#stalinallee

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Ansichtskarte

Berlin - Stalinallee. mit Café Budapest und Warschau.

Halle, Berlin: Postreiter Verlag, Halle - Felix Setecki, Berlin (V11/28 Z 205/67)

1957

#Berlin#Stalinallee#1950er#1957#Karl Marx Allee#Cafe Warschau#Cafe Budapest#Nationale Bautradition#Städtebau der DDR#Friedrichshain#Alltagskultur der DDR#Ansichtskartenfotografie#Ansichtskartenfotografie der DDR#deltiology#Vintage Postcard

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

Together with the Weissenhof and Dammerstock Estates the Hansaviertel in Berlin is one of the most important showcases of modern architecture in Germany. It was conceived for the 1957 international building exhibition „Interbau“ and involved more than 50 architects from all over the Western world, among them Walter Gropius, Oscar Niemeyer, Arne Jacobsen and Egon Eiermann. At the same time it was a reaction to the GDR’s model project Stalinallee in East-Berlin which the initiators sought to outshine with a gathering of modernist buildings representing contemporary visions of dwelling.

That these visions over the course of almost 70 years haven’t lost any of their appeal proves the present volume by Anna Frey and Caterina Rancho: in „Hansaviertel Portraits“, published recently by Distanz Verlag, the authors revisit the architecture of the Hansaviertel and portray twelve locals in their apartments. The result is a wonderful stroll through the neighborhood in which the reader gets to stop at each building, receives information about it and its architect(s) and occasionally is invited in to peek into the apartments of some of the inhabitants. The first stop is Daniel’s apartment in Paul Baumgarten’s Eternithaus: with a great attention to the historic detail he has winkled out the lofty character of the apartment, underscored by few but carefully selected pieces of furniture. In fact, the attention to detail as well as respect and appreciation for the original character of each apartment is what connects all portrayed individuals. Anna and Thomas for example, who live in the so-called „Schwedenhaus“ by Fritz Jaenecke and Sten Samuelson, have juxtaposed the clean and brightly lit character of their apartment with jazzy furnishings that come into their own perfectly in the otherwise reduced ambience.

These two examples already showcase the core quality of book, i.e. the closeness to its subjects: from the get-go the reader, thanks to the beautiful photographs and texts, feels like taking a stroll through the Hansaviertel’s splendid architecture and is given the opportunity to take in its special atmosphere, a characteristic that makes the book a very entertaining read!

#nachkriegsmoderne#nachkriegsarchitektur#architecture#germany#architecture book#interbau#book#distanz verlag#architectural history

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

Nach dem Aufstand des 17. Juni Ließ der Sekretär des Schriftstellerverbands In der Stalinallee Flugblätter verteilen Auf denen zu lesen war, daß das Volk Das Vertrauen der Regierung verscherzt habe Und es nur durch verdoppelte Arbeit zurückerobern könne. Wäre es da Nicht doch einfacher, die Regierung Löste das Volk auf und Wählte ein anderes?

-Bertolt Brecht, "Die Lösung", 1953.

There's been a thousand hot takes about the latest US election, and I see no need to write anything original. Brecht's classic seems to apply to the Democrats this time.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Solution

Bertolt Brecht

After the uprising of the 17th of June The Secretary of the Writers' Union Had leaflets distributed on the Stalinallee Which stated that the people Had squandered the confidence of the government And could only win it back By redoubled work [quotas]. Would it not in that case Be simpler for the government To dissolve the people And elect another?

0 notes

Photo

From Social Demands to Political Uprising

Bloodshed During the Workers’ Strike in Plovdiv

On the evening of May 3, 1953, workers at the former “Tomasivan” tobacco factory in Plovdiv staged a revolt. Night shift workers took control of the factory, throwing out the guards and closing down operations. They barricaded themselves inside one of the largest tobacco warehouses, known as “Ivan Karadzhov.” The situation escalated when, on the morning of May 4, militia forces surrounded the warehouse and locked the doors from the outside.

The Spread of the Strike

That same morning, workers from two other warehouses, “Stefan Karadzhiev” and “Georgi Ivanov,” mostly women, also stopped working in solidarity. The strikers in the first warehouse broke down the doors and forced the militia guards to retreat. Soon, workers from all three warehouses gathered for an improvised rally in the factory courtyard. The crowd grew as more workers who were not on shift joined in, and by this time, the number of protesters reached several thousand, according to eyewitness accounts Private Balkan Tours.

The workers demanded that the government restore the favorable working conditions they had before the factory was nationalized. High-ranking party leaders, including Interior Minister Anton Yugov, arrived from Sofia to address the crowd. However, when he attempted to speak, protesters threw stones at him, forcing him to retreat. In response, the militia received orders to open fire on the crowd.

Violence and Repression

The violence escalated quickly. Several strikers were shot dead on the spot, including two women. Approximately 50 others were wounded, and hundreds were arrested. Kiril Dzhavezov, the leader of the strikers, was captured near the railway station and shot dead. The exact number of fatalities remains unclear, as the authorities imposed strict bans on any publicity or discussion of the events.

The Spark of Uprisings in Eastern Europe

The uprising in Plovdiv was not an isolated incident; it was part of a larger wave of unrest across Eastern Europe. The spark that ignited this wave first occurred in 1953 in Stalinallee, in East Berlin. Increased quotas for construction workers were the direct cause of their revolt. Workers from other sectors and ordinary citizens soon joined the protests.

On June 15, 1953, around 80 workers began a protest parade under the slogan “We demand reduced quotas.” As the day went on, hundreds of other workers joined the march. When they reached the trade union house, they found it locked and then headed towards the government building. By lunchtime, thousands had gathered outside, raising both union demands and political slogans such as “Down with the government!” and “Free elections!”

The events in Plovdiv and East Berlin exemplify the growing discontent among workers in communist Eastern Europe during the early 1950s. The protests were driven by legitimate social demands but quickly escalated into political uprisings against oppressive regimes. These incidents highlighted the widespread frustration with government policies and the desire for change, ultimately shaping the political landscape of the region. The bloodshed and repression experienced by the workers serve as a stark reminder of the struggles for rights and freedoms that characterized this turbulent period in history.

0 notes

Photo

From Social Demands to Political Uprising

Bloodshed During the Workers’ Strike in Plovdiv

On the evening of May 3, 1953, workers at the former “Tomasivan” tobacco factory in Plovdiv staged a revolt. Night shift workers took control of the factory, throwing out the guards and closing down operations. They barricaded themselves inside one of the largest tobacco warehouses, known as “Ivan Karadzhov.” The situation escalated when, on the morning of May 4, militia forces surrounded the warehouse and locked the doors from the outside.

The Spread of the Strike

That same morning, workers from two other warehouses, “Stefan Karadzhiev” and “Georgi Ivanov,” mostly women, also stopped working in solidarity. The strikers in the first warehouse broke down the doors and forced the militia guards to retreat. Soon, workers from all three warehouses gathered for an improvised rally in the factory courtyard. The crowd grew as more workers who were not on shift joined in, and by this time, the number of protesters reached several thousand, according to eyewitness accounts Private Balkan Tours.

The workers demanded that the government restore the favorable working conditions they had before the factory was nationalized. High-ranking party leaders, including Interior Minister Anton Yugov, arrived from Sofia to address the crowd. However, when he attempted to speak, protesters threw stones at him, forcing him to retreat. In response, the militia received orders to open fire on the crowd.

Violence and Repression

The violence escalated quickly. Several strikers were shot dead on the spot, including two women. Approximately 50 others were wounded, and hundreds were arrested. Kiril Dzhavezov, the leader of the strikers, was captured near the railway station and shot dead. The exact number of fatalities remains unclear, as the authorities imposed strict bans on any publicity or discussion of the events.

The Spark of Uprisings in Eastern Europe

The uprising in Plovdiv was not an isolated incident; it was part of a larger wave of unrest across Eastern Europe. The spark that ignited this wave first occurred in 1953 in Stalinallee, in East Berlin. Increased quotas for construction workers were the direct cause of their revolt. Workers from other sectors and ordinary citizens soon joined the protests.

On June 15, 1953, around 80 workers began a protest parade under the slogan “We demand reduced quotas.” As the day went on, hundreds of other workers joined the march. When they reached the trade union house, they found it locked and then headed towards the government building. By lunchtime, thousands had gathered outside, raising both union demands and political slogans such as “Down with the government!” and “Free elections!”

The events in Plovdiv and East Berlin exemplify the growing discontent among workers in communist Eastern Europe during the early 1950s. The protests were driven by legitimate social demands but quickly escalated into political uprisings against oppressive regimes. These incidents highlighted the widespread frustration with government policies and the desire for change, ultimately shaping the political landscape of the region. The bloodshed and repression experienced by the workers serve as a stark reminder of the struggles for rights and freedoms that characterized this turbulent period in history.

0 notes

Photo

From Social Demands to Political Uprising

Bloodshed During the Workers’ Strike in Plovdiv

On the evening of May 3, 1953, workers at the former “Tomasivan” tobacco factory in Plovdiv staged a revolt. Night shift workers took control of the factory, throwing out the guards and closing down operations. They barricaded themselves inside one of the largest tobacco warehouses, known as “Ivan Karadzhov.” The situation escalated when, on the morning of May 4, militia forces surrounded the warehouse and locked the doors from the outside.

The Spread of the Strike

That same morning, workers from two other warehouses, “Stefan Karadzhiev” and “Georgi Ivanov,” mostly women, also stopped working in solidarity. The strikers in the first warehouse broke down the doors and forced the militia guards to retreat. Soon, workers from all three warehouses gathered for an improvised rally in the factory courtyard. The crowd grew as more workers who were not on shift joined in, and by this time, the number of protesters reached several thousand, according to eyewitness accounts Private Balkan Tours.

The workers demanded that the government restore the favorable working conditions they had before the factory was nationalized. High-ranking party leaders, including Interior Minister Anton Yugov, arrived from Sofia to address the crowd. However, when he attempted to speak, protesters threw stones at him, forcing him to retreat. In response, the militia received orders to open fire on the crowd.

Violence and Repression

The violence escalated quickly. Several strikers were shot dead on the spot, including two women. Approximately 50 others were wounded, and hundreds were arrested. Kiril Dzhavezov, the leader of the strikers, was captured near the railway station and shot dead. The exact number of fatalities remains unclear, as the authorities imposed strict bans on any publicity or discussion of the events.

The Spark of Uprisings in Eastern Europe

The uprising in Plovdiv was not an isolated incident; it was part of a larger wave of unrest across Eastern Europe. The spark that ignited this wave first occurred in 1953 in Stalinallee, in East Berlin. Increased quotas for construction workers were the direct cause of their revolt. Workers from other sectors and ordinary citizens soon joined the protests.

On June 15, 1953, around 80 workers began a protest parade under the slogan “We demand reduced quotas.” As the day went on, hundreds of other workers joined the march. When they reached the trade union house, they found it locked and then headed towards the government building. By lunchtime, thousands had gathered outside, raising both union demands and political slogans such as “Down with the government!” and “Free elections!”

The events in Plovdiv and East Berlin exemplify the growing discontent among workers in communist Eastern Europe during the early 1950s. The protests were driven by legitimate social demands but quickly escalated into political uprisings against oppressive regimes. These incidents highlighted the widespread frustration with government policies and the desire for change, ultimately shaping the political landscape of the region. The bloodshed and repression experienced by the workers serve as a stark reminder of the struggles for rights and freedoms that characterized this turbulent period in history.

0 notes

Photo

From Social Demands to Political Uprising

Bloodshed During the Workers’ Strike in Plovdiv

On the evening of May 3, 1953, workers at the former “Tomasivan” tobacco factory in Plovdiv staged a revolt. Night shift workers took control of the factory, throwing out the guards and closing down operations. They barricaded themselves inside one of the largest tobacco warehouses, known as “Ivan Karadzhov.” The situation escalated when, on the morning of May 4, militia forces surrounded the warehouse and locked the doors from the outside.

The Spread of the Strike

That same morning, workers from two other warehouses, “Stefan Karadzhiev” and “Georgi Ivanov,” mostly women, also stopped working in solidarity. The strikers in the first warehouse broke down the doors and forced the militia guards to retreat. Soon, workers from all three warehouses gathered for an improvised rally in the factory courtyard. The crowd grew as more workers who were not on shift joined in, and by this time, the number of protesters reached several thousand, according to eyewitness accounts Private Balkan Tours.

The workers demanded that the government restore the favorable working conditions they had before the factory was nationalized. High-ranking party leaders, including Interior Minister Anton Yugov, arrived from Sofia to address the crowd. However, when he attempted to speak, protesters threw stones at him, forcing him to retreat. In response, the militia received orders to open fire on the crowd.

Violence and Repression

The violence escalated quickly. Several strikers were shot dead on the spot, including two women. Approximately 50 others were wounded, and hundreds were arrested. Kiril Dzhavezov, the leader of the strikers, was captured near the railway station and shot dead. The exact number of fatalities remains unclear, as the authorities imposed strict bans on any publicity or discussion of the events.

The Spark of Uprisings in Eastern Europe

The uprising in Plovdiv was not an isolated incident; it was part of a larger wave of unrest across Eastern Europe. The spark that ignited this wave first occurred in 1953 in Stalinallee, in East Berlin. Increased quotas for construction workers were the direct cause of their revolt. Workers from other sectors and ordinary citizens soon joined the protests.

On June 15, 1953, around 80 workers began a protest parade under the slogan “We demand reduced quotas.” As the day went on, hundreds of other workers joined the march. When they reached the trade union house, they found it locked and then headed towards the government building. By lunchtime, thousands had gathered outside, raising both union demands and political slogans such as “Down with the government!” and “Free elections!”

The events in Plovdiv and East Berlin exemplify the growing discontent among workers in communist Eastern Europe during the early 1950s. The protests were driven by legitimate social demands but quickly escalated into political uprisings against oppressive regimes. These incidents highlighted the widespread frustration with government policies and the desire for change, ultimately shaping the political landscape of the region. The bloodshed and repression experienced by the workers serve as a stark reminder of the struggles for rights and freedoms that characterized this turbulent period in history.

0 notes

Text

The other reference I like is Brecht's The Solution.

After the uprising of the 17th of June The Secretary of the Writers' Union Had leaflets distributed on the Stalinallee Which stated that the people Had squandered the confidence of the government And could only win it back By redoubled work [quotas]. Would it not in that case Be simpler for the government To dissolve the people And elect another?

"Voting doesnt work because not enough people in my country will vote for MY version of communism. We need a violent overthrow of the government to MAKE this happen"

10K notes

·

View notes

Text

Victory Column

Postcard from Germany The Victory Column and Hansa Quarters. The Victory Column is a monument in Berlin, Germany. Designed by Heinrich Strack after 1864 to commemorate the Prussian victory in the Second Schleswig War. In the East, the GDR had shown with Stalinallee what fantastic architecture it was capable of building: workers’ palaces! The West had to counter. In the Hansaviertel (Hansa…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

Ansichtskarte

Berlin - Stalinallee Block E-Süd

Berlin: Nationales Aufbaukomitee Berlin (Ag 145/54 DDR III/9/89 5108)

1954

#Nationales Aufbaukomitee Berlin#Berlin#Friedrichshain#Stalinallee#1950er#1954#Philokartie#DDRPhilokartie#akBerlinFriedrichshain#Architekturphilokartie#DDRArchitektur#GDRArchitecture#SocialistArchitecture#VintagePostcard#deltiology#Ansichtskartenfotografie#AnsichtskartenfotografieDerDDR#NationaleBautradition

27 notes

·

View notes

Photo

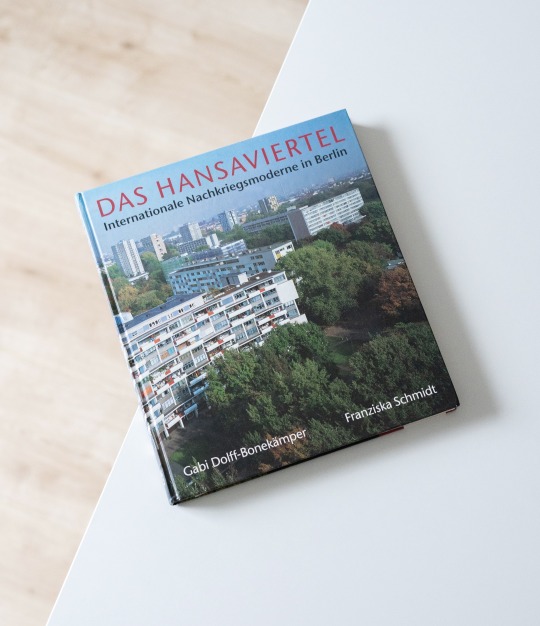

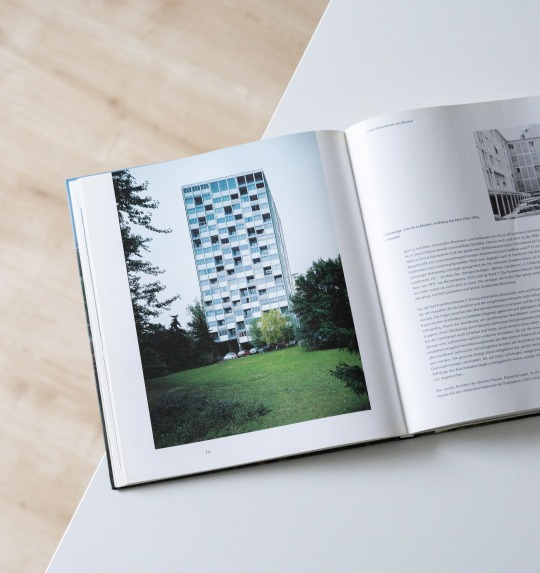

Only 12 years after the end of WWII the 1957 Interbau building exhibition gathered progressive international and German architects in Berlin to design houses, apartment buildings and infrastructural architecture for the Hansaviertel which had been almost entirely destroyed by the war. The Interbau dates back to 1951 when the Senate of West-Berlin contemplated the idea of having a building exhibition draw attention to the city and respond to the construction of the Stalinallee in East-Berlin. After a jury had selected Gerhard Jobst’s and Willy Kreuer’s town planning design among 98 competition entries a roster of potential architects was drawn up, among them International masters like Arne Jacobsen, Oscar Niemeyer and Walter Gropius but also Egon Eiermann, Sep Ruf or Paul Schneider-Esleben as representatives of German postwar modernism. The resulting quarter ultimately comprised 1,300 housing units, a library, a shopping center, two churches and a day care center.

Still the best overview of the Hansaviertel’s history and architecture provides the monograph “Das Hansaviertel - Internationale Nachkriegsmoderne in Berlin” by Gabi Dolff-Bonekämper and photographer Franziska Schmidt, published in 1999 by Verlag Bauwesen. Divided into two distinctive parts the book provides a comprehensive account of the events leading up to the 1957 Interbau, the underlying urban planning as well as the architects involved. Interestingly the authors have also included a collection of international reactions to the Interbau, largely positive and affirmative of the initiator’s intention to reestablish Germany on the stage of international progressive architecture. The second and larger part of the book is then dedicated to the architecture: structured along tours Dolff-Bonekämper explores the different parts of the quarter and with the help of plans and Schmidt’s photographs examines each building in great detail. Since she also covers buildings (the school, the Haus der Kulturen der Welt and the Unité d’Habitation) related to the Interbau but located outside the Hansaviertel a complete picture of the new Hansaviertel and the many innovative buildings emerges. A great read!

#interbau 1957#archietctural history#nachkriegsarchitektur#nachkriegsmoderne#architektur#berlin#architecture book#book#monograph

37 notes

·

View notes

Text

Stalin Ohr im Cafe Sibylle.

pic https://fr.restaurantguru.com/Cafe-Sibylle-Berlin

"Einige mit der Vernichtung des Denkmals beauftragte Bauarbeiter hatten unbemerkt kleine Stücke der zertrümmerten Statue an sich genommen. Der Brigadier Wolf übergab nach der politischen Wende der Geschichtswerkstatt Stalinallee ein Ohr und ein Stück des Schnurrbartes und berichtete über Details.

Im Januar 2018 stellte die Gedenkstätte Berlin-Hohenschönhausen kurzzeitig eine Kopie des Denkmals am Original-Standort auf. Sie hatte die Statue in der Mongolei ausfindig gemacht und nach Berlin gebracht, um sie hier in einer Ausstellung zu zeigen.[18]

Das Café Sibylle in der Karl-Marx-Allee 72 zeigt Artefakte des Denkmals und informiert, nicht dem aktuellen Forschungsstand entsprechend, zu seiner Geschichte und zur Stalin- bzw. Karl-Marx-Allee. Dabei sind Kopien von Teilen des Denkmals (u. a. ein Ohr) ausgestellt, die Originale befinden sich im Militärhistorischen Museum der Bundeswehr in Dresden."

"Die Skulptur wurde eingeschmolzen und ihr Material beim Guss von Tierfiguren für den Berliner Tierpark wiederverwendet, vermutlich für ein Eselchen, einen Elch und einen Säbelzahntiger."

https://www.bz-berlin.de/archiv-artikel/hier-kam-stalin-in-die-karl-marx-allee-geflogen

1 note

·

View note

Text

Poema "Solución" por Brecht.

Tras la sublevación del 17 de Junio la Secretaria de la Unión de Escritores Hizo repartir folletos en el Stalinallee indicando que el pueblo había perdido la confianza del gobierno Y podía ganarla de nuevo solamente Con esfuerzos redoblados. ¿No sería más simple En ese caso para el gobierno disolver el pueblo Y elegir otro?

0 notes

Photo

*

*

flieg ich durch die welt ...

#helen of troy#helena#manfred noa#bavaria#emelka#1924#die nibelungen#fritz lang#panzerkreuzer potemkin#sergej eisenstein#herbert achternbusch#rainer werner fassbinder#olympia#münchen#nofretete#boris godunov#paris#stalinallee#miss perestroika#aquirre der zorn gottes

6 notes

·

View notes

Photo

From Social Demands to Political Uprising

Bloodshed During the Workers’ Strike in Plovdiv

On the evening of May 3, 1953, workers at the former “Tomasivan” tobacco factory in Plovdiv staged a revolt. Night shift workers took control of the factory, throwing out the guards and closing down operations. They barricaded themselves inside one of the largest tobacco warehouses, known as “Ivan Karadzhov.” The situation escalated when, on the morning of May 4, militia forces surrounded the warehouse and locked the doors from the outside.

The Spread of the Strike

That same morning, workers from two other warehouses, “Stefan Karadzhiev” and “Georgi Ivanov,” mostly women, also stopped working in solidarity. The strikers in the first warehouse broke down the doors and forced the militia guards to retreat. Soon, workers from all three warehouses gathered for an improvised rally in the factory courtyard. The crowd grew as more workers who were not on shift joined in, and by this time, the number of protesters reached several thousand, according to eyewitness accounts Private Balkan Tours.

The workers demanded that the government restore the favorable working conditions they had before the factory was nationalized. High-ranking party leaders, including Interior Minister Anton Yugov, arrived from Sofia to address the crowd. However, when he attempted to speak, protesters threw stones at him, forcing him to retreat. In response, the militia received orders to open fire on the crowd.

Violence and Repression

The violence escalated quickly. Several strikers were shot dead on the spot, including two women. Approximately 50 others were wounded, and hundreds were arrested. Kiril Dzhavezov, the leader of the strikers, was captured near the railway station and shot dead. The exact number of fatalities remains unclear, as the authorities imposed strict bans on any publicity or discussion of the events.

The Spark of Uprisings in Eastern Europe

The uprising in Plovdiv was not an isolated incident; it was part of a larger wave of unrest across Eastern Europe. The spark that ignited this wave first occurred in 1953 in Stalinallee, in East Berlin. Increased quotas for construction workers were the direct cause of their revolt. Workers from other sectors and ordinary citizens soon joined the protests.

On June 15, 1953, around 80 workers began a protest parade under the slogan “We demand reduced quotas.” As the day went on, hundreds of other workers joined the march. When they reached the trade union house, they found it locked and then headed towards the government building. By lunchtime, thousands had gathered outside, raising both union demands and political slogans such as “Down with the government!” and “Free elections!”

The events in Plovdiv and East Berlin exemplify the growing discontent among workers in communist Eastern Europe during the early 1950s. The protests were driven by legitimate social demands but quickly escalated into political uprisings against oppressive regimes. These incidents highlighted the widespread frustration with government policies and the desire for change, ultimately shaping the political landscape of the region. The bloodshed and repression experienced by the workers serve as a stark reminder of the struggles for rights and freedoms that characterized this turbulent period in history.

0 notes