#strange behaviour (1981)

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

SUMMARY: A scientist is experimenting with teenagers and turning them into murderers.

#strange behaviour (1981)#slasher#science fiction#1980s#new zealand#oceanian movie#mentionable warning#suicide#child death#horror#movie#poll

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Now Playing...

Artist: Jane Kennaway & Strange Behaviour

Title: IOU

Album: IOU

Played on: Thu Dec 12 2024 08:02:33 GMT-0600 (Central Standard Time)

#Jane Kennaway & Strange Behaviour #1977 to 1981 ERA OF MUSIC

#Jane Kennaway & Strange Behaviour#1977 to 1981 the era of music#80s#80s music#power pop#picture sleeve#80s power pop#1980#beware the siren

0 notes

Text

Now Playing...

Artist: Jane Kennaway & Strange Behaviour

Title: IOU

Album: IOU

Played on: Thu Dec 12 2024 07:59:52 GMT-0600 (Central Standard Time)

#Jane Kennaway & Strange Behaviour #Female Fronted #BEWARE THE SIREN

#Jane Kennaway & Strange Behaviour#beware the siren#female fronted#80s#80s music#picture sleeve#80s power pop#1977 to 1981 The Era Of Music

0 notes

Text

Vampires were an extinct human subspecies, discovered and then de-extinct through morally questionable genetic engineering research in the year 1981 by The Genomic Innovation Institute (or G.I.I) in an attempt at finding cures for some neurological disorders through gene therapy and tweaked retroviruses. Thanks to these… Morally questionable experiments, It was discovered that some specific dormant genes were extremely widely spread throughout the population and that these genes could be reactivated in some individuals. In certain cases some of these genes express spontaneously. This gave rise to the theory that some neurological disorders could at least partly arise from the expression of these genes albeit in a very “broken” and rudimentary form. Essentially the treatments to cure certain types of neurological disorders turned out to activate some of these dormant genes, essentially turning the test subjects into what we now call a Vampire. The Genomic Innovation Institute decided to pursue research on this subspecies, hoping to turn a profit. Thanks to them, we now have a complex understanding of Vampires…

They were humanity's natural predator, emerging between 300,000 and 200,000 years ago, around the same time as Homo sapiens, or at least shortly after. They hunted our ancestors with brutal efficiency, to the point that even though we eventually forgot about them (before bringing them back from extinction), they remained engraved in our cultural memory. For lack of better words, they were the things we feared were in the dark.

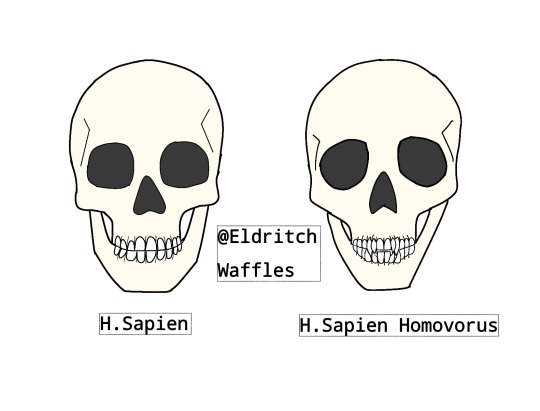

It's difficult to identify ancient vampire remains, as their identifying traits are primarily neurological and soft tissue-related. However, their skeletal structure does have some minor differences, which allow for identification now that we know what to look for. It seems that vampires began going extinct around 2000 BCE, with their population drastically reducing as civilization emerged. Their extinction was due to more than one factor.

-Vampires were extremely antisocial, which makes sense for a predatory species whose prey resembled it that much. This however did complicate mating between vampires because vampires didn't just tend to ignore each other but would see other vampires as threats and would often attempt to dispatch each other upon contact. Since sexual dimorphism is quite lacking in Vampires, which not only resulted in both of the sexes looking very androgynous, it also meant that both Male and Female had essentially the same musculature and strength and general ferocity, sexual coercion would have most likely resulted in one or both of the party's demise or heavy maiming, rendering it extremely inefficient. Plus, vampires seemed to generally be very uninterested in copulation, though it did happen from time to time. Strangely enough all of this seemed to have made the idea of mating with humans more appealing for some Vampires which is why like with Homo Neanderthal, Vampiric DNA can be found in modern day humans. (The mating behaviours of Vampires will be discussed more thoroughly in another chapter)

-The Emergency of euclidean architecture seemed to have greatly affected vampires. We discovered that in their eyes, the receptor cells that respond to horizontal lines are cross wired with those that respond to vertical ones. When both are fired simultaneously in a specific way it'll result in quite a violent seizure. We call the effect “The Crucifix Glitch”. While the glitch will only trigger when intersecting right angles occupy more than 30° of visual arc, we discovered, thanks to our currents subjects, that the simple suggestion of the Crucifix Glitch being triggered is enough in 75% of cases to completely dissuade an attack, if they had been exposed to it previously (depending on the vampire's current emotional state). These seizure are quite violent, reminiscent of Tonic-Clonic seizures, but because of the vampire's particular muscular structure and their higher distribution of fast twitch muscle fibers, these seizures tend to result in dislocated limbs much more often than regular seizure. Plus, with the Vampire's unique neurochemistry, we suspect that the seizures are much more distressing for them. In conclusion, the seizures caused by the Crucifix Glitch are extremely traumatizing and painful for vampires to the point that any right angles, even if not in a context that could induce the glitch, will usually make a vampire extremely uncomfortable and anxious (work best if they've been exposed to the glitch at some point in their life). Because of this a lot of the vampires did not even dare to approach human settlements with euclidean architecture, which greatly complicated things for the overall survival of the species.

-Vampires make for terrible parents. Given their natural antisocial behaviour, it’s unsurprising that they aren’t the best caregivers. Despite their longer lifespans, one might expect them to invest more time and effort in their offspring, but this is not the case. In fact, it’s quite the opposite; their longer lifespans and fertility lead them to essentially not value their offspring, as they can always have another later on in life. The father is most likely going to be completely absent, as he typically feels no compulsion to ensure the survival of his offspring. The mother, on the other hand, while interested in her child's survival, is not as invested as one might expect from a primate species. She won't hesitate to abandon her offspring if she considers it a liability. She'll usually take care of it up until it's pre teenage years where she'll abandon it. However, some exceptions to this were found, as we've recently found proof of a Vampire Pack, more on this in a later entry.

-Mating with humans: As previously mentioned, vampires tend to be awful parents, to the extent that some began mating with humans. Why? Because it was easier. Human mating rituals were simple for vampires to emulate, and once mating was complete, the male vampire could leave, confident that its offspring would be cared for. Meanwhile, the female vampire could stay with the human and be looked after during her pregnancy, a wolf in sheep's clothing, she could discreetly sustain her need for blood by feeding on humans in the tribe or even her mate. Once she gave birth, she could either leave or continue caring for her children with a continuous blood supply. Another tactic vampire would use to get out of raising their young is “Brood Parasitism”. They would kidnap human children and replace them with their own. We believe that this is what gave birth to the legends of “Changelings”.

Overall the extinction of Vampires wasn't due to one reason but a combination of many things. A reminder of how evolution might screw you over. You may have been a perfectly adapted predator but something seemingly insignificant can truly come back to bite you.

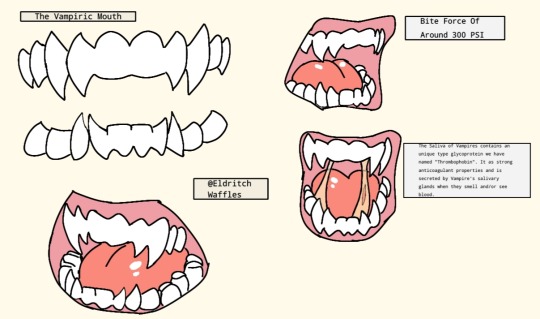

Speaking of biting, the infamous bite of Vampires while not exactly as described in myths, is nothing to joke about...

This is from a setting of mine, where alot of cryptids, myths, etc are real or were directly influence by real events/creatures all explainable by science, kinda like the amazing YouTube Channel ThoughPotato This entry focuses on Vampires which biology and history is inspired and influenced by the Amazing Peter Watts and his just as amazing books Blindsight and Echopraxia (in fact this setting started out as a AU of his awesome universe)

#horror#horror setting#science fiction#science fiction writing#scifi#science horror#stories#writers of tumblr#blindsight peter watts#blindsight#echopraxia#vampire#vampirism#peter watts#weird fiction#my art#my artwork#speculative evolution#speculative biology#horror writing#horror writer#my writing

29 notes

·

View notes

Note

Idk, Remus was this kid who knew nothing but prejudice and isolation before Hogwarts, my lukewarm take is not that he was in with the prank nor that Sirius broke his heart and trust forever for revealing his secret.

I think young and dumb teenage Remus, riding the high of his young and dumb friends already overlooking the gravity of his condition by hanging out with him as animals, was dumbfounded by the fact that someone thought little of his condition to think the whole thing would be a funny prank. Maybe, in a backwards way to process the whole thing, he also chose to believe it was just that.

Deep down I’d guess the self-hatred only grew, and the same way Snape was scared of him, he was scared of Snape - in SWM, he’s not just ignoring James and Sirius tormenting Snape, he’s paralysed). SWM has got to be after the prank, since he was still talking to Lily when it happened.

I think adult Remus sees things differently, the thing about the prank discourse is there is no resolution. Would Remus ever have apologised sincerely, for dismissing Snape’s pain to defend his friends? Would Snape ever have accepted his apology? Can we admit that, tho Snape was undeniably a victim, he also fostered an unfair bias towards werewolves that can also justify Remus’s bitterness (a bitterness that he’ll forever try to hide).

Idk, just rambling. I’ll be a minority here, defending Lupin, but could be worse, I could be defending Sirius.

i'm not sure i back this - although you and i are certainly aligned on not thinking that the prank ruins lupin's relationship with sirius.

[and also in thinking that his incredibly strange upbringing needs to be taken into account when dealing with his various... idiosyncrasies.]

i just think that the idea that he was afraid of snape - even if only as a teenager - doesn't really stand up. my reading - not only of snape's worst memory but of lupin's assessment of his youth in prisoner of azkaban - is that his self-loathing is connected to two divergent things: the first, that he likes james and sirius' cruelty, recklessness, and danger - and the fact that they go out of their way [literally becoming animagi!] in order to allow him to participate in this - and is ashamed of himself as an adult [after 1981, when james' recklessness gets him killed] for this; the second, that he dislikes james and sirius' cruelty, recklessness, and danger, but is ashamed of himself for never confronting them over their excesses [worried as he is - i think there's a strong case to be made from canon - that james, the man he thinks of as his best friend in the whole world, would side with sirius against him].

he behaves the way he does in snape's worst memory because his friends are - as harry puts it - humiliating someone in the middle of a crowd of onlookers for absolutely no reason. the decent thing to do in such a situation is to try and stop them - but that requires a willingness to risk the ire of one's friends which someone with lupin's life experience [the isolation of his youth making him desperate to cling to any friendship he's offered, no matter how unsuitable - which is very like snape...] doesn't have.

i don't think - to be clear - that lupin's actions are unforgivable. indeed, i think far more of us would behave like him in an equivalent situation than we'd like to admit, and that's something always worth being aware of. but i think that the other side of that coin is that it's fine to state frankly that he acts like a coward when it comes to snape's worst memory. there doesn't need to be a deeper interpretation of his behaviour which makes him appear more sympathetic - he's frozen because unfreezing would mean having to involve himself against james and sirius. and that's something he simply doesn't want to do.

i'm also unconvinced that snape's attitude towards werewolves is unfair. it's striking in prisoner of azkaban that - while snape is terrified of lupin due to his lycanthropy - his primary concern is that lupin is aiding and abetting sirius [who he believes is the death eater who sent voldemort to kill lily - there is no suggestion whatsoever that he knew wormtail was the real traitor] while in human form. he leverages social prejudice in order to bring about lupin's dismissal from his job - since dumbledore doesn't take his concerns about human!lupin seriously - sure... but one of the circles the canon text's worldbuilding never fully squares is that this social prejudice is... completely legit.

lupin is the series' one "good werewolf" - who embraces the "civilising" influence of the wizarding world's social conventions, and is the only werewolf in the series harry, from whose perspective the narrative is written, likes - and so the prejudice he experiences is something the text views as cruel. the prejudice experienced by werewolves like fenrir greyback, on the other hand, is something the text sets up as entirely justifiable. after all, werewolves are dangerous and the mechanisms which exist to reduce that danger are relatively new [lupin says in prisoner of azkaban that the wolfsbane potion is a "very recent discovery"] - being afraid of them is an entirely sensible position, even if one has never almost eaten you.

[which is why jkr's lycanthropy-as-aids metaphor is complete and utter bullshit - and is one of the long list of things she ought to have shut her mouth about.]

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

Stranger Things 4 - Songs We Need!

SELF CONTROL - Laura Branigan (1984)

"...I, I live among the creatures of the night. I haven't got the will to try and fight..."

HIGHWAY TO HELL - AC/DC (1979)

"...Hey, Satan! payin my dues. [...] Hey Momma! Look at me!..."

SOMEBODY TO LOVE

- Jefferson Airplane (1967)

"...Tears are running, they're all running down your breast. And your friends, baby. They treat you like a guest..."

- Queen (1976)

"...I just gotta get out of that prison cell. Someday I'm gonna be free."

BAD MOON RISING - CCR (1969)

"...I know the end is coming soon. [...] I hear the voice of rage and ruin."

I WANT TO KNOW WHAT LOVE IS- Foreigner (1984)

"... I'm gonna take a little time. A little time to look around me. I've got nowhere else to hide. It looks like love has finally found me..."

CALIFORNIA DREAMIN' - The Mamas And The Papas (1965)

"...you know the preacher likes the cold, he knows I'm gonna stay..."

PEOPLE ARE STRANGE - The Doors (1967)

"People are strange when you're a stranger. Faces look ugly when you're alone."

EVERYBODY WANTS TO RULE THE WORLD - Tears For Fears (1985)

"...acting on your best behaviour. Turn your back on mother nature..."

YOU CAN'T HURRY LOVE - The Supremes (1966)

"...how long must I wait? How much more can I take?..."

SMALLTOWN BOY - Bronski Beat (1984)

"...But the answers you seek will never be found at home. The love that you need will never be found at home..."

HOTEL CALIFORNIA - Eagles (1976)

"...we are programmed to receive. You can check out any time you like, but you can never leave..."

KIDS IN AMERICA - Kim Wilde (1981)

"...Much later, baby, you'll be saying never mind. You know life is cruel, life is never kind..."

THE PASSENGER - Iggy Pop (1977)

"...And everything was made for you and me. All of it was made for you and me..."

RUSSIANS - Sting (1985)

"...There is no monopoly of common sense on either side of the political fence..."

DON'T STOP ME NOW - Queen (1978)

"...I am a satellite. I'm out of control..."

BOYS DON'T CRY - The Cure (1980)

"...I tried to laugh about it. Cover it all up with lies. I tried to laugh about it.Hiding the tears in my eyes..."

GHOST TOWN - The Specials (1981)

"...Do you remember the good old days before the ghost town?..."

MIDNIGHT BLUE - E.L.O. (1979)

"...and what you're searchin' for can never be the same, but what's the difference 'cause they say what's in a name?..."

SOS - ABBA (1975)

"...I tried to reach for you, but you have closed your mind..."

BREAK ON THROUGH (TO THE OTHER SIDE) - The Doors (1967)

"...Made the scene, week to week, day to day, hour to hour. Gate is straight, deep and wide..."

HURT SO BAD - Little Anthony And The Imperials (1964)

"...I know you don't know what I'm goin' through. Standing here looking at you. Well, let me tell you that it hurts so bad..."

LIVIN' THING - E.L.O. (1976)

"...Making believe this is what you conceived from your worst day. Oh, moving in line then you look back in time to the first day..."

PAINT IT BLACK - The Rolling Stones (1966)

"...Maybe then I’ll fade away and not have to face the facts..."

I WANT TO BREAK FREE - Queen (1984)

"...It's strange but it's true, yeah: I can't get over the way you love me like you do, but I have to be sure when I walk out that door: Oh, how I want to be free..."

BREAKFAST IN AMERICA - Supertramp (1979)

"...Take a look at my girlfriend. She's the only one I got. Not much of a girlfriend, I never seem to get a lot..."

OWNER OF A LONELY HEART - Yes (1983)

"...Say , you don't want to chance it. You've been hurt so before..."

PSYCHO KILLER- Talking Heads (1977)

"...Don't touch me, I'm a real live wire.."

EVER FALLEN IN LOVE - Buzzcocks (1978)

"...You spurn my natural emotions. You make me feel I'm dirt, and I'm hurt and if I start a commotion I run the risk of losing you, and that's worse..."

PICTURE BOOK - The Kinks (1968)

"...Picture book, of people with each other to prove they love each other..."

MY FAIRY KING - Queen (1973)

"...Then came man to savage in the night. To run like thieves and to kill like knives. To take away the power from the magic hand. To o bring about the ruin to the promised land..."

SPOTIFY PLAYLIST

Blue -> personal favourites

#found this in the drafts folder#tbh I'd love for all the queen songs to appear in season 4#same with the doors#and Jefferson airplane#stranger things#will byers#byler#mike wheeler#stranger things 4#lucas sinclair#erica sinclair#eleven hopper#max mayfield#joyce byers#jonathan byers#steve harrington#dustin henderson#robin buckley#nancy wheeler#jim hopper#murray bauman#byeler#tbh some lyric picks very super hard because some of them just give off 100% stranger things vibes

51 notes

·

View notes

Text

June & Jennifer Gibbons: The Silent Twins

October 28, 2021

June and Jennifer Gibbons were born on April 11, 1963 to Caribbean immigrants Gloria and Aubrey Gibbons. The girls were born identical twins, and most twins have what we know as twin telepathy, having a deep in tune bond and connection that most siblings do not share. The girls were not the only siblings in their family, having an older sister, Greta, born in 1957, and am older brother, David, born in 1959 and a younger sister named Rose.

In 1974, the family moved to Haverfordwest, Wales. June and Jennifer often only spoke to each other, keeping to only themselves and others found it hard to understand what they were talking about.

The Gibbons siblings were also the only black children living in their community, which made them stand out and they were often bullied at school. The twins were bullied quite badly, to the point that they would get permission to leave the school early each day to avoid the other kids who would bully them. It was around this point that the language the girls only spoke to each other that many others couldn’t understand, became their primary way of communicating and they would only talk to each other and their sister Rose.

The girls would often mirror each others movements and could not be physically apart. They eventually stopped speaking to anyone except each other. June and Jennifer would continue attending school though they would never read or write.

In 1974, medics came to give the kids vaccinations and one of the medics noticed June and Jennifer’s odd behaviour and how they only spoke to each other in their own kind of language. Being concerned, the medic contacted a child psychologist which the girls began going to multiple therapists who would try to encourage them talking to other people.

The twins eventually were separated, each getting sent to a different boarding school in an attempt to create some separation and have them engage with other children, however this backfired with the girls becoming more reserved and they completely were withdrawn and possibly even distraught without each other.

When June and Jennifer were reunited after boarding school they spend many years staying in their bedroom, being isolated from life. The twins were both creative, and would pass the time by creating plays and stories and sometimes would record themselves aloud on tape for their sister Rose. Both girls found a passion for writing, despite refusing to at school and both wanted to begin a writing career.

Each girl kept a diary and wrote many poems, stories and novels often stories relating to crimes or individuals who have strange behaviour and engage in criminal activities. June wrote a novel titled “Pepsi-Cola Addict” that was about a teacher seducing a high school hero and who then goes to a reformatory where a homosexual guard makes a play for him.

The twins put together their unemployment benefits to try to get their novel published by a vanity press, after having many unsuccessful attempts at getting published. One of Jennifer’s novels was called “The Pugilist” where a physician wants to save his child’s life so bad that he kills their dog to get it’s heart for the transplant. The dog’s spirit still lives and the child eventually seeks revenge on the father.

When the girls were in their late teens they began to drink alcohol and take drugs, and eventually turned into criminals themselves. In 1981, June and Jennifer would be involved in vandalism, petty theft and arson where they were soon admitted to Broadmoor Hospital, a mental health hospital. The girls stayed at Broadmoor for 11 years and June blamed their long sentence here on their selective muteness later on, saying that most kids who commit crimes would only get a 2 year sentence, but that they got more because they wouldn’t speak.

The girls were made to take high doses of antipsychotic medications which left them unable to concentrate. Jennifer apparently began suffering from tardive dyskinesia which left her making involuntary repetitive movements. These medications apparently were adjusted so that the twins could still write in their diaries however they pretty much lost interest in creative writing during their time in the hospital.

A journalist named Majorie Wallace discovered the twins’ story and thought they were really interesting. She covered a story on them in the newspaper which gained a lot of attention, and even wrote a book on them called “The Silent Twins” which was published in 1986 and why the girls are often referred to this name by many.

Wallace spent a lot of time with June and Jennifer and began to know them quite well. Wallace said the twins had made an agreement that if one of them died, the other one would go on to live a normal life and begin to speak. While they were at the hospital they began to believe that one of them would have to die so that the other could live a normal life, and that Jennifer apparently agreed to make the sacrifice.

On March 9, 1993, the twins were transferred from Broadmoor to the Caswell Clinic and on the way Jennifer collapsed and could not be woken. She died at the hospital from acute myocarditis, which is a sudden inflammation of the heart. Her death truly remains a mystery as she was only 29 years old at the time, just one month shy of her 30th birthday. There was never any drugs or poison found in her system, it was as if she had just died from natural causes.

June admitted that Jennifer had been acting strange the day before and that her speech became slurred and she had told her sister she was dying. When they were on their way to Caswell she had been sleeping in June’s lap with her eyes open. Wallace went to see June a few days after Jennifer’s death and June claimed she was free and that Jennifer gave up her life so she could have this freedom.

After Jennifer died, June was able to live a normal life, speaking and even giving interviews for Harper’s Bazaar and The Guardian. In 2008, she was living a quiet life near her parents in West Wales. She is now accepted by her community and no longer needs mental health services or psychiatrists keeping an eye on her. In 2016, the twins’ older sister, Greta, did an interview and claimed it was Broadmoor’s fault that Jennifer’s health had been failing and that she wanted to file a lawsuit against them, though Gloria and Aubrey refused.

To this day no one knows what caused the twins to become silent, and only communicate with each other, becoming isolated and anti-social from the world. It is a mystery how they figured out that one of them would have to die so the other could live a normal life, and Jennifer’s death in general is a mystery. Many believe that if Jennifer was still alive the twins would still be silent.

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

Dennis Nilsen

Dennis Nilsen was a Scottish serial killer and necrophile who is known to have murdered at least 12 young men and boys between 1978 and 1983 in London, UK.

Born in Aberdeenshire, Scotland to parents in an unhappy marriage, Nilsen was a quiet child. He described his most vivid childhood memory as seeing is grandfather’s body in a coffin. Nilsen had always adored his grandfather and began to withdraw after his death, showing resentment towards his family. During puberty Nilsen discovered he was gay, which confused and shamed him, he kept his sexuality hidden but his older brother teased him for being gay and a ‘girl.’

On 30th December 1978, Nilsen killed his first victim, he invited over and drank alcohol with a teenager before they both fell asleep. The following morning when Nilsen woke up he was afraid to wake the boy in case he left, Nilsen decided the boy was the ‘stay with me over the New Year whether he wanted to to not.’ He strangled him and then drowned him in a bucket, carefully washing the body, putting it on his bed and masturbating over it before storing it under his floorboards for 8 months. He then burnt the body in a bonfire in his garden. In October 1979, Nilsen attempted another murder but his victim fled and after contacting the police did not press charges. 2 months later he killed again, strangling his young victim with his own headphones, the next day he bought a Polaroid camera and photographed the body in suggestive positions before storing the body under the floorboards. On several occasions Nilsen took the body out and sat it next to him when he watched television. Nilsen killed again in May 1980, again keeping the corpse. By the end of 1980 he had killed another 5 victims.

The bodies under his floorboards soon attracted insects and had a strong odour, maggots began to infest. Nilsen attempted to kill the insects and eliminate the smell but could not, he eventually removed and dissected the bodies before burning them disguising the smell by also burning a tyre. He checked for recognisable debris in the ashes and smashed an intact skull with his rake.

Nilsen killed 5 more victims, often taking time off work to be alone with the bodies- dates which were later matched to disappearances. In mid-1981 Nilsen’s landlord decided to renovate the property and Nilsen was asked to vacate, he dissected those bodies before burning the corpses.

After moving Nilsen had no garden or floorboards to store bodies under, he attempted murder multiple times, including one victim who he resuscitated and after Nilsen’s dog licked the victim’s face, allowed to leave even driving him to the train station.

Nilsen killed twice more, as with all previous victims, undertaking strange behaviour with the corpses, flushing the organs of his final victim down his toilet.

The flushed organs were found and a murder investigation was opened, when officers entered Nilsen’s flat they immediately smelt rotting flesh, Nilsen calmly told the officers the rest of the body was in his wardrobe. Nilsen stated “ I'll tell you everything. I want to get it off my chest. Not here—at the police station." When asked whether the remains in his flat belonged to one person or two he replied fifteen or sixteen, since 1978.

Nilsen was sentenced to life imprisonment on 4th November 1983 with a recommended minimum of 25 years, this was later changed to a whole life tariff. He died in prison on 12th May 2018, aged 72.

#dennis nilsen#nilsen#serialkiller#serialkillers#serialkillerblog#serialkillersblog#serial killer#serial killer blog#serial killers blog#crime#true crime#truecrime#truecrimeblog#crimeblog#crime blog#true crime blog#criminol

42 notes

·

View notes

Text

James Maxwell TV/Film List

More of a guide than a recs list, because old tv/film depends so much on availability. It’s also hard as there’s nothing surviving that’s really like SotT for him (his voice is always slightly different, too & rarely the grand one from SotT) - I found it hard to find where to start back in the day, so I hope this makes it easier. However, I have starred my favourites (rated for JM content only).

I’ve divided things into categories and @jurijurijurious (or anyone) can make up their own mind as to what to go for. (Also @jurijurijurious I have NO idea what old telly you’ve already seen, so forgive me if I’m telling you things you already know.)

Where to find it: Luckily in the UK, it’s not too bad! Network Distributing are the DVD supplier to keep an eye on (they do great online sales), you can find secondhand things cheap on Amazon Marketplace & eBay, and several Freeview channels show old TV & film, especially Talking Pictures. I’ll note if things are on YT or Daily Motion, but they come and go all the time, so it’s always worth searching.

***

Film serials (ITC mainly)

British TV made on film in the US mode with transatlantic cash, so generally pretty light, episodic (continuity is almost unheard of) etc. Some turn up on ITV3 & 4 on a regular basis (colour eps).

*** Dangerman “A Date With Doris” (ITC 1964) James Maxwell is a British spy friend of Drake’s (Patrick MacGoohan) called Peter who gets framed for murder. Drake goes to Fake Cuba to rescue him by which time JM is dying from an infected wound and faints off every available surface, including the roof. It’s great. On YT. (The boxset is v pricey if you just want 2 eps.)

“Fair Exchange” (ITC 1964) JM is a German spy friend of Drake’s called Pieter who helps him out on a case. Not as gloriously hurt/comfort-y as the other, but it does have some excellent undercover dusting. (Why Patrick MacGoohan has JM clones all called variations on Peter dotted around the globeis a mystery.) On YT.

The Saint “The Inescapable Word” (ITC 1965) This is pretty terrible, but entertaining and James Maxwell plays the world’s most hopeless former-cop-turned-security guard. With bonus collapsing. On YT.

“The Art Collectors” (1967). JM is the villain of the week. It does include a v funny bit, though, where the Saint (Roger Moore) goes for JM’s fake hair (and who can blame him? How often I have felt the same!) This one’s in colour so should pop up on ITV3 or 4.

The Champions “The Silent Enemy” (ITC 1968). Surprisingly good JM content as the villain of the week who drugs sailors and steals their clothes before realising that maybe he should have worked out if he could operate a sub before he stole it.

The Protectors “The Bridge” (ITC 1974, 30 mins.) Not worth seeking out on its own, but ITV4 seems fond of it and James Maxwell gets to do some angsting and wears purple, so it’s worth snagging if you can, but too slight otherwise.

*** Thriller “Good Salary, Prospects, Free Coffin” (ITC 1975; 1hr 10mins, I think). James Maxwell moves in with Julian Glover and runs an overcomplicated murdery spy ring where they bicker a lot in between killing girls by advertisement and burying them in the back garden. What could possibly go wrong?? Anyway, it’s solid gold cheese, has bonus Julian Glover and a lot of natty knitwear. What more does an old telly fan want? (tw: Keith Barron being inexplicably the very meanest Thriller boyfriend.) On YT but tends to get taken down fast.

***

Films

Design for Loving (1962; comedy). Can be rented from the BFI online for £3.50. Isn’t that great or that bad (or that funny either), but does have JM as a dim layabout beatnik, which is atypical.

***The Traitors (1962). This is a low-key little 1hr long spy B-movie, but it’s also thoughtful and ambiguous with a nice 60s soundtrack and location work (it’s a bit New Wave-ish) and the central duo of JM and Patrick Allen are sweet and it all winds up with James Maxwell going in the swimming pool. One of the things where JM is actually American. (Talking Pictures show this occasionally & it is out on DVD as an extra on The Wind of Change.) The quality of the surviving film is not great, though.

***Girl on Approval (1962). A Rachel Roberts kitchen sink drama about a couple fostering a difficult teenager. It’s dated, but it’s also really interesting for a 1950s/60s slice of life (and very female-centric) & probably the only time on this list JM played an ordinary person.

***Otley (1969). Comedy that’s generally dated surprisingly well & is good fun, starring Tom Courtenay +cameos from what seems like the whole of British TV. JM is an incompetent red herring & there are more cardies and glasses as well as a random barometer.

Old Vic/Royal Exchange group productions

(Surviving works made by the group that JM was involved in from drama school to his death, made by Michael Elliott or Casper Wrede. I like them a lot mostly, but they are all slow and weird and earnest & not everybody’s cup of tea.)

Brand (BBC 1959). The BBC recording of the 59 Company’s (the name they were then using) landmark production, starring Patrick MacGoohan. This was a big deal in British theatre & launched the careers of everybody involved. It’s very relentless and weird but interesting & I’m glad they decided it was important enough to save. First fake beard alert of this post. It won’t be the last. On YT & there is a DVD, which is sometimes affordable and sometimes £500, depending on the time of day.

***Private Potter (1962). The original TV play is lost and this film has an extraneous storyline, but otherwise has most of the TV cast & gives a pretty good idea of why as a claustrophobic talky TV piece it made such an impact. Tom Courtenay is Private Potter, a soldier who claims to have had a vision of God during a mission & James Maxwell his CO who needs to decide what to do about this strange excuse for disobeying orders. Tw: fake eyebrows (!) and moustaches. Only available on YT.

[???]One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovitch (1970). Again, no DVD release (no idea why), but it is on YT. I haven’t seen this yet, but it’s another Casper Wrede effort starring Tom Courtenay and apparently JM is especially good in it. (I’m just not good at watching long things on YT and keep hoping for a DVD or TV showing.)

Ransom (1974). A more commercial effort starring Sean Connery & Ian McShane; it gets slated as not being a good action movie, but is clearly meant to be more thinky and political with the edge of a thriller. JM’s part isn’t large but Casper Wrede shoots his friend beautifully, & it’s a pretty decent film with nice cinematography, shot in Norway, as was One Day. I liked it.

[I think this post might be the longest in the world, whoops. Sorry!]

Cardboard TV (the best bit, obv)

One-off plays etc./mini-series

Out of the Unknown “The Dead Planet” Adaptation of an Asimov short story; this is very good for JM, but hard to get hold of unless you want the boxset. I think someone has some of the eps on Daily Motion. (His other OotU ep is sadly burninated.)

The Portrait of a Lady (BBC 1968). Adaptation of the novel; JM is Gilbert Osmond, so it is great for JM in quantity and his performance, but depends how you feel about him being skeevy in truly appalling facial hair. Do the bow ties and hand-holding make up for it? but he’s in 5 whole episodes, and Suzanne Neve, faced with Richard Chamberlain, Edward Fox, and Ed Bishop as suitors, chooses instead to marry the worst possible James Maxwell. Relatable. XD

***Dracula (ITV 1968, part of Mystery & Imagination). JM is Dr Seward, fainty snowflake of vampire hunters, who falls over, sobs and can’t cope for most of the 1 hr 20 mins. More facial hair, but not as offensive as last time. Suzanne Neve is back again, although now JM is nice, she’s married Corin Redgrave, who’s more into Denholm Elliott. Anyway, I love this so much because it turned out that I love Dracula as well as shaky old TV with people I like in getting to fight vampires and all be shippy. Good news - TP keep showing M&I, the DVD is out, and there are two versions of it up on YT.

The Prison (Armchair Cinema 1974). This is the one with Lincoln in it, but it’s not that great & JM isn’t in it that much, so depends how curious you are for the modern AU! (But my Euston films allergy is worse than my ITC allergy, and I watched this when very unwell, so I may have been unfair.)

Crown Court “Fitton vs. Pusey” (1973) - part of the Crown Court series, set in a town full of clones who all keep returning to court. JM is on trial for his behaviour in (the Korean war? I forget?) although he ought to be on trial for his terrible moustache. It’s not that great, but it is nice JM content. He probably did it, but for reasons, and he wibbles & panics whenever his wife leaves the courtroom. Also on YT.

*** Raffles “The Amateur Cracksman” (ITV 1975) - He is Inspector Mckenzie in the Raffles pilot & is a lot of fun. At one point when there was a Raffles fandom someone in it claimed he was too gay for Raffles, which I’m still laughing about, because Raffles. Anyway, watch out if you try to get the DVD because it is NOT included in S1, whatever lies Amazon tells. It is up somewhere online, though, I think.

Bognor “Unbecoming Habits” (1981). Some down marks for possibly the worst 80s theme & incidiental music ever, but fun & has been shown on Talking Pictures lately. JM is an Abbot running a honey-making friary that is actually a hotbed of spies, murder, gay sex and squash playing. This is the point at which he chooses to strip off on screen for the first time, because strong squash-playing abbots do that kind of thing apparently.

Guest of the week in ongoing series/serials

Since even series with a lot of continuity tended to write episodes as self-contained plays (like SotT), these are usually accessible on their own.

Manhunt “Death Wish” (1970). This is one of the most serialised shows here, but this episode is still fairly contained. WWII drama about three Resistance agents on the run across France. JM is... a Nazi agent & former academic trying to break an old friend (one of the series’ three leads, Peter Barkworth) with kindness, possibly?? (Manhunt is very angry and psychological & dark and obv. comes with major WWII warnings (& more if you want to try the whole thing), but it’s also v good.) Up on YT, I think.

Doomwatch “The Iron Doctor” (BBC S2 1971). “Doomwatch” is the nickname of a gov’t dept led by Dr Spencer Quist that investigates new scientific projects for abuse/corruption/things that might cause fish to make men infertile etc. etc. JM is a surgeon who comes to their attention because he’s a bit too in love with his computer for the comfort of one of his more junior colleagues. (I think it’s perfectly comprehensible & a nice guest turn, but it is hard to get hold of outside of the series DVD. Which, being a cult TV person, I loved a lot anyway, but YMMV!)

***Hadleigh “The Caper” (S3 1973). Hadleigh is a very middle of the road show, but watchable enough (lead is Gerald Harper, who’s always entertaining) and this is pretty self-contained as it centres around an old con-man friend (JM) of Hadleigh’s manservant causing trouble by pretending to be Gerald Harper, for reasons. JM seems to be having a ball.

Justice 2 episodes, S3 1974. He guests twice as an opposing barrister & gets to be part of some nice showdown court scenes. Again, a middle of the road drama, but stars Margaret Lockwood, who was still just as awesome in the 1970s as she was in the 1930s & 40s. On YT.

Father Brown “The Curse of the Golden Cross” (1974). JM is an American archaeologist getting death threats; stars Kenneth More as Father Brown. Just a note, though, that 1970s TV adaptations tended to be really really faithful and this is one of the stories where Chesterton comes out with an anti-semitic moment... (JM was unconscious for that bit and, frankly, I envied him.) But otherwise lots of angsting in yet another fake moustache about someone trying to kill him.

The Hanged Man “The Bridge Maker” (1975). Confession time, I have v little idea what this one was about apart from Ray Smith being an unlikely Eastern European dictator, as this whole series went over my head and was not really my thing. (Ask @mariocki they’re cleverer than me and liked it & can probably explain the plot!) I don’t know if it’s available anywhere off the DVD but on a JM scale it was v good/different as he was a coldly villainous head of security & it wouldn’t be too bad to watch alone, but there was an overarching plot going on somewhere.

Doctor Who “Underworld” (1978). This is famously one of the worst serials in the whole of classic Who, but largely because of behind-the-scenes circumstances, not the guest cast. There is some nice stuff, though, esp in Ep1 (JM is a near-immortal alien who’d like to lay down and die but still the Quest is the Quest as they say... a lot) & it’s bound to pop up on YT or Daily Motion. The DVD has extras that include v v brief bits of JM speaking in his actual real accent (which he otherwise does in NONE of these) & making jokes in character. Honestly, though, this is the only DW where the behind-the-scenes doc is genuinely the most exciting bit as they desperately invented whole new technologies & methods of working to bring us this serial, and then everybody wished they hadn’t.

*** Enemy at the Door “Treason” (LWT 1978). This is a weird episode but I love it lots - from a (v v good) series about the occupation of the Channel Islands. (So obv warnings for WWII & Nazis.) JM is a visiting German Generalmajor, but he’s come for a very unusual reason - to ask for help from his brother-in-law, a blackballed British army officer (Joss Ackland). It’s all weird and low key and JM is doomed and nevertheless probably my favourite thing of his that isn’t SotT.

* The Racing Game 2 eps (1979). Adaptation of Dick Francis’s first Sid Halley novel Odds Against (ep1) + 5 original stories for the series. This is an interesting one - JM plays Sid’s father-in-law & they have a lovely relationship that’s central to the book BUT Dick Francis loved this adaptation and Mike Gwilym who played Sid and was inspired to write a sequel Whip Hand, which he tied in with TV canon - and adopted at least three of the cast, including JM. Which means that all the Sid & Charles fanfic is also JM fic by default and it’s quite impressive. (There’s not much but it’s GOOD.) On YT.

Bergerac “Treasure Hunt” (1981). Not a major role, but pretty nice & it’s one a Christmas ep of the detective show (also set on the Channel Islands) that involved Liza Goddard’s cat burglar, which was always the best bit of Bergerac.

His guest spots in Rumpole of the Bailey (1991) “Rumpole a la Carte” and Dr Finlay (1994) are both really just cameos, but both series come round on Freeview; the Rumpole one is funny and the Dr Finlay one his last screen appearance before his death the following year.

Not worth getting just for JM: Subway in the Sky; Bill Brand and Oppenheimer.

These films only have cameos but some quite fun ones and they come around on terrestrial TV: The Damned (1962), The Evil of Frankenstein (1964) & (more briefly) Far From the Madding Crowd (1967). (I think his cameo in Connecting Doors must be at least recognisable as someone spotted him in it just based off my gifs, but it’s not come my way yet.) I’ve never been able to get hold of any of his radio performances, not even the 1990s one.

ETA: I forgot The Power Game! This is the one surviving series where he occurs as a semi-regular (at least until halfway through S1 when he went off to the BBC to be in the now-burninated Hunchback of Notre Dame). This isn’t standalone, but it’s a good series and it is on YT. See how you go with crackly old TV before you brave it but it’s the snarkiest thing ever made about people making concrete and stabbing each other in the back. JM is a civil servant who tries to run the National Export Board and is plagued by Patrick Wymark and Clifford Evans as warring businessmen.

***

[... Well, now I just feel scary. 0_o In my defence, I have been stuck home bored & ill for years, and often unable to watch modern TV while trying to cheer myself up with James Maxwell, so I didn’t watch all of this at once. It just... happened eventually after SotT. /waves hand

But if anyone feels the need to unfriend my quietly at this point, I understand. /o\]

#james maxwell#masterlist#rec list#well sort of#1950s#1960s#1970s#1980s#there are some things i haven't seen#and some things i know to be extant but unreleased#everything else is burninated or status unknown

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Welsh, Scottish, and Irish Writers

This isn’t a definitive list by the way, so please add names if you think I missed someone important (which I probably have).

WELSH WRITERS

Dannie Abse: poet, playwright and physician. A Doctor’s Register; Ghosts; Funland; Song For Pythagoras.

Gillian Clarke: poet, playwright and lecturer. A Difficult Birth; The Sundial; Catrin.

Roald Dahl: author. Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, 1964; The Twits, 1980; Fantastic Mr Fox, 1970; Danny, Champion of the World, 1975; The Witches, 1983. (I’m not going to list every book he’s ever written so these are just my childhood favourites.)

Ken Follett: author - thriller and historical fiction. The Century Trilogy, 2010-14; Kingsbridge Series, 1989-2020.

George Herbert: poet and priest. The Altar; Easter Wings.

Cynan Jones: author. The Dig, 2014.

Diana Wynne Jones: Welsh-English author. Howl’s Moving Castle, 1986-2008; Dalemark, 1979-93; Chrestomanci novels and short stories, 1977-2006; Derkholm, 1998-2000.

Philip Pullman: Welsh-English author. His Dark Materials, 1995-2000; The Book of Dust, 2017-; Sally Lockhart, 1985-94.

Kate Roberts: author. Traed mewn Cyffion (Feet in Chains/Feet in Stocks), 1936; Te yn y Grug (Tea in the Heather), 1959.

Bernice Rubens: author. The Elected Member, 1969; Madame Sousatzka, 1962; A Solitary Grief, 1991.

Owen Sheers: poet, author, playwright and presenter. Farther; Y Gaer/The Hill Fort; The Dust Diaries, 2004; Resistance, 2007; The Green Hollow (”film-poem”), 2016.

Dylan Thomas: poet, author and scriptwriter. Do not go gentle into that good night; And death shall have no dominion; Portrait of the Artist as a Young Dog, 1940; A Child’s Christmas In Wales, 1955; Under Milk Wood, 1954.

Gwyn Thomas: author, playwright, columnist, and broadcaster. All Things Betray Thee, 1949.

Sarah Waters: Welsh-English author. Tipping the Velvet, 1998. Fingersmith, 2002.

Hedd Wyn: poet. Yr Arwr; Rhyfel; Plant Trawsfynydd.

SCOTTISH WRITERS

Iain Banks (sometimes Iain M. Banks): author - mainstream and sci-fi. The Wasp Factory, 1984; Walking On Glass, 1985; Culture novels, 1985-2012 (can be read as standalones - I recommend Excession).

Robert Burns: poet. Auld Land Syne; To a Mouse; Scots Wha Hae; Tom o’ Shanter; O, Wert Thou in the Cauld Blast.

Arthur Conan Doyle: author, poet, playwright and physician. Sherlock Holmes stories.

Jenni Fagan: author and poet. The Panopticon, 2012; The Sunlight Pilgrims, 2016.

Janice Galloway: author and poet. The Trick is to Keep Breathing, 1989.

Alasdair Gray: author, artist, poet and playwright. Lanark, 1981; Poor Things, 1992.

James Kelman: author and playwright. How Late It Was, How Late, 1994; Greyhound For Breakfast, 1987.

Val McDermid: author - crime and thriller. Tony Hill and Carol Jordan, 1995-2019; A Place of Execution, 1999.

Denise Mina: crime and comic author and playwright. Conviction, 2019; Garnethill, 1998-2001; Paddy Meehan, 2005-07; John Constantine, Hellblazer, #216-228

Maggie O’Farrell: Irish-Scottish author. The Vanishing Act of Esme Lennox, 2007; After You’d Gone, 2000; I Am, I Am, I Am: Seventeen Brushes With Death, 2017.

James Robertson: author and poet. The Testament of Gideon Mack, 2006; And the Land Lay Still, 2010.

Walter Scott: author, poet and playwright. The Lady of the Lake, 1810; Ivanhoe, 1820; The Bride of Lammermoor, 1819.

Ali Smith: author. How to Be Both, 2014; Seasonal 2017-20; There but for the, 2011.

Muriel Spark: author, poet and essayist. The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie, 1961; The Ballad of Peckham Rye, 1960; A Far Cry from Kensington, 1988.

Robert Louis Stevenson: author. Treasure Island, 1883; Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde, 1886; Kidnapped, 1886.

Alan Warner: author. Morvern Callar, 1995.

Irvine Welsh: author and screenwriter. Trainspotting, 1993; Skagboys, 2012.

Louise Welsh: author - psychological thriller. The Cutting Room, 2002.

IRISH WRITERS

John Banville: author, critic and scriptwriter. The Sea, 2005; The Frames Trilogy, 1989-95.

Samuel Beckett: author, director, playwright, poet and translator. Waiting For Godot, 1954; Molloy, 1951; Malone Meurt, 1951; L’innommable, 1953.

Maeve Binchy: author, playwright and columnist. Tara Road, 1998; Circle of Friends, 1990; A Week in Winter, 2012.

Elizabeth Bowen: author. The Last September, 1929; Eva Trout, 1968; The Death of the Heart, 1938.

John Boyne: author. The Boy in the Striped Pyjamas, 2006; The Heart’s Invisible Furies, 2017.

Emma Donoghue: Irish-Canadian author, playwright, screenwriter and literary historian. Room, 2010; Slammerkin, 2000.

Anne Enright: author. The Gathering, 2007; The Green Road, 2015.

Josephine Hart: author, producer and presenter. Damage, 1991.

Seamus Heaney: poet, playwright and translator. Digging; Strange Fruit; In Memoriam Francis Ledwidge; Beowulf: A New Verse Translation, 1999.

James Joyce: author, critic, poet and teacher. Ulysses, 1922; A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, 1916.

Molly Keane: author and playwright. Good Behaviour, 1981; Devoted Ladies, 1934; Time After Time, 1983.

C. S. Lewis: author. The Chronicles of Narnia, 1950-56.

Iris Murdoch: author and philosopher. Under the Net, 1954; The Sea, the Sea, 1978.

Edna O’Brien: author, poet and playwright. The Country Girls Trilogy, 1960-64; August is a Wicked Month, 1965; A Pagan Place, 1970.

Frank O’Connor: author. Guests of the Nation, 1931; My Oedipus Complex, 1952; The Majesty of Law, 1936.

Nuala O’Faolain: author, journalist, producer, critic and teacher. Almost There: The Onward Journey of a Dublin Woman, 2003; Are You Somebody? The Accidental Memoir of a Dublin Woman, 1996.

Bram Stoker: author. Dracula, 1897.

Jonathan Swift: author, satirist, essayist, poet and cleric. Gulliver’s Travels, 1726; A Modest Proposal, 1729.

Oscar Wilde: author, poet and playwright. The Picture of Dorian Gray, 1890; The Importance of Being Earnest, 1895.

W. B. Yeats: poet and playwright. The Lake Isle of Innisfree, 1890; Adam’s Curse, 1903; Easter 1916, 1916; The Second Coming, 1920; Cathleen Ní Houlihan, 1902.

#irish literature#scottish literature#welsh literature#ireland#scotland#wales#i have now written the word author so many times#it doesn't look like a word anymore

55 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Milwaukee Cannibal

Timeline of events

1960′s

May 21, 1960: Jeffery Lionel Dahmer was born in Milwaukee’s Evangelical Deaconess Hospital to his parents Lionel and Joyce after a very difficult pregnancy. According to Lionel, Joyce experienced random bouts of paralysis during the pregnancy, and doctors were unable to find any reason for this. To try and treat this and mostly to calm her during, she was given “injections of barbiturates and morphine, which would finally relax her.” She would apparently also be given phenobarbital.

We know now that the “Use of barbiturates during pregnancy has been associated with a higher incidence of fetal abnormalities. Neonatal barbiturate withdrawal symptoms have been reported in infants whose mothers took barbiturates during pregnancy,” but we don't know for sure if this applied to Jeffrey.

1962: The family made the decision to move to Ames, Iowa in 1962 so that Lionel could work on his Chemistry Ph.D.

1964: After their young son complained of extreme pain, Lionel and Joyce took Jeffrey to the hospital, were he was diagnosed with a brutal double hernia in his scrotum. Even after the surgery corrected the issue, Lionel would claim that this experience was what initially triggered the change in Jeffrey’s personality, apparently making him become much more shy and withdrawn. Psychologists believe that there is a possibility that this could actually have influenced his feelings of sexual inadequacy and insecurity in later life.

November 1966: When Joyce fell pregnant with her second child David, the family decided to move home in an attempt to find the perfect spot to raise their two children. This led to several moved throughout Ohio during the following year. This was not an easy time for the family, Joyce was struggling with another very difficult pregnancy, and young Jeffrey, who was now in the 1st grade, was starting to feel neglected, especially after David was born on December 18th.

Of course feeling neglected when a new baby comes along is a fairly common thing, but unlike most children, Jeffrey would not get over this feeling, instead it would get worse. Lionel describes his son at this time as extremely shy and withdrawn, even going as far as t say that he was terrified of new people and situations.

1968: After the family moved to Bath Ohio, Jeffrey experienced a new and particularly heinous kind of trauma. According to Lionel, Jeffrey was molested by a boy in the neighbourhood, however Jeffrey never once admitted to even remembering this.

It seems likely that Jeffrey repressed this memory, especially since his personality ticks pretty much every box when it comes to the traits that come with childhood memory repression:

Strong reactions to certain places people and situations.

Difficulty controlling emotions.

Difficulty keeping a job.

Struggling with a sense of abandonment.

Immaturity.

Tendency to self sabotage.

Impulsive.

Emotionally exhausted.

Anxiety.

Trouble with anger management.

1970′s

Late 1970: Over the last few years, Joyce had, according to Lionel, been taking drugs in order to try and deal with the extreme anxiety that she was facing on a near daily basis, but they didn't really work, and in the late 1970′s she was actually institutionalised twice for ‘psychiatric problems’. Since the family were so busy trying to take care of Joyce and raise their very young son, Jeffrey reportedly did not have a stabilising influence, or much emotional support.

This combined with the fact that he had grown tired of not fitting in led Jeffrey to build himself a reputation as somewhat of a clown, and a misfit. His behaviour at that time is very similar to that of fellow serial killer and cannibal Arthur Shawcross, he would drink heavily at just 10 years old and was always pulling ‘pranks’. Jeffreys pranks including randomly shouting, bleating like a sheep, and most memorably, faking epileptic fits.

June 4, 1978: By the time that Jeffrey had graduated from high school, his parents were going through a very difficult divorce and due to the fact that he was now legally an adult, he was actually living by himself in the home while his parents and brother lived elsewhere. Jeffrey had less emotional support than ever before and all the freedom in the world.

June 18, 1978: 19 year old Steven Mark Hicks was hitchhiking when Jeffrey drove by him and stopped, suggesting that he come back to his home for a few beers. Hicks agreed and the two went back to the house and began to drink, everything was going fine, until Hicks tried to leave. It is believed that Jeffreys crippling fears of abandonment kicked in and he flipped. He grabbed a barbell and began to club and then strangle Hicks with the weapon. According to Dahmer, over the next few weeks (!) Jeffrey stripped the flesh from the bones using acid (like he apparently had to a whole host of animals previously) smashed the bones and disposed of the remains in his back yard.

Dahmer would later claim that he had killed Hicks because he didn't wat him to leave. This reasoning would later be corroborated by at least one survivor of Jeffreys attack, claiming that Jeffreys entire personality changed when he mentioned wanting to leave. This reasoning isn't difficult to believe when you consider the lack of parental support, tendency to move, and I believe most noticeably his memory repression

After his high school graduation Dahmer enrolled in Ohio State University but he stayed only one term before dropping out.

December 24, 1978: Lionel remarried.

December 29, 1978: Jeffrey was trained as an army medic and shipped of to Baumholder Germany. This happened not long after the Vietnam war, and morale and discipline was at an all time low within the armed forces at the time, and drug and alcohol abuse amongst the soldiers was rife.

Dahmer’s reputation changed once he joined the army, he was no longer known as a clown an a prankster, but as an aggressive drunk.

(Interesting side note, after his arrest police actually looked into murders in the area were he was stationed to see if he was active while he was there, and there did appear to be a serial killer in Baumholder at the time, but it is not believed to be Jeffrey since it was young women being killed, and as far as is known, Jeffrey only killed men.)

1980′s

March 26, 1981: When Jeffreys drinking reached the level were he was no longer able to do his job, he was discharged from the army and sent back to the US. When he got back, he slept on the beach in Florida for a few months before returning to Ohio.

October 7, 1981: Dahmer was arrested for a drunk and disorderly and resisting arrest and paid a small fine.

August 7, 1982: Dahmer was arrested again for another drunk and disorderly. He dropped his pants in public. By this point in his life Jeffrey had moved in with his grandma, who was apparently the only person in his family who actually showed Jeffrey any affection.

September 8, 1986: By this time, Jeffrey had gone off the rails, and was getting himself into trouble pretty often. He was arrested once again for exposing himself to a group of children in Milwaukee. There are two different accounts of what happened at that time, (he was either urinating or masturbating).

Dahmer was also now frequenting gay bars and bath houses often, and actually got himself banned from one bath house, for drugging at least 4 men. No official charges were filed against him, but one of his victims was hospitalised for about a week.

September 15, 1987: According to Jeffrey, he woke up in a hotel room to find the dead body of 24 year old Steven W. Tuomi. He transported the corpse to his grandmothers home in a large suitcase, disposing of the body pretty much as he had Steven Hicks.

Nine years passed between the murders of Hicks and Tuomi, which is pretty unusual for a serial killer to do. He spent years before this second murder working his way up to it, learning how to pick up men, how to drug them, and how much. We still don't know for sure whether or not Jeffrey actually remembers the murder or not. It is possible that he was just too drunk to remember, or that, like he had for earlier trauma, he repressed the memory. I personally find it like likely that the latter is true to be honest, as it seems strange to me that he would admit to all his other crimes and not this one. Also, Jeffrey would later say that he didn't actually enjoy the killings, and that there were a necessary evil in order for him to get the bodies.

January 1988: Jeffrey offered 14 year old James Doxtator some money if he agreed to pose nude for some photos. After James agreed Jeffrey took the teenager back to his grandmothers house. After raping James (Dahmer described it as sex but James was still a child so it was actually rape) Dahmer drugged and then strangled the boy. By now his method of disposal, acid and crushing bones was well practiced.

March 24, 1988: 25 year old Richard Guerrero also came back to Jeffreys grandmothers house, once again for nude photos, and once again after sex, he drugged and strangled the young man.

September 25, 1988: Jeffrey finally moved into his own place, which is where the pace of his crimes really picked up, since he no longer felt he needed to be careful, he once again had all the freedom that he wanted.

Once he moved in, he met a 13 year old boy, who was once again offered money to pose nude for him. Jeffrey drugged the boy sing coffee and fondled him, but luckily the young boy escaped.

January 1989: Jeffrey was arrested and this time charged with 2nd degree sexual assault and enticing a child for immoral purposes.

March 25: Dahmer met Anthony Sears, 24, at a club, and like he had previously he drugged and murdered him after sex. After Dahmers arrest, Sear’s skull was recovered from Dahmer’s apartment. He had painted the skull.

May 23rd: Jeffrey was sentenced to 5 years and three years, for his attack on that 13 year old boy, but he only served 10 months before he was out on a probationary period of 5 years.

1990

May 29: Dahmer met 33 year old Ricky Beeks at a club, and used his usual MO of bribing, drugging and strangling. However this time Jeffrey had sex after he was dead, instead of before. Once again, Jeffrey had painted the mans skull, which was recovered after his arrest.

June 1990: 28 year old Edward W Smith was killed in the same way as Dahmer's previous victims, but this time Dahmer did one thing different. Jeffrey took photos of the dismemberment process.

September 2: Something changed before the murder of 24 year old Ernest Miller, causing Jeffrey to be even more gruesome than he had been previously. Instead of drugging and strangling Ernest like he had his previous victims, he drugged him and cut his throat. Once again taking pictures of the body, Jeffrey dismembered the body, putting the biceps in the freezer, and once again painting his skull.

September 24: David C Thomas was the first time that Jeffrey killed somebody without sex being involved. It is believed that David wanted to leave before having sex with Dahmer, since Dahmer was known to kill his victims in order to make sure that they couldn't leave.

1991

March 7: Curtis Straughter was 18 years old when he was murdered, with Jeffrey this time using a different sequence of events. Previously he had had sex with his victims then drugged and killed them, and at least once he had drugged and killed them and then had sex, but this time he drugged Curtis before raping and murdering him. It is likely that this change was due to the fact that Jeffreys last victim had wanted to leave prior to sex.

April 7: Errol Lindsey, 19, last seen alive. Dahmer met him on the street and offered him money to come home with him. He drugged Lindsey, strangled him and had sex with the body. The unpainted skull was recovered from Dahmer's apartment.

May 17: 14 year old Konerak Sinthasomphone was pickes up by Dahmer outside of the mall, he went with Jeffrey under the promise of money for nude pictures. After drugging the boy Jeffrey apparently felt pretty comfortable, ince he left the home to go out for a beer. The boy managed to escape, naked, and the neighbours called the police. Somehow however Jeffrey managed to convince the police that responded that he and the teenager were simply lovers who had had a fight (I don't know how they could be so stupid, this is a drugged child and a 30 year old with a pretty lengthy criminal record, including the sexual assault of a minor?! Like how do you just let that be?!) and the police actually RETURNED the poor boy to the sick serial killer. Dahmer strangled the 14 year old as soon as the police were gone, had sex with the body and then took pictures like he had previously. Konerak’s skull was also recovered from the apartment.

Once people actually discovered what had happened the officers involved received mild disciplinary action (which is nowhere near enough) and the department was sued.

May 24: Deaf and mute 31 year old Tony Hughes had reportedly known Dahmer for about 2 years when Dahmer, by writing on paper, offered the man $50 to come and pose nude for him. Hughes was drugged and murdered without sex. Once again Hughes skull was found in Jeffreys apartment.

June 30: Matt turner was killed by Jeffrey after a gay pride parade. After cutting the body up the head was put in the freezer and the rest was put into a barrel of acid.

July 6: 23 year old Jeremiah Weinberger travelled with Dahmer from Chicago to Milwaukee where he then stayed overnight. Like the previous cases, everything was fine until Jeremiah decided that he wanted to leave, at which point Dahmer drugged, killed and disposed of the young mans body.

July 15: Jeffrey was fired from the Ambrosia Chocolate Co. for bad attendance.

On this same day Oliver Lacy, 23, was killed by Dahmer. Jeffrey had sex with the body before dismembering it, at which point he put his head In the fridge and heart in the freezer “to eat later”.

July 16: Joseph Bradehoft, 25, met Jeffrey at a bus stop, where Dahmer offered him money to pose for nude pictures. After sex, Dahmer drugged him and strangled him with a strap. He dismembered the body and, as before, put the head in the freezer and the body in the acid barrel.

July 22, 1991: Shortly after midnight, Tracy Edwards, 32, escaped from Dahmer with one hand in a handcuff and flagged down a police car. He lead the cops back to Dahmer's apartment. They found photos of dismembered victims and body parts in the refrigerator and freezer. Shortly, the sight of crews in biohazard protection suits taking evidence out of Dahmer's apartment was televised all over the world. The suits were necessary because of the smell of decay in the apartment and because of the acid in the barrel.

Caught red-handed, with overwhelming physical evidence against him, it's not surprising that Jeffrey confessed. His dry, unemotional descriptions of murdering a dozen and a half young men belied the reality of brutality and sadism that was revealed in Tracy Edwards' testimony.

It's possible that the sameness of the descriptions (Offers of money to pose, drugs to knock them out) was not entirely accurate. Tracy Edwards claimed he was not offered money, that he only went to Dahmer's apartment for some beers before going out again. He may have been covering up his own indiscretion, or Dahmer may have lied about the ways he lured people back to his apartment in order to make them seem less like innocent victims.

Edwards was drugged, but did not lose consciousness. This raises the possibility that the sedatives Dahmer gave victims were intended only to weaken them, while leaving them aware of what was being done to them. Dahmer had certainly had enough practice by then to have a good idea what dose was needed to knock a man out. Dahmer may have enjoyed taunting the victims about their fate and killing them, slowly, much more than he let on later.

Dahmer also claimed that he needed to drink heavily in order to be able to face killing people, but we know that he was a hard-core alcoholic for much of his life. For him, making excuses for drinking was normal and can not be regarded as likely to be honest.

1992

January 14: Dahmer entered a plea of guilty but insane in 15 of the 17 murders he claimed to have committed.

February 15: By 10-2 majority vote, a jury found Dahmer to be sane in each murder. Testimony from defense and prosecution experts took weeks and was extremely gruesome. One expert testified that Dahmer periodically removed body parts of his victims from the freezer and ate them. Another testified that this was a lie Dahmer told to make himself seem insane. The jury deliberated slightly more than ten hours.

February 17: Dahmer was sentenced to 15 consecutive life terms. At the sentencing, Dahmer read a prepared statement in which he expressed sorrow for the pain he had caused.

"I knew I was sick or evil or both. Now I believe I was sick. The doctors have told me about my sickness and now I have some peace. I know now how much harm I have caused. I tried to do the best I could after the arrest to make amends."

"I now know I will be in prison the rest of my life. I know that I will have to turn to God to help me get through each day. I should have stayed with God. I tried and failed and created a holocaust. Thank God there will be no more harm that I can do. I believe that only the Lord Jesus Christ can save me from my sins."

He later pled guilty to aggravated murder in Ohio, in the death of his first victim, Steven Hicks. He was sentenced to life in prison without parole.

November 28, 1994: Dahmer murdered in prison. Dahmer and two other inmates were assigned to clean the staff bathroom of the Columbia Correctional Institute gymnasium in Portage, Wisconsin. Guards left them alone to do their work for about twenty minutes, starting at around 7:50 a.m. When Dahmer was discovered, he was unconscious and his head and face were bloody. He died on the way to the hospital from multiple skull fractures and brain trauma.

A bloody broom handle was found near Dahmer, but a broom is probably not sturdy enough to inflict the damage that killed him. Reports in December indicated that he was struck with a steel bar stolen from the prison weight room.

One of the other two inmates in the area with Dahmer was also attacked. Jesse Anderson, 37, was pronounced dead in the hospital at 10:04 a.m. on November 30. Anderson was convicted of stabbing and beating his wife to death in 1992. He was serving a life term.

The third inmate in the work party is twenty-five-year-old Christopher Scarver, a convicted murderer reportedly taking anti-psychotic medication. Scarver murdered a coworker when he was angry at his boss. The boss got away. Scarver claimed his boss was a racist and there has been speculation that Scarver, who is black, wanted revenge for the wrongs Dahmer and Anderson (both white) had done to black people. The majority of Dahmer's victims were black. Anderson tried to blame two fictitious black men for murdering his wife during a mugging. It's been pointed out that a desire for publicity or status may have also been a motive.

Dahmer was attacked the previous July, also. A convicted drug dealer tried to cut his throat with a razor blade attached to a toothbrush handle, making a crude straight razor, but the weapon fell apart. Dahmer, received minimal injuries.

Scarver is said to have delusions that he is Christ. He has been in psychiatrict observation and treatment several times, with diagnoses of bi-polar disorder and schizophrenia. He was found guilty of the murder, though, and sent to prison. A jury apparently did not believe he was insane.

#true facts#true crime#true#crime / law / justice#major crimes#murder#murderer#Murderpedia#serial killer#killer#the milwaukee cannibal#milwaukee#cannibalism#jeffrey dahmer#dahmer#timeline#criminal justice

35 notes

·

View notes

Text

World Building: Body Swap Universe

This is another universe which is largely like ours. The point-of-divergence is late 1981 - in which the birth and survival of Zachary Baker (Zacky Vengeance from Avenged Sevenfold) splits this universe off from James Baker Dead Universe, James Baker Alive Universe, and Avenging Gaia Universe (the three universes to form the three key sliders groups).

This is the one universe in which The Rev from Avenged Sevenfold does pass away in late 2009, Brooks Wackerman joins the band in 2016, and Donald Trump is elected POTUS later that year.

A major event occurs on January 20th of 2017. About an hour before Donald Trump is to be sworn in as POTUS, he switches bodies with Jimmy Reed! This means Jimmy Reed now has to fumble his way through a major federal office that he never considered running for.

Shortly before the inauguration, Jimmy-as-Donald tries to call Rose Reed (who is both his mother and his daughter) to explain what happened.

Jimmy-as-Donald: Listen, honey, this may seem strange - but...

Rose Reed: *demands* Who is this?

Jimmy-as-Donald: I’m Jimmy Reed. I...

Rose Reed: *checking caller ID* I dunno what kind of sick joke you think you're playing, Donald Trump! I don't vote Republican, and I sure the hell didn't vote for *you*! Good bye! *hangs up*

While Jimmy-as-Donald is understanding of Rose’s reaction, he can’t help but feel lost and lonely. He decides to check his Twitter account, and sees that he has a lot of messages from fans hoping that he gets better soon. This prompts Jimmy to Google his own name, which alerts him to a news article detailing how Jimmy Reed is in a coma after being severely injured in a car crash. While this initially horrifies Jimmy, he comes to realize that... if he himself is in Donald Trump’s body... than Donald Trump must be in *his* body! Jimmy then sees the silver lining, as he realizes that Donald Trump can’t make trouble for him while he’s in a coma.

Barron, Tiffany, and even Melania come to like the new “Donald Trump” - while Donald Jr, Eric, and Ivanka not so much. Just a few days after his inauguration, “Donald Trump” gives a huge apology on national TV for “his” prior behaviour (from before the body swap). This is a turn-off to Trump’s main base (who liked Trump for his ruthlessness) - while those to his left, understandably, regard his apology with skepticism. Rose Rose is *especially* skeptical, considering that strange phone call that she got from “Donald Trump”.

Barron Trump definitely comes to appreciate this new affectionate and attentive version of his father:

Barron Trump: You used to spank me a lot, when I was younger.

"Donald Trump": *hugging Barron* Well, pumpkin, Daddy is very sorry about that. I dunno what I was thinking. I promise to be more loving to you, from now on.

In the months to come, “Donald Trump” manages to successfully get several decidedly progressive bills passed.

“Oh, great! We ended up as a RINO as POTUS!” is the common reaction from Trump’s former base.

~~~~~

Meanwhile, the body that Jimmy Reed has left behind is comatose for several weeks. Even Marlene and Malinda (Jimmy Reed’s aunts/daughters) come to visit him in the hospital. They get this nagging intuition that something is off, yet they can’t quite pinpoint it. Both have psionic abilities, although neither of them have psychokinesis (which doesn’t even exist in this universe).

After coming to, “Jimmy Reed” is amnesiac for the next few weeks. Much to the chagrin of his family and friends, “Jimmy Reed” has started acting outrageously rude and demanding - complete with using of foul language, which Jimmy Reed has never been too keen on.

“I understand that he has amnesia - but amnesia doesn’t usually result in a complete change of personality, does it?”

At one point, as “Jimmy Reed” and Rose are eating out, they catch “Donald Trump” on TV. When “Jimmy Reed” refers to “Donald Trump” as a “pansy” and a “wuss”, Rose is quite taken aback. While Rose is no fan of “Donald Trump”, those aren’t exactly the words she'd use to describe him - nor does she even see them as being major character flaws. And neither did Jimmy Reed himself!

Rose soon calls up Marlene and Malinda, hoping that they could pinpoint the cause of “Jimmy Reed’s” strange new behaviour. Both of them come over, and they can instinctively detect that it is *not* Jimmy Reed in that body! Rose then recalls that strange phone call from “Donald Trump”, followed soon by “Donald Trump’s” apology and sudden change of behaviour. The trio of women come to realize what happened. “Jimmy Reed” is Donald Trump, while “Donald Trump” is Jimmy Reed!

~~~~~

Rose is then quick to send Jimmy Reed an email message explaining that she, with the help of Marlene and Malinda, figured out what happened - hoping that Jimmy still checks for email messages.

Jimmy-as-Donald checks his email inbox, and he finds the message from Rose. He is relieved to find out the he is no longer alone, and that he now has three family members that know what happened.

However, there are a still issues of concern: Donald-as-Jimmy is still amnesiac, they have no idea how the switch occurred... and, even if they could figure out how to switch Jimmy Reed and Donald Trump back, they have the welfare of an entire country... and even the world... to consider!