Text

(W10) Words Hurt: The Unseen Scars of Cyberbullying

Cyberbullying isn’t just an online annoyance, it’s a modern epidemic. Unlike playground taunts that stay behind at school, cyberbullying follows people everywhere, everytime. Anonymity and mob behavior turn what might have been a passing insult into relentless psychological warfare. So, let’s dive deep: What fuels this toxic behavior, and why does it hit so hard?

The Nature and Impact of Cyberbullying

Cyberbullying is a derivative form of traditional bullying that has evolved with the advent of the internet. It is marked by anonymity, widespread presence, and a mob mentality (Wong-Lo & Bullock, 2011). Unlike traditional bullying, cyberbullying can occur at any time and place, making it a relentless threat to victims. The psychological impact of cyberbullying is profound and multifaceted. Victims often suffer from attention deficit, social anxiety, depression, loneliness, interpersonal tension, and even suicidal thoughts (Kumar & Goldstein, 2020).

What makes it worse is that it doesn’t stop when you leave school or work-it’s always there, waiting in your notifications.

The kicker? Many cyberbullies aren’t inherently cruel people. The internet creates this bizarre detachment where they don’t fully grasp the impact of their words. Add in the power of groupthink, and suddenly, one mean comment snowballs into an all-out attack.

Celebrity Worship and Cyberbullying

Stan culture: a force of passion, dedication, and sometimes... straight-up aggression. A study on Chinese college students found that celebrity worship is linked to cyberbullying, especially for those with high reactive anger or childhood experiences of maternal rejection (Zhang et al., 2025). If that sounds dramatic, think about it: When people tie their self-worth to an idol, any criticism of that celeb feels like a personal attack. The result? They lash out, sometimes viciously.

Social identity theory explains this mess: People define themselves by their group affiliations, and stan culture is no exception. When an idol is "threatened," fans, especially those already prone to anger, go into attack mode, defending their fave as if their own reputation is on the line. It’s loyalty gone wrong.

But it’s not just fans attacking critics—celebrities themselves often bear the brunt of extreme online harassment. The tragic cases of South Korean idols like Kim Jong-hyun (SHINee), Sulli, and Goo Hara serve as heartbreaking reminders of how relentless cyberbullying can be. Jong-hyun, a beloved artist, struggled with depression and ultimately took his own life in 2017, leaving behind a devastating note detailing his pain. Sulli, known for her outspoken personality, faced constant online abuse for defying traditional gender norms, while Goo Hara endured relentless harassment following a publicized legal battle with an abusive ex-partner. Both died by suicide in 2019, highlighting the immense psychological toll of cyberbullying in the entertainment industry.

These cases underscore how cyberbullying extends far beyond petty internet drama, it can destroy lives. The pressure on public figures, combined with toxic online environments, creates a dangerous mix where mental health struggles are often overlooked until it's too late.

Online Harassment and Its Normalization

"It’s just the internet, don’t take it so seriously."

Is it sound familiar? That mindset is part of the problem. Research at a UK university debunked the myth that Gen Z is the "snowflake generation" by exposing how widespread and normalized online harassment actually is (Haslop et al., 2021). Women and transgender individuals bear the brunt of it, often limiting their online engagement to avoid being targeted.

When harassment becomes part of the "internet experience", people start accepting it instead of fighting it. And that’s terrifying. The more we brush off online abuse, the harder it is to push for change.

Online Sexual Harassment and Gendered Dimensions

Online sexual harassment (OSH) is a specific form of cyberbullying with a clear gendered dimension, disproportionately affecting women. OSH encompasses various forms of abuse, including negative comments, revenge pornography, and threats. It is used to shame, silence, and discipline women in online spaces, hindering their online participation (Megarry, 2014).

Why does this happen? Because the internet, much like society, has power imbalances. OSH is a digital extension of misogyny, reinforcing outdated beliefs that women should "stay in their place." Traditional legal systems often fail to provide proper protection, leaving many women to resort to naming and shaming their harassers as a last line of defense. While this form of resistance is empowering, it’s also a sign that systemic change is long overdue.

Networked Harassment and the Manosphere

If you’ve ever seen an online dogpile on a feminist creator, chances are, it was coordinated. Online harassment targeting women, particularly feminists, is often coordinated within online communities like the "manosphere." This networked harassment involves organized tactics like doxing and social shaming. The concept of "misandry" is used by these groups to falsely frame feminism as hateful towards men and to legitimize harassment (Marwick & Caplan, 2018). The manosphere, a loose network of blogs, forums, and social media groups, serves as a breeding ground for misogynistic ideologies and coordinated attacks on women.

This isn’t just individual trolls acting out, it’s an organized system. By painting feminists as villains, these communities create an echo chamber where harassment feels not only justified but necessary.

Case Study: Anita Sarkeesian and Cyber Mob Behavior

youtube

Let's look at Anita Sarkeesian for a real example! As a feminist media critic, she became the target of a massive online hate campaign for her YouTube series Feminist Frequency, which analyzed how women are portrayed in video games. What followed was next-level cyber mob behavior: threats of violence, sexual assault, and even death, alongside coordinated efforts to get her deplatformed (Sarkeesian, 2018).

Here’s the chilling part: Many of the perpetrators didn’t see this as harassment. To them, it was a game. They created an informal reward system, celebrating each successful attempt to silence her. This wasn’t "just trolling", it was systemic digital abuse designed to reinforce sexism and push women out of online spaces.

Sarkeesian argues that terms like cyberbullying don't adequately describe the scale of this "cyber mob" behavior, which functions to reinforce a culture of sexism, marginalizing women and making online environments toxic. Despite the horrific harassment, Sarkeesian's fundraiser for the Tropes vs. Women in Video Games project was overwhelmingly successful, demonstrating public outrage at such abuse and support for her work.

Final Thoughts: Scars That Never Fade

Cyberbullying isn’t just a "teen drama" or an "unavoidable part of the internet." It’s a serious issue with devastating psychological consequences. Understanding why people engage in cyberbullying, whether through anonymity, stan culture, or organized harassment, is crucial for tackling it.

For the solution, there are several of legal actions, social accountability, and cultural change. We need better online protections, but we also need to dismantle the toxic online norms that allow harassment to thrive. Creating a safer internet starts with holding people accountable, since words hurt, and their unseen scars last far longer than a viral comment ever will.

References

eugene debs. (2018, November 23). Anita Sarkeesian at TEDxWomen 2012. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-wKBdMu6dD4

Haslop, C., O’Rourke, F., & Southern, R. (2021). #NoSnowflakes: The toleration of harassment and an emergent gender-related digital divide, in a UK student online culture. Convergence: The International Journal of Research into New Media Technologies, 27(5), 1418–1438. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354856521989270

Kumar, V. L., & Goldstein, M. A. (2020). Cyberbullying and adolescents. Current Pediatrics Reports, 8(3). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40124-020-00217-6

Marwick, A. E., & Caplan, R. (2018). Drinking male tears: language, the manosphere, and networked harassment. Feminist Media Studies, 18(4), 543–559. https://doi.org/10.1080/14680777.2018.1450568

Megarry, J. (2014). Online incivility or sexual harassment? Conceptualising women’s experiences in the digital age. Women’s Studies International Forum, 47(1), 46–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wsif.2014.07.012

Wong-Lo, M., & Bullock, L. M. (2011). Digital Aggression: Cyberworld Meets School Bullies. Preventing School Failure: Alternative Education for Children and Youth, 55(2), 64–70. https://doi.org/10.1080/1045988x.2011.539429

Zhang, L., Li, Y., & Song, X. (2025). Interpreting cyberbullying within fan culture: The relationship between celebrity worship and cyberbullying. Social Behavior and Personality an International Journal, 53(2), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.2224/sbp.13895

1 note

·

View note

Text

(W9) The Power of Social Gaming: Why We Love Playing Together?

Gaming has always been more than just pressing buttons and scoring points, it’s also about connection. Whether we’re teaming up in multiplayer matches, chatting in Discord servers, or watching our favorite streamers, gaming has evolved into a deeply social experience. But why do we love playing together so much? Let’s break it down in this post.

The Innate Sociality of Gaming

At its core, gaming has always been a shared experience. Even single-player games spark discussions, fan theories, and communal engagement through streaming and social media. While some games are built for multiplayer interaction, even those designed for solo play can foster a sense of connection through shared interests and community engagement (Meriläinen, 2023).

Gaming as a Tool for Connection

One of the biggest draws of social gaming is its ability to bring people together, no matter where they are. Online multiplayer games allow friends separated by distance to stay in touch, creating a digital hangout space. As one gamer in Meriläinen’s (2023) study put it, "CS:GO has been extremely important for me ever since I ran into the game. It’s been a tool to stay in contact with friends who live in other cities." Social gaming isn’t just about fun, it’s also a way to maintain relationships that might otherwise fade.

Shared Experiences, Even When Playing Solo

Social gaming doesn’t always mean playing together in real time. The awareness that others are playing the same game can create a shared experience. Research by Tyni, Sotamaa, and Toivonen (2011) found that even when players don’t interact directly, the knowledge that others are engaged in the same virtual world fosters a sense of belonging. This explains why single-player games with large communities, such as The Legend of Zelda or Elden Ring, still feel like shared adventures.

Community as a Driving Force

For many players, the community aspect is just as important as the game itself. In Ingress, an augmented reality game, players often describe their local factions as a second family. They highlight that "the social part of it, the meeting up with other people, and having fun with other people" is the primary reason they play (Hjorth et al., 2021). From MMORPG guilds to esports teams, gaming creates spaces where friendships thrive.

Gaming in Everyday Life: The Concept of Ambient Play

Social gaming doesn’t stop when we log off. Mobile games have blurred the line between digital and real-world interactions, a phenomenon known as ambient play (Hjorth et al., 2021). Games like Pokémon GO and Minecraft seamlessly integrate into daily routines, turning commutes, lunch breaks, and social gatherings into gaming opportunities.

Minecraft as a Social Playground: The game’s versatility—playable "everywhere, on almost every device"—makes it a prime example of ambient play (Hjorth et al., 2021). Whether players are building together in real-time or watching Let’s Plays, Minecraft fosters social interaction in multiple ways.

Neurodiversity & Inclusion: Minecraft has also been a valuable tool for neurodiverse players, offering alternative ways to communicate and engage socially.

Education & Collaboration: Schools have embraced Minecraft as a learning tool, allowing students to collaborate on creative projects while having fun.

Live Streaming: Public Entertainment and Networked Broadcast

The rise of game live streaming has amplified the social dimension of gaming by transforming private play into public entertainment and creating new forms of networked interaction.

Real-time interaction: Live streaming platforms like Twitch offer broadcasters the opportunity to interact with their audiences in real-time through synchronous chat windows. This integration of audience interaction into the broadcast fosters a strong sense of co-presence and community. As Taylor (2018) observed, “Audiences— and their interactions with broadcasters— were themselves becoming integrated into the show. Game live streaming has become a new form of networked broadcast” (Taylor, 2018).

Watching together: The feeling of "watching alone but instead alongside thousands of others in real time" can be a powerful draw of live streaming, creating a shared viewing experience and a sense of belonging.

Building audiences: Live streaming allows players of all kinds, not just esports professionals, to build audiences interested in observing, commenting, and playing alongside them, further highlighting the desire for social engagement in gaming.

Asynchronous Sociality in Casual Games

Even in games where players don't interact simultaneously, social elements play a crucial role in engagement and enjoyment. Social network games (SNGs) exemplify this asynchronous sociality.

Sociality without direct commitment: The asynchronous design of SNGs allows players to engage with their social networks in a "low-stake, leisurely and informal way" without requiring direct, simultaneous engagement. This enables players to “feel connected without the obligation of direct, purposive interaction” (Consalvo, 2015).

Dead-time as social opportunity: Periods of "dead-time" in SNGs, such as waiting for resources to grow or for friends to send items, can become opportunities for social interaction. Players might contact each other to ask about the game, fostering connections even when not actively playing.

Family bonding through play: Asynchronous social network gameplay can be particularly valuable for maintaining connections with geographically dispersed family members. Activities like visiting each other's game spaces or sending gifts can signal that they are thinking of one another without needing direct interaction. As Boudreau and Consalvo's research found, family members playing SNGs together often felt a sense of closeness without feeling obligated to more active forms of sociality (Boudreau & Consalvo, 2015).

Reciprocal relationships: Helping others in SNGs, even if it doesn't directly benefit one's own gameplay, can build "social capital," leading to others reciprocating with help and creating a "virtuous cycle" of social networked gameplay.

Motivations Beyond Gameplay

The reasons for engaging in social gaming extend beyond the core mechanics of the games themselves.

Social motivations in locative play: In location-based mobile games like Ingress, players often cite the social aspect as the "driving force" behind their motivation to continue playing. Meeting teammates and the sense of community are highly valued (Hjorth et al., 2021).

Affective connection: Social games can foster affective responses and create "new subjectivities of consumption". Positive feedback mechanisms in games can encourage players to return and engage socially (Molyneux et al., 2015).

Avoiding asociality: Even players who prefer single-player games often participate in online communities, attend events, or discuss games with friends, highlighting the inherent social pull within gaming culture. As the research by Meriläinen (2023) found, “None of the responses suggested that the respondent’s gaming was completely asocial. Even those who preferred single-player games, or for whom gaming was very private, still participated in online communities related to their favorite games, visited events, or discussed games with their friends” (Meriläinen, 2023).

Final Thoughts: More Than Just a Game

In essence, the power of social gaming stems from our fundamental human desire for connection, shared experiences, and community. Whether through real-time interaction in live streams, asynchronous exchanges in casual games, or the bonds formed within gaming communities around shared interests, playing together offers a multitude of social and emotional rewards.

References

Boudreau, K., Consalvo, M., Leaver, T., & Willson, M. (2015). The sociality of asynchronous gameplay: Social network games, dead-time and family bonding. In Social, Casual and Mobile Games (pp. 77–88). Bloomsbury Publishing Plc. https://doi.org/10.5040/9781501310591.ch-006

Hjorth, L., Richardson, I., Davies, H., & Balmford, W. (2021). Exploring Play. Exploring Minecraft, 27–47. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-59908-9_2

Meriläinen, M., & Ruotsalainen, M. (2023). The light, the dark, and everything else: making sense of young people’s digital gaming. Frontiers in Psychology, 14, 1164992–1164992. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1164992

Molyneux, L., Vasudevan, K., & Gil de Zúñiga, H. (2015). Gaming Social Capital: Exploring Civic Value in Multiplayer Video Games: Gaming, Social Capital, & Civic Participation. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 20(4), 381–399. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcc4.12123

Taylor, T. L. (2018). Broadcasting Ourselves. In Watch Me Play (pp. 1–22). Princeton University Press. https://doi.org/10.23943/9780691184975-002

Tyni, H., Sotamaa, O., & Toivonen, S. (2011). Howdy pardner: on free-to-play, sociability and rhythm design in FrontierVille. Proceedings of the 15th International Academic MindTrek Conference: Envisioning Future Media Environments, 22–29. https://doi.org/10.1145/2181037.2181042

0 notes

Text

(W8) You Are Enough: Embracing Authenticity in a Filtered World

Augmented reality (AR) filters have become a ubiquitous part of our online interactions in these days. From Snapchat to Instagram, these filters offer a quick and easy way to enhance our appearance, add fun effects, or even transform our faces into fantastical creatures. However, while these filters can be entertaining, they also raise important questions about self-perception, identity, and mental well-being. This post explores the impact of AR filters on our self-image and emphasizes the importance of embracing our authentic selves. Remember, you are enough - no filters needed.

The Filter Glow-Up: What's the Hype?

AR filters provide a unique form of digital adornment, akin to traditional makeup or fashion accessories (Baker, 2020). They allow us to experiment with our appearance, express creativity, and engage with others in playful ways. Coy-Dibley (2016) highlights how filters can help us experiment with different aspects of our appearance, such as trying on new hairstyles or makeup looks. This experimentation can be a form of self-expression and identity exploration. However, the widespread use of these filters also reflects deeper societal pressures and beauty standards. As Rettberg (2014) notes, cultural filters teach us to mimic photo models and Instagram stars, shaping our visual self-representation to align with societal ideals.

But… How Does This Mess With Our Heads?

Here's where it gets a bit serious. All those perfectly filtered faces can actually change how we see ourselves. There's even a term for it: "digitized dysmorphia," where playing with digital images distorts how we view our own bodies (Coy-Dibley, 2016). And it's not just one group of people – these unrealistic beauty standards from filters can make anyone feel insecure (Baker, 2020). While some might enjoy using filters and connecting with others, it can also lead to feeling less happy with our natural selves when we're chasing an impossible ideal (Javornik et al., 2022). The duality of digital alteration presents both opportunities for creative expression and risks for mental health. It's a bit of a double-edged sword!

Could Filters Be Training Us For… What!?

Think about it – someone creates these filters, setting the boundaries for how we can tweak our appearance online. This can create a bit of an imbalance, where the filter creators have more power over our self-expression than we do ourselves (Fisher, 2020). Therefore, Rettberg (2014) also raises concerns about biometric observation, suggesting that the use of filters could prepare us for biometric surveillance. As we become accustomed to altering our digital appearances, we may also become more accepting of technologies that monitor and analyze our biometric data. This normalization could inadvertently pave the way for increased surveillance and reduced privacy in our daily lives.

Finding the Awesome in Being Authentically YOU

Despite all the filter fun, it's so important to remember that your unfiltered self is genuinely enough! The pressure to live up to these digital beauty standards can be intense, but embracing who you truly are can lead to way more self-love and good vibes (Javornik et al., 2022). Using filters to explore or transform can be cool, but when it becomes about chasing an unrealistic ideal, it can affect how we feel about ourselves (Javornik et al., 2022).

Final Thoughts: Let Your Real Self Shine!

So, while those AR filters can be a bit of fun and a way to play around with our digital identity (Kuntsman, 2017), let's not forget the beauty and value of our real, unfiltered selves. Remember, technology offers us ways to express ourselves, but it also shapes how we can do that (Rettberg, 2014). Embracing our authentic selves can lead to more genuine connections and a healthier relationship with our online presence.

References

Barker, J. (2020). Making-up on mobile: The pretty filters and ugly implications of snapchat. Fashion, Style & Popular Culture, 7(2), 207–221. https://doi.org/10.1386/fspc_00015_1

Coy-Dibley, I. (2016). “Digitized Dysmorphia” of the female body: the re/disfigurement of the image. Palgrave Communications, 2(1), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1057/palcomms.2016.40

Fisher, T. (2020). The smooth life: Instagram as a platform of control. Virtual Creativity, 10(1), 93–103. https://doi.org/10.1386/vcr_00022_7

Javornik, A., Marder, B., Barhorst, J. B., McLean, G., Rogers, Y., Marshall, P., & Warlop, L. (2022). “What lies behind the filter?” Uncovering the motivations for using augmented reality (AR) face filters on social media and their effect on well-being. Computers in Human Behavior, 128(107126), 107126. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2021.107126

Kuntsman, A. (Ed.). (2017). Selfie Citizenship. Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-45270-8

Rettberg, J. W. (2014). Seeing Ourselves Through Technology : How We Use Selfies, Blogs and Wearable Devices to See and Shape Ourselves (1st ed. 2014.). Palgrave Macmillan UK. https://doi.org/10.1057/9781137476661

0 notes

Text

(W7) The Digital Mirror: How Social Media Shapes Beauty Standards and Body Image in Asia

The rise of social media has not only transformed communication but also revolutionized how we perceive beauty and body image. In Asia, where cultural traditions intertwine with modern technology, platforms like Facebook, Instagram and TikTok are reshaping beauty ideals, which are often lead to negative impact on our mental health. This post delves into the complex impact of social media on body image, explores cultural influences, and considers the growing trend of cosmetic surgery, especially in Asia.

The Influence of Social Media on Body Image

Social media platforms have become a ubiquitous part of daily life, especially for young people. They serve as digital mirrors that frequently reflect an idealized, and sometimes distorted, image of beauty. For example, research by Fardouly et al. (2015) demonstrates that exposure to images of thin models is associated with lower body satisfaction and increased body shame among women. This effect is amplified in many Asian countries, where prevailing beauty ideals emphasize slimness and refined facial features (Samizadeh, 2022). Such idealized portrayals not only skew perceptions of normalcy but also contribute to a cycle of negative self-evaluation.

Moreover, influencers have emerged as powerful arbiters of beauty on social media. Studies by Tiggemann and Slater (2014) indicate that young women who follow beauty influencers are more prone to engaging in appearance-related comparisons. The highly curated lifestyles and edited images presented by these influencers often promote a narrow definition of bMental Health Implicationseauty, pressuring followers to conform to these unrealistic standards. This trend highlights a critical intersection between personal identity and digital media culture.

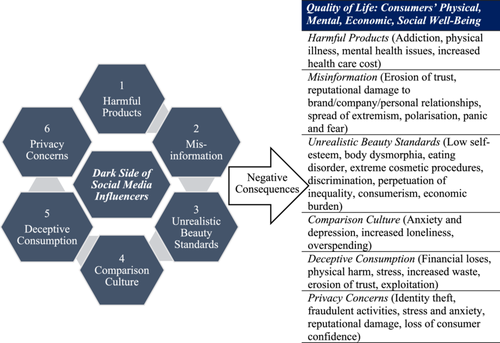

The Dark Side of Social Media Influencers

While influencers often promote beauty and lifestyle content, their impact is not entirely positive. The image below illustrates some key risks, such as the promotion of unrealistic beauty standards, the spread of misinformation, and the pressure to conform to curated lifestyles. These factors can contribute to negative self-esteem and mental health challenges among users.

Algorithmic Visibility and Its Impact

The algorithms that govern social media platforms significantly influence which content is seen and celebrated, often privileging certain aesthetics over others. Duffy (2022) discusses how social media algorithms determine content visibility, often favoring creators who conform to mainstream beauty standards. This can marginalize diverse voices and body types, leading to a lack of representation for those who challenge conventional ideals. The result is a digital landscape where only specific beauty standards are amplified, reinforcing harmful stereotypes.

Cultural Context and Evolving Beauty Standards in Asia

Beauty standards in Asia are deeply rooted in history and tradition. Traditional ideals, such as fair skin and delicate features, continue to influence modern perceptions of attractiveness (Samizadeh, 2022). The popularity of K-pop has only strengthened these ideals, with many fans aspiring to emulate the flawless appearances of their favorite idols. Moreover, these beauty standards are increasingly linked to social and professional success—a notion captured by the adage, “your face is your rice bowl,” which underscores the high stakes of appearance in many Asian cultures.

The Cosmetic Surgery Boom

The pressure to achieve these idealized images has spurred a dramatic rise in cosmetic surgery across Asia. South Korea, for instance, is renowned for its high rate of cosmetic procedures, with double eyelid surgery and jaw contouring among the most common interventions. A report by the International Society of Aesthetic Plastic Surgery (ISAPS, 2023) confirms that South Korea ranks among the top countries for cosmetic surgery per capita. As societal pressures intensify, cosmetic enhancements have become normalized as a strategy for attaining the desired look (Barone et al., 2024).

Mental Health Implications

The relentless pursuit of perfection in the digital age has significant mental health repercussions. Yin et al. (2025) found that emerging adult women in China experience heightened body image concerns, exacerbated by internalized weight bias and deficits in emotional intelligence. Constant comparisons with idealized online images can lead to anxiety, depression, and even body dysmorphic disorders. Additionally, the quest for social validation, manifested through likes and comments, which further entrenches negative self-perceptions, as individuals become overly reliant on external approval to gauge their worth (Perloff, 2014).

Promoting Positive Body Image

While social media often reinforces unrealistic standards, it also holds the potential to foster authenticity and resilience. Initiatives that encourage users to share unfiltered images and personal narratives, such as the “As She Is” challenge, demonstrate how digital platforms can promote a more inclusive vision of beauty (TEDx Talks, 2019). Educational programs that enhance media literacy and raise awareness about the impact of idealized imagery can empower young people to critically assess the content they consume and embrace diverse representations of beauty.

youtube

Final Thoughts: Embracing Authentic Beauty

The intricate interplay between social media, cultural beauty standards, and mental health poses both challenges and opportunities in contemporary Asian society. By critically examining these dynamics and advocating for authenticity, we can work toward a future where beauty is defined by individuality rather than conformity. Embracing a more inclusive and realistic standard of beauty is essential, it's not only for promoting mental well-being but also for nurturing a culture that celebrates diverse forms of self-expression.

References

Barone, M., De Bernardis, R., & Persichetti, P. (2024). Artificial Intelligence in Plastic Surgery: Analysis of Applications, Perspectives, and Psychological Impact. Aesthetic Plastic Surgery. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00266-024-03988-1

Duffy, B. E., & Meisner, C. (2022). Platform Governance at the margins: Social Media Creators’ Experiences with Algorithmic (in)visibility. Media, Culture & Society, 45(2), 016344372211119. https://doi.org/10.1177/01634437221111923

Ekinci, Y., Dam, S., & Buckle, G. (2025). The Dark Side of Social Media Influencers: A Research Agenda for Analysing Deceptive Practices and Regulatory Challenges. Psychology and Marketing, 42(4). https://doi.org/10.1002/mar.22173

Fardouly, J., Diedrichs, P. C., Vartanian, L. R., & Halliwell, E. (2015). Social Comparisons on Social media: the Impact of Facebook on Young women’s Body Image Concerns and Mood. Body Image, 13(1), 38–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2014.12.002

ISAPS. (2023). Global Survey 2023: Full Report and Press Releases. Isaps.org. https://www.isaps.org/discover/about-isaps/global-statistics/global-survey-2023-full-report-and-press-releases/

Samizadeh, S. (2022). Beauty Standards in Asia. Non-Surgical Rejuvenation of Asian Faces, 21–32. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-84099-0_2

TEDx Talks. (2019). Our Body Image and Social Media: Live Life Unfiltered | Keisha & Teagan Simpson Simpson | TEDxOttawa [YouTube Video]. In YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iWc5rQ_YvYw

Tiggemann, M., & Slater, A. (2013). NetGirls: The Internet, Facebook, and Body Image Concern in Adolescent Girls. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 46(6), 630–633. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.22141

Yin, L., Jing, L., He, Q., & Wang, H. (2025). Physical activity, emotional intelligence, weight bias internalization, and body image concerns among emerging adult women in China. Social Behavior & Personality: An International Journal, 53(2), 1–10.

0 notes

Text

(W6) The Rise of Slow Fashion: A Sustainable Shift in Consumer Habits

If you open your wardrobe right now…How many clothes are from Shein, Zara, or H&M? Now, ask yourself: How often do you actually wear them?

Fast fashion has dominated our lives for decades, filling closets with trendy, cheap clothing that rarely lasts. But things are changing, more people are waking up to the harsh realities of fast fashion—its environmental destruction, labor exploitation, and toxic cycle of overconsumption. Slow fashion is becoming a mainstream lifestyle choice.

Let’s break down why fast fashion is fading and how slow fashion is taking its place—with facts, not just opinions.

What is Slow Fashion? A Fundamental Shift in Consumption

Slow fashion is not just about buying fewer clothes, it’s about buying “smarter”. According to Pookulangara and Shephard (2013), slow fashion is "an approach to fashion that considers the processes and resources required to make clothing, particularly focusing on sustainability and ethical practices" (p. 201). Unlike fast fashion, which thrives on constant trends, overproduction, and low costs, slow fashion focuses on:

Quality over quantity – Clothes that last, not just trendy throwaways.

Ethical production – Fair wages and safe conditions for garment workers.

Sustainability – Reducing waste, pollution, and carbon footprint.

Timeless design – Classic, versatile pieces instead of trend-chasing.

How Slow Fashion is Gaining Momentum

The slow fashion movement is gaining significant traction, driven by several key factors that highlight a shift in consumer behavior and industry practices.

First key is consumer behavior is shifting towards more sustainable choices. A 2024 PwC survey found that over 50% of global consumers are now actively trying to reduce their fashion consumption. This indicates a growing awareness and concern about the environmental and social impacts of their purchasing decisions (PwC, 2024).

The thriving eco-conscious brands in the market also become a key factor. Ethical labels like Patagonia, Everlane, and Stella McCartney are gaining loyal customers, demonstrating that sustainability can be profitable. These brands have built their reputation on transparency, ethical production, and high-quality products, which resonate with consumers looking for alternatives to fast fashion (Aggarwala et al., 2024).

Moreover, regulations are tightening around the fashion industry. Governments are increasingly implementing policies to address the environmental impact of textile waste. For example, the European Union is introducing regulations that hold brands accountable for their waste, encouraging more sustainable practices within the industry (European Commission, 2022).

Why Are People Quitting Fast Fashion?

The shift away from fast fashion is driven by several compelling reasons, each highlighting the significant negative impacts of this industry on the environment, society, and individual consumers.

The Environmental Disaster of Fast Fashion

The fashion industry is one of the most resource-intensive industries in the world. According to the video "If you think fast fashion is bad, check out SHEIN" on YouTube, the textile sector is responsible for about 8%-10% of global carbon emissions, surpassing international flights and shipping emissions combined (DW Planet A, 2021). The industry's fast production cycle leads to overproduction and significant environmental degradation.

youtube

Textile Waste: The video highlights that 85% of all textiles go to the dump each year, which amounts to 100 million tons of textile waste. This waste is largely due to the disposable nature of fast fashion, where garments are designed to be worn only a few times before being discarded.

Water Usage: The production of fast fashion garments is extremely water-intensive. For example, it takes about 2,700 liters of water to produce one cotton T-shirt, which is enough for one person to drink for 2.5 years.

Chemical Pollution: The dyeing and treatment of textiles contribute to water pollution. The video mentions that the fashion industry is responsible for 20% of global wastewater, which often contains harmful chemicals that can contaminate water supplies.

Consumers are becoming increasingly aware of these environmental issues. According to a 2024 PwC survey, more than 50% of consumers globally are trying to reduce their clothing purchases to be more sustainable (PwC, 2024).

2. The Labor Exploitation Behind Fast Fashion

The TikTok video titled "Let's make my wage theft waffles featuring Victoria’s Secret," Venetia La Manna addresses labor exploitation within the fashion industry, focusing on Victoria's Secret. Through her "wage theft waffles" metaphor, La Manna emphasizes the need for consumers to be aware of unethical practices and encourages support for brands that ensure fair wages and ethical treatment of workers (La Manna, 2022).

The real cost of fast fashion isn’t just environmental—it’s human. Fast fashion brands often rely on low-wage labor in developing countries like Bangladesh, India, and Vietnam, where:

Exploitation of Workers: 85% of garment workers are women, often paid below living wages and working in unsafe conditions (Domingos et al., 2022). These workers face long hours, poor working conditions, and little to no job security.

Tragic Accidents: Unsafe working conditions have led to tragedies like the Rana Plaza collapse in 2013, which killed 1,134 workers. Such incidents highlight the dire need for better labor standards and safety regulations.

3. The Death of Shopping Hauls?

Not long ago, YouTube and TikTok were flooded with "Shein hauls" and "Zara unboxings." However, there is a noticeable shift in consumer behavior:

Criticism of Overconsumption: Influencers are increasingly criticizing overconsumption and promoting minimalism.

Advocacy for Secondhand Shopping: Many influencers now advocate for secondhand shopping through thrifting, Depop, and Poshmark. This shift promotes a more sustainable approach to fashion by extending the life of existing garments.

Capsule Wardrobes: Building capsule wardrobes with timeless, high-quality essentials is becoming more popular. This approach reduces the need for frequent purchases and encourages thoughtful, intentional shopping.

Final Thoughts: Fast Fashion Won’t Disappear Overnight, But We Can Change the Industry

The fast fashion era is slowing down, but we still have work to do. The more we shift our mindset from “trendy” to “timeless”, the closer we get to a sustainable future.

Let’s make our wardrobes a reflection of our values, not just our impulse buys!

References

Abelvik-Lawson, H. (2019, November 29). 9 reasons to quit fast fashion | Greenpeace UK. Greenpeace UK. https://www.greenpeace.org.uk/news/9-reasons-to-quit-fast-fashion-this-black-friday/

Aggarwal, D., Fazla Rabby, Mochammad Fahlevi, Andhyka Muttaqin, & Bansal, R. (2024). Mapping the history, trajectory, and anatomy of slow and sustainable fashion: a bibliometric analysis. Cogent Business & Management, 11(1). https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2024.2423058

Domingos, M., Vale, V. T., & Faria, S. (2022). Slow Fashion Consumer Behavior: a Literature Review. Sustainability, 14(5), 2860. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14052860

DW Planet A. (2021, December 10). If you think fast fashion is bad, check out SHEIN. Www.youtube.com. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=U4km0Cslcpg

European Commission. (2022, March 30). EU strategy for sustainable and circular textiles. European Commission. https://environment.ec.europa.eu/strategy/textiles-strategy_en

La Manna, V. (2022, March 28). ‘Let’s make my wage theft waffles featuring Victoria’s Secret’ TikTok video

Pookulangara, S., & Shephard, A. (2013). Slow Fashion Movement: Understanding Consumer Perceptions—An Exploratory Study. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 20(2), 200–206. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2012.12.002

PwC. (2024, May 15). Consumers Willing to Pay 9.7% Sustainability Premium, Even as Cost-of-Living and Inflationary Concerns Weigh: PwC 2024 Voice of the Consumer Survey. PwC; PwC. https://www.pwc.com/gx/en/news-room/press-releases/2024/pwc-2024-voice-of-consumer-survey.html

Vijeyarasa, R., & Liu, M. (2021). Fast fashion for 2030: Using the pattern of the sustainable development goals (SDGs) to cut a more gender-just fashion sector. Business and Human Rights Journal, 7(1), 45–66. https://doi.org/10.1017/bhj.2021.29

0 notes

Text

(W5) From Hashtags to Algorithms: Reimagining Citizenship in the Digital Age

In an era where social media platforms dominate our communication landscape, the concept of citizenship is evolving. Digital citizenship isn't just about our rights and responsibilities online; it's also about how these platforms shape our civic engagement and political participation. As we navigate this digital age, it's crucial to understand how hashtags and algorithms influence our views on citizenship and activism. This post explores these dynamics, focusing on the intersection of digital citizenship, platform features, and the implications for participatory democracy.

The Hashtag Era: Activism in the Digital Sphere

Hashtags have become powerful tools for mobilization and activism. For example, the #ShoutYourAbortion movement on Instagram allows individuals to share personal stories about abortion, helping to normalize a topic often surrounded by stigma. Research by Kim and Lee (2022) shows that visually appealing posts get more engagement, while text-heavy posts face more backlash, highlighting a tension between aesthetic presentation and the rawness of lived experiences. This complexity shows that while digital tools can amplify voices, they can also modify messages.

Additionally, research by Theocharis et al. (2023) highlights the unique features of platforms like Twitter and Facebook. Twitter, with its focus on rapid information sharing, supports movements like #BlackLivesMatter by enabling quick mobilization and public discourse. In contrast, Facebook's structure fosters community engagement through strong-tie networks, making it better for local organizing and support. Understanding these differences is key to grasping how various platforms shape political engagement and activism.

Algorithmic Gatekeepers: The Role of Platforms

The algorithms that run social media platforms play a big role in deciding which voices are heard and which are marginalized. Choi and Cristol (2021) argue that "digital citizenship must make critical social relations with technology visible." This visibility is especially important for marginalized groups, who often face higher risks online.

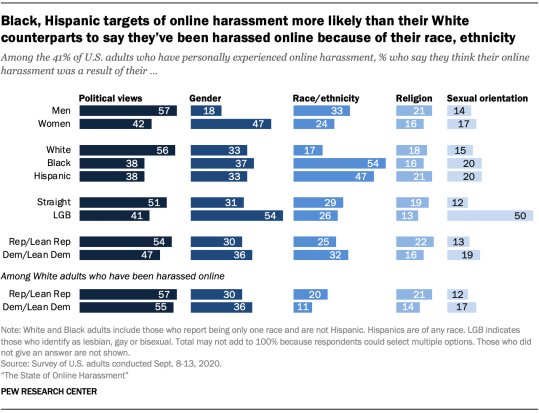

For instance, a Pew Research Center report found that 47% of women who have been harassed online believe it was because of their gender:

This highlights the need to critically examine how algorithms can perpetuate systemic inequalities.

Kim and Lee's (2022) findings further illustrate this point. Their analysis showed that posts with more embedded text received lower engagement and more negative comments, suggesting that visibility in digital spaces does not always mean safety. They conclude that "the uptake of social media in politics presents two possibilities for disrupting the traditional classification of participation," emphasizing the need for a nuanced understanding of how digital platforms operate.

Education and Digital Citizenship: Bridging the Gap

Despite the growing importance of digital citizenship, schools often lag in providing comprehensive digital literacy programs. Choi and Cristol (2021) advocate for integrating an intersectional lens into digital citizenship education, arguing that "educators must integrate digital literacy practices that recognize students’ intersectional identities." This approach empowers students to navigate online spaces more effectively and engage critically with the platforms they use.

Current educational practices often focus on basic internet safety and etiquette, neglecting the complexities of digital engagement. Theocharis et al. (2023) point out that civic education must evolve to include the realities of social media participation, which now encompasses "following NGOs on social media" and engaging in online political discourse. By fostering an understanding of how digital platforms shape civic engagement, educators can better prepare students for active participation in democracy.

Final Reflections: Reimagining Citizenship for the Digital Age

As we move further into the digital age, reimagining citizenship requires a critical engagement with the platforms that shape our interactions. The research discussed here underscores the importance of understanding how hashtags and algorithms influence political participation and civic engagement. By recognizing the distinct features of different platforms, we can better navigate the complexities of digital citizenship and advocate for a more inclusive and equitable online environment.

In conclusion, the future of digital citizenship lies in our ability to harness the power of social media for collective action while remaining vigilant about the risks posed by algorithmic biases and systemic inequalities.

*Me logging off to attend a real protest

References:

Choi, M. and Cristol, D., 2021. Digital Citizenship: A Critical Social Theory Perspective. Journal of Digital and Media Literacy, 8(2), pp.45-67. doi: 10.1080/00405841.2021.1987094.

Kim, S. and Lee, J., 2022. Hashtag Activism: The Case of #ShoutYourAbortion. Social Media Studies, 10(1), pp.23-45. doi: 10.1177/21582440221093327.

Pew Research Center, 2021. The State of Online Harassment. Available at: https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2021/01/13/the-state-of-online-harassment/.

Theocharis, Y., Barberá, P., Fazekas, Z., and Popa, S.A., 2023. Social Media and Political Participation: The Distinct Roles of Twitter and Facebook. Journal of Political Communication, 40(3), pp.123-145. doi: 10.1080/01402382.2022.2087410.

0 notes

Text

(W4) Reality TV: The Greatest Lie We Love to Believe

Reality TV always has drama, romance, and chaos, but how much of it is actually real? Behind viral moments and shocking edits, contestants carefully craft their personal brands, and producers manipulate storylines. This post unpacks the illusion of authenticity, how audiences are catching on, and what happens to reality stars once the cameras stop rolling.

The Evolution of Reality TV: From Raw Footage to Scripted Drama

Reality TV wasn’t always the glossy, drama-filled spectacle it is today. It began as an attempt to capture real life, placing ordinary people in extraordinary situations. Shows like "The Real World" (1992) and "Survivor" (2000) promised unscripted interactions and genuine emotions. However, as the genre evolved, so did the need for higher stakes, bigger personalities, and a whole lot of editing magic.

What started as an experimental glimpse into reality became a carefully manufactured form of entertainment. The rise of social strategy-based competition shows, celebrity-driven documents, and talent competitions introduced a new kind of reality—one designed to hook audiences through calculated narratives. TV shows like "Big Brother" and "Survivor" play on human psychology and alliances, while series such as "The Real Housewives" lean into drama-enhanced storytelling. Even talent shows like "The X Factor" and "RuPaul’s Drag Race" shape contestant arcs, ensuring viewers remain invested in the highs and lows of each journey.

“Reality TV’s primary goal is not to reflect reality but to create compelling, cost-effective entertainment” (Deery 2015).

Constructing ‘Realness’: The "Love Island" Illusion

While these shows market themselves as an unfiltered look into people's lives, their realism is carefully curated. Contestants don’t just participate, they perform, often exaggerating their personalities to fit predefined roles. Lovelock (2019) describes this as "compulsory authenticity", a pressure to appear real while crafting an idealized, marketable version of oneself.

A prime example is "Love Island", a dating show that presents itself as an organic matchmaking experiment but is heavily influenced by producer intervention. The #Kissgate scandal in 2019 revealed that contestants were asked to re-film a kiss to heighten drama (L’Hoiry 2019). Editing also plays a major role in shaping perceptions, as seen in "The Real World: San Francisco" (1994), where Pedro Zamora’s HIV+ identity was framed as a tragic storyline rather than showcasing his activism. Even "The Bachelor" franchise has been criticized for nudging contestants into specific character arcs to amplify emotional stakes (Ouvrein et al. 2021). Viewers are increasingly aware of these manipulations. Surveys show that 72% of "Love Island" fans believe producers shape storylines (L’Hoiry 2019), while 85% of reality TV participants admit to playing up their personas for the cameras (Ouvrein et al. 2019).

Audience Surveillance: Exposing the Illusions

Social media has transformed reality TV from a passive viewing experience into an interactive process where audiences actively investigate content. Through "sousveillance", a form of bottom-up surveillance, viewers analyze editing tricks, expose inconsistencies, and challenge producers’ decisions (L’Hoiry 2019).

Backlash against "Love Island’s" manipulated moments resulted in over 1,500 Ofcom complaints, demonstrating how audiences now hold reality TV accountable. Similarly, Survivor faced controversy when its first all-Black alliance in 2021 sparked online debate, with 54% of related tweets expressing negative sentiment (Harbin 2023).

With 6.3 million tweets posted about "Love Island’s" 2018 season alone (L’Hoiry 2019), it’s clear that fans aren’t just watching, they’re fact-checking. A study by Deller (2019) found that 65% of viewers use Twitter to verify reality TV’s authenticity. However, this hyper-awareness is a double-edged sword. While it forces networks to be more transparent, it also fuels toxic discourse, subjecting contestants to relentless public scrutiny.

Stars After Reality Shows: The Cost of Fame

For many reality stars, appearing on TV is just the beginning. Some successfully transition into long-term careers, leveraging their exposure into brand deals, business ventures, and influencer status.

Molly-Mae Hague, a Love Island 2019 contestant, built a £5M empire as Creative Director of PrettyLittleThing by capitalizing on her perceived authenticity (Deller 2019). Maura Higgins, from the same season, established herself as a television personality and brand ambassador for major companies like Ann Summers and Boots (Ouvrein et al. 2019). As Deller (2019) notes, reality TV’s “attributed celebrities” often pivot into "microcelebrity status", monetizing their public image through influencer marketing.

Yet, for every success story, there are many who struggle under the pressures of post-show life. The sudden shift from obscurity to mass attention can take a psychological toll. Tragically, contestants like Sophie Gradon and Mike Thalassitis from Love Island died by suicide after facing intense online harassment (Ouvrein et al. 2019).

Final Reflections: Can Reality TV Ever Be Truly Real?

In general, reality TV is a paradox, it markets itself as unscripted and authentic, yet every aspect is meticulously crafted for entertainment. From casting choices to post-production edits, the narratives we see on screen are designed to elicit emotion, not necessarily to reveal truth.

Despite growing awareness of these manipulations, reality TV remains wildly popular. Perhaps audiences don’t actually crave authenticity but rather the illusion of it. After all, reality TV doesn’t just reflect reality, it also reflects the conflicts, aspirations, and fantasies we want to see, just with better lighting and a dramatic soundtrack.

References:

Reference list

Deery, J. (2015) Reality TV. Cambridge: Polity.

Deller, RA 2019, Reality Television : The TV Phenomenon That Changed the World, Emerald Publishing Limited, Bingley. Available from: ProQuest Ebook Central. [15 February 2025].

Harbin, M. B. (2023) ‘Don’t Make My Entertainment Political! Social Media Responses to Narratives of Racial Duty on Competitive Reality Television Series’, Political Communication, 40(4), pp. 464–483. doi: 10.1080/10584609.2023.2195365.

L’Hoiry, X 2019, ‘Love Island, Social Media, and Sousveillance: New Pathways of Challenging Realism in Reality TV’, Frontiers in Sociology, vol. 4, no. 59, pp. 1–13.

Lovelock, M 2019, Reality TV and Queer Identities, Springer International Publishing, Cham.

Ouvrein, G. et al. (2019) ‘Bashed at first sight: the experiences and coping strategies of reality-TV stars confronted with celebrity bashing’, Celebrity Studies, 12(3), pp. 389–406. doi: 10.1080/19392397.2019.1637269.

0 notes

Text

(W3) Exploring the Public Sphere: How Tumblr Shapes Queer Masculinities and Body Positivity

As society becomes more open, people are increasingly comfortable expressing and embracing their identities on social media. Platforms like Tumblr play a vital role in creating spaces where individuals can share their experiences, challenge norms, and find a sense of belonging. This post explores how Tumblr serves as a public sphere for discussions on queer masculinities and body positivity, examining its impact on self-expression and community support.

Tumblr as a Public Sphere

The public sphere is a concept that emphasizes the importance of creating a space where individuals can come together to discuss significant issues and share ideas without outside interference. As Habermas (1991) describes, it is a realm where private individuals unite to engage in rational discourse, ultimately leading to greater knowledge and potential political change. Social media has expanded this concept, allowing marginalized communities to participate in discussions that challenge dominant narratives.

Loader and Mercea (2011) argue that digital platforms have reshaped participatory politics, enabling greater inclusivity and self-representation. Unlike mainstream platforms like Instagram or Facebook, which often prioritize polished and commercialized content, Tumblr fosters a movement of raw, unfiltered self-expression. This dynamic makes it a welcoming haven for those exploring identities that may not align with mainstream narratives, particularly in the realms of queer masculinities and body image. On Tumblr, users can share their authentic selves, connect with others, and find community in their unique experiences.

Queer Masculinities and Self-Representation on Tumblr

Tumblr plays a crucial role in shaping and showcasing diverse expressions of masculinity. In their study, Draper and McDonnell (2018) explore how gay personal style bloggers utilize Tumblr to navigate and redefine gender norms, skillfully balancing audience expectations with their authentic identities. Unlike other social media platforms like Instagram, Facebook, where hypermasculine or heteronormative aesthetics often dominate, Tumblr provides a space for users to explore softer, more fluid forms of masculinity without the fear of immediate backlash.

A key concept in this discussion is context collapse—the blending of different social spheres into one digital space. Many users curate their Tumblr identities in ways that allow them to change between traditional masculinity and queer self-expression, often presenting themselves differently depending on their audience. This dynamic reflects broader tensions in queer identity formation, where the desire for self-expression competes with external pressures to conform.

Body Positivity and the Politics of Visibility

“Hashtags such as #bodypositive are key sites of self-representation, but they also reveal persistent beauty hierarchies.” – Reif et al. (2022)

Tumblr has significantly contributed to the body positivity movement, especially through the #bodypositive hashtag. In their analysis, Reif et al. (2022) explore how women leverage this hashtag to challenge traditional beauty ideals, often sharing selfies and personal stories that promote self-acceptance. Their findings indicate that while Tumblr promotes empowerment, many users still adhere to conventional feminine beauty standards in their self-representation, highlighting the ongoing struggle between defiance and societal pressures.

The support from the community is vital to this movement. Positive interactions—such as affirming comments about diverse body types—motivate users to embrace their unique appearances. This aligns with Fuchs’ (2012) insights on the political economy of social media, which suggest that platforms influence how individuals view themselves through visual culture and the feedback they receive from their audience.

Final Thoughts: Embracing Our Unique Selves.

Tumblr has been seen as a powerful public sphere that is more than just a theoretical concept; it’s a lived experience for many marginalized users. By providing a platform for diverse self-expressions and community support, it challenges traditional norms and fosters inclusivity. As users navigate the complexities of identity in this digital space, they contribute to a richer understanding of gender and body image in contemporary society.

Engaging critically with Tumblr content and continuing to uplift voices that challenge the status quo are essential. At the end of the day, Tumblr isn’t just a website; it’s a community that helps shape digital identities, one reblog at a time.

References:

Draper, J., & McDonnell, A. M. (2018). Fashioning Multiplatform Masculinities: Gay Personal Style Bloggers’ Strategies of Gendered Self-representation across Social Media. Men and Masculinities, 21(5), 1-20.

Fuchs, C. (2012). The Political Economy of Privacy on Facebook. Television & New Media, 13(2), 139-159.

Habermas, J. (1991). The Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere: An Inquiry into a Category of Bourgeois Society. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Loader, B. D., & Mercea, D. (2011). Networking Democracy? Social Media Innovations and Participatory Politics. Information, Communication & Society, 14(6), 757-769.

Reif, A., Miller, I., & Taddicken, M. (2022). “Love the Skin You‘re In”: An Analysis of Women’s Self-Presentation and User Reactions to Selfies Using the Tumblr Hashtag #bodypositive. Mass Communication and Society. DOI: 10.1080/15205436.2022.2138442.

0 notes