#sting of a wasp

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Can you defrost an iterator?

scug designed by the_snail!

#rw#rain world#ciorart#iterator#sting of a wasp#sturgeon scug needs a name#need some suggestions :3#slugcat oc#iterator oc#art#hailstorm ocs

258 notes

·

View notes

Text

I caught this rambunctious creature flying around the kitchen. Outside you go.

Life pro tip: a cheap butterfly net with telescoping handle is excellent for relocating small friends, especially if they’re skittish and obsessed with the ceiling.

Yellow-legged mud dauber (Sceliphron caementarium)

Northern California

#mud dauber#wasp#bugs#despite their appearance mud daubers are fairly docile#they don’t sting unless they really have to#ie you grab at them or bother their nest#nature#nature photography#biodiversity#bugblr#animals#arthropods#inaturalist#entomology#insect appreciation#hymenoptera#buzz buzz#butterfly net#insects#catch of the day#creature#macro photography#small friend

283 notes

·

View notes

Text

#transformers animated#tfa jazz#tfa bumblebee#tfa wasp#tfa jetfire#tfa jetstorm#tfa safeguard#tfa bulkhead#tfa prowl#tfa optimus prime#tfa sentinel prime#tfa ratchet#screenshots#where is thy sting?

106 notes

·

View notes

Note

Win for corruption and web avatars everywhere! New deadliest spider has been discovered in Australia and it’s basically just the old deadliest but twice as big!

It also happens to be called the Newcastle Big Boy and it’s one of the few spiders that will actively attack nearby humans. Fangs are sharp and long enough to pierce leather! Have fun with that info!

I support her.

#I think very small animals are allowed to be extremely aggressive. they’re very small. humans are also very deadly and aggresive to spiders.#they just get so mad when those small animals have any capacity to harm them back#‘oh noooo a wasp can sting me’ you can crush it to a paste effortlessly#it’s allowed little a stinger.

60 notes

·

View notes

Text

my lads :)

134 notes

·

View notes

Text

Guess who's about to find out if they are allergic to wasps as well as bees!!

#normal people do NOT get stung this much. am i just like. emitting some kind of 'sting me' pheremone#in the wasp's defense i knelt down on top of it#in my defense why was the wasp just sitting in the grass doing nothing

75 notes

·

View notes

Text

Geniunely I don't get the whole song and dance ppl do abt wasps being sooo mean and aggressive. A paper wasp landed on my book while I was reading outside the other day and we just chilled for a bit until she flew away. Maybe they sting you bc you're ugly or something idk.

#i think the actual reason is that ppl who are afraid of wasps fuck with them more#e.g. tearing down their nests or swatting at them#so ofc they get stung more often#the best way to not get stung by stinging insects is literally by giving them space and being chill when they get in yours#txt

104 notes

·

View notes

Text

"spelunking is so scary" I say as I belly crawl into a mine from the early 1900s that has been nearly forgotten, 8 miles from my car, no cell phone reception

#i didn't do it last time just because I was tired and eepy from the post wasp sting benadryl#(Yes I know of the dangers of mines but I've been obsessed with them since I was little. Oh no it's an autism special (interest))

71 notes

·

View notes

Text

Thinking about my imaginary hobby farm again today. I don't really want livestock on it except for maybe two token pet sheep but I do want bees. Why did my stupid city have to ban beekeeping within city limits I have more than enough room on the patio for some bees come on.

#they're fine they only sting a little#if the patio manages to attract a wasp nest Ill have to adopt that instead

40 notes

·

View notes

Note

man obviously i neeeed to know more about whistle now (no pressure if u want to heheheheeee)

Now some context (I infodump)!

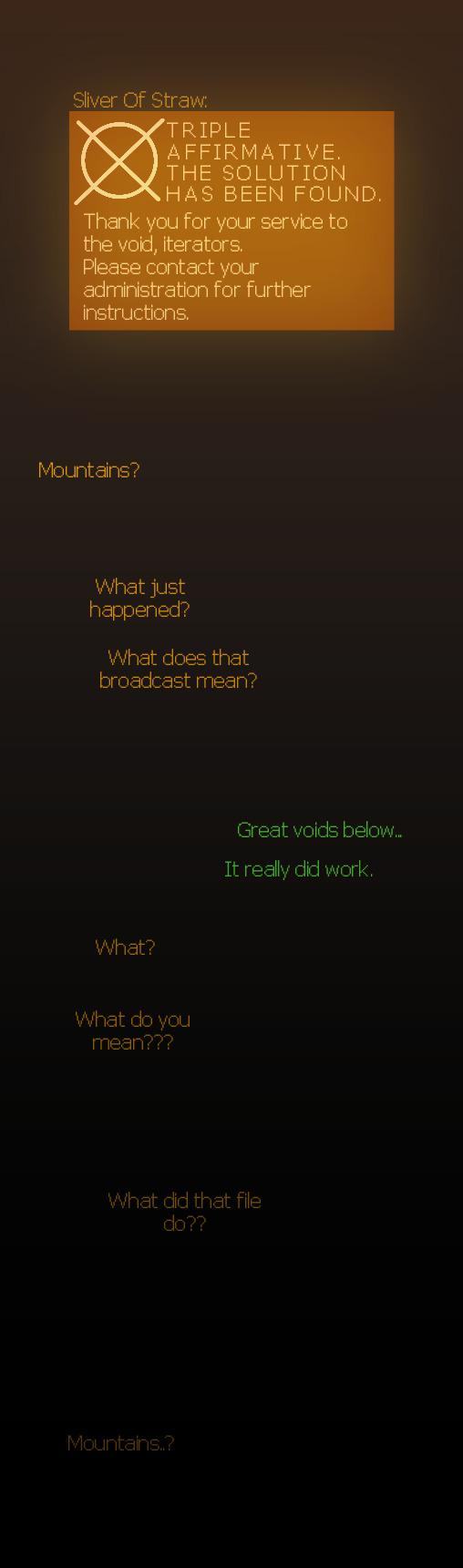

Whistle From The Mountains created Sting of A Wasp. This was partially proof of concept (building a whole nother iterator is sick as hell) and also because he needed something that did not have the self-destruction taboo programmed into it.

He developed code which could shut down an iterator's whole entire superstructure, he just needs someone who can send out the commands... Wasp.

Etc. etc. etc. Wasp isn't a huge fan of murder and WFTM is not too happy about it.

Still fleshing out the story, so all of this is subject to change and doesn't have too much detail lol.

#rw#rain world#ciorart#iterator#whistle from the mountains#sting of a wasp#sliver of straw#rw sos#iterator oc#hailstorm ocs

222 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hey hi the indoor wasps are becoming a problem can you please send me all your home remedies for wasps in your home one just tried to crawl down my shirt (I don't get *that* many wasps in my house but like I would like less wasps inside my house. Preferably no wasps! I stayed calm when it was on my shirt but when it tried to crawl down my shirt I was no longer calm) (the wasp was caught (not in my shirt) and safely brought outside)

#the person behind the yarn#some days you realize a truth about yourself that you never knew#such as: when it comes to potential wasp stings#I would rather the wasp sting me THROUGH my shirt and not from INSIDE my shirt#a thing I did not know I had such a strong preference on!#and like. I don't blame the wasp#a lot of insects see small dark places as safe#and the living room is bright and perhaps scary to a wasp#but that is not safe wasp territory. that is cleavage. I would like it to be waspless. wasp-free

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

Every time someone says something hateful and/or grossly misinformed about wasps I inch closer and closer to becoming a genuine wasp therian

#waspposting#someone will be like ''wasps serve no purpose except to be mean and sting you and we should kill all of them'' and I'M offended

77 notes

·

View notes

Text

#transformers animated#tfa sentinel prime#tfa jazz#tfa optimus prime#tfa bulkhead#tfa wasp#tfa ratchet#tfa bumblebee#tfa jetfire#tfa jetstorm#tfa prowl#video#where is thy sting?

149 notes

·

View notes

Text

i have a lot of respect for wasps. they have firm boundaries and they will protect themselves and their home and their family and theyll risk their lives to do it every single time they think theyre in danger. and i feel like it says something about us as a society that we hate them for that

#ik im anthropomorphizing them#which makes this not really true bc theyre a different kind of being than we are#but i think i got the general idea of them#and sometimes anthropomorphizing is the best tool we have to understand other species#besides its way more accurate than the even more anthropomorphic (and ridiculous)#“wasps are full of hatred and malice and sting us because they enjoy watching us suffer”#especially like... As If humans dont Kill Them With Poison for existing too close to us. yeah theyre the hateful ones for sure

44 notes

·

View notes

Text

Defense mechanisms

Vasya doesn't want to actually hurt the thief, but she doesn't like being stolen from.

Bug facts time!

Velvet ants try very hard to impress upon other animals that they are not something you want to deal with. They have brightly colored markings to warn all those who can see. If it's not enough, they also chirp or squeak their warnings. And they aren't all bark either! Their chitin is tough and their sting is very painful, which is why they are called "cow killers". They can't actually kill a cow, but you know to stay away from them when you hear that name.

Their chirping is cute to me, but that's because I was never bitten by them. I imagine other bugs and animals would find it quite terrifying.

This woman can yell! What else is she capable of?!

#mousedrawings art#bug fables oc#vasya oc#thief bf#id in alt#beware!#it's a wasp!#and it will sting you!#I imagine those are the instincts that should kick in when you hear them squeak

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

alright I’m gonna say it. if u go out of ur way to kill insects I think ur mean. (And no, I’m not talking about bugs that startled you or were in your room, or accidentally stepping on ants) like I don’t care how “useless” or “creepy” that bug is, if u kill shit on purpose when it is of no danger to you, ur an asshole.

#I’m talking abt wasps here#we had recess when I was in high school and people would find wasps and taunt them#bait them with fruit and then kill them#the wasps didn’t even sting anyone if you left them alone#I am an avid bug lover#mooing#bugblr#entomology

41 notes

·

View notes