#sugawa

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

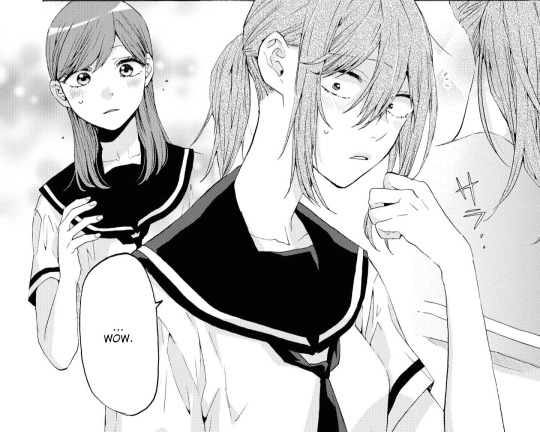

THESE TWO IN THESE OUTFITS ARE TOO CUTE!!!

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

Today's anime cat of the day is:

Neko-sensei from Ebiten!

#neko sensei#ebiten#ebisugawa public high school's tenmonbu#kouritsu ebi sugawa koukou tenmonbu#anime cat#anime cat of the day

80 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hello, Melancholic!

Yayoi Oosawa

#hello melancholic#yayoi oosawa#manga#mangacap#shoujo ai#yuri#girls love#romance#comedy#school life#band#music#pushy#hibiki sugawa#minato asano#monochrome

136 notes

·

View notes

Text

[Updated] Otome Drama CD - Hanaemu Kare to Synopsis and Character Introduction

With the game's announcement, I've decided to update the post for those who are interested in checking out the drama CDs!

Read More on SinfulLiesel.com 🌺

#otome drama cd#hanaemu kare to#hanakare#wataru tori#ginnosuke sugawa#tenya minami#hokuto ichige#otome#ryohei kimura#ryota suzuki#atsushi tamaru#makoto furukawa

38 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hello Melancholic was the first manga I bought. 10/10 purchase it's a really cute yuri romance, only 3 volumes sadly though :'D

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

Him, the Smile & Bloom (Hanakare) Ginnosuke Sugawa Walkthrough

Official Website: Japanese Where to buy: CD Japan (Physical) | Nintendo eShop JP Route Tips & Notes There are no locked routes in Hanakare, you can pursue any of the four routes from the start–so go with your favorite character first! But, if you really want a personal route order recommendation: Wataru ▶ Ginnosuke ▶ Hokuto ▶ Tenya Each route has three unique endings: Bloom (Happy End), Glow…

#Ginnosuke Sugawa#Hanaemu Kare to & bloom#Hanaemu Kare to & bloom walkthrough#Hanakare#Him the Smile & Bloom#Him the Smile & Bloom Walkthrough#Otome Game Walkthrough

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Get ‘em All//「みな殺しの歌」より 拳銃よさらば (1960) d. Eizo Sugawa

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

the last post made me think and here's a reminder of all the magical girl talks i have currently presented at one point in time:

Fight Like a Girl: The Importance and Impact of the Magical Girl Genre

Magical Girls From Around the World: The Cultural Exchange of the Magical Girl Genre

Put on Your Armor!: How Fashion can Empower

Before Madoka: Deep Dark Magical Girl Series and Moments

Lesser Known Magical Girls: The Hidden Gems and the 'Should-Have-Stayed-Hidden'

Precure Rainbow Burst: Diversity in the Magical Girl Genre

The History of the Global Exchange of Magical Girls in Comics and Manga

and here are the ones in the works:

So you want to watch Precure? A comprehensive guide of each season.

Musical Identity of Precure

Weird Science: How Science and Magic co-exists within the magical girl genre

#if i could spend my life professionally researching mgs i would#sugawa-shimada is my hero i love her

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

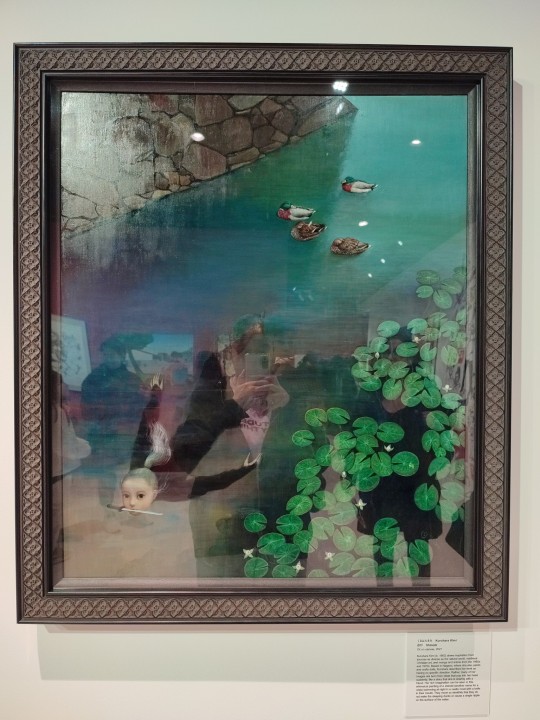

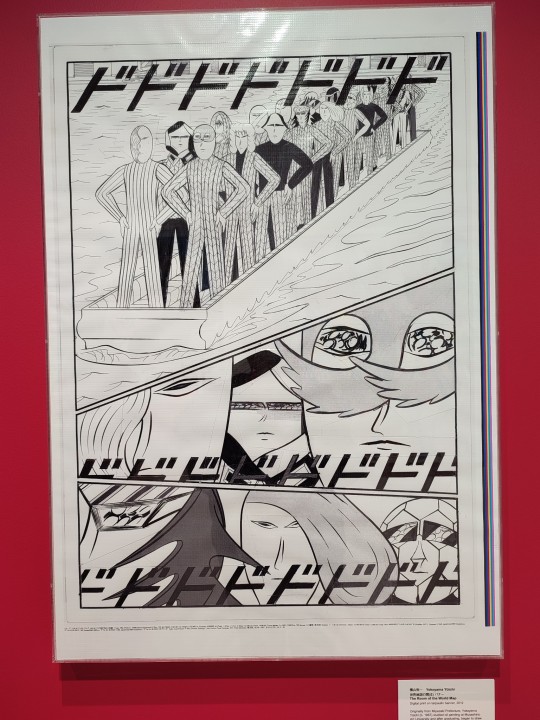

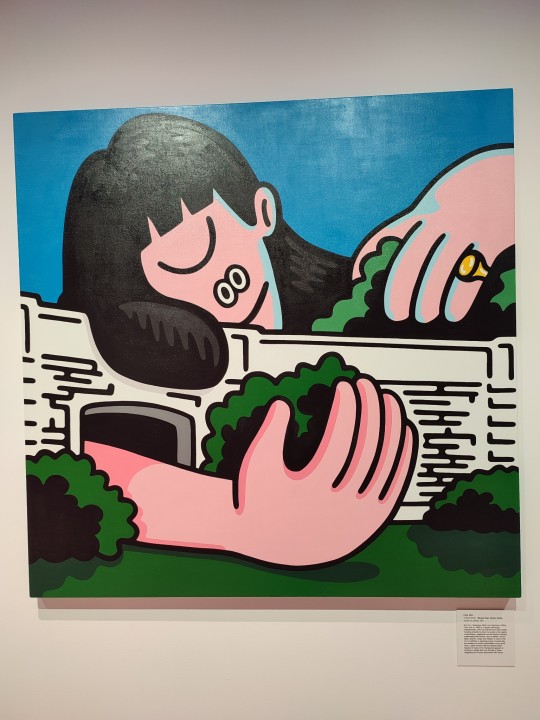

Wave: Currents in Japanese graphic arts exhibition 4/7.

#wave currents in japanese graphic arts#kimi kuruhara#mica suga#jenny kaori#makiko sugawa#masanori ushiki#yuichi yokoyama#face oka#sasaku kusuriyubi#hikaru ichijo#japan house#photography#london#exhibition

1 note

·

View note

Text

YES THIS IS TRUE LOVE

#hello melancholic#asano minato#hibiki sugawa#manga#manga cap#greyscale#long hair#ponytail#thou shalt submit to the ponytail

620 notes

·

View notes

Note

Tumblr user mari-lair I know you have moved on to other (equally beautiful) things aside from the occasional quality post about terkaneaoi BUT can I ASK!! Did you have any ocs of your own for tbhk?? I'm makin my own and I'm pretty scared of interacting with the large-scale fandom but I was just thinking wow I wonder if my favorite tbhk-poster has any thoughts on this,,

Good luck with your OCs! I don't engage much with OC fandom but I do like it. It's a nice and creative way to be self-indulgent/project onto a character/just have fun with new powers/mysteries/comcepts and let everyone know what it's all about from the get go, no canon characterization must be harmed for it either, is a win win. Or it can be an exercise to try to create something that would 'fit' the canon world, the OC possibilities are endless.

I have a few TBHK OCs. At first I only created them to have a role in Your Clock Is Ticking , since we know nothing of teru's classmates and i didn't want to use canon characters as tools with minor roles for my fics, but by now most of my OCs are fleshed out and I love them dearly.

Sugawa Rita was my first proper oc, so she got the honors of having an art

She is 17, a normal girl with no special blood, loves to bake, loves yellow, acts pretty open but is very closed off about her insecurities. She is considered pretty but not 'most hot in school!' type of pretty. She is the love interest of my full supernatural Akane (the name is Aka), since he is dead in the fic, she has no idea.

She is aroace (believes she is pan though), so even if Aka was alive in the fic he would have had no chance.

Shunji is someone I created to get a crush on Teru, but it was so fun to write him that I got attached, to the point I will give him a mini arc in the background where he get a good bf. (rockytye79 made an art of him!!! CHECK IT OUT: HERE )

Tsurai Yamato is an OC I made to be Aoi's dad, because I needed to give the Akane of the fic (who died 30 years before canon so most of the current manga characters weren't even born) a crush. He is a self-destructive mess in every sense of the word, I gave him way more depth than he needs for his role. Made him indeed a pure OC, for I have zero belief canon Aoi's dad would be anything like Yamato.

#here is a crumb of my ocs#i consider Aka an OC too in a way cause just like hanako is very diferent from amane. that ghost that is not akane-

33 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hello, Melancholic!

Yayoi Oosawa

#hello melancholic#yayoi oosawa#manga#mangacap#shoujo ai#yuri#girls love#romance#comedy#school life#band#music#hibiki sugawa#minato asano#monochrome

1 note

·

View note

Text

youtube

Hanakare otome game?! I literally just bought the drama CDs!!! I'm so excited!!! Samudari next pls?🤞🏻

#otome game#hanaemu kare to#hanakare#wataru tori#ginnosuke sugawa#hokuto ichige#tenya minami#ryohei kimura#atsushi tamaru#makoto furukawa#ryota suzuki#otomege#mintlip

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

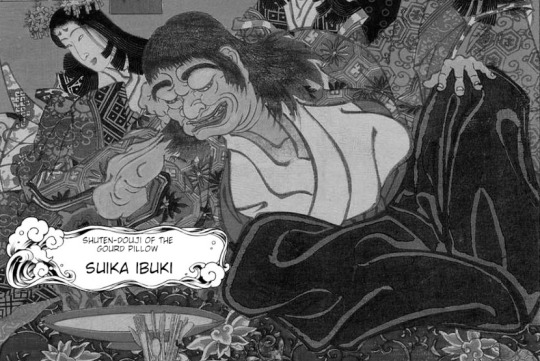

Demon king, demigod, drunkard, dōji: exploring the archetypal oni, from Ōeyama to Lotus Eaters

By popular demand, I wrote an article covering the background of Shuten Dōji and his underlings, and how it influenced Suika’s character and the idea of the Four Devas of the Mountain in Touhou. It was initially scheduled for last month, but I’ve experienced unplanned delays. Read on to learn if you want to learn what Suika has to do with Yamata no Orochi and Mara, if it’s true that oni never lie, and more. I will also explain why making your own fourth Deva of the Mountain is entirely fair game and anyone telling you otherwise is wrong about the source material which inspired ZUN. The article contains some spoilers for WaHH and a number of other Touhou installments, so proceed with caution if that might be an issue for you.

Ōeyama, or Shuten Dōji: origins

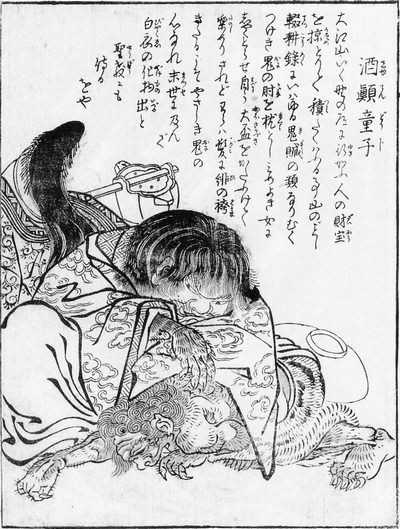

Shuten Dōji, as depicted by Sekien Toriyama in Konjaku Gazu Zoku Hyakki (wikimedia commons)

It perhaps seems a bit silly to start this article with an inquiry into the identity of Shuten Dōji (酒呑童子, “wine-loving youth” or something along these lines). After all, while Touhou characters are often based on obscure figures, Suika is hardly an example of that category. Shuten Dōji is arguably THE archetypal oni, known even to people with limited familiarity with Japanese mythology and folklore. And yet, the matter is nowhere near as clear cut as it might seem at first glance. From a certain point of view, Shuten Dōji might not even exactly be an oni, strictly speaking. A book from Nara simply titled Ōeyama ("Mt. Ōe") offers a detailed account of Shuten Dōji’s origin. His father was not a man or a demon, but rather a mountain god, Ibuki Daimyōjin (伊吹大明神). That’s not all, though - according to a local belief, Ibuki Daimyōjin was actually Yamata no Orochi. How does that even work? Contrary to the more widespread tradition, the inhabitants of the area around Mt. Ibuki from the Muromachi period onward believed that Orochi survived his confrontation with Susanoo and hid in the mountains. That’s actually not even the most unusual variant tradition about Orochi. A widespread belief through the middle ages was that he eventually managed to redeem himself, becoming a divine dragon (shinryū, 神龍) residing in the dragon palace under the sea. In that capacity, he was sometimes associated with emperor Antoku, with the latter even claimed to be his reincarnation, for example in a local legend associated with the Atsuta Shrine, preserved in the noh play Kusanagi. In esoteric Buddhist doctrine Orochi was sometimes perceived as a local manifestation (suijaku) of the buddha Yakushi - much like Susanoo was. Ichijō Kaneyoshi in his Nihon shoki sanso (1455–1457) went into yet another direction, presenting the snake as identical with the naga girl from the Lotus Sutra. Apparently, he specifically means the version of her from Shaku Nihongi… who is identified there as Susanoo’s wife, down to being equated with Kushinadahime (this was not unusual in itself - Susanoo was equated with Gozu Tennō based on similar character, so it was sensible for their wives to be seen as analogous). This effectively created a scenario where Susanoo married his nemesis.

A Japanese depiction of the naga girl offering a jewel to the Buddha, as described in the Lotus Sutra (wikimedia commons)

Anyway, back to Shuten Dōji. According to Ōeyama, Ibuki Daimyōjin, before he even came to be known under this name, fell in love with the daughter of a local feudal lord, Sugawa. He started visiting her at night and she as a result eventually became pregnant. The identity of the visitor was unknown to her father, and out of frustration and fear that nefarious supernatural forces might be involved he eventually contacted various religious officials to perform exorcisms. Needless to say, Ibuki Daimyōjin was less than thrilled, and decided to display his divine wrath through rather conventional means: Sugawa was struck by illness. He once again summoned various Buddhist monks and onmyoji, this time to attempt to heal him. They concluded that the disease will disappear if the deity who caused it is properly honored, and established formal worship of Ibuki Daimyōjin, which apparently did indeed help. Sugawa’s daughter eventually gave birth to Ibuki Daimyōjin’s child. The child started to cause problems at the age of three: his love of alcohol manifested for the first time, earning him the moniker of Shuten Dōji. By the time he was ten, his misdeeds were too much for his family to bear with and his grandfather decided to send him to Mt. Hiei to become a novice (chigo). The monastic lifestyle didn’t really change much though, and Shuten Dōji continued to drink. Eventually he managed to convince three thousand monks (sic) to drink with him and to join him in an “oni dance” during which everyone put on masks representing demons. The festivities lasted seven days. When Shuten Dōji woke up afterwards, he realized his mask had fused with his face, and he was no longer able to take it off. The other participants fled out of fear of his new form.

Shuten Dōji’s Mt. Hiei career was subsequently cut short by Saichō, the founder of the Tendai school of Buddhism. After learning what happened, he prayed to the buddha Yakushi and to Mt. Hiei’s protective deity Sannō Gongen to banish Shuten Dōji. It's worth pointing out that presenting young Shuten Dōji and Saichō as contemporaries is basically standard, and pops up in multiple legends. There are variants where Kūkai, the founder of Shingon, plays a similar role instead, to. They actually lived some 200 years before the other historical figures who appear in Shuten Dōji narratives, but this is not an oversight. It is a given that a partially divine being would live for much longer than a human.

A Heian period portrait of Saichō (wikimedia commons) As a result of Saichō’s success, Shuten Dōji had to flee. He tried to return to his grandfather’s residence, but this was no longer an option for him. He temporarily hid on Mt. Ibuki, but eventually left for Mt. Ōe, where he finally became a veritable "demon king".

The reason why Shuten Dōji was rejected by his family is that he was recognized as an “oni child” (鬼子, onigo). In the folkloric sense, this term refers to supernatural beings which are nonetheless partially human by birth. Not necessarily part oni, though. Another well known onigo, Sakata no Kintoki, was the son of a yamauba, for instance. However, Yanagita Kunio noted that this term also referred to children born with teeth (a real, though very uncommon phenomenon), who were believed to turn into oni - much like how Shuten Dōji did. He states that especially before the Edo period this lead to cases of child abuse or outright murder. In some cases sending the child to become a member of Buddhist clergy was seen as a remedy. For example, a twelfth century monk named Jōjin in a letter relays that he suggested this to the mother of such a newborn. It is not hard to see that Ōeyama likely consciously references this custom.

The other origin of Shuten Dōji

Yet another tradition is preserved in a variant of the standard Shuten Dōji tale which switches the location of his demise from Mt. Ōe to Mt. Ibuki: here Shuten Dōji is not just any demon, but a manifestation of Mara. As in, the opponent of the Buddha and demon king of the sixth heaven, not some other accidentally similarly named figure.

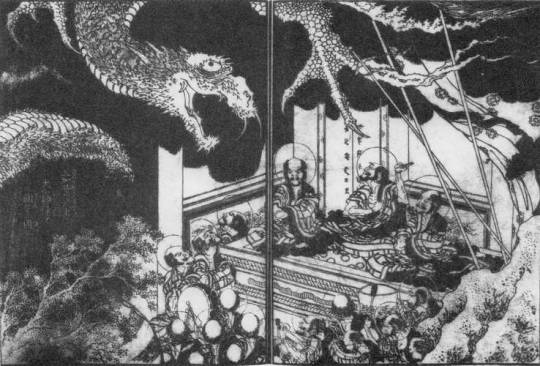

Mara, as depicted by Hokusai in Shaka-goichidai-zue (wikimedia commons)

It is presumed that this portrayal of Shuten Dōji might be tied to medieval Japanese traditions pertaining to Mara. They might sound unusual today: he was both a “demon king” (魔王) obstructing enlightenment, as expected, but also a jinushi (地主), or “landholder deity”. From the Buddhist point of view, jinushi were ambivalent figures: on one hand, their presence was responsible for bestowing specific locations with holiness. On the other hand, they could resist Buddhism as demonic forces, and had to be subjugated or converted to prevent that. Mara was the ultimate jinushi, the king of the world as a whole. A role already attributed to him in earlier Buddhist sources was basically adjusted for this framework. The jinushi version of Mara originated among proponents of the imperial court and mainstream Buddhist institutions, but it curiously also gained traction among the opponents of these structures. Mara became somewhat of an anti-establishment icon more than once, essentially. A legend links him with (in)famous rebel Taira no Masakado (who you may know from SMT) for this reason.

Masakado, as depicted by Kunichika Toyohara in Sen Taiheiki Gigokuden (wikimedia commons)

Other similar examples are also known. A local legendary figure from the Tsugaru peninsula in modern Aomori prefecture, Tsugaru Andō (津軽安藤), who after a failed rebellion fled to Hokkaido, was proudly described as a vassal of Mara by local officials who claimed descent from him. Prince Sutoku, a banished opponent of emperor Go-Shirakawa, swore a vow to become like Mara. Oda Nobunaga famously referring to himself as the “demon king of the sixth heaven” in a letter to Takeda Shingen is likely another example. Reportedly a related belief that praying to the jinushi version of Mara can spare one from conscription persisted as late as the early 20th century, though generally he belongs to the realm of “medieval myths” which faded with the ascent of a new system of values in the Meiji period, in which the early imperial chronicles were favored. Even though it is largely forgotten today outside of specialized scholarship, there is much more to this Mara tradition. It led to the development of one of my favorite Japanese myths with no popcultural reception, but you will have no wait a few more weeks to learn more. It has been argued that behind the identification of Shuten Dōji and Mara might reflect a historical event of the sort which led to associating the latter with figures such as Masakado. In other words, that Shuten Dōji in this case might be less a demon and more a demonized form of some opponent of imperial or religious authorities.

It has been argued that the Ibuki version was the result of combining an original oral narrative, a precursor of the textual versions we are familiar with today, with the memory of the death of a certain Kashiwabara Yasaburō, a bandit leader, in 1201. It has in fact been argued that even the mt. Ōe version might simply be a particularly fabulous reinterpretation of a punitive mission against bandits robbing and murdering travelers. Such rationalist explanations are not exactly new - Ekken Kaibara already argued in the Edo period that the legend of Shuten Dōji must have been the reflection of the downfall of a real bandit who perhaps wore the mask of an oni while committing robberies.

It’s important to bear in mind to not go overboard with this speculation, though. Ultimately the Mt. Ibuki version has a more pronounced religious character than other variants in general: Shuten Dōji’s nemesis Raikō’s is identified as a manifestation Bishamonten or Daiitoku Myōō (in the latter case, Bishamonten and the three other heavenly kings correspond to his four retainers), emperor Ichijō with Miroku (Maitreya), and Abe no Seimei, who plays a minor role in vanquishing the demon, with Kannon. These equations reflect the idea of honji, or “true nature” of Buddhist figures, who were believed to take various guises through history to help people reach nirvana, for example these of local deities or historical figures. The best known example of application of this doctrine in Japanese Buddhism is obviously the historical phenomenon of honji suijaku, which was focused specifically on kami.

A Kasuga mandala representing the correspondences between Buddhist figures and local kami (source; reproduced here for educational purposes only)

The legend of Shuten Dōji

Regardless of which mountain is identified as the residence of oni, and of whether the dramatis personae are identified with Buddhist figures or not, the plot of the various versions of the legend of Shuten Dōji surprisingly does not vary all that much. While it is reasonably well known, I figured it won’t hurt to summarize it here anyway, especially since the information above should make it possible to view it from many new angles.

The oldest surviving version, Ōeyama Ekotoba (“Illustrations and Writing of Mt. Ōe”), presumably based on preexisting oral sources, comes from the fourteenth century, specifically from the Nanbokuchō period. However, the story only reached the peak of its popularity a few centuries later, in the Edo period. This was a part of a broader phenomenon: preexisting tales about warriors matched the sensibilities of the new ruling classes and were kept in circulation by them, but eventually they also became a part of urban popular culture. Many adaptations were produced, including noh plays and ukiyo-e. To put it very colloquially, the heroic warriors and demon quellers from the previous periods became the Edo period counterpart of contemporary superhero media. This is a genuine comparison employed in scholars, for clarity, not a joke. As remarked by Bernard Faure, the most widespread version is basically framed as if it was a tabloid story from the Heian period. In 995, young women (and in some versions men too) disappear whenever a particularly violent storm occurs, and nobody knows how to stop it. Not even the power of Buddhist exorcisms is enough. Seeing as in the portrayed time period that was pretty much the universal solution to supernatural problems, this is a big deal.

Abe no Seimei (right) in the Fudo Rieki Engi (wikimedia commons) This is a source of distress for a certain official, Ikeda Kunikata (or, in some version, Kunitaka), whose only daughter is among the kidnapped women. He decides to seek the help of the Heian period superstar Abe no Seimei, arguably the most famous onmyoji in history. Alternatively, the expert contacted is a certain Muraoka no Masatoki, who to my best knowledge is a fictional character and doesn’t appear anywhere outside of some variants of this tale. Either way, thanks to this intervention it is possible to identify the culprit as a demonic being residing on Mt. Ōe (or alternatively on Mt. Ibuki). In one of the versions featuring Seimei he specifically identifies him as a tenma (天魔), “heavenly demon” - a term commonly used to refer to tengu (as ZUN does in Touhou) and to servants of Mara (overlapping if not identical categories, really; stay tuned for a future article exploring this). However, onmyoji arts are not enough to stop the crisis; all Seimei can guarantee is that Kunikata’s daughter will survive, but he has no way to confront the demon directly. Kunikata therefore decides to bring the case to the attention of the emperor, Ichijō. He holds a meeting with various ministers, who note that in the past a similar case was solved by Kūkai (recall his already mentioned association with Shuten Dōji). However, there are no monks of equal skill left, so his feat cannot be repeated.

It is then concluded that the only way to end the demon’s reign of terror it is to send the strongest warrior they were aware of, Minamoto no Yorimitsu (Raikō) and his four retainers, Watanabe no Tsuna, Sakata no Kintoki, Taira no Suetake, and Tairi no Sadamitsu, on a mission to kill him. Raikō is also assisted by Fujiwara no Yasumasa (Hōshō) and his anonymous attendant, but these two never gained much prominence as characters in this narrative. Additionally, in some versions other figures from the same period - Taira no Muneyori, Minamoto no Yorinobu (Raikō’s younger brother) and Taira no Korehira - are namedropped as potential candidates considered by the emperor, but they all reportedly decline to partake out of fear.

Raikō and Kintoki, as depicted by Yoshitoshi Tsukioka (wikimedia commons)

Preparations started with prayers in Sumiyoshi, Kumano, Kasuga and, in some versions, Hie shrines. They did not go unanswered. Raikō and his retainers subsequently encounter a group of shugenja (mountain ascetics) who turn out to be the manifestations of the deities they paid honor to: Sumiyoshi Myōjin, Kumano Nachi Gongen, Hachiman (here addressed as a bodhisattva) and, if the Hie shrine is included in a given version, Sannō Gongen. They explained that to safely enter the fortress of Shuten Dōji, Raikō and his men must disguise themselves as shugenja (that’s because the legendary first shugenja, En no Gyōja, famously had an entourage of demons). They also provide him with supernatural wine. They state the oni will inevitably drink it due to their fondness of alcohol, only to end up poisoned as a result. In some versions they vanish afterwards, but in others they continue to accompany Raikō. The protagonists then encounter a woman washing blood stained clothes. In some versions she is described as elderly, and states she has lived for 200 years as a servant of Shuten Dōji. In the most widespread Edo period version, she is young and says she was only kidnapped a year earlier, though.

Encounter with the woman washing bloody clothes (NYPL Digital Collections) Regardless of her age, she reveals some additional information about Shuten Dōji, though that also varies depending on the version. In some, she explains that he looks like a human during the day, but takes the form of an oni at night. His human form is specifically that of a dōji, literally “child”, but we’ll get back to the full context of this term later. In any case, I think it's safe to say the shape and size changing is where Suika'a ability came from. In another variant, the woman warns the heroes that Shuten Dōji is enraged by Abe no Seimei’s actions, as the onymoji apparently figured out in the meanwhile how to keep the people of Kyoto safe by employing a number of shikigami (a standard part of his repertoire). There are no further stops on the journey, and shortly after the encounter with the woman of variable age Raikō and his men enter the mountainous land of the oni. Especially in the older versions, it’s a place completely out of this world, with all four seasons occurring at once. Once they enter the fortress located there, they instantly encounter Shuten Dōji… and ask him for a place to stay for the night.

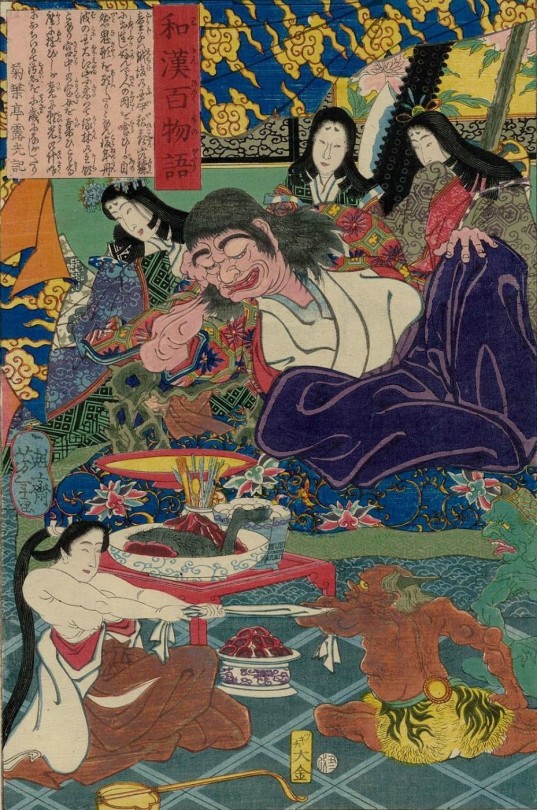

Distinctly human-like Shuten Dōji, as depicted by Yoshitoshi Tsukioka in One Hundred Ghost Stories from China and Japan (LACMA; reproduced here for educational purposes only)

Rather unexpectedly, he instantly agrees. He then tells them about his past; this largely a shorter version of the legend already discussed earlier, though with nothing predating the Mt. Hiei section mentioned. We also get a specific date for his arrival on Mt. Ōe, 849. This doesn’t last long, though, and soon he invites the protagonists to partake in a feast with him. This is obviously not a regular party, and while the individual versions can be more or less graphic, it is clear that the oni are consuing the flesh and blood of their captives. Despite various horrific sights, Raikō maintains composure. He uses the opportunity the feast presents him with to offer Shuten Dōji the sake he received from the three (or four) deities earlier. As expected, Shuten Dōji gets drunk, and leaves to rest in his chamber.

The other oni continue to party. In some versions, some of them try to approach the protagonists by disguising themselves either as a group of courtly ladies or as a dengaku troupe, but Raikō’s glare is so intense they quickly relent. Eventually all of the oni give up on attempting to engage with the alleged ascetics and end up drunk. That’s when the heroes decide to free their captives. These obviously include the women from Kyoto. However, as it turns out, Shuten Dōji’s rampages actually extended beyond Japan, to India and China, though only captives from the latter area actually appear. Multiple versions additionally mention that one of the prisoners was a young acolyte of the Tendai abbot Ryōgen, who was protected by assorted deities. This doesn’t really come into play in any meaningful way, though. Once everyone is freed, the heroes draw their weapons and enter Shuten Dōji’s chamber.

Sleeping Shuten Dōji (National Museum of Asian Art; reproduced here for educational purposes only)

The protagonists finally witness Shuten Dōji's oni form. He is five jō (around fifteen meters) tall, has fifteen eyes and five horns. His head and torso are red, his right arm is yellow, his left arm is blue, his right leg is white and his left leg is black. This might be a reference to the five elements. Alternatively, he could be described as entirely red, which might either be yet another way to reference his love of alcohol, as in the case of the shōjō, or an indication he was comparable to a “plague deity” (疫神, ekijin). The manifestations of the deities from earlier show up again, this time to hold Shuten Dōji in place so that Raikō can strike. He cuts off his head, but to his shock it rises into the air and starts talking.

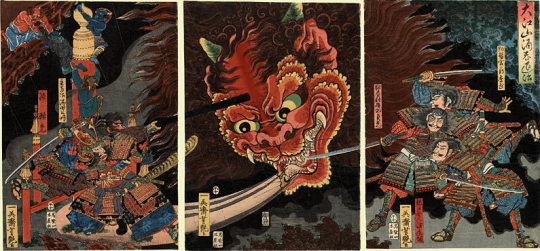

Confrontation between the heroes and the floating head of , as depicted by Yoshitsuya Utagawa (wikimedia commons)

Shuten Dōji actually mocks the heroes: “How sad, you priests! You said you do not lie. There is nothing false in the words of demons.” Needless to say, his final words are pretty directly referenced in Touhou. Oni, at the very least, claim they do not lie. Mileage of course varies, though. ZUN is not the only author drawn to this element of the legend. It would appear that even the Japan Oni Cultural Museum has advertised itself with the words “there is nothing false in the words of demons” in the past. As noted by Noriko T. Reider, emphasizing this apparent honesty (or naivete) sometimes serves as a way to make oni sympathetic or even relatable for modern audiences. However, it's worth noting that in the noh version, Raikō pushes back against Shuten Dōji’s words, and points out even the claim oni do not lie is a lie. He has a point, considering some versions outright establish oni capture their victims by disguising themselves as people close to them, imitating their voices. It probably also should be pointed out that in Konjaku Monogatari, oni are said to be scary precisely because they can tell apart right and wrong.

Anyway, oni ethics aside, it turns out that to kill Shuten Dōji for good, one has to gouge out his eyes. Once that is accomplished, Raikō's mission is finally complete. After killing the other oni, the protagonists take the head with them to Kyoto. Obviously, they also take the freed captives with them. The young women return to their families, and the Chinese men head for the coast to find a ship which could take them home. They promise to let the emperor (the Chinese one, for clarity; that would be Zhenzong of Song in 995) about Raikō's heroism. In the versions where the woman washing clothes was elderly, rather than simply one of the young captives, on the way back the protagonists learn that she has passed away in the meanwhile, since her lifespan was unnaturally extended by Shuten Dōji. Once he died, so did she.

Transport of Shuten Dōji's head to Kyoto (NYPL Digital Collections)

Before the head can enter the capital, a purification ritual has been performed. Abe no Seimei thankfully knows how to do that. Thanks to him, all the relevant authorities can examine it. The emperor decides it will be best to store it in the treasure house of Uji. This location pops up in multiple legends. The severed heads of the two other equally famous malign entities, Ōtakemaru and Tamamo no Mae, were also stored there according to legends focused on them, in addition to various Buddhist relics and mundane treasures. In an alternate version, the head never reaches the imperial court. Raikō and his retainers encounter the bodhisattva Jizou, who tells them it is too impure to be shown to the emperor, and suggests burying it. The location selected, a hill on the northwestern limits of the city, came to be known as Kubizuka (首塚), literally “head tumulus”. Shuten Dōji actually came to be enshrined there as Kubizuka Daimyōjin (首塚大明神), and in this divine guise developed an association with learning and ailments of the head.

The Kubizuka shrine in 2019 (wikimedia commons)

There is yet another variant tradition about the final fate of Shuten Dōji: after his death he became a vengeful spirit, and then turned into a tsuchigumo, just to be defeated by Raikō and his retainer Tsuna for a second time.

Raikō and Tsuna battling tsuchigumo, as depicted in Tsuchigumo no Sōshi Emaki (wikimedia commons)

Interestingly, it has been argued the tale of Shuten Dōji was at least in part based on that of the tsuchigumo Kugamimi no Mikasa (陸耳御笠), who resided on Mt. Ōe according to Tango Fudoki Zanketsu (丹後風土記残欠). The tale is not preserved fully, though, so all we know for sure other than the location is that the hero opposing him was Hikoimasu no Miko (日子坐王), a stepbrother of emperor Sujin (he is also attested in other sources). A second tsuchigumo, Hikime (匹女) is successfully defeated, but the fate of Mikasa is left unspecified in the surviving sections. This obviously makes further comparisons difficult. The topic of tsuchigumo cannot be dealt with here due to space constraints, but I promise I will return to it in a future article.

The supporting cast of Shuten Dōji

Shuten Dōji in his human form and his oni henchmen (NYPL Digital Collections)

Something that requires further discussion is the matter of the underlings of Shuten Dōji, since it is a topic directly relevant to Touhou. You might have noticed I actually avoided referencing them in any meaningful capacity in the summary of the legend. That’s because they actually do not play a major role. There also wasn’t any consistent view regarding their number or names. However, the version which came to be standard in the Edo period lists four of them - an obvious mirror of Raikō and his entourage. As a matter of fact, both groups even share the same moniker, Four Heavenly Kings.

This idea predates the Edo period, though. An earlier variant based on picture scrolls created by Kanō Motonobu already lists four servants of Shuten Dōji: Gogō, Kiriō, Ahō, and Rasetsu (yes, an oni named Rakshasa). However, two additional oni at his service are also listed, Kanakuma Dōji and Ishikuma Dōji. They are described as his personal guards, and as, well, dōji. It is clear the term is used in a literal sense here - they are said to look like “overgrown adolescents”. Two different subordinates are mentioned in another picture scroll: Kirinmugoku (麒麟無極) and Jakengokudai (邪見極大). However, they do not receive any characterization, or even physically appear in the narrative. Shuten Dōji shouts their names when he is about to die, and the very assumption that he’s referring to his oni subordinates is conjectural. The same version states that there were at least ten oni in the fortress so it’s not like it’s an implausible assumption.

The group of four oni returns in the standard Edo period version, where their names are Hoshikuma (“Star-bear”) Dōji, Kuma (“Bear”) Dōji, Torakuma (“Tiger-bear”) Dōji and Kane (“Iron”) Dōji. There’s also a fifth oni who is not a member of the group of 4, but shares the same naming pattern, Ishikuma Dōji. He actually gets a handful of lines, though they do not really provide him with much of a character beyond establishing he likes sake, that he eats humans, and that he is loyal to Shuten Dōji. Kane Dōji also gets a single line… explicitly alongside Ishikuma and multiple other nameless oni, though, and it boils down to announcing they will go down fighting because without their leader they no longer have a place to go.

Defeat of the oni (NYPL Digital Collections)

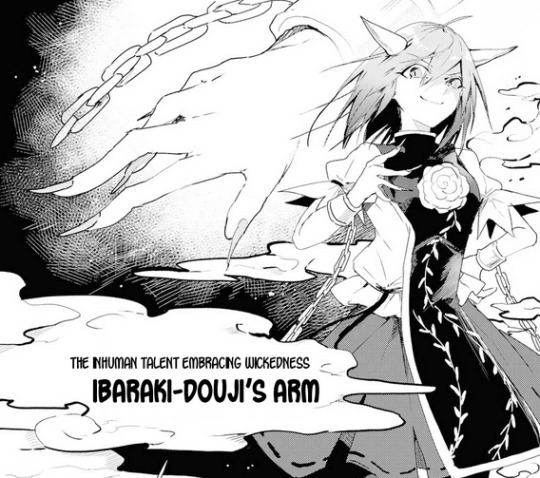

Ibaraki Dōji: Shuten Dōji’s only equal?

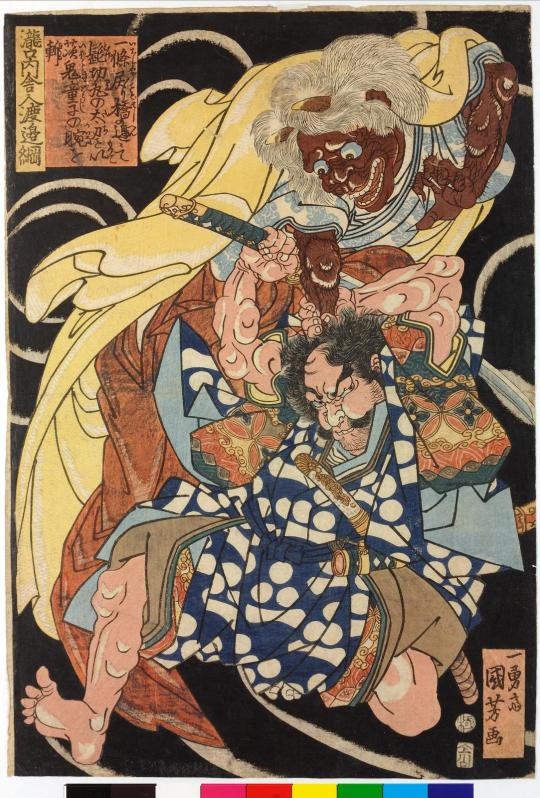

Watanabe no Tsuna battling Ibaraki Dōji (wikimedia commons)

A further unique case is that of Ibaraki Dōji, who actually acquired some fame as an individual character, and today is sometimes cited as an example of an oni equally archetypal as Shuten Dōji. Despite being portrayed as a close associate of Shuten Dōji, Ibaraki Dōji to my best knowledge isn’t counted among the Four Heavenly Kings in any version. The character of the connection is evidently more nebulous. I know an assertion that a tradition presenting Ibaraki Dōji as Shuten Dōji’s wife is attested is repeated as fact on wikipedia and various at least semi-credible websites, but there is never a citation provided, and no version of the narrative covered in articles and monographs I have access to includes such an element. I am not claiming it is impossible, though I do feel the fact it doesn’t come up in any paper or monograph discussing either figure I have access to doesn’t mention to might indicate it’s either a recent reinterpretation or a very obscure local variant. Note this is not meant to be an argument against any Touhou ships. What I can say with certainty is that Ibaraki Dōji’s gender is actually a matter of occasional academic dispute. In the versions of the basic Shuten Dōji narrative which mention this oni, he is pretty firmly male. However, he is said to be capable of taking the form of a woman. Noriko T. Reider argues that on this basis it can be effectively assumed that at the very least this specific oni can be considered genderless or capable of freely changing their gender, though she tentatively extrapolates this ability to oni in general. While Ibaraki Dōji’s gender changing adventure is technically its own legend, a reference to it was incorporated into the basic Edo period version of the Shuten Dōji narrative. During the feast, the latter mentions in passing that the former, his trusted ally, lost his arm in a fight with Watanabe no Tsuna during one of their Kyoto raids, after failing to abduct him while disguised as a woman. He clarifies that the arm was later recovered, but not particularly many details are provided. The rivalry between Tsuna and Ibaraki Dōji subsequently comes into play after Shuten Dōji’s death, when the protagonists are about to exterminate the other oni. Ibaraki charges him and they two fight without a clear winner for a while, until Raikō intervenes and kills the oni. I would argue that despite him being responsible for dealing the killing blow, it is Tsuna who should be considered Ibaraki’s nemesis, though. Interestingly, at some point ZUN considered featuring a character based on him in Wild and Horned Hermit (source). That obviously did not come to pass, though. Tsuna already fights an oni in Heike Tsuruginomaki, and many other variants of the story were written subsequently, with the noh play Rashōmon being the most famous. Curiously, the oldest version makes no reference to Shuten Dōji, and the oni actually resides on Mt. Atago, but by the Edo period the two were regarded as allies operating from Mt. Ōe. The details are otherwise generally similar across all of the sources. Raikō sends Tsuna on an errand. He encounters a woman on the Modoribashi Bridge in Kyoto, but as soon as he offers to take her with him she turns into an oni. Thinking quickly, he cuts off the creature’s arm, which is enough to make them flee. He keeps the severed limb as a trophy. Some time later, he is visited by an old woman who he assumes is his aunt... but who turns out to be the same oni, who uses a brief moment of confusion to recover the arm and fly away.

Transformed Ibaraki Dōji, as depicted by Tsukioka Yoshitoshi (wikimedia commons)

The legend of Ibaraki Dōji was evidently reasonably popular in the Edo period, and could even be utilized to comedic ends. One example is an Edo period satirical pamphlet, Thousand Arms of Goddess, Julienned: The Secret Recipe of Our Handmade Soup Stock, written by Shiba Zenkō and illustrated by Kitao Masanobu. Here the one-armed Ibaraki Dōji is one of the figures interested in leasing one of the now detached additional arms of the Thousand-Armed Kannon, who has apparently fallen in dire straits (“business slumps are inevitable, even for a Buddha”, comments the narrator, alluding to the financial conditions of the 1780s). As we learn, after making a purchase Ibaraki is disappointed by the lack of hair, and promptly hires a craftsman to add it:

Original translation by Adam L. Kern; reproduced here for educational purposes only. I am not responsible for the typesetting.

In my recent Ten Desires article I’ve already discussed the oni of Rashomon as a character in legends about Yoshika no Miyako, which I won’t repeat here. It will suffice to say that this conflation effectively made Ibaraki a penchant for poetry and fine arts, and that it indirectly put him in the proximity of the pursuit of immortality. Whether this is why ZUN made Ibaraki’s counterpart a wannabe immortal (“hermit”) is difficult to ascertain, but it does not strike me as impossible. The oni of Rashomon actually appears in at least one more legend which similarly portrays him as an enthusiast of the arts, though to my best knowledge this one never came to be reassigned to Ibaraki Dōji. It is centered on a famous biwa player, Minamoto no Hiromasa, who has to resolve the case of mysterious theft of an instrument from the imperial palace. As you can expect, it is revealed to specifically be an exceptional biwa, which bears the name Genjō. Hiromasa surveys the city in hopes of finding it, and eventually hears its distinct tones while passing near the Rashomon gate. He quickly realizes an oni is playing it. He politely asks if he can have it back, since it’s a treasure of the imperial court… and the oni eagerly obeys, thus bringing the story to a happy end. However, we are told Genjō acquired supernatural qualities in the aftermath of the theft, and only played when it felt like it, as if it was a living being. There is a variant which reveals that the oni of Rashomon was in fact the ghost of Genjō’s original maker, a craftsman from India. In this version, Abe no Seimei has to intervene to recover it, and the oni only agrees to return it after being promised a night with a woman he fell in love with who resembles his deceased wife. There is no happy ending here, though, as the woman’s brother convinces her she needs to kill the oni. She fails, and meets such a fate herself instead. It seems that the reader’s sympathy is actually supposed to be with the oni in this case.

Conclusions, or why you should make your own Deva of the Mountain

Obviously, there is nothing novel or clever about stating that the two figures this article is focused on, Shuten Dōji and Ibaraki Dōji, correspond to Suika and Kasen respectively. You can learn that from the official media itself, after all. Funnily enough, it seems this might have been even more blunt, judging from unused ideas for referencing the legend to an even greater degree in WaHH, with the defeat at Mt. Ōe as the explanation why oni reside… well, elsewhere (source). Granted, it would also be a disservice to ZUN to say he only created anime girl versions of the classic oni. He effectively created his own versions of both Shuten and Ibaraki - for every similarity between the irl background I’ve described and Touhou, there is also something brand new. That is part of what makes Touhou compelling, I would argue. Naturally, the fact that the group Kasen and Suika belong to is referred to as the Four Devas of the Mountain shows clear inspiration from the Edo period version of the original legends. However, Suika and Kasen are counted among the four, which is obviously an innovation. Additionally, while Yuugi is naturally named after Hoshikuma Dōji, who you were able to meet earlier, save for the name she is effectively a fully original character. Her ability references the Analects of Confucius, rather than anything directly tied to Shuten Dōji. And, on top of that in all honesty, she has more character than any of the additional oni appearing in the real legends. ZUN, as far as I am concerned, created a more than worthy addition to the classics. What about the much discussed fourth deva? I think it’s safe to say that in the light of the discussed material there simply isn’t a single most plausible option. As I stressed already, there’s no consistent group of oni appearing alongside Shuten Dōji, and it cannot be said that the Edo period version is clearly what should be treated as true in Touhou. ZUN picked what he liked from many versions. For what it’s worth, so far all of the oni forming the Four Devas are based on those who share the moniker of dōji, so that’s the closest we have to a theme. As I already said earlier, this term can be simply translated as “child” (or “lad”, though I think a gender neutral option is more apt since we are talking about Touhou here, ultimately). However, it has a more specific meaning when applied to supernatural beings. In this context it refers to a category of ambiguous figures characterized by “vitality, (...) hubris, and (...) unpredictability”, as well as fondness of violence, as summarized by Bernard Faure. Shuten Dōji, and by extension his underlings, are obviously the dōji par excellence. However, the term could also be applied to benevolent, or outright divine beings. That, however, goes beyond the scope of this article. I personally think despite the possible dōji theme the fourth slot will never be filled, ultimately. ZUN likes leaving gaps in established groups - there are types of tengu which were a part of the background for well over a decade, for instance. I think these are left as paths to make ocs with an instant excuse to interact with canon characters. Despite ZUN’s generally pro-fanwork stance I do not think I’ve ever seen anyone make this point. As far as I am concerned, the conclusion is clear: it’s entirely fair game to invent characters to fill the empty spot. There’s even a solid case to be made for reinventing oni from other legends as members of the Four Devas - remember that much of Ibaraki Dōji’s character was borrowed from a nameless oni from a legend about the Rashomon gate, as I discussed last month.

Bibliography

Bernard Faure, Rage and Ravage (Gods of Medieval Japan vol. 3)

Michael Daniel Foster, The Book of Yokai. Mysterious Creatures of Japanese Folklore

Adam L. Kern, Thousand Arms of Goddess, Julienned: The Secret Recipe of Our Handmade Soup Stock, written by Shiba Zenkō and illustrated by Kitao Masanobu (translation and commentary), in: An Edo Anthology: Literature from Japan’s Mega-City, 1750–1850

Keller Kimbrough and Haruo Shirane (eds.), Monsters, Animals, and Other Worlds. A Collection of Short Medieval Japanese Tales

Irene H. Lin, The Ideology of Imagination: The Tale of Shuten Dōji as a Kenmon Discourse

Michelle Osterfeld Li, Human of the Heart: Pitiful Oni in Medieval Japan in: The Ashgate Research Companion to Monsters and the Monstrous

Noriko T. Reider, Shuten Dōji: "Drunken Demon"

Idem, Japanese Demon Lore

Idem, Seven Demon Stories from Medieval Japan

also check out the scans of an amazing Shuten Dōji picture scroll from the NYPL collection here!

173 notes

·

View notes