#sousveillance

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Link

In the latest instance of an emerging trend, a woman on TikTok yesterday (June 25) posted a video of a man on a plane: after eavesdropping on his conversation, she accused him of cheating, listed a number of identifying details, and urged her followers to help track down his wife to break the news. This bid for help was successful; both the man and his wife were quickly identified, and their names were posted online, along with photos of their family. The post went wildly viral, and the response was split down the middle. For some, the post was a disturbing act of spying, bordering on harassment; for others, it was “accountability reporting” – effectively a form of activism.

This kind of digital surveillance isn’t new (I’ve written about it before), but what makes this iteration different is the posture of moral crusade – it’s digital vigilantism; the TikTok equivalent of a citizen’s arrest. There have always been cases where it’s permissible, or even in the public good, to share footage of someone acting badly in public (if you’re screaming racist abuse at someone, who cares about your right to privacy), but the category of behaviour that invites this response seems to be expanding all the time, to the point it includes intimate situations which don’t concern anyone but the people involved. The element of high-minded sanctimony makes this version of digital surveillance even more obnoxious than posting a video of someone dancing awkwardly at a club or shitting themselves on the tube – at least those people generally know they’re being mean; they’re not deluded enough to think they are advancing a cause or holding anyone accountable.

44 notes

·

View notes

Text

Social Media, Sousveillance, and the Self (The Three S’s!) REVISED AND BASS BOOSTED

Preface: I posted this as a gaggle of thoughts some months ago, which you can see if you scroll down just a little bit on my blog. These thoughts were decently unorganized and months later, after slow broiling and marinating these thoughts some more, I decided to turn it into a real conjecture of sorts.

Very special thanks + shoutout to my philosophy professor Daniel Rodriguez-Navas for his careful, thoughtful, constructive, and encouraging guidance throughout the development this paper.

Most young people are socially expected to have a form of social media now, and especially expected to have some form of personal information be public. Many find it strange if one does not post photos of themselves online. Most of us, generation Z, are expected and encouraged to contribute to this massive user-curated database, and in exchange, we are able to receive more attention than what was previously fathomable in the form of likes, shares, and comments. This attention is addictive, debilitating, heart-wrenching and hyper-fixated. It has never been possible in human history to access this many people at once, to be heard by this many people and hear this many people. The digital space has never been “natural” - though depending on particular definitions of “natural”, the transhumanist may argue that the digital space is the next step in evolution; an extension of the human realm. But we were not eased into this digital realm, we were thrown, many of us at a very young age, into this realm with a violent and perverted amount of freedom, enticed by information overload and the addiction of attention. The societal over-exposure to the current climate and habits of social media platforms has had not only a detrimental effect on users’ physical health and self esteem, but has also created an uncanny simulacrum of the ways in which we interact and present ourselves with/to others in real life. The incorporation of social media in our everyday lives has solely transformed the ways in which we love, hate, cry and laugh, prioritize - at others and especially ourselves.

The new product of attention has become a pinnacle of desire; and we pay with sensation, with shock, with beauty and individuality. When these technological experiments first came out, our young, malleable, dissatisfied minds were the first to latch on. Our parents critiqued this, which made the project even more successful. But it is not a phase like our parents said it would be. They caved. All it took was a few years of normalization - advertising, attention, and they too, became hooked. A 2021 Pew research center study found that 91% of US adults aged 30-49 use online platforms, slightly decreasing in ages 50-64 with 83%, and 49% in adults aged 65 and up. We no longer even have an ancient antagonist to complain about “kids these days”. It has become all free and liberated, no shame in this addiction because the algorithms have improved, proved to be impenetrable in its strategy.

What we now value is increasingly impacted by the digital sphere, riddled with advertisements for particularly desirable lifestyles. With a life revolving so much around the aspect of the digital realm, and with the digital realm being created on the foundation of capital pursuit, value is no longer personal. Life and culture are no longer personal. The personal is no longer personal. Lee Artz, author of “Global Entertainment Media: A Critical Introduction” describes how world culture no longer stems from local cultures, created by people. Instead, TNMCs (TransNational Media Corporations) create a culture based off of the pursuit of production and wealth, skillfully peppered with some features of local culture for the sake of relatability and familiarity, sold under the guise of “cultural diversity”.

The transaction is subtle - we buy a fix of attention, a sense of connection in exchange for personal information, the more intimate the better. Post a photo of yourself - better if you are wearing less, better if you are doing something vulnerable, intimate, better with more controversy. A 2018 study by Bell, Cassarly and Dunbar examines the extent to which young women aged 18-24 posted self-images that were sexually suggestive and its correlation with the amount of “likes” and online engagement one would receive. The results concluded that this type of positive engagement on sexually suggestive photos encouraged young women to post more of them. As young people have been subject to this reward system for longer and whilst our young minds are still developing, we have a heightened sensitivity to this type of social reward. The oversharing of one’s sexuality and body essentially transfers ownership, or feeling of entitlement to the consumer, who possesses the power of encouraging it, or negatively engaging.

It’s not only sexualization that receives this engagement - the new phenomenon of oversharing personal information on the internet, especially now that less people are choosing to stay anonymous on the internet than ever before, has become essentially a new norm. Simply opening the Tik Tok app will present you with people in their homes, talking to the camera about intimate, vulnerable, and often embarrassing stories in full detail. The fascination with this seemingly raw and unfiltered form of content, or sexualized content, taps into a different type of perversion in the human psyche; this type of content, because it is in a way so humiliatingly honest, welcomes the most brutal responses. Though many love informational oversharing, with netizens commonly expressing that it makes them feel better about themselves, or relieved in its relatability, a 2022 study concluded that informational oversharing stems from anxiety and alienation from society, where people desperately try to find intimacy, attention, and relatability in their vulnerability. “Better to shock than to bore” - or relevance over irrelevance, has become the subconscious logic. Relevance is emphasized more than ever now, where even “normal” people have a fixation on “staying relevant”, much like a celebrity would traditionally have. The “digital footprint” is no longer about reservation or preservation, it is about sensation and impact. That’s the new age of fame, and it is stupidly easy, stupidly addictive.

I feel like this newfound addiction to attention and instant gratification has shifted our collective values. We value privacy much less, in favor of attention. Social media platforms have taught us that we can receive a great amount of attention, validation, and discourse just by trading one’s privacy, the value of which has been artificially decreased by TNMCs just as the value of fame/exposure has been artificially increased.

The strategy of self advertisement is now learned by young adolescents before, or even instead, of the strategies of self preservation and self protection. No real cyber literacy is taught - it is simply learned through experience. Older generations and very young children do not have the years of developmental experience infiltrated by the digital space to garner an awareness of the real-life-to-digital dissonance. The two are not as easily separable to someone naive to the difference of impact they have. The digital space gives one, in a way, the illusion of ultimate privacy, almost like it encourages the exploitation of your deepest vulnerabilities. You can tell your innermost secrets out loud, alone, in the comfort of your own room, and be heard and seen by millions. Accounts of very young children or older people often go viral because their personas online are often either the most vulnerable pure reflection of their reality, or they are presenting themselves in a very obviously curated way, where they naively act like how they think people on the internet should act. These types of accounts are almost always loved by the public in an exploitative or patronizing way, where the humor lies in the fact that they do not act on social media in the way that shows a sense of “getting it”, part of this dreadful post-ironic, terminally blasé attitude that has plagued those with experience-based, shame-based digital literacy. I propose that this attitude is formed out of self protection, or a need to present oneself as somebody who is impenetrable in vulnerability.

The internet is where anything is said mostly without real life consequences - and this is another large aspect of why the digital space is addictive. One gets addicted to the honesty, which coaxes you into delving into and producing opinions that one would not think of producing in real life. Because of this honesty, people often purposefully think of things to critique and reasons to attack. But this is also a product of the oppressive real-life social norms of courtesy and the overbearing expectation of niceness. The digital realm is, in a way, a solace where we can reject that. But that freedom of communication is simply on the other extreme end of the spectrum of healthy communication. The pendulum never stops in the healthy middle. I often like to think of all my social media comments as if they were being said to me, in person, by the people behind these profiles. They usually have photos of themselves publicly posted. They say vile things because I am not real. To them, and funny enough, oftentimes to myself as well, I am just a monkey that is dancing on the circuit board inside their phones, in their pocket, accessible at any time and able to be deleted at any time. I am so beautifully insignificant, so temporary, and yet it inexplicably gives me a sense of a permanent presence - a stable one, that will not fade. I am not immune to the fetishization of fame.

Schlosser identifies self presentation versus self disclosure; self presentation being a goal-oriented, strategic, and curated presentation of the self, with self disclosure being sharing factual information to another about oneself, regardless of its impact on one’s social reputation. She finds that the internet gives affordance for self disclosure due to the option of anonymity, but also discourages disclosure through unfiltered and open audience feedback. Through personal observation, I believe that the issue is more complex, and calls for a more nuanced discussion than whether social platforms promote or discourage presentation or disclosure - because this discussion suggests that there is no blurred line between the curated self and the objective self. Even in a non-social media context, it is hard to differentiate between genuine and performative behavior, since it is so hard for a subject to differentiate and admit to it. With how engrossed most people are within their digital selves, I will argue that it is all presentative - and that even content that feels like disclosure is self presentation. Is there really no motive in disclosure, as Schlosser puts it?

Maybe disclosure is innocence - a naieveté that is ironically revered and unironically feared. With the internet being an automatic concrete archive of one’s opinions and expression and a machine that almost always guarantees a consequence, there is a saying that has emerged in recent years: “be careful of what you say on the internet”. This is referring to the fear of getting “canceled” for saying something problematic, or to the possibility of publicly embarrassing oneself whether in action, speech or aesthetics. When people have an understanding of this ruthless internet system, everything one says and does on the internet is purposefully curated, with extra care in the desired effect of the content. Even when content is created for the purpose of self-degradation or self embarrassment for humor, it is still careful to not be too vulnerable, or too weird.

Referring back to my earlier observation of how content from young children or older people who do not necessarily “get” the internet often go viral, I think that maybe this form of simple, naive, innocent and vulnerable content is the only true disclosure that exists on the internet - unintentional disclosure. Unintentional disclosure also can come forth in times where one may try to present a lie to consumers, and are proven false. I believe that this is why these videos and posts go viral - we all truly do love disclosure. We love honesty and vulnerability, proof of humanness and unintentional subjects of endearment. I do believe that my current generation is striving for real human connection, closeness, and earnest communication in this epidemic of loneliness, spearheaded by the cave-like illusion of comfort that technology brings. We’re just scared - I know I am - because who wouldn’t be, as involuntary test subjects for mystifying technologies?

Altman and Taylor proposed the social penetration theory (SPT), where surface-level relationships can develop into much deeper ones, where the seal of intimacy gets penetrated, in a sense, through the sharing of personal information - self disclosure. The goal within self disclosure is social penetration, which is more present than ever in the context of social media, except social media does not give the affordance of other strategies to gain social penetration - such as a slow, gradual relationship, face-to-face contact, and mutual acknowledgement. Since content creators do not have these other affordances, I will argue that they feel the urge to go to extremes with a performance of self-disclosure, for the main goal of social penetration, creating parasocial relationships.

The parasocial relationship is the driving force of the use of influencers in modern day advertisement. Simulating intimate, honest relationships is what the content creator strives for, because that is what creates the most engagement and makes for the best product endorsements, encouraged and funded by TNMCs. It is what the consumer also loves to consume, because without the added aspects of social penetration such as a slow, gradual relationship, face-to-face contact, and mutual acknowledgement, the consumer is able to have a fundamentally not whole but idealized version of the curator, where the curator’s personality can seem much more wholesome, specified, honest and relatable than the personality of anyone that the consumer could know in real life.

The influencer blurs the line between “normal” person and celebrity. Celebrities used to be elusive creatures, where a sighting of them outside of a movie or magazine was considered fascinating - because celebrities used to be untouchable. They were Gods rarely among men and worshiped for their unapproachability. The influencer in the digital age has fundamentally transformed the concept of fame into one based not necessarily on traditional talent, but on social penetration, controversy, and very importantly, attractiveness. Even traditional celebrities are now, in recent years, joining social media platforms to engage with fans in a parasocial way - to show that celebrities are just like us! They eat food, shit it out, and have bad hair in the morning! We have all found out how profitable it is to be human - but not too human - that now, even the Gods have come down to earth to cash in.

Even if consumers are aware of these dynamics in their media consumption, they will still often choose to engage positively in this system. 54% of young Americans would even become an influencer themselves if given the chance, because of how it is advertised and idealized. The parasocial relationship has created a simulation of what a person should be, due to the lack of affordances for actual human connection whilst simulating a version of human connection that is advertised as better than a real human connection - but I will argue that in reality, digital social penetration, or maybe even the illusion of it, fails to satisfy real social needs, but instead of this dilemma spurring people to seek out in-person connections, the instant and effortless gratification of a digital parasocial relationship makes users simply seek out a surplus of it.

My image, or at least the image I carefully project, has been seen by millions. Millions now have a specific perception of me - two-dimensional and dictated by an altered fraction of my legitimate self, locked in time. But what is the legitimate self? The digital age has created a larger gray area in the concept of “self” and “individual”, widening the hole that capitalism has created, where one is not only a product, but a walking advertisement. We now express and define the self through sousveillance, and often do not know ourselves without it. The self has come to be defined as the density and reaction of digital perception. Sometimes people no longer know who they are after their popularity leaves them. Late stage capitalism, bass-boosted by new technologies, has made individuals to be solely defined by reaction - because reaction is what creates transaction, what creates currency, whether it be a fix of mental gratification or actual money. I cannot think of anyone who would possibly like to admit it, but there is certainly a present attitude of “if you don’t exist online, do you even exist? Why wouldn’t you want to be online?” Why wouldn’t you want to partake in this addictive algorithm, endless scrolling, information overload, stimulation overload, and the promise of attention? You are weird if you don’t.

With the value of personal information going up, and the value of privacy going down, with people believing that they are so insignificant that their information does not matter - I will refrain from using that as a main talking point. The promotion and investment into the advancement of social technologies almost feels like state-funded propaganda, but I also will not get into that talking point in fears of sounding like a crazed conspiracy theorist. The main issue is how it has shifted our entire social attitude, and has deeply affected the social dynamics of communities and circles in real life. Human connection is strained by image and obsession. It is strained from a disembodiment of the self and the environment. We now have to control our social lives online (transcending location and social boundary) as well as our social lives in real life. Because of how personal one’s social page seems, and how unintimidating and easy it is to contact anyone, there is no secrecy left. And some of the world’s greatest stories revolve around the beauty of secrecy.

This conjecture is not just to say that everybody should return to analog, and that the digital age has not had its glorious moments - but social media tries to convince you that the main purpose of your patronage to their platform is connection, fun, and inspiration, while the purpose is really all capital. And because we, the 21st century, have become test subjects for these new, cruel, untested technologies, there was truly no restriction or boundary on who was deemed able to access essentially this panopticon of positive/negative reinforcement, and content from every dark crevice of the world. This promotion of self exploitation has wedged its way into being a priority for many. Friends become friends and lovers become lovers based on aesthetics, image, and attraction. The curation of a profile is just as important as the curation of the real self. The curation of a profile becomes the self. The line between who one is online and in real life is becoming more and more blurred; people try to mold themselves to act in the way they are able to online. Online, one is free to lust and lie and hate and obsess and love. Online, one can be confident, sexy, loud, carefully vulnerable, relentlessly controversial, smart, beautiful, mysterious, careless, carefree, detached, ethereal and unreal. But maybe humans were not meant to be all of those things, all at once.

Author’s note: If you read to the end of this, thank you, and if you’d like access to the bibliography please PM me! I would have liked to make this longer - there’s so many things I could have gone on and on about. I’d also love to hear any comments or questions or general feedback.

#social networks#social media#philosophy#sousveillance#surveillance#instagram#tiktok#digital literacy#media literacy#theory#social media addiction#attention economy#parasocial relationships#panopticon#influencers#cyber literacy#sociology#anthropology

32 notes

·

View notes

Text

SÉANCE #11 - "Sousveillance citoyenne : un combat contre le capitalisme de surveillance"

Aujourd'hui, nous vivons dans une ère du capitalisme de surveillance. Cela signifie que nous sommes sous le regard omniprésent des algorithmes des GAFAM qui suivent nos moindres actions sur le web. Cependant, dans ce panoptique numérique, nous allons présenter une contre-culture qui ne cesse de prendre de l'ampleur : la sousveillance citoyenne.

« Si vous voulez une image de l'avenir, imaginez une botte piétinant un visage humain, pour toujours. La morale à tirer de cette situation dangereuse cauchemardesque est simple : ne laissez pas cela se produire. Tout dépend de vous. ». Voici une citation de l'écrivain George Orwell, numéro de son chef-d'œuvre, 1984. Ce cri d'alerte datant de 1949 décrit parfaitement notre rapport actuel avec le numérique. Cette botte peut être affiliée aux gouvernements qui surveillent les populations par le biais du numérique ou aux grandes entreprises américaines de la technologie qui exploitent nos présences numériques pour accroître leurs profits. Les géants du numérique comme Google, Meta, ou Microsoft capitalisent sur nos existences numériques, façonnant nos réalités, nos habitudes, et nos interactions sociales selon leurs intérêts commerciaux.

La sousveillance citoyenne est la résistance à cette "botte". Selon Camille Alloing, la sousveillance "désigne alors les capacités données à chaque citoyen de faire usage des dispositifs numériques pour "regarder d'en bas" les différentes formes de pouvoirs étatiques ou commerciaux." Ce mouvement permet l'avènement de héros modernes tels qu'Edward Snowden ou Frances Haugen. Ces lanceurs d'alerte défient ainsi la surveillance numérique des États et des grandes entreprises technologiques, éveillant également le grand public sur les méthodes de surveillance numérique de masse.

Dorénavant, les citoyens s'adonnent à la sousveillance numérique, par exemple en utilisant les médias sociaux pour dénoncer les dérapages de la police. Cependant, ce mouvement citoyen n'est pas exempt de critiques. On peut donc s'inquiéter de la création d'une culture de la méfiance généralisée. Ainsi, établir un équilibre entre la protection de la vie privée et la responsabilité sociétale devient un objectif incontournable.

En fin de compte, on peut constater que la sousveillance citoyenne s'élève comme un véritable contrepoids face à l'avènement du capitalisme de surveillance. Ce mouvement citoyen doit permettre de redonner du pouvoir en tant qu'individus dans un monde hyperconnecté. La sousveillance offre un authentique espoir de liberté, une volonté de reprendre le contrôle de nos récits numériques.

Sources :

https://www.cairn.info/revue-hermes-la-revue-2016-3-page-68.htm

0 notes

Note

i know this is quite an open-ended question, so apologies in advance, but as a marxist-leninist what are your main issues with post-modernism/post-structuralism as a school of thought? from libs to anarchists, lots of (so-called) progressives/leftists seem to really enjoy it, but its reception is a far less positive among communists/marxists from what i gather. what are your thoughts on it, and on the work of people like foucault, deleuze, guattari, or even more recent ones like judith butler etc? once again sorry if this is too open-ended, but i really value your insight on politics and philosophy etc etc.

well, to be clear i do think there are some good critiques which have come out of the post-modernist camps, and consequently i would consider myself more of a neo-modernist than a classical modernist, as i do think mdernism as a concept needs to be updated in response to post-modernist critiques.

at it's best, post-modernism offers genuinely useful critiques of the limits of our ability to know things, genuine good points about the inherently fuzzy and indefinable boundaries of any system of categories that human beings could ever create.

at it's worst, post-modernism rejects the very notion that there's a material world that we can understand, and rejects the very notion of categories as a whole. once it crosses the boundary into this sort of solipsism is utterly useless to me.

ultimately once post-modernism crosses the boundary into this sort of solipsism- which it often does- it becomes completely incompatible with marxism, which is fundamentally based on the notion that there is a material world and we can learn things about it. no, we can never know things with 100% certainty, but we can know with better than 0% certainty

i really love deleuze and guattari's Capitalism and Schizophrenia, but ultimately i think it's more of a piece of poetry than a piece of real scientific theory. and i do believe, fundamentally, that the approach to analyzing capitalism must be a scientific one.

i'm not very fond of foucault at all, because frankly i'm a bit of a panopticon apologist. these sorts of "panopticons" are just part of living in a group with other people, and while i certainly think there are points to be made about how these sort of systems of sousveilance need to be regulated in order for them to not be excessive and harmful, but ultimately these sorts of regulations on those systems are themselves enforced by social systems of sousveilance. so for example, the idea of taking pictures of people in public and posting them online, i agree that there should be social conventions discouraging that behavior- but inevitably these social conventions are enforced through similar "panopticon" style social systems- that when someone sees someone posting a creepshot online, the observers collectively disincentivize that behavior, tell them "dude don't take pictures of random people in public and post them online to talk shit about them you dick" etc. anyways, that's why i don't think the foucaultian persective on "panopticons" is particularly useful though i agree that obviously those social systems exist.

172 notes

·

View notes

Text

This public essay turns onto the different visual technologies, as well the different visualities, that Rico Nasty uses to create a sense of proximity, all the while withdrawing her/self from the viewer. In doing so, Rico Nasty creates new avenues of visual sousveillance to be reproduced by Black female artists at large. Those screenshots are all culled from different visuals and exemplify the core meaning of the essay. Since this is a public essay, you can tip by sending something to my Ppl ([email protected]) or to my K0fi.

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

Bra Cam wearable interactive art installation (sousveillance art) that reverses the ‘male gaze’ of surveillance by resituating a pair of surveillance cameras as two wearable wireless webcams. | 2001

#installation#conceptual#feminism#technology#contemporary art#black and white#monochrome#surveillance#00s#art#u

375 notes

·

View notes

Text

apologies, this is feminism posting and its not good.

so I think a lot of beef that I developed with "online feminist movement" came from friction produced by a common two-step that I saw online of, if you're a reasonable person, you should be a feminist, and if you're a feminist, you should do certain things, each of which were reasonable independently, except that I didn't like the inherent exhortations to do shit, partially because I'm lazy, partially because it wasn't always clear that what was put forward would even have been a summum actum, qua feminism as the interlocutor experiences. now, this is just growing up in an ideologically contested region, but in general, I don't like the "you should do X if you're a good person" especially when the contrapositive, "I do not see you doing X, are you not a good person?" is a threat alive and well, and I find the sousveillance this triggers to be divisive to communities, rather than inclusory.

#anyways this is part of my 'why rats beef with feminism from the inside'#there's a much broader theme of rationalist allergy to socjus generally not just feminism#which makes way more sense to me from a vibes perspective. and i think is less damning in that context

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Week 4: Digital Community & Fandom –Single’s Inferno

Reality TV transcends mere entertainment; it shapes cultural dialogues, reinforces societal norms, and fosters digital communities. Single’s Inferno, a South Korean dating reality show, exemplifies this phenomenon by merging traditional romantic ideals with contemporary social media engagement. Viewers engage beyond passive consumption, participating in digital publics that debate gender roles, beauty standards, and the authenticity of online personas.

Single’s Inferno serves as a compelling case study at the intersection of reality TV and digital discourse. Unlike Western dating shows that often emphasize sensationalism, this global sensation of a dating show adopts a more subdued, aesthetically curated approach, reflecting South Korean beauty ideals and reserved courtship rituals. This carefully crafted narrative doesn't exist in a vacuum; audiences dissect and challenge it in real-time via platforms like Twitter, Reddit, and TikTok.

The public sphere theory by Habermas (1962) posits that open discussion fosters social change. In the digital era, this has evolved into multiple digital publics (Kruse et al., 2018). Hashtags such as #SinglesInferno and #SongJia create micro-publics where fans engage in meaningful discussions about gender norms, racial preferences in dating, and media portrayals of desirability.

Social media as a public sphere: The interactive nature of these platforms allows users to challenge and redefine societal norms (Deller, 2019), as seen in the discussions surrounding the show.

=> Audiences utilize social media to critique the show's representation of beauty standards and relationship dynamics, exemplifying the role of social media in contemporary public discourse.

Impact on viewers' perceptions: The influence of Single’s Inferno extends beyond entertainment, affecting viewers' perceptions of love and relationships. A study focusing on Chinese college students revealed that exposure to the show led to shifts in their concepts of love and dating practices (He, 2024). This underscores the show's role in shaping cultural norms and personal beliefs about relationships among young audiences.

Audience sousveillance: The rise of social media has transformed audience engagement with reality TV (Deller, 2019). Viewers are no longer passive consumers; they actively participate in discussions, critique content, and influence narratives through platforms like Twitter and Reddit. This phenomenon, termed "sousveillance" by L’Hoiry (2019) involves audiences monitoring and responding to media content, thereby challenging traditional power dynamics between producers and consumers.

Reality TV’s Influence on digital culture:

Reality TV like Single’s Inferno creates shared cultural moments that bridge local and global media consumption.

Platforms such as TikTok and Reddit serve as arenas for critical discussions on authenticity, desirability, and social stratification.

The emergence of fandom-driven identity politics. Discussions surrounding Single’s Inferno reflect broader societal concerns about gender norms, race, and class in contemporary dating cultures.

Conclusion: Single’s Inferno exemplifies reality TV's capacity to transcend entertainment, acting as a digital forum where audiences negotiate societal norms. The show not only entertains but also prompts viewers to examine ingrained biases about beauty, romance, and desirability.

References

Deller, R. A. (2019). Reality television : the television phenomenon that changed the world. Emerald Publishing.

He, W. (2024). The Impact of South Korean Love Variety Show on the Love Concept of Chinese College Students: A Case Study of “Single’s Inferno.” Interdisciplinary Humanities and Communication Studies, 1(7). https://doi.org/10.61173/hbvn8q34

Jurgen Habermas. (1962). The Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere.

Kruse, L. M., Norris, D. R., & Flinchum, J. R. (2018). Social Media as a Public Sphere? Politics on Social Media. The Sociological Quarterly, 59(1), 62–84. https://doi.org/10.1080/00380253.2017.1383143

L’Hoiry, X. (2019). Love Island, Social Media, and Sousveillance: New Pathways of Challenging Realism in Reality TV. Frontiers in Sociology, 4(59), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.3389/fsoc.2019.00059

0 notes

Text

Reality TV and Social Media: A New Era of Audience Engagement

In the digital age, reality TV and social media have become inseparable partners, creating a dynamic ecosystem that keeps viewers engaged long after the credits roll. This symbiotic relationship has transformed how we consume and interact with our favorite shows, blurring the lines between audience and participant.

The Social Media Revolution

Social media platforms have revolutionized audience engagement in reality TV. Shows like "Love Island" and "RuPaul's Drag Race" have mastered the art of multi-platform storytelling, extending their narratives beyond the television screen (Deller, 2019). Viewers can now follow contestants on Instagram, participate in Twitter polls, and even influence show outcomes through social media voting.

GIF by LoveIslandUSA

Creating Digital Publics

Reality TV has become a catalyst for creating "digital publics" - online spaces where viewers can discuss important social issues sparked by the shows. Research has shown that reality TV forums often become venues for debates on topics like gender roles, sexuality, and societal norms (Graham & Hajru, 2011). For instance, discussions around "Married At First Sight" often delve into deeper conversations about modern relationships and marriage expectations.

GIF by Lifetime

The Power of Fan Communities

Fan communities have emerged as powerful forces in the reality TV landscape. These groups not only support their favorite contestants but also engage in what Mann et al. (2003) call "sousveillance" - a form of bottom-up surveillance where fans hold producers accountable for perceived wrongdoings or manipulations on the show (L'Hoiry, 2019). This shift in power dynamics has forced producers to be more transparent and responsive to audience concerns.

GIF by NBA

Monetizing Engagement

The integration of social media has opened up new avenues for monetization. Reality TV stars can now leverage their newfound fame to become social media influencers, promoting products and building personal brands long after their shows have ended. This has created a new economy where social media followings can be just as valuable as screen time. As Arcy (2018) notes, television networks now incentivize stars to generate their own digital content, placing them in competition with co-stars for attention, status, and salary.

GIF by FOX TV

Parasocial Relationships and Celebrity Endorsement

The convergence of reality TV and social media has also led to the development of stronger parasocial relationships between viewers and contestants. Chung and Cho (2014) found that reality TV viewing and social media interactions with media characters were positively associated with parasocial relationships, which in turn influenced the effectiveness of celebrity endorsements.

Image by BBC Science Focus

The Future of Reality TV

As technology continues to evolve, we can expect even more innovative ways for reality TV to engage with audiences. Virtual reality experiences, interactive live streams, and AI-driven personalized content are just a few possibilities on the horizon.

In conclusion, the marriage of reality TV and social media has created a new paradigm in entertainment. It's not just about watching anymore; it's about participating, discussing, and shaping the narrative. As viewers, we've become co-creators in this digital storytelling revolution, blurring the lines between reality and entertainment in ways we never thought possible.

References: Arcy, J. (2018). The digital money shot: Twitter wars, The Real Housewives, and transmedia storytelling. Celebrity Studies, 9(4), 487–502. https://doi.org/10.1080/19392397.2018.1508951

Chung, S., & Cho, H. (2014). Parasocial relationship via reality TV and social media: Its implications for celebrity endorsement. Proceedings of the ACM International Conference on Interactive Experiences for TV and Online Video, 47-54. https://doi.org/10.1145/2602299.2602306

Deller, R. A. (2019). Reality television in the age of social media. In Reality Television: The TV Phenomenon That Changed the World. Emerald Publishing Limited.

Graham, T., & Hajru, A. (2011). Reality TV as a trigger of everyday political talk in the net-based public sphere. European Journal of Communication, 26(1), 18-32. https://doi.org/10.1177/0267323110394858

L'Hoiry, X. (2019). Love Island, social media, and sousveillance: New pathways of challenging realism in reality TV. Frontiers in Sociology, 4, 59. https://doi.org/10.3389/fsoc.2019.00059

Mann, S., Nolan, J., & Wellman, B. (2003). Sousveillance: Inventing and using wearable computing devices for data collection in surveillance environments. Surveillance & Society, 1(3), 331-355. https://doi.org/10.24908/ss.v1i3.3344

0 notes

Text

(W4) Reality TV: The Greatest Lie We Love to Believe

Reality TV always has drama, romance, and chaos, but how much of it is actually real? Behind viral moments and shocking edits, contestants carefully craft their personal brands, and producers manipulate storylines. This post unpacks the illusion of authenticity, how audiences are catching on, and what happens to reality stars once the cameras stop rolling.

The Evolution of Reality TV: From Raw Footage to Scripted Drama

Reality TV wasn’t always the glossy, drama-filled spectacle it is today. It began as an attempt to capture real life, placing ordinary people in extraordinary situations. Shows like "The Real World" (1992) and "Survivor" (2000) promised unscripted interactions and genuine emotions. However, as the genre evolved, so did the need for higher stakes, bigger personalities, and a whole lot of editing magic.

What started as an experimental glimpse into reality became a carefully manufactured form of entertainment. The rise of social strategy-based competition shows, celebrity-driven documents, and talent competitions introduced a new kind of reality—one designed to hook audiences through calculated narratives. TV shows like "Big Brother" and "Survivor" play on human psychology and alliances, while series such as "The Real Housewives" lean into drama-enhanced storytelling. Even talent shows like "The X Factor" and "RuPaul’s Drag Race" shape contestant arcs, ensuring viewers remain invested in the highs and lows of each journey.

“Reality TV’s primary goal is not to reflect reality but to create compelling, cost-effective entertainment” (Deery 2015).

Constructing ‘Realness’: The "Love Island" Illusion

While these shows market themselves as an unfiltered look into people's lives, their realism is carefully curated. Contestants don’t just participate, they perform, often exaggerating their personalities to fit predefined roles. Lovelock (2019) describes this as "compulsory authenticity", a pressure to appear real while crafting an idealized, marketable version of oneself.

A prime example is "Love Island", a dating show that presents itself as an organic matchmaking experiment but is heavily influenced by producer intervention. The #Kissgate scandal in 2019 revealed that contestants were asked to re-film a kiss to heighten drama (L’Hoiry 2019). Editing also plays a major role in shaping perceptions, as seen in "The Real World: San Francisco" (1994), where Pedro Zamora’s HIV+ identity was framed as a tragic storyline rather than showcasing his activism. Even "The Bachelor" franchise has been criticized for nudging contestants into specific character arcs to amplify emotional stakes (Ouvrein et al. 2021). Viewers are increasingly aware of these manipulations. Surveys show that 72% of "Love Island" fans believe producers shape storylines (L’Hoiry 2019), while 85% of reality TV participants admit to playing up their personas for the cameras (Ouvrein et al. 2019).

Audience Surveillance: Exposing the Illusions

Social media has transformed reality TV from a passive viewing experience into an interactive process where audiences actively investigate content. Through "sousveillance", a form of bottom-up surveillance, viewers analyze editing tricks, expose inconsistencies, and challenge producers’ decisions (L’Hoiry 2019).

Backlash against "Love Island’s" manipulated moments resulted in over 1,500 Ofcom complaints, demonstrating how audiences now hold reality TV accountable. Similarly, Survivor faced controversy when its first all-Black alliance in 2021 sparked online debate, with 54% of related tweets expressing negative sentiment (Harbin 2023).

With 6.3 million tweets posted about "Love Island’s" 2018 season alone (L’Hoiry 2019), it’s clear that fans aren’t just watching, they’re fact-checking. A study by Deller (2019) found that 65% of viewers use Twitter to verify reality TV’s authenticity. However, this hyper-awareness is a double-edged sword. While it forces networks to be more transparent, it also fuels toxic discourse, subjecting contestants to relentless public scrutiny.

Stars After Reality Shows: The Cost of Fame

For many reality stars, appearing on TV is just the beginning. Some successfully transition into long-term careers, leveraging their exposure into brand deals, business ventures, and influencer status.

Molly-Mae Hague, a Love Island 2019 contestant, built a £5M empire as Creative Director of PrettyLittleThing by capitalizing on her perceived authenticity (Deller 2019). Maura Higgins, from the same season, established herself as a television personality and brand ambassador for major companies like Ann Summers and Boots (Ouvrein et al. 2019). As Deller (2019) notes, reality TV’s “attributed celebrities” often pivot into "microcelebrity status", monetizing their public image through influencer marketing.

Yet, for every success story, there are many who struggle under the pressures of post-show life. The sudden shift from obscurity to mass attention can take a psychological toll. Tragically, contestants like Sophie Gradon and Mike Thalassitis from Love Island died by suicide after facing intense online harassment (Ouvrein et al. 2019).

Final Reflections: Can Reality TV Ever Be Truly Real?

In general, reality TV is a paradox, it markets itself as unscripted and authentic, yet every aspect is meticulously crafted for entertainment. From casting choices to post-production edits, the narratives we see on screen are designed to elicit emotion, not necessarily to reveal truth.

Despite growing awareness of these manipulations, reality TV remains wildly popular. Perhaps audiences don’t actually crave authenticity but rather the illusion of it. After all, reality TV doesn’t just reflect reality, it also reflects the conflicts, aspirations, and fantasies we want to see, just with better lighting and a dramatic soundtrack.

References:

Reference list

Deery, J. (2015) Reality TV. Cambridge: Polity.

Deller, RA 2019, Reality Television : The TV Phenomenon That Changed the World, Emerald Publishing Limited, Bingley. Available from: ProQuest Ebook Central. [15 February 2025].

Harbin, M. B. (2023) ‘Don’t Make My Entertainment Political! Social Media Responses to Narratives of Racial Duty on Competitive Reality Television Series’, Political Communication, 40(4), pp. 464–483. doi: 10.1080/10584609.2023.2195365.

L’Hoiry, X 2019, ‘Love Island, Social Media, and Sousveillance: New Pathways of Challenging Realism in Reality TV’, Frontiers in Sociology, vol. 4, no. 59, pp. 1–13.

Lovelock, M 2019, Reality TV and Queer Identities, Springer International Publishing, Cham.

Ouvrein, G. et al. (2019) ‘Bashed at first sight: the experiences and coping strategies of reality-TV stars confronted with celebrity bashing’, Celebrity Studies, 12(3), pp. 389–406. doi: 10.1080/19392397.2019.1637269.

0 notes

Text

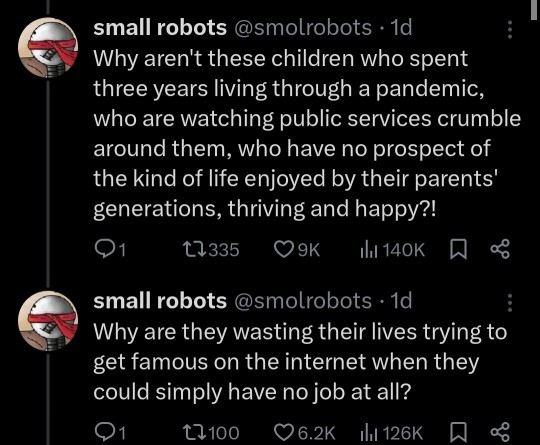

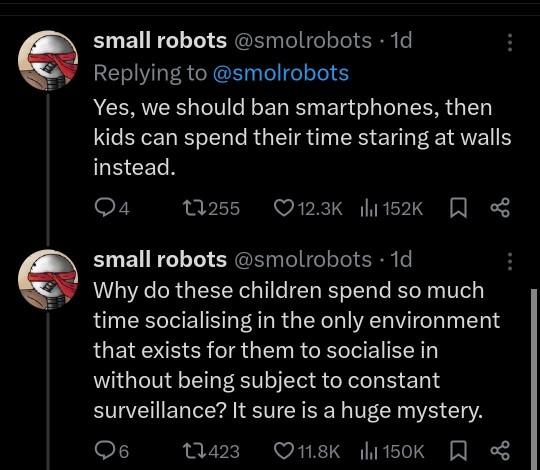

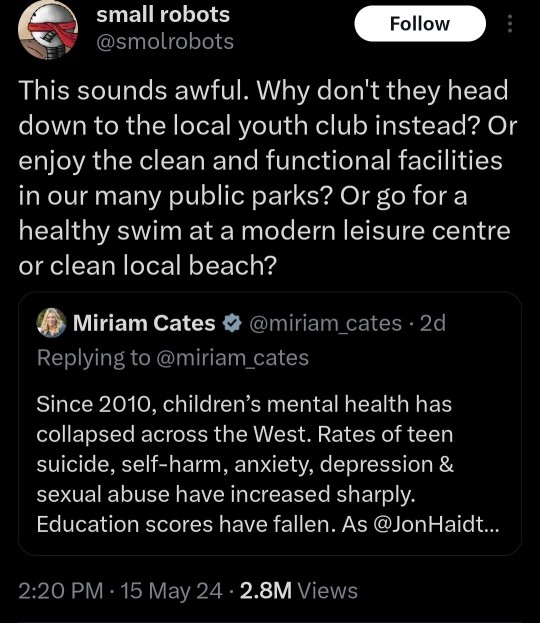

We need more third spaces.

The interweb is pretty well surveilled - by petty commercial interests, a little bit by concerned or nosy parents, hardly at all by the govt (even in red states).

What the kids need is third spaces, safe places to make the same sort of mistakes I made as a kid, less judgment (more, "yep - hurts don't it" humorous empathy), and the ability to sousveil.

Sousveillance - the ability to look back at everyone watching us.

96K notes

·

View notes

Text

The Evolution of Reality TV with Love Island: 势均力敌的我们 - Live And Love

Why do Reality shows attract viewers?

Reality TV has long been a great way to attract a vacuum audience because of the authenticity and variety of actions, interactions, and psychology that the participants bring to the fantasy.(L’Hoiry 2019) Especially with love shows, they always have high viewership and follow-up from people across the country. Shows like these keep us coming back, week after week. We want to know who said what to whom, who betrayed many others, or who agreed to fight their feelings or made decisions that affected others. All of them show the best and worst of human behavior. (Smyth 2022) It is extremely difficult to create a reality show where people can find their love within a certain period of time. That is the point that attracts people's curiosity about the content of each show.

Love Show is a very popular reality show that has attracted viewers in recent years, many countries in the world have tried to develop it. and the name of the reality show on the title is also one of many shows that have been produced. "Live and Love" has had a high number of views as soon as it was broadcast and is a topic that is searched a lot on hot search. Participants are often people working in the social sector, celebrities,… Therefore, before and after the show, they are known and discussed a lot, recognition also increases when viewers are interested in how their relationship on the show will continue in real life.

Social media influence also extends to public involvement, as seen by Live and Love, which provides a forum for conversations on societal topics including relationships, mental health, and standards of beauty.

Using their platforms, contestants have brought important issues to the public's attention by bringing their personal experiences into larger social dialogues (Kumari & Frank 2023). Reality TV shows are truly a new revolution, bringing the gap between viewers and celebrities closer in a more realistic way.

Reference list

Kumari, S & Frank, R 2023, ‘Impacts OF Media on Society: A Sociological Perspective’, IJCRT, vol. 11, no. 1, pp. 2320–2882, viewed 12 October 2024, <https://www.ijcrt.org/papers/IJCRT2301282.pdf>.

L’Hoiry, X 2019, ‘Love Island, Social Media, and Sousveillance: New Pathways of Challenging Realism in Reality TV’, Frontiers in Sociology, vol. 4, no. 59, pp. 1–13, viewed <https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fsoc.2019.00059/full>

Smyth, T 2022, ‘How Reality Shows Affect Our Lives and Society | Psychology Today’, www.psychologytoday.com, viewed <https://www.psychologytoday.com/intl/blog/living-finesse/202204/how-reality-shows-affect-our-lives-and-society>.

0 notes

Note

Its very strange to me to call yourself a panopticon apologist immediately after rbing a post about how lolcows are bad. These are the same thing. The panopticon isn't just living among other people who can also see you, it is surveilance and terror by a party with power over you that is predisposed to hostility.

i mean ultimately it comes back to what i said here:

so for example, the idea of taking pictures of people in public and posting them online, i agree that there should be social conventions discouraging that behavior- but inevitably these social conventions are enforced through similar "panopticon" style social systems- that when someone sees someone posting a creepshot online, the observers collectively disincentivize that behavior, tell them "dude don't take pictures of random people in public and post them online to talk shit about them you dick" etc.

similar principles apply with lolcow forums as with taking creepshots and posting them to mock people, both of which are malignant panopticonic systems which have significant parallels and overlaps.

similarly, if you want to stop people from engaging in lolcow forums style bullying, you have to:

A: observe them engaging in this behavior, and then B exert power over them, in order to C: disincentivize their behavior. perhaps even terrorize them a little, if necessary to stop the bullying behavior.

i don't know where you're getting "predisposed to hostility" as a necessary component for it to qualify as a panopticonic system- searching "foucault 'predisposed to hostility'" brings up very few results, which leads me to believe you invented that out of whole cloth to play no true scotsman games- but even if we assume this were true, certainly in order to stifle that sort of lolcow forum style bullying you would certainly need to be predisposed to hostility towards that sort of bullying behavior and the people who engage in it.

ultimately, the only way to stop a bad guy with a panopticon is a good guy with a panopticon, and what we see from people who subscribe to the oversimplified foucaultian "panopticon bad" framework is that ultimately they still engage in panopticonic behaviors but go "oh well it's not a panopticon when WE do it." as apas-95 pointed out on a post i reblogged and yet somehow can't seem to track down (sorry)( @apas-95 please help if you can) the whole anti-callout trend recently on tumblr was being pushed by people who were presenting themselves as anti-callout while, at the exact same time, making callout posts, sometimes even making posts like "guys block this person, they make callouts"- that's a callout! like it's the same social mechanisms, even if you argue that it's being applied in a more beneficial way it's still operating on the same kind of panopticonic social mechanisms.

(also a big part of the whole concept of the panopticon is that the prisoners also surveil, or more accurately sousveil, each other, so the part you said about "a party with power over you" isn't really necessarily inherent to the panopticon concept either)

55 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

Dark sousveillance, then, plots imaginaries that are oppositional and that are hopeful for another way of being.

from Dark Matters: On The Surveillance of Blackness by Simone Browne

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Week 5 Digital Community and Fandom: Reality TV Case Study

Admit it or not, reality television is a genre that you either love or detest. It has existed for close to thirty years in Australia. Since the early 1990s and 2000s, the majority of reality TV programmes have remained popular and are currently in production. The Block, Dancing With the Stars, Big Brother, and Survivor are a few examples. Why, therefore, does no one want to acknowledge that they like watching reality TV, given that the shows have been around for decades and have continuously high ratings?

66% of Australians admit to watching reality TV, especially dating shows, according to new AMPD Research research, yet 34% of those people lie about it. People who took part in the study admitted lying because they were embarrassed to say so. These Aussies are pretty comical in their contradictions about lying to each other. Imagine a bunch of coworkers who pretend to be friends and pretend that they haven't watched the newest season of "trash TV," but in fact, they are all sneaking home to watch Married at First Sight together. Reality television has been extending beyond television to other platforms since social media was introduced ten years ago.

Reality TV consumption and distribution have been greatly influenced by social media. Social media engagement is becoming the main focus of producers' marketing strategies as they use it to engage audiences. This method was called a "feedback loop whereby television and social media content feedback onto each other in a cycle" by L'Hoiry. The audience is being pushed to interact on several channels by this. In addition to developing memes about the programme that encourage fans to share, producers are posting "first looks" and "exclusive behindhe-scscenes content" on social media.

Reality television is generating new markets and greater viewer involvement by fostering multi-platform engagement through social media. Despite the widespread stigma associated with admitting to watching reality TV, the growing consumption across platforms is increasing viewer engagement, whether or not the public admits to it.

References

AMPD Research 2019, Australia: SVOD Study, pp. 3-16.

Graham, T & Hajru, A 2011, “Reality TV as a trigger of everyday political talk in the net-based public sphere”, European Journal of Communication, vol. 26, no. 1, pp. 18-32.

L'Hoiry, X 2019, “Love Island, Social Media, and Sousveillance: New Pathways of Challenging Realism in Reality TV”, Frontiers in Sociology, vol. 4.

0 notes

Text

Week 4: About Reality Television

Definition of Reality TV

Reality television, or reality TV for short, is like the ultimate guilty pleasure of the entertainment world. It's those programmes where actual people are cast in imaginary roles and the drama is shown to us. Big Brother, The Bachelor, or Survivor. We are obsessed with this type of television because it blurs the distinction between planned narrative and uncontrollable chaos in real life. (Helen Wood, 2022)

How Reality TV and Social Media Work Together

Imagine if your favourite reality TV show and social media as two best friends who team up to throw the party. That's what makes the entertainment world of today so magical. Reality TV and social media are like the perfect match made in pop culture heaven. Television programmes such as Big Brother and Love Island have realised that their purpose is not only to amuse viewers, but also to build communities. Social media platforms like Twitter, Instagram, and Facebook are the virtual hangouts where fans gather to gossip, debate, and obsess over their favourite contestants. It's like having a front-row seat to the drama and being able to voice your opinions from the comfort of your own couch. (Deller, 2019; Helen Wood, 2022)

Love Island as Case Study

Let's examine Love Island in more detail. For fans of reality TV, it's the ultimate guilty pleasure. The show's producers have mastered the art of keeping fans hooked both on and off the screen. They've developed an entire ecosystem where fans can dive deeper into the drama with the help of interactive polls, the official app for the show, and exclusive online content. Love Island isn't just a TV show; it's a marketing machine disguised as entertainment. From sponsored content to enabling in-app purchases, Love Island masters the art of transforming audience engagement into tangible profits. (L’Hoiry, 2019)

The Future of Reality Television

So, what does the future hold for reality television? Well, if Love Island is any indication, it's only going to get more intertwined with social media. We're talking about virtual reality experiences, personalized content, and maybe even AI-powered contestants. But seriously, reality TV will advance along with technology. The lines between fiction and reality will blur even further, and who knows, maybe one day we'll all be living in our own personal Truman Show. But until then, let's sit back, grab some popcorn, and enjoy the show. (Deller, 2019)

References

Deller, R. A. (2019). Reality Television in an Age of Social Media.

Helen Wood. (2022). Big Brother is coming back – the reality TV landscape today will demand a more caring show. https://theconversation.com/big-brother-is-coming-back-the-reality-tv-landscape-today-will-demand-a-more-caring-show-188313

L’Hoiry, X. (2019). Love Island, Social Media, and Sousveillance: New Pathways of Challenging Realism in Reality TV. Frontiers in Sociology, 4, 469244. https://doi.org/10.3389/FSOC.2019.00059/BIBTEX

0 notes