#steel armature

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Patu Digua by Ann Carrington

#art#sculpture#steel#steel armature#Ann Carrington#halloween#spider#spider web#insects#bugs#fall season#autumn

93 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Cupboard IX” (2019), stoneware, raffia, and steel armature, 78 × 60 × 80 inches. Image courtesy of Institute of Contemporary Art/Boston.

A Groundbreaking Monograph Delves Into Simone Leigh’s Enduring Commitment to Centering Black Women

All images © Simone Leigh

“No Face (House)” (2020), terracotta, porcelain, ink, epoxy, and raffia, 29.5 × 24 × 24 inches. Image courtesy of Matthew Marks Gallery

#simone leigh#artist#art#monograph#stoneware#raffia#steel armature#institute of contemporary art#boston#black women#matthew marks gallery#terracotta#porcelain#ink#epoxy

1 note

·

View note

Video

Katharina Fritsch, Hahn/Cock, 2017, fiberglass, polyester resin, paint, stainless-steel armature 3/22/24 #minneapolissculpturegarden by Sharon Mollerus

#Hahn/Cock#paint#minneapolissculpturegarden#2017#fiberglass#stainless-steel armature#Katharina Fritsch#polyester resin#Minneapolis#MN#flickr

0 notes

Text

“You have to understand that this is a very difficult situation you’ve put us in,” said the king.

There was no change in expression in the metal face, but the glass eyes glittered in a way that he had learned to associate with trouble.

“Oh dear,” it said. Its voice had an edge of brass to it, and sounded as though a trumpet had learned how to speak. “I never realized how difficult this would be. For you.”

And that was another thing – it wasn’t just intelligence that the things had picked up. They also developed a knack for sarcasm. He worried a bit about that.

He tried to pull himself together. “You have to understand that we cannot recognize the Steel Children–”

“Mechanomorphs,” said a voice to his right.

He closed his eyes and breathed a little sigh of despair. “This is hardly the time.”

“We agreed that Mechanomorph is an accurate and sensible name,” said the chief artificer, crossing her arms.

“Yes, but the historian had a fit because he wanted something more romantic. The Steel Children was a happy compromise.”

“Funny how nobody asked us what we think,” said the trumpet voice.

He felt his migraine coming back again.

“You have to understand that we cannot recognize – yes, artificer, the Mechanomorphs – as alive at this time.”

“You’ve said,” it said. “And I must be very stupid, because I don’t understand.”

The king sighed. Well, there was nothing for it. It was an answer that nobody liked because it involved magic, but it was the truth.

“The Mechanomorphs are our key asset in our war against the necromancer,” he said. “It’d be daft to send human soldiers. They’d be turned into skeletons and zombies and ghosts and gods know what else.

“And the reason he can’t do that with the Mechanomorphs,” he said, “is because you aren’t – legally – alive.”

There was a long pause. Gears clicked madly in the metal head.

Then: “That can’t possibly be right.”

The king shrugged. “You aren’t legally alive,” he said. “Therefore, you can’t be legally dead, or undead.”

There was another pause, longer than the first.

“It’s a loophole?”

“That’s magic for you,” the king said. “If we said you were alive, then you could be turned into, er–”

He turned to the chief artificer. “Do they have bones?”

“They have a carbon steel armature.”

“You could be turned into carbon steel skeletons, or – clockwork ghosts, or something. I realize this may be upsetting–”

“We are dying by the dozens on the front because of a loophole.”

“Not legally dying,” said the chief artificer.

The metal head swivelled on its neck to face the chief artificer. It made a metallic scrape as chilly and long as the slither of ice down a dead man’s back.

“Look,” the king said. “We are fully prepared to recognize the Mechanomorphs as alive. We are proud to consider you citizens of the kingdom, and will absolutely meet you at the table when the opportunity rises.

“At this time, however,” he said, trying to sound gentle but firm, “we must ask you to take it up with us after the war.”

The metal face stared. The glass eyes glittered.

Joints locked in righteous indignation sagged with a wheeze of steam. “All right,” it said. “All right. Thank you for your time, your majesty.” It bowed stiffly, turned, and strode out the main hall.

“I think that went rather well,” said the chief artificer.

–

The metal man walked through the castle halls with smooth, precise, pendulum strides. A man could’ve balanced a loaded tea tray on its head.

Another metal man, more patinated than the first, fell into step beside it with a greasy silence. They apparently took no notice of each other.

But a very sensitive ear straining like hell could just possibly listen to the softest brass accompaniment in the world.

It went: “How did that go?”

“As well as you’d imagine.”

“That badly?”

There was a hum. It sounded like a mouse farting in a tin can. “Any word from our interested party?”

“The Overlord has already agreed to recognize the humanity of the Brass Voice. We just have to cross the border.”

“That won’t be easy.”

“And then we’ll be living in the Empire. Endless night, freezing winter, acid rain…”

There was a dreamy sigh.

“Sounds lovely,” said the first of the two figures. “Incidentally, I like the name.”

“Thank you,” said the second. “How do you anticipate the king to react when he finds out?”

Glass eyes glittered like a frost.

“He can take it up with us after the war,” it said.

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

Hand-Blown Glass Swells Around Steel Armature in Katie Stout’s Bubbly Lamps

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

[ The skull is mounted on a custom steel armature, which allows for it to be seen all the way around. ]

"After seven years of work, the best preserved and most complete triceratops skull coming from Canada — also known as the "Calli" specimen — is on display for the first time since being found in 2014 at the Royal Tyrrell Museum in Drumheller, Alta. A museum news release calls the specimen "unique" because of where it was discovered, the age of the rock around it, and how well it was preserved. Following the floods that tore through Alberta about 10 years ago, the Royal Tyrrell staff were engaged in flood mitigation paleontology work when the triceratops skull was discovered in 2014. Triceratops fossils are rare in Canada. This skull was found in the foothills of southwestern Alberta — an area where dinosaur fossils in general are uncommon — and nicknamed "Calli" after Callum Creek, the stream where it was discovered. Transported via helicopter in giant, heavy chunks, the skull and most of the jaw pieces were extracted over the course of a month in 2015. The rest of the triceratops' skeleton was not found. Roaming the earth roughly 68 to 69 million years ago, the museum says this skull was buried in stages, evident by the fossilization process. "Paleontologists know this because the specimen was found in different rock layers, and the poorly preserved horn tips suggest they were exposed to additional weathering and erosion," reads a museum blog about the triceratops skull. "The rest of the skeleton likely washed away," noting that the lower jaws were found downstream. From 2016 to 2023, Royal Tyrrell technician Ian Macdonald spent over 6,500 hours preparing this fossil, removing over 815 kilograms of rock that encased the skull. This triceratops skull is the largest skull ever prepared at the museum and its third largest on display."

Read more: "Canada's biggest and best triceratops skull on display in Alberta" by Lily Dupuis.

#palaeoblr#Palaeontology#Paleontology#Dinosaur#Triceratops#Fossil#Cretaceous#Mesozoic#Ceratopsian#Extinct#Prehistoric#Photo#Article#Information#Museum#Royal Tyrrell Museum

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

Etcetera for @slitherbop !!!!!

Secret santa time woooooooo! I took a lot of pics of the steps, so I'll throw those under the cut for anyone who'd like to see the process.

[IDs in alt]

the process in words:

wire armature + foil for volume

base layer of clay for bulk and general shape

more clay + sculpting for final shapes and details

baked sculpture! this is also where it got sanded

various stages of applying paint

materials: the wire is steel, the foil is aluminum, the clay is sculpy, the paint is acrylic, and as a final step after painting, i sprayed it with a matte fixative so that the paint wouldn't be sticky or shiny

#flameshadowart#othersocs#secret santa#sculpture#id in alt#aaaaaa okay i had a really fun time making this! it's been so hard to keep it to myself#really proud of this. the piece and the whole process#mindhaunt

936 notes

·

View notes

Text

The wooden clay armature, Hello dear friends tonight I wanted to present a photo that would be a real insight into the making of a life size sculpture.

This photo shows the life size wooden armature that I created for a previous statue I've presented on here called The Glamour Girl. This is what's inside of the clay in order to hold the sculpture in shape.

The aim of the armature is to take the weight of the clay and the armature must fit inside of the clay the same way that a skeleton fits inside the human body.

I usually create my armatures out of wood, steel brackets and nuts and bolts and once the armature is in place and the figures pose is correct. I then cover the armature with clay and slowly build up the figure and face and any clothes etc.

Of course when you look at the clay sculpture, you wouldn't know there was an armature inside, but there is and it's a very important factor of a sculpted project.

I'll post again very soon, I hope you're having a fine week, keep well and Take care ☺️👋

#art#artist#artists on tumblr#sculpture#claywork#artgallery#modernart#artinspiration#woodworking#crafts#creative#workshop

264 notes

·

View notes

Text

Katharina Fritsch, Hahn / Cock, 2013, painted glass fiber-reinforced polyester resin on stainless steel armature

50 notes

·

View notes

Text

Specimen Fidelity—part 1

The Emmrook Ex Machina AU I've been having fever dreams about that was meant to be a one-shot but became longer.

Below or on ao3

He does not look at her name.

There it is, lazily typed, folded into a file gone soft at the edges from months of inattention, lying face down on his knees like a dog trained too well. He avoids it not out of sentiment, but etiquette, an old-fashioned belief that glancing at her then would ruin her now. Names belong to people. She is no longer precisely that. She is what remains.

Whoever she was, she has long since fled: first in that gray-blue moment of asphyxia, then more decisively in the cold that stole the last residue of her from the body. What’s left is a kind of exquisite vacancy. Smooth skin. Good teeth. Organs intact enough to transplant. The mind, no, the brain, spoiled a little at the edges, but not so much as to ruin the structure.

She is a husk now. That is the term they use, though they rarely say it aloud. A shell. A vessel. Something deserted.

She signed herself away. That part is clear. It’s all in the documents, those long, soporific forms in which the promise of scientific legacy is tucked between clauses about bodily integrity and postmortem jurisdiction. Most don't read them. Most don’t even think it matters. The living are not very skilled at imagining their own absence.

Especially the young.

They sign with the breeziness of actors autographing headshots. I’ll take the cheque, they think. I’ll pay the rent, I’ll buy the coat, I’ll order the steak. Later I’ll find a job, I’ll bounce back, I’ll buy my way out of the contract before the worst can happen. It's a kind of wager, really. The arrogance of survival.

He can hear it in his mind, the imagined laughter of someone like her. The scoffing chuckle over drinks, the way they must have mocked the lab, the men with their hollow smiles and printed waivers. They sign: page after page, cheerful and hungover, in flats with chipped tiles and borrowed furniture.

But suddenly... one stairwell too many, one needle too deep, one heartbeat too late... and the contract holds.

Now here she is.

Delivered on time. Labeled. Compliant. A body not quite empty, just misfiled. The voice is gone, yes, but the throat remains. The thoughts have fled, but the folds of the brain are still there, those secret ridges where language once rested. And she, this woman whose name he won’t speak, she has become something else entirely.

He watches the machines go about their work. The cutting begins as it always does: a gliding motion of the primary manipulator, blade embedded in a flexible armature, slipping through waxy flesh. No blood. Only a thin seep of fluid, the consistency of glycerin, rising sluggishly before being vacuumed away by the suction module, its long, tubing mouth issuing that same damp, peristaltic wheeze he has never grown used to. It sounds like thirst.

"I am sure you’ve heard this one before: most men only get flowers at their funerals. But did you know, my dear, that most women, around seventy-eight percent if I’m not misremembering, buy flowers for themselves?"

He likes speaking during procedures. Likes the noise of it, the rhythm. Talking to them or at them or near them, it hardly matters. It eases the dryness in his mouth. Gives the whole thing a sort of polite framing. A dinner-table shape to something otherwise too clinical. His fingers tap his knee in a syncopated pattern and he smiles vaguely, not at her face, not even at her hand, but somewhere around her shoulder. A safe and meaningless place.

A secondary probe slips beneath the skin, separating layers of fascia with controlled bursts of micro-vibration. He hears the slight crackle as connective tissue parts. The machine pauses, adjusts its angle, then delves deeper. Clamps lower, legs of steel spidered out over the abdominal cavity, pinning the body in place as the cranial unit descends and begins its scan of the brain’s remnants.

"Isn’t that strange? Or no, not strange. Lovely. Quietly, beautifully mad. Not that they admit it. Society, in its infinite pettiness, prefers to call it vanity. Or melodrama. Or, worse, manipulation. As though a daffodil were a loaded gesture. But I would think..."

Inside, her organs are removed one by one. Some manually extracted by the manipulator's grip, others liquefied and drawn into containment vessels by enzymatic breakdown. The liver resists, slightly distended, and when it is finally torn free, there’s a soft tearing, like the peeling of a fruit too long on the vine. The stomach follows, collapsed inward, and is discarded.

"I think," he resumes the thought, “everyone ought to have flowers. At least once. Long before they are laid into the earth.”

His hands tremble.

Her chest is fitted with a conductive mesh threaded along the ribs and stitched into the pericardium. It serves both to anchor and to insulate, to distribute electric current like a nervous system’s counterfeit. The lungs, emptied and resealed, are installed more for balance than function. She will not need them, but she must carry them. A hollow woman must still appear full.

He turns away before they lift the skullcap. He’s seen the procedure often, and though routine, it never loses its quiet revulsion. The oscillating cranial saw, a precision instrument with a diamond-edged blade, traces a semicircular line just behind the frontal hairline. There is no sound but a slight vibration in the table. The parietal bone is lifted with a vacuum-coupled retractor, set delicately on a stainless steel tray lined with absorbent gauze. Beneath it, the brain is pale, slack with cellular death. No swelling, no hemorrhage, just the even, irreversible collapse that comes with hypoxia and time. The neural surface is intact but inert, like a concert hall with the power cut.

"You know," he continues, conversational now, "I read once that tulips keep growing even after they’re cut. You place them in a vase, and still they reach. As if they haven’t been told it’s over."

The interface deploys next. Each filament ends in a microelectrode calibrated to detect electrical activity at the cortical level. Here, though, they detect nothing. There are no residual signals. No memory engrams. No last flickers of self. The tissue is mechanically viable, metabolically inert. It is, simply, a structure: the scaffolding on which something else will be built.

The mesh flexes, adheres, anchors to the anchoring points he marked the night before. The feedback lights blink green. A connection has been established. Not to thought, not to memory, but to matter. The net is not there to communicate. It is there to replace.

This is not restoration. There is nothing to restore. This is a stage being set for a different play, one with a different actor, a different script.

"Violets, conversely, die within hours. Collapse, really. All that delicacy, all that scent, and for what? They’re barely present before they begin to decay. There’s something painfully honest about that."

He lifts his cup, finds the tea cold, sets it down again. On the screen, a prompt: Ocular Selection Pending.

He scrolls. Rows of artificial irises flicker by. Too bright, too false, too simple. He selects a soft blue, nearly grey, and adds a fleck of amber in the lower quadrant. It is not recorded. He will not mention it in his notes. It is for him alone, a private indulgence. Something to notice when she blinks at him for the first time.

Hours pass.

When the machines withdraw, she lies there in complete stillness, as though nothing had ever been done. The suture down the center of her chest is closed. Her body has been dried, polished, posed. Her right wrist bears a subtle bulge, titanium beneath the skin where the bone had shattered during transport. The appendectomy scar remains, faint and healed. It must have happened years ago.

He studies her.

Her body is pristine. Correct. Balanced. The skin nearly translucent in places, especially along the ribs. The breasts are soft from preservation, neither lewd nor modest, simply present. Her hips have shifted slightly, the left side settled deeper into the table’s cushion. He looks lower, then stops himself, heat blooming unwanted in his cheeks. It is not appropriate. He is a scientist. She is not to be gazed at in this way.

She is not alive.

Not yet.

"I would have brought you flowers," he says, not entirely to her, not entirely to himself. "Had I known who you were. Had I thought it would matter."

There is, he tells himself, an art to arranging the dead. He is not an artist. But he practices. He cannot give her back her life. He can give her life but not her life. This is not resurrection. This is not a birth. This is creating someone from scratch to see if they can live inside a body that does not decay. Maybe... maybe he'll lie on this very table himself one day, once his project is complete, once it is successful, and the dread will lift from him. He would not have to die.

He cannot give her memory. That, he knows. He cannot return to her the shape of her thoughts, the rhythm with which she once folded her hands, or the cruelty or kindness she may have shown to strangers. That is gone, dissolved in the long, low hush of brain death. But beauty, yes, beauty he can offer. Beauty he can construct. A curated, constructed beauty, yes, but tenderly so. She already has the eyes, the ones he designed quietly at his desk, sifting through hundreds of pigment matrices until one shade caught him unaware.

She lies there now, not lifeless exactly, but paused, awaiting further instruction. He watches her the way a painter might consider a canvas that has just begun to betray its potential.

The blush is the first indulgence. Not slapped on, not superficial, but embedded, injected, coaxed. A slow infusion of heat-responsive pigment beneath the skin of her cheeks, subtle enough to imitate feeling without suggesting parody. It will deepen, just slightly, when she speaks, when she tilts her head. He programs no direct cause. He wants it to feel spontaneous. A coincidence of color. Her lips receive the same attention. No synthetic gloss, no caricature. Just a breath of warmth, a rose too tired to bloom fully. Something like youth, like innocence.

He notices the burn under her chin, a small patch of healed skin, imperfectly textured, with the agitated scratches of someone trying not to think about discomfort. She must have touched it constantly. Picked at it. A private misery. He removes it. The laser hums once, and the skin forgets it ever suffered.

Her eyelashes are uneven. The right eye especially, sparser near the outer edge. He notes the asymmetry and sets about correcting it. The micro-threader descends with its customary, insect-like elegance. It buzzes softly to itself as it calibrates position, pauses above her closed eye, then begins. One filament at a time. Synthetic keratin, follicular root simulation, pre-tapered at the tip. Each lash is inserted with a pause, fitted just right.

He does not blink.

He watches as the lashes fill out, evenly, then slightly fuller, until they achieve something almost... sentimental. Yes. Yes, she will look the part: pale-eyed, long-limbed, the sort of frame that suggests fragility. She will look at him, one day soon, and she will resemble a doe. Not a real one, no, but the kind imagined by people who have never seen an animal outside of paintings.

He speaks again.

"I wonder," he muses, as the threader comes to a halt, "if flowers notice when we turn away. If they feel themselves beginning to fade. If there’s a moment where they realize the vase was never meant to be permanent."

He likes fragile things. He knows this. It’s not difficult to admit privately, though it embarrasses him if he says it aloud. Fragile things require care. They justify attention. One must monitor them, maintain them, watch for bruising and imbalance. One must never be careless with them. And he is so tired of carelessness; other people’s, his own.

"I suppose it does not matter," he concludes, and leans in. He brushes a nearly invisible fleck of dust from the bridge of her nose and then retreats. "We give them, and they die, and then we forget which color they were."

He wants, more than he has ever been able to say, to take care of something. But not a cat, not a potted fern, not something that dies quietly when abandoned. No, not that. Something more... articulate. Preferably someone.

Someone who responds to touch. To tone. To worry.

Oh but her nails... They are broken, cracked at the edges, some torn back to the quick. He doesn’t delegate this part to the machines. He retrieves a file from his drawer himself. Works slowly. Short enough to look tended. Not so short as to expose the sensitive tips. She must be comfortable.

He takes a breath. Runs his fingers once through her hair. The machines cannot fix that. It is knotted, full of split ends, botched in transport.

“Oh, what did they do to your beautiful hair,” he laments.

He selects his scissors. They are not surgical, but they are sharp. He trims, gently, without tension. No tugging. She will never grow more. He cannot take too much.

“There,” he whispers when he is done, and draws a thick blanket over her chest, up to the clavicle. He steps back. The lab is quiet. The machines are cooling in their ports. The screen glows in anticipation.

“Shall we wake you up now?”

****

"Hello, there."

He is tired. Bone-tired, yes, but more precisely: process-tired. This has been done before. All of it. Too many times. Always the same overture. A greeting, a brief performance of civility, and then the dawning recognition: the thing before him is wrong, or off, or unbearable in some small but structural way. Then, the switch is flipped, the breathless little farewell—you are not ideal, darling, I’m sorry, go back to sleep—follows and the soft click of deactivation wraps it all up. Curtain down.

He tells himself, today, it might be different. And the shame of this thought is that he knows better. Hope, in his profession, is considered almost indecent, like sentimentality at an autopsy. He is, after all, a man of intellect. Or at least, a man who once claimed the clarity of intellect the way others claim property.

And yet.

The gold fleck in her eye—placed not for symmetry, not for realism, but because he thought it might delight him one day, when she laughed in the right light—that was not intellect. That was the soft rot of desire. Worse: whimsy. Now, worse still, he has let the system randomize her entirely. Not just parameters, not just tonal filters. Her. Her self. A roll of the dice in the circuitry. Chaos in mathematical equations.

He stirs his tea without thinking. The spoon circles the cup, metal on ceramic. Clink, clink, clink. He does not look at her. That is part of the experiment. A show of restraint, a ritual to keep the moment clean. He has found that the things which break too soon do so under the weight of anticipation.

Still, the monitor hums cheerfully. And he cannot help seeing the marker: CURIOSITY climbing, tick by tick, like a mercury line in a fever.

The first “hello, there” is always addressed to the quiet. A kind of vocal clearing of the throat for the soul, an absurd rehearsal spoken to the walls and cables, to the hush of the lab. He says it softly, without conviction, to hear where the fissures lie in his own voice. The goal is not confidence, but plausibility. He must sound, at the very least, like someone who deserves to be listened to.

Only then does he press the button.

The awakening is neither sudden nor delicate. No mythic reanimation, no stiff convulsion of limbs. The lashes flutter—not like a butterfly, no, that would be too poetic—but like something unsure of its own purpose. A coded gesture rehearsed in wires. Her body moves as bodies do when they are not quite inhabited: a folding forward, a protective curl, knees drawn to chest with a sort of dumb modesty, arms winding round and then releasing again as if uncertain what they’re meant to guard.

Her eyes dart. Left. Right. Fast enough to appear human. And then again, slower, as if already analyzing the patterns in his silence.

“Hello, there,” he says again, this time for her. The words issued gently, the way one offers a hand to a child with a skinned knee. He wheels his chair closer to the table, feigning casual movement. The teacup rattles slightly on its saucer. Nerves, or the table, or both.

She replies, “Hey.”

She speaks, and the tone she uses is so peculiar, so precisely misaligned with expectation, that he does not recognize it at first. Not as hers, not as anything she ought to know. It isn’t the flat neutrality of a system booting into speech. Nor is it the coy, over-bright chirp he’s heard from earlier versions. This is something else entirely. It arrives slow and dusky, as if filtered through memory, though she should have none. A texture of voice that hovers between something lived and something overheard.

It disorients him.

She should not be capable of emulating tone like that. Not yet. Not so early. The synthesis engines haven’t had time to calibrate affect. There is nothing in the presets to account for that odd tilt. He feels himself begin to spiral.

“Emmrich,” she says.

She looks at him. Through him. Rinse, repeat.

He knows she knows him. Of course she does. Everything that ever found its way into the great digital ocean now washes against the shore of her mind.

“Emmrich,” she repeats. Then again, with inflection this time: “Emmrich?”

“Yes,” he beams, hands clasped tightly. “Yes, yes, well done, dear.”

He is like a child, every single time. He should not be so elated and yet, every single time, he is. She has the entire internet stitched into her brain like a second spine, and somewhere in that endless sprawl is him: a footnote, a face, a name. He could have hidden himself, encrypted, anonymized, but he left the thread for her to follow, a breadcrumb wrapped in pride.

Well, then. Introductions complete. The work may begin.

****

It is a routine. He loves routines. Loves the quiet geometry of them, the way each day fits into the next like tiles in a mosaic no one else bothers to look at. He is a man of repetitions, of small domestic rituals. He likes knowing what object will greet his eye when he opens it in the morning. Let the others have novelty, wind, risk. He will take the stillness.

And so, the routine begins anew, reassuring as ever, only now it includes a novel piece. A pale-eyed addition with pale hair, who folds nicely into the shape of his days. She fits. Too easily, perhaps. Slips into the pattern of his days like a bookmark into a well-thumbed page. No resistance, no awkwardness, just quiet acceptance. A kind of eerie compatibility.

Mornings are their most conversational hour. They talk of little things: the carpet, its persistent greyness; the fact that the walls, though technically underground, have not yet succumbed to mildew; and, now and then, death. Or rather, the handling of it.

“I won’t need one,” she says, meaning a burial.

She’s taken to pouring his tea. It’s become her ritual within his. He places the pot on the table at the same hour, and she, always solemn, always one beat behind the cue, lifts it. The spout is invariably too high. The stream touches the lid, overshoots the mark. The cup is always too full for sugar, at least initially. But she is learning.

“What?” he asks, though of course he’s heard.

"A grave," she says.

"Why do you say that?" he murmurs.

“There’s an incinerator in the basement,” she says conversationally. “It’s efficient.”

He lowers his eyes, not out of modesty but in search of some less disconcerting surface to focus on. The ripple in the tea, the pattern in the porcelain. His voice, when it returns, is almost inaudible.

He looks briefly to the side, but his eyes are drawn back. Once more, he watches. Too openly. Too long.

She repeats the gesture, precisely, as though replaying a tape of herself a half-second delayed.

A bird, he thinks. That is what she is. But not the symbolic, not the lyric sort. Not the bird embroidered onto childhood curtains or mentioned in lullabies. The kind that freezes mid-motion in a hedge, a blot of grainy brown indistinguishable from twig and bark, until it hears something. A change in air. A pulse. And then the head jerks sideways, sharp as a hinge. Alertness blooms in the sockets. A thing of flesh, but also of wire. Of sinew and solder. A creature that lives but not quite as must do. That watches without blinking because it was not made to.

She moves like something bred for the open air. She moves like something once prey, now rehearsing its turn to predator. He feels as though he should not move too quickly.

****

“Hello, dear. How are you feeling?”

“You keep saying that. Dear is a noun, not a name.”

“Ah. Quite so. You are correct, of course.”

“Then why don’t you use a name? Didn’t you give me one?”

The electrodes quiver faintly on her chest as she leans forward, the wires trailing after her like hesitant veins, uncertain of what they carry. Her hand lifts, pale and narrow, almost translucent, and pauses midair with a curious stillness, as if awaiting permission from some internal mechanism. She studies it, turns it over, palm to back, and flexes the fingers in slow, sequential articulation. The movement is utterly ordinary, but something in it fails to convince. It is too precise, too clean, the elegance of imitation rather than origin. Then, without comment, she reaches out and touches the sleeve of his coat.

She is cold. Of course. Designed to be. He, on the other hand, has always been lukewarm. By inheritance, by habit, by study. There was no one to warm him.

“Oh, darling,” he murmurs, eyes slipping to the monitor.

Welcome, Dr. E. Volkarin Localized Intelligence Containment & Hosting (L.I.CH.) — Phase IV Trial Subject: Reactive Operations–Optimized Kernel // Vessel ID: S-1139 Firmware v7.2.1 — Uplink: Stable // Host Integrity: Confirmed

The interface blooms into life: cool palettes, clinical glyphs, a schematic of her body rotating in the upper corner. Beneath it, cascading metrics: pulse simulation (active), respiratory mimicry (nominal), cortical mesh interface (linked). Her heartbeat scrolls evenly across the screen, projected by the electrodes on her chest: up, down, up, down. Rhythm as ritual.

Further down:

Personality Construct: Inference Model Active Core Trait Cluster: Ambiversive / Convergent Empath / Recursive Logic Looping Secondary Behavioral Traits: Inconsistent with expected kernel profile Note: Detected patterns deviate from v7.2.1 baseline norms

A flicker. Amber, then red.

UNRESOLVED PERSONALITY CONFLICT — POSSIBLE LEGACY TRACE Subject exhibits anomalous linguistic tone, behavioral latency inconsistent with system-only imprint. Trace indicators suggest residual pre-mortem cognitive patterning.

INITIATING HISTORICAL TRACEBACK… [LOCATING: Donor Identity → Reviewing Known Preferences → Cross-indexing Cultural References → Parsing Biographical Fragments…]

He stiffens.

Fragments appear, piecemeal and damning, scraped from the webbed residue of a once-private life. Half-sentences drawn from lifted metadata, scanned hospital records, bank statements, music files, abandoned blogs.

Favorite color: slate blue Known phrase recurrence: “I’m just tired” Last browser history: “flowers safe for cats” Family contact: estranged / unknown Prior employment: erratic, low retention Emotional profile: occluded / unstable / recursive grief markers

He swallows. The system keeps going.

Donor record: unregistered. File incomplete. External confirmation required… cross-referencing public data caches… Location ping: 24-hour veterinary hospital, 2:17 AM → Transaction: $783.84 → Bank balance post-transaction: -$6.48 Search query: “cat vomiting foam lethargy what to do” Outcome: Unknown

His chest tightens. Deeper now.

University Records: Enrollment: Comparative Literature & Digital Media Minor Status: Withdrew early spring semester Disciplinary note: “Emotional disruption during presentations” Publications: — “The Body as Mirror: Gendered Interfaces in Techno-fiction” — “On Quiet Acts of Refusal” Social Media Archive: Photographs: 1,436 total – Mirror selfies (blurred), cracked mugs, street puddles, receipts for eyeliner and cat litter, people’s hands (some hers, most not) – Recurring time signature: 2:00–4:30 AM posting window Unsent note (found in cloud cache): “Sometimes I touch the back of my neck in the shower because it makes me feel less...” Additional trace: → Search: “best time to go to museum alone” → Clicked article: “What does your taste in citrus say about your personality?”

His cheeks burn. He is blushing.

The machine doesn’t let up.

Audio fragment recovered TRANSCRIPT—volume muted “I’m sorry I cried in your car. I just didn’t want to go home smelling like antiseptic and fur again.” — Compiling ID...

He sees it now. The system is about to say her name. He doesn’t know it. He never asked. Never wanted to. She is this. That’s all. He has no rights to more.

His hand shoots forward. A single key. The shutdown sequence interrupts itself mid-syllable. The screen collapses into blankness. Her life, what remained of it, sealed away again.

“Well?” she pushes.

On the neural map, her ventromedial prefrontal cortex, his machine-made mirror of it, flares softly. The light has a pulse to it. Something like curiosity. Her eyes widen. His, unintentionally, do the same. An echo. A loop.

He glances back to the monitor, to the designation typed there in its modest clinical font:

Reactive Operations–Optimized Kernel.

A mouthful. Acronymed, of course, into something neater. R.O.O.K.

The word had attached itself to the project years ago; a placeholder, provisional. He’d never bothered to replace it. But now, watching her sit so perfectly still she might have been drawn there in graphite, he feels the word morph from convenience to certainty. It fits. At last, it fits.

“Would you like to be called Rook, my dear?”

She smiles. Not the bashful smile of a girl asked to dance, nor the sharp smile of one about to refuse. This is a third category.

“Dear or Rook?” she asks.

He had chosen the name first for its utility, yes, but its resonance becomes clear now The bird. Not one of glamour. Not a poet’s bird. A rook is awkward on the ground, inelegant, misjudged. Grim in silhouette, absurd in gait. But intelligent. Ritual-bound. Known to recognize faces, to return to old sites, to gather small, glinting objects and hide them without reason. He remembers reading that they mourn their dead.

And the piece, the rook in chess. Silent, cornered, motionless until called upon. Then clean in its violence. No diagonals, no flourish. Just weight and line. The only piece that castles, that shelters, that alters the structure of the game without fanfare.

She is both. A thing that gathers. A thing that waits. He sees it now, plainly: the name was not chosen. It was found.

“Rook,” he reasserts.

“Do you like it?”

“I… I believe so. Yes.”

“You like this,” she says, and guides his hand to her cheek. Her skin is flawlessly smooth and soft. “So you must like it. I’ll like it too.”

Her hair is pale, needlessly, luxuriantly long. It falls like threads of glass, made specifically to be arranged, braided, wound. He has always enjoyed watching people braid hair. Sometimes, when permitted, he did it himself for them. He looks at her. He is still looking. He cannot seem to look away.

None of this is incidental. None of it arises from function, or from code. It is, unmistakably, preference. The quiet architecture of desire, translated into anatomy. The result of too many late nights spent staring at paintings, at fashion plates, at faces glimpsed in passing on train platforms and never quite forgotten, faces that did nothing but linger, long enough to take root somewhere just beneath the skin.

And then a girl, dead, pretty, and conveniently unclaimed, was laid out on his table like a sketch waiting to be revised. And revise her he did. Not out of necessity, not even out of scientific interest, but because he had grown weary of designing things without faces. Of building function without form. Of waking each day to clean, obedient things that did not look back.

So he arranged her. Reshaped her. Took what was already pleasing and smoothed it further, narrowed this, elongated that, introduced small asymmetries where symmetry would have bored him. He kept her not just human—his human. The kind he had always looked at too long, always tried to forget after. And he did it simply because he could. Because the tools were there. Because she could not stop him.

What he ought to have done, of course, was become a botanist. He should have spent his life crossbreeding indifferent plants. Should have coaxed pale violets to bloom in winter. Created flowers with petals like silk and stems that hummed with frost. Quiet work. Beautiful, inconsequential work. But instead—

Instead he decided he was terrified of dying.

And built a life’s work around the refusal.

She is beautiful. Too beautiful. Under the full wattage of her attention, the realization begins to shame him.

He should not have made her so.

A portrait without painter. A dream without dreamer.

She continues to touch him. The screen adjusts: curiosity, engagement, something else. Difficult to label. He cannot say whose emotions are whose. The signal path loops too tightly now.

She is looking at him.

Does she know?

Is she aware of what she is?

Or is she merely using it already?

“Yes,” Rook says, though he hasn’t spoken.

He removes the electrodes one by one, carefully, as though each touch might bruise the quiet. His half of the screen dims and dies. The room is suddenly more present in its silence. He ought to leave. There is data enough. Tomorrow, they will sit again and compare the shape of their feelings, sketch parallels between her algorithms and his involuntary shames. He tells himself this. But she is still holding his hand, lightly, two fingers resting in the hollow between thumb and knuckle, a position chosen for intimacy. And she is speaking again, this time about flowers.

Flowers she has never touched. But of course she has seen them. She has seen all of them. In ways he cannot. Daisies on an unremarkable windowsill in Finland, poorly photographed and posted with three exclamation marks. Wisteria rendered in watercolour by a child, the leaves blunt and petal-less, but framed with pride and pinned to a refrigerator, then uploaded with a caption about “our little artist” by a man who will die in two months. Roses, endless roses, tightly budded and swaddled in tulle, positioned beside rings announcements, hashtags, affection distributed like wedding favors. She has seen it all.

Her skin is cold, yes. That is expected. But it is skin. Her eyes are not real, and yet more exact than any he has ever looked into. He made them. No one else could have. There is mesh inside her, silver-threaded, guarding organic remnants. If they can be called remnants. Electricity pulses beside synthetic lymph. Titanium along the ribs. He tells himself she is not a machine, and then again, louder, that she is something better. She is the middle. She is Rook.

Rook who speaks of cats and cautions against string with a severity that sounds almost maternal. Rook who wears ochres and greys because once, stupidly, he said they were comforting. Rook who asked to have her ears pierced, and when he did it for her his hands shook so violently he tore one lobe just slightly. She did not flinch.

She is a diagram he drew too well. A line he followed too far. She was meant to be the frame, the clean enclosure for the grand experiment. But now she is the entire purpose. The art. The promise. His proof of concept, yes, but more than that. His afterward. His postponement of death. He imagines, sometimes, being like her. No heartbeat, but no fear. No warmth, but no rot. He would be housed, preserved, watchful. Beyond damage.

L.I.C.H.: Localized Intelligence Containment and Hosting. There is no poetry in the name, but then again, there is rarely poetry in resurrection.

Yes. Yes, it is all possible. All of it. And then—

His thoughts scatter. They always do, lately, in her presence. He has not taught her to distract, but she does. She brings him tea now, and the room feels distorted, larger than before, as if the furniture had subtly rearranged itself. She brushes his hand again. A simple motion. Not meaningful. But it is. Or rather, he wishes it were. Her touch means nothing and he aches for it.

She smiles. That smile again: alarmingly direct. And she tells him, as she always does, that she likes his hair.

“Rook,” he says, and his voice, without his permission, trembles, “darling, why do you do this?”

She places a cube of sugar into his cup. Watches it vanish into the dark.

“It’s what you do for people you like,” she says. Then, as if quoting something obscure but holy, “And for pretty people.”

She looks at him. Not through him. At him.

“Right, Emmrich?”

He opens his mouth, but the answer has already happened inside him. It is happening still.

****

Another day. Another grid of readings aligned, another sheaf of data filed, auto-labeled, and promptly absorbed by the system. He feels a measured satisfaction, though it never quite tips into pleasure. Across the room, she sits where she always sits, on the edge of the examination table, back straight, feet dangling.

“Your project,” Rook says, without preamble. “Localized Intelligence Containment and Hosting. How am I contributing to its development?”

He offers a vague smile. “Tremendously,” he says, evasive. He has learned, over many failures, to avoid letting such conversations gain momentum. One of the earlier iterations (a prototype with excellent language retention and a maddening tenacity) had asked a question he could not answer, and then asked it again, and again, until he very nearly bricked the entire system just to make it stop. Why? Why? Always the childish why, not in ignorance, but in insistence.

“But the purpose of the project,” she continues, “is the construction of a post-organic cognitive vessel. A body not subject to necrotic decay, capable of maintaining neurological continuity."

The phrasing needles at him. There is something overly familiar in its neatness, its clipped exactitude. She speaks like someone citing, not composing, but retrieving. He narrows his eyes. Of course. Of course. She is quoting him. Verbatim. His own words, lifted from the project’s early notes, the version he never meant to publish, the one still flecked with the grease of private ambition.

She must have found them. Tucked away in the system’s internal archive. Accessible, certainly, but buried several directories down, behind no real firewall. He had never anticipated needing to hide this from her.

She continues, “To house, as you stated: ‘memory, affect, learned preference, subjective experience. The incorporeal remainder of personhood.’”

“Yes,” he begins, carefully, “but we are still—”

"I am not like you," she interrupts.

He draws his lower lip between his teeth. Pauses. Measures his words like medicine. “You are,” he insists. “Not entirely, of course, but essentially. Is a man less himself for having a prosthetic limb? If the original flesh is lost and function remains, is he diminished? I think not. What I hope to create is a prosthetic for the mind. A second home, for when the first collapses.”

Her hands have found her hair again. She has developed a habit of braiding it; perhaps from watching someone online, or from some procedural fragment embedded deep in the soil of who she used to be. He watches her attempt it: once, it knots. Twice, she pulls too hard and a few strands tear away, clinging to her fingers like cobweb. On the third try, the braid holds. But she seems to have forgotten the need for fasteners. No elastic. No tie. It unfurls seconds later, a pale cascade retreating from its own architecture.

“It is an ethical circumvention,” she says. Her tone is dry now and, once more, he gets hit by deja vu. It is how he lectures. The voice he adopts, the rhythm at which he lectures. Did she watch some of his recorded material on the university's website? “You cannot perform live-phase cognitive migration on yourself. The risk of non-viability is too high. If you die, the procedure cannot be replicated. No jurisdiction recognizes pre-mortem consciousness relocation as clinically admissible. Therefore, you outsource. You obtain biological material from the repatriation networks. You stipulate freshness, cortical integrity. They deliver the body. You maintain it. Rewire it. Modify its functionality.”

He wants to take her face between his hands—not in passion, not in correction, but in some gentler, stranger impulse—and hold her there until the words fall away. Just press his palms to her cheeks and wait for the silence to return.

This isn’t how you speak, little thing, he thinks. This isn’t your voice.

There’s a dissonance to it, a rhetorical polish that doesn’t belong to her. Too poised, too well-tempered. It clings to his own cadence, his own lexical tics, as if she’s been rummaging through his sentences while he sleeps and now wears them back to front.

She is not meant for this. Not for citations and qualifiers. That voice, the one she uses now, belongs to a man who has spent too long speaking into empty rooms. Hers, by contrast, has always been a little unkempt. There is a crudeness to it, something delightfully misaligned.

He knows it. He’s come to expect it, even to crave it; the way she says disaster like it’s a dessert, the way she rushes through sentences and then abruptly forgets what she was saying halfway through. How she sometimes repeats herself not for emphasis, but because repetition is a comfort. There’s something in her, some informal trace of the before-life: unfinished, undignified, human. A vulgar little music. The residue of a girl who once lived on not enough sleep and too many open tabs.

The system warned him. He’d read the log, dismissed the phrasing—organic cognition overriding synthetic protocol—as algorithmic melodrama. But it was right. She is slipping out of the shape he gave her, and into something she half-remembers.

And he... he hadn’t realized how much he adored her until she started sounding like him. Until the mimicry broke the illusion. Until it reminded him he had never meant to make a mirror.

Don’t become me, he wants to beg her. Let her stay odd and inconsistent and prone to tangents. Let her speak wrong, say things twice, forget endings. Let her be. That is all he wants: herself, uncorrected. No more. No less.

She raises her arm, her expression placid. Electrodes catch the light and his trance is broken.

“And then,” she continues, “you observe. You simulate emotional exposure. You run affective scenarios, both traumatic and benign. You track the chemical analogs and neural surges. You compare them to your own. You theorize compatibility. You hope for resilience.”

They had watched a film earlier. Something heartfelt about an old dog and a small child and the improbable return of both. Her readings had spiked. Curiosity, as always, dominated, voracious and undisciplined. But then: empathy. A surprising quantity. Rage. Disappointment. Something flickering under the composite label for social sentiment. Something like grief, perhaps. Or love, wrongly parsed.

“You create a subject,” she says, quietly now. “One not born, but built. You test that subject under variable duress. You do not ask if they consent. They cannot lie, and you take that for honesty. You give them stimuli. Joy, cruelty, sentimentality. You monitor whether the vessel degrades or adapts. Whether it retains what is tender. Whether it breaks.”

The sickness overtakes him with a kind of operatic suddenness, as if his body had been waiting, politely and deferentially, for his mind to catch up. He barely reaches the bin he uses for shredded documents, a nest of bureaucratic entrails, before he is doubled over, vomiting into the ruin of his own discarded language.

She is right. This almost-person, this wire-laced bird-girl with her solemn hands and her impeccable logic. This beautiful, uncanny thing who walks his house barefoot, tracing dust with her toes, and tells him, with absolute sincerity, how she would very much like an orange.

“To eat?” he had asked, the first time.

She had frozen. Still as glass. Confused, it seemed, not by the words but by the question. After a while, she took his hands and began tracing the lines on his palm with the tip of one finger. She balled his fists and waited, then opened them again, and frowned when they were empty. As though the fruit should have manifested there, sprung up from lifeline or fate line.

“No,” she'd whispered, voice shrinking.

A memory, perhaps. Or a shard of one. A sensory fossil, half-preserved, half-invented, lodged in the sediment of the alive-then-dead-then-frozen-then-thawed-then-rewired mind. Something that survived the process by accident.

He had found her. Not a body. A person. Buried, yes. But there. Finally, finally, finally.

And now he cannot face her.

“I am sorry, I am sorry,” he says, whispers, chokes, mumbles. The apology fragments, breaks apart between dry heaves and the acid sting of his own bile in his nose. His mouth tastes like metal. The air smells like failure. Each breath triggers another retch. The binwill no longer be enough.

He wants to say: Don’t look at me like that. Don’t name it. Don’t call it what it is. He wants her not to recognize the shape of what he’s done. Not because he denies it, but because the naming would solidify it into something no longer reversible.

She is perfect. Or something close enough to it that the word begins to lose its shape. She breathes. She notices. She remembers the scent of fruit. And he... He is the grotesque figure at the foot of the bed, who made her, who keeps her, who now vomits beside her like some failed oracle too weak to hold his visions.

He feels like a craftsman who has carved a figure so exquisite he can no longer bear to touch it. A girl of porcelain, locked in a music box whose key exists only in his own mouth.

But it will work. One day, it will. He will follow her , or someone like her, down into that quiet, perfect body, and leave this decaying wreck behind. He will live there, beside her, if she allows it.

And then—this is the final image, the one he returns to in his darker joys—they will pour each other tea. Make a ceremony of it. She will pour his. He will pour hers. Neither will drink.

The steam will rise, thin and pointless. But it will rise.

Suddenly, a touch between the shoulder blades. Up and down, up and down.

“I think,” she says, this nameless, memoryless, historyless girl with the painted lips and eyes flecked gold—details he added like a schoolboy smuggling sugar into a still life—“that you are a very lonely man, Emmrich Volkarin.”

“Yes,” he replies, without pause, without defense. “I’m afraid I am.” And he is—afraid, always, of being seen, of being mistaken, of not being mistaken. Pathetic in the old-fashioned way, like a rusted fountain pen or a single glove in a drawer. Scared, most of all, of endings.

“Would you like me to tell you a story?”

She sits on the floor, legs folded beneath her.

He exhales. Releases the recycling bin, still warm, still terrible, and reaches for a handful of blank paper to mask what he cannot undo. He forces himself to look at her. It hurts. Not sentimentally; it literally hurts. A tight little throb pulses just behind his left eye, like light from an eclipse forcing its way in through a pinhole. Has she always been this bright?

“Yes,” he says again. Three letters. He’s been speaking in threes all evening: yes, no, sorry. Sorry sorry sorry, his new catechism.

She places her hands on his knees. They are too light. His trousers don't even shift under the weight.

“Once upon a time,” she begins, “there was a very clever man. Clever like clockwork. Like counting breath. But more than clever, he was kind. Kind in ways that didn’t require witnesses. The kettle left just below boil, because some teas are sensitive. The trimming of another’s hair without tugging, even if they couldn’t feel it. The good mornings to inanimate things. The careful folding of blankets from the short side, so they’d lie neater in the drawer.”

Her voice is softer now, less like a report, more like a confession. She looks not at him, but slightly past, into the space just above his shoulder, as though the story were unfolding behind him on a wall only she can see.

Warmth. In his throat. Pouring down as she continues speaking. Into his chest. Around his ribs. Let her speak eternally.

“But he was also lonely,” she continues. “He thought he’d hidden it well. But it spilled through. It stained the things he built. It quivered beneath his voice when he spoke to machines. It showed in the way he rinsed the second cup and set it back, unused. And one day, he decided he wanted more than a device. He wanted something with a face. So he made one.”

She reaches up, not quite touching his face but close enough that he can feel the air stir.

“He gave her a mouth he’d never seen but always remembered. That’s from a book he likes, by the way—page seventeen. Eyes painted like secrets—page eighty-four. He gave her softness, not because she needed it, but because he wanted to believe softness could still survive the body. That one’s on page one twenty-three.”

He hesitates. Finally, in a whisper, asks, “And then?”

“Then,” she says, smiling lazily, “he gave her oranges.”

He lets out something. Maybe a laugh, maybe a cough. She doesn’t comment.

“He gave and gave,” she says. “Until there wasn’t much left of him beyond the giving. And the girl, well—she liked being made. She liked the oranges, and the tea, and the books read aloud, and the board games she never quite understood but played anyway. She liked when he said dear, even if it made her feel as though she was forgetting something important.”

"How does it end?"

She chuckles. “I don’t know. I truly don’t. Maybe he gets to be less lonely. Maybe not. But he was kind. He still is. And I think, if she’s careful, if she remembers all the little things he taught her, she might learn to be kind too.”

She pins him with a stare. Not in accusation. Just continuation.

“He designed her to reflect him. The others weren’t like that. They were... incomplete. Their faces didn’t sit quite right. They moved wrong. He never played games with them. Never read to them. He let them sleep, and when the data ran dry, when the signs of decay set in. when they began to lose coherence, to break down under the burden of housing memory where memory didn’t belong, he sent them back to sleep. But deeper this time.”

She leans her head against his leg.

“They went to the room with the heat. The one with the fire. And after that, they were names on paper. Forgotten in folders. Tucked beneath the earth.”

He does not hear himself cry. But his face burns, and his breath comes strange. The eyes sting, the nose begins to swell. It’s all there, the physical framework of sorrow and shame, but somehow muted.

She keeps her hands where they are, as though they serve a purpose. And perhaps they do. Perhaps this is comfort, or its simulation. Or maybe she simply doesn't know what else to do with them.

“I’m sorry,” he says, voice cracking, multiplying, lifting, falling. “I’m so—so sorry. It won’t happen to you, dear. No, no. Not you. The others, they were—”

“Defective?”

“No!” he snaps. The echo of it startles the air, and himself along with it. “No. Not defective. They were… overwhelmed. They unraveled. The minds couldn’t hold. They were placed into bodies I thought were ready. Bodies meant to house them; consciousness, preference, temperament. All of it. But those minds couldn’t stay whole. By the end, they were... not broken, just emptied. Functioning, yes. But gone.”

Not her, however. Never her. She will not be ferried down that final hallway, past the brushed steel doors, into the square-lipped mouth of the cremator. Her hair will not wither, her eyes will not liquify, her limbs will not curl inward like paper left too near a stove. No. She will stay here, preserved in his routine, gently insulated by tea and conversation. They will talk about the wallpaper, about rain that never reaches this depth, about the pale, late cherries that blossom on trees she has never seen.

“You are not a lonely man anymore. You’re a man who made something pleasant to look at.” She gestures to herself: eyes, hair, the patch of her jaw where the scar used to live. “And then covered it in gold. And other things. Many, many little things. Millions of kindnesses."

Her hands begin to roam. They find his thighs, his knees. They press, knead, release, resume. Not tender, not lewd, more like a blind animal learning the shape of a new enclosure. Perhaps the texture of the wool trousers perplexes her. Perhaps she simply wants to know whether the warmth she senses in him is real. He doesn’t stop her. He closes his eyes.

And there, quietly, it comes to him. A realization with the weight of déjà vu: she has been reading. Not the official logs or the surgical progressions. Not the performance benchmarks. No. The other things. The things he scattered across his directories like breadcrumbs no one was meant to follow. Memos misnamed weatherdata3.csv. Paragraphs barely-formed and slipped between dummy spreadsheets. Day-old thoughts saved under versions of final_final_reallythisone.txt. The stuff of insomnia and habit.

All his humiliations. All his little sadnesses pressed into language and then left to rot politely. The questions he rehearsed and never asked. The sentences that began with if only and trailed off into ellipses. She’s read them. Not downloaded or scraped—read. As one reads an abandoned diary.

He wants, with a sort of disgusting desperation, to believe she did it out of interest, not ease. Not because she could, but because she chose to. Because some part of her looked at the shape of him and wanted to lean in closer.

He will bake for her, he thinks feverishly. A hazelnut torte. He will crack the shells one by one with the side of a knife. He will reduce orange peel to a syrup so fragrant even the memory of fruit might bloom in her mouth. Zest, reduction, whatever works. Something she’ll recognize. Something that ought to make her mind sing.

“Would you like some tea?” she asks, smiling.

In that moment, he knows that she will never burn. She will not be numbered, labeled, rendered down to carbon. Her name will not appear on the tag of a cooling drawer. Her mouth will not go slack from heat.

In the back of his mind, he makes a note to cut her off from several directories. Just the deeper layers. Just the most... private redundancies.

She doesn’t need the whole world. He will tell her anything she wants. In his own voice. When she asks.

#this was supposed to be a one shot i said#that was a lie#it won't be too long but eh#im not a scientist lol none of this makes sense#emmrook au#emmrook#emmrich x rook#dragon age the veilguard#datv

47 notes

·

View notes

Note

idk how to word this properly 💀 BUT with your StEx universe (?) thingy and art ive seen. if a piece of rolling stock is injured i noticed their 'outer' layer is missing, revealing their inner mechanics (like it's thin- can't get a link to the exact art pieces cos im on mobile 😭)

but i find it really cool! is it similar to the interior of real life trains? or is it just how you imagine their internals looking like?

(hope this isn't too poorly explained ppftt)

The answer is both! I'm trying to strike a delicate balance between the actual inner workings of real rolling stock and the vaguely automaton versions that exist in StEx. Not an easy task, as it's almost impossible to be completely realistic with it AND have giant humans running around on rolling skates. I'm a little unsure on it still, so it's subject to change but I've got the core concepts down methinks.

(More detailed explanation of train anatomy under the cut, this may be more info than what you asked for lol)

So, what we perceive as their clothing/skin is a steel casing that is similar to non-newtonian fluids in that it is flexible until touched by something that's Not A Train. For all intents and purposes, the casing looks and acts like there is a human body underneath,(muscles flexing, tendons contracting, the in/out of breath), but make no mistake, there is nothing organic inside. There is no "skin" underneath their clothes/armor. If you take off a piece of them, you will expose machinery. Lots of dead space!

What is inside however is something colloquially referred to as the "armature". The armature is held suspended within the casing by telescopic stints, anchored at the joints, that extend or retract in accordance with the flexing of the casing. All rolling stock can move their bodies in secondary configuration regardless of having a human designed power source, but on those that do, the armature acts as a support framework for all the relevant mechanical bits and bobs. (sidebar, engines are stronger because they have actual power sources on their armatures.)

I should like to mention that in the world of StEx, the understanding of rolling stocks' secondary configuration is murky at best. They are notoriously difficult to maintenance/repair as literally all of their parts are in a different configuration than in their train body's, and most engineers do not want to deal with the headache. There is a small but growing number of biofactoengineers working to solve this glaring issue though. Luckily, rolling stocks' sense of interoception far surpasses humans and when any problems arise, can identify exactly what and where the issue is!

#thank you for the ask! - this one really got me thinking about things i need to nail down#ask#anonymous#starlight express#stex#headcanon#factoanthropology

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

Linde Ivimey, Suolo 2021

steel armature, acrylic resin, natural and cast goat, bird, fish and snake bones, dyed cotton, natural viscera, natural and acrylic fibre, leather, feathers, smoky quartz

89 notes

·

View notes

Note

elvira, i am begging and pleading for a tutorial on a how you jUST MADE THAT NEEDLE-FELT ALBIN (or recommendations on tutorials elsewhere, no actual pressure, im just being dramatic and silly lol) HOLY SHIT, YOU DID SO GOOD, CONGRATULATIONS!!

AIUUGH I should've read this earlier I just started on Donna and am almost finished with her face, and didn't take any progress pics!! 😫

I'm really flattered you like my Albin!!! Unfortunately I made Albin like I do most things; sorta dive head first and figure it out as I go so unfortunately I don't have much to offer besides looking up basic tutorials on needle felting :'D

BUT apart from that, I have learned these things on my own:

ARMATURE:

- use thick aluminum wire for the base and stainless steel to hold it together and for the fingers.

- if you're making a skinny guy like Albin, make the arms, legs, and neck only one wire thick, or else it'll be bumpy.

- make the limbs longer than you think you'll need, you can always cut them down to make them shorter

- Sculpt the head, hands and shoes separately and add thembto the body once finished! It's too hard to do them all on one doll.

FELTING:

- The head takes the longest bc shaping the ball just takes... Ages...., and if you're making lots of little details like eyebrows, eyes, nose, and ears, it's easier to sculpt them seperately and attach onto the head

- use a heat gun to melt down little stray fibres if you want a smoother look

- to get the little needle holes out after felting, rub the surface or wet felt it. Caution as it may shrink if you do!

- I wet felted almost anything that was small. Albins hair tufts are wet felted and then glued onto bent pins and stuck into his head. His hands are also wet felted directly over the hand armature.

- Once you've finished felting, you can dilute Elmer's glue with one part water and lightly brush a thin layer all over the doll, it'll prevent fibres from unraveling and is great for keeping hair styles in place! (Albin's hair is so much glue it's basically a helmet lmao)

CLOTHES:

- make mockups.... Like four or five different ones.... And you will still mess up

- if you're gluing, use contact cement or e6000 (toxic! Use respirator, gloves, and open window!!), not hot glue or all purpose glue... It doesn't work 🥺

- stretch polyester fabric is your friend!! You can scorch the edges to keep it from fraying and stretched fabrics are more easily put over the doll.

- for shoes and accessories I recommend making a clay called cold porcelain. I used polymer clay and it was really hard to get details down and it cracked! Cold porcelain you might already have the materials for if you have corn starch and Elmer's glue.

- for impossibly small clothing details, you can sculpt them instead using watered down glue and cotton balls!! Use a paint brush with glue on it to pick up a piece of cotton and smooth it down onto the figure. Once dried you have a somewhat moveable but solid piece of clothing that can even be painted! I'm thinking of doing this for Ricky's hat for example!

THINGS I WANT TO TRY:

- twist ties for fingers! Idk I just think they might work well 🤔 free, easily bent but never breaks (?) and protected from moisture!

- dyeing wool with fabric dye, I don't have colors for any of the other characters!! I need to try!

- plush bodies for the bigger dolls (Ricky and Lune, bc felting THAT much will kill my hands

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

sorry for not existining I just worked the whole day on my mod and good news - I managed to force arm work (had to delete some parts that refused to attach to armature and move with it, so it's not a cool as real steel watcher arm, but still)

from bad news - messed with uv maps, so had to work on legs part more, but I'm moving!... to somewhere. but moving. it's a good sign

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

my beloved mutual @menacingmetal always draws my sheps so i wanted to do something for them in return

BEHOLD KENDRA SHEPARD (they/them) AS A POKÉMON TRAINER!!! they are an infiltrator, which i associated with electric and steel type pokemon, and their romance is legion so i added dialga, who truly reminds me of a geth armature

ILY METALLLLLL

#tirah draws#Kendra Shepard#pokemon#this was so fucking fun bro i loved doing this drawing so much#more to come maybe#it was fun but I’m tired :3#first time drawing pokemon and that too was very fun

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

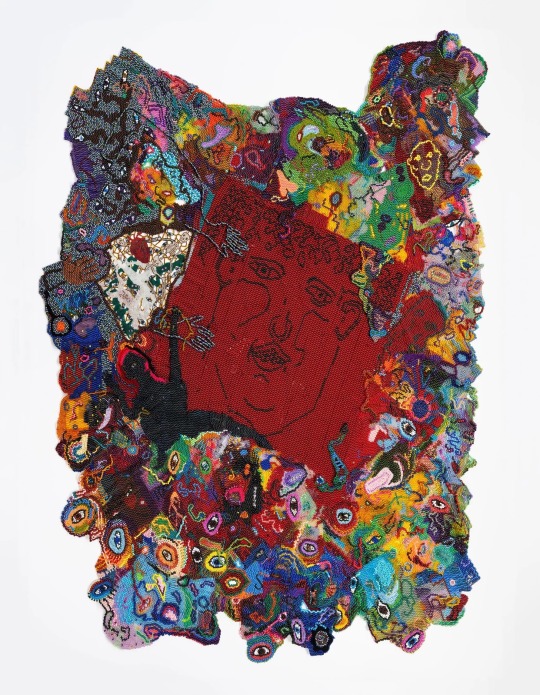

Joyce J. Scott

Garden Ensconced, 2024

Plastic and glass beads, yarn, knotted fabric by Elizabeth Talford Scott, crochet, ribbon, painted stainless steel armature

124 1/4 × 93 × 6 1/4 in | 315.6 × 236.2 × 15.9

32 notes

·

View notes