#sir george cockburn

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

#polls#napoleonic#dressed to kill#sir george cockburn#charles stewart#Your Character Here (early 19th century naval edition)#age of sail#maritime history

26 notes

·

View notes

Note

Apropos your recent remarks on Regency men, the great outdoors, and military service, do you think the picture of Washington, D.C. burning is strictly necessary for this variety? Or only statistically probable? I'm worried it would clash with my collection of pastoral landscape paintings, but also wouldn't want to deprive the Regency man of necessary enrichment. Should I be looking at a different type of 19th century man more compatible with my art collection?

Hello! I am jumping ahead in the order of asks to respond to this question about managing expectations for Regency men.

The portrait with Washington, D.C. in flames is not strictly necessary for perhaps the great majority of men in this time period; but you must allow for the iconic nature of Sir George Cockburn's c. 1817 portrait in his rear-admiral's pattern 1812-25 undress coat with Hessian boots and spurs, and the burning Capitol buildings in Washington behind him. The ultimate statement in military might and Napoleonic-era civilian fashion, melded together in an expression of brilliant masculinity!

It's pronounced COH-burn, for your information.

Despite all this, some would baulk at the underlying violence of such a portrait. If your 19th century man has a penchant for this sort of display, he may be content with a comparable marine tableau—perhaps HMS Shannon capturing USS Chesapeake!

Surely, this majestic view of Halifax Harbour will compliment any pastoral landscape.

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

On February 12th 1624 George Heriot, goldsmith to King James VI and founder of Heriot’s School, died.

George Heriot was probably born in Edinburgh, where he followed his father into a career as a goldsmith. His premises consisted of a booth near St.Giles in Edinburgh. In 1588 he was made a member of the Incorporation of Goldsmiths and was elected their Deacon in 1593.

He became very wealthy through money lending, and his clients included King James VI. James appointed George goldsmith to his queen, Anne of Denmark, in 1597 and, in 1601, he was appointed jeweller and goldsmith to the king himself. When James succeeded to the English throne,

Heriot moved to London and set up at the Court of St James in London. He was widowed twice. He married Christian Marjoribanks in 1586. She died about 1603. His second wife, Alison, the 16 year old daughter of Archibald Primrose, writer in Edinburgh, whom he married in 1609, died during her first pregnancy in 1612.

He died on this day 1624 and was buried at St. Martin-in-the-Fields, London. His legendary wealth inspired the character of ‘Jinglin’ Geordie’ in Sir Walter Scott’s novel 'Fortunes of Nigel’ and in turn the Jinglin’ Geordie bar on Fleshmarket Close just off Cockburn Street.

He left no surviving legitimate children, but bequeathed a substantial amount for the provision of a hospital school in his home city for 'puir faitherless bairns’. His hospital is now George Heriots School, Heriot-Watt University also perpetuates his name.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

On the Emperor’s first arrival in St Helena, he was fond of taking exploring walks in the valley just below our cottage. In these short walks he was unattended by the officer on guard, and he had thus the pleasure of feeling himself free from observation. The officer first appointed to exercise surveillance over him when at Longwood was a Captain Poppleton of the 53rd Regiment. It was his duty to attend him in his rides, and the orders given on these occasions were, ‘that he was not to lose sight of Napoleon.’ The latter was one day riding with generals Bertrand, Montholon, Gourgaud, and the rest of his suite, along one of the mountainous bridle-paths at St Helena, with the orderly officer in attendance. Suddenly the Emperor turned short round to his left, and spurring his horse violently, urged him up the face of the precipice, making the large stones fly from under him down the mountain, and leaving the orderly officer aghast, gazing at him in terror for his safety, and doubtful of his intentions. Although equally well mounted, none of his generals dared to follow him. Either Captain Poppleton could not depend on his horse, or his horse was unequal to the task of following Napoleon, and giving it up at once, he rode instantly off to Sir George Cockburn, who happened at the time to be dining with my father at the Briars. He arrived breathless at our house, and, setting all ceremony aside, demanded to see Sir George, on business of the utmost importance. He was ushered at once into the dining room. The Admiral was in the act of discussing his soup, and listened with an imperturbable countenance to the agitated detail of the occurrence, with Captain Poppleton’s startling exclamation of ‘Oh! sir, I have lost the Emperor!’ He very quietly advised him to return to Longwood, where he would most probably find General Buonaparte. This, as he prognosticated, was the case, and Napoleon often afterwards laughed at the consternation he had created. On Captain Poppleton’s arriving at Longwood he found the Emperor seated at dinner, and was unmercifully quizzed by him for the want of nerve he displayed in not daring to ride with him.

-To Befriend an Emperor: Betsy Balcombe’s Memoirs of Napoleon on St Helena

39 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Rear-Admiral Sir George Cockburn by John James Halls. In 1815 he took Napoleon to St. Helena on The Northumberland and stayed there as governor until Hudson Lowe arrived. In this painting, Washington DC is burning behind him because he was part of that military operation; I suppose he was quite proud of it! see the painting

#Sir George Cockburn#English admirals#The Northumberland#St. Helena#War of 1812#Not bad looking at all#Fall of Napoleon

16 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Marbled Monday

Today’s lovely marbling comes from the book The Lives of Dr. John Donne, Sir Henry Wotton, Mr. Richard Hooker, Mr. George Herbert, and Dr. Robert Sanderson by Isaac (or Izaak) Walton (1593-1683). Walton is best known as the author of The Compleat Angler, a book of verse and proses about the spirit and art of fishing.

Walton’s original biographies of these men were published individually over time and then as a collection in 1670 and then again with subsequent additions in various editions. This edition was published in 1807 and was printed by T. Wilson and R. Spence in York, England.

The marbling mainly features a nice reddish-orange color sprinkled over blue, black, and cream. You can see the color difference between photographs of the marbled paper and the final image here, which was captured with our flatbed scanner. The scanner image better shows the pops of blue in the marbling, but the photographs come much closer to the actual color of the reddish-orange. To create this pattern, the darker colors would have been dropped into the water/sizing combination first, followed by the reddish-orange and the cream color, causing the darker colors to constrict and create the look we see here. This is called a Turkish pattern, though it seems like the term is sort of loosely associated with this method more than being strictly about the pattern.

The cover is blind stamped with a nice diamond pattern and the edges of the book are marbled to match the end sheets. There are two bookplates on the front end sheets, one for a Henry Cockburn and the other for David Cleghorn Thomson. Both were Scottish!

View more Marbled Monday posts.

-- Alice, Special Collections Department Manager

#Marbled Monday#marbling#marbled paper#John Donne#Sir Henry Wotton#Richard Hooker#George Herbert#Robert Sanderson#Izaak Walkton#Isaac Walton#T. Wilson and R. Spence#York#Turkish marbling#patterned paper#paper marbling#Henry Cockburn#David Cleghorn Thomson

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

Not that I know much about the aubreyad, but the War of 1812 is very underappreciated in general and deserves so much more attention. If time-traveling and teleporting Admiral Sir George Cockburn wanted to burn down the White House five different times I would absolutely support him.

*patrick o’brian voice* the war of 1812, 1812a, 1812b, 1812c-

#aubreyad#war of 1812#sir george cockburn#im love him#he was on the right side#and didn't get the support he needed#royal navy#dressed to kill

620 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Captain Peter Parker (1785-1814), by John Hopper, made 1808-1810

He was the son of Vice Admiral Christopher Parker, who in turn was the son of Admiral Sir Peter Parker, 1st Baronet, and Vice Admiral John Byron's daughter Augusta Byron. The poet George Gordon Byron, 6th Baron Byron, was his cousin.

Parker attended Westminster School and was in the Royal Navy from 1798, serving under his grandfather, Viscount St Vincent and under Lord Nelson. In 1804 he became Commander and commanded the brig Weazel. She was the first to observe the departure of the Franco-Spanish fleet from Cadiz in the run-up to the Battle of Trafalgar, for which Parker was promoted to Captain. In 1809 he married Marianne Dallas, daughter of Sir George Dallas, 1st Baronet, and had three sons. His son Peter Parker (1809-1834), 3rd Baronet, was Commander on HMS Vernon.

In 1810/11 he was briefly a member of the House of Commons as MP for Wexford. On the death of his grandfather in 1811 he inherited the peerage of Baronet, of Bassingbourn in the County of Essex.

In 1810 he was given a command on the frigate Menelaus. He was involved in the suppression of a mutiny on the Africaine and in the capture of Mauritius in late 1810. In 1812 the Menelaus was part of France's naval blockade of the Mediterranean, particularly off Toulon, and from 1812 he was engaged in the British-American War against the USA, breaking up ships on the Maryland coast and attacking coastal towns. In 1814 he operated against the French in the Atlantic, capturing a valuable Spanish merchant ship as a prize in January.

After the French surrender in 1814, he was sent to Bermuda and from there to the Chesapeake Bay, where he blockaded Baltimore under Admiral George Cockburn and interdicted American commercial traffic. He also ruthlessly destroyed farms and American property along the coast. He had already been ordered back from the Chesapeake Bay after the destruction of Washington, D.C. by the British, but after a night meal with his officers, he wanted to attack once again in a commando raid a unit of Maryland militia that had set up camp near Chestertown, Maryland. A one-hour night hand-to-hand fight developed in which the British were repulsed and he was hit in the leg and bled to death before he got back to his ship. In 1814, Lord Byron wrote a poem in his memory.

69 notes

·

View notes

Link

September 1814

“It’s an armada,” Madison fumed, pacing before his desk. “How can we not even know which direction it’s sailed?”

Silence filled the office.

Hamilton’s gaze was fixed on the view outside the ornate curved windows adorning Madison’s new office. The glittering chandelier overhead hadn’t been lit, unnecessary with the good light pouring in on all sides. The splendor was second, perhaps, only to President’s House, which lay some streets beyond, now little more than a burned husk.

His head still ached, a constant dull throbbing between his temples. The bruising on his face had faded to an ugly yellow in the intervening time since Bladensburg, though his arm was still wrapped tight and fixed in a sling. At least it hadn’t been his writing hand that had been injured.

Eliza hadn’t wanted him out of bed so soon, but after over a week of bedrest, he’d needed to feel useful again. The ride to Tayloe Mansion, where Madison had taken up residence, had been his first real glimpse of the horror and destruction wrought to their capital city. He stared out at the ruined homes beyond the window, a sick feeling in the pit of his stomach.

“Richmond, Norfolk, Annapolis, and Charleston are all bracing for attack,” Monroe said, finally, when no one volunteered an answer.

The pause had been too long; a sure sign that the person designated to answer wasn’t present. Hamilton glanced around at the assembled statesmen, taking a count. The Secretary of War was notably absent. “Where is Armstrong?”

Madison huffed. “I suggested he might take a short leave, lest he wander down the wrong street into the waiting arms of a bloodthirsty mob.”

“You didn’t demand his resignation?”

“We have bigger problems to worry about than Armstrong.”

“Who is the acting Secretary?”

Madison gave him a considering look.

“No,” Hamilton said firmly.

Madison nodded. “Fair enough. I need you in command anyway. You’ve become quite the rallying point for the men in last week. Colonel Monroe has offered to shoulder the burden temporarily.”

“Shouldn’t you be monitoring the progress of the peace talks in Ghent?” Hamilton asked.

“I can do both,” Monroe said.

Hamilton gave a skeptical hum. “Well, it’s not as if you can be less effective than your predecessor, I’ll grant.”

Monroe straightened in his seat, offense plain on his face.

“Richmond, Norfolk, Annapolis, Charleston,” Madison repeated, stepping between them. “Which one do we anticipate the British striking next?”

“None of them,” Hamilton said. “They’re riding high on their victory. They’ll want the jewel.”

Madison frowned at him.

“Baltimore,” Monroe explained, nodding. “They’ll head for Baltimore.”

“Who is in command of the defenses at Fort McHenry?” Madison demanded.

“Major General George Armistead,” a clerk supplied after a short pause, papers rifling.

“Armistead is working with Major General Samuel Smith, commanding the Baltimore Militia. Smith has refused to cede command to General Winder,” Monroe added. “Winder was in my office yesterday pitching a fit.”

“I can’t say I blame him. We don’t exactly have a sterling record.” Hamilton cocked his outside to indicate the ruin of Washington City beyond.

“Sir?” A clerk poked his head into the office timidly. “Dr. Thornton to see you.”

“Not now.” Madison waved him away.

“Sir, he’s most insistent.”

“What is it about?”

“Something about an American prisoner of war.”

“A patriot of highest caliber!” The incensed shout came from the outer chamber.

Madison rubbed a hand over his eyes. “Let him in.”

Thornton stormed into the room, his finger already wagging. “I demand something be done immediately, Mr. President. William Beanes is a fine American, a veteran, who served under our most revered and esteemed General Washington during the war for independence. He helped bandage our brave soldiers after the Battle of Brandywine.”

“What’s happened to him?” Hamilton inquired in a bid to avoid a full recounting of Beanes’ war record.

“When word reached Dr. Beanes of the British atrocities in our capital, he arrested a group of British soldiers who had yet to return to their ships. General Ross immediately sent out a detachment. Dr. Beanes was accosted in his home, ripped from his bed in the dead of night, and treated most shabbily. Now they say he’s set to be tried for treason in Halifax. He’s being held prisoner on a British warship. I say, this cannot be allowed to stand.”

Madison sighed. “I’m inclined to agree. Who was that man, the navy pursuer – Skinner? He warned us about Cockburn?”

“John Stuart Skinner,” Monroe confirmed.

“Send him out after the British ship. Authorize him to negotiate for the safe release of Dr. Beanes.”

Thornton deflated somewhat at the easy victory. “Thank you, Mr. President.”

“Good day, Dr. Thornton,” Madison replied, nodding towards the door.

When Thornton had left, Richard Rush asked, “How exactly are we supposed to send Skinner after the British fleet, if we aren’t even sure where they are?”

Madison met Hamilton’s eye. “How sure are you about Baltimore?”

“It’s where I’d be heading if I’d just won a victory such as theirs.”

“Baltimore does seem the most tempting target available,” Monroe agreed.

“We’ll tell Skinner to head in that direction, then. If he’s successful, all the more support for our theory. Now, do we send Winder to reinforce Baltimore over the militia commander’s objections?”

“Does Smith have a strategy?” Hamilton asked Monroe.

“He’s already begun reinforcing McHenry for a siege. The key to keeping the city will be to keep the British out of the inner harbor.”

“What’s their fire power?”

“Fifty mounted guns and about a thousand men.”

Hamilton considered a moment. “I say we send men to help reinforce the militia, but leave Smith in command. The last thing we need is a squabble at the top wasting valuable time.”

Madison nodded. Sizing Hamilton up, he asked, “Can you ride?”

Hamilton gestured to the sling securing his left arm to his body. “I doubt it. I’m currently down to one working limb.”

“We can take a carriage, then. I’d like you to come with me to review the men before we give the orders to march for Baltimore.”

“Of course, Mr. President,” Hamilton agreed.

“Sir, about the budget shortfalls,” Secretary Campbell began, before pausing to cough wetly into a handkerchief.

Madison heaved a sigh. “There’s nothing we can about that at the present moment.”

Campbell cleared his throat. “If we don’t have a treaty by year end, we may not have funds enough to continue paying our standing army.”

Hamilton gave Madison a significant look.

“I know, I know,” Madison griped at him. “The bank. The blasted bank will cure all our ills, and it never should have been allowed to expire in the first place.”

Hamilton held his right hand up, palm facing out, placating.

Madison collapsed into his chair, shoulders slumped. “I can’t even get Congress to agree to keep Washington as the capital right now, never mind agree to recharter your bank. They’re all crammed into the Patent Office arguing with each other about which of their cities is the obvious choice to be the seat of government.”

“Bank charters. Disagreements over the location of the capital. Is it possible I hit my head so hard I ended up back in 1790?” Hamilton teased. “This all sounds frighteningly familiar.”

Madison chuckled wearily. “If you did, you’ve brought me with you.”

“My sincere apologies.”

“Well, we managed it once before, didn’t we?”

Hamilton nodded. “We did, indeed.”

Madison gave him a fond look before casting his gaze over the assembled cabinet. “Anything else, gentlemen?”

**

Hamilton’s whole body tensed, alert, at the soft creak of the floorboards. No knock followed. His heart beat hard in his throat as he waited for more sounds in the dark.

“It was probably one of the children,” Eliza said wearily from beside him.

“What?”

She rolled over in bed and adjusted closer to him. “One of the children,” she repeated. “You need to relax. Get some rest.”

“I can’t.”

“Honey,” she sighed. Her fingers combed through his hair, gentle, mindful his bruising even in the dark.

“I should be there. Helping. Doing something. How can we have no word? Nothing, for hours now.”

“It takes time for riders to make their way from Baltimore,” she said, frustratingly practical. “You may not hear more until late tomorrow.”

“The bombardment had started. They must know something.”

“Torturing yourself all night isn’t helping.” She pressed a kiss to his cheek. “Go to sleep.”

“I can’t sleep,” he repeated. He pushed himself up against the pillows with his one good arm, dislodging Eliza as moved. “Maybe if I leave now, I can be close enough to the city to hear word in the morning.”

He felt her sit up beside him. “The riders would go right past you, come here, and be obliged to turn around to go find you on the road. How would that help?”

“I’d be doing something.”

She sighed.

The mattress shifted, and he felt Eliza push the blankets aside. She lit a candle on the bedside table, and he blinked in the sudden light. Rising from the bed, she shrugged on her dressing gown.

“Where are you going?” he asked.

“I’m going to run you a bath,” she said.

“A bath?”

“You need to relax. You’re wound tight as a drum. A nice hot bath will help.”

He shook his head as she padded from the room. The fate of the nation hung in the balance, his mind spun at a dizzying speed, and she wanted to fix it all with a bath. Annoyingly, he knew it would probably work, too. His darling, dearest wife.

Some minutes later, she returned, and began to situate his chair into place. Wordlessly, she wrapped her arm under him to help shift him over into the seat, a task hugely complicated by having only one working arm. Candlelight glowed in the adjourning chamber. She pushed him inside, the tub set up in the center of the room, steaming invitingly.

She gently untied the sling at his neck, her fingers warm and soft as they tickled against the sensitive skin. Next, she unbuttoned his night shirt, sliding it out from under him and slowly pulling it over his head. His left shoulder ached when he lifted it, and the shirt grazed his bruised temple, causing him to let out a soft hiss.

“Sorry,” she muttered.

He shook his head. “It wasn’t you.”

Carefully, she guided him over onto the strategically placed seat in the tub. She submerged his legs, then had him lean against her as she pulled the seat out from under him, letting him sink down into the blessedly hot water. He groaned with pleasure at the sensation, the tension in his muscles easing.

“How’s that?”

“Mm,” he hummed. “Heavenly.”

She gave him a smug smirk.

“Hush,” he cautioned.

She shifted around to sit behind him. A soft towel cradled his neck, and Eliza began to gently massage his shoulders. He melted at her touch. She leaned further over and pressed a kiss to the top of his head.

“Relax,” she whispered.

He closed his eyes and obeyed.

She shifted him forward to wash his back, then had him lean back again. He drifted towards sleep under her tender ministrations, not eager to move even when the water began to turn tepid around him. The soft candlelight and her loving touch held back the visions of battlefield slaughter that had plagued him the past weeks every time he closed his eyes.

“Sweetheart?”

“No,” he moaned.

“Come on,” she insisted, prodding him. “Lets get you to bed. You’re half asleep already.”

His eyelids felt heavy, and he was pliant as a wet noodle as she began the process of extracting him from the tub. With little help from him, she dried him off, slipped his nightshirt back in place, and got him situated back in bed. He was asleep the moment his head hit the pillow.

**

The deep, dreamless sleep had helped ease the constant headache he’d been suffering, but he still found himself entirely on edge for much of the next day.

“You have to eat something, sweetheart,” Eliza insisted as he pushed a piece of mutton around on his plate at their afternoon meal. “You need to keep up your strength. You’re still healing.”

But a nervous squirming sensation had taken root in his stomach, and he couldn’t bear the thought of eating. He needed news. Something, anything to tell him how the fight was going in Baltimore.

A sudden knock at the door had him sitting straight up in his seat. He pushed at the wheel of his chair, but made little progress with one hand. Eliza rose from her seat while he struggled.

“You stay,” she directed, running a hand over his shoulders as she passed. “Eat.”

She hadn’t gone more than a step into the hall when the door burst open, however, the visitor evidently unable to wait for an answer. The aide hurried in past Eliza, breathless, holding a piece of paper out before him. “Fresh from the front, General.”

Hamilton grabbed the page, slid his finger under the seal, and unfolded the paper so hastily it wrinkled in his hand. A single line had been scribbled across the page. His eyes flew over the information, his brain a moment delayed in understanding.

Then he smiled.

“What does it say?” Eliza asked, nervous anticipation that had been carefully masked from him before now obvious.

He held the page up for her to read.

“September 14, first light - The stars and stripes still wave over Fort McHenry.”

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

some irving things i learned from his memoir:

liked reading and rereading euclid

won the infamous maths medal when he was 15yo

read the ships’ library many times over. once forced a book on a middie as a way of making friends. it did not work.

was middies with william malcolm and george kingston, whom he kept correspondence with for years even after they left the navy

ridiculously tender w/ his friends. “i can fancy you laughing at this. however, you know that, with you, i speak just what i think, and i have no one else in the world whom i can do that to but yourself.”

also: “it is tantalising to think that you are just on the other side of these blue hills, but i can’t get at you.”

also: “you are my earliest friend. i never knew the meaning of the word until i met you... there is little in this world would give me so much real hearty pleasure as giving you a squeeze of the hand.”

was always lonely and thought he had no true friend. maybe this is why he and crozier got along??? “i have not one friend in the ship (not the terror yet), although i am on tolerably good terms with them all” vs. crozier’s “i am sadly lonely. not a soul have i in either ship i could go and talk to. no congenial spirit as it were.” someone pls give these sailors a hug

was religious, really religious. he mused on his future life as a settler in australia: “i should have my own house, however small, and i should be more out of temptation to sin, and be able to lead a life fitted better to my improvement as a christian, than on board ship” which is where i think the terror writers got “we are separated here from the temptations of the world... your crisis is an opportunity for you to repair yourself. you are in the world’s best place for it.”

shookt by all the swearing and obscene talk in ships and their irreverent way of practicing religion

was moved by a chorus of ship passengers warbling to church songs

irving: i’ve got to make my own living, my dad’s almost fourscore yrs old narrator: his dad was only 63.

gossiped abt his captain marrying a girl who was young enough to be his daughter

visited his captain’s sick wife while he was on shore leave bc the captain couldn’t go himself

was in malta during the coronation of king otto of greece. do u know who else was present in the coronation and was waiting on otto himself? j f j

saved 1-2 people when his boat was overturned by a gale.

climbed mount etna and got a permanent injury in his upper lip due to frostbite. his upper lip protruded and this significantly changed his appearance.

had 2hr smoking sessions almost every evening. he was bored as hell.

forever moaned about promotion prospects. i guess this was a pretty common thing back then.

was a mate for approx. 5yrs, then bc he didn’t think he would ever be promoted, fucked off to south australia to be a sheep farmer for 4yrs, then went back to the navy by 1843, got promoted to lieutenant along the way

irving: australia is so beautiful! what a simple life i lead, im so happy irving, 4yrs later: the sheeps have gone dirt cheap, this place is terrible and i wish to forget all memory of it

couldn’t negotiate sheep prices to save his life

since he essentially went off-grid for 4yrs, he had no fricking clue what had been happening at scotland and ireland when he returned, i.e. the beginning of the famine and tenants being booted out of the highlands to accommodate sheep, so he abstained from developing political opinions on it.

thought the irish friendly and accommodating, if primitive

joined hms excellent to take gunnery courses, as did many of the officers in the franklin expedition

wrote to his patron sir george clerk that he wanted to join the next arctic expedition, who wrote to sir george cockburn, who i guess made it happen

got appointed to hms terror as 3rd lieutenant on march 1845

was put in charge of monitoring the chronometers in the ship. this is kind of a big deal. in erebus, that was gore’s job, probably bc he had previous arctic experience. so irving was doing smth a first lieutenant was supposed to.

was a “talented draftsman” and was able to send home one drawing of the erebus and terror being restocked by their supply ship

had “an iron constitution”, had “a greater appearance of manly strength and calm decision” hmmmm, it’s that farmer john vibe going for him

“conducted himself with diligence, attention, and sobriety, and was always obedient”

when his (supposed) bones were re-interred in scotland in 1881, his longtime friend malcolm attended the service.

163 notes

·

View notes

Text

I know that targeting civilian infrastructure is a war crime, but I think that we should make exceptions for objectively hilarious war crimes (with no casualties)—such as the time Sir George Cockburn wrecked the equipment of a hostile newspaper publisher during the invasion of Washington D.C. in 1814 with the zinger, "Be sure that all the C's are destroyed, so that the rascals cannot any longer abuse my name."

#war of 1812#sir george cockburn#sorry this portrait goes hard#also cockburn (pronounced COH burn) had many zingers!#military history#royal navy#dressed to kill#cockburn really wanted to torch the whole town#but private businesses were spared other than his least favourite newspapers publisher#1810s#quotes

93 notes

·

View notes

Text

"The Origins of the Merikens, the African Americans Who Settled Trinidad's Company Villages in 1816" by John McNish Weiss

African-Americans in Trinidad

n 1815 and 1816 Trinidad welcomed over seven hundred free African American settlers, refugees from the War of 1812, the second and last armed conflict between the United States and Great Britain. The majority found their new homes in the south of the island around the Mission of Savanna Grande, now Princes Town, mostly within the area known since then as the Company Villages.

Local history sometimes asserts that they came out of the War for American Independence, though at that time most were not yet born, or that they were part of the West India Regiments, whose settlement at a different time and a different place remains to be fully researched. But the sea-soldiers that were the founders of the Company Villages community were part of a great African American emigration, unparalleled and almost ignored, the largest departure from slavery between the Haitian revolution of the 1790s and British abolition in the 1830s. The Merikens of the Company Villages had been the Corps of Colonial Marines, who saw fighting service with the British in the War of 1812, garrisoned after the war on the island of Bermuda for fourteen months, and disbanded in Trinidad in 1816 to form a new free yeomanry.

The Colonial Marines in Historical Context

This body of young African Americans threw off slavery, took up arms against their former owners as a disciplined military unit, and settled in Trinidad as free and independent farmers, virtually unknown examples of African American pursuit of freedom a full half-century before emancipation. Recruited by the British in Georgia, Maryland, and Virginia, they were a fighting unit much praised for valor and discipline by their British commanders, and admired with consternation by some American observers. They showed a spirited resolve in their dealings with authority, before disbandment and later in Trinidad, where their community was characterized by hardworking independence. In British colonial history, their settlement in Trinidad is notable as the subject of central government direction against local planters' opposition. In British military history, the small but respectful references to the Corps in Royal Marine chronicles can now be supplemented by a comprehensive account of their service and organization. In American slavery history, their armed service against their former owners can be valued for their example of black opposition and resistance to slavery. In British slavery history, they and their fellow refugees represent a first experiment in emancipation, two decades ahead of the imperial event.

White Fears of Black Revolt

During the War of 1812, black aspirations and white fears gave the British a special weapon in fighting the Americans. Concerned Southern slaveholders, recollecting black success in Haiti and viewing the final 1804 massacre there as instigated by the British, might have agreed with advice received in London that, with British aid, the states of Georgia and the Carolinas could turn into black republics. Events in Haiti and, closer to home, the success of well-disciplined Maroons against American military incursions into Florida, demonstrated African Americans' capacity to defeat white forces and, along with the menacing declarations of rebel leaders, served to emphasize British potential for starting a black conflagration that could dismember the United States.

The British took care not to allay this widespread fear. Highly secret orders to the commanders in the field explicitly forbade them to incite revolt while retaining incitement of white American fear as powerful ammunition in the British armory. Echoing the trial evidence of black conspirators were refugees who requested weapons to revenge themselves on the slaveholders, but when the British did come to arm black men it was as a disciplined, trained body under officer command: only with military control could the British contemplate such a step. The men they armed were trained as an organized unit of sea-soldiers, locally knowledgeable and precisely suitable for the hit-and-run amphibious assaults up and down the Atlantic coast demanded by the government in London. These men became the Corps of Colonial Marines.

1813: First Refugees in the Chesapeake

The black population of the Southern states first met the British in March 1813, nine months after the start of the war in June 1812. The British squadron entered the Chesapeake with instructions not only to blockade the ports and damage the American navy, but especially to draw American energy away from Canada by means of a campaign of amphibious harassment. Almost immediately, African Americans - not only men willing to act as guides and pilots, but whole families seeking safe haven and freedom - made their way to the British warships. Commanders had orders to offer protection to people who gave help and to enlist them in the black regiments or else send them to British colonies.

Increasing numbers fled to the British, and men, women, and children rowed out perilously into Chesapeake Bay by canoe to reach the squadron. Deputations of slaveholders were allowed on board British ships to try to persuade their runaways to return but were without success. As one slaveholder wrote, "on being enquired of whether they were willing to return they declined, some of them very impertinently." Charles Ball, in his account of his life in and out of slavery, records how he "went amongst them, and talked to them a long time, on the subject of returning home; but found that their heads were full of notions of liberty and happiness in some of the West India islands."

Detachments of refugees were soon sent first to the Bermuda dockyard, then to Nova Scotia, where a black population had settled mostly after the War of Independence; they were the Black Loyalists who had not gone to Sierra Leone. In this new conflict between Britain and the United States, matters of moral high ground were bandied between the contestants, and when reports reached London that the friendly reception given to refugee families by Royal Navy officers was winning black confidence, a new and unprecedented government policy was formulated: a newly appointed commander-in-chief, Vice Admiral Sir Alexander Cochrane, was ordered to encourage family emigration.

1814: Recruitment in the Chesapeake

When Cochrane took over the command in the Bermuda headquarters in April 1814, he issued a proclamation inviting "all those who may be disposed to emigrate from the United States" to join the British ships and posts. He had sent advance instructions to his second in command, Rear Admiral George Cockburn, to recruit a body of Colonial Marines from refugee slaves, on the model he had employed six years earlier in Guadeloupe, and to find a suitable place in the Chesapeake as a base for British forces and as a safe haven for refugees. Cockburn already had a group of refugees who had stayed with the fleet as volunteers, and these formed the core of the new company he recruited and trained. Within six weeks they were ready, and on May 18, 1814, they enlisted as Colonial Marines.

Among the volunteers who had already joined Cockburn on January 23 were four men who had been heard planning their escape, with one saying determinedly, "I shall go when and where I please." This spirited group helped lead the new corps as the first sergeants. (Two and a half years later they were to lead the Company Villages community itself, as senior NCOs appointed to be the village headmen.) Cockburn selected Tangier Island as his base. Located in the middle of the Chesapeake, it was a small archipelago barely rising out of the water, easily defensible and with a supply of fresh water. The island was widely famous for great revivalist meetings attended by many thousands from around the bay; thus Cockburn could assume that potential refugees over a large area would know the place well.

London's instructions were that recruits for military service were to be enlisted in the existing black corps, the West India Regiments, but the volunteers rejected this commitment to a military life in what they saw as slave regiments, preferring, in a true American spirit, Cochrane's offer of future settlement on their own land. Cockburn's initial doubts as to their potential soon changed to praise their determination and steadfastness. Over the first few months, news of their activities spread, their numbers grew, and they saw active service as guides, scouts, and skirmishers. Their first uniformed engagement at Pungoteake at the end of May 1814 brought their first fatal casualty, followed by two more deaths in the August attack on Washington. According to sources, inspiration rather than disenchantment appeared to have been the result.

The Colonials' exemplary discipline during the burning of the city was praised by officers who had feared a loss of control over the white rank and file in that action. The black corps gave notable service again as a light company in the assault on Baltimore, in which four more were lost: they may have faced Joshua Barney's flotillamen, many of them black sailors, described by some as the only serious fighting force on the American side. In July, the Chesapeake forces were enlarged with ships and men brought from Europe after Napoleon's defeat. Tired veterans of European battles, they suffered illness from both the Atlantic crossing and local conditions, and in September the depleted 2nd and 3rd Royal Marine battalions were reshaped, the enthusiastic Colonial Corps being joined by seasoned but exhausted Royal Marines to make a new 3rd Battalion of Royal and Colonial Marines, three black companies and three white, garrisoned on Tangier Island.

Southwards

At the end of 1814, with the burning of Washington, the attack on Baltimore, and other expeditions around the Chesapeake behind them, Cockburn's forces moved out of the bay and southwards to coordinate with a new venture in the Gulf of Mexico, where a small force had been engaged since earlier in the year. A further invasion army had been brought from Europe to attack New Orleans and take possession of Louisiana, partly to secure British use of the Mississippi and partly to put a limit on American expansion. Cockburn's forces had originally been intended to occupy Cumberland Island off the Georgia coast in November as a beachhead for cross-country supplies to the Gulf of Mexico and as a base for further diversionary harassment, but orders were delayed until December, and extraordinarily bad weather prolonged the journey, with many deaths in the Colonial Marines and their families through illness.

The battle of New Orleans was already over when they finally established themselves on Cumberland Island in mid-January 1815. Like Tangier Island, it lay in waterways well known to the neighboring African Americans, who acted as guides and pilots as in the Chesapeake and who came in the hundreds, taking refuge with foraging parties on land, or crossing to the island and the ships anchored there. Expeditions up the St. Marys River, the border with Spanish Florida, brought refugees from both sides of the river, and a British officer who had been living in Georgia recruited a company from an area he knew well. In the Gulf of Mexico, an expedition up the Apalachicola River, intended to gather Indian support for the British and to recruit blacks from the Maroon communities of Florida and the backlands of Georgia, produced an independent company of over three hundred Colonial Marines. Most remained in the Negro Fort after the war, while only four decided to enlist with the main body.

Cochrane's intention in the campaign for Louisiana was not to offer liberty to slaves there, since the continued prosperity of the region, should it come into British possession under his governorship, depended absolutely on maintaining the body of slave labor. Nevertheless, in the retreat from New Orleans, around two hundred refugees came away with the British; none were recruited into the Colonial Marines but some were taken to Trinidad in 1815.

War's End

Despite early American news of the peace treaty, signed in Ghent on December 24, 1814, cessation of hostilities had to wait for ratifications, exchanged on February 17, 1815, and official notification from the British minister in Washington. Colonial Marine enlistment continued to March 1, and the British withdrew from Cumberland Island two weeks later, and from the Gulf of Mexico in the middle of April. While the British were still anchored at Cumberland Island, Americans made demands for the return of ex-slaves under what they saw to be the provisions of the treaty's Article 1, which took over a decade of discussions, negotiations, arbitrations, and conventions to settle. Cockburn rejected the demands, quoting Blackstone's legal commentaries that a slave arriving on British soil became free and that British ships at war were equivalent to British soil in this respect, while Cochrane (and later Sir James Cockburn, governor of Bermuda and elder brother to George Cockburn) insisted, in response to American approaches, that it was a matter to be decided at the government level.

Cockburn's meticulous reading of the treaty obliged him to except certain refugees whom he ordered to be returned, instructions that the Americans said his officers obstructed. Four newly enlisted men were handed back, together with volunteers who had been trained but not enlisted. For later historians of the Royal Marines, the return to slavery of men who had worn His Majesty's uniform was an indelible stain on the British character.

Fourteen Months in Bermuda

The Georgia recruits had provided three further black companies. When the British companies left for home in April 1815, the six black companies became the 3rd Battalion Colonial Marines, garrisoned in Bermuda on Ireland Island with a British Staff Company brought from Canada to accompany them as a token of white supervision. They did garrison duty, and worked as artisans and laborers in the building of the new Royal Naval Dockyard. Cochrane recommended they be established on the island to man the garrison as a reserve force in case of further American conflict, describing them as "infinitely more dreaded" than English troops.

When transfer to the West India Regiments was proposed, and they again rejected the idea, the Duke of York, as commander-in-chief of the British army, offered them a regiment of their own, but they held the authorities to the original promise of settlement in a British colony. Their intransigence finally led the British government to agree to place them in Trinidad as independent farmers, and they left Bermuda on July 15, 1816.

The Corps Disbanded in Trinidad

Under Spanish rule, Trinidad had been neglected until French planters were invited to settle there in 1783. The British occupied Trinidad in 1797, and assumed possession as a colony in 1803 under the Treaty of Amiens of the previous year. Still underdeveloped, Trinidad needed new labor, but that need was seen differently by the British government and by the new British planters. The latter wanted to develop their sugar plantations, which required importation of new slaves, and although volatile sugar prices suggested a need for crop diversification, the planters had no interest in farming other crops, which had to be imported.

Failed attempts to bring in European and Chinese peasant labor led the Colonial Office and the governor of Trinidad to the idea of installing a new free class of black yeoman farmers. The War of 1812 gave an opportunity to obtain African Americans, though confusion over the intended destination of the refugees restricted the initial settlement in 1815 to only two hundred. In 1816, the Colonial Marines' refusal to join the army provided the main opportunity for carrying out the project, and in succeeding years men of various West India Regiments were similarly settled in the northeast of Trinidad.

Settlement

Following the Colonial Marines' arrival in Trinidad, they and their families were disembarked in two parties at Naparima (now San Fernando) on July 17 and 18, 1816, and formally disbanded near the Mission of Savanna Grande (now Princes Town) on August 20. They were organized in villages in their military companies, each under the local supervision of an ex-sergeant, sworn in as an alguacil or constable, and under the general control of the commandant of the quarter.

Each household in the Colonial Marines' settlements was to have five quarrés or sixteen acres, following the previous Spanish rule for persons of color, and as much more as they could cultivate. The mode of occupation was in dispute for a long time, and was settled only thirty years later with the confirmation of absolute title for those remaining settlers who claimed it. The behavior and character of the settlers were the subject of comment in the reports of the governor and the superintendent, as were technical matters of numbers, accommodation, illness, rations, and clothing.

Although not reported during the life of the Corps itself, the religious life they brought from America, three-quarters Baptist, one-quarter Methodist, dominates many later accounts of the community, attested by subsequent commentators, in some cases quoting the men themselves. A report of 1824 notes that the community included around twenty Muslims, presumably among the hundred of the Colonial Marines who were from Georgia and probably within the small proportion of the settlers born in Africa. They would have been the first in Trinidad recorded as Muslims, though they seem to have left no trace comparable with that of later Muslim immigrants from other countries.

Today's Memories

The community founded by the American settlers, the Merikens , maintains and celebrates its identity and memory today, embracing newcomers of later years, Hindu and Muslim, Indian and Chinese, in an ecumenical spirit, with many groups holding annual gatherings. The most extensive gathering is the Amphy and Bashana Jackson fraternity, celebrating their ancestors who came from the Chesapeake in 1814, and a number of single family groups, notably the McNish family, descended from Polydore McNish, born in Africa around 1780, and his American-born wife Nancy, who left bondage in Camden County in Georgia in 1815.

References

Anthony, Michael. Glimpses of Trinidad and Tobago. Port of Spain: Columbus Publishers Ltd., 1974.

________. Profile Trinidad, a Historical Survey from the Discovery to 1900. London: Macmillan, 1975.

________. Towns and Villages of Trinidad. Port of Spain: Circle Press, 1988.

Barron, Thomas James. "James Stephen, the Development of the Colonial Office & the Administration of Three Crown Colonies, Trinidad, Sierra Leone and Ceylon." Ph.D. diss., University of London, 1969.

Bell, Malcolm. Major Butler's Legacy. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1987.

Brewer, Peter David. "The Baptist Churches of South Trinidad and Their Missionaries 1815-1892." M.A. thesis, University of Glasgow, 1988.

Bullard, Mary. Black Liberation on Cumberland Island in 1815. South Dartmouth, Mass.: M. R. Bullard, 1983.

Carmichael, Gertrude. "Some Notes on Sir Ralph James Woodford, Bt." Caribbean Quarterly 2 (1992).

Cassell, Frank A. "Slaves of the Chesapeake Bay Area and the War of 1812." Journal of Negro History 67 (1972).

Field, Cyril. Britain's Sea-Soldiers: A History of the Royal Marines and Their Predecessors and of Their Services in Action. Liverpool: Lyceum Press, 1924.

Fredriksen, John C. Resource Guide for the War of 1812. Los Angeles: Subia, 1979.

Gleig, George R. The Campaigns of the British Army at Washington & New Orleans in the Years 1814-1815. London: J. Murray, 1836.

Hackshaw, John Milton. The Baptist Denomination. Diego Martin, Trinidad: J. M. Hackshaw, 1992.

________. Two Among Many. Diego Martin, Trinidad: J. M. Hackshaw, 1993.

Hickey, Donald R. "The War of 1812: Still a Forgotten Conflict?" Journal of Military History 65 (July 2001): 741-69.

________. The War of 1812: A Forgotten Conflict. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1990.

Horsman, Reginald. The War of 1812. London: Eyre and Spottiswoode, 1969.

Kingsley, Zephaniah. A treatise on the patriarchal, or co-operative system of society as it exists in some governments, and colonies in America, and in the United States, under the name of slavery, with its necessity and advantages; by an inhabitant of Florida. N.p., 1829, 2nd ed. Reprint, Freeport, N.Y.: Books for Libraries, 1970.

Laurence, K. O. "The Settlement of Free Negroes in Trinidad Before Emancipation." Caribbean Quarterly 9 (1963).

Mahon, John K. The War of 1812. New York: Da Capo, 1991.

Nicholas, Lt. Paul Harris. Historical Record of the Royal Marine Forces. London: T. and W. Boone, 1845.

Philippe, Jean Baptiste. An Address to the Right Hon. Earl Bathurst by a Free Mulatto. Port of Spain, 1823-24.

Smith, Dwight L. The War of 1812: An Annotated Bibliography. New York, London: Garland, 1985.

Stewart, John O. Drinkers, Drummers and Decent Folk: Ethnographic Narratives of Village Trinidad. Albany: State University of New York Press, 1989.

________. "Mission and Leadership Among the 'Meriken' Baptists of Trinidad" Afro-American Ethnohistory in Latin America and the Caribbean, ed. Norman Whitten, Jr. Washington: Latin American Anthropology Group, 1976: 7-23.

Tracy, Nicholas, ed. Naval Chronicle: The Contemporary Record of the Royal Navy at War, Prepared for General Use, Vol. 5. 1811-1815. London: Stackpole Books, 1999.

Weiss, John McNish. "The Corps of Colonial Marines 1814-16: A Summary." Immigrants and Minorities 15, 1 (April 1996).

________. The Merikens: Free Black American Settlers in Trinidad 1815-16. London, 2002. (Revised edition of Free Black American Settlers in Trinidad 1815-16: A Handlist. London, 1995.)

Wood, Donald. Trinidad in Transition: The Years After Slavery. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1986.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

On February 12th 1624 George Heriot, goldsmith to King James VI and founder of Heriot’s School, died.

George Heriot was probably born in Edinburgh, where he followed his father into a career as a goldsmith. His premises consisted of a booth near St.Giles in Edinburgh. In 1588 he was made a member of the Incorporation of Goldsmiths and was elected their Deacon in 1593.

He became very wealthy through money lending, and his clients included King James VI. James appointed George goldsmith to his queen, Anne of Denmark, in 1597 and, in 1601, he was appointed jeweller and goldsmith to the king himself. When James succeeded to the English throne, He moved to London and set up at the Court of St James in London. He was widowed twice. He married Christian Marjoribanks in 1586. She died about 1603. His second wife, Alison, the 16 year old daughter of Archibald Primrose, writer in Edinburgh, whom he married in 1609, died during her first pregnancy in 1612.

He died in February 1624 and was buried at St. Martin-in-the-Fields, London. His legendary wealth inspired the character of ‘Jinglin’ Geordie’ in Sir Walter Scott’s novel 'Fortunes of Nigel’ and in turn the Jinglin’ Geordie bar on Fleshmarket Close just off Cockburn Street.

He left no surviving legitimate children, but bequeathed a substantial amount for the provision of a hospital school in his home city for 'puir faitherless bairns’. His hospital is now George Heriots School, Heriot-Watt University also perpetuates his name.

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

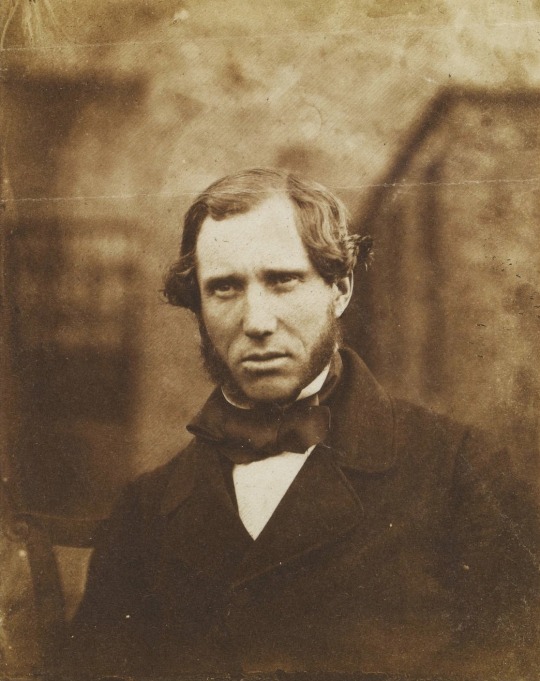

Did a little Googling inspired by @clove-pinks’ post on Admiral Cockburn, and found a diary excerpt from him about meeting with Napoleon on his (Napoleon’s) birthday. He had gorgeous, perfectly legible handwriting, unlike the deposed emperor he was escorting into exile.

Transcript:

August 15th - It being General Bonaparte's birthday, I made him my compliments upon it, and drank his health, which civility he seemed to appreciate, and, after dinner, I walked with him on deck, and had rather a long conversation with him, in which I asked him whether he really had intended to invade England, when he made the Demonstration at Boulogne? -He told me, he had most perfectly and decidedly made up his mind to it, but his putting Guns into the Praams and the rest of his armed flotilla, was only to deceive

[From Royal Collection Trust]

(Not being well-acquainted with naval stuff, I had to look up the word “praam”; it means “A small two- or three-masted ship used by the French for coast defence purposes during the Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars (1793–1815). They were flat bottomed, drew very little water, and carried from ten to twenty guns, being used as floating batteries or gunboats as a defence against coastal raids or assaults.” Thanks Oxford Dictionary.)

40 notes

·

View notes

Photo

CRAIGCROOK CASTLE IS SITUATED IN THE CRAIGCROOK DISTRICT OF EDINBURGH AND IS ABOUT THREE MILES WEST OF THE CENTRE OF THE CITY CENTRE. THE HOUSE WAS ONCE OWNED BY THE RENOWNED SCOTTISH JUDGE AND LITERARY CRITIC, FRANCIS JEFFREY, LORD JEFFREY, WHO, AS A FOUNDING MERMBER OF THE CULTURAL MAGAZINE “THE EDINBURGH REVIEW”, USED TO HOLD LITERARY GATHERINGS HERE. THE GUESTS WHO ATTENDED THESE SOIREES INCLUDED CHARLES DICKENS, HANS CHRISTIAN ANDERSON, LORD TENNYSON AND GEORGE ELLIOT. WHEN THE CASTLE WAS IN THE POSSESSION OF THE PUBLISHER ARCHIBALD CONSTABLE, SIR WALTER SCOTT AND LORD COCKBURN WERE FREQUENT GUESTS.

THE HOUSE IS PRESENTLY BEING TURNED INTO A CARE HOME -- HAVING FAILED TO SELL FOR ITS ORIGINAL ASKING PRICE OF 6 MILLION AND FOR THE REDUCED PRICE OF 5 MILLION.

0 notes

Text

Chesapeake Flotilla

With the outbreak of the War of 1812, the Chesapeak Bay of Maryland and Virginia, known as Tidewater, became a major site of American privateering. The British response was a strict blockade of the bay by the Royal Navy in February 1813, under the command of Admiral Sir George Cockburn, which not only blocked supplies but also repeatedly raided small coastal towns to minimise resources and drain the Americans.

Oars and Sails: The Chesapeake Flotilla at Dawn, 1814, by Peter Rindlisbacher (x)

As resources to defend the bay were scarce, Secretary of the Navy William Jones allowed Joshua Barney, a privateer from Baltimore, to assemble a flotilla of armed barges to fight the British blockade and the attackers. The crew consisted of a motley crew of about 500 sailors, privateers, native men of the region, runaway slaves and free African Americans. Together with the land troops who joined later, the flotilla totalled about 4500 men.

Barney (left) sketched the design for what he called a row-barge (x)

These armed barges, or "rowing barge", were to be more manoeuvrable than the old gunboats and capable of holding the enemy under constant fire at night without risk of being attacked.

American Commercial and Daily Advertiser, March 16, 1814. (x)

Barney's flotilla set out from Baltimore in 1814 with twelve barges, two gunboats and the flagship USS Scorpion. In all, there were five battles, the first of which took place on 31 May / 1 June 1814, the so called Battle of St. Leonard Creek. The Scorpion and her boats met the schooner HMS St Lawrence and boats of the Third Rates HMS Dragon and HMS Albion, both with 74- guns, on the way down the bay. The flotilla pursued St Lawrence and the boats until they reached the protection of the two 74s. A chase ensued and the flotilla, which was designed for shallow waters, fled into a creek. The British could not follow and speared the ships, but they repelled the British attacks and sat out the blockade until 10 June. The British, frustrated by their inability to drive Barney from his safe retreat, raided several nearby settlements in Maryland.

The US Chesapeake Flotilla was chased by a vastly superior British squadron near the mouth of the Patuxent River at Cedar Point on June 1, 1814. (x)

The flotilla was still stuck in the Creek and was now to break out, there was to be a joint attack from both land and sea. This worked on 26 June, and the flotilla was able to escape. But at a high price. Barney had to sink the two gunboats. As a result, the surrounding towns and especially St. Leonard became victims of the British once again.

Action in St. Leonard’s Creek, June 1-10, 1814. The first battle of St. Leonard Creek, by unkown (x)

On 11 August 1814, the flotilla left St. Leonard's Creek and sailed north up the Patuxent River. A plan had been discussed to transport the entire flotilla overland from Queen Anne harbour to the South River and return to the bay. However, as it was feared that the flotilla would fall into British hands, Barney was ordered to take his squadron as far up the Patuxent as possible to Queen Anne and sink the ships if the British appeared. This is what happened on 22 August, Barney had to destroy his flotilla because of the approaching British under the command of Admiral Alexander Cochrane . He then had the men of the flotilla and the mobile cannons forcibly marched to Washington D.C., where they were to take part in the Battle of Bladensburg. During this battle, Barney and his flotilla held their ground, but Washington was still lost and went to the British. On 15 February 1815, the Congress disbanded the Chesapeake Bay Flotilla. In October 1815, Barney and his men returned to the sunken ships and began salvaging everything they could. Where they were sold at auction in Baltimore.

Barney was highly rewarded for his efforts and received the rank of Commodore. He died on 10 December 1818 from complications caused by a thigh wound received during the Battle of Bladenburg.

119 notes

·

View notes