#so is it this painting that céline kept in her house ?

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

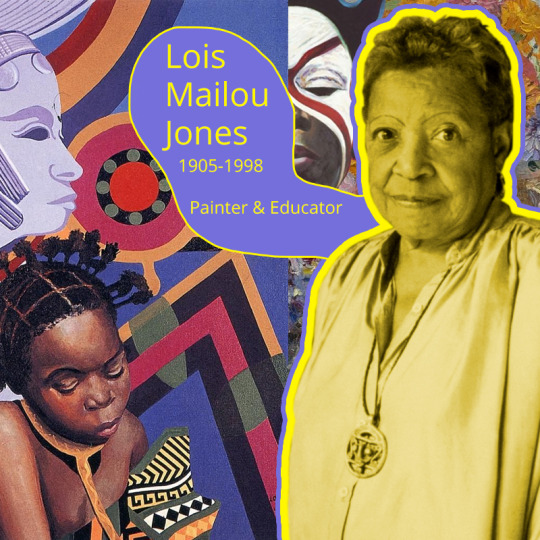

Lois Mailou Jones was born in Boston, Massachusetts. Her parents, a cosmetologist and a lawyer, encouraged her interest in art from childhood. While always a Bostonian at heart, she did do much of her growing up in Cape Cod at Martha's Vineyard where her parents bought a house. There, she would meet great influences on her life. Artist, Meta Warrick Fuller, Novelist Dorothy West, and Composer, Harry T Burleigh. And with such a pedigree as her influences, she could only be destined for great things.

She attended the High School of Practical Arts in Boston and took night classes at the Boston Museum of Fine Arts through a scholarship. Her first exhibition, was at just seventeen, in Martha's Vineyard. She was also apprenticed to costume designer Grace Ripley, and this sparkled her interest and influence by African masks.

She continued studying at the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, studying design and winning a scholarship and also took night courses at MassArt, then called the Boston Normal Art School, while working toward her degree. She graduated and went on to get her graduate degree from the Design Art School of Boston. Then later, in 1928, the shift happened. She attended Howard University, and began to focus on painting.

A life longer learner, she never stopped going to school. She took classes and earned more degrees throughout her life.

She began teaching soon after finishing college (the first one), but the director of the Boston Museum School refused to hire her because she was a black woman. In 1928 she was hired by Charlotte Hawkins Brown to teach at the newly formed art department at Palmer Memorial Institute, a black prep school in North Carolina.

If it wasn't clear already that Lois was renaissance person, while teaching at the prep school, she also taught folk dance, coached basketball, and played piano during church services. But soon she was off to Washington DC. Recruited by James Vernon Herring to join the Art Department at Howard University. She would stay there as a professor of both design and watercolor until her retirement in 1977.

Through the 1930s she sough recognition. She began to exhibit her works with the William E Harmon Foundation. The first piece, a simple charcoal drawing of a young black man, entitled Negro Youth (1929). She spent time in Harlem as the Harlem Renaissance began. By this time she had been a designer, leaned into portraiture, and now began to meld the two disciplines. A unique style began to develop that was all her own.

In 1937, Lois received a fellowship to study in Paris, France at the Académie Julian. In that year abroad she produced 40 paintings, watercolor and en plein air. Two pieces were selected for exhibition at the Salon de Printemps at the Société des Artists Fraçais. Like many black artist that traveled abroad, Lois fell in love with France where she felt more free and more accepted. She would extend her time abroad and travel to Italy, but she did return the US following. She traveled often to France, staying with her colleague and friend, Céline Marie Tabary. They no doubt influenced each other's work, but Lois was also influenced by the culture around her, and it's visible in her work from the geometry of her shapes to her use of color.

In 1941, Lois would enter a painting into the Corcoran Gallery's anuual competition. At this time in history, black Americans were not allowed to submit their own art. So, she had a colleague at Howard University, Tabary submit it for her in order to get around the rule. For her piece, Indian Shops Gay Head, Massachusetts, she won the Robert Woods Bliss Award. Though, just as she could not submit her own work, she also could not pick up her own reward. But Tarbary would do this for her as well. These difficulties did not deter Lois. She only dug her heels in and kept working.

She worked alongside and within the Négritude movement. Her work the visual for the primarily literary movement. For example, her piece, Parisian Beggar Woman was completed with text from Langston Hughs.

Back in 1934, Lois met Lois Vergniaud Pierre-Noel while she was a student in Columbia University. A prominent Haitian artist, they corresponded for nearly twenty years before marrying in the South of France in 1953. From here, her frequent trips to Haiti would great influence her work. In 1954 the Haitian government invited her to paint the people and landscapes of Haiti, and she returned to the country often as well as to France. The works she produced between the mid 50's and mid 60's are among her most prominent and well know works. As time went on, she was still extremely prolific and her style only becoming more colorful and more seamless in it's blending of Post-Impressionist, African and textile-like design. In 1990, The Meridian International Center with the help of Lois, created an exhibition that toured the US for several years. While this was not her first exhibition or her first solo exhibition, this was the first that garnered national attention. While her skill was incredible, she did not paint what was in vogue for black artists. Despite this lack of appreciation, her work is in museums all over the world. From Haiti, to the White House. Lois would die in 1998 at her home in Washington DC at the age of 92. While history has done Lois a disservice, she was so prolific that's easy to see her work today. And it truly is incredible. All her influences filtered through her into something unique and challenging. If you'd like to see her work or learn more about her life: Loïs Mailou Jones: Creating A New African-American Image

Smithsonian American Art Museum - Lois Mailou Jones Illustration History - Lois Mailou Jones Black Past - Lois Mailou Jones

Medford Arts - Lois Mailou Jones

#lois mailou jones#Loïs Mailou Jones#Black Art#Black Artist#Black History Month#Black Art History#Art History#American History

21 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Céline talks about the importance of representing the abortion within the film

(Little reminder that @bereaving is the best !!)

"Here it’s a sequence that I know is disturbing. Because we just got out of this scene (the abortion scene), just got out of this representation of an abortion and we enter another dynamic, which is to represent abortion within the film.”

“It was very important for me even if there’s a double tension. It is important to have an abortion and to represent the importance of representing it. Because this is what happened by cutting women off from the opportunity to be artists. They did not represent their private lives, they did not represent their desire, they did not represent their bodies, they did not represent their lives. And all these images are missing from history, but they are especially missing in OUR life. It’s Annie Ernaux who said that there is not a museum in the world where there is a painting called « the abortion ».”

“So this scene may happen a little abruptly but it's not to forget that art creates memory. And I also wanted to represent the pleasure of representing, the pleasure that we see on Marianne's face. And also to represent the impulse of the model, her intelligence, it’s her who said what to look at, it’s her who had the idea of painting. This was the opportunity that women had, to be in the artists' workshops/studios, it was to be models. They seized this opportunity, that's how they made artworks.”

“This is my favorite painting. It has never been completed."

Click here to see more translated parts of the DVD commentary

#so is it this painting that céline kept in her house ?#you can see Marianne's pleasure so well#noémie nailed that#portrait of a lady on fire#portrait de la jeune fille en feu#céline sciamma#celine sciamma#noémie merlant#noemie merlant#adèle haenel#adele haenel#luàna bajrami#luana bajrami#poalof commentary

3K notes

·

View notes

Photo

Love French watercolorist Céline’s, & husband Olivier’s, 500 yr. old fairy tale home in France. Came across it again, so here it is, in case you missed it (or I posted it on my old blog and forgot). Isn’t it castle- like w/the tower?

Delicate shades of green, beige, and gray create a peaceful atmosphere in the living room, which has a large working fireplace. The original wooden beams pair well with the recently installed oak flooring, custom-built by a local carpenter. Hanging from the ceiling is a lamp crafted by Céline.

"These 16th-century oak beams are very sturdy—they will last a long time," says Céline. Aren’t they gorgeous? What do you think of the pale green paint?

The original wooden chimney in the living room was damaged; it was replaced with a stone fireplace from the 17th-century.

The wooden staircase in the living room leads to the house's second floor.

They bought this old portrait in a second-hand shop in the region of Berry, where they used to live. "We have the impression that she's always looking at us," says Céline.

A black piano was repainted using some of Céline’s favorite colors. The wall behind it displays a 17th-century Dutch plate, a vintage turtle shell, a colorful 18th-century painting, and an old portrait of unknown origin.

On top of the piano are a series of mementos and curiosities: An old glass vial once used to store medicinal suction cups, Venetian masks bought during a family vacation to Italy, and a small painting of a cow by a Parisian artist.

Totally in love with that island.

Céline bought the blue-and-white tiles behind the black Lacange range over several years, collecting them until she had enough to make a backsplash. The spice rack was once part of an old cupboard.

The copper faucet is surrounded by a collection of antique cooper pots, bought at various flea markets and second-hand stores.

A shelf in the guest room, which occupies a small third-floor outhouse behind the tower, is stocked with discarded science textbooks and materials found by Olivier in a school where he was once a history teacher.

An 18th-century Dutch-style painting is the dining room's showpiece. The couple's trusted carpenter cut it to fit into the molding. On the wooden table are two antique Italian candlesticks.

An experienced picture framer, Céline collects antique frames, which she stores in the non-working fireplace in her atelier.

Céline’s atelier is covered in a moss-green wallpaper. "I kept the wooden beams here in their original dark hue, so I wanted to add something bright and fun," says the artist. The mantel holds a series of decorative objects and family pictures. Right above it, she hung two of her most personal watercolors: One depicts her horse, the other shows her daughter riding.

This small-scale theatre stage was found at a 2nd hand shop, and the "actors" are historical figures painstakingly painted by Céline on thick cut-out cardboard.

Olivier began collecting flags when he was a child; some of them are displayed on the stairwell leading to the top of the house's tower.

In the 2nd fl. master, Céline painted the walls and ceiling in pastel tones, a color scheme that is seen throughout the property. "I love colors but I don't like big contrasts," she says. "The old oak beams were very dark and looked a bit somber." The cozy bed is a family heirloom, and the mirror above it was designed by Céline using an antique frame.

Beyond the garden, the house has a second entrance that leads to a foyer.

https://www.lonny.com/Home+Tour/articles/x_zYMWbkS1U/Rustic+Tudor+Style+Home+Will+Make+Want+Move

#historic french home#patina#artist's home#antiques#old rustic home#500 yr. old house in France#long post

304 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Name: Hina Wildes Species: Human (Spellcaster) Occupation: Art Teacher at WCHS Age: 27 Years Old Played By: Amélie Face Claim: Naomi Scott

“You have to be tough. It’s not like life asks for your opinion anyway.”

Rain on the garden tiles in the summer. It was the sound that Hina hated the most.

The night she had lost her parents was far away, and she remembered very little of it. She was only 4 years old at the time, and yet she remembered it raining that night. Her cousin, Gillian, had dragged her out of the house, out of her bed, to the car. She remembered running barefoot in the grass, slipping on dirt, crying because her favorite pajamas were soaking wet. All she had left of this event was an old teddy bear she had kept with her until today, and that memory of wet cloth and slippery grass.

Memories of her family started to fade over the years. Had it not been for the stories Gillian told her, she might have forgotten it all. The faces of her parents, her older sister vanished, eventually, as well as their voices but the name of Miriam stayed : she was the woman who had destroyed everything they had, taken everything from them, and she would have to pay the price. Perhaps a slayer’s stake would meet her heart. A kind punishment considering the harm and pain she had caused.

The death of their coven became another cold case for the police, but neither Gillian nor Hina moved on. They might have had to leave town, but one day, they would return, claim their home back and build a new coven from the ashes.

Hina and her cousin found a home on the other side of the Canadian-US border, living for a while with their uncle. It was he who raised Hina for the most part, but Gillian was the one who truly instilled rage and passion in Hina, reminding her of what they had lost, of what they had, of what could have been, and telling her that their story had not come to an end yet.

The girl studied in a regular school, and would come home to study alchemy with her cousin, fueled by the idea that one day, they would be back in White Crest and repair what had been broken in the past. She paid attention to every detail, hellbent on not making the same mistakes as her elders. They had been greedy, she would be humble. They had been imprudent, she would be careful. She studied, she trained, she tried, she failed, she tried again. Alchemy was demanding, but she was willing to leave other forms of magic aside. Where was the point in being versatile if you didn’t specialize in at least one form of magic?

Hina felt the same way about the rest of her schooling. Chemistry was easier than what she learned from her aunt, art was what made her feel alive, but she had no interest in some of the subjects taught. Passing was what mattered, wasn’t it?

She juggled between her Art studies and Gillian’s lessons. Years passed. The threat of Miriam Flemming was no longer so heavy on the Wildes women’s shoulders. Hina started teaching, and Gillian left town to head back home. A few weeks passed, and the texts from her cousin stopped coming. The two had always been so close that they couldn’t spend a full day without seeing the other. Something had happened, this much Hina knew. Convinced that it had something to do with that monster that had haunted her her whole life, she packed her bags and headed to Maine.

Hina was back in town, and she would make sure that Miriam sourly regretted that she had not gotten the stake instead.

Character Facts:

Personality: Strong-willed, passionate, spiteful, confident, impatient, level-headed, defensive, energetic, aloof, intolerant, arrogant

She teaches art at WCHS but she also spends a lot of her free time working on paintings and sculpting metal.

Having grown up in Québec, she speaks French and English with that regional accent. No, she doesn’t like Céline Dion. No, she won’t impersonate Céline Dion.

While she is not one to speak 24/7 about her job, she is passionate about it and will fight you if you say art is not important.

Hina always wears clothes that hide the transmutation circle she has tattooed on her back.

She does not know much about supernatural creatures aside from what she has been told about vampires. While she is aware that there are more, she is not knowledgeable about them.

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

REVIEW: The Way Beyond Art, collection presentation Van Abbemuseum.

Saturday 2 September was my first museum day of the month: I travelled from Maastricht to Eindhoven to visit the Van Abbemuseum's new collection presentation, The Way Beyond Art. This new presentation opened on July 1st earlier this year, and thanks to a certain mother of mine celebrating her birthday I could not make it to the opening. Ironically enough, I chose my sister's birthday to visit the museum instead. (Don't worry, she has forgiven me.)

As I was sitting on the train to Eindhoven, I read an article in an art magazine I picked up earlier that coincidentally had a review of the Van Abbemuseums new collection presentations. I say presentations, because in addition to The Way Beyond Art, the first new collection presentation The Making of Modern Art had been installed earlier this year (and also reviewed by me). Well, there goes my blank first impression... The review however focused more however on The Making of Modern Art and still left loads to my imagination, so I entered the museum an hour later still not really knowing what to expect.

What I certainly did not expect, was walking straight into a painting by Anselm Kiefer hanging on top of the staircase. Speaking of this staircase; the flashy neon installation 'Hi Ha' (1992) by John Körmeling had been replaced by 'A Place Beyond Belief' (2012) by Nathan Coley, as a memory of the attacks of 9/11 in 2001. The former work kept flashing in red, orange and yellow, but this new installation clearly marks something new, something more serious.

As the introductory text reads, the exhibition is structured into three parts: Land, Home and Work. Shown here is the first room of the theme 'land'. It is evident how every single one of these artworks fit into the theme, which makes the fact that they are not accompanied by labels next to them a lot easier. Instead, several binders are put around the room, where the visitor can read the accompanying texts to the artworks. This is incredibly cleverly done: not only can the visitor decide whether he wants to actually read the texts or just view the artworks by themselves, the written texts are also a lot larger and easier to read since they don't have to fit on a small plaque next to the work. This makes things a lot easier for the visually impaired visitor. The Van Abbemuseum has always been amazing in dealing with the impaired and handicapped, but this is another big step forward. Chapeau!

Two of the coolest (if I may say so - heck it is my blog so I may say it's cool!) artworks in the room, is this combination of Füsun Onur's 'Let's Meet at the Orient' (1995, balloon) and Céline Condorelli's 'The Bottom Line (To Kathrin Böhm)' (2014, curtain). It shows the theme 'land' like no othe: Onur's installation consists of a blue balloon keeping some sort of dreamcatcher afloat, reminiscent of a hot air balloon. In this round frame, there is a lace abstract world map. In the basin below float the names of several countries across the world in a layer of water. The installation represents the earth without any borders, any conflicts, any power relations. It is an artwork that might be an early past or a distant future wherein peace is the only thing that's present.

This collection presentation is built very experimentally. Whereas the previous collection presentation of the Van Abbemuseum was pretty much in line with the idea of the white cube, there has been a full turn into the opposite direction with its dark walls, scaffolding structures on which artworks are hung and the aforementioned different way of presenting the accompanying texts of the artworks. Because it's presented in such an unconventional way, it forces the visitor to try harder to find their way around the exhibition, forcing them to look closer and therefore engaging them more with the art. This experimental way of curating is also very present in the second theme of the presentation, 'home'. As I was walking through the exhibition, I was afraid that due to a lack of signage (apart from the binders and introductory text, there are no texts in the exhibition whatsoever), I might not know when I was going to reach the second theme. But as I stumbled upon this very architectural room, I knew I was 'Home'.

Home is often associated with safety, security and a sense of belonging. It is wonderful that the curatorial theme have taken this so literally by transforming the exhibition rooms into the rooms of the house. In the broader sense, the theme refers to the private versus the public domain and the exhibited artworks refer to all the uses of the word 'home'.

The last theme of the exhibition is 'work', also a very present aspect in our everyday life. This part enables the visitor to take a more active standpoint. One of these things is the 'inspection station', where the visitor can take a closer look at an artwork that displayed on a table. A mirror is installed above it, so you can still see the painting in full. Another part that allows active participation is Dan Peterman's Civilian Defense (2007), a big installation in the middle of one of the main rooms that consists of colourful sandbags. The round shape encourages people to sit together and engage in conversation, which you are allowed to do (when you take off your shoes).

The banners shown in the image above are quotes and questions from museum visitors that stimulate dialogue and discussion. They are changed every once in a while so that there's always new things to discuss with whomever is visiting the exhibition too.

This presentation is classic Van Abbemuseum: challenging, very contemporary subject matter, an unconventional way of curating and presenting your art, all-inclusive to the impaired, stimulating audience participation but still very straightforward. This museum is one that has always been pushing the boundaries of art and museology and this recent collection presentation is no exception to that rule.

0 notes

Text

Unpacking Fashion’s Love Affair with Artists

Dusan Reljin, Marina Abramović and Crystal Renn for Vogue Ukraine, 2014, from “Legendary Artists and the Clothes They Wore,” 2019. Courtesy of Harper Collins.

Why do we care what famous artists wear? It might seem silly to look back to the Old Masters to appreciate their outfits, but 20th- and 21st-century artists have often found themselves the muses of major fashion houses—and, more recently, fodder for Pinterest inspiration boards. Artists, after all, are keenly considerate of color and form; how they dress can be a telling sign of their creative innerworkings.

“The job of artists is to critique culture, unload their psyches into their work, and make edifying masterpieces the rest of us can revere,” wrote Terry Newman, author of Legendary Artists and the Clothes They Wore (2019). “What they wear while doing these things is interesting, too.” Newman’s book dissects the fashion choices of major artists and traces how their art and personal style has been appropriated or emulated on runways and in wider visual culture.

Self-Portrait, 1980. Robert Mapplethorpe "Robert Mapplethorpe: The Perfect Medium" at Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Los Angeles

A model is seen ahead of the Raf Simons fashion show during Pitti 90, Florence, Italy, 2016. Photo by Antonello Trio via Getty Images.

Fashion houses often pay homage to famous artworks and movements—Moschino under Jeremy Scott’s direction heavily references Pop Art—but they’ve also tried to capture that ineffable je ne sais quois of the artists behind the works. Raf Simons did both in his 2017 spring menswear collection, a collaboration with the Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation. The male models wore billowing button-down shirts printed with Mapplethorpe’s black-and-white photographs. They were also styled to look like the late artist, with soft, curly hair and leather muir caps—an ode to Mapplethorpe’s personal and artistic interest in S&M. The looks bring to mind former Interview editor Bob Colacello’s recollection of the photographer when they met in 1971: “He was pretty but tough, androgynous and butch,” Colacello told Vanity Fair in 2016.

The inspiration for the autumn 2014 Céline show was more precise: the muddy, masculine boots of war photographer Lee Miller, from the famous image of her sitting defiantly in Adolf Hitler’s bathtub just hours before his death. Miller’s streamlined, “utility chic” wardrobe, as Newman called it, which she wore while on assignment for Vogue during World War II, has been referenced in fashion multiple times. But designer Phoebe Philo specifically named Miller’s boots as the starting point for the collection. “[Miller was] doing things which were quite radical at the time, like wearing men’s clothes, but which today seem quite normal,” Philo said after the show.

Lee Miller with the essentials of Life, cigarette , wine and petrol , Weimar, by David Sherman, 1945. Lee Miller °CLAIR Galerie

A model walks the runway at the Celine Autumn Winter fashion show during Paris Fashion Week, 2014. Photo by Catwalking/Getty Images.

Artists’ personal style, intentionally or not, often becomes part of their brand. Some artists channel their visual aesthetic into their looks. Jean-Michel Basquiat paired designer suit jackets with worn-in streetwear, Frida Kahlo wore traditional Mexican garb rife with symbolism, and Georgia O’Keeffe opted for minimal silhouettes with Southwestern accessories. Likewise, David Hockney is known to sport vivid, color-blocked outfits. Designer Christopher Bailey, formerly of Burberry, is a self-professed fan: “I love the way Hockney wears color,” he has said, “so that you’re never completely sure how deliberately the look is put together.”

Others resist fashion trends, a statement in itself. Today, Marina Abramović outfits herself in haute couture but as a young artist, she carefully crafted her image as “very radical, no make-up, tough, spiritual,” as she told Vogue in 2005. In the 1970s, she explained, being fashionable as an artist could be construed as overcompensating for a lack of talent.

Portrait of Pablo Picasso in a winter coat, scarf, and beret, ca. 1950s. Photo by Hulton Archive/Getty Images.

Basquiat 8, 1983. Yutaka Sakano Galerie Patrick Gutknecht

Over time, and with the repetition of a look, some artists have successfully whittled down their personal style into a single icon. Think of Rene Magritte’s bowler hat or Yayoi Kusama’s bright red bob. Although Pablo Picasso was known to wear various types of hats—“Peruvian knitted hats with pom-poms, sun-shielding straw toppers, and stiff, classy homburgs,” Newman noted—it was his beret, frequently featured in his paintings, that stuck. His status as a style influencer was made clear during two of his exhibitions at London’s Institute of Contemporary Art in the 1950s: “Employees found lost berets more than any other personal item,” Newman wrote.

Some artists have influenced contemporary fashion more directly, lending their expertise to fashion houses and retail lines. In 1983, Malcolm McClaren and Vivienne Westwood tapped Keith Haring to translate his street art into fluorescent streetwear for the runway. Kusama produced a collection for Bloomingdales in the 1980s and has more recently collaborated with Louis Vuitton and Marc Jacobs. Jeff Koons has also collaborated with Louis Vuitton, as well as H&M and Stella McCartney.

Wax figure of Japanese artist, Yayoi Kusama at the Louis Vuitton and Yayoi Kusama Collaboration Unveiling at Louis Vuitton Maison on Fifth Avenue, New York, 2012. Photo by Rob Kim/FilmMagic.

It’s after artists’ deaths, however, when their style can be merchandised to such an extent that it becomes disconnected from the reality of their lives. Constructivist Alexander Rodchenko, who once designed utilitarian-wear for a utopian Russia, would have balked at Jerry Hall modeling high-end red garments for a 1975 British Vogue editorial inspired by his graphic, Communist-flavored works. Basquiat embraced the fashion world and was loved by designers, but he faced racial bias as a black man shopping for expensive clothes. He modeled for Comme des Garçons and favored Armani and Issey Miyake, but according to his late girlfriend Kelle Inman, he was often tailed in department stores, and once was denied entry to high-end boutique until he returned with Inman. Three decades later, Basquiat’s brand is packaged into lines from Forever 21, Sephora, and Douglas Hannant.

Norman Parkinson, Jerry Hall Rodchenko, from “Legendary Artists and the Clothes They Wore,” 2019. Courtesy of Harper Collins.

The commodification of Kahlo’s style is perhaps the most glaring example. She is revered for her fashion, which is intrinsic to her art—she appeared in her many self-portraits wearing embroidered huipil blouses, Juchiteca headdresses, and full skirts; and accessorized with flowers, gemstones, and plaited hair. Kahlo’s fashion choices were tied directly to her heritage and her disability; she hid her prosthetic leg in a red leather boot adorned with two bells. Art historian Hayden Herrera said when Kahlo “put on the Tehuana costume, she was choosing a new identity, and she did it with all the fervor of a nun taking the veil.”

Kahlo’s wardrobe and accessories, representing the deepest layers of her identity, have been translated again and again: by Christian Lacroix in 2002, Gaultier in 2004, Commes de Garçons in 2012, and even Barbie in 2018. You can find her face on nearly anything: There are Frida pins, Frida T-shirts, Frida nailpolish, Frida bracelets (like the one British Prime Minister Theresa May wore in 2017, sparking endless news analysis). Kahlo’s clothing, which was kept under lock and key for nearly 60 years at her husband Diego Rivera’s request, has now been the subject of blockbuster exhibitions.

Frida Kahlo On White Bench, New York (2nd Edition), , 1939. Nickolas Muray Matthew Liu Fine Arts

A Pakistani model presents a creation by Deepak Perwani on the second day of Fashion Pakistan Week, Karachi, 2013. Photo by Asif Hassan/AFP/Getty Images.

Perhaps fashion is more cyclical than art, or simply runs on a shorter cycle, repeatedly revisiting and retranslating trends. Artists, willingly or not, are pulled into that rotation, as inspiration. In 1967, photographer Cecil Beaton traveled to O’Keeffe’s home in New Mexico to capture her for a story in Vogue. The then 79-year-old artist had spent a lifetime carefully crafting her image, wearing elegant but simple silhouettes accented with turquoise and silver accessories. In 2009, actress Charlize Theron flew to the late artist’s home with photographer Mario Testino to recreate the shoot, marking another turn in the rotation of O’Keeffe’s influence.

Two years later, Abramović made the influence of fashion on art clear when she asked Italian designer Riccardo Tisci to suckle on her breast in another shoot with Testino, this time for Visionaire. The pair, who are friends and collaborators, commented on the images for the issue. “I said to him, this is the situation: Do you admit fashion is inspired by art?” Abramović recalled. “Well, I am the art, you are the fashion, now suck my tits!” The image of the performance artist feeding Tisci like a baby may be an odd—and oddly literal—visual metaphor, but when art nurtures fashion it trickles down to the rest of us, a small piece of an artist’s oeuvre hanging in our own closets.

from Artsy News

0 notes

Link

Earlier this summer, Simon Porte Jacquemus brought his tenth-anniversary fashion show to the middle of a lavender field in Provence. He cheekily titled the collection “Le Coup de Soleil,” or “The Sunburn,” and sent out bottles of branded sunscreen in the invitation. A 1,600-foot-long bright-fuchsia runway was cut through rows of flowers, streaking across the groomed hillside like a neon highlighter. If you search #provence on Instagram, you will find 3.4 million photos of basically the same field, but without the hyperreal pink, which was inspired by both an iPad painting by David Hockney and the work of artists Christo and Jeanne Claude. The effect was FOMO-gasmic on social media — an enchanted image of France by an adorable young French designer who embodies the beguiling ideal of a carefree and well-tanned garçon.

Summer is at the heart of Jacquemus, the designer and his brand. As a child, he was nicknamed Mr. Sun, and this anniversary show was timed to what is still called “cruise” season. And it was you’d-better-not-be-wearing-much hot: On the day of the show, it was over 90 degrees without a cloud in the sky. Models were falling. Cell service was scarce. Same for bottled water, briefly. Celebrities like Emily Ratajkowski, editors like Emmanuelle Alt of French Vogue, and the designer’s entire extended family were all given more sunscreen and parasols upon arrival. Actually, wait a minute … Where is la grand-mère de Jacquemus? Someone forgot to pick her up. The show started about an hour late, just as the sun began to fade.

“It was really like Fyre Festival,” Jacquemus told me afterward with a laugh. “But only for, like, ten minutes.” His skin was the color of a baguette, and his shirt unbuttoned to reveal a bountiful patch of chest hair. “Everyone was like, ‘Ahhh!’ But me, I was like —” He theatrically inhaled and exhaled. “I went for a walk in the lavender.” Later that night, pizza and bottomless rosé were served, and he danced under the stars with his boyfriend, Marco Maestri, who looks rather a lot like him and is the brother of the French rugby player Yoann Maestri, half-naked star of the recent Jacquemus menswear campaign.

Better to not think too much about how this glorious heat wave was also evidence of climate change. “Sun in your face, sun in your face, sun in your face,” the designer told me, clapping his hands like a windup toy for emphasis. “I’ve been like this since the beginning. I’m not doing, like, an end-of-the-world show.”

Jacquemus, 29, was raised in the village of Mallemort — population around 6,000 — not far from here. He likes to say that his barefoot country upbringing instilled in him a sense of “naïveté.” He uses that word a lot. Even his Instagram bio — he has 1.4 million followers and was a Tumblr native before that — reads like it was written by a 10-year-old: “My name is Simon Porte Jacquemus, I love blue and white, stripes, sun, fruit, life, poetry, Marseille, and the ’80s.”

Critics sometimes roll their eyes: He’s been called both “pretentious” and a “bumpkin,” strong on pithy branding but short on craft. The Financial Times recently mulled whether Jacquemus should be better thought of as a designer or an influencer and decided maybe he’s … both, and that’s very right-now of him. Certainly, he’s a person who makes fashion for influencers, including Kylie Jenner and Hailey Bieber, formerly Hailey Baldwin. (A recent campaign was done in collaboration with the Instagram-famous artist of louche, yet somehow innocent, self-display Chloe Wise.) However much it is part of his authentic self, or just the discipline of a young man raised on the mantra of having a “personal brand,” his social-media optimism is what sets him and his clothing apart. He doesn’t take things too seriously, or seem to suffer for his art. Even in person, he’ll tell you how he’s “realizing his dreams.” How he’s “very in love.” And how his “only goal,” in work and in life, is “being ’app-ee.”

His parents were farmers — his mother specializing in carrots, his father spinach. But Jacquemus was clearly too charming, too ambitious, and too cute for the non-hashtag version of life on the farm. (He was cast in a Carambar’s-candy campaign as a kid, and Karl Lagerfeld once called him “rather pretty” on the subject of his work.) Instead, Jacquemus dreamed of glamour, obsessing over French cinema and studying copies of Italian Vogue. At the age of 8, he wrote a letter to Jean Paul Gaultier asking to be his stylist, arguing that it would make for good press. On weekends, Jacquemus sold vegetables on the side of the road. He learned to spot tourists from Paris, who were his frequent customers. It’s a lesson he’s held onto.

Soon he made his way to the city to attend the École Supérieure des Arts et Techniques de la Mode, at 18, in 2008. He quickly learned that the Parisian woman didn’t seem to enjoy herself much. “I was like, Okay, not at all,” Jacquemus remembers, scrunching his nose. “Not. At. All. They don’t have the smile. I have no interest in people who don’t have a smile.” Maybe his mission has been to change that.

A Jacquemus micro-bag. Photo: Moda Operandi/Courtesy of Jacquemus

Three days before the Jacquemus anniversary show in Provence, a gaggle of casually dressed employees could be found laughing and smoking cigarettes outside his new studio on Rue de Monceau in Paris. He moved to the new location from Canal Saint-Martin a few weeks earlier in June — coincidentally on his late mother’s birthday, which he only realized the morning of.

The door to the Jacquemus operation is a classic French blue but more teal than others on the block. I entered to find a lemon tree thriving inside the large white atrium. The secretary also had one on his desk and fondled it like a stress ball. Jacquemus was upstairs in the middle of a model fitting and excused himself to hit play on a pop-lullaby soundtrack via his iPhone. Sunlight poured in through large windows, bouncing off his gold jewelry as he gestured with his large, thick fingers. Did I mention he has blue eyes?

“I didn’t choose this location; I had a crush on the location,” he tells me with a grin. “I visited, and I saw all the little balconies and the garden, and I was like: This is not Paris.” When I ask him if the grand staircase and high ceilings give his operation gravitas, he scoffs. “No! Lightness!”

Over the past few years, Jacquemus has doubled his staff from 30 to 60. Almost everyone, he says, has remained since the beginning, including his ex-roommate, Fabien Joubert, who now serves as the brand’s commercial director. Sales have doubled every year since 2017 as well and are supposedlyon track to hit $20 million by the end of 2019.

Things are going so well that rumors of Jacquemus being acquired by a larger conglomerate, like Puig or LVMH, circulate every so often, along with theories of a secret backer. But when I ask about them, he maintains he’s still independent and is “not looking” for any investors, or for that matter looking to helm a bigger label (there was also a rumor he was being considered for Celine). It’s possible no one is knocking on his door, or he’s been passed up for other, more experienced names. But Jacquemus seems focused on keeping it in the family. “If you want to do everything sincerely, how can you leave your own building?” he asks. “It’s not about more, more, more. My generation is going to take care of themselves.” When things get stressful, he does karaoke: “Any song by Céline Dion,” he tells me.

Which isn’t to say he doesn’t let his brand slip sometimes: He admits that “there’s always something melancholic about my work.” But he wouldn’t go into it.

Because Jacquemus refuses outside help, the company is still a relatively scrappy operation — one that used to fulfill orders to its 300-something global retailers “quite late within the delivery window, which commercially is not ideal,” a forgiving Moda Operandi buyer told me. Runway producer Alexandre de Betak explained that they kept the budget for his anniversary show “exceptionally small.” His team spent the weekend before clearing the wheat and lavender fields themselves, and there was “absolutely no plan B” to account for bad weather.

“If the creativity of the way we show is good enough, then it’s fine that we’re far away, at the wrong time, with a very small audience, because it will go viral,” de Betak added. “I think that’s what happened with the show in Provence.”

“There’s an expression in France, saying that you put the donkey before … Uh, no, you put the donkey after … Do you know this?” Jacquemus asks.

The cart before the horse?

Something like that. “I always think that way,” he continues. “For me, it was the ten-year anniversary, so it was important to say loudly: I have a big house, and it’s Jacquemus. It’s not anything else, and I own it. I’m here.”

The spring 2020 ready-to-wear-collection show in a lavender field in the south of France. Photo: Arnold Jerocki/Getty Images

One month into his first semester at fashion school, Jacquemus’s mother, Valérie, died in a car accident. He dropped out shortly thereafter and started his own line. Jacquemus was her maiden name. “I didn’t want to waste time,” he said later of the choice. “I wasn’t learning anything there anyway.”

Jacquemus paid a curtain-maker €100 to sew his first piece, staging a fake “protest” outside Dior on Avenue Montaigne during Paris Fashion Week for his debut show. He always had an instinct for a media stunt. “French people love striking,” he told the press. “Strike uniforms are so sexy!”

By 2012, he’d worked his way onto the official Paris Fashion Week calendar, one of the youngest designers ever to do so. His breakout show took place in a swimming pool. Critics were charmed by the “innocent,” “playful,” almost panderingly French aesthetic of his early collections. Phrases like J’AIME LA VIE were printed over pictures of sailboats. “I remember him telling me: ‘I’m a daytime designer,’ ” recalled Clara Cornet, who is now a creative director at Galeries Lafayette (where he recently opened his own lemon-themed café, Citron). “There are nighttime designers, and I am daytime.”

To fund his collections, which were minimal simply because that’s what the budget allowed, Jacquemus got a job working as a sales assistant at the Comme des Garçons store on Rue du Faubourg Saint-Honoré. Adrian Joffe, Rei Kawakubo’s partner in business and life, became a supporter, stocking the brand at Dover Street Market after only a few seasons. “He charmed me,” Joffe said in an email. “I was so impressed with his vision and his conviction.”

Working at Comme allowed Jacquemus to support himself. He also calls the experience his “real school.” To start, he learned who Kawakubo was. (Thanks, Google.) He also internalized what he calls the “Rei Kawakubo spirit,” which is “following something forever, like a line.” In other words, sticking to your guns, even if those guns spew rainbows. He also discovered that affordable products, like Comme des Garçons: Play T-shirts and wallets, can fund more “arty” endeavors. One of Jacquemus’s first hits, for example, was a simple red, white, and blue T-shirt from the fall 2014 collection. He also tried his hand at more intellectual projects, dressing women up like paper dolls, as Kawakubo did in 2012, but the results were less avant-garde and more arts-and-crafts.

Despite his connection to Joffe, and his growing circle of French “It” girls like DJ Clara 3000 and Jeanne Damas, Jacquemus still felt like an outsider. “I don’t have a lot of friends in fashion,” he says. “From the beginning, I was by myself and doing it a bit by my own rules.”

In 2015, Jacquemus won the LVMH “Special Jury Prize” for emerging talent — a stamp of approval from fashion’s ultimate insiders as well as the source of a €150,000 check and a yearlong mentorship. Because he had no formal training, his adviser, Sophie Brocart, suggested that he invest in staff members with “technical expertise” and take on the role of CEO, or face of the brand, himself. Most designers his age aren’t up for that. Even if he didn’t graduate at the top of his class from Central Saint Martins, Jacquemus did have “the right personality, vision, and charisma” to succeed, in Brocart’s opinion.

With seasoned tailors now on his team, the Jacquemus silhouette came into focus. His deconstructed suiting, for example, now looked like it was falling apart on purpose. Following a strong spring 2016 show, The Business of Fashion dubbed Jacquemus the “hottest young designer in Paris.” He was no longer “just cute or French, or a sensation,” as Jacquemus himself put it. Better yet, he was making money.

Gradually, Jacquemus evolved his aesthetic. The arty Comme des Garçons influences began being edited out. For spring 2017, he returned to the sunny, Spanish-influenced style of his youth — lace blouses, straw hats, matador shoulders, and corseted waists — inspired by the flirty theatricality of Christian Lacroix’s ’80s haute couture. The following collection imagined what it would look like if a Parisian girl fell in love with what he’d referred to as a southern “gypsy.”

After he found a photograph of his mother wearing a headscarf, ceramic earrings, and a wrap skirt, the Jacquemus woman we know today, or “La Bomba,” suddenly came to life. For starters, you could actually see her. Instead of oversize blazers, she wore droopy button-up shirts that exposed her breasts and itty-bitty, skintight knits over her long, tan legs. Spring 2018 marked a return to his roots, but instead of Charlotte Gainsbourg, his muse was his own DNA. “She was sexy,” Jacquemus told Vogue of his mother, recalling the “village beauty” who was always smiling. Pretty soon, he became known as the guy who calls his mom “sexy” — but is there anything more French than that?

Skimpy summer collections like “La Bomba” have doubled in revenue each year, but the success of that particular season also had to do with its introduction of playfully scaled accessories. To balance out gigantic straw hats the size of a Hula-Hoop, Jacquemus designed miniature leather bags, shrinking a style from the previous season down to a crossbody that measured just two and a half inches tall and four wide. “People were like, ‘Simon, it’s never going to sell; you can just put some cards and keys in it,’ ” the designer recalls. “I was like, ‘Mmm, I’m sure it’s going to sell. It’s too cute and too viral not to.’ ”

He was right. Le Chiquito was snatched up by Rihanna, Beyoncé, and Kim Kardashian at $520 a pop, and handbags now account for more than 30 percent of revenues. (Its pleasures are hard to explain, or maybe justify, but — full disclosure — I own one, and love it. Not only does it free me from the tyranny of stuff, but holding its cute little handle gives you the same pleasure zap as looking at a lavender field through a tiny phone screen.)

Le Petit Chiquito’s even-tinier spawn, Le Micro Chiquito, which debuted in February at the size of a binder clip for $258, is selling out as well, despite the fact that you can’t put anything in it. “If you don’t consider it a bag, consider it jewelry, you know?,” the designer said this summer, tossing it over his shoulder with one finger. Memes abound.

Last year, Jacquemus teased his followers with rumors of a #newjob, but the big reveal turned out to be menswear. His first collection, shown at a beach in Marseille, was a hunky answer to La Bomba. Titled Le Gadjo, which, he explained, is local slang describing a type of tourist: “He’s a bad-taste guy, but he’s cute.” Similarly, his show in the lavender field had a second level you might not notice, referencing the tourists he used to sell vegetables to when he was young, with clever cosplay of farmer chic. Models in loud floral prints sported fake tan lines and corn-on-the-cob key chains in the style of people who clumsily overcompensate for being visitors by dressing a “bit too much where they are,” as he puts it. Expect to see this look in your feed. So many people are posing naked on beaches underneath one of his La Bomba giant straw hats that the manufacturer ran out of straw.

This is his insight, his particular genius. He knows we’re all posing, hoping for a hashtag selfie in the sun.

0 notes