams, screeches, and chants. Crescendo. Decrescendo. Her guttural sounds are intense and impatient, insistent, demanding: FREEDOM NOW.

Tanisha C. Ford at NewBlackMan (inExile). Esperanza Spalding Conjures Abbey Lincoln's Insurgent Moans

2 notes

·

View notes